6Does aid work?

Learning objectives

This chapter will help readers to:

Understand competing perspectives concerning the positive and negative impacts of aid

Appreciate the arguments concerning the economic impacts of aid, and its costs and benefits

Debate the impacts of aid on the notion of good governance, understanding both success and failures in this ambit

Understand and debate the relationship between aid and poverty reduction

Assess the evolving role of non-state actors, civil society and the private sector, in aid flows

Consider the transparency of aid allocation within donor countries and whether this needs to be enhanced

Introduction

Given the huge volumes of aid that have flowed across the world for the past 50 years and more, we might well ask whether aid actually works. This is a question that has attracted much attention over the years from a wide variety of theoretical and political perspectives and the debate continues (Cassen 1994; Dollar and Pritchett 1998; Riddell 2007; International Poverty Centre 2007). Evidence can be applied to support different conclusions from different viewpoints. To an extent it depends what questions are asked, how they are constructed and – of course – who is answering them! However, here we will consider some key questions, and seek to be objective in answering them. There are in fact two sets of problems we must consider when answering the overall question ‘does aid work?’ The first set relates to the concept of aid and how it has been operationalised itself – is it problematic conceptually, or even philosophically and should it therefore be ceased? Do any observed problems have more to do with the way it has been applied and therefore is it possible to reform it? A second set of questions refers to the costs and benefits: if we accept that there are both positive and negative aspects to aid, how do we weigh these up? To answer these two sets of problems we separate the effects of aid into economic, political/governance, social impacts. We start by discussing how aid relates to economic growth and performance, and then turn to its effects on governance. Following this, we assess the effects of aid on poverty alleviation. In doing so, we consider the role of civil society and the private sector, both of which have been seen in positive light over the most recent decades in terms of being both targets of and facilitators of aid projects. We conclude with some insights into how aid delivery works with a particular focus on the performance of donors.

Aid and economic growth

In recent years aid has been conceptualised by some donor countries as a way of promoting ‘sustainable economic growth’. It is believed that aid can promote growth by supporting the private sector and when growth occurs development benefits will follow (or ‘trickle-down’ to use the often-utilised and over-simplified terminology), particularly through the generation of wage employment and the positive economic multiplier effects associated with that. The supposed ability of aid to encourage growth has been a characteristic of early neoclassical views within modernisation theory and, though opposed by more fundamental neoliberal views, it has resurfaced in more recent retroliberal aid regimes (see Chapter 4).

The arguments in favour of using aid to promote economic growth rest on a fairly basic premise that developing economies lack key resources, particularly capital and technology. A well-known economic concept, the Harrod-Domar growth model, suggests that the rate of growth of an economy rests on two critical features: the productivity of capital (how efficiently capital is used) and the savings level (savings provide investment that can be used to increase the capital stock). Given that the productivity of capital is hard to change in the shorter term, the key element for economic growth is capital. When savings rates are low, as they are in developing economies, then capital can come from external borrowing, foreign investment or aid. This then sees a basic line of argument that suggests aid can help provide capital which then fuels economic growth, which in turns brings jobs, economic multipliers, and broader development (Todaro and Smith 2015).

The role of aid in promoting growth can come in several forms. At one end of the spectrum, it can be capital investment, such as the building of infrastructure (roads, energy supplies etc.); at the other, it can be in providing seed capital for small-scale savings and investment (such as in micro-credit schemes). In between it might see aid resources used to integrate and support private sector activities in development projects, so that private sector profitability is enhanced by being able to tap development funds. A recent study by Dalgaard and Hansen (2017), noting the renewal of interest in funding large infrastructure projects, found that the average gross rate of return on aid investments ‘is close to 20 percent’ (p.1012).

Other economic models provide a justification for aid in further ways. The Solow-Swan growth model (Solow 1956), seen as a counter to Harrod-Domar, was a more complex model to show the components of growth but it stressed technological progress rather than capital accumulation. For aid, this meant that economic growth in developing countries could be accelerated by promoting the transfer of technology from more progressive economies (and this was certainly embodied in Truman’s post-war speech). Again, this could be in different forms: from encouraging foreign investment (applying modern industrial techniques); to providing incentives for technological innovation; and expanding higher education and vocational training. Many of these could be assisted by aid particularly through training programmes and scholarships to study abroad.

These justifications for aid to promote economic growth, however, were countered by criticisms, which were rather less optimistic and which saw potential economic drawbacks. Firstly, there is the danger that capital introduced from external sources, such as aid, will crowd out scarce local sources. In conditions where the rate of savings is low (most people need all their incomes to survive from day to day and only a relatively few are able to save a surplus), higher interest rates are an incentive for this rate to grow. However, when there is an influx of external capital, interest rates may fall, inflation may rise and good investment opportunities may be restricted. People may shift from saving to more consumption.

Similarly, there can be price distortions with aid which can negatively affect local economic growth. For example, and perhaps counter-intuitively, food aid can lead to future food shortages. When food is scarce, perhaps as a result of, say, drought, then food prices rise. When this happens, local producers who do have a surplus are encouraged to sell and receive a good return, encouraging them to plant more for the next season. But when large volumes of food aid appear and swamp local markets, food prices fall and local producers, whether larger-scale farmers or households producing small surpluses, are less inclined to plant for the future, getting their grain from aid outlets and turning their attention to alternative cash crops. Food production continues to fall, even when harvests improve and food aid can become a more permanent fixture. Similarly, aid projects which require that machinery, fertilisers, computers etc. be purchased direct from donors, by-pass local suppliers and again may depress local prices and disincentivise production. Local businesses face what they see as unfair competition and may suffer as a result.

Aid can also promote dependence and inhibit local development. Aid projects bring in new resources and ideas. If these prove to be useful, there will be a continued demand for these new products or sources of technology. Local sources and ideas are seen as inferior and the new activities that come with projects become closely aligned to external inputs. Furthermore, the viability of activities beyond the project’s notional completion date can be threatened if the external sources of supply and subsidy are cut off. This can involve, for example, dependence on continued aid funding to maintain the overhead costs of a project (administration, maintenance etc.) even if the day-to-day activities are viable.

