1Aid

Learning objectives

This chapter will help readers to:

Appreciate in a broad sense the historic roots of aid and its present geography

Understand the role of aid in the global economy and how this is changing

Debate the justifications for and motivations of aid from different perspectives

Understand in outline form the arguments of critics and supporters of aid

Introduction

In the Global North, the term ‘aid’ often conjures up images of human suffering being met by assistance from outside. Such assistance has become an integral part of the way we conceive and practice development. We see aid as a means to alleviate suffering but also to promote development and self-reliance. Such views have been reinforced over the years by well-meaning public campaigns which have encouraged the public to both dip into their own pockets to contribute to relief efforts and pressure their governments to increase their aid budgets.

However, as we will see, there have been many critics of aid: those who have suggested that aid does not achieve what it says it aims to; that it merely acts as another weapon for the rich and powerful to exploit the poor and vulnerable; or that it actually distorts the economy and makes poverty worse. These debates continue to rage. Some commentators have also suggested that the age of aid is coming to an end – we are entering an historical ‘post-aid’ period where new actors, new ways of operating and challenges to the old simplistic world order of rich aid donors and poor recipients, are ushering in fundamentally different sets of economic and political relationships and power structures (Mawdsley et al. 2014; Mawdsley 2018; Janus et al. 2015; Gulrajani and Faure 2019).

Yet we contend that forms of aid from some countries to others are still significant features of the global economy. Furthermore, there are signs that aid will continue to be used to support global ambitions to alleviate poverty, tackle the effects of climate change, lessen inequalities and promote economic growth. The Sustainable Development Goals of 2016–30, in particular, set some lofty objectives and specific targets to address major global challenges for the next decade (see Box 1.1) – and if these are to be pursued seriously, they will require significant funding from both public and private sources. Aid, in its many forms, will remain important for global development efforts for years to come. Therefore, there is a need for us to understand aid in its many forms and how it has changed over time, to see how it is delivered, to question its effectiveness and to identify lessons for the future.

In this book we aim to better understand what aid is, and has been, where it comes from and where it goes, how it is dispersed and what its impacts are. We need to question whether any observed shortcomings are a result of a fundamental problem with aid, or merely the result of bad practices. We need to look at the motives and policies of donors as much as we do the conditions and efforts of recipients. We provide students of development and those who work, or intend to work, in the development and aid sector with a broad picture of the present aid ‘landscape’, together with some key concepts and methods, and an overview of debates concerning the impacts and possible futures of aid. We adopt a broad definition of ‘aid’ and appreciate its complexities and dynamism, with emerging new actors and modes of operation, though we continue to focus on dominant framings of aid, key agencies and mainstream ways of operating, as seen in the OECD-defined definitions and measurements of ODA.

In this first chapter we briefly outline the position of aid in the global economy and the motivations for giving and receiving it before examining some of the key criticisms and debates. The core chapters of the book then seek to address some key questions:

- What is aid? How is aid defined and measured in various ways and how might various forms of ‘assistance’ or ‘co-operation’ be considered aid, or not? (Chapter 2)

- What is the geography of aid in terms of volumes and flows? Who are the major donors and recipients and what are the key aid agencies? (Chapter 3)

- How has aid changed over time? How have the principles, objectives and methods of aid delivery evolved through various historical ‘regimes’ of aid? (Chapter 4)

- How is aid delivered? In what forms does aid appear, what are the various scales of operation and how do these different aid ‘modalities’ involve different actors? What new forms of aid delivery are emerging at present? (Chapter 5)

- Does aid work? How can we start to understand the effects of aid on economic systems, governance, welfare and social structures – and what debates exist regarding the impacts of aid? (Chapter 6)

- What have we learned about effective aid and what is the future of aid? (Chapter 7)

