Interior Beethoven: the familiar trope pictures the inner reaches of the creative mind at play—the ultimate creative mind, in a version of the Romantic legend. What can we glean from the disparate, often chaotic evidence that survives of this process? How might the frail and imaginary constructs that we piece together from the traces of this fitful process be heard to imprint themselves as emblems of meaning in the work that finally emerges? With Beethoven, this is not a simple inquiry. The evidence, rich and dauntingly complex, has survived in the voluminous sketches that Beethoven wrote (and, astonishingly, preserved) for seemingly every project that he undertook. Then, for Beethoven the process itself, the act of composing, in its obsessive aspect, seems to infiltrate into the substance of the work in subtle ways that challenge the axiom by which we have come to hold the text of the work inviolable.

I have in mind two congeries of sketches, for movements that have much in common. Both associated in the popular imagination with Shakespeare, both in D minor, they are yet separated from one another by that brief interstice at the turn of the century during which Beethoven sought to reconcile a received, objectifying engagement in classical models with a turning inward toward a newly subjective figuring of the composer’s voice—of the composer as protagonist.

The earlier instance has to do with some sketches for the slow movement—Adagio affettuoso ed appassionato—of the quartet in F major, Opus 18 no. 1. The topic is complicated by the survival of a set of parts for the quartet in a version that differs in all four of its movements from the published text. On the outer page of the part marked “Violino Imo” Beethoven inscribed a touching dedication, dated 25 June 1799, to his very close friend, the violinist Karl Amenda, on the occasion of Amenda’s departure from Vienna to his native Latvia.1 Two years later, almost to the day, in a long and deeply moving letter to his now distant friend, he confessed in painful and intimate exclamations to the increased deterioration of his hearing. “I beg you,” Beethoven writes toward the end of the letter, “to treat what I have told you about my hearing as a great secret to be entrusted to no one, whoever it may be.” And then, in a stunning afterthought, he closes: “Be sure not to hand on to anybody your quartet, in which I have made some drastic alterations. For only now have I learned how to write quartets; and this you will notice straight away when you receive them.”2 He was here referring to the publication of the set of six quartets comprised in Opus 18, which appeared in two installments in the spring and autumn of 1801.3

Much has been written about the differences between these two versions of the F-major quartet, and what it was that Beethoven learned in the interval separating them.4 Mainly, the differences point to a supple, newly gained mastery of the ensemble: an enhanced sensitivity to voicing and balance, and a greater technical control over the densely contrapuntal passages concentrated especially in the outer movements. The main body of surviving sketches is for the earlier, so-called Amenda version, and it is these sketches that will be our concern here.

Indeed, it was Amenda himself who was responsible for a provocative insight of quite another kind into the conceiving of the quartet. Many years after the event, he recounted an exchange with Beethoven that has had consequences for all subsequent readings of the work. Beethoven reportedly played the Adagio for Amenda directly after its composition. Asked what thoughts it aroused in him, Amenda answered: “It depicted for me the parting of two lovers.”“Wohl,” Beethoven is said to have replied; “I was thinking of the scene in the burial vault in Romeo and Juliet.”5

There would be every reason to sniff at such evident nonsense were it not for the discovery of some riddling inscriptions among the earliest surviving sketches for this very movement: “il prend le tombeau” (he seizes the grave); “désespoir” (despair); “il se tue” (he kills himself); “les dernier soupirs” (the dying breaths).6 The temptation to associate these wrought words with the Amenda report on Romeo and Juliet is great indeed, and few have resisted it. Owen Jander, in vigorous pursuit of the telltale signs of a Romeo and Juliet program embedded in the quartet, was intrigued by the language of these inscriptions. Why French? he asks, and answers that Beethoven’s source was not directly Shakespeare, but more likely the opera Romeo et Juliette by Daniel Steibelt, first performed in Paris in 1793 and published that same year in full orchestral score. The opera was not performed in Vienna, but (Jander argues) Beethoven would very likely have studied the score.7

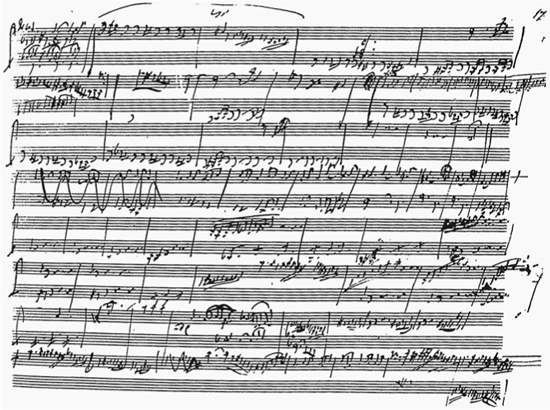

What, precisely, are these sketchbook hieroglyphs about? (They are shown in ex. 8.1.) How did Beethoven mean to inscribe them in the text of the music? These are not easy questions, and they open on to yet more sinewy ones. From their context in the sketchbook, it is clear that Beethoven is here preoccupied with the closing bars of the quartet. The residue of these fragmentary theatrical effusions continue to sound in the final moments of the completed work (see ex. 8.2).

EXAMPLE 8.1 Beethoven, Sketchbook [Berlin: SBB] Mus. ms. autogr. Grasnick 2, pp. 8, 9.

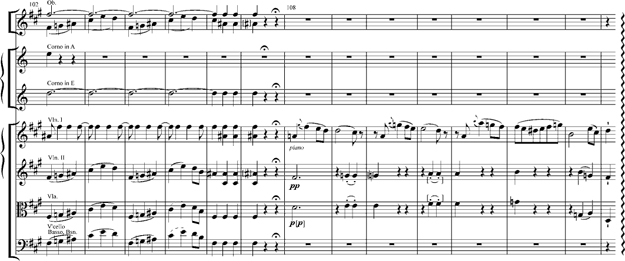

EXAMPLE 8.2 Beethoven, String Quartet in F, Opus 18 no. 1, Adagio affettuoso ed appassionato, mm. 92–106.

