Probestück: a test-piece, a demonstration of the performer’s skill, of the composer’s Kunst. What the word denotes extends beyond the notion of mere display to the cognitive process of learning—of a skill acquired in the performance of the piece, of idiomatic practices encoded in its notation, and the understanding of the work as an exemplar of composition, of style, of genre. Beyond these more conventional meanings is another, less commonly met, which reveals itself to the critical mind in the presence of a work that probes the frontiers of meaning: Probestück as a test of mind, of Geist.

Conceived as the final movement of the sixth sonata of the 18 Probestücke published with the first part of Emanuel Bach’s Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen (Berlin, 1753), the Fantasia in C minor promptly established itself as a work apart, as though embarrassed by its humble pedagogical origins. Bach himself singled it out in references to the genre, both in the second part of the Versuch (1762) and in a well known letter to Forkel.1 And in 1767, the Fantasia was subjected to a provocative experiment undertaken by the poet Heinrich Wilhelm von Gerstenberg, an experiment much discussed in the contemporary critical press and the focus of several recent studies.2

The brilliant glare of all this admiration seems to have obscured an aspect of the Fantasia that pleads for an understanding of it less as a composition in and of itself than as the third movement of a sonata—more than that, as the final station of a compendious work whose eighteen movements together constitute an essay in its own right: at once an exemplification of and a commentary on genre, and a journal in which these graded steps to keyboard mastery take on a life of their own, in the mode of fictive autobiography, as the empfindsame Leben—a life experienced more than reasoned—in which this Fantasia then stands for a state of mind.

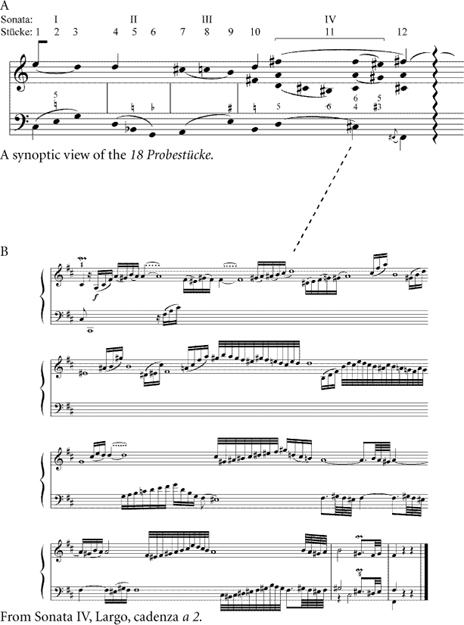

Consider how these eighteen pieces comprised in six sonatas plot out a tonal trajectory.3 It is well known that no single one of the six sonatas sustains its own tonic. Each course of three movements formulates a tonal configuration that wants to be construed syntactically. Trajectories within each sonata plot motion outward, in the manner of a modulation away from an initial tonic—in all but the second sonata, toward its dominant (and in the fifth sonata, to the dominant of its dominant). Without the return to an initial tonic, with conventional closure now in forfeit, the boundaries between sonatas are less clearly drawn. The first movement of the new sonata seems a response to the third movement of its antecedent. As a further consequence, the entire set sketches out a work syntactically coherent in a larger, more complex narrative. Less about some systematic exhaustion of the total chromatic, these eighteen Probestücke mean rather to exercise the novice in the incremental difficulties of remote keys, in their tactile and acoustical sense, but also empirically, in the stories that they have to tell. The graphing shown in ex. 5.1A attempts merely a synopsis of the cardinal tonal events in the set. (The contents of the collection are displayed in table 5.1.)

The playing off of sonatas against one another, dialectically (so to say), is apparent at the outset, where the tonal plot of the second sonata mirrors the first in interval inversion. It is of course not the inversion, for its own sake, that Bach wants us to hear, but, rather, the establishing of two vectors out from a primary C major, one along the sharp side, to the dominant, the other toward the minor subdominant, and what it portends of a “flat” side. The opposition—sharp side/flat side—intensifies as its axes diverge. The distances traversed are dramatized in a schism articulated between the fourth and fifth sonatas: the F# minor in which the fourth sonata closes is answered by a volcanic E♭ major, the music erupting, toccata like, from its opening octave in the bass. The vault between F# minor and E♭ major, for all its stunning effect, is a characteristic one: an ellipsis, Bach would likely have called it.

