In his radically dialectical “Beethoven’s Late Style,” Theodor W. Adorno corrects what he perceived as the commonplace view of the late works as so many documents in verification of Beethoven’s biography—documents, he meant, to an intense subjectivity: “the late work, exiled to the margins of art, approaches the condition of document.”1 Adorno invites us to consider the limits, the “Grenzlinie,” of such an approach, “beyond which each of Beethoven’s conversation books would signify more than the Quartet in C-sharp minor.”2 For Adorno, only a “technical analysis” of the music itself can move toward a revision of this view. He is led at once to the problem of convention—or, as he puts it, to “the role of conventions,” in all their particularity—noting the frequency with which the music of Beethoven’s last decade draws upon the trappings of classical convention: the trill, the cadenza, the aria (with all its appurtenances), the sixteenth-note figure of the kind that accompanies the principal theme in the first movement of Opus 110, and so forth. This, it seems to me, implicates by extension genre itself, in all its particularity, as in effect a kind of superspecies of convention: sonata, fugue, variation, motet, dance, song, cavatina, and the rest. “No explanation of Beethoven’s late style,” continues Adorno, “—indeed, of any late style—is sufficient that construes the ruins of convention in purely psychological terms, indifferent to appearances.” Which leads to this insight: “The relationship of conventions to subjectivity itself must be understood as the formal principle from which springs the content of the late works, if they are to signify truly more than sentimental relics.”3

The dialectics of this uneasy relationship are examined in some final paragraphs that are as renowned for the profundity of their insight as they are for those qualities that Edward Said, writing of Adorno’s Notes to Literature, described as “eccentric, brilliant, unreadably readable, aphoristic and gnomic in the extreme.”4 Speaking of the fragmented surface that characterizes much of Beethoven’s late music, Adorno now invokes “Prozess.” The passage needs to be quoted at length:

Process remains in his late work; not, however, as development, but as kindling between extremes in the strictest technical sense. It is subjectivity which forces together these extremes in an instant, which summons the terse polyphony with its tensions, dispersed in the unison and thence dissipated, leaving behind the bare tone. The flourish sets in as memorial to the past, wherein petrified subjectivity itself decays. But the caesuras, the sudden breaking off that, more than anything else, signifies late Beethoven, are those moments of escape. The work is silent, as though it were abandoned, and turns its hollowness outward. Only then is the next fragment joined to it, the outbreak of subjectivity banned, by command, from its place, and for better or worse renounced.

And all this “illuminates the paradox that the final Beethoven is at once subjective and objective. Objective is the fragmented landscape, subjective, the light that alone glows within it.”5

The subjective, in Adorno’s reading, is constrained—its outbreak as expression (but not its essence) is renounced. The power of process lies here, in this constrained subjectivity, and perhaps it is this internalization of the subjective, this impalpable inner light that Adorno believed himself to witness, that does indeed capture something essential in the music of Beethoven’s last works.

Seeking answers to the question “What is a Late Work?” Carl Dahlhaus comes at this object/subject opposition as though in dialogue with Adorno, invoking, as he does, a “dialectical antithesis of subject and object,” an antithesis which “appears to be resolved in a classic work, but in a late work is a vigorous source of dichotomies.”6 Dahlhaus wishes to understand these antinomies as held, in the late works, in a state of suspension: “the subjective element is no longer ‘subsumed’ in the objective, and the objective element … no longer ‘justified’ by the subjective—it is no longer the case that either is transformed into the other, but, rather, that they directly confront each other.”7 Dahlhaus hears this confrontation played out in the fugal exposition in the first movement of the Quartet in C# minor. Noting that the fugue is directed to be played “molto espressivo,” Dahlhaus pits the “schematic and objective facet” (by which he means the mechanics of the exposition and the fixity of the subject and answer) against “an affective and subjective one. The counterpoints of the exposition are not independent voices, each with its own identity, but patchworks of motives that serve no other purpose than to accentuate the expressive quality of the chromatic theme… . Thus fugal mechanism and motivic expressivity are not sublimated in a ‘style d’une teneur’ but left to confront each other as discrete attributes.”8

