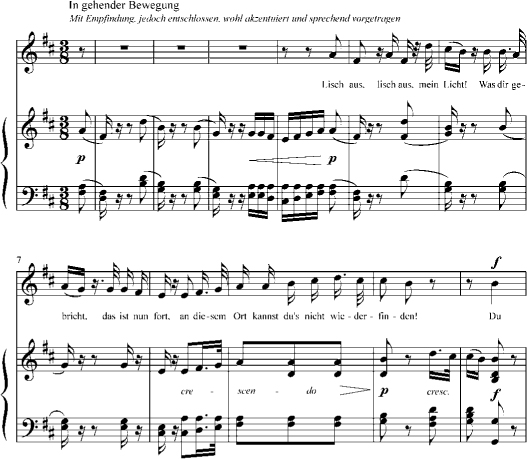

“Mit inniger Empfindung, doch entschlossen, wohl akzentuirt u. sprechend vorgetr[agen]”: with intimate feeling, yet resolutely, well accented, and sung as though spoken. Beethoven inscribed this elaborate instruction on the inside cover of a small notebook—the so-called Boldrini sketchbook—used during the autumn of 1817. Gustav Nottebohm (who described the contents of the book before it vanished shortly after 1890) observed that “inniger” seemed to have been a second thought, added a bit later.1 Beethoven then either forgot that he’d added it, or thought better of it, for the word does not appear in the published version. It did, however, appear less than a year earlier, in the inscription above the first movement of the Piano Sonata in A, Opus 101: “Etwas lebhaft und mit der innigsten Empfindung.” A similar instruction, from August 1814, regulates the opening movement of the Piano Sonata in E minor, Opus 90: “Mit Lebhaftigkeit und durchaus mit Empfindung und Ausdruck.” Its second movement is inscribed “Nicht zu geschwind und sehr singbar vorzutragen”; in similar mode, the third movement of the Piano Sonata Opus 109, from 1820, is marked “Gesangvoll, mit innigster Empfindung.”

The inscription in Boldrini pertains not, however, to some instrumental work that wants to sing, but to a song that wants to speak. Resignation (WoO 149), first published in the Wiener Zeitschrift für Kunst for 31 March 1818, is a setting of an enigmatic poem by Paul Graf von Haugwitz.2 (The poem and the song are given as appendix 12A.) Quirky and eccentric, its contradictions are mirrored in Beethoven’s fussy guide to its performance. Curiously, the poem has nothing decisive about it, in the affirmative sense conveyed in Beethoven’s “doch entschlossen.” Tinged in melancholy, Haugwitz’s diffident voice phrases a conceit of passion extinguished. If there is a lover concealed here as well, she (or he) is nowhere in evidence, except perhaps in this impalpable, passionless, odorless—yet life endowing—Luft of which the flame is deprived. Whether, then, these images mean to signify a love blown away or the creative fire gone cold—or, for that matter, the two together as complicitous in the meaningful life: this is left unsettled.

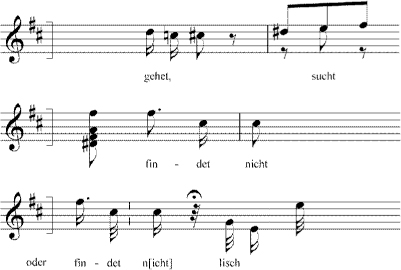

EXAMPLE 12.1 Boldrini sketchbook (after N II, 352): sketch for Resignation.

Beethoven’s setting is unsettling in other ways. By way of entry into this riddling song, the ear is drawn to the singular syntactical formulation with which Beethoven conveys Haugwitz’s second strophe: a fresh thematic diction that dissolves at “sucht—findet nicht—,” turning elliptically back to the opening imperative, “Lisch aus, mein Licht.” Exploiting the ambivalence of Haugwitz’s neat palindromic device, Beethoven builds in a full reprise of the opening quatrain. The fourth line of the quatrain—“Du musst nun los dich binden,” words redolent of the resolve and heroics of an earlier phase in Beethoven’s career—is made climactic in the recapitulation. A triumphant moment of Entschlossenheit is imposed upon Haugwitz’s wistful lyric. Poem and song are not quite about the same sentiments, nor are they formally concordant.

