4Trends in aid

Learning objectives

This chapter will help readers to:

Understand the history of contemporary aid patterns and colonial antecedents

Define the concept of an aid regime and its component modalities

Distinguish between the various aid regimes that have characterised the aid sector since 1945

Appreciate the background, theoretical underpinnings, key agencies, policies and practices, modalities, and effects of successive aid regimes

Critically appreciate the overlaps and interactions within and between the aid regimes discussed – modernisation, neoliberalism, neostructuralism and retroliberalism

Introduction

Having examined the way aid flows over space, with flows between the myriad of donor agencies and recipient states and organisations, we now turn to the ways these flows have changed over time. Although we might see aid as a relatively straightforward concept, involving the assistance offered to promote the economic growth and welfare of people in the developing world, in fact, ideas regarding why aid should be given, where it should go, how it should be delivered, and in what form, have changed markedly over time. This has resulted from changing conditions in the global economy, from changing global geopolitics and also from changing concepts and theories about what development should be and what role aid can play in this.

In this chapter we trace changes in aid thinking and practice over time and one way we can summarise and categorise these changes; through the concept of ‘aid regimes’. We concentrate on the period after 1945 and on postcolonial settings, though we begin by looking at some colonial antecedents for models of aid and the consequences of these.

Aid over time: changing trends and common concerns

Although in this chapter we emphasise change and the evolution of different ideas, we should note at the outset that there are also some important consistencies over time. Firstly, it is notable that aid has been a remarkably constant feature of the global economy and global politics for the past 60 or more years. Rarely has it been suggested that aid should end altogether or be reduced substantially so that poorer countries should just fend for themselves. Aid seems to be a relatively permanent fixture in the theory and practice of global geopolitics. Secondly, a consistent, if not always transparent, thread has been that aid brings, and should bring, some benefits to donors as well as recipients. This view sits uncomfortably with many who support the altruistic concept of aid but the political realities are such that donor countries cannot readily sustain a large aid programme simply by telling their constituents that they are ‘doing good’ for those overseas, when there are many pressing needs for state funding at home. Perhaps of greater significance is the fact that political leaders in the Global North see that aid budgets can be used creatively to support wider strategic, diplomatic and economic goals of the donor country itself. As such, aid has become an integral instrument of foreign affairs and economic development rather than simply a separate and solely philanthropic activity. Aid is, and nearly always has been, about self-interest as much, if not more than it has been about altruism. Finally, a consistent element of aid is that its allocation is not determined by any sort of dispassionate assessment of need – it does not automatically go where it is needed most. Rather, as was discussed briefly in earlier chapters, its allocation is determined by a complex web of historical, political, diplomatic and strategic considerations that are rarely transparent.

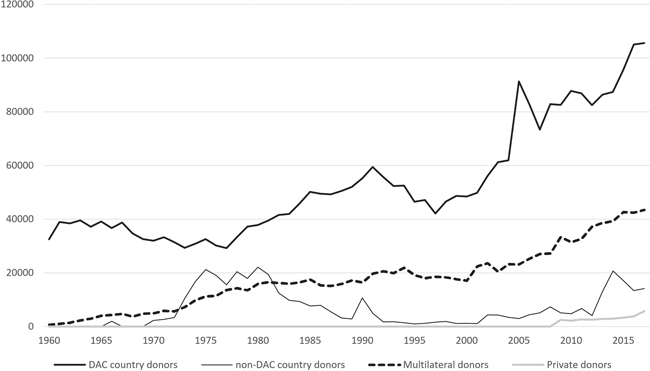

To set the scene for this discussion, we can see how aid volumes have changed over the past 50 years (Figure 4.1). This recaps and summarises the discussion we undertook in Chapters 1 to 3. The figure shows flows of Official Development Assistance (ODA) in constant ‘real dollar’ amounts (allowing for inflation) using data defined and collected by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), though we should bear in mind the changes in the way ODA has been measured as well as the range of donors and recipients over this time period (Chapter 1). Moving through the periods, there seems to have been a gradual fall-off in ODA from the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) donors from the later 1960s to the late 1970s but a big increase from non-DAC donors from the early 1970s. These non-DAC donors at the time were mainly Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, both with large surpluses to expend following the dramatic increases in the price of oil during the decade. Throughout the 1980s ODA increased from the DAC donors (with declines from non-DAC donors), but then there was a reversal in the first half of the 1990s followed by some stabilisation and slight increase until 2000. Thereafter, a notable and steady increase took place until 2011, with a spike in 2005 coinciding with the Southeast Asian tsunami. In the last four years prior to 2017 the increases have continued and we have seen the appearance of new donors (the ‘others’ here being new private donors, principally the Gates Foundation). Overall, the DAC donors and the large multilateral organisations dominate ODA and only recently has the non-DAC group begun to increase its relative share (apart from the noted big contributions in the 1970s).

Figure 4.1 ODA disbursements 1966–2017 ($US mill constant $ 2017)

Source: www.stats.oecd.org

Figure 4.1 gives us the basis for the framework of aid ‘regimes’ we explore below – though as we will see common themes, together with the different unfolding of these regimes in different places, means there is overlap and different regimes may co-exist in time and space. The concepts employed here, of neostructuralism and retroliberalism especially, are characterisations that we favour in order to document and categorise historical changes in aid. We suggest and discuss four ‘aid regimes’ in the remainder of this chapter. Firstly, there is the long period of modernisation up until about the mid-1980s, though elements of colonial development funding persisted into this period for a number of countries not yet independent and neoliberal influences began to be felt through aid prior to 1990s. Neoliberalism then held sway during the late 1980s and 1990s with early structural adjustment programmes and a move away from state-led development. The neostructural regime, marked by the launching of the MDGs in 2000 then accounted for the increases in aid in the first decade of the new millennium, whilst the period since the global financial crisis of 2007–08 is what we term a ‘retroliberal’ phase, still with aid increases but, as we will see, some fundamental shifts in the types and practices of aid. Before we begin this discussion it is necessary to outline the precursors and roots of aid during the colonial period.

Colonialism and ‘aid’

The origins of aid are usually seen to lie in the post-1945 environment of decolonisation and the Cold War. We saw in Chapter 1 how President Truman’s inaugural address in 1947 laid out the rationale for a new postcolonial development age. However, we can see within the colonial period, and especially in its later years, some important elements that came to characterise the way aid was delivered subsequently and its rationale. We look at these briefly before analysing in more depth the change in subsequent ‘aid regimes’ that unfolded with decolonisation.

The empires that the major powers established particularly after the mid-nineteenth century redrew the map of the world so that most of the Global South was tied to the North in some form of colonial relationship. Great Britain, France, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Italy1 had been joined by USA and Japan in claiming territories in Asia, Africa and Oceania. Meanwhile Austria-Hungary and the former Ottoman Empire maintained a hold on territories in parts of Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean, at least until 1918, and the defeat of the Ottoman-German alliance in the First World War.

Such colonies were claimed and held for a variety of reasons, whether strategic or overtly linked to economic exploitation. ‘Development’ in terms of improvements in the incomes and welfare of their inhabitants was rarely, if ever, claimed to be a primary justification for the colonies nor a primary responsibility of the colonial powers. To the extent that it was even considered, it was assumed that colonial development, involving the growth of cities, railways and ports and the founding of economic industries (usually in hands of foreigners), would bring peace and, eventually, economic well-being to local people.

