Classical psychotherapy preoccupies itself with the psychological functions, that is, with the ways a person perceives and experiences what is happening. The first psychotherapeutic approaches, like Freudian psychoanalysis and Jungian analysis, mostly used two approaches to access the patient’s psyche:

A first characterization of body psychotherapy is to include in this category all forms of psychotherapy that explicitly use body techniques to strengthen the developing dialogue between patient and psychotherapist about what is being experienced and perceived. In most schools of body psychotherapy, the body is considered a means of communication and exploration just as complex and rich as verbal communication: “The body is no longer experienced as an object of awareness but as an aspect of awareness” (Salveson, 1997, p. 35). It is often a shared understanding among the schools of body psychotherapy that language and body became increasingly complex within the same developmental process, and language is a subsystem of the organism’s capacity to communicate.1 Initially, the body psychotherapeutic approaches integrated two dimensions associated with the body:

More recently, certain body psychotherapists integrate a larger scope of body-related phenomena, like the analysis of nonverbal communication. These visible and spontaneous activities are situated at the intersection of social norms, behavior, the body, and habitual movements.2

Psychotherapy that systematically explores behavior is not referred to as body psychotherapy but as behavior therapy. The integration in psychotherapy of what the anthropologist Marcel Mauss (1934) called the “techniques of the body” characterizes the field of body psychotherapy. To create a model that integrates bodily and psychological dynamics, body psychotherapists found it necessary to modify classical theories, which had been developed to explain what happens in one of these two domains: “When we take into account the impact of body phenomena on relational dynamics, we quickly notice to what extent the current theoretical constructs relative to interaction need to be radically reformulated” (Rispoli, 1995; translated by Marcel Duclos). In this book, I elected to discuss that which essentially establishes the domain of body psychotherapy. There exist age-old practices and discussions that permit us to affirm that the body-mind approaches carry with them robust experience and robust3 expertise. Because scientific researchers have not yet studied this domain in a systematic way, we count mostly on phenomena that have often been observed over time in a great variety of cultural contexts. The relevance of integrating body techniques in psychotherapeutic approaches is supported by extensive clinical research and numerous collegial interactions. It is, above all, these robust models that merit learning by body psychotherapists in training and by those who would like to reflect on what these approaches are discovering and proposing.

The following section is a theoretical summary of the reference model used for this volume. Some may prefer to read the concrete examples in the chapters of this book and then read this section later.

While writing this book, I discovered that I could group most of the models I was describing in a system of the dimensions of the organism (SDO), or system of organismic dimensions. This systemic model claims a pedagogical status but not a scientific one. Its purpose is to allow a clinician to situate the types of interventions he might use in psychotherapy sessions and situate those used by colleagues. No single approach corresponds to the model of reference provided herein, but it allows a relatively accurate description of the different modes of intervention used in psychotherapy. This system of organismic dimensions is used to situate the various topics presented in this book with greater ease. I therefore describe this system in the following sections.

Galileo (1630) and Newton (1686) use the term body to designate any material object that can be perceived and weighted and has a clear contour. Thus, a star seen from far way, a stone, or a plant is a “body.” Mechanics is the science that attempts to describe and predict the behavior of inanimate bodies.

The term body was also used to designate animated entities. Any individual plant or animal is a body. For William James,4 the brain, hormones, and veins are parts of the human body. This meaning is still used today. For example, Antonio Damasio (1999) wrote a book with the subtitle Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. In this title, the term body designates all the physiological dynamics of an organism—the nervous system, hormones, muscles, and breathing—in an undifferentiated way. This remains the most familiar usage of the term body. Body psychotherapeutic approaches that use this vocabulary are sometimes called somatic psychotherapy.