Beethoven evidently notated seven full pages of sketches for the song in Boldrini. Alas, the three very brief entries published by Nottebohm are all that have survived. The third of them (shown in ex. 12.1) is significant. It has a resonance in some sketches preserved in the great miscellany now in the British Library (Ms. Add. 29997), a few fleeting entries penciled at the bottom corner of a page evidently a casualty from an autograph of the cantata Der glorreiche Augenblick (see ex. 12.2).3

EXAMPLE 12.2 British Library, Ms. Add. 29997, fol. 31r: sketches for Resignation.

These gestures, taken together with that third entry among Nottebohm’s Boldrini sketches, hint at some anxiety having to do with the harmonic implications of this much worried phrase at “findet nicht.” The chromatics running up to it, at “sucht, sucht,” suggest a commonplace cadential sequel: F# wants resolution up to G, which in turn wants the support of some harmony rooted to E. How this might go is shown in ex. 12.3. Beethoven’s languid phrase—its coupling of F# with a discomfiting C#—constitutes an ellipsis that betrays the harmony powerfully implicated between a dominant seventh on B and the true dominant of return on A. All the orthodoxies that would enact this cadence are here refused.

EXAMPLE 12.3 Resignation, hypothetical continuation from m. 26.

Thanks to Nottebohm, we have a pretty good sense of the contents of Boldrini. Evidently the largest of the small-format, so-called pocket sketchbooks, it was devoted to work on the first three movements of the Hammerklavier Sonata, Opus 106, the sketches for which occupied most of pages 18 through 128. In their midst—on pages 92 through 109—would be found sketches for the first movement of the Ninth Symphony (rather advanced—“ziemlich vorgerückt”—Nottebohm calls them) and intimations, only, for the remaining movements. But the first sixteen pages of the book are given to other things. Their contents, again according to Nottebohm, are revealing:

Project |

Pages |

Quintet Fugue in D minor, Hess 40: sketches |

1, 2 and 7 |

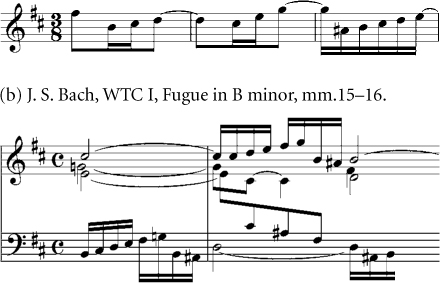

J. S. Bach. Two passages from the Fugue in B♭ minor, WTC I.4 |

4 |

Entry for setting of Matthisson’s “Badelied” |

4 |

Quintet Fugue in D major, Opus 137: last four bars in full score. |

5 |

J. S. Bach. Two passages from the Kunst der Fuge, Contrapunct. 4. |

7 |

Marpurg, Abhandlung von der Fuge, II, Tab. XVI, figs. 1-6. |

8 |

Setting of Haugwitz’s “Resignation”: late sketches |

10–16 |

Merely one instance of a consuming inquiry into fugue—the revisiting of the same icons time and again, as though for spiritual sustenance—these sketchbook entries take on a special poignancy, lodged at what seems a moment of studious contemplation before the rush of counterpoint and fugal device set loose in Opus 106.