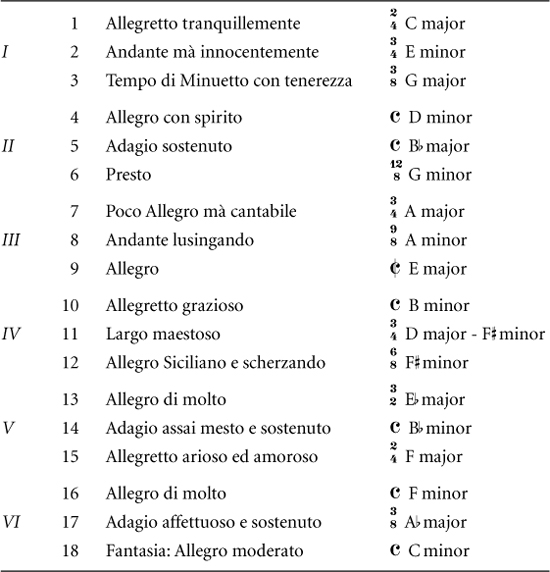

Those familiar with the second part of the Versuch (1762) may be reminded here of its final paragraph, in the chapter “Von der freyen Fantasie,” where a Gerippe (“skeleton”), in Bach’s vivid metaphor, displays in figured bass notation a fantasy in D major whose “realization” is shown on an engraved plate tipped into the book.4 (This is shown as fig. 5.1.)

Much has been made of this final and profound illustration, which Bach glosses with a paragraph of analysis that, in its laconic fashion, offers rare insight into Bach’s way of conceptualizing the process of composition. At the critical moment in the fantasy—the moment of greatest tonal remove—Bach invokes ellipsis: “The transition [Uebergang] from B with the seventh chord to the following B-flat with the [four-]two chord reveals an ellipsis, for strictly speaking, a six-four chord on B or a root-position triad on C ought to have been interpolated.”5 What I want to suggest is that this notion of a tonal Gerippe, static and “rational,” in tension with an “empfindsame” narrative of experience—a “realization” that moves off into remote regions of dissonance, exacerbating the moment of ellipsis—is a condition manifest as well in the Probestücke, taken as a single overarching work. In both, a moment of tonal extremity provokes a crisis in syntax, a breach in which the rule of grammar is taxed. Symptom of reason challenged, the ellipsis is meant to be felt, its narrating agent caught by surprise. And yet the moment must indeed respond to analysis—must be shown to have been plotted, a consequence of rational design, even if the effect borders on the irrational. Precisely how the ellipsis between F# minor and E♭ major might be explained—better, how dissonance of this magnitude is shown to resonate in the music that follows from it—is an obscure matter to which we shall return.

The setting of an environment in which such crisis can be construed seems clearly the point of the middle movement of the fourth sonata, an exaggerated lesson in the conventions of ouverture in French style: Largo maestoso, D major, much overdotting, much embellishment. At m. 23, in a rain of dotted thirty-second notes, fortissimo, the music splinters its frame. The B# at the end of the bar signals what is about to happen. D, as tonic, is unseated, the tone made dissonant against the B#. The music settles on C#, a dominant, isolated in three octaves with great flourish. What ensues is a cadenza in dialogue, deeply felt, trembling in Bebung—and in F# minor. (See ex. 5.1B.) Bach himself wrote about the intended effect of these two voices engaged in a performance that means to simulate the improvisatory: “The pauses called for at the whole notes occur so that one may imitate the unpremeditated cadenza-making of two or three persons, and at the same time imagine that the one is paying close attention whether the proposition of the other has ended or not.”6

