There is no future for election observation if it becomes politicized.

—Ambassador Janez Lenarčič, 20081

Two facts are by now quite obvious: Some organizations assess elections more leniently than others, and no organization has a perfect track record.2 Observers sometimes recount political briefings before missions that reveal organizational biases.3 As noted in a training document for European Commission election observers, sometimes observers are “allowing themselves to be swayed by the political interests of their home countries or the dispatching organization.”4 Biases were present in the earliest of missions,5 but time has not erased them. One need only look at the 2008 presidential election in Armenia where both the European Parliament (EP) and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) were criticized for their leniency.6 Even their own delegation members were dismayed7 when the organizations, after much handwringing, concluded that the election, in which a small margin of victory avoided a runoff election, “was conducted mostly in line with the country’s international commitments.”8 The assessment did add that further improvements were necessary to address remaining challenges, but such phrases are so common as to have almost lost any meaning.

It is puzzling that organizations endorse bad elections, because this hurts their reputation and effectiveness. Like other transnational actors, their moral authority and influence depends on their veracity.9 If politicians can easily dismiss the organizations’ assessments as unreliable, then they need not worry about what the monitors say, and therefore they need not be concerned about whether the monitors witness any fraud. Monitoring organizations that lack credibility therefore lack influence. Furthermore, false endorsements may also legitimize undemocratic regimes, enable government manipulation,10 and stifle viable opposition movements.11 These effects only compound criticisms of the international community’s narrow focus on elections.12 Why, then, do international monitoring organizations nevertheless sometimes squander their precious moral authority?

Whereas the previous chapter described the rise of a shadow market in which governments strategically use more lenient organizations to avoid or spin criticism, this chapter examines some of the factors that may influence how organizations assess elections. Identifying such possible biases is necessary to assess the legitimacy of the monitoring process itself and identify when assessments may be questionable. It also advances the general study of transnational actors, who are playing increasingly consequential roles in global governance.13 Scholars have long contended that transnational actors are both normative and strategic,14 but only more recently have they begun to study how their politics and preferences influence their behavior.15 Uncovering what influences the assessments of monitoring organizations therefore contributes to a richer understanding of the behavior of international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and intergovernmental organizations (IGOs).

To consider the quality of monitoring information and the legitimacy of monitoring more generally, this chapter systematically analyzes the determinants of monitors’ assessments. The chapter will show that monitoring organizations are not as objective as they profess: International monitoring organizations sometimes endorse elections not only to protect the interests of their member states or donors, but also to accommodate other compelling but tangential organizational norms. Although I call these “biases,” they are not inherently bad. At times these other factors align with the monitors’ core objective to assess the election quality; at other times, however, the monitoring organizations face a dilemma between accommodating these factors and assessing the election honestly. Both norms and interests therefore can compromise the objectivity of the monitoring organizations. As noted by International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA), an organization specializing in elections around the world,

The options open to observers on the ground when they detect serious deficiencies in an electoral process are frequently limited. Observers seldom operate in a political vacuum, and may face significant pressures constraining them from expressing their true convictions about the conduct of the electoral process if they are critical of it.16

The analytical focus in this chapter is on the summary assessments that monitors provide immediately following an election. As discussed in Chapter 1, although some organizations claim to avoid making categorical or simplistic “free and fair” or “thumbs up/thumbs down” statements, most organizations do—or at minimum are perceived by domestic and international audiences as doing—just that. For example, in the 1996 Bangladesh election, the National Democratic Institute (NDI) stated in a preliminary statement that “our purpose here has not been to supervise or certify the election . . . for it is the Bangladeshi electoral authorities, and ultimately the people of this nation, who must judge the quality and character of these elections.”17 Yet a week later, the NDI concluded: “We believe that the irregularities and problems that there were, although real and serious, were not of such a nature and scale, as to suggest that the result, taken as a whole across Bangladesh, fails to reflect the will of the Bangladeshi people. Once again, we found the electoral process . . . to be fundamentally transparent and honest.”18

This is typical of the statements monitors issue immediately after an election, called post-election statements, preliminary statements, summary assessments, or simply press releases. These are followed by a longer report issued months later. The latter reports are quite detailed. The executive summary or conclusions of the final report typically repeat the summary assessments rendered immediately after the election, but the report’s content often differs from the executive summary or conclusion by providing not only greater details, but often much more critical remarks. However, by the time the longer report comes out both the media and the world’s attention have moved on, and details in the reports frequently escape attention. Thus, the world primarily hears the statements made shortly after the polling or the overall assessment that is usually repeated in the executive summary or conclusion of the final report. Therefore, the dependent variable is the overall summary assessment of an election by an individual monitoring organization. This summary assessment was used to create a three-level variable of whether the organization assessed the election as acceptable, ambiguous, or unacceptable. Appendix A describes this further.

