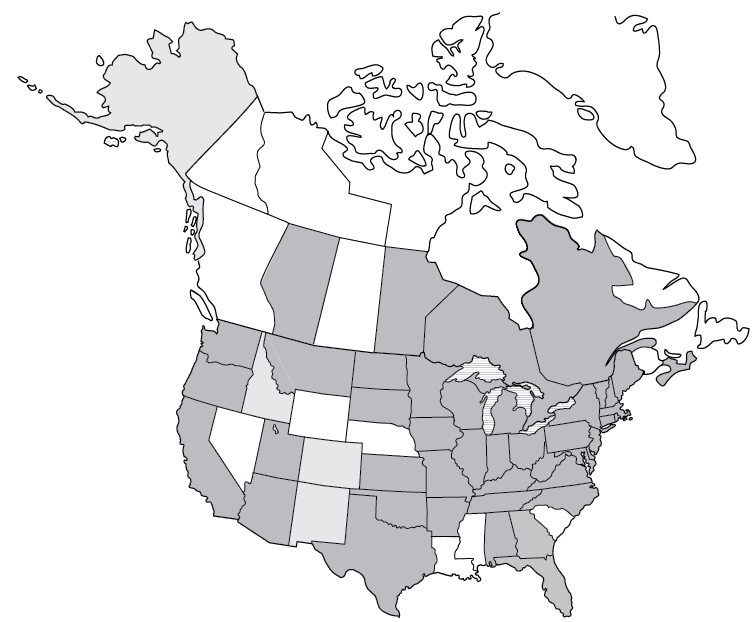

Lyme Disease reported cases

Lyme disease is the most commonly diagnosed and most familiar tick-borne disease. In addition to Lyme disease, ticks carry other pathogens that may be bacteria, protozoa, or viruses that can cause other diseases. In this chapter, we’ll discuss in detail the top tick-borne diseases diagnosed in North America. We will review each organism causing each disease and the time it takes to develop symptoms, as well as the symptoms caused by each disease.

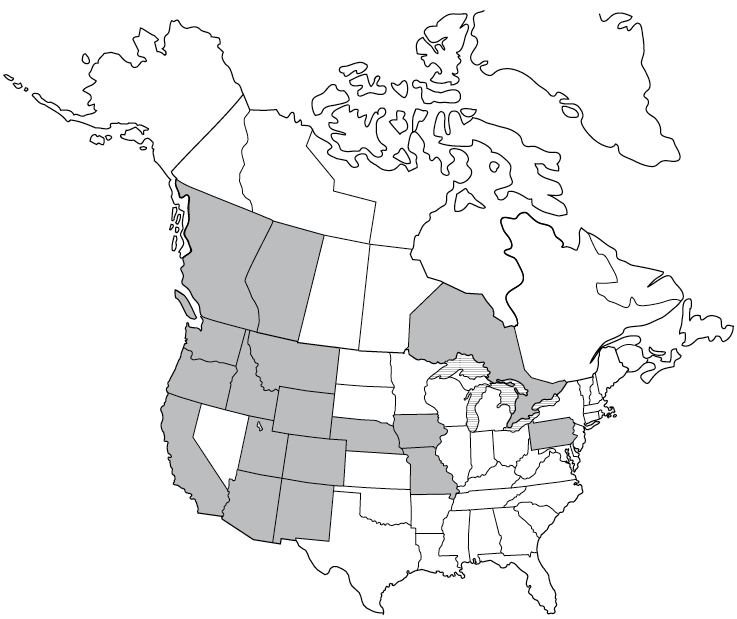

The discussion of each disease is accompanied by a map showing the areas in the US and Canada where it has been reported. There are a few things to keep in mind about these maps:

|

Disease |

Time Period |

Number of Reported Cases |

|---|---|---|

|

Lyme disease | 2017 | 42,743 |

|

Anaplasmosis | 2017 | 5,762 |

|

Babesiosis | 2015 | 2,074 |

|

Ehrlichiosis | 2017 | 1,642+ |

Rickettsiosis* | 2017 | 6,248 |

Tularemia | 2017 | 239 |

Powassan virus | 2009–2018 | 144 |

Heartland virus | Total as of Sept. 2018 | 40+ |

Tick-borne relapsing fever | 1990–2011 | 483 |

Colorado tick fever | 2002–2012 | 83 |

|

STARI | Unknown | Unknown |

|

Q fever† | 2017 | 193 |

|

Bartonellosis† | 2005–2013 | 12,000 per year9 |

|

Note: Many of these diseases are present in Canada but not reportable, so we lack statistics to cite. What we do know is that in 2017, there were 2,025 cases of Lyme disease reported to the Canadian government. *This figure includes Rickettsia rickettsii, R. parkeri, Pacific coast tick fever, and rickettsial pox (which is mite-borne) due to the inability to differentiate between spotted fever group Rickettsia species using serologic testing. †I include Q fever and bartonellosis in this chart because experts suspect that these diseases may be transmitted by ticks, but please note that at the moment there is no definitive evidence to support this hypothesis. |

