5How is aid delivered?

Learning objectives

This chapter will help readers to:

Understand the concept of aid modalities or modes of aid delivery

Appreciate the difference between lower and higher-order aid modalities

Assess different examples of aid modalities with particular reference to programmes and projects

Analyse how the application of different aid modalities has shifted across time and space and continues to evolve

Understand the nature and rationale for humanitarian relief and some of the longer-term challenges associated with it

Distinguish between various types of higher-order modalities including Sector-Wide Approaches (SWAps), general budget support GBS, debt relief and import support

Understand the rise of private-sector aid initiatives and associated new modalities, the rationale for these and some of the critiques that have been made

Introduction

The issue of how aid is delivered is a crucial one in terms of addressing key questions such as ‘does aid reach those for whom it is intended?’; ‘does it pursue and obtain its main objectives?’; and, ‘is it used effectively?’. A variety of ‘modalities’ – modes of delivery – are used in the aid world and these can vary greatly in terms of scale and time frames as well as parties and institutions involved. In this chapter we focus firstly on various aspects of modalities at various levels, placing most emphasis on projects and programmes. Firstly, we consider those that have characterised the neostructural aid regime. Then more recent approaches to delivering aid utilising private sector involvement associated with the retroliberal aid regime are analysed. As we will see these are novel and, as yet, largely unproven.

As a framework for analysing projects and programmes, we adopt a model developed for use by the World Bank (Koeberle et al. 2006). This envisages a progression in modalities from projects, through ‘pooled projects’ and ‘basket funds’, different types of SWAps to GBS. Movement from lower to higher-order modalities increases impact of aspects such as volume, operational scale and policy – and, ostensibly, development benefit. In what follows, we pay particular attention to ‘lower order modalities’ (projects) and ‘higher-order modalities’ (SWAps and GBS) and some of the forms in between.

Lower order modalities: projects

Projects have been the dominant mode in aid practice over the past 50 years or so. Projects have a number of characteristics and advantages. They involve defined objectives, means, outputs and time frames – all of which are articulated at the start of the project cycle in a planning phase. This rests on a key assumption: that development interventions involve processes which are observable, measurable, predictable and controllable through rational management systems. Projects also tend to involve development, which is about ‘providing things’ (whether physical or technical) that will have clear development benefits. Thus, if there is a problem of lack of adequate water supplies in a rural area, a project would involve, say, the provision of water storage facilities (e.g. a reservoir or tanks) and a reticulation system (e.g. pipes and taps to households). There is a clear problem, a planned intervention, a fixed agenda and a finishing point. Once the storage and reticulation systems have been constructed and are operating, the project is executed and the aid input complete. Donors and managers can then celebrate the opening of the facilities, complete an evaluation report and move on to the next project. It is, in theory, a tidy approach where risks are hopefully identified early on and mitigated accordingly.

The nature and scale of projects

Projects usually occur outside direct recipient government support. Government agencies may certainly be involved in the projects, giving permission, helping to identify the priorities, sometimes managing relations with local institutions, and often having officials involved in follow-up or complementary activities. However, typically projects do not involve the use of substantial recipient government resources. Aid donors provide the majority of financial and other resources. In some cases, for example when recipient states are weak and have little presence in remote areas, aid projects may be implemented almost without government involvement at all. In these circumstances, aid donors – whether government aid agencies or donor non-government organisation (NGOs) – will use NGOs or consultants to manage the projects and liaise with local communities. Donor agencies will keep an eye on projects usually through requiring regular reports from the project managers on the ground and it is not uncommon for aid officials to have to manage a large portfolio of projects from afar, dealing with funding, compliance and progress reports. Thus, although project management can be contracted out, there are still high overhead costs for donors.

Projects can vary greatly in size and scale. Many aid projects involve single activities. These are discrete projects with defined scope and time frame. They may involve the building of a water supply system, a school or a wharf. Such projects may have a major impact at the local scale – providing better sanitation systems or a health centre or access to primary schooling – but they are unlikely to have an impact on a whole country. Others may see a project template replicated across several projects and locations: a donor may develop particular experience and technical expertise in a certain area and be keen for this to be repeated, improving the efficiency and visibility of their aid spending. Thus, we have seen Japanese projects for irrigation and agricultural machinery, or Swedish projects on gender equity awareness. In this way, small projects are ‘scaled up’ by repeating a proven project approach in different places: what is sometimes called a ‘cookie cutter’ approach (meaning replicated in a standard way). Yet such projects are still rather limited in their ability to affect a wide area and deeply address issues of long-term policy and institutional change.

Small-scale projects have several advantages, largely because they are often linked to particular local situations and, hopefully, involve local actors and a degree of local ownership. On one hand, smaller projects may be regarded as inefficient because fixed and overhead costs are relatively high and economies of scale are not easily achieved. Yet, following Schumacher (1973), high relative costs may outweigh the negative sides of the high absolute costs that big projects incur with high debt burdens, a loss of community-level control and ownership and the potential for large-scale negative impacts should things go wrong.

Other projects can be large-scale, thereby increasing impact at higher levels. A hydro-electric dam, with associated electricity generation and distribution systems, water distribution and irrigation, and resettlement of affected communities can cost many millions of dollars and span a decade or more. They can achieve economies of scale and cost efficiencies, they can tackle development issues over wider areas and they can link different forms of activities (such as infrastructure). These large-scale projects again have a substantial aid donor component, often in the form of concessional loans, though we may see more of a role for recipient government agencies in managing the new facilities and being responsible for loan servicing and repayment.

Sometimes associated with these larger-scale efforts has been a concern to integrate different projects that complement one another. Lessons learned in the 1960s and 1970s pointed to the fact that a single large project could be limited in its ability to bring about development if it did not recognise the need for changes to occur in related activities. Thus, for example, the introduction of new high-yielding varieties of grain at the heart of the Green Revolution in the 1960s were of little use unless there were improvements in water management (requiring irrigation projects), or better marketing (requiring projects to build new roads, storage depots and processing facilities), or technical advice (needed extension services and farmer education), or equipment (leading to projects to provide agricultural machinery), and so on. These gave rise to the approach known as Integrated Rural Development. They were large and expensive operations that could cover a wide area and involve many different facets of the rural economy. Yet, as a modality for aid, they were still based on a combination of projects, i.e. activities that were pre-defined, closely managed and with a focus on particular outputs.

