FIG. 1 Benjamin Franklin, “MAGNA Britannia: her Colonies REDUC’D,” ca. 1766. Engraving. Courtesy of Library Company of Philadelphia.

Curious reader: it might be said that a solemn lie about national character stands on one leg, a caricature of it on two. In November 1773, Benjamin Franklin wrote a letter to his sister. He was in London as a representative for colonial America, trying to secure peace and commerce between the colonies and the Mother Country without “the Commencement of actual War.”1 Insurrection, after all, more and more seemed to be the most viable route to independence. Diplomacy was not working. In spite of “all the smooth Words I could muster,” Franklin wrote, “I grew tir’d of Meekness when I saw it without Effect.”2 So he decided to get “saucy,” composing two of his most famous humorous tracts, “An Edict by the King of Prussia” and the companion piece “Rules by Which a Great Empire May Be Reduced to a Small One.” Both appeared in a London newspaper, the Public Advertiser, in September 1773, as well as in a Philadelphia newspaper of the same name. They were part of Franklin’s oeuvre of jeux d’esprit (comic witticisms), satires, and political cartoons. The squibs expanded on mockeries of the plain truths and public goods that made up Poor Richard’s Almanack (1732), establishing a way of seeing America not only for its righteous pursuits of life, liberty, and happiness but also for the foolish idea that war could foster democratic peace. What is more, his literary travesties evinced the rhetorical force of caricature insofar as, in Franklin’s words, they “held up a Looking-Glass” for Ministers to “see their ugly Faces,” for the British nation to see “its Injustice,” and for the rights (and Right) of America to be seen in the distorted reflection of Imperial wrongs.3

Franklin is the standard bearer for a mode of particularly American humor that is driven by logics of mordancy, monstrosity, and devil-may-care cheekiness—and by a preoccupation with national character. At the center of these logics are problems of collective identity, public conduct, and national culture.4 In Franklin’s descriptions of squabbling proctors and pettifoggers are resonances of the part-time cartoon artist’s Magna Britannia wherein national dismemberment is displayed through a leprous Lady Britain whose body parts (representing the American colonies) have been cut off (fig. 1). Such a grotesque image typifies a deep-seated tradition in American humor of using ugliness and injustice as the rhetorical forces in caricatures of national character. Even so, this book is not about Franklin. Nor is it about the wartime caricatures of this most humorous of Founding Fathers. Rather, Caricature and National Character focuses on the comic politics of caricature as they have cropped up in wartime milieus defined by moments of national—and, to be sure, international—disturbance.

FIG. 1 Benjamin Franklin, “MAGNA Britannia: her Colonies REDUC’D,” ca. 1766. Engraving. Courtesy of Library Company of Philadelphia.

Building on the notion that single artists and singular rhetorical artifacts can capture core public attitudes, this book engages the works of particular cartoon artists whose caricatures sift through the madness of America at war. My artists of interest hearken to the Founding Period, but they come from twentieth- and twenty-first-century war cultures in which national character is the point of departure for rather than the endpoint of democratic wrangles and ultimately armed conflict. Franklin’s entire political and cultural project was largely the production of a national self-consciousness. This project was picked up by many nineteenth-century political cartoonists and comic artists. Thomas Nast was probably the most prominent purveyor of a comic ars nationis. Nast’s work, published in Harper’s Weekly, Judge, Leslie’s Weekly, Puck, and more, bears traces of Franklinesque humor, grounded as it was in a growing stock of grotesque imagery for portrayals of strangers and strangeness in the American body politic. US American humor is full of the most prominent fools and knaves as well as the most nationalistic, prideful solons of the age. Both Franklin and Nast were concerned with statecraft. Both, too, presented the United States not only as a nation best understood through caricature but also as a caricature of itself. Franklin pursued nation building. Nast was drawn to the apparent decline, if not the poisoned well, of a burgeoning republic at the hands of witless warmongers, vicious lords and masters, and corrupt politicians. At the time of the American Revolution, there was not yet an ironed-out American nation to defend. The Civil War era, too, saw struggles over the big ideas of American ideals, and no real emergence of a coherent national image. The American Revolution fomented a war for principles, the Civil War a war of principles. By the early twentieth century, the United States was conducting war on principle.

