There comes a moment, we would like to believe, when Beethoven turns away from the struggle—for him, the defining struggle—to move beyond Mozart, beyond the dialectics of the Revolutionary years, toward something other. To specify such a moment as a turn, an inflection, in some other direction, seems to me helpful in setting a convincing context for Beethoven’s increasingly focused investigations of earlier (and still earlier) music during a relatively silent patch that begins around 1812. The repertory of great final works, beginning with the two monumental ones at the end of the decade—the “Hammerklavier” Sonata and the Missa solemnis—invites an historical construct of intentionality, of cause and effect: Beethoven investigates earlier music as a preparation for these final works. To construct a narrative of this kind is to enable the story that we want to tell. It is not a story that Beethoven set out consciously to enact. The inquiry into earlier, remote repertories is a complicated business no doubt inspired by inclinations from various sources, but among these the most compelling must have been the urgent need to get on with the business of composing.

I

As Barry Cooper has recently set before us, the 179 settings of “folksongs” in response to the generous terms of George Thomson’s continuing invitations, occupied Beethoven from roughly 1810 through 1819.1 We are coming to realize that these settings are of much greater significance, both as works in themselves and as a repertory with its own constraints, than has been acknowledged until quite recently—this, with the help of the exemplary new edition by Petra Weber-Bockholdt for the Bonn Gesamtausgabe.2 The range and variety within this abundant repertory is striking. Alongside occasional instances of the routine are settings of breathtaking originality, passages no less moving, nor less deeply felt than those that we prize in the canonical works: “nowhere else did [Beethoven] transcend the bounds of convention more comprehensively,” writes Cooper, and if he overstates the case, it is easy to understand why.3

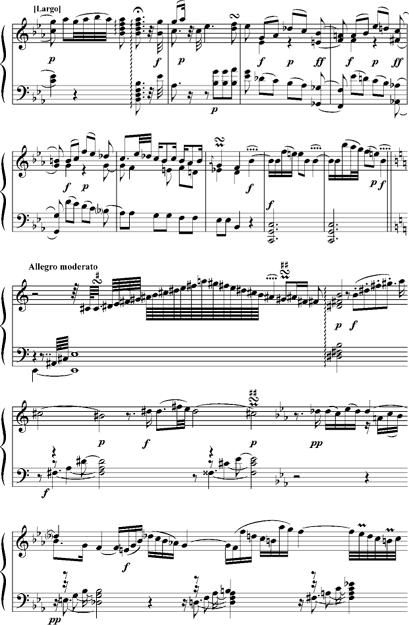

The settings for Thomson constitute a project of a special kind. Content not merely to provide the simple accompaniments for piano, violin and violoncello that Thomson commissioned of him, Beethoven probes the more exotic of these tunes for what they might stimulate of a newly inflected harmonic language. The opening bars of “Save me from the Grave and Wise” (WoO 154/8; shown in ex. 10.1) constitute an extreme case if not an isolated one. The lowered seventh degree, E♭, perched at the upper boundary of the tune, has significance both in its intervallic configuration with G and as a powerful modal determinant. In Beethoven’s setting, it is precisely this interval and these pitches that are embraced in the opening measure. The chord of the sixth, its E♭ made at once prominent and ambivalent in its motion to the following triad, cannot really be explained in the conventional grammar of a classical syntax. “Nb: Voila comme on ne doit pas avoir peur pour l’espression les sons le plus etrangers dans melodie, puisque on trouvera surement un harmonie naturell pour cela,” Beethoven wrote, at the bottom of the autograph of the song, acknowledging his sense of the exotic in these “foreign sounds” in the tune and the adventure in finding their expression in some “natural harmony.”4 The point is amplified in an entry in the Tagebuch, which Beethoven kept between 1812 and 1818: “The Scottish songs show how spontaneously even the most irregular melody can be treated by virtue of the harmony.”5

EXAMPLE 10.1 Beethoven, Save me from the Grave and Wise, from 12 Irische Lieder, WoO 154/8.

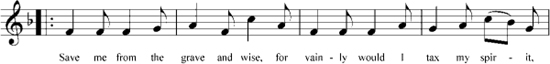

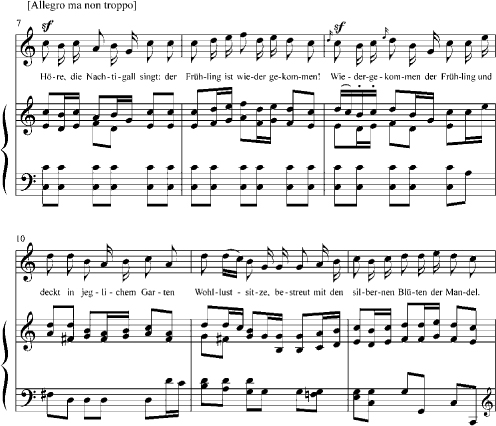

The engagement with Thomson’s repertory gave Beethoven the illusion of a probe into the exotic reaches of a timeless past, even if Thomson’s tunes were often merely contemporary approximations of an “authentic” folk music.6 During these same years, his engagement with a poetics of Greek antiquity similarly sought contact with a remote aesthetic. The Tagebuch contains an entry copied from Johann Heinrich Voss’s translation of the Iliad of Homer in which Beethoven marks off the hexameters with the diacritical accents of poetic scansion.7 He actually took the pains to set a Homeric verse to music, marked “Hexameter,” in the so-called Scheide sketchbook from 1815–1816.8 The scansion, with its obsessive dactyls, puts us in mind of those poems from Herder’s collection Blumen aus Morgenländischen Dichtern gesammelt that interested Beethoven at just about the same time. Two of the poems were actually set.9 One of them–Der Gesang der Nachtigall, its autograph dated “3 Juni 1813”—traffics in those complex hexameters that Beethoven was studying in Homer, even as it pursues the Volkston immanent in Herder’s botanical garden (see ex. 10.2). Herder’s trilling nightingale would reappear (now a swallow) a few years later, in the fifth song of the cycle An die ferne Geliebte (1816), another song in C major whose prosody is all dactyls and spondees, set in simpler tetrameters. Of the stripped-down harmonies and folklike tunes that characterize both the Herder setting and the Jeitteles cycle as a whole it might be said that Beethoven achieved the studied artlessness, the Volkston, that he seemed unable or unwilling to find in the bolder settings of those tunes that Thomson sent him. Paradoxically, the Thomson project inspired a more imaginative investigation into the generating of harmony itself from “foreign” melody, even as it seems to have awakened in Beethoven a new appeal to the essence of a Volkston in his original works.

