Die Metapher des Anfangs war Drang zu sprechen.1

The itch that provokes the ideas that follow is lodged in some music that trembles between worlds, between aesthetics, balancing at the abyss between reason and the irrational, between chaos and coherence. It is not music that encourages those grand taxonomies from which we historians can’t seem ever to shake free. In these two chapters, I revisit three very famous works, composed within five years of one another by two composers—teacher and pupil: privately, and in the public arena of professional interaction—who bring to the problem of improvisation two very different aesthetic attitudes.

The Creation, a work that Haydn seems to have held higher than any other in his inexhaustible repertory, moved contemporary audiences to extreme responses even as it remained something of an embarrassment to the critics of the early nineteenth century, in the main for instances of what were viewed as naive pictorial illustration. But there is one movement that has always excited the fancy of its critics: the Vorstellung des Chaos with which the work unforgettably opens. I retain the librettist van Swieten’s German here, because the conventional Englishing of Vorstellung as “representation” or even “depiction” is asking for trouble. Vorstellen means, in the first instance, the act of imagining, of conjuring in the mind. There is a foundational distinction between an apperception of primordial Chaos as a phenomenon given to tapestry-like depiction, on the one hand, and a conjuring of Chaos as a condition of the empfindsame mind offered an opportunity, indeed an imperative, to create, ex nihilo.

By 1800, The Creation was, in H. C. Robbins Landon’s account, “the most discussed musical work in Europe.” The title of the fourth volume in his magisterial Haydn: Chronicle and Works suggests as much: The Years of “the Creation”: 1796–1800.2 Nor has interest in it abated. In the past decade alone, there have been comprehensive handbooks on the work by Nicolas Temperley, Georg Feder, and Bruce MacIntyre.3 That these compendia have much to say about the composition of Chaos should not surprise us, for it was this music that inspired the most spirited, and indeed diverse, response from Haydn’s contemporaries. More recently, it has incited lengthy and probing studies: by A. Peter Brown, who, in a scrutiny of the extraordinary sketches for the work—one of the very few of Haydn’s works for which any sketches have survived—is led to the notion that the music of Chaos has its prototype both in the archaic ricercare, its legacy of rhetorical device extending back some two hundred years, and in the so-called free fantasy as Haydn would have understood it in the music and theoretical writings of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach;4 and by Lawrence Kramer, who, in a richly cross-disciplinary study, interrogates the epistemological basis of the idea of “absolute music.”5 Kramer was spurred in his effort by a landmark analysis of the work by Heinrich Schenker, whose lifelong project sought a theoretical framework to account for the great wing-spans of tonal coherence that he believed to be unique to the works of the German masters from Bach through Brahms. Schenker was consequently concerned less about the “chaotic” in Haydn’s Vorstellung than with the discovery of some hidden structural “law” that yet makes this music comprehensible.6

For Charles Rosen, the “famous depiction of chaos at the opening of the Creation is in ‘slow-movement sonata form’.”7 Donald Francis Tovey, many decades earlier, suggested that “the evolution of Cosmos from Chaos might be taken as the ‘programme’ of a large proportion of Haydn’s symphonic introductions.”8 James Webster, contemplating the model from a different perspective, argues that “Haydn’s Chaos is not merely a programmatic overture, but an intensification of his last symphonic introductions”—not, that is, sonata-form proper, but an instance of the overture-like music that precedes and yet stands apart from the drama.9

In each of these accounts, it is not Haydn’s understanding of Chaos, and what it might have meant to “represent” it, either as biblical event or natural phenomenon, that occupies its author, but rather an effort to identify a formal archetype, a convention, a process of music-making that would then, by default, make manifest the paradox of a Chaos apprehended by—conceived in—the rational mind.