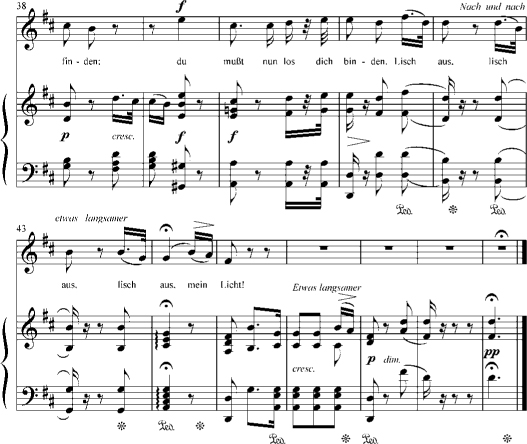

The Fugue for String Quintet, Opus 137, was composed to inaugurate the ambitious Gesamtausgabe of Beethoven’s works, in clean manuscript copy, undertaken by Tobias Haslinger in 1817.5 The single entry for it in Boldrini, its final four bars written in quintet score (Nottebohm left no transcription), again implicates sketches in another source. A leaf now bound in with the sketch miscellany Grasnick 20b, and perhaps discarded from a working autograph, again displays the final bars, here entered three times, each in full score: the final seven bars, heavily revised, are followed on a second system by the final four bars, written out twice. No other sketches for Opus 137 are known to have survived.6

For Beethoven, fugue is a concept vulnerable to dialectical extremes. It seems to have been so conceived from his earliest music straight through to the final quartets: any assessment of “late style” in Beethoven needs to come to terms with this condition.7 At the one extreme are those fugues conceived as didactic exercise, responsive to what might be called the constraints of eighteenth-century procedure and modeled on the venerable historical prototypes, as codified in such works as Marpurg’s Abhandlung von der Fuge (Berlin, 1753–1754) and Albrechtsberger’s Gründliche Anweisung zur Composition (Leipzig, 1790), both of which served as texts for Beethoven’s own lifelong study. At the other extreme are those fugues that were composed against the rules, so to speak: the genre itself reinvented in the service of some poetic, even epic mission. The fugues composed under Albrechtsberger’s eye in the mid-1790s are largely of the first kind, the idiosyncratic specimens from the late quartets of the second. Even in these extreme instances, antinomies are played out at one level or another.

Just such dialectical antinomies are audible in the sketches for these troublesome final bars of Opus 137. (A complete score is given in appendix 12B.) For while the opening bars of the fugue expound a subject and answer that hew suspiciously close to some Bach-like paradigm, the final bars probe the harmonic and even the rhythmic implications of the subject—well-concealed implications, one must say—and echo the salient moments of its subsequent elaboration.

The most salient of them comes at the center of the fugue—nearly plumb at its midpoint, at mm. 36–41. A tritone is wrenched, fortissimo, from the open-stringed C in the cello, at the acoustic bottom of the quintet, where it posits a resolution down to an abstract, unplayable B: the root of a dominant ninth theatrically staged but unsounded. Against it, violin 1 and viola 1 strain at the top of their registers. A single diminished seventh chord resonates for fully five bars. D# is forged into E♭, and the passage resolves not in E minor, but to the dominant of G major.

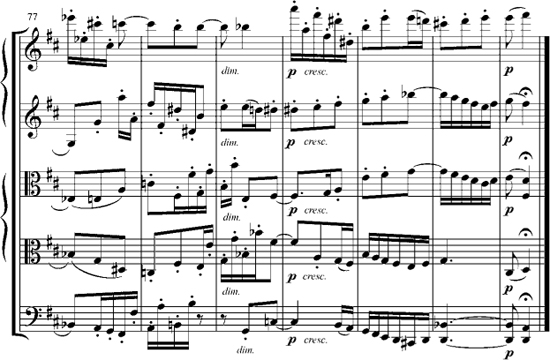

This tritone is itself embedded in the subject, but only when the music is cast in B minor, in the entry beginning at m. 30. And this returns us to those troublesome final bars. C♮ is again conspicuous, provoking a series of chromatic descents, and evoking harmonic paths earlier suggested but not taken. In the motion between bars 77 and 78, E♭ is reconverted to D# (reversing the enharmonic vector of mm. 36–42): the simultaneity at the downbeat of bar 78 offers up a tripled C—a tripled ninth!—leading to a dominant on B. D# is now so prominent as to inscribe itself into the final statement of the subject (at bar 80). The tonic triad that the subject unfolds at its outset is here transformed into an actual dissonance, its opening A now manifestly a seventh, drawn through an imaginary G to the final F# with which the subject closes. It is a harmonic implication of the subject that is realized here, having driven the fugue through even its most radical episodes. The very last note in the discant, the F# is heard finally to respond to the dissonance immanent in the very first note of the fugue.