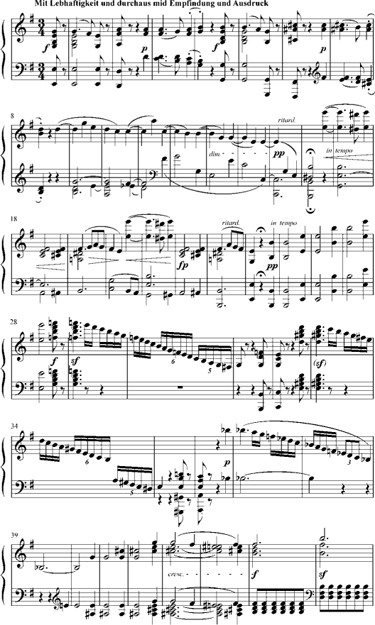

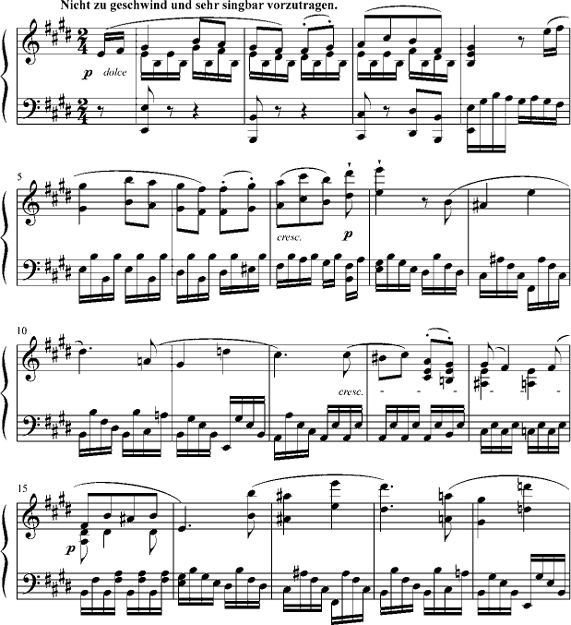

In the context of what might be thought of as a search for a new poetics, it may seem willful to call up the opening phrases of the Piano Sonata in E minor, Opus 90. And yet there is something about these phrases that resonates with those studies in the declamatory, that encourages us to hear the opening phrases as an exploration of a new, narrative mode, not so much songlike in a lyrical sense, but, rather, Lied-like in its diction, and balladlike: erzählend, sprechend—speechlike—“im Legendenton,” as Schumann would put it in the first movement of the Fantasy some twenty years later. We might then remind ourselves of the similarity between the inscriptions at the top of both movements of Opus 90—“Mit Lebhaftigkeit und durchaus mit Empfindung und Ausdruck” (with liveliness and throughout with feeling and expression) above the first movement, and “Nicht zu geschwind, und sehr singbar vorzutragen” (not too fast, and to be played molto cantabile) above the second—and the inscription, to take but one example, above the song Resignation, from 1817: “Mit inniger Empfindung, doch entschlossen, wohl akzentuirt u. sprechend vorgetragen” (to be performed with intimate feeling, yet decisively, well accented and speechlike). In a poetics of inniger Empfindung and Ausdruck, the porous membrane between song and speech is indispensable. Beethoven’s piano, the instrument that seems often a surrogate extension of his being, must simulate a music that captures the essence of both song and speech even as it can neither sing nor speak in any actual sense.

EXAMPLE 10.2 Beethoven, Der Gesang der Nachtigall, WoO 141, mm. 7–12.

In the bardic opening measures of Opus 90 (shown in appendix 10A) the diction, the accents of the ballad-maker unfold in intentionally repetitive, prosaic iterations. But the prose serves as a backdrop for the ravishingly lyrical phrase that blossoms from the cadence. It is precisely here, in the interstices between these two musics, where speech becomes song, that the singular poetics of Opus 90 resides: the consequences of this concision, its directness of expression, are everywhere manifest in the music that would follow in later years.

There seems to me yet another path of inquiry into this music. In January 1812, Beethoven wrote to Breitkopf & Härtel, intensifying his request for the scores of Mozart’s Requiem, Clemenza di Tito, Così, Figaro, and Don Giovanni. “[T]he little [singing] society is beginning again at my home,” he writes, and slyly adds: “Surely you could even make me a gift of the things by C. P. Emanuel Bach, for they must be rotting with you.”10 This follows an earlier request, dated 15 October 1810: “In addition, I should like to have all the works of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, all of which have of course been published by you.”11 Earlier still, in a letter to Breitkopf of 26 July 1809, the focus on Bach is put sharply:

I have only a few things from Emanuel Bach’s keyboard works, and yet some of them should certainly be in the possession of every true artist, not only for the sake of real enjoyment but also for the purpose of study. And my greatest satisfaction is to play at the homes of some true friends of music works which I have never or only seldom seen.12

The works in question were no doubt the six Sammlungen für Kenner und Liebhaber, published by the author under the auspices of Johann Gottlob Im-manuel Breitkopf between 1779 and 1787. Did Breitkopf & Härtel ever comply with Beethoven’s request? The inventory of Beethoven’s estate, as compiled in an auction catalogue some five months after his death (the Nachlassverzeichnis, as it is commonly known), lists each of the Mozart works mentioned in the letter 1812, but there is no sign of any music by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach.13 Still, it is hard to imagine that Breitkopf would not have sent the Bach volumes: one must assume that there was an ample Restauflage sitting on its shelves, for Bach had each volume printed in a run of 1,050 copies.14 We know with some precision how many were sold ahead of time, for the subscription numbers were published at the front of each volume—and the few stragglers are often identified in Bach’s correspondence with Breitkopf. The subscriptions in fact dropped off quite dramatically after the 519 subscriptions to volume 1: for volume 6, there were 290 subscribers. But the numbers in Vienna were fairly constant. Gottfried van Swieten, to whom volume 3 was dedicated, purchased twelve copies of each volume. Artaria purchased twelve copies of the first five volumes, and six of the final one. My point is simply that Breitkopf (as Beethoven shrewdly surmised) will have had copies to spare, even as late as 1812—and that van Swieten, before his death in 1803, might earlier have made copies available to Beethoven.

