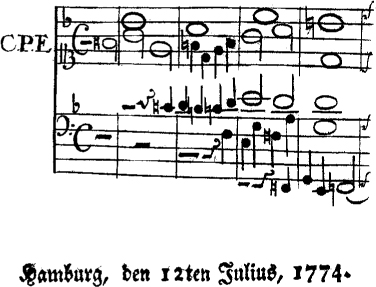

We have been taught by history to speak of Emanuel Bach as a function of, an exponent of, the great Bach. The name itself, those four sacred letters enshrined as a topos in the nineteenth century, insists that we do so. It signifies always the great Bach, and always an idealization of only a core of Bach’s music that had come to stand for some transcendental power over the notes—a technical, intellectual, and spiritual power that everyone after Bach could only admire and seek to emulate. The weaving of the sacred letters as actual tones into the fabric of some romantic homage—by Beethoven, by Liszt, by Schumann in the Six Fugues “über den Namen Bach” and Schoenberg in the Variations for Orchestra, Opus 31—is only a symptom of this mythic aspect of Bach’s preeminence. For old Bach, in his final months, these letters that encode the name of his dynasty also constitute what is arguably his last compositional act—the ultimate “theme” engraved as an emblem into the massive fragment with which the Art of Fugue breaks off. It was Emanuel Bach who seemed to testify to the act, in a note inscribed in the manuscript at just that point: “In the midst of this fugue, where the name B A C H is applied in counter-subject, the composer died.”1 “Seemed to testify” means to raise the skeptic’s flag, for Emanuel had been off in Berlin during Bach’s death, and there is now legitimate reason to suppose that this apparent quietus in the manuscript signifies something more complex. Still, Emanuel had much to do with the posthumous publication of the work, and was responsible for the sale of the copper engraving plates in 1756, a few years after the second issue.2 Perhaps this most oracular of fragments (or what Emanuel believed—or wished us to believe—to be a fragment), and its connection in Emanuel’s mind with the rite of passage which he could not witness, intrude subconsciously in a miniature homage to that final fugue that Emanuel composed in the early 1770s as a kind of signature inscribed as a memento for his friends.3 (This is shown in fig. 2.1.) It is an intense little piece, contorted in all those fugal permutations that we associate with the father, and not with the son. The legacy of the father hangs heavy over its notes, and it is only in the final dissonance, unresolved deep in the bass, that the real C. P. E. signs himself.

What can it have meant to have grown up in Bach’s home, to have had Bach both as teacher and father, and at the same time to have been conscious of one’s own claims to musical genius? Piecing together the evidence of Emanuel Bach’s life, the scholar does not at once turn to the Oedipus myth as a model for illumination into the relationship with the father. By all accounts, his attitude toward the father, and his actions on behalf of the propagation both of Bach’s music and the legacy of his teaching, were altogether beyond reproach.4 But even here, not everything is what it seems: beneath this impeccable decorum, one might imagine, is another Bach who had been more happily named anything else.

FIGURE 2.1 From Johann Friederich Reichardt, Briefe eines aufmerksamen Reisenden die Musik betreffend (Frankfurt and Breslau, 1776), II: 22.

That there might be something behind the scrim of conventional evidence to wish to investigate seems to me manifest in the facts of the case, and imperative in the very act of biography. Evidence is of many kinds. The most intriguing, the most genuine in its aura of authenticity, is that elusive type that no one knows quite how to “read” as evidence pertinent to a biography. I mean of course the music itself, the most eloquent testimony to the deepest reaches of the mind.

In the 1770s and 80s, it was Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach who was held by his critics to embody all those qualities that, for the philosophers of the Enlightenment, characterize the man of genius. The work of genius embodies, makes articulate, its own law: the creation of the superior mind gripped by some muse of which the mortal man of genius is himself only dimly conscious. Perhaps the telling definition is Immanuel Kant’s, in the Kritik der Urteilskraft (Berlin, 1790):

Genius is an aptitude to produce something for which no definite rule can be postulated; it is not a capacity or skill for something that can be learnt from some rule or other. Its prime quality, then, must be originality… . The aptitude cannot of itself describe how it creates its products, or demonstrate the process theoretically, though it provides the rules by itself being a part of nature. Thus the progenitor of a work of art is indebted to his own genius and he does not himself know how the ideas for it came to him, nor does it lie within his power to calculate them methodically or, should he so wish, to communicate them to others by means of principles that would enable others to create works of equal quality. It is through genius that nature prescribes the rules of art.5

The work of art, following its own rule, demands exegesis. This, precisely, is the task that a new criticism in the late eighteenth century set for itself: to develop an apparatus for construing such works. Here is how Carl Friedrich Cramer thought to introduce a long critical piece on a collection of keyboard sonatas, free fantasies and rondos by Bach—the fourth in the famous series “für Kenner und Liebhaber,” published in 1783.

