Behind the shameless pretense of its title, the modest intention of this chapter is to come closer to the disorderly notion of fragment, as the term was employed in the decades close on either side of 1800. Any such theorizing would need to reconcile two extreme conditions of fragment: on the one hand, fragment taken to denote the flawed torso of the work left unfinished; on the other, fragment taken to suggest the Romantic condition toward which even the finished works of those volatile years might aspire.

Clearly, when we speak of fragment in this revered aesthetic sense, we mean something quite distinct from those memorably unfinished works that constitute a poignant and cherished repertory in the larger catalogues of the works of, in particular, Mozart and Schubert. (Beethoven figures here as well. Among the thousands of pages of sketches and drafts are now and then embedded the more substantial drafts of works never completed, often obscurely implicated in some larger compositional project, and thus less distinct as self-contained fragments.) The unfinished work is a fragment, even if it can stake no claim to that sublime condition toward which Novalis and Friedrich Schlegel point in any number of well known aphorisms on the subject. Perhaps the most familiar of them is Schlegel’s ironic comparison of the works of the ancients that have fallen into the state of fragment with those of the moderns that are made fragmentary in their origins (“bei der Entstehung”).1 Another speaks less to fragment than to a condition affecting the Romantic work per se, a condition that defines the work as Romantic at its core: “Other poetry is complete, and can thus be thoroughly analyzed. Romantic poetry is still in the process of becoming; indeed that is its characteristic essence, that it forever only becomes, and can never be completed.”2 For Schlegel, the truly Romantic work, ill at ease in the brilliant, classicizing glare of enlightenment, will resist the clarity of cognition that analysis—a concept itself borrowed from the sciences—claims to achieve. To suggest that the finite, completed work is ever in a state of “becoming” is to argue for its condition as permanently unfinished, a condition stubbornly unresponsive to analysis as it is commonly practiced. Romantic art, warns Schlegel, will demand new modes of understanding.

The work unfinished in this Schlegelian sense yet depends paradoxically upon a text that is complete: by all the conventions of art, closed, finished, vollendet. The converse makes this clear. If the work is demonstrably incomplete, how can we know that it means to suggest the fragmentary? The power of the text lies in its meaning, but we cannot approach this meaning if we cannot claim to possess the text that would convey it.

These unfinished works by Mozart and Schubert invite us to propose some interpretive construct—theoretical, critical, even metaphysical—that might explain how it comes that the work was not finished. The problem is not of the kind for which we can expect prima facie evidence toward a solution. That the unfinished work is by nature a problem to be solved—that its finish is a puzzle given to solution—is a suspect assumption that asks for trouble. These fragments challenge us to say why we should not value them for what they are, for the immediacy of their expression, unmediated by whatever constraints might be imposed between a conception and its formal perfecting. It is precisely this immediacy that caught the eye (if not the ear) of Goethe in his admiration of the artist’s sketch:

Good sketches by great masters, those enchanting hieroglyphs, are usually the start of an enthusiasm for art. Drawing, proportion, form, character, expression, composition, harmony, finish are no longer in question: they are replaced by the illusion of themselves. Mind speaks to mind.3

The artist’s draft that Goethe admires, even in its fragmentary evocation of what is missing, is formally coherent in a way that an unfinished draft by Schubert is not, it is often argued.4 This distinction is perhaps better understood as one of apprehension, a difference in how we perceive the temporalities of music and the spatial dimensions of graphic art. It is not that the one is demonstrably more complete than the other, but only that the two modes of expression embrace the idea of the work along vectors of different kinds—putting us again in mind of the distinction that drives Lessing’s argument in the monograph on the Laokoon: “über die Grenzen der Malerei und Poesie” (on the limits of painting and poetry), as it is subtitled, for which one might here substitute “Malerei und Tonkunst.”5

The distinction between the work left unfinished, a fragment for no discernible reason, and the work that aspires to the aesthetic condition of fragment, whether or not it has survived complete, ought to be clean and simple. Often it is neither. For while these two conditions of the fragmentary might seem mutually exclusive, they yet invite dialectical inquiry: the unfinished work interrogated for traces in its torso that might suggest why it remains unfinished; these traces further interrogated for evidence of the Schlegelian aspiration toward fragment. To put it differently, we want to know whether the aesthetic pull of the fragmentary is coincident with a music that will not allow of closure.