A sonata in E minor composed in 1785, and published in the final volume—quite possibly the last purely original sonata that Bach composed15—has always seemed to me a powerfully suggestive one in the contextual world around Beethoven’s Opus 90. In its first movement, terse and dichterisch, each of its phrases responds to its antecedent in an overwrought language of Empfindsamkeit. (The entire movement is shown in appendix 10B.) The opening phrase seems about speech, even as it speaks. The interruption at m. 3, impatient with these measured tones, is abrupt, violent, contrary. In its wake, the measured calm of a new phrase (mm. 5–8), a closed four bars in C major, has an otherworldly quality to it, simulating a new beginning in a remote key, as though oblivious of the outburst that precedes it. The phrase never returns—is not recapitulated—and so the memory of it is yet more poignant than the thing itself. But for all its apparent sense of isolation, a deeper continuity with its environment sounds just beneath the surface. The broken triad at the downbeat of m. 9, not quite the echo of C major that it seems, subtly inflects the harmony. The doubling of E has an acoustical consequence, asserting E as a root in place of C, which sounds now as a dissonant appoggiatura above an implied B. In the devious, chromatic playing out of the exposition, C vanishes altogether, usurped by the close in B minor.

The music that follows the double bar is yet more extreme in its sequence of nonsequiturs: four phrases, each seeming to dwell in its own figural world, with only the most fragile tonal thread tracing the opening in G minor to the half cadence on the dominant at m. 23. Such music seems intentionally distracted, impatient with the idea of a conventional continuity. With exacting parsimony, Bach picks through his notes as though each were the subject of an intense scrutiny. In bar 15, the isolated B♭, pianissimo, is heavily invested. Its position in the tenor (the only note in the left hand) establishes a second voice against the theme, contradicting the B♮ that is the new tonic in which the exposition closes. Its timing at the last possible moment in the bar enhances its role in the unfolding of this little drama. The B♮, forte, at the outset of the third phrase (m. 19), in turn contradicts the sense of G minor/D minor and its implications of an axis on the flat side of its tonal world, and sets in motion a strange, pointedly archaic two-part invention that gives on to a three-bar phrase of another kind, where the trim clarity of an interval sequence—again, a sharp motivic profile with neither precedent nor consequence—obscures a more complex inner voicing toward the half cadence. In the recapitulation, only the first two bars (excepting a difference in the very first attack) literally repeat music from the exposition. The return of the outburst at mm. 3–4 has an expansiveness to it that passes through C major without the faintest allusion to the phrase at m. 5.

If there is no hard evidence that Beethoven knew this sonata, the opening music of Opus 90, in its open appeal to Empfindung and Ausdruck, yet resonates suggestively with the sensibilities, the aesthetic world, of Bach’s extreme sonata. The elusive trappings of influence in any of its conventional senses are not in evidence, nor is the scent of homage. Rather, one hears in Beethoven’s music a subtle trace of the earlier work, of its terse narrative discourse, its disdain for the conventions of form—a disdain not for the overarching principle of sonata form, but for the symptoms that would make of it something conventional. It is this dialectical playing out of a music of sensibility against the formal archetype of sonata that these works share, even if the playing is engaged in very different terms. Beethoven’s encounter with Bach is not of the antiquarian sort—a seeking out of the past for the sake of its distance from the present—but rather a meeting of temperaments.

To enumerate all the ways in which Opus 90 differs from Bach’s sonata is to differentiate between two styles, two grand and idiosyncratic figures, two epochs. And yet to hear the opening movements of these two sonatas alongside one another is to be struck by evident similarities at the surface of the music and by a deeper affinity, a shared Geist, from which they emanate. The brusque juxtaposition of conflicting ideas, the flaring of unexpected, unsustained lyricism, the isolation of gesture, even of tone, sounding the extremes of register, and a coherence that implicates a deeper subjectivity behind the notes: these idiosyncrasies that so mark Bach’s music are familiar ones to the students of Beethoven’s later style.16 The “subthematicism” that Carl Dahlhaus would identify as an aspect of Beethoven’s late style seems evident as well in Bach’s sonata (a work composed in his seventy-first year). For Dahlhaus, it is in the music of this “transitional” period—“the profound caesura that can be sensed in the years around 1816,” as Dahlhaus so aptly puts it, even as he problematizes the very notion of a “transitional” phase—that the “lyrical” finds a place outside that “enclave in the classical sonata” to which it had earlier been confined.17 “A foundational paradox of the late style,” this freeing up of the lyrical impulse is coordinate with a “retreat into latency” of actual formal, thematic process: “as the substance underlying the network of relationships grows less distinct, so it retreats from direct perceptibility into the shadows of the ‘darkly felt’–as they said in the eighteenth century.”18 “Dunkel gefühlt”: these are precisely the words of Emanuel Bach, in his appreciation of the introductory chapter of Forkel’s Allgemeine Geschichte.19 Bach meant by them to insinuate the sense that music could convey of and within the grammar and syntax of true language, a sense that is contingent upon the inference of relationships beneath the surface of the music. That Dahlhaus (who does not reveal his sources) might subliminally have associated an idea of the “subthematic” with Bach’s efforts to convey the linguistic properties of music is altogether speculative. But it is precisely this kind of association that helps us to enter into the relationship between these two sonatas in E minor. However we think to identify the thematic “process” of Bach’s sonata, we are driven to the latency of certain configurations that seem to hover above or beneath the surface of the work, not quite identifiable as intervalic properties, nor predicated on a systematic teleology of formal event. Dahlhaus speaks of a “‘subthematic’ realm in which threads are tied criss-cross at random, instead of the musical logic manifesting itself as the commanding, goal-directed course of events.”20 If this random tying of threads is only faintly perceptible in Bach’s sonata, in Opus 90 the threading is yet more labyrinthian in that certain locutions in Bach’s sonata seem to have woven themselves into Beethoven’s thought, most obviously in how the opening figures in each sonata suggest inversions of one another. Even the fleeting allusion to C major at mm. 29–32 in Opus 90 seems tied in with that spectral C major early in Bach’s sonata. More to the point, in each of these works one senses a coming to terms with the contradiction of the irrational moment—lyrical, eruptive, improvisatory—and the deeper abstraction of musical process.