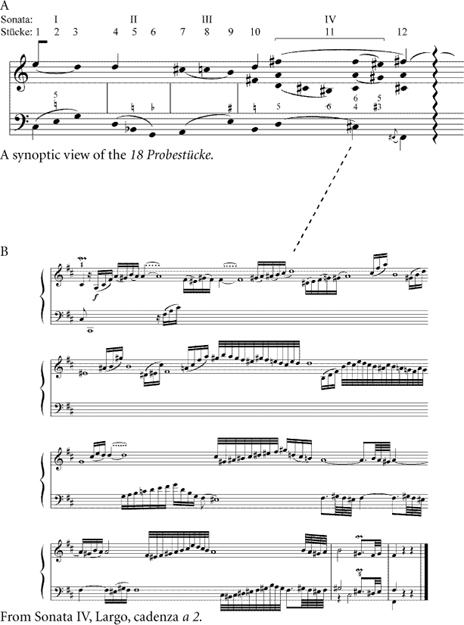

TABLE 5.1 Contents of 18 Probestücke.

FIGURE 5.1 C. P. E. Bach, Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen, II (Berlin, 1762), 341, and unpaginated plate.

In its groping to convey in words what the music does, Bach’s language affords one of those rare glimpses into the composer’s poetic imagination: what, precisely, these speechlike effusions are saying is of no consequence—are indeed unknowable. What does matter is the “paying close attention” that goes on between and during the cadenza-making, the one hand listening to the other. This, Bach tells us, is what needs to be performed. But what must strike us about this cadenza is its utter incongruity with the music that precedes it, and which it in effect dissolves. In its intimate dialogue, the cadenza seems a colloquy on the ouverture—a conversation about it—and by extension, a commentary on a genre, a style. This is not how overtures in the French manner are meant to end. (We return in chapter 9, in quite another context, to the provocations of this remarkable inflection.)

At a telling moment in his Paradoxe sur le comédien, Diderot writes: “The man of sensibility obeys natural impulses and expresses nothing but the cry from his heart; as soon as he begins to control or constrain this cry, he’s no longer himself, but an actor playing a part.”7 Lifted from its context, Diderot’s bold insight (to which we shall return in the next chapter) reflects aptly on an opposition that seems at play in this most contradictory of movements in Bach’s Probestücke. But the opposition is turned to other ends in Diderot’s argument, where the skilled actor is shown to be above sensibility, which he must learn to wear as a mask. To follow Diderot is to ask ourselves whether this schismatic music means, metonymically, to represent a breach in aesthetic: whether, that is, the composer, as playwright, has scripted a narrative for the player; or whether Bach’s music, finding its C#, must be taken as the cry itself, where the notes inscribe an escape from the constraints of the dogmata of another age. Such questions return us to Diderot’s Paradoxe, where the roles of poet and actor now and again fade into one another. In a sense, Bach’s Probestück worries this same problem, for the composer is not quite separable from the player, and the player, if he is playing a role, would, at this telling moment where the music unearths its resonant C#, know what it feels like to feel like Bach, to feel empathetically with him.

Ever engaged in role-playing, Bach’s keyboard music often voices the player in mask. And then there are those rare, signifying moments when the composer himself seems unmasked. That, I think, is what we hear at this deeply inflected C#. The mask is lifted. Player and composer are collapsed into one. The music shifts from the formalities of antique tragedy, distant and impersonal, to a theater of whispered intimacies. The catastrophic collapse into empfindsame dialogue as an escape from the overbearing rigor of the ouverture has implications that resonate far beyond the modest didactic objectives of the Probestücke. One senses here the passing away, the renunciation of ancien régime. The stiff mask of the aristocracy and its ceremonial dance are replaced with a music born of sensibility and irony and paradox. For Diderot’s actor, the cadenza-in-dialogue is but another mask, another state of mind to be disciplined. And yet this music sings of deeper authenticities, of the composer caught in the act. The quirky Siciliano that follows in F# minor emanates without pause from the lengthy cadential trills with which the cadenza closes. “Siciliano e scherzando,” Bach writes, but the music has its mordant accents (at mm. 41–44, not shown). Again the music seems more a commentary on genre than the thing itself. In its articulation of the form, the music hesitates pensively on octave C#s, first tonicized (mm. 35–36), then returned as dominant (mm. 39–40), and we are reminded of the signifying C# that moves from ouverture to cadenza-in-dialogue—reminded, too, of another one: the octave C#, pianissimo, before the reprise (in E major) of the third movement of Sonata III.