The project cycle and management

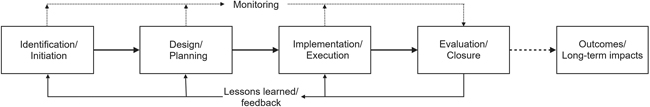

All projects, large and small, share a common feature in terms of design and operation, namely what is termed the ‘project cycle’. This sees a logical progression through various stages of a project: from project identification (where the ‘problem’ is seen and agreed upon); project design (involving, in turn, the identification of solutions, the planning of interventions and management systems, and, often, aspects such as feasibility or impact studies to gauge the likely success and risks); implementation (the actual expenditure of resources to address the problem and its solution); to project completion, the generation of outputs and the process of evaluation (when the project is deemed to have finished and lessons are drawn from it).1 The notion of a project cycle then implies that the lessons learned are fed back into the planning and design of similar and future projects. And so the process goes on, presumably with practices improving all the time and aid being used more effectively each time to enhance the development outcomes.

Alongside this notion of a project cycle has developed a particular approach to ‘project management’. This is a set of practices and tools that have evolved over time. Project management has become a specialised skill and many practitioners have gained training in this area and been employed widely in the aid world as independent consultants or specialists within aid agencies. Project management, in its increasing sophistication, attempts to ensure that projects are more and more tightly subject to rigorous techniques of prediction, planning, operational control and assessment. Monitoring and reporting are vital components as are various techniques to measure social and environmental impacts. Throughout, projects are seen to be rational and ordered attempts to bring about development, that try to predict impacts, mitigate harmful effects and ensure that aid funds are wisely and efficiently spent. Project success is determined by two main criteria: did the project come within or close to budget? Were the planned outputs constructed or provided as designed? The question of unforeseen impacts or long-terms outcomes of projects are largely left outside of the scope of project cycle management.

The benefits and costs of project modalities

Because they are ordered and in theory predictable, projects have proved to be a very popular modality for aid agencies. Aid donors can keep a close eye on how their money is being spent and there is an end in sight and, as mentioned previously, if things are successfully achieved the positive publicity reflects well on a beneficent donor.

However, projects have fundamental limitations as a modality in terms of aid effectiveness. Their impacts can only be limited to the discrete activities they involve and these are proscribed spatially and temporally. They are unlikely to make profound changes to a nation’s well-being, for example, unless they involve literally hundreds and hundreds of separate, but similar, projects in all parts of a country. Furthermore, project management may be effective as an approach to managing a single project but, in sum, is a rather inefficient way of managing change on a large scale. Overheads are replicated and multiplied, economies of scale are not achieved, and it can be difficult to communicate lessons from one project to another. Projects, as we have seen, focus on outputs rather than longer-term outcomes and thus they can miss the need to engage in activities which address the deep-seated attitudinal and structural causes of poverty. They also tend to work on the basis of the certain, the quantifiable, the observable and the manageable. In practice, development processes are highly complex, uncertain and sometimes chaotic and even violent. Projects attempt to contain and manage desired forms of change, whereas local people experience lives which are not so ordered or – by external eyes – rational and predictable. Projects fail when the unknown, the unplanned and the uncomfortable overwhelm the ordered certainty of a project planning document. And finally, projects tend to exclude the local national government. Not only is the opportunity not taken to draw on important government resources and support and develop their capacity, but also projects may act to undermine the perception of the effectiveness and legitimacy of the state by its citizens. If it is aid donors and external agencies – or local NGOs – that build schools or improve roads and water supplies, the state is seen to be marginal and ineffective in development.

Humanitarian relief

Although aid for development is usually channelled through projects or programmes, we should also note that significant amounts of aid are delivered not for explicit development activities but to address pressing humanitarian needs, such as disaster relief or refugee crises. Unlike projects, these forms of assistance are not pre-planned, but arise in response to sudden change: an earthquake, cyclone or tsunami; or a rapid change in refugee movements. Yet, such aid still has much in common with project modalities. Most major donors have developed over time sets of practices, and contingency funds, so that they can respond quickly and effectively to such emergency requests. Thus, once a disaster occurs, donors and many recipient agencies can swing into action, using project-like management techniques. Well-tested logistical networks can be employed, reporting and monitoring templates are used and, hopefully, a fixed time frame is achieved so that the assistance can be seen to come to an end and the crisis responded to.

Humanitarian assistance, as with many project approaches, concentrates on delivering resources to places and people in need. It is primarily about the alleviation of immediate suffering, ensuring the recipients have sufficient shelter, food, water and security. It can be effective or not at meeting these pressing needs – and in managing the process of delivery – but rarely does ‘relief’ turn to addressing what might be the deeper causes of human suffering (be they climate change, political oppression, or human-induced food shortages) or the systems of resilience which allow people to respond to disaster themselves (networks of support, livelihood alternatives, back-up resources). For these important issues, rather different approaches are needed: those which pay attention to long-term and often qualitative changes, and to building up assets and capabilities, rather than meeting deficits. These require an approach which promotes ‘development’ in different guises, but also a shift in the way is delivered – towards longer-term and broad-based modalities.

Figure 5.2 Distribution of relief supplies in Samoa following the tsunami in 2009

Photo: John Overton

Higher-order modalities: programmes

The realisation that projects have limitations in terms of efficiency and effectiveness with regard to large-scale development efforts led to a turn to higher-order modalities, especially since the launch of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2000. Even prior to the MDGs, donor agencies, such as the Development Assistance Committee (DAC), had been considering ways to improve the effectiveness of aid and provide evidence for aid producing meaningful results. It required a move from evaluating discrete projects under narrow output-based criteria, to suggesting and assessing ways in which sustained and long-term programmes across many sectors could achieve good development outcomes over perhaps more than one generation. To do this, a crucial change was the need to involve recipient states centrally in the aid efforts not just as passive observers, but as leaders and managers. Such modalities, then, are much more state-managed and involve a direct partnership between donors and recipient government agencies (Reinikka 2008).