Finally, the question of inappropriate technology is raised. Aid based on donor-supplied technology can have the effect of distorting an economy towards forms of technology that are out of line with local conditions. Technological development in industrialised Western countries has usually been developed against a backdrop of relative labour scarcity (and higher wages), capital abundance and a skill base in the population aligned with the technology used. By contrast, developing countries, as aid recipients, usually have the opposite conditions: cheap and abundant labour, scarce capital and populations skilled in customary knowledge and low-tech activities but not in the use and maintenance of complex equipment. The result is that aid provides capital equipment that appears to provide immediate benefits, but which cannot be easily maintained into the future. These longer-term costs are not usually accounted for in project planning and impose a burden on the domestic economy.

There is conflicting evidence for the positive or negative effects of aid on economic growth. Some critics (for example Hughes 2003) argue that aid has inhibited or even reversed economic growth and there appears to be no clear correlation between levels of aid and economic growth at least in the short term. However, an International Monetary Fund (IMF) working paper in 2009, looked at such correlations over a longer term and found that a positive relationship did exist, albeit with a long lag-time of up to several decades (Minoiu and Reddy 2009). This suggested that aid could promote economic growth, but only if directed at development-oriented activities and some donors (such as Scandinavian ones) were more effective than others. The authors concluded that effective expenditures to promote growth

may support investments in physical infrastructure, organizational development, and human capabilities, which bear fruit only over long periods … our findings help counter claims that aid is inherently ineffective and aid budgets should be reduced. On the contrary, an increase in aid and a change in its composition in favour of developmental aid are likely to create sizable returns in the long run

Burnside and Dollar (2000) also found a positive relationship between aid and economic growth within a ‘good policy environment’. Furthermore, some recent studies have further supported the view that ‘aid promotes growth in a statistically significant manner’ (Mekasha and Tarp 2019: 14; also Galiani et al. 2017; Morrissey 2001; Arndt et al. 2015).

Nonetheless, there does not appear to be any clear indication as to what specific types of aid promote growth more than others. The debate on the relationship between aid and economic growth is likely to continue. For neoliberals, market failure is largely caused by intervention itself, whereas for neostructuralists intervention must take place in order to correct for those failures. In some ways the whole debate comes down to how you define and measure market failure and negative externalities (such as low savings rates, low levels of technology, and environmental problems) and what you consider can be done to address them. Those on the right-wing believe the market allocates best and intervention creates more problems whilst those more to the left believe that intervention is required to address the problems. A further arm of the left argues that aid creates dependency and foreign domination. In other words, the answer to the question – does aid stimulate the economy? – depends on how you deconstruct the question.

However, some lessons can be drawn from this relationship. Under some circumstances aid can improve economic performance, but it can also inhibit or distort local economies. Aid, in itself, may not be the best mechanism to promote economic growth – many would argue that trade and investment are better. Aid should work with, and not crowd out, local resources, enterprise and knowledge. It can fill some gaps and augment local resources. Arguably, though, it is perhaps best directed at helping to build the long-term capabilities of local economies, through infrastructure, education and training and institutional strengthening. All these require long-term commitments and relationships and there is apparently no ‘quick-fix’ solutions whereby aid can stimulate deep-seated and sustainable economic growth and development. However, it seems that there is robust evidence that aid does promote economic development, mainly through the way it helps build physical infrastructure and human capital. Arndt et al. (2015: 15) conclude:

There is no evidence that aid is detrimental. Aid has contributed to economic growth by stimulating its proximate determinants – e.g., physical capital accumulation and improving human capital, particularly education and health.

Aid and governance

Whereas the debate concerning aid and economic growth is predicated on the assumption that economic growth is the key means to promote the process of development, other approaches to aid focus on less economic parameters of development such as human well-being or institutional capacity. One of the main approaches in this sense grew out of the post-SAP (Structural Adjustment Program) years of the mid- to late 1990s and stressed the importance of ‘good governance’. In large part, this still had many neoliberal features – it believed that previous aid approaches had created and expanded a largely inefficient and bloated public sector that inhibited market-led development – but it recognised that states still had important functions to perform and it blended in concerns for promoting democracy, human rights and public participation. Its theoretical inspiration also came from a branch of economics, this time in the form of the ‘new institutional economics’ of the 1990s, pioneered by Douglass North and others (Martens et al. 2002). This put a focus not so much on market mechanisms but on the way institutions functioned, in particular their rules and social and legal norms. Although new institutional economics was concerned with a broad range of institutions, including the private sector, the basic ideas regarding the way institutions function influenced and suited attempts to rebuild and recraft the state following earlier neoliberal ‘rolling back’ of the state.

Good governance promoted a particular justification for aid to do with the way aid could help recreate and align state systems so that governments could operate efficiently and transparently, both allowing the markets to operate effectively and with security, and promoting citizen involvement and confidence in state systems. It rests on the view that states have a leading role to play in development and this was a key foundation of the ‘neostructural approach’ of the early 2000s. It involved a ‘rolling out’ of the state – introducing new ways of operating and new forms of regulation that created the conditions for the market to function effectively. It is also allied to the role aid can have in promoting democracy, often through the use of aid conditionalities to pressure states to introduce democratic reforms. Gibson et al. (2015) concluded that aid, through technical assistance, has indeed contributed to democratisation in Africa.

The main approach of the institutional strategy is to seek to reform the public sector in two main ways. Firstly, there is capacity building and enhancing capability. Capacity has to do with increasing the number of public servants working in defined areas and capability has to do with building the skills and experience of those performing critical jobs. Education and training are crucial for both, ensuring that there is a good supply of well-educated applicants for all positions and providing specialist skills where needed. The second strand is to do with the policies, processes and procedures of institutions. These were intended as systemic improvements, reforming the way institutions function. These involved aspects such as the separation of funding and providing of services; improved transparency and accountability through better information systems, standardised reporting and public communication; greater public consultation; an end to political interference in operational decision-making; and the use of international standards and systems to manage human and financial resources. Again, this strand rested on education and training, though here with the added strategy of using international consultants to offer advice on how the systems should work. An added attraction of these approaches for donors was that it helped align recipient government systems with those of the donors, so that officials on both sides could understand common principles and systems and donors could more easily track how aid money was being managed and allocated through recipient agencies. Thus, aid for public sector reform aimed at all facets of the state, from law and order, the judiciary, the legislature, the full range of line ministries, and policy making as well as service delivery.