The problematics of this distinction are exercised in several grand works by Schubert that have entered the repertory in spite of their fragmentary condition. The Symphony in B minor, D 759 (1822) and the Sonata in C, D 840 (1825), both complete in only their first two movements, stake legitimate claim to a place in the performer’s repertory. Such a claim is less certain of two sonatas whose first movements have survived only as fragments. The Sonata in F# minor, D 571 (July 1817) and the Sonata in F minor, D 625 (summer of 1818) have nonetheless established themselves in the repertory—not as fragments, but as works completed by other hands. In these acts of completion, the work is always debased, deprived of its authenticity. The more adept the forgery—for that is what is at issue here—the greater the damage. Indisputably, a unique value of these fragments is in what they record of a process of conceiving. Where the writing stops, we are witness to a moment, captured as though in a snapshot, where the split-second decision making of creation fails. Encrypted evidence revelatory of musical process, the fragmentary autograph documents this failure and invites further investigation into causes and consequences.

But the appeal of the fragment has its visceral aspect as well. To read through a fragment by Mozart is to be caught in the vicarious enactment of that chilling moment where the thought is broken and the writing stops. It is to Alan Tyson that we owe a penetrating insight into the complex run of papers comprised in the autographs of several of Mozart’s piano concertos, and of other works as well, that led him to suggest that a work may have lain dormant as a “fragment” for a good stretch of time—the autograph may tell us precisely where the writing stopped—until the external incentives to complete it had been internalized with some compelling urgency.6 But in those cases where only the fragment remains, so, too, does the question whether Mozart intended ever to return to it. And yet the very survival of the fragment may stand as evidence that Mozart had not conclusively given up on it.

1

Consider, for one, the well-known fragment of a String Quartet in G minor, K 587a (Anhang 74), composed, it is now thought, between 1786 and 1789.7 (It is shown as appendix 13A.) In the bold gestures of its fifteen opening bars, its motives formed from the big, expressive intervals in a calculated unfolding of the total chromatic (only B♮ is missing), the thematic stakes are set very high. The second phrase, at m. 5, is less a consequent of the first than an intense compression of its last four notes. The process of mind seems so concentrated as to provoke some theorizing as to the process itself. Are we witness here to a spontaneous flow of linear speech? Or did Mozart pause after m. 4, uncertain how to continue? If it is not given to us to know the answer, we may yet sense that this fleeting moment of reflection was of considerable consequence for the future of the work. In the deep A♭ at m. 11, briefly tonicized, one senses a similar moment of intense reflection, setting forth signals of a complex harmonic unfolding. This is extreme Mozart.

In apparent retreat from such demanding challenges, the music that follows at m. 16 is something of a disappointment: eight bars of hard thumping on tonics and dominants underpinning a conventional flight of sixteenth notes, a deliberate denial of the intense music to which it is an answer. But it is the final wisp of a phrase with which the music trails off that has something to tell us of its fragmentary condition. The phrase seems a cry of protest, a breaking away from this incessant harmonic rhythm, a search for something new: a key, a rhythm, a tune, a fresh voice. Even at the simplest level, it allows for any number of plausible readings of an underlying harmonic track (see ex. 13.1 for one). Mere conjecture, they are, for we cannot know precisely what this unfinished phrase wants to say. Perhaps it spilled from Mozart’s pen in a spasm of impatience with the entire project. It is the kind of phrase that might well have fallen away, had Mozart returned to complete the work. We however must live with it, and with the ambivalent readings that it seems to signify. The inclination to complete this unfinishable phrase confronts us with the ultimate riddle of the fragment as a species, for it assumes access to a process of mind that is unfathomable even within itself.

EXAMPLE 13.1 Mozart, Quartet Movement in G minor, KV 587a: hypothetical continuation.

It is not the harmonization of the phrase, or even the logical next step in its unfolding, that is at question, but a prior matter having to do with the imponderables of the mind that could give us this phrase with one hand and take it back with the other.

2

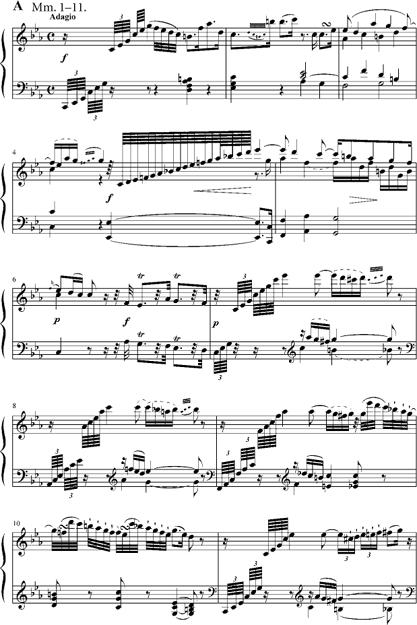

Mozart did not return to this fragment. We do, and for good reason: the pathos of its opening music is only intensified by the permanence of its fragmentary condition. Another memorable fragment is the remnant of a keyboard fantasy in F minor, K 383C (Anhang 32). Earlier prevarications in regard to the date of the fragment may now be set to rest, for both Alan Tyson and Wolfgang Plath have established that the paper-type and the handwriting of the fragment situate it in 1789, and not—as its Köchel number suggests—in 1782.8 The music of its opening phrases, lavishly complex, reaches hard for the gestures of spontaneity. (The fragment is shown as appendix 13B.)

