On his way home to Paris via The Hague, Denis Diderot paused for a few days in Hamburg at the end of March 1774. “I return from St. Petersburg in a housecoat under a fur pelt, and without other clothing, otherwise I should not have missed calling on a man as famous as Emmanuel [sic],” he wrote, in the first of two surviving letters to Bach.1 We know the texts of these letters not from Diderot’s autograph, but (tellingly) from their publication in four literary journals within weeks of Diderot’s visit—the first of them in Claudius’s Wandsbecker Bothe for 8 April.2 The letters are work-a-day: Diderot wants Bach to provide some sonatas for his daughter, and Bach (we must infer from Diderot’s second letter) spells out the terms under which he can agree to the request.3

That Diderot and Bach never met seems quite clear from the circumstantial evidence. In the continuation on Easter Sunday of a letter dated “Sonnabend vor Ostern, 2 Apr. 1774,” the poet Johann Heinrich Voss, describing several visits to Bach during the weekend, adds: “Diderot has traveled through town and written several letters to Bach, asking for the copy of some unpublished sonatas for his daughter, who is an excellent keyboard player.”4 The following day, in a letter to Johann Martin Miller and others of the “Göttingen Grove”poets, Voss writes: “Diderot was here [in Hamburg], but has spoken to no one. He wrote a couple of letters to Bach.”5

The provocations of this near confrontation of two grand, idiosyncratic minds (theatrically staged, it might be inferred from the alacrity with which Diderot’s personal letters were rushed into print) tempts me to juxtapose two of their works: the Fantasia in F# minor, composed by Bach in 1787 (six years after the death of Diderot), a work that plays openly with the idea of Empfindung;6 and a dialogue by Diderot that examines with piercing wit the distinction between the man of genuine sensibility, of sensitivity—of Empfindsamkeit—and the actor who only stages, enacts, mimics such feeling. Unpublished in his lifetime, Diderot’s Paradoxe sur le comédien (The Paradox of the Actor) was much on his mind during the months prior to his journey through Hamburg.7 Had Diderot and Bach actually met, it does not stretch reason to imagine the conversation turning about these ideas that so vigorously probe Enlightenment aesthetic theory.

I begin by again recalling that frequently invoked insight in Diderot’s Paradoxe: “The man of sensibility,” writes Diderot, “obeys only the impulses of nature, and utters precisely nothing less than the cry of his heart; once he moderates this cry or forces it, he is no longer himself, but an actor in performance.”8 Isolating these lapidary words in his penetrating monograph on Johann Georg Hamann, Isaiah Berlin thought he recognized in Diderot’s depiction a sense of self-alienation to which, as he puts it, Rousseau “and much modern psychology have given a central role.”9 For all its insight, Berlin’s reading yet slights the paradoxical effect that Diderot is after. Spoken by “the man with the paradox” (as Diderot calls him), this central thesis in the dialogue does not mean to argue for the primacy of nature, but, rather, for a more complex relationship between the man of feeling, the poet, and the actor. Toward the end of the dialogue, when the antagonists have wandered off, absorbed in their own thoughts, the man with the paradox bursts forth with an uncanny fable of human relations. Diderot gives us the sense of a man possessed:

Here the man with the paradox fell silent. He walked with long strides, not seeing where he went; he would have knocked up against those who met him right and left if they had not got out of his way. Then, suddenly stopping, and catching his antagonist tight by the arm, he said, with a dogmatic and quiet tone: My friend, there are three types—nature’s man, the poet’s man, the actor’s man [l’homme de la nature, l’homme du poet, l’homme de l’acteur]. Nature’s is less great than the poet’s man, the poet’s less great than the great actor’s, who is the most exalted of all. This last climbs on the shoulders of the one before him and shuts himself up inside a great basket-work figure of which he is the soul. He moves this figure so as to terrify even the poet, who no longer recognizes himself. He terrifies us … just as children frighten each other by tucking up their little skirts and putting them over their heads, shaking themselves about, and imitating as best they can the croaking lugubrious accents of the specter that they counterfeit.10

In this stunning evocation of theater, we are struck by the power ascribed to the actor, who becomes the soul of the figure—the poet’s figure—within which he comes to life. In the greater hierarchy of things, the poet’s figure must stand above the actor’s, but in the end, it is the actor who holds the reins. How, by the way, one might transfer this elaborate construct to the performance of music is not quite so routine as it might at first seem: where the poet and the actor are always discrete and even distant from one another, the composer and the performer often inhabit the same body. And yet even in such cases, the composer as a performer of his own work will play out the tensions immanent in Diderot’s subtle conceit.