Aid and development

Before proceeding further, we need to pause and consider what we mean by ‘aid’ and ‘development’. Firstly, although we will examine the definition of ‘aid’ in some depth in Chapter 2, here we can suggest that aid involves some broad idea of ‘help’ or ‘assistance’ from one party to another. It may – and certainly in practice almost always does – involve two-way flows (whether these involve financial resources, political favours, technical advice, trade agreements or movement of people) but ‘aid’ should imply that at least the initial flow is from a donor to a recipient and that this involves some notion of assistance. In this book, we focus on aid which has some sort of development or humanitarian objective – such as economic growth, improved welfare or disaster relief – and most commonly we resort to the widely used definition of development aid as ODA, and focus on aid which is delivered and received by state and civil society agencies (rather than, say, aid given within families), although we acknowledge that other forms of aid may exist (Table 1.1).

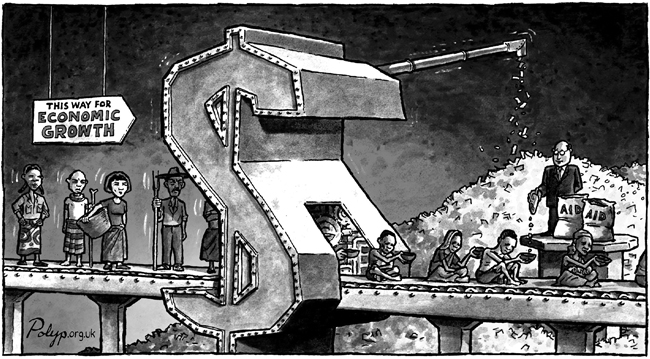

We should also note that the very concept of aid has been challenged. Writing in The Development Dictionary, Marianne Gronemeyer not only points to the ‘perversion of the idea of help’ (2010: 57), through military aid or food aid (allowing the spread of global corporations selling seed grain), but also sees aid as a form of ‘elegant power’: ‘elegant power does not force, it does not resort to the cudgel or to chains; it helps’ (2010: 55). To her, development aid is not innocent, welcome or unconditional but ‘aid’ is a linguistic device used to pursue the self-serving objectives of the ‘giver’ and impose power over the ‘needy’.

‘Aid’: a general term referring to assistance that can come in many forms (financial, technical, material or non-material) and which may involve two-way flows of costs and benefits |

‘Development aid’: resources, whether financial or technical, given by various donor agencies to assist poorer countries and communities undertake economic, social and political development. It focuses on building the long-term capacity of economies and institutions to undertake their own development in future. |

‘Humanitarian aid’: a short-term response to provide needed food, shelter, medical supplies and other assistance following natural disasters or civil disturbances and violence. |

‘Official Development Assistance’ (ODA): ‘government aid designed to promote the economic development and welfare of developing countries. Loans and credits for military purposes are excluded … Aid includes grants, ‘soft’ loans (where the grant element is at least 25% of the total) and the provision of technical assistance’ (OECD 2019b). |

‘Development co-operation’: joint actions and contributions from different parties (usually governments) to pursue strategies and activities that address defined development goals and which may accrue benefits to all partners. |

The task of defining ‘development’ is even more complicated than agreeing on meanings of ‘aid’. Most conventional understandings of development suggest improvements in material standards of living, commonly measured by national income (e.g. Gross National Product (GNP)/Gross National Income (GNI) per capita). These approaches highlight the objectives of increasing economic activity, employment, productivity and growth and they typically use aggregate approaches, assuming that overall growth and improvement will filter down to all in an economy. We see this approach prominently in discussions of aid and its effects: how (or if) aid promotes economic growth or helps create jobs, for example. Yet we also know that ‘development’ can – and should – address more qualitative and less overtly material aspects such as human rights, well-being and happiness, individual freedom, social justice, sustainability, dignity and security. Furthermore, development goes deeper than aggregate processes or measurements: social inequality, political power imbalances and economic systems mean that there are both winners and losers in development and our focus arguably should be on the poor, marginalised and dispossessed rather than the economy as a whole. Indeed, it is often these aspects, particularly recognition of human suffering at an individual or community level, that is used to portray ‘need’ and justify the giving of aid. In this book, we adopt this broad approach to development, seeing it as a complex and contested notion of ‘improvement’ or ‘good change’ (Chambers 2004), though conceding that processes of development can lead to both positive and negative outcomes for different parties.

