One cannot truly understand what men are saying by merely applying grammatical or logical or any other kind of rules, but only by an act of “entering into”—what Herder called “Einfühlung”—their symbolisms, and for that reason only by the preservation of actual usage, past and present. Consequently, while we cannot do without rules and principles, we must constantly distrust them and never be betrayed by them into rejecting or ignoring or riding roughshod over the irregularities and peculiarities offered by concrete experience.1

Isaiah Berlin here captures one aspect of the theory of language that is a central topic of his penetrating study of Johann Georg Hamann (1730–1788). The stubborn obscurity of Hamann’s thought, and in particular its location of meaning at the cradle of language, before the exercise of reason and analysis, is strikingly pertinent to an understanding of the music of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714–1788), whose eccentricities set his contemporaries to similar feats of exegesis. If the two never met, the picture of a confrontation between two minds so uncompromisingly original challenges the imagination. Their place at the source of a new mode of thought affecting arts and letters—a place in the midst of Aufklärung (Enlightenment), askew in posture and even contrary to its common tenets, and yet a function of them—is uncommonly close.

“The Origins of Modern Irrationalism,” the subtitle of Berlin’s monograph, is suggestive as well for the place of Emanuel Bach’s music in the course of a history that in some sense may be said to begin here, in these idiosyncratic works that touched his contemporaries as had no others. The privacy of Bach’s language, indeed the tendency of his music to speak in linguistic neologisms, set it apart from the common currents of musical style in the 1790s and beyond, so that his music, in the genuineness of its expression, was valued by Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven more for what it suggested of an aesthetics, of an attitude toward art, than for the artifices of its composition.

What, precisely, is this irrationalism that Berlin holds as a reactionary counterpoise to the power of reason that he understands as the foundational principle of the Enlightenment? For Berlin, the wing-span of the Enlightenment begins in the Renaissance and extends to the French Revolution “and indeed beyond it.” Its tenets were clear, and Berlin’s formulation of them clearer still: “The three strongest pillars upon which it rested were faith in reason …; in the identity of human nature through time and the possibility of universal human goals; and finally in the possibility of attaining to the second by means of the first, of ensuring physical and spiritual harmony and progress by the power of the logically or empirically guided critical intellect.”2 To define the Enlightenment in these terms and with such enviable clarity is to marginalize as contrary and negligible a body of vigorous inquiry, no less enlightened, that ventured to understand the dissonance between what might be called the exercise of reason and the empirical play of sensibilities—to understand, that is, how reason and feeling (better, Empfindung, a word far richer in meaning) might be reconciled, and further, to locate the processes of thought itself. How, after all, can we know, in the course of our thinking, that we are in the presence of “rational” thought? It is a question of this kind that lurks behind a passage in Diderot’s Jacques le fataliste that is as witty as it is unsettling: “It’s that, not knowing what is written above, we know neither what we want nor what we do. So we follow our fantasy, which we call reason, or our reason, which is often only a dangerous fantasy that sometimes turns out well and sometimes badly.”3

Diderot plays more earnestly with the unpredictable causalities of thought in a memorable passage in the Conversation Between D’Alembert and Diderot. Seeking an explanation for how the mind can embrace not “vast chains of reasoning of the kind that range over thousands of ideas, but just one simple proposition,” the mathematician d’Alembert cannot move past the observation that “we can think of only one thing at a time.” Diderot, his interlocutor, now puts in play this grand conceit of the vibrating string that resonates “long after it has been plucked,” and that sets other strings to vibrate sympathetically: “it is in this way that one idea calls up a second, and the two together a third, and all three a fourth, and so on… . This instrument can make astonishing leaps, and one idea called up will sometimes start an harmonic at an incomprehensible interval. If this phenomenon can be observed between resonant strings which are inert and separate, why should it not take place between living and connected points, continuous and sensitive fibres?” The philosopher is then a kind of clavichord:

We are instruments possessed of sensitivity and memory. Our senses are so many keys which are struck by things in nature around us, and often strike themselves… . There is an impression which has its cause within the instrument or outside it, and from this impression is born a sensation, and this sensation has duration, for it is impossible to imagine that it is both made and destroyed in a single, indivisible instant. Another impression succeeds the first which also has its cause both inside and outside the animal, then a second sensation, and tones which describe them in natural or conventional sounds.4

The reasoning mind in action, so to say, is set in motion by the sensibilities of the entire nervous system. The mind and its thoughts do not exist outside this sensitive organ that is Man. Reasoned thought has its involuntary, irrational aspect.