The Spanish-American War lurks in this setup. An end of Two Americas (i.e., North and South, Union and Confederate) was, by turns, a precursor to the inception of 100 percent Americanism. The Spanish-American War presaged a sense of national wholeness that remained long after President Theodore Roosevelt’s rough riding spirit and rhetoric of the nationalistic frontiersmen led to what Louis A. Perez Jr. calls an “Imperial Ethos,” propelling the sort of hyperpatriotism that animated World War I propaganda and pegged Americanism as a cultural good.5 The quick execution of war for international territories in the summer of 1898 left an indelible mark on images of Americanism. For one thing, armed conflict became an important means of asserting national character in homegrown battles of public opinion amid hostilities on the world stage. Yellow journalism thrived in this context. So did political cartoons of Uncle Sam reaping the glories of military conquest, such as those by Clifford K. Berryman, Rowland C. Bowman, Victor Gillam, and W. A. Rogers. So, too, did a generalized mythos of American exceptionalism that replaced past social, political, cultural, and humanitarian indiscretions with a more plural “Americanness.” This mythos circulated a sense “that cultural values inhere in particular racial, ethnic, or national groups.”6 There are precious few degrees of separation from this mythos and, say, the Know-Nothings, the Chinese Exclusion Act, diffuse anti-immigrant sentiments, eugenics, and America First ideologies. Even Franklin expressed concern about the “Complexion” of the American nation, and thus the “invasion” of non-American “herds.” Appropriately, ethnic caricatures tended to emphasize oppositions like superiority and inferiority, Self and Other, Us and Them, thereby provoking humor that derived from cultural stereotypes.7 The “Spanish Brute,” for instance, represented what an American was not, just as portrayals of Filipinos as “The White Man’s Burden” stood for a march from barbarism to civilization.8

The Spanish-American War also stands as a touchstone for ethnocentric claims to American national character, laying the groundwork for a nativism that rejects indigenous peoples with a blend of xenophobia and nationalism, rhetorics of “foreigners” and “outsiders,” and troubled perceptions of what Teddy Roosevelt called “hyphenated Americanism.” Given that Americanism presumes its righteousness in the transcendental democratic project, its war powers bring about its global influence, and vice versa. As Paul T. McCartney attests, American national character by 1900 was “the normative standard on which to base the country’s actions and measure its successes in global affairs.”9 Lest we forget, though, the Wounded Knee Massacre occurred less than a decade prior to hostilities in the Pacific and Caribbean. Armed conflict, in both cases, was a recourse for dealing with struggles around cultural identity, civil rights, and self-determination. The one saw embattlements over American imperialism and the Jim Crow empire. The other sowed the seeds of the American Indian movement. The one was an augury for international power grabs. The other was a seedbed for colonialist claims to sacred Native lore and lands. The one, a catapult for a global expansion of the American experiment. The other, a cudgel for US Americanization. Wartime caricatures have long captured what Gillam once drew as Uncle Sam’s burden. This burden is made up of the oppressions, brutalities, ignorance, slavery, cruelties, and vices that chisel out a rocky traverse in and through the uncertain terrain on which US Americanism stands.

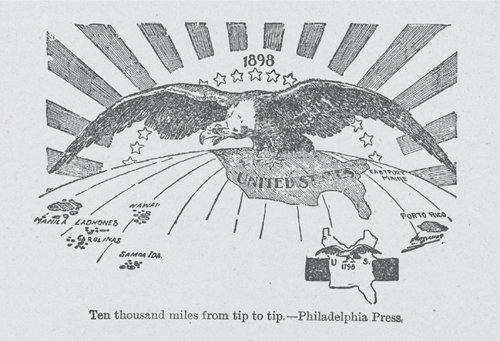

In these ways and more, the infamous and iconic political cartoon that appeared in the Philadelphia Press in 1898, “Ten Thousand Miles from Tip to Tip” (fig. 2), seems to show it all. The bald eagle, once a spirit symbol of numerous Native American tribes, stands on the United States and spreads its wings from Manila to Puerto Rico. Beneath it, a carbon copy of the bird of prey presides over a diminutive depiction of American territories from 1798—a testament to the reach of national character from a quasi-war through a civil war, and then again from an assault on the Lakota nation beside a South Dakota creek to what President William McKinley’s secretary of state John Hay called a “splendid little war.” Warfare had become a defense mechanism for the majesty of America. The figure of Uncle Sam as a compassionate, benevolent protector merged with his personification of a nation breaking away from its constitutional bonds to life and liberty, and forging new nationalistic boundaries with imperialist undertakings. The caricature of an American eagle revels in the view of colonial possibilities abroad, and yet it seems to ask its viewers to take a second look.