About certain men and their works, the judgement of the “Publicum”—that kernel of connoisseurs which unites a natural sensitivity with knowledge, taste and experience—is so well established that a critic, at the appearance of a new product of his genius, has almost nothing more to do than quite simply to indicate that it exists. If this were ever the case with an artist, it is so with Bach.... One can continue to apply to him what Herr Forkel, in his excellent review of an earlier collection, with such warm and well-founded enthusiasm, borrowed from Lessing on Shakespeare: “a stamp is imprinted on the tiniest of his beauties which calls forth to the entire world: Ich bin Bachs! and woe to the alien beauty that is inclined to place itself next to him.”6

This “excellent review” by Herr Forkel, a critical account of two collections of accompanied keyboard sonatas—piano trios, we now call them—is in fact very much more than that. It appeared in 1778, in the second volume of Forkel’s Musikalisch-kritische Bibliothek, and seeks at the outset to take the measure of Bach’s genius:

[T]hose few noble souls who still know how to value and take pleasure in true art repay [Bach] in the approval that the masses cannot give, and his irrepressible inner activity overpowers every obstacle that stands in the way of his creative outburst [Ausbruch] and communication. In this way a lively, fiery and active spirit—even in a world which, in relation to him, is hardly better than a desert—is thus in a position to bring forth works of art which carry within them every characteristic of true original genius, and, as fruits of an inner compulsion of doubled strength, are of double worth to those few noble souls who, as Luther says, understand such things a little.

We do not need to determine to what extent this is the case with the famous composer of these sonatas. Not, however, satisfied with that fame long ago established, not satisfied to have created a new taste, and through it, to have widened the musical terrain, he continues to enrich us with the fruits of his inexhaustible genius, and shows us that even in the evening of his life, his imagination is still disposed toward the conception of those noble and stimulating ideas; so that now, as in the noontime of his life, one may say of him what Lessing says of Shakespeare: …7

What Lessing had to say of Shakespeare is deeply bound up both in his theorizing about German theater and in his own writing for the stage. The passage in question comes from one of the critical pieces published altogether under the title Hamburgische Dramaturgie in 1769, and specifically from a review of Christian Felix Weiße’s Richard III, which Lessing took as a pretext to develop an essay on the nature of tragic character and on the issue of imitation and borrowing in literature and the arts.8 It is well known that Shakespeare figured prominently in the debate, some years earlier, on the purity of classical tragedy. The complexity of Lessing’s Shakespeare criticism, of his brilliant and convoluted efforts to reconcile Shakespearean tragedy with the Aristotelian principles of pure classical tragedy, and in opposition to what Lessing held to be a misreading of those principles in the tragedies of Corneille and Racine, need not obscure the intent of those lines quoted by Forkel.9 But it is in the following lines that Lessing’s sense of Shakespeare’s creative originality, as a giver of rule, is implicit.

Shakespeare must be studied, and not plundered. If we have genius, then Shakespeare must be to us what the camera obscura is to the landscape painter: he looks into it diligently to understand how Nature in all its conditions is projected upon a single surface; but he borrows nothing from it.10

The originality of Shakespeare’s work allows no imitation, a view consonant with Kant’s axiom that “it is through genius that Nature prescribes the rules of art.”

