The body, that complicated machine, carries out the most complex and refined motor activities under the influence of such psychological phenomena as ideas and wishes. The most specifically human of all bodily functions, speech, is nothing but the expression of ideas through a refined musical instrument, the vocal apparatus. All our emotions we express through physiological processes; sorrow, by weeping; amusement, by laughter; and shame, by blushing. All emotions are accompanied by physiological changes: fear by palpitation of the heart; anger by increased heart activity, elevation of blood pressure and changes in carbohydrate metabolism; despair by a deep inspiration and expiration called sighing. All these physiological phenomena are the results of complex muscular interaction under the influence of nervous impulses, carried to the expressive muscles of the face and to the diaphragm in laughter, to the lacrimal glands in weeping, to the heart in fear, and to the adrenal glands and to the vascular system in rage. The nervous impulses arise in certain emotional situations which in turn originate from our interaction with other people. The originating psychological situations can only be understood . . . as total responses of the organism to its environment. (Franz Alexander, 1950, Psychosomatic Medicine, pp. 38–39)

Vienna was invaded by the Nazis in 1938. The totalitarian fascists and communists dominated almost all of Europe. Obliged to leave Europe (only England and Switzerland were still able to resist), the first psychoanalysts were dispersed across other continents. Most of the members of the Berlin institute immigrated to the United States. This country was so immense that they lived relatively far from one another. They only saw each other at the occasion of reunions and at congresses, which changed their relationships as friends to mostly that of colleagues. The competition between them became more evident. The spread of the movement increased after Freud’s death in 1939. Everyone was free to define what Freud would have thought or what psychoanalysis ought to become. Several members of the Berlin group continued to reflect on the connection between mental treatment, somatic treatment, and treatment via the body. In spite of the differences on the plane of psychoanalytic theory that was crystallizing, the interest in the body remained as a link from the past, as a memory of friendship and camaraderie.

Thus, Franz Alexander (in Chicago) and Sándor Radó (in New York)1 tried to integrate the works of Walter Cannon2 to be able to propose a psychosomatics of psychoanalytic inspiration.3 Otto Fenichel established himself in Los Angeles in 1938. He reconnected with colleagues like Ernst Simmel and Hanna Heilborn, whom he eventually married.4 Fenichel (1945a, 1945b) vaguely felt that Alexander’s psychosomatics was not going in the right direction because he was remaining too loyal to the classical psychoanalytic view of a psyche that influenced physiology while symbolizing it. Alexander and Radô seemed to underestimate the impact of physiology on the psyche.5 Fenichel felt that psychoanalysis could and ought to maintain its rigor, but it also ought to integrate the innovations of psychophysiology and the body-focused approaches.

Alexander’s and Radô’s formulations were, for Reich, pale copies of his theory, which they would have imported from Berlin. Erich Fromm maintained his contact with some of Elsa Gindler’s students, such as Charlotte Selver and Clare Fenichel. Laura and Fritz Perls, who were in South Africa during the war, first reunited with Selver in New York and then in California to create what became Gestalt therapy and the mix of psychotherapeutic and body approaches that characterized the activities of the center they established in Esalen. In all of these movements, the body is often solicited while remaining only a chapter in the repertoire of techniques in psychotherapy.

For Otto Fenichel, the following issues were crucial for the survival of psychoanalysis:

There are two powerful forces behind this second field of interest. The most important is that medicine intends to treat all the ills on the planet. Second, but nonetheless influential, is the idea set forth by Freud that trauma could and ought to be treated by psychoanalysts. Already at the time of World War II, a ferocious competition existed between two camps.

Cannon’s psychophysiological position was on the way to making spectacular advances. This was especially due to the works of another Viennese: Hans Selye.6 The psychophysiological theory of stress was in the process of being formulated. It postulates a profound interaction between behavior and mind that is regulated by neurological circuits and hormones. To the extent that, for Selye, the pertinent mental factors are mostly cognitive, this approach forges an alliance with the cognitive therapies7 to manage the mental factors of stress. This trend was followed closely by the introduction of medications that have an effect on the mind as early as 1951 by Henri Laborit and his colleagues.8

Given the importance taken on by this trend, Fenichel was not surprised to see all of these psychoanalysts congregated around Cannon’s theory like bees around a jar of honey. Fenichel clearly saw that they did not understand what was at stake and they did not really grasp the implications of the psychophysiological approach of the time for psychoanalysis. Reich did not take a position in this competition. His options were not compatible in an institutional enterprise.

Any misuse of an organ is psychogenic too. (Fenichel, 1945a, XIII, p. 236)

In Los Angeles, Otto Fenichel began to write a short book, Problems of Psychoanalytic Technique, based on the last courses he had given in Vienna. In this work, which appeared in 1941, he attempted to summarize the essence of the technical questions that preoccupied the clinical psychoanalysts of the 1930s in Europe. It consisted in keeping alive a heritage from Freud in a rapidly changing world.

In this book (chapter VII, p. 122f), Fenichel becomes openly critical of the approach developed by Reich in Oslo and then in the United States. His criticism focuses on Reich’s psychotherapeutic techniques. Fenichel again praises the Character analysis and continues to find it useful to approach the mind as one of the cogwheels of the organism. But he finds that in his interventions, Reich approaches the defense system as if it were an illness, whereas for Fenichel, it is somewhat an equivalent of the immune system. According to him, Reich’s approach is centered on trauma in a simplistic manner. He encourages his patients to experience, from the start of a process, profound and retraumatizing “theatrical” emotional discharges. Fenichel also points out to his colleagues that Reich has “entirely distanced himself from psychoanalysis” (Fenichel, 1941, p. 122; translated by Marcel Duclos). In short, Fenichel finally dares to express that he disagrees with Reich’s recent options and chooses his camp. In Oslo, Fenichel represented an all-powerful psychoanalysis, directed personally by Freud, in the face of a disgraced Reich. Now, the future of psychoanalysis seems more uncertain. The future stakes are too important for Fenichel to lose his remaining energy in a battle with someone who despises everyone. Fenichel quotes Reich to the end of his life, but only what Reich wrote before 1936.9

We have seen that Fenichel was also very critical, for other reasons, of the psychosomatics proposed by Alexander and Rado. He felt the need to synthesize his thinking on the relationship between mind, organism, physiology, behavior, and body. He revisited his discussions with Elsa Gindler, Clare Fenichel, Wilhelm Reich, and Trygve Braatøy; and he also took up in a more systematic way the more physiological approaches on the dynamics of the organism, like those of Kurt Goldstein and those of Walter B. Cannon.10 He published, in 1945, this synthesis in chapter XIII of The Psychoanalytic Theory of Neurosis, which was his testament.

Fenichel’s position is that of a flexible parallelism, like that of Laborit. It differentiates each of the dimensions of the organism: thoughts, drives, physiology, behavior, and body. Each dimension is a distinct causal network. When you throw a stone into the water, ripples form around the stone’s point of entry. The same thing happens when a dream generates a fear that creates muscular tension, and a constricted respiration. This respiratory reaction spontaneously activates a physiological causal chain that may have nothing to do with the fear. The lack of oxygen will automatically influence the quality of the blood, the tissues, the metabolic activity, and so on. The same thing happens when a stomach ache is caused by a piece of spoiled meat that creates a pain that activates a dream. This dream inserts itself into a network of mental associations that was already in place before the food was swallowed.