This meaning of the term body is equivalent to the term organism used by most biologists. In seventeenth-century France, the term organism designated “a living being endowed with organs whose totality constitutes a living being.” The term organism thus replaced the term living body used by Lamarck. This French term entered the English language in the eighteenth century to designate “an individual animal, plant, or single-celled life form” (The New Oxford Dictionary of English, 1999, p. 1307). In this volume, I use the term organism to designate an individual system. For example, Darwin writes that “The relation of organism to organism . . . [is] the most important of all relations.”5

All the mechanisms contained in an organism participate in several regulatory systems. They may thus have several functions simultaneously. One of these functions may be to belong to a particular dense network that organizes itself around a particular adaptive function of the organism. The principal functions of adaptation form what I call the dimensions of the organism. There are no clear limits between one dimension and the other mechanisms of regulation of an organism, but it is useful for treatment to consider the dimensions like relatively well-differentiated subsystems. As the SDO is a systemic model, I first summarize certain general features of system theory.6

My main frame of reference is a systemic developmental theory,7 close to the genetic and constructivist structuralism of Jean Piaget (1967, 1985). As system theory can become complex, I focus on a few points that are often useful during psychotherapy sessions:

The functioning of a system is regulated by mechanisms that participate in the continuing interactions between the system and its subsystems. To the extent that in psychotherapy, the mechanisms observed are often too complex to be situated with precision, it is wise to analyze a mechanism following the advice of Jon Elster: “Roughly speaking, mechanisms are frequently occurring and easily recognizable causal patterns that are triggered under generally unknown conditions or with indeterminate conditions” (Elster, 1998, I.I.I, p. 1).

One of the fundamental ideas of system theory is that each entity is a system onto itself and systems are hierarchically organized. The molecule is a system made up of atoms that organize themselves in a particular fashion; the cell is a system composed of molecules that also organize themselves in a particular fashion. In a similar way, the organism is an organization of organs; a group is an organization of organisms in interactions.9 This hierarchical organization is known as the levels of organization of matter. Each subsystem follows a particular set of rules, even when they are included in the same system:

This implies that an organism consists of a heterogeneous set of mechanisms. The dimensions of an organism are open systems. Each subsystem has an internal cohesion in which it is grounded, but it also has roots that dig into the external regulators of its ecological environment. There is, for example, a set of mental procedures that allows one to think that 2 + 2 = 4,10 but at the same time this capacity is rooted in neurological and cultural (e.g., mathematics) dynamics. It is important to understand that the dynamics of a particular system typically has such multiple sources. This is well illustrated by the following quote on the meaning of gestures, written by anthropologist Edward Sapir:

Gestures are hard to classify and it is difficult to make a conscious separation between that in gesture which is of merely individual origin and that which is referable to the habits of the group as a whole. In spite of these difficulties of conscious analysis, we respond to gestures with an extreme alertness and, one might almost say, in accordance with an elaborate and secret code that is written nowhere, known by none, and understood by all. Like everything else in human conduct, gestures roots in the reactive necessities of the organism, but the laws of gestures, the unwritten code of gestured messages and responses, is the anonymous work of an elaborate social tradition. (Sapir, 1927, p. 556)

Similarly, on a more cognitive level, a thought is rooted in several environments. This flexibility is possible because there is not one coherent psyche; but instead, a multitude of heterogeneous mechanisms that can generate different ways of thinking. We will see in this volume that these multiple forms of psychic mechanisms root themselves differently in the diverse environments that shape their ecology. This explains why there are many different ways to perceive and to think, many different aspects to memory and consciousness, and so on. Thus, certain events stored in the hippocampus of the brain’s limbic system when we are young can be recalled, later on, in the temporal cortex when we are more than fifty years old.11

Classical materialism supposes that the properties of a system are the sum of the properties of the elements that it contains, whereas a system model postulates that an organization can have emerging properties, that is, properties that are not part of the elements contained in the system.12 Elements, organization, and emerging systems mutually influence one other. This dynamic often leads to expressions such as these: a system is structured by what it structures, or a system structures itself by structuring that which structures it. These expressions sometimes appear obscure to those who do not know system theory. It is my hope that by the end of the book these notions will have become easily understandable. These formulations point to the fact that subsystems allow an organism to auto-regulate and participate in the regulation of the systems that contain it (e.g., nature, culture).