III

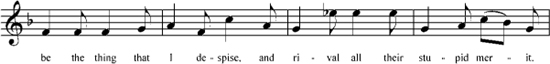

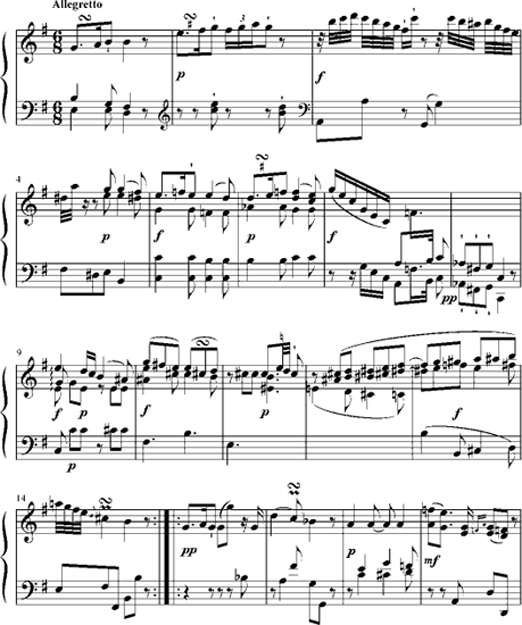

The second movement of Opus 90 is, famously, a rondo. It is not the first rondo that Beethoven composed. Rondo, so named in the score, is inscribed above the finales of ten piano sonatas, from Opus 2 no. 2 through Opus 53, the finales of eleven chamber works, the finales of all five piano concertos (and the Rondo, WoO 6, that was the original finale of Opus 19), the violin concerto and the triple concerto, and in the titles of the two rondos, Opus 51. This is not to speak of a number of rondos from the earliest years, about which more in a moment. The finale of Opus 90 is different. The trappings of rondo are everywhere in the music, but the name itself is withheld. “Nicht zu geschwind, und sehr singbar vorzutragen,” Beethoven wrote in the autograph: “Not too fast, and to be played molto cantabile.” The sense of the music as a rondo of a certain kind is manifest in the elocution of the theme itself (shown in appendix 10C). Nottebohm, writing of a well-known sketch for the theme, was struck by one deviation in particular: a single note, incomprehensibly missing in the sketch (see ex. 10.3).

Whoever considers the beautiful melody that emerges as though perfectly formed, and which serves as the basis for the last movement of the Piano Sonata in E minor would be hard pressed to imagine that, as this sketch indicates, the third eighth in the second measure was not originally present. Through the note added to replace the rest, completing the phrase and connecting its subphrases, the melody acquires a feature that significantly contributes to its beauty.21

EXAMPLE 10.3 Beethoven, Opus 90, second movement: sketch, from Nottebohm, Zweite Beethoveniana, p. 366.

What is it about this missing note that inspires Nottebohm to such uncharacteristic wonder? If it has in part to do with the notion of Sangbarkeit that is at the core of this music, there is perhaps a purely grammatical reason as well. The G# is an unaccented passing tone; to begin a new phrase here, within a tune meant to evoke simple singing, is inimical to the inner simplicity that the tune means to embody. More than that, the phrase that is impressed in our minds suggests in its diction the prosody of verse. Its sequence of dactyls constitutes a full tetrameter. The missing note in the sketch interrupts the sequence. It is not that the one version is appreciably better than the other, only that the difference is of some consequence in how, in its poetic dimension, the phrase is understood.

If we were casting about for some antecedent to Beethoven’s “ultimo pezzo” (as the sketch is inscribed), seeking not models but rather some earlier work to which Beethoven’s music seems drawn in an affinity of tone and idea, one work springs to mind, and it is by Emanuel Bach: this is the Rondo in E major (composed in 1779) that opens the third volume für Kenner und Liebhaber.22 (The opening is shown as appendix 10D.) In these late collections, the rondo—there are thirteen of them, interspersed in volumes 2–6—achieves a stature and a range of idea and expression incommensurate with the low regard, bordering on contempt, with which the genre was commonly held in northern Germany in the 1770s.

It was the irony of this contradiction that provoked Johann Nikolaus Forkel to sketch a “little theory” of the genre as a preamble to his formidable analysis of the rondo finale of the Piano Trio in G (H 523).23 For Forkel, the theorizing about genre and the analysis of Bach’s rondo are inseparable, for if the theorizing seems merely a ploy to establish the criteria by which such a work might be assessed, it is Bach’s music that informs the theory at every stage, and that finally distinguishes the work from all those lesser examples by which the genre had acquired its bad name. The “first rule” for Forkel is that the principal idea (“Hauptgedanke”) of the rondo, which is naturally subject to the obligatory repetitions demanded of the form, must possess an inner worth, and because it will be repeated often, “must contain within itself all the properties that would make it worthy of such repetition.”24 Of the first phrase of Bach’s rondo, Forkel writes “the theme is so beautiful that we can well imagine that one could hear it without ever tiring of it. It is exceptionally pleasing, simple, clear and comprehensible, without seeming impoverished, and at every repetition one hears it with new satisfaction.”25 Forkel’s investment in the quality of the phrase, in its “inner worth,” constitutes something of a departure from the normal discourse of music criticism in the eighteenth century, for the talk is not about syntax or form, rhetoric or affect, but about an intangible quality inherent in the idea itself, and it is this quality that presumably distinguishes Bach’s rondo from those of the “Modecomponisten” elsewhere disparaged in Forkel’s review.

