2What is aid?

Learning objectives

This chapter will help readers to:

Understand that the concept of aid is broad and contested. It is more complex than definitions utilised by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)

Appreciate that aid worldviews have shifted over time, although all to an extent continue to exist and overlap in different places at different points in history

Assess how views concerning aid have shifted from simplistic notions of altruism and giving to complex multi-faceted, strategic and sometimes mutual interest-based sets of policies

Understand that official definitions of aid have changed over time to include a wider range of forms and yet still does not include everything that might be reasonably considered ‘aid’

Assess how the geography of aid donors and recipients has shifted markedly over time as the line between ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ shifts and the line between donor and recipient becomes blurred

Understand that there are many forms of aid beyond traditional Official Development Assistance (ODA) as measured by the OECD

Evaluate the rise of new aid powers, such as China, and understand the diverse strategies and forms their assistance is taking

Discuss the concept of ‘South–South’ co-operation and the notion of a post-aid world

Aid is one of the most prominent features of debates concerning both development and international relations. Flows of aid account for many billions of dollars across the globe each year, they tie countries together in webs of negotiations and agreements, and they contribute to the improvement in the welfare of many millions of people. There seems to be a strong moral justification for giving aid (Culp 2016). Yet despite the significant size of aid flows and continuing efforts to promote development worldwide, we are still rather in the dark regarding what is meant by ‘aid’, how we might define and measure it, let alone understanding whether or not it meets its objectives.

The word ‘aid’ implies a number of things. As we saw in Chapter 1, it invokes notions of ‘help’ and ‘assistance’. In doing so, it suggests that aid relationships involve a net flow of resources from one party (a donor) to another (a recipient). It also implies a sense of altruism: that assistance is given for the sake of ‘doing good’, of helping those in need, and for donating resources without the need for an equivalent return. ‘Aid’ is thus a powerful discursive tool for it suggests to us that the world is structured in particular ways with certain inequalities in power and resources, and flows which aim to meet some of the most pressing of humanity’s needs. As discussed in Chapter 1, in this book we will explore the complexities of international aid and see how it is linked to different ideas of ‘development’. In this chapter, we examine the way the term aid is defined and measured. Here we steer the discussion towards what has been the dominant architecture of aid, that centred on the OECD/DAC definition of ODA and constructed by a dualistic definition of donors and recipient countries. We deconstruct this mainstream view of aid by firstly describing forms of assistance that have not been included in ODA (such as migration or trade preferences) and then identifying new players and evolving ‘South–South’ ways of operating that are beginning to challenge and disrupt the OECD-centred aid hegemony.

Changing aid worldviews: motivations through history

Aid has changed over time to become a very diverse and complex set of activities and resource flows. In what follows we consider four ‘aid worldviews’ in the evolving rationale and nature of aid: 1) helping those in immediate need; 2) long-term modernisation and welfare improvement; 3) advocacy and emancipation through education; and 4) shared prosperity and explicit mutual benefits. Although elements of all of these sets of motivations persist and overlap, they have, in rough terms, superseded one another chronologically.

(i) Aid as relief

Firstly, at its most basic, aid has involved the provision of financial and material resources to those ‘in need’. If we look at the origins of many development agencies, be it the World Bank or Oxfam, we see this most basic function as a key starting point. The World Bank, for example, had an initial mission to focus on reconstruction from the chaos in Europe following the Second World War. Oxfam started as a famine relief organisation focused on Greece in 1942. Disasters and humanitarian relief provide the most obvious raison d’être for assistance: people suffer because they lack food, shelter, clothing, potable water and the like and their survival is threatened unless external resources can be provided. This justification for aid continues very much through to the present, particularly in the public imagination of aid. Natural disasters – droughts, tsunamis, floods, earthquakes etc. – are followed by calls for donations and the sending of materials to affected areas. Disasters can also be human-induced – people are displaced by war and conflict, insecurity, forced resettlement, economic collapse – and similar responses may be forthcoming.

The concept of aid in this sense appears to be simple. People are in dire need with their welfare and very survival threatened and other communities have surplus resources which they can donate to alleviate human suffering. People in relatively well-off countries and communities often respond readily to images of starving children or destitute mothers or devastated homes. The assembling and dissemination of these images accompanied with appeals to give has constructed a particular public imaging of aid: it is one-way, it is based on pressing need, and it is effective in relieving suffering.

(ii) Aid as development

Yet whilst this basic view of aid discussed above persists, it has been joined – and superseded in influence – by a second set of motivations, which sees aid as a way of underwriting forms of development that pre-empt suffering and enhance human welfare. The development rationale for aid is long-standing and can be traced most explicitly back to the 1940s and 1950s and ideas of modernisation. Some (e.g. Rist 1997; Escobar 1995) trace it directly to President Truman’s inaugural address in 1949 (Box 2.1).

We can see clear parallels here with the thinking behind the Marshall Plan (Box 1.2) that was operating at the time and had a similar view of the USA’s superior technology and economic performance and a similar goal to reconstruct a new post-war global political and economic system centred on, and dominated by that country. Truman laid this foundation for the grand post-war ‘development project’ (McMichael 2017), which had aid at its centre: aid that would provide not just material resources but perhaps more importantly the ‘technical knowledge’ to align their development aspirations and trajectories with those of the West. This development rationale for aid was adopted through the 1950s and 1960s by major aid donors (USA, UK, France, Japan etc.), by the large multilateral agencies (the World Bank, the United Nations) and later by NGOs who shifted from humanitarian relief to development activities to improve long-term human welfare.

Aid for development involved the full gamut of what we consider development assistance: loans for hydroelectric dams or roads; the building of schools and hospitals; improving rural water supplies and irrigation; technical assistance with better crops; building the capacity of local officials to carry out the modern functions of a state; scholarships to study abroad; better urban sanitation; provision of medicines; public health and family planning campaigns; and a plethora of other projects and programmes. In terms of public support, this system of aid was not as simple to justify as it meant long-term commitments to needs that were not quite so obvious or pressing as a famine or an earthquake, for example. Simple and facile arguments such as ‘give a poor man [sic] a fish and you feed him for a day; you teach him to fish and you give him an occupation that will feed him for a lifetime’ could be used to justify such spending. Yet the approach took donations less directly out of the pockets of members of the public and more from the public accounts of new government aid agencies: aid became a function of the state rather than being left to the vagaries of public choice. This move linked aid to the wider strategic and diplomatic considerations of donor states and there, to a large extent, ODA has resided ever since.

(iii) Aid as advocacy

A third less-direct, non-material rationale for aid has evolved over time but its origins and impacts are less obvious. Advocacy is a much less tangible form of assistance, yet its proponents would argue that it is just as important, if not more so, than providing material resources. Advocacy stems from the ideas of Paulo Freire (1970) and others who saw that poverty was linked to forms of oppression and this was best tackled through people becoming aware of the systems which impoverished them so they would be empowered to take action themselves. Aid in this emancipatory sense becomes a means to support education and public awareness and it can have a quite radical and destabilising effect as it attempts upset the status quo of power imbalances, subjugation and impoverishment. We have seen this advocacy approach used in relation to gender-based aid and development interventions. Here aid is used to support both public awareness programmes (for example, against gender-based violence) and particular programmes that offer training and support and engage in political lobbying on women’s issues.

