Changes in a system can be made in two primary ways. I like to call them Edit and Pray and Cover and Modify. Unfortunately, Edit and Pray is pretty much the industry standard. When you use Edit and Pray, you carefully plan the changes you are going to make, you make sure that you understand the code you are going to modify, and then you start to make the changes. When you’re done, you run the system to see if the change was enabled, and then you poke around further to make sure that you didn’t break anything. The poking around is essential. When you make your changes, you are hoping and praying that you’ll get them right, and you take extra time when you are done to make sure that you did.

Superficially, Edit and Pray seems like “working with care,” a very professional thing to do. The “care” that you take is right there at the forefront, and you expend extra care when the changes are very invasive because much more can go wrong. But safety isn’t solely a function of care. I don’t think any of us would choose a surgeon who operated with a butter knife just because he worked with care. Effective software change, like effective surgery, really involves deeper skills. Working with care doesn’t do much for you if you don’t use the right tools and techniques.

Cover and Modify is a different way of making changes. The idea behind it is that it is possible to work with a safety net when we change software. The safety net we use isn’t something that we put underneath our tables to catch us if we fall out of our chairs. Instead, it’s kind of like a cloak that we put over code we are working on to make sure that bad changes don’t leak out and infect the rest of our software. Covering software means covering it with tests. When we have a good set of tests around a piece of code, we can make changes and find out very quickly whether the effects were good or bad. We still apply the same care, but with the feedback we get, we are able to make changes more carefully.

If you are not familiar with this use of tests, all of this is bound to sound a little bit odd. Traditionally, tests are written and executed after development. A group of programmers writes code and a team of testers runs tests against the code afterward to see if it meets some specification. In some very traditional development shops, this is just the way that software is developed. The team can get feedback, but the feedback loop is large. Work for a few weeks or months, and then people in another group will tell you whether you’ve gotten it right.

Testing done this way is really “testing to attempt to show correctness.” Although that is a good goal, tests can also be used in a very different way. We can do “testing to detect change.”

In traditional terms, this is called regression testing. We periodically run tests that check for known good behavior to find out whether our software still works the way that it did in the past.

When you have tests around the areas in which you are going to make changes, they act as a software vise. You can keep most of the behavior fixed and know that you are changing only what you intend to.

Regression testing is a great idea. Why don’t people do it more often? There is this little problem with regression testing. Often when people practice it, they do it at the application interface. It doesn’t matter whether it is a web application, a command-line application, or a GUI-based application; regression testing has traditionally been seen as an application-level testing style. But this is unfortunate. The feedback we can get from it is very useful. It pays to do it at a finer-grained level.

Let’s do a little thought experiment. We are stepping into a large function that contains a large amount of complicated logic. We analyze, we think, we talk to people who know more about that piece of code than we do, and then we make a change. We want to make sure that the change hasn’t broken anything, but how can we do it? Luckily, we have a quality group that has a set of regression tests that it can run overnight. We call and ask them to schedule a run, and they say that, yes, they can run the tests overnight, but it is a good thing that we called early. Other groups usually try to schedule regression runs in the middle of the week, and if we’d waited any longer, there might not be a timeslot and a machine available for us. We breathe a sigh of relief and then go back to work. We have about five more changes to make like the last one. All of them are in equally complicated areas. And we’re not alone. We know that several other people are making changes, too.

The next morning, we get a phone call. Daiva over in testing tells us that tests AE1021 and AE1029 failed overnight. She’s not sure whether it was our changes, but she is calling us because she knows we’ll take care of it for her. We’ll debug and see if the failures were because of one of our changes or someone else’s.

Does this sound real? Unfortunately, it is very real.

Let’s look at another scenario.

We need to make a change to a rather long, complicated function. Luckily, we find a set of unit tests in place for it. The last people who touched the code wrote a set of about 20 unit tests that thoroughly exercised it. We run them and discover that they all pass. Next we look through the tests to get a sense of what the code’s actual behavior is.

We get ready to make our change, but we realize that it is pretty hard to figure out how to change it. The code is unclear, and we’d really like to understand it better before making our change. The tests won’t catch everything, so we want to make the code very clear so that we can have more confidence in our change. Aside from that, we don’t want ourselves or anyone else to have to go through the work we are doing to try to understand it. What a waste of time!

We start to refactor the code a bit. We extract some methods and move some conditional logic. After every little change that we make, we run that little suite of unit tests. They pass almost every time that we run them. A few minutes ago, we made a mistake and inverted the logic on a condition, but a test failed and we recovered in about a minute. When we are done refactoring, the code is much clearer. We make the change we set out to make, and we are confident that it is right. We added some tests to verify the new behavior. The next programmers who work on this piece of code will have an easier time and will have tests that cover its functionality.