Monitoring organizations themselves justify the analytical focus on the summary assessments. In its “Reporting Guidelines” the European Union (EU) stresses that in the early statements, “considerable care should be taken to drafting [the “headline conclusion”] so that it is [sic] clearly describes the overall view of the Mission. This is the phrase likely to be used by the media when reporting the findings of the Preliminary Statement.”19 Election experts elsewhere also support the analytical focus on the summary messages by the monitoring organizations. The commission created to inquire into the aftermath of the Kenya 2007 election wrote: “It must, however, be noted that the impact on legitimation is not always achieved by carefully thought-out reports, based on the information collected by observers and carefully analysed and chronicled by the media. Nor should it be assumed that the higher the quality and accuracy of the information on which the report is based, the greater the impact on public opinion. Opinions are in many cases shaped by observer mission statements issued shortly after polls close and based rather more on overall political evaluation of the after-poll situation than on careful and detailed analysis of the information collected by the observer mission.”20 Reports rarely attract much attention after the initial statements.21

The fact that organizations often contradict their own summary endorsements by providing details of serious fraud and irregularities in the body of their reports is part of the puzzle of why monitors sometimes knowingly endorse problematic elections. The OSCE report from Russia’s 1999 parliamentary election provides a typical example of such contradictions. According to the OSCE, polling day of the 1999 election went well.22 The preliminary statement discussed various problems, but stressed up front that “the 19 December 1999 election of Deputies to the State Duma marked significant progress for the consolidation of democracy in the Russian Federation.”23 However, the final report documented major irregularities and contained many contradictions. The executive summary concluded that “the electoral laws . . . provided a sound basis for the conduct of orderly, pluralistic and accountable elections,”24 but the body of report identified a “major flaw in the legislation”25 and criticized it in numerous ways.26 The executive summary also said that the election reflected a “political environment in which voters had a broad spectrum from which to choose,”27 but the report documented abuses of government resources28 and bias and restriction on the media.29 In the press conference immediately following Russia’s March 2000 presidential election the OSCE similarly gave the election an essentially clean bill of health, despite later issuing a harsh report full of violations of international election standards.30 Thus, the OSCE was aware of the serious problems, yet chose to remain encouraging in the post-election press conference and ambiguous in its final report, even after describing the extent of the fraud.31 The Moscow Times later reported that OSCE observers, speaking on condition of anonymity, “expressed disgust for the cheery tone of the day-after OSCE commentary, and dissatisfaction that the more thorough, official OSCE report on the elections—which was published two months later and was harsher and more informed—got no attention.”32

Similar contradictions arose in the OSCE statements on the Bosnia and Herzegovina 1996 election. The OSCE prefaced its preliminary statement with considerable handwringing: “The CIM recognises the unique complexity of this election in a post-war environment, in which the election process is intertwined with a conflict resolution process. Therefore it is difficult to assess the election process in Bosnia and Herzegovina, after four years of war, in accordance with the term ‘free and fair’ as it is usually understood. The criteria as expressed in the OSCE Copenhagen Commitments (attached as Annex 2) and the Dayton Peace Agreement remain the only relevant yardstick. Yet the election must also be considered in a conflict-solving capacity.”33 Both the preliminary and the second reports outlined numerous serious election irregularities. Nevertheless, the second report concluded that “the elections, although characterised by imperfections, took place in such a way that they provide a first and cautious step for the democratic functioning of the governing structures of Bosnia and Herzegovina,” and that “these imperfections and irregularities are not of sufficient magnitude to affect the overall outcome of the elections.”34 The message for the world was that the OSCE and the UN accepted the outcome of Bosnia’s 1996 election, leading some to accuse the OSCE of spin.35 Other examples can easily be found in reports from other organizations, but since the OSCE is considered one of the most reputable organizations, these examples illustrate that the problem extends beyond a few “bad apples.”