That approach changed after 1945. Although independence movements had been present in many colonies prior to the Second World War they were seen as being of relatively minor consequence and it was assumed that colonial rule would persist for many generations into the future. However, the destruction and evident weakness of European powers after the war meant that they could not easily re-establish their control. Local people would not readily accept that colonial rule should return and this was especially the case in Asia, where European control had been temporarily replaced by Japanese occupation. The rise in nationalist movements, pressure from the United States and later the United Nations (which strongly reflected the growing superpower’s concerns and agendas) and political realisation at home led many Europeans to accept that the days of the old colonial order were numbered and that preparations for their independence should be made rapidly. Such a change of heart was perhaps best exemplified with regard to Africa by Harold Macmillan’s ‘winds of change’ speech in Cape Town in 1960. India and Pakistan had become independent in 1947, wars of liberation were waged in French Indo-China, Indonesia had dispensed with Dutch rule, and there were major forms of resistance to British colonial rule in Kenya and Malaya. The tensions between the capitalist US-led West and the communist USSR-led East and the ensuing Cold War proved a theatre for the playing out of the postcolonial struggles with both sides supporting different regimes. As a consequence, the resultant ‘aid’ patterns were strongly ideologically-driven.

Acceptance that colonialism was coming to an end forced colonial powers to consider strategies to prepare the countries for self-rule, for little had been done before 1939 to develop an educated, outward-oriented and experienced bureaucratic or political class that would take on leadership of independent states. Instead, former strategies of divide and rule had often created or deepened schisms and the veneer of nationhood and modernisation was thin indeed. Firstly, there was a need to invest in education to ensure that there were capable people to fill the civil service and an informed public to make good decisions in new democracies. Colonial rulers needed to accelerate infrastructural development so that national integration was more of a priority than just providing quick and efficient routes to get commodities to export ports. Urban areas needed to be better planned to cater for rapid expansion, and social services, such as hospitals, could help convince people of the value of an effective government system.

For Britain, the post-war colonial development and welfare legislation was critical in this regard because it defined a new rationale for the late colonial period (Cowen 1984). There was a large expansion in colonial staff as the functions of the colonial state grew and extended to many more parts of the colonies. This approach, for the British at least, was partly inspired by post-war Fabian socialism which argued for much more of a role for the state in providing for the welfare of its citizens and this reasoning extended to the colonies.

In this environment, the funding of such ‘development’ came from government coffers, partly the operational budgets of the colonies themselves, but partly also from the grants and loans provided by the colonial powers. These were not labelled as ‘aid’ or ‘ODA’, but in many cases they acted as this: transfers of resources from the metropolitan power to territories where they were spent on welfare and development. In terms of the mode of delivery, such ‘aid’ went directly through government accounts, either as recurrent expenditure (for running schools or hospitals) or as capital expenditure (building roads or irrigation schemes). Thus, we can see that colonial development involved a transfer of funds directly into the budgets of the countries – what we would later call general budget support (GBS). This is an important point to note for it marks the early recognition that important long-term development activities need to be controlled locally by a capable and legitimate government agency.

The colonial development and welfare approach had little time to become embedded and function effectively. Instead, the granting of independence meant that colonial development budgets with their accounting within a colonial framework became the basis for new ‘aid’ budgets and flows. Consequently, what had been metropoles and colonies now became aid donors and recipients respectively. Furthermore, although the timing of decolonisation was often abrupt, the flow of development funds did not end; with independence they often increased. And this established a pattern of aid flows that has persisted: former colonial powers generally became the largest aid donors in former colonies and the geography of colonialism was reworked and re-spatialised to become the geography of aid.

‘Aid regimes’: concept and outline

Following independence and the establishment of aid flows we can then observe a succession of broadly unified approaches to the conceptualisation and application of aid. A broad term we use to describe such entities is ‘aid regimes’. An aid regime exists where there is a general consistency in the practice of aid relations and delivery, as well as a consensus of some nature (even if it is not explicitly expressed) in the motivations and strategies behind the patterns that we observe. In other words, a regime is similar to the concept of a paradigm where philosophy and practice are relatively consistent.2 Whilst many different paradigms might exist at any one time, the term ‘regime’ is used here to refer to that which is dominant at the global scale. In reality, such regimes also vary over time and space. First and foremost, we are referring to aid as practiced largely through the ODA mechanism: the role of the USSR and its satellites in the 1950s–1980s, and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) after 2000 could arguably be considered very different sets of ‘regimes’. Furthermore, change between one regime and another, just as paradigms in development or science shift, is an uncertain affair. We may be able to observe general conditions that lead to the superseding of one by another and we may identify broad patterns as a result, but in reality, the lines are blurred and regimes can co-exist. Notwithstanding these shortcomings, the use of the regime concept is useful and provides a framework for analysis, helping us understand why the direction, volumes, delivery mechanisms and impacts of aid shifts between periods. Elsewhere we have defined aid regimes as a dominant and widely accepted view which: ‘conceptualises and delivers official development assistance and is characterised by a general discourse manifested in a set of guiding principles aimed towards broad goals, combined with regulatory mechanisms which deliver certain objectives’ (Overton et al. 2019: 29).

In the following section we propose and discuss four broad successive aid regimes:

Neoliberal aid regime (c.1980–c.2000)

Neostructural aid regime (c.2000–c.2010)

Retroliberal aid regime (c.2010–present)

The first three regimes above are relatively widely accepted interpretations (especially the first two); the third draws on a term used often in relation to especially Latin American strategies (Leiva 2008), whilst the fourth is a concept we have evolved ourselves in order to describe and explain recent trends and patterns (see Murray and Overton 2016; Overton and Murray 2018; Mawdsley et al. 2018). For the purposes of comparison, we discuss each aid regime under the following headings: background, theoretical underpinnings, key agencies, policies and practices, modalities, and effects.

Modernisation aid regime (c.1945–c.1980)

Background

Early approaches to international development assistance spanned a long period, overlapping with widespread decolonisation and the optimistic early days of newly independent states. It covered a period from roughly 1945 (though for many recipient countries it began rather later than this as they waited for independence) until the early 1980s when neoliberal policies began to take hold worldwide.

Decolonisation was critical in shaping early aid strategies. The partition and independence of India and Pakistan in 1947 (and soon after Burma and Ceylon/Sri Lanka) marked the first steps in what became a rapid and accelerating process of the breakup of old European colonial empires through the 1950s and 1960s. Newly independent states were keen to institute new and progressive policies to undertake rapid economic growth and modernisation. This would demonstrate a break from the oppressive colonial past and illustrate to a recently enfranchised population that their new leaders could deliver the benefits of modernity and prosperity. These new states saw development as one of their main responsibilities and priorities. And from the perspective of donors, particularly former colonial powers, it was important that these new states not fail. They wanted to ensure that independent countries in Asia, Africa and Oceania could adopt economic development paths that matched the models of the West and linked them together in new, postcolonial, ways. Williams (2012) has termed this era the ‘sovereign order’, a period when national states, both donor and recipient, were central to development.

The Cold War then shaped the way donors approached these countries with some enthusiasm. The Soviet Union and, to a lesser extent, China were keen to gain allies in the world and felt they had socialist models of development that could provide a blueprint for independent countries. Although vastly different in terms of control of the development process, socialist development models still promoted forms of change with industrialisation and modernisation, and aid was a key instrument in putting these new strategies in place. Tanzania and Cuba especially turned to these socialist models and received a sharp response and isolation from Western powers as a result. Western donors, especially USA, did not want communism to spread – it was a threat to American business and trading interests and to their vision of an American-centred new world order (as articulated in the inaugural speech of President Truman – see Chapter 1). Western donors, although talking much about aid for development and progress, were quite explicit about their expectation that aid recipients would align with Western geopolitical priorities.