One of the first psychologists to distinguish between the elements and the organization is soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky.13 He wanted to show that certain human faculties, such as intelligence, emerge from the combination of information processes produced by the brain and the languages taught in societies. To illustrate what he means by emergence, he reminds us what transpires when water arises from the association of oxygen and hydrogen. These atoms, alone, embolden flames. Once they are associated in an H2O molecule, their combination acquires a property that is not contained in either oxygen or hydrogen: that of being able to put out a fire, or to transform itself into steam if we were to put water in contact with a flame. This property emerged from the organization of the three atoms. The organization of matter is thus as important as its particles. In this example, we have identified three aspects of matter:

The adaptability of a living system is in its capacity to find connections with its environment that promotes its survival. According to Piaget,14 this adaptive capacity can follow two types of mechanisms:

A baby discovers that it can take a rubber ball and make it bounce by letting it fall. If he then assimilates a doll into the schema15 that he used with the ball, the baby risks being surprised by the fact that the doll does not bounce. He also risks making the discovery that he might be scolded if he uses the same schema with a glass because it will break. Therefore, the baby will accommodate the schema developed with the ball into three sensorimotor schemata: one for that which bounces, one for that which falls but does not bounce, and one for that which falls and breaks. This differentiation of the initial schema permits him to discover particular ways to use these three objects. The child might then discover that it is pleasant to sleep with a doll and drink delicious juice out of a glass. Accommodation is thus an adaptation by innovation, whereas assimilation allows a schema to stabilize and refine itself in becoming more particularized.

A way to define therapy is to present illnesses as an adaptation disorder that activates forms of assimilation that are destructive to the organism.16 An example that many travelers will recognize is that of the tourist who is traveling in an area where it is inadvisable to eat the local raw produce, because they do not have the antibodies the local population has developed. The desire to eat the wonderful salads that are presented is a form of destructive assimilation for their own organism. The accommodations activated by the appropriate vaccines would allow for the pleasure of eating salads without harm to the organism. Psychotherapy proposes analogous changes, but the targeted accommodations are not situated at the level of antibodies. Instead, they consist of activating the processes of mental and behavioral know-how that permit a process of social integration that is constructive for an individual organism.

Just as we walk without thinking, we think without thinking! We do not know how our muscles make us walk—nor do we know much about the agencies that do our mental work.

If we could really sense the working of our minds, we couldn’t act so often in accord with motives we don’t suspect. We wouldn’t have such varied and conflicting theories for psychology.

No doubt, a mind that wants to change itself could benefit from knowing how it works. But such knowledge might as easily encourage us to wreck ourselves—if we were to poke our clumsy fingers into the tricky circuits of the mind’s machinery. (Minsky,17 1985, The Society of Mind, 6.8. and 6.13, pp. 63 and 68)

Let us come back to the concept of the organism.18 Every individual biological system capable of reproduction is referred to by the term organism in biology. This term designates a plant or a particular animal as a total entity. The caterpillar is apparently a different system than the butterfly, but it is nonetheless the same creature. Certain fundamental properties, like the genetic code contained in the cells of the system, remain constant; and the dynamic profile of these changes is one of the characteristics of the species.

The concept of organism is ultimately stable in the biological disciplines, but its functioning remains difficult to study. The majority of biological studies achieve a description of the many small mechanisms that make up the general dynamics of an organism, but there is not yet an approach that describes the way they coordinate with each other, especially the physiological coordinations that include the phenomena of consciousness. This explains why so many body workers use energetic models, in somewhat of a metaphorical sense, to work with the large movements of the organism that are always present.19 Some practitioners succumb to the temptation, which is rampant in the human species, to believe that a metaphor is a real mechanism.