In the many rehearsals of the story that this music denotes, the plot is thick with the romance of evolution and its teleologies. The moment of apotheosis comes at the creation of Light, a moment toward which all else ineluctably moves: toward the grand C major at “und es ward Licht.” This much celebrated C major chord “resolves” all the dissonance of Chaos, and its seemingly impermeable C minor. Webster puts it this way: “On the threshold of Romanticism stood Haydn’s ‘Chaos-Light’ sequence at the beginning of The Creation: a musical progression across three movements from paradoxical disorder to triumphant order.”10 Kramer’s account plays off Schenker’s: “The ‘Chaos’ movement famously achieves closure, not through the C-minor cadence that precedes Raphael’s recitative, but through the C-major cadence that concludes the setting of the sentence, ‘Und es ward Licht’ (And there was light),” writes Kramer, and then arrogates Schenker’s analysis to this view: “The first C-major chord … becomes the fulcrum of an extended foreground arpeggiation of the C-major triad in which, as Schenker observes, ‘overtopping the e♭3 of measure 9, the e3 of light lifts itself aloft in measure 89.”11 But the clear objective of Schenker’s study is in its circumscribed demonstration that the “Vorstellung des Chaos” runs its course, within itself: “With the arrival of c1 [at m. 58], all registral tension is released. Chaos has breathed its last; the Light will now appear.”12 For Schenker, these wing-spans of coherence were, by rigorous definition, always contained within the single movement.13 At the same time, the organicist agenda that underlies Schenker’s thought is much in evidence: “Music, as an art that unfolds through time, is well placed to represent Chaos: the first vibrations and movements, the first stirrings of dark forces, the coming into being [das Werden], of giving birth, at last the light, the day, the creation!”14

Such blurring of the boundaries between chaos and light ignores a formal distinction between the parts of the work: the Vorstellung des Chaos, articulated by a full close in the tonic C minor, was conceived as a prologue, an overture—“ Ouverture,” as it is even called in van Swieten’s autograph libretto.15 Whatever the settings of its own internal clockwork, this Vorstellung sets itself temporally apart from the main narrative of the work, envisioning a world at that unimaginable moment somewhere in the vicinity of the biblical “In the Beginning.” When, at the outset of Haydn’s narrative, Raphael sings “Im Anfange schuf Gott Himmel und Erde,” the music means to recapitulate, to remember, as mythic history, that dreamlike condition vividly actualized in the music of Chaos. But of course there is no C major triad in this “Introduction,” nor any sign of light. Scripture begins here, before this act that enables life. In Johann Gottfried Herder’s Aelteste Urkunde des Menschengeschlechts (Earliest Documents of Mankind) of 1774, these words—“In the Beginning God created Heaven and Earth”—were made the topic of a brilliant exercise in hermeneutical problematizing: how are we to imagine this “Beginning”? How to conceptualize the notion “He created”?16

The reactions to Haydn’s famous music at “Und Gott sprach: Es werde Licht, und es ward Licht” begin with an account of the first rehearsal. The testimony is from the Swedish chargé d’affaires in Vienna, Frederik Samuel Silverstolpe:

No one, not even Baron van Swieten, had seen the page of the score wherein the birth of light is described. That was the only passage of the work that Haydn had kept hidden. I think I see his face even now, as this part sounded in the orchestra. Haydn had the expression of someone who is thinking of biting his lips, either to hide his embarrassment or to conceal a secret. And in that moment when light broke out for the first time, one would have said that rays darted from the composer’s burning eyes. The enchantment of the electrified Viennese was so general that the orchestra could not proceed for some minutes.17

With due allowance for inadvertent postfactum embellishment, Silverstolpe’s account serves merely to confirm that from the get-go this stunning moment induced hyperbolic responses that obscure what the music actually does. It is now a commonplace to understand the C major triad both as synecdoche for light itself, and, metonymically, in its function as a resolution of the dissonances accrued, literally and figuratively, in all this music of Chaos. But consider again how this passage goes. (It is shown as ex. 7.1.) When God speaks “Let there be light,” this first biblical utterance is, in Haydn’s instruction, to be sung “sotto voce.” In timorous anticipation of the momentous event, a dominant triad is barely sounded in the strings: pizzicato, pianissimo. The simple motion from the one to the other—plucked dominant, blaze of C major—describes neither an act of triumph, of resolution, nor a problem solved through the labors of reason, but rather the happy accident of unexpected discovery—God finds the light switch, as someone once put it. Enlightenment comes through a process of revelation, empirically.

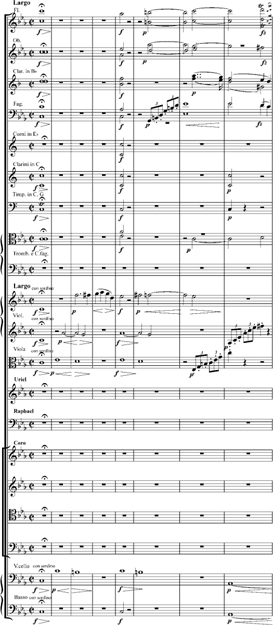

EXAMPLE 7.1 Joseph Haydn, Die Schöpfung, “Einleitung,” mm. 81–89, from the edition published by C. F. Peters (Leipzig, n.d.).