Characteristically, Beethoven now proceeds to other projects. He completes the preliminary drafting of the first movement. He works out some ideas for the scherzo and the finale. And he returns then to the Adagio. Several drafts into it, on page 17, we come upon a remarkable entry at staves 7–8, so far as I can tell, altogether unnoticed in the sketch literature. It pertains to the final bars of the exposition, here elaborated in a theme of self-possessed calm whose cadence is made to elide into the brief, highly charged music that will stand between the exposition and its reprise. The theme itself is remarkable in its hymnal decorum, its solving of the dissonances which penetrate the affecting theme with which the movement opens. It is shown (along with a false start) in ex. 8.3. (The full page is shown in facsimile in fig. 8.1.)

Entered at the middle of the page, the new theme (in F major) follows on a draft, occupying staves 1–6, for the final bars of a movement that was to have vanished in a lengthy run of broken sighs in the cello—and in D major. It will now have occurred to Beethoven that this pious new theme must sound again at the very end of the movement, and so he returns to the draft at the top of the page and enters the new theme, marked fine, evidently coupling its opening F# to what was to have been the final chord of the movement, and running its continuation into the margins, for the rest of the page had already been filled (see ex. 8.4). In the manner of a closing benediction, the theme now comes as an afterbeat to the troubled cadencing that precedes it, a palliative to those exaggerated gestures that seemed to fire up the sketching for this extreme movement.

Returning now to the bottom of the page, Beethoven replots the passage, its own cadence now attenuated and elided into the familiar sequence that modulates into G minor and the development, precisely as in the final version. In the draft, however, it is this new theme, and not the opening theme, that will figure prominently here, lending stability to its various tonal outposts. There are two trials at the very end of the page, the one moving toward D minor, the other moving through E#(and a new counter theme) toward F minor (see ex. 8.5).

EXAMPLE 8.3 Grasnick 2, page 17, staves 7/8.

A draft at the top of the next page (18) begins again with the new theme at the end of the exposition. Now a principal player, the new theme again launches a development in G minor, and would now bring it to a close in E♭ major (the realm of the Neapolitan), sounding distant and even nostalgic before the inevitable “da capo,” as Beethoven routinely labels the moment of reprise. The passage is heavily sketched (ex. 8.6 catches only some of the process), Beethoven listening hard to the silences and inflections that negotiate the return from this fragile E♭ to the grim business of D minor.

FIGURE 8.1 Beethoven. Page with sketches for String Quartet in F, Opus 18, No. 1, second movement. © Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin—Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Musikabteilung mit Mendelssohn-Archiv. Mus. ms. autogr. Beethoven Grasnick 2, p. 17. By kind permission.

EXAMPLE 8.4 Grasnick 2, page 17, staves 3/4.

At the top of the facing page, the tonal map is rearranged. There are signs that Beethoven seemed now to recognize the extent to which this solemn theme had overplayed its hand, transforming what, in the initial drafting, was to be music of raw, piercing emotion, into something measured and controlled, conciliatory and resolved. The theme makes a final appearance in another draft for the development (19), now in A minor, and is then abandoned, the Adagio evidently re-plotted yet again—in mind if not on paper, for the sketches in Grasnick 2 trail off here with entries for that difficult patch of music in the coda: again, a listening to silences and inflections.

How might this abandoned theme be understood to play into Beethoven’s Romeo and Juliet? The question is likely to launch further inquiry into the muddy waters of Shakespeare reception in eighteenth-century Germany.8 It might, for example, bear on the matter to know that among the most popular settings of Romeo and Juliet was a Singspiel by Georg Benda composed in 1776, and played with great frequency throughout Germany in the 1780s. It was performed in Bonn in 1782, where Beethoven would have heard it. And so he would have known that in this version, Juliet awakens before Romeo takes the poison. Indeed, both Benda’s and Steibelt’s operas end happily!9 If this is what Beethoven’s conciliatory theme means to emulate, the decision to abandon it might betoken a consequent restoration of an authentic Shakespeare.10 The vulnerability of such reasoning only points up the fallacy in the argument itself, perched uncomfortably on unprovable suppositions regarding the notion of equivalencies, or identities, or transliterations between the musical work and what is alleged to be its literary or programmatic counterpart. The suppositions become yet more vulnerable when the underlying text adduced is itself a dramatic work, for we might then be inclined to hear the temporal unfolding of the music as coordinate with the actions on the stage—not, of course, in a pedantically literal parsing, but in the alignment of the telling events in the music with those in the drama.11 And because the work of the stage is manifest in the interaction of its dramatis personae, the musical work must find its own entry into this complex play of voice and body. Does Beethoven’s music wrestle with these imponderables? In a purely cognitive sense, we cannot know.

Having now probed a bit into these interiors that put on display some of the process through which the work was conceived, we must now ask where that has gotten us. For Sieghard Brandenburg, it gets to actual meaning. Here is how he put it, in a colloquy on the topic published in 1979:

Beethoven’s well-documented intention of expressing the grave scene of Romeo and Juliet is something that has worked itself into the Gestalt of the movement in a way that can be heard. The rather painfully demonstrative character of this Adagio affettuoso ed appassionato is to be regarded as the result of his determination to represent extra-musical matters. For these the sketches reveal a concrete program, and even allow us to point to the place where Beethoven realized it, namely the movement’s coda.12

EXAMPLE 8.5 Grasnick 2, page 17, staves 15/16, 13/14.

