In a letter of 13 May 1780, having sent two sonatas and three rondos to Breitkopf on 21 March, Emanuel Bach now establishes the order of this second volume in the series “für Kenner und Liebhaber,” and adds: “since you write that these 5 pieces amount only to something over 7 sheets, I will send you another short sonata in A major in the next mail.”1 The new sonata was sent a week later, on 19 May, with an instructive note: “the entire sonata must be played to the end in the same tempo and without a break; accordingly … it is not necessary to indicate any tempo other than Allegretto at the beginning.”2

An afterthought, one might gather from the correspondence, this “short” sonata has much to tell us about the constructing of a collection. (The complete sonata is shown in appendix 4A.) Its modest opening phrases, without the slightest pretense to that brazen originality commonly sought and found in Bach’s music, map out a rudimentary sonata exposition, but an unorthodox one. The dominant is established quickly, D# inflecting the music at what begins as a repetition of the opening bar. The music closes in the dominant at m. 8, but the D♮ at m. 9 returns the music prematurely to A major. The opening phrase returns literally at m. 11, but continues with a fine variant of m. 2, and for a moment the process of “veränderte Reprise” insinuates itself: in that fleeting moment, we sense a premature repeat of the exposition. But the music veers off to the dominant again, not, however, as firmly as at mm. 5–8. This is an exposition at loose ends, more improvised than plotted: Bach at his keyboard. The music feels a bit too comfortable in the hands. At the double bar, the music takes on some urgency, the placid phrases of the opening bars recast now in B minor. Again, the moment is fleeting, and the music moves off in a chromatic pass through E minor, touching F# minor in preparation for a true dominant on E, in the process recalling the phrase at mm. 8 and 9. The tonic is reclaimed, but in the varied form that it took at mm. 11 and 12. Recapitulation, then, begins with the languid extension of the dominant at mm. 9 and 10. The repetition of this second part of the movement, following the double bar, gives on to an eight-bar meditation, a listless, probing music in C major. Bach is often inclined to write something to negotiate between the two principal movements of a sonata: transitional, such passages are commonly named. What must strike us about this music is its sense not of transition, but of a dissolving, a liquidating, of the thematic discourse of the first movement, and of its tonal milieu. Again, the music has an improvisatory feel. It closes resolutely in C major, without the slightest sense of anticipation as to its seque1.3

The meter (but not the tempo) changes. What follows, in conventional terms, is a finale. But there is nothing conventional about this movement.4 Beginning as though in mid-phrase, the music seeks its bearing, circling around B minor not as a defining tonic but rather as a secondary area toward the finding of a strong dominant on E at m. 6. A tonic A major is sounded just barely at m. 10, yet unequivocally as the tonic. The music finds a cadence only at the double bar—but in B minor. In any formulation of sonata procedure around 1780, a cadence in B minor at the end of an exposition in A major would be understood merely as an aberration, even a quirky and ironic play on convention.5 But there is nothing quirky in the effect when the exposition is repeated. That opening harmony, irresolute at the outset, now seems to discover itself, sounding as though it grew naturally out of the cadence in B minor, as though the turn to B minor at the end of the exposition was composed with precisely this staging in mind. In retrospect, the significance of B minor in the first movement, even in the unexpected and unprepared transformation of the opening phrase, now resonates in these turns of event in the finale. As though to play on that earlier transformation, the opening phrase of the finale is now recast in F# minor: a resonant, brooding phrase that gives shape to the searching music with which the finale opens.

Having instructed Breitkopf as to the order of the other pieces in the collection, Bach composed this sonata altogether aware that it would follow on the very grand Rondo in A minor (H 262). For Bach, the ordering of such a collection, the sequencing of its keys, its genres, was not a trivial aspect in its production. Still, it is not often that we find evidence of an actual continuity implicit in how one work follows another.6 Here, at the end of this second collection, we do. The modest opening phrases of this little sonata, in their quaint affirmation of A major, follow strikingly from the closing bars of the rondo, a work given to bold modulatory advances set against the sweeping arpeggiations of its theme: “plaintive and melancholy,” wrote the critic for the Hamburgische unpartheyische Correspondent of this, his “Favorit-Rondo,” adding that he’d “seldom felt the power of harmony in such a degree as when he first heard this rondo played by Bach on the Forte Piano.”7 He singles out the remarkable passage beginning at m. 142 “where the theme begins again pianissimo and proceeds through an indescribably beautiful gradation [Gradation] of rise in the discant and fall in the bass, and finally resolves itself again in A minor.” (The passage is shown in ex. 4.1.) “We’re convinced,” he continues,” that Kenner and Liebhaber will linger especially here, and will know, thanks to the composer, that through the application of fermatas, he wishes to leave them time to breathe.” And, he adds, “if these rondos, and especially this passage, are to achieve their full effect, they must be played on a good fortepiano on which the resonance of the struck tones will make the effect all the more powerful… . These “fermatas [Aushaltungs-Zeichen, he now calls them] must be held as long as the instrument will allow.”8 Quite clearly, it is not merely Bach’s text that is under scrutiny here, but the manner in which he himself performs it. Bach seems habitually to have introduced new keyboard works, and indeed new publications, to a small circle of Hamburg colleagues both through performance and conversation. This extraordinary enharmonic passage was no doubt the subject of such conversation, and it is tempting to imagine Bach at the keyboard, lingering at the fermatas, exploring the resonance of this instrument for which it is expressly composed.

To argue for a deeper relationship of some kind between the themes of these two works—Rondo in A minor, Sonata in A major—tempting as that may be, is to lose a more immediate sense of connectivity, a tactile and acoustic rapport, even in the hardly perceptible motion from the poco andante of the rondo to the allegretto of the sonata. It would be incautious to insist that Bach intended the two works to be linked in performance. For one, the rondos in these collections were composed explicitly “fürs Forte-Piano,” as the title page instructs, whereas the sonatas, and certainly this one, were composed at and for the clavichord, even if one might think that by 1780 the deeper ideological and aesthetic schism provoked by these two instruments had begun to erode. Yet in its composition as a last-minute coda to the collection, in the actual conceiving of the work, Bach seems to have found the lucidity of its opening phrases in the contemplation of what might follow from the bold, labyrinthian closing pages of the rondo, grounding its wayward chromaticism, its sustained melancholy, in a plainly spoken prose, and in A major.