The focus of the analysis in this chapter therefore is to understand what factors influence whether monitoring organizations will issue favorable summary assessments of an election. How do the irregularities observed in the election explain the assessments of monitors, and do other factors also correlate with the monitors’ assessments?

Many factors likely weigh in as monitors draft their summary assessments. Indeed, given the highly individualized context of any election, there may be as many considerations as there are elections. This chapter, however, focuses on a few major types of biases that derive from the development of the shadow market, the electoral norms monitors strive to uphold, and the environments they operate in. At least five such major biases exist: the glasshouse bias, the progress bias, the special relationship bias, the subtlety bias, and the stability bias. These five biases are supported by the statistical analysis shown in Table C.1 in Appendix C. The analysis includes variables that seek to capture the different types of irregularities in an election as outlined in the full-length monitoring reports. It also includes other characteristics of the monitoring organization, the country, and the election that may influence the assessment of monitors.

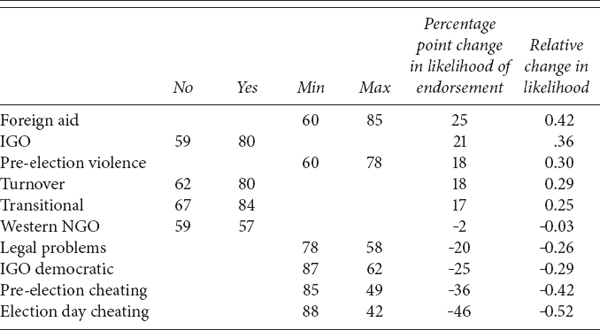

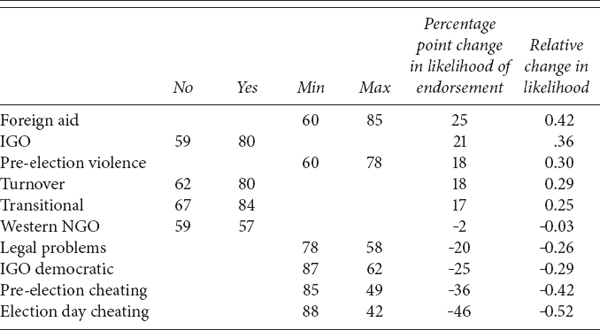

The analysis demonstrates that several factors predict observer assessments. These are listed in Table 4.1, which shows how much the statistical analysis predicts that each factor will increase the likelihood that monitors endorse an election. The table illustrates the change in the likelihood of endorsement when a given variable changes from minimum to maximum value, or, in the case of a binary variable, from no to yes. Thus, for example, row 4 shows that monitors endorse 62 percent of elections that do not produce a turnover in power, but they endorse 80 percent of elections that do produce a turnover. This is an absolute increase of 18 percent, or a 29 percent increase in the base likelihood of endorsement. The numbers are based on the underlying statistical model, but their primary purpose here is merely to give an impression of how important the analysis found each factor to be in relationship to the monitors’ assessments. The rest of this chapter discusses these factors and the five major biases.

TABLE 4.1

Predicted probabilities of endorsement

Notes: The table is based on simulations (using Clarify software) based on Model 2 in Table 4.1, for turnover and foreign aid on Model 3, and for IGO on Model 4, holding all other variables at their means, or, in the case of the organizational type, at 0. All figures are rounded to the nearest whole percent. Only significant variables are included in the simulation, but for viewing ease, standard errors are not displayed.

The previous chapter’s discussion of the shadow market showed that less-democratic countries might try to constrain monitors who come to their country. Furthermore, not only may governments be concerned about monitors inside their own countries; they may not want critical organizations to operate freely in their region or neighborhood, because this may increase pressure on their own governments in the future. To protect their own regime from future criticisms or to prevent democratic transitions in their neighborhood, they may therefore seek to restrain critical organizations. For example, after the OSCE’s active role in the “color revolutions” in Georgia and Ukraine, Russia has (unsuccessfully) pushed for institutional reforms to curtail the independence of OSCE observers.36 Thus, organizations associated with many undemocratic countries may be more reluctant to criticize elections. One might call this the glass house bias. As the saying “those who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones” suggests, undemocratic regimes may want to constrain criticisms directed at other states.