EXAMPLE 8.6 Grasnick 2, page 18, staves 1–2, 9–11.

For Brandenburg, the meaning of the piece is incomplete without these programmatic signs. For although he claims that we can “take in this movement perfectly well without knowing the program,” he really intends a distinction between the perceiving of the music as some grammatical construct whose meaning begins and ends in the notes, so to say, and the understanding of what he calls its “concrete program”—those aspects of meaning more explicitly coupled to a dramatic scene.

Here, at this very moment—let us date it 25 June 1799, with the inscription of the Amenda copy—Beethoven touches the nerve of an aesthetic conundrum that would consume all of Romantic music in the century about to follow: how to reconcile the paradox of, on the one hand, music as the language empowered to express the inexpressible, from grand meta-drama with its appeal to the mythic themes of human existence, to the harmonic imaging of the poetic experience; and, on the other, music as a theoretical system that conveys the deep axioms of language—conveys, that is, the grammar and syntax of language, and is about this exclusively.

It touches a few other nerves as well. These intriguing sketches force us to grapple with the thorny problem how, or even whether, such evidence can be permitted into the rigorously circumscribed and much vexed arena of textual authenticity. The sketches, for all that they illuminate of a process of composition, are by definition excluded from the text of the work. We know these sketches only by the sheerest accident: Beethoven happens to have preserved them, guarding them until his death. If we cannot disentangle his deeper motives for doing so, we can surmise with confidence that the sketches were intensely private records that Beethoven kept to himself.13 What can we possibly know about the obscure decision making that would discriminate between the music in the sketches and the music completed for performance and publication? In venturing to say why this pious theme was abandoned, we speculate about the conceiving of the work, but such speculation, critical as it may be to an understanding of the acts of composition, is yet irrelevant to—necessarily locked out of—the discourse of the finished work.

And then there is Beethoven’s resolve to exercise, in the physical act of writing, complete control over the process of composition. In that resolve, he challenges the very ground rules by which genius had come to be understood. If, in the Enlightenment, the acts, the labors of creation were shrouded in mysteries having to do with inspiration, of godlike flashes that emanate from the soul of genius—one thinks here of Kant’s understanding of the products of genius, and, inevitably, one thinks of Mozart—Beethoven has no tolerance for such distance between the human act and the divine that such a model stipulates. And as a result, these labors of creation become increasingly difficult to separate out from the work itself. The author’s imprint is willfully ingrained in the work. These scenes of Romeo in Beethoven’s workshop will not go quietly.

Writing of the shift of sensibilities and its effect on the design of the novel of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Milan Kundera explores with uncommon wit the opposition of improvisation and composition:

The freedom by which Rabelais, Cervantes, Diderot, Sterne enchant us had to do with improvisation. The art of complex and rigorous composition did not become a commanding need until the first half of the nineteenth century. The novel’s form as it came into being then, with its action concentrated in a narrow time span, at a crossroads where many stories of many characters intersect, demanded a minutely calculated scheme of the plot lines and scenes: before beginning to write, the novelist therefore drafted and redrafted the scheme of the novel, calculated and recalculated it, designed and redesigned as that had never been done before. One need only leaf through Dostoyevsky’s notes for The Possessed: in the seven notebooks that take up 400 pages of the Pléiade edition (the novel itself takes up 750), motifs look for characters, characters look for motifs, characters vie for the status of protagonist.14

The aptness of all this to the compositional plottings encountered among the Beethoven sketches is striking. The game played out in the Dostoyevsky note-books—“motifs look for characters, characters look for motifs, characters vie for the status of protagonist”—seems an evocation of what one finds in these drafts for Beethoven’s Adagio. Surely, it helps to explain the comings and goings of this pious theme—a theme that in the end is never heard, for Beethoven expunged it from the final drafts.

Its trace, however, lingers. How that is so can best be apprehended in a contemplation of some final entries for the very end of the movement (shown in ex. 8.7). This new phrase seems a conflation of the opening strain of the pious theme and what is here recognizable as the closing theme in the recapitulation, beginning at m. 92 in the final version (shown earlier in ex. 8.2). Further complicating the texture of Beethoven’s thought, this familiar closing theme is found early in the sketching. And the pious theme itself is shown to have emerged gradually, in an intriguing entry marked (not altogether legibly) “2da parte” (see ex. 8.8), a designation that for Beethoven normally means “after the first double bar,” though must here refer simply to the second group in a sonata exposition. On the facing page—page 17—the new theme is endowed with function and purpose.

These sketchbook calibrations have yet another dimension, not limited to the linear unfoldings of plot and character. If this adagio has anything to do with the vault scene in Romeo and Juliet, it is surely not as representation, in some dramatic or even narrative mode, of the lightning quick sequence of events in Shake-speare’s act 5 scene 3, much less an evocation of the brilliance and nuance of language in which these events are cast. The unfoldings of plot and character in the Adagio—its formal imperatives—are of the purely musical kind that inform all sonata-like music in the late eighteenth century, impossible of congruence with events in the play. The ironic rhythms, the decisive cross-accents of the characters in Shakespeare’s scene are not traceable in the music. Action is here reduced to sentiment, tragedy to melodrama.15 Finally, we are asked to believe that this Adagio, alone in the quartet, refers to Shakespeare’s tragedy. But what of the other movements? Is it only the Adagio that shifts into programmatic gear?