Diderot’s argument has everything to do with an apparently simple observation on the nature of acting, framed in an apothegm early on in the dialogue: “Extreme sensibility,” he writes, “makes middling actors; middling sensibility produces the multitude of bad actors; in complete absence of sensibility is the possibility of the sublime actor.”11 For Diderot, the “sorrowful accents” that seem to be drawn from the depth of feeling are, by that measure, evidence not of true feeling but of something planned. They are, he writes:

part of a system of declamation; in that, raised or lowered by the twentieth part of a quarter of a tone, they would ring false; in that they are in subjection to a law of unity; in that, as in harmony, they are arranged in chords and discords; that laborious study is needed to give them completeness; in that they are the elements necessary to the solving of a given problem; in that, to hit the right mark once, they have been practiced a hundred times; and in that, despite all this practice, they are yet found wanting.12

And further to this paradox is an imaginary theater of mirrors and reversals in which Diderot now envisions the world as itself a stage enacting madness, from which the cold eye of the poet constructs its play:

In the great play, the play of the world, the play to which I am constantly recurring, the stage is held by the fiery souls [that is, by the people governed by their feelings], and the pit is filled with men of genius. The actors are in other words madmen; the spectators, whose business it is to paint their madness, are sages. And it is they who discern with a ready eye the absurdity of the motley crowd, who reproduce it for you, and who make you laugh, both at the unhappy models who have bored you to death, and at yourself.13

To question this hierarchy, to suggest that within the bosom of the great actor is some fundamental well of sensibility, that actors and poets are no less capable of true feeling than these primary figures of nature, would be to disable the cunning of Diderot’s Paradoxe. It has much to tell us of the Enlightenment mind engaged in an inquiry into the nature of thought and idea, and provokes us finally to interrogate this distinction, implicit in the Paradoxe, between feeling and expression. What, precisely, is this distinction that Diderot is after between the cry from the heart (surely, this is expression of some kind) and the perfectly calibrated gesture of the actor, within whose calculations are choreographed the rhetoric of spontaneity?

Somewhere from within this distinction springs language itself, the origins of which captured the imagination of Enlightenment thinkers: witness Vico’s notion of the beginnings of language, where metaphor precedes the literal and song precedes speech;14 and Rousseau’s similar inclination, in the Essay on the Origin of Languages (1749).15 In Herder’s Essay on the Origin of Language (1770), the dialectical argument leads inexorably to a confrontation of the utterance of passion with a grammar of reason, a confrontation that Bach’s Fantasia will bring to life. For Herder, the acquisition of grammar is not without sacrifice: “For as the first vocabulary of the human soul was a living epic of sounding and acting nature, so the first grammar was almost nothing but a philosophical attempt to develop that epic into a more regularized history.”16 The regulation that comes of grammar takes language in its grip: “the more it becomes simplified, the more it declines: the more it turns into grammar–and that is the stepwise progression of the human mind.”17 And yet it is implicit in all this that grammar itself is not arbitrary, but a natural, if reasoned, consequence of speech.