An organism is a system that has an identity, flexibility, and coherence:

Each one of these terms is relative:

The subsystems of an organism are called heteroclite to the extent that they do not all function the same way. The liver does not function like the lungs, the muscles, and the bones. They are subsystems of the same organism, but they are not constituted the same way, nor do they have the same cells (bones have more calcium than the liver), and they do not react the same way (the liver has a local action that influences numerous parts, whereas the musculature is active here and there throughout the organism). To understand how these heteroclite subsystems can function in a relatively complementary fashion to maintain the coherence of the system, we must postulate not only a hierarchy of subsystems but also an organization that regulates the coordination of these subsystems. In each case, there exist interfaces that permit one system to interact with another that functions differently. For example, in the brain there are receptors that are sensitive to the presence of neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine. The nervous system has interfaces that can activate a muscle, and others that are responsive to the activity of a muscle.

These systems are part of the regulatory mechanisms of the organism. Because there is no such thing as a “super” regulator of the organism (a regulator of regulators of the organism21), a moment arrives when an organism is regulated by the manner in which it interacts with its surroundings. That which an organism needs to receive from the exterior to regulate itself is also heteroclite (light, nourishment, affection, recognition, weather, etc.). The coherence of a system is therefore maintained by four groups of forces:

The organismic processes that generate various forms of awareness are inaccessible to self-exploration by introspection. Introspection is a central tool in psychotherapy because it consists in observing as explicitly as possible, and in a detailed manner, inner impressions: how we think, our body sensations, the feelings that animate us, the thinking that creates our beliefs, interior conflicts, the way we love and/or hate ourselves, and so on. The mechanisms of the organism that are inaccessible to consciousness are nonconscious.22 It is impossible for a human to grasp the functioning of the organism’s physiological mechanisms in which thoughts arise by introspection, or the system of social interactions in which an organism constitutes itself. Introspection cannot even allow a person to explore the structure of the psyche. Conscious thoughts can perceive certain effects of these dynamics, and are almost blind to the ways its perceptions are organized. A person consciously and explicitly perceives a mental phenomenon, but not that which structures it.

Psychology is defined as the “the scientific study of the human mind and its functions, especially those affecting behavior in a given context” (New English Oxford Dictionary, 1998, p. 1497). Europeans often use the term psyche to designate the object of psychology and stress the notion that representations are only part of the mind. This terminology is coherent, as it is the root of the term psychology. In English, the term psyche (or psychic) is avoided because it is often associated with magical powers. Mind is not an adequate term to designate what psychotherapists work with because it reduces the psyche to its computational modalities. The dictionary recommends the use of psychology as a noun to designate the object of psychology, as when one speaks of the psychology of a person. I sometimes follow this recommendation, but because this book is strongly influenced by European literature, I also use the term psyche as it is used by European psychologists and psychiatrists,23 which is as a way of designating all the mechanisms studied by psychologists. To summarize, psychic is too close to magical disciplines, and mind too close to artificial intelligence. These remarks do not intend to disqualify these disciplines but to defend a choice of words that is appropriate in psychotherapy.

With the current systems model, the difficulty for psychologists is that however easy it is to situate physiological systems in an organism, it is not so easy with regard to the mind or behaviors. Thoughts are inevitably part of the mechanisms of the organism’s regulation, but their relationship with the organization of the organs is vague. The only thing that can be affirmed is that psychological and behavioral dynamics are situated somewhere at the intersection between (a) the mechanisms of regulation of an organism, and (b) the mechanisms that regulate the interaction between several organisms. The organismic models in psychology are mostly interested in how the psyche participates in the dynamics of organisms.24

The system of organismic dimensions is a topographic model, designed to situate a set of phenomena. This type of model was notably proposed by Freud. In his first topographic model,25 he situates the conscious, the preconscious, and the unconscious and the defense mechanisms that regulate the flow of thoughts between these regions of the mind. In his second topographic model,26 Freud distinguishes the id, the ego, and the superego. These two reference models have remained useful, although the psychological mechanisms associated with these categories have evolved considerably, even in psychoanalysis, with regard to the development of clinical and experimental research (see, for example, Roussillon, 2007).