That Forkel, in writing about Emanuel Bach, should have reached for this essay is in itself significant, and not, I think, because Forkel intended to force an invidious comparison between Bach’s art and Shakespeare’s. Rather, the coupling of this eminent critical mind with the idea of Shakespeare conjured the tone that Forkel wished to set in contending with these trios by Bach, suggesting by analogy the relationship between the man of genius and his enlightened critic: Lessing to Shakespeare is as Forkel to Bach. For Forkel, it was Emanuel Bach’s music, in its inscrutable originality, that served as a touchstone for the act of criticism. This sense of Bach as law-giver comes through in the Sendschreiben (studied earlier, in chapter 1) composed in answer to some putative invitation to divulge the meaning of Bach’s Sonata in F minor from the third collection “für Kenner und Liebhaber.” Forkel, it will be recalled, turned the opportunity toward nothing less than a disquisition on the concept of sonata. There is talk here about neither thematic idea, nor modulation, nor even harmony—except in some marginal comments that clearly reside outside the main argument. For Forkel, it is only the “genuine composer of sonatas [emphasis mine] and the poet of odes” who have the capacity to unite “refined and abstract taste with fiery imagination in bringing regulation and plan in the progression of Empfindung,” a difficult enterprise that, for Forkel, has always insured that there have been “so few true and genuine composers of sonatas and poets of odes.”

The happy vanquishing of this difficulty is also why I hold the author of our Sonata in F minor for a far greater musical ode-poet than we have ever had.... How precious, then, must be the products of a man who is the only one in his art who unites everything within it that nature and taste can give to the artist, and who among the powerful lords of music stands thus alone in the heights, incomparable. No one can be set at his side, but rather (as Claudius says of Lessing) he sits on his own bench.11

Forkel was perhaps best known in the nineteenth century as the author of the first book-length biography of Sebastian Bach, published, finally, in 1802.12 His work toward that end had begun in the 1770s, and the principal source of his information, both anecdotal and documentary, both archival and in actual musical texts of unknown works, was Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. Some twenty-six letters from Bach to Forkel, dating from between 1773 and 1778—and a final one from 1786—have survived. Unwittingly, they capture a fundamental opposition in Bach’s life: on the one hand, there is a deeply held obligation to the proper dissemination of the father’s legacy, and, on the other, the selling of a new aesthetic, one born in antipathy to that legacy. Two passages will convey this double mission, the first from a letter of 7 October 1774:

In haste, dear friend, I have the satisfaction of sending you the remains of my Sebastianoren: namely, 11 trios, 3 pedal pieces, and Von Himmel Hoch etc… . The 6 keyboard trios … are among the best works of my dear, late father. They still sound very good, and bring me much satisfaction, even though they are more than 50 years old. There are a few adagios in them which even today could not have been composed in a more vocal style… . In the next letter, pure Emanueliana.13

The second, from a letter dated 10 February 1775, is three close pages of “pure Emanueliana.” The following passage is well-known, but worth retelling:

Now one would like to have 6 or 12 fantasies from me, like the 18th “Probestück” in C minor. I don’t deny that I would love to do something in this genre, and perhaps I am not entirely ungifted in this. Besides, I have a good collection of them which ... belong to the chapter on free fantasy in the second part of my Essay [on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments]. But how many people are there who love this kind of thing, who understand them, and who can play them well?14

What kind of music was Bach writing in the 1770s? We know from other letters that Bach made a distinction between music composed for the pleasure of a small circle of connoisseurs—music essentially for himself—and that which was intended for sale to a less endowed public. In the autobiographical notice written in 1773 for the German translation of Charles Burney’s travel journals, Bach admitted as much: “Because I have had to compose most of my works for specific individuals and for the public, I have always been more restrained in them than in the few pieces that I have written merely for myself… . Among all my works, especially those for clavier, only a few trios, solos and concertos were composed in complete freedom and for my own use.”15

A sonata composed in 1775, and unpublished until very recently, displays that inimitable originality that had come to be prized as a defining attribute of genius. (Two movements of the sonata are given here as appendix 2A.) It has survived in Bach’s autograph and in three contemporary copies, suggesting a wide circulation among the members of Bach’s inner circle.16

One phrase in particular captures the ear. The most overtly coherent phrase in the piece (the only coherent one, by some measure), it occurs for the first time deep in the interior of the first movement, at mm. 33–37 (first beat), after the first double bar—outside, that is, the formal exposition. The intelligibility of the phrase, the sense that it makes within itself, is only exaggerated through a context that seems intent upon syntactical dislocation. Abruptly abandoned, the phrase suggests no self-evident relation to the immediate surface of the piece. Its significance refuses explanation: reason is not likely to get at the illogical aspect of its place in the course of things, nor to fathom the phrase in its gestural aspect.