Not everyone thought so. In his reply to the question “What is Enlightenment?” put in a Berlin journal of 1784, Kant opens with the provocation “Enlightenment is mankind’s exit from its self-incurred immaturity,” which leads then to a manifesto: “Sapere aude! Have the courage to use your own understanding!” This, claims Kant, must be “the motto of enlightenment.”18 For Kant, Enlightenment is a beginning, not an end. The philosopher guides the immature toward a state of mind that would enable a free, untutored use of reason: Vernunft. The word (together with räsoniren) aroused Hamann to the churlish “Metacritique on the Purism of Reason,” not because Hamann had no faith in reason itself, but because he believed it to be misunderstood in what might be called its empirical dimension, as a constituent in how one goes about the business of thought. “The … highest and, as it were, empirical purism thus still concerns language, the only, first, and last organon and criterion of reason, with no credentials but tradition and usage.”19 For Hamann, the entire faculty of thought is founded on language. The knot is tied more tightly here: “language is also the center of reason’s misunderstanding with itself.”20 This cryptic “misunderstanding” has something to do with what Hamann identifies as a “partly failed attempt to make reason independent of all tradition and custom and belief,” and, in another sentence, “independent from experience and its everyday induction.”21 A few lines down, Hamann formulates his bold conceit for the beginning of thought: “The oldest language,” he proposes, “was music… . The oldest writing was painting and drawing.”22 Finally, “sensibility (Sinnlichkeit) and understanding (Verstand) spring as two stems of human knowledge from One common root, so that through the former objects are given and through the latter thought: what is the purpose of such a violent, unjustified, arbitrary divorce of that which nature has joined together!” Here is the crux of Hamann’s paradox: reason, in all its apparent purity, is yet unthinkable without language, whose meaning is acquired not a priori but through “tradition and usage.”

Enlightenment thinkers seem forever disentangling the problem of Word. In another reading of the Beginning, one which ignited much hermeneutical passion in the late eighteenth century, John begins his gospel “In initio erat verbum.” And it is precisely these gnostic words that Goethe has Faust pull down from his shelf at the outset of the famous Logos Scene in Faust I. The determination to translate the Bible into Faust’s beloved German is what gets the scene underway. “Geschrieben steht: ‘Im Anfang war das Wort!’” (“In the Beginning was the Word,” it is written), he begins, and at once dismisses “Wort” as too heavily invested. He interrogates the alternatives: “Sinn”—but is it really the mind that can have set creation in motion? (“Ist es der Sinn der alles wirkt und schafft?”). The inadequacy of “Kraft” (Power) strikes him as self-evident. In a moment of bold insight, he finds the word:

Mir hilft der Geist! Auf einmal seh’ ich Rat

Und schreibe getrost: Im Anfang war die Tat!23

A fussy exercise in translation, a parody of Talmudic exegesis, it might at first seem. “Bible-translation: there’s the latest fashion in scholarship,” wrote Herder in 1774.24 And yet, beneath Faust’s pretext lurks a more serious engagement with language and its place at the beginning of it all—even, on the futility, the impossibility of translation altogether, an idea poignantly conveyed in the suggestive amplitude of logos.25 This word, not actually named in Faust, resonates under the page (so to say) deep with implications: idea, concept, reason, world-spirit are all aspects of its meaning in ancient Greece, then inflected by the early Christians as divine reason and what Erich Trunz calls “das Schöpfungsprinzip”(the principle of creation).26 And perhaps Goethe means to conflate the meanings of logos with davhar, Hebrew for “word,” whose meaning is “at once ‘word,’ ‘thing’ and ‘act,’” as Harold Bloom reminds us.27 And I think it is now commonly accepted that Faust, in his worrying of John’s meaning, is engaging Herder’s richly convoluted gloss on this very phrase, in the Erläuterungen zum Neuen Testament (Commentaries on the New Testament) of 1775.28 In a passage that itself underwent much revision, Herder writes—or rather, stammers in an ecstatic gush—an understanding of “Im Anfang war das Wort”:

And yet the teaching Godhead lowers himself! How to make us worthy of recognizing him as other than Man? In a single image of our images, he chooses the holiest, the most spiritual, the most efficacious, deepest in his creative likeness in our soul: thought [idea]! word! plan! Love! Deed!29