As well as these approaches to public sector reform, the use of aid to support government functions has been justified in terms of the use of higher order modalities (see Chapter 5). Simply put, it is recognised that to achieve significant long-term and large-scale improvements in the welfare of a country’s population, it is necessary to commit to substantial and sustained support for core government functions to do with human welfare, particularly education and health. The significant increases in aid following the turn of the new millennium were largely channelled, following the Paris Declaration, through recipient government systems in the form of SWAps and budget support.

However, there were and continue to be critics who suggest that greater funding for government operations and the use of recipient government agencies, even if reformed, is not an effective use of aid and is open to misuse and distortion (e.g. Moyo 2010). There are several aspects to these cautions and critiques. Firstly, without very close scrutiny, there is the issue of fungibility. Fungibility refers to the ways state funds can be shifted to other uses when aid is used to cover some budget items. Thus, for example, Official Development Assistance (ODA) is not used to fund expansion of the military of a recipient but if it contributes substantially to, say, health and education budgets, then a government may feel that it has some freed up resources (otherwise spent building hospitals and schools) to spend on new equipment for the army or air force.

Secondly is the issue of fiduciary risk, that is the risk that aid money spent and travelling through government systems may not reach its target and achieve its objectives. Much is said about corruption in developing countries (Rimmer 2000; Kramer 2007; Masoud et al. 2015), with accusations that politicians and officials find ways to divert aid funds to their own pockets or are able to influence donors to allocate projects to their own regions or ethnic groups (Briggs 2014). However, most donor agencies do not confront this issue directly, but instead focus on the much broader concept of fiduciary risk. There is a broad issue of fungibility (Howard and Rothenberg 1993) where aid received for some purposes, such as education, can allow governments to spend elsewhere, such as the military, but fiduciary risk is more complex. There are many other ways that aid funds may not reach their intended destination apart from overt corruption. For example, a government that operates under very tight budget constraints might find that it struggles to meet its everyday expenses (such as paying civil servants) when revenues do not come in as expected. If this happens and a large amount of aid funds appears, the Ministry of Finance may well be inclined to divert the aid funds to pay salaries and hope that other revenues improve so that the aid program can be recompensed in time.

Another issue has to do with dependence. With ODA being committed to large-scale programmes of expenditure, such as education, it can be difficult for recipient governments to find ways to expand their share of expenditure and eventually take the place of donors. Donor funding can become a semi-permanent feature of key government functions and the loss of donor funding can have catastrophic impacts.

Donors also struggle with the question of state legitimacy (Buiter 2007). When large amounts of ODA are committed to supporting the functions of the state, there is a strong indication that donors approve of the state and its leadership and recognise its legitimacy. However, as often happens, states are open to opposition and groups within a country may question the state’s right to govern. This happens when the rights of regional minority groups are not seen to be recognised sufficiently and separatist movements arise, there are human rights violations by the state, or when unconstitutional or questionable methods are used to gain power etc. Donors are in an invidious position, for if they continue to channel ODA through the state they are seen to be supporting the government over opposition groups, and if they withdraw aid, they lose the opportunity to fund substantial programmes of change and are seen to be anti-government. These political considerations are crucial and often donors will decide on aid allocations on the basis of whether or not they want to fund a particular regime rather than necessarily whether the state has the ability to manage that aid effectively.

Aid for government functions also has some potentially negative aspects for recipient states themselves. Loss of independence inevitability follows agreements that involve large sums being tracked through state coffers. Donors understandably want to see that aid is well spent and want the recipient government to be accountable, but this requires a high degree of conditionalities over how internal systems work, what reporting will take place and the funding priorities of the state. There is a clear trade-off for recipients: accepting large aid donations means compromising the ability to manage the state completely independently. This leads to what we have called elsewhere the ‘inverse sovereignty effect’ and is particularly salient in smaller countries (Murray and Overton 2011b).

There are also more mundane problems for recipients. Despite the rhetoric of the Paris Declaration, donors have often proved slow to move towards predictable multi-year funding commitments. In practice, many still renegotiated funding on a year-to-year basis and the vagaries of donor budgets often resulted in volatile and unpredictable funding streams recipients. The example of the small Caribbean island state of Granada (Box 6.2) provides an illustration of how this country, dependent on ODA for a significant share of its development budget, has had to face large swings in aid flows from year to year, posing major difficulties for its financial management and forward planning.

Recipients have also had to face what might be termed the ‘burden of consultation’ and lack of co-operation amongst donors. Following on from their ‘good governance’ concerns, donors have frequently, and rightly, attempted to ensure that there is wide public consultation regarding aid programmes and projects. This involves frequent public meetings, continual engagement with relevant government agencies, regular reporting and thorough monitoring and evaluation. Furthermore, each donor often has their own consultation requirements and procedures to follow in order to report back to their own agencies. Add in the large number of non-governmental organisation (NGO) agencies, the range of issues covered (from climate change to community policing) and the often-stretched recipient government and NGO institutions, and the result is often very high compliance costs for recipients to meet and report to a range of donors. For small island states such as Tuvalu, with a very small bureaucracy, the need to comply with global standards for consultation and reporting, the burden of consultation is heavy indeed (Wrighton and Overton 2012). Finally, for recipients, the requirement to adopt donor systems and processes may sometimes seem not only burdensome but inappropriate. Donors adopt their own ways of operating usually developed from their own social and cultural context. But these may not be suited to societies where, for example, there are strict social and political hierarchies and open public meetings may be dominated by certain elites. And for small island states or states with limited institutional capacity, large and complex international accounting and reporting systems may simply be too large and unwieldy (Overton et al. 2019).

These concerns have led donors and recipients to develop particular practices to mitigate some of these issues. The DAC-sponsored high-level forums on aid effectiveness (from Rome in 2003 to Busan in 2011 – see Chapter 3) aimed to develop guidelines and share good practice. Thus, the principles of aid effectiveness involved aspects such as donor harmonisation, use of recipient systems and so forth and there was much emphasis on improving financial management systems.

More recently, new donor approaches have been developed to tackle the ‘development-security nexus’ in situations where conflict and weak local governance have required more direct involvement, sometimes alongside military intervention (see Box 6.3). Here we see peacekeeping leading to the securitisation of aid, so that aid appears alongside military operations to restore order, then help build more secure institutions and government capacity.