This telling phrase returns, and when it does, it engages the narrative of the piece in ways that we could not have predicted. The opening idea, recapitulated at m. 60, is now reset in A♭ major, as though in search of this outcast phrase, and, finding it—see mm. 67–71 (first beat)—draws it into the immediate tonal motion of the piece. Set in the key of the flat submediant, the phrase seems to hover placidly for an instant before the inevitable augmented sixth at the cadence.

“Das Adagio fällt gleich ein,” Bach instructs, at the end of the movement: “The Adagio begins straightaway.” It is similar in kind, this Adagio, to any number of contemplative intermezzi in Bach’s keyboard works that conjure some remote tonal landscape between the outer movements. This one begins its meditation on an isolated D♭. The tone itself, in its naked isolation, establishes a dissonance with the final cadence in the first movement, and therefore suggests a reaching back into the memory of the piece. Again, Bach’s “Das Adagio fällt gleich ein” presses the point. Even the disposition of its first harmony is calculated to suggest a Neapolitan sixth in relation to the first movement.

The Adagio, too, has its luminous, telling phrase, and it flowers at just the point where the music begins its descent through the circle of fifths that winds inexorably from D♭ to the half-cadence in C before the final movement. It is precisely at this moment of greatest remove (beginning at m. 10) that a phrase redolent of that expatriate phrase in the first movement is teased out of the narrative. The reciprocity between these moments is not casual, nor is it concrete in the manner of some thematic permutation. Rather, one gropes for the language to convey how they are related: for it is an evocative relationship of just this kind, with all that it suggests of the significatory power of an ambiguous phrase, that cries out for this new mode of criticism that Forkel and his contemporaries were struggling to develop.

On the clavichord, the inclination of those opening D♭s toward some linguistic expression, however dimly felt, is palpable. On any other instrument, this eloquence is missed.17 The harpsichord, innately antipathetic to such music, would trample on the nuances of what has been called its “redende” aspect—music as speech. Because the tangent remains in contact with the string, and establishes one node in the sounding structure, the finger controls the vibrating string as it can at no other keyboard instrument. Like no other keyboard instrument, the clavichord “speaks.” And it is further in the nature of the instrument that it speaks directly to the player, and (because one must strain to hear it in all its nuance) only faintly to everyone else. It is the clavichord into which Emanuel Bach withdraws, into its world of near silence, where each tone is an Empfindung—expression itself—whose inaudibility only exaggerates its claim to speech. There is no grand splendor in music of this kind, but only a touching of sensibilities.

Less than a year before his own death, in a remarkable review of the first volume of Forkel’s Geschichte der Musik, Bach affords us a rare insight into his understanding of the nature of musical expression: “Music has long been called a language of feeling, and consequently, the similarities that lie beneath the coherence of its expression and the expression of spoken language have been deeply felt.”18 This “Sprache der Empfindung” (to revive a topic addressed in chapter 1 and anticipate its discussion in chapter 6), and its darkly felt associations with linguistic expression, is at the core of Bach’s aesthetic. To hear this music, we need to “feel” with it, to engage in what Herder would famously call Einfühlung.19 The Empfindungen somehow conveyed through the syntaxes of this language do not open themselves up to conventional analysis. To seek to explain such music in rational, equation-like syllogism as so many permutations of a Grundgestalt, is to miss its point. Analysis of this kind may tell us something about certain aspects of the surface of the music, but it tells us nothing of the essential inner core of it. It is Bach’s “dunkel gefühlt” that is suggestive of the critical process that will get us to the essence of the piece.

How might we construe the language of a sonata such as this as testimony of a man whose only teacher, as he himself reverently claimed on more than one occasion, was his father? Where is the patrimony in the sonata? What heritage is this, in which all the old orthodoxies are repudiated? The clichés of music history are not helpful. It will not do to speak of “style change” as though it were some inexorable historical event to which Emanuel Bach’s music necessarily contributes. Bach’s music sounds like no one else’s. It is radical and idiosyncratic beyond anything in the music of even his closest contemporaries. Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, however loudly their proclamation of Emanuel Bach as a spiritual father—and there is no reason to doubt them—hardly knew what to make of it. Charles Burney, who spent a good week with Emanuel Bach in 1772, and wrote about it in his travel journals, published the following year, recaptured the special quality of Bach’s language in a vivid passage in the fourth volume (1789) of his General History: “Emanuel Bach used to be censured for his extraneous modulations, crudities, and difficulties; but, like the hard words of Dr. Johnson, to which the public by degrees became reconciled, every German composer takes the same liberties now as Bach, and every English writer uses Johnson’s language with impunity.”20