A final background element of this early phase of aid was a strong belief in the power of science and technology. Technology and economic power had won the world war (jet aircraft, atomic bombs, radar and landing craft); now they could tackle poverty. This amounted to a belief that poverty was fundamentally a matter of a lack of resources and that it was amenable to a technocratic solution. Furthermore, there was a strong emphasis on the building industry and infrastructure to lead overall development. This built from the example of the Marshall Plan for the reconstruction of war-torn Europe funded by USA from 1948. Generous funds were made available and Europe soon rebuilt its key infrastructure and reconstructed and modernised its key industries. This success helped keep Western European countries aligned with USA and linked through growing productivity and trade. The Marshall Plan provided a template for international development aid: substantial aid funds could work well when devoted to establishing (or re-establishing) an industrial base for an economy so that it could grow and trade and become more closely politically aligned. Furthermore, Western science and technology, economic models and systems of government and administration constituted the templates for development. Indeed, these notions formed the basis of the Colombo Plan which also served an explicitly Cold War influenced purpose (see Box 4.1).

Modernisation was a ‘think-big’ and technocratic approach: if sufficient funds were made available on a large-scale and modern ideas applied, then poverty could be eliminated. In the 1960s the Green Revolution seemed to vindicate this technocratic approach. Mounting food shortages and the threat of large-scale starvation were averted by the development of new high yielding varieties of rice, maize and wheat which responded well to the application of new (oil-based) fertilisers and controlled irrigation so that two or more crops a year replaced single crops. Technology, it seemed, could control the vagaries and constraints of nature and bring prosperity and security for all.

Theoretical underpinnings

Decolonisation, the Cold War, and a strong faith that poverty could be ‘fixed’ by modern technology and large-scale economic investment provided the context for the early evolution of aid programmes but they were given particular shape and direction by certain theories of development at the time. These theories had several elements: neoclassical economics, Keynesian economics, structuralism and the range of modernisation theories.

Neoclassical economic theories were in vogue in the post-war era. They harked back to their classical origins, particularly the free market views of Adam Smith and the free trade ideas of David Ricardo. Yet these were tempered with a recognition that market failures could occur. It was accepted that forms of state regulation and intervention could be necessary, though mostly it was believed that the state should stay away from direct economic production. A new branch of economics – development economics – emerged during the 1950s and focused on how these different approaches, based on fundamental principles of economics, could be applied to the context and problems of the ‘Third World’ (Hirschman 1958; Todaro and Smith 2015). For example, writers such as W. Arthur Lewis examined the dynamics of growth in economies that had a dual economic structure (a small emergent urban industrial sector and a large and stagnant rural sector) (Lewis 1954).

The experience of the Great Depression had given credence to the theories of John Manyard Keynes. Keynes believed that states could and should intervene in the economy through fiscal policies (raising income and spending in strategic ways) to avoid wild swings in economic fortunes: recession could be avoided by judicious increases in public expenditure when the free market was on a downward spiral. This Keynesian justification for state spending could be extended to suggest that the state could manage the economy, through stimulating economic activity through spending, and ensure full employment and, indeed ‘development’. It seemed to be an economic theory that was ready-made for newly independent governments: they could dispense with old laissez-faire economics and take an active role in economic development.

Taking the Keynesian state intervention line further were the ‘structuralist’ ideas emanating particularly from the UN Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLAC) based in Chile and led by the economist Raul Prebisch (1962). Prebisch and others developed an argument that suggested that peripheral, commodity-exporting countries, were particularly vulnerable to the vicissitudes of the global economy and faced a long-term decline in the terms of trade vis-à-vis the manufactured products they were locked into importing. Instead of open free trade, they suggested a model of import substitution industrialisation (ISI) which involved states imposing trade barriers (in the forms of tariffs, quota and currency intervention) so that local ‘infant’ industries could develop and eventually compete on the world market. This saw self-reliance as a virtue and suggested that development should be oriented more inwardly (desarollo hacia adentro) rather than through unregulated linking to the global economy through free trade (desarollo hacia afuera) (Kay 2011).

As well as the economists, other social scientists had much advice to offer government development strategies and aid programmes. They looked to the way the West had ‘developed’ and become ‘modern’ (even if both terms could be open to question). They suggested that change in the Third World should follow these trajectories and they could do so more rapidly. There were clear economic paths to follow: the widespread development of markets, industrialisation, specialisation, foreign trade and urbanisation. W.W. Rostow went as far as to suggest optimistically that if certain pre-conditions could be met (the development of leading sectors, a rise in the savings ratio etc.), then developing states could achieve an economic ‘take off’ setting a course to continuing and irreversible economic growth (Rostow 1959). Other writers from sociology – Neil Smelser and Talcott Parsons – examined the social and cultural changes that accompanied this process. There was to be a move to individualism away from communalism, the development of urban societies replacing rural kinship structures, merit-based status by achievement would replace (inherited) ‘status by ascription’, and attitudes would change so that the accumulation of wealth was pursued and prized. The final element of modernisation theory was that key institution in the process of change was the emergence of the nation-state. The state would embody the will and identity of the population and lead and manage the process of development. In time a modern, prosperous and rational society would replace old communal and traditional ways that were seen to be trapping people in conditions of backwardness and poverty.

In all, these theories provided a model for development, the achievement of which could be supported and accelerated by international aid. For economists, aid could compensate for shortages of domestic savings and investment funds, and government taxes, and thus provide the resources to undertake large-scale and rapid infrastructural development. ‘Aid’ and ‘development’ became largely uncontested terms with connotations of ‘generalised goodness’ and ‘progress’. This was shared across the political spectrum and was manifested in grand visions such as the United Nation’s declaration of the 1960s as the ‘Decade for Development’. Thus, despite the range of theories – and the emergence of some radical critiques in the form of dependency theory – there seemed to be a strong consensus over several decades that development was needed, it could be achieved by using largely technocratic and economic methods, and aid was a critical tool for achieving it.

Key agencies

The evolution of the aid environment in the 1950s and 1960s began to see the emergence of certain institutions that took the lead in negotiating aid relationships, developing policies and dispersing aid funds. On the recipient side, the nation-state was at the centre. Here the old colonial administrations, which had typically been minimal in size and limited in scope, had to be greatly enlarged and broadened. Governments would take the lead in planning and managing development projects. Yet this required many extra resources. More educated and trained staff were needed, not only bureaucrats to manage the projects, but also research scientists to improve agricultural production, engineers to design roads and irrigation schemes, accountants to keep the books, district staff to work with local communities and so on.

On the donor side, particular government agencies took responsibility for new aid programmes. For European donors, this often involved a transfer of some functions and staff from old colonial departments to expanded ‘external relations’ ministries. Yet there were also instances of separate aid agencies being founded, most notably with President Kennedy’s launch of an integrated United States Agency for International Development (USAID) in 1961. Increasingly, albeit gradually, specialist and experienced aid personnel were to be found within donor agencies, replacing temporary assignments of diplomats and general administrators.