More obliquely, the cadenza on C# has an echo in its counterpart at the end of the Adagio affettuoso e sostenuto in the Sixth Sonata (see ex. 5.1C). Here, the cadenza splays out in three voices—and finally, to a confusion of voice—again suggestive of intimacies overheard. For the player, certainly, these two passages have much to do with one another. If the earlier cadenza is more effusive, more eccentric, more given to Bebung, to dissonance and difficult chromaticism, the cadenza in A♭ explores the affettuoso e sostenuto of its source music. Like the earlier cadenza, this one, too, raises expectations. Cadenzas at the close of slow middle movements have a rhetorical mission, for while cadenzas are always about the past—even as the cadenza on C# in the Fourth Sonata repudiates its past—they anticipate a future.

It is this sense of expectation that promotes the opening arpeggiation of the Fantasia, whose tones now seem to grow out of the ruminative, cadenza-as-conversation with which this penultimate music closes. Cadenzas, too, are about the improvisatory, and in these written-out instances, exemplify how one goes about the business of spontaneous composition, here constrained by the simple motion between a six-four and its resolution to the dominant. In the Fantasia, there are no such constraints; the very notion of formal convention is itself antagonistic to the idea of fantasy, where perhaps only the diction, the accents, the rhythms of its modulatory tactics might be generalized. The music gives the illusion of spontaneous thought, unrestrained by convention. Capricious wit, at the edge of chaos, plays against the deeper internal laws that govern how the music moves and how it will end. Not the least paradoxical aspect of the fantasy is its enactment, in its own tropelike conventions, of a rite of creation, even as, in the characteristic gestures of fantasy, it renounces the generic and the conventional.

Taking up the conversation of the cadenza, the deep C that sets the Fantasia in motion seems itself an unfolding from those closing imitations, even as this C fixes itself as a new fundamental (see ex. 5.1D). A♭ is now reduced to a dissonant sixth. Indeed, much of the first page of the Fantasia seems aggravated by A♭, at first as a dissonant and prominent upper neighbor (a ninth above the root of the dominant) and then as a root in its own right. As though embedded in these intervallic reverberations, the plangent tones of the Adagio continue to sound.

The ambivalence of the Fantasia as a third movement is much to its point. The music has a complicated, even contradictory role to play, for while it serves as a finale, it does not portray the gestures of closure by which finales are ordinarily defined. As Fantasia, it signifies a stage in the education of the musician, the moment at which performer and composer touch, where the act of performance comes closest to emulating the immediacy of creation. This opening arpeggiation, at once mimetic in its envisioning of the growth of Idea from some fundamental tone–as synecdoche, the figure containing within itself the essence of this larger thing that it means to signify—at the same time announces a telling event in a greater narrative of Bildung—another untranslatable word that I use here to suggest the maturation, the humanistic coming of age of the inner man through experience and reflection. Here is the moment toward which all this study and practice has been directed. The apprentice, it suggests, is now prepared to improvise, to create from the imagination. For whatever this Fantasia, as the final movement of these eighteen Probestücke, might signify of closure, it signifies a commencement as well: here are the beginnings of true invention, of original thought.

None of this pedagogical apparatus can have been of much interest to the poet Gerstenberg, a prominent figure in that robust literary circle in northern Germany that included such figures as Friedrich Nicolai, Moses Mendelssohn, Johann Heinrich Voss, Klopstock, Lessing, and Herder (to name only the principal players). A man of considerable musical ability, Gerstenberg took Bach’s Fantasia as a Probestück in quite another sense, fitting out the music with a rephrasing (more paraphrase than translation) of Hamlet’s soliloquy “To be or not to be”—inspired, one might think, by the translation of this much celebrated text in Moses Mendelssohn’s “Observations on the Sublime and the Naive in the Fine Sciences” (1758), then revised, with an entirely different translation, in the Philosophische Schriften (1761).8 Not the least curious aspect of Gerstenberg’s experiment was his determination to set Bach’s music to yet another text: this time, the final words of Socrates, a fantasy-like invention by Gerstenberg, now perhaps inspired by Mendelssohn’s Phaedon (published by Nicolai in 1767), which begins as a translation of the Socratic dialogue, but in the end allows his Socrates to speak in the accents of a philosopher of the eighteenth century: “meinem Sokrates fast wie einen Weltweisen aus dem achtzehnten Jahrhunderte sprechen lassen,” as Mendelssohn puts it in the preface.9

