We return once again to Friedrich Schlegel, whose poetry Schubert much admired, even as it set him daunting aesthetic puzzles that his music could not always solve. Of his writings on literature and art, the most frequently cited are the briefest: the aphorisms contained in the “Athenäums-Fragmente.”1 Taken all together, they adumbrate a theory, not of course in any systematic, expository mode, but in the cumulative experience of the apparently isolated thought, one after another, each brilliantly obscure, and it is only on reflection that Schlegel’s journey of the mind unwraps its thematic congeries.2 These aphorisms, splinters of thought, seem often commentaries upon their own fragmentary condition. A few of them have been appropriated to the arguments of earlier chapters. Another touches on a quality in Schubert’s music, and in the man himself, that will be explored in the pages that follow:

A fragment, like a little work of art, must be quite separated from its surroundings and complete in itself—like a hedgehog.3

That a fragment must, by Schlegel’s lights, be complete in itself is a thought tinged in paradox. It nourishes that other apparent contradiction between fragment by accident and fragment as a quality immanent in Romantic art—“apparent,” for we are speaking here of two conditions that, in a criticism of art, have only remotely to do with one another. The work left unfinished may, in its substance, powerfully intimate “finish” in some Classical mode. The Romantic fragment may possess all the attributes of the work conventionally “finished,” and yet its very meaning conjures those powerful intimations that reside in the “unfinish” of the Classical fragment. The Romantic work reads into the Classical fragment a mystery not intrinsic to its meaning, constructing from its misreading an imaginary condition to which it aspires.

In what follows, I mean to suggest that the fragmentary state of at least one of Schubert’s works—the great, if unfinished, Sonata in C major (the so-called Reliquie), D 840—owes its condition, in the actual sense, to this romantic notion of what might be called a conceptual fragment. For while it is commonplace to speak of a canon of unfinished works by Schubert, we might imagine Schlegel taking the adjective “unfinished” to be a condition describing all those works of Schubert worthy of exploration—an unconditional adjective meant to convey that quality in Schubert’s music without which the work fails in its claim to the Romantic condition.