Multilateral agencies were also important. The Bretton Woods Institutions (the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF)) had only been agreed to in 1944 and had much work to do firstly in attending to the recovery of war-torn Europe. The World Bank, in particular, set about providing substantial development loans to recipient governments to undertake large infrastructure projects. The United Nations too – founded in 1945 – soon established a number of sub-agencies. Some of these – the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) – had development as a core function.

At this time civil society was seen to be in its infancy and incapable of taking a leading role. Development NGOs may have been emerging in donor countries, raising funds for their own projects overseas and development awareness more generally but within recipient states, they were typically small in number and size.

Overall, then, the early modernisation phase of aid was strongly state-centred on both sides. States took the lead in promoting development and in negotiating and channelling aid into projects and state budgets. Given this state-focused leadership it is not surprising to note that many of the key relationships between donors and recipients built upon former colonial systems and personnel. Old colonial powers did not quickly disappear. Instead they maintained links and used aid as a way of cementing new postcolonial relationships. In this way the geography of aid was drawn anew but based on a colonial template.

Policies and practices

‘Aid for development’ was the hallmark of the modernisation aid regime. There was strong emphasis on both infrastructure (roads, ports, energy) and welfare (education and health). Infrastructure provided the means for economy to grow and welfare gave people the attitudes and skills to become ‘modern’. Aid assistance was crucial because of the scarcity of local capital.

A major strategy of aid was to build economic (and political) integration. Transport infrastructure could link economic sectors nationally, for example by connecting rural food production locales with urban food and beverage processing industries. In terms of aid for industrial development, a number of structuralist-inspired nationalised utilities and transport industries were supported (such as railways, telecommunications, energy etc.) although aid projects were generally limited in terms of direct support for nationalised industries.

Although modernisation theory pointed explicitly to urban industrial growth as the driving force for development, much aid in practice was devoted to the rural sector. This was partly because, until the 1970s (and beyond), most people in developing countries still lived in the countryside and depended on agriculture. Accordingly, a focus on improving rural livelihoods steered many development projects: irrigation schemes, rural electrification, extension services, rural schools and health centres, etc. As well as improving the welfare and incomes of rural people, they were designed to slow the movement of people to cities as rapid and uncontrolled urbanisation posed a problem for new states. Rural development was thus intended to maintain a social and political spatial order at the national scale.

A final feature of aid policies and practices at this time was the appearance of aid ‘conditionalities’. Given the Cold War geopolitical context, donors wanted to link aid donations to some sort of political and diplomatic return. Rejecting Soviet overtures, hosting Western military visits or bases, voting alongside Western powers in the UN or offering favourable terms to Western businesses to invest in country were all signs of the way these implicit conditionalities operated. Terese Hayter (1971), in relation to Latin America, coined the term ‘aid as imperialism’ as a way of illustrating how the hidden conditions of aid led to two-way flows of resources both to and from the recipients.

Modalities

With policies and strategies referred to above in place, aid was delivered in particular ways and modernisation was associated with particular ‘aid modalities’, which we define here as the channels and processes involved in getting aid resources from donor to end user.

Firstly, we can note that there was hangover from the colonial era for a number of countries following independence. This occurred when donors, as ex-colonial powers, agreed to continue to fund budget deficits directly from their own coffers and into those of the new government. Later this modality would be termed ‘general budget support’ yet at this time it was merely an expedient move to support new governments who struggled to meet the gap between limited local sources of revenue and a mounting expenditure bill. Gradually though, such general support was phased out as donors were reluctant to pour untagged funds into a budget over which they had no direct control.

Replacing budget support were projects. Projects involved a particular framing of development activities and aid. They involved discrete activities of a fixed duration with pre-defined goals and outputs. Projects were popular with donors. They were straightforward to manage, they could be planned and there was a clear completion date (even if they were not always achieved on time or within budget). Funds could be allocated and results could be seen and measured directly. In time, projects tended to be ‘scaled-up’. Larger and larger schemes could bring benefits to a wider area and replication of project templates in different places could have a similar effect. Dams and irrigation schemes became bigger, energy and roading schemes more ambitious and national projects (universities, tertiary hospitals) more prominent. Also, there was a call to integrate disparate projects more effectively. This led to the concept of, for example, integrated rural development schemes, where various projects (water control, electrification, roads, new seeds and mechanisation, rural markets, and training) were planned and constructed together.

Effects

As aid budgets and management systems grew, recipient countries saw many projects spread over the countryside and towns, and despite an end to colonialism, there seemed to be just as many foreigners involved – as donors, experts, engineers, evaluators and project managers. There were many tangible and physical signs of development and there were some significant improvements in numerous countries in terms of services, infrastructure and welfare. But there were also failures and mounting concerns. One of the main issues was increased debt: development loans, albeit on concessionary aid terms, still had to be repaid.

Whilst these problems led many commentators to point the finger of blame at local institutions, officials and politicians, the donor agencies themselves were also culpable. The aim of winning the allegiance of new states as a priority in the Cold War environment meant aid was maintained even when regimes were seen to be undemocratic or corrupt.

Overall, we can conclude that modernisation was associated with the portrayal of development as a shortage of resources and know-how. This had to come from the West and come in the form of aid. Poverty was the public justification for aid but the political and economic interests of donors were always strong, if often in the shadows. The face of aid was the big projects (dams, roads, electricity, etc.) and aid aimed to build a modern economy and society using the template of the West.

Neoliberal aid regime (c.1980–c.2000)

Background

Political-economic and ideological shifts in the West in the late 1970s and 1980s were to have a profound effect on the international aid world in the 1990s. Western donors had pursued a modernisation programme through aid and constructed ways of operating through the 1950s to the 1970s. But abruptly, and without consulting their recipient partners, they were to change these fundamentally. The oil crises of the 1970s had deeply affected Western economies. Facing recession, debt levels had risen and economic inefficiencies had become deeply embedded in their economies. Financial institutions also saw a mounting crisis as developing world borrowers struggled to service their loans.

A political revolution, partly in response to these economic trends discussed above, occurred with the almost simultaneous election of right-wing administrations in the UK (Margaret Thatcher in 1979) and USA (Ronald Reagan in 1980). Both instituted harsh economic reform packages, cutting taxes and public expenditure, deregulating the domestic economy and privatising state-owned enterprises. The original experimental site for neoliberalism had been Chile however, where anti-socialist dictatorship was established through a coup in 1973. The changes in economic policy were also often linked to a new moral conservatism that rejected the view that inequality was a responsibility of the state and instead stressed individualism and enterprise as the way out of poverty. Despite severe economic disruption and rising unemployment, the reforms were pushed forward and this neoliberal approach – promoting the role of market forces ahead of a diminished state – became deeply entrenched in Western economies in the 1980s.

During the 1980s, the Cold War continued to rage and indeed intensified with the USA and UK becoming more assertive against a faltering USSR. In this atmosphere of heightened rivalries and geopolitical paranoia, aid continued – and even increased slightly during the 1980s (Figure 4.1). The West was still very keen to maintain and bolster its base of client states in the developing world. However, the Cold War began to dissolve as the Soviet bloc moved to reform and democratise its systems. With the dramatic fall of the Berlin Wall late in 1989, the old enmities fell also and there was much less need to use aid as a diplomatic tool to keep countries on side. In this environment, aid changed. Firstly, aid levels fell markedly in the early 1990s (Figure 4.1). Secondly, rather than maintaining compliant regimes, aid was used increasingly as a means to export neoliberal policies and the deregulation reforms undertaken in the West in the 1980s spread quickly and profoundly to the developing world after 1990.