The daring leap from Diderot’s “thinking” clavichord to the machinery of the creative mind and the creation of art returns us to the theater of language. For Hamann, the beginnings of creative thought are one with the beginnings of language. Without language, thought itself is not possible. As Berlin puts it, Hamann is among the first “to be quite clear that thought is the use of symbols, that non-symbolic thought, that is, thought without either symbols or images—whether visual or auditory, or perhaps a shadowy combination of the two …—is an unintelligible notion.”5 This notion of thought in lockstep with the creation of a language of symbols necessary for its expression is a provocative one for the imagining of how music is conceived. If it is a commonplace to acknowledge that musical thought and its actuality in some linguistic, voiced utterance constitute an inseparable identity, Hamann’s account encourages us to think freshly about the complexity, the idiosyncrasy, the originality of the musical idea, to think of composition not as the clever play with inherited conventions, but as a bolder adventure in which language is always invented de novo.

In their very different ways, Diderot, Hamann, and Herder interrogate what, by the 1770s, had become the common currency of Enlightenment thought. The name itself—Aufklärung—had come to dominate the discourse in a self-conscious effort to understand what it signified. “Was ist Aufklärung?”—what is Enlightenment? The question, innocently put in a Berlin monthly of 1783, provoked a brace of replies by, among others, Moses Mendelssohn and Immanuel Kant. “Enlightenment is mankind’s exit from its self-incurred immaturity,” begins Kant. “Sapere aude! Have the courage to use your own understanding! This,” he claimed, “is the motto of enlightenment.”6 Hamann’s reaction to Kant’s essay, a cynical sneer wrapped in a characteristically impenetrable linguistic knot, is impatient with the question itself: “The enlightenment of our century,” for Hamann, “is a mere northern light… . All prattle and reasoning [Raisonniren] of the emancipated immature ones, who set themselves up as guardians of those who are themselves immature.”7 A far clearer sense of his quarrel with Kant will be found in Hamann’s “Metacritique on the Purism of Reason” (1784).8 Here again it is the axiomatic priority of language that controls the discourse: “If it is still a chief question how the faculty of thought is possible—the faculty to think right and left, before and without, with and beyond experience—then no deduction is needed to demonstrate the genealogical superiority of language.”9

“The oldest language was music… . The oldest writing was painting and drawing,” writes Hamann, casting the beginnings of thought in boldly aesthetic terms.10 This seems an echo of Vico’s reflections on the primacy of metaphor in the evolution of the earliest languages, and of his penetrating notion that for the first poets every metaphor “is a fable in brief.” In the extended and frequent exchanges with Herder on the nature of language and its origins at the beginning of thought, Hamann is vituperative, and he is obscure—intentionally so, it often seems. It is in this context—mindful of Hamann’s notion that “language and the forms of art are indissolubly one with the art itself”11—that we turn to Emanuel Bach, whose music so pointedly exemplifies this refusal to separate out the “forms of art” from the thing itself, whose music seems (and assuredly seemed to his contemporaries) to wrestle with the creation of language.

Language is what we think with, not translate into: the meaning of the notion of “language” is of symbol-using. Images came before words, and images are created by passions.12

This sequence—“passion, image, word”—indeed, the very act of putting them in sequence, suggests perhaps the slightest dissonance with a phenomenon that Hamann (as Berlin understands him) is at pains to establish: the simultaneity of feeling and expression. The gestural aspect of Bach’s music plays out this linguistic notion with a vividness unmatched in other arts.