It is hard to quantify and analyse how effective aid has been in improving governance and government services in recipient states because improvements, if they occur, are highly qualitative: more transparency, greater confidence in government, more able officials, etc. However, it is clear that public sector change in many countries, following a decade or so of the neostructural aid regime, has been profound and largely beneficial. Monitoring of the Paris Declaration goals for a number of years showed appreciable increases in the use of local systems, moves towards untied aid policies. However, the targets set were frequently not fully achieved and, after 2008, the shift to a retroliberal aid regime seemed to take donor attention away from these state-centred performance measures. In other ways, though, the good governance and neostructural approaches did bring about important changes. Public sector reforms occurred across the developing world and many new and improved ways of operating were introduced whilst government programmes in health and education were bolstered considerably.

The relationship between aid effectiveness and governance is complicated by the fact that poor governance is strongly correlated with poverty, so that aid is more likely to go to states where good governance structures are in place and are thus more likely to be effective, whereas it is difficult to get good results from aid when poor governance is in place (Denizer et al. 2013; Levy 2014). Aid, however, along with other diplomatic measures, has helped bring about ‘regime change’ in places such as Kenya and Fiji where regimes with questionable democratic credentials were ‘encouraged’ to move to democratic elections and restore human rights. There seems to be evidence that aid has had a positive effect on promoting democracy, particularly in the post-Cold War era (Dunning 2004; Kersting and Kilby 2014). On the other hand, there are also cases where the withdrawal or non-existence of aid has not had a similar effect (North Korea and Zimbabwe, for example). As such it is hard to truly analyse the impacts on governance.

Thus, we might come to a tentative conclusion that aid can work to improve governance and government services, with long-term benefits for development under certain conditions (Dijkstra 2018). Carefully designed ODA programmes that conform to aid effectiveness principles can work with efficient state agencies to provide improved services for citizens and these, in turn, can provide the means for long-term improvements in well-being and widen the range of development options for individuals and states alike. Yet, when implemented less carefully – and perhaps when guided by motives other than aid effectiveness – support for recipient governments can bring about negative consequences in the form of supporting inefficient bureaucracies or undemocratic governments. And from the recipient side, changes in development management can lead to a situation where local control is compromised and governance is more a matter of pleasing and aligning with donor interests and ways of operating than forging strong and independent local development systems and strategies (Overton et al. 2019).

Aid and poverty

The rhetoric of poverty alleviation lies behind much of the public justification for aid programmes. Relieving human suffering provides the apparent raison d’être for many of the aid-funded projects and programmes world-wide and campaigns to increase aid, such as ‘Live Aid’ or ‘Make Poverty History’ appeal to this goal. Most aid and development strategies have poverty alleviation as an explicit objective, whether straightforward humanitarian relief, focused provision of basic services for the poor, or even economic growth models which promise a trickle-down effect for all (Collier and Dollar 2002). However, despite a basic view that the needs of the poor can be met by gifts from the wealthy, there is still much debate whether aid is very effective at alleviating, much less eliminating, poverty.

On the positive side, aid to alleviate poverty is largely based on a ‘deficit framing’ of poverty: it focuses on what poor people do not have and what they need to become better off. A lack of resources (whether food, clean water, good sanitation, basic education, health services, technical skills, equipment or financial capital) is seen as the basic obstacle to improvement in livelihoods and well-being for the poor and these resources can be provided from aid donors. This approach is most explicit following natural disasters or conflict when people’s very survival is threatened by lack of food, water or shelter. Aid agencies, domestic and international and including governments, have proved able in most cases to identify these needs and respond accordingly (even if not as rapidly or completely as some would want). Aid has also been seen as successful in tackling major health problems, such as the incidence of malaria or smallpox (Levine 2007).

Perhaps the most prominent poverty-focused ‘project’ to tackle poverty was the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) of 2000–2015. These, and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which followed for 2016–30,1 identified some key dimensions of poverty though they tended to highlight the expressions of poverty rather than their underlying historical and contemporary structural causes. Thus, poverty alleviation was seen to be about raising incomes, improving maternal and child health, increasing literacy, ensuring women and girls achieve great equity of access to education and health etc., tackling major diseases, and improving sanitation, water supplies and housing. The MDGs and SDGs have therefore provided a substantial and explicit poverty agenda for aid. Aid should be directed to these key aspects of human well-being so that millions of people can move out of poverty.

Not everyone agrees with this approach though and critics argue that aid is not effective at tackling poverty at all. Neoliberal thinkers continue to argue that a free market is the best way of achieving economic growth and employment generation. They use metaphors such as ‘trickle down’ or ‘a rising tide floats all boats’ to suggest that market-led growth is more effective at dealing with poverty aid- and government-led interventions. Intervention creates distortions and disequilibria that lead to less than optimal allocations of resources (see the discussion on the economic impacts of aid above). Others, such as Easterly (2006), suggest that aid, despite the rhetoric of poverty alleviation, does not reach the poorest, but is instead captured by elites or squandered by inept donors or recipient governments. In some ways, these latter critiques hark back, albeit from a different ideological standpoint, to Robert Chambers’ early (1983) criticisms of development practices ignoring the poor. If aid does not reach the poor, then it can contribute to rising, not falling, levels of inequality.

These debates are not easily resolved either way by the available evidence. Firstly, though, we can look at the record of the MDGs, recognising the very large aid commitments that were behind efforts to meet the goals. Although there were disappointments with the MDGs with most developing countries being unable to meet all the goals, there were some significant improvements. Access to health services improved markedly in many countries, as did participation in primary education. There is strong evidence that aid has helped lower rates of infant mortality, for example (Kotsadam et al. 2018). Gender inequalities were given attention as perhaps never before and, overall, the lives of many millions of poor people improved over the span of the MDGs. However, it is not clear how much credit aid can claim for these achievements. In particular the massive improvements on a global scale in incomes for many – the number of people living in extreme poverty globally fell from 1.9 billion in 1990 to 836 million in 2015 (United Nations 2015b: 4) – was largely due to the rapid growth of the Chinese economy, which had little or nothing to do with aid (Sachs 2012). Measuring the impact of aid is a counterfactual problem – we simply do not know what would have happened without it. It is also a multi-faceted and complex equation where it is difficult to separate cause and correlation.