This raises the question of whether some of the differences observed in the previous chapter stem from the structure and membership of the organizations. Most notably, IGO member states have considerable influence and may prevent consistent application of standards. This has been seen, for example, within the International Monetary Fund (IMF).37 Although some IGO staff has flexibility to implement their agendas,38 most monitoring mission staff has little flexibility in drafting official assessments. Indeed, organizational documents and discussions with officials reveal that most IGOs have strict procedures for finalizing their official statements. Both the EU and Organization of American States (OAS) observer missions, for example, have strict supervisory mechanisms for the drafting of statements.39 NGOs must also worry about their funding. The U.S. organizations in particular depend on grant or contract opportunities by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) or other government agencies to monitor specific elections. Nevertheless, NGOs face fewer constraints than IGOs.40 NGOs tend to have multiple and diverse stakeholders, which counters the dominance of donor preferences.41 Furthermore, NGOs do not speak directly for any governments or donors, and this may give them greater freedom; certainly they do not face formal institutional procedures that allow governments to veto the wording of the election assessments.

Yet, even if IGOs can impose more constraints, not all IGOs are equally constrained. The statistical analysis shows that the degree of constraint that donors and member states impose on organizations depends as much on the level of democracy in the member states as on the organizations’ formal structure. Although IGOs are almost twice as likely to endorse elections, this tendency declines the more democratic an IGO’s members are.42 This is quite consistent with the argument in the previous chapter about the shadow market, because it suggests that organizations experience political constraints. Simulations based on the statistical analysis show that the predicted probability that an IGO endorses an election is 80 percent, a sharp contrast with only 59 percent for Western NGOs (see Table 4.1). Whether an NGO is Western or not makes little difference. However, it does matter how democratic the membership of an IGO is. The predicted probability that “low democracy” IGOs endorse an election is 87 percent, but only about 62 percent for “high democracy” IGOs—much closer to that of NGOs.

The subtlety bias means that monitors are more likely to endorse elections with subtler types of irregularities. Although a broad set of conditions is necessary to ensure a free and fair election,43 critics have long contended that monitors focus excessively on election day problems. This was apparent, for example, in Cambodia in 1998, when the Joint International Observation Group (JIOG) focused on the polling and counting days and in 2000 in Zimbabwe, where all the observers praised the calmness of election day itself. It was also evident in the election in Russia in 1999, described above, where election day ran smoothly and there were few signs of obvious breaches of the laws.

Election monitoring reports do stress obvious election day irregularities, but monitoring organizations also observe subtler types of fraud and evaluate the pre-election period. Thus, at least in the body of the election monitoring reports, just as much space is devoted to these issues as to others. The question, however, is whether, in making the overall assessment, monitoring organizations emphasize some types of irregularities more than others.

To explore this, the project analyzed the content of election monitoring reports in five major categories: legal problems, pre-election cheating, pre-election administration, election day cheating, and election day administration (Table 4.2), each of which were coded as having no, minor, moderate, or major problems, as discussed further in Appendix A.

The analysis suggested that when major problems were reported, endorsements were more likely to occur when those problems took place during the pre-election period (Figure 4.1). When organizations found major pre-election administrative problems, they nevertheless endorsed the election about 35 percent of the time. When they found major pre-election cheating, they endorsed elections about 23 percent of the time. Monitoring organizations endorsed elections with major legal problems least frequently, followed by elections with cheating on the day of election and administrative problems on the day of election.

Figure 4.1 is useful in that it simply shows how often monitoring organizations endorse elections when they themselves have observed certain types of irregularities. However, if organizations seek to render a mild overall assessment, they may downplay details in their report. Thus Figure 4.1 may be misleading, because it is based only on the organizations’ own reports. Figure 4.1 also does not make it possible to sort out the relative weight that organizations may put on different types of irregularities.

TABLE 4.2

Election irregularities

Variable |

Description |

Legal problems |

Legal framework not up to standards, limits on the scope and jurisdiction of elective offices, unreasonable limits on who can run for office, etc. |

Pre-election cheating |

Improper use of public funds, lack of freedom to campaign, media restrictions, intimidation, etc. |

Pre-election administration |

Voter registration and information problems, complaints about electoral commission conduct, technical or procedural problems, etc. |

Election day cheating |

Vote padding, tampering with ballot box, voter impersonation, double voting, vote buying, intimidation, etc. |

Election day administration |

Insufficient informational about rules and polling locations, lax polling booth officials, long waits, faulty procedures or equipment, problems in voters’ list, complaints about electoral commission conduct, etc. |

Note: All categories are coded as none, minor, moderate, or major problems. See also Appendix A.