If Freud’s first topography was centered on the geography of the mind, the SDO is an attempt to furnish a diagram of the internal dynamics of the organism. With it, a practitioner can easily describe what happens when different forms of intervention are used in a psychotherapy process, which is often the case today; for example, when a psychiatrist uses a psychodynamic approach and prescribes antidepressants. This model can also facilitate communication between psychotherapists, especially when they want to describe their particular way of working with patients.

Every dimension of the human organism has:

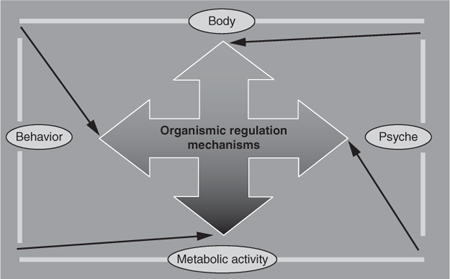

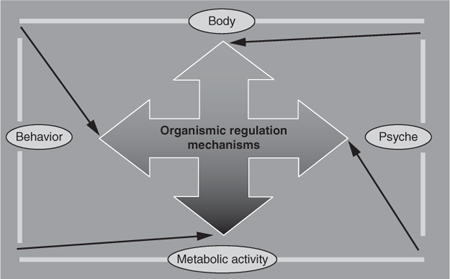

The organismic dimensions (metabolism, body, behavior, and the mind) are coordinated by organismic regulation mechanisms. The connections between dimensions (between the body and the mind, for example) are mostly indirect. The mobilization of the organism’s regulation mechanisms activates affects (moods, emotions, drives, addictions, etc.) in the conscious dynamics of the mind.

A dimension is thus a subsystem of the organism that support a certain form of global adaptive activity. Each one has a particular way to mobilize the organism’s regulatory mechanisms. Each dimension is approached by particular set of therapeutic disciplines. The dimensions of the organism distinguished in the system of organismic dimensions are the following:27

FIGURE I.1. The relations between the dimensions and the global regulation system of the organism. The global organismic regulation mechanisms connect the dimensions of the organism (metabolism, body, behavior, and psyche). They organize the communication between dimensions and are organized by these dimensions. The relations between dimensions are thus mainly indirect. Affective dynamics (instincts, drives, moods, emotions, etc.) are rooted in the organismic regulation system.

Let us now consider each dimension in more detail.

THE BODY

Body dynamics are mostly composed of mechanisms that permit the organism to adapt to the constraints of gravity. Gravity influences every aspect of an organism, but the organism contains a series of devices that are specialized in the management of gravity: the skeleton, the muscles and the sensorimotor nervous system. Figure 1.2 demonstrates a basic method taught by almost all the body centered approaches called the “plumb line.” It consists in taking a mason’s plumb line to evaluate the alignment of the body’s segments within the field of gravity when a person is standing up. By default, there is an expected alignment when the articulations of the ankle, the hips, and the shoulder are aligned with the ear. When this alignment cannot be easily maintained, at least one of the following problems is usually present:

BEHAVIOR

Behavior is generally discussed by behaviorists or in studies concerning nonverbal communication. It is the capacity to manipulate objects—sometimes with fine movements, as when one plays the violin—and to communicate with others. This occurs necessarily in the here-and-now, as behavior is an attempt to respond immediately to what is happening. Behavior mobilizes several mechanisms of the body, but its aims are different. Using identical mechanisms for several purposes can become problematic. It is well known, for example, that a profession that requires sitting for long hours can create muscular tensions that twist the spine and cause blood circulation problems.31 The objectives that behavioral demands impose on the body sometimes conflict with the needs of the body as defined in the disciplines like hatha yoga, gymnastics, and orthopedics.

In studies on nonverbal communication, the researchers analyze the postures, gestures, and facial expressions that permit two organisms to communicate and mutually influence one another. The behavior of one person has an automatic impact on the physiology of those who are around. The gesture of person A influences the senses of person B. The sensory system of B can subsequently activate physiological, affective, and cognitive mechanisms, as well as modes of automatic reactivity. Most of these activations unfold nonconsciously, outside of the conscious intentions of the interacting organisms. A person is able, for example, to drive a car while thinking of something else. His behavior is obviously guided by habits. The behaviorist often misunderstands the body of gymnasts, and the orthopedist does not always know how to understand interactive behaviors.