These matters were revived a few years later by Carl Friedrich Cramer in his Magazin der Musik for 1783. Writing of the rondos in the fourth of the collections für Kenner und Liebhaber, Cramer argues against the notion that Bach can be accused of “condescending” to compose in these “lighter genres” when his music demonstrates by example how even these genres can be enriched and the mind of the Kenner satisfied.26 “No one who brings feeling and insight to their performance, and who at the same time will consult Forkel’s analysis of one of the earlier ones, and the very true theory of rondo that he abstracts from it, can doubt that this is the case with Bach’s rondos,” he writes, and then recounts those qualities that Forkel found immanent in Bach’s rondo:

the indispensable and striking beauty of its theme and its capacity for a breaking up into its components [Zergliederung] and for alteration [Veränderung], the way in which the secondary themes (couplets) would arise from it—how they would paraphrase, confirm, “prove” [their relationship to the them]—how the secondary ideas, variations and transpositions to remote keys will be appropriately applied, and interior modulations and the return to the tonic will be managed with due care.27

But when Cramer gets to the actual music, he turns away from the “detail of a sterile ledger of harmonic fine points, of modulations and their paths of return, and the like”—turns away from Forkel’s analysis—to an account that “in some measure comes to terms with my Empfindungen,” as he puts it, “so that I would think of a character that could correspond to a distinguished piece.” For Cramer, the theme of the Rondo in A evokes for him “the obstinacy of the most lovely maiden who will quite get her way through her mood and a pleasing persistence.” The Rondo in B♭—for Cramer, the most impressive of the entire run—conjures for him “the most youthful, most naive petulance [Muthwill] of a lightly dancing grace! Thalia, it should be inscribed, uniting with this word everything that the Greek thought when he conjured up now the playmate of Venus, the Graces, now that Muse who rules over the comic.”28

Impatient with the cold analytical strategies of Forkel, Cramer here articulates the beginnings of that eternal divide between the rigorous, hard-boned analysis of music as grammar and syntax and a criticism in pursuit of some meaning beyond the notes. Forkel had of course written brilliantly on the place of Empfindung in the music of Emanuel Bach.29 Feeling, for Forkel, is immanent in the notes. The character of the piece, the embodiment of Empfindungen, is itself a subject of analytical scrutiny. For Cramer, the locus of Empfindung is shifted. The critic, as sensory organ, registers feeling; it is then the responsibility of criticism to come to terms with those feelings: “von meinen Empfindungen Rechenschaft geben können,” Cramer proposes [emphasis added].30 What he writes is an imaginative expression of those Empfindungen, its justification the honesty with which he claims to feel.

These passages from Forkel and Cramer convey a sense of witness to something new and unique in Bach’s work: for one, the appropriation of genre and its renovation; for another, the contesting of the “popular” in opposition to the learned—the contesting even that there is an opposition here at all; and finally, the sense of a new thematicism—the idea of theme as constituted in expansive, commodious phrases and as subject of further inquiry in the course of the piece. This “inner worth” that Forkel detects is then aligned with the beautiful. Beauty is invoked here not in the general sense of art as “beautiful,” but as an identifiable characteristic that would distinguish this theme from its predecessors.

“When did Haydn begin to write ‘beautiful’ melodies?” asks James Webster, finding an answer finally in the first movement of Haydn’s Symphony No. 77 in B♭ Major, tellingly composed in 1782, “the first symphony whose second theme seems clearly to adumbrate” a type exemplified in the second theme in the first movement of Mozart’s Symphony in G minor (K 550).31 Haydn’s vigorous engagement with the performance and composition of opera at Esterháza quite naturally encourages “the new proximity of symphony and opera” that Webster finds “characteristic of Haydn’s music … after 1774.”32 Bach’s engagement with opera—with the life of the theater—was, on the contrary, distant and passive, even antagonistic, and a matter of much speculation. But the point here is that the kinds of themes that we now find in these late rondos share certain characteristics with the cantabile themes of Haydn and Mozart that begin to emerge around 1780. Webster’s question is as pertinent for Bach as it is for Haydn, and the date for which one might claim an answer is pretty much the same.

To suggest that Beethoven, in the finale of Opus 90, means to emulate Bach, to imagine that he would have needed a model, in the mechanical, technical sense, is decidedly not to the point. That these two rondos have something to do with one another, however, is a notion that I wish to pursue as another entry into the vexed topic of Beethoven and his pasts. In their formal mappings, the two are indeed very different. Bach’s rondo characteristically sets the theme in remote keys: in F major, in F# major (coincident with a change of meter to 12/8), in C major. In none of his rondos is the theme locked into the tonic, as is invariably the case with Beethoven, who in this matter is even more conservative than Mozart.33 And yet for all its classical poise, Beethoven’s theme is pointedly un-Mozartean. The world that it evokes is Emanuel Bach’s. Even in its elocution, that Sangbarkeit that Beethoven asks of the player, the music reaches back to an earlier generation, retrieving a way of playing that Bach himself described as “das Tragen der Töne,” by which he meant a sustaining of the tone from one note to the next, but with a special inflection (Bebung-like) within the tone itself: a playing in the keys, so to say.34 Writing in 1753, describing an affect possible only on the clavichord, Bach cannot have had even remotely in mind its eventual applicability to the performance of those rondos of 1779. Still, there is something compelling in the notion that the enactment of this “Tragen der Töne” would, in some compensatory mode of articulation, find its way into these new works “fürs Forte-Piano” (as its title page specifies), even in the elegant fusion of the declamatory and the singend that seems central and immanent in the theme of the Rondo in E—an attribute of its inner worth, so to say. It is this quality that Beethoven seeks to capture in the rondo of Opus 90.