The positing of these two “discrete attributes” as emblematic of the late style is a bold and challenging notion, even if it is not quite the dialectical condition that Adorno had in mind. To imagine that one could (in any music) identify the actual notes that stand for or indeed embody the subject, as distinct from those that constitute the object—that some notes belong to the formal dimension, others to the expressive—would seem a futile undertaking. And it is now worth asking whether the subjective—or, for that matter, subjectivity itself—need necessarily be linked to the “expressive.” In the asking, we are then led to ponder an opposition that has always seemed irrefutably real. The opposition subjective/objective we routinely accept as a condition of artistic experience. But perhaps it is closer to the experience of the thing to suggest that such an opposition is rather a permanent state of mind—in whose mind, precisely, is a problem of another dimension—wherein some shadowy subject written into the work and its performance (in first person, so to say), beats against the objectivity—the object-ness—of the work in all its abstract complexity as structure. To put it more concretely, the tema of this fugue in C# minor, in the exacting certitude of its twelve notes, is at once object and subject, and the playing out of this opposition is the considerable challenge of contemplation, of analysis, of performance. When Beethoven writes “molto espressivo,” the player (real or imaginary) is instructed to get under the skin of the music, to assume the role of the subject as theatrical protagonist, one might say, and therefore to blur the distinction between the material content of the piece and its performance, its expression. Surely, this instruction is not aimed at the counterpoints alone. To imagine a performance in which the tema is construed as object to the expressive, subjective business of the counterpoints is to attribute to these qualities a separability, a clarity that they do not possess. “Style d’une teneur”—Adagio ma non troppo e molto espressivo is the actual marking—seems precisely to capture the quality of this fugue.

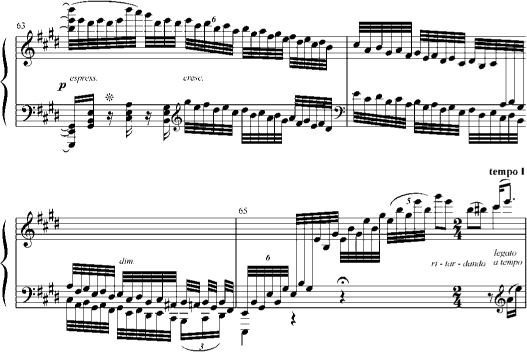

An adagio espressivo of another kind, the much celebrated disruption at bar 9 of the first movement (Vivace) of the Piano Sonata in E major, Opus 109, has in cited endless theorizing about the extents and limits of sonata form. (The music is shown in appendix 11A.) Everyone who writes about the piece reminds us, as if revealing some arcane secret, that this Adagio, when it first happens, is coordinate with the second tonal phase of a sonata exposition. The pianist Edwin Fischer writes of a movement conceived in “reiner Sonatenform”—pure sonata form–in which “the Adagio espressivo is the second theme.”9 Nicolas Marston, in his exhaustive monograph on the sonata, and in an earlier essay, speaks of this music as “the second group” in the exposition, invoking terminology minted by Donald Francis Tovey a century ago to account for the thematic vicissitudes encountered within sonata-form expositions beginning with Haydn and ending somewhere in the vicinity of Brahms.10 It is not, however, a term that has much purchase in the first movement of Opus 109. William Kinderman, in several illuminating studies, but most pointedly in an essay called “Thematic contrast and parenthetical enclosure in the piano sonatas, op. 109 and 111,” hears this music differently: “In a sense … the entire Adagio represents an interpolation, or internal expansion of the music at the moment of the interrupted cadence. Even though the adagio section is much longer than the opening segment of the Vivace, it is parenthetical, and is strictly enclosed within the first two passages in Vivace tempo.”11 If there is any vision in this extreme view, it comes at a price, for it is otherwise blind to the substantive weight of the Adagio as idea itself, and oblivious of a larger rhythmic motion in which these opening bars of the movement are made to seem an extended upbeat to the great downbeat on the diminished seventh chord at m. 9.