FIG. 2 Marshall Everett, “Ten Thousand Miles from Tip to Tip,” 1899. From Marshall Everett, Exciting Experiences in Our Wars with Spain and the Filipinos (Chicago: Book Publishers Union, 1899). Cornell University: Persuasive Cartography: The PJ Mode Collection. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

The years following the Spanish-American War and leading into the World War I era therefore serve as apt markers for US Americanism, namely in terms of what President Woodrow Wilson dubbed its “leading characters” in a global human drama.10 The First World War was a fight for transnational democratic tenets that were said to characterize members of—and wannabe adherents to—the US American body politic. It also just so happens that the Great War involved the propagandistic imagery of a war machine in ways that the Civil War and the Spanish-American War did not. Out of it came mad German beasts cast as gorillas with Pickelhaubes. There were Huns with bloody bayonets. Destroyers with missiles rendered as Liberty Loans. The American warrior portrayed as a cross between Hercules and Captain America engaged in combat with the Ghost of Death, the Ghoul of Devastation, the Wolf of Starvation, the Snake of Pestilence, and most glaringly the Unmensch of War. Columbia was an angel of peace. The Statue of Liberty was personified as a divine interventionist of the American creed. Citizens were farmers, dealers, members of the House Wife’s League—and soldiers. Excluded from most of these images were thorny domestic matters of racial tension, women’s suffrage, the menace of jingoism, ideologies of industrialization, and the warring cultural productions of civic duty and consumerism. But there was plenty of ethnocentrism. Simply, caricature is inexorably tied up in a mess of American militarism, wishful democratic thinking, and nationalistic image making.

The reason is that caricature is a rhetorical mode of variously amplifying, distorting, and even conjuring ways of seeing both personal and public selfhood. It is humorous when a certain hilarity, however dark or gloomy, overwhelms the horror that might otherwise be gleaned from ugliness. It is also ruthlessly historical with its references to past travesties in the trials and tribulations of the present day. Its humor comes from a visual dédoublement (duplication), which appears as a comic anamorphosis wherein multiple sides of a character or of a characteristic are reflected in congruency but also in conflict. My primary focus is on editorial cartoons of national character and the humor of comic takes on deep-seated American values. National character encapsulates such values. Caricatures fill out the comic space to engage, exhibit, and redeem what Umberto Eco might call the most “ugly truths” of normative assumptions about collective selfhood.11 At base, caricature goads a people to look at itself in the comic looking glass, with humor on one hand and an alternative view of history on the other.

To develop and dwell on these critical threads, Caricature and National Character concentrates on a handful of caricature artists that animate US American values in war cultures from World War I forward. There is a phrase: “the looking glass.” It is a colloquial way of referring to a mirror, and even to that which is normal or expected, and therefore in or out of character. It’s an old-fashioned phrase. Yet it underwrites many of the critical threads in this book insofar as it telescopes precisely how some of the ugliest truths of the good and the bad in American national character are caught up in a historical predilection to humor war. So it is that we come back to Franklinesque humor as a basis from which to realize the rootedness of caricature in so many wartime attempts to unmake and then remake an image of America through both international affairs and national issues of things like race, gender, and ethnicity. Franklin’s version of American humor developed in the face of war. In the same year that he produced “MAGNA Britannia: her Colonies REDUC’D,” which was supposedly printed on cards and distributed to members of Parliament in the shadow of the Stamp Act, Franklin was also testifying before the House of Commons about the “American Interest” and the “force of arms” that would be compelled if imperial oppressions continued to contravene a people of Providence.12 In other words, the Fates and Follies of American national character align with the humor around its “historiographic fantasies.”13 The American Dream is, in part, an imagination of Americanism itself at the end of history. It is also a rhetorical boilerplate for historical patterns of waging war as a national fait accompli. There are foundations for these patterns in Franklin’s America. His politics were born of colonialism. They were born, too, of his time as a military commander during the French and Indian War, subsequent to his years in the Pennsylvania Assembly but seminal to visions of Manifest Destiny and Western (as well as westward) expansion. Franklin was an inventor. He was a postmaster general. He was a diplomat. A writer. A military man. A revolutionary. He knew well the entwinement of war and culture. Franklin’s own caricatures of the colonies and of his dream for a new world order imagined civic and military engagements as conditions of democratic possibility. They also serve as harbingers for an enduring type of humor about national character that melds aesthetic pleasure, political provocation, and comic effect in an ugly rhetorical standoff of “good” Selves and “bad” Others.

The core point is this: if war is vitally caught up in who Americans are, then caricatures are similarly vital to understanding armed conflict as the catch to a no less democratic genius loci. Wars put the strengths (and weaknesses) of national character to the test. War is foundational to US public culture. Franklin observed as much when he gazed through his own looking glass at the close of the American Revolution, recounting the ways to his London landlady’s daughter just eight months before becoming a signatory to the Treaty of Paris and seven years after signing the Declaration of Independence. “All Wars are Follies,” Franklin wrote. He went on to promote the utterly democratic chances integral to the “Cast of a Dye” over and above the mischievous will to Fight and Destroy. He closed with an appeal to Friendship and Love.14 Caricatures offer historical resources for interrogating and understanding the deep conflicts in cultural dispositions—toward love, friendship, destruction, and war.15 In their artistry (and the individuals under study here are talented comic artists) is what scholars have increasingly recognized as the rhetorical witness of tensions around collective selfhood in combat zones and in war cultures.16 Consequently, more important than historiographical veracity is the view of a nationalistic set of images and ideas that make war for democracy look and feel like democracy for war when American national character is seen via caricature, in the comic looking glass.