How, then, to understand this enigmatic relationship between works? Harold Bloom, in a well-known passage from The Anxiety of Influence, here imagines the return of the dead poet in the work of his successor:

The later poet, in his own final phase, already burdened by an imaginative solitude that is almost a solipsism, holds his own poem so open again to the precursor’s work that at first we might believe the wheel has come full circle, and that we are back in the later poet’s flooded apprenticeship, before his strength began to assert itself… . But the poem is now held open to the precursor, where once it was open, and the uncanny effect is that the new poem’s achievement makes it seem to us, not as though the precursor were writing it, but as though the later poet himself had written the precursor’s characteristic work.35

Bloom is helping us to envision the convoluted process of mind in which the later poet in his later years—Beethoven, now feeling the isolation, the “imaginative solitude,” at the onset of later middle age—is able to embrace and absorb the work of his precursor (Bach, in this instance) so completely that, for a moment, we are made to feel that Beethoven had gotten himself under the skin of Bach’s Rondo. On its face, this is a strange notion: a fantasy in the mind of the beholder. But Bloom’s point, in its application to the instance before us, is that there is a deeper struggle here than might be evident from the surface of the music. At the outset of his study, Bloom writes: “Poetic history … is held to be indistinguishable from poetic influence, since strong poets make that history by misreading one another, so as to clear imaginative space for themselves.”36 If this “clearing of imaginative space” resonates profoundly in the great creative cycles that characterize Beethoven’s lifelong project, the image comes sharply into focus at this critical moment in 1814, where the worn orthodoxies of the past fifteen years are now swept away, and we find ourselves in the presence of Beethoven’s “flooded apprenticeship.”

Where are the traces of this precursor, and how are they manifest? For Bloom, famously unsympathetic to such questions, the commonplace trappings of influence are the business of “source-hunters and biographers.”37 Rather, it is only in the anxieties with which the late poet confronts his ancestors that meaning can be wrung out of the urge to create. “Initial love for the precursor’s poetry is transformed rapidly enough into revisionary strife, without which individuation is not possible.”38 If, in these late works by Bach, there is an immediacy of expression that speaks to Beethoven, a diction that intrigues him, he must now come to terms with these works in a voice that seeks its own origins. By these lights, the music of Opus 90 would be heard not as an affectionate evocation of Bach’s works, but as something considerably more obscure: a revision, a correction, a swerve, as though composition were itself an act of re-composition.

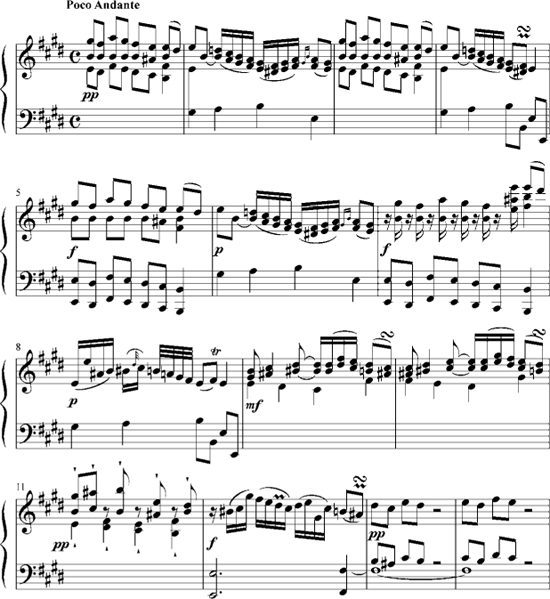

But it is only in the traces of this act that encounters of the Bloomian kind can be reconstructed in the first place. Such traces are nowhere more evident than in the closing measures of Opus 90 (shown in appendix 10E). The grand rhetorical endings, victorious or tragic, of the past decade are deflated in a single dismissive gesture. This is how Emanuel Bach occasionally closes, memorably so in the opening sonata (H 281) from the fifth collection “für Kenner und Liebhaber.” The first movement, in E minor, does not end, but moves off to C major, where eight measures of Adagio, followed by an unmeasured cadenza, ruminate on some motives that will cohere in the following Andantino, a wispy, fragile rondo in E major, much scaled down from those independent rondos by which the genre is defined. Its final measures are to the point here (see appendix 10F).39 Breaking off as though in mid sentence, the work ends neither with a peremptory, moralizing statement nor in the grand structural arches that signify closure in a classical style. It simply vanishes. The final bars of the much grander Rondo in E, if not quite so radical, have the same effect (see appendix 10G). This way of ending belongs to the wit of eighteenth-century narrative. In such modest, self-effacing leave-takings, the work seems to view itself with ironic detachment.

If Bach’s voice and manner are evident in the final bars of Opus 90, it will not do to claim simply that Beethoven has appropriated Bach’s keen sense of the ironic, for to make such a claim would mean to argue for its artificiality. The irony of Opus 90, no less genuine than Bach’s, comes of a complex renunciation of Beethoven’s own earlier music. It seems hardly possible to imagine with any clarity the convoluted figure that Emanuel Bach must have signified for Beethoven in 1814, seeking to recapture his apprenticeship with Christian Gottlob Neefe in Bonn, where Emanuel Bach was no remote ancestor, but an aging contemporary whose latest music must have seemed at once inaccessible, profound and eccentric—seductive, yet without immediate appeal to a teenager whose ears were tuned to Mannheim, to Paris, and to the Vienna of Haydn and Mozart. In his earliest works for keyboard, Beethoven’s leanings in those directions—away from Hamburg, Berlin, and Leipzig—are transparent. The two rondos, WoO 48 and 49, published in Bossler’s Blumenlese für Clavierliebhaber for 1783 and 1784 bear not the slightest trace of the rondos in Bach’s collections, nor does the rondo finale of the Piano Sonata in E♭, WoO 47. In these, as in the rondo finales of the Piano Quartets, WoO 36, nos. 2 and 3, from 1785, the themes are oblivious of that “inner worth” that Forkel prized in the themes of Bach’s rondos, and refuse the bold modulatory strategies, the improvisatory flights that set these works apart. Beethoven was finding his models elsewhere.