The nature and scale of programmes

Higher-order modalities involve a progression over various forms, each of which involves a higher degree of hand-over of control to recipient agencies together with an increase in scale of the activity (Koeberle and Stavreski 2006). Not only does the volume of aid increase, but also the degree of involvement of local institutions increases, yet on the other hand, the degree of overt donor control seems to decline (even though they will have systems in place to ensure they keep watch on disbursement of aid). In short, these progressively higher-order modalities are SWAp and GBS:

SWAp: A Sector-Wide Approach (SWAp), as the name suggests, is an approach that involves the whole of a sector (health, education, telecommunications, agriculture etc.) and funding for this. It involves aid donor funds going to the respective government department to be spent on that sector. It requires that the government have a detailed strategic plan for the sector, outlining objectives, targets, strategies and systems that donors agree to, and that they have good mechanisms in place to implement and monitor the activities involved. With a SWAp, donors move to recognise the ability of a given government sector to manage itself. Agreement over the strategic plans and internal management systems are critical: they constitute the basis for a contract between donors and recipients. In many cases SWAps will involve one donor taking a lead, providing funds and some of the technical expertise. Other donors (both bilateral and multilateral agencies though rarely NGOs) will also contribute, whether by adding to a central pool of funding for the department, or quite commonly by nominating a particular part of it to support. SWAps are thus effectively a consortia of donors bringing together several strands of funding to secure a broad-based and continuing source of funding. Under a SWAp, donors provide funds, but substantial funding also comes from the recipient government itself – and again these amounts and how they are shared are specified before the SWAp is signed. Recipient government funding is essential as a sign of their commitment to the strategic plan and also as a basis for future complete self-funding. SWAps mean that the government department manages all the funds and ensures that the development strategy is pursued. It is a demonstration that they are in control of the development of the sector.

General Budget Support (GBS): This is the highest-level modality of aid and one that has sometimes been regarded as the ‘Holy Grail’ of the aid world. Within GBS, donors have very high levels of trust in the recipient government to ‘own’ and manage the country’s development and are happy to contribute, usually as a coherent group of donors, to the total government budget of a country. GBS involves the highest levels of trust between the government parties concerned. The volumes of aid may be very large and the commitments reliable and multi-year. Aid funds are given to the recipient government and they are fed into and controlled through and by the government’s own management systems. However, behind the apparent simple handing over of funds, there is a complex web of agreements and understandings regarding financial management systems, auditing, reporting and consultation. GBS is – or was – regarded by many donors so highly because of its potential for efficiency. Donors do not have to bear the cost of heavy overhead costs monitoring and managing individual projects, activities and flows of funds. There are considerable economies of scale to be had by scaling-up development activities at a national scale. Furthermore, duplications and competition amongst donors should be eliminated – bringing benefits for donors and recipients alike – and local systems are respected and supported (rather than facing parallel and competing donor systems), thus further building their capacity and capability. In these ideal terms, GBS has been regarded by donors such as the World Bank as the goal to which all should aspire for aid delivery.

Although we will see below how new aid modalities have emerged in the past decade, higher-order modalities remain very important. A review by the European Union in 2018 noted that the EU was the world’s largest provider of budget support, providing 70 per cent (€1.8 billion in 2017) of the global total (European Commission 2018: 7). The document defined budget support as follows:

EU budget support is a means of delivering effective aid and durable results in support of EU partners’ reform efforts and the sustainable development goals. It involves (i) dialogue with a partner country to agree on the reforms or development results which budget support can contribute to; (ii) an assessment of progress achieved; (iii) financial transfers to the treasury account of the partner country once those results have been achieved; and (iv) capacity development support. It is a contract based on a partnership with mutual accountability. (European Commission 2018: i)

Interestingly, this re-statement of budget support policy put stress on the achievment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a clear recognition that long-term and large-scale progress towards meeting the goals will require the active role of states and the use of reliable high-order modalities. The EU sees benefits in this approach in strengthening macroeconomic stability and good governance so that the private sector can thrive. Funding by the EU for budget support has been increasing since 2015, and it amounts to 40 per cent of the EU’s assistance to recipient countries. However, despite this commitment in Europe, it appears as if budget support is not expanding and is less of a priority for bilateral as well as multilateral donors.

Before we leave programme modalities, two other forms should be noted. These are not of the same nature as the SWAps-GBS framework, but they are regarded as forms of aid which are programme-based and with high recipient government involvement, albeit with rather less focus on development activities. They have to do with debt and trade:

Debt relief: This involves payments by donor governments to retire part of the debt of recipient governments. It does not lead directly to any development activity being funded, but it may relieve budget pressures on a government facing high debt servicing and repayment costs so that it can devote more of its revenue to operational matters. As a government-to-government transfer there may be agreements and conditions made with regard to public sector reform or particular economic or governance measures to be undertaken by the recipient government in exchange for debt relief.

Import support: This modality was used in the past to ease balance of payments problems for recipients. It involved either the provision by donors of important imported goods, including raw materials or capital goods, or financial assistance to purchase such imports. This approach has not been used much in the past 20 years.

Programme decisions, learning and management

Programme support in its different forms involves an evolving relationship between donors and recipient states. It is an iterative process in that, as programmes take place, the capacity of recipients to manage aid funds hopefully is improved and, as a result, higher-level modalities can be put in place. In this sense, there is an intended transition towards GBS as the ultimate and desired mechanism for aid delivery. SWAps are seen to be an important intermediate step between projects and GBS because they involve a first significant stage of recipient-led aid delivery. In practice, however, the transition to GBS has been far from complete and SWAps have tended to be the most common higher-order programme modality.