So we are left with similar conclusions to those of Robert Cassen’s studies of 30 years ago (Cassen 1994) – that aid can improve the lives of the poor, but it can also miss them out and, in the worst cases, make their position worse off. Many poor people do benefit from aid through improved access to schools and health services and some experience higher consumption levels and, through infrastructural improvements, better access to markets and information. Rural electrification can make major differences to the lives of poor households, even if it means that children can do homework by electric light at night, and better water reticulation similarly helps by ending the arduous task of fetching water from afar, usually undertaken by women and children. And it is beyond doubt that the lives of thousands have been saved by effective humanitarian interventions and assistance. These are real and tangible improvements in human livelihoods. Yet there is a nagging doubt that, despite the rhetoric, much aid does not reach the poor (for example, Briggs 2018) and has not been focused on poverty alleviation. Riddell (2007) suggested in 2007 that 40 per cent of the world’s aid was not directed to the MDGs and this is almost certainly the case, if not worse, in the retroliberal period.

To draw lessons from these debates, we might suggest that aid can and does help tackle poverty. Humanitarian relief will always be needed in desperate times of need but when aid is directed to addressing the underlying causes of poverty, not just symptom relief, then long-term and sustainable improvements can be made. Better education and health services remain critical priorities for many countries and a focus on gender equity seems to bring substantial gains to welfare (Nussbaum 2000; Schultz 2002; Unterhalter 2012). Yet these are very long-term processes of change that require sustained aid support over perhaps generations, and they defy quick results. Attitudinal changes and societal transformations lie at the heart of deep-seated strategies to eliminate poverty, rather than a simple transfer of resources and filling of short-term need. Furthermore, as well as moving from short-term and quantitative approaches to poverty alleviation, aid programmes should also move from a narrow deficit-based framing of the issue to consider a more asset-based approach, building on, working with and respecting local assets, aspirations and knowledge.

Aid and non-state sectors

Aid, particularly ODA, is frequently seen as working through a relationship between donor agencies (bilateral or multilateral) and recipient governments. However, non-state actors are often involved in various ways on both the donor and recipient sides (Wallace et al. 2007). The two key sectors here are civil society and the private sector.

The involvement of non-state agencies is important for a number of reasons. Firstly, they operate as substitutes for the state when recipient government agencies are regarded as inefficient, risky or not legitimate. Donor agencies can then by-pass the recipient government and not have to be seen to support it overtly. Thus, we see donor agencies turn to civil society agencies as partners in delivery of aid projects when governments are accused of being undemocratic or abusing human rights or excessively corrupt. Secondly, civil society and the private sector may be more flexible and cost-effective parties through which to distribute aid. Development NGOs often run with small overheads or rely on voluntary labour and private companies have other operations on which to fall back on. They can both pick up contracts for aid projects and thus have fixed and manageable involvement, preferable in some ways to maintaining a large permanent establishment to disburse aid within a government donor agency. With many NGOs and companies vying for contracts, donor agencies may find they can get good results for less money by using these agencies. Development NGOs and private firms thus become sub-contractors for aid delivery, tied to the donor agencies through legal contracts (Choudry and Kapoor 2013). Thirdly, non-state actors (especially NGOs) may be regarded as having closer ties to communities and poorer groups in society than governments. Many NGOs owe their origins to community organisations and draw their membership from communities. They are thus well placed to understand the needs of poorer communities and develop appropriate strategies for implementing aid projects. Civil society organisations can therefore be more responsive and better informed about poverty on the ground in remote rural regions than government agencies in a far -off capital city. In addition, donor development NGOs become part of this picture, for their relationships with recipient NGOs (some may be branches of the same international NGO) provides an effective set of networks through which a large number of hopefully well-informed and appropriate community projects can be supported efficiently by donor governments. These networks also often involve long-term durable relationships between individuals and agencies (also involving the development of deep level knowledge and understanding of conditions within recipient communities) that can be drawn upon to provide information or broker new projects when needed. These forms of social capital are extremely valuable in the aid world but are not always well recognised.

On the donor side too, there are good reasons to involve civil society. Development NGOs provide a key role in promoting development issues in the donor community. They help raise public awareness about poverty and development issues and, whilst this is primarily in order to raise funds to support their own operations, it can help donor governments who need to justify their aid budgets. Of course, this can also be a two-edged sword, for development NGOs will also seek to lobby governments to increase budgets more than they wish or change their aid policies. In many ways though, partnerships form between donor governments and NGOs and this was the case during the neostructural era of the early 2000s when both sides were committed to the MDGs: donor governments kept the NGOs on-side by drawing them into their aid programmes and offering contracts and funding. It had also been the case in the earlier neoliberal phase when donor governments sought to by-pass state agencies and use NGO contracting to fill the gap in, for example, limited welfare projects.

Private companies in donor countries have had an increasing role in aid in recent years. Part of the reason for this is shared with civil society: they may be flexible and cost effective in aid delivery through fixed projects and they can be drawn into supporting wider government aid strategies if they receive some of the funding. However, the reasons for involving the domestic private sector in aid is also so that donor governments can be seen to be channelling some of the benefits of large aid budgets back to the local economy. In the retroliberal era this has become much more common. There are aspects, such as the increased use of tertiary scholarships, which involve large portions of the aid budgets being spent in supporting donor tertiary institutions through fees and the domestic businesses through accommodation and living costs going into the donor economy. There is also the support of consulting firms which manage aid projects and provide expert advice to recipient countries but whose fees are received and spent largely in the donor country. Increasingly now, the involvement of private sector donor firms in aid is even more explicit with aid projects being designed to complement and help promote the offshore business operations of these firms. This is a far cry for non-state actors from using NGOs as cost-effective agencies to help deliver services.