Let us concede that the expressive quality of these musical incidents—above all, those “painfully demonstrative” ones that Brandenburg notices in the coda—might reveal how Beethoven conjured “the parting of two lovers,” and that the sketches merely corroborate Amenda’s testimony regarding the envisioning of the vault scene in Romeo and Juliet. Knowing what we do of Beethoven’s sketchbook probes, or even that such conjurings inspired him to music, can we bring such intimate confidences to play in the discourse of the finished Adagio? Or have we then trespassed on the sanctity of the text, and betrayed the testimony of the composer against his work?

EXAMPLE 8.7 Grasnick 2, page 19, stave 13.

EXAMPLE 8.8 Grasnick 2, page 16, staves 7–9.

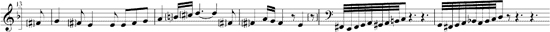

Infrequently among the obsessive drafting of expositions, the tinkering with detail, the notating of isolated Einfälle, the laboring at contrapuntal fit, there materializes in the sketchbooks an entry so stunning as to suggest that we are witness to some vaulting conceptual leap. The famous draft for the first movement of the Piano Sonata in D minor, Opus 31 no. 2 (shown in ex. 8.9 and fig. 8.2) elicits that sort of response.16 “A concentrated shorthand wherein the entirety of this music and the particularity of its structure seem already to have been realized,” writes Peter Gülke, who is then inspired to wonder about “the relationship of creative process (Entstehungsweise) to composed-out structure” and beyond, “to questions as to the character of a piece that does not, even in its definitive version, lose the improvisatory, draft-like quality that Beethoven so persistently composed against the fixed components of composition.”17

In the theater of the sketchbook, the entry appears to have been artfully staged, for it occurs in the midst of some eighty-eight pages of compulsive sketching in the spring of 1802 for the three Violin Sonatas that would be published as Opus 30.18 Barry Cooper, puzzled as well by the curious location of the draft in its isolation at fol. 65v among the sketching for Opus 30, devised an ingenious hypothesis that identifies the draft as a sequel, seemingly written out of turn, to some earlier entries that yet appear fifty pages deeper into the book, at fol. 90v (shown in ex. 8.10).19 His argument grows from the speculation that the ever frugal Beethoven, having reached the end of the Kessler Sketchbook, now returned to some pages inadvertently left blank and pressed them into service. This is at once compelling as an explanation of the solitary picture of the draft on fol. 65v, and troubling in its contradiction of a practice commonly observed in which new projects are undertaken with a good clutch of blank paper ready at hand.20 The turning to an isolated page in the midst of a book otherwise entirely filled does not sit comfortably with the challenge to the mind of a gathering of virgin paper ahead. Still, there are exceptions, and this may well have been one of them.

If certainty of order is not a luxury that this scenario enjoys, Cooper yet wishes to hear the two drafts as related in a manner approaching cause and effect. Although the draft on fol. 65v “gives the appearance of being a sudden inspiration—a kind of written-down improvisation that formed [Beethoven’s] very first thoughts on the movement,” Cooper writes, “careful examination shows that it is simply a thorough reworking of the material of the synopsis sketch on fo. 90v ”(emphasis added).21 The earlier draft is perceived to harbor “several inherent weaknesses that led to it being laid aside, but it was now revived in a different shape with the weaknesses eliminated.” The published sonata is then understood as “a model of how to solve several conflicting compositional problems without compromising the essence of the original idea.”22

One such “inherent weakness” in the earlier draft attaches to the new theme, in D major and dolce, that responds to the half cadence poised for recapitulation. We have only an incipit, but its few notes are suggestive of a broadly phrased theme, classically balanced, elegant, courtly. (See ex. 8.11, with a hypothetical bass and continuation.) It cannot go on at great length; the notation in the draft—“e dopo l’allegro di nove”—is clear enough about that. For all its innocence, the theme sets off ominous signals for Cooper: “the slow interruption in D major had to be made more relevant, somehow, to the rest of the movement.” Here, following Coooper, is how the problem was solved: “The slow passage at the beginning of the recapitulation in the first sketch could be anticipated, but still appear unexpected, by introducing only a fragment of it at the opening; the problem of key structure could be solved, while keeping the major-key element, by using a dominant chord, A-major, instead of the tonic, for the slow sections.”23 The dolce theme, itself incongruent with what was emerging in Beethoven’s mind as the main thematic thrust of the movement, is yet salvaged in some of its properties. “Thus,” he writes in conclusion, “the sketch on fo. 90v can be seen as the main source of the D minor sonata, and the one on fo. 65v as a replacement for it, in which all the compositional problems posed have been resolved.”24

EXAMPLE 8.9 Kessler Sketchbook, Vienna, Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, Beethoven-Autograph A 34, fol. 65v.

FIGURE 8.2 From the “Kessler” Sketchbook. Vienna: Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, [Beethoven] A 34, fol. 65v. By kind permission.

EXAMPLE 8.10 Kessler Sketchbook, fol. 90v.

For all the cunning of Cooper’s reasoning from these telegraphic sketches, the stages of thought that he constructs do not take hold. In this view, the dolce theme is to be understood as the source from which the opening arpeggiation springs: it is the theme itself (or rather, what Cooper refers to as “the slow passage”) that furnishes the basis for this bold gesture “by introducing only a fragment of it at the opening.” But the opening of the draft on fol. 65v bears not the slightest resemblance to the motivic substance of the dolce theme, nor to its ethos. There is nothing dolce about these new opening bars. Then, to hold that the modality of the dolce theme (its “majorness”) is now transferred to the opening triad in the new draft is to misconstrue the harmonic sense of its gambit. Dominants, major triads by default, stand outside mode. It is dissonance that they are about. To hear in this harmony an evocation of the dolce theme is to dismiss as mere contrivance the boldly novel utterance with which the new draft on fol. 65v (and the finished sonata) begins.