||

Lyme disease is a preventable infectious disease that is transmitted through a tick bite, although fewer than half of people with Lyme disease actually recall a tick bite. Lyme disease, or Lyme borreliosis, is caused by a bacterium that has existed for millions of years. Lyme disease was discovered in Lyme, Connecticut, in 1975 by Dr. Alan Steere after a high number of children were diagnosed with what was thought to be juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. The bacterium itself was discovered in 1982 by entomologist Willy Burgdorfer and so was appropriately named Borrelia burgdorferi.

The term Borrelia burgdorferi is used in two different ways. There is the broad term Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (sensu lato means “in the broad sense”), which at the time of this writing includes 19 species of Borrelia. The more specific term B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (sensu stricto means “in the narrow sense”) refers specifically to the B. burgdorferi species. Of the 19 species in the sensu lato classification, four (to date) have been proven to cause Lyme disease: B. burgdorferi, B. mayonii, B. afzelii, and B. garinii. (Borrelia afzelii and B. garinii are currently found only in Europe but may arrive on this continent someday.) More Borrelia species are being discovered often.

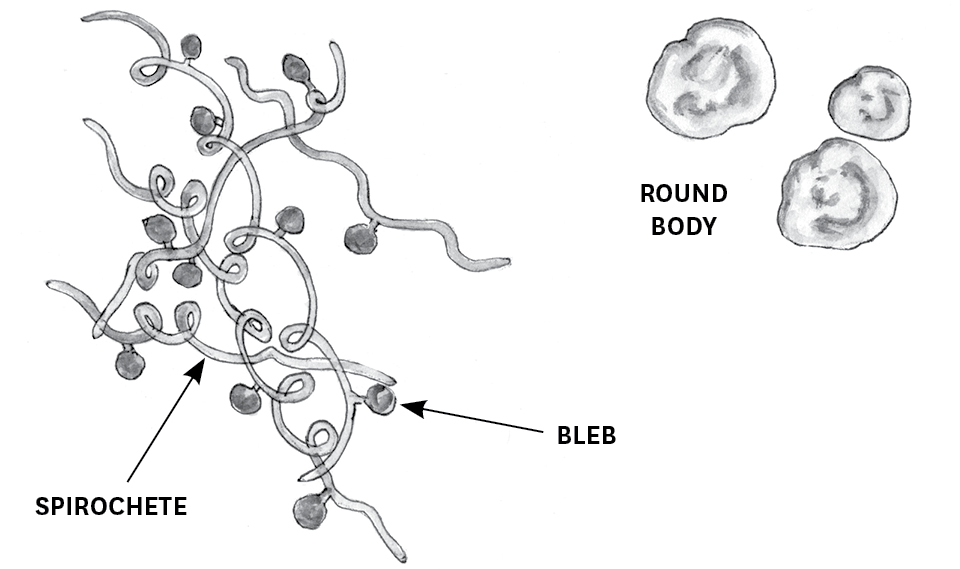

Traditionally, bacteria can be categorized according to whether they are gram-positive or gram-negative — that is, whether they hold a stain (Gram’s stain) in laboratory testing, which tells us about the structure of their cell wall. Borrelia is an atypical bacterium; it is neither gram-positive nor gram-negative. It is classified as a spirochete, meaning that is is helically shaped, like a corkscrew. Spirochetes are unique among bacteria for their arrangement of flagella (filament-like structures), which extend out through their cell membrane in a manner that allows them to move by rotating. The flagella give Borrelia excellent motility — which is especially helpful for moving through tissues in an infected host.