Johann Gottfried Herder, warming to his own translation of Hamlet’s soliloquy—a version of it was published in 1774—cited Mendelssohn’s, which he understood as “more an idealized imitation, as his purposes demanded, than a copy of the melancholy, scornful, bitter tone of the piece”10—from which we might gather two things: that Hamlet’s soliloquy was something of a classic, a set piece even in these early years of the German Shakespeare obsession; and that the soliloquy served as a kind of barometer of German Enlightenment thought, a touchstone for those practical questions of translation that fed into the deeper problem of language and its origins that intrigued literary thinkers such as Lessing, Herder and Hamann—a barometer as well for the much vexed issue of art as the formal expression of feelings (Empfindungen).11 Mendelssohn’s gloss on the monologue is worth having: “Of all the species of the sublime, the sublime of the passions, when the soul is suddenly bewildered by terror, regret, fury and despair, demands the most unaffected expression. A mind in anger is preoccupied with its emotion alone, and any thought that would put distance between it and its emotion is a torment. At the moment of a violent emotion, the soul is working under a torrent of images which overtake it. They all press to the point of exploding, and since they cannot all be expressed at the same time, the voice stammers and can scarcely utter the words that first occur to it.”12 In introducing the monologue, Mendelssohn sets the scene—gets into Hamlet’s head, so to say—and concludes: “Deep in these despondent thoughts, he steps forward, and reflects: Seyn, oder Nichtseyn; dieses ist die Frage!”13

Mendelssohn, discerning a reflective Hamlet, is contending here with the tension of the reasoning mind “overtaken” by its emotions. It was this very problem that consumed Lessing in his famous Laokoon of 1766, provoked in the first instance by the art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s analysis of what would become the most widely studied work of sculpture from Greek antiquity. Winckelmann, in his Reflections on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture (1755), understood the muffled control of Laokoon’s agony, that “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur,” as he memorably phrased it, as a characteristic of the Greek temperament. Lessing understood it rather as a constraint of the plastic arts, over against the literary, the narrative, the dramatic, for in Vergil’s Aeneid, Laokoon does indeed scream, “sending to heaven his appalling cries like a slashed bull escaping from the altar” (as it goes in Robert Fitzgerald’s poetic translation). For Lessing, it is the expressive moment, frozen in time, that is at issue. The ancient painter Timomachus “did not paint Medea at the instant when she was actually murdering her children, but a few moments before, while her motherly love was still struggling with her jealousy. We see the end of the contest beforehand; we tremble in the anticipation of soon recognizing her as simply cruel, and our imagination carries us far beyond anything which the painter could have portrayed in that terrible moment itself.”14

Lessing’s subtitle, “über die Grenzen der Malerie und Poesie”—on the limits of painting and poetry, as it is commonly translated, but with a sense, in “Grenzen,” of the porous boundary between them—invites its transliteration to that similarly porous boundary between Shakespeare’s monologue and Bach’s Fantasia that Gerstenberg explored: “über die Grenzen der Tonkunst und Poesie,” he might have been thinking. Contending, in a letter of 1767 to Friedrich Nicolai, that music itself, “without words, conveys only general ideas, ideas which however receive their full definition only with the addition of words,” Gerstenberg sought to justify his experiment, noting that it would succeed only “in those works for solo instrument … where the expression [Ausdruck] is very clear and speech-like [sprechend].”15 And yet it cannot have been clarity of expression that drew the poet to Bach’s singular work, but, rather, its obverse: a clarity of diction, perhaps, that masks the expression of something not at all clear. In his naive way, Gerstenberg touches on a quality in the music that is otherwise difficult to apprehend. If, by certain theoretical lights, music means exclusively as syntactical configuration among the notes themselves, this music, beneath the surface of its speechlike accents, yet seeks expression of something more obscure. In an essay titled “On Recitative and Aria in Italian Vocal Music” published in 1770, Gerstenberg wondered “whether it is not in the nature of song that words, which it uses as symbols, are transformed into tone paintings of feeling.”16 That Bach’s Fantasia would induce Gerstenberg to seek this transformative act through a coupling with—and a rewriting of—two literary situations of legendary profundity is itself suggestive of the convolutions of thought and feeling that the music was heard to embody. If Hamlet’s actual lines seem, in Stephen Greenblatt’s keen appraisal, a “formal academic debate on the subject of suicide,”17 Gerstenberg wants something very different: “To be or not to be: that is the great question. Death! Sleep! Sleep! And dream! Black dream! Dream of death! To dream it, ah! The blissful dream!” The reasoned discourse of debate gives way here to a rush of sensibility and Empfindung.