EXAMPLE 4.1 C. P. E. Bach, Rondo in A minor, H 262 (Kenner und Liebhaber, II, Wq 56/5), mm. 138–157.

The Kenner and Liebhaber invoked in this bit of contemporary criticism, a pairing that we have come to reduce to the schooled adept, the aspiring professional, in vivid contrast to the dilettante, are famously invoked in the titles of these six valedictory collections of Bach’s keyboard music. This is not to say that Bach composes now for the one, now for the other, that there is some categorical distinction to be teased out of each of his works. Something else is at play here. That bold chromatic passage in the Rondo in A minor is to the point: both Kenner and Liebhaber will linger at its fermate, writes the critic. Both will enter into its densely chromatic labyrinth, will hear linear vectors and feel the abstruse play of its harmonic roots. They will not feel the music differently. “There are passages here and there from which the connoisseurs [kenner] alone can derive satisfaction,” writes Mozart, of his Piano Concertos, K. 413–415, in a letter of 1782; “but these passages are written in such a way that the less learned [nicht-kenner] cannot fail to be pleased, though without knowing why.”9 Frequently cited, Mozart’s lines probe this distinction between Kenner and Liebhaber, and open onto the question of competencies, a matter of degree: less learned, more learned. How, we wonder, did Mozart visualize this difference? At bottom, he is worrying an axiom of Enlightenment aesthetics: the touching of the heart and the exercising of the mind as apparently distinct from one another and yet inseparable. What was it that the nicht-kenner did not know? Was it the technical “how” of composition? Or something yet deeper—the “why” (Mozart’s “warum”) that lies more deeply embedded in the composer’s intent? In a superficial sense, it is the former. The latter, that ultimate wisdom to which the Enlightenment sought entry, was accessible to neither Kenner nor Liebhaber, nor, one suspects, to the composer himself.

How then did Bach now come to envision his work in these terms? Why Kenner and Liebhaber? An incentive might be located in Forkel’s Ueber die Theorie der Musik insofern sie Liebhabern und Kennern derselben nothwendig und nützlich ist (Göttingen, 1777), which served Forkel as a curriculum for his lectures at Göttingen in the 1770s.10 “This learned Programma,” as Bach referred to it in a revealing letter to Forkel, is much about the Liebhaber, even in a sly addendum in which Bach wonders whether Forkel’s Liebhabern might be interested in the second volume of his newly published accompanied sonatas (H 531–534).11 Eventually, the Programma served as the basis for the formidable “Einleitung” to Forkel’s Allgemeine Geschichte, I (1788), a work that Bach himself, in a review that appeared in the Hamburgische unpartheyische Correspondent for 9 January 1788, praised for the satisfaction that it would bring “not only to every music amateur but to every friend of enlightenment in human knowledge.”12

And so it makes some sense to understand the six collections “für Kenner und Liebhaber”—published in 1779, 1780, 1781, 1783, 1785, 1787—as a playing-out of the implications in the title of Forkel’s treatise, implications which plausibly stirred in Bach’s mind amidst strategies for the marketing of new keyboard music.13 More to the point is what might be called a new conceptualizing of sonata that will speak to both Kenner and Liebhaber, as distinct from a music intended verifiably for the one or the other. But before we can begin to probe this distinction, it would be good to remind ourselves of what is not often noted about the auspicious first volume in the series: each of its six sonatas was composed no fewer than five years before the publication of the volume in 1779.

From its inception, the second volume was envisioned as strikingly new: “The content of these sonatas will be entirely different from all my other works—for everyone, I hope.” Bach wrote these bold words in December 1779. He had by then only recently composed the three rondos that would constitute the most striking novelty in the new collection—all three date from 1778, according to entries in the Nachlaßverzeichnis. Of the three sonatas in this collection, two date from 1780—one of them, the Sonata in A, would follow only in May—while the third had been composed in 1774. No doubt the sense of this collection as “entirely different” can have referred only to the rondo, whose standing as an independent work on a grand scale, each longer than the three movements of a neighboring sonata, was something of a new concept. The thirteen rondos dispersed over five volumes of these collections for Kenner and Liebhaber constitute a formidable repertory unique to the genre.

The first volume, however, was conceived differently. “Perhaps I shall soon appear with 6 new sonatas, without accompaniment, [to be offered] by subscription,” Bach wrote to Breitkopf on 21 February 1778: “There is a demand for it.”14 Drawing exclusively on earlier work, the project did not progress rapidly, for in a letter of 28 July, Bach again broached the matter somewhat tentatively with Breitkopf: “I would first of all, if it were agreeable to you, come forth with 6 sonatas for keyboard, without accompaniment. I’ve been asked about this.”15 By 16 September, the project had taken on life: “First of all, I am willing, with your good support, to have my 6 sonatas for keyboard (without accompaniment) ‘für Kenner und Liebhaber’ printed in two clefs [a certain number printed in violin clef, a certain number in soprano clef] by subscription,” with circulation of the published sonatas proposed for the spring book fair.16

By 9 October, Bach had set to work in earnest: “Among my sonatas, I’ve stuck in three shorter ones,” he writes to Breitkopf.17 A manuscript was sent off to Breitkopf with a letter of 13 November: “Herewith, my sonatas… . The title is: Sechs Clavier-Sonaten für Kenner und Liebhaber von Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, im Verlag des Autors 1779.”18 By 20 February 1779, Bach had seen some proof sheets.19 And on 16 April, Bach asks for a telling alteration: “If the title page of the sonatas should not yet have been printed, please add in the usual place: Erste Samlung. But if the title page has already been printed, this can be omitted, and ‘zweyte Sam[m]lung’ can be added in the second part.”20 Here, then, is the first hint of a second volume, and it comes even before Bach can have known the critical response to the first volume.