To rectify these problems, the statistical analysis (in Appendix C) took advantage of the fact that more than one organization was present in nearly three-quarters of the elections. For each election new variables were generated based on the maximum level of each type of irregularity reported in the body of the report by any organization present. Since no organizations can be everywhere, combining their observations improves the documentation and produces a more comprehensive measure of the breadth of what monitoring organizations have observed. This also goes some way toward ameliorating any intentional under-reporting.

Using these measures, the statistical analysis showed that monitors tend to pay more attention to obvious cheating on the day of election as well as in the pre-election period, and to legal problems. Only these categories are consistently significantly associated with whether monitors endorse an election, and the magnitude of their coefficients is also larger than that of the more administrative problems. Table 4.1 shows the results of using simulations to predict changes in outcomes when the values in the categories change from minimum to maximum. For example, if legal problems rise from none to the highest level, then the probability of endorsement will decrease about 20 percentage points. An increase in election day cheating shows the strongest effect with a 46 percentage point reduction in the probability of endorsement. It is interesting to note, however, that when there is a lot of cheating, monitors more often shift to an ambiguous assessment rather than to an outright denouncement. This is generally true for all the categories.

Figure 4.1: Percent of elections endorsed by international monitors despite major problems of a given type

Includes data on the organizations in Table 2.5, excluding the UN, the ECOWAS, the OAU/AU, and La Francophonie.

The focus on overt cheating and legal problems may be because monitoring organizations view these offenses as most damaging to the integrity of the election; administrative problems during the pre-election period may be easier to condone, because they can be construed as unintentional and if voters can act freely in the polling booth at least the possibility of choice remains. International election standards are also most direct in detailing the prominent elements of an election: the right to have votes counted equally and for voters to be able to exercise their political views free from intimidation and fear. No legal standard speaks directly to how the electoral commission should behave or how voter lists are compiled, although these factors clearly influence the ability of voters to choose freely. Similarly, monitors may focus on the legal framework for elections, because election monitoring originally began very much as an initiative of legal experts such as the International Human Rights Law Group (IHRLG). To this day, missions remain quite heavily staffed with legal experts.

Monitoring organizations are usually cognizant of the risks of observing elections that are highly likely to be fraudulent.44 Ironically, however, organizations such as the EU are also more likely to send missions to countries where they, or individual member states, have interests at stake, sometimes even if they expect the elections to have little chance of being acceptable. In some contexts, monitoring organizations may therefore experience particularly strong political pressure to be lenient toward countries with which they or their sponsors have a special relationship. Examples are plentiful. The Bosnia and Herzegovina elections in 1996 came at the end of the long engagement by the West in the conflict in the region and were important for the Western countries that had been engaged in the region for the first half of the decade. The OSCE was actually supervising the elections, not simply monitoring it. Furthermore, the election occurred just before presidential elections in the United States, which had staked much on acceptable elections in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Russia similarly benefited from some special concern in the mid- to late 1990s when the OSCE and the EU observers were hesitant to criticize the election although the obvious state dominance of the political space prevented true competition. In Zimbabwe in 2000, the election described in the previous chapter, the monitors from the South African Development Community (SADC) and what used to be the Organisation of African Unity had strong ties to Zimbabwe and this most likely contributed to their unwillingness to offer much substantial criticism. Another example of political pressure is the 1999 elections in Nigeria when important countries wanted to restore normal relations.45 Both the Commonwealth Secretariat (CS) and the EU “sent their missions with strict warnings that their home governments wanted to endorse the elections and restore normal relations with Nigeria.”46 Thus, some organizations assign political importance to certain elections and criticize them less. Monitoring organizations may therefore display a special relationship bias toward geopolitically important states.

