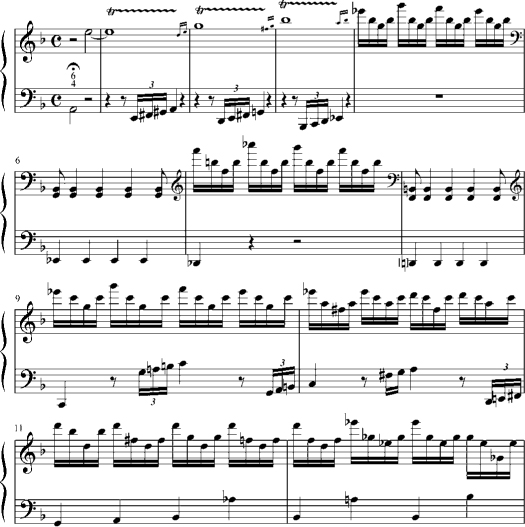

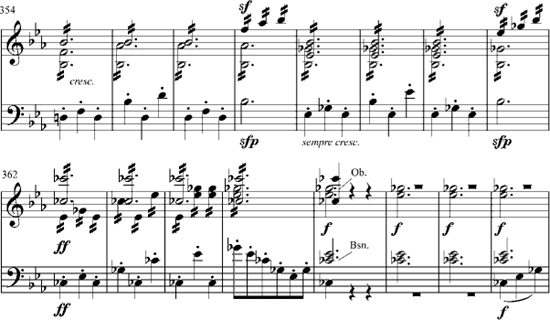

Mocking the uneasy composure of Mozart’s Concerto in D Minor through a diction and a posture alien to Mozart, the cadenza (ex. 9.1) threatens to dismember its host. The tunes are Mozart’s, but the touch, the rhetoric, is emphatically Beethoven’s. Manifesto-like, these opening measures insinuate themselves into the concerto, infiltrating the text.

Frequently played, Beethoven’s cadenzas (there is one for the finale as well) have entered the repertory in their own right. They follow ineluctably from the cadential six-four, feigning continuation of Mozart’s text. Critical reception has been ambivalent.1 To anyone inclined to such thoughts, there is the lingering sense that the cadenza, even in the fact that it exists, poses a threat to the integrity of the concerto. By the conventions that govern practice, we understand that Beethoven can have intended no such malicious tampering with Mozart’s text. All the same, the dedicating of the cadenza—of any cadenza—to the permanence of written record, the act of writing it down, constitutes in itself a violation of the rule, for now the cadenza intrudes into the workings of the concerto and assumes a textual presence that the conventions of the genre seem to disallow.

EXAMPLE 9.1 Beethoven, Cadenza, WoO 58/1, for Mozart, K 466 mvt. I.

The writing down of cadenzas, whether for didactic purpose or as private aides mémoires, is no doubt as old as the convention itself: to write a cadenza is to interpret in some metaphysical sense the call to improvise. The very idea of cadenza is burdened with paradox and enigma. In the syntax of Classical form, the cadenza elaborates an inessential prolongation of the six-four. Ephemeral by nature, its often pronounced imitations of substantive worth—of structural essence—are in the end untenable.

To what ideal should the cadenza reach? Is its improvisatory flight meant to be understood as an integral moment in the text? Could one imagine the perfect cadenza, without which the piece might be said to lose something of its substance and meaning? When Mozart composes the cadenza, must we take it to be expendable in a way that the other composed music in the piece is not? In asking these questions, I want to set aside for the moment the practical concern about cadenzas, and about Mozartean cadenzas in particular, commonly put in some such formulation as: What is the performer to do, two centuries too late, confronting the void after the fermata? This is a question that musicians must ask, but it is here a secondary one.