The relationship between Borrelia and a tick is symbiotic — both benefit. Ticks infected with Borrelia are more hydrated, which allows them to move more quickly, have longer life spans, take larger blood meals, and have larger fat stores. For its part, Borrelia requires a host to reproduce and does so through binary fission every 12 to 24 hours. It does not have the ability to make nucleotides, amino acids, fatty acids, or enzyme cofactors and therefore must live within a host to acquire those nutrients to survive.

The Borrelia bacterium has the unique ability to express a wide variety of lipoproteins on the surface of its outer membrane. These lipoproteins, or outer membrane surface proteins (Osp), express changes depending on where the bacterium is in the tick, whether the tick is attached to a host, whether the bacterium is transferred into a mammalian host, and what sort of response the mammalian host’s immune system has to the bacterium. Variability in these outer membrane surface proteins allows for more effective invasion of the host.

Inside the unfed tick, Borrelia lives in the midgut and its surface proteins express as what is known as type A (OspA). OspA has unique structures that allow the bacterium to survive in the tick’s midgut and bind to a receptor in the midgut lining that, for now, is generically known as TROSPA (tick receptor OspA).

When the tick attaches to a host and begins to feed, the temperature and pH in its midgut begin to change. These changes trigger Borrelia’s surface proteins to switch their expression from type A to type C. OspC does not bind to the tick’s midgut. Now the bacterium is released, begins to multiply, and moves into the tick’s salivary glands.

In the salivary glands, Borrelia biochemically analyzes the environment of the mammal host through the incoming blood meal and alters its genetic structure in order to prepare it for the new environment of its imminent host. A protein from the tick’s saliva (Salp15) binds to the OspC on the bacterium. Salp15 aids the bacterium’s transition from the tick to the mammalian host.

OspC protects the bacterium from the host’s immune response, which is to make antibodies to the bacterium. Salp15 interferes with the host immune system in various ways, including intervening in the host’s initial immune response to a pathogen like Borrelia. Borrelia burgdorferi itself has the ability to express many other surface proteins that can interact with the host immune system in order to resist annihilation.

Once B. burgdorferi is inside a mammal host, the host’s immune system interacts with the bacterium’s outer membrane surface proteins, which promptly rearrange themselves to help the bacterium resist annihilation. (As one set of researchers said, these surface proteins are “peerless immune evasion tools.”)10 With the immune system held in check, the bacterium moves through the host’s tissues, collecting nutrients along the way. It populates capillaries and veins, and its surface proteins bind with human proteins involved in wound healing and blood clotting, assembly of connective tissue, production of cartilage, and communication between cell membranes and the extracellular matrix.11 Borrelia penetrates connective tissue and invades synovial, neuronal, and glial cells. (Synovial cells line the joints and secrete synovial fluid that lubricates the joint cartilage; cartilage creates collagen, a protein that serves as food for the Borrelia bacterium. Neuronal cells are brain cells, while glial cells function as the connective tissue of the brain.) In this way, B. burgdorferi can invade the joints, brain, and heart, with wide-reaching effects on human health.

In the human body, B. burgdorferi is persistent and resilient in part due to the way the bacterium can change from the spirochete form to other forms. To begin, blebs — small, saclike outgrowths containing DNA and surface proteins — may protrude through the cell wall of the spirochete, eventually separating and floating free. Those blebs may become round body forms (also called cell wall–deficient forms). The typical response of the human immune system to invasion by pathogenic bacteria is to release macrophages (a type of white blood cell) that engulf the bacteria and destroy them. However, macrophages recognize and destroy round bodies less readily than they do spirochetes. Round bodies also initiate a different cytokine response from the immune system than do spirochetes. Cytokines are proteins secreted by certain cells of the immune system that regulate various inflammatory responses. The cytokine response to B. burgdorferi in its round body form has been shown to contribute to the development of Lyme arthritis.12 Interestingly, research has also shown that B. burgdorferi spirochetes can be triggered to take on the round body form when they come into contact with antibiotics.