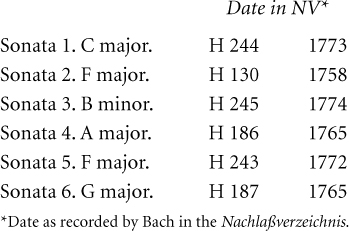

What comes across in the recitation of this correspondence is a halting process in which the idea of a collection of sonatas materializes only gradually, its audience of Kenner and Liebhaber identified even as the contents of the first volume were being assembled. The process itself invites speculation, for we know that the six sonatas finally chosen for this first volume were drawn from Bach’s deep portfolio of unpublished works:

None of the six sonatas has survived in an autograph manuscript, and so the inclination to subject these dates to further scrutiny is frustrated. The surviving manuscript copies all transmit texts that agree with the 1779 print.21 Still, there are hints that Bach himself viewed the collection as comprising two distinct phases. The three sonatas composed in 1772, 1773, and 1774 were among the six most recent sonatas in his portfolio—clearly, the “three shorter ones” to which Bach refers in the letter of 9 October. Of the three older sonatas, two of them were composed in Potsdam in 1765. They are both exceptionally grand. In its display of a symphonic brilliance and proportion otherwise uncharacteristic of Bach, the Sonata in A major remains among the most popular of his sonatas. The Sonata in G major, a bold and ingenious work, exploits the keyboard in other ways, its technical difficulties no doubt prompting its placement at the end of the collection.22 The first movement of the Sonata in F major (H 130), composed in 1758 in the midst of intensive work on the collection with varied reprises, is all introspection, Bebung, nuance, fine shading, and embellishment—all Empfindsamkeit.

The three later sonatas are of a different kind. In the toccata-like perpetuum mobile with which it opens, the Sonata in C (1773) seems designed to inaugurate a collection, in emulation of some earlier monument, even while there is no evidence to suggest that Bach had such a collection in view as early as 1773. The apparent modesty and small scale of the sonatas in F major (1772) and B minor (1774), both commonly cited for their beginnings off the tonic, mask a more complex regulation of dissonance over the long haul.

The novelty of the famous opening bars of the Sonata in F (H 243) registered at once. In a piece published in August 1779, the reviewer for the Hamburgische unpartheyische Correspondent noted that its first bar “begins in C minor, whose idea will then be repeated in D minor in the second bar, and in the third, will progress to the tonic F.”23 To stress only the unorthodoxy of the gambit, often admired in isolation, is to deflate the eloquent purpose in its phrases, each dissonant with respect to one another, each containing a poignant dissonance within itself. Absorbed in its nuances, the player must yet convey a syntax that binds them to one another while preparing for the shock of a “correct” dominant seventh, struck in a rain of thirty-second notes, forte, on the downbeat at m. 3 (see ex. 4.2). The aura is shattered. A proper theme, set squarely on the tonic, emerges finally at the beginning of m. 5.

Precisely how the elements of these half-dozen bars at the outset of the piece are juxtaposed in a scenario of dramatic substance is worth a moment’s reflection. In its initial embrace of C minor, in the elliptical space between this phrase and its sequel in D minor, these opening bars posit harmonies that lie outside the immediate orbit of F major: the true tonic cannot be surmised from these opening bars. That in itself tells us something about the profundity of dislocation here. Further, it seems to have gone unnoticed that the phrase, in its rhythmic shape, brazenly contradicts an axiom how sonatas—even those by this iconoclast—are to begin. No earlier sonata by Bach fails to establish a square initial downbeat on the tonic at the outset. The few trivial exceptions only stretch but do not contradict the axiom. But in this sonata from 1772, its opening phrases each beginning off the beat with a triad in first inversion, the axiom is turned on its head. In performance, the beginning must be made to sound as though the player were caught in the midst of speech. The eloquence of the discourse is tied in with Bach’s categorical refusal to explain away—to render conventional—these radical confrontations of affect. The conceptual world of these opening bars is new. An originality that had become the benchmark of Bach’s style here opens on to a new level.

EXAMPLE 4.2 C. P. E. Bach, Sonata in F major, H 243 (Kenner und Liebhaber, I, Wq 55/5), first movement, mm. 1–6.

In the Adagio maesto [sic] that follows, the tensions of expression are wound even more tightly.24 By force of association, its opening bars seem to echo the dissonances of the first movement, whose initial phrases will not recede from memory. Everywhere, the intensity of gesture is felt. Nothing is wasted. No phrase can be attributed to the demands of an imposed convention. The reprise of the twobar second theme, profoundly conceived in a compressed Veränderung, as though the concept itself were under scrutiny, seems to set its sights on the abrupt interruption of the cadence, an isolated and stunning F♮—E♭ in the treble, answered by a deep F# (see mm. 9–14 and 23–30 in ex. 4.3). The opening bars of the Allegretto follow with uncanny intimacy, as though hearing the dissonant C♮ left suspended high in register in the final measures of the Adagio. These bars, too, begin off the tonic, in recollection of those riddling phrases of the first movement, as though intuitively to complete—to correct—the syntax of an earlier ellipsis. It is the dissonant gap between the second and third bars in the opening movement that is healed at the opening of the Allegretto. This is a sonata whose three movements need one another—a sonata from beginning to end, in all three of its movements.

EXAMPLE 4.3 C. P. E. Bach, Sonata in F major, H 243, second movement complete, opening of third movement.

The historical place of this sonata is worth contemplating. With the exception of a “Sonate mit veränderten Reprisen” in F major, composed in 1769 and published the following year for the Musikalisches Vielerley (Hamburg: M. C. Bock, 1770)—a lesser, conventional work that does not much exercise the mind—it is the first sonata composed by Bach after his arrival in Hamburg in March 1768: indeed, the first since 1766, a watershed year in which, according to the Nachlaßverzeichnis, Bach composed no fewer than eleven sonatas, and a good many other works for keyboard.

During those first years in Hamburg, the demands on Bach’s time were exceptionally heavy, given not only to the regulation of music for Hamburg’s principal churches but to the revival of public concert life in the city. There were teaching duties as well.25 The new tensions of such a life cannot have been conducive to the introspective peace of mind requisite of the composition of works for solo keyboard, contemplative and introverted in their modes. The return to sonata in 1772 signals a turn inward: a response to, a withdrawal from, the imposing public genres of church and concert hall in which his recent work had of necessity been cast.