Theoretical underpinnings

Neoliberalism may have been backed by politicians but it was foremost an economic theory – some would say an ideology (Harvey 2005). It was associated particularly with the ‘Chicago School’ of economics led by Milton Friedman and their ideas were disseminated widely at a time when old approaches seemed to be failing. Friedman explicitly rejected the Keynesian fiscal ‘demand-side’ approach to economic management which used the state to stimulate demand in times of recession. Instead they advocated ‘monetarism’, using market mechanisms associated with the money supply (the role of market interest rates) to ensure that resources were allocated efficiently and that the correct economic signals were made to ensure necessary changes in investment, spending and employment. It amounted to an essential argument to ‘roll back the state’: diminish the role of the government in economic regulation and leave market forces to ensure that the economy ran smoothly. This was ‘neoliberalism’ rather than ‘neoclassical’ economics because it had a much stronger adherence to the basic economic principles of free markets and free trade and a deeper attachment to moral individualism.

Monetarists believed that states made poor economic decisions because they had to satisfy a political constituency, so key economic policies and institutions (such as national reserve banks which controlled money supply) should be freed from political interference. Economic growth would be the engine of human development and real economic growth was best ensured by letting market forces work freely, not using artificial (state) stimulants. With economic growth, there would be employment generation and, as employment rose, so would wages, and the benefits of growth would ‘tickle down’ to all in the economy. To neoliberal economists, therefore, the market was the best mechanism to alleviate poverty.

Neoliberalism argued that the fundamentals of economic policy were the key: if the market was functioning properly, then there was no need for governments to have development plans or try and engineer social and welfare policy. There was no particular vision, as with modernisation, of a desired future. The market would take care of everything!

Keynesian intervention was rejected and it was believed that reforms should take place rapidly and without delay. It was conceded that there would be short-term dislocation and some hardship but there was faith that people would respond quickly to the new market environment and confidence and growth would soon return.

The proponents of neoliberalism first set their sights on reform in Western economies but soon turned attention to the global economy together with the question of development and aid. Here there was a portrayal of underdevelopment as the fault of the poor and particularly of their governments and corrupt politicians. Political reform was seen as critical for the developing world. In addition, aid was seen as a contributor to underdevelopment rather than development. According to neoliberals, it helped build and support bloated bureaucracies and interventionist and inefficient economic policies. Therefore, aid had to be cut and/or used as a way of forcing change. Aid could be a means to export the neoliberal recipe to the developing world through imposing new conditions for countries that received assistance. There was a view that ‘we’ (in the West) had reformed our economies, now we will tell you how – and ‘encourage’ you – to reform yours in the same manner. In practice also the opening of developing economies would bring great benefits for the capitalist West in terms of locations for investment, markets for exports and sources of natural resources.

Key agencies

Just as neoliberalism changed economic policy radically it also led to a re-drawing of the aid landscape in terms of the institutions involved. Modernisation had put the nation-state at the centre; neoliberalism installed the market in that position. But to institute that change, certain agencies became associated with leading the neoliberal reforms.

The key bilateral donors – the USA and UK in particular – were keen to bring about radical reform in aid but they could not do it alone. They found ready allies in the Bretton Woods Institutions – the IMF and the World Bank – whose boards and senior staff were appointed by the main donors. This small group of agencies, centred on the IMF, the World Bank and the US Treasury became the leaders of change and formed what was known as the ‘Washington Consensus’ – all had their headquarters close together in Washington DC and all agreed on what changes should take place. The IMF and World Bank were able to take on a lead role because many recipient countries were facing severe debt problems in the 1980s – a result of borrowing heavily in the 1970s when easy credit was available and before the oil price hikes and a recessionary debt crisis took hold. Now they were threatened literally with bankruptcy, unable to service or repay their loans due to the dual effects of high interest rates and a global downturn. Both of Latin America’s largest economies, Mexico and Brazil, defaulted in the early 1980s and made this fragility starkly clear. The desperation of borrowing countries who had been lent to under low interest conditions was seized upon and creditors agreed help them out but only if they accepted a strict agenda for reform. These were the infamous ‘conditionalities’ that forced them to introduce Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs – see below). The IMF and World Bank (and other regional development banks such as the Asian Development Bank) were crucial here and they were then supported by the key bilateral donors who reinforced the need for change, using their own pressures and aid policies to force reform.

Whilst the Bretton Woods multilateral agencies were prominent, other multilateral agencies became less prominent, in particular the United Nations. Indeed, we could say that the centre of power shifted from New York (the headquarters of the UN) to Washington DC. The UN after all was not governed by a small number of big donors (as was the World Bank and IMF) but by a much broader base of country votes. Furthermore, UN agencies themselves came under attack. The US Reagan administration withdrew funding from UNESCO when it disagreed with its strategies and leadership, for example. Other UN agencies felt the pressure and gradually fell into line with the reform agenda, though the UNDP did continue to highlight the effect of reforms on increasing levels of poverty through the 1990s.

The Washington Consensus therefore opened the space for the private sector to have a much more prominent role in development processes, not directly in terms of undertaking projects or deciding policy or receiving subsidies, but instead simply being given fewer restrictions and more room to operate freely with minimal regulation. Privatisation also created new opportunities for private companies to operate and provide services that were previously the responsibility of government.

The state, particularly recipient states, on the other hand, faced severe restrictions and enforced downsizing. There were reductions in the functions of the state as state-operated services and industries were privatised, there were large cut-backs in the size of government departments as many public servants lost their jobs, and the ability of the state to regulate the economy was severely curtailed.

By contrast, the space for civil society involvement widened considerably during the neoliberal era (Agg 2006). Donors were reluctant to fund state-run welfare services but this vacuum could be filled by NGOs who were seen to be closely connected to local communities and in touch with their needs. NGOs became, in effect, sub-contractors to the donors, running projects for them on the ground. Their concern for community-level welfare also meant that they could help address some of the casualties of neoliberal reform, those who had lost their jobs or access to government services. The number of development NGOs increased markedly worldwide during the 1990s as did the volume of aid money going to the NGO sector.

Policies and practices

The neoliberal aid regime involved using aid as a tool for economic reform. Aid for development was not a key priority as it was assumed that if the economy functioned well, development would take care of itself. In addition, there was to be a ‘short sharp shock’: measures would be introduced rapidly and simultaneously. The state would be rolled-back, the market ‘liberated’ and then economic growth would follow, supposedly bringing benefits for all.

The dominant policy prescription was the package of measures wrapped up in Structural Adjustment Policies (SAPs). SAPs ostensibly involved the same range of measures that some donor countries had instituted themselves in the 1980s though in many cases the changes were brought about more rapidly and cut more deeply into the state apparatus. Furthermore, despite the use of conditionalities to force recipient countries to liberalise and demolish their own trade barriers, many aspects of protectionism remained in the West, notoriously in agriculture, which was seen as perhaps the principal sector for opening-up to the world economy in developing countries given the comparative advantage in this sector in the periphery.

Neoliberalism, through SAPs, had several key elements in terms of economic policy:

Deregulation: remove unnecessary controls on the ways markets operated.

Balanced budgets: in order not to distort money markets, states should not borrow and, thus, their expenditure should not exceed the revenue they could raise. However …

Reduced expenditure and taxation: governments should cut the size of their operations in nearly all areas and reduce direct income taxes substantially so that individuals had the incentive to work and save. On the other hand, new revenue might be raised by the imposition of indirect consumption (value added) taxes.