The hortatory arpeggio, its extension in a more varied arpeggiation (just as Emanuel Bach taught), the speechlike utterance, the sigh, the cutting dissonance, the entwining of chromatically inflected inner voices: the signs of fantasy are profuse in its opening bars. The voicing of the harmonies in m. 2—the unprepared A♭ (and the seventh in which it is compassed), suspended dissonantly above the diminished intervals of a flatted ninth whose implied root is C—is powerful and focused. The concentration of dissonance deployed across the entirety of bar 2, the unfolding of its single harmony, is intense. What appears to be a simple tonic triad at the downbeat of the measure is in effect a dissonant appoggiatura. The bass wants an E♭, in turn implicating a root C. At the second half of the measure, a high A♭ is struck from the seventh below, from a B♭ that is itself a seventh above the root. Against this array, the D♭ in the following chord, a ♭9 above the root, now stirs the memory of that very pitch at the end of m. 1. The pile-up of dissonance in m. 2 has an immediate effect, forcing the bass to take its first step in a chromatic descent to the dominant at m. 5. But it is to that dissonant A♭ that the ear returns, and so does the music, which now establishes A♭ as a tonic. At m. 13, A♭ is redefined as a ninth above G and at m. 14 it is returned to the bass as a dissonance of another kind, supporting an augmented sixth, resolving finally to G, now the root of a dominant, as if to respond at last to the unresolved A♭ in bar 2. From its isolation in bar 2 as a “difficult” dissonance with a complex theoretical pedigree, the high A♭ seems to control the discourse of the entire fragment.

“Fantasia,” Mozart wrote at the top of the score, and yet the half cadence with which the fragment breaks off signals a second group in the dominant, more sonata than fantasy. (In the labyrinth of its opening pages, the great Fantasy in C minor, K 475, in search of a key, settles gradually onto the dominant of B minor: the true dominant is studiously avoided in the course of its 181 bars.) More problematical, I think, is the new music in A♭ in mm. 7–11: a banal sigh (and its banal answer), a stiffly dotted scale that bumps its way down two octaves, and an inflated operatic cadence that belongs a hundred bars later: dolce, twice written, doesn’t help. What kind of music might have followed the cadence at m. 14 is anyone’s guess, and I suspect that Mozart himself must have felt the impossibility of finding an appropriate tone in the wake of this fitful beginning. If we return again to its probing opening bars, we do so for that shiver of expectation, even to conjure ourselves as witness to the spontaneous moment of Mozart at his keyboard.

3

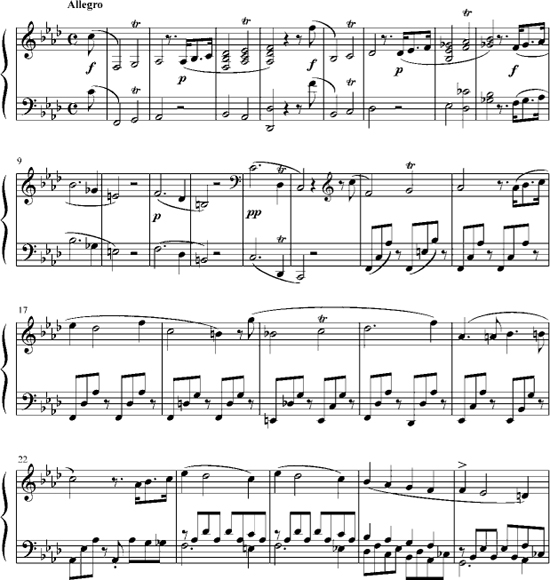

The opening bars of another unfinished work, a torso in C minor scored for “[cemba]lo” and violin (to judge from the double stops toward the end of the fragment), spring to mind. This is the famous “Fantasia” that everyone knows in Maximilian Stadler’s completion as a formidable work for piano alone, published in 1802 as Fantasie pour le clavecin ou piano-forte, and registered in the canon as K 396 (K 385f).9 The fragment, however, breaks off at m. 27 with a cadence in the relative major at a double bar with repeat marks, inscribing the exposition of a sonata movement, written exclusively for keyboard alone until the entry of the violin five measures from the end. The leaf itself is so severely trimmed on all sides—not, one suspects, the handiwork of Goethe, who acquired the manuscript in 1812—that any trace of title and tempo is cut away.