This first decade in Hamburg was a phase of extraordinary ferment in Bach’s music. In the background, as yet not perfectly understood in its entirety, was the production of much considerable music for the Church. Passion music was composed (much of it recycled from existing works) and performed every year beginning in 1768.26 More theatrical, and destined by Bach for greater dissemination through publication, are such works as Die Israeliten in der Wüste, composed in 1769 and revised for publication in 1775; the Passions-Cantate of 1769; the setting of Ramler’s Auferstehung und Himmelfahrt Jesu, first performed in 1774 and published in 1787; and the Heilig, mit zwey Chören und einer Ariette zur Einleitung, first performed in 1776 and, like the first volume of the sonatas “für Kenner und Liebhaber,” published by the author in 1779 through Breitkopf’s presses.27

Among the notable instrumental projects of these years are the six Symphonies for String Orchestra (H 657–662; Wq 182), composed in 1773 for Gottfried van Swieten, of which Reichardt was to write some years later of their “original, daring flow of ideas, and the great variety and novelty in their forms and modulations”;28 and the four Orchester-Sinfonien mit zwölf obligaten Stimmen (H 663–666; Wq 183), composed in 1775–1776 and published in 1780, of which Bach himself wrote: “They are the greatest of this kind that I have composed.”29 And Bach composed keyboard concertos during these years.30 Six (for harpsichord, H 471–476) were composed in 1771 and published in Hamburg at Bach’s expense.31 Among the chamber works of the 1770s are two sets (three each) of true piano trios—the Claviersonaten mit einer Violine und einem Violoncell zur Begleitung, I (Leipzig: 1776) and II (Leipzig: 1777), which provoked Forkel’s well-known analytical study of the rondo finale of the second sonata in Book I;32 and the six “Sonatas for the Harpsichord or Piano-Forte [with the accompaniment of violin and cello]” published in London in 1776.

The range of these new projects, the exhilaration that they display, the enriching of a style responsive to recent developments in theatrical music: all this suggests an escape from the daunting responsibilities that Bach undertook as Kapellmeister and music director of the five principal churches in Hamburg and as Cantor of the Johanneum, responsibilities not unlike those that his father had assumed in Leipzig nearly a half century earlier. His investment in those duties must have been of a rather different kind, for the circle of intellects that surrounded him—Lessing, Klopstock, Gerstenberg, Claudius, Voss, even Diderot (whose overture to Bach during a brief sojourn in Hamburg in 1774 is examined in chapter 6)—spoke to the secular, if not anti-clerical, themes of Aufklärung.33 In his last year, Bach composed twelve “Freymäurer-Lieder” (H 764), and although there is apparently no evidence that Bach was himself a Freemason, many of his friends were active members, and he cannot have been unsympathetic to Masonic ideals.34 In an earlier age, more secure in its devotions, the apposition of the secular and the sacred was an imperceptible one (witness the many instances of text interchange, of parody, in Bach’s cantatas). By the 1770s, the apposition touched deeper nerves, now evident in the perceived need to invent a “true” music for the church.35

It is in this context that these new sonatas of 1772–1774 were conceived. Others have written of the influence of Italian opera on the theatrical religious works from this period, and while Bach pointedly distanced himself from the frivolous world of the new comic opera, it would be naive to think that his music remained untouched by its rhythmic expanse.36 Hans-Günter Ottenberg suggests that the appointment in 1778 of Georg Benda as Kapellmeister at the Theater am Gänsemarkt may have “brought [Bach] into closer contact with theatrical life in Hamburg.”37 The new modulatory adventures of such works as the Heilig, the responses to which were documented with uncommon awareness in contemporary writings;38 the van Swieten symphonies whose first performance was recalled by Reichardt; the rondo that Forkel analyzed, and the great rondos to follow in volumes 2–6 of the collections “für Kenner und Liebhaber”: all are symptomatic of a more theatrical harmonic pacing. The elusive opening phrases of the Sonata in F belong here as well. It cannot be claimed that these phrases capture the staging and timing of opera in any literal sense. But in the anxious silences opened between the phrases, something of the internal clock of opera is suggested. The music breathes new air.

In the culling of Bach’s portfolio of unpublished works for this first volume, the sonatas not chosen are no less provocative in their omission than those with which Bach went to press. Among the refusées, two sonatas loom prominently:

Sonata in F minor (H 173), composed in 1763, about which Reichardt wrote with unabashed wonder and passion in 1776, and that, on its publication in the third volume “für Kenner und Liebhaber” (1781), would provoke Forkel to his famous Sendschreiben on the nature of Sonata.39 A reviewer for the Hamburgische unpartheyische Correspondent for 23 November 1781 described it as one of the best that the composer had ever written, noting that the sonata, “through the circulation of copies which, however, were in part quite corrupt, was already rather well known; and this was the reason why [Bach] was at first unwilling to publish the sonata in this collection.” But a number of those who did not yet have the sonata “pleaded with him so urgently that he finally gave in to their entreaties.”40 Bach’s decision, finally, to publish it was likely motivated by a wish to establish a clean text; no doubt it was Bach who made the reviewer aware of the state of those copies that were circulating.

Sonata in C major (H 248) from 1775, a radical work whose idiosyncrasies are admired above (see chapter 2): the last sonata to have been composed before Bach went to press with the first volume “für Kenner und Liebhaber,” it was the only sonata from the 1770s to have remained unpublished in Bach’s lifetime.