Awareness raising and advocacy for the rights and actions of the poor also involves working with people in donor as well as recipient countries and, often, promoting ways of linking them together. This can have a political dimension, encouraging donor governments to recognise and support the efforts of, say, a particular minority group in a partner recipient country. Or it can be economic, using fair trade networks to link producers and consumers. Because of its political and transformative agendas, aid for advocacy often faces suspicion on the part of donor agencies (though historically some European donors have been active in this manner) and sometimes active resistance on the part of recipient states. Advocacy, though, does require aid activities to consider the underlying causes of poverty and support action to tackle those causes, rather than accept that poverty alleviation can be addressed simply by giving more resources or setting countries on a particular path of trade, economic growth and modernisation.

(iv) Aid as donor self-interest

We might add another set of motivations and resultant view of aid that has evolved in recent years, that which seeks to use aid explicitly as a way to promote the interests of donor economies (alongside those of recipients). It is important to note that aid donors perhaps have always sought some form of return, economically, diplomatically or in terms of their international reputation. Yet in the past decade especially, we have seen donors become a lot more open about what economic benefits they expect from an aid programme. This has been encapsulated in the ‘shared prosperity’ mantra (more on that in Chapter 3) and seen in the way the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has preferred to talk about South–South co-operation rather than ‘aid’. There are now more overt efforts to use ‘tied’ aid to link the business operations of donor companies with development activities offshore. This also aligns with efforts to broaden the government base of aid delivery and calls for a ‘whole-of-government’ approach to ODA, counting the offshore operations of different line ministries (police, defence, customs etc.) within aid budgets.

(v) Aid as private sector development

As part of this recent re-conceptualising of aid, we have seen an explicit effort to widen the arena of aid to see not just government agencies or NGOs as the key players and improved welfare as the key objective, but also to include the private sector as a crucial driver of development and economic growth, investment and employment creation as aspects which can be supported by aid. The Busan High Level Forum on aid effectiveness in 2011 was a notable event where these ideas were expressed and this was backed-up by the Addis Ababa meeting on financing for development in 2015, which argued that private sources of capital should be included in the way development and aid are conceived and practiced (United Nations 2015a).

This shift to include the private sector has a number of important implications for aid. Firstly, we can see how new terminology and activities have entered the realm of aid. Thus, we have seen how private philanthropists (such as the Gates, Bloomberg, Zuckerberg, Bezos and Buffet family names) have become much more part of the public consciousness of aid, largely because the sheer volume of their philanthropy (Bill and Melinda Gates are reported have donated over $US35 billion – Kumar 2019: 21) now ranks them ahead of many donor countries in the ODA rankings. We also see talk of ‘social enterprises’, ‘corporate social responsibility’, crowdfunding’ and ‘brand aid’ as ways whereby new sources of finance are tapped through market enterprises to be made available for development and welfare projects (Kumar 2019; Richey and Ponte 2011). More fundamentally, we are seeing changes in the way we conceive forms of development. As we will see in Chapter 4 and the discussion of ‘retroliberalism’, there has been a marked discursive shift in the past decade in the way development is conceived at the policy level. Economic growth – rather than the prior Millennium Development Goal (MDG)-inspired focus on welfare (poverty alleviation, education, health, gender equity, etc.) – is seen as the most effective way to achieve development and it is assumed that if there is growth and the creation of new enterprises and jobs, then development has been achieved. This then has reconstructed the view of aid. Aid, it is believed, can promote economic growth by supporting the private sector to invest and the market, assisted by donor aid strategies, will ensure that increasing employment and incomes will alleviate poverty and ensure improved well-being for all. Unlike the neoliberalism of the 1980s and 1990s, when the market was left alone to operate and aid was reduced, this new aid environment openly lobbies for aid to be increasingly channelled to support and promote private sector development.

Aid motivations: summary

So, we have seen that aid has progressed from a simple notion of giving to those in dire need to incorporate strategies for long-term development, support for self-determination and recently for a sort of shared programme that facilitates economic growth on both sides of the aid relationship. These ‘aid worldviews’ as we term them have then become formalised and evolved sets of guiding principles and methods of delivery that can be termed ‘regimes’, as we later discuss in more detail in Chapter 4. We can question whether the general change we have witnessed can be considered ‘progress’ in aid at all. Given the most recent worldview that has turned to concepts of shared prosperity some have suggested the concept of aid is no longer relevant, we have moved so far from the simple notion of ‘aid’ to a point where perhaps the term has lost its utility. It is now so muddled with competing motivations and strategies and so diluted that perhaps we are approaching what Mawdsley et al. (2014) have termed a ‘post-aid world’.

Defining aid: Official Development Assistance (ODA)

Given these contested and dynamic conceptualisations of aid, we can now turn to the way ‘aid’ is defined. The issue of defining aid has attracted the attention of donors in particular. Donor countries, particularly through the agency of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the OECD have attempted to standardise the way aid is defined and how it can be measured (Box 2.2). The DAC has acted as the main institution collecting data on aid flows and share common practices. The DAC approach to defining aid has been to employ the term Official Development Assistance (ODA) in order to more precisely frame what aid is or should be. ODA is an important term as its three components mark significant aspects of aid: ‘official’ means that ODA only flows through recognised (usually state or large multilateral) agencies; ‘development’ means that it must be used for funding activities that promote forms of development-related activity (rather than, say, military expenditure); and ‘assistance’ implies that there should be a net flow of benefits from donor to recipient.

The DAC definition of ODA therefore is:

‘those flows to countries and territories on the DAC List of ODA Recipients and to multilateral development institutions that are:

provided by official agencies, including state and local governments, or by their executive agencies; and

each transaction of which:

is administered with the promotion of the economic development and welfare of developing countries as its main objective; and

is concessional in character’.1

Although this seems a precise definition, in practice, DAC has modified what can be counted or not over time and there are contentious areas on the margins of this definition. For example, although there is a strong statement that military expenditure is excluded from ODA, the costs incurred by the armed forces of donors to deliver humanitarian assistance may be counted as can some ‘developmentally relevant’ peacekeeping activities by armed forces. Nuclear energy for civilian uses can be counted also (OECD n.d.). In one of the most bizarre episodes in the changing definition of ODA, there has been debate concerning what forms of military expenditure might be included with regarding to peacekeeping (DAC Secretariat 2016a). Donors such as the United Kingdom have preferred a wider definition of ODA to include ‘peace and security costs and well as the costs of countering violent extremism’ (Devex 2016) whilst others, such as Sweden have resisted this potential militarisation of aid. What has happened is that DAC has resisted some forms of military aid accounting such as military equipment or salaries but some forms, such as ‘expendables’ (perhaps even ammunition!) and training, may be allowed (Heinrich et al. 2017; Christie 2012).