I

A commentary from without and within, the cadenza, as its name affirms, articulates the structural cadence of greatest weight, and so the music that happens here holds a privileged place. The music seems to stop, but that is illusory. The ultimate dissonance in the work, this quintessential six-four stands for all the others. Its resolution clinches final closure. The cadenza is an instance of shared rhetoric: seeming to part company, the composer and the performer—composition and performance—effect a rapprochement. The inner law that drives the piece and the outer rule that governs performance here move toward reconciliation.2

Invoking the embellished cadence at the close, the fermata at the six-four on the dominant signifies a precarious locus at which more is at issue than the competence of the player to enact a role. Oppositions, ambivalent and suppressed, are engaged. That one speaks here of the player and elsewhere of the composer is but one symptom of this ambivalence. It is now the player’s piece. The composer puts his music in jeopardy. In the performer, the adrenaline flows faster. Even when the composer and the player are one—Mozart performing his own concerto—the issue is unresolved: the player in the composer is set loose; the composer in the player is seen askance. More abstractly, here is the locus at which the composerly and the performerly (as Wölfflin might have put it) embrace. Engaged in the exercise of textual authenticity, in the quest for the signs of authorship, the cadenza slips away. The piece becomes inscrutable.

Even the earliest of those cadenzas from which Mozart and Beethoven might have drawn a lesson hint at ambivalences in function and significance. Perhaps the extreme case is the cadenza that Emanuel Bach wrote in the Largo of the fourth Sonata contained in the Probestücke, discussed in chapter 5 and displayed in ex. 5.1B. It will be good to recall Bach’s language here. The player is meant to imitate “the unpremeditated cadenza-making of two or three persons, and at the same time imagine that the one is paying close attention whether the proposition of the other has ended or not. Save for this [unpremeditated quality], cadenzas would lose their distinguishing attribute.”3

There is a hint, in Bach’s gloss, of what might be called a semiotics of cadenza: the music is personified in a mode at odds with the music that precedes it. The cadenza sets itself radically apart from its source. From the shock of the initial C# (m. 24), this cadenza in effect rewrites the piece, contradicting and disavowing the obsessive, overture-like music that is its main topic, and defining D major as a tonic no longer. In its ruminating discourse, the cadenza gives the illusion of the improvisatory. And it is precisely this illusory aspect that is itself an obligatory part of the message. The C# augurs a bold shift in narrative mode. The cadenza does not partake of the thematic substance of the music to which it pretends a commentary—and that is much to its point. That this cadenza is as well a passage of great poignancy, one of the cherished passages in all of Bach’s keyboard music, is perhaps a symptom of how the rhetorical place of the cadenza can be construed—and was so construed—as the occasion for high eloquence.4 It follows that the cadenza may utter music no less essential and obligatory than what we generally claim for the text proper.5

This is a paradox not often perceived. The cadenza, in practice and origin, makes manifest a notion of improvisation. But when the cadenza is composed (no matter to what end), this effectively contradicts a genuine aspect of its improvisatory nature. Its spontaneity is feigned, and so the notion of the spontaneous itself becomes the topic of musical discourse.

II

This obligatory sense of cadenza is now and then manifest in those of Mozart’s cadenzas that have survived. Given the fragile nature of the evidence, it would be wise to take the narrowest view of authenticity. Autographs are authentic. Everything else is less good and open to routine suspicion. The famous publications by Artaria and André include cadenzas that have survived in autograph as well, but this must not lead us to suppose that, by extension, each and every cadenza in Artaria and André must have been based, even at some remove, on an autograph text. Conversely, we ought not to assume that the loss of autograph is a sign of inauthenticity.6

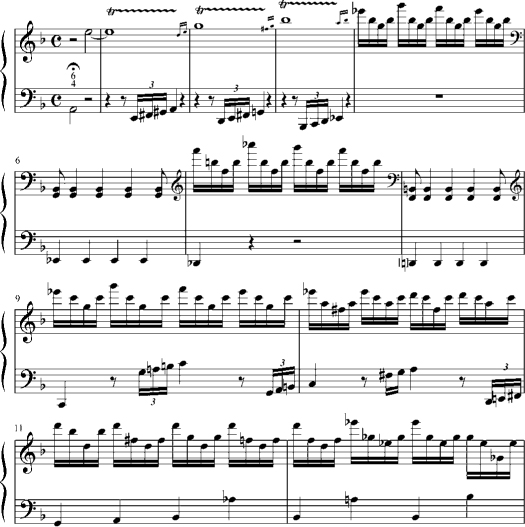

Among those published by André is a cadenza (ex. 9.2) for the slow movement of the Piano Concerto in G Major, K 453, that has survived in no other source. A pensive meditation on its environment, its discourse seems engaged at some intentional remove from the thematics of the piece.7 Here is a cadenza without the pedigree of an autograph. And yet authorship speaks out from its notes with the composer’s eloquence. If the thematic source, rhythmic and intervallic, for this eloquence is simple enough to decipher, it is rather in this suspended quality of discourse disengaged that authenticity is lodged. Seeming to rehear the piece from some privileged authorial outpost, the composer himself assumes a role in the narrative. This is no discourse that even the most adept Mozartean could invent.

In its obsession with certain locutions, pointedly in its plangent central measures (bracketed in the illustration), the cadenza issues an incisive commentary on salient aspects of the principal theme. And then the closing tutti—the telling E♭ in m. 125—seems to echo this very passage: the coda becomes a commentary on the cadenza.8 Can we justifiably perform the movement without this cadenza, even if the documentary support for its authenticity is weak? To do so would seem to violate an audible grain of integrity in the piece, for the cadenza makes some claim to an obligatory voice in the discourse.9 Without it, the movement cannot be said to fall apart as though through the excision of some vital structural element. And yet the rhetoric of the piece—a rhetoric innate in the genre—would be palpably diminished. The cadenza seems to take all the license that formal convention will allow. This friction between the structure of text and the moment of temporal stasis within it is cause for its own eloquence.

EXAMPLE 9.2 Mozart, K 453, mvt. II, cadenza K.6 626a, no. 50.

By its nature the history of cadenza must be inferred from evidence that is elusive and suggestive—theoretical prescriptions, blurred eyewitness accounts, and an occasional text. That Mozart should have bothered to write out his cadenzas must give us pause. To ask why he did so is to question whether the improvisatory ground rules of cadenza, even in the hands of a composer who would have had supremely little trouble complying with those rules, were perceived as a mask held up at the fermata: a mask that signifies improvisation but conceals composition. The point was not lost on Daniel Gottlob Türk, writing in 1789, who cautions that “a cadenza that has perhaps been learned by heart with great effort or written out beforehand must yet be performed as though hastily sketched, its ideas random and indiscriminate, had only just now occurred to the player.”10 If Türk is here addressing the pragmatics of performance, we might remind ourselves of that earlier paragraph and its footnote (see chapter 6), in which Türk conjures the cadenza as dreamlike: “We often dream through in a few minutes, and with the most vivid Empfindung—but without coherence, without clear consciousness—events actually experienced that made an impression on us. So too in a cadenza.”11 If the dream, in its “lebhaftesten Empfindung,” stakes its claim to the unconscious, to the irrational, the cadenza, in Türk’s provocative metaphor, may be said to capture this quality through mimesis, must feel to the player as though it were dreamed, a state of mind gained only by a certain process of reflection.

Who, one must wonder, is responsible for such eloquent dreaming? The question of agency is worth pondering. In these cadenzas by Mozart, it is the composer who preempts a moment otherwise given to the performer. But there is an unwritten understanding that what he plays here—as player—is taken to be improvised. The psychology behind this ambivalence is yet more complex. The concertos, perhaps to a greater extent than any other of Mozart’s works, are tied in with a proprietary sense that these things belong to the composer as performer.

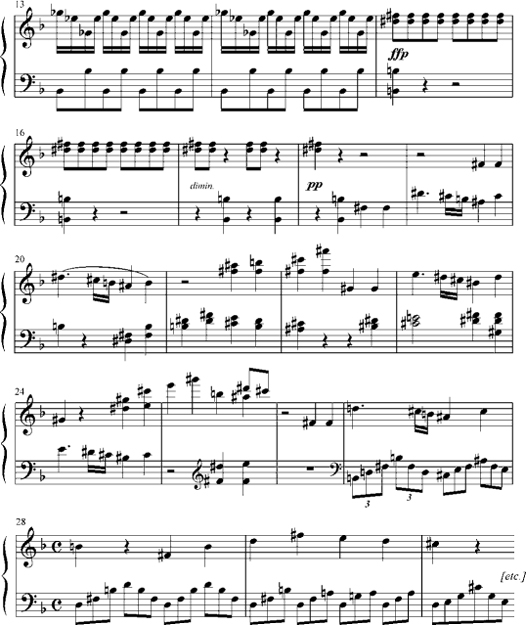

How the cadenza might play directly into the larger rhythmic sweep of the piece is keenly felt in the celebrated specimen for the first movement of the Concerto in F, K 459.12 Its opening measures sustain the thrust of the piano arpeggiations that drive the music hard toward the cadence that signals the end of the exposition and recapitulation (ex. 9.3). The arpeggiations, simple in the body of the concerto, splay out into three real voice parts. The text is subtly engaged. The cadenza, made to seem obligatory, participates in the temporal dynamics of drama.

III

The first three Beethoven concertos, perhaps more so than in other of his works from the 1790s, strain—and in some sense, fail—to measure up to some ideal Mozartean prototype. From the beginning, Beethoven seems to have taken the idea of cadenza as itself a provocation. What we know of the cadenzas that Beethoven had in hand during the 1790s can be only vaguely surmised from the scattered and fragmentary entries in the Kafka Miscellany. The earliest documented cadenza dates from the late 1780s—for a concerto that has not survived.13

The cadenzas for Opus 15 and Opus19, composed a decade and more after the composition of the concertos, violate the formal dimensions and indeed the aesthetics of these earlier works.14 They range well beyond the limits of the keyboard to which the texts of those concertos were bound. To take the most extreme instance, the crabbed, fuguelike vituperations in the cadenza for the first movement of the B♭ Concerto, an exercise in rhythmic obsession that prefigures the finale of the “Hammerklavier” Sonata and even the Große Fuge, repudiate the spirit and the substance of the concerto. In the cadenza, Beethoven dissociates himself from a work, indeed from a style, to which he could no longer subscribe. The cadenza holds no claim to authenticity in the sense that those Mozart cadenzas do. There is no genuine engagement here with the dramaturgy and diction of the concerto. The composer in the cadenza overrides the composer in the concerto.

EXAMPLE 9.3 Mozart, K 459, mvt. I. (a) Mm. 371–79.

(b) Cadenza, K.6 626a, no. 58, beginning.

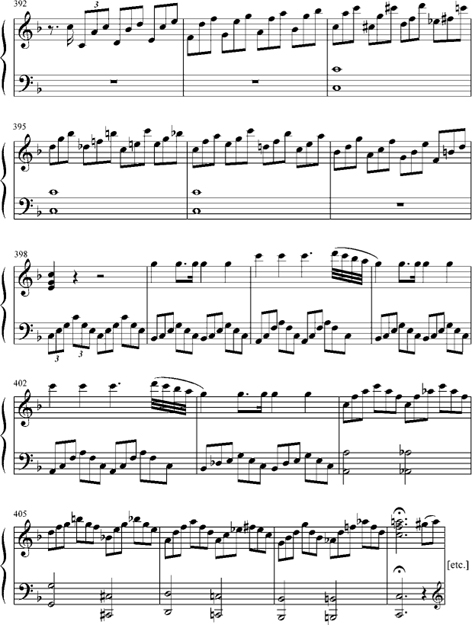

But the cadenzas for the first and last movements of K 466 (WoO 58) are different, for we must presuppose a reverence for the text that Beethoven might not have felt for a work of his own youth—even if, in the playing out of the cadenzas, some deeper antipathies surface. The circumstances under which they were composed remain a mystery. The manuscripts containing the cadenzas were at some point parted from one another; neither is dated.15 The cadenza for the first movement has left more of a trail. Its paper, produced by the Kiesling firm, displays a watermark that turns up in a number of manuscripts written by Beethoven no earlier than 1808.16 The manuscript itself was once in the possession of Ferdinand Ries, and this has led to the notion that the cadenza was written especially for Beethoven’s well-regarded pupil. Ries, away from Vienna after 1805, returned in 1808 as a pianist of some acclaim and remained there until 1809.17 There is a temptation to toss these cadenzas in with those others—virtually all that have survived for the first four published piano concertos and for the transcription of the Violin Concerto—that Beethoven is believed to have composed in 1809. The date itself seems to have sprung up from some general sense about the look of the handwriting in the manuscripts. Whether this in turn engendered the notion that the cadenzas were composed for the Archduke Rudolph, or whether it went the other way around, the argument in either case was based more on intuition than fact.18

As it turns out, the evidence for implicating the Archduke in the early history of these cadenzas had been there all the while. Studying the documents that record the Archduke’s Musikaliensammlung, Sieghard Brandenburg established that virtually all the cadenzas that have survived for Opera 15, 19, 37, for the piano version of Opus 61, and for K 466 (sixteen cadenzas in all) bear inventory inscriptions either in the Archduke’s hand or in the hand of Joseph Anton Ignaz Baumeister (1750–1819), the Archduke’s tutor and librarian from as early as 1801.19

Content to let facts speak for themselves, Brandenburg does not dwell on the circumstances that would have led Beethoven to furnish the Archduke with cadenzas for all his concertos (excepting of course Opus 73), and for K 466 as well. Although the Archduke did indeed own several Beethoven autographs, the preponderance of Beethoven manuscripts in the so-called Rudolphinischen Sammlung are copies, some even with entries and corrections in Beethoven’s hand. But the cadenzas, all preserved in Beethoven’s autograph, suggest different circumstances. Whether they were composed with some pedagogical mission in mind or to satisfy the Archduke’s appetite to control an archive of the “complete” Beethoven, cadenzas and all, we do not know.20 It must in any case now be acknowledged that the composition of a complete set of cadenzas for the earlier concertos was an exercise that had something to do with Beethoven’s relationship to the Archduke, for it seems clear that the terms of this relationship were to some degree refined as a result of the annuity agreement signed in March 1809.

If the cadenzas do date from roughly 1809, it is worth noting that they were written at a time when Beethoven had begun to take seriously his commitment to the instruction of the Archduke.21 One might go so far as to suggest that in them Beethoven sought to establish a theory of cadenza—that they constitute a repertory of exemplars from which such a theory might be extrapolated. This might explain how it happens that there are three substantial cadenzas for the first movement of Opus 15 (even if one of them is a fragment), all from 1809. But the cadenzas for K 466, even if they belong to this exercise, intimate other motives as well.

IV

Consider once again the opening measures of the cadenza for the first movement. What can they tell us about a theory of cadenza, of concerto? By any definition the construct is unusual. Three fragments extrapolated from the ritornello are reconstituted in a bold new configuration that radically redefines the somber affect of Mozart’s shadowy opening measures. The notation specifies no dynamics, no articulation. It hardly matters whether the pianist brutalizes the famous syncopations, fortissimo, in disrespect of their uneasy deportment in the concerto itself, or cradles them, pianissimo, as though contemplating some revered artifact from another age. In either case, Beethoven’s notation suggests an over-articulation. The extreme registral gaps, shifting with each measure, only contribute to a sense of what the theorists—recalling Forkel on Emanuel Bach—call Zergliederung, a term not easily rendered in English. “Analysis” belongs in its definition, but in the sense of a breaking down into component parts. That seems very much a part of the process here.

In its tonal spread, the cadenza violates the precepts of Classical decorum. The second theme is given in B major, where it is meant to sound exotic and remote. Is this a quality inherent in the theme itself? Do the parameters of a Classical style, and more narrowly, of the concerto, permit an evocation of the theme reheard as though in historical memory? Mozart’s cadenzas rarely, if ever, move beyond what could be understood as an elaboration of the true dominant.22 Beethoven, even in those earliest cadenzas (and fragments of cadenzas) preserved in the Kafka Miscellany, seems bent on radical tonal deflection.

To justify in some functional agenda the role of B major in the cadenza is a routine exercise. What appears as a simple B-major triad, following upon the six-four on B♭, is in effect the ghost of an augmented-sixth chord: B♮ is C♭. But this common relationship is abandoned. The dwelling on the simple triad itself, prolonged for four full measures (mm. 15–18) in which some meditative process of mind is suggested in a carefully notated vanishing act (fortissimo to pianissimo), dismisses any vestige of appoggiatura in E♭ minor, and lends to B major this distant sense of itself. The restatement of the theme in B minor, tracking the harmony back toward the actual tonic, serves as well to reinforce the exotic sense of B major.

The matter is yet more complex, for B major plays out at another remove the very striking relationship with which the cadenza opens. Established at the outset, E♭ major perhaps means to evoke the Neapolitan sixth struck emphatically in the tutti six measures after the cadenza, in analogue with mm. 49 and 54 in the exposition; E♭ is also a prominent area in the development, at mm. 220–231. But within the cadenza, E♭ is cast rather in terms of its own dominant (see ex. 9.4).

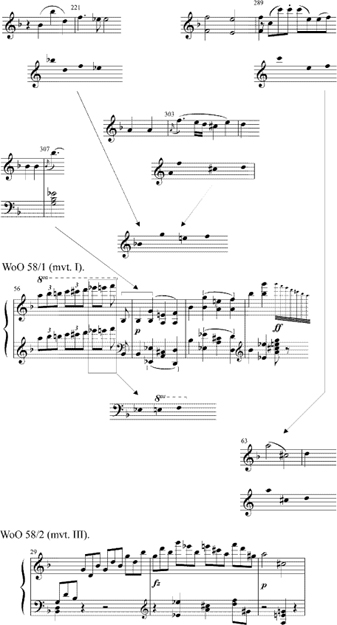

These interiors call vividly to mind another such recess—a locus classicus—at the great extremities in the first movement of the Eroica (see ex. 9.5). The point to be made here is not that Beethoven means to evoke the symphony in the cadenza, but that the rhetoric of the cadenza revives the tensions normally associated with the extreme dissonance of Beethoven’s development. This in turn suggests a misalignment with the place and idea of cadenza in Classical concerto.

EXAMPLE 9.4 Beethoven, WoO 58/1, mm. 13–16 abstracted.

It is again to E♭ that the cadenza returns, in a moment of quiet before the rush to the cadential trills. Zergliederung is here pressed to an extreme, for this cryptic phrase seems to draw up within itself much of the music of the cadenza in an abstraction meant to stand for the intervallic core of the concerto. Rhythmic displacement only intensifies this sense of the abstract.

And perhaps it is for this reason that the phrase is made to recur at the analogous moment in the cadenza for the finale. The recurrence is no simple echo, even if that were the intention.23 For it is an axiom of Classical form that the movements of this or that work, no matter how persuasively they may be shown to belong to one another, are by definition self-contained: their “themes” are exclusive of one another; they do not depend on one another for their sense. So that when this phrase, original in the cadenza, is quoted nearly verbatim in the cadenza to the finale, a transgression is committed. Through its repetition in the cadenza for the finale, the phrase is made significant beyond what is permitted in the equation that dictates sense between cadenza and text. Further, the recurrence concretizes the abstruse sense in which the two movements may be said to share thematic substance: the cadenzas make explicit what can only be inferred from the text of the work. Through Beethoven’s cadenzas, an analytical abstraction is made to work its way into, or just under, the text of Mozart’s concerto. Something of the allusive, convoluted process at play here is attempted in ex. 9.6. These intervallic permutations put us in mind of what Carl Dahlhaus, writing of Beethoven’s next decade, would call “subthematicism,” of a thematic “retreat into latency … that can be seen as a sign of a profound change in the concept of ‘theme,’ which has always been observed in Beethoven’s late style.”24 The ramifications of Dahlhaus’s insight are pursued in our next chapters, but I want only to suggest that the symptoms of a mode of thematic abstraction are evident in these cadenzas: the Dahlhausian notion of subthematic, to the extent that it is manifest here, is all the more provocative in that Beethoven’s cadenzas distill from Mozart’s concerto, and thereby make explicit in it, a complexity of thematic abstraction that is in some sense foreign to its style.

EXAMPLE 9.5 Beethoven, Opus 55, mvt. 1, mm. 354–69; winds, brass, and timpani omitted in tutti.

These, then, are no cadenzas in the Mozartean sense. The continuity of Mozart’s discourse is not in question. The music is stopped dead in its tracks. Beethoven contemplates Mozart’s text. The process is analytical—a probe into the Geist of the concerto. In the cadenza, we hear how the early Romantics might have understood their Mozart, and more pointedly, how this concerto must have reverberated in Beethoven: how aspects of Mozart’s style, however controlled in the works themselves, exaggerate themselves in Beethoven’s mind, and in his fingers. But Beethoven’s cadenza is itself no analytical abstraction. It is meant to be played. A performance—the phenomenon of performance, even idealized and imaginary—reifies what otherwise remains abstruse.

EXAMPLE 9.6 Beethoven, WoO 58: some intervallic relationships.

We shall never have a clear sense how Beethoven, even as late as 1809, reconciled his place in a personal history that may be said to begin agonistically with Mozart. The engagement with Mozart’s music is documented as early as 1785, when the violin sonatas published by Artaria in 1781 were taken as working models during the composition of the three Piano Quartets, WoO 36.25 And it extends to the late music, for we now know that the Kyrie fugue in the Requiem was much on Beethoven’s mind during the sketching of the Missa solemnis in 1819–1820.26 In between, Mozart’s music—ensemble passages from the great operas, in the main—is copied out in contexts that suggest less a searching for specific models than an exercise meant to establish some deeper accord with Mozartean process.

But the cadenzas are different in this regard. Here, the engagement with Mozart is openly confrontational: Beethoven’s notes jostle with Mozart’s in this most public of genres. As always, there is a subtext. It cannot be that Beethoven misunderstands Mozart, that he miscalculates the work. Beneath the bluster of Beethoven’s attack, one senses the playing out of some deeper antipathy, difficult to define, but surely dyed in this lifelong struggle to conquer the rigorous self-control imposed by Mozartean example. The equilibrium of the concerto—and by extension, the Classical style—is assaulted. Even the conventional signs of Classical cadenza are turned on their heads: the cadenza for the first movement begins with the trill that would signify its close.

It is a simple enough matter to dismiss these cadenzas as an aberration foreign to the style or to celebrate them for their propinquity to the concerto in time and place. But this is to read only the surface of their significance as historical document. We learn from them more of Beethoven’s agenda than of Mozart’s text—the concerto heard through the afflicted ears of a composer whose style was forged in the aftermath of a Mozartean legacy that had, even in the 1790s, grown to mythic dimensions.

In the end, the cadenza falls away, a foreign agent unacceptable to the host. The text returns to its symbolic fermata, its blank six-four. If these cadenzas do in fact date from 1809, they are coeval with a concerto of Beethoven’s own. One might imagine that it was this encounter with the fermata in K 466 that would have led Beethoven to recoil at his own fermata in the “Emperor” Concerto, Opus 73. “Non si fa una cadenza, ma s’attacca subito il seguente,” he instructs the player.27 “One does not make a cadenza, but attacks the following directly.” What the pianist attacks is an obbligato cadenza, conservative to an extreme. The dominant, B♭, is in effect sustained from the beginning of the cadenza, at m. 497 straight through to the tutti at m. 530; there is no moment when B♭ is not literally sounding in some voice.

The retrenchment to a cadenza of Classical scale in the E♭ concerto should not be taken to mean a return of the genre to some classically conceived model. The “Emperor” Concerto is a work on the grandest scale, and the control of its cadenza is only a symptom that the formal tension once resident in the cadential six-four is now to be found elsewhere. Similarly redefined is the dialectic between the composed and the improvisatory. In the grand cadenza-like arpeggiations with which the pianist announces the concerto is hidden an epistemological statement. The verities of Classical form are challenged. Where once the flight of the performer was checked and limited to the single moment where formal syntax can tolerate such indulgence, this social contract is now redrawn.28 The soloist, now granted the power to engage the process on some new level of narrative discourse, is written into the text as fictional protagonist, a creature of the composer’s fantasy. What was once a genuine investment in the sensibilities of the performer is sacrificed. The pretense that the performer can be made to sustain the composer’s voice is abandoned.

In the cadenza in F# minor—the crux, one might say, of the entire set of Probestücke—we are drawn intimately into the conceiving of Emanuel Bach’s text. To play the cadenza is to live vicariously as Bach’s ideal player. And this is true of Mozart’s cadenzas for K 453 and K 459, where the text is similarly engaged. If we do not in fact improvise, the music yet gives the sense of having been improvised, as though the performer, able to capture the moment of conception, becomes the composer as he himself might have performed the piece. In Beethoven’s Opus 73, the game is different. This fictional protagonist assumes a role in the autobiography of the composer. The cadenza is made prescriptive. In playing it, we enact a script. The player is put at greater remove from the process of the piece, even if the text gives an illusion to the contrary.

To play Beethoven’s cadenzas to K 466 is to be enmeshed in a process of quite another kind. The pianist is the player in a bizarre psychodrama. Does he pretend to be Mozart or Beethoven? How does he negotiate between the two? The cadenzas are not conciliatory: to play them is to take up Beethoven’s cause. The cadenza dictates how the concerto will go, and not the other way round. In more than a manner of speaking, Mozart’s concerto becomes Beethoven’s.

Whatever their other virtues, these cadenzas constitute a unique record, embedding as they do the clearest signals how Beethoven construed a Mozartean text, and even how he performed it. Its signals in this regard are not without that ambivalence that is itself a characteristic aspect of the message—a sign, one wants to say, inherent in all notation and in all texts. That Beethoven should have thought that Mozart’s suave second theme would sound well in B major is a symptom that hints at performerly decision making. More than that, it is a commentary on the idea of a Classical coherence. In the concerto, B major is an excluded key. In Mozartean cadenza, the tonal spectrum is more exclusive still: B major is an implausible key, and a misplaced locus for any of the principal themes, which in Mozart’s cadenzas are relegated to the tonic alone. It is not enough to tolerate B major here on the pretense that Beethovenian cadenza is less restrictive in its tonal play. The cadenza is a function of the concerto. When Beethoven applies the precepts of his own cadenza-making to a concerto that is not his own, he incidentally violates the ground rules of Mozartean cadenza. But the transgression is yet more pernicious, repudiating the Classical notion how a cadenza elaborates a cadence—how, that is, it enhances the structure of the piece.29

Beethoven’s cadenzas do not serve the structure of the concerto. They may be about structure in some existential sense, and may even enhance it. But they do not partake of that structure, do not participate in its rigorous hierarchical game. Primary evidence of the most vivid kind, they catch Beethoven in a revealing indiscretion. We restore Mozart’s text, return it to Mozart. But the cadenzas remain, memorial to an act of artistic impropriety. To those for whom history sails along with the prevailing winds, they are aberrations without consequence, curiosities better left in limbo. To others, they situate a moment in history, a critical one in which the past is caught in Beethoven’s lens and a precarious future glimpsed.