It would be fatuous to suggest that Emanuel Bach’s music could have existed without the obscure patrimony to which I referred a moment ago. The figure of Sebastian Bach, totemlike, was ubiquitous. Everywhere, Emanuel felt the need to speak of his father. In his music, he fails to do so. The patrimony is not acknowledged there. And when he speaks about the father’s music, it is the astounding technique that is admired, the awesome, powerful control of musical forces—qualities that Emanuel Bach’s music does not seek. Even in the most lavish encomium to the father’s art—the comparison with Handel, written in 1788, provoked by an essay by Burney, whose bias toward Handel was easily explained (he knew lots of Handel’s music, and very little of Sebastian Bach’s)—even here, the praise is for Bach as prestidigitator, both as an organist and as a contriver of fugal complexity.21

What I mean to suggest is that Emanuel Bach’s music tells us something about the relationship of the son to the father, in this complex language of signification, at once abstract and concrete, that is the deepest reflection of feeling. What one reads there hews closely to what one has come to know, through Freud, as an archetype for the ambivalence in the behavior of the son toward the father. A revelatory passage from the third essay in Moses and Monotheism from a chapter titled “The Great Man,” is very much to the point.

And now it begins to dawn on us that all the features with which we furnish the great man are traits of the father, that in this similarity lies the essence of the great man. The decisiveness of thought, the strength of will, the forcefulness of his deeds, belong to the picture of the father; above all other things, however, the self-reliance and independence of the great man, his divine conviction of doing the right thing, which may pass into ruthlessness. He must be admired, he may be trusted, but one cannot help but fear him as well.22

Freud imagines Moses as a “tremendous father imago” to his people. “And when they killed this great man they only repeated an evil deed which in primeval times had been a law directed against the divine king, and which, as we know, derives from a still older prototype”—a reference to totemism among aboriginal tribes.23

Freud’s own obsession with Moses is a topic to itself. The famous 1914 essay on the Moses of Michelangelo is rich in evidence for this, even in its misreadings. But it is also rich in what it suggests about the power of psychoanalytic scrutiny for the interpretation of art, for it forces us to separate out an analysis of the work, and the play of psyche within it, from an investigation of what Freud openly refers to as “the artist’s intention.” Freud’s strategy calls for no such separating out, as I think is clear from a passage early on in the Michelangelo essay. “It can only be the artist’s intention,” he writes, “in so far as he has succeeded in expressing it in his work and in conveying it to us, that grips us so powerfully.... It cannot be merely a matter of intellectual comprehension; what he aims at is to awaken in us the same emotional attitude, the same mental constellation as that which in him produced the impetus to create.”24

But the impetus to create and the text of what is created are two very different phenomena, deeply related as they may be. This impetus, which the artist may sense only vaguely, does not readily translate into the substance of the work. How to read a psychoanalytic print of the author in the text, how the text itself constitutes evidence for such a reading, is a critical enterprise of a certain legitimacy. Its converse—how a psychoanalytic reading of the author might tell us of motives in the work—cannot lay claim to similar legitimacy: the work and the life are not interchangeable, are not the terms of a simple equation. In its unhinged, neurotic, fitful acts at speech, this isolated Sonata from 1775—he did not again write a sonata for keyboard alone until 1780—tells us something of Emanuel Bach’s cast of mind, of an aesthetics born in some internalized revolt, in a playing out of a family romance, just as its inner coherence, however “darkly felt,” speaks to that power of law-giving that Forkel senses in his lengthy communication on the Sonata in F minor. That nostalgic phrase in the Adagio, for all its self-referentiality within the interiors of the piece, yet suggests something about its author. Recourse to a family romance can offer no more than the sketch of some internalized drama against which such a phrase might have been conceived. In the end, the piece must remain its own singular testimony to its meaning.