I would take, as an example, the well-known link between anxiety or aggression and stomach ulcers.11 Anxiety can activate a physiological activity that causes a stomach ulcer. This ulcer will pour stomach acids on the surrounding tissues. Some tissue damage will remain and can last even if a psychoanalytic treatment allows for the reduction of this anxiety. On the other hand, the suffering caused by an ulcer of physiological origin can resonate with unconscious mental content and can activate terrors repressed long ago. These terrors can, in certain cases, continue to develop in the psyche after the ulcer has been treated with medication or a surgical intervention. Even if a psychoanalytic treatment reduces and transforms the initial anxiety, the stomach will continue to attack the tissues in its immediate environment for as long as it is not healed. Fenichel’s core argument is that the anxiety may have been activated by the psychological defense system, but not with the intention of causing an ulcer. The ulcer is sometimes an unexpected consequence of the anxious reaction. In other words, psychological defense mechanisms depend on a local causal chain, which cannot integrate all the implications of the strategy that emerged in the psyche.

We will see, a little later on, that in Oslo, psychoanalyst and psychiatrist Trygve Braatøy, one of Fenichel’s students, undertook psychoanalytic treatments in collaboration with a physical therapist, Aadel Bulow-Hansen.12 The same patient could be in psychoanalysis with Braatøy and in a massage therapy that addressed his muscular armor. In this case, body and psyche both received an in-depth treatment in parallel. What remains unclear in this endeavor is the connection between these two dimensions. There are explored on two levels:

Fenichel and Braatøy know that the interactions between psyche and body are still poorly understood but that they regulate themselves without the help of consciousness. They content themselves with observing with as much accuracy as possible how the various systems of the organism react to what has been elaborated in psychotherapy and how the psyche integrates what has been activated in a massage session.

The modern term “psychosomatic” disturbance has the disadvantage of suggesting a dualism that does not exist. Every disease is “psychosomatic.” (Fenichel, 1945a, The Psychoanalytic Theory of Neurosis, p. 237)

One of Fenichel’s key ideas is that the organism calibrates itself in function of what it does.13 In other words, the mind can interact with physiological and behavioral dynamics,14 and behavior can influence physiological and psychological dynamics. By regularly moving in a particular manner, I influence the development of my body, physiology, mind, and relationships with others. The dimensions of the organism mutually influence each other by passing through internal pathways (situated in the organism) and external pathways (passing through the social rituals and relationships with others). This coordination between dimensions can be initiated by any dimension. Being obliged to sit in an uncomfortable chair, an employee can create a series of disagreeable implications at the level of the body, physiology, the emotions, thoughts, and so on. As some habitual behaviors can be acquired without having a conscious process to integrate them, they “may influence organic functions in a physiological way, even if these changes have no psychic ‘meaning’” (Fenichel, 1945a, p. 256). In other words, every habitual event of the organism necessarily influences all of the dimensions of the organism to a certain degree, as well as their way of coordinating each other; but these changes are not necessarily functionally related. Each dimension is animated by a particular set of causal chains.

For the purpose of situating the interventions on the interfaces that link psyche and soma, Fenichel differentiates the classic conversion neuroses (the psyche influences the physiology) and the neuroses of the organs in the following fashion:

The following are a few points developed in Fenichel’s chapter that are still relevant:

Even though this view is close to the one adopted by most of the current schools in body psychotherapy, none make reference to these writings. Everything is carried out as if this analysis had never been heard. It is possible that this view of the rapport between body and mind was orally transmitted to Fenichel’s students, who took it up as their own, in Oslo as well as in California.

For example, we find in Fenichel’s chapter a critique of the notion of the Reichian emotional discharge that is close to recent critiques of neo-Reichian approaches.17 A good example is that of Fenichel’s idea that a psychoanalysis tries, before anything else, to reactivate all of the repressed experiences. This was also one of Reich’s war horses in his Character analysis. According to Fenichel, to content oneself by expressing emotions that are not closely related to repressed situations is to permit these expressions to reinforce the defense system. A patient, tears in his eyes, rage in his fists, tells you a true story that moves him today. Sometimes, the poignant intensity of the account resides in the fact that the emotions draw their strength from other situations that are not yet perceived consciously by the patient. The memory that arises is the first of a whole series of layers of memories quite different from one other. When the therapist becomes hypnotized by this first reminiscence, he may find himself trapped, as if at the foot of a tree that hides his view of the forest. By capturing the attention of the patient and the therapist, this memory, full of touching emotions that evoke empathy from the therapist, plays the same role as that of a manifest dream. It is but a small part of the experience that the patient needs to reexperience to understand and restructure himself. By deeply exploring this memory and its associations, therapy risks reinforcing what separates this memory from the latent experiences that are unconsciously associated to it. The therapist who believes that theatrical emotional expression of dramatic and moving events allows him to understand his patient’s deeper feelings is a bit like Christopher Columbus who believed he had reached India when he arrived at the Balearic Islands. He takes a huge step in the right direction, but he will not necessarily succeed in forming a clear vision of what is growing in the patient’s unconscious. As you well know, the question is not even that the Balearic Islands are not India, but that, between the two, there was a new continent.

At the death of Fenichel, Reich wrote this in his notes:

20 February, 1946

I found out that Otto Fenichel died of a heart attack three weeks ago.

That man died of his structural cowardice, I cannot judge whether my publication of his misdeed which appeared in April 1945 gave him a push. In his book he plagiarized everything from me and since he was aware of this it must have been a terrible ordeal for him. (Reich, 1999)

There is no way of basically changing people once they have developed the wrong character structure. You cannot make a crooked tree straight again. Therefore lets concentrate on the newborn ones, and lets divert human attention from evil politics towards the child. (Reich to Neill, October 8, 1951)

Reich departed from Oslo on August 20, 1939, for New York. There he was welcomed by colleagues like Theodore P. Wolfe, who translated many of Reich’s works into English. He did not seem to have any contact with his old psychoanalytical companions from Berlin, because he now represented a theory that could undermine the foundations of their approach.

Reich’s theory was now resolutely “vitalistic.” In 1940, he had acquired18 enough money to be able to isolate himself in the wilds of Maine not far from the Canadian border, on a property he named “Orgonon.”19 There, he pursued his experimental research on the way that cosmic energy, which he called orgone,20 animates every cell and the global regulators of the organism. This notion is a sort of synthesis between (a) the force of nature described by Spinoza, (b) the vitalism of Jung,21 and (c) Freud’s libido. Reich attempted to analyze this cosmic force scientifically and propose a medical approach based on his observations.22

His Vegetotherapy thus becomes Orgone therapy. The principal difference, on the plane of mind-body techniques, is that Reich was less interested in the movements that go from head to foot during an orgasm and focused his attention on the regular pulsations of the organism, which contract and expand unceasingly like a great heart or lungs. To work on a thought or a tense muscle is part of a panoply of methods that make it possible to influence the quality of the pulsation of an organism and its capacity to auto-regulate. During this period he intensifies his research on machinery capable of mastering the dynamics of the orgone like the orgone accumulator.