Music has long been called a language of feeling, and

consequently, the similarities that lie beneath the coherence

of its expression and the expression of spoken language

have been deeply felt.18

We return yet again to these vivid lines with which Emanuel Bach opened his review of the first volume of Forkel’s Allgemeine Geschichte der Musik in the Hamburgische unparteyische Correspondent for 9 January 1788. In Forkel’s view, the efficacy of harmony in the service of a more complex range of expression, only recently achieved, would enable the creation of, as Bach puts it, “einer Musik, die als eine wirklich aneinander hängende Sprache zu unsern Empfindungen reden soll” (of a music that, as a truly coherent language, can speak to our feelings).19

This provocative formulation—more Forkel than Bach20—only aggravates the paradox which Diderot is at pains to articulate. For if music is a language of Empfindung, we want to know with some precision how it negotiates, as language must, among something felt, something thought and something expressed—and, further, whether to identify music as a language of Empfindung means to rule out its capacity to embody language in the rational mode of grammar and syntax; or means, rather, to construe Empfindung as a more complex phenomenon containing within itself—as Herder seems to have believed—the trace of grammar.

The notion of music as modeled on spoken language—even as an intensified instance of it—is often encountered in theoretical discourse in the 1770s. Sulzer, in the article “Gesang” in his Allgemeine Theorie, worries the distinction between speech and song. “Human song,” he proposes, cannot have arisen through the imitation of something songlike in the natural world (the singing of birds is his example). Rather:

the individual tones from which song is formed are expressions of animated Empfindungen. These tones that are forced from man from the depth of feeling [von der Empfindung dem Menschen gleichsam ausgepresste Töne] we shall call tones of passion [leidenschaftliche Töne]. The elements of song are not so much a discovery of man as they are nature itself. The tones of speech are signifiers [zeichnende Töne] which originally served to awaken images of things that shared the properties of those sounds. Today, the sounds of speech are indifferent or arbitrary in this regard; passionate tones, on the other hand, are natural signs of Empfindungen. A sequence of arbitrary tones indicates speech; a sequence of passionate tones, song.21

For Sulzer, there is an immediacy of feeling, of Empfindung, that characterizes the tones of song. Tones do not depict, but express. They are not reasoned and learned, but of nature itself, even as Gesang, like speech, “is the invention of Genius.” “The Fine Arts,” he writes (in the article “Empfindung”), “have two ways of releasing Man’s Empfindungen. ‘If you wish to move me to tears,’ says [Sulzer’s] Horace, ‘then you too must cry.’ This is the one way. The other is the animated depiction or performance of those objects which induce Empfindung.”22 Often invoked, the passage may be found in the midst of Diderot’s lengthy discourse on a painting by Joseph Vernet in the Salon of 1767: “ … but you’ll weep all alone … if I can’t imagine myself in your place.” The reader, Diderot continues, has “a double identity”: is the actor who shudders and suffers and yet remains himself, experiencing the pleasure of the work.23 The contradiction in Sulzer’s formulation, where Empfindung is captured in the creative mind, is played out for Diderot in some amalgam of critical reception and performance—performer and critic as surrogate participants in this act of creation—and reconciled in the mode of paradox.

What, then, can Bach have meant in inscribing “C. P. E. Bachs Empfindungen” above the Fantasia in F# minor, purchasing distance from his own feelings through this evocation of himself in the third person? The inscription curiously appears only on the autograph of the version for keyboard and violin (yet another riddle to which we must return).24 Knowing, as we do, that there can be no verifiably right answer, the call to inquiry and argument is yet implicit in the formulation itself, no doubt heightened in the effort to find a way to put Bach’s phrase into English. Even the genitive case needs parsing, for the good grammarians would make a distinction between simple possession (“Bach’s Empfindungen”) and the formality of a title (“The Empfindungen of C. P. E. Bach”). And then there is that word itself, which English cannot quite capture: feelings, perceptions, sensibilities, sensitivities, sentiments. If any of these might satisfy the local conditions of translation, they each seem misleadingly specific, overly determined, when perhaps Bach means only to suggest some inscrutable journey of the sensitive soul. When we write about Bach’s music, we tend to leave Empfindung (and empfindsam) untranslated, in the unspoken understanding that we presume to know precisely what is meant, knowing all the while that to say so in actual language is to risk a loss in nuance, if not to betray a more fatal misunderstanding.