Despite these advantages of using non-state agencies, we should also raise some questions and doubts about their use. These questions are rather different for civil society as opposed to the private sector. Civil society organisations are often regarded as efficient, well-informed, cost-effective and a good alternative to large, inefficient and corrupt state institutions. However, in practice, some development NGOs in recipient countries are not. Just because they are local does not mean they are any closer to understanding community conditions than, say, a local government official. They are often run by urban, relatively well-educated people. Many, yes, are based on real concerns for justice and poverty and are run by passionate, selfless and able staff but some are little more than middle class business operations, seeking to capture some of the revenue flows coming from donor agencies. Similar things might be said about development NGOs in donor countries. They are based on real concerns for human well-being and inequality and to address human suffering but, in order to function effectively, they have to run as businesses. The have to raise revenue to employ staff, pay rent and continue to support their offshore operations. In doing so they may appeal to basic sentiments of need and helplessness and use methods such as child sponsorship which may be effective at raising money from a sympathetic public, but which may well misrepresent the real conditions of people and wrongly convey simple pictures of complex development conditions and processes. Nor is there any guarantee that civil society organisations will be automatically any less inefficient, corrupt or ill-informed than their government counterparts. Indeed, some have to run with relatively high overheads and, due to small-scale and limited budgets, simply do not have the resources to put in place complex financial management and auditing systems (thus they find it hard to comply with strict donor conditions on such things). Finally, NGOs may have a difficult relationship with the state in recipient countries. Although involved in development work, many NGOs also are involved in advocacy and this can bring them into disagreement with government particularly when they suggest that government policies are part of the cause of developmental problems at the scale of the community and above. As a result, NGOs may be limited in their operations, confined to roles that are politically acceptable (so they can get funding and be allowed to operate), but perhaps staying away from important but contentious development debates.

For the private sector, the criticisms are rather different, but also considerable. Private businesses have to turn a profit to survive and this is both an advantage (they have to closely manage costs and revenue and run efficient systems) and a disadvantage (they will steer away from worthy development projects if they are not seen to be profitable). Businesses can operate well within fixed project cycles and with pre-defined and manageable activities and outputs but they are less likely to invest in long-term relationships unless there is a promise of financial return. Longer time horizons pose difficulties as does working in complex and unstable social and political environments (NGOs can be much more adept in these circumstances). Finally, and fundamentally, the private sector is in business to run business: being involved in poverty alleviation schemes and the like is a way of making a profit, not the primary goal. This said, there are many examples of businesses that run as social enterprises – they have social goals as their prime aim and, whilst still needing to earn a profit to continue in business, pure profit maximisation is not their fundamental objective (Kumar 2019). Much more than civil society, private enterprises are unlikely to become involved in political debates regarding the underlying or even short-term causes and impacts of poverty and underdevelopment. Economic activity rather than social and political transformation is their obvious focus.

To summarise, the involvement of both civil society and private sector companies has been common in different ways in the aid world for many years. They offer particular advantages and seem to be successful in contributing in ways that mainstream development agencies may find helpful at various times. They help make aid work. However, neither offers a clear alternative to state agencies and both have disadvantages and limitations. What is clear is that the NGOs and the private sector will continue to be important features of the aidscape, variously working separate from, but mostly alongside and with, both donor and recipient state agencies. The relative role is likely to be a political question and ebb and flow as aid regimes continue to evolve.

Aid and public accountability

Finally, in considering whether aid works, we now turn to consider whether aid works in terms of meeting public expectations regarding its objectives and openness. This aspect is not so much focused on the effectiveness of aid with regard to intended beneficiaries or the extent to which it aligns with principles of good practice (Knack et al. 2011). Rather, it has to do with the way aid agencies operate and report back to donor taxpayers and voters. In this way it is important to recognise that whilst donors frequently impose conditions on recipients to be transparent and efficient in the way they receive and manage aid receipts, the same conditions are not always imposed on doors themselves. Here we examine two examples of the way aid agencies have received recent scrutiny from independent organisations: the Aid Transparency Index and the Principled Aid Index.

The Aid Transparency Index is produced by the ‘Publish What You Fund’ campaign for aid transparency. This was launched in 2008 and receives funding from UK aid and the European Union. The campaign calls for aid donors to publish fully, openly, proactively and comprehensively all information on aid. It links to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI), which has established standards, rules and formats regarding aid transparency. IATI maintains a register and tracks over 1,000 organisations.

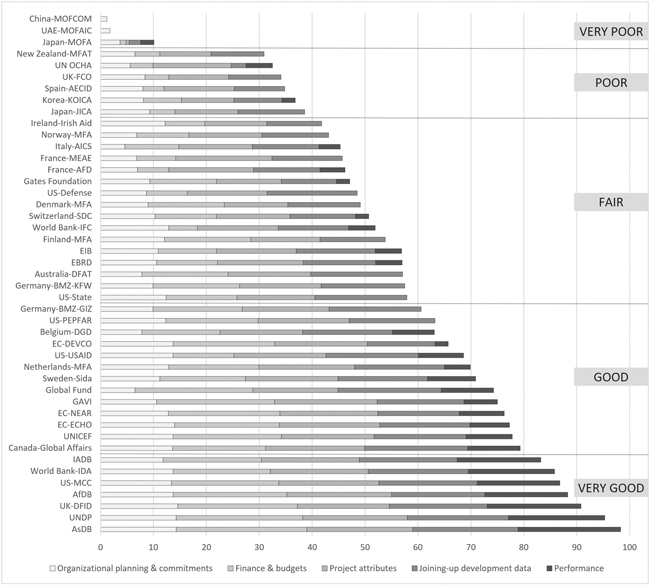

The Aid Transparency Index is compiled annually and collects data on a variety of indices relating to budgets and finance, project attributes, ‘joining-up’ development data, performance, and organisational planning and commitments. It examines 45 major aid institutions including donor aid agencies (e.g. Department for International Development (DFID), United States Agency for International Development (USAID)) and multilateral organisations (United Nations Development Program (UNDP), World Bank). Each is ranked according to the results and categorised from ‘very good’ to ‘very poor’. The 2018 results are depicted in Figure 6.3.

Source: redrawn from https://www.publishwhatyoufund.org/the-index/2018/

These results show wide variation in practice across the agencies. Some rank highly with close to full transparency. Notably this group includes the major financial agencies (Asian Development Bank, African Development Bank, World Bank International Development Association (IDA)). At the other end of the spectrum in the ‘very poor’ category are the foreign affairs agencies of Japan, UAE and China. Also of note is how different agencies from the same country score rather differently: UK’s DFID ranks third from top but its Foreign and Commonwealth Office is sixth from bottom. Overall, the Index notes some improvements with more agencies publishing data on a regular quarterly or monthly basis using the IATI standard. However, there are still major concerns:

- ‘More than a quarter of organisations do not provide descriptions of their projects at all or the descriptions provided cannot be understood by non-experts. Nor do all organisations regularly update datasets with accurate dates or provide the most up-to-date documents’ (p.8).