Do you want your feedback in a minute or overnight? Which scenario is more efficient?

Unit testing is one of the most important components in legacy code work. System-level regression tests are great, but small, localized tests are invaluable. They can give you feedback as you develop and allow you to refactor with much more safety.

The term unit test has a long history in software development. Common to most conceptions of unit tests is the idea that they are tests in isolation of individual components of software. What are components? The definition varies, but in unit testing, we are usually concerned with the most atomic behavioral units of a system. In procedural code, the units are often functions. In object-oriented code, the units are classes.

Can we ever test only one function or one class? In procedural systems, it is often hard to test functions in isolation. Top-level functions call other functions, which call other functions, all the way down to the machine level. In object-oriented systems, it is a little easier to test classes in isolation, but the fact is, classes don’t generally live in isolation. Think about all of the classes you’ve ever written that don’t use other classes. They are pretty rare, aren’t they? Usually they are little data classes or data structure classes such as stacks and queues (and even these might use other classes).

Testing in isolation is an important part of the definition of a unit test, but why is it important? After all, many errors are possible when pieces of software are integrated. Shouldn’t large tests that cover broad functional areas of code be more important? Well, they are important, I won’t deny that, but there are a few problems with large tests:

• Error localization—As tests get further from what they test, it is harder to determine what a test failure means. Often it takes considerable work to pinpoint the source of a test failure. You have to look at the test inputs, look at the failure, and determine where along the path from inputs to outputs the failure occurred. Yes, we have to do that for unit tests also, but often the work is trivial.

• Execution time—Larger tests tend to take longer to execute. This tends to make test runs rather frustrating. Tests that take too long to run end up not being run.

• Coverage—It is hard to see the connection between a piece of code and the values that exercise it. We can usually find out whether a piece of code is exercised by a test using coverage tools, but when we add new code, we might have to do considerable work to create high-level tests that exercise the new code.

Unit tests fill in gaps that larger tests can’t. We can test pieces of code independently; we can group tests so that we can run some under some conditions and others under other conditions. With them we can localize errors quickly. If we think there is an error in some particular piece of code and we can use it in a test harness, we can usually code up a test quickly to see if the error really is there.

Here are qualities of good unit tests:

1. They run fast.

2. They help us localize problems.

In the industry, people often go back and forth about whether particular tests are unit tests. Is a test really a unit test if it uses another production class? I go back to the two qualities: Does the test run fast? Can it help us localize errors quickly? Naturally, there is a continuum. Some tests are larger, and they use several classes together. In fact, they may seem to be little integration tests. By themselves, they might seem to run fast, but what happens when you run them all together? When you have a test that exercises a class along with several of its collaborators, it tends to grow. If you haven’t taken the time to make a class separately instantiable in a test harness, how easy will it be when you add more code? It never gets easier. People put it off. Over time, the test might end up taking as long as 1/10th of a second to execute.

Yes, I’m serious. At the time that I’m writing this, 1/10th of a second is an eon for a unit test. Let’s do the math. If you have a project with 3,000 classes and there are about 10 tests apiece, that is 30,000 tests. How long will it take to run all of the tests for that project if they take 1/10th of a second apiece? Close to an hour. That is a long time to wait for feedback. You don’t have 3,000 classes? Cut it in half. That is still a half an hour. On the other hand, what if the tests take 1/100th of a second apiece? Now we are talking about 5 to 10 minutes. When they take that long, I make sure that I use a subset to work with, but I don’t mind running them all every couple of hours.

With Moore’s Law’s help, I hope to see nearly instantaneous test feedback for even the largest systems in my lifetime. I suspect that working in those systems will be like working in code that can bite back. It will be capable of letting us know when it is being changed in a bad way.

Unit tests are great, but there is a place for higher-level tests, tests that cover scenarios and interactions in an application. Higher-level tests can be used to pin down behavior for a set of classes at a time. When you are able to do that, often you can write tests for the individual classes more easily.

So how do we start making changes in a legacy project? The first thing to notice is that, given a choice, it is always safer to have tests around the changes that we make. When we change code, we can introduce errors; after all, we’re all human. But when we cover our code with tests before we change it, we’re more likely to catch any mistakes that we make.