Three striking sonatas from 1766—two in B♭ major (H 211 and 212), the third in E major (H 213)—ought to have seemed reasonable candidates as well. We know all three of them in later revision. In its earlier form, the Sonata in B♭ (H 211) is in three movements. In the revision, the first movement is embellished with a complete set of varied reprises, the second movement (Larghetto) is removed, and a new transition of five measures is composed at the end of the first movement in preparation for the final Allegro assai.41 Similarly, revision subjected the outer movements of the Sonata in E to a full set of varied reprises. Each has survived in a complex tangle of contemporary copies and autographs. Darrell Berg, noting that the handwriting of the manuscript containing the varied reprises displays the telltale tremor evident in Bach’s later manuscripts, suggests that they were prepared “um 1784,” the year in which Bach composed the Sonata in B♭ Major, H 282, whose Largo is a reworking of the Larghetto composed with H 211.42 But the tremor in Bach’s hand is evident in earlier manuscripts as well, and it is not altogether convincing that the decision to move the Larghetto to a sonata that Bach was composing in 1784 for the fifth collection “für Kenner und Liebhaber” (1785) was somehow tied in with a decision to enhance the first movements of the sonatas from 1766 with elaborate Veränderungen. Perhaps the Larghetto had been jettisoned as a part of this reworking of the earlier sonatas—whether in 1784 or earlier—and was thus available for use as Bach set to work on H 282 in 1784. Nor should we rule out the possibility that these reworkings were undertaken in the preliminary planning of this first volume. Veränderung, however, roughly doubles the printed length of a movement. The first movement of the E major sonata runs to 185 ample measures in three-two meter, and perhaps its length alone acted as a disincentive to the ever frugal Bach, who was now undertaking all fiscal responsibility in a publishing arrangement with Breitkopf.43 “The subscribers will probably have to fork out another 8 gr[oschen] per copy on delivery this time,” Bach wrote on 20 February 1779, as he examined Breitkopf’s proof sheets. “The work is turning out longer than I thought. I must guard myself against bankruptcy.”44

In the effort to put forth a balanced collection, Bach’s shrewd reading of the market is calibrated against those deeper aesthetics that fired his imagination in the first place. However this may have played itself out in Bach’s mind, these five grand sonatas were kept from a wider public. In the case of the Sonata in F minor, the rejection was merely temporary.

That the volume published in 1779 set a new kind of sonata in relief against a backdrop of older sonatas was not lost on the critic for the Hamburgische unpartheyische Correspondent for 24 August 1779, who is quick to identify the first, third, and fifth sonatas (those from 1772–1774) as different in tone and manner from the other three:

The three lighter sonatas in this collection—the first, the third and the fifth—were presumably intended for the Liebhaber; indeed, they are easier to perform than the three others. And yet they are so full of Bach’s spirit and originality, so full of new ideas and surprising modulations, and at the same time of such engaging melody, that the Kenner too will study and play them attentively

We come now to the three sonatas that are somewhat longer than the others, and yet present no great difficulties in performance. These masterpieces are quite similar to those that immortalized the name of Bach during his tenure in Berlin. Similar, we say, with regard to the spirit that on the whole dominates them, but otherwise quite new with regard to idea and execution. It is well known that Herr Bach is one of those rare composers who does not plagiarize. His creative powers appear to be unlimited. Each of his sonatas is newly original, and—apart from the master’s general style—quite distinct from all his other sonatas.45

To have singled out precisely the sonatas numbered 1, 3, and 5 as “leichter,” to have admired their “new ideas and surprising modulations” (neuen Gedanken und überraschenden Ausweichungen), and further to have recognized of the other sonatas a kinship to the Berlin repertory—all this constitutes a criticism of uncanny perspicacity. “And were one to hear these masterpieces performed by Bach himself!” the critic closes: “O, there we stand, and know not whether to admire more the player or the composer.”46

Here again, one must indeed wonder whether the Hamburg reporter profited from a session with Bach, something like a lecture-recital on the contents of the collection, for we know of other instances where Bach’s commentary helped to guide the critic’s ear.47 Carl Friedrich Cramer, in a letter to Gerstenberg of 10 January 1779, wrote of a visit to Bach: “The day before yesterday … he played to me from his Sonatas ‘für Kenner u. Liebhaber,’ which are about to appear.” Of one movement in particular, Cramer writes “it was a sonata in tempo rubbato [sic], and oh! what a masterwork of modulation, variations of tempo, and expression.”48 What did Cramer mean by “tempo rubbato”? The reviewer for the Hamburgische unparteyische Correspondent—Joachim Friedrich Leister, it has been suggested49—describing the poco adagio of the Sonata in A, writes: “The tempo rubato with the division into 13 sixteenth notes deserves much study if one wishes to play it the way Bach does. His left hand strikes the notes of the bass according to the most precise measure, while his right hand wanders about in the sixteenths, and at the appointed moment, returns to the bass of the left hand.”50 The passage (shown in ex. 4.4) brings to mind an even more extreme instance of this composed rubato three bars before the recapitulation in the first movement of the Sonata in G (ex. 4.5).

EXAMPLE 4.4 Sonata in A major, H 186 (Kenner und Liebhaber, I, Wq 55/4), second movement, mm. 1–5.

If we can no longer reconstruct the circumstances under which these sonatas were performed for colleague and critic, we can surmise that on the occasion, Bach was not entirely silent on the history of their composition, no doubt pointing up distinctions between the earlier sonatas and the new ones. And from these two accounts of something called “tempo rubato,” we might infer that this very passage in the A major sonata inspired some commentary by the composer himself, and that it was his terminology that found its way into Cramer’s letter and Leister’s review.51 More provocative still is the notion that in a critical assessment of this music, it was the composer’s performance, indelibly inscribed into the notes on the page, that inspired these effusions of admiration. Performance as text.

We return finally to that elusive endeavor to say precisely how these new sonatas would speak to both the Liebhaber and the Kenner. The perception that Kenner and Liebhaber embodied two classes of musical literacy, and that they might be reconciled, was what drove the curriculum that Forkel developed in 1777 for his Göttingen lectures. He seems to have sent a copy to Bach, whose reply, in a letter of 15 October 1777, is uncommonly illuminating:

EXAMPLE 4.5 Sonata in G major, H 187 (Kenner und Liebhaber, I, Wq 55/6), first movement, mm. 44–50.