That Bach’s music was understood to negotiate its meaning in linguistic terms was manifest early on. In the entry “Sonata” written in the early 1770s for Sulzer’s Theorie der schönen Künste, its author J. A. P. Schulz singled out Bach as the composer whose works demonstrate “the possibility to infuse character and expression in the sonata.” Most of Bach’s sonatas, he continues, “speak so clearly that one thinks he is hearing not notes so much as an understandable language that rouses and maintains our imagination and feelings.”13 Forkel went further, taking the Sonata in F minor, published in the third collection “für Kenner und Liebhaber” (1781), as a provocation to write seventeen pages—a “Sendschreiben” (a communication), he calls it—toward a definition of Sonata.14 The prose has the experimental ring of the empiricist sorting through evidence of a new kind, for each of Emanuel Bach’s new works was met with stunned acknowledgment of its originality. Forkel seeks to come to grips with a “difficult” work that was perceived to set loose conceptual challenges: the extreme case, forging its own rule, that must yet be reconciled with a formal concept resilient enough to accommodate the quiddities of this sonata within a repertory itself dense with idiosyncratic specimens.

“When I think of a sonata,” Forkel begins, “I think to myself of the musical expression of a man transfixed by feeling or inspiration, who endeavors either to sustain his feeling at a certain point of spiritedness (when, for example, it is constituted in a desirably agreeable sensation); or, if it belongs to the class of unpleasant feelings, to reduce it in intensity, and to transform it from a disagreeable feeling to an agreeable one.”15 Who is this subject given to transform his feeling, his inspiration, into expression? Is it the composer who is thus transfixed, or does the music construct some fictive inner voice, a figure of narrative? If there is a confusion of persona in Forkel’s personification, the formulation yet suggests the spirit of Herder’s Einfühlung, this “entering into their symbolisms” as a way of understanding what is being said in this language without cognates.16 A few pages later, Forkel comes at the problem from another angle:

A series of highly spirited concepts, as they follow upon one another according to the rules of an inspired imagination, is an Ode. Just such a series of spirited, expressive musical ideas [Ideen (Sätze)], when they follow upon one another according to the precept of a musically inspired imagination is, in music, the Sonata.17

The simile again has its root in something linguistic. Forkel is careful to avoid the suggestion that the form of the ode in any of its particulars—its verse structure, its rhyme patterns, its meter, its prosody—is at issue here. Rather, it is the elevated tone of the ode, the complexity of syntax trafficking in lofty concepts, that Forkel takes as exemplary for the sonata. In Forkel’s equation, Begriffe (concepts) in the Ode become Ideen (Sätze) in the Sonata. In the sonata, ideas are indistinguishable from Sätze: the syntactical element—the phrase, the gesture, the theme as an elaboration of such morphemes—is itself the “idea.”

Forkel returns to his opening conceit. The Empfindungen earlier ascribed to this fictive personification of the sonata now assume a substantive role in what might be called the meaning of the work. For Forkel, the aesthetic achievement of the sonata lies precisely here, in a natural tension between “Begeisterung [Inspiration], or the extremely spirited expression of certain feelings,” and “Anordnung [Arrangement], or the appropriate and natural progression of these feelings into similar and related ones, or into those more distant.”18 In the end, it is this fine discernment “to join refined and abstract taste with passionate imagination, to induce order and design in the progress of Empfindung” that is “the summit of art both for the genuine composer of sonatas and the poet of odes.”19

Forkel is much absorbed in the phenomenon of Empfindung as the principle matter in the work of art. This is not the implacable, fixed “affect” identified with Figur in the music of the Baroque. Empfindungen have a way of changing, often quixotically and unpredictably. Forkel advocates control. The work of art will be “governed” by “a principal Empfindung; similar secondary Empfindungen; Empfindungen dismembered, broken up, that is, into their separate components; and contradictory and opposed Empfindungen, which, when they are put into a fitting sequence, then constitute in the language of Empfindungen that which, in the language of ideas, or in true rhetoric, are the well-known figures, established in our natures: exordium, proposition, refutation, affirmation and the like.”20 Here, at the heart of Forkel’s elaborate effort to get at such music, is a recognition of the aesthetic appeal of the irrational and the urgency to control it through the formal conventions of rhetoric: the ballast of tradition as counterpoise to the flight of inspiration.