Although there are examples of elections where political pressure seemed prominent, these are idiosyncratic and therefore difficult to capture in statistical analysis. However, it is possible to see a pattern in foreign aid, which often connotes a political relationship.47 As Chapter 2 discussed, foreign aid recipients already are more likely to be monitored, because donors often pressure aid recipients to accept monitors. Donors also have been keen for these countries to pass the election test so aid can continue or be resumed.48 In Cambodia in 1998, for example, Japan, Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and Western governments wanted to resume aid and normal relations, and this constrained the IGOs monitoring the election.49

A review shows that monitors have indeed been more likely to endorse elections in nations receiving foreign aid.50 Of the 70 missions to countries that received more than U.S.$1 billion in aid the year before the election, 54 endorsed the elections. That is a rate of 77 percent. In contrast, missions to countries with less or no aid endorsed elections 62 percent of the time. The difference could be because aid is given conditionally on good governance, in which case aid recipients would be inclined to hold cleaner elections. However, foreign aid does not seem to be a predictor of quality elections more generally. Indeed, one would expect foreign aid levels to correlate more with countries with poor domestic capacity and thus more problematic elections. The statistical analysis in Appendix C also suggests that monitoring organizations are more likely to endorse elections in countries that receive foreign aid, and the simulation results in Table 4.1 suggest that the effect is quite large, but in more extensive analysis the finding is not entirely robust. Thus, although there is some evidence that organizations are more lenient toward foreign aid recipients, generally the geopolitical pressures may be too difficult to capture in statistical analysis, as geopolitical relationships tend to be highly nuanced and idiosyncratic.

Many international monitoring missions are based within an agency that seeks to promote democracy. So when progress is partial but the election still falls short of meeting democratic standards, monitors may praise the progress, hoping their encouragement will help consolidate the gains. This bias makes monitors more likely to endorse elections in countries that display important progress. There are clear concerns that “to deny elections a passing grade would . . . risk provoking greater political closure.”51 This progress bias may lead monitoring organizations to endorse the results despite the still-flawed nature of the election.52 Indeed, when monitors endorse highly problematic elections, words like improvement and progress often permeate their public statements. In the 1998 Cambodia case, for example, the JIOG stressed that the election was “a major achievement and a step forward.”53 In Kenya in 1992 the International Republican Institute (IRI) statement ended a critical report with a follow-up statement saying, “but from our perspective we feel that this process is a significant step in Kenya’s transition to genuine democracy.”54

To assess the effects of the progress bias the statistical analysis used several different measures to examine the relationship between progress and endorsement. One indicator captured whether the organization itself described the election as “transitional” in its report. The analysis showed that international election monitors were more lenient toward countries transitioning toward democracy. The likelihood of an election being endorsed increased by 17 percentage points, from 67 percent for elections not characterized as “transitional” to 84 percent for those characterized as “transitional” (see Table 4.1).

Monitors also appeared more lenient with first multiparty elections. Monitors endorsed all the first multiparty55 elections in the data with only minor problems while they condemned all the first multiparty elections with major problems such as those in Cameroon, Tanzania, Guinea, and Rwanda. However, when comparing elections that fell between these obvious cases, monitors more often endorsed first multiparty elections than not. However, in the statistical analysis this effect was never significant, and Table 4.1 therefore does not include predictions about first multiparty elections.

Finally, the analysis also showed that monitors were less likely to endorse the election if the incumbent kept power. Or, in other words, if the opposition won, the monitors were more likely to endorse the election. This is probably because, although the opposition sometimes also cheats, the incumbent is usually assumed to have the upper hand and a turnover of power is thus often seen as significant sign of progress. It is harder to claim that an election was fraudulent if the opposition managed to win. The simulation results in Table 4.1 show that that the probability that monitors will endorse an election jumps from 62 percent if the incumbent keeps power to 80 percent if the incumbent loses power.

Thus, monitoring organizations do show a progress bias. Measures of transition, first multiparty elections, and turnover all suggest that monitoring organizations are more lenient toward countries that appear to be making progress toward democratic ideals. The excitement of a transition or a change of power may lead to overly optimistic assessments of the quality of the election. This is indeed something the international community has observed time and again as the second elections after a supposed transition often will display what looks like backsliding.56

The stability bias means that monitoring organizations consider how their assessments may influence stability in the country. Although the prominent Cold War security-democracy dilemma eased with the rise of election monitoring in the early 1990s, violence during fragile democratization processes continues to concern the countries and organizations that work to promote democracy.57 If international election monitors worry that their assessments may fuel violence, they may downplay their criticisms.58 This is particularly worrisome, because strategic use of violence has even graver human rights implications than strategically omitting voters from the official registrar or restricting the media.