Privatisation: the state should no longer operate as a provider of economic goods and services. It certainly should not run nationalised industries in fields such as manufacturing. Its operations should be sold off (this would help reduce debt) and turned over to the private sector in sectors such as transport, telecommunications, energy supply and even health and education.

User-pays: rather than services being provided free through taxation revenue by the state, such as health and education, consumers of these services and the myriad of government functions, were asked to pay directly the true cost of providing them.

Trade and investment liberalisation: barriers to trade and investment must be lifted. These included removing tariffs, quota, and other restrictions on imports and investment. This would allow domestic industry and agriculture to compete at the global scale and reduce barriers to capital inflows.

Currency and money supply deregulation: governments should not manipulate the value of interest rates nor the national currency. These should be left to find their own value on international markets.

The SAPs were introduced as the immediate response to perceived economic crisis, typically these were instituted through the later 1980s and early 1990s. As a consequence, aid levels were cut (Figure 4.1). Overall, then, neoliberalism posited the view that a lack development was the result of poor governance – too much interference in the economy, corruption and inefficiency etc. – and a private sector that was too shackled by regulation. Recipient states were savaged by SAPs then blamed for their own inadequacies!

Modalities

We have already seen how this new neoliberal aid regime was put in place. Conditionalities were imposed through SAPs to force change on often reluctant and increasingly desperate recipient states. It was in essence a form of coercion. This was very much a top-down or outside-in imposed form of development and aid was a key vessel bringing the neoliberal changes. In referring to two prominent critics of these neoliberal approaches of aid – Joseph Stiglitz and Jeffrey Sachs, both of whom had worked for the World Bank – Gwynne et al. (2014: 5) echo how the IMF used a ‘cookie cutter’ approach to the reforms it insisted upon. Teams of economists often had little experience of the particular countries that they reported on and ‘advised’; rather they applied a simple set of ‘magic rules’ that were applied to a diverse range of recipient countries.

Although direct budget support had diminished during the modernisation era, this fell out of favour even more as a modality. Projects instead were favoured but these also underwent change. Rather than have large projects managed by government agencies and funded by donors, neoliberalism led to a shift whereby projects were more directly managed by donors themselves or their sub-contractors (often NGOs or private companies). This was the case for projects both managed within donor countries and in-country. Also, there was a tendency to downsize the scale of projects: the age of massive rural development schemes funded by the World Bank, for example, seemed to pass to a situation whereby smaller training schemes (to train civil servants in deregulation or to promote small business development, for example) and local projects (water supplies, sanitation, schools, etc.) were more common. Projects therefore tended to be shorter-term, smaller-scale and more localised. Furthermore, the projects came with new strict sets of conditions, in line with the SAPs so that recipients were tightly tied to donor requirements on how to manage economic activities and public services.

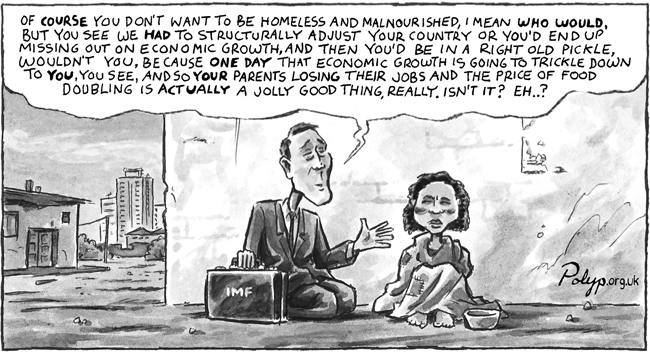

Source: Cartoon by Polyp reprinted by kind permission.

Effects

The effects of neoliberal reform were rapid and severe. The austerity packages with cuts in government services had an immediate impact creating rising unemployment and poverty (Figure 4.2). People had less money in their pockets (high inflation eroded the wages of those who still had jobs) but had to pay more for services. Privatised industries frequently shed staff and raised charges, and businesses which had enjoyed a degree of protection behind tariff walls now faced competition from cheap imports – many failed. These were often urban dwellers and urban poverty levels rose appreciably throughout the developing world. This trend was exacerbated by rising inequality in the countryside due to privatisation of landholding systems and the associated rise of export-oriented production. This perpetuated already burgeoning rural-to-urban migration. Furthermore, the poor and unemployed now found that their health centres and schools were charging fees or cutting services.

Alongside a rise in poverty and inequality, the attack on the state meant that some governments struggled to survive. Structural adjustment loans did not seem to succeed in promoting growth or even ‘widespread policy improvements’ (Easterly 2005: 20), but states had much fewer resources at hand. Pared back to the core, functions, such as law and order, also suffered and weakened states began to face internal threats, such as regional secessionist movements or organised crime. Weak states then faced cumulative effects as over-stretched revenue or customs departments were less able to raise the income streams needed by government. These problems began to mount to the point where even the private sector seemed to be concerned for the survival of the state – it was clearly time to re-assess whether neoliberalism had gone too far.

Despite all these problems, it is important to note that neoliberalism did have some winners and positive effects. Those who were able to pick up privatised industries or partner with new international investors (typically members of a small, local entrepreneurial class) found new opportunities for profit. Employers faced an abundance of labour, fewer restrictions and falling real wages. The end to price controls was good for food producers. Rural dwellers who produced small surpluses for sale saw rising food prices: the profitability of growing and selling staple foods such as maize, milk or rice improved, as did domestic production. Small businesses too could do well as local markets began to become established (though others struggled as unemployment led to a contraction of local demand). Export-oriented firms, often foreign owned, benefited in the newly deregulated economic context which led to lower wages and a more easily exploitable environment. The neoliberal revolution had been sudden and destructive and it also created a more vibrant market environment.

Neostructural aid regime (c.2000–c.2010)

Background

Criticism of neoliberalism and some of its harshest outcomes was strong among the left-wing from its first application. Not only was it damaging to the already marginalised in the societies where it was applied it also created and perpetuated a dangerous reliance on primary product exports, which did little to reverse to historic position of the economies of the Global South. However, when the criticism came from the cathedrals of neoliberalism themselves there began a turn against the Washington Consensus. Authors such as Joseph Stiglitz for example (see Box 4.2), who had himself served in the World Bank, were critical of the one-size-fits-all policies. They were also quick to point out that the hoped-for gains following the austerity periods of early applications, had not in fact arrived.

The rapid application of SAPs across the developing world had succeeded in ushering in an era with much less trade protectionism and much more foreign investment. The need for urgent reform was succeeded by a desire to consolidate the economic changes by instituting a more facilitative environment for the market to continue to grow. By the mid-1990s, there was a move away from blunt structural adjustment to more emphasis on constructing and strengthening institutions which could ensure political stability, protect property rights and widen citizen participation (Craig and Porter 2006). One of the upsides of this was that it removed tacit, and sometimes direct support, for a number of authoritarian governments across the world that had been protectors of the neoliberal models – ‘strong’ governments had been deemed necessary to introduce and protect the harsh measures required by SAPs. In the case of Latin America, once structural adjustment was superseded, the reasons for supporting such regimes disappeared. Thus, by the early 1990s all of the Latin American dictatorships had fallen. Eventually centre-left governments came to dominate that continent until approximately 2010 in the so-called Pink-tide. In the Global North too, the end of the Cold War ushered in – for a time at least – a shift to more centre-left governments including the administrations of Bill Clinton (USA 1994–2000) and Tony Blair (1997–2005).