As early as 1930, the politics in Europe were so disastrous that by contrast, the United States was gradually perceived as a possible haven of peace. When Reich and Fenichel arrived in the United States, they tried to believe that they were landing in what could become a robust democracy. Fenichel, happily for him, died at a time when it was possible to think that he was living among those who defended freedom in the world. Reich quickly discovered that the United States was only a bit better than the Soviet Union. After the euphoria following the victory against Germany, Italy, and Japan, he became increasingly pessimistic about the democratic potential of the United States. At first, there had been the interminable discussion by the armed forces on the use of the atomic bomb. The racial discrimination against blacks was everywhere. And then there was the persecution of the communists. For example, Charlie Chaplin was persecuted as early as 1947 for being a communist sympathizer; he went into exile in Switzerland in 1952. Paradoxically, Western Europe was becoming more democratic than the United States, thanks to the Marshall Plan.

Little by little, the United States developed a “social cancer,” the third that Reich had witnessed in his life, called McCarthyism, which lasted from 1950 to around 1956. This movement was certainly less terrible than Stalinism and Nazism, but Reich was surprised to encounter it in the country that exemplified democracy. This time, he was crushed, morally at first, but mostly by being imprisoned where he died. After the advent of Stalinism in the country of the Marxist hope and McCarthyism in the country of democratic hope, Reich definitely lost confidence in the humanity of his day. A good example of the way McCarthyism destroyed individuals like Reich is the film Lenny, directed by Bob Fosse with Dustin Hoffman in the lead role.

At first, Reich hoped that once people would lose their armor and the secondary layer of hate that is imbedded in constricted tissues, their Orgonomic core would regulate their organisms and the way they interact with others and with nature. Doubt crept in when he and Neil had children they could raise in homes that promote self-regulation. At first the two fathers thought that in such a supportive context, both children would spontaneously do what they needed. Their organisms would know when to sleep and when to eat. However, in their correspondence, both shared the observation that even their children appreciated being nasty at times, and that self-regulation was not enough:

Have you considered the sleep angle? Recently our kids have been breaking all bedtime laws. A meeting was strict about them, and for a week they have gone to bed early. Result: most of the bad tempers, destructiveness etc. have lessened greatly. (Neill to Reich, December 12, 1948).

The surrounding political events of the 1950s strengthened their impression that no one could escape having a hateful layer and an armor.

At age fifty, Reich theorized to support the generations to come, to help them to build a less ferocious world and one more respectful of the nature that animates them.23 Therefore, he undertook, with a few friends like the educator Neill and his daughter, Eva Reich (an obstetrician), a profound reflection on what one could hope for the humanity of the future. He began to study the birthing rituals. For him, the only way to repair a humanity harmed by millennia of tyrannical and religious destructiveness was to begin the work at this level, that is, by studying the social and psychological ways that humans conceive (in every sense of the word) their offspring. For Reich, it was not possible to respect oneself without respecting nature and the universe of which we are an integral part. To detest what we are is to hate the nature that animates us. We will see, in our discussion of Ed Tronick’s studies (see chapter 21, p. 623f), that repair systems undoubtedly exist in human organisms. They can be supported to become increasingly efficient. However, even these forms of healthy repair systems do not follow the laws of Idealism and of the orgone. They seem to follow the general laws of the theory of evolution: they are not perfect, they can even generate mechanisms that lead to destructive behaviors.

After launching an anticommunist movement of the left, Wilhelm Reich became one of the precursors of ecological thinking. Reich’s vision24 was in part taken up by the youth movements of the 1960s in America and Europe. Fenichel’s and Reich’s careers began with youth movements. It is through them that Reich became known again after his thought was banned for a dozen years.

With such preoccupations, Reich was no longer interested in what was at stake in the world of psychotherapy.

All psychological manifestations of the schizophrenic process had to be understood in terms of deep biophysical processes which underlie and determine the functions of the mind. Our assumption is that the realm of the psyche is much narrower than the realm of biophysical functioning. (Reich, 1949a, XV.44, p. 433)

Reich’s research on vital energy began in Oslo.25 It is thus one of the topics on which he and his collaborators worked for the longest time. Nonetheless, this research did not go beyond the stage of imaginative studies on interesting speculations. It is not unusual that a creative person is not known for what he has the most passion for; history does not retain his works on the topic. In the same way, we do not study Kepler’s astrological thought today. But a certain number of isolated propositions, formulated in the context of the studies on the orgone, have influenced numerous practices and merit a brief description in this book. For example, Reich’s interest in the stakes involved in pregnancy and the birth process remains relevant. Eva Reich stayed in touch with the research on childbirth by Frederic Leboyer (1974) and Michel Odent (1976), and she even contributed financially to some of Odent’s research to validate his approach.

The hypothesis that affective dynamics participate in the development of some cancers is still not confirmed by scientific research, but it remain a focus of research that reappears periodically in professional journals.26 This topic presupposes that we imagine the existence of connections between affects and metabolic dynamics (chemical and energetic). Reich explored this connection when he studied the dynamics of the fluids of the organism and the vitality of blood cells.

Other themes from Orgone therapy have their place in a psychotherapy textbook to the extent that they can be integrated in a theoretical context close to actual scientific knowledge.

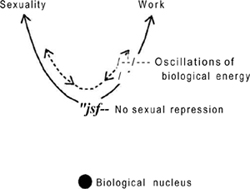

According to Reich, the circulation of orgone in the organism gives a sensation of pleasure, like Freud’s libido. Those who experience this circulation with anxiety have developed, in the course of their lives, a fear of the pleasure of being alive. This statement refers to a pleasure that can become intense. Thus, some people are not afraid of small pleasures but are afraid of an orgasm, or the love that can be created between parent and child. Freud’s libido is thus a manifestation of the orgone. Reich ends up proposing that in the organism, the orgone has two basic modes of expression: sexual love and the creativity linked to work. These two creative energies coordinate the internal dynamics and social dynamics and are found in the activity of all the species. Creativity also has its somatic organization (fine motor activity, the brain, etc.). In psychotherapy, this implies that self-expression through one’s work is as important as self-expression through sexuality and that the repression of these two basic needs can damage in the vegetative dimension.

The central importance of a professional integration of not only the mental equilibrium but also the health of the organism is confirmed by numerous research studies on the impact of unemployment on mental and physical health. This stream of research began with the works of Austrians Marie Jahoda, Paul Felix Lazarsfeld, and Hans Zeisel at the occasion of the 1929 Great Depression. Reich probably heard of these studies. These first observations have been robustly confirmed since that time.27 From the point of view of body psychotherapy, the accent is placed on the fact that a profession is one of the principal modes of calibrating behavior and psyche. The gestures develop in function of the needs of a team; the mind is formed by preoccupying itself with the management of the information that allows for a professional or occupational practice that is recognized by economic and cultural networks in which an organism integrates itself. In this perspective, creativity and sexuality are, at the same time, two necessities and two forms of pleasure.