Recently, new elements have been added to the list of what counts as ODA. For example, the costs of refugee resettlement within a donor country in the first year are now included and this has led to a significant widening of the scope of ODA accounting (and subsequent favourable impression) for those countries receiving and supporting large numbers of refugees. These costs have become a substantial element of ODA reporting: ‘In 2015 there were 10 members [of OECD-DAC] for whom in-donor refugee costs were between 10% and 34% of total ODA’ (OECD 2016) and this was particularly the case for European donors. There are pressures to widen even further the ODA definition, to include, for example, donor government support for donor country companies to do business in developing countries. There are complex issues regarding more diverse financial instruments and the degree these are concessionary or not, and there is a thorny question of ‘additionality’ (‘additional’ funds spent by the private sector in the course of normal business, but which address the development and welfare of a country). To a large extent, these changes have not only made aid accounting much more complex, but also taken the realm of ODA away from dedicated aid agencies within donor governments. Rather, a wide range of activities is now accounted for involving activity at ‘home’ and abroad by many donor state agencies including the military, police, many government departments, and private sector.

ODA, then, is a useful measure for us in order to glean an idea of what forms of assistance flow from some countries to others. Furthermore, the DAC framework gives us a standardised, if imperfect, approach to defining and measuring aid. It is far from ideal as its criteria have changed over time and it does not include a number of significant forms of assistance (see later in this chapter) and some significant donors (such as the PRC). Also, it blinds us to significant reverse flows from ‘recipients’ to ‘donors’ (such as political favours, economic concessions, loan repayments, profits and investment dividends etc.) and the way these may be linked to aid receipts. However, its core elements (official, development and assistance) specify important principles and its approach to data collection gives us a reasonably consistent, if constrained, set of data to track and analyse aid flows.

Defining aid: recipients and donors

Defining and tracking ODA over time is also complicated by changes in counting what might be considered a ‘developing’ country (and be regarded as a recipient) and who is seen as a donor. The DAC largely draws on the World Bank’s classification of low-, middle- and high-income countries. The list of recipients includes all those classified as least-developed countries and all low- and middle-income countries (except any who are members of the G8 or European Union). Those that exceed the high-income level for three years in a row are removed. Looking at changes in countries classified as recipients since 1989 (Table 2.1) we can see some major shifts. Of the 24 countries added to the list, most are the result of the dissolution of the former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia into new states (as well as the splitting of the former US Trust Territories of the Pacific Islands into four Micronesian states). However, those 42 countries that have fallen off the list represent some examples of apparently successful economic growth: the oil-rich states of Brunei, Bahrain, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, UAE and Qatar; the Asian ‘tiger’ economies of Singapore, Korea, the Republic of China (Chinese Taipei) and Hong Kong; a multitude of small island states in the Pacific and Caribbean that have benefited from tourism, remittances and the like; and several European countries that have joined the European Union, such as Portugal and Greece.

Countries added: |

Countries removed: |

Albania (1989) |

Portugal (1991) |

South Africa (1991) |

French Guyana (1992) |

Kazakhstan (1992) |

Guadeloupe (1992) |

Kyrgyzstan (1992) |

Martinique (1992) |

Tajikistan (1992) |

Réunion (1992) |

Turkmenistan (1992) |

Saint Pierre and Miquelon (1992) |

Uzbekistan (1992) |

Greece (1995) |

Marshall Islands (1992) |

Bahamas (1996) |

Federated States of Micronesia (1992) |

Brunei (1996) |

Armenia (1993) |

Kuwait (1996) |

Georgia (1993) |

Qatar (1996) |

Azerbaijan (1993) |

Singapore (1996) |

Eritrea (1993) |

United Arab Emirates (1996) |

Bosnia and Herzegovina (1993) |

Bermuda (1997) |

Croatia (1993) |

Cayman Islands (1997) |

Macedonia (1993) |

Chinese Taipei (1997) |

Yugoslavia – Serbia and Montenegro (1993)* |

Cyprus (1997) |

Slovenia (1993) |

Falkland Islands (Malvinas) (1997) |

Palau (1994) |

Hong Kong (China) (1997) |

Northern Marianas Islands (1994) |

Israel (1997) |

West Bank and Gaza Strip (1994) |

Aruba (2000) |

Moldova (1997) |

British Virgin Islands (2000) |

Kosovo (2009) |

French Polynesia (2000) |

South Sudan (2011) |

Gibraltar (2000) |

|

Korea (2000) |

|

Libya (2000) |

|

Macau (China) (2000) |

|

Netherlands Antilles (2000) |

|

New Caledonia (2000) |

|

Northern Marianas Islands (2000) |

|

Malta (2003) |

|

Slovenia (2003) |

|

Bahrain (2005) |

|

Saudi Arabia (2008) |

|

Turks and Caicos Islands (2008) |

|

Barbados (2011) |

|

Croatia (2011) |

|

Mayotte (2011) |

|

Oman (2011) |

|

Trinidad and Tobago (2011) |

|

Anguilla (2014) |

|

Saint Kitts and Nevis (2014) |

Note: * Serbia and Montenegro were listed separately in 2006.

However, the DAC recipient list does not give a fully accurate picture of who receives aid. Leaving aside the question of internal forms of assistance (spending by governments on poorer regions or groups within their own countries), we know that some donor governments continue to provide support for other countries even after they graduate from middle-income or recipient status. In the South Pacific, for example, French ODA to French Polynesia and New Caledonia amounted to two of the three largest flows of aid to the region prior to 2000 (alongside Australian aid to Papua New Guinea). Yet in that year, the two French territories were removed from the list of recipients mostly because estimates of their income put them in the high-income category, but perhaps also because there was a political statement to be made that they were the responsibility of metropolitan France and an ‘internal’ matter for funding, rather than fully independent states receiving international development assistance. We know that aid did not stop to these territories after 2000 and very large flows continue in the form of budget support and development projects (Prinsen et al. 2017; Overton et al. 2019). However, these are not recorded as ODA by DAC.

On the donor side, there have also been significant shifts. Membership of the OECD and the DAC (not all members of the OECD join the DAC) has expanded. Table 2.2 shows that the 11 original members of the DAC in 1961 were joined by another 10 by 2000 and 8 since (the latter reflecting changes in the political geography of Europe). Some countries that had originally been classified as recipients (Portugal, Greece, Korea) have gone on to join the DAC and become donors themselves and, as we shall see, there are other countries that remain on the list of recipients and continue to receive ODA (for example, India and Indonesia), but who have become donors themselves.