Therefore, we can see aid and development as difficult concepts to define precisely. They are also fluid. In this book, we suggest that aid has changed significantly over time, often in response to different contemporary understandings of what development is or should be. Certain understandings and theories have become embedded as broadly agreed and dominant approaches in the delivery of aid adopted by key agencies at different times in recent history. These are each associated with different political ideologies, motivations, power relationships, methods of operating and institutions. They are ‘regimes’, or collections of ideas, institutions and practice, that exist for a period of time before giving way to another dominant approach and they are similar in this sense to paradigms. In Chapter 4 we will suggest that four main regimes of aid can be identified since 1945: modernisation, neoliberalism, neostructuralism and retroliberalism. These are important to understand for they have shaped the aid world in quite marked and varied ways over time. Elements of each have been dominant at different times, though more than one may be evident at any one moment in time.

Aid in the global system

International development assistance has been one of a number of major flows of financial capital across the globe. It sits alongside foreign direct investment (FDI), private remittances and international trade as one of the key elements of the global economy. As with other forms, the flows of aid are not all one-way from rich to poor countries, for there are return movements of interest on and repayment of assistance loans and (even though such loans are generally given on a concessional basis) the net flow over time may actually be from poor to rich. Yet aid is the one flow that is predicated on a deliberate intervention in the global economy to change the flow of resources so that one group of countries and societies (‘developing’1 countries) can benefit from assistance from another (‘developed’ countries).

In relative terms, aid2 is not the major source of financial flows to developing countries. It is outstripped by both private remittances (personal savings or money people send to family members and others ‘at home’) and FDI. In 2015 aid, or as it is known formally ODA, accounted for just 16.5 per cent ($US179.5 billion) of total resource receipts to developing countries (down from 18 per cent in 2000) (OECD 2017 – see Table 1.2). By contrast, remittances accounted for 35 per cent and non-ODA flows3 for 48 per cent in in the same year. However, if we look at these flows to the poorest countries (the OECD’s definition of ‘least developed countries’ (LDCs)) the picture is rather different. In 2015, the share of ODA was 47 per cent,4 remittances were 35 per cent and other flows just 18 per cent. In other words, as we should expect, middle income developing countries depend more on market flows and remittances whereas LDCs still rely heavily on aid (and increasingly remittances) for their external financial resource inputs.

(a) Total Flows to Developing countries (%) |

||||

|

2000 |

2005 |

2010 |

2015 |

Remittances |

23 |

29 |

30 |

35 |

Non-ODA |

59 |

50 |

54 |

48 |

ODA |

18 |

21 |

16 |

17 |

Total $US mill |

449806 |

643862 |

899701 |

1086007 |

(b) Flows to Least Developed Countries (%) |

||||

Remittances |

22 |

20 |

29 |

35 |

Non-ODA |

20 |

12 |

15 |

18 |

ODA |

57 |

68 |

57 |

47 |

Total $US mill |

36018 |

64311 |

81270 |

100208 |

Notes: gross disbursements on a three year moving average, $US mill at 2015 prices.

Non ODA includes Foreign Direct Investment, other official development flows, export credits, private flows at market prices and private grants.

Data extracted from OECD (2017)

Although we see some signs of relative decline in the contribution of ODA to the economies of developing countries as a whole in recent years, it is important to note that it has been a significant feature of the global economy for the past 40 years. Less well-off countries have had to rely on international development assistance as private and market flows of resources from outside have lagged. Also, we can see from Figure 1.1 how ODA has varied over time since 1970. In real terms, adjusting for inflation, ODA broadly grew during the 1970s, plateaued during the 1980s, fell in the 1990s and has grown substantially – basically doubling – since 2000. It has been mainly directed to developing countries in Asia and Africa, though there has been a large growth in the ‘unspecified’ category in the past decade.