Monitors are more likely to worry about violent reactions to their assessments when pre-election violence has been widespread as in Zimbabwe, Cambodia, and Kenya. In such cases, the capacity for violence has already been demonstrated, and denouncing an election as flawed is more likely to provide a focal point for the opposition and fuel violence even further. As the elections in Zimbabwe in 2008 showed, incumbents who are unwilling to leave office may resort to violence to squash opposition supporters. Of course, it is also possible that opposition forces may revolt against what they perceive as a rubber stamp by election monitors. In the majority of cases, however, power lies with the incumbent and stability is best maintained by supporting the incumbent. If the incumbent is responsible for pre-election violence and then conducts a calm election day, monitors may downplay their criticisms in the interest of peace.

Examples abound. In Zimbabwe one commentator noted, “Perhaps it had become quite clear to all foreigners that if the opposition had won the elections, changing the government in Zimbabwe would not necessarily have been easy or peaceful.”59 Indeed, the EU mission took pride in having “contributed to reducing levels of violence.”60 In Kenya’s 1992 election, fears of upheaval also tempered the criticism of outsiders.61 The EU mission to Nigeria in 1999 likewise was caught in the dilemma between violence and truth. During the presidential election, “EU observation teams witnessed blatant examples of ballot box fraud in most of the 36 states of the Federation. The most celebrated instance was in the troubled oil-producing state of Bayelsa in the coastal Niger Delta region where, according to the Federal Election Commission’s own figures, the turnout was 123%. Conflict within the EU delegation pitted a sizeable minority, which sought to make a formal condemnation of the election outcome, against a majority which favoured rapid stabilisation of a high-risk political situation.”62

To examine the relationship between violence and endorsement, the analysis included measures of both pre-election violence and violence on the day of the election. The patterns in the data suggest that pre-election violence tempers criticism, but that a lot of violence on election day increases criticism. However, if a high level of pre-election violence is followed by a relatively calm election day, then monitors may hesitate to denounce the election because of the pre-election violence. Once election day turns violent, monitors realize that post-election stability is unlikely and that their statements cannot really change that. Furthermore, if election day is violent, a lenient assessment is likely to draw criticism. But if election day remains calm, then monitors may hope that the regime has the ability to maintain peace. As an example, the initially calm election day may be what led the EU to be quite positive at first about the election in Kenya in 2007. The chief of the mission told the press on election day that he had seen no evidence of fraud: “There are some technical problems but what is pleasing is that people are turning out to vote in large numbers and are doing so peacefully and patiently.”63 Yet, the EU observers themselves documented 190 cases of election-related violence, including murders, and noted that victims complained that both the police and courts ignored their complaints.64 Thus it appeared that despite the horrendous pre-election violence, as long as election day was calm, the monitors were prepared to sound a positive note, the IRI even calling the election “successful” in the headline of its preliminary statement.65 However, after violence spun out of control, the EU mission quickly changed tone and denounced the election.

In the statistical analysis in Appendix C, election day violence was not significant, but violence in the pre-election period was statistically associated with greater odds of endorsement. This relationship was highly robust across all the models. The simulation results in Table 4.1 show that when pre-election violence increases from the lowest to the highest level, the probability of endorsement increases from 60 to about 78 percent, or an absolute increase of about 18 percent. This is remarkable, because pre-election violence and irregularities are also highly positively correlated and it would therefore be logical if pre-election violence were associated with smaller—not greater—odds of endorsement.

The assessment of the quality of an election must often be accomplished with insufficient personnel, local expertise, and funds. Is the information failure because the election monitors face a resource constraint? On average, monitoring missions have about eighty personnel present on the day of the election. However, a few outliers—missions that are able to send a far greater number of workers than most of their counterparts send—skew this figure. Thus, only about half of missions deploy more than thirty personnel on the day of the election. Because multiple missions frequently monitor the same elections, the average number of observers from various missions in any given election nears 135 per election. Again, however, outliers skew this, and only about half of all elections have a total of fifty or more observers from the main organizations in this study. Teams sent in advance, if any, are often smaller.