That the Piano Quartet in E♭ Major/Minor (WoO 36, no. 1) was modeled on Mozart’s Sonata for Piano and Violin, K 379 has been known ever since Hermann Deiters called attention to it in his revision of the first volume of Thayer’s biography.40 The matter was explored more deeply by Ludwig Schiedermair, and, with considerable insight, Arnold Schmitz.41 The finale of the Trio in G Major for Keyboard, Flute and Bassoon, WoO 37 (1786), an “andante con variazioni,” again draws its inspiration from the finale of Mozart’s K 379, while the expansive first movement indulges in the familiar mannerisms of Mozart at the keyboard. Emanuel Bach figures here not at all. Schmitz smartly observed that Beethoven’s notion of a contrasting thematic Ableitung—by which is meant a derivation of the contrasting element from within the theme itself—was developed early.42 Writing of the putative relationship between the first movements of Beethoven’s Sonata in F minor, Opus 2 no. 1, and Bach’s Sonata in F minor (the subject of Forkel’s Sendschreiben, discussed above in chapter 1), Schmitz concludes that “the concentrated unity in the fashioning of Beethoven’s phrase structure indicates the influence of Ph. E. Bach. But Beethoven’s technique of contrasting elements is based on other historical foundations.”43 This “concentrated unity” and “a certain tendency toward [thematic] derivation”(“eine gewiße Ableitungstendenz”) is something that Schmitz finds still earlier, in that Piano Quartet modeled on Mozart’s K 379. In this view, the eminence of Emanuel Bach makes itself felt in Beethoven’s earliest music neither in the articulated surface of the music, nor in the construction of its themes through a simultaneous process of contrast and derivation, nor in the conceiving of large-scale structure, but in something less palpable: in an attitude expressed in the concept of “concentrated unities.” The intensity of expression and the high aesthetic purpose of Bach’s music (to say nothing of its pedigree) would no doubt have exercised a powerful standard to which Beethoven would in turn have felt a sense of responsibility.

The problem with this view is that it presupposes a familiarity, an intimacy with Bach’s music that cannot be verified.44 In this connection, it is good to remind ourselves that Neefe spent the years from 1776 until his arrival in Bonn in 1779 traveling with the Seyler Theater Company, for whom he acted as music director (in place of Ferdinand Hiller) and composer, and that the engagement with theater continued during his tenure at Bonn. Emanuel Bach, a figure of exceptional stature to Neefe in his apprenticeship, must surely have faded into a more populous background in the 1780s. And yet there can be no question that Bach’s Versuch, in both its parts, will have served as a pedagogical foundation. This is clearly conveyed in a piece called “Gespräch zwischen einem Kantor und Organist” (Conversation between a Cantor and an Organist) in a collection of poems and miscellaneous pieces brought out by Neefe in 1785. In the “Conversation” (which is dated “1780”), the following lines are given to the Kantor:

[Philipp Emanuel] Bach’s Essay on the True Manner of Playing Keyboard Instruments, and his keyboard pieces, are still to be recommended to the advantage of those who aspire to excellence on this instrument, which an impudent rogue has recently and thoughtlessly held against this illustrious man. How then does it come about that the most humble of Bach’s students can read off the most difficult things at sight while a keyboard player in the latest style can barely play four measures of a Bach sonata without stumbling? Bach’s Allegros demand uncommon dexterity of the fingers on both hands. The fingers of the left hand must be as capable as the fingers of the right of performing the most varied motions, whereas the arpeggiated basses in the latest fashion require only one kind of motion. The Bach Adagios demand a precise knowledge of the modifications of which the clavichord is capable, if they are to be played from the depths of the soul. And to see through the diverse veilings of his ideas to the design of his works requires more than the usual common sense: it requires study. But one is rewarded for one’s labors. He who can play Bach properly can surely play most other composers as well. And he will enjoy a more sustained satisfaction through Bach’s work than through the works of many others… . I am ashamed for the souls of my countrymen that I must say that I have seen a great region of Germany where one knew no more of Bach than that he is named Karl Philipp Emanuel, that he lives in Hamburg, and that his works are said to be very difficult, and yet not in the current taste… .45

To imagine Neefe and Beethoven going at some of Emanuel Bach’s more recalcitrant works, penetrating those “diverse veilings of his ideas” (verschiedene Einkleidung seiner Gedanken) to get at some sense of the larger “plan,” is to depict an aspect of Beethoven’s formative education that would otherwise remain inscrutable. This little “Gespräch” is something of a polemic in defense of a man whose music Neefe perceived to be no longer in the public consciousness, whose “style” was seen as hopelessly outmoded. For Neefe, Bach’s music stood aloof from the pettiness of popular fashion. But there are deeper issues here, for the appeal of a Mozart was clearly the more powerful for Beethoven. The new irony in Opus 90 comes about as a coming to terms with that earlier repudiation of Bach. It is as though Beethoven wished, subconsciously or not, to retrieve the Geist of Emanuel Bach, to rewrite in this new work the story of his apprenticeship, and from the perspective of older age.

In 1814, this revisiting of Bonn in the 1780s will have invoked another aspect of Bach’s music, for the two works that suggest themselves as precursors stand not only for two distinct genres (Sonata and Rondo) but for two different keyboard instruments. “Fürs Forte-Piano,” as Bach’s title explicitly puts it, these late rondos exploit the timbre, the resonances of the new instrument.46 No less explicitly, the first movement of the late Sonata in E minor is music for, and indeed of, the clavichord. In a recent investigation of the matter, Tilman Skowroneck assembles the considerable evidence surrounding the instruments in play during Beethoven’s Bonn apprenticeship.47 That the clavichord figures prominently here will come as no surprise.