In becoming increasingly interested in the manifestations of the orgone in the organism, Reich further studied the dynamics and quality of organic fluids. He also observes more closely the quality of the metabolic activity of the tissues. These can be more or less supple, more or less saturated with metabolic wastes or more or less irrigated. In certain body psychotherapy practices, like mine, the quality of the gaze and the skin becomes as pertinent than the analysis of muscular tension (Thornquist and Bunkan, 1991, 5.5.5, p. 55). The idea would be that the tissues reflect in a particularly refined way the nuances of the interaction among affective, metabolic, and vegetative dynamics.

I have the impression, for example, that for some people, the quality of the skin varies in a particularly identifiable way in function of a depressive mood and sexual satisfaction. The skin can be more or less dry, tight, transparent, pink, supple or soft, and with more or less marked wrinkles. At the occasion of an anxiety attack, I sometimes observe that around the mouth the pores of the skin become enlarged or tight, change direction, while the skin is slightly jaundiced or gray. I then put forth the hypothesis that the patient is living a form of anxiety that Freud associates to orality (for example, when there is an unconscious rage against someone on whom one is dependent). Once one knows the phenomenon, it is easily noticed. It usually escapes observation if one is not trained to see it.

This interest in the fluids and the tissues is also a topic explored independently by biologists (Pert, 1997; Vincent, 1986) and by some body psychotherapists (G. Boyesen, 1985a). It is probable that this topic will be explored in an evolving way in the years to come.

Reich’s orgone is, above all, a force that animates everything that exists. Without this force, nothing would exist. It is also a force that gives itself a shape, a contour, and a dynamic. The orgone creates and forms the atoms, the cells, the organisms, the planets, and the galaxies. In the human being, the orgone is the metabolic activity of all of the cells, especially those of the blood that transports the oxygen, the nervous systems that transports information, the sexual dynamics that have an impact on genetic dynamics, the skin that regulates the transaction between the internal and external environment, and so on. The intensity of the cellular activity is the basic support of all these functions. The greater the vitality, the more the operations carried out by the organism has the means to accomplish their tasks. For this activity to take shape, the organismic activities must find a dynamic and an appropriate rhythm, a mode of functioning that allows each task to accomplish its functions. For Reich, the basic dynamic of the orgone is pulsation. Each and every entity has its own proper pulsation. Pulsation makes it possible to contain mobilized orgone. When there is no pulsation, the energy loses its organizing quality and becomes a destructive energy that leads to anorgonia (negative orgone). In pulsating, a system acquires its shape, contour, rhythm, and force—in short, its dynamic properties. The orgone would generate the pulsations of respiration and the heart, the oscillation between wakefulness and sleep, and the feelings of openness and closure toward those around us. Often, social obligations poorly respect the needs of organisms. They thus reduce the amplitude and the rhythmic regularity of the pulsations that structure an organism. This may lead to a pollution of the orgone (e.g., metabolic wastes accumulate in the tissues) that produces various forms of anorgonia.

Over a dozen years, Reich imagined that this pulsation of the orgone existed at the core of each of us. The repressive evil of the social dynamics create a kind of obscure world around this central kernel of life. This secondary layer is full of hate, anger, sadness, and rancor which haunts and animates the history of human societies for past millennia. A third layer forms itself at the surface of the being to create an apparently friendly mask that hides from the eyes of others this intolerable hell that proliferates between the mask and the core. This mask draws its inspiration from the forces of the orgone to propose a message of love and gentility, a becoming aesthetic and compassion that resonates with empathy with the repressed depths in the kernel that animates us. There is something quite complex at play in this. Such as:

Reich concluded that healing passes through a strengthening of the core organismic pulsation28 which requires that the conscious dynamics learn to acknowledge and integrate this force and that the organism learns anew to live as a global pulsation. As early as 1933,29 Reich sometimes asked his patients to explore a movement that sets the entire body into a pulsation. Lying on his back, the patient oscillates between a phase of extension (the arms and legs are as far as possible from one another) and a phase of condensation (feet, hands, and head as close as possible to each other). This oscillation is done in coordination with respiration (deflating and breathing out, extension and breathing in). Having performed this exercise several times, the patient may experience, after a while, the impression of being a global pulsation that moves the body, the respiration, and the sensations of the body. The organism thus recovers a flexibility that allows its pulsations to animate its systems of auto-reparation. Reich proposes that the patient move like a jellyfish propelling itself in the sea.

The persons who can feel these pulsations in their organism, have, according to Reich, a good organ sensation.30 Some individuals can feel the pulsation of their brains, which can become especially evident at the occasion of an osteopathic massage of the cranium.31 Some women can feel when they ovulate, and others do not even notice that they are pregnant by the end of the first trimester.

GLOBAL PULSATION

Most humans have sometimes had the impression of being a global pulsation. It generally consists of pleasurable moments, tied to relaxation after an intense activity (what Reich calls the reflux): after having made love with delight, after a good massage or a relaxation exercise, after having exhausted oneself playing sports. The individuals who appreciate this type of sensation often declare having the impression that “the energy circulates everywhere,” that they feel “alive and whole,” that they have the feeling of being “one.” Others are anxiously troubled by these sensations. For example, they experience the impression of being depersonalized, or they are made anxious by an unfamiliar sensation, by something out of their control. The customary explanation of the Reichians is that the anxious reaction is symptomatic of an organismic constriction, which can be experienced as an identity problem, an impression of being uprooted, whereas the capacity to experience the pleasure of the global pulsation is a sign of health, strength, and maturity.

For Reich, being an immense pulsation is what is experienced when an individual accepts to feel the orgone that circulates within. Even if Reich’s explanation cannot be maintained, his description allows one to grasp certain psychic experiences related to the organism in a particularly explicit fashion. In other words, we would have an example of an erroneous theory that has permitted the observation of a phenomenon that is useful to integrate, especially in a body psychotherapeutic approach.32 I have experienced this sensation, and some of my patients have also described it. Therefore, clinical experience allows me to confirm that focusing on the experience of being a global pulsation is a useful therapeutic tool, but I have no valid way of explaining it. I have no problem admitting that I cannot explain all that I observe.

THE ATROPHY OF THE PULSATION

Sometimes a patient who comes to a psychotherapist for a consultation describes an impression of “constriction.” Everything in him seems to have dwindled. His gestures are weak, the skin sensitive and pale, a dull look, hair in poor condition, weak breathing and voice. I have often used this term33 to describe what is for Reich one of the basic forms of the discontent that is experienced as soon as forces try to inhibit the spontaneous pulsations of the organism. In the case of an extreme constriction of the organism, most of the therapists, whatever their approach, have the same prudent reaction to want to create a mobility, a pulsation, an internal space that leads to an appearance opposite the one I just described: like radiance, flexibility in the respiratory rhythm, and enhanced mobility.

With the notion of pulsation in mind, the intervention becomes more targeted. It does not consist of proposing to this individual a diametrically different behavior but to gradually augment his repertoire. A constricted individual moves very little but cannot remain immobile. He is tired but sleeps badly. He is trapped in a narrow repertoire of organismic states. The notion of pulsation evokes an analysis that takes the following elements into account:

The same variables can be used to analyze a relationship. In a couple, some individuals have a difficulty finding space to be alone or to be sexually unavailable. The oscillation of states like being at ease with the other/with oneself, intense sexual arousal/being turned off, creativity/laziness are common with most people, but it is rarely tolerated by the other or by oneself. To permit the partners in a couple to mutually authorize each other to have different rhythms and negotiate these transitions is often useful. The important point, which is evident when we consider the notion of vegetative pulsation, is that the two phases cannot occur simultaneously. It is not possible to be fully attentive to oneself and the other at the same time except in particularly intense moments (e.g., when one falls in love). It is not possible to be here and there; but we can be here in one moment and elsewhere in another. To admit to this, and to have it admitted, is an example of relational work based on the notion of pulsation. Theoretically, this point seems evident. In practice, I notice that many people reproach themselves for not being able to be calm and enthusiastic at the same time. With this type of analysis, the therapist can avoid the cliché commonly used, like the notion that a patient is “closed” when he opens himself up to internal sensations, and “open” when he is available to communications from the other. What the Reichian therapist then defends is the possibility of oscillating between openness to oneself and openness to another. This pulsation can have different timing. The oscillation can happen in a few seconds or a few months. The state of constriction is a closing off to self and others, like in certain extreme types of depression. Knowing how to pass from one state to the other is vital.

THE CIRCLE OF RESPIRATION IN PULSATION

In analyzing the relationship between pulsation and respiration, we again find the four moments of respiration already described in the sections on the methods from the Far East and gymnastics.34 Like the Hindus and the Chinese, and like Freud for a brief moment,35 Reich conceptualizes four phases of mobilization that are also four phases of the circulation of energy. This activation rises up the back, passes through the cranium, and returns down over the ventral surface toward the genitals.36 This current is associated to the movements of the fluids and respiration.37 There would be a connection between the flux (ascending energy, mobilization, inspiration) and reflux (descending energy, an expression leading to relaxation, and exhalation).38

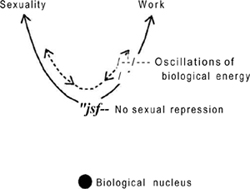

The orgasm coordinates intra-organism and inter-organism regulations in an intimate way (see figure 18.2). Orgasm becomes a particularly striking example of the form of reaction that mobilizes all these mechanisms. It creates a profound dynamic of the organism that allows for a deep cleaning of the tissues and fluids, a discharge of emotional tension, and a form of contact with the other that is necessary for someone to be able to let go. Only when two individuals have an orgasm together does such a powerful discharge become possible.39 In other words, the orgasm is not just a pleasurable reflex unleashed by a few nerve centers. It is a profound need that allows an organism to renew itself. In this sense, for Reich, “sexual stasis represents a fundamental disturbance of biological pulsation” (Reich, 1948c, V.l, p. 153f). Having arrived at this stage of his thinking, he has a model in hand that answers all the questions he had asked himself with regard to the orgasm when he was still a student. This model made it possible for the subsequent generations to ask other questions that necessitated other models in the future.

FIGURE 18.2. The circulation of energy during orgasm. There would be one pulsation that integrates the two organisms. Source: Reich (1951, p. 80).

Reich asked his patients to move like a jellyfish but had not, it seems, made of this proposition a structured exercise. It was, for him, more of an astute teaching tool. Judyth O. Weaver told me that most orgonomists in the United States do not know this exercise.40 It would seem that it was Ola Rakes who started to develop this exercise in Oslo after visiting Reich at his property in Maine. Gerda Boyesen and her students then created an entire series of exercises based on this proposition (Heller, 2007).

JELLYFISH EXERCISES AND AUTO-REGULATION

The jellyfish exercises41 show how choreographer Rudolf Laban, through the intermediary of Elsa Lindenberg, influenced Reich’s bodywork. Laban distinguished two basic movements of the body: “It has been found that bodily attitudes during movement are determined by main action forms. One of these forms goes from the periphery outwards into space, while the other comes from the periphery of the kinesphere inwards towards the center” (Laban, 1950, IV, p. 83). The analysis of this basic movement by Laban is certainly more refined that that of Reich’s. He differentiates a global pulsatory movement from a more dynamic differentiated pulsation of body parts: a hand may contract while the other opens up. Laban sometimes uses global pulsatory movements, but he does not understand these two general movements as being healthier than a dynamic play of tensions between parts of the body. A tensing of one part can serve as a basis to accentuate the opening of another part of the body as when a compressed spring suddenly lets go. He distinguishes between the forms of harmonious dances that impose a global expansion or a contraction on the body and the other forms of dance that exploit a multitude of contractions and expansions in different parts. For Laban, the adoption of either of these is mostly an option between styles and cultures.42 He refers to every blend of parts of the body in extension and in contraction as “arabesque” and global movements as “attitudes”:

Attitudes show a relationship to all dimensions: high, deep, right, left, forward and backwards. It is as if all the space were raised into one comprehensive dimension giving a similar aesthetic impression to that of an orchid whose intertwining curves create a perfect unity. Attitudes are final poses which cannot well be further developed. (Laban, 1950, IV, p. 86)

Every combination of the parts of the body in extension and in contraction creates a kind of symbolization that would always be, according to Laban, that which creates the necessity to develop the art of movement, like dance:

Experience of the symbolic content and its significance must be left to the immediate comprehension of the person who watches the movement. Any verbal interpretation of this inner feeling will always be something like a translation of poetry into prose and will remain all the while unsatisfying. (Laban, 1950, IV, p. 86)

To explore the impact of orgone on the organism, Reich worked with global body movements that can help the patient become aware of the deeper dynamics of his being. He focused on the activation of a harmonious and global pulsation. He did not take the time to observe the different types of pulsations that can be generated by the different organismic dimensions. An organ does not necessarily pulsate like a tissue, a fluid, a muscle, and so on. Reich does not explore the dynamics that emerge from the dynamic resonance between Laban’s “arabesques.” Elsa Lindenberg, who was probably an expert in contrasting arabesques, did not want to wait. I assume that her need to mix dance techniques, such as Laban’s arabesques, and Vegetotherapy was one of the reasons that encouraged her to create, at the end of her life, a school of dance therapy.

Introduction to the Jellyfish Exercises. Here is a simple exercise that permits the introduction of the basic principles of Reich’s jellyfish exercises.

Vignette on orgone sensation. You relax, eyes closed, sitting on your ischia bones, back straight. You are aware of how you breathe. You then rub the palms of your hands together rapidly from top to bottom for a few minutes. You slowly separate your hands apart not more than an inch, keeping them parallel, one palm facing the other.