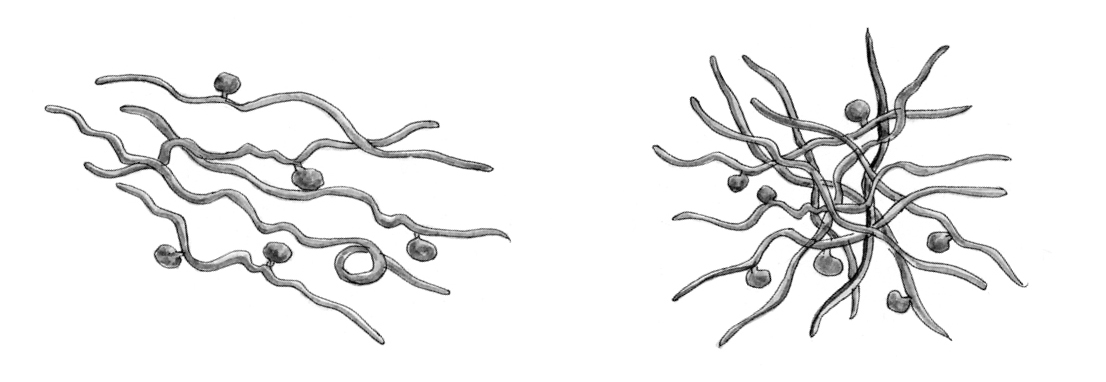

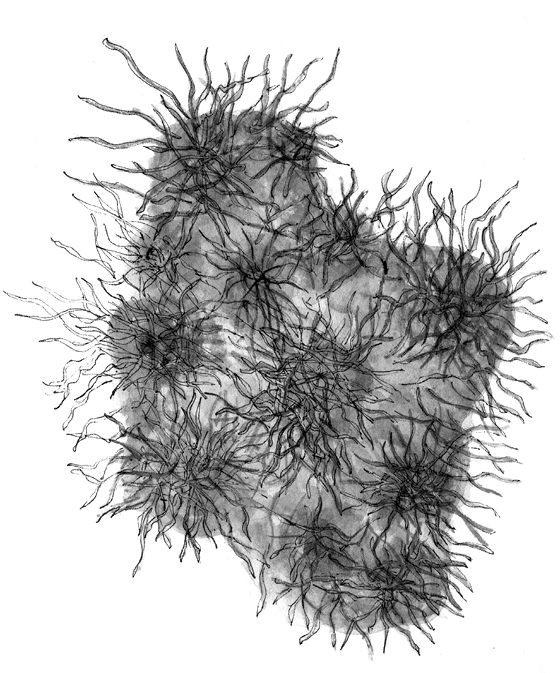

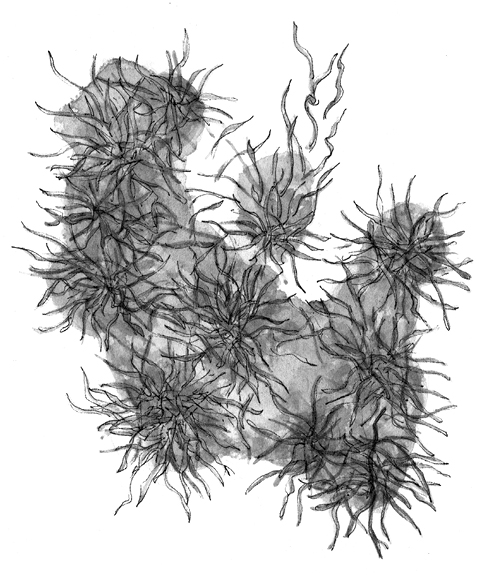

In another useful (for the bacteria) strategy, a community of B. burgdorferi spirochetes can come together in the human body and create a structure around themselves called biofilm. Think of biofilm as a slimy mass (made of mucoid polysaccharides and proteins) that surrounds the Borrelia community and allows it to hide from the human immune system and antibiotics. Researcher Eva Sapi describes it as a city of sorts.13 Within this “city” may be numerous other types of microorganisms in addition to B. burgdorferi, all communicating, storing energy, transferring genetic information, and disposing of waste. Biofilm protects the organisms from the high temperatures and changes in pH to which they are vulnerable within the human host. When the city grows to a certain size, it splits into and releases smaller biofilm communities, in this manner spreading through and colonizing the host.

Borrelia burgdorferi also has an unusual genome that may contribute to its ability to persist in a host: it contains one linear chromosome and 21 plasmids, the highest number of plasmids of any bacterium. Plasmids are pieces of genetic information stored separately from a chromosome that can be shared with other bacteria during the reproductive process. They encode the outer surface proteins expressed by Borrelia. Thanks in part to these plasmids, there are many strains of Borrelia burgdorferi — that is, subspecies with slight genetic variation. Plasmids also play a major role in the overall infectivity of Borrelia.