In the preface to his Zwölf Klavier-Sonaten of 1773, warmly dedicated to Emanuel Bach, Neefe comes directly to the instrument. “These sonatas are for the clavichord,” writes Neefe:

I therefore wished that they be played only on the clavichord, for most of them will have little effect when they are played on the harpsichord or the pianoforte because neither of these instruments is as capable as is the clavichord of producing the cantabile and the divers modifications of tone toward which I guided myself.48

Improvements in the fortepiano in the years between 1773 and the early 1780s and greater familiarity with its expressive potential will no doubt have induced Neefe to moderate his thoughts.49 And yet, his devotion, even in 1785, to the clavichord as an instrument without which the empfindsame Sprache of Emanuel Bach could not be conveyed comes clear in that telling line from the “Gespräch”: “The Bach Adagios demand a precise knowledge of the modifications of which the clavichord is capable, if they are to be played from the depths of the soul”50 For Neefe, the two instruments do not stand in some evolutionary succession in which the one supersedes the other. Neefe, I think we must believe, would have instilled in Beethoven the sense of the clavichord as an instrument at the foundation of an aesthetic that would figure prominently in Beethoven’s formative Bildung as a keyboard player.51

We have come to accept without question a teleology that has Beethoven composing for some keyboard instrument whose capacities for extremes of register and sonority had yet to be realized, suggesting that his music seems often intent upon the destruction of the existing prototypes. Even if there is some truth to be teased out of the popular allegory, it would be good to view the matter from the other end of the telescope—from the deeper perspective of a musical sensibility formed in the 1780s. The clavichord has a role to play in this story. How the instrument may be perceived to resonate in Beethoven’s final keyboard music is not a phenomenon that we can ever authenticate with the hard evidence that historians want. And yet there seems to me an intuitive truth to be apprehended here: that the clavichord constitutes a fiber in Beethoven’s musical sensibility. It is repressed, challenged, superseded—but it is there, just under the skin, acquired like native language, not consciously learned and never entirely displaced. When Beethoven writes the Bebung-like passage at the “Recitativo” in Opus 110—the high A♮, dissonant seventh above B, escorted through an expressive gamut: piano, una corda, crescendo, tutte le corde, diminuendo, ritardando, again una corda, all sempre tenuto and with the sustaining pedal—he does not mean to implicate Emanuel Bach in an act of willful historicizing. I should think, rather, that we are here witness to an elocution (call it linguistic) that had once been altogether normal and natural in Beethoven’s keyboard playing: an utterance that the much grander instrument of 1820 can only hope to suggest.52 It is as though Beethoven were here inventing a notation to capture how he must have performed (for himself and his students) that famous passage from the Fantasy in C minor that is the final number in the Probestücke published with Part I of Emanuel Bach’s Versuch. (The two passages are shown in appendix 10H and I.)

What is played out beneath the notes of Opus 90 is neither an act of simple homage nor a conscious revival of some historical moment, but something more complex. I return to Bloom’s Anxiety of Influence, to its talk of the “clearing of imaginative space” in the enabling of a first creative act. Without much stretching of Bloom’s conceit, one wants to conjure Beethoven finding his way through Thomson’s Scottish tunes, reading and parsing Homer in Voss’s poetic German, and seeking in Emanuel Bach’s late keyboard music a tone and an accent that would help to invigorate a fresh voice, in sympathy with some new impulse in his own thinking. Beethoven is here opening windows to a past, but a past in which a future is envisioned. If Emanuel Bach had in some measure become a “historical” figure for Beethoven, it would seem to me mistaken to argue that what we are observing here is in any sense an instance of historicist thought, a conscious enactment of the past for the sake of its distance from the present. The creative enterprise has always to do with a past, attuned to some earlier work with which the composer is locked in an embrace at once compassionate and antagonistic. It is the internalizing of this engagement that is inscribed in the music. Integral in its text, it will be felt, if not always recognized.

In a certain sense, then, Opus 90 reaches back to a moment somewhere in the early 1780s, a nexus at which the clavichord, in its final lavish exemplars, and the fortepiano, at this critical turn in its development, seem to touch one another for a fleeting, luminous instant, inspiring a strikingly new voice late in Bach’s own evolution in these expansive rondo themes in their elegant fusion of a new lyricism with that speech-like elocution deeply ingrained in Bach’s style. Opus 90 is of course about other things. It is of and about Beethoven in 1814, and all that this signifies about the complexity of style and genre at a critical juncture in Beethoven’s development. Emanuel Bach’s legacy lives on here as well, not in open parody or caricature, not in imitation of a style nor in the antiquarian spirit of historical revival, but in the deeper currents of an aesthetic that turned away from all virtuosity and sought in the keyboard an immediacy of the composer’s voice.

APPENDIX 10A Beethoven, Sonata in E minor, Opus 90, first movement, mm.1–46

APPENDIX 10B Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Sonata in E minor, H 287 (Wq 65/6), first movement

APPENDIX 10C Beethoven, Sonata in E minor, Opus 90, second movement, mm. 1–29

APPENDIX 10D Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Rondo in E major, H 265 (Wq 57/1), mm. 1–14

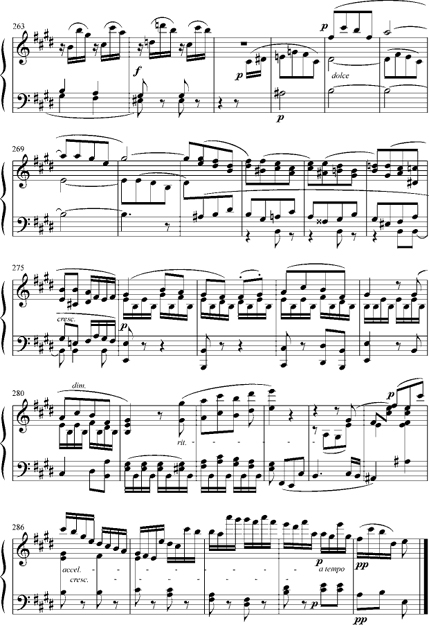

APPENDIX 10E Beethoven, Sonata in E minor, Opus 90, second movement, m. 263 to end

APPENDIX 10F Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Sonata in E minor/major, H 281 (Wq 59/1), third movement (Andantino), m. 39 to end

APPENDIX 10G Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Rondo in E major, H 265, mm. 88 to end

APPENDIX 10H Beethoven, Sonata in A♭ major, Opus 110, third movement.

APPENDIX 10I Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Fantasia, from 18 Probestücke (1753), H 75 (Wq 63/6)