Original Members (1961) |

Later Members (year joined) |

Australia |

Norway (1962) |

Belgium |

Denmark (1963) |

Canada |

Sweden (1965) |

European Union (& predecessors) |

Austria (1966) |

France |

Switzerland (1968) |

Germany |

New Zealand (1973) |

Italy |

Finland (1975) |

Japan |

Ireland (1985) |

Netherlands |

Spain (1991) |

UK |

Greece (1999) |

USA |

Hungary (2004) |

|

Korea (2010) |

|

Czech Republic (2013) |

|

Iceland (2013) |

|

Poland (2013) |

|

Portugal (2013) |

|

Slovak Republic (2013) |

|

Slovenia (2013) |

As the global economy has changed, its old North–South dual structure has weakened considerably and, with that, we have seen a blurring of the aid donor-recipient distinction. Not only are countries graduating from ‘developing’ to ‘developed’ status, they are also shifting from being recipients to being donors. However, in the process of transition from one to the other, we are seeing interesting new aid relationships and practices evolving. In the case of Latin America, for example, it is evident that some countries, such as Brazil and Chile (Box 2.3), are developing their own aid strategies, even whilst they may still be receiving some forms of ODA. Other countries in this category who have sought membership of the OECD, but who are not yet members of the DAC include Estonia, Israel and Slovenia (newer members of the OECD) and Russia, Lithuania, Colombia and Costa Rica (seeking accession to the OECD).

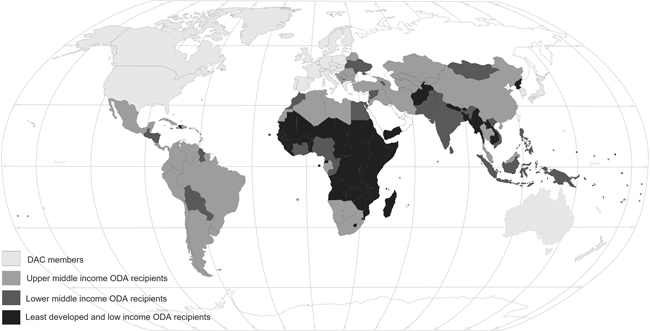

All in all, we can see a constantly changing geography of ODA. Looking at the situation in 2019 (Figure 2.2) there is an overall picture of division between the donor world (largely Europe, North America and parts of Oceania and East Asia) and recipients (overwhelmingly still in Africa, South and central Asia, the Pacific Islands, and Latin America). This a conventional North–South model of the aid world. Donors are mostly countries of the ‘Global North’ and recipients constitute the ‘Global South’ and this model is embedded in the DAC/OECD system of donors and recipients outlined above. However, changes are occurring with more countries undergoing transition out of recipient status and others straddling both groups.

Source: www.stats.oecd.org

Types of aid: tied and untied

One feature of aid and ODA is that many of the resources that are provided by donors flow back in some way to them. ODA almost always involve some form of two-way flow and/or elements of reciprocity. These can be quite explicit. ‘Tied aid’ is that which requires recipients to receive resources that are derived from the donor. These might be, for example, funding for a large rural development project that stipulates that the machinery involved must be purchased from a donor country-based company. Or it might involve technical assistance where the consultants or trainers must come from the donor country. These are ways in which some donors ensure that they get some explicit return to their own economies through the aid they give. Tied aid is a form of subsidy for the domestic economy in the name of foreign assistance. Tied aid also may be less explicit but involve similar two-way flows. The use of aid to support scholarships for students to study overseas in donor schools, technical institutes and universities does train recipient students with important skills (and they are often required to return home immediately after their studies finish) but the money spent to train them (tuition fees, accommodation, living expenses) are spent in the donor economy. Also, in the longer term, graduates return home with personal and professional networks linking them to donors and with skills that may align more with donor systems and ways of working than those at home. Such returns to the donor economy both short- and long-term were once described by a politician in charge of an aid budget as ‘doing well from our doing good’ (Scheyvens and Overton 1995).

Another growing form of ‘aid’ – and one that is inextricably tied to the donor country – is the recognition now of costs used to support refugees within donor countries as ODA. Very little of this expenditure is disbursed outside the donor country and although it would seem to meet the welfare needs of a particularly vulnerable segment of the population, it rather stretches the credibility of the way aid and ODA are defined and measured, when virtually all of the expenditure returns to the donor economy. Box 2.4 examines the growth of these costs in ODA accounting in recent years. It has become a significant component of ODA for some countries and, to a large extent, accounts for the growth in ODA in recent years in countries such as Germany. As we will see in Chapter 4, it is also very much in line with a new ‘retroliberal’ approach to aid, which seeks openly to use aid budgets to benefit donor economies.

‘Untied’ aid is often regarded as better for the recipients – they can acquire the best and cheapest equipment and advice from the open market and are not forced to spend their aid receipts on what they might consider expensive or unsuitable inputs from the donor. However, even when aid is untied, there are often explicit expectations and/or implicit understandings that recipients will ‘return the favour’ in some way, be it in terms of diplomatic alignment, political support in international meetings or favourable trade concessions. We will explore these motivations and the way they affect changing approaches to aid in Chapters 3 and 4.

Shifting aidscapes: diverse geographies and types of aid

Yet before we dispense with the concept of aid and ODA, we should recap on what the DAC-centred view of aid has given us. Despite the recent widening of aid definitions and practices and more explicit donor self-interest, we still face an aid world which has been constructed in particular ways. There is still a dualistic aid architecture marked by a sharp division between supposedly wealthy donors (OECD members) and supposedly needy recipients (on the OECD ODA recipient list). And we see and study ‘aid’ in terms of the largely state-to-state financial flows that ODA defines and measures.

The increased diversity in approaches does not necessarily spell the end of aid as a unifying concept. Institutionally, and through DAC membership and categorisation, there is a divide between ‘donors’ and ‘recipients’. Some may have a foot in both camps and membership of the categories is continually changing but generally the divide is marked. And geographically, this divide can be depicted starkly. It may not be a simple North–South map (donors in Oceania and East Asia and recipients in the northern hemisphere disrupt that depiction), but it possesses some notable features. There are core donor regions – West and Northern Europe and North America – and there are continuing recipient region concentrations (sub-Saharan Africa, South and Central Asia). However there are now distinct geographies of change: many former members of the Eastern European bloc have transitioned to become donors (Slovenia, Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic); the small island states of the Pacific and Caribbean are still aid recipients (and remain some of the largest per capita aid recipients), but many are progressing to middle- and high-income status; parts of South America (Chile, Uruguay and Brazil in particular) – and perhaps India – are straddling the donor-recipient line; and the rapid economic growth of several Asian states (Singapore, Malaysia, Taiwan, Thailand, China) and several oil-rich states have seen countries become donors, often using their own measures of, and approaches to, development assistance and co-operation.

We are at an interesting historical moment as these trends continue to evolve. The DAC system is still a dominant element of the aid world but it no longer represents an exclusive club of rich donors united by a particular worldview, set of motivations or even geopolitical structure. In this sense we should perhaps talk of different aid worlds – or diverse ‘aidscapes’. We still focus on official flows of ODA that we can define and measure and map but increasingly we see other forms of development interaction that are more reciprocal and complex. In order to understand where the aid world might be heading, we now turn to examine forms of ‘aid’ that have not been captured by DAC definitions and measurements but which have operated significantly in the past and may emerge again in some form in the future. Then we begin to construct an emerging different, and much less dualistic geography of aid.