The realisation of the failures of the Washington Consensus and the failings of SAPs, together with the geopolitical moment led to a more holistic approach to development in general. The tackling of poverty became central to developmental efforts and, as we discuss later, Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers replaced SAPs (Craig and Porter 2003). Rather than ‘rolling back’ the state, there was a clear expression of the need to ‘roll out’ the state, or at least a new version of the state. There was talk of intervention and ‘re-regulation’ that would help developing economies deal with the new challenges and opportunities of globalisation. Foreign investment and property rights (including ‘intellectual property’ in the form of copyrights over software, films and music) needed to be protected and the smooth operation of commerce needed effective state institutions in areas such as border control, law and order, and (light) regulation of banking and finance. Doing this with decimated government bureaucracies would be impossible and the follies of previous development policies were recognised. This latter point was not just due to a more positive opinion regarding the state vis-à-vis the pure free market, it was also a result of the New York terrorist attacks of 9/11 which led to the war on terror, involving efforts to prevent state collapse for fear that such places would become havens for extremism.

Combined with geopolitical factors was a more positive and informed public view in the West about the perils of underdevelopment: public campaigns such as Make Poverty History and Live 8 (20 years after Live Aid) suggested that there was a significant proportion of the electorate that wished to see aid improved (Action Aid 2008). The lack of development was seen as the result of inadequate support for education and health and the continued centrality of the debt burden (which new social movements such as Jubilee 2000 campaigned against). As a consequence, there was a shift from blaming the poor to blaming the lack of effective aid to support poverty alleviation. This came in part because of the development of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which galvanised and symbolised global development efforts during this period. The DAC began in the late 1990s, and concretised in the mid-2000s, a shift towards measuring aid progress through a broader range of development indicators and more inclusive measures.

Theoretical underpinnings

The neostructural period, as the name suggests, was underpinned by structuralism, as developed earlier by Raul Prebisch and others, but with significant differences (ECLAC 1990, Ocampo 1993). Towards the end of the neoliberal period in Latin America there was talk of ‘neoliberalism with a human face’ and a shift to market-based policies that took human welfare more seriously. Yet, in reality it could be suggested that the objective of governments was not so much to reduce poverty as an ideological goal in itself, but to win the compliance of the electorate for market reforms and lubricate the workings of the market. This eventually evolved into what has become known as neostructuralism. This approach makes a clear argument that the market alone will not solve economic distribution problems and will not lead to growth. A society that is more equal, better educated and healthier would help facilitate growth. Some referred to such ideas as ‘growth with equity’, but really it was more like ‘equity for growth’.

The ideas of this period were based on structuralist concepts in a number of ways. The original structuralists believed that the historic insertion of the marginalised economies of the world as primary product suppliers to the global economy largely determined their subsequent low dynamism. Neo-structuralists too were keen to increase the value-added component of exports and move away from reliance on primary products. There was a role for the state in subsidising the attainment of skills and innovation in order for this to happen, but never was there a suggestion of a return to ISI with a heavy-handed state regulation and subsidies. The free market was still at the centre of the policy. However, there was a more explicit recognition and analysis of the failures of the market – in terms of stimulating research and development, in terms of correcting damaging inequality and in terms of protecting the environment. Where such failures existed, intervention was considered justified and positive.

Another way of referring to this collection of ideas – or paradigm – is to think of it as Third Way politics, located somewhere in between capitalism and socialism – this is certainly how it was sold by UK Prime Minister Tony Blair and his academic advisors, such as the renowned sociologist Anthony Giddens. In reality it was more closely associated with neoliberalism, with some adjustment at the margins (Leiva 2008, Murray and Overton 2011a, 2011b). Mixed state-market models became in vogue, characterised by public-private partnerships and other centrist policy tools. There was also an explicit turn to the securitisation of aid allocation – the carving out of the state during the 1980s led governments in the West to view aid allocation with scepticism – stronger states would be required to ensure the objectives were met and funds were not siphoned off by corrupt officials and politicians.

Key agencies

If the key shift between modernisation and neoliberalism in terms of aid could be seen as a move away from New York to Washington – the neostructural period saw a return to New York and the United Nations, and to Paris with the DAC of the OECD. This was embodied in a number of initiatives which sought to codify and apply moves towards aid effectiveness. This signified a major return to internationalism perhaps best exemplified in the MDGs, launched by the UN, which placed poverty reduction, holistic development and the use of aid in order to achieve those things as central objectives.

At a more operational level, the DAC of the OECD took a lead role in the quest for improved aid effectiveness. Starting in Rome in 2003, it oversaw a string of large international ‘High Level Forums’ on aid effectiveness. These included Paris in 2005, Accra in 2008 and Busan in 2011. But it was the Paris meeting that was the most important (Box 4.2). That meeting, which included both donor and recipient government representatives, agreed to the adoption of five key principles – and associated targets and indicators – that were to guide aid delivery. In retrospect, these principles should be regarded as revolutionary, especially against the backdrop of previous neoliberal approaches. The first principle of the Paris Declaration – ownership – stated that recipient countries should own their own development. In practice this meant that governments should put in place clear strategies, institutions and funding to pursue development and poverty alleviation. The second principle – alignment – then committed donors to fall in behind these recipient strategies and institutions and augment the funding considerably. This aimed to end practices such as tied aid and allow recipients to manage the development process more directly. The other principles – harmonisation, managing for results and mutual accountability – then fleshed out the way aid should be delivered by calling for more efficient practices and transparent reporting. These principles became part of the mantra of development at the time. Aid agencies throughout the world embraced them and recipient agencies used them to develop their own localised versions and protocols for dealing with donors.

In these modes it is recipient states that are prominent – they must exhibit ownership, and the policies of donors should be aligned behind them in this regard. Therefore, recipient states are seen as crucial delivery agents for development policies established through aid relations. Given the emphasis once again accorded to effective aid, donor agencies were transformed and they were allocated larger budgets. The agencies responsible for overseas development and aid were also in many cases (in UK, Australia and New Zealand for example) removed from broader departments responsible for foreign relations (where many had been located hitherto) and given a clear mandate to focus on poverty alleviation. These shifts also had an impact on multilateral agencies as well as development banks in an expression of alignment with the MDG-inspired approach which saw wide co-operation between the UN and DAC motivated by the Paris Declaration.

During this period there were attempts to increase the size of the DAC donor ‘club’ and incorporate the voices of civil society and the private sector. The Busan summit of 2011 in particular sought to bring a number of non-traditional donors (especially China) into the aid effectiveness agenda (Glennie 2011) – although this was met with mixed success (laying the seeds for the emerging retroliberal regime at that time).

The shifts outlined above had an interesting and somewhat counterintuitive impact on NGOs. Recall that NGOs had been central in the neoliberal period often undertaking the tasks that were performed by the state previously. During the neostructural phase the kinds of change that NGOs had historically been championing were made more visible – health, education, and advocacy across a wide range of social and cultural issues. In this sense there was a donor NGO-consensus with regard to what was considered important during this period. However, given the increased centrality placed on nation states, the principal axis of interaction was indeed state-to-state. Therefore, despite the fact that NGOs had more funding during this period, their influence proportionally was lessened.