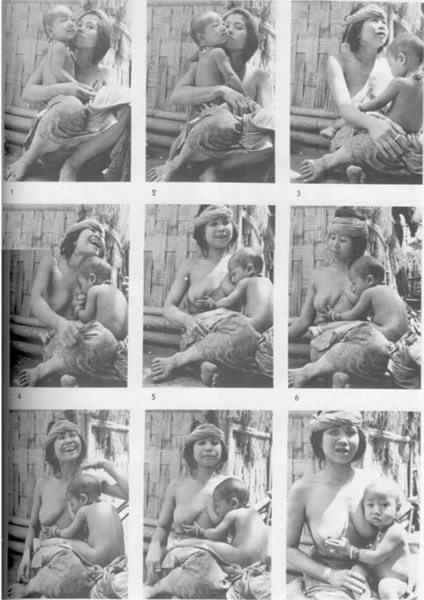

The photographic example in figure 1.3 was one of the points of departure for the study of nonverbal behavior during the 1950s. According to Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson, it demonstrates a typical automatic dynamic of the mother-child relationship in the traditional culture of Bali. We see in each subsequent frame how the mother goes from a stimulating and joyful expression to a negative or off-putting one. This alternating behavior organizes itself spontaneously when a mother interacts with her infant in this culture.

FIGURE I.3. An example of how a mother and an infant behave and interact in Bali (Bateson and Mead, 1947, plate 47, p. 149).

Metabolism regulation manages the energy of the organism at the level of the internal milieu and the cells. Metabolism also has importance in therapeutic practices, for example, when individuals handle an extra supply of oxygen poorly, as when their head turns as soon as they perform a breathing exercise, or when the metabolism of an anorexic patient adapts itself to the condition. Here we are at the heart of physiological auto-regulation.

THE PSYCHE

An important aspect of the psyche is to allow an organism to integrate itself into the dynamics of social institutions, thanks to its ability to manage tools and media. It can interact beyond the immediate here-and-now. Corrections are thus possible, as when one corrects a text. A reader cannot be aware of the many corrections made by the author of a book. Even if the mind has other important functions, this one distinguishes humans from other species. Neither art, nor law, nor economics, nor religion, nor science could exist without the human capacity to construct a body of knowledge that inscribes itself in a media accessible to all. This understanding is close to the concepts of present-day psychologists and sociologists, like Ed Tronick’s notion of co-construction, Philippe Rochat’s co-consciousness, Pierre Bourdieu’s analysis of distinction, or the coordinating function of the rituals described by Claude Lévi-Strauss.

This aspect of psychological dynamics has been explored in the past by psychologists at least since Vygotsky. Even if this definition of the mind still needs to be refined, it allows us to differentiate it from the other dimensions and to specify the therapeutic aims of psychotherapy. To ask someone to describe, using words or gestures, what one is aware of implies a clear distinction between behavioral expressive dynamics and psychological impressions. One can then distinguish in a more explicit way (a) problems in thinking, (b) problems in expression, and (c) problematic connections between thoughts and behavior.

It is difficult to demonstrate that the interpersonal regulatory system of humans is more evolved than that of monkeys (Waal, 1998, 2002). We could not easily show, for example, that the relationship between parents and infants are more developed among the citizens of Geneva than among chimpanzees in the wild. For example, I doubt that abusive parents are as numerous in a tribe of chimpanzees as they are in human families. On the other hand, the difference between the two species becomes intuitively obvious when we observe how mind and institutional organizations interact (Boyd and Richerson, 1996, 2005; Moessinger, 2008). To study the interaction between socially constructed beliefs and individual minds, it is also useful to distinguish between (a) the psychological means used by the organism to integrate itself in a social network (intelligence, imagination, etc.), and (b) the socially constructed ways of helping (or forcing) the organism of a citizen to integrate itself in an institutional environment. This relative differentiation between psychological mechanisms (representations, reasoning, perception, etc.) and social mechanisms (tools, rituals, etc.) explains the human capacity to exist in a great variety of cultural environments.