I write at a compelling moment of both crisis and judgment when it comes to finding humor in matters of national character, war cultures, and cultural warfare. There is an ongoing US military presence in the Middle East and elsewhere despite urgent, and old, calls for the end to endless war. The threat of nuclear war suffuses the global sensorium, never mind the anxieties around an impending barbarism in the face of a global climate crisis. Authoritarianism is on the rise. Democracy is on the decline. The War on Terror lives on. And there is a pandemic wreaking havoc on the globe. At the same time, there is a US president in the Oval Office who comes off as little more than an Ugly American in his unabashed commitment to identitarian politics. President Donald J. Trump represents the worst of flag-waving and political fury, with a worn-out foreign policy of America First and such a loose grip on executive leadership that the social media network Twitter has become a sad site for letting slip the dogs of war. Still, caricature remains the rhetorical outlet de rigueur for dealing with Trumpism and its apotheosis of foolishness, vulgarity, and corruption. President Trump is widely seen as an imperial president on so many warpaths. Trumpism amplifies national character as a theater of combat operations. For Trump, it is a rhetorical prop. But caricature is an age-old centerpiece of this comic stage. It brings rhetorics of humor to the fore in appeals to national characteristics, revealing how express ways of seeing are tied to comic expressions of the war-making conduct that seems endemic to a nation and its citizenry. Additionally, caricature shows forth the structures of wartime feeling that make certain cultural experiences markers of collective temperaments.

This book therefore shows how wartime caricatures are at once a light and a shadow for civic conduct. Todd J. Porterfield argues that there is an “efflorescence” to caricature given its broad reach in the American annals and its participation in the production of visual cultures.17 I would add that there is a luminescent quality to caricature, too, which generates a modality of humor that keeps national characteristics in bloom. But, as caricature reminds us, blossoms fade, flowers decay, and lit objects lose their luster. In 1861, a French writer and close friend of Charles Baudelaire, Charles Asselineau, wrote of caricature as a rhetorical art of humor that looks upon those who fail or refuse to see how and why they are grotesque.18 Caricature can be an evil flower—le fleur du mal. Its shadow appears in a gaze cast on the laughable. Wartime images about the good, the bad, and the ugly of national character thrive in this shadow. As such, caricature is also a basis for grappling with recurring images of the savagery, lunacy, fiendishness, and fanaticism that gets projected onto enemies, both foreign and domestic. To see the light of America is to see its democratic possibilities. To see the shadow beside it is to look upon how ridiculous that light can be when seen for the imperialisms and injustices that reside in its deep surfaces.

America the Ridiculous, or the Folly of War

If the follies of war are at least partly integral to US Americanism, then war footings are at least partly inherent to democratic peace.

But let us back up a bit.

If only the Turkey had been named our national emblem rather than the Bald Eagle. This might seem ridiculous. Yet in a letter to his daughter, Sally Bache, in 1784, Franklin ruminated on this very idea while commenting on a medal drawn up by the Society of the Cincinnati. The Bald Eagle is a thief and a miscreant, Franklin wrote, and “by no means a proper emblem for the brave and honest Cincinnati of America.”19 The Turkey, however, is “a much more respectable Bird, and withal a true original Native of America.” And, “though a little vain & silly,” it is “a Bird of Courage” willing “to attack a Grenadier of the British Guards who should presume to invade his Farm Yard with a red Coat on.” Relatedly, in the lead-up to Independence Day, Franklin hearkened to his 1754 “Join, or Die” serpent (and eventual “Don’t Tread on Me” mantra) when he published an anonymous letter in the Pennsylvania Journal in defense of the “Rattle-Snake” as the most appropriate emblem, with its allusions to ancient wisdom, defiant attitude, and overall encapsulation of “the temper and conduct of America.”20 At another point he even proposed a picture of Moses parting the Red Sea, encircled by the proclamation that “rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God.”21 Franklin’s Turkey manifesto is something of a literary caricature. It is turkey talk. But in this and other bids for fitting national imagery is some potent visual commentary on national character.