One gets some taste for the lexical problem in an extraordinary letter that Lessing wrote in the summer of 1768 to Johann Joachim Christoph Bode, then engaged in the translation of Laurence Sterne’s Sentimental Journey. Bode had originally thought to render “sentimental” as “sittlich,” and then tried out a range of other expressions and “Umschreibungen.” Admiring Sterne’s boldness in creating, out of necessity, a new adjectival form for Sentiment, Lessing urges upon Bode the right of the translator to engage in this same creativity. “The English,” he writes, “had no single adjective for Sentiment. For Empfindung, we have more than one: Empfindlich, empfindbar, empfindungsreich: but they each say something rather different. Give empfindsam a try.”25

Often enough, Empfindung is set in opposition to reasoned thought. Such an opposition is at the seat of Türk’s definition of cadenza, in the Klavierschule of 1789: “For the cadenza in its entirety ought to resemble a fantasy created from an abundance of feeling more than a properly worked out piece,” to which is added a footnote that penetrates to the more obscure relationship between experience and feeling: “Perhaps the cadenza could be compared not inappropriately with a dream. We often dream through in a few minutes, and with the most vivid Empfindung,—but without coherence, without clear consciousness—events actually experienced that made an impression on us. So too in a cadenza.”26

By these lights, spontaneity of intuition “aus der Fülle der Empfindung entstehenden”—indeed an intensified Empfindung, “ohne Zusammenhang, ohne deutliches Bewustseyn”—is a defining property of the fantasy, the work conceived in a dreamlike somnambulance. The Fantasia in F# minor has, however, plenty of Zusammenhang, itself the hardest evidence of “deutliche Bewustseyn.” Setting all this against the “regelmässig ausgearbeitete Tonstück” invokes as well one of the grand epistemological problems in Enlightenment aesthetics: how the mind engages in creative thought. Diderot reappears. We are reminded once more of that passage (cited in another context in chapter 1) in the fantasy-like exchange between Diderot and the mathematician D’Alembert. The D’Alembert in the dialogue is having trouble reconciling the actuality of thought—“we can think of only one thing at a time,” he says—with the complexity of constructing vast chains of reasoning, or even, as he puts it, “just one simple proposition.” Diderot responds in another of his penetrating similes, invoking the phenomenon of strings vibrating sympathetically.

Vibrating strings have yet another property: that of making others vibrate, and it is in this way that one idea calls up a second, and the two together a third, and all three a fourth, and so on. You can’t set a limit to the ideas called up and linked together by a philosopher meditating or communing with himself in silence and darkness. This instrument can make astonishing leaps, and one idea called up will sometimes start a harmonic at an incomprehensible interval. If this phenomenon can be observed between resonant strings that are inert and separate, why should it not take place between living and connected points, continuous and sensitive fibres?27

Seizing on the image of sympathetic vibration, Diderot conjures the mind of the philosopher enacting complex thought much as vibrating strings induce harmonics. The process, at once intuitive and involuntary, even incomprehensible, is yet grounded in acoustic principle. In this, the foundational relationship between model and process bears an uncanny resemblance to those passages of enharmony in Bach’s fantasies which set us to analytical hand-springs: the musical work (as fiction, as narrative) means to invoke this fleet, intuitive process that Diderot describes. The paradox returns, for we are left to wonder whether this journey that the Fantasia depicts is an authentic record of some internal, intuitive process or merely a fictional reconstruction of such a process: whether the Empfindung embodied in this or that fantasy is the trace itself—the real thing—or an artifact, an invention.