The organism can become relatively independent from the constraints imposed by the here and now when it uses its psychological capacity to use tools, which is not the case when it uses its behavioral resources. When I read a passage written by Homer, I have the impression that his thoughts meet mine, even though he has been dead for more than 2,000 years. The communication strategies used by a society to facilitate the inclusion of citizens in institutional dynamics influences the manner in which the mechanisms of the mind develop. Alfred Russel Wallace32 describes the case of the girl he adopted who was born in a jungle. In London, she became a renowned classical pianist. For Wallace, it was evident the psychological and behavioral skills that made it possible for this girl to become a pianist would never have developed in the jungle. Her original environment would have mobilized other capacities. In other words, an organism can develop in different ways, which are all potentially available.

THE REGULATORY MECHANISMS OF THE ORGANISM

To interact with each other, the dimensions need to interact with the mechanisms that connect them: the organismic regulation systems (see fig. 1.1). The activity of these organismic mechanisms is often partially perceived as an affect (mood, emotion, drive, addiction, internal atmosphere, etc.) by consciousness. Because the organismic mechanisms of regulation function as a system, they are equally influenced by what occurs in each subsystem—that is, in the dimensions. Here are examples of the most important organismic regulation systems:

The homeostatic mechanisms prolong the metabolic dynamics by mobilizing the resources of the organism to regulate the vital variables of the extracellular fluids. These are already complex organismic mechanisms because they coordinate metabolic dynamics with the other dimensions and guide the interaction between the organism and its environment. A typical example is that of the construction of houses, clothing, and the heating systems used to maintain the body’s metabolic temperature at around 36°C.

The activity of a dimension of the organism requires the support of the organismic regulation and of other dimensions to be able to accomplish its tasks. A thought needs the logistic support of the nervous system and a supply of oxygen delivered through the bloodstream. The more important the recruiting of the organism’s logistic support becomes, the more the activity of a dimension becomes organismic. A nervous movement of the foot necessarily recruits all the resources of the organism, but in a peripheral way. When a soccer player kicks a ball with his eye on the goal guarded by the other team, the movement of the foot mobilizes the other organismic dimensions in a much more important fashion.

The way I use the notion of dimension may seem strange to some readers, but it has an equivalent in engineers who build computers. They aptly identify two dimensions in a computer when they speak of hardware (the electromechanical functioning of the computer) and the software (a series of operations written in the program that manages particular information in circulation within the circuits). These two dimensions are found in the functioning of almost every part of the computer.

Yet the activity of the electric circuits is not directly organized by a program, because the rapport between the program (thought) and the electric circuits (activities of the central nervous system) is managed by the architecture (or design) of the computer: that which corresponds (in this metaphor) to the organismic regulations. When engineers conceptualize a computer, they decide in advance how circuits and programs will interact. These a priori decisions determine the architecture of the computer. The architecture coordinates not only the circuits and the programs but also their way of interacting with diverse interfaces like a screen, a hard disk, or a printer. All these elements are heteroclites and have certain independence. For example, a computer’s memory and its screen function differently. A similar memory can be associated with a great diversity of screens and hard disks. A typical expression used to describe this type of system is to say that it is modular. Every individual part of a computer functions in a relatively independent manner, all the while making it possible to fulfill functions that allow the system to work as a whole. Many people can buy the same computer but use different programs; or they can use identical programs (a word processing program) to achieve different tasks (write a book or organize email). Nevertheless, architecture imposes constraints. It can be connected to a great variety of screens, but not all of them. It can operate a great number of programs, but not all of them.

In the case of a malfunction, certain mechanisms of the computer can be affected and others not:

These three cases can be related to one computer, but the mechanisms involved and the solutions are almost independent of one another. Some cases are more complex. One then needs to understand how these dimensions interact with each other (for example, when engineers design a computer). An interesting aspect for the psychophysiology of perception is the way that computer engineers take to transform information managed by electric circuits into information that a user can understand (by reading what appears on the screen) or activate (by hitting letters on the keyboard). This transformation, this reformatting of information, is notably possible because identical electrical information is transformed by several layers of programming languages. The routines that register the “e” that I hit on my keyboard are not the same that produce an “e” on my screen.