In the process of building these higher-order modalities, there are important assessments and decisions to be made regarding the handing over of greater levels of responsibility to recipient agencies. Agencies such as the World Bank use certain processes to decide how aid should be delivered. There are some critical stages and requirements in these (Koeberle and Stavreski 2006). Firstly, it is important for the government to have in place agreed structure for ‘general and sectoral policies and budget priorities’ (or failing ‘general’ policies and priorities, there may be sectoral agreements in place). These amount to agreed Poverty Reduction Strategy Plans or national strategic development plans, which set out policy priorities and strategies and which donors have examined and endorsed. Without these in place, any higher-order modalities are not used: projects are used instead. Secondly, there is an assessment to be made regarding the overall macroeconomic environment and the robustness, capacity and record of economic management by the government, along with, critically, the assessment of ‘public financial management systems’. These involve donors making a judgement regarding the ability of recipient public institutions to manage development processes. Inadequacies at this level can turn attention away from an overall government focus (potential GBS) to more sector-oriented strategies (SWAps) or, if there are doubts at sector level, again projects are the fall-back option. If, however, institutional capacity and transparency are approved of, then a final stage is to consider whether benefits are likely to result from a programme approach, in terms of increased local ownership, cost savings etc. If the answer is in the affirmative, then GBS or SWAps may be put in place; otherwise there is reversion to projects.

A key system that has become established in the process of assessing public financial management is the PEFA (Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability) mechanism. PEFA was established in 2001 by a partnership of seven donor agencies including the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank and mainly European government agencies. It operates within the World Bank. It has developed a standard quantitative methodology for assessing the performance of financial management systems. ‘It identifies 94 characteristics (dimensions) across 31 key components of public financial management (indicators) in 7 broad areas of activity (pillars)’ (PEFA n.d.). PEFA assessments – and a rating score – have become critical for recipients. Assessments are repeated over time to give an indication of progress or not in improving financial management. Over 600 assessments have been conducted since 2005, mostly in the developing world, although Norway completed a self-assessment in 2008. Good scores (such as achieving an ‘A’ grade for key dimensions and showing improvements over time) help convince donors that a recipient government is capable of managing the resources it has and aid it receives. Good scores support the transition to higher-order aid modalities. Commentators have noted that PEFA has become a system that focuses on meeting an external idealised blueprint that does not fit all contexts well and undermines local ownership (Hadley and Miller 2016).

A point to be noted from this decision framework is that, should inadequacies be noted, donors do not simply revert to projects and give up on recipient governments. Instead we can see the importance of capacity-building measures. These aim to increase the capacity (the number of staff and quality of equipment) and capability (the skills of staff and quality of leadership) of government institutions. Training becomes crucial. Donors will support training through measures such as scholarships for tertiary study abroad or in-country programmes to teach particular skills and approaches. To a large extent this capacity building amounts to an alignment of recipient staff and institutions to recipient systems and ways of working.2 Another feature of this framework is that much of the progression through the process is predicated on trust: can donors trust local systems and officials to work effectively, transparently and within acceptable levels of risk. In particular, they ask questions regarding ‘fiduciary risk’: are the aid funds likely to find their target and are they likely to achieve their desired objectives?

The shift away from programmes and the rise of retroliberalism

Behind these programme modalities and decision processes, which were being pursued in the first decade of the 2000s, lay the Paris Declaration of 2005. As we saw in Chapter 4, this agreement was brokered by the DAC and aimed to improve aid effectiveness. Its key principles – ownership, alignment and harmonisation, in particular – took overt control of the aid process away from donors and instead stressed the importance of recipient-‘owned’ development. Donors would respect and work with recipient institutions and systems (as long as they met recipient standards). The targets for achieving these principles also reinforced the transition to higher-level modalities. They involved goals such as the move away from tied aid and the use of local procurement systems. The Paris Declaration thus set the foundation and principles for the move to programme modalities and, ideally, GBS.

High-level programme modalities, backed by agreements, such as the Paris Declaration and its subsequent iterations at Accra and Busan, seemed to involve a remarkable degree of international consensus regarding what was best practice for aid delivery. It seemed to set an optimistic and forward-looking course for aid, building recipients’ ability to set their development agendas, tackle poverty alleviation on a large scale and, eventually, take over the whole process without the need for donor support.

However, as we have seen, the global financial crisis of 2007–08 and political changes that followed undermined this consensus and reversed many of the positive reforms that had taken place. It also brought to the surface some of the doubts that had existed with regard to programme modalities and the neostructural framework. Firstly, donors realised that programme modalities and recipient ownership (together with alignment donor harmonisation) led to a diminution of their ability to exercise influence and control over their aid budgets. Aid had been an important foreign policy tool, used to garner political support and leverage on the global stage or improve economic prospects through trade and tied aid. Instead, with these high-level modalities, donor aid budgets were locked into long-term commitments with little room to manoeuvre, further negotiate or steer them so that benefits could flow back to donor economies.

There were also disadvantages for others. The central relationship with programme modalities was between donor agencies (bilateral and multilateral) and recipient governments. This left less space for civil society. Development NGOs had not been included in the Paris accord in 2005 and had to lobby hard for a recognition of the role of civil society at Accra and to be heard at Busan in 2011. Similarly, though often coming from a quite different approach to aid and development, was the virtual absence of the private sector, particularly in recipient countries. This sector, as with NGOs, had flourished with neoliberal reforms in the 1990s, but felt rather locked out in the neostructural environment. Some donor governments wanted a much more direct role for the private sector – something they pushed hard for in Busan – but this of course meant a weakening of the state-oriented programme modalities being put in place. Finally, there was a concern on the part of OECD donors that other donors, especially China, were not part of the global consensus on aid and that they should be invited to join. At Busan, China observed but decided not to become a signed-up member of the DAC-led approach to aid. The consensus was not complete and, with it fraying at the edges, donors seemed to lose enthusiasm for the Paris-inspired move to long-term, high-level, programme-based ways of delivering aid. In essence it is this set of circumstances that paved the way for the retroliberal regime as we discussed in Chapter 4.