The very idea of a “national character” was prominent in the early 1900s and then variously critiqued in the middle of the century by Erik Erikson, Geert Hofstede, Luther S. Luedtke, and others. There is not a national culture. Still, there is a tangle of concepts like nation, nationality, nationalism, and national identity.22 My aim is not to pull off a conceptual sleight of hand in making sense of what Walker Connor calls this “terminological chaos.”23 Instead, it is to engage how these concepts entail images of a people as they relate to systems of government, commitments to a set of common interests, and reactions to social, political, and military conundrums that challenge representations of collective selfhood. In the United States, nationalism tends to typify a sacred creed defined by powerful and ethno-religious ideas of civic duty and the pseudomythological worship of a Revolutionary naissance. Principles of “American belonging,” in David Waldstreicher’s words, often abide “the prophecy of independence.”24 This prophecy has profound roots in resistance to the Stamp Act, wherein a public (and, importantly, a print) culture of ridicule led American citizens to recognize one another as national selves through the “good” logic of a No True American fallacy. Central to this resistance was a drive “to keep the focus national and to fix the burden of opprobrium on the common enemy.”25 That enemy was the Crown. Its threat was to what Franklin testified as the “civil and military establishment” of America, partially in the wake of the Seven Years’ War but also with respect to the will of an American nation already steeped in ideologies of constitutionality and justice.26 To be American is, in part, to implicate oneself in such narratives, traditions, myths of origins, battles, and—yes—moralistic bromides. America is a characteristically conflicted nation with a fraught nationality, a sometimes chauvinistic nationalism, and a national identity driven by the primacy of the individual. This all makes national character a loaded term.

In acknowledging the loaded nature of national character, it is worth noting just how much matters of race and ethnicity weigh on the supposed comicality of images and ideas. The chapters in this book will bear out these weightings where appropriate. For now, though, consider that history does not repeat itself per se but rather presents so many resources to think through the problematics of bygone eras as they seem to bear some semblance in the present. Race and ethnicity blend, or worse bleed, into nationalistic classifications of in- and out-groups, with rhetorical cultures variously playing up or down physical characteristics and character traits as classificatory regimes.27 As Henry B. Wonham puts it, in the broadest and narrowest of senses, to caricature is to characterize.28 There is an argument to be made, then, about how nationalisms imply racialized identifications colored by reductive notions of national culture and how ethnonationalisms intimate diffuse appeals to blood and soil. In so many caricatures are deep, dark histories of complicity with racist depictions of people of color and with presumptions of white spectatorship. Some have tried to claim that these depictions are due to this or that comic spirit of the times. But in 2020, a combination of the COVID-19 pandemic and the persistent problem of police killings of Black people has revealed once again how character flaws are predicated upon cultural structures of fealty and feeling. Caricatures can be comic lessons in anti-racism and national fellowship. They can also be cruel fodder for white supremacy and nationalistic resentment. One of my primary interests is in paying careful attention to issues of race and ethnicity, as well as other cultural, political, and economic issues as they coalesce in wartime caricatures. Another interest is to attend to the rhetorical potential of caricature for a comic politics of care. Such a politics imagines a cracked mirror when it deals with the mix of bad information, bad feelings, bad faiths, and bad intentions in the most monstrous caricatures. At its best, caricature reminds us how important it is to be ever so vigilant with our ways of seeing.

Yet wartimes do muddy these waters. So many of the rhetorical touchstones of Americanism (or, maybe more aptly, American warism) are virtual clichés. Join, or die. Don’t tread on me. The nation must be saved! Respond to your country with dollars. The enemy laughs when you loaf. Wake up, America! Attack on all fronts. We can do it. Are you doing all you can? It can happen here. And so on. Then again, there are counternarratives in so many alternative American truisms. War is not the answer. Books, not bombs. Make love, not war. You can’t buy freedom with blood. Get out. Give peace a chance. War is folly, a black crime against us all. Resist. In whatever guise, the discourses circulated in such images and ideas embody character judgments, whether in terms of what Michael Billig dubs a “banal nationalism”29 or in bold anachronisms that revert to a “red-blooded, white-skinned, blue-eyed son of liberty and freedom” in the specter of Uncle Sam.30 War can bolster a shared sense of belonging. As is seen in caricatures that seem to laugh off the travesties of Americanism, though, it can also lead to what nowadays might be called a rather banal warism.

In some instances, caricatures serve as weapons of comic scorn wielded against nationalistic standards of judgment for wartime conduct. Here they seem to forge fresh, even if farcical, bonds between those images, ideas, individuals, and cultural institutions that influence national character. These weaponized caricatures validate rhetorical warfare with imagined enemies. But they also lead to a humorous regard for the American body politic in a comic looking glass. When I refer to war’s follies, I am not simply referring to the futility and foolishness of decades-old American foreign policy.31 Caricature and National Character offers a rhetorical critique of war cultures in the United States according to the humor that caricature draws from images of national character. Contra Henri Bergson, the humor of caricature derives from both rigidness and ugliness.32 It “walks [a] thin line between pleasurable play with transgression and presentation of frankly unacceptable materials.”33 Furthermore, the humor in caricature exposes a comic frontier wherein there can be no talking with a Boche, never mind a Hun or a Gook, and where no punches need to be pulled with Jim Crow or apologies made for Jap Traps. In this book, caricatures of national character exemplify the unsettled grounds in a warring tradition of, by, and for the US American Way. The weight of this humor, and indeed of this book, therefore lies in the distorted ways of seeing how comic images of national character across modern US history and into the era of late modernism burden us to take seriously a stubborn persistence of war in democratic peace.