In the SDO, the program corresponds to the mind, the parts that make up the computer to my physiology, and the design to the organism.

The psychological dimension can be divided into three principal layers that can each be broken down into a multitude of subsystems or modules:

These different layers (psychological, editing devices, neurological management of information), often referred to in neuropsychology, are all part of the organism’s systems of regulation. We can see that the further away we are from the dynamics of the brain to get closer to the virtual world that we perceive consciously, the more we can speak of the psychological dimension. We also see, in this analysis, how it is impossible to define a precise border between one dimension and the global regulatory mechanism of the organism.

I will present theories that can support discussions on the coordination between the mind and the organism from diverse points of view—all of them instructive and representative of the human imagination in this domain. None of these models uses the system of organismic dimensions. Yet all can be reread, in large part, with this model in mind to create an ensemble of views useful to a psychotherapist and even an experimental psychologist. In other words, this system is sufficiently flexible to be used by different approaches: all the while creating a common language permitting different schools to communicate with each other. A key term to describe the aspects of the organism that are explored in psychotherapy is the word practice.35 A practice has two dimensions:

To differentiate different practices, it is useful to distinguish between identical behaviors (to lift a glass) that mobilize different underlying mechanisms and identical underlying mechanisms that can generate different behaviors. A body psychotherapist works with physiological, bodily, behavioral, and mental practices and with practices that coordinate each dimension in a certain way. A practice is, by definition, a habit, a propensity, a tendency to act in a particular way. These practices activate without asking the individual’s permission. Often, the individual does not have the means to understand the implications of the practices that were acquired by his organism.36 Furthermore, to the extent that an individual’s thoughts are generally practices themselves, they do not always have to the capacity to evaluate a practice. These practices are not always beneficial to the individual or to one’s entourage. They construct and calibrate themselves depending on multiple factors so complex that even researchers are not able to account for the dynamics that favor certain practices, nor evaluate the advantages and dangers of a group of practices. That explains why it is so difficult to understand, evaluate and modify the practices that are perceived as detrimental or constructive by an individual and by those who know the person well. A psychotherapist’s central interest is the system of conscious psychological practices, but these are so intrinsically linked to other dimensions of the organism that it is often difficult to analyze mental practices without situating them in their organismic ecology. Such an approach to the mind is typical of body psychotherapies.

The complaints of our patients usually refer to their habitual ways of functioning: often depressed, anxious, angry, sad, afraid, and so on. By differentiating metabolism, body, behavior, and the mind, I define four ways to approach an individual that corresponds to four great originators of organismic practices that have an impact on the mechanisms that generate these symptomatic complaints. It is possible to associate many practices to each dimension. The general medical practitioner is evidently attentive to the metabolic phenomena above all else; the psychotherapist of an anorexic patient must also take into account how the patient’s organism has accommodated to a diet. The athletic coach cannot avoid taking into account the metabolic and psychological factors when he tries to develop a more sustained respiratory effort. In these three cases, the practitioner needs metaphors to support the motivations of a patient and establish a rapport of mutual confidence. Even when one focuses on mental practices, one needs to situate them in their organismic, multidimensional environment.

Psychotherapy is a form of therapeutic practice that is inspired from the sciences as much as is possible. It hopes to become at least as scientific as allopathic medicine some day. The influence of science manifests itself in two ways:

The second point interests me at this moment. It consists of giving a frame to the psychotherapist’s ethics in the face of what he presents as knowledge. The butcher guarantees wholesome meats that correspond to what is written on the label. The effectiveness of therapy is more difficult to evaluate, but the propositions of a method obey the same laws of ethics. The therapist is expected to propose a course of treatment that is relevant to a patient’s particular need for support. This ethical stance is based on the following basic principles: