Chapter 3

“How Do I Copyright My Name?”: Answering Legal Reference Questions

A favorite story among librarians of all stripes is the story of the Jesus photo. Here is the version from Bizarre Questions and What Library School Never Taught You (www.bizarrequestions.blogspot.com), where it showed up on April 28, 2008:

It is a Sunday afternoon in the public library and I am on the reference desk. A nicely dressed man, probably in his mid 40s, comes up to the desk. “Can I help you?” I ask. “Yes,” he said. “I’d like to see the photo of Jesus.”

I scrutinize his face. I look around for hidden camcorders or some sign that this is a joke. But no. The man is 100 percent serious. So I take a deep breath and say, “Do you mean some of the religious paintings of Jesus?”

“No,” he says, looking at me as if I am too stupid to understand the question. “The photo of Jesus.”

With a perfectly straight face and sincere tone, I say, “Well, that’s gonna be hard to come by because Jesus lived 2,000 years ago and the camera was only invented in the 1800s. If I had a photo of Jesus, I’d be very rich because I would’ve sold it long ago.”

“What do you mean?” he asked angrily. “I’ve seen pictures of Jesus all over the place! I am just asking you to show me the real one!”

Patiently, I say, “What you have seen are artistic renditions of Jesus. See, if the artist is white, then Jesus is white with blue eyes. If the artist is Hispanic, then Jesus is Hispanic-looking. If the artist is black, then Jesus is black. See how that works?”

I try to allow him to save face. “Would you like to see a book that has a lot of paintings of Jesus in it instead?” I ask him.

The patron was having none of it. “Look, if you don’t have a photo of Jesus you should just say so! I am going to the Christian bookstore! I bet they’ll have a picture of Jesus!” And with that statement, he stormed out of the library.

Librarians laugh at such patrons-say-the-funniest-things stories (another good source is www.librarything.com/topic/17962). We laugh guilt-free, knowing the stakes are relatively low when someone is looking for a picture of Jesus. Other patrons, however, are not so risible. They come in needing medical information or help finding a job. Patrons with legal questions have this same sense of urgency. Every day, people need to know how to divorce a spouse, get custody of children, evict a nonpaying tenant (or avoid eviction by a heartless landlord), start a small business, expunge a criminal record, get a significant other out of jail, settle tax liens, restart Social Security or unemployment benefits, or defend against a lawsuit. These are big problems, crises in some cases, especially among those who cannot afford a lawyer. That so many people are self-represented is a crisis in itself, one that has been transforming the legal system for years (see Chapter 9 for more on this).

The stakes are also high for attorneys, who are hired by their clients to stave off these types of threats. Attorneys who fail might face a malpractice lawsuit. Clients sue for malpractice all the time—but the suit is warranted, and the former client will likely win, if the attorney overlooked a key statute or relied on an overturned case. Judges have even sanctioned attorneys for failing to conduct diligent, thorough legal research,1 sometimes adding the sanction on top of a malpractice award.

The rise of the self-represented and the pressures of legal research make access to information the crux of legal practice. What tools and techniques should librarians use to facilitate this access?

Pro Se Patrons

The technical term for representing oneself in a legal matter is pro se representation. Pro se is a Latin phrase meaning “for oneself” or “on one’s behalf.” A person may be pro se in a civil case as plaintiff or defendant or in a criminal case as a defendant. The right to act pro se dates back to the beginning of the United States with the Judiciary Act of 1789, which provided that “in all the courts of the United States, the parties may plead and manage their own causes personally or by the assistance of counsel.”2 Later, the Sixth Amendment to the Constitution set forth rights related to criminal prosecution—rights that include pro se representation, as the U.S. Supreme Court observed in Faretta v. California, 422 U.S. 806 (1975).

In the last 10 years, court systems everywhere have seen an increase in their numbers of pro se litigants. According to a 2009 survey by the Self-Represented Litigation Network, 60 percent of judges nationwide reported such an increase. In Oregon, 65 percent of family law cases involve at least one pro se, and in Maryland, the number is 70 percent. Out of nearly 250,000 child support cases in Texas in 2011, 95 percent involved at least one pro se litigant.3 For more information on pro se litigants, check out the following websites:

- SelfHelpSupport.org (www.selfhelpsupport.org)

- National Center for State Courts (www.ncsc.org)

- National Association for Court Management (www.nacmnet.org)

The trend is not limited to state courts. In 2010, 26 percent of all actions filed in U.S. courts—including a colossal 93 percent of prisoner petitions—were filed by pro se parties.4 The Legal Services Corporation (LSC), which is the largest provider of civil legal aid for the poor in the U.S., has estimated that four out of every five income-eligible people who apply for assistance are turned away because the LSC lacks the resources to help them all.5

So where do pro se clients get the expertise to handle legal matters on their own? From law librarians, of course. They ask us to fill out their forms, summarize the law, tell them what to request in court, explain their rights, or proofread their documents. Some say they need “the law” on a certain topic, not realizing that “the law” is usually a patchwork quilt of statutes, cases, federal or state regulations, and maybe a local ordinance. Moreover, “the law,” as a human construct, is subjective, variable, and, in some instances, silent. Try telling that to an overwhelmed pro se.

“Overwhelmed” is a good descriptor. Most of the time, the library is not their first stop on their legal journey. They have tried attorneys (too expensive), legal aid (too busy), and the courthouse staff (too curt). Then someone says to them, “Why don’t you try the library?” By then, it is dawning on them that legal action is more burdensome, drawn-out, and nitpicky than they had imagined. And they will tell you about it. For some patrons, the best service you can provide is to listen.

But, don’t take it personally if they lash out. In one article in Legal Reference Services Quarterly, the law librarian author recalls a patron who had asked for an attorney recommendation. The author tells the patron that he can’t give her one, to which she responds in the obscenely negative. After noting that it had been a rational conversation up to that moment, he muses, “She has a point. I wasn’t giving her the information she needed. As far as she was concerned, I was just part of the bureaucratic run-around.”6 For a while, I was part of that same run-around with Dan, the patron in search of how to handle his right-of-way situation.

For the most part, however, pro se litigants are earnest and hard-working. Like all library patrons, they need you to point them in the right direction, which you can do after conducting a good reference interview.

The Reference Interview

Most legal information requests fall into one of three categories: reference, research, and referral. In each category, requests can be further divided into six types: laws, regulation, cases, subject, procedure, and location.

Reference requests are narrow questions with specific answers. Usually, those answers can be found in a matter of minutes. Research questions are more in-depth—answered in an hour or two, maybe more—and give librarians an opportunity to teach the patron how to identify and use information sources. Referral requests are those best handled by an organization other than the library. Some examples of each are:7

Reference

Laws: Has H.R. 274 been signed into law?

Regulation: I need the current New Jersey Standards for Licensure of Long Term Care Facilities.

Cases: Where can I get the text of Roe v. Wade?

Subject: What does the term pendente lite mean?

Procedure: What is Rule 4.2 of New Jersey Civil Procedure?

Location: Where can I find the laws of New York State?

Research

Laws: Is there a law against owning elephants?

Regulation: What are the legal requirements for transporting formaldehyde?

Cases: I need to locate cases on age discrimination.

Subject: What major federal legislation is pending concerning the environment?

Procedure: What are the basic procedures for suing in small claims court?

Location: What legal sources are available on the internet?

Referral

Laws: I need a copy of the French motor vehicle laws … in English.

Regulation: What licenses will I need to export formaldehyde to Russia?

Cases: Can I sue my employer for discrimination because I was passed over for promotion?

Subject: Is my employer obligated to give me vacation time?

Procedure: Can you help me calculate the proper amount of child support I should be getting?

Location: Who is the best divorce attorney in the state of New Jersey?

Pro se patrons, as I have said, don’t tend to know much about the law. What brings them to the library is a need to take action—say, to respond to a complaint or administrative notice (see Appendix A for a list of actual law library patron questions). The best way to help them is to stay focused on that action. Following are some questions to ask:

Type of Information

- Do you have specific citations or a general subject?

- What is the original source of your question?

- What is the purpose of this research?

- What do you already know about this topic?

Quantity of Information

- Do you need a document summary or the full text?

- Do you need plain language or professional legal texts?

- What is the deadline for this research?

Legal Details

- Do you need laws, regulations, cases, procedures, news, or history?

- What jurisdiction do you need: federal, state, local, or international?

- Do you need the law (i.e., statute or regulation) as it was passed or as it stands today?

Most patrons can answer questions about type and quantity of information. The legal details, however, confuse them. One strategy is to ask if the research is being driven by a printed document such as a legislative bill, court paper, school assignment, textbook, or newspaper article. If so, ask to see the document. You might find clues to help guide the research, such as a bill sponsor, case or statute citation, or court rule reference. When patrons give you incomplete information such as a partial citation or a statute’s common name (e.g., ERISA, Megan’s Law, Title IX), ask for the context of the question. Patrons who want Title IX, for example, usually mean the Educational Amendments of 1972, which means they are likely researching sex discrimination in public schools. When the patron asks you to “look up the law on” a topic, ask her to brainstorm keywords or synonyms. You can match these terms with index headings in an encyclopedia, digest, or treatise. Different resources use different terms for the same topic (e.g., children could appear under infants, minors, or parent and child) so have a legal thesaurus handy. A good one is Burton’s Legal Thesaurus.

Finally, for patrons who can’t seem to give you any details about their research, suggest that they start with a self-help resource. Nolo’s Essential Guide to Divorce, for example, is a great book on that topic. State bar associations often publish plain-language materials that are good places to start. For example, the North Carolina Bar Association website (www.ncbar.org) offers free pamphlets discussing the law on home-buying, domestic violence, worker’s compensation, living wills, bankruptcy, auto accidents, and other topics.

Nine Ways Public Librarians

Can Prepare for Legal Reference

- Read a how-to book on legal research (see Chapter 9).

- Know several academic law library websites to which you can refer patrons (see Chapter 9).

- Learn the fine points of legal citation. Two good beginner sources are Introduction to Basic Legal Citation (www.law.cornell.edu/citation) and Bluebook 101 (lib.law.washington.edu/content/guides/bluebook-101).8

- Learn which branches of government—legislative, judicial, or regulatory—are responsible for which types of legal issues. This helps you know what type of document to help your patron locate: statute, case, or regulation.

- Know the U.S. court structure, as well as the court structure for your state. For U.S. courts, see www.uscourts.gov/FederalCourts.aspx. For all 50 states, see www.ncsc.org/Information-and-Resources/Browse-by-State/State-Court-Websites.aspx.

- Know the basics of articulating a legal issue. What jurisdiction is involved: federal or state? Is it a civil or criminal matter? Who are the parties and what relief is sought (money, injunction, etc.)? Is the issue a substantive or procedural one? Asking patrons such questions often jump-starts the research process.

- Speaking of procedural issues, learn to recognize them. Then refer patrons to your state’s Rules of Civil Procedure, which are found either in the state statutes or in a separate volume owned by any law library. Examples include:

- How do I sue someone?

- I just got sued. What do I do?

- What should my documents look like?

- I didn’t show up for my trial because I never got the notice. What should I do?

- Know where to find judicial forms. For federal, go to www.uscourts.gov/FormsAndFees.aspx. For state, go to www.professional.getlegal.com/research.

- Know when and where to refer people who need to talk to an attorney. Signs that they need a referral are when they avoid doing their own research or when, after listening to their tortuous story for 10 minutes, you have only a fleeting notion of what they want. Good places to refer those in need of an attorney are the bar association lawyer referral service, nonprofit legal aid organization (most have income requirements), and law school clinics (most law schools have at least one).

Unauthorized Practice of Law

A special concern for law librarians serving the public is this: How much service can we provide? Suppose a young, well-dressed patron—we’ll call him Arthur—walks in and approaches the reference desk. “Hello,” Arthur says. “My wife and I are getting a divorce, and neither of us can afford a lawyer. I’ve decided to write the separation agreement for us. Do you have any examples I could look at?”

As you talk to Arthur more, you learn that he and his wife have no children and don’t own a house. Since they have no major property to divide, the divorce should be a simple one. You have looked up divorce statutes for many patrons in the past, so you know that a separation agreement is not essential to divorce in your state, and you want to save Arthur a lot of unnecessary work. You casually mention what you know about separation agreements.

Stop right there. You may have just given legal advice. I know what you’re thinking: You’re not a lawyer, and you never said you were a lawyer, and the conversation occurred in a library, not a law office. Those are excellent points, but they may not matter. If the patron reasonably believed you were a lawyer and reasonably believed your response created an attorney–client relationship, then a jury could find you guilty of unauthorized practice of law (UPL). This is not as far-fetched as it sounds. In one of the most-cited articles on this topic, Yvette Brown points out that pro se users are “unaware of the fundamental differences between the services of an attorney and the services of a librarian,” a confusion that could lead to the accidental transmission of legal advice.9 Having been asked by dozens of end-of-their-rope patrons to tell them what to do or to help them fill out a form, I agree that the boundaries are not as clear to them as they are to me.

The concept of UPL first appeared in the library literature in the mid-1970s and has been frequently discussed, though infrequently agreed upon, ever since. As early as 1971, librarians were expressing their reticence to help pro se patrons: “I would not close off our library to lay persons and say, ‘no lay person can come in,’ except that I do not believe I have the same obligation to them that I do to the members of the bar.”10 In 1976, Robert Begg took this sentiment a step further, arguing that public patrons should pay fees, receive limited service, and be given “the old run-around.”11 (I was unfamiliar with this article when I helped Dan.) More severe still is a 1983 article by C. C. Kirkwood and Tim Watts, who feel that pro se users should not be helped at all unless a specific institutional policy requires it. In their view, a librarian must be prepared to control the flow of information to a user, “turning it on and off like a spigot.” They note that law librarians can’t “hide the law,” but neither should they be “spreading the word.”12

I have watched this ill-disposed attitude on the faces of librarian colleagues, seen it in their bowed heads and crossed arms, and heard it in their not-too-friendly voices. Even I don’t always leap at the chance to help public patrons. Most law librarians, when asked about this reluctance, would probably say they don’t have the time or resources for pro se assistance. Some would agree with the librarian quoted in the previous paragraph who does not see “the same obligation to them” as to “members of the bar.”

I believe there are other reasons, unstated but no less compelling. One is arrogance. Many law librarians have both library science and law degrees, and even though they don’t practice law, they buy into the exalted self-image that is part of legal culture. They know they are capable of the same types of complex research that lawyers do, and they don’t feel challenged by someone who just needs a form. Another is desensitization. Those in crisis-solving professions—doctors, nurses, EMTs, lawyers, engineers, even politicians—often fail to mirror their clients’ urgency because they have usually seen and handled worse.

Law librarians make this mistake as well. We serve hundreds of patrons a day, all needing the same things: musty court cases, byzantine forms, guidelines for this, and rules for that. It is easy to forget that we may be the only law librarian a patron ever encounters, and that the patron’s problem is real and scary and all-consuming to that person, even if it is routine work to us. We have an ethical obligation to provide all the assistance we can while staying clear of UPL violations.

According to contemporary scholars, though, avoiding UPL is actually a cinch. Paul Healey, one of the leading writers on this topic, believes that “the risk of liability arising out of reference interactions is almost nonexistent”—a technical possibility, perhaps, but not a practical one.13 In other words, “no librarian will ever be prosecuted for unauthorized practice of law while engaging in normal reference activities.”14 What are “normal reference activities”? To me, they include:

- Helping patrons find primary or secondary sources

- Explaining the format or use of a source

- Defining legal terms

- Interpreting citations

- Advising on the research process

- Interpreting a case or statute in the abstract (i.e., without relating it to the patron’s situation)

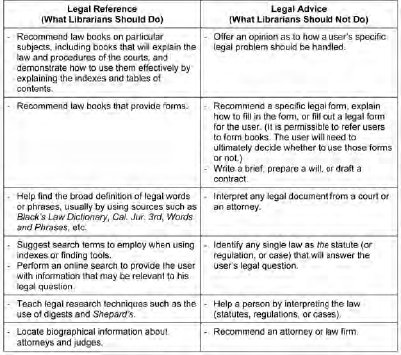

A comparison of what non-lawyer librarians can and cannot do is found in Table 3.1.15

Table 3.1 What Non-Lawyer Librarians Can and Cannot Do

Healy advises librarians to do what we do, use reasonable care, and be clear about boundaries. If we do that, he believes, UPL will be nothing to worry about. Though I agree with Healy, it is still important to be well-informed on the UPL issue. Also, any law library serving the public should have a written policy posted where patrons can read it. Here is an example.

A Message to Our Users About

Legal Reference Questions

It is unlawful for members of the Library staff to help users interpret legal materials they read or to advise them how the law might apply to their situation because these actions would constitute the unauthorized practice of law. It would also require an amount of personal service that a staff of our size cannot provide if we are still to carry out other duties. For those reasons, our staff must limit themselves to advising you which materials might be helpful to you, where they are located, and how to find information in them. Please do not think our staff is being uncooperative when they suggest that you interpret the materials you read for yourself and make your own decisions as to how the material you have read applies to your legal problem. Our staff will be happy to help you find the materials you need, and to show you how to use the various legal publications.

If you need further help to solve your legal problem, you may wish to consult one of the following legal service organizations:

[LIST YOUR LOCAL LEGAL SERVICE PROVIDERS HERE]16

Another example, from the Connecticut State Library:

Law and Legislative Reference (LLR)

Unit Legal Reference Policy

Because library staff members are not attorneys they cannot offer individual guidance in matters involving litigation or legal forms, and they cannot offer legal advice or any interpretation of the law or legal terms.

- Interpretation is defined as the explanation of what is not immediately plain, explicit, or unmistakable.

- Although staff members will be as helpful as possible in locating and providing necessary legal materials, it is the responsibility of the patron to research his or her own legal issues and come to his or her own conclusions about how the law applies to particular situations.

- LLR staff cannot identify any single law as the statute (or regulation, or case) that will answer the patron’s legal question.

- LLR staff may suggest sources and explain the organization and format of those sources to in-house patrons who are attempting to devise a search strategy.

- Staff may assist patrons in the use of catalogs, indexes, and research guides to identify and locate pertinent library and archival resources; assist in the use the collections and electronic reference resources; and assist with the operation of photocopiers and microform equipment.

- Staff may direct patrons in the use of all Connecticut statute compilations and supplements to determine public act numbers for legislative histories.

The Law and Legislative Reference Unit staff responds to telephone, letter, email and fax inquiries that pertain to legal and legislative issues and can be answered from sources within the collection.

- LLR staff may help to find the broad definition of legal words or phrases, usually by using sources such as legal dictionaries and encyclopedias.

- LLR staff may read short quotes from legal materials when the patron has a specific citation (time and policy permitting).

- LLR staff may locate biographical information about attorneys and judges.

- LLR staff may help locate legislative or other background reports or law journal articles, which provide the patron with information that may be relevant to his or her legal question.

- LLR staff may take requests for copies of Connecticut legislative histories when the patron has a specific Public Act number or numbers.

- LLR staff may advise patrons to consult an attorney but they cannot recommend a specific attorney or law firm.17

Extreme Patrons

A patron wants to look up something she “heard somewhere”—say, that the Fifteenth Amendment is due to expire soon. Another patron needs to know how to “officially” copyright his name. (In the library visitor log, he had drawn a © beside his signature.) Still another patron claims to be a Sovereign Citizen.18 She flouts the library’s policy of showing a driver’s license at sign-in by handing over a typewritten card, laminated and with her picture on it, from the “Republic of the United States.” Except she doesn’t think she is flouting the policy; she thinks she is adhering to it. Her card, she claims, excuses her from paying any debt, including income tax. She says she achieved this status by reclaiming her “straw man”—a paper-only alter ego created when a person’s birth certificate is issued—and canceling the straw man’s debts she had unwittingly assumed.

Librarians have faced extreme patrons as long as there have been libraries. Some, like the Sovereign Citizens, are a “growing domestic threat” (see the FBI’s report at www.fbi.gov/stats-services/publications/law-enforcement-bulletin/september-2011/sovereigncitizens). Most, however, are simply misguided, angry, stubborn, or naïve. Because legal questions often involve money, freedom, or life itself (remember Terri Schiavo?), law librarians see more than their share of anger and stubbornness. Because the law is Gordian, we also deal with lots and lots of confusion. Are there special techniques for handling such patrons?

In 2004, two librarians, Amy Hale-Janeke and Sharon Blackburn, addressed this question in a speech at the annual meeting of the American Association of Law Librarians.19 First, they said, law librarians should treat every question seriously and every patron with respect, even the weird ones. Clarify the question by saying, for example, “Could you tell me more? I’m not sure I understand.” Focus on the question, not the patron’s demeanor. If the patron seems sane (i.e., not rambling, disheveled and smelly, prone to outbursts, or talking to unseen companions) then do a regular reference interview.