Faust puts some poetic shape to Herder’s effusions, one might say, even as he examines the priority of Word that Herder elaborates in the essay On the Origin of Language. That sense of origin, of Ursprung (as a leap from something primordial) is ever repeated, if I understand Herder’s notion that “parents never teach their children language without the latter, by themselves, inventing language along with them.”30

In a footnote to his eruption on the opening words of the John Gospel, Herder writes “It is known that logos signifies the inner and outer word, Vorstellung [imagination] from within and Darstellung [representation] from without.”31 This distinction between Vorstellung and Darstellung, between the inner process of imagination and creation, and the external notion of exhibition and depiction, returns us to the opening music of the Creation. What I am getting at, all too obviously, is the sense in which Haydn’s Vorstellung des Chaos, whatever else it may be about, is no less an enactment of a quest to discover the beginnings of language, of linguistic utterance, much in tune with these essays by Herder and Hamann. Haydn’s scenario further brings to mind a notion attributed to Hamann: that “to understand or think is to participate in the drama that is the creation”32—just as for Herder, the genuine learning of language is to engage in creation, again ex nihilo. From which we might infer that to the Enlightenment mind, the idea of The Creation—the engagement, as Vorstellung, of the moment between Chaos and Light—is what ought to drive the human enterprise. What is life (Hamann might have asked) if not about this drama of creation?

Haydn’s music, then, means less to “depict” chaos than to imagine a process in which the Creator creates: less Darstellung, more Vorstellung. The music envisions this moment, before language and reason recognize one another; enacts the experiment of the creation of language in the metalanguage of music; and imagines what it might have felt like, as an experience of Empfindsamkeit in search of reason, to “create” a world: not a world necessarily of order in any perfect sense, but a world as it would have been understood in the ironical mode of Enlightenment thought.33 The music, as it unfolds, suggests an effort to put notes together, intuitively, guided by some natural sense, and prior to the codification into rules that would govern how notes, under prescribed conditions, must follow one another in works that do not actively engage in Hamann’s drama of creation. In its quest for the right notes, for the putting together of phrases, the music registers a journal of the creative act. This seems to me audible at once in the opening bars of Haydn’s score (shown in ex. 7.2), where the splaying of notes suggests the play of experiment, of discovery and invention.

When the first violins enter at bar 3, it is an entrance at once tentative and shrewdly provocative. An unprepared dissonance, the F is the missing tone of the diminished seventh at the downbeat of the measure, and so “completes” the harmony—as though the composer, through the players who do his bidding, will discover, intuitively and empirically, the rule by which such dissonances must be prepared, even as this F moves off in the wrong direction. The following F# is an implausible passing tone that subverts the main business of the seventh. The empirical adventure continues at bar 6, where the repetition now puts F# on the downbeat, reversing the relationship between these two pitches—as though F# were being tested as the preparation of the seventh. At bar 8, A♭, first heard as an unprepared flat six at bar 2, is now relocated to the bass, lending support to an emergent augmented sixth seeking the first true dominant, as though A♭ and F# had now found their true roles in respect of one another. The flutes, oblivious of this harmonic environment (doubled, comically, by the second trombone several octaves below), exercise a trill on D. By the conventions of the classical phrase, the trill would descend from D above the dominant, embellishing the close on the tonic. For these flutes, the trill is a thing of pleasure, an exercise of the instrument. Ignorant of its normal function as a controlling device, the trill here celebrates an escape to a climactic E♭—blithely contradicting the motion of the bass toward a dominant on G. The aggregate at bar 9 may seem to constitute a triad in first inversion whose root is E♭, but the experience of it suggests something else again: the C struck by the second violins at the second half of the bar claims the E♭ as a member of a dissonant six-four above G.34

EXAMPLE 7.2 Haydn, Die Schöpfung, “Einleitung,” mm. 1–21.

In its harmonic trajectories, the music of Haydn’s Chaos enacts yet more explicitly this quest for an intuitively coherent language. One passage will have to stand for several. The music wants eventually to move to the key of the relative major, from C minor to E♭ major. Everyone who hears this music will know that such a modulation is imminent. And indeed the music is drawn pointedly in that direction, toward m. 20. Unaccountably, the cadence is interrupted, or better, distracted. In its distraction, the music commits what the ear of 1798 would hear as a solecism: a breach in syntax, even of good grammar. D♭ is struck and ennobled as though it were a tone of significance. And it is uprooted in a blur of diminished seventh chords that finally drives the bass down chromatically, through the defining augmented sixth on C♭ that establishes B♭ as a dominant. E♭ is refound less by design than by accident, intuitively, irrationally. The music teeters on and around its dominant for thirteen bars, and then unwittingly slips back to C minor. There is an exploratory aspect to this music that is much to its point.