If these opening pages in Boldrini capture the final stages of work on the fugue for Haslinger, they establish as well the evidence for a puzzling corollary: that Beethoven had now begun to work on a second quintet fugue, this one in D minor. Yet again, another source is implicated, for the fugal incipit that Nottebohm records from Boldrini—and he records nothing more than that—is precisely what is captured in an autograph manuscript containing a complete prelude in D minor with an elaborate transition to the fugue, of which again only the opening four bars are notated.8

Another brief entry for an interior passage in this incomplete D minor fugue has survived in a manuscript now at the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna. Beethoven Ms. Autogr.81 contains a transcription in rough quartet score, in Beethoven’s impatient sketch hand, of the fugue in B minor from Book I of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier. Where the fragment breaks off, after bar 32, some blank space at the bottom of the page was used for a hasty, almost illegible penciled entry for an episode from this Quintet Fugue in D minor.9 The propinquity of these two projects on a single page suggests that the transcription of the Fugue in B minor likely dates from the weeks chronicled in the opening pages of Boldrini. In its watermark, the manuscript at the Gesellschaft is very close to the type prevalent in the sketchbook Beethoven Autogr. 11, fascicle 1 (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin—Preußischer Kulturbesitz) whose paper was in use between the end of 1816 and the beginning of 1818, and for miscellaneous sketches for Opus 106.10

This same watermark has now been identified in a manuscript discovered only very recently, and containing a previously unknown Allegretto in B minor for string quartet.11 The manuscript bears an inscription in the hand of one Richard Ford: “This quartette was composed for me in my presence by Ludwig v. Beethoven at Vienna Friday 20th November 1817”—precisely the date inscribed by Beethoven on the Paris autograph of Opus 137. In its brusque twenty-three bars, the Allegretto for Ford resonates sympathetically with these other projects. (The piece is shown in its entirety as appendix 12C.) Its opening theme, an offspring (one might think) of the opening of the fugue for Haslinger, is a fugue subject without fugal issue: the ’cello answers at the octave (no hint of an answer at the dominant), but only for a measure. Still, the texture is openly contrapuntal, fuguelike in its intense pursuit of the sharply etched motives of the subject, overwrought in its picking out of tritones. The return to B minor at m. 16 is coincident with a restatement of the subject, now tripled at the octave, and with a curious leveling of its second measure, C# E G now read as E F# G.

EXAMPLE 12.4 (a) Beethoven, Quartet for Ford; and

The rare value of the piece lies in what it testifies as to Beethoven’s state of mind on that Friday in November 1817. For if Ford is accurate in his description of the circumstances of its composition, Beethoven is writing quickly and without premeditation. The autograph is uncommonly clean. A smudged out accidental in the viola at m. 9 hints at an expunged A#, suggesting an immediate return to B minor and an even shorter piece.12 If a vagrant sketch might have been found its way into the Boldrini Sketchbook, Nottebohm’s selective description of its contents would normally have nothing to say about inconsequential entries for a work that he could not have identified in any case. The manuscript prepared for Ford then documents something of a fugitive thought, free of the kinds of pressures and compulsions that weigh on major projects. The key itself is of interest. B minor, the rarest of keys in Beethoven—“h moll schwarzer Tonart,” he scribbled in a sketchbook from 181513—seems an echo of Beethoven’s engagement with the transcription of the B-minor Fugue from the Well-Tempered Clavier, with which it shares even a turn of phrase (see ex. 12.4). The internal voicings of the quintet fugue for Haslinger echo even more clearly: the Allegretto for Ford takes fugue as a manner of discourse where wit and concision, and the play of texture, frees the music from the too familiar temporalities of classical sonata, finding new accents and a new diction even as it challenges the archaic rhetoric of fugal procedure and the hegemony of the Bach fugue. The lifelong engagement with Bach the father is a profoundly dialectical exercise, one without end for Beethoven, and with profound consequences for his late music. The engagement with Emanuel, closer to home, was more fragile, and it is tempting to hear in the music of Beethoven’s final decade echoes of the family agon—once more: Bach father, Bach son—even with traces of its redemptive aspects.