At that moment, most everyone with whom I conduct this exercise senses a dense field between their hands. They have the impression that this field has a rhythmic pulse that subtly pushes the hands apart and draws them to each other. It is recommended to verify that the respiration in not inhibited while the patient is concentrating on the field between their hands.

The foregoing is a typical Reichian exercise. I practiced it with several body therapists, including Eva Reich in Geneva. A Reichian explains that this field that you feel between your hands is orgone energy and that the pulse is one of the properties of this energy. The impression that something pulsates between the hands is often reported. Typically, when I guide others in this exercise, individuals also feel warmth and tinglingin their hands. These vegetative sensations sometimes sweeps over the body. An individual may feel a circulation in the body that gradually becomes an impression of global pulsation. These types of sensation are often associated to the circulation of the chi, of the orgone, or of “vital energy.” Whatever these mechanisms might be called, this experience is frequently observed and experienced as beneficial by individuals who are not afraid of pleasurable sensations that arise in the body. For example Hiroshi Nozaki taught the same exercise in his courses of Chinese massage, to make us feel the circulation of the chi.

Brief Description of the Main Jellyfish Exercise. This exercise is conducted while lying on one’s back. It consists in opening, as much as possible (hands and feet as far away from each other as possible), then closing oneself up as much as possible (knees and elbows as close as possible to the center of the thorax). In these exercises, the patient explores different ways of going from one extreme to the other, at different speeds, in a more or less coordinated fashion with respiration. It is easy to demonstrate that in these postures, it is impossible to be curled up and fully expanded at the same time.

Reich’s idea, at the time, was that the center of the orgastic reflex organized itself around the segment of the diaphragm. Genitals, mouth, and arms get close together in exhaling; they distance themselves somewhat with inhaling. This movement in pulsation is what organizes and coordinates the movements of the organism. The body passes alternatively from a C position to an X position.

When a jellyfish moves, both ends of the body get close to and far from one another, in a rhythmic movement, which can become clonic. Taking this movement as a metaphor, we arrive at the following hypothesis:

The expressive movements in the orgasm reflex are, viewed in terms of identity of function, the same as those of a living and swimming jellyfish. In both cases, the end of the body, i.e., the ends of the trunk move towards one another in a rhythmic motion, as if they wanted to touch one another. When they are close together, we have the condition of contraction. When they are as far apart as they can be, we have the condition of expansion or relaxation of the orgonotic system. It is a very primitive form of biological pulsation. If this pulsation is accelerated, if it takes on a clonic form, we have the expressive movement of the orgastic convulsion. (Reich, 1949a, XIV.4, p. 396f)

The movements of the jellyfish exercise are carried out by the patient. The therapist intervenes very little, for this work aims at developing the capacity of the patient to auto-regulate. The therapist is content to help the patient learn the movements, then to talk with him about how the segments of the body coordinate themselves and what was experienced. Therefore the patient moves himself, coordinates his gestures with his breathing. The difficulties of coordination are perceived by the patient and the therapist simultaneously. We always find in body exercises the fact that the therapist sees things that the patient cannot see. Thus, the therapist often observes with greater precision the synchrony between gestures and breathing, but he cannot perceive the patient’s experience. Patient and therapist each perceive different aspects of the global experience. This technique allows a form a co-construction process, during which what was perceived by each person allows them to create a global vision of the patient’s nonconscious and conscious dimensions that were activated in the patient’s organism during the jellyfish exercise. Among the Reichians, this co-construction necessitates a straight-talking style. The patient learns to tell the therapist when he has the impression that the therapist has a false view of what is going on within him. The patient also learns to manage similar remarks by the therapist without automatically accepting them. Typically, during these exercises, the Reichian therapist does not interpret. He is content to communicate what he perceives to the patient and asks the patient to do the same. It then becomes possible to ask oneself what sometimes causes a different perception of the same phenomenon.

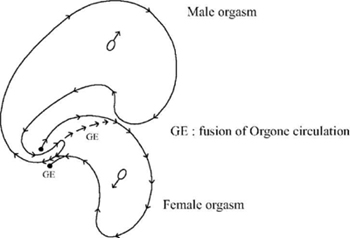

An Example of the Analysis of the Muscular Chains with the Jellyfish. Here is an example that shows how the jellyfish exercises makes it possible to test the function of the muscular chain that links the back of the cranium to the heels. It consists in oscillating in a continuous fashion between the two extremes (positions A and C):

A. Point of departure. The individual is lying on his back. The legs are folded, the hands are placed on the knees, the knees are as close to the thorax as possible while keeping the arms and hands relaxed.

B. Dynamic phase I. The knees gradually distance themselves as far as possible from the thorax, the hands and arms remain relaxed and are carried by the movements of the legs.

C. The point of arrival. The basic posture is identical (on the back, legs folded, hands on the knees), but this time, the knees are vertical above the pelvis, the hands are on the knees, hands and arms are relaxed.

D. Dynamic phase II. The knees gradually approach the thorax. The hands and the arms are relaxed. They are carried by the movements of the legs.

During the whole exercise knees and feet never touch (see figure 18.3).

To regulate the rhythm of the movement, you may ask the patient what he experiences when his knees approach the thorax during exhalation and when he moves away during inhalation. Or you can ask him to perform this gesture very slowly. Relaxation is the mood that is hoped for.

If the muscles of the back are relaxed, each time the knees approach the thorax, the nape of the neck hollows out a bit, and the head tips slightly backward. This movement is subtle. It is passive. It is activated by the lengthening of the muscles on each side of the spinal column and the muscles that link the lower back to the knees. Each time the knees move away from the thorax, the stretching of the back muscles diminishes; the nape of the neck lengthens as it relaxes. If the individual is not relaxed, provide him with a mental exercise (for example, ask him to think of a pleasant vacation) so that the attention does not interrupt the mechanical activation of the motoric chain.

The basic lever of this mobilization is the rocking of the pelvis toward the front and toward the back. If this head-pelvis coordination does not occur, the therapist knows that there is an important tension to be discovered in the back. He may either identify its localization by palpating the muscles or by exploring with the patient what is happening when the patient, tries to feel the coordination between the head and pelvis at the level of the nape of the neck.

A large part of the psychodynamic thought used by psychotherapists of Reichian inspiration takes up, from a particular psychoanalytic trend, the neurosis-psychosis dichotomy in association with the strong ego-weak ego dichotomy.43 For these Reichian therapists, the mental defense system that is constructed in creating a muscular armor is associated with a strong ego. When the armor becomes too rigid, it associates itself to diverse forms of neuroses. At the other extreme—that of the psychoses—Reich and his students speak of a weak ego, which relates to a defense system that does not include the muscular system in its defense strategy. They are thus like Socrates’s soul: particularly fragile oysters without shells.

FIGURE 18.3. Sketch of the exercise. Source: Heller (1994).

This polarity was established by Reich basing himself on a series of sessions that he had with a female schizophrenic patient. He noticed that she hardly breathed, even though “her chest appeared soft, not rigid as in the case of compulsion neurosis” (Reich, 1949a, XV.l, p. 406). The respiratory inhibition is therefore not due to a muscular block. Everything happens as if she must continuously inhibit her breathing to control the intensity of her feelings. One of the rare islands of muscular defense (rigidity) that she had was situated in the ocular segment.44

Characters that Reich situates midway between neurosis and psychosis have an intermediary configuration. Thus, for certain “the rigidity is paired with flabbiness (hypotonus) of the other muscles areas” (Reich, 1949a, XIII.9, p. 341). These patients, similar to Kernberg’s (1984) and Kohut’s (1971) narcissistic personalities, have—in my experience—a tendency to fight to preserve, as much as possible, a sensitivity in contact with the deep movements of the organism. Their dilemma is that they can only construct themselves by inhibiting these deep sensations, and this they refuse. A Reichian would say that they have not found a way to pulsate between deep introspection and active contact with others. The transition phases are underdeveloped. They have a muscular armor that is only partially built; it is so full of holes that, in these cases, Reich speaks of “small islets of armor.” Some artists who cannot live without destroying themselves (for example, often having recourse to alcohol and other drugs) are often part of this population. Their dilemma is to feel so much and be able to contain so little.

To summarize, the distinction between hyper- and hypoarmored personalities brings together the following traits:

If this distinction is a bit simplistic, it remains useful. For example, in a recent study, Berit Bunkan (2003, p. 51) observed that most psychotic patients can have strong chronic muscular tensions in the back, which is compatible with the notion that psychotics can have “islets” of tension. She also observed, like Reich, that psychotic patients modify their respiratory behavior with difficulty. This analysis of psychotic patients forced Reich to change the initial position he developed when he created Character analysis and in Vegetotherapy, which assumed that a healthy individual would be without defenses. This is perhaps true for yogis, but not for an ordinary citizen.

This change of direction in the Reichian theory brings us back to Otto Fenichel’s (1935) notion that the defenses are not necessarily the sign of a pathology. Individuals could not function without a defense system. What Freud designated with his model of defenses in 1900 is today associated with the idea that the defenses often designate ways of structuring the psyche and its relationship with the rest of the organism. As Darwinism suggests, it is improbable that these organizational systems be truly coherent, and in certain cases, it is possible that they adopt a kind of functioning that does not enhance an individual’s chances of survival.

Vitality is a theme found here and there in the literature, but it has not yet been explored in a systematic way. We already encountered it in Descartes, when in his fifties and dying, he composed the Treatise on the Passions in 1649. We find this theme developed with an even greater passion by Reich as he approached his fifties and his death. In 2010, Daniel N. Stern undertakes this theme anew. It would seem that it takes a mature person to appreciate the importance of vitality. Probably only when it begins to diminish does the mind grasp its importance.

For Stern, the vitality is regulated in the brainstem, which can actively integrate information on metabolic dynamics. In the Reichian theory, metabolism has an active and powerful impact on the brain and mind. The brainstem is only a cog in the dynamics that coordinate mind and metabolism. The interaction established between respiration, blood circulation, and the brain influences the vitality of all brain cells.47 The interaction between body and brain, and between gesture and thoughts, shape the activity of the brain, respiration, and circulation of the blood. The brain is influenced at least as much as it influences.

However, Daniel Stern describes in a particularly fine manner the impact of vitality on the mind and the necessity of integrating this organismic force in the theory and technique of psychotherapy. He also makes it possible for the contemporary body psychotherapist to discover the neurological mechanisms that shape the dynamics of vitality. For example, he shows that an experience, whether it is perceived by oneself or by another, has a “contour of vitality” that is a sort of gestalt (Stern, 2010, p. 4f). This activity coordinates gestures, thoughts, affects, and behavior around an energetic dynamic that can become more or less conscious. This remains true while we attend a dance event or when we interact with someone. The contour of vitality is also one of the forces that coordinate organisms.

The period after Wilhelm Reich’s death was problematic for many reasons that are mostly linked to ideological and political issues. Reich had beliefs that were difficult to accept: on Martians and simplistic machines that would control the circulation of cosmic energy. He claimed that he often saw flying saucers. These perceptions were, for Reich, so tangible that he wanted his son to help him save the world by fighting against a Martian invasion.48 There are so many books on this subject49 that I need not make any further comments at on this subject. Reich acquired the reputation of a mad hallucinating genius. I content myself to underscore the connections between Reichian theory and Idealism because, it seems to me, this is what the Reichian of today needs to understand. At that time, Reich often used one of Socrates’s favorite rhetorical techniques: playing the innocent.50 It consists in feigning to know nothing, to be like an alien who discovers the human species and seeks to know if it consists of civilized people. This strategy presupposes that humanity ought to be coherent and rational and that each irrational trait merits an ironic comment or even a condemnation. Again, it is striking to notice how Reich uses this caustic tool like a virtuoso without ever using it to critique himself. Socrates at least tried to look as if he were critiquing himself.

It is too easy to throw all of Reich into the garbage just because we do not like Idealists, or an author who has psychiatric symptoms, as Pascal Bruckner and Alain Finkielkraut (1979) proposed. We would lose too much time having to reinvent some indispensable tools for the psychotherapy of tomorrow. Having said this, to disentangle Reich’s Idealism from his therapeutic work is still an unfinished task, fifty years after his death.51 As I had indicated with regard to Plato, Idealism corresponds so well to the comfort needs of consciousness that it is difficult to let it go.

Even though Socrates and Reich do not resemble each other, their trials have some common characteristics. In both cases, they have the impression of being innocent victims of the stupidity of their co-citizens. In both cases, the justice that condemns them is experienced as arbitrary; nothing seems to justify the violence of the legal punishment that they suffered for their offense. Even if their theories were entirely delusional (which is not the case), nothing justifies a death sentence in one case and two years of imprisonment in the other. It was subsequently forbidden for citizens of the United States to own a publication on orgone, written by Reich or his pupils. Law enforcement agencies conducted searches of particular individuals; books that were found were burned in a public place. These persecutions were still going on after the election of John F. Kennedy as president of the United States. I do not advance any explanations on the incredible severity of this repression, and I do not know of any satisfying analysis of the situation. Most of the analysis published by those close to and admirers of Reich defend an Idealistic scenario similar to that used by the pupils of Socrates: the idiots have persecuted a great genius because they could not cope with the luminous truth that he was bringing to the people.52

We had to wait until the Italian publisher Giangiacomo Feltrinelli53 dared to publish one of Reich’s works in 1963 and the rising of youth movements in 1966 in Berkeley and May 1968 in Paris for Reich’s work to become available in Europe once again. In that context, it was difficult to have a rational discussion relative to his legacy. His work was taken up every which way by all kinds of people for reasons that had nothing to do with Reich’s real career.