Music, then, speaks in the “Sprache der Empfindungen” but emulates the linguistic syntax of the “Sprache der Ideen.” The musical Idea, earlier equated with this linguistic notion of “Satz,” is now defined as “Empfindung.” This is the word without which Emanuel Bach’s music cannot be construed. What, precisely, does it mean?21 Forkel will no doubt have known the lengthy article under this entry in Sulzer’s Allgemeine Theorie, whose opening lines are worth having: “This word possesses a psychological as well as a moral meaning… . Used in the first, more general sense, Empfindung is to be understood in contrast to clear knowledge, and signifies some image (Vorstellung) only in so far as it makes a pleasing or displeasing impression upon us, affects our desires, or awakens ideas of good or evil, the pleasing or the repugnant.”22 For Sulzer, the foundational difference between Empfindung and Erkenntniß (cognitive knowledge, perception) allows that the one may even contradict the other: what the former calls good, the latter may reject.23

When Forkel speaks of “Empfindungen dismembered (zergliederte), broken up (aufgelöste), that is, into their separate components,” he is describing what commonly happens to thematic material. The thematic substance of the work is understood to be linguistically conceived, and thus subject to the permutations of syntax. These syntactic constructions each express—better, embody—an Empfindung, by which Forkel must mean something akin to a sentiment conveyed in the thematic figure (broadly defined). It is not the sentiment that is broken up into smaller units, but the thematic figure that conveys it. For Forkel, the Empfindung is at once something observed and apprehended in the formal, syntactical sense, and something felt. Just how these two aspects are related, and even whether they are separable, is an imponderable that Forkel will not pursue.

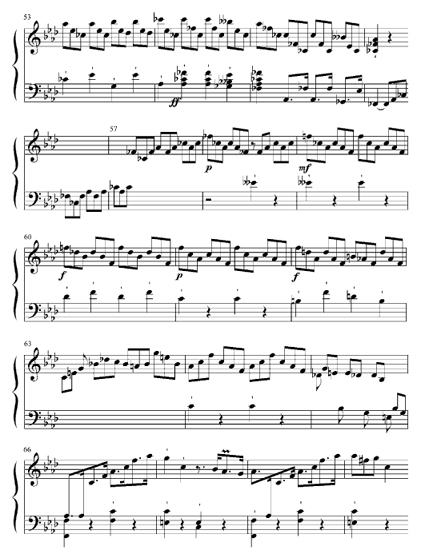

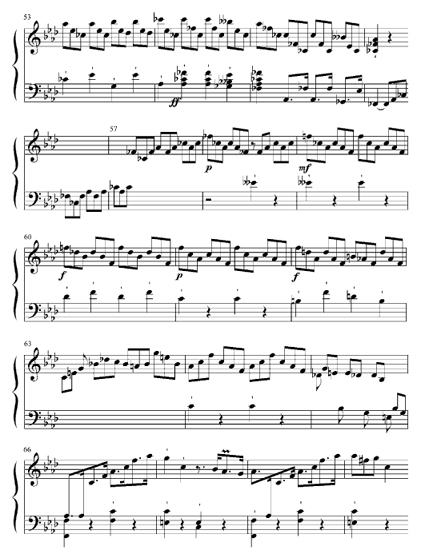

“You’ve perhaps not found much beauty in that place in the second part of the first Allegro, where the modulation moves through A♭ minor, F♭ major, and from there returns in a rather rough manner to F minor,” writes Forkel, coming finally, on the very last page of the essay, to the actual notes of the sonata. (The passage is shown in ex. 1.1). “I must confess that, considered quite apart from its connection to the whole, I too haven’t found much beauty in it. But who finds beauty in the hard, rough, violent outbursts of an angry and resentful man? I am quite inclined to believe that Bach, whose sensibility is otherwise always so exceptionally correct, has not in this instance been betrayed by a false sentiment, and that under such circumstances, this difficult modulation is nothing other than the accurate expression of what should and must be expressed in this instance.”24

Forkel was not the last to focus on this difficult passage in Bach’s sonata—von Bülow, Baumgart, Bitter, Riemann, and Schenker all had a shot at it25—but in one sense, his is the most valuable, in that it conveys a contemporary perception of rare insight: the passage may be rude and impenetrable, but it is true to the meaning of the piece. More to the point, Forkel allows himself to address this passage in isolation—to speak of it aesthetically as though it were self-contained—only conditionally, “considered quite apart from its connection to the whole.” Such passages cannot be understood as though they were not part of something larger, Forkel suggests. The concept of structural dissonance, of the dissonant episode as central to the story of sonata, is strongly implicated.26

EXAMPLE 1.1 C. P. E. Bach, Sonata in F minor, H 173 (Wq 57/6), first movement.