To my mind, N[ota] B[ene] in order to educate amateurs, many things may be omitted that many a musician neither knows nor needs to know. But the most important one—analysis, namely—is missing. One selects true masterpieces from all kinds of musical works; points out to the amateur the beautiful, the daring, and the new that is in them; at the same time one shows how insignificant the piece would be without these things; in addition one points out the mistakes and traps that have been avoided and, in particular, to what extent one can depart from the ordinary and venture something daring.52

For Bach, as for Mozart, Wissenschaft matters less than the acute sensibility of the Liebhaber to recognize, intuitively, the beauty of the thing without knowing how it is achieved. Forkel’s goal was more ambitious: “This, then, is the outline of a musical theory through which, to my mind, the Liebhaber can be educated to become a true and genuine Kenner,” he concluded, in the Einladungsschrift for his Göttingen lectures.53 As suggested earlier in this chapter, it is tempting indeed to think that Bach’s wording “für Kenner und Liebhaber,” first proposed to Breit-kopf in the letter of 16 September 1778, owes something to this exchange with Forkel—further, that Bach recognized in Forkel’s enterprise the opportunity to exploit a growing market among two classes of the musically literate.54

It is commonly assumed that the repertory of the six volumes “für Kenner und Liebhaber” exploits these two faculties: that the new and modish rondos, in the suave profiles of their memorable themes, address the amateur; the bold and introspective modulatory flights of the fantasias, the connoisseur. If there is any truth to this view of the thing, it is complicated by the more profound truth toward which the Hamburg critic points: that these “leichter” sonatas give only the appearance that they are “easy.” Both Kenner and Liebhaber will grasp the profundities hidden beneath simple surfaces and hear the simpler logic implicit in music more overtly complex. These are the classical oppositions that inform style and meaning in the music of the 1770s and 80s. The Kenner goes further, probing beneath their surfaces in search of theoretical underpinnings and explanatory models of greater sophistication.

Emanuel Bach remains the supremely enigmatic figure among the composers of the late eighteenth century. The magnitude and range of his output is difficult to grasp. His disdain for the popular even as he engages its genres embodies only one of many fruitful contradictions in his work. The sonatas for keyboard alone—some 150 of them, composed between 1731 and 1786—compass fifty-five years of a robust aesthetic history that Bach himself seemed often to dictate. Keenly sizing the marketplace, he cultivates it even as he repudiates it. The marketplace, we must remind ourselves, is no fixed, definable institution even in the circumscribed cultural arena of northern Germany in the 1770s. It is a phenomenon that materializes only in the exchange of ideas: each new idea, and the response elicited by it, alters the marketplace forever.

In his final years, Bach continued to compose even as he issued periodic warnings of his determination to stop doing so. “I will finish with the 5th collection [für Kenner und Liebhaber],” he wrote on 28 February 1786, “and indeed if there should be thoughts of a 6th, of which still not a note is finished, then nothing can take place before next year.”55 Curiously, the two sonatas finally included in this sixth set were both composed in 1785 according to the Nachlaßverzeichnis, though we cannot know whether Bach had yet determined to place them in a projected sixth volume. On 30 September 1786, Bach wrote to Breitkopf of his performance of the set, to the approbation of his friends.56 The manuscript was dispatched on 26 October.57 On that very day, he sent Artaria a copy of the announcement of its publication in the Hamburgische unparteyische Correspondent for 21 October 1786, noting that this was “to be the last of my printed works for clavier.”58

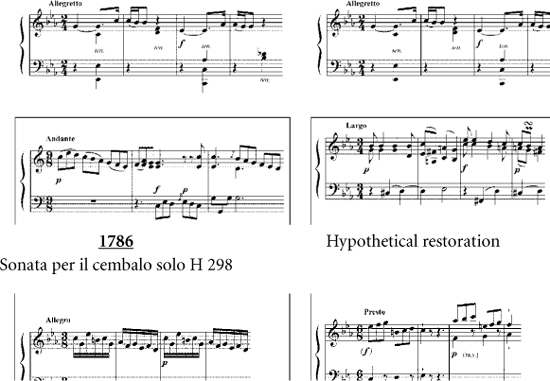

It was not however the last of his composed works for keyboard. The great, brooding Fantasy in F# minor (H 300) was composed in 1787, and then arranged for keyboard and violin (H 536), with the famous inscription “C.P.E. Bachs Empfindungen” (a topic to itself in chapter 6). But the purpose of these paragraphs is to contemplate another work, one that seems to have escaped critical scrutiny of any kind since its composition. This is the Sonata in C minor, H 298 (Wq 65/49), entered in the Nachlaßverzeichnis as item 205, where its date is given as 1786. Pamela Fox, having a look at its autograph, recognized that the date in the Verzeichnis can apply only to the first movement, and that the second and third movements, composed very likely in 1766, belonged originally to another Sonata in C minor, the one that Breitkopf published in 1785 as “Una sonata per il cembalo solo” (H 209, Wq 60).59 Writing to Breitkopf on 23 September 1785, Bach put it somewhat disingenuously: “It is entirely new, easy, short, and almost without an Adagio, since such a thing is no longer in fashion.”60

As it turns out, only the second and third movements of this sonata were “entirely new.” The first movement was composed nineteen years earlier, in 1766. Fox draws a sensible conclusion from the state in which we find the autograph materials: “In 1786, when Bach was sorting through his stockpile of potential materials, he retrieved the second and third movements from the 1766 sonata and wrote a new first movement.”61 Altogether plausible, Fox’s explanation only bears out what we learn from other, similar instances: that Bach abhorred loose ends. The two movements removed from the sonata for Breitkopf needed the grounding of a first movement, and so Bach composed one. (The peregrinations of these six various movements are shown in fig. 4.1.)

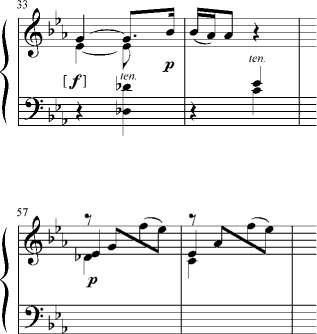

It could be left at that, were it not for the burnished luster that this new movement brings to our sense of Bach’s final works. In its quiet restraint, in the parsimony of its language and the concision of its thematic play, the music cloaks those subtle intervallic relationships to which we return again and again in an effort to understand why this piece seems to touch those deepest wells of Empfindsamkeit. The deployment of pitch and register in the opening phrase, even the isolating of the opening note in each phrase, invites the player to burrow deep into the key. Ten[uto], Bach writes, over the quarter-notes struck at the second half of the measure: five times at the opening, eight times in the reprise, and another five times beginning thirteen bars before the end. In keyboard music, it cannot be a question of notes “sustained at an even volume of tone,” as Koch prescribes in his Lexikon.62 Rather, it is the illusion that Bach is after, and a corrective to an inclination to play down these harmonies as somehow less significant than the Hauptstimme. In the simulating of the string player’s tenuto, the keyboard player is forced to think hard about these tones, and in this process, to refuse the conventional notion of “accompaniment.” Here, every note matters. (The entire movement is shown as appendix 4B.63)