It is important to reiterate that whilst the state was to an extent ‘rolled-out’ during this period the market remained central. In particular, in the context of international relations, free trade deals, enforced through an increasingly powerful WTO, were considered crucial. There was no overt subsidy for private sector activity but the sector would reap the benefits of a general policy shift towards liberalising trade. It was often stated that development would come through embracing globalisation, not resisting it.

Policies and practices

The main policies and practices of this period have been noted above but it is worth re-capping here. SAPs were replaced by PRSPs – which placed poverty alleviation as the key strategic goal of development policy. National development plans, often as reworked Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs), also became a core part of policy sets. This saw a major investment in many departments across state sectors, which would help reconstruct the state following the neoliberal cuts of the 1990s. Unlike the modernisation period however, where the emphasis was very much on infrastructure, this period saw major investment in areas where societal benefits were considered highest over the long term – education and health. There was also more emphasis on cross-cutting issues such as gender and environment which accorded with MDG principles. In the search for globalisation with a human face, there was an associated emphasis on increased trade liberalisation embodied in discussion concerning the Trans-Pacific Partnership for example.

Despite the shift towards ownership of policies by recipients this period still involved extensive use of templates from donor countries – financial management, audits, state-owned enterprises, reporting/transparency, anti-corruption, and staff training. These amounted to new forms of conditionalities (Gould 2005, Eurodad 2008, Molenaers et al. 2015). They focused on political and bureaucratic systems – what we have termed ‘process’ and ‘political’ conditionalities (Overton et al. 2019) – rather economic reform through earlier SAP conditionalities. In this sense the effectiveness period brought a large compliance cost for recipient countries – which in the case of smaller ones could be overwhelming, leading, despite the rhetoric of ‘ownership’ and ‘alignment’, to what we have termed elsewhere an ‘inverse sovereignty effect’ (Murray and Overton 2011b, Overton et al 2012). Nonetheless, these practices had the objective of building the capacity of recipient institutions to manage development activities. Transparency and efficiency also involved donors who placed greater amounts of trust in recipient institutions and leadership. With trust in place, donors could step back, provide substantial funding, but not become involved in the everyday details of project aid programme management.

Modalities

This period saw a large shift away from projects to programmes, and in general to ‘higher-order modalities’. In particular, the use of sector wide approaches (SWAps) and GBS became more important (see Chapter 5). This led to the increased importance of robust and transparent financial management systems that could track and analyse the impacts and risk of the higher-level modalities and ensure that increased aid funding went through smoothly, without leakages or inefficiencies, through government channels to reach desired targets. Overall, this led a move to longer-term funding programmes that were multi-year commitments reflecting the ascendency given to the long-term implications of aid donation and the centrality of consistency and reliability.

The centrality of recipient government agencies in the neostructural approach put the dispersion and management of aid funding firmly within the bureaucratic structures of government departments. Long- and medium-term term strategic planning, in the form of national plans or reworked PRSPs, provided the direction for line ministries to develop firm plans and commitments to deliver key services, particularly in the health and education sectors (Wohlgemuth 2006). SWAps were particularly important for facilitating programmes of multi-year expenditure that could co-ordinate different activities focused on achieving MDG-inspired targets. Sound financial management was particularly important for aid donors, for it could re-assure them that their funds, matched by significant local government budget commitments, would reach where they were needed and make a sustained and significant contribution to meeting poverty alleviation-related goals. The move away from discrete projects, however, meant that the visibility of aid funding was greatly lessened. Instead of having concrete projects with demonstrable physical outputs, aid donors had to rely on aggregate data and often less explicit indicators. The display of donor logos and publicised ceremonies to open a health clinic or water scheme were replaced by government-generated data on enrolment rates of girls in primary education, or the number of visits to a trained midwife, or the proportion of people with access to potable water. On one hand the temporal and spatial scale of the potential impact of donor aid was greatly increased – change could be affected over a wide area over a sustained period of time – and the role of local government agencies was expanded (with hopefully an accompanying increase in their public credibility). Yet, on the other, higher donor expenditure was accompanied by a lower profile for, and a diminished ability to control aid dispersal by, donor agencies.

This shift to higher-order modalities meant that projects became relatively less important as a means of aid management. Only where there was lack of trust between the recipient state and the donor would lower-order project modalities be used. Here, local NGOs continued to play important roles, as they had under the earlier neoliberal approaches. Again, they were seen as contractors for aid-funded service delivery, with accompanying contractual obligations to comply with donor financial management and reporting systems. Unlike the higher-order modalities, in these situations, donors could maintain their close association with change on the ground – public signage could continue to publicise their ‘brand’ alongside local civil society. Yet the efficiency of this approach, in terms of scale of impact, remained limited, and, in terms of relative overhead costs, remained high.

Effects

In some ways the neostructural regime can be considered the golden period of aid. The focus on poverty reduction and other targets embodied in the MDGs created a galvanised global project. The Paris Declaration of 2005 defined specific targets and pathways with respect to the pursuit of effectiveness. And the scaling-up of aid activity created larger budgets to be dispersed and managed. There seemed to be a consensus at all political levels with respect to the usefulness and potential effectiveness of aid, and the public imagination in this regard was positive. The example of growth in China during this period was also instructive – the state-led capitalism that had dominated there since reform in the 1980s, had clearly led to historic reductions in poverty. Although this had nothing to with ODA, it did illustrate the potential of the role of state management in poverty reduction. This led to a large growth in the levels of aid given in both absolute and relative terms and it also led to the growth in institutions that administered them. In terms of achieving the MDGs, there were some significant achievements, especially with regard to poverty reduction in East Asia (though, again, this had little to do with aid) and in funding for education and health programmes throughout the developing world. How much this has to do with the new neostructural consensus is debatable. What is certain is that aid regained some of the respect had lost in the neoliberal 1980s: it was seen as a legitimate foreign policy tool as well as a moral obligation of donors.

Retroliberal aid regime (c.2008–)

Background

The promise of the neostructural period was soon interrupted by events in the global economy and their geopolitical ramifications. The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007–2008 represented the largest disruption to international capitalism since the Great Depression of the early 1930s (van Apeldoorn et al. 2012). At the time it was considered feasible that the entire international economy might collapse and globalisation was under threat (Wade 2010). Thinkers on the left see the roots of this catastrophe as the over-extension of free market principles during the neoliberal period, particularly in the financial sector, which had become so reckless in its lending and obsession with financial instruments that the whole economy had become dislocated from ‘production’ (Peck et al. 2010; Peck 2010). This manifested in terms of property price bubbles across the world. The networked nature of the global economy meant that the negative consequences of this were soon transmitted in a contagion-like effect. Furthermore, the crisis in capitalism forced a rethinking of ‘development’ (Hart 2010).

The solution to this problem was not, as some may have hoped for, a better regulatory system of the financial sector and a closer alignment with the ‘real economy’. Nor did it lead to punishment for those who had created the problem – the financial institutions. Rather, the opposite occurred – large companies were bailed out and considered too large to fail. The impacts of the crisis had a real implication for economic dynamism in the Global North, where recession took hold in the majority of economies – particularly those that were more integrated into the global financial system.

This had a knock-on effect in the Global South as exports to European and North American economies were reduced. Economies which relied on trade with these regions suffered markedly, yet others were relatively unscathed. The demand for natural resources continued unabated in China and economies, such as Chile, that specialised in production of primary products actually saw a rise in the relative price of such products, leading to gains in the terms of trade, export earnings, and ultimately protection from recession.