Sketches and the Improvisatory

Sketches, when they are by the great masters, are often more highly prized than works more completely realized, for all the fire of imagination, often dissipated in the execution of the work, is to be met in them. The Entwurf is the product of genius. The working out is primarily the doing of Art and of Taste.27

Thus, Johann Georg Sulzer invites us to the window of the artist’s soul. If it is graphic art, principally, that Sulzer entertains, music might lay equal claim to this understanding of the matter. At another place, a similar thought evokes these lines: “Like the first sketches of the draftsman, the fantasies of great masters, and especially those that are performed out of a certain abundance of feeling and in the fire of inspiration, are often works of an exceptional power and beauty that could not have been composed in a reflective state of mind.”28 The idea of sketch is intimately bound in with the notion of Begeisterung (inspiration), a topic that inspired Sulzer to an inquiry into the physiological root of it all.

For Sulzer, the sketch itself acquires value as the rare evidence of a mysterious process: a glimpse of the artistic mind in the act of creation. His notion of the sketch, a hieroglyph of artistic meaning, resonates with Hamann’s view of the origins of language. For both Sulzer and Hamann, meaning and expression, in some sense synonymous, are to be found in the utterance—unmediated, unreasoned, inspired. Inspiration (Begeisterung) was understood as a powerful and indispensable state of mind from which would emanate the utterance—as sketch, as fragment, improvisatory and unfinished: the beginnings of works whose refinement and completion, invoking later waves of inspiration, would depend on more reflective, less impassioned states of mind.

Sulzer was preceded in these thoughts by Denis Diderot, writing of some sketches by Greuze in the Salons of 1765. “Sketches commonly have a fire that the painting does not,” he begins. “This is the moment when the artist is full of fervor, pure inspiration, without any of the careful detail born of reflection; it’s the painter’s soul spread freely over the canvas. A poet’s pen, the skillful draftsman’s pencil seem to frolic and amuse themselves. A rapid thought finds expression in a single stroke.”29 For Diderot, the appeal is much tied in with the critical enterprise: “the more expression in the arts is ill-defined, the more the [critic’s] imagination is at ease.”30 If there is some confusion here between the unmediated inspiration of the creative act and the task of the critic to read meaning in these inchoate signs, Diderot compounds it in the following lines, where the specificity of meaning in vocal music is set alongside music without text: “I can make a well-constructed symphony say almost anything I like.”31 Diderot’s “anything” naively disables the elocutionary specificity of music to say precisely what it means.

Sulzer’s idealized Entwurf and Diderot’s sketch are graphic artifacts. The artist’s vision is recorded directly through the drawing hand. For the composer, the utterance is expressed less directly. The Entwurf has something to do with performance. The vision is realized in an imagined performance, then immobilized in a notation that may specify too much, or not enough. The writing hand serves the composer not quite so truly as the drawing hand the artist. If the composer’s sketch does not speak as eloquently as the draftsman’s, that is because sketches only stand for an imagined performance, at another remove from the inspired utterance.

The hand then becomes the medium, as the conduit that guides performance (even as it appropriates the physiological grain of the voice), and as writer. We scrutinize the autograph—the Handschrift—for these obscure signs of transference, signs that the writing of music, no longer a mechanical act of translation, actualizes the bringing to life of an imagined utterance. In the sketch notation of a Beethoven, the evidence of such transference needs no lengthy argument. The signs are there to be deciphered.