Haydn, then, humanizes the act of creation. God is projected in the image of Man. There is nothing heretical in this, and certainly nothing Romantic. It is a hard-nosed, ironical view of the proposition that Enlightenment comes only after a certain mucking about in the empirical forest. C major is the moment of Enlightenment, of Aufklärung, and we cannot say that we understand (or that Haydn means for us to believe) that this moment is causally effected by some ineluctable chain of reasoning. In that famous passage from the conversation with d’Alembert, Diderot invents the metaphor of the vibrating string to explain how the mind engages in thought: Vibrating strings have the property “to make others vibrate, and it is in this way that one idea calls up a second, and the two together a third, and all three a fourth, and so on. This instrument can make astonishing leaps, and one idea called up will sometimes start an harmonic at an incomprehensible interval.”35 This is how we think, this is the intuitive process of discovery and creation.

Haydn’s Vorstellung means not to say “this is what Chaos sounds like.” Rather, its music enacts, performs, in a Sprache der Empfindung (language of sensibility), through the play of syntax, a process of mind inventing speech, probing logos, dialectically, between reason and experience. In a sense, what we hear is not unlike what philosophers like Vico, Herder, and Hamann seem to conjure when they put themselves and their readers before the proposition of a world before language. The effort always to imagine the first word, which, for Hamann, enabled the freeing of the first thought—Herder, viewing the matter with some irony, saw the futility of holding that either reason or language can have preceded the other36—is akin to the process in which Haydn imagines the transition from Chaos to Light, even as Goethe, through Faust, tries to understand how logos is the beginning of all things.

To hear in this music the evocation of a Romantic sense of the infinitude of creation, of the sublime, is, to my mind, to mishear it. Haydn’s Vorstellung enacts the world as syntax and language: an experience of the world is in effect an effort to construe it in linguistic terms. The opening phrases, if they are about anything at all, are about the business of creation—the pleasures, divinely endowed, of creating. These musical phrases mean neither to depict nor to represent. Rather, they act out a scenario of creation, set in motion by that inert, ascetic opening octave. Hamann’s notion of thinking as a participation, less allegorical than actual, in the “drama that is the creation” resonates with an earlier formulation of the possibilities of artistic creation. Reading Federico Zuccari’s “L’Idea de’ pittori, scultori ed architetti” of 1607, Erwin Panofsky is led to conclude that “Since the human intellect, by virtue of its participation in God’s ideational ability and its similarity to the divine mind as such, can produce in itself the forme spirituali of all created things and can transfer these forme to matter, there exists, as if by divine predestination, a necessary coincidence between man’s procedures in producing a work of art and nature’s procedures in producing reality.”37 For Zuccari, “God has one single Design, most perfect in substance … ; man, however, forms within himself various designs corresponding to the different things he conceives. Therefore his Design is an accident, and moreover it has a lower origin, namely in the senses.”38 By the end of the eighteenth century, the creative mind could envision a yet bolder congruence between God’s Creation and the invention of Art: the magnetic fields are, so to say, reversed, and it is now adduced that what we can know only through empirical experience provides Man the only possible measure of God’s Creation. The accident of Design that Zuccari ascribes to human creation is now taken as a model for the Creation itself. Haydn’s Vorstellung is, to my ears, nothing less than this: God as empiricist, probing infinity for the rules that might impart to it some higher order; God as composer, enacting the original improvisation.

But of course this is no ordinary improvisation. In its personification of the “schöpferische Geist” (to borrow from Herder), the music emulates—enacts, rather—the divine improvisation by which, in Kant’s view, the work of genius creates its own rules.39 We are witness to the mind of Haydn in the act of composition as it conjures in fanciful mimesis the drama that is the Creation. And I do not think that it stretches the idea of composition in the Enlightenment to suggest that in the great works of Emanuel Bach, of Mozart in his maturity, of Haydn, of Beethoven, this drama is each time played out anew: we are meant to feel ourselves in the presence of the adventure of inspired improvisation. The “Ouverture” to Haydn’s Creation is a meta-improvisation. In its bold imagining of divine exploration, it offers a parable for the creative act as divinely human, a model for the process of enlightened thought.