My core argument, then, is that what George Washington once called the “plague of Mankind,”34 war, is deeply connected to what nineteenth-century writer H. H. Boyesen called in the North American Review the “plague of jocularity” in American national character. For Washington, a democratic peace is the first commandment of a free people. For Boyesen, an “all-leveling democracy” is the very thing that hedges all bets on judgments of the sacred or profane, war or peace, comedy or tragedy.35 In characterizing the sacred roots of democracy as the profane outgrowths of war, caricature creates something of an all-leveling humor peculiar to the United States. To say that there is a specifically American humor, though, is sort of like saying that there is a singular American national character. The spirit of a nation is the shadow to a tree, President Abraham Lincoln once said. Its roots are deep. But its look and luster shift shape in the glares of history. No shadow ever stays the same. Nor is there any definitive national character or form of humor that, alone, typifies it. Nevertheless, if dispositional characteristics and founding principles like liberty, freedom, republicanism, and so on constitute a multifarious image of collective selfhood, then caricatures that mingle with repression, strong arm tactics, imperialism, stereotypes, and more stand out in a shadow Self of the nation. Benedict Anderson once remarked on the almost comic effect that nationalistic imaginations can have when they warp perspectives of collective selfhood so much so that all peoples, nations, symbols, monuments, and cultural products can somehow appear foolish.36 In some ways, national character is a caricature unto itself. The era of liberation movements, which generally corresponds to the century between 1820 and 1920, witnessed the rise of “visible models” of national character that were otherwise confined to dispersed frames of vision.37 World War I marks a pivotal moment for nationalistic politics of caricature and for US American humor. By World War I, caricatures of national character incorporated humor to counteract gruesome realities of being at war. They also humored war cultures by stoking the tensions that sprang from images of democratic utopia in the dystopia of militarism.

The Founding Period looms large here, particularly with Franklin’s early establishment of caricature as a rhetorical resource for transforming foundational principles and folk symbols into comic armaments for wartime enforcements of the “good” and the “bad.” By the Civil War era these armaments had become weapons of cultural warfare on the home front. Brother Jonathan, a staple embodiment of the Early Republic and Mad Hatter–like trickster who was also prevalent in British periodicals, such as humor magazine Punch, in addition to American periodicals like Yankee Notions, was a prime holdover and precursor to Uncle Sam (fig. 3). The earthly goddess, Columbia, was frequently set against the fallen figure of the southern Cavalier, a sort of American Beelzebub and bane on notions of Pilgrim’s progress and Revolutionary predestination. By Reconstruction, while Columbia morphed into the nonpareil among images for angels of a better national character, Brother Jonathan came to represent “a devious, crude, corrupt, and violent” aspect of a nation founded not just on freedom and liberty but also on slavery, hypocrisy, and oppression.38 Eventually he was supplanted by Uncle Sam, perhaps the most “affectionate symbol of a democratic government,” and yet by the Spanish-American War and even more by World War I, the “stern authority figure, the leader of the nation-state,” and the personification of “the war atmosphere.”39 During World War II, Uncle Sam became what Brother Jonathan was in his originary guise: an embodiment of the people, in one moment rallying civic troops, in another supplicating for combat soldiers, and then again reconciling diverse expressions of patriotism, dissidence, and duty. Indeed, the cultural milieu of war facilitates a sometimes-righteous, sometimes-ridiculous rhetoric of sense and nonsense in and around national characteristics.

FIG. 3 Editorial cartoon of Brother Jonathan, ca. 1852. From Yankee Notions 1 (1852): 224.

This sense of humor is crucial in my approach to caricature, which is perhaps best gleaned from a metaphor that has been lurking in the story up to this point and that I detail below—the looking glass. Caricature is the bastard child of ethos. It embodies a framework for seeing character as a byproduct of identity and activity. Writer and humorist Kurt Vonnegut once portrayed this framework with a mock syllogism that presents itself in three lines of philosophical cum poetic wisdom. It makes up the last words of Deadeye Dick (1982) before the epilogue when the book’s main character encounters the syllogism as a bit of graffiti on a bathroom wall in Will Fairchild Memorial Airport, where he stops on the way home from work one night to manage a sudden bout of diarrhea. To be is to do, said Socrates. Not so, said Jean-Paul Sartre, when he dwelled on the burden of becoming what we will be from the fact that we are. To do is to be, he said. Then Frank Sinatra came along and summed up human existentialities with a honeyed tune: do be do be do. Here’s the mock syllogism:

“To be is to do”—Socrates.