Public-private modalities

Programme modalities did not end with the global financial crisis and the rise of the retroliberal era in aid – in fact most SWAp and GBS commitments continued and some expanded – but as they finished their funding cycles, donors appeared less willing to pit the bulk of their aid resources into these state-centred forms of aid delivery. Instead, they turned to new ways of thinking about how the private sector could be involved in various ways to augment aid activities. This has drawn from wider moves to promote public-private partnerships (PPPs) and there has been a trend to promote these as a way to finance development projects, particularly in the infrastructure sector (Romero 2015; Schur 2016).

The trend towards more public-private collaboration in aid funding has occurred alongside the rise of new discourses and methodologies for aid management. One example is the use of ‘value for money’ (VfM) approaches. These put much emphasis on material and readily quantifiable activities and on stringent scrutiny of costs (DFID 2011a; MFAT 2011). We have also seen a discursive shift to the use of ‘results-based’ narratives, again reinforcing the focus on activities which involve more short-term, physical and measurable outputs. Under these rubrics for aid funding and management, there appears to be less room for development strategies which focus on long-term qualitative changes, such as attitudes to girls’ education, gender-based violence or acceptance of the ecological value of forests.

New aid modalities have begun to appear though many, as yet, remain in their infancy and few have become firmly established. Currently, the aid environment is characterised by a continuation of the state-centred programme modalities alongside these new and emergent ways of delivering aid and involving the private sector much more explicitly. In this section we examine firstly the international discussions regarding new forms of raising finance for development before we explore four examples of the way private sector partnerships are evolving.

Unlike the neostructural period and the focus on programme-based aid, the retroliberal period has not had the same level of open global discussion and agreement. There is no equivalent to the Paris Declaration of 2005 to serve as a set of guiding principles to which most donors and recipients are signatories. However, in 2015, an international meeting was held in Addis Ababa which explored the issue of financing for development (United Nations 2015a). This meeting did not result in a clear set of approaches or binding recommendations, but it did open the door to a wide range of funding options in the future. It turned attention away from simple state-state transfers and instead called for more diverse forms of funding involving donor agencies, recipient governments and the private sector (both local and global). The Addis Ababa meeting, then, is notable not for what it achieved in terms of clear guidelines but more in the way it marked a shift in thinking towards wider and more fluid partnerships between the public and private sectors. We now turn to some of these emerging new modalities for aid financing and delivery.

Private contractors

Private contractors have long been used by government aid agencies to deliver aid. They help reduce overhead costs, especially the cost of permanent head office staff, by shifting them to fixed-term contracts, and they limit the extent of government direct involvement (and, some might argue, responsibility for failures) in projects. Contractors are not bound by the same rules as government agencies (for example, they may pay their chief executives well above government salaries!) and they may be more nimble as a result. Although private contractors have been used for many years, it appears as if their use has been increasing, particularly by USA and UK (Roberts 2014).

USA is the world’s largest ODA donor and by far the largest user of private contractors (Roberts 2014). About a quarter of the US aid budget in 2016 was channelled through for-profit firms and this share has risen appreciably since 2008 (The Economist 2017). For USAID most contracts are tendered on the basis of ‘indefinite quality contracts’ (IQCs) which provide multi-year funding typically to large contracting firms, who may, in turn, use subcontractors on IQCs (Villarino 2011). In 2016 some $US4.68 billion of aid went to such contract funding and, of the top-20 contractors, only one (Kenya Medical Supplies Authority) was based outside USA. The largest contractor, Chemonics International, received over $US 1 billion in 2016 and works in 70 countries on a wide variety of projects and sectors (Orlina 2017). Along with other large for-profit companies, such as Tetra Tech Inc, DAI, Abt Associates and AECOM, Chemonics forms a very large network of US companies that depend on the American aid budget (Table 5.1). In the UK, where 22 per cent of UK’s bilateral spending went to private contractors in 2015–16, the use of contractors has risen sharply in recent years and some ten leading companies account for half of all contracts (The Economist 2017). It is also noticeable in Australia where firms such as Cardno are used increasingly by the government.

Aid contracting can be seen as a means for aid funders to ensure that their budgets are spent efficiently at arm’s length by contracted organisations. They reduce the need to maintain large government aid agencies and they are manageable in terms of accountability and fixed commitments through the mechanism of legal contracts for delivery. Furthermore, the established consulting firms are well known to USAID and have close and trusted working relationships. Yet the contracting arrangement also helps channel very large shares of the international aid budget back to the donor’s own economy. Contractors are usually involved in providing technical expertise or training (rather than the expensive physical hardware of development) so, although they provide advice and management services for aid deliveries to recipient countries, their salaries and fixed costs are spent in Washington DC, Maryland, Massachusetts or California (Roberts 2014). Although contracts are let through a competitive tendering process, in practice it is large Western firms who are best able to file the complex and expensive bids, and thus, using these contractors ‘ties’ development aid back to the donor economy.

Furthermore, the nature of contracts and the reliance on technical assistance programmes, means that aid delivered in this way marks a trend back towards project modalities: fixed-term, tightly managed by the donor (or donor contractor), a focus on pre-determined outputs and with limited engagement with, or attempt to build the capacity of, local institutions.