- ‘Some major international donors are not pulling their weight … This includes organisations at the bottom of the Index: Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan-MOFA), the Chinese Ministry of Commerce (China-MOFCOM), and the United Arab Emirates’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation (UAE-MOFAIC). These have not joined IATI but also make very little information publicly available elsewhere, despite being among the largest international donors’ (p.9).

- At a time when ambitious global development goals, such as the SDGs, have been agreed and donors are increasingly under pressure to demonstrate that budgets are being spent effectively and have impact, the 2018 Index … reveals serious data shortfalls (p.25).

Overall, we might add that not only do most donor agencies need to improve their performance with regard to the transparency of their aid policies, expenditures and evaluations, they also many need to practice better themselves what they require of their recipient partners.

The Principled Aid Index is produced by Overseas Development Institute (ODI) in the UK (Gulrajani and Calleja 2019). It focuses on the 29 DAC donors and uses data on their aid spending to analyse the extent to which their aid can be considered ‘principled’. ‘Unprincipled’ aid is regarded as ‘self-regarding, short-termist and unilateralist. Donors concentrate on securing narrower commercial or geopolitical interests from their aid allocations while sidelining areas of real development need or undervaluing global cooperation’ (Gulrajani and Calleja 2019: 2). The Index is formulated on the basis of three components (needs, global co-operation and public spiritedness), each with four quantitative indicators (Table 6.1).

Principle |

Definition |

Indicators |

Needs |

Aid is allocated to countries to address critical development needs and vulnerabilities |

A. Targeting poverty: Share of bilateral ODA/gross national income (GNI) targeted to least developed countries (LDCs) |

|

|

B. Supporting displaced populations: Share of ODA to developing countries that cumulatively host 70 per cent of cross-border forcibly displaced populations |

|

|

C. Assisting conflict-affected states: Share of humanitarian ODA to countries with active violent conflicts |

|

|

D. Targeting gender inequality: Share of bilateral ODA to countries with the highest levels of gender inequality |

Global co-operation |

Aid is allocated to channels and activities that facilitate and support global co-operation |

A. Enhancing global trade prospects: Share of bilateral ODA to reduce trade-related constraints and build the capacity and infrastructure required to benefit from opening to trade |

|

|

B. Providing core support for multilateral institutions: Share of ODA as core multilateral funding |

|

|

C. Tackling the effects of climate change: Share of total ODA (bilateral and imputed multilateral) for climate mitigation and adaptation |

|

|

D. Constraining infectious diseases: Share of total ODA allocated to slow the spread of infectious diseases |

Public spiritedness |

Aid is allocated to maximise every opportunity to achieve development impact rather than a short-sighted domestic return |

A. Minimising tied aid: Average share of formally and informally tied aid |

|

|

B. Reducing alignment between aid spending and United Nations (UN) voting: Correlation between UN voting agreement across donors and recipients, and donor ODA disbursements to recipients |

|

|

C. De-linking aid spending from arms exports: Correlation between donor arms exports to recipients, and ODA disbursements to recipients |

|

|

D. Localising aid: Share of bilateral ODA spent as country programmable aid (CPA), humanitarian and food aid |

Source: Gulrajani and Calleja (2019: 3)

Each donor is scored (out of ten for each of the three principles) and ranked. The results for 2017 are shown in Figure 6.4. As with the Aid Transparency Index, we see considerable variation across the range of donors. Not only does the total score vary, but also donors may be unevenly strong or weak on different principles. Thus, Slovenia, for example scores poorly on global co-operation, but highly on public spiritedness. France is poor on responding to needs, but the second best at committing to global co-operation. Luxembourg, as the top-ranked donor, is strong in all three principles.

In tracking scores over different years, the authors of the index found that donors are becoming more principled in total but that there is ‘a worrying deterioration in donor commitment to public spiritedness’ and ‘many donors are adopting a more short-sighted approach to aid, targeting it to help domestic constituencies and firms and supporting short-term foreign policy objectives, rather than taking a longer-term, principled approach’ (Gulrajani and Calleja 2019: 1 and 7). This finding is in line with our earlier analysis of the retroliberal aid regime in the past decade, putting donor self-interest ahead of poverty-related needs. Also worthy of note is that fact that, when the index is set alongside a measure of donor generosity (the ODI/GNI ratio), there is a positive correlation evident: the more generous donors are more likely to be more principled.

Source: redrawn from https://www.odi.org/opinion/10502-principled-aid-index

Along with these two surveys across the range of donors, there are some instances of agencies scrutinising particular country programmes. One interesting example is the UK’s Independent Commission on Aid Impact (ICAI). This agency was established in 2011 as a watchdog for British ODA. It operates independently of government and works ‘to ensure UK aid is spent effectively for those who need it most, and delivers value for UK taxpayers’ (https://icai.independent.gov.uk/about-us/). The agency produces reports on various aspects of the aid programme, whether overseen by DFID or other government agencies. For example, it has been critical of the business in development approach of DFID (ICAI 2015), and the investment arm of UK aid (CDC) (ICAI 2019a). An overall review of its 32 investigations between 2015 and 2019 (ICAI 2019b) recorded a variety of ‘scores’ (on a range from green to red, from effective to not effective). Of the 24 activities which were scored, only one (efforts to eliminate violence against women and girls) received a clear ‘green’ rating, whilst eight received a worrying ‘amber/red’ score. Overall, it raised concerns about the direction of the country’s aid programme and cautioned that the UK’s ‘pivot back towards upper-middle-income countries does not lead to neglect of the key SDG objective of eliminating extreme poverty and inequality’ (ICAI 2019b: 25).

These forms of scrutiny on donors are important and suggest that when we consider the question of whether aid works, we need to examine closely the performance of donors in formulating, targeting and reporting on aid, as well as analysing the impacts of aid on recipient economies, societies and systems of governance. Donors should be just as accountable for aid as recipients.

Conclusion

We started this chapter by asking whether aid works. Sadly, there is no clear answer, in part because it depends on how the question is posed. There is evidence and there are arguments to suggest that aid can indeed bring benefits in terms of economic activity, improved welfare, relief from hardship and even reduced levels of poverty. Aid has often worked, but on the other hand, it frequently has not. Aid can bring harmful effects: crowding out local resources and initiatives, producing dependence, being appropriated by the wealthy, and widening inequality.