Isolated deep in the bass, this solitary C# will be understood soon enough as the signifier of radical dissonance. This is not the major third with which the dolce theme placates the turbulence of D minor. In the new draft, C# is a leading tone, and its position at the bottom of the arpeggio only exacerbates what might be called the structural role of the dissonance. The raised dampers, “se[nza] so[rdini]”—an effect that becomes increasingly thematic in the course of the movement—is inscribed as a grain of its voice, for the arpeggio must be imagined as though in a vault.25

Furthermore, to associate the arpeggiated Adagio (Largo, it will become, in the printed version) with what Cooper labels the “slow” theme in D major is to confound the very different temporal functions of these two passages. In stately and measured contrast to the nervous music that it interrupts, the dolce theme moves at a new tempo, but it is not demonstrably “slow” in any absolute measure. The opening bars of the draft on fol. 65v are about tempo in a radically different sense. The effect is of a single harmony, reverberating more in space than in time, senza tempo. That, surely, is what the fermata signifies and the blurring of raised dampers abets. More than that, the rolling of a dominant in first inversion puts us at once in mind of recitative—an implication of course born out in the recapitulation, in which the fermata is displaced by literal recitative.

EXAMPLE 8.11 Kessler Sketchbook, fol. 90v, st. 11, with hypothetical continuation.

The convention itself is worth a moment’s thought. In Mozart, the first-inversion triad establishes the new scene, always a shift from the tonal space and formal closure of the scene preceding: Don Giovanni and Zerlina suddenly alone after Masetto’s “Ho capito” in F major—first inversion triad, C# in bass; Don Ottavio and Donna Anna alone in a dark room after the cemetery duet of Don Giovanni and Leporello in E major—first inversion triad, C# in bass; and, most strikingly, at the aborting of a final cadence in F minor at the conclusion of the fatal encounters in the Introduzione, Don Giovanni and Leporello suddenly alone—first inversion triad, B# in bass. If Beethoven’s gambit opens the mind to recitative and to what it would portend of an imaginary operatic scena, it alludes no less to a music just ended. That is its dramatic function: to clear the stage, to reset the action.26 To begin a sonata in this way is to evoke the aura of dramatic action underway. No earlier sonata by Beethoven—and none by Mozart or Haydn—begins with so radical an opening; the only gambit comparable to it is Emanuel Bach’s Sonata in F, with its fragile opening phrases in C minor and D minor (see chapter 4).

Perhaps the most intriguing element of Cooper’s theory of sketch transference is constituted in the sequence of simple chords at the end of the exposition in the draft on fol. 90v, and continuing into the “2da parte.”“These repeated-chord figures,” Cooper tells us, “anticipate, and help to explain, a similar idea in the recapitulation of the final version (bars 159–168, shown in ex. 8.14). In this final version, the chords seem to have little relevance to the rest of the movement … but they can now be seen as a borrowing from this sketch, where, as in the final version, they lead into rapid arpeggios.”27 The ominous, muffled chords beginning at m. 159 are indeed mysterious in origin. Cooper’s explanation is of a piece with Brandenburg’s notion that the verbal inscriptions among the sketches for the Adagio of Opus 18 no. 2 “reveal a concrete program” otherwise not deducible from the text of the finished work. Wishing us to “understand” these muffled chords as emanating from an earlier sketch, Cooper invokes a field of reference that extends beyond the work to the draft abandoned at fol. 90v. Bearing “little relevance to the rest of the movement,” the passage in question evidently gains in “relevance” when its origins in the sketch are recognized. The conceptual provocation of such a view is in its proposal of an epistemological universe in which the internal, self-referential system of the work—in short, its syntax—is disabled. No less provocative, it proposes an integrity of a strange kind: “relevance” is to be sought not in the work itself but in a putative relationship in which the isolated idea, perceived to be irrelevant in the work, is discovered in some inchoate form outside the work. Even if the draft on fol. 90v might be said to figure in some arcane way in the conceptualizing of Opus 31 no. 2, it is the specificity of connection, of the one “anticipating and helping to explain” the other, that should set off alarms. The zealous quest for explanations, as though the meaning of such a passage could ever be adduced through arguments laboring toward a proof, is itself suspect.

How, then, might one understand this riddling music at m. 159? Its unique rhythmic cast is only one symptom of what is conveyed at this signal moment in the piece. For one, the moment captures a telling enharmonization in which F minor (toward which the recitative must resolve) is reformulated as a chord of the sixth, a first-inversion dominant whose root is C#. The trochaic rhythm is heard not as an afterbeat to a final cadence (as in the draft at fol. 90v), but as the beginning of a new paragraph. This is a critical difference in the way these chords are conceived. Surely, the establishing of a root C# will resonate profoundly with the very pitch from which the draft on fol. 65v unfolds. These first-inversion triads, then, invoke the opening arpeggiation of the draft not merely in self-evident reference to dominants in first inversion, but to the deeper implications of a dissonant simultaneity. C#, invoked now as a root, is thus endowed with hierarchical eminence.

If this way of hearing the music at m. 159 seems a reach, it will be instructive to recall the opening moments of two of Haydn’s quartets, both from Opus 33. The Quartet in C major begins with the bare interval of a sixth, soon enough recognized as the outline of a first-inversion tonic in C. And yet it is the grain of dissonance in the interval itself, an E sounding at its bottom, that is of consequence. To begin this way, in the provocation of such ambiguity, is to set a plot in motion. The moment of recapitulation comes at this E with focused intensity: E, pointedly tonicized, sounds its triad only by suggestion, as a naked fifth (see ex. 8.12), then absorbed in the sleight-of-hand return to C major. The opening of the Quartet in B minor, similarly couched in a sixth, F# below D, is of course about other things. But again, the telling moment of recapitulation plays upon the dissonance with which the quartet begins. Here, too, the ambivalence of the sixth is exploited: F#, now unequivocally the root of a dominant, clarifies the dissonance of the opening D, grating now against A# as well (see ex. 8.13). There is a new poignance to these bars because the D, no longer construed as harmonically consonant with the F#, needs resolution to a C-sharp that comes only at the end of the phrase: if the opening teeters between D major and B minor, the recapitulation sharpens the ambivalence, because the new A# both strengthens the cause of F# as root even as it allows, if fleetingly, the illusion of an augmented fifth, where D poses as the root of a dominant.28

In the final version of Opus 31 no. 2, the dominant on C# at m. 159 responds as well to another telling moment, this at the outset of the development which, it will be recalled, begins with a sequence of unfolding harmonies, in gestural imitation of the opening measures of the piece. The vehemence of the downbeat at m. 99, where the principal theme is struck, fortissimo, in F# minor, answers to a six-four arpeggiation above C# in the bass. The deliberate impetuosity of the moment causes an ellipsis in which the dominant is short-circuited, setting in relief the temporal relationship established at the opening of the piece. As though impatient with these languid, timeless arpeggiations of harmonies that seem adrift, the theme breaks in prematurely. Sounded deep in the bass, C# is again left dissonant, now at the bottom of a six-four that in a sense can be said to resolve only sixty measures later. Marked by a new rhythm, the music at m. 159 plays out in a remote key the implications of the dissonance at the opening of the movement. (Example 8.14 attempts a synoptic view of these cardinal moments.)

We return once again to Cooper’s claim for the draft on fol. 65v that while it “gives the appearance of being a sudden inspiration—a kind of written-down improvisation—… careful examination shows that it is simply a thorough reworking of the material of the synopsis sketch on fo. 90v.” Whether a sketch, in its appearances on the page, can be read to embody the improvisatory is a matter worthy of Cooper’s skepticism. The temptation to so read it is encouraged by the improvisatory disposition of the music itself. Its opening idea may mean to signify the improvisatory, and to script a performance that engages in the mannerisms of improvisation, but it does not follow that such an idea was therefore conceived in the spontaneous grip that we come to associate with the improvisatory. And yet another look at this remarkable page puts us in mind of the converse: whether or not the musical idea might signify the improvisatory, the conceiving of it must at some point engage that spontaneity of mind through which idea is conceived. The sketchbook, for Beethoven, is commonly the site of such improvisations. That is its purpose: to encourage the spontaneity of idea, even on the grandest scale.

“You should have a small table beside the pianoforte,” Beethoven instructs his pupil, the Archduke Rudolph, in a well-known letter of 1823. “When sitting at the pianoforte you should jot down your ideas in the form of sketches. In this way not only is one’s imagination [Phantasie] stimulated but one learns also to pin down immediately the most remote ideas.”29 Often cited for what it tells us about the setup of the workshop, Beethoven’s advice yet suggests something about the way in which works are conceived. For Beethoven, composition begins in the quest for the remote idea. Sketching, whatever else it may be about, extends the inner ear in seeking out the inaccessible. The act of writing seeks to ground the idea, to bring it into the cognitive world. And while Beethoven suggests, in the very next sentence, that his pupil “also compose without a pianoforte,” there is no question that for Beethoven the piano is at once a sounding-board for these “most remote ideas” and an intermediary between abstract thought and written sign.

EXAMPLE 8.12 Haydn, String Quartet in C major, Opus 33, No. 3, first movement.

EXAMPLE 8.13 Haydn, String Quartet in B minor, Opus 33, No. 2, first movement.

EXAMPLE 8.14 Beethoven, Opus 31, no. 2, first movement: a synoptic view.

Indeed, it is difficult to imagine that the draft on fol. 65v did not emerge from an encounter between Beethoven and his instrument—more pointedly, from a testing of this cavernous sonority, knees pressed against the damper mechanism.30 If the draft was intended as a “thorough reworking” of earlier material, we might reasonably expect to find it littered with the graphic evidence of much alternative thinking, of false starts and puzzling stops. But this draft moves from its incipient C# as though in a single breath through to the beginning of the development, with its arpeggiations recharted through alien territory, and on to this most theatrical of recapitulations, in which the cardinal dissonances propounded at the outset are here reengaged.

The feel of the draft depicts a discursive process that is to some extent deceptive. It is not entirely clear whether, for one, the downbeat at the beginning of staves 7–8 was to follow precipitously from the fermata at the end of the previous system. Here, the transcriptions by Brandenburg and Cooper (and even Nottebohm31) seem misleadingly coherent. These three arpeggiations entered on staves 5–6, whatever would follow from them, suggest an improvisatory groping toward some undefined tonal outpost. The music breaks off on a six-four on B♭—not, that is, on the telling C# of the final version. The draft does not tell us whether Beethoven yet had in his ears the radical ellipsis that would set the development in motion—presumably in E♭ minor, to follow the implications of the six-four on B♭. It does reveal that the powerful connection between the new trochaic phrase at m. 159 and this earlier six-four—the isolation of C# in the bass and its further elaboration—would occur to Beethoven only in some subsequent phase in the evolution of the work.

Evidence for these final stages, either in draft or in the autograph score of the finished sonata, has not survived. And so the draft on fol. 65v remains the final written witness to the conceiving of a work that is commonly understood to embody a new conceptual mode in Beethoven’s thought. If its uncanny isolation in the sketchbook encourages an overly romantic picture of the birth of a bold new concept of sonata, it yet documents that process which Beethoven is at pains to describe to the Archduke, a consequence of Beethoven’s efforts to get in writing those aspects of the conception that would come clear only through the visceral act of playing—whether at the keyboard or in the mind. In this view, the act of writing is itself an improvisational reach for the idea that needs to be coaxed from the hidden recesses of the imagination.