The sketch, as it partakes of this quality of utterance, has something to do with what musicians call improvisation. The Romantics sought in their music to convey the suggestion of the improvisatory. Work as sketch. The sketchlike as work. Sulzer’s model is turned on its head. Beethoven had more than a little to do with the reversal: the opening of the Piano Sonata, Opus 101, made to sound as if we were witness to the spontaneous creation of ephemera; the feigned innocence of the search for a fugue subject after the Adagio in Opus 106;32 the deep C# and the arpeggiation that unfolds above it at the outset of Opus 31, no. 2 (a topic to itself in chapter 8); an arpeggiation of another kind at the Adagio espressivo in the first movement of Opus 109 (another topic to itself, in chapter 11)—these each cast the performer (tellingly, always a pianist) in the role of creator, acting out the sense of Begeisterung implicit in the idea itself. The composer inscribes himself in the performance. At the end of a laborious creative process, the work pretends to a spontaneous birth.

No wonder that the contributors to Sulzer’s encyclopedia were intrigued by reports of a device that could accurately record keyboard improvisations in notation.33 What might seem a naive quest to locate the source of the improvisatory leads us to a further distinction: formal improvisation as a display in public performance, on the one hand; and the private, inner improvisation that is innate in the act of composition, the indispensable trace that distinguishes the work of genius from hackwork. If this “inner” improvisation resists the kinds of documentation that we routinely demand of empirical evidence, the Beethoven sketches, that fraction of the process that was caught in writing, constitute a precious legacy, for they vividly preserve those compositional improvisations, at once spontaneous and reflective, that a mechanical recording device might well have captured had it been privy to Beethoven’s workshop.

This generic distinction is however a vulnerable one, fraught with paradox. One of its aspects, one source of the Romantic inclination toward a state of perpetual improvisation, might again be isolated in the thought of Emanuel Bach, for whom improvisation was at once a practice, a topic of pedagogy, and a compositional genre. And it is precisely in this last sense—improvisation as genre—that the paradox is engaged. This is perhaps nowhere more eloquently observed than in the final pages of Bach’s Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen, in the chapter titled “Von der freyen Fantasie” (to which I shall return more than once in the studies that follow).34 Here, Bach makes a categorical distinction, represented in two depictions of a Fantasy in D major: a Gerippe—a skeleton—in which the bass, with its intervalic figures, is written out in the text of the final paragraph, in note values whose relationship to one another means to guide the larger rhythms of what Bach calls the Ausführung, which is engraved on a separate plate and tipped into the text (both are shown in fig. 5.1). Clearly, the Gerippe is premeditated, reasoned, planned. The Ausführung is not—or rather, is meant to suggest that it is not. The word is itself suggestive of that which is performed, even if its meaning is not limited to the English “performance”; it is the word that Sulzer, in the epigraph above, opposes to Entwurf. The paradox resides precisely here, in the writing out, in elaborate detail, of this “freye Fantasie.” Decidedly not improvised, the degree of premeditation attending its creation is perhaps even greater than that of the Gerippe from which it is meant to be adduced. If Forkel’s Anordnung and Begeisterung are at play here, it is not in simple equation with Gerippe and Ausführung, but enmeshed in a rather more convoluted dialogue.

Genre intrudes here as well. The Fantasy is of a kind meant to sound as though improvised. In the act of true improvisation, the composer and the performer are one, and the troubled relationship between composition and performance dissolves. When improvisation is feigned, the relationship is problematized. The performer wears the composer’s mask. The composer, free now to invent the signs of the improvisatory, is driven back to first things, to that state of mind that would capture the “Feuer der Einbildungskraft”—the fire of imagination—that Sulzer perceives in the sketches of the great masters. The conventions of formal composition are suspended. The music means to suggest a purity of idea—idea removed from the constraints that such formal limitations as sonata, dance, fugue impose. In the theater in which Berlin’s “origins of modern irrationalism” are played out, the figure of Emanuel Bach comes alive.