In this, we find one of the principal symptoms of Idealist movements already discussed with regard to Socrates and his disciples: an inseparable connection between scientific reasoning, political Utopia, sexual politics, power over others, and self-exploration. In both cases, it is not appropriate to speak of sects, but surely of Idealism. This inseparable connection is difficult to grasp and master when we do not have a clear understanding of Idealism.54

Locked up in prison, Reich was terrified to see the advent of movements that exploited his status as a martyr to the advantage of goals he did not approve. Some ascribed to him the idea that giving birth was an orgasm and that parents ought to initiate their children to sexuality by making love in front of them. The notion that a healthy birth is necessarily orgastic is attributed by Reich to Paul and Jean Ritter (1975) in letters addressed to Neill (e.g., March 3 and 8, 1956). In his letter to Neill of March 8, 1956, he associates the name of David Boadella. Boadella was trained by Paul Ritter and then collaborated with him. For Reich, Ritter’s group was part of extreme left movements who used Reich’s name to hide “their ignorance and their quackery.” The “Ritter and Company” so upset Reich in the last weeks of his life that he almost ended his deep friendship with Neill, who supported them (letter from Neill to Reich, October 1, 1956). Given the importance of Boadella in the neo-Reichian movement, it is perhaps useful to recall that Reich could easily exclude individuals who admired him (e.g., Otto Fenichel) and that Neill supported Boadella, knowing all the while what Reich thought about him. It remains true that Boadella developed a personal view of Reich’s thought.

Others made use of the notion of sexual revolution to promote various forms of prostitution. At the end of his life, Reich wanted to disassociate his name explicitly from the insults made against women and their pain in childbirth,55 from the practices of pedophile parents, and from the pornographic sexual industry conducted by various forms of Mafia organizations.

It is now time to take up Reich’s work in such a way as to define the Idealistic components of it.

The Idealistic properties of the orgone are as follows.

Although Reich argues against the idea of the state that follows from Plato’s theory, their theories share many similarities.59

Reich had hoped that scientists like Albert Einstein would have replicated his research; at the same time, he thought that these replications could not be undertaken by anyone other than individuals who accepted the theory of the orgone.60 Yet it is exactly when individuals want to contradict the results of experimental research that a scientific debate can sometimes lead to confirmations that render a model even more robust.61

Reich and Plato have the same difficulty as most of the religions influenced by Idealism: the explanation of evil. How can a universe made by omnipotent beneficent forces give birth to evil? With Reich, there would be a structuring of political power that intends to concentrate power in the hands of a few. These forces would have created an “emotional plague” (Reich, 1949a, III.XVI; 1946, XIII. 1), which weakens the natural links between consciousness and the depths of the organism by inhibiting sexuality. According to Reich, this inner division is at the origin of all illnesses (cancer, neurosis, psychosis, and so on), human malice, and misery.62 He fought violently against any attempt to associate his orgone to spiritual movements. For him, spirituality and the religions are based on a false perception of the orgone, which engenders emotional plague.

With this way of seeing things, Reich created a feeling of estrangement between himself and others, between the armored “little men”63 and those who are in contact with their orgone. This may explain why he was unable to engage in a constructive discussion with the great men whom he tried to contact, like Freud and Einstein. Even in these instances, he only wanted them to approve of his endeavors. Reducing most citizens to the category of little men is not so different from the way Plato had to disqualify his colleagues by referring to them as “sophists.” In Plato’s Dialogues, Socrates listens to the other only to impose his own point of view, his own way of formulating a problem.64

Socrates and Reich both went to prison mostly because, during their trials, they believed themselves more intelligent and more just than the court before which they stood. In both cases, the court did not have a severe judgment in store for them. Their final decision was provoked by the attitude of the accused. We have more information on the proceedings of Reich’s trial than that of Socrates. Reich was hounded because he sold or rented accumulators to patients to cure their illness (e.g., cancer). He was put in prison because he declared that he refused to present himself before a court of justice until scientists could have tested the soundness of his observations.65 He was finally condemned for contempt of court. Having said this, as for Socrates, the final judgment is particularly severe for an insult to the judicial system.

A striking example of Reich’s Idealism is revealed to us in a moving recording that he left for posterity on April 3, 1952, after a severe accident caused by his experiments on orgone and nuclear energy. Clearly depressed, Reich (1952b) gives witness to posterity that he is the only one to have grasped the actual situation and to be able to propose adequate solutions. He is desolate to be surrounded by incompetent persons (too neurotic) to understand, as he did, what was at stake. He is evidently the one through whom cosmic truth can express itself and incarnate itself in this world.

During this period Reich presents himself as a modern Socrates, innocent and pure.66 He pretends that the authorities are wrong to doubt his uprightness and his ethics, and that it is not because he advances sexual freedom that he sleeps with his female patients. In short, he is persecuted for his ideas and the truths they contain. If the argument and the plea are credible, it does not correspond to the reality. It is not certain that the flying saucers he contends to have seen really existed. It is probable that he was intolerant and that acting out with female patients or ex-patients had occurred on several occasions in his life (from 1920 to 1955). As with Jean-Jacques Rousseau and his theories on the education of children, there is clearly an abyss between what Reich advocates and how he lives. It is apparent in a form of negation or at least denial and also bad faith.67 Reich claims that only people who are able to have orgasms have a healthy mind and that he is an example of this truth. In fact, if he truly had orgasms, he was the living proof that his theory is false.

This brings us back to the basic position of this book with regard to Reich: we must take from his work what remains worthwhile and avoid personalizing the debate. The problem with the devotees of Reich is that they want to love and believe in what he claims to have loved and believed. Today, this is not a defensible position.

I have already presented Hermann von Helmholtz as one of the founders of experimental psychology and one of Freud’s references in neurology. He was, among other topics, an expert in the psychoneurology of vision. I summarize a lecture Helmholtz (1853) gave on Goethe’s theory of perception. This theory is still read today in milieus close to spiritual movements.68 Goethe considers his theory scientific. Helmholtz wants to show that Goethe’s text on perception is interesting but has nothing scientific in it. Helmholtz makes use of this discussion to indicate the characteristics of a scientific discourse on perception.

Science, according to Helmholtz, seeks methods that promote the observation of what is happening while having recourse to human perception as little as possible. Introspection is able to furnish complementary information to the objective observations, but it cannot provide the basis of scientific knowledge in psychology. The mechanisms the scientist attempts to isolate are active in the wings of the theater of life independently of what we think of them. As the marvelous poet that he is, Goethe constructs a theory of perception from what he consciously feels. Given his genius, the theory he proposes is full of fascinating intuitions, some of which are confirmed by scientific research; the whole remains a theory of what the poet perceives and not a scientific theory of perception.

This lecture could have been addressed to Reich, a century later. Parts of Reich’s work are relatively robust: those that are based on his experience in psychotherapy and sexual epidemiology, whose clinical validity has been confirmed by numerous colleagues since then. But, like Goethe, Reich too often bases his theory of the orgone on what he and his patients experience.

For Reich, what is perceived by an “unarmored” person must exist. He certainly spent large sums of money to buy sophisticated materials with the intent to scientifically analyze the orgone, but he did not have the means to undertake a reliable research on the subject. I have known many psychotherapists who have attempted to combine clinical and experimental research. Their work, often imaginative, can inspire but never allows for drawing a solid conclusion. Given a psychotherapist’s education and training, he can collaborate with research teams, but he wastes his time and that of others when he undertakes research by himself. Reich confirms this analysis.