How then to explain the lucidity with which those march-like chords beginning at m. 159 are heard and notated in this synopsis? The rhythm of the passage, strikingly unprepared, and without further issue in the sonata, is yet imagined in the draft precisely as it will go in the final version. Its position in the narrative is fixed with chilling exactitude evidently before much of the thematic material had been composed. There is no predicting how things will turn out. Whatever its weight in the dynamics of the finished sonata, this moment of rhythmic counterpoise seems as essential to the conceiving of the sonata as does the C# with which it all begins. What matters, of course, is how the passage is to be heard in the sonata, and not how it had been heard to formulate itself in the disarray of the sketchbook. Our sightings in the sketchbooks are as immaterial to an understanding of the work in itself as they are inestimable in the inquiry how this music came to be conceived.

If the appeal of the improvisatory is keenly felt in this sonata, the apparent improvisatory mode of the draft on fol. 65v puts before us the larger question of spontaneity: how to distinguish the symptoms of the improvisatory act—improvisation as a way of bringing thought into the world—from the gestural figures of improvisation that conspire within the substance of the work itself. To come to an understanding how such figures as the opening arpeggio mean to signify improvisation, whatever the premeditations antecedent to their composition, is to get at this distinction. Yet even this apparently simple distinction has its troubling, contradictory aspect. For while the draft might itself seem clear-cut evidence of the power of improvisation in the conceiving of the work—imagine in its place a taped recording of the event—it yet hints strongly of an urge to manipulate a process that is beyond conscious control, even if the immediate intent is to capture in writing the traces of unmediated thought. On the evidence of its fleet, synoptic vision of a complete movement, the draft suggests the power of improvisation—“intoxicated improvisation,” Kundera would call it—to generate rich structure. Simultaneously, the opening arpeggio is conceived as a tropological figure that means to represent—to gather within itself, as synecdoche—the idea of the improvisatory. The opening figure signifies the spontaneous process of improvisation. The thematic substance of the work is thus personified, inhabited by the figural spirit of its creator, who insinuates himself into the drama of its conception.

And yet this distinction drawn between the phenomenon of the draft as itself an improvisation and the gestures within it as so many signifiers of an idealized improvisation is continually slipping out of focus. By some understanding, the two phenomena are bound up in one another. The act of writing means to emulate the spontaneity of thought. But the predisposition of Beethoven’s mind to think about music in a certain way impedes the kind of spontaneity that Kundera apprehends in the novels of Diderot and Sterne. The improvisatory, now prefigured in the topoi of style, gains in coherence what it forfeits in spontaneity.

The opening bars in the new draft further redefine the relationship between performer and text, and it is worth pondering how that is so. Consider again Emanuel Bach’s prescription for the creation of a fantasia in the final paragraph of his Versuch. The text of the piece is meant to be exemplary, a final Probestück in the advance of the performer to the realm of spontaneously creative thought. Following a script, reading the text of the work, the player impersonates the composer improvising, reenacting the spontaneity of its creation.

On the face of it, there would be no reason to think that in the relationship established between performer and text, Opus 31 no. 2 should differ in this regard. And yet it does. In signifying the moment of its creation, its opening bars ask of the performer that the wonder of Ursprung be captured—not, that is, read as a text practiced in the mimesis of improvisation, but performed as though this music were only now conceived, as if it had previously not existed. The imposture is compounded, for the performer must enact whatever is appropriate to this process of “finding” the tone of the work. If Emanuel Bach’s fantasies, and Mozart’s, begin on tonics and play within the ground rules of genre, Beethoven’s sonata begins a step earlier in the process. Genre is reinvented. That is its point.

Somewhere in all of this lies the essential difference between the drafts on fols. 65v and 90v. When Beethoven writes that snippet of phrase marked dolce, he is signaling a formal intrusion that brings to mind another passage in D major. In the midst of the development in the first movement of the Symphony in F# minor (“Farewell”; Hob. I:45; 1772), Haydn has the music break off on a dominant in B minor, following thirty-five bars of relentless, aggressive attack, all in fortissimo. What follows is a new theme, marked piano—if dolce were in Haydn’s lexicon in 1771, here might be the place for it. The tempo is unchanged, but the effect is as if to placate the furies that have been driving this impetuous music.32 (See ex. 8.15.) The tune circles idly around itself, summoning effort enough to move toward a fragile diminished seventh that denotes a weak dominant ninth in F# minor. A solitary D, now dissonant, is left hanging for two bars. The recapitulation begins with a furious downbeat, fortissimo, in F# minor.

The placement of Beethoven’s dolce theme, and his instruction how it will end (“e dopo l’allegro di novo”) echos the central episode in Haydn’s fractious symphony.33 The resonance is evident as well in the powerful downbeat arpeggiation with which Haydn’s symphony and the draft on fol. 90v begin. If there is some connection here, even if its points of contact are more subliminal than overtly conscious, it is emphatically severed in the draft on fol. 65v. To get at this essential difference from another angle: if the dolce theme hints at antecedents and models, and further denotes a strategy for mapping an eccentric, highly charged sonata movement, the draft on fol. 65v, impatient with stratagems, frees itself from any a priori plan as to how this will turn out, and pointedly so of the plan at fol. 90v. If any residue of Haydn’s symphony survived in the draft on fol. 65v, it might be heard at the outburst of the principal theme in F# minor early in the development, as though drawn subconsciously to Haydn’s extreme key and the ferocity of the music that it sets loose.34 Implicitly inscribed in the C# with which the draft opens, F# minor is an ultimate destination, however deeply lodged in the subconscious, and so its coupling with Haydn’s symphony is as striking as it is speculative.