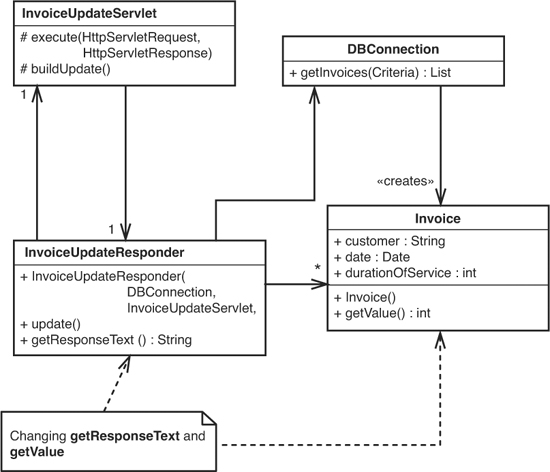

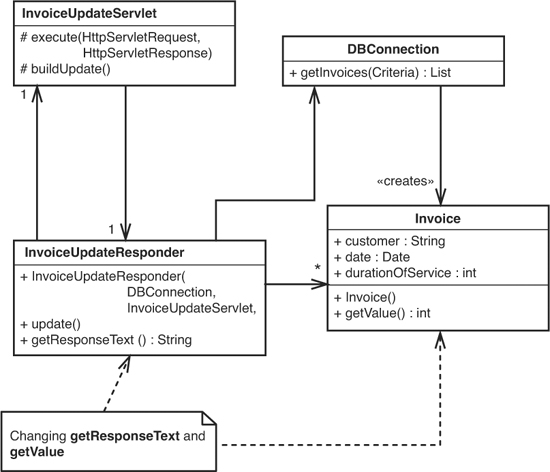

Figure 2.1 shows us a little set of classes. We want to make changes to the getResponseText method of InvoiceUpdateResponder and the getValue method of Invoice. Those methods are our change points. We can cover them by writing tests for the classes they reside in.

Figure 2.1 Invoice update classes.

To write and run tests we have to be able to create instances of InvoiceUpdateResponder and Invoice in a testing harness. Can we do that? Well, it looks like it should be easy enough to create an Invoice; it has a constructor that doesn’t accept any arguments. InvoiceUpdateResponder might be tricky, though. It accepts a DBConnection, a real connection to a live database. How are we going to handle that in a test? Do we have to set up a database with data for our tests? That’s a lot of work. Won’t testing through the database be slow? We don’t particularly care about the database right now anyway; we just want to cover our changes in InvoiceUpdateResponder and Invoice. We also have a bigger problem. The constructor for InvoiceUpdateResponder needs an InvoiceUpdateServlet as an argument. How easy will it be to create one of those? We could change the code so that it doesn’t take that servlet anymore. If the InvoiceUpdateResponder just needs a little bit of information from InvoiceUpdateServlet, we can pass it along instead of passing the whole servlet in, but shouldn’t we have a test in place to make sure that we’ve made that change correctly?

All of these problems are dependency problems. When classes depend directly on things that are hard to use in a test, they are hard to modify and hard to work with.

So, how do we do it? How do we get tests in place without changing code? The sad fact is that, in many cases, it isn’t very practical. In some cases, it might even be impossible. In the example we just saw, we could attempt to get past the DBConnection issue by using a real database, but what about the servlet issue? Do we have to create a full servlet and pass it to the constructor of InvoiceUpdateResponder? Can we get it into the right state? It might be possible. What would we do if we were working in a GUI desktop application? We might not have any programmatic interface. The logic could be tied right into the GUI classes. What do we do then?

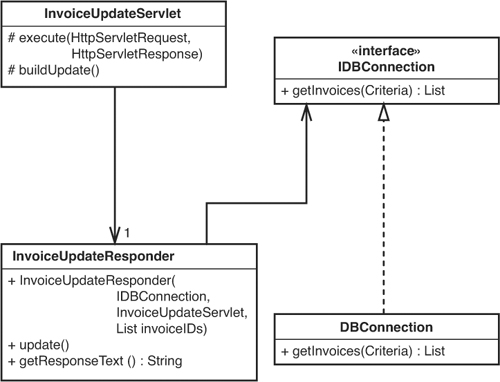

In the Invoice example we can try to test at a higher level. If it is hard to write tests without changing a particular class, sometimes testing a class that uses it is easier; regardless, we usually have to break dependencies between classes someplace. In this case, we can break the dependency on InvoiceUpdateServlet by passing the one thing that InvoiceUpdateResponder really needs. It needs the collection of invoice IDs that the InvoiceUpdateServlet holds. We can also break the dependency that InvoiceUpdateResponder has on DBConnection by introducing an interface (IDBConnection) and changing the InvoiceUpdateResponder so that it uses the interface instead. Figure 2.2 shows the state of these classes after the changes.

Figure 2.2 Invoice update classes with dependencies broken.