Re-defining aid: non-ODA forms of assistance

As we have seen, ODA is but one way of defining and measuring the development assistance some countries give to others, though it is undoubtedly the most prominent and widely used approach to analysing aid. Other forms of assistance have been prominent in the past and some persist today. These have been very important forms of ‘aid’ even if they have not been officially recognised as such and have often defied measurement. Whereas ODA puts stress on financial flows and a stark donor-recipient model of aid, these alternative forms of aid are often more to do with political concessions and legislative changes which do not involve immediate and direct flows of state-to-state resources. Rather they help provide environments which facilitate the ability of individuals and enterprises to operate more freely and globally. They usually lack the strategic and targeted approach of much ODA (to particular projects, sectors and groups) but they nonetheless have been constructed explicitly to provide development benefits. We now turn to examine some of these alternative forms of aid; forms which are more difficult to define and quantify but which may have significant development impacts. Some have been favoured by the major Western donors; others have been pioneered by more non-traditional donors.

Migration

Migration is closely linked to development in a number of ways, yet it is not often regarded as a form of aid. The ability of people in some countries with more restricted economic opportunities and welfare provision to move freely to countries where these prospects are perceived to be better is a major driver not only of human movement but also of a number of development processes.

Firstly, migration can be a way for people to gain access to new labour markets. Relatively better paying jobs overseas, even if accompanied by often very poor working conditions and low wages, are a way for individuals to seek personal gains in wealth and welfare. They may decide to move permanently and gradually sever ties with their country of destination. We can see this as an individual- or family-based development strategy. It is also partly a driver for many thousands of refugees who seek to leave their often conflict-ridden or poverty-affected homes in search of a better life. However, many who move to find jobs in other countries do so in ways which may not be permanent and/or which maintain ties with families at home. In these cases, many of the earnings gained from overseas work are saved and remitted home to relatives. These remittances are very substantial on a global scale and, for some countries, constitute one of the largest segments of national income (Table 2.3). These flows of workers and remittances are hugely diverse. There are domestic workers from the Philippines to be found in Hong Kong, construction workers from Bangladesh and Pakistan in the United Arab Emirates, soldiers from Nepal serving in the British military forces, Mexican agricultural labourers in USA, and nurses from Fiji working in the aged care sector in Australia. Some are able to save and send substantial sums; others may be trapped in work contracts that severely limit their freedom of movement and ability to earn and save above a bare level of subsistence.

Country |

Remittance inflow($US mill) |

Remittances as Share of GDP (%) |

Tonga |

165 |

35.2 |

Kyrgyz Republic |

2960 |

33.6 |

Tajikistan |

2275 |

31.0 |

Haiti |

2986 |

30.7 |

Nepal |

8064 |

28.0 |

El Salvador |

5458 |

21.1 |

Honduras |

4746 |

19.9 |

Comoros |

143 |

19.1 |

West Bank and Gaza |

2561 |

17.7 |

Samoa |

142 |

16.1 |

Source: World Bank https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/migrationremittancesdiasporaissues/brief/migration-remittances-data

The issue of remittances has been the subject of debate. Critics (see Gamlen 2014) argue that remittances tend to decline over time as migrants decide to settle overseas and cut their ties; money sent home is often spent on consumables (often imported luxuries) rather than invested in productive enterprises; and labour migration may rob source countries of the young and most able workers, leaving only the old, young or inform as dependents. The latter point is often tied to notions of a ‘brain-drain’ whereby migration leads to a loss of essential skilled and educated workers (Gibson and Mckenzie 2012). On the other hand, other commentators take a more positive view of migration and remittances, seeing such flows being sustained over time – even if workers do stay overseas they are joined by others and money is still sent home. They also see instances where workers overseas do return home, not only with savings but also new skills (a sort of ‘brain gain’), new entrepreneurial attitudes and new international professional and personal networks (UNDP 2009).

Another aspect of migration beyond possible economic benefits are the gains to welfare. Migrants overseas may be able to send their children to local schools or access health care services or even get welfare payments if they are ill or out of work – though such benefits are often constrained by governments for non-citizens. For some, this may be one of the reasons to move: adults can find employment and save their pay packets whilst their children get what they might see as a better education than they could at home. This opens options for others staying more long term – children growing up to become residents and wage earners themselves – or returning home with savings and well-educated children.

These issues with regard to migration may seem to have little to do with aid yet receiving countries can and do make decisions regarding who can enter their countries and these can be done with development benefits explicitly in mind. For example, former colonial powers have often maintained close constitutional relationships with some of their former territories, especially those which are seemingly too small to become viable independent countries. Such relationships are usually maintained because the territories want it that way – they want to retain access to the metropolitan on favourable terms. In the Pacific Islands region, for example, we see the French territory of Wallis and Futuna being recognised as a semi-independent territory, yet its population enjoys the status and rights of French citizens. They can move freely to other French territories, such as New Caledonia, or to metropolitan France and work and gain access to all the educational, health and welfare benefits that French citizens can. Similar arrangements can be seen in the Caribbean, where, for example, the islands of Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba are classified as municipalities of the Netherlands. Thus, in an indirect way, the maintenance of these colonial ties, albeit with a high degree of local autonomy, is a form of ‘aid’: the right sort of passport can bring a great deal of benefit and higher living standards for individuals, families and whole societies. Furthermore, immigration policy should be seen in a development light: more liberal immigration regimes can be seen as a form of development assistance, whilst a hardening of immigration rules and reduced quota may well have negative development consequences elsewhere.

Another way that migration and remittances may be seen as a form of aid is in emerging forms of managed labour migration. These are separate from general immigration policies, allowing certain people to immigrate if they satisfy specified criteria (skills, age, savings etc), and instead focus on allowing workers to come into a country for a set period of time (usually less than a year but repeat ‘tours’ may be possible) to work in a particular occupation. Examples of these are found in Australia and New Zealand in the seasonal worker schemes that allow labourers from certain Pacific Islands to work mainly as unskilled or semi-skilled labourers in the agricultural sector (Box 2.5). Here there are shortages of workers – at least at particular times of the year (such as harvests) and for rates of pay at or near the bottom of the labour market.

The seasonal worker schemes are not classified as ‘aid’ programmes, nor are the costs and benefits counted under the DAC formula for ODA. Yet they are justified as having development benefits for sending countries – they are usually promoted as ‘win-win’ schemes bringing benefits for the workers and their communities as well as for the agricultural sector in the receiving countries, getting cheap and timely labour supplies. Furthermore, they appear to be popular for the sending countries: political leaders in the Pacific, for example, would like New Zealand and Australia to expand the schemes outlined in Box 2.3, so that more countries and more communities can take part. Even though we cannot easily quantify the benefits and we recognise that ‘donors’ benefit as much as ‘recipients’ (and these terms themselves are problematic in this sense), we should see migration concessions and these managed migration schemes as forms of development assistance.