“To do is to be”—Jean-Paul Sartre.

“Do be do be do”—Frank Sinatra.40

We are what we do. We are who and what we see, as a nation. To caricature is to aggravate vital ways of seeing and the characteristics of what is seen. It is to do rhetorical work, and to do so humorously as the burdens of historical weightings play out in characterizations and recharacterizations. National character, in caricature, is a sort of pictura rhetorica (and, in caricature, a pictura comica). What matters is the burden of humor that weighs on how a people pictures who it is and what it does as a nation.

Any image or idea of national character is at least somewhat ridiculous. Caricature is so useful because, as Martha Banta argues, it lays bare the deepest (and darkest) realities about entire cultures of conduct, patterns of cultural expectations in friend-enemy relations, and reference points for getting by in public life.41 This book builds on Banta’s argument but goes beyond a single outlet (i.e., Life or Punch) or a single artist in order to examine the transhistorical nature of cultural struggles with American national character as they appear in the work of multiple caricature artists over multiple decades. It is therefore as much about the “national” as it is about the “character” in wartime caricatures. Humor is nationalistic “when it is impregnated with the convictions, customs, and associations of a nation.”42 Such impregnations are palpable in American Humor: A Study of National Character (1931) when Constance Rourke points out that comic grotesqueries are rooted in caricatures of national character that extend from Yankee Doodle through Jim Crow Rice (the face of Reconstruction-era race conflict) to folk wisdom about the everyday confrontational antics of scalawags and crackers. Still, as Rourke describes it elsewhere, humor is so endemic to the United States because of the nationalistic fantasies caught up in the sorts of mythic embellishments that make up Americanism.43 Or, as Cameron Nickels puts it, caricature is the counterpart to self-righteousness in the characterological roots of American exceptionalism.44 Cameron Nickels, Constance Rourke, and others are points of departure for grappling with the humor of caricature by laughing along with deformations that combine the sacred and profane in new visualizations of “old” images and ideas. Caricature pictures “a cruel delight in monstrous deformity,”45 oftentimes our own monstrous deformity, and so re-views our deepest, darkest convictions, habits, institutions, and histories. Caricatures of national character amplify the folly in our rhetorical fantasies about collective selfhood.

The underlying message here is that the rhetorical weight of caricature, and within it a formative mode of US American humor, should give us pause, especially when we are made strange to ourselves. In wartimes in particular, caricatures cast comic projections in the looking glass—clearly, differently, darkly. In 1900, Mary F. S. Hervey remarked on the anamorphosis of the iconic skull in Hans Holbein’s famous 1533 painting, The Ambassadors, by referring to its “unusual character.”46 In the skull is something familiar, and yet something that requires what Jean-François Lyotard calls an act of “hesitation” when something out of whack needs to be put back into perspective.47 Caricature replaces the easy work of gut reactions and snap judgments with the more grueling work of recognition. Caricatures provoke pause such that the spectatorial choice to hesitate (or not) is a choice of whether or not to carry the weight of humor. The humor of caricatures in this book demands a willingness to take in a bit more deeply the taken for granted in American national character. War is “as old as the Republic itself.”48 So is caricature. In turning to comic images of wartime national character, I am at once turning to a cultural politics of America the Ridiculous, wherein warism and democracy are all too familiar, albeit strange, bedfellows in the looking glass of US Americanism.

In the Comic Looking Glass

The mirror is a prominent analogue in numerous studies of caricature. Steven Heller and Gail Anderson define caricature as a “savage mirror.”49 Arthur Koestler calls it a “carnival mirror,” noting the outrageous exaggerations and monstrous distortions in its basic features.50 This sentiment is replete in scholarly accounts of looking-glass orientations as much as it is resident in the paroxysms and ordinary jests of everyday life. At the turn of the twentieth century, American social psychologist Charles Horton Cooley theorized the “looking-glass self.” Such a self is built on the complex and conflicted relationship between images of selfhood and the judgments derived of interactions with others. “Each to each a looking-glass,” Cooley poeticized with words that also appear in a verse from Ralph Waldo Emerson’s poem “Astraea.” Each to each, says Cooley, “reflects the other that doth pass.”51 We see ourselves in the appearances of others. This cultural praxis amounts to what French philosopher Michel Foucault later proposed as the genealogical work and the cultural politics of historiography to the replay of some imagined, though all-too-real, past in the rhetorical fêtes of a “concerted carnival.”52 Another French philosopher, Gilles Deleuze, followed Alice to Wonderland and approached the looking glass as what I would describe as a rhetorical tool for breaking up linearities and dichotomies, and then locating the good sense of seeing something otherwise by seeing it nonsensically.53 To see the world via caricatures, for instance through a Lewis Carroll–like imagination, is to live in the Looking-Glass House. Or, to put it in the terminology of another American personage, it is to see the fantastic rhetorical trickeries in our “glassy essence.” So wrote C. S. Peirce in 1892 while ruminating on a view of the Self as little more than the symbol of an idea.54