Is this safe to do these refactorings without tests? It can be. These refactorings are named Primitivize Parameter (385) and Extract Interface (362), respectively. They are described in the dependency breaking techniques catalog at the end of the book. When we break dependencies, we can often write tests that make more invasive changes safer. The trick is to do these initial refactorings very conservatively.

Being conservative is the right thing to do when we can possibly introduce errors, but sometimes when we break dependencies to cover code, it doesn’t turn out as nicely as what we did in the previous example. We might introduce parameters to methods that aren’t strictly needed in production code, or we might break apart classes in odd ways just to be able to get tests in place. When we do that, we might end up making the code look a little poorer in that area. If we were being less conservative, we’d just fix it immediately. We can do that, but it depends upon how much risk is involved. When errors are a big deal, and they usually are, it pays to be conservative.

When you have to make a change in a legacy code base, here is an algorithm you can use.

1. Identify change points.

2. Find test points.

3. Break dependencies.

4. Write tests.

5. Make changes and refactor.

The day-to-day goal in legacy code is to make changes, but not just any changes. We want to make functional changes that deliver value while bringing more of the system under test. At the end of each programming episode, we should be able to point not only to code that provides some new feature, but also its tests. Over time, tested areas of the code base surface like islands rising out of the ocean. Work in these islands becomes much easier. Over time, the islands become large landmasses. Eventually, you’ll be able to work in continents of test-covered code.

Let’s look at each of these steps and how his book will help you with them.

The places where you need to make your changes depend sensitively on your architecture. If you don’t know your design well enough to feel that you are making changes in the right place, take a look at Chapter 16, I Don’t Understand the Code Well Enough to Change It, and Chapter 17, My Application Has No Structure.

In some cases, finding places to write tests is easy, but in legacy code it can often be hard. Take a look at Chapter 11, I Need to Make a Change. What Methods Should I Test?, and Chapter 12, I Need to Make Many Changes in One Area. Do I Have to Break Dependencies for All the Classes Involved? These chapters offer techniques that you can use to determine where you need to write your tests for particular changes.

Dependencies are often the most obvious impediment to testing. The two ways this problem manifests itself are difficulty instantiating objects in test harnesses and difficulty running methods in test harnesses. Often in legacy code, you have to break dependencies to get tests in place. Ideally, we would have tests that tell us whether the things we do to break dependencies themselves caused problems, but often we don’t. Take a look at Chapter 23, How Do I Know That I’m Not Breaking Anything?, to see some practices that can be used to make the first incisions in a system safer as you start to bring it under test. When you have done this, take a look at Chapter 9, I Can’t Get This Class into a Test Harness, and Chapter 10, I Can’t Run This Method in a Test Harness, for scenarios that show how to get past common dependency problems. These sections heavily reference the dependency breaking techniques catalog at the back of the book, but they don’t cover all of the techniques. Take some time to look through the catalog for more ideas on how to break dependencies.

Dependencies also show up when we have an idea for a test but we can’t write it easily. If you find that you can’t write tests because of dependencies in large methods, see Chapter 22, I Need to Change a Monster Method and I Can’t Write Tests for It. If you find that you can break dependencies, but it takes too long to build your tests, take a look at Chapter 7, It Takes Forever to Make a Change. That chapter describes additional dependency-breaking work that you can do to make your average build time faster.

I find that the tests I write in legacy code are somewhat different from the tests I write for new code. Take a look at Chapter 13, I Need to Make a Change but I Don’t Know What Tests to Write, to learn more about the role of tests in legacy code work.

I advocate using test-driven development (TDD) to add features in legacy code. There is a description of TDD and some other feature addition techniques in Chapter 8, How Do I Add a Feature? After making changes in legacy code, we often are better versed with its problems, and the tests we’ve written to add features often give us some cover to do some refactoring. Chapter 20, This Class Is Too Big and I Don’t Want It to Get Any Bigger; Chapter 22, I Need to Change a Monster Method and I Can’t Write Tests for It; and Chapter 21, I’m Changing the Same Code All Over the Place cover many of the techniques you can use to start to move your legacy code toward better structure. Remember that the things I describe in these chapters are “baby steps.” They don’t show you how to make your design ideal, clean, or pattern-enriched. Plenty of books show how to do those things, and when you have the opportunity to use those techniques, I encourage you to do so. These chapters show you how to make design better, where “better” is context dependent and often simply a few steps more maintainable than the design was before. But don’t discount this work. Often the simplest things, such as breaking down a large class just to make it easier to work with, can make a significant difference in applications, despite being somewhat mechanical.

The rest of this book shows you how to make changes in legacy code. The next two chapters contain some background material about three critical concepts in legacy work: sensing, separation, and seams.