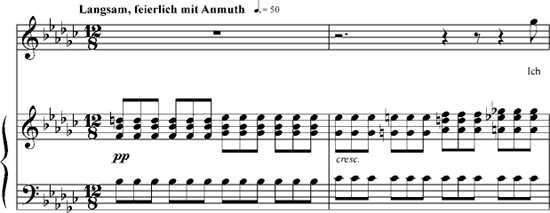

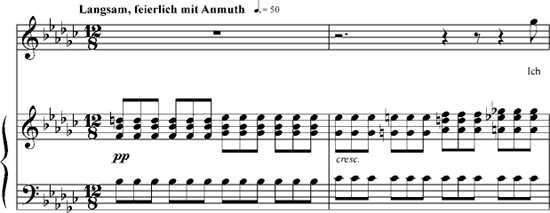

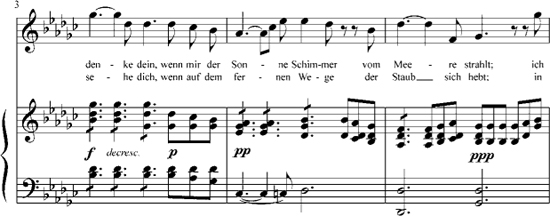

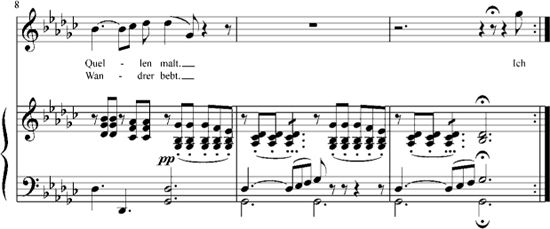

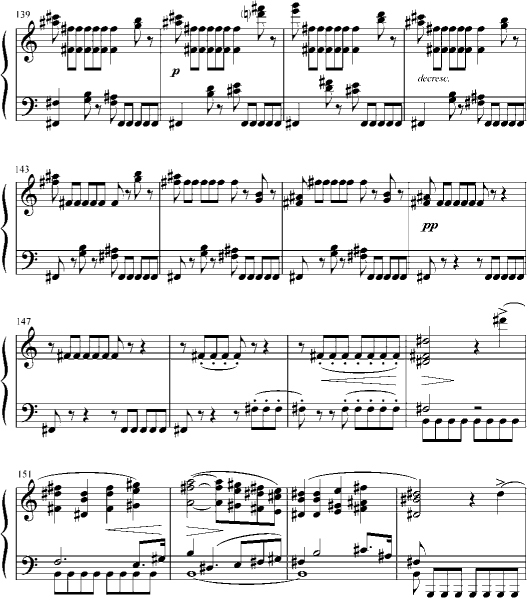

One senses often enough that this aspect of unfinish, in the Romantic sense, is at odds with some prior commitment to the Classical imperatives. The three versions of Nähe des Geliebten, D 162, a setting of a poem by Goethe, convey something of these ambivalencies. (They are shown in ex. 14.1.) The song, universally admired, has been too thoroughly studied to require a lengthy defense of its beauty, or even of its significance in Schubert’s evolution.4 For we must continually remind ourselves that the song was composed in February 1815—129 songs earlier than Erlkönig, by simple count in Mandyczewski’s chronological edition. It was composed on 27 February, a day on which Schubert evidently set down the song in two versions. The third version, written out in 1816 for the Liederheft sent by Spaun to Goethe, was subsequently published as Opus 5 no. 2 by Cappi & Diabelli in 1821.5

EXAMPLE 14.1 Schubert, Nähe des Geliebten, D 162.

A Final version, Cappi & Diabelli, 1821.

EXAMPLE 14.1B First version, from an autogr. dated 27 February 1815.

C Second version, from another autograph (private collection) dated 27 February 1815.

It is the singer’s final note that is troubling. That it troubled Schubert as well is evident in that the three autographs give three different final notes. Surely, the earliest of them is the bravest, the most daring: the singer ends on D♭, the fifth degree of the scale—does not end, that is to suggest. The song is then construed in two huge phrases. The first of them begins in soaring mid flight, and sketches out a firm sense of cadence. The second at once explores the vacant spaces in that first phrase and probes the implications of those mantic bars with which the piano opens into the song. But here the singer is left hanging.

When, later that day, Schubert wrote out the song a second time, he fixed the meter and reconceived the metrics of the opening bars: the grander 12/8 meter now matches the expanse of the phrase rhythms and translates the distance of the key itself, the exotic G♭ Now the singer ends on B♭ Again unsettling, the B♭ disturbs the tonic in a way that the D♭ does not, and prepares the return of the root position dominant on B♭ with which the song begins, and to which each of the three subsequent strophes returns. This second version moves, we might say, from the naive to the sentimental. The D♭ is perfectly innocent. The B♭ is complicated, even a bit neurotic. In both instances, the voice gives nuance to the subjunctive mood of Goethe’s “O, wärst du da!,” the haunting final line with which the poem refuses to end.

In the published version, these opening bars are not repeated. The voice now completes its second phrase. The song is “vollendet.” Schubert has given it finish. To engage in sterile debate whether we have an aesthetic right to perform one of the settings of 27 February in place of the published version is clearly not to the point here, nor would I want to argue—or even to allow that one could argue—that either of the two is “better than” the third. Rather, I want simply to suggest that these earlier versions have a value for us in thinking about the song in its troubling of the concept “finish.” Schlegel’s notion of the Romantic “Dichtart” as a poetics that by its nature rejects the very idea of completion is here strikingly apropos.6 And that puts before us an aesthetic conundrum: for while we can speak of the work itself as aspiring to some Hegelian state of “werden”—of perpetual becoming—we must at the same time recognize that we are speaking here of a metaphoric process within the boundaries of the work and a function of its style. Romantic artists do finish their works, do finish even those works whose substance means to suggest that they hadn’t quite done so.