By the 1770s, Bach’s B minor fugue had acquired a reputation. Its harmonies, thought to sound the arcana of an almost biblical profundity, invited exegesis. An invitation was tendered and accepted by Johann Philipp Kirnberger, who, in collaboration with Johann Abraham Peter Schulz, published an analytic display in which a fundamental bass is extrapolated from the first to the very last note of the fugue. The analysis constitutes a magisterial concluding example in Kirnberger’s Die wahren Grundsätze zum Gebrauch der Harmonie, a book that we know Beethoven to have studied while he was still in Bonn.14 “This fugue by Joh. Seb. Bach,” writes Kirnberger, “which has until today seemed unsolvable by even the great men of our time, is given here with its innate and natural fundamental harmonies, following our precepts, and may serve as a proof of everything stipulated above”—in Die wahren Grundsätze, that is. “We believe ourselves to have fathomed the nature of the thing itself when we assert that these fundamental rules of harmony are not only the true, but indeed the only ones according to which this fugue can be explained, and in general all the apparent difficulties in the other works of this greatest harmonist of all times can be elucidated and rendered comprehensible.”15 In fact, the motivation to write Die wahren Grundsätze seems to have issued from one Herr Hoffmann, organist at the principal church in Breslau. Provoked by a similar analysis in the first part of Kirnberger’s Kunst des reinen Satzes, Hoffmann allegedly challenged the theorist “to reduce to its simple Grundaccorde a certain well-known Bach fugue.”16

EXAMPLE 12.5 J. S. Bach, WTC I, Fugue in B minor, mm. 12–15.

If there is one passage in the fugue that might have quickened Herr Hoffmann’s resolve to approach Kirnberger, it would have been the entrance of the answering voice at bar 13 (shown in ex. 12.5). The tonal answer is of the convoluted, difficult kind engendered when the subject begins on the fifth degree and moves off to the key of the dominant, for the answer must negotiate a harmonic, nonsymmetrical return to the tonic while yet preserving what it can of the intervallic integrity of the subject. Bach’s answer provoked Marpurg, in his encyclopedic study of fugal answer (“Vom Gefährten”) in volume 1 of the Abhandlung von der Fuge, to construct an alternative (shown in ex. 12.6), in which the transposition of the minor second to the minor third is put off till the last moment. “Both ways are appropriate to the modulations of the subject,” Marpurg concludes, failing to discriminate how Bach’s climactic B A# G♮ F# clinches the return to the tonic, whereas his modification C# B# A F# only subverts it.17

EXAMPLE 12.6 J. S. Bach, WTC I, Fugue in B minor: Marpurg’s answer, realized in Abhandlung, I, 84.

Tovey, in the preface to his edition of the Well-Tempered Clavier (1924), spoke boldly of a “tonal answer … almost impossible to harmonise.” Taking his cue from a manuscript believed to date from 1722, in the hand of the Bach copyist known latterly as Anon. 5, he believed this tonal answer to have been a later variant. “The autographs,” he inaccurately writes, “leave it doubtful whether Bach was really satisfied with his alteration there.”18 And Alfred Dürr, the redoubtable editor of the Neue Bach Ausgabe, allows that Bach may well have hesitated over this answer, experimenting with what we might call Tovey’s variant (shown in ex. 12.7) before plumping finally for the difficult one.19

What, then, does Kirnberger make of this notorious m. 13? His analytical grid of these bars is shown as ex. 12.8. The small F# shown in the bass on stave 5 (which gives the fundamental bass with dissonances expressed as figures above the stave) and stave 6 (the fundamental harmony now scraped clean of inessential dissonances) is the critical element. An integral root in the harmonic track, this missing F# must be interpolated, even while the sounding surface of the music seals it out. Kirnberger’s comment does not trouble over the epistemology of such an interpolation: “In a few places the motion of resolution from a dissonant chord is represented through a small note in the fundamental bass.”20