Total official donors, disbursements $US mill constant 2017

Source: www.stats.oecd.org

Over this 50-year period, aid has been part of a series of global ‘projects’ according to McMichael (2017) – the UN Development Decade launched in 1961, the MDGs of 2000–15 or the present SDGs of 2016–30 – with the stated, and sometimes contested, intentions of promoting development and alleviating poverty on a very large scale. Viewed historically, aid has been the main tool used to transfer resources from richer to poorer countries in the name of these grand projects and ambitious goals.

Justifications for aid

Why should aid be given? Why have donors continued to spend many millions of dollars over several decades on aid projects and programmes often far from their own shores? And why do governments and communities in developing countries continue to receive assistance when there seem to be real doubts about its effectiveness and the conditions that have to be met in return for aid?

Altruism

In some ways, a superficial answer to these questions is very simple: it is altruism – a selfless concern for the well-being of others. Aid does good. It eases human suffering and supports efforts to help people become more prosperous and self-reliant. It is based on a basic human sentiment of generosity – giving makes us feel better individually and collectively – and aims to build goodwill. These are powerful touchstones for aid. They help promote the success of public appeals for donations and allow donor governments to justify the use of taxpayer funds to their electorates. Aid, at its most basic level, does have a high (if variable) degree of popular support. And on the recipient side, aid is gratefully received as it supports efforts by governments and civil society who lack resources to address the pressing needs of their communities. Altruism constructs a dualist model of aid: there are generous and selfless donors on one side; needy and grateful recipients on the other; and there is a one-way flow of resources from the former to the latter.

Yet behind these superficial justifications of aid lie much more complex and contested motives and structures. Altruism may operate at one level to generate support for aid, but effectively it is the self-interest of donors (and recipients) that plays a greater role in shaping the nature and direction of aid and the way it is delivered. There are several different facets to self-interest: economic, political/diplomatic, and welfare, peace and stability have been seen as interacting factors driving Western aid since 1945 (Griffin 1991).

Economic benefit

Economic factors are central to the aid ‘industry’. Aid is seen to help promote economic activity and growth – creating employment, providing new goods and services and expanding the economic options available for poorer societies. The provision of capital and technology through aid is seen by many to accelerate investment, growth and employment. This argument is often used to suggest that economic growth ultimately reduces poverty. From the recipient side, aid provides resources that are otherwise in very short supply domestically or too expensive to obtain on the global market. Aid can reduce the need for debt and ease balance of payments problems. For donors, there are also benefits. Economic aid, in the form of loans, capital equipment or technical advice, helps align hoped-for growth in the recipient economy with the trading interests of the donor economy. Investment and trading opportunities open alongside aid, helped no doubt by recipient governments willing to lift restrictions on these for companies from donor countries. And if and when economic growth occurs, consumers in recipient countries are able to buy more imports or seek bigger commercial loans or look to attract more foreign investment. Such uses of aid, then, help construct economic systems and relationships that bring multiplied benefits back to donors in the long run as well as to recipients in the short term. Linked to these economic motives for aid, economic restructuring and trade liberalisation conditions are often attached to aid.