To contemplate the fragment is to confront riddles at every turn. How Mozart might retrospectively have worked the violin into a texture so otherwise saturated is not at all clear, and perhaps it was this initial miscalculation that led Mozart to stop composing. Was Mozart thinking of something along the lines of the rich, fantasy-like opening of the Sonata for Piano and Violin in G major/minor, K 379 (K 373a)? Whatever he had in mind, we can confidently exclude “fantasia.” This is a sonata exposition without question, and Stadler’s completion of the fragment, not quite the “Fantasie” that its title claims, does nothing to contradict this fundamental premise. In Stadler’s continuation, an overwrought middle section (mm. 33–45) evokes the turbulent passage beginning at m. 84 in the second movement of the Concerto in D minor (K 466) and the great crossing-of-hands passage in the middle of the Adagio e cantabile in Haydn’s Sonata in E♭ (Hob. XVI/49), even as it elaborates a more generalized conception of the “fantasy-like” development, inspired, it might seem, by Beethoven’s recent music. The date of its publication squares well with what we know of Stadler’s engagement with the fragments then in the possession of Constanze Mozart.10 The date is not trivial, for it sets Stadler’s work at a distance of some twenty years from the composition of the fragment.11 The cataclysmic events of those intervening years would have made the distances seem greater still. To those who had only begun to come to terms with the convulsions of revolutionary Europe, an apprehending of this brave new world would necessarily see the old through a distant focal point. The music of 1782, in the fine, calibrated tension between its passions and its constraints, must have seemed remote in its preoccupations, impossible to recapture in 1802 with any fidelity to its aesthetics.

In Stadler’s completion of the fragments, such tensions are no longer so finely calibrated. Even the simple cadence before the double bar in the C minor fragment is the subject of some tinkering (see ex. 13.2). The fine dissonance of Mozart’s appoggiatura is neutralized, the deep E♭ removed from a position of metrical weight. More problematic is the very first phrase in Stadler’s completion (ex. 13.3). The reformulation of the opening arpeggiation in C major is startling. Stadler was very likely thinking of the opening of the development in the first movement of the Sonata in C minor, K 457, a work that he would have had in front of him if, as would make good sense, he was studying that other Fantasy in C minor, K 475, published in a pairing with the sonata in 1785. Are the two passages analogous? In the sonata, C major is at once established as a dominant serving to establish F minor. Its function is never in doubt. In Stadler’s Fantasy, the opening phrase undergoes a transformation. The harmonic function of C major, in its motion to an apparent Neapolitan sixth, is unclear; the voicing in the right hand (D♮ –C–D♭) is awkward; and the three-note motive at its end seems an immaterial rhythmic distortion of the original motive, the kind of mutation foreign to Mozart’s style. There is even a question as to the essential voice leading here: it would appear that Stadler wants a first-inversion triad, with E♮ in the bass moving to the F. But the sounding of the deep root at the outset counteracts that hearing: the E♮ is merely an inner voice.

EXAMPLE 13.2 Mozart, Sonata Movement in C minor, KV 385f, cadence at end of exposition.

Problems with the fine-tuning of such voicing is evident as well in Stadler’s recapitulation. (The opening bars of Mozart’s exposition and of Stadler’s recapitulation are shown in appendix 13C). At m. 4, Mozart doubles E♭ in the bass, and redoubles it in the run of sixty-fourth notes up to the extremity of the highest E♭, establishing by implication a simple triad in root position, so that the change of bass at the very end of the measure has a true harmonic function. The B♭ strongly implicated as the fifth of the triad on E♭ now silently becomes a seventh above C, resolving to A♭ at m. 5. In the analogous passage (see m. 49), Stadler revises. Without question, the very deep G will be heard as the third of a triad whose root is E♭—the turn around E♭ in the right hand makes this explicit. And when the swift run up from the turn finds its target on a high G, the third of the triad, again heavily accented, is now redoubled in the extreme outer voices. When the bass moves, the root does not. Mozart’s elegant harmonic fluency is replaced with a solecism, a weak transformation of the original.

EXAMPLE 13.3 Mozart, Sonata Movement in C minor: Stadler’s continuation.

The move to E♭ major here is itself a bit odd, for the music at once finds its way back to C minor. Finally, a half-cadence in C minor at m. 60 is answered by the second group, now literally transposed to C major. If Stadler were casting about for models from the 1780s of first movements in the minor mode that close in the major, he’d have found plenty.12 But the issue is not quite that simple. In the first movements of certain kinds of works, Haydn will move to the tonic major at the second group in the recapitulation—a splendid example is the String Quartet in F# minor, Opus 50, no. 4—though never in simple transposition. In the sonatas in C minor (XVI:20), B minor (XVI:32), G minor (XVI:44) and C# minor (XVI:36) for keyboard alone, all composed in the 1770s, Haydn reformulates the second group in the tonic minor, in each instance with rich alterations. For Mozart, who in such circumstances only rarely closes in the tonic major, the challenge to recompose the music of the second group in the tonic minor, not merely an issue of technique, produces music whose pathos seems the only sensible conclusion of a work conceived in the minor mode. Perhaps the most poignant instance is the close of the Adagio in B minor, K. 540: the second group is recomposed in B minor, the major subdominant in the exposition made over into a breathtaking arpeggiation of the Neapolitan. The minor mode is sustained with an out-pouring of chromaticism over a dominant pedal, and it is only at its resolution in the final three bars that Mozart allows D# to sound, and the sheer, unexpected beauty of this tone, so long withheld and immaculately prepared, sets loose an exquisite cadencing of complex four-voice part writing in celebration. In contrast, Stadler’s shrill E♮ at m. 61, in response to the half cadence in C minor, is altogether unprepared, the brilliance of C major misplaced and jarring. It does not help matters that once again, Stadler writes an awkward cross-relation: E♭–D–E♮.

We cannot of course know how Mozart might have thought to complete this work. Stadler’s completion—rather like Süssmayer’s completion of the Requiem13—has had a long and profitable run of its own. What is at stake here is not a question of legalities, of intellectual property, but something deeper. Stadler’s hearing of the fragment filters out the complex decision making, the obscure, unrecoverable agon inherent in the compositional act. What he composes, putting the best light on it, is a different kind of work, one in which Mozart’s music is made over into an imitation of itself. Charles Rosen, identifying a “classicizing” tendency in certain works of Beethoven composed in the late 1790s, writes of a “reproduction of classical forms … based upon the exterior models, the results of the classical impulse, and not upon the impulse itself.”14 Stadler, driven by his own impulses, sought to reinvent Mozart. In the end, the music that he wrote plays against the grain of Mozart’s voice.

Hearing a similar playing against the grain, Ernst Oster, in a probing study of the chromatic Menuetto in D major for keyboard, K 576b [olim K 355], was inspired to penetrate the hard shell of a text that has survived only as a completed work to imagine in its place an original fragment completed by another hand.15 The Menuetto was published in 1801 together with a trio whose author was openly acknowledged to be Maximilian Stadler.16 Without the testimony of an autograph (whose whereabouts remain unknown), Oster’s insight cannot be verified as “fact.” That, however, does not lessen its significance for a coming to terms with the elusive evidence—often masquerading in the devilish details—that bears on the hard-wiring of authenticity: how do we know that we’re in the presence of a Mozart, or, for that matter, of a Stadler?

The gist of Oster’s argument resides in a hearing of the recapitulation of the opening music when it returns in the tonic. (The complete piece is shown as appendix 13D.) At the moment of return, the opening bars are reconceived. What follows is mechanical. For Oster, “the most persuasive argument against the authenticity of mm. 33ff lies in their exact transposition, note for note, of mm. 5ff.”17 The rote transposition beginning at m. 33 creates a difficult leap—an ellipsis, we might generously call it—between the half cadence on the dominant at m. 32 and the simultaneity on the downbeat at m. 33. Oster thinks it “slightly awkward,” and explains: “Although contrapuntally correct, d-sharp1 does not seem to come from anywhere and is weak in comparison to the powerful accented passing tone a-sharp in m. 5.”18

Is it in fact “contrapuntally correct”? The answer to that question lies somewhere in the bedrock of the passage beginning at m. 33 (and its analogue at m. 5). We understand the D# in m. 33, as we do the A# in m. 5, as an accented appoggiatura proceeding elliptically from an implicit, understood pure fifth. At m. 5, there is no difficulty in hearing the A which precedes the A#. It is elegantly prepared, just as the G♮ in the tenor resolves to the F# in the soprano. At m. 33, nothing is prepared. We are asked to intuit a direct motion between a triad on A and a triad on G♭: in effect, a direct motion between the dominant and the sub-dominant, both in root position, that violates a cardinal injunction in harmonic theory and reducible to the stepwise motion between two consecutive major thirds forbidden in pure counterpoint.

In these passages at mm. 5–10 and 33–38, the accented appoggiatura means to establish the sixth, in the usual 5–6 progression. The sixth is then augmented, setting loose a sequence of augmented sixths, in which the bass (D in m. 5, G in m. 33) is made over into the lowered sixth degree leading to the root of a dominant. In the exposition, the sequence is broken at the downbeat in m. 9, where (by the conventions of Mozartean sonata) the music moves toward the key of the dominant. The breach here is a telling one, a syntactical dissonance resolved, we come to expect, only when the passage is “corrected” in the reprise. But that is not what happens in the Menuetto. The breach between mm. 8 and 9 is simply transposed at mm. 37–38: a structural dissonance is compounded at just that point where the music wants not disjunction but resolution, correction, closure. And this, it seems to me, is the strongest evidence for believing the reprise to be inauthentic.

Precisely how the Menuetto might have gone in some version with more convincing claim to authenticity is to invite alternatives shrouded in speculation. The conundrum-like sequence itself suggests why Mozart may at this point have stopped writing. In the spirit of the speculative, consider how this passage might have gone with the “correction” shifted to the breach between mm. 36 and 37—focused, that is, precisely where the exposition established its crux (see appendix 13D and ex. 13.4). The syntax is strengthened, and the unbroken motion in the bass suggests an augmentation of the new counterpoint which celebrates the moment of return in mm. 29 and 30—C♮B, B♭ A—a further iteration of the chromatic descent in the soprano at mm. 17–20. But something is given up as well. The motion of roots in mm. 33–38 in the published version can be heard to put great emphasis on the dominant of the dominant, just as the local dominant on the third beat of m. 36 is heard to shore up the minor subdominant on the second beat of m. 38.

EXAMPLE 13.4 Mozart, Menuetto for Keyboard, KV 576b, voice-leading of recapitulation rewritten, mm. 33–39.

In the end, the proposal to hear the work as incomplete has a certain appeal. The arguments for doing so encourage a yet more radical image of where the writing stops—where, that is, the concentration of thought is broken:

EXAMPLE 13.5 Mozart, Menuetto for Keyboard, KV 576b, imagining where the autograph might have broken off.

To imagine the thought broken precisely here, at the incipit of a recapitulation that would need to come to terms with these bold new counterpoints, is to bring forward an aspect of Mozart’s style that is not often discussed. Unlike Haydn, for whom the recapitulation offers the challenge to vast and penetrating recomposition, Mozart seems often disinclined to engage in substantial rethinking at this stage of the work. These new counterpoints, which deftly compress the harmonic motion at mm. 17–20, might be thought to propose the kind of radical re-composition that Mozart was reluctant to undertake. And so the work was left unfinished.

The moral is sobering. The posthumous completion of works left in a fragmentary state is a dangerous game. The inclination to make over the fragment into an artifact of finish and aesthetic appeal, accessible to the market where art is consumed, may seem a virtuous one. Such deeds, innocent and high minded though they may seem, necessarily trample on the integrity of the work, oblivious of the fragile web of decision making that attends the conceiving of the work, trivializing and obliterating this poignant moment where music is silenced.

There is perhaps a lesson here for the student of Schubert’s fragments as well, for it would be good to ponder whether these sonata movements from 1817 and 1818 were left unfinished only because the external incentives to complete them were not immediately envisioned. Schubert did however manage to compose complete piano sonatas during these years. If, as seems entirely plausible, these unfinished sonatas were conceived under much the same circumstances that nurtured the completion of other works, we are challenged to come to some other understanding of their fragmentary condition.

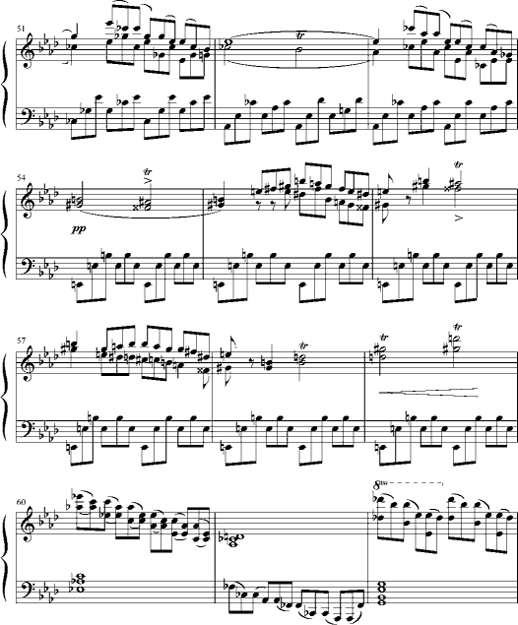

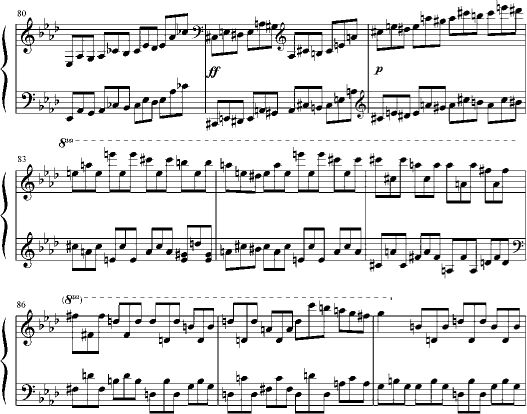

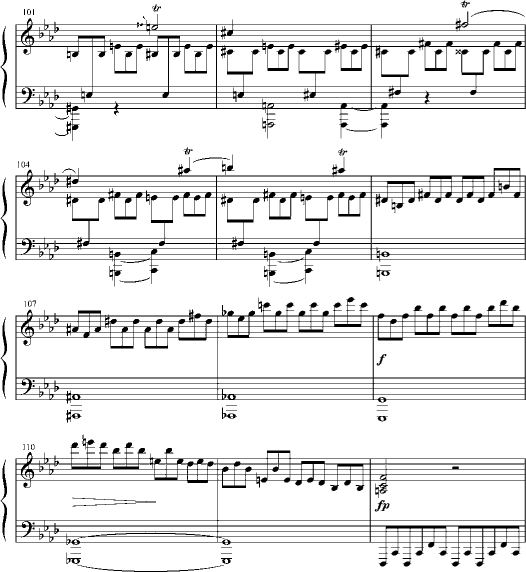

Where the ambitious first movement of Schubert’s Sonata in F minor breaks down at the end of a Durchführung of unorthodox intensity, the challenge is keen. (The movement is shown in appendix 13E.) Apart from two initial references to the opening motive, it gets nowhere to seek out thematic “development” between the double bar and the dissipation of the music at m. 112. The music strains impetuously, for the remote key, the uncommon harmonic utterance. The passage at mm. 94–106 is the crisis, probing an aggregate of tones whose bearing to the tonic is obscure. The harmony at m. 94 is central: the G# in the bass, the inflected fifth degree of an augmented triad, is sustained, enharmonically recast, made the root of a triad on A♭ (major, then minor), returned finally to G#, now as the third degree of a triad on E, it, too, inflected as an augmented triad.

What happens next is not immediately intelligible. The bass finds B♮. Augmented sixths establish it as a dominant of significance, the goal of these thirty bars of incessant motion. As it is scripted for the pianist, the arrival at m. 106 will sound perilous, if not catastrophic. At the end of m. 105, the left hand is caught in a difficult trill on A# high in the treble. Its Nachschlag is made to resolve to an octave B four and five octaves below. This Luftpause written into the attack before the downbeat of m. 106 sets the music off on a new trajectory. E major is tonicized but does not sound. The bass descends to a dominant truer to the larger tonality, but it, too, is ambiguous. A hint of the opening motive sounds above a muffled dominant on F. The reprise is prepared, but apparently in the subdominant. The music breaks off altogether.

Why it does so allows no simple explanation. The difficult enharmonic knot of these six bars that negotiate between the attack on B♮ at m. 106 and the arrival at F at m. 112 is embedded in a display of fantasy-like figuration. The liquidation of a sense of E major begins directly with the descent of the bass to A#, beneath a six-four arpeggiation that suggests a motion toward D#, minor. Instead, the bass continues to descend, now to A♭ and here precisely is the enharmonic short-circuit that returns us to the pungent harmonies around mm. 94–101, where G# undergoes transformation to A♭ and is then restored. The harmony at m. 109 sounds a bit odd—something of a passing harmony that allows for the sounding of the augmented sixth above G♭ at m. 110. For all its resonance with tonal relationships earlier in the movement, in the passage between mm. 106 and 112 an opposition is firmly set between two dominants a tritone apart. The one implicates a tonic on E—a remote “countertonic” a semitone beneath F minor. The other fixes F. When, however, F is struck at m. 112, its function is unequivocally as dominant. Allowed to dissipate, this is no longer the powerful dominant before the recapitulation. In these quiet final measures of the fragment, we are witness to some strange meditation in which a dominant, courting a recapitulation in the subdominant, seems willed into the tonic.19

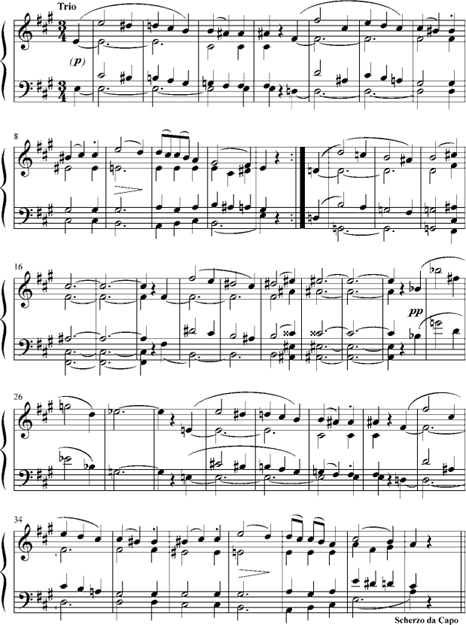

By the lights of what is apparently the most trustworthy of the surviving copies, the iterated E-major triads with which the Scherzo opens would have been the very next music that Schubert composed for this sonata. In the context of the harmonic crisis of strange dominants around m. 106 of the first movement, where E major is proposed as countertonic, the key of the Scherzo rings true. At the crossing of the first double bar in the Scherzo (at m. 49), the music moves from an octave B (established as the key of the dominant) to an octave C, initiating a placid stretch of music in the key of F major (see appendix 13F). The polarity of tonic/countertonic is reversed. The pull of the reversal is especially resonant in the twelve bars (mm. 75–86) that move from the dominant on C back to the dominant on B. This is nettlesome, caustic music. Schubert does not here avail himself of the deft single stroke wherein the dominant on C would become the augmented sixth to a dominant on B. It is obfuscation that he wants.

The return in the Trio is yet more riddling (see appendix 13G). A four-bar phrase, appearing to truncate its six-bar antecedents, outlines a first-inversion triad whose root is E♭ (heard as D#), its utter simplicity in extreme contrast to much else in this sonata. It simply fails to connect with the return of the opening phrase, on the dominant of A major. Marked pianissimo, the phrase is written at the margins of intelligibility: inaudible, not quite heard.

We return again to the first movement, to the place where writing stops. The completion of a scherzo and trio of bold originality, and of a swift finale as tightly conceived as any from these years (entirely complete in concept, if only in its Hauptstimme for mm. 201–270), returns us again to this enigma. Why does the writing stop here? The moment is a familiar one, common to other Schubert fragments, and to Oster’s visionary Mozart fragment. This is the moment that defines sonata. It is the moment in the first movement of the Eroica Symphony at which Beethoven’s horns are made to personify the dead certainty of a return too long delayed. The manifold ways in which Beethoven contends with this defining moment, even through the last quartets, yet hold this view of the thing in common.

One senses this as well in Forkel’s innocent way of getting at the analogous moment in Emanuel Bach’s Sonata in F minor, that difficult passage before the recapitulation, discussed in chapter 1 (and shown in ex. 1.1). Forkel here takes up the challenge to elucidate a work that had, even then, come to signify Work as Problem, in need of exegesis. If Forkel’s defense of Bach seems vaguely circular, I think that he is yet groping toward something profound, in his awareness of the peril in hearing such a passage “quite apart from its connection to the whole,” and further, in his sense that such “difficult modulations” might have something to do with the meaning of the work: that they are true to the character of the work, not aberrations to be explained away, tamed, revised.

These two passages, Bach’s and Schubert’s, for all their differences (and uncanny similarities) describe a common moment of crisis. Bach reaches (as will Beethoven forty years later) toward the edge of tonal intelligibility that will define the sonata in 1763 and beyond. Schubert, too, makes that reach. But the distance of remote tonal environment, construed in a classical temperament as dissonance to be resolved, is now cultivated in and of itself, in retreat from the intimidating certainties that drive much of Beethoven’s music that Schubert will have known during these formative years. This, it seems to me, is the aesthetic crisis upon which Schubert’s fragment falters.

It cannot simply be a question whether the moment of recapitulation ought to be established in the tonic or the subdominant—though indecision on this matter is evident in the sonatas, complete and incomplete, from 1817 and 1818. Such indecision is only a symptom of some deeper anxiety about return. Return itself, no longer the signifier of resolution, and the tonic as an emblem of return, is freshly problematized—and problematized again, from a richer perspective, in two works composed seven years later, in the spring of 1825. This is the business of the next chapter.

In its prizing of the remote tonal outpost, in a palpable reluctance to return home—in the Trio, that spectral phrase in E♭, isolated and abandoned before the reprise—Schubert’s music enacts a Schlegelian script. Its pull toward fragment in this romanticized sense overwhelms the classical frame within which it is conceived. The frame splinters. A fragment remains. Unlike those neatly preserved relics of broken syntax that Mozart seemed unwilling to repair, this fragment evokes the romance of timeless ruin foretold in Schlegel’s disquieting poetics.

APPENDIX 13A Mozart, Quartet Movement in G minor (fragment), K 587a (= Anh. 74)

APPENDIX 13B Mozart, Fantasie for Keyboard (fragment) in F minor, K 383C (= Anh. 32)

APPENDIX 13C Mozart, Sonata Movement in C minor (fragment), K 385f (= 396).

APPENDIX 13D Mozart, Menuetto for Keyboard, K 576b (= 355) … with recapitulation rewritten

APPENDIX 13E Schubert, Sonata in F minor, D 625, first movement

APPENDIX 13F Schubert, Sonata in F minor, Scherzo, mm. 37 to end

APPENDIX 13G Schubert, Sonata in F minor, Trio, complete