It may come as a surprise to discover that in this brief movement the reprises are varied: its eighty bars, that is to say, would be reduced to forty, were the repeats not composed out. And this returns us to the larger issue of Veränderung. Why, one must wonder, would it have occurred to Bach to engage the uncompromising process of Veränderung–what is there, in this music of gnomic utterance, that would have inspired Bach to vary the reprises? An answer, quite logically, must be sought in the reprises themselves. Consider the opening bars. In the “reprise” sonatas of 1760, it is always the case that the repetitions keep the actual bass intact. However extreme the alteration to the thematic surface, the disposition of the bass with respect to the harmony is invariable. It is striking, then, to hear a radical departure from this practice at the outset of the first reprise in this final sonata. The fragility of its opening bars, the bass staking out a series of harmonies in first inversion, establishes a distinctive quality of voice. At the reprise of these opening bars beginning at m. 17 (see ex. 4.6), the initial octave in the bass, now unequivocally a root, dispels this fragility, taking sharper focus on the appoggiaturas in the upper voice.

And at the end of the recapitulation, the bass is reheard with great purpose. In its first iteration, the harmony shifts somewhat obscurely between mm. 53 and 54 over the sustained F in the bass: the determinants in the treble etch a motion through A♮ and B♮, suggesting that the F is transformed from a root to a seventh at m. 54, where the elaborate diminished seventh implicates a root G. At the reprise of these measures, the harmonic motion is strengthened, the newly voiced bass now articulating a seventh (E♭) at m. 77 that must descend to D in the following bar (the two passages are shown in ex. 4.7). This telling recomposition of the bass has its own thematic significance. At the outset of the second part of the sonata at m. 33–what a later generation would call “development”—the opening is recast with a striking turn of harmony. Restoring the articulative model of the opening bars, the D♭ in the bass (anticipating the seventh in the bass at m. 77) acts as a retrospective inflection of the bass at m. 1, just as its Veränderung (m. 57) touches back to the revision at m. 17 (see ex. 4.8).

EXAMPLE 4.6 Sonata in C minor, H 298, first movement, mm. 1–4, 17–20.

Veränderung of harmony is pushed to its limit at the passage approaching the recapitulation (see ex. 4.9). The alteration at m. 63 plays hard with the augmented sixth at m. 39, intensifying the waffling between A♮ and A♭. The equivocating is subtle. In the original passage, it has to do with a shift in meaning between a diminished seventh, showing A♮ in harmony with G♭, an appoggiatura that implicates the root F#. With the return of A♭ in the bass at m. 39, the G♭ is corrected to F#. In the Veränderung, this ambivalence is made a topic of its own, resolving finally in a fresh harmony: a dominant of the dominant, its root D firmly planted in the bass, coincident with a direct enharmonic shift from G♭ to F# in the soprano. On the clavichord, this is a shift of consequence, for the tone can actually be bent here to make the shift audible and touching.64 Tellingly, it is at the moment just before the recapitulation that this little scene develops. The urgency of resolution is amplified not in some gross display of dissonance and technique, but in a turn inward: a psychological meditation that almost stops the music. The tension is of that special kind intensified in the dynamics of Veränderung; what happens here is at once an extreme moment in the unfolding of narrative and a synapselike play of analogues.

EXAMPLE 4.7 Sonata in C minor, H 298, first movement, mm. 53–54, 77–78.

EXAMPLE 4.8 Sonata in C minor, H 298, first movement, mm. 33–34, 57–58.

EXAMPLE 4.9 Sonata in C minor, H 298, first movement, mm. 37–40, 61–64.

To experience this sonata at the keyboard, to play it on a good, resonant clavichord, is to be taken with music of uncommon subtlety and affect. And yet the modesty of its thematic elocution seems in itself to signal a conscious withdrawal from the public forum. For whatever reasons, the sonata has slipped by unnoticed. But perhaps there is an explanation for its neglect, and this has to do with the two movements attached to it. It will be recalled that Bach here reinstated the two movements composed in 1766 that were decoupled from that earlier Sonata in C minor during its makeover for Breitkopf in 1785, for which Bach then composed a very brief Largo—eight bars to a half cadence—and a splendid new Presto. The earlier movements were rejected for a reason. In its sixty-one tedious bars in 9/8 meter, the Andante in C major is a pale companion to either of these first movements, and so is the routine, work-a-day finale. Seeking to justify the brevity of the Largo to Breitkopf—“almost without an adagio, for such a thing is no longer the fashion” (beÿnahe ohne Adagio, weil dies Ding nicht mehr Mode ist)—Bach’s astute sizing of the marketplace is often seen as a capitulation.65 But perhaps this notion of Mode has deeper undercurrents. In often profound measure, his music had undergone an evolution since 1766. The great rondos composed between 1778 and 1786—thirteen of them for the collections “für Kenner und Liebhaber” and the plangent “Abschied von meinem Silbermannischen Claviere in einem Rondo,” H 272 (1781)—open a new window of musical space and thematic breadth, just as the six fantasies for the same collections challenge the distant edges of harmonic coherence.