Political and diplomatic considerations

There are also political/diplomatic justifications for aid: aid features importantly in the conduct of foreign policy by all sides. Aid donations from one government to another are rarely – if ever – given without some sort of either overt or tacit understanding that there is an expectation of a political return of some kind. This may involve recipients giving their diplomatic support to a donor’s position on the global stage (a vote at an international forum on whaling, a bid for a seat on the United Nations Security Council, or diplomatic recognition or not of Taiwan, for example). In this case, a recipient’s status as an independent sovereign state with voting rights is a critical economic resource that can be ‘traded’ for aid receipts. Aid is also used as an instrument to influence domestic policy in recipient countries. Donors have, in countries such as Kenya or Fiji, withdrawn or threatened to withdraw aid from a government they think lacks democratic legitimacy or has a poor human rights record in the hope and expectation that policies will change. Political and diplomatic gains can be sought by donors in more subtle ways. The giving of tertiary education scholarships to study abroad (in the donor country) has long been a way of building relationships with the future elites in recipient countries and aligning them with donors’ values, ways of life and ways of working. Similarly, technical assistance can help reconstruct recipient institutions (customs and immigration, police, drug enforcement, finance etc.) so that they parallel and interact smoothly with those of the donor. Finally aid has a political benefit for donors domestically and internationally. Rising aid budgets help mollify domestic pressure groups calling for action on poverty and debt reduction and internationally, a generous aid budget is a sign that a donor government is a ‘good global citizen’ which acts responsibly and can be welcomed on the international stage. For emerging economies, making a transition from being an aid recipient to becoming an aid donor (China, India, Chile, Brazil etc.), is also a tangible sign of success and of graduating to join the well-off countries of the world.

Welfare, peace and stability

As well as building economic activity and diplomatic relationships, aid is also given and received to promote welfare development in a strategic and more long-term way. When aid is used to help provide better education and health services, especially when this is done through local institutions, it can bolster public support for governments that donors back, or reduce support for separatist or opposition groups. More peaceful and stable countries with good public services and an expanding economy are also less likely to become homes for subversive and/or violent groups and, as a consequence, sources of refugee flows. In this way, welfare spending offshore by donors is seen as a way of lessening the chance of having to spend more at home (in hosting refugees or combatting terrorism, for example), and is also likely to win popular political support, particularly in polities where populist nationalism now holds sway (such as the USA and UK). Furthermore, more forward-looking donors might see benefits in welfare-related aid projects and the ways this can assist the regulated labour flows. Aid can support particular projects in education and training that will equip future migrants or seasonal workers with the skills to work in donor countries when and if required. In this way, aid can maintain a structure that provides cost-effective social reproduction of a reserve of workers offshore who can then be welcomed and regulated if and when the donor requires.

All these economic, political and strategic justifications for aid thus take us a long way from the simple notion of altruism and the dualistic model of aid relations. Instead of a simple rich-poor divide and a one-way flow of resources, we have a complex world characterised by increasing interdependence through aid and marked return flows of resources and political ‘capital’.

Source: Cartoon by Polyp reprinted by kind permission.

Before we leave this initial look at justifications for aid, we should note that not all aid involves government-to-government relationships and this rather cynical view of the hidden motives for aid. Private aid flows, from individuals to and through non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to recipient organisations and communities, and the involvement of wealthy private philanthropists does not accord well with this view of deeper economic and political motivations for aid. A concern for the well-being of others is clearly a key reason people give freely of their own money. These individual altruistic motives flow through to the operations of many development NGOs in both donor and recipient countries. Civil society organisations thus seem to be more attuned to the conditions, needs and aspirations of poorer people and more motivated by concern for them. Yet, even here we should also ask if these are the only motives at play. Some faith-based NGOs are undoubtedly guided by the underlying humanitarian principles of their religion, yet they can also seek to persuade others – recipients – of the virtues of their faith even if just by example. Others may be more explicit, building schools and introducing curricula that are not fully secular, or having proselytising activities alongside aid projects. Other NGOs may use aid not so much as a way of convincing recipients of their values and beliefs but to demonstrate the importance of their broader missions. Many development NGOs have a particular set of objectives – environmental protection, family planning, clean water, domestic violence etc. – and understandably focus their aid projects on these concerns. Overall then, donor governments may use aid as a foreign policy tool and NGOs may use aid as a public advocacy tool. In both cases the worldviews and strategic objectives of donors are as influential, and perhaps more so, than those of the recipients.

Aid critics

There have long been critics of aid and debates concerning its effectiveness and impacts rage through to the present day. While we are not in a position to resolve these debates here, we can outline here some of the main criticisms, from various ideological and theoretical positions, before we turn later in the book to examine them in greater detail.