Sebastian Bach as Moses? In precisely how it has been made to signify in these past two hundred years, no repertory of music more nearly approaches the commandments engraved in those tablets that Moses holds than Bach’s. There is a temptation to extend the simile to those “hundred-weight” copper plates—the tablets on which is engraved the “Art of Fugue”—which Emanuel Bach sold off after public advertisement, six years after his father’s death.25 Kunst der Fuge: the title itself has a scriptural ring to it, some sort of cabbalah in search of the hermeneut. From a purely pragmatic point of view, Bach’s decision to rid himself of these tablets seems entirely justifiable—and it must be said that the autograph score remained in his possession. But the ambivalent undercurrent in the act, its veiled suggestion of some public renunciation, has its place in the story as well.

A word about Bach’s mother. If history tends to obliterate this aspect of the lineage, Emanuel Bach makes certain that she has her place. The opening lines of his autobiographical notice are unequivocal about that: “I, Carl Philip Emanuel Bach, was born in Weimar, March 1714. My late father was Johann Sebastian, Kapellmeister at several courts and ultimately music director in Leipzig. My mother was Maria Barbara Bach, youngest daughter of Johann Michael Bach, a solidly founded composer.”26

If we are too ready to attribute Bach’s musical gifts unconditionally to the father’s side, the son corrects us. The mother died in July 1720. Sebastian Bach, knowing nothing of this, returned from a trip to Carlsbad to discover that her body had been interred. What can it have meant to a six-year-old to have been witness to that? Perhaps it is to the point to remind ourselves that Maria Barbara and Sebastian were related before marriage. Her father and Bach’s father were first cousins. In this sense, too, the line between father’s side and mother’s side is blurred.

It was Forkel who, in the final lines of his biography of Sebastian Bach, established an hegemony of the father that necessarily set in subordination the works of his progeny—indeed, of all who were to follow. Forkel’s mantic words have an evangelical ring: “And this man, the greatest musical poet and the greatest musical orator that ever existed, and probably ever will exist, was a German. Be proud of him, fatherland! Be proud of him, but worthy of him as well!”27

There was an agenda for the nineteenth century. In effect the discovery and resurrection of Bach’s music was an obsession with its own ambivalences. The appropriation of Bach as the original Romantic—the Ur-Romantiker—by composers as disparate as Beethoven, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Wagner, Brahms, and Schoenberg coincided with a stripping away of all such extravagant excess, in the endeavor to discover and scrape clean that enormous repertory whose magnitude Forkel could only vaguely surmise. It is not an exaggeration to say that the invention of a Musikwissenschaft at mid-century, along with a scholarly apparatus that vibrates sympathetically with all those other monumental achievements of the industrial revolution, was born of this moral necessity that Forkel preached: to be worthy of Bach. The Gesamtausgabe produced by the editorial staff of the Bach Gesellschaft was an enterprise that consumed a half century, from its founding on the centennial of Bach’s death to its completion in 1899.28

In the 1770s, seeking a critical language adequate to convey Emanuel Bach’s music to his contemporaries, Forkel thought to invoke Lessing on Shakespeare, at a time when the call to write a biography of Sebastian Bach seemed driven more by historical curiosity than of a profound passion for the music. Thirty years later, this assessment of their music would be turned on its head. Along with the clavichord, Emanuel Bach’s music vanished.29 How indeed could the imperious political and aesthetic agendas of the nineteenth century find a place for this idiosyncratic, heretical music that, when it can be heard at all, speaks out so eloquently against all such monument making? Its eccentricities touch the mind and the soul, and bring us close to the human condition in a way that Bach the father would not have wished to understand.

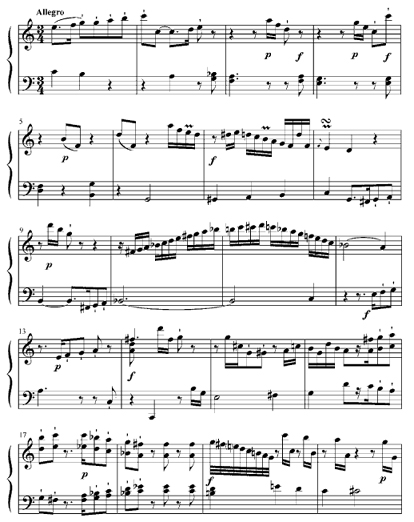

APPENDIX 2A C. P. E. Bach, Sonata per il cembalo solo, H 248 (1775), first and second movements

From Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Klaviersonaten: Auswahl, ed. Darrell M. Berg, 3 vols. (Munich: G. Henle, 1986–1989), III:88–92. Used by permission.