After a bite from a tick carrying Borrelia burgdorferi, a human can develop borreliosis, better known as Lyme disease. A decrease in white blood cells (leukopenia) or an increase in white blood cells (leukocytosis), a decrease in platelets (thrombocytopenia), elevated liver enzymes, elevated sedimentation rate, and elevated creatine phosphokinase may be seen in the blood of a human with Lyme disease.

The Stages of Biofilm Development

Biofilm protects Borrelia burgdorferi and other microorganisms from the body’s immune system.

Early stages: Microorganisms such as Borrelia spirochetes begin to clump together and produce mucoid polysaccharides and proteins.

Fully formed: The slimy mass of biofilm pervades and encapsulates the microbial community, protecting it from the body’s immune system and facilitating exchanges between the resident microorganisms.

Splitting: Eventually the biofilm community splits, forming new, smaller communities that can spread in the body.

Signs and Symptoms of Lyme Disease

Note: The bull’s-eye rash is perhaps the most well-known symptom of Lyme disease, but fewer than half of patients recall ever having a bull’s-eye rash. The erythema migrans can manifest in many other patterns, too, including those listed at left. See the photos on the identification guide at the end of this book for a look at some of these alternative presentations of erythema migrans.

Symptoms of Lyme disease usually occur between 3 and 30 days after a tick bite but can take months to appear. Proper comprehensive early treatment usually results in full recovery. See chapter 6 for recommendations regarding early comprehensive treatment.

Persistent symptoms from a Borrelia burgdorferi infection can occur after contraction of Lyme disease, even after antibiotic treatment. The spirochete’s survival mechanism, which allows it to change forms and to hide in biofilm, and its expression of surface proteins can help it evade the immune system, while it may also release proteins that inactivate certain immune system responses. B. burgdorferi’s outer surface proteins may also mimic human cells, so that a person’s immune system accidentally attacks itself in addition to the invading bacteria.14 Additionally, there may be other Borrelia species that have not been killed by antibiotics or other untreated tick-borne diseases that make it difficult for a person’s immune system to resolve the infections. Eating a proinflammatory diet of foods like sugar, yeast, alcohol, grains, and processed foods may contribute to a lingering infection.

•••

Lyme disease is the most common tick-borne disease in the United States, but many other pathogens carried by ticks in the United States may be transmitted to humans: anaplasmosis, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, rickettsial spotted fever group, tularemia, Powassan virus, Heartland virus, tick-borne relapsing fever, Colorado tick fever, southern tick-associated rash illness, and possibly bartonellosis. We’ll look at all these next.

Anaplasmosis, another disease borne by deer ticks, is caused by the Anaplasma phagocytophilum bacterium. Anaplasmosis is also called human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA) and was previously called human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE). Anaplasma is a gram-negative bacterium that infects neutrophils, a type of white blood cell, inside the host. A decrease in white blood cells (leukopenia), a decrease in platelets (thrombocytopenia), and elevated liver enzymes may be seen in the blood of a human with anaplasmosis.

Signs and Symptoms of Anaplasmosis

|

|

Symptoms occur between 5 and 21 days after a tick bite. Treatment usually results in full recovery.

Not notifiable

Not notifiableBabesiosis is a deer tick–borne disease caused by Babesia microti, B. divergens, and B. duncani. The Babesia protozoan is malaria-like, reproducing in the red blood cells of the host. A decrease in red blood cells (hemolytic anemia), a decrease in platelets (thrombocytopenia), elevated creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and elevated liver enzymes may be seen in the blood of a human with babesiosis.

Signs and Symptoms of Babesiosis

Some symptoms caused by babesiosis are similar to those caused by Lyme disease:

|

|

There is conflicting data for Mississippi; see the note

There is conflicting data for Mississippi; see the noteA classic babesiosis presentation includes:

|

|

Symptoms can appear within 1 week or after several months from the tick bite. Babesiosis can be life threatening to people who do not have a spleen, the elderly, those with liver or kidney disease, and individuals whose immune system has been compromised.

Ehrlichiosis is caused by bacteria transmitted typically by lone star and Gulf coast ticks. It is also called human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis (HME) and is caused by Ehrlichia chaffeensis, E. ewingii, or E. muris eauclairensis (formerly called Ehrlichia muris–like agent). Ehrlichia is a gram-negative bacterium that infects monocytes, a type of white blood cell inside the host. Only 68 percent of people diagnosed with ehrlichiosis remember a tick bite.15 There is a 3 percent fatality rate for E. chaffeensis, which causes more severe illness than E. ewingii or E. muris eauclairensis. A decrease in white blood cells (leukopenia), a decrease in platelets (thrombocytopenia), and elevated liver enzymes may be seen in the blood of a human with ehrlichiosis. In 2011, E. muris eauclairensis was discovered in Wisconsin and Minnesota. The new species has been detected in the blacklegged tick, Ixodes scapularis, in Wisconsin and Minnesota.16

Not notifiable

Not notifiableSigns and Symptoms of Ehrlichiosis

Symptoms occur between 5 and 14 days after a tick bite. Treatment usually results in full recovery.