The “freye” fantasy, as Bach named it, acquired its own set of conventions: one can easily enough identify such a work from the symptoms of its discourse, symptoms that all such works seem to share. In a sense, the failure of the fantasy as a self-perpetuating genre is precisely in the exposure of its illusory game, in which the more serious enterprise of sonata (and all the permutations that take its formal imperatives as a given) is challenged by that which pretends to the profundities of original creation, but which too often suggests only the contrivance of improvisation. In the late eighteenth century, the test of genius lay in the ability to improvise—truly to improvise—a sonata, a fugue, variations on a theme given: the categorical distinction between inspiration and reason is here collapsed.

This thin line drawn to distinguish these two senses of improvisation—as a public, performed display of the intuitive, controlled by the clock of “real” time; as composition internalized, where the clock is written into the work—invites its own destruction. As a topic of historical inquiry, the boundaries that separate the two are crossed in perpetual flight from one another. Composition, one might say, is a flight from the anxieties of inspiration; improvisation, from the constraints of convention. Ludwig Tieck, writing of Beethoven in 1812, captures this notion vividly: “he seldom follows through a musical idea or theme, and, never satisfied, leaps through the most violent transitions and, as though in restless battle, seeks to escape from imagination itself.”35 And yet strict composition—“die Kunst des reinen Satzes,” in Kirnberger’s stern title—seeks the spontaneity of inspiration even as the improvisatory slips unwittingly into its own conventions.

Fragments by classical authors, whatever their species, are priceless. Among musical fragments, those by Mozart certainly deserve full attention and admiration. Had this great master not left behind so many completed works in every species, these magnificent relics alone would constitute an adequate monument to his inexhaustible Geist.36

Not quite “works,” the Mozart fragments have nonetheless found an ear among the devotees of his music, and for several reasons. For one, they have about them the aura of spontaneity, of the immediacy of composition—a proximity to the creative act—even if it is now clear that the works actually completed by Mozart do not differ appreciably in this regard. Pregnant with possibility, they whet the appetite for what might have been, inspiring the author of our epigraph—Constanze Mozart, as it turns out—to endow the fragments with aesthetic value, for it was naturally in her interest to sell the fragments for the highest possible price. “Haven’t even the briefest fragments of famous writers—Lessing, for example—been published?” she wrote coyly to Breitkopf in a letter of June 1799. “They ought to be consistently instructive, and the ideas in them could even be used by others and brought to completion.”37

Surely there can be no argument with the view that Mozart’s fragments do not aspire to that condition of fragment so cherished by the Romantics, for whom the completed work, ever contested, is apprehended as unfinished at its core. And yet the Mozart fragments signal aspirations of another kind. Paradoxically, it is precisely in what they portend of a finish forever lost that many of the Mozart fragments stake their claim to aesthetic value. The distance between this portent of profound, unrealized finish and a completion ex post facto in the hands of even the most inspired epigone is simply immeasurable.

Writing in 1799, Constanze’s view of the fragment may well have been inspired by the bold ideas of her younger contemporaries. These new sensibilities were sharply etched in Friedrich Schlegel’s “Athenäums-Fragmente” (as they came to be known), published in 1798, in among which is this now famous aphorism: “Many works of the ancients have become fragments. Many works of the moderns are fragments at birth.”38 “Irony,” writes Schlegel elsewhere, “is the form of paradox”—a thought laced with an irony of its own.39 The irony that charges Schlegel’s play on the two conditions of fragment—the one imposed by the accidents of time, the other inherent in the poetic idea—might be extended, with appropriate modulation, to a paradoxical opposition in the fragments of Mozart and Schubert. We call them fragments merely because they have survived in an unfinished state, and yet each has a story to tell, from which might be read the signs that would suggest why they remained unfinished. This is not what Schlegel means by “fragments at birth.” The works that he has in mind are complete, even if they simulate the condition of fragment. In the fragments of Mozart and Schubert it is tempting to perceive the converse: the unfinished as a station to-ward some imagined and intended completion. Schlegel’s aphorism will not hold, and yet it continues to insinuate itself. Are there fragments by Schubert—an avid reader of Schlegel, it will be recalled—of which it might be claimed that their unfinishedness bears the trace of this Romantic disinclination toward finish?