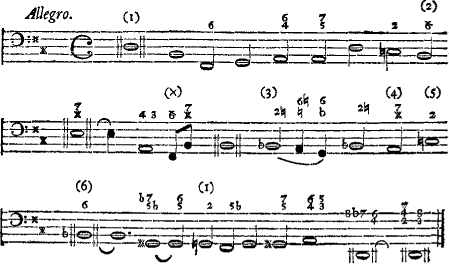

What was it, precisely, that provoked Gerstenberg to his experiment? One passage will have to stand for several. In the transition from the end of the Largo to the return of the Allegro moderato, the transformation of B♭ into its enharmonic homonym A# presses beyond simple diction. (The passage is shown in ex. 5.2.) The sheer intensity of the tone itself, seems to disgorge the insoluble nut of musical meaning from its midst. In its reach for the distant relationship, the enharmonic moment strains the process of thought. Inflected by Bebung, the single pitch seems in dispute with itself, as though all expression, all meaning, were reduced to this tremulous focal point.18 For if we take mimesis in its deeper sense as a representation of human experience in the languages of art—not, that is, as an imitation of some material and cognitive thing—then the music may be said to represent some unnamed expression, to actualize it, in language that yet had the power to move more deeply than experience itself.19

This, it seems to me, is the paradox that Gerstenberg set out to explore: while Bach’s music possessed an eloquence of expression—a Sprache der Empfindungen, in Forkel’s phrase—that was the envy of the poet, what it expressed could not be translated. To endeavor to capture its expression in the literary was to confuse means and ends, cause and effect. How, one might ask, could one verify of such a setting that the music was not conceived as an expression of Hamlet’s soliloquy? If one knew the Fantasia only in the Gerstenberg redaction, wouldn’t a post-facto paring away of Gerstenberg’s text leave behind a music that now seems unrealized in its expressive mandate? However we manage to explain it, Gerstenberg’s cunning experiment stands not least as a probe into the depths of Enlightenment aesthetics.

EXAMPLE 5.2 Sonata VI, Fantasia, from end of Largo.

That Bach’s Fantasia induced Gersternberg to find its equivalent in two literary passages that probe a state of mind in extremis must tell us something of the expressive power of this music. But it does something else as well. There are really two kinds of music in the Fantasia. Gerstenberg’s text is unobjectionable in the Largo, where the music moves in measured song. The diction of the poem is the diction of the music. In the severe aesthetics of Lied—as defined, for one, in the two lengthy essays (“Lied [Dichtkunst]; Lied [Musik]”) in Sulzer’s Allgemeine Theorie der schönen Künste—the music self-effacingly enhances prosody and diction: nothing more. Musical meaning is not in question. But the outer sections are very different in this regard. The music, unmeasured, means to emulate a process of mind in the midst of thought. Here, harmony is everything: not in formally arranged symmetries, but in its reach for the distant relationship. The enharmonic interval (only imagined on the keyboard, and consequently more poignant) strains the process of thought: the single pitch, inflected by its tonal environment, acquires two or more contradictory properties, seeming to carry on a conversation with itself.