This probing of antecedents, of inspirations, returns us to Shakespeare, whose Tempest has been invoked in the naming of Beethoven’s sonata ever since Anton Schindler recalled for us his conversation with Beethoven on the meaning of Opus 31 no. 2 and Opus 57. “Lesen Sie nur Shakespeare’s Sturm,” Beethoven is said to have replied—just read Shakespeare’s Tempest—when Schindler asked after the “meaning” of the two sonatas.35 Conceding, against all odds, the veracity of Schindler’s testimony—allowing that such a conversation actually happened—only brings into focus the deeper aesthetic issues that Beethoven’s alleged response would elicit as evidence that might bear on an understanding of Opus 31 no. 2, for without a cross-examination of the circumstances under which Schindler’s question was asked and an answer formulated, we are without the slightest clue as to Beethoven’s intentions in replying as he did. Was the answer seriously proffered, or pulled out of thin air to rebuff the irritating Schindler? Does it—could it—accurately reflect Beethoven’s thought during the composition of these sonatas? Beethoven invoked Shakespeare’s Tempest only after the fact—considerably after, because Schindler seems not to have been on intimate terms with Beethoven until 1822, when entries in his hand first appear in the conversation books.36 Should we take this, then, as an invention ex post facto in recognition of some coincidental similarity of theme, of plot, of temperament? The questioning continues. We can be certain only that answers will not be forthcoming.37

EXAMPLE 8.15 Haydn, Symphony in F# minor, Hob. I:45, first movement, mm. 102–115, 132–145.

Kundera recalls his first reading of Diderot’s Jacques le fataliste, “delighted by its boldly heterogeneous richness, where ideas mingle with anecdote, where one story frames another; delighted by a freedom of composition that utterly ignores the rule about unity of action.” He ponders again this opposition of improvisation and composition. “Is this magnificent disorder the effect of admirable construction, subtly calculated, or is it due to the euphoria of pure improvisation? Without a doubt, it is improvisation that prevails here,” Kundera decides, and in so doing, comes perilously close to confusing the way in which the work was created with the aesthetic mode in which it was conceived. But, he continues, “the question I spontaneously asked showed me that a prodigious architectural potential exists within such intoxicated improvisation, the potential for a complex, rich structure that would also be as perfectly calculated, calibrated, and premeditated as even the most exuberant architectural fantasy of a cathedral was necessarily premeditated.”38 Wrestling with the paradox of “rich structure” as at once “perfectly calculated, calibrated, and premeditated” and yet the product of “such intoxicated improvisation,” Kundera seems here to efface the differences between them.

It is a great temptation to invoke Kundera’s eloquence against all my circumlocutions around Haydn’s Creation and Beethoven’s Sonata in D minor. And yet it might be claimed that much of Haydn’s music, and indeed much of Emanuel Bach’s, displays this “magnificent disorder” as a symptom of the improvisational mode that Kundera detects in Diderot and Sterne. In the Vorstellung des Chaos, Haydn enacts what I proposed (at the end of chapter 7) as a meta-improvisation: an improvisation that is itself a commentary on the creative act as improvisatory. It is an adventure, a lively engagement with mind and sensibility. The disorder is metaphoric. For the early Romantics—for Beethoven, in the opening bars of Opus 31 no. 2—the improvisatory acquires aesthetic allure: the music simulates what it wishes to imagine as the spontaneity of creation. The creative act, now self-conscious, is sanctified, mystified, romanticized. The “art of complex and rigorous composition” that Kundera claims for the novel of the nineteenth century is evident here as well. The improvisatory in the sonata is in some sense calculated, even if the written evidence for its calculus survives only in a fugitive draft in a sketchbook.

In his Creation, Haydn views the creative act through a piercing lens. Grounded in a profoundly human irony, it looks the Creator straight in the eye, unflinchingly. Haydn takes us by the hand and entrusts to us the courage, and the wit, to make something. In 1792, he took Beethoven more literally by the hand, guiding his studies in strict counterpoint and no doubt much else.39 Decades later, Beethoven will compose a Vorstellung des Chaos that would forever alter the moral landscape. The opening pages of the Ninth Symphony play out with uncanny fidelity the romance that Schenker wished too fervently to hear in Haydn’s music: “the first vibrations and movements, the first stirrings of dark forces, the coming into being … ”40 The bracing wit and optimism of Haydn’s Chaos here concedes to the stern purpose of Beethoven’s Hegelian heroism, and to the tragic vision that it portends.

Benjamin’s death mask returns. The finality of text smothers the enlivening process through which the work is conceived. For the author, the process is charged with a meaning that may be sublimated in the work, or suppressed and denied. That slender vestige of a dolce theme, abandoned in the draft for a sonata in D minor, figures here, even in its faint echoing of Haydn’s Symphony in F# minor. So, too, does that openly devotional theme, newly discovered late in the composition of Adagio of Opus 18 no. 1, worked up to a position of audible prominence in the movement, and abruptly abandoned in the sketchbook. This is a personal matter, internal to the author, and it is the demanding task of criticism to detect the signs of such private dialogue in a text that by aesthetic rule must conceal them. Expeditions such as ours, in search of the merest traces of evidence of the before-the-work, may help to illuminate how it happened that Beethoven clung with such tenacity to these sketchbooks long after their workaday relevance for the act of composition had past.41 The sketchbooks belong to the intimate history of the work. They constitute an intensely private journal that Beethoven was at pains to preserve, both as a protection against public scrutiny and as an assurance that this inscrutable history might yet survive.