Trade preferences

Another form of assistance, notable in the past, has been the way metropolitan countries have occasionally allowed imports from developing countries on special terms. These concessions operated at a time when, globally, trade barriers were higher than at present and exports from developing countries faced obstacles, such as high tariffs, if they were sent to other countries. Trade protectionism was put in place with the rationale that, by making imports from other countries more restricted and expensive, there would be an incentive for local industries to gain a competitive advantage and thus grow more rapidly. However, larger economies – often former colonial powers – also recognised that such trade protectionism dealt a blow to poorer countries, some of whom might have been former colonies. Others recognised that, even if there had not been an old colonial relationship, there was some sort of moral responsibility to offer concessions to exports from some less well-off countries. In response, systems of trade preferences were instituted in which different schedules of tariffs and/or quotas were used so that favoured exporters faced lower – or no – tariffs or had guaranteed markets allowed for a specified volume of exports.

Perhaps the largest scheme of this kind was that instituted by the European Union with regard to the former colonies of its constituent members. For many years, the European Economic Community2 used trade protectionism extensively to protect its own agricultural sectors. There were high tariffs and limited quotas on imported agricultural products, especially those which competed directly with European-produced goods. The Lomé Convention was first signed in 1975 and was renegotiated several times so that it spanned the period 1976–99. It allowed for specified volumes of exports from certain African, Caribbean and Pacific countries (ACP) (former French, Belgian, Dutch and British colonies) to enter the European market at prices mostly well above the world average. Products such as beef, sugar and bananas were covered and it meant that the ACP countries party to the agreement had an advantage compared to exporters from elsewhere. It meant that banana producers in Africa, for example, did not have to compete directly with low-cost Central American producers at least in European markets. These were non-reciprocal concessions – the ACP countries did not have to offer favourable trade terms to European exporters in return. The Lomé Convention undoubtedly provided a significant form of development assistance for those lucky enough to be a part of the agreement. Producers not only had a secure market to sell to at favourable prices but also those prices were reasonably predictable, thanks to the institution of stabilisation funds which ironed-out major price fluctuations. In effect, ‘aid’ was given by European consumers, in the form of higher retail prices paid, to producers in former colonies.

There were other preferential trade schemes. The USA, for example, recognised a schedule of preferences for the producers of certain manufactured items, again with a guaranteed quota of imports for particular products from specified countries. Although these quota schemes were gradually abolished under World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements in the early 2000s, some products and countries, such as garments from Nepal or Cambodia, can still be imported duty free into USA. As with the Lomé Convention, these trade preferences have allowed metropolitan powers to exert influence over their partners – the threat of withdrawal of benefits would have been a huge economic blow for a country falling foul of their patron. Yet there were many examples of success. Fiji is an interesting example. This Pacific Island nation of about 800,000 people faces difficulties in competing on global markets, due to its relatively small size (not allowing for large economies of scale) and distance from world markets. However, under Lomé it was able to preserve and expand its sugar industry, established during colonial times, and this formed the backbone of the economy, employing farmers, contractors and mill workers and supporting a relatively vibrant rural economy. In addition, trade preferences were later allowed by USA, Australia and New Zealand so that Fiji-made garments could be imported to these countries at low tariffs (compared to imports from, say, Thailand or Indonesia). The garment industry thrived for a time in the 1980s and 1990s and provided jobs (albeit low-paid work) for many and the industry briefly challenged sugar and tourism as the leading economic earner in the country.

This system has been termed ‘aid with dignity’ (Taylor 1987). It allowed developing world economies to focus on producing needed commodities and for these they received a good steady income. There was no hand-out of aid money, no ODA to measure; rather there was a recognition of special historical ties and responsibilities in ways which supported the economies of developing countries.

However the Lomé system and other preferential schemes could not outlast growing global trade liberalisation that became part of neoliberalism in the 1990s. Particularly as a result of US pressure to remove any trade preferences, the Lomé Convention ended in 1999 to be replaced by the Cotonou Agreement which did not have the same guarantees or security for ACP exporters and required more reciprocal concessions. Now with a much more open global trading environment, where low-cost producers exploit economies of scale and low wages, many of these former industries have collapsed. Smaller economies cannot compete; others face new forms of trade barriers (relating to biosecurity etc.); and many are forced to accept trade agreements that not only involve a loss of guaranteed markets for their exports but also the end of forms of protection for their own industries. In this sense, the loss of trade preferences as an implicit form of aid before 2000, should be seen alongside the substantial increases in ODA thereafter. A hidden form of aid to promote economic growth and employment was replaced by another more explicit form and one where the power imbalances became more marked. ‘Favoured trading partners’ became ‘ODA recipients’ and level of assistance in a holistic sense did not necessarily rise.

Loans

We have already seen that concessionary loans are counted as ODA. In other words, loans are considered a form of ODA if they are offered at terms and rates more favourable than world market rates. What is counted as ODA is not the amount of the loan principal but the difference in interest rates between the reigning market rate and the concessional rate offered (as long as it meets the DAC’s 25 per cent grant element equivalent standard). This takes our understanding of aid into new realms because it is possible that, over its lifetime, an aid loan will result in a net flow of resources from the recipient to the donor (repayment of principle plus interest even allowing for inflation) rather than the other way around. The ‘aid’ is merely a discount offered on a financial transaction. Furthermore, these concessions occur in a global financial system where all parties are far from equal. A well-developed and stable industrial economy may have an excellent credit rating and be able to secure loans from financial institutions at relatively low rates of interest (because it has a low risk of failure). Conversely, a developing country with relative instability and poor economic performance will face a bad credit rating and high interest rates. In other words, precisely those countries that need loans for development have to pay a lot more than well-off industrialised economies. For many developing economies, obtaining loans on the open financial market for, say, a large infrastructure project or a hydroelectric dam, is both difficult and expensive.

Aid in the form of concessionary loans, can therefore be a critical source of development finance for poorer economies. International financial institutions, major development banks in particular, play important roles here. Development Banks, such as the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, BancoSur or the African Development Bank, operate in an interesting way. They are backed by large donor economies (USA, Japan, Germany, France, UK etc.). These donors are able to use their own good credit rating to raise (and guarantee) loans and then pass these favourable terms on to selected recipients, who meet the requirements of the bank concerned. Projects are closely vetted and, in theory, their development benefits and ability to generate revenue to repay the loans are laid out before the loan is approved. Such loans, by the World Bank for example (Box 2.6), have been highly significant sources of finance for development projects across the developing world. In most cases, although they were relatively tightly planned and monitored, they did allow borrowers to use the funds to purchase inputs on the open market. ‘Multilateral’ agencies (with many donors and many recipients) seemed to escape the ‘tied aid’ problem.

