10.4. Falkner-Skan Similarity Solutions of the Laminar Boundary-Layer Equations

The Blasius boundary-layer solution is one of a whole class of similarity solutions to the boundary-layer equations that were investigated by Falkner and Skan (1931). In particular, similarity solutions of (7.2), (10.9) and (10.10) are possible when Ue(x) = axn, and Rex = ax(n+1)/ν is sufficiently large so that the boundary-layer approximation is valid and any dependence on an initial velocity profile has been forgotten. In this case, the initial location x0 again disappears from the problem and a similarity solution may be sought in the form:

(10.34)

(10.34)

This is a direct extension of (10.19) to boundary-layer flow with a spatially varying free-stream speed Ue(x). Here, u/Ue = f′(η) as in the Blasius solution, but now the pressure gradient is non-trivial:

(10.35)

(10.35)

and the generic boundary-layer thickness is:

which increases in size when n < 1 and decreases in size when n > 1 as x increases. When n = 1, then δ(x) is constant. Substituting (10.34) and (10.35) into (10.9) allows it to be reduced to the similarity form:

(10.36)

(10.36)

where f is subject to the boundary conditions (10.28) and (10.29). The Blasius equation (10.27) is a special case of (10.36) for n = 0, that is, Ue(x) = U = constant.

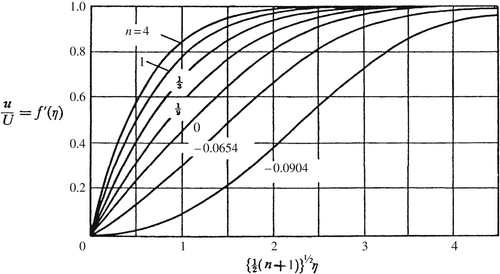

Solutions to (10.36) are displayed in Figure 5.9.1 of Batchelor (1967) and are reproduced here in Figure 10.8. They are parameterized by the power law exponent, n, which also sets the pressure gradient. The shapes of the various profiles can be understood by comparing them to the stream-wise velocity profiles obtained for flow between parallel plates when the upper plate moves with a positive horizontal velocity. They show a monotonically increasing shear stress [f″(0)] as n increases. When n is positive, the flow accelerates as it moves to higher x, the pressure gradient is favorable (dp/dx < 0), the wall shear stress is non-zero and positive, and (∂2u/∂y2)y=0 < 0. Thus, the profiles for n > 0 in Figure 10.8 are similar to the lower half of the profiles shown in Figures 9.4a or 9.4d. When n = 0, there is no flow acceleration or pressure gradient and (∂2u/∂y2)y=0 = 0. This case corresponds to Figure 9.4c. When n is negative, the flow decelerates as it moves downstream, the pressure gradient is adverse (dp/dx > 0), the wall shear stress may approach zero, and (∂2u/∂y2)y=0 > 0. Thus, the profiles for n < 0 in Figure 10.8 approach that shown in Figure 9.4b. For n = −0.0904, f″ (0) = 0, so τw = 0, and boundary-layer separation is imminent all along the surface. Solutions of (10.36) exist for n < −0.0904 but these solutions involve reverse flow, like that shown in Figure 9.4b, and do not necessarily represent boundary layers because the stream-wise velocity scaling in (10.6) used to reach (10.9), u ∼ U, is invalid when u = 0 away from the wall.

In many real flows, boundary or initial conditions prevent similarity solutions from being directly applicable. However, after a variety of empirical and analytical advances made in the middle of the twentieth century, useful approximate methods were found to predict the properties of laminar boundary layers. These approximate techniques are based on the von Karman boundary-layer integral equation, which is derived in the next section. Then, in Section 10.6, the Thwaites method for estimating the surface shear stress, the displacement thickness, and the momentum thickness for attached laminar boundary layers is presented. In the most general cases or when greater accuracy is required, the full set of equations for fluid motion must be solved numerically by procedures discussed Chapter 6.

Figure 10.8 Falkner-Skan profiles of stream-wise velocity in a laminar boundary layer when the external stream is Ue = axn. The horizontal axis is the scaled surface-normal coordinate. The various curves are labeled by their associated value of n. When n > 0, the free-stream speed increases with increasing x, and ∂2u/∂y2 is negative throughout the boundary layer. When n = 0 (the Blasius boundary layer), the free-stream speed is constant, and ∂2u/∂y2 = 0 at the wall and is negative throughout the boundary layer. When n < 0, the free-stream speed decreases with increasing x, and ∂2u/∂y2 is positive near the wall but negative higher up in the boundary layer so there is an inflection point in the stream-wise velocity profile at a finite distance from the surface. Reprinted with the permission of Cambridge University Press, from: G. K. Batchelor, An Introduction to Fluid Dynamics, 1st ed. (1967).