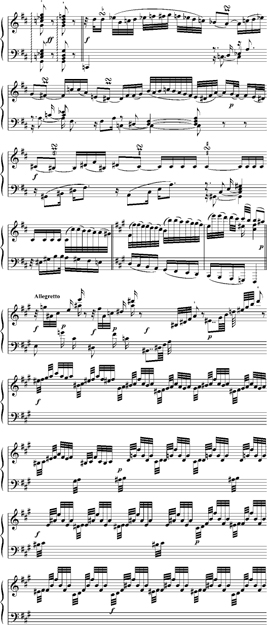

The process is in any case a syntactical one: Diderot’s model has more to do with the connections between thoughts—with the grammar of relationships, rather—than with the substance of thought, of idea itself. Even Türk’s invocation of dream has to do with the intensification of what might be called explanatory process—how events are recalled (a syntactical concept)—and not with the imaging of the surreal. The aptness of Diderot’s conceit to Bach’s Fantasia comes vividly clear in several passages upon which the sense of the work seems to turn. The first of them (shown in ex. 6.1) comes at a moment where the music hovers about a first confirmatory cadence in F# minor. For all its suggestion as leading tone, the E# is led unexpectedly down, through E♭ ! The D♮ in the bass, primed to resolve as ninth to the root C#, is instead displaced up an octave and made over into a leading tone. As it plays itself out, the music expires weakly in E minor, the subdominant of the subdominant, a few cadences away from the middle section: the Largo, which begins in B minor.

EXAMPLE 6.1 C. P. E. Bach, Freie Fantasie fürs Clavier, H 300.

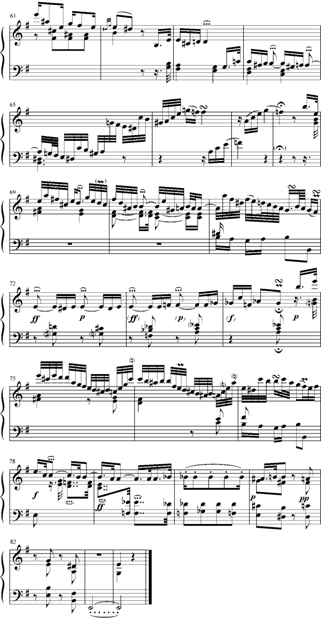

We cut away now to the analogous passage (shown in ex. 6.2), deep in the recapitulation–a recapitulation that begins, by the way, in B minor, a key to which the music continually retreats. The original syntax is broken. Here, finally, is a true half-cadence in F# minor. All the notes are where they belong. But then comes another interruption, and a return to this moment of enharmony, where E minor is now properly established, as though to compensate, retroactively, for the E minor established illicitly, through enharmonic ellipsis, in the exposition. (See ex. 6.3.) The moment is fleeting. E minor dissolves through its own enharmonic game: C# in the bass (again, a ninth displacing a root) is again made over as leading tone, now B#. The music splays hyperbolically out to the registral extremes of the instrument, to (yet again) a dominant of B minor. Obligatory arpeggiations on the way to the final cadence put B minor back in place, as subdominant, breaking off at the augmented sixth before the dominant in F# minor. The ear anticipates C# in the bass. It does not come. Obscurely, an A is sounded, its sheer depth and isolation seeming to touch the empfindsamer core of the work. The player who can resist even the slightest Bebung here works against the signifying, gestural sense of the note and its tactile grain. From this A, the music draws forth one last allusion to the Largo theme, grounding it finally in F# minor.

EXAMPLE 6.2 Freie Fantasie fürs Clavier, H 300.

And it is from this A, and precisely here, that, in the version for violin and keyboard, the music seems to gather itself for the swerve, the modulation, to the new finale. (It is shown in ex. 6.4.) It is not, of course, called “finale,” but that is what it is: a final movement, in sonata form with varied reprises, and in the key of A major: an allegro, a “lieto fine,” very much the “regelmässig ausgearbeitete Tonstück,” in Türk’s phrase. Astonishingly, this is not “new” music at all, but the finale of a sonata in B♭ major (H 212), composed in 1766, a date specified in the Nachlaßverzeichnis and inscribed by Bach on the title page of a contemporary copy.28 On that very page, Bach scribbled “hat noch niemand,” by which he must have meant that the sonata remained out of circulation, a reassuring memorandum to himself that he could pick this pocket without fear of exposure. It seems reasonable to assume that the inscribing of the title page, the note “hat noch niemand,” the autograph of the exceedingly quirky substitute finale (appended to a copy of the sonata now in Cracow), and the arrangement of this old finale as a music with which to close “C. P. E. Bachs Empfindungen” are related acts that date from 1787.

EXAMPLE 6.3 Freie Fantasie fürs Clavier, H 300.

In the duo version, this portentous A is deployed in three octaves, given new timbre, and consequently fixed in time and space: the introverted Bebung of the solitary tone, a moment of obscure contemplation, gives way here to an exhortation. Newly inflected, the note will now be heard to announce the coming of a new music in A major. The reversal of function is riddling, for it would be good to remind ourselves that it is only here, on the autograph of the version with accompanying violin, that Bach inscribed “C. P. E. Bachs Empfindungen.”Whatever Bach meant by Empfindungen, in the sense that it is used here—a question distinct from the one that would probe his intentions in broadcasting the word in this context—I think we might agree that these final measures of the original Fantasia convey a sense of weariness, of exhaustion. The music sinks, and seems to disappear into the wondrous buzzing of the lowest strings in the clavichord, as though Bach himself, in a fiction suggestive of autobiography, wished to expire in his music.

EXAMPLE 6.4 Clavier-Fantasie mit Begleitung einer Violine, “C. P E. Bachs Empfindungen,” H 536.

Brazenly different in just this respect, the duo puts on a different face. (Its final bars are shown in ex. 6.5.) If these two musics are to be reconciled, it will not help to construct a variorum that postulates a preferred “final version.” Veränderung, a concept seemingly hard-wired in Bach’s musical imagination, seems much to the point here. We are witness to it here on three levels: the Fantasia, as work, is altered; the new finale in A major is a Veränderung of the finale of an earlier Sonata in B♭; finally, the reprises in the finale are now written out: veränderte Reprisen in the strictest sense. Perhaps one might wish to claim that the two versions play out, and egregiously so, Bach’s lifelong ambivalence as to public taste and intellectual privacy. Bach’s inscription aggravates this ambivalence, for it is the more public redaction of the work that draws it forth: “C. P. E. Bachs Empfindungen,” as though to market these most intimate, confessional thoughts. Here again are the traces of paradox, for it is unclear what it would mean to take Bach’s inscription at its face.

EXAMPLE 6.5 Clavier-Fantasie mit Begleitung einer Violine, H 536.

The image of Bach in his final years withdrawing into his clavichord comes clear in another famously private piece: the Rondo in E minor from 1781, the “Abschied von meinem Silbermannischen Claviere, in einem Rondo,” as it is called in the Nachlaßverzeichnis.29 The circumstances that brought about this farewell are obscure: Bach seems actually to have given away his fabled instrument to an admiring nobleman, Dietrich Ewald von Grotthuß, attaching to it the Rondo as “proof,” he writes to Grotthuß, “that one can also compose plaintive Rondeaux, and that on no other Clavier but yours can they be played well.”30

Even while Bach’s instrumentarium retained two other clavichords, the depth of sentiment in the Rondo might suggest of Bach’s Abschied that it signifies loss in a metonymical sense: the loss of the means to make such music, the passing of the clavichord as an instrument whose intimacies were no longer cherished. Again, a remarkable essay by Diderot springs to mind: in “Regrets sur ma vieille robe de chambre” (published in 1772), the parting with a comfortable old dressing gown worn during the author’s less affluent days, stained from the wiping of ink from his pen—“the badge of an author,” he writes—unleashes a meditation whose sentiments resonate in sympathy with Bach’s “Abschied.”31 But there is a deeper message here: “Listen, and I will tell you what ravages Luxury has made since I gave myself up to the systematic pursuit of it.” The gown is only a symptom, in its intimacy the closest to the man himself, of a complete makeover from the honest comforts of poverty to the stiff artificialities of wealth. Pondering the ironic inevitability of the track to success, Diderot yet betrays a flicker of ambivalence: “Fine manners have ruined many a man; the most sublime taste is not exempt from change; change means throwing things away, turning things upside down, building something new… . Thus our delicacy produces many fine things, and at the same time many evils.” Bach, of course, does not replace his beloved Silbermann with something new—at least we do not know that he was clearing out space for a forte-piano. But in his parting with it is felt an irrecoverable and inevitable loss.

Bach’s inscriptions, I mean to suggest, evoke literary works in more than a superficial sense. As title, “C. P. E. Bachs Empfindungen” conjures Yoricks empfind-same Reise durch Frankreich und Italien, as Sterne’s Sentimental Journey was known in Bode’s translation. The bold play of syntax, a reflection of the empfindsamer experience, drives the prose of Sterne (and Diderot) in much the way that it drives Bach’s music. The famous final line of the Sentimental Journey breaks off in flagrant mid-sentence: “So that when I stretch’d out my hand, I caught hold of the Fille de Chambre’s——.” Abandoned to complete the thought, to imagine how it might be completed, and to wonder why it was not given to Yorick to do so, the reader is made to react empathetically with him: not in the distanced, formal rhetoric with which earlier works would engage their readers, but with a new immediacy and intimacy.32 The reader, embraced by the work in this way, is less inclined to draw back, to analyze form as distinct from content and “feeling.” The relationship between the work and its reader is renegotiated, trafficking now in shared Empfindungen.

Calling to mind several instances of such mid-flight endings in Bach’s music, this new conceptualizing of syntax works itself deep into the fabric of the musical work (see ex. 6.6, and appendix 10F and G). Admittedly exceptional, these few instances in which Bach’s final bars tamper with the protocols of closure may be heard as symptoms of a deeper engagement with a syntactics of Empfindsamkeit. The final paragraphs of Bach’s “Abschied” Rondo (shown in ex. 6.7) probe the limits of coherence to an extreme. The breaking off at the fermata at m. 68—exceptionally undecorated—will, by simple harmonic parsing, be heard as a Neapolitan-sixth: cadencing must follow. But the rondo theme, in yet another variant, resumes as though nothing had happened, unresponsive to the Neapolitan, whose intervals continue to sound, dissonantly. The theme comes again to its cadence, but closure is again denied, the music moving up in minuscule chromatic increments to that unresolved harmony, no longer a Neapolitan, but a dominant seventh in first inversion: the F♮, left hanging in m. 68 as an appoggiatura to E (the fifth of the minor subdominant), is now more powerfully endowed as the root of a seventh chord, finally displaced at the fermata in m. 74 by G♭, a flat ninth above the dominant in the remote key of B♭ minor. The fermate have bonded together. The breach between this fermata and the final iteration of the Rondo theme, still deaf to its antecedent, touches a nerve. Again, the theme will not close, and at m. 79, the dominant on F, now in root position, fortissimo, is given full play, along with its neighboring G♭. Imperceptibly, somewhere between mm. 80 and 81, this G♭ masquerading as a flat six to the dominant in B♭ minor, is reclaimed as F#: in commonplace language, the root of the dominant of the dominant in E minor. But the effect is not commonplace. As the Rondo vanishes, pianissimo, over a tremulous E alone in the bass, the ear strains to follow. What has it heard? Is this closure, or only an end?

EXAMPLE 6.6 C. P. E. Bach, Rondo in C minor, H 283, Kenner und Liebhaber V (1784).

When, at the close of the Rondo—and earlier, of the Fantasia—we are led to ask such questions, we are probing empathetically, with Herder’s Einfühlung, into the inner workings of the music, seeking sources and roots and the elusive clues to meaning. That surely is what Bach intends, for his music engages in this probe, even if the Empfindungen that reside somewhere in its depths are planted there by the cunning, the craft of the composer.

EXAMPLE 6.7 C. P. E. Bach, “Abschied von meinem Silbermannischen Claviere, in einem Rondo,” H 272 (1781).

“But it’s getting late,” observes Diderot’s “man with the paradox” at the end of the day. “Let’s go have some supper.” We wander off with him, our appetites whetted: for it is in the nature of paradox that it does not choke off thought in self-righteous dogma, but rather excites ever new waves of reflection. And that is why, I think, we are forever returning to Bach’s late keyboard music. Riddled in paradox, it drives us back to the condition so wondrously depicted in Diderot’s conceit. The actor shutting himself up inside that “great basket-work figure of which he is the soul” is now the player at the keyboard. Reading for the sensibilities of Bach’s music, the dispassionate performer must now put on the masks figured in Bach’s script—must convince us, then, that we are hearing not the player in mask but rather the beating heart of the music and its living soul.