Name |

Location of Headquarters |

USAID Funding in 2016 |

Chemonics International, Inc. |

Washington, D.C. |

$1,009,133,442 |

Tetra Tech, Inc. |

Pasadena, California |

$471,061,443 |

DAI |

Bethesda, Maryland |

$343,817,396 |

Abt Associates |

Cambridge, Massachusetts |

$154,737,381 |

AECOM |

Los Angeles, California |

$148,843,815 |

Creative Associates International |

Washington, D.C. |

$146,245,498 |

Partnership for Supply Chain Management |

Arlington, Virginia |

$136,215,632 |

Kenya Medical Supplies Authority |

Nairobi, Kenya |

$122,652,321 |

FHI 360 |

Durham, North Carolina |

$100,463,745 |

RTI International |

Research Triangle Park, North Carolina |

$95,373,963 |

Source: Orlina (2017)

Public-private consortia

Another approach by aid agencies with regard to involving the private sector has been to act as a ‘broker’ in building partnerships in aid projects. Donor governments may still provide the bulk of the funding but, rather than simply disburse the funds to recipient governments, they attempt to bring together different parties to form consortia, each bringing different advantages and functions. Thus, for example, they may seek to involve a development NGO because of their ability to liaise with local communities, they may bring on board a local government department to help ensure public services are aligned, and they will want to have private companies involved often as the (commercial) providers of new services or hardware. In a way, this approach harks back to the old approach of integrated rural development: donors help build and co-ordinate a variety of institutions and projects to work together around a central activity.

One example of this approach is the UK’s ‘Invest Africa’ programme (DFID 2017). This foresees FDI as the leading instrument for development: ‘Invest Africa aims to address the barriers to significantly increase Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in manufacturing sectors in Africa in order to help drive the creation of more, better and inclusive jobs in key focus countries’ (ibid: 2). The UK aid programme, through DFID supports the programme in four main ways:

‘Investor Engagement: promoting awareness of opportunities, matching investors, buyers and countries.

Technical Assistance: flexible technical assistance … to strengthen policies, institutions and capacities to attract and retain increased FDI in manufacturing.

Political Engagement and Policy Dialogue: Policy dialogue, raising awareness of potential investments and the binding constraints to realising investments, enhancing political commitment to economic transformation through FDI.

Coordination, influencing and knowledge management: Promoting the overall objectives of Invest Africa, while crowding in and leveraging in additional funds, influencing strategic partners and programmes...’ (DFID 2017: 3).

This example shows how aid is being used actively to help promote and augment private investment (foreign and domestic) and help ensure that it has support from recipient states. The resources of the aid budget and the discourses of development (‘the economic transformation needed in Africa to create more and better jobs for the future and set countries on a trajectory out of poverty’ – ibid: 3–4) are openly being used to support and subsidise the commercial interests of British companies investing in Africa.

Public-private consortia involve a mixing of different discourses of development. They may appeal to conventional notions of well-being and poverty alleviation (improving literacy, access to health services, roads or electricity), but this is usually alongside an articulation of the centrality of economic growth in the development process. Similarly, there is much more rhetorical use of the way small- and medium-sized enterprises, and the involvement of more people in market transactions, help build economies. This seems to emphasise the need to support and expand the private sector within recipient countries. Yet, as with the use of private contractors, the reality is of using donor-based larger private companies as the key agents of economic growth.

These consortia can also be seen as an expansion of the private contracting approach. Here, rather than just disbursing aid funds to private companies to deliver aid projects, donor agencies do more than this. They can undertake the feasibility studies and meet other early stage costs that prepare the ground for later private sector involvement. They also build a set of relationships that support the operation of private companies. The experience of the donor government agency, where aid is seen as part of a broader mission to promote national interests through trade and diplomacy, is used to bring together different parties in a set of joint activities. Public agencies – and NGOs for that matter – are often better suited to this sort of relationship building because of their long-standing involvement and relationships in developing countries, whereas private firms do not usually have the same level of experience or networks into communities, government agencies or even local businesses. So, consortia can be seen as donor support for the private sector through aid project funding plus relationship brokering (Box 5.2). These can be of significant benefit to foreign companies seeking to expand their operations in the Global South.

The use of consortia, then, represents a new and innovative approach to donor aid funding. The role of aid agencies is to provide much of the basic funding, but then use its networks with NGOs, recipient governments and its own private sector to broker large-scale agreements that typically involve a range of projects. Much of the funding ends benefiting donor country companies – and may help promote their efforts to expand their operations in developing countries – but it is done in the name of bringing development benefits to the poor. Again, we see a reversion to project modalities and a relative lessening, but not elimination, of the role of recipient governments. Private sector growth is the main priority and whilst this may involve some local enterprises, donors are keen to back companies from their own countries to do business overseas.

Such ways of operating, as these consortia do, also changes the way aid and development are portrayed. Private companies wanting to do business and make profits do so when economies are expanding and where local institutions (and things such as law and order and protection of property rights) are secure. They do not work so well when there is extreme poverty (people do not have money to spend) or governance is weak. So, although there is some use of poverty narratives to justify aid spending, the rhetoric of development has tended to shift in subtle ways to emphasise growth and prosperity in local economies and support for expanding local economies rather than alleviating extreme poverty.

‘Blended finance’: development impact bonds

A third, and as yet rather untested, mechanism for building PPPs for aid delivery involves the use of private investment to underwrite development interventions. It is ‘blended finance’ because it sees private capital (from investors or philanthropists) being used to fund an activity, whilst donor funds (either private or public) are only paid out to repay and reward the investors if the project succeeds. Development Impact Bonds (DIBs) draw on the model of social impact bonds in places such as USA and UK where several parties are drawn into an intervention to secure a defined social goal (Fraser et al. 2018, Berndt and Wirth 2018). They are ‘another example of the development community’s pivot toward results-based financing and greater private sector engagement’ (Glassman and Oroxom 2017). At the macro level, a public agency will reward an agency (an NGO or a government department) if it oversees a project that brings about positive change as indicated by certain pre-defined measures. This might be an increase in the number of girls attending school or a lowering of prisoner recidivist rates, for example. This is termed a ‘pay for success’ approach with the donor agency only paying for the intervention if it succeeds in meeting its targets. In theory, the provider is incentivised to be flexible and innovative in order to achieve the results (rather than focus on activities and managing inputs). The interim funding for the implementing agency however is provided by bonds taken out by private investors, usually through the intermediary of a financial company or bank. These investors will only receive a repayment of their investment, and a healthy premium, if the targets are met. If they are not, they lose their money and the donor does not pay up. In effect, they are ‘investing’ in a gamble, putting faith in the ability of the implementing agency to do their job. Investors may be motivated by social concern – feeling good about supporting a needed form of social development – or they may simply see a good opportunity for profit.