Kirnberger’s precise language here—“der Uebergang der Resolution eines dissonierenden Accordes”—brings to mind, in yet another context, that well-known passage from the final paragraph in the last chapter of part II of Emanuel Bach’s Versuch (1762). Here, Bach isolates an elliptical moment in a figured bass that, printed directly in Bach’s text, means to lay out the harmonic plan of a “freye Fantasie” fully realized, and engraved on a separate plate. (For an illustration, see chapter 5, fig. 5.1.) Bach’s explanation is worth having: “The transition [der Uebergang] from the seventh chord on B to the following chord of the second on B♭ constitutes an ellipsis, for really a six-four on B or a triad on C ought to have been interpolated between them.”21

EXAMPLE 12.7 J. S. Bach, WTC I, Fugue in B minor: alternative answer, from copy by Joh. Gottfried Walther (before 1748).

The two passages, in fugue and fantasy, differ tellingly from one another. The rigors of tonal answer and the obligatory counterpoints against it force Bach (the father) onto a kind of harmonic tightrope. At this signal moment, the constraints of tonal answer are in conflict with the implacable root motion whose theoretical underpinnings Kirnberger claimed were at the foundation of Bach’s music. But the ellipsis in the fantasy touches at the inner core of meaning. Emanuel Bach’s gloss, characteristically terse, concentrates on the bass alone. Responding to precisely this gap in the harmony, the realization celebrates a moment of tonal and metaphorical distance in a convoluted passage of inspired improvisation—for we are meant to imagine this fantasizing as though witness to the process through which the music emanates. In setting Bach’s fugue against this scrim of putative roots, Kirnberger unwittingly invokes the rhetorical poetics of the fantasy, while Emanuel Bach, in rendering the diminutions of his fantasy as figured bass, invokes a venerable model of simple coherence to ground a music emboldened by a new poetics of harmonic syntax.

We are returned finally to Beethoven’s Haugwitz setting: more precisely, to the Uebergang at “findet nicht.” In resonance with the fugue for Haslinger, at its dissonant midpoint—in resonance as well with bar 13 of Bach’s B-minor fugue; and with the moment of ellipsis in the fantasy by Emanuel Bach—the harmony between “sucht” and “findet” gets caught on the upper intervals of an implied dominant seventh whose root is B. Its resolution elided, the missing root—the E—is sounded finally and with great éclat at a defining moment of Entschlossenheit: “Du musst nun los dich binden,” a phrase sung at first in B minor, sounds forth now triumphantly in the tonic.

The lines of thought laid out in ex. 12.9 mean rather to suggest than to syllogize how it might be that the transcribing of Bach’s B-minor fugue will have exercised this concept of ellipsis that I hear both as the gist of Beethoven’s song and as a topic of discourse at the center of the fugue for Haslinger; and, further, to suggest how the song and the fugue seem as though two reflections on the common intervallic archetypes of Bach’s subject.

What do any of these admittedly modest projects have to do with “lateness”—with a late style, with last works, even with that elusive moment at which the mind begins to picture itself as old? Whatever the explanatory devices with which we come to grips with the music of Beethoven’s final decade, these entries in Boldrini have their place.

Fugue and song figure preeminently in Beethoven’s last works: not, of course, as genres in the naive sense, but as modes of diction mediating, in their directness of discourse, the stripped-down narratives of sonata, or as dispassionate, fragmentary representations of genre—the ruins of genre, to paraphrase Adorno. The fugue for Haslinger was intended to herald an important issue of Beethoven’s collected works. If it does not transcend the conventions of genre, it yet prefigures “late style” in its dead-serious play with the boundaries of fugue—but then, even Beethoven’s earliest fugues indulge in such play, and even then, seem to prefigure what we have come to hear as “late” music.