This little imbroglio confronts us with a critical problem that extends beyond the textual residue of these two sonatas, in their incestuous relationship, to the somewhat inscrutable interiors of the creative mind. Bach’s final works, those particularly for keyboard alone, seem often to move to that inner space that one associates with lateness. Late style—Spätstil, Altersstil—is a concept born of a critical appraisal of the works of Beethoven’s final decade, as a way of explaining a music that turns away from artifice, from public display, from the edgy confrontation with novelty: a music that turns inward, that mirrors the isolation of old age.66 But of course Beethoven was not terribly old at the onset of this late style; he was forty-six years of age in 1816, the year of the Piano Sonata in A major, Opus 101. The question then asks itself whether the concept of “late style” is itself a trope borrowed from some Hegelian construct of historical narrative, an organicist view that models the evolution of art on the scaffold of the Romantic life; or whether there is indeed a quality—an “essence”—in the music that is identifiable with the psychology of old age and lateness, in which, as Georg Simmel put it, “the subject, indifferent to all that is determined and fixed in time and space, has, so to speak, stripped himself of his subjectivity—the gradual withdrawal from appearance, Goethe’s definition of old age.”67

Conundrums of this kind point us toward the imponderable, seeking out that “continually strange newness” that Adorno perceived in the music of Parsifa1.68 But the temptation to project a later notion of “late style” on this modest sonata must confront the chilling circumstances of its completion: the troubling marriage of a first movement that sounds the distant tone of last things, oblivious of surface display, with two movements composed twenty years earlier for another sonata entirely. From the patterns discernible in Bach’s working habits, we explain the composition of the new first movement of 1786 as a way of bringing closure to the two movements orphaned in 1785: Bach putting his house in order. We are left then with an aesthetic problem of a certain gravity. This first movement, articulated in a washed prose that evokes lateness and even exhaustion, seems remote from the perfunctory stereotypes of those movements from 1766 that are now attached to it.

But what of that other sonata in C minor, the one for Breitkopf? Its two final movements, composed in 1785 to complete a first movement composed in 1766, issue from an ear tuned to other sensibilities. In this case, because the first movement constitutes music of some substance, the contradiction is perhaps less conspicuous. That may be, but the result is nonetheless a hybrid whose movements were composed at different times and in different circumstances. The ethics of textual scholarship will of course demand that we live with these contradictions: the author’s text, on this account, is inviolate. But it seems to me that a critical inquiry must venture beyond the opaque scrim of such textual stagings. Indeed, the documents in this case—these six movements patched together for purposes that we cannot fully explain—powerfully suggest an argument along different lines. At stake is the viability of the first movement of the later sonata, and its value as an extreme expression of what might be called Bach’s “late style.”

It does not take much imagination to recognize that the two movements composed in 1785 for the Breitkopf sonata offer a much better fit with this movement of 1786, a proposition happily tested in the playing (and called, somewhat coyly, “hypothetical restoration” in figure 4.1). I am not for a moment suggesting that we seek justification for this new arrangement in some organicist-inspired hearing of relationships, thematic or otherwise, between these movements. Rather, it is a more generalized notion of style and voice and even ethos that is acknowledged here. For whatever else one might hear in this newly constructed sonata, its movements do not violate one another, do not incite a contradiction in style whose terms cannot be reconciled. The new sonata—two splendid outer movements, tied together in the briefest Largo of intense expression (“vielsagenden,” pace Suchalla), all of a piece—makes compelling sense, even if we cannot brandish the muted intentions of the composer in its justification.

Intention, however, is a problematical notion in the arts. To invoke it is to claim privilege of some insight—the author’s insight, indeed—into the meaning of the work that the work itself will not allow, and to admit further that there might be some discrepancy between what the work says and what the author claims the work to say. Intention, then, seems the wrong word altogether, for what is really at stake is the authority of evidence. In the later years of the Enlightenment, we must often contend with congeries of text whose internal contradictions do not encourage reconciliation of the kind that I wish to propose here. In the rich portfolio left by Emanuel Bach, these contradictions are extreme and unsettling. To contend with them in any reasonable way means to suspend faith in the romance of the masterpiece—an anachronism in any case—even as we labor through the internal crises of style and idea that they trail behind.

Hayden White’s reading of the historiographers of the late eighteenth century penetrates with great insight to the core of creative thought in the Enlightenment:

The philosophes needed a theory of human consciousness in which reason was not set over against imagination as the basis of truth against the basis of error, but in which the continuity between reason and fantasy was recognized, the mode of their relationship as parts of a more general process of human inquiry into a world incompletely known might be sought, and the process in which fantasy or imagination contributed as much to the discovery of truth as did reason itself might be perceived.69

A few pages later, White captures something critical in Kant’s perception of this phenomenon. Kant, he claims, “apprehended the historical process less as a development from one stage to another in the life of humanity than as merely a conflict, an unresolvable conflict, between eternally opposed principles of human nature: rational on the one hand, irrational on the other” (White’s emphases).70 The great philosopher-historians of the Enlightenment, in White’s view, understood the world, both its present and past, in ironic terms. Surely, the unresolved contradictions in Bach’s manipulation of his portfolio bespeak a certain irony in what might be called his long view of history and his place in it. This we must accept for what it is.

But another distinction suggests itself. The deeper impulses that come into play during the conceiving of the work, and vanish with the ephemera of process, are lost to a later perception of the work, where the perspective is, so to say, constructed and the motives material. At one level, this apparent contradiction between reason and imagination, between the rational and the irrational—irrational, only in the sense that such work emanates in the first instance from no consciously rational process of mind—is manifest in the conceptualizing of the creative work. But at another, the author as self-critical historian, the composer as editor, will now figure the work of imagination in the greater theater in which such work is apprehended. The marketplace again intrudes, with all the dialectical uncertainty that such an enterprise will always signal. When Bach composes the Largo and Presto for the Breitkopf sonata, is his ear tuned to the market, as he seems to claim? Or is his reading of the marketplace a projection of some deeper vision of the creative mind? When he composes a new first movement in 1786, is he hearing the subliminal imprint of those two new movements, composed a year earlier for the Breitkopf sonata? If the Nachlass will allow no interference in how the documents align themselves, the critical ear yet struggles against what it perceives to be an error in judgment. If we are bound to respect the authority of these two sonatas that Bach cobbled together—and to live with their contradictions—we are no less obliged to understand how they coexist in a complex textual web. Unraveling these knots, the critical mind is left to feel its way through the ironies of Enlightenment thought in pursuit of the elusive music of Bach’s last years.

APPENDIX 4A C. P. E. Bach, Sonata in A major, H 270 (Kenner und Liebhaber II, Wq 56/6), complete

APPENDIX 4B Sonata in C minor, H 298, first movement