Not all funded projects succeeded by any means, and there has been widespread criticism of some of the lending policies of the World Bank (see Box 2.6) and others in the past (see Toye et al. 2013). These have concerned not only the ability of governments to repay the loans but also factors such as harmful environmental and social impacts associated with the free-market neoliberal-inspired restructuring upon which such loans are conditional.

Loans from the World Bank and other institutions are counted as ODA as long as they satisfy the 25 per cent concessional element, as are the frequent grants they make (funds given without a requirement to repay) often alongside the loans. However, we are beginning to see a new global financial landscape appearing where new lenders outside the OECD/DAC framework are appearing. These are institutions whose lending is sometimes not as transparent as their established counterparts – terms and conditions are shielded because of their economic or political sensitivities. In addition, many of these new development concessional loans are being offered by a single donor – China in particular – and they are very much of the ‘tied aid’ form: materials, equipment, technical expertise, even labour, must be purchased from the donor.

However, an interesting initiative is the ‘New Development Bank’ which began operations in 2016 and has its headquarters in Shanghai. Its five founding members, all of whom contributed $US10 billion each to the Bank’s authorised capital, are the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). This bank will focus on infrastructural and energy projects and is likely to have a significant impact on development finance globally, augmenting the conventional sources such as the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and World Bank. Initially it is likely that most lending will be to projects within the BRICS countries but this will spread beyond. Quite how the concessional elements of the Bank will operate – and how or if they can be calculated as ‘aid’ – are not clear. However, what we are seeing is a major new aid organisation appearing and working largely outside of the old OECD ‘club’.

Welfare assistance

As with these new lending institutions, there are other forms of aid that are expanding and appearing outside the conventional North–South model. We have seen that the DAC system captures aid for welfare as ODA. This includes the very large sums spent on health services or education in many forms as well as a multitude of projects and programmes focusing on issues, such as gender-based violence, women’s empowerment, community development etc. These all amount to a significant portion of the global flows of ODA (see Chapter 3).

However, not all such forms of welfare assistance can be tracked through the ODA system. We do not consider here the unofficial forms of welfare assistance carried out by individuals and families (relatives paying and caring for children attending schools and universities overseas, or family members being sent to receive health care in another country). Such flows would be nearly impossible to calculate. Yet we do recognise that some important forms of welfare support do exist and are not adequately recognised or measured.

There is also the issue of the work of civil society organisations. NGOs such as Child Fund and World Vision and a host of others raise funds in the West and provide health and education services elsewhere. Some of this might be captured in official statistics; much is not. The phenomenon of child sponsorship, for example, is responsible for large sums being transferred across the globe (Wydick et al. 2013).

Emerging aidscapes: South–South co-operation

But it is with some of the non-traditional (non-DAC) donors that some of the major flows of aid can be seen (at least in part). The granting of scholarships by donors to students from the developing world to attend institutions in the donor countries has long been a popular form of aid. Selected students get a chance to broaden their education and life experiences overseas whilst donors also benefit by establishing networks of understanding and relationships that persist beyond the time at school or university. These scholarships from DAC donors are counted. However, new donors see similar benefits in scholarships. Having students from another country study in the donor’s own institutions builds and strengthens ties and open up channels for future collaboration. Language and cultural barriers are weakened as more people are able to operate in two or more worlds. China, in particular, has seen great merit in such scholarship schemes and has signalled major expansion of this form of support.

Similarly, medical training is a way of building good diplomatic relationships by utilising the donor’s own expertise and institutions. In this regard, the example of Cuba is notable (Box 2.8). By many indicators, Cuba would be classified as a low-income country, apparently in need of development assistance. Yet since the revolution of 1959 it has taken particular pride in prioritising the health and education of its own citizens. It has invested heavily in these services, arguably at the expense of other sectors, but its education and health indicators stand up extremely favourably by international standards. As part of this investment, Cuba has developed a particular model of medical training that is different from most Western models. Eschewing high-tech medical models which see heavy investment in large hospitals, expensive equipment and high-end medical training, Cuba’s model focuses instead on primary health and in the provision of well-trained professionals serving the needs of all communities. It is a model that seems to suit cash-strapped developing countries and Cuba has been active in offering not only its own doctors to serve overseas, but also to open its training institutions to students from overseas (Box 2.8).

The examples of Chinese educational scholarships and Cuban medical training, then, are interesting as they show how aid is moving in new and innovative directions. Neither example is free of criticism and some charge that it is not synchronised with local systems, languages and practices. However, it is likely they will continue to expand and we may see other examples, such as scholarships to study in India, appear in future.

In this context, we can begin to understand more generally how ‘aid’ is being reconstructed, less as a dual Northern donor/Southern recipient binary model, and more as a complex web of economic relationships linking countries of the South in systems of co-operation and joint development. It is offering a major challenge to the way we think about aid and indeed to the very concept of development (Kim and Lightfoot 2011, Kilby 2018).

As noted briefly in Chapter 1, it has been suggested that we are seeing a new aid world – or even a ‘post-aid world’ emerging (Mawdsley et al. 2014). A key part of this new aid landscape is what Mawdsley terms the ‘Southernisation’ of aid: ‘A more polycentric global development landscape has emerged over the past decade or so, rupturing the formerly dominant North–South axis of power and knowledge’ (Mawdsley 2018: 173). Previously, the DAC-centred aid world was predicated on the power of the main Western donors and their attempts to ‘socialise’ emerging economies, such as Korea, so that they would behave like the established donors, eventually joining the DAC and abiding by its conventions. However, China especially, but also other growing economies, such as India and Brazil, have chosen to operate rather differently and largely outside of the DAC framework (Mawdsley 2010, 2012a, 2012b).

They have pursued new practices and languages: ‘South–South co-operation’ has adopted the mantra of win-win development, whereby new economic and political relationships are forged. These may involve net flows of both financial and nonmonetary resources from one country to another (what we might see as ‘aid’) but aid is not the primary basis of the relationship. China is open about how these relationships are for its own geopolitical and economic benefit, as well as for its partners. It is a different ethos of assistance, moving from one based on supposed altruism to one built upon a vision of explicit shared benefit.

Loans (concessionary and otherwise), scholarship schemes, business deals, investment and gifts all cement relationships which have the overt goal of mutual benefits. And this challenges the power relations implicit in the DAC-centred aid model. Wealthy and powerful donors giving to supposedly poor, weak and needy recipients are replaced by a web of reciprocal and complex trade, investment and technological interactions which appear to be amongst partners of equal standing, even if not of equal wealth.