The social impact bond model has been extended to DIB though these are not yet common. In these we have the donors (they can be a donor agency – government or NGO), the implementing agency (a local NGO or a local government agency), the investors (usually foreign) and the financial intermediaries (companies which design the schemes, manage the bonds and monitor the performance – all for a set fee). Donors only pay if the development interventions are successful, implementing agencies have a strong incentive to achieve success so they secure future contracts, investors will gain a profit if the project succeeds, and the financial intermediary will draw its commission whatever happens. One of the first DIB schemes was ‘Educate Girls’ in Rajasthan, India. This was launched in 2015 and aimed to improve education (in terms of enrolment and retention) for 15,000 pupils. It involved an investor to pay the upfront costs, a service provider, an outcome payer (the Children Investment Fund Foundation) and an independent evaluator. After two years, the scheme appeared to be well on the way to meeting its targets so the investor would recoup their funds and the outcome payer would pay for a successful outcome (Loraque 2018). Gradually we are seeing further examples of DIBs being established (Box 5.3) though they are not yet large in terms of total volumes of aid.

DIBs can be seen as a financial product. They attract investors to finance development activities – thus this is seen to broaden the base of financing for development. Yet, in practice, all they are funding are the working costs of the project and bearing the risk. Donors still pay for the development activity but are now in a way paying more both to cover the premium to investors (in recognition of the risk being borne by them) and the commission of the intermediary. Furthermore, implementing agencies continue to do their jobs, now just reporting to a new paymaster (often with strict conditions and targets). Another implication of DIBs is that they take aid modalities back to project-based activities with defined time frames and quantifiable outputs. They eschew the longer-term programmes of change that may involve more qualitative changes (such as advocacy or attitudinal transformations) and they do not involve wider recipient government involvement as programmes do: governments are put in the role of contracted service providers, not ‘leaders’ of development strategies and nation-wide changes.

Viability gap funding

Finally, we can identify a fourth public-private aid modality that is emerging in recent years. This sees donor governments directly subsidising the operations of private companies through what has become known as ‘viability gap funding’ (VGF). This approach, which seems to have developed particularly in India in relation to PPPs for infrastructure development, rests on the assumption that private companies should fund certain development activities (such as the construction of roads) that will have distinct development benefits, but their decision to invest may be negatively swayed by an assessment that their profit margins may not be sufficient nor secure enough. There is, for them, a gap in the viability of their investment. This gap can be filled by a sympathetic donor who can see that a subsidy for the private company would make the project viable. Projects that are economically – or developmentally – justified, but not financially viable are made viable by government assistance (Schur 2016).

This approach represents perhaps the highest level yet of direct use of aid funds to support the private sector. In this, donors regard private companies as key drivers of development, providing goods and services, generating employment and involved in major development projects, such as infrastructure (Box 5.4). But they also recognise that private companies face risks and uncertainties. If these can be reduced, then viability gaps can be closed and investment secured in circumstances where, in the past, it might have decided not to proceed. In short, aid is used to bolster the profitability of private investment so that economic benefits (employment, growth, better services) can trickle down to the local population. It represents a significant shift in the locus of development: rather than committing to partnerships with recipient government agencies, through SWAps and GBS, to large-scale and long-term development programmes, VGF has moved aid relations to the investment decisions of private companies seeking profit in developing countries, helped out by their supportive governments.

An example of this type of approach, even if not directly identified as VGF, is the OPIC, ‘a self-sustaining U.S. Government agency that helps American businesses invest in emerging markets’ (OPIC 2017). OPIC has been operating for nearly 40 years and it ‘provides businesses with the tools to manage the risks associated with FDI, fosters economic development in emerging market countries, and advances U.S. foreign policy and national security priorities’ (ibid). It charges fees and operates as a lender of capital (as in the Cameroon Cataract DIB – see Box 5.3) and thus raises its own revenue, not drawing on government aid funding. It does, however, fit well with these new modalities, showing a willingness of donor states to support the operations of their own private sector to do business in the developing world in the name of both ’development’ and (donor) self-interest.

A more explicit use of VGF is by the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG) ‘a multi-donor organization with members from seven countries (Australia, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom) and the International Finance Corporation of the World Bank Group’ (IISD n.d.). PIDF will grant up to $US 3 million in VGF per project. ‘It targets pro-poor infrastructure projects that are economically viable in the long term but require initial funding for commercial viability and acquisition of private sector investments’ (ibid).

The VGF approach might be understandable in efficiency terms if there was a transparent and competitive process for funding, as there seems to be in the PIDF process. Donors would fund whichever company on the open market could prove they were most likely to meet the development objectives of their investment and which had the smallest viability gap to fill. In some cases, this may be partly the case, for example when the Government of India will assist local companies, following a competitive bidding process, to undertake infrastructure projects. However, we are beginning to see the approach being used by Western donors in relation to support for companies from their own countries to do business overseas (such as, in part, the UK’s Invest Africa programme – above). It seems that if a narrative can be constructed that such private investment will bring development benefits (such as employment generation or better services), but it is not yet financially viable, the donor VGF can be used to tip the balance in favour of the investment. Aid funds are used to subsidise donor country private investment and enterprise in developing countries.

Conclusion

In this chapter we have examined different modes of delivery of aid from projects to programmes to PPPs. Until about 2008, it was tempting to see a progression in modalities, a realisation that a steady and considered transition from projects to programmes (SWAps then GBS) represented an improvement in aid and development effectiveness. Best practice and the lessons of past failures seemed to point to the need to work with local institutions and let them take the lead and ‘own’ the development strategies that aid supported. Also, it was recognised that aid needed to ‘scale up’, to adopt longer time frames and consider long-term development outcomes, rather than focus solely on producing concrete and defined outputs over a limited project cycle. Aid should support country-wide programmes of change to have broad impact and really tackle macro-scale issues such as poverty alleviation, not just worthy local projects that had limited impact nationally.