We suggest that, although there are no clear and obvious answers, aid seems to be more effective when it is directed at working with and building local assets and capabilities, at providing the important elements of welfare services (health and education) and basic needs (clean water, sanitation, shelter) that allow people to survive, be healthy and then take steps to improve themselves, their families, and their communities. This is not to suggest that the state should effectively practice a totally hands-off self-help philosophy. The state must intervene to facilitate and support development through the correction of market failures and negative social externalities, which we argue are large and damaging in the case of developing economies. Aid plays a very important role in this regard. But it cannot do it alone, a strong and effective civil society is required together with an enlightened private sector. On the other hand, when aid becomes too involved in private sector operations, whether subsidising some elements and not others or taking the place of local enterprises, there seem to be questionable results and likely distortions. Aid can work well when in partnership with private companies and local government agencies and it can help support and build public capacity to undertake important development programmes, yet this is no automatic path to success for there are many pitfalls. For aid to be effective, we also contend that it has to be transparent and principled on the donor side.

However, to return to our question, ‘does aid work?’, perhaps we are asking the wrong question. We are judging aid by criteria that may seem to be intuitively valid – does aid promote economic growth, does it improve governance, does it alleviate poverty etc. – but which are not at the root of why aid is given in the first place. The bulk of global ODA is given by powerful Western countries who support aid budgets as part of their overall foreign policy strategies. Aid programmes are supported in a rhetorical sense by appeals to poverty alleviation, democracy, human rights, or humanitarian relief. Public support for aid rests largely on these explicit goals. However, aid budgets are only sustained because they help achieve larger foreign policy objectives: political stability, strategic alignment, economic integration and trade, and, overall, national self-interest. And although these things are almost impossible to quantify and analyse in a cost-benefit manner, it is apparent that aid does indeed work, for if it did not help achieve these wider goals, aid budgets would have been cut long ago! Nonetheless, we (as with the authors of the Principled Aid Index) argue that donor self-interest is in fact best served in the long-term by contributing to a ‘safer, more sustainable and more prosperous world’ (Gulrajani and Calleja 2019: 2; also Collier 2016), rather than the short-term pursuit of donor economic and political goals. This intangible but infinitely valuable prospect will yield long-lasting progress and prosperity for donors and recipients alike.

Summary

There is a range of viewpoints concerning whether aid works or not. Opinions are often rhetorical in that they do not refer to empirical evidence. Furthermore, the answer to the question ‘does aid work?’ is dependent on how the question is constructed.

A central objective of aid has been to promote economic growth. There are various models rooted in modernisation theory that argue the need for capital and technology. Critics from a neoliberal point of view have suggested this crowds-out, distorts prices and leads to the application of inappropriate technology.

Neoliberals consider that intervention in the economy creates negative externalities whilst neostructuralists argue that negative externalities can only be solved through intervention.

The most serious empirical studies are clear that long-term aid can work positively for the economy, under certain circumstances. There is no quick fix and broad programmes that incorporate infrastructure, improve human capabilities and technological progress work best.

Beginning in the neoliberal aid regime there was a focus on good governance as a target for aid. Emphasis on ‘rolling back’ the state turned to facilitating the state in the neostructural period.

The Paris Declaration of 2005 and the resultant focus on ownership and effectiveness greatly enhanced the use of aid towards capacity-building programmes with the long-term objective of facilitating governments to bring about progressive development.

The evidence on the relationship between aid and good governance is mixed, Sometimes the concept of good governance has been used as a smokescreen to further donor geopolitical aims but sometimes it has precipitated positive structural changes in governance that have yielded positive outcomes for populations.

Aid is often justified as a means of reducing poverty. However, this has not always been its true objective.

Through the MDGs and the subsequent SDGs there has been an explicit concern with poverty reduction and latterly its elimination. However, reductions in poverty cannot be ascribed solely to the MDGs.

Critics of the role of aid in reducing poverty often use anecdotal evidence to support their views. A more rounded empirical approach suggests that long-term policies that target the poor have a positive impact.

Non-state actors have become increasingly involved in aid flows. Civil society and the private sector are seen as more flexible and ‘less political’. However, there are drawbacks in the case of both.

Donors need to be as accountable for aid allocations as recipients, as they clearly prosper from it and it helps justify it politically. There is a wide range of transparency between donors, although generally there is room for improvement.

Overall, some aid has worked and some has not. Aid that aims for long-term, broad-based, inclusive development has been the most successful and will continue to yield results that are not instantly measurable but nevertheless enormously valuable.

Discussion questions

What are the economic arguments for and against aid?

‘Aid undermines the ability of recipient governments to manage their own affairs’. Discuss this statement in the light of arguments concerning aid and good governance.

Is there a direct correlation between aid and poverty reduction? If not, why not?

According to empirical studies what are the best approaches to aid to reduce poverty?

What explains the rise of non-state actors in the aid sector and how effective have these groups been?

When we assess if aid works, what measures should we use as evidence?

Websites

The Aid Transparency Index: https://iatistandard.org/en/

The Principled Aid Index: https://www.odi.org/opinion/10502-principled-aid-index

Videos

Note

1 The SDGs continue a concern for poverty alleviation – in fact this is extended to setting the ambitious objective of ‘poverty elimination’ – but are not solely about poverty as the MDGs professed to be. The SDGs include broader concerns for environmental sustainability, justice and inequality and widen the concern to all countries.

Further reading

Addison, T., Morrissey, O. and Tarp, F. (2017) ‘The macroeconomics of aid: Overview’, The Journal of Development Studies 53(7), 987–997.

Barcelos, P. and De Angelis, G. (eds.) (2016) International Development and Human Aid: Principles, Norms and Institutions for the Global Sphere. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh.

Easterly, W. (2003) ‘Can foreign aid buy growth?’, Journal of Economic Perspectives 17(3), 23–48.

Gibson, C.C., Andersson, K., Ostrom, E. and Shivakumar, S. (2005) The Samaritan’s Dilemma: The Political Economy of Development Aid. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Jones, S. and Tarp, F. (2016) ‘Does foreign aid harm political institutions?’, Journal of Development Economics 118, 266–281.

Oxfam (2010) 21st Century Aid: Recognising Success and Tackling Failure. Oxfam Briefing Paper 137.

Riddell, R.C. (2007) Does Foreign Aid Really Work? Oxford University Press, New York.