Spotted fever is a disease caused by an infection with rickettsial bacteria. Rickettsia is a genus of gram-negative bacteria with a parasitic nature. There are more than 30 species and subspecies.17 Rickettsia infects ticks as well as other arthropods worldwide. For our purposes, we will focus on the rickettsial spotted fever group, which infects ticks in North America. Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is caused by Rickettsia rickettsii, which is carried by the American dog, brown dog, and Rocky Mountain wood ticks. Other spotted fever group (SFG) rickettsial disease is caused by Rickettsia parkeri, which is carried by the Gulf coast tick, and R. philipii, which is carried by the Dermacentor occidentalis tick (see here).

Rickettsia invades the endothelial cells of blood vessels in humans. When capillaries are broken by the bacteria, the result is the hallmark appearance of Rocky Mountain spotted fever — petechiae, a red or purple spotted rash. Less than 50 percent of people have the rash within the first 3 days of illness, and a smaller percentage never develop a rash. Children are more likely to develop the rash. Only 55 to 60 percent of people who were diagnosed with Rocky Mountain spotted fever18 remember having a tick bite. There is a fatality rate of 5 to 10 percent for those who contract Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Fatality rates are disproportionately higher in young children. A slight increase in white blood cells (leukocytosis), decrease in platelets (thrombocytopenia), slightly elevated liver enzymes, and low sodium (hyponatremia) may be seen in the blood of a human with Rocky Mountain spotted fever, with similar but milder findings in people with Rickettsia parkeri rickettsiosis.

Not notifiable

Not notifiableSigns and Symptoms of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (R. rickettsii Infection):

Days 1–4

|

|

Days 5+

Symptoms of Rocky Mountain spotted fever occur between 3 and 12 days after a tick bite.

Signs and Symptoms of R. parkeri Rickettsiosis

Symptoms of R. parkeri rickettsiosis occur between 2 and 10 days after a tick bite.

Signs and Symptoms of R. philipii Rickettsiosis

|

|

R. philipii rickettsiosis is a newer, less common disease, and information on when its symptoms manifest is unavailable at the time of this writing. Research is ongoing.

Tularemia, or rabbit fever, is a disease caused by Francisella tularensis. It is transmitted by the American dog, lone star, and Rocky Mountain wood ticks. It is a gram-negative bacterium that infects macrophages, a type of white blood cell. In addition to tick bites, tularemia is also spread through deerfly bites and contact with infected animals, such as rabbits, rodents, and sometimes birds, cats, and dogs.

Signs and Symptoms of Tick-Transmitted Tularemia

|

|

Symptoms of tularemia occur between 3 and 15 days after a tick bite.

Powassan virus is the “only North American member of the tick-borne encephalitis serogroup of flaviviruses.”20 The transmission of the Powassan RNA virus from a tick to a host can happen very quickly, in as little as 15 minutes! While only found in less than 4 percent of Ixodes scapularis ticks, Powassan virus is fatal in 10 percent of cases. Fifty percent of people who develop neurological symptoms continue to experience long-lasting symptoms.

Signs and Symptoms of Powassan Virus

Early symptoms during the first week:

|

|

Next phase, lasting weeks to months:

|

|

Potential long-lasting symptoms:

|

|

Symptoms of Powassan virus occur between 1 and 5 weeks after a tick bite.

Heartland virus, transmitted by the lone star tick, is caused by a virus (specifically, a member of the Phlebovirus genus). A decrease in white blood cells (leukopenia), a decrease in platelets (thrombocytopenia), and elevated liver enzymes may be seen in the blood of a human with Heartland virus. This is a recently discovered tick-borne RNA virus; 40 cases were reported nationwide as of September 2018.

Signs and Symptoms of Heartland Virus

|

|

The incubation period is unknown, although most people with Heartland virus reported a tick bite within 2 weeks of illness onset.