The Haugwitz setting is similarly problematic in this respect. Highly esteemed by Schindler (with whom Thayer, via Deiters and Riemann, for once concurs),22 and more recently by Ewan West, the song yet seems constrained by the old rules of genre. West, hearing “poetic reinterpretation” in Beethoven’s composition, construes this “Neukomposition des Textes” as “Merkmal des romantischen Kunstliedes” which then places the song “klar in einen modernen Kontext.”23 That, I think, gets the matter the wrong way round. For if we are casting about for the “Merkmale des romantischen Kunstliedes” in 1817, Resignation seems miscast in the company of Schubert’s Nähe des Geliebten (1815) or Loewe’s Erlkönig (1818). Where Beethoven’s music “misreads” the poem, the matter hinges upon a point of diction, a turn of phrase. Its marrying of tone to syllable, of harmony to syntax, is fixed in the precepts of the classical Lied. It is precisely the idea of the modern that is challenged in the works of Beethoven’s last decade; modernity as a value is questioned, problematized.

EXAMPLE 12.8 Kirnberger [and J. A. P. Schulz], Die wahren Grundsätze zum Gebrauch der Harmonie (Berlin: Decker und Hartung, 1773), pp. 62–63.

Broadly conceived, this fugue and this song are self-evidently “late works” neither in the real time of Beethoven’s calendar, nor in spirit, nor even in some metaphorical sense. It is only the occasional gesture that places them for us in 1817: in the song, the iterated C-major triads in root position that erupt from the bare octaves on B, brazenly contradicted; in the fugue, the supreme dexterity of its final bars, an effortless, prismatic mutating of the figures and the rhythms of the subject, a texture luminous in its density. The virtuosity is made to vanish in the sudden piano of the last bar. With its final breath, this slightest of gestures, the composer seems to take back the work. Precisely here, in a perceptible shift in voice, we sense the recalibrating of object-subject that Adorno was so at pains to locate in the late works.

This fragile constellation of projects documented in the opening pages of Boldrini situates for us a quiet moment of internal colloquy: a stillness in the autumn of 1817. Sucht—findet nicht—lisch aus mein Licht: What was it that Beethoven was seeking? What did he fear not finding? “Man enträthsele—mann wird finden,” he scribbled cryptically at the end of a letter to Haslinger in September 1823, as though to set the sullen Haugwitz back on course—roughly: “Unriddle and you shall find.” The phrase itself, and its puzzling connection to the substance of the letter, led Hans-Werner Küthen to explore an allusion to the inscription “Quaerendo invenietis” which marks the Canon a 2 in Bach’s Musical Offering—and to Beethoven’s Bach project in general.24

In the music of Beethoven’s final decade, the questioning and the seeking—the unriddling—exercised to exhaustion, take on a metaphysical tinge. A consuming exhaustion, symptom of a certain aesthetic, a style, a view of a timeless past, it brings to mind an insight that Christoph Wolff drew from his study of the canonic appendix to the Goldberg Variations. Did Bach, Wolff asks, finding it difficult “in his later years to invent new and stimulating musical subject matter,” choose rather to concentrate “on the contrapuntal elaboration and refinement of a single musical idea with the aim of exhausting its content?”25 Bach’s consuming project is brought to an almost perfect completion, rational and exhaustive, in the Kunst der Fuge. In Beethoven’s last quartets, the exploration is no less consuming, no less exhaustive, even as its fugues avowedly reject—as they must—Bach’s austere, encyclopedic spirit of investigation. And yet it seems to me that deep in what Dahlhaus would call the “subthematicism” of the late quartets is embedded a rehearing of Bach’s enterprise—a reformulation of this notion of a final exhaustion. Coupled dialectically in the historical imagination, the phenomena of these two empyreal projects, Beethoven’s and Bach’s, fuse together into a generalized language of late style, at once a monument to the exhaustion of Art and a source of its renewal.

APPENDIX 12A Beethoven, Resignation, WoO 149

APPENDIX 12B Beethoven, Fugue for String Quintet, Opus 137

APPENDIX 12C Beethoven, Allegretto for String Quartet. With kind permission of the Fondation Martin Bodner Cologny.