Early criticisms of aid hark back to the ideas of Thomas Malthus and his followers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries with regard to the poverty that arose out of the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain and Europe more broadly. They believed that assistance for the poor merely led to increased survival rates and higher population growth which used up available resources and therefore perpetuated poverty. This idea was echoed in the 1960s by writers such as the ecologist Garrett Hardin, who used the metaphor of a lifeboat for Planet Earth. This argument suggested that, in the face of disaster, we are not able to help everybody who is adrift in a sea of suffering; by putting more people on the lifeboat (of prosperity) we cause it to sink, thus leading to the demise of all on board (Hardin 1974). In this conceptualisation, tackling poverty actually makes everybody worse off. In a similar line, other less graphic and simplistic views, include those personified by economists such as Peter Bauer. Bauer (1976) argued that aid perpetuated and even magnified poverty, rather than eliminating it. This was because, he believed aid led to governments becoming more powerful, corrupt and inefficient and that individual effort and enterprise would be suppressed. As we will see these ideas eventually played a critical role informing the neoliberal approach to aid and development that is associated with the ‘right-wing’ of politics (see Chapter 4).

Equally staunch in their criticisms of aid were writers more on the other, ‘left-wing’, side of ideological spectrum. Terese Hayter in 1971 published a book entitled Aid as Imperialism that focused on the work of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank and United States Agency for International Development (USAID) in Latin America. She argued that donors used aid as a tool to control developing countries in order to further their own economic and strategic objectives. Her work paralleled that of dependency theorists of the time who believed that global trade and capitalism created underdevelopment and poverty in the ‘periphery’ (often referred to at the time as the ‘Third World’) as a consequence of the development of wealth in the ‘core’ (the industrialised economies of Western Europe, North America and Japan). Though poles apart ideologically, Bauer and Hayter both felt that aid did little to tackle global poverty and in fact perpetuated it.

We can see parallels of these views in present aid debates, though the ideological lines are not always quite as stark. There are neoliberal economists who hold to Bauer’s views. The Australian Helen Hughes (2003) for example, argued strongly that ‘aid has failed the Pacific’. Dambisa Moyo in her book Dead Aid (2010) similarly felt that the billions spent on aid in Africa actually worsened the conditions there and led to a dangerous dependence on aid among many governments. Another economist, William Easterly (2006, 2007, 2008; Easterly and Pfutze 2008) has also been highly critical of the way aid has been implemented but he has taken a rather more liberal view, pointing not to macroeconomic distortions but to the way the rights of the poor have been ignored (also Glennie 2008). For him, aid which focuses on meeting the material and technical needs of the poor – mosquito nets or improved sanitation for example – fails to address the fundamental causes of poverty which lie in the lack of individual rights and freedoms of the poor.

Aid supporters

On the other hand, there are vocal proponents of aid. There have been prominent celebrity champions of anti-poverty campaigns, people such as Bono or Bob Geldof (Box 1.3), and these have been associated with campaigns such as Live Aid, Comic Relief, or Make Poverty History. NGOs, such as Oxfam have also been advocates for aid (Oxfam 2010). There have also been wealthy philanthropists such as Bill and Melinda Gates who have put much of their own wealth into aid projects. Perhaps the main academic support for aid, and a critical opponent of Easterly, has been Jeffrey Sachs. His 2005 book, The End of Poverty, is an optimistic view of the potential of aid to address the fundamental needs of the poor. To him, more aid, more focus on things such as improved seeds and irrigation, and targeting the combatting of malaria, tuberculosis and AIDS is vital so that people can escape the poverty trap. Aid can tackle poverty and once this is done, better governance and prosperity will follow. Sachs was influential both in measures to meet the MDGs and in the drawing up of the SDGs.