These are significant and growing challenges to the established aid world centred on Washington or Paris. We argue in Chapter 4 that Western donors have reacted to this South–South challenge by adopting their own ‘retroliberal’ approaches to aid, eschewing the strong poverty-focus of the earlier neostructural regime and instead promoting narratives of ‘shared prosperity’, sustainable economic growth’, and unashamed donor self-interest. Yet we also add a note of caution. We would answer Kilby’s (2018) questioning whether ‘DAC is dead’ in the negative. Despite the undoubted Southernisation of aid, despite the rise of China, despite the retroliberal turn and despite the growing complexity and obfuscation of aid, the DAC system is still very much in place, the narratives of ‘aid’ and ‘poverty’ are still strongly adhered to, and the flows of resources from the Global North to the South in the form of ODA are still very substantial and showing little sign of ending.

Conclusions

We began this chapter by suggesting that ‘aid’ was a relatively simple concept, to do with ‘assistance’ and ‘help’ and implying that better-off countries aid those less well-off. In relation to international aid we then saw how there exists a relatively precise definition in the form of ODA which is widely accepted and measured internationally. Aid as ODA requires assistance to be spent on development and improving welfare, it should flow through official channels and it must involve a net benefit for the recipients.

However, as we broadened our discussion, we found that these fairly precise meanings are not so clear in reality and present many difficulties in terms of their measurement. The interpretation and quantifying of ODA has experienced some changes over time and there are many forms of assistance, such as trade and migration concessions, that are not counted. We might also suggest that the notable increases in ODA since 2000 have come at a time when the other forms of assistance, especially trade preferences, have been eroded. Yet despite these complexities of definition and the need to keep a watch on ‘non-ODA’ forms of aid, ODA remains the most useful and precise concept for us to use to analyse key aspects of international development assistance.

Similarly, the parties involved in aid have altered over time. When we adopt the DAC framework and just look at ODA, there is a reasonably clear global landscape of aid with donors largely being the developed countries of the Global North (North America, Western Europe, Japan and Australasia – all members of the OECD) and recipients being located largely in the Global South (Africa, Asia, Latin America and Oceania). Yet this geography is being transformed in different ways. A number of countries have undergone a transition from low- to middle- or high-income status – Korea, Singapore, Chile and Saudi Arabia for example. Some have joined the OECD/DAC ‘club’ and become donors themselves. Some, India included, have become a recipient and a donor simultaneously. Others again, such as China, have forged their own path, also becoming substantial donors but adopting their own ways of operating. These forms, including concessionary loans, grants and forms of welfare assistance lie outside the DAC framework. Increasingly, then, the old North–South dichotomy is no longer relevant. In later chapters we will see how new forms of South–South co-operation and the emergence of non-traditional donors are lining up alongside the changing scene within the OECD aid framework.

Therefore, what we have seen is that aid is not only complex, it is rapidly changing. As Sears suggests, ‘aid is not a static measure but rather a moving target’ (2019: 141). We need to adopt a broad view of what we mean by ‘aid’, who we see being involved, and how aid relationships and flows work in practice. In the chapters that follow we start by examining the detailed geography of aid, focusing mainly on ODA and seeing where aid comes from and where it goes.

Summary

Aid is a broad concept and must include all sorts of ‘assistance’ as well as policies that are designed for mutual benefits for donors and recipients.

Aid worldviews have shifted significantly over time from those based on relief, to those targeting development, advocacy, self-interest, and latterly private sector development.

These aid worldviews have evolved chronologically to an extent, but there are areas of policy and conceptual overlap.

We may be entering a post-aid world, based on ‘shared prosperity’ and ‘South–South’ co-operation among other things. The motivations for aid have become highly complex and difficult to pick apart to the extent that terming it ‘aid’ at all is contestable.

The official OECD DAC definition of aid has changed over time to become more inclusive. However, it still fails to capture many types of aid that are not measured, such as migration and labour schemes, trade preferences, concessional loans, and welfare assistance.

On the other hand, ODA has come to include some financial flows, which are mostly or fully retained in donor economies, such as in-country refugee costs.

A number of countries, such as China, are not in the DAC, yet their aid activities are large and growing.

There is increasingly a blurred line between donors and recipients as development patterns shift and geopolitics change. The resultant geography of flows is highly variable and complex.

We discussed both tied and untied forms of aid, noting that a shift away from the former has now been, at least in part reversed.

There has been a large shift in the Global South towards what some have called ‘South–South’ co-operation with scholarships, training schemes and other forms of mutual assistance patterns. China has been especially prominent in evolving such models.

Notwithstanding the ‘southernisation’ of aid we argue that the traditional DAC form of ODA remains the most important of all and that we do not yet live in a post-aid world.

Discussion questions

Discuss the evolution of aid worldviews over time and the extent to which these worldviews overlap.

What aspects of ‘aid’ are not captured in the official OECD DAC definition and what are the implications of this for understanding the patterns and impacts of aid?

What aspects of ODA are included in its definition, but might be questioned as ‘aid’ from donors to the Global South?

What do analysts and observers mean by South–South co-operation and to what extent is it replacing more traditional forms of ODA?

To what extent is the hypothesis of a ‘post-aid’ world a reasonable assessment?

Websites

World Bank: https://www.worldbank.org/en/who-we-are

OECD/DAC: http://www.oecd.org/dac/development-assistance-committee/

Devex: https://www.devex.com/news

Lowy Institute (Australia) on China: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/issues/china

Notes

1 In DAC statistics, this implies a grant element of at least …

• 45% in the case of bilateral loans to the official sector of LDCs and other LICs (calculated at a rate of discount of 9 per cent).

• 15% in the case of bilateral loans to the official sector of LMICs (calculated at a rate of discount of 7 per cent).

• 10% in the case of bilateral loans to the official sector of UMICs (calculated at a rate of discount of 6 per cent).

• 10% in the case of loans to multilateral institutions (see note 5) (calculated at a rate of discount of 5 per cent for global institutions and multilateral development banks, and 6 per cent for other organisations, including sub-regional organisations).

(OECD 2019b)

2 The European Economic Community was established in 1957. It grew in membership from the original six and in 1993 became the European Union, which in 2002 enacted a currency union for the majority of the members. There are currently 27 members. The EU deals with common economic, social, and environmental policy and as a multilateral body has an important role on the international stage – including in the aid world.

Further reading

Alfini, N. and Chambers, R. (2007) ‘Words count: Taking a count of the changing language of British aid’, Development in Practice 17(4–5), 492–504.

Kilby, P. (2018) ‘DAC is dead? Implications for teaching development studies’, Asia Pacific Viewpoint 59(2), 226–234.

Kumar, R. (2019) The Business of Changing the World: How Billionaires, Tech Disrupters, and Social Entrepreneurs Are Transforming the Global Aid Industry. Beacon Press, Boston.

Lancaster, C. (2007) Foreign Aid: Diplomacy, Development, Domestic Politics. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Mawdsley, E. (2018) ‘The ‘Southernisation’ of development?’, Asia Pacific Viewpoint 59(2), 173–185.

Swiss, L. (2016) ‘World society and the global foreign aid network’, Sociology of Development, 2(4), 342–374.

Toye, J., Harrigan, J. and Mosley, P. (2013) Aid and Power-Vol 1: The World Bank and Policy Based Lending. Routledge, London and New York.