A sonata that Tovey, among others, held to be among Schubert’s loftiest, most subtle works, yet one that Schubert could not bring himself to finish, the “reliqued” Sonata in C major of 1825 has been celebrated in the recent publication of a facsimile of those leaves of its autograph that have survived, together with a brace of essays that explore aspects of its paradoxical status.7

The two movements that remain unfinished are the Menuetto (but not the Trio) and the finale—and they seem to have been left unfinished for different reasons. In some sense, the less interesting of them is the finale. Paul Badura-Skoda surely goes too far in suggesting of it that “the unfinished last movement cannot rise above a few short-winded and ineffectual flourishes, and was surely abandoned for this reason.”8 Yet there can be no question that in Schubert’s major instrumental music from these years, the finale is something of a problem—is perceived, at any rate, to be problematical. Tensions at home in the discourse of sonata are relaxed in the prolixities of the strophic song-miming that often suffuse the finales. In this instance, the music breaks off at measure 272 with the end nowhere in sight: Badura-Skoda’s completion for the Henle “Urtext” runs to 556 measures.9

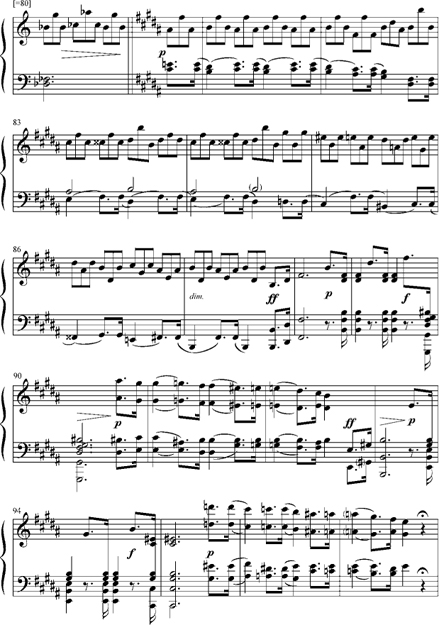

The Menuetto is problematical in a different way. Consider how and where it ends (a facsimile of the autograph is shown as fig. 14.1). The rhetoric of recapitulation is strongly felt—fully eighteen bars on the dominant, beginning at m. 57 (see ex. 14.2). But the dominant of what? The power of persuasion here is such that Elizabeth McKay, in one of those exploratory essays, was led to write that the opening theme now returns “in the tonic.”10 The Menuetto, however, is in A♭ major, even if its sights are set on A major early on. And so the deeper implication in McKay’s formulation is provocative, even for an epistemology of “fragment.” Why is the piece unfinished? Why, further, did Schubert write “etc etc” after those few half-hearted bars of reprise—and then, leaving no space for a return to the problem, proceed to write this perfect Trio? Cast in G# minor, the Trio dwells on an obsessive D# conceivably meant to echo the closing bars of the Menuetto (which of course we do not have), just as the D#s at its close anticipate the opening notes of the da capo.

McKay’s harmless oversight yet hints at anxiety around what might be called the problematizing of tonic in Schubert’s music. Is there not something essential in the music to suggest that the truer tonic is indeed A major, and that A♭ provides a foil—a conventional frame within which to understand this central and predominant A major? Much to the point is Alfred Brendel’s poignant insight: “In his large forms, Schubert is the wanderer. He likes to move at the edge of the precipice. To wander is the Romantic condition.”11

FIGURE 14.1 Schubert, Sonata in C major, D. 840, third movement, page from the autograph score. Vienna: Stadt- und Landesbibliothek (Wienbibliothek im Rathaus), Schubert MH 4125. By kind permission.

Certainly, we follow Schubert precipitously close to the edge in this passage—over the edge, perhaps, if that is what its fragmentary condition signifies. In no other menuetto or scherzo—indeed, in no other sonata movement—do we find the music charting its reprise in the flat supertonic. No less radical—differently radical—is the tonality of a scherzo in E major that was evidently intended to follow directly on the first movement, left incomplete, of the Sonata in F minor, D 625 (studied at the end of the last chapter).