Meanwhile, the task is daunting: overseeing the integrity of the pre-election conduct of media and politicians, law enforcement, and administrative election preparation. In addition, on the day of the election, tasks include overseeing the polling process at thousands of voting stations, some very remote, as well as the handling of ballot boxes, the tabulation of the vote, the announcement of results, and the formal complaint procedures. Although monitors typically operate with a formal government invitation, full cooperation from the national and local authorities may be lacking or misleading. Thus, the sheer task of ascertaining the “truth” about the quality of the election is subject to numerous practical constraints.

However, it does not seem that resource constraint plays a big role in whether monitors endorse elections. Paradoxically, the amount of resources allocated to a mission is a poor indicator of its credibility. Missions to elections that are fully expected to be fraudulent are often small. Yet, because the fraud is so obvious, such small missions will tend to issue highly critical and credible assessments. Thus, smaller missions that criticize elections are not inherently less credible. At the same time, the more resources an organization invests in an election, the more likely it may be to spin its assessments positively. After all, when so many resources are marshaled in an attempt to ensure free and fair elections, doesn’t a flawed election mean the mission somehow failed? Clearly the OSCE and the United Nations (UN) faced this dilemma in the 1996 elections in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which they not only monitored but also supervised. When organizations exert particularly large efforts, their sponsors may expect to see some bang for their buck and elections should have benefited from the organizations’ presence.66 Larger missions, therefore, are not inherently credible. A larger mission may allow monitors to collect better information, but this is no guarantee that the assessments will be more honest. After the 2009 election in Afghanistan, for example, the UN mission in Afghanistan, which ran an election center collecting data on turnout and fraud, only revealed evidence about the high level of fraud after Peter Galbraith, the mission’s deputy special representative, publicly broke ranks.67

Figure 4.2: Relative changes in probability of endorsement based on changes from minimum to maximum values*

Based on Table 4.2. *In the case of indicators such turnover, it is the effect of moving from that indicator being equal to 0 (no turnover) to 1 (turnover).

What monitors say matters. Their endorsement can have important repercussions. In interstate relations it may affect future aid allocations,68 the lifting of sanctions, and a country’s standing in the community of nations. Even more important, it may matter domestically for the ability of a government to govern and to hold on to power and thus for the ability of the citizens to choose their government. As seen in Georgia in 2003 and in Ukraine in 2004, declarations of fraud can fuel revolutions or spur election reruns. Endorsements also can defuse tensions in elections that opposition parties otherwise might have challenged, as in Mexico in 1994, or facilitate the exit of the incumbent, as in Nicaragua in 1990.69 The assessments of monitors thus shape the governance of countries and the lives of their citizens.

The neutrality of observer assessments is therefore very important. This is why the 2005 Code of Conduct on election observation states: “No one should be allowed to be a member of an international election observer mission unless that person is free from any political, economic, or other conflicts of interest that would interfere with conducting observations accurately and impartially and/or drawing conclusions about the character of the election process accurately and impartially.”70 Thus, neutrality is essential to the legitimacy of the monitoring process itself.71

However, the analysis in this chapter shows that monitors are not always neutral. Because of their various norms and politics, different organizations may assess elections differently, and even the same organization may evaluate elections of similar quality differently depending on their contexts. Specifically, the analysis identified five different factors that make monitors more likely to endorse elections: the nature of the sponsoring organization, the type of irregularities, the transitional nature of the election, any special relationships such as foreign aid, and, finally, the level of violence in the pre-election period. Figure 4.2 summarizes the findings by graphing the simulation results from Table 4.1 (column 4) as relative changes in probabilities. These are the effects of moving from the variables’ minimum to maximum values. The findings establish more systematically than previous anecdotal evidence that certain biases are evident in the assessments and underscore that understanding the assessments requires attention to the monitors’ politics and preferences beyond their formal mandates.

These biases may not themselves be good or bad, but they nonetheless compromise the neutrality of the assessments. This diminishes the credibility and authority of international organizations and transnational actors and detracts from the legitimacy of the monitoring process itself.72

The biases also alert both scholars and practitioners to when it may be more necessary to filter the information from monitors. For example, it may be wise to question assessments supplied from monitoring organizations when they are reporting from countries with high pre-election violence, or from countries that get a lot of foreign aid or otherwise have special relationships, or from countries considered to be in a volatile transitional stage.

Another concern is that if these factors lead monitors to inflate their confidence in the quality of the election, this may then also temper the efforts of the international community to address remaining problems.