However, this assumption of progress in aid modalities and practices has been overturned by changes to modes of delivery in the past ten years. The desire of many donors to retake control over the process of aid delivery (rather than leave it recipient governments) and use it to promote wider national interests, including the support for their own private sector, has seen a return to lower order modalities and much more complex relationships amongst governments, civil society and for-profit businesses. The conversation regarding aid delivery has changed markedly and there has been a shift away from global-level agreements that provide direction for these relations, as was the case in the 2000s following the Paris Declaration.

These new forms of PPPs in relation to aid are characteristic of the retroliberal approach to aid. They see aid donor governments using the aid budget to promote the interests of their own private sectors in the name of ‘doing development’ and assisting developing countries. They play very much into the retroliberal narrative of ‘shared prosperity’ and are a part of the trend towards financialisation of aid. As we move along the scale from the use of private contractors, to consortia and impact bonds to VGF, we see an increasingly explicit subsidy and support for the private sector. There is a move to more ‘supply-led’ aid; aid that is constructed on the basis of what donors (and their private sector) can and want to achieve in partner countries, rather than in response to the requests from those partners. Furthermore, as these private-public mechanisms for aid continue to evolve, we see a further retreat from programme modalities back to projects as the main vehicle for aid delivery.

Therefore, rather than assume that aid delivery will or should simply follow the signs towards better aid practice and more effective development through the use of higher-order modalities, we should accept that the different modes open to donors will all be used in different ways and at different times, depending on the current political and ideological climate. Furthermore, there has been no simple replacement of one dominant modality by another as we shift from one aid regime to another. During the neostructural approaches of the early 2000s it seemed as if there would be a move up the modality scale as projects gave way eventually to budget support. However, this has not happened and has been partially reversed. Modalities overlap in time and space. Budget support remains a very important mechanism used by several donors and is favoured by most recipients; similarly, projects remain as the staple mode of operation for many agencies, especially in civil society or where there is not a strong relationship of trust between donor and recipient. What has happened in the past decade, however, is the emergence of new modalities – not yet dominant by any means – that may signal a new direction for aid operations; modalities which seek to combine public and private finance much more than in the past.

Summary

Modalities are set of modes of practice that are utilised in the delivery and application of aid funds.

There exists a range of modalities that vary from lower-order to higher-order approaches. At the extreme of this continuum are projects and general budget support, respectively.

There are a number of modalities that exist in between these two extremes and combine elements of projects and programmes.

Lower-order modalities, centred on projects, bring both costs and benefits. They are discrete, have specific objectives and an end date. On the other hand, they are not long-term enough to tackle the deep-seated roots of poverty and underdevelopment and often by-pass governments.

Higher-order modalities are longer-term. They include SWAps, GBS, as well as debt relief. The former two became common in response to the rise of the MDGs targets and the Paris Declaration and focus on aid ownership and effectiveness.

SWAps involve sectoral approaches where control is handed to recipient governments over time. GBS is considered the optimal form of aid where governments have the most control over budgets and their disbursement.

Humanitarian relief accounts for approximately 13 per cent of ODA at the global scale. Humanitarian aid arises when there is a disaster or an emergency, and essentially become project-focused in terms of their methodology.

Such disasters are often not ‘natural’ – although such things may precipitate an emergency. Humanitarian crises often result from more profound underlying causes – such as conflict, inequality, non-sustainability – all of which have political causality.

There has been a shift recently in terms of the most common modalities. Neostructural approaches favoured programmes and longer-term approaches. The retroliberal shift has seen the rise of new project approaches based on private-sector investments.

Public-private modalities have accompanied the rise of retroliberal aid. These include private contractors, public-private consortia, blended finance, and VGF. These place more control in private hands and have been accompanied with a shift to narratives involving ‘prosperity’ as opposed to poverty reduction.

Discussion questions

Define an aid modality and give examples of lower- and higher-order modalities.

What are the costs and benefits of project modalities?

What are the costs and benefits of programme modalities?

To what extent are humanitarian disaster natural disasters? What role do politics and deeper development challenges play?

Discuss and explain the difference between modalities applied in the neostructural and the retroliberal aid regimes.

How has the narrative accompanying aid shifted with the move to public-private modalities and how can this be criticised?

Websites

PEFA: pefa.org/about

Notes

1 The terminology used in the project management field varies. Many use the four-step initiation/planning/execution/closure framework. Here we also employ the identification/design/implementation/evaluation terminology, often used in development work. We also add the feedback loop through monitoring and evaluation to portray the idea of a cycle where lessons learned are applied to later projects. The addition of the outcomes/impacts element is to illustrate how the longer-term effects of a project are critical, but usually not well incorporated in the project cycle approach.

2 This is rather a mirror image of the Paris principle of ‘alignment’ which calls for donors to align with recipient government systems and strategies. In practice, capacity building sees local institutions fall into line with donor systems.

3 This story rather glosses over the dubious and contested promotion of the health benefits of providing infant milk formula – milk powder is a leading export product of Fonterra and much is turned into infant milk formula.

Further reading

European Commission (2018) Budget Support: Trends and Results 2018. Directorate-General, International Cooperation and Development, European Commission, Luxembourg.

Koeberle, S. and Stavreski, Z. (2006) ‘Budget support: Concepts and issues’, in Koeberle, S., Stavreski, Z. and Walliser, J. (ed), Budget Support as More Effective Aid. World Bank, Washington DC, pp. 3–27.

Reinikka, R. (2008) ‘Donors and service delivery’, in W. Easterly (ed.), Reinventing Foreign Aid. MIT Press, London and Cambridge, MA, pp. 179–199.

Roberts, S.M. (2014) ‘Development capital: USAID and the rise of development contractors’, Annals Association of American Geographers 104(5), 1030–1051.