These efforts to understand the relationship of the Adagio espressivo to the Vivace betoken a deeply problematic aspect of the piece. Surely, the first movement of Opus 109 is radical in its rethinking of the concept Sonata—not merely of the conventions comprised in what we today loosely call sonata form, but of the genre itself. “The first movement is more like a free fantasy, and yet the quite original figure in the Vivace and the principal idea of the soulful Adagio are richly bodied forth in tightly bound alternation,” wrote its earliest reviewer (in 1821), groping for language to convey the paradox of a music that, in the alternation of its disparate parts, strives to free itself, fantasy-like, from the formal constraints of sonata even as it pulls the sonata strings more tightly.12 The estimable A. B. Marx, writing in 1824, hardly knew what to make of the first movement. He could find in it “no leading idea,” which, he surmised, “the sublime singer must have dispersed through Spiel.” Emphasizing the composer’s whimsical “play,” Marx here plays on the word itself, in its opposition to the immediacy of song, to the clarity with which a leading idea, when it is perceived as song, is made comprehensible.13 For Marx, the true sonata begins only with the second movement: “But now the true sentiment of the piece rushes forth. A highly charged passion flows with great clarity from a Prestissimo in E minor… . Written in sonata form, it (together with the last movement) constitutes the true sonata.”14 That the first movement would be heard as a music before the main business of the sonata is manifest in Marx’s language: “präludierend” (preludizing), he writes of the opening bars, and “Präludien-Form” at the end, no doubt provoked by the join between the first two movements, ensured by Beethoven’s instruction to release the final damper pedal only at the opening of the following Prestissimo.15

Carl Czerny, writing in 1842, but drawing on a life in Beethoven’s company, echoes the language of that earliest review: “More fantasy than sonata. The Vivace alternates several times with the Adagio. The whole has an extremely noble, calm but dreamy character, and the quick passages in the Adagio must be played very gently, like the figures in a dream, while the Vivace produces its effect only when played molto legato and in a singing manner.”16 Of interest, this is, not least because one might intuitively have put it the other way round: the Vivace “sehr leicht, wie Traumgestalten,” the Adagio “sehr legato und gesangvoll.” Fischer puts it this way: “The whole must sound as though it is poured out, like an improvisation,” and of the Adagio, “Everything is melody, no passage-work.”17

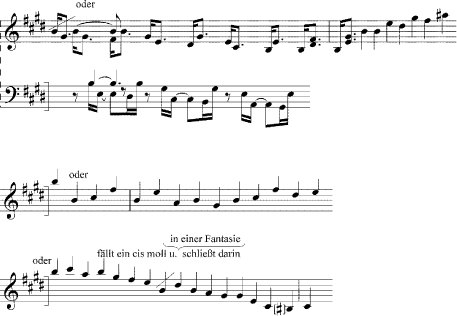

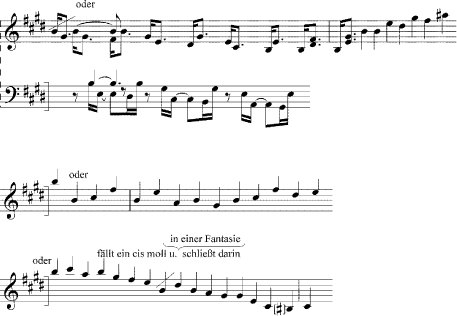

These hearings of the improvisatory, of the fantasy-like, and indeed of Marx’s “präludierend” all resonate with what may be the earliest written sketch for the movement, in the miscellaneous collection known as Berlin Grasnick 20b. The sketch is shown in ex. 11.1. Now, while the actual notes on the page are anything but clear—transcriptions by Marston and Kinderman convey two somewhat different readings—Beethoven’s conceptual inscription is highly suggestive: “fällt ein cis moll u.—in einer Fantasie—schließt darin.”18 Each of these terms—“fällt ein”; “cis moll”; “in einer Fantasie”; “schließt darin”—has some bearing on what actually happens in the movement, in its final form. The implications of these words will haunt much of the discussion that follows, even recognizing, as we must, the considerable evidentiary restraints in attributing to the finished work ideas that have survived from some earlier phase of its conception.19

“Fällt ein”—Einfall, in its sense both of sudden, involuntary idea, and of interruption–seems perfectly to capture the function, the meaning, the performative act of this diminished seventh chord at m. 9, the forte toward which the Vivace aims its long crescendo. Portentous signals of its significance are everywhere, even in its notation. No facile breaking of the chord in the usual shorthand, the arpeggiation is fully notated—made figural, a diminished seventh of thematic substance. The orthography, the graphic expanse of the thing, comes vividly to life in Beethoven’s autograph (see fig. 11.1). In another review from 1824, an astute hearing from the irreproachable Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung in Leipzig, it is precisely this Einfall that is underscored. The movement is heard to break down into two big “chunks” (Hauptmassen), and the great moment is depicted in a carefully wrought sentence designed to capture the power of the unexpected: “Following a passage across eight bars of one and the same arpeggiation in a quite natural sequence of harmonies about to arrive at a cadence in the dominant, the diminished seventh chord on B-sharp abruptly interrupts this progression and sweeps the listener away with it in an entirely new direction in the Adagio espressivo in 3/4 time that follows at once.”20

EXAMPLE 11.1 Berlin, SBB, Grasnick 20b, fol. 3r.

Adorno has something to say about the diminished seventh chord in late Beethoven. In one of those passages from his notebooks that were collected up in Beethoven: Philosophie der Musik, Adorno reminds himself of a curious pronouncement attributed to Beethoven: “Dear boy, the surprising effects which many attribute to the natural genius of the composer alone are often enough achieved quite simply by the correct use and resolution of the diminished seventh chord.”21 Adorno cites Bekker, but the actual passage comes from Theodor von Frimmel, who conducted an interview in 1880 with Carl Friedrich Hirsch, a grandson of Johann Georg Albrechtsberger, who was of course Beethoven’s counterpoint teacher from January 1794 till March 1795. Hirsch, then seventy-nine years old, recalled for Frimmel his own studies with Beethoven, which began in the autumn of 1816 and ended in May 1817.22

FIGURE 11.1 Beethoven, Piano Sonata in E major, Opus 109, first movement, from the autograph score in the Gertrude Clarke Whittall Foundation Collection held at the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. By kind permission.

Quite apart from the obvious questions of veracity elicited in these lines that Hirsch, through Frimmel, attributed to Beethoven some sixty-three years earlier, it is Adorno’s gloss on the passage that is interesting. “This statement is very important for Beethoven’s procedure,” he claims, and then: “The recurrent, idiosyncratic harmonic formulae which intentionally suspend the surface clarity include, in particular, the chord of the diminished seventh on the anticipated resolving note in the bass.”23 But the diminished seventh at m. 9 is not quite of this kind, because while the bass note toward which the previous F# wants to resolve is indeed B, this note is itself not contained within the diminished seventh. Rather, the chord fleetingly suggests that B ought to be understood in the bass, but as a root made dissonant by the ninth (B#, heard rather as C♮) sounding above it. That hearing is however contradicted at once, for the actual bass, F#, sounded at the second eighth, asserts itself as a dissonant seventh beneath an understood G#, now implicitly the root of this harmony. The inflection is toward C# minor—“fällt ein … cis moll”—not, to be sure, established as a “new key,” but merely as a station toward the tonicization of B major.

Even assuming that Hirsch’s memory, reaching back across those sixty-three years, was an exceptionally reliable instrument, it seems odd that Adorno would leap to the conclusion that Beethoven’s words should be taken at face value.24 When Beethoven uses the diminished seventh chord, he does so not merely to achieve an “überraschenden Wirkung.” Rather, it is the “richtige Anwendung und Auflösung” that must have engaged Beethoven’s explanation to Hirsch that day in 1817. And it is precisely this aspect of the thing—the “use” to which it is put, and the disentangling of its ambiguities—that endows the diminished seventh at m. 9 with its special significance. On the face of it, the articulation at m. 9, marked by a change in tempo and meter, and by every other parameter by which we measure things (density of texture, registral disposition, thematic matter and the like) is extreme. And yet the great paradox of m. 9 is that this very act of disruption, in its simple syntax, constitutes a juncture in the course of narrative, as though a sentence had been interrupted in the midst of a thought now deflected in some other direction, very much in the manner suggested by that smart reviewer for the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung. The arpeggiation unfolds at precisely this moment of deflection, and “belongs” as much to the music that precedes it as to the music that issues from it. The theater of classical sonata, its personaggi clearly defined, their entrances choreographed, is here replaced by something else: an internal colloquy, a narrative, by which I mean the act of narrating as distinct from a story told—“ohne Erzähltes erzähle,” to borrow again from Adorno25—less an enactment of some theatrical script than a journey of the mind, of the empfind-same Leben. The figure of Emanuel Bach stirs yet again. To put it differently, when we seek to explain the opposition between Vivace and Adagio espressivo, we are driven to an internal dialectics. And yet it seems to me unhelpful to insist that the Vivace is the thesis in opposition to the antithesis of the Adagio espressivo. Something more radical is at play here: this fantasy-like music that emanates from the diminished seventh chord is richly, broodingly complex, given to stunning outbursts of expression that range over the entire keyboard, as though breaching the tight constraints within which the Vivace is controlled. The distinction of the diminished seventh resides not, as is much claimed for it, in the ease with which it can be manipulated to remote ends, but in the complex enharmonic labyrinth that it often engenders.

And that is precisely what happens at the return of the diminished seventh chord at m. 12, setting loose a varied reprise—a Veränderung in the most radical sense—of the initial three-bar phrase in the Adagio espressivo: “a sequence of measures that is from all sides and in every respect sorely misunderstood,” in Schenker’s blunt prelude to his own convoluted explication.26 These are the tenths between mm. 12 and 13 that come to rest on a D# major triad. The similarity in affect with a passage in the first movement of Opus 110, mm. 77–78—indeed, almost the literal pitches (see ex. 11.2)—is striking, and perhaps draws us into some deeper aspect of Beethoven’s inner language. The sidestepping of normal root motion, a moment of syntactical inscrutability, might put us again in mind of Emanuel Bach on ellipsis, in explanation of just such a passage in the Fantasy published at the end of the Versuch.27 To explain away the passage in purely contrapuntal terms, as a motion in tenths, is to dismiss its elliptical bending of the “richtige Anwendung und Auflösung” of the diminished seventh. Surely, Beethoven wants us to hear the F-double-sharp in m. 13 as an allusion to the appoggiatura in m. 10, now given a fullness of harmonic weight.

Allusiveness alone, however, fails to account for the slippage felt at just this moment, as though the harmonic underpinnings of the passage had inexplicably shifted. In the diminished seventh that sets off the Adagio, the high A is an appoggiatura to a displaced G#, the powerfully implicit root of a dominant ninth; the F# in the bass is a seventh that resolves inevitably to E. At its repetition at m. 12, the diminished seventh is intensified, the seventh now doubled and sustained, and set in the lowest octave, the A doubled at the highest, isolating these two foundational dissonances. At m. 12, by the rule of veränderte Reprise, the ear wants the figure shown in ex. 11.3.

What it gets instead are those riddling tenths that pick up the registral isolation of the deep F# and the high A and move them across the grain, so to say, forsaking the original harmonic syntax in favor of something else. It is the F# that is made now to function as the appoggiatura-like ninth, moving to a root E#, whereas the A (to be imagined as G##) is redefined as a third degree of the new triad. It is only in retrospect (a split-second retrospect, as it turns out) that the ear must rethink the original diminished seventh, whose resolution is now made deeply problematic. The fleeting tenths at the end of m. 12 are made to bear the considerable weight of this syntactical Veränderung. Oblivious of those internal laws that control proper root motion, these extreme tenths that negotiate between mm. 12 and 13 retreat into the abstraction of voice leading, challenging us to hear into the interstices of the ellipsis, into that imaginary silence toward which the diminished seventh makes its crescendo, breaking off at, or just before, the sudden piano at E#/G#. Precisely here, in this imaginary space, something happens. The tenths are uncanny because they proceed as though nothing had happened, but are enabled only because the diminished seventh has been silently altered at its root. (Aware that Beethoven’s notation means precisely what it says, I’ve yet taken the liberty to notate ex. 11.4 in flats for the visual clarity of the harmony.)

EXAMPLE 11.2 Opus 110, first movement, mm. 76–79.

EXAMPLE 11.3 Opus 109, first movement, mm. 12–13, in hypothetical rewriting.

EXAMPLE 11.4 Opus 109, first movement, 12–14, showing root motion

At the recapitulation of the Adagio at m. 58, it is precisely the repetition analogous to mm. 12 and 13 that interrogates the moment of slippage. In the transposition of F## to the lower fifth, the anticipated B# is replaced with its enharmonic equivalent: C♮, now not the third degree of a triad, but its root—and all of this enabled because at its repetition, the diminished seventh chord is made to resolve differently (see ex. 11.5).

The challenged relationship between the Vivace and the Adagio espressivo, as two components of a sonata exposition that seem contradictory at their core, where one seems a commentary on the other, recalls once again that remarkable moment in the second movement of the fourth sonata of Emanuel Bach’s Probestücke (studied in chapter 5) where, in the midst of a solemn Largo maestoso in D major, an exaggerated exercise in the French manner, the music settles unexpectedly on C#, a dominant, isolated in three octaves with great flourish, triggering a cadenza, an intimate dialogue a due, deeply felt—and in F# minor, where the movement closes, as though in unabashed contempt of the music that precedes it. The absolute transformation of the piece at a synapse of intense concentration brings to mind Beethoven’s “fällt in cis-moll ein u.—in einer Fantasie—schließt darin,” and the diminished seventh chord that would set it off. “Fällt in fis-moll ein, u.—in einer Cadenz—schließt darin,” Bach may well have been thinking. The sense of interruption in F# minor, the closing there in a cadenza, the harmonic quiver that sets it off—all this is suggestive of what will happen in Opus 109. And if there can be no disputing the deep improvisatory impulse immanent in both cadenza and fantasy in the late eighteenth century, we might wish to remind ourselves that both of these extreme passages are to be found in the midst of sonata movements. In each, the formal constraints, the trappings, of genre are contested, and we are left to wonder whether it is the composer himself who intrudes into the text—a subjectivity in its purest sense—or whether we are witness to the scripting of a masked, figural subjectivity. Perhaps the distinction is itself without merit, the latter merely a disguise for the former.

EXAMPLE 11.5 Opus 109, first movement, mm. 61–61, as if transposed from mm. 12–13.

I cite this earlier example not, emphatically, to enter a brief for influence, however manifest in any of those other acts that specify how composers engage in dialogue with their ancestors, but only to suggest a sense of historical, of aesthetic consciousness, of a touching of musical sensibilities of the kind proposed of Opus 90 in the previous chapter. To hear Opus 109 as a work that embodies its own historical context, reaching into its well of memory as a conscious escape from contemporary convention, is, I think, to apprehend something of the paradox of past and future that so often seems to nourish the formulation—the conceptualizing—of idea in Beethoven’s late music.

Dahlhaus, I suspect, was hearing something rather similar when, in his probing study of Opus 109, he alludes to Schering’s classic study of Emanuel Bach: “That the ‘redende Prinzip’ is manifest in the Adagio espressivo, in which the cantabile and the declamatory penetrate one another, is unmistakable.”28 He continues: “The cantabile or speech-like character of the thematic material in Opus 109 … indeed poses a threat to the formal coherence of function that, following the criteria of middle-period [Beethoven] in general, legitimates sonata as such in the first place.” And then, most provocatively: “it remains … for the time being undecided whether it is a question of a movement in sonata-form or of a formulation that will have to be assessed according to some criterion other than the stringency of thematic process.”29 The music beginning at m. 9 is less “second group” than a meditation on the idea of a second group.

How, then, do we reconcile these extreme views of the movement? For Kinder-man and Marston, it is a question of hearing beyond the extravagance of the Adagio espressivo, reductively: what remains are the archetypes of voice-leading and formal convention, the tautology of tonal form. In pursuit of unities, Schenker plays the organicist card: “Beethoven strives to give the internal basis of sonata form its visible embodiment at once in an externally continuous representation of its content, which is to say that he wished the movement to be understood even in its purely external form as a normally unfolding sonata form, according to its nature.”30 For Dahlhaus, it is this unexplained extravagance of the Adagio espressivo that sets off a challenge to conventional musical coherence, a challenge to those archetypes that are the comfort zones for Schenker and his followers.

To think that they could—these disparate readings—be somehow reconciled is to suggest that diplomacy might stand in for a harder view of the thing. In his lengthy essay on Goethe’s Wahlverwandtschaften (Elective Affinities)—to which we return in the final chapter—Walter Benjamin takes Goethe’s novella as a pretext for an abstruse meditation toward a theory of literary criticism, a theory that begins with a distinction between what Benjamin calls Sachgehalt (material content) and, enigmatically, Wahrheitsgehalt (truth content). “Criticism,” he writes, “seeks the truth content of a work of art; commentary, its material content. The relationship of the two is determined by that fundamental principle of literature according to which the greater the significance of the work, the more inconspicuously and intimately its truth content is bound up with its material content.”31 What, precisely, is this Wahrheitsgehalt that Benjamin is so determined to reveal? Can it be grasped? Toward the end of the essay, Benjamin comes round to Ottilie, whose ambivalent “embodiment” figures a central enigma of the novella. For Benjamin, she inspires a quest for the location of the beautiful. “Everything essentially beautiful is always and in its essence bound up, though in infinitely different degrees, with semblance.”32 In what follows, there is tortuous introspection on the nature of beauty, in its essence, as that which is veiled; much is made of the phenomenon of veiling and unveiling, leading to this insight: “The task of art criticism is not to lift the veil but rather, through the most precise knowledge of it as a veil, to raise itself for the first time to the true view of the beautiful … to the view of the beautiful as that which is secret.” And finally: “Since only the beautiful and outside it nothing—veiling or being veiled—can be essential, the divine ground of the being of beauty lies in the secret.”33

If I understand him, Benjamin is here saying what I suspect we all grasp intuitively: to understand the beautiful, one begins with the assumption that the veil of appearance, of Schein, is not separable from some underlying Wahrheitsgehalt—some object that this veil means to obscure. In music, the inseparability of the material surface of the piece and this deeper, veiled essence may be said to constitute its beauty, an idea that perhaps drove Schenker to his own theorizing. But if Benjamin is all too aware of the futility of ever unveiling the essence of beauty, Schenker apprehends the abiding relationship of surface and deep structure differently. For Schenker, the veil must be lifted, the mystery revealed, if not solved.

Those of us who continue to ponder the mysteries of Beethoven’s late music in the crucible of postmodern discourse might consider Benjamin’s words as a provocation for a coming to terms with such enigmas as the diminished seventh chord at m. 9, and all that it suggests of the imponderable motives that underlie the two musics that mark their own worlds on either side of it. We might in this context again consider Adorno’s “Objektiv ist die brüchige Landschaft, subjektiv das Licht, darin einzig sie erglüht.” Music analysis as technical praxis may help us to find our way in this “fractured landscape.” But perhaps it is only in the act of performance (imaginary or actual) that the critical ear can sense the subjective “light” that illuminates the landscape—only the tangible, visceral, improvisatory experience of the work that brings us close to Benjamin’s intangible Wahrheitsgehalt, where the arcanum of the work is valued above all else. The prizing of the impenetrable moment of beauty, emblem of an early Romantic poetics, is manifest nowhere with such urgency as in the encounter with these late works of Beethoven, where the imaginary membrane between Sachgehalt and Wahrheitsgehalt drives the task of criticism to its extreme end.

APPENDIX 11A Beethoven, Opus 109, first movement, (a) mm. 1–15

(b) mm. 45–65