Beyond the sense of this passage as expressive in and of itself, it seems as well to reflect upon earlier music in the Probestücke. Established as the root of a dominant in E♭ major, B♭ is then extricated, sounded in isolation, forte, with much Bebung. The new harmony beneath it, a bare octave and fifth on C, further isolates B♭, now a dissonant seventh, in company with E♭, an exposed leading tone. Further transformation is enacted in an extravagant phrase which places A# at its peak, rubbing viscerally against A#: B♭ has been converted enharmonically to a leading tone, its companion E♮ now seated deep in the bass as a seventh. The music is returned to the sharp side, and the extremities of this reversal invoke the two trajectories of the Probestücke at the crisis articulated between the fourth and fifth sonatas, exploring the resonant spaces between F# minor and E♭ major.

Whatever else they might be about, these eighteen pieces document a journey. As protagonist, the player works through the experience of an apprenticeship. If these pieces impart a pedagogical lesson, it is that one learns not through rote imitation of such things as form and style, but rather through the senses: genre is invoked as an adventure of the mind. This way of conceiving the journey will perhaps conjure Laurence Sterne’s Sentimental Journey through France and Italy (1768), a travel journal in no conventional sense but a record of sensibilities, of encounters of the heart: “a quiet journey of the heart in pursuit of Nature, and those affections which rise out of her.” “I have not seen the Palais royal—,” confesses Sterne’s Yorick, “nor the Luxembourg—nor the Facade of the Louvre—nor have attempted to swell the catalogues we have of pictures, statues, and churches—I conceive every fair being as a temple, and would rather enter in, and see the original drawings and loose sketches hung up in it, than the transfiguration of Raphael itself.”20

The heart, this temple of sensibility, houses not the grand work of art, with its pretension to formal perfection and finish, but the sketch, the drawing valued for the spontaneity of the artistic act. Sterne’s brilliant conceit takes hold of the process from the inside, where the idea of art is prefigured in the affects of human behavior. Hanging alone in the museum, the work of art is merely a frozen metaphor of living process. This distinction between the finish of art and the allusive traces of ephemeral process—Benjamin’s Death Mask, once more—puts us in mind of Goethe’s appreciation of the sketch, “those fascinating hieroglyphs,” wherein “mind speaks to mind, and the means by which this happens comes to nothing.”21

Sterne’s Journey ends in the Savoie, just before the crossing of the Alps into Italy. The expectation of arrival, not least in the sexual sense, is heightened in the erotic final scene: Yorick in bed, almost, with the elegant lady of the Piedmont, as though to suggest that he has indeed found his way to Italy. The book ends in pregnant mid sentence.22 A sentimental journey of another kind, Bach’s Probestücke explore a map etched in tonal regions and figured in genre. The peregrinations of Bach’s empfindsame traveler have an openly pedagogical, less erotic mission. In its poignant coming of age, the Fantasia in C minor signifies the inescapable return home, the impossible return to the place of blissful ignorance. For Bach, three years after the death of his father, the anxieties of this mythic return must have run deep.23 That Gerstenberg would hear in the Fantasia evocations of Hamlet contemplating suicide and Socrates about to enact his own may only suggest something of the inner agon played out in this extreme music.

The decision to place the Fantasia at the end, the ultimate Probestück, tells us much about its place in Emanuel Bach’s aesthetics. Fantasies are similarly placed in the three last collections für Kenner und Liebhaber (IV, 1783; V, 1785; VI, 1787). When we encounter fantasies in the music of the earlier eighteenth century, they, too, are about the improvisatory. One thinks, inevitably, of the Chromatic Fantasy of Sebastian Bach. But here, as elsewhere, the fantasy means to exercise the mind, and the fingers, as a preliminary: a tuning up, a gradual coming into focus before the reason of fugue. For Bach the father and Bach the son, the reversal is poignantly evident in how they constructed the repertories of their final years. For the father, the final works are grand summations, compendia of fugal ingenuity. For Emanuel Bach, the final keyboard work in the catalogue is the Fantasia in F# minor from 1787—C.P.E. Bachs Empfindungen, as he himself inscribed one of its autographs—a plangent fantasy of farewell, riddling and paradoxical, even in the contradictory signals transmitted across the pages of its two autograph redactions. But this is to anticipate the next chapter.