Although Borrelia burgdorferi, which causes Lyme disease, is the most studied organism, it is important to note that there are other species of Borrelia that cause other kinds of illness. There are 15 Borrelia species that cause tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF) worldwide. B. miyamotoi is the only Borrelia species carried by an Ixodes (hard) tick that causes tick-borne relapsing fever. B. miyamotoi may be transmitted from the adult female Ixodes tick to its eggs, which results in infected tick larvae. All other TBRF Borrelia are transmitted from Ornithodoros (soft) ticks.

Most common in Africa, Central Asia, the Mediterranean, and Central and South America, cases of TBRF have been also been reported in western United States and Canada.21 Borrelia hermsii, B. parkeri, and B. turicatae are the three species transmitted by Ornithodoros ticks that cause TBRF in the United States. Most commonly, a human may become infected after sleeping or working in a rodent-infested cabin, hunting camp, barn, or building. During the night, the tick may incidentally attach to a human for a short time and cause a painless bite. In the United States, TBRF occurs most commonly in 14 western states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Oregon, Texas, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.22TBRF may cause relapsing symptoms lasting 3 days, followed by 7 days without a fever, followed by another 3 days with a fever. Elevated liver enzymes may be seen in the blood of a human with TBRF.

Signs and Symptoms of Tick-Borne Relapsing Fever

Common symptoms:

|

|

Less common symptoms:

|

|

Symptoms begin 7 days after a tick bite. TBRF may resolve on its own after several months. However, given the complicated nature of Borrelia species and the diseases they cause, I’d recommend treating as described in chapter 6.

Colorado tick fever, a disease borne by Rocky Mountain wood ticks, is caused by a virus (specifically, a member of the Coltivirus genus). It infects red blood cells. A decrease in white blood cells (leukopenia), a decrease in platelets (thrombocytopenia), and elevated lymphocytes (lymphocytosis) may be seen in the blood of a human with Colorado tick fever. Eighty-three cases of this RNA virus were reported from 2002 to 2012.

Signs and Symptoms of Colorado Tick Fever

|

|

Symptoms of Colorado tick fever occur between 1 and 14 days after a tick bite.

Southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI), or Masters disease, is a syndrome with unknown causes. Spirochetes that look similar to Borrelia were found in lone star ticks. Studies point to a connection between the pathogen, a lone star tick bite, and an illness that developed. At this time, there is not enough evidence to show a causal relationship between Borrelia lonestari and the illness people have exhibited called STARI after a lone star tick bite. However, I highly suspect that the bull’s-eye-like rash seen in STARI is caused by a Borrelia species, since an erythema migrans is a classic proven manifestation of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. Furthermore, other symptoms that may be experienced by someone diagnosed with STARI mimic those of Lyme disease.

Signs and Symptoms of STARI

|

|

More research is imperative to learn about STARI and its cause. As of this writing, there is no surveillance of the disease, and therefore we do not know how many people have been infected. I suspect there may be a silent epidemic of STARI waiting to be uncovered.

Note: Distribution information on STARI is currently unavailable.

Bartonellosis is a disease caused by Bartonella species, which are gram-negative bacteria. They infect endothelial cells of blood vessels and multiply inside red blood cells. The disease exists worldwide. Bartonella species are most commonly transmitted to humans through contact with fleas and lice. For example, B. henselae, which causes cat scratch fever, is transmitted to humans via flea feces carried in cats’ nails. Ticks can also carry Bartonella species. One study in New Jersey and another in California showed that some Ixodes scapularis and I. pacificus ticks, respectively, carried Bartonella.23 However, no current evidence shows that ticks can transmit Bartonella to humans.

Signs and Symptoms of Bartonellosis

|

|

The question of whether Bartonella species can be transmitted by ticks to humans is a topic demanding serious scientific exploration. In addition, more research is necessary to identify which specific Bartonella species is carried by Ixodes scapularis and I. pacificus. I suspect there will be more research in the near future that will address this important issue.

A rare phenomenon called tick paralysis can be caused by a neurotoxin carried in the saliva of the deer tick, American dog tick, Rocky Mountain wood tick, and lone star tick. Tick paralysis is the only tick-borne disease that is not caused by a pathogen and that can only persist while the tick is attached. Poor coordination followed by paralysis that starts from the lower parts of the body moving upward, and numbness or tingling, is the common presentation. It usually happens after the tick has been attached for 5 or more days. As soon as the tick is removed, the symptoms resolve.