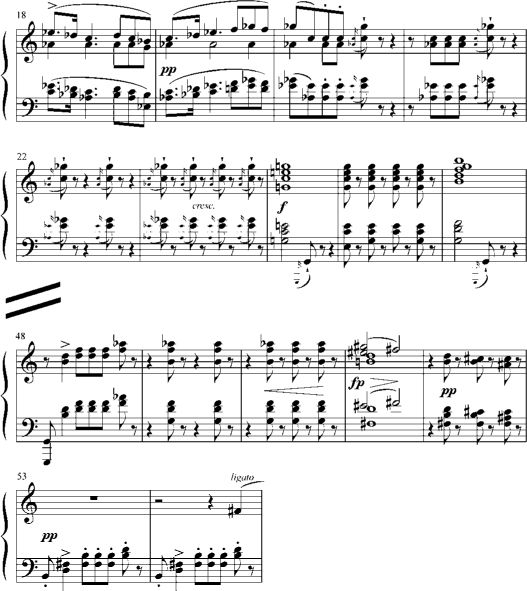

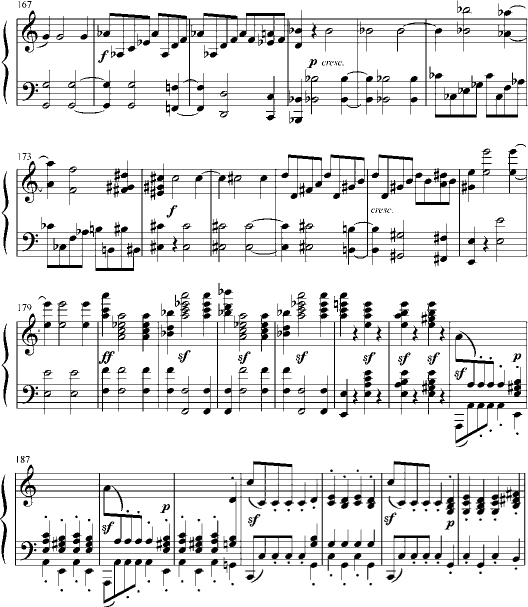

EXAMPLE 14.2 Schubert, Sonata in C major, D. 840, third movement.

If there is a movement that springs to mind as comparable in its breathtaking challenge to the conventions of reprise, it is the first movement of this Sonata in C major. (The passage is shown as ex. 14.3). Eventually, of course, the music makes its way back to C major. And if one should quibble—as many do—about the precise moment at which “recapitulation” sets in, that would be to quibble about the wrong issue. Rather, one wants to admire the apparent contradiction of a return to C major approached through the back door and the affirmation of B major, with its luminous D# sounding the Romantic sixth in ecstatic response to twenty-four big measures on a dominant F#. The grand gestures of resolution, removed to this exotic key, are tinged in the sublime. The opening theme coalesces into something visionary, a coherent phrase (fusing what, at the opening of the movement, seem four discrete pieces of a puzzle not yet in composite, four phrases in search of a source) now enhanced with a new inner voice that makes audible the silent “innere Stimme” that Schubert’s poets are forever invoking. What follows we hear as liquidation of this one signal moment.

These twenty-four measures on F# are decidedly in B minor, and so the resolution in B major is yet another instance of modal inflection in the service of some veiled poetic message—again, the trading in metaphor. Further, the theme, very nearly as it will sound in B major, issues forth in A major at the outset of the development. Andreas Krause, in another of those exploratory essays, speaks here of two dovetailed “fifth-axes”: the one, extending from the B minor established early in the exposition, through what he calls F# major (those twenty-four bars that must be heard as a dominant), to the B major in what he calls the Scheinreprise; the other axis, this A major at the outset of the development and the D major which he understands as the last station before what he identifies as the “return for the first time of the complete and characteristic thematic shape” in the subdominant at mm. 169–176.12 If the fixity of these tonal axes, embedded as they are in the tonal landscape, is incontestable, one might yet contest their agency to elucidate what the piece is ultimately about. This Scheinreprise—the term itself redolent of the illusory, the feigned, the false, thereby diminishing the sense of the moment as epiphanic—seems to me to come in fulfillment of its premonition in A major. The larger step-motion in the course of all this is palpable, suggestive not only of Stufen, in the literal sense in which Schenker might have graphed it, but of Aufhebung, in all the senses comprised in that Hegelian concept: at once of elevation (even in the mystical sense) and dissolution. Compellingly, Hans-Joachim Hinrichsen speaks of these keys as “Durchführungsränder”—the keys at the margins of the development: A major as “Einsatztonart” and B major “als Punkt der ‘Verschmelzung’ von Durchführungsende und Reprisenbeginn”—the point of fusion between development and recapitulation.13

EXAMPLE 14.3 Schubert, Sonata in C major, D. 840, first movement, mm. 139–166.

This moment of Aufhebung has its narrative mission, evoking, as it does, an instance of B minor in the interiors of the exposition. No ephemeral passing harmony, B minor in this earlier instance comes in resolution of a memorably enigmatic phrase (shown in ex. 14.4). The simultaneity at the downbeat of m. 51 is less important for what it is—its dissonant tones are quickly enough parsed as so many appoggiaturas to a six-four on F#—than for what it signifies. Even the sense in which this dissonance translates the dominant seventh in C major in m. 50 to, in retrospect, an augmented sixth in B minor is conventional enough. But the harmony in m. 50 is a dominant ninth—and the ninth, as Kirnberger did not fail to remind us, is an inessential dissonance to the essential dissonance of the seventh: its resolution is local, provoking no change of root. But of course this ninth does not resolve to G. It becomes (in the Schlegelian sense) a very different creature. An essential tone, A♭ is now made over into G# above a putative root C#—all of this sounding somewhere in the crevices between mm. 50 and 51, so that the residue is understood as a suspension of that fifth above C#.

Do we hear this translation of the dominant ninth as some enharmonic jeu—Schubert at play—or as the inevitable next step in the harmonic plotting of the work? The rhythm of the passage is of a piece with the rhythms established in mm. 21–24, prompting the ear to seize the deeper relationship implied here. Even as the music plays out some theoretical imperative in its descent into B minor, a lowering shudder issues from it at m. 51. Here is the crux. The conventional key of the piece is brought into conflict with an unconventional, overwrought B minor. When the gesture returns in the recapitulation (see ex. 14.5), it is purged of all tension, whether one speaks here of resolution or of some quality less teleologically inspired.

More than a point in some axis of tonal relation (though of course it may be understood as that), B minor is fitted out with the rhetoric of poetic conceit. I return again to those twenty-four measures on F#. Has anyone ever counted the precise number of F#s struck during this passage? The question was asked—and answered—of another F#: the one sounded 536 times in Die liebe Farbe.14 Among pieces in B minor, Die liebe Farbe is hardly alone in its fixation on F#.Irrlicht and Der Leiermann (from Winterreise) belong here, and so does In der Ferne (from the Rellstab group), where the turn to B major, an epiphany of another kind, echoes, if faintly, the events of the Sonata.15 B minor holds a special place in Schubert’s tonal lexicon. Consequently, we are driven to ask whether the key itself, as raw poetic substance, means to signify beyond the intervallic relationship that it establishes with the tonic—to signify, that is, in a tonal metaphor that means to conjure poetic image.16

EXAMPLE 14.4 Schubert, Sonata in C major, D. 840, first movement, mm. 1–26; 48–54.

EXAMPLE 14.5 Schubert, Sonata in C major, D. 840, first movement, mm. 203–214.

Back to Schlegel, and his aphoristic groping for an understanding of Romantic art as fragmentary, as “nie vollendet” in its essence. There seem to me three ways in which the Sonata in C major stakes a claim for this prized condition of unfinish—of fragment. In the most trivial of them, it is of course unfinished in that its two final movements were never completed. In a less trivial sense, the autograph invites us to speculate whether this written record is in the nature of a Reinschrift or an Entwurf—whether a clean copy meant for other eyes and further transmission, or a preliminary draft. If the former, then we cannot speak here of fragment in this elemental sense, for the Reinschrift presupposes some earlier iteration in which the work was conceived, was conceptualized, was drafted: the Reinschrift, not habitually the locus of such conceptualizing, cannot therefore signal the breaking off of the concept. But Schubert’s autographs are frustratingly ambivalent in the signs of their status in this regard. What begins calligraphically with the confidence and good posture of Reinschrift is transformed often enough in the course of the piece into the improvisatory: the writing loosens, and we feel ourselves now in the presence of the conceptualizing of the work. Hinrichsen, in that same essay, ponders the paradox of the fragment, broken off in mid-flight, but written in the sure hand of the Reinschrift. “‘Fragment’ ist also nicht gleich ‘Fragment,’” he notes, in an aphorism worthy of Schlegel.17 We are returned to that riddling page from the Menuetto, where the manuscript is ipso facto made over from Reinschrift to Entwurf.

In its third sense we approach the Schlegelian fragment: fragment as ruin, ruin as evocative of something lost and irretrievable, the finished work as the suggestion of something unfinished. This is the Romantic fragment.18

Nowhere are the symptoms of such fragment-making more pronounced than around the much vexed problem of reprise—of recapitulation. No moment in the narrative of sonata so unsettled Schubert. Two unfinished sonata movements—the F# minor, D 571, from July 1817, and the F minor, D 625, from September 1818, to single out the best known—break off precisely here, where the recapitulation is evidently meant to begin. But even this is ambiguous, for in both cases, the music breaks off on the dominant of the subdominant. The claim was put forth at the end of the previous chapter that the actuality of their fragmentary condition is bound in with the new problematics of sonata itself, at just this point where the music stops. The two notions of fragment—of work left unfinished; of music that pursues some distant tonal region only vaguely commensurate with its framing tonic—seem to fuse here: the work is unfinished because the concept how it might be “finished” does not come clear.

And then there is the telling example to the contrary. A preliminary Entwurf has survived for the first movement of the B major sonata from 1817. It too breaks off at the moment of recapitulation. But whereas the recapitulation in the final version begins in—rather, lurches into—the subdominant, the draft is equivocal, suggesting even that the Scheinreprise is the one in the tonic (see ex. 14.6).

There are of course commonplace and mechanical explanations for these enigmas, but they cannot be the right ones. To suppose that Schubert in 1817 was oblivious of the dynamics of an inherited Classical sonata—to suppose that the weight of this legacy was not heavy on his mind—is to underestimate him. But by 1825, the insoluble nut of these experimental works of 1817 and 1818—fragments in our first sense—are addressed in two very grand sonatas: the C major fragment, and its companion from the spring of 1825, the Sonata in A minor (D 845), published only months later as Première grande Sonate …, Opus 42.

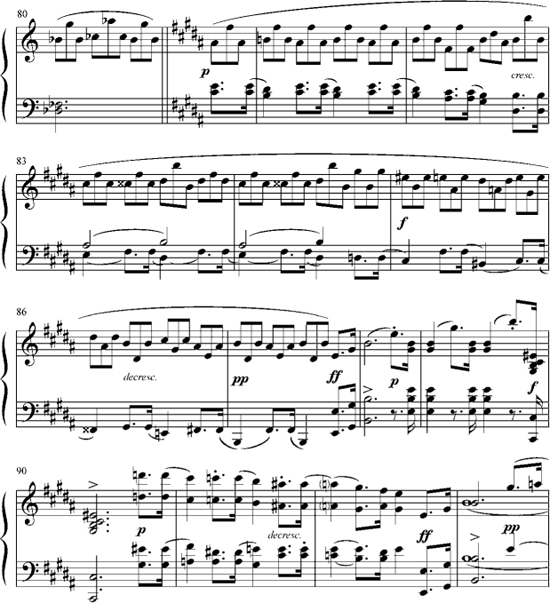

In the first movement of Opus 42, the reprise is no less a matter of perplexity. (It is shown in ex. 14.7.) The deep A in the bass at m. 134 establishes a defining dominant in the subdominant, sustained (though embellished) through m. 143. But then the music seems to vanish altogether in a breathtaking, and nearly inaudible, dominant in F# minor. The opening theme returns—reluctantly, and in bare, self-reflective counterpoint with itself: first, in F# minor, then in A minor (but only in passing, for we have no sense of true tonicity here). A broader continuation is established in C minor. As it is in the first movement of the “Reliquie,” the tonic is here established finally at a moment of structural accent well along in the unfolding of the principal theme.