Thus, we are faced with a world that does not agree on the motivations, rationale, impacts and even need for aid. Academic and popular debate continues and there are growing schisms in terms of donor policy. While aid has generally increased steadily in the past 20 years (Figure 1.1), there are signs in recent political changes in USA and UK in particular, that governments want to reduce aid and focus more on their own economies. We seem to be at a critical juncture with aid: will we subscribe to the optimism of Sachs, pursue the new targets of the SDGs and continue to sustain aid increases; will we heed the criticisms of Easterly and Moyo and seek to reduce or radically transform aid; or will we follow the increasingly inward-looking foreign policy signals of populist nationalism such as that which currently exists in USA and reduce and re-direct aid budgets?

Conclusion

This brief introduction to aid and development has opened the door to a myriad of questions and issues to explore. What might have started as a simple dualistic model has been revealed to be very complex and contested. We know that aid has resulted in very large commitments of funds over several decades and this has been done in the name of humanitarian relief, helping others and promoting development. But we can see that the reasons aid is given run much deeper than this, there is no simple linear flow of resources from rich to poor, and there is not even agreement on whether aid actually does any good!

Summary

In this chapter we:

Outlined the contents of this book and the major questions that we seek to explore. These included questions on the definition of aid, its geography, and history as well as how it is delivered, whether it works and what the future may hold.

Discussed what is meant by aid and how definitions and therefore measures are often critically challenged and yet crucial to understand in given contexts.

Discussed the link between the current SDGs and how these relate to current and historic aid practices.

Explored briefly motivations for aid. We saw that justifications frequently included both altruistic and strategic motives.

Introduced the idea that aid can be given for economic, political/diplomatic, and security reasons in terms of strategic motives and noted that these factors overlap in different ways in various places and over time.

Outlined the broad contours of the debate concerning critics of aid from both the right and left wings of politics.

Introduced outline arguments that support the use of aid from both a political and academic point of view.

Looked at the role of celebrities and public campaigns in the public perception of what aid is and what it is for.

Discussion questions

What are some of the main justifications for giving aid and how can these overlap?

How do we define aid and how is it measured?

Discuss the main arguments for and against aid.

How do the 2015 SDGs relate to the concept and practice of aid?

Websites

Does aid work?: https://www.oxfam.org/en/multimedia/video/2010-does-aid-work

The SDGs: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs and https://sdg-tracker.org/

Videos

Ed Sheeran: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LHKDAF9XKoo

Ricky Gervais: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5DgIRjecItw

Africa for Norway: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oJLqyuxm96k

Notes

1 In this book we sometimes use the terms ‘developing’ and ‘developed’ to refer quickly to countries with varying levels of income per capita and living standards. We are aware that at best these are imperfect terms that hide more than they reveal and at worst they actively discriminate and reproduce inequality. We also use the terms Global North and Global South. In addition, we draw on the further classification of ‘developing’ countries used by the World Bank and OECD. This has sub-categories of ‘low income’ (or ‘least developed’), ‘lower-middle income’ and ‘upper middle income’ countries, as well as ‘high-income’ (developed) countries (see for example OECD 2019a).

2 Measured here as ODA (Official Development Assistance) – see Chapter 2.

3 Non-ODA flows are comprised of ‘Other official development flows, officially-supported export credits, FDI, other private flows at market terms and private grants’ (OECD 2017).

4 ODA had been as high as 68 per cent in 2005.

Further reading

Collier, P. (2007) The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries Are Failing and What Can Be Done About It. Oxford University Press, London and New York.

Easterly, W. (ed.) (2008) Reinventing Foreign Aid. MIT Press, London and Cambridge.

Glennie, J. (2008) The Trouble with Aid: Why Less Could Mean More for Africa. Zed Books, London.

Mawdsley, E., Savage, L. and Kim, S.M., 2014. ‘A “post‐aid world”? Paradigm shift in foreign aid and development cooperation at the 2011 Busan High Level Forum,’ The Geographical Journal, 180(1), 27–38.

Moyo, D. (2010) Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is Another Way for Africa. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York.

Oxfam (2010) 21st Century Aid: Recognising Success and Tackling Failure. Oxfam Briefing Paper 137.

Sachs, J.D. (2005) The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities of Our Time. Penguin, New York.