If the patron is insane,20 still treat him/her with respect, but realize your priorities have changed. Your goal is not to find information—the patron likely won’t even look at it—but to avoid a confrontation. Keep your voice even, your gaze steady, and your movements undemonstrative. Don’t argue with the patron: You’ll frustrate yourself and make him mad, which can lead to violence. Accept his reality. You can even enter it a little. Give him a book and say it’s a secret book, or join her briefly in an absurd digression before steering the talk back to the original request. Maintain boundaries—no touching, no personal questions, no breaking library policy—and call a colleague over if necessary. Above all, understand that you can’t help everyone. Insane patrons often have insane requests, and you are not a failure as a librarian for not meeting such requests.

Law Firm Reference

Library school reference classes assume that you, the librarian, know more about the resources than your patrons. In public and academic libraries, this is mostly true. In law firms, it is not. After 3 years of law school plus any number of years practicing law, attorneys know how to research, and they know the major primary and secondary sources. They know them like old friends and call them by nicknames (see Chapter 2). They even know where most of the books are, because they have used them over and over or because the books are shelved in their offices. Law firms tend to have decentralized collections. At one of my firms, for example, the main library was on one floor, litigation materials on another floor, and corporate law materials on a third floor. Other titles were shelved in hallways, conference rooms, or an attorney’s office. (Surprisingly, this arrangement works. Just note in the catalog that the location for Title X is Attorney Y, and if someone else ever needs it, you know right where it is.)

How do you help such high-functioning, self-reliant patrons?

Types of Requests

For starters, the fact that lawyers can do all their own research doesn’t mean that they will. Some attorneys, especially senior ones, see research as a low-level function, and not something they prefer to spend their time on. From a client’s standpoint, this is a good approach. Suppose you are an executive with a Fortune 500 company, and you hire attorney Smith to handle a legal matter. Smith’s billing rate is $600 an hour. Do you want Smith to spend those hours developing a strategy for your defense, or looking up cases in the library?

Right. Let Smith do what he does. You can look up the cases. This is the biggest difference between reference in law firms and public libraries: Pro se patrons rarely know what they need; law firm patrons usually do. Attorneys will give you a list of citations to cases, statutes, regulations, articles, whatever, and all you have to do is retrieve the documents. Sometimes they give you wrong or incomplete citations, and sometimes all they have is a case name or part of a name. Typical requests are along the lines of: “I’m looking for a case, came out in the last few years, the plaintiff is Jones. Or maybe it was the defendant.” When you get this type of request, ask what the case is about. This will help you narrow down the five or six—or 6,000—cases involving a party named Jones.

Citations are tricky, even for experienced attorneys. Remember writing papers in MLA format? Your handbook might be cotton-field-white with creases, yet you would still have to look up how to lay out the title page or cite a personal interview. Legal format is just as obscure. Attorneys cite cases and statutes all the time, but they struggle with the more obscure formats.

Become an expert in citation and formatting. This is important because some judges will reject an improperly formatted brief. At the very least, the judge will be annoyed, which makes it harder for your attorney to win the case. At one firm, I was sometimes asked to proofread the citations in appellate briefs. Secretaries proofed the grammar and spelling, but with citations, they yielded to my expertise, as did the lawyers. You can make yourself indispensable with this skill.

Another major difference is that many law firm requests do not involve legal information. Instead, you will field requests for medical information, business information, or news articles. Databases are fine for most articles, though there are exceptions. A 30-year-old newspaper article (which I have been asked for) will not appear in most databases, so you might have to find it on microfilm. Also, databases tend to omit charts, tables, and pictures, so if graphics are why the attorney wants the article (another request I have often had), you will have to get creative. Of course, the attorney may want to frame a full newspaper front page from 3 months ago because it pictures a client—or himself. Do the best you can with this.

For business information, see Chapter 7. For medical information, here are a few starting points:

- Lisa Ennis and Nicole Mitchell, The Accidental Health Sciences Librarian (Information Today, Inc., 2010)

- Medical Library Association (www.mlanet.org)

- U.S. National Library of Medicine (www.nlm.nih.gov)

- Medical Libraries on the Web (www.lib.uiowa.edu/hardin/hslibs)

Managing the Requests

Public librarians are usually asked to locate information for patrons on the spot. In a law firm, most requests are not immediate, but they do have deadlines. If the requester does not give you a deadline, ask for one. Also, if the request is for in-depth research, ask what the requester is working on. Appellate brief? Internal memo? Article for the bar association rag? Conference presentation? School paper for the requester’s daughter? (Don’t laugh; I’ve had this one, too.) The answer will affect not only your timeline but also the depth and kind of information you return. Make sure you know how each requester likes to have information sent. Email? Hard copy? If you don’t know, ask. And here is a nice touch: If you find a lot of information—say, three or more documents—include a cover letter summarizing each. Busy attorneys love time-savers like this.

Another major consideration is client billing. If the research is for a specific client, then the firm might bill that client for your time. If so, you would need to track your work (most firms bill in 6-minute increments). Also, if you use Westlaw, LexisNexis, or some other database, you may be able to pass along this cost to the client. Be sure to clear this with the requesting attorney in advance.

Information currency is something else to consider. Law changes daily, yet attorneys don’t always need the latest information. For background knowledge, an old article or treatise works as well as a new one. Attorneys get used to certain titles, and even when the publisher stops updating it, they will want to keep using that title. Is this legal malpractice? Not if they use Westlaw or LexisNexis to update the authorities they find in the outdated text (see Chapter 5). Be sure to ask the requester how current the information needs to be.

Summer Associates

Each year, many law firms hire law school student interns. They are sometimes called summer associates. The biggest firms might hire 10 or 12 of these interns every summer, some of whom will likely be offered full-time positions when they graduate from law school.

Summer associates work alongside senior attorneys on actual cases, often doing all the research for the cases. As inexperienced researchers, they need guidance, not just document retrieval. Two strategies you can suggest are secondary sources or the “one good case” method.

The first thing summer associates want to do is hop on Westlaw or Lexis, plug in keywords, and pull up cases. They will not start with secondary sources because these are scarcely taught in law school. Experienced practitioners, however, often start with secondary sources, which collect and summarize leading authorities. Teach your summer associates to do likewise.

Inexperienced researchers like summer associates often try to find everything at once. Through broad keyword searches on Westlaw or Lexis, they cast their net wide, hoping to bring in dozens of useful cases at once. Encourage them instead to find “one good case” (i.e., a known case on point that can be used, through citators or the West Key Number System, to find other relevant cases). How can a summer associate find this “one good case”?

- Word of mouth, or asking the supervising attorney to recommend one

- Secondary sources

- Annotated statutes, or finding a relevant statute (if there is one) in an annotated code and looking through the case notes

Law Firm Culture

Some attorneys love research and will be your biggest patrons. Others hate it and will never darken your door. Learn which is which. Also learn which high-ranking attorneys will talk to you directly and which leave the interaction with you to other support staff.

Remember Gabriel, the grumpy managing partner from Chapter 1? Through Preston, the office administrator, Gabriel had asked me to do some research. A question came up about the research, so I emailed my question to Gabriel. Within minutes, Preston, not Gabriel, called me with the answer. Some time later, I had another question for Gabriel, so I emailed him again. This time, Preston responded in 60 seconds. “Did you just send Gabriel another email?” he asked.

Now, I get that Gabriel was a busy man, but in the time it took him to forward my emails to Preston, he could have answered me himself. Why didn’t he? A law firm caste system, I suppose. Preston implied as much as we discussed my breach of etiquette. “I know the politics of the place,” he said, meaning that he could help me a lot if I would let him. I did, and he turned out to be a valuable advocate for the library.

Every law firm has a personality. Learn yours. Maintain whatever illusions you are asked to maintain, at least until you have earned enough respect to shatter them. When I had my wall-building discussion with Preston, I had not been at this firm long. Later, once I had proven myself, those walls came down. I started going to attorneys’ offices, stopping them in the halls, asking them what they were working on and how the library could help. I got a lot more business this way, but more important, I won the attorneys’ trust. In law firms, librarians, like secretaries and paralegals, will always be support staff, but that doesn’t mean you have to act like it. Present yourself as an intellectual equal, as qualified as any attorney to discuss research matters—in other words, a colleague. Sooner or later, they’ll treat you like one.

Listen to Your Patrons

Different patrons require different service approaches. To know what your patrons need, listen to them. Too often, when a patron starts talking, our minds skip ahead to sources and strategies, and we don’t even hear the whole issue. We avoid active listening.21 Or, we respond with why we can’t help—the question is too in-depth, the information doesn’t exist, we can’t give legal advice, blah blah blah—instead of exploring how we can. Legal reference has unique considerations, but none should outweigh the ethical obligation of all librarians: to “provide the highest level of service to all library users through appropriate and usefully organized resources; equitable service policies; equitable access; and accurate, unbiased, and courteous responses to all requests.”22

Endnotes

1. For a thorough discussion of this, see Marguerite L. Butler, “Rule 11 Sanctions and a Lawyer’s Failure to Conduct Competent Legal Research,” Capital University Law Review 29 (2002): 681–717.

2. 1 Stat. 73, 92.

3. Texas Access to Justice Commission, “Pro Se Statistics,” accessed November 20, 2012, www.texasatj.org/files/file/3ProSeStatisticsSummary.pdf.

4. “Civil Pro Se And Non-Pro Se Filings, by District, During the 12-Month Period Ending September 30, 2010,” Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, accessed November 20, 2012, www.uscourts.gov/uscourts/Statistics/JudicialBusiness/2010/tables/S23Sep10.pdf.

5. Paula L. Hannaford-Agor, “Helping the Pro Se Litigant: A Changing Landscape,” Court Review 39, no. 4 (2003): 8–16.

6. Mike Chiorazzi, “Just Another Wednesday Night: And You May Ask Yourself, Well, How Did I Get Here?”, Legal Reference Services Quarterly 18, no. 4 (2001): 1.

7. Examples courtesy of the Morris County Library in Whippany, NJ. Lynne Lover, “Legal Reference: Tips and Techniques,” Highlands Regional Library Cooperative, February 11, 2000, accessed November 20, 2012, www.gti.net/mocolib1/demos/legaltip.html.

8. The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation is the manual followed by all U.S. and state courts. There are alternatives, most notably The University of Chicago Manual of Legal Citation, also called The Maroon Book. It is not on the verge of replacing its cyan counterpart. I have never used it, and no one I know has ever used it. I don’t even know the difference between the two.

9. Yvette Brown, “From the Reference Desk to the Jail House: Unauthorized Practice of Law and Librarians,” Legal Reference Services Quarterly 13, no. 4 (1994): 31–45.

10. “Reader Services in Law Libraries—A Panel,” Law Library Journal 64, no. 4(1971): 486–506.

11. Robert T. Begg, “The Reference Librarian and the Pro Se Patron,” Law Library Journal 69 (1976): 26–32.

12. Kirkwood, C. C., and Tim Watts, “Legal Reference Service: Duties v. Liabilities,” Legal Reference Services Quarterly 3 (Summer 1983): 67–82.

13. Paul D. Healey, “Pro Se Users, Reference Liability, and the Unauthorized Practice of Law: Twenty-Five Selected Readings,” Law Library Journal 94, no. 1 (2002): 133.

14. Ibid., 134.

15. Joan Allen-Hart, “Legal Reference v. Legal Advice,” Locating the Law: A Handbook for Non-Law Librarians, 5th ed. (Los Angeles: Southern California Association of Law Librarians, 2011): 49.

16. Ibid.

17. “Law and Legislative Reference (LLR) Unit Legal Reference Policy,” Connecticut State Library, September 28, 2010, accessed November 20, 2012, www.cslib.org/legalref.htm.

18. See “Domestic Terrorism: The Sovereign Citizen Movement,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, April 13, 2010, accessed November 20, 2012, www.fbi.gov/news/stories/2010/april/sovereigncitizens_041310.

19. See Rhonda Schwartz, “Say What?! How to Handle Reference Questions from Patrons Who Seemingly Inhabit an Alternate Universe,” AALL Spectrum, Sept./Oct. 2004, pp. 20–21.

20. For advice on dealing with mental disabilities, see www.nami.org or www.nmha.org.

21. “Active Listening,” Conflict Research Consortium, 1998, accessed November 20, 2012, www.colorado.edu/conflict/peace/treatment/activel.htm.

22. “Code of Ethics of the American Library Association,” Intellectual Freedom Manual, 8th ed., January 22, 2008, accessed November 20, 2012, www.ifmanual.org/codeethics.