In contending with an “epistemology of fragment” (as I do in chapters 13 and 14), I mean to probe the spaces that separate Mozart from Schubert, from both of whom we have inherited a canonical repertory of unfinished works. For Schubert no less than for Mozart, the fragment captures a moment in the gestation of the work. The fragment has something to do with sketch: neither Mozart nor Schubert routinely sketched in anything resembling the obsessive, repetitive, brutally self-critical acts that constitute the compositional process for Beethoven. For Mozart and Schubert, these fragments put us before the moment at which an imagined music is concretized in written form. Where writing stops, we are witness to a breach in thought. This broken music, echoing into a timeless void, challenges us to imagine the moment where idea and sound collapse—to read the moment for a significance that can never be recovered.

“He is the father, we are the children,” Mozart was said to have exclaimed of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. “What he did would be considered old-fashioned now; but the way he did it was unsurpassable.”40 The fanciful invention of the ever-inventive Rochlitz, the exclamation yet lives on, so conveniently does it capture what much other evidence advocates as Bach’s patrimonial place at the end of the eighteenth century.

“I have only a few samples of Emanuel Bach’s compositions for the clavier,” Beethoven wrote to Breitkopf & Härtel on 26 July 1809; “and yet some of them should certainly be in the possession of every true artist, not only for the sake of real enjoyment but also for the purpose of study.”41 The works in question were no doubt the six sets of keyboard works “für Kenner und Liebhaber” (1779–1787) actually printed by J. G. I. Breitkopf for Emanuel Bach, who retained the rights of publication. What was it that Beethoven thought he could learn from this music? And is there any evidence that Bach’s music touched Beethoven at this critical juncture in his own work? In asking such questions, I do not mean to set loose a hunt for simple answers, of the kind having to do with influence, with models and borrowings, with veiled intimations of homage.

Beethoven in 1810 is a composer casting about for a new voice. The notorious Akademie of 22 December 1808, a marathon retrospective of the grand genres of what has come to be known as Beethoven’s heroic phase, gave palpable evidence of the exhaustion of a style.42 What was exhausted was the vigorous, even belligerent engagement with those genres which collectively formulated a language of classical discourse. The crisis, in its essence, can be reduced to a coming to grips with the figure of Mozart, captured no more vividly than in the driven, manic cadenzas written for Mozart’s Concerto in D minor in 1809 (a topic explored in chapter 9).

The Piano Sonata in E minor, Opus 90, composed in 1814, evokes an aesthetic strain that Beethoven might have perceived in certain of the works in these valedictory collections of Bach’s keyboard music. “Mit Lebhaftigkeit und durchaus mit Empfindung und Ausdruck”: the inscription at the front of the first movement is the first of a new sort in Beethoven’s music, escorting the player toward a sensibility of feeling and expression redolent of the Empfindsamkeit immanent in the music of Emanuel Bach. Phrasing it in the vernacular—the earliest work of which this is true—gains for Beethoven an immediacy of address which in itself suggests something about the diction of the music.

The opening bars of this sonata emulate no Mozartean prototype. The music gropes for utterance: direct, halting, every note made articulate, without artifice, stripped of the conventional figures of transition. In the midst of these deliberations, the beginnings of a new theme—of something sung—at m. 9 sound sublimely nonchalant. But beginnings they remain, for the theme dissolves almost as it is formed. This new quality in Beethoven’s music was not lost on the reviewer for the Leipzig Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, for whom the first movement “approaches rather the free fantasy.”43 What I will explore in chapter 10 is something less obvious. Among those works of Emanuel Bach that Beethoven sought out for purposes of study are several whose traces are evident in the two movements of Opus 90, and in other of Beethoven’s later keyboard works as well. In some sense, it is the Geist of Emanuel Bach that hovers in these works, impalpable, and unreceptive to the kinds of documentation that bring reassurance to the historical enterprise.

Emanuel Bach was himself the child, genetically and artistically, of a father whose sovereign authority was recognized among a small circle of musicians in the decades after his death, and by everyone else only gradually, following on the publication of Forkel’s biography in 1802.44 The profundity of this relationship of son to father, and how its repercussions might be heard in the formulating of Emanuel Bach’s idiosyncratic music, is the topic of the chapter that follows.