Different as they may be in their local strategies, these two sonatas from the spring of 1825 together convey a profound disquiet at the idea of reprise. One senses a reluctance to return—an unwillingness to celebrate the advance to the tonic, to concede, in the return to the opening music of the sonata, that this music is about the tonic. To go at it from another angle, we inevitably measure these moments against the prototype. Whatever Beethovenian example comes to mind—even an abstract conflation of them all—we hear in it the antithesis of this Schubertian hesitation about conquest and triumphant retakings. For Beethoven, the tonic is an article of faith, the implacable doctrine that paradoxically sustains him through all his dialectical efforts to unseat it. How to read Schubert in this regard? Brendel, again: “To wander is the Romantic condition.” The return home, a return imposed by the deepest theoretical conditions of sonata, is now questioned at its root, probed, problematized.

EXAMPLE 14.6 Schubert, Sonata in B major, D. 575, first movement.

A From an earlier draft (Vienna: Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde).

B The published version (Diabelli, ca. 1844).

This ambivalence about recapitulation, I mean to suggest, has something to do with the inclination, in the earlier sonatas, to undermine the act of return. To return in the subdominant is somehow not to return. The subdominant is an evasion: a substitute for the tonic, it has the taste of melancholy. The triumph, the aesthetic satisfaction of return is of another age, another temperament. In the two sonatas from the spring of 1825, this inclination is given mature expression in two passages that capture, as do no other works of Schubert, the pathos of his own agony, in the reconciling of classical orthodoxies with a life at the precipice.

EXAMPLE 14.7 Schubert, Sonata in A minor, D. 845, first movement, mm. 142–193.

FIGURE 14.2 Pencil drawing by Moritz von Schwind (“Schubert am Klavier”), undated. Vienna: Austrian National Library, Bildarchiv, 460.760-B. By kind permission.

Finally, there is the pencil drawing, recently discovered, of Schubert “Am Klavier” by Moritz von Schwind (see fig. 14.2).19 It is a sketch, a fragment by the criteria that define the “Reliquie.” How might it have been finished, how might Schwind have finished it?20 The questions are simply wrong. To suggest that one might have the power of imagination to engage in the infinitely complex process of decision making that would have enabled Schwind to take the next steps is to display an arrogant belief in the infallibility of historical “knowledge.”21

The Schwind drawing, without much Schlegelian argument, is complete in itself. It is a concept, and a bold one, for it captures a Schubert conveyed in few other authentic representations:22 the arms in motion, negotiating some Erlkönig-like bravura (the invisible “Klavier” is only implied); the face, nearly an expressionistic abstraction of mind and thought, consumed in music-making. The ubiquitous spectacles, fused in the visage, only intensify the concentration: “durch die Brille,” to borrow from the title of a Viennese journal of Schubertiana. The central figure in Schwind’s “Schubert-Abend” may have more finish, but he is less engaged.

A “Nähe des Geliebten” in which the voice will not bring itself to end; a grand sonata that Schubert cannot bring himself to complete; and Schwind’s probing sketch—these artifacts tell us something about Schubert, and I am not sure that what they tell us is of lesser value than what we can learn from those published and public versions of works that lay claim to a more conventional finish. In Schwind’s drawing, Schubert is himself without finish—set apart from the “umgebende Welt” (in Schlegel’s phrase), beyond the conventions of human context. He does not stop to look at the camera, to set himself in time and place, to acknowledge a world around him. A hedgehog, he is, in the bold Schlegelian sense of the word.23