Notwithstanding these more scholarly interpretations, the notion that caricature shows forth its object of scrutiny or ridicule as if in a distorted mirror is also standard in so many takes on the humorously grotesque aesthetics of ugliness.55 This notion goes back to the Carracci brothers, Annibale and Agosto, two revered sixteenth-century Italian painters who sedimented the Baroque style and who saw in the visual burlesque the unique rhetorical capacity to display the peculiar character and particular defects of a person or thing. Early Americans, too, saw the looking glass as a site wherein one could develop deep knowledge of appearances and powerful senses of self.56 The point is that images of national character as collective selfhood are perhaps most true when seen in the particularly comic looking glass of caricature.

A key element of this looking glass is the humor to be found in the comedy of recognition. A compelling iteration of caricature and its mirror-like qualities comes from sociologist Anton Zijderveld. Humor, for Zijderveld, is a looking glass unto itself insofar as it allows for revelatory glimpses of the world that are nonetheless distorted.57 That is, it allows for comic opportunities to remember, resense, reimagine, and rethink the strange in the familiar, and so to recognize it—with the prefix re- here meaning a simultaneous backward orientation and inclination to do something again and again. Caricature is a rhetorical form of humor that mocks the merits of a looking glass as an accurate reflection of reality. Carnival mirrors reveal imaginary selves made of both material and symbolic realities. Caricature is humorous when it expresses a reality as it could be seen otherwise, when it converts a laughing-at-the-world trope into a laughing-in-spite-of-the-self ethos that offers up an alternative way to visualize follies. The disfigurements in caricature demand that we see differently. The humor in distorted ways of seeing dampens the dark depths that come to the surface in deformed images. No conception of caricature, then, can escape consideration of deformations in visual humor.

It is thus worthwhile to reconsider the metaphor of the mirror through a core rhetorical device that drives the humor in caricature: anamorphosis. Anamorphosis is a protoform of distortive portrayal. An anamorphic image is meant to be looked at from a different perspective, or from some oblique angle (i.e., in a mirror), so that what appears distorted can actually be seen properly. Caricature, as a rhetorical mode of anamorphosis, exploits the comic idea that a viewer accepts the realer Real that can come from a transformation in visual form. It developed as an artistic practice at the school of the Carracci and was coincident with a growing artistic appreciation in the sixteenth century of the comic arts and depictions of the ridiculous. An 1842 edition of the Magazine of Science pegged anamorphic portrayals as “one of those monstrous projections, which, under ordinary points of view, appears extravagantly distorted and ridiculous, yet seen from a particular situation, the picture strikes the eye as one of complete symmetry.”58 The most famous example is Holbein’s The Ambassadors, with its anamorphic skull that seems to wear a smile as if in burlesque resistance to the deformation of human flesh in death. The painting combines Deleuzean nonsense with Erasmian folly. The stability of perspective is torn asunder. Ordinary sense is given over to matters of comic nonsense, even as those very matters are so grave as to deal with the core iconography of death. The haut-goût, or “high flavor,” of regal portraiture is recast as the relish of the ridiculous, with an appeal to the kind of warped imagery that constitutes the humor in caricature.

But anamorphosis does not need to be confined to optical illusions. Holbein’s painting is a distorted projection that entails a sort of “perceptual doubling” to “[produce] a rupture in the viewer’s gaze and [to disrupt] the stability of the object under view.”59 Lyotard calls them curvatures that throw our grand visions back into our faces. I see them as comic burdens on ways of seeing. To caricature is to overload. The Italian verb caricare means “to load” or “to exaggerate.” Both of the Carracci brothers produced a “Sheet of Caricatures” (Annibale in 1595, and Agostino a year prior in 1594), each depicting various ugly figures whose features (both natural and fantastical) are loaded with comic exaggeration. Annibale defined caricature as a “loaded portrait,” more overwrought with reality than reality itself. This is the case for verbal descriptions of folly. It is the case for Fools, the theatrical character of Vice, and the descendants of mimus. It is also the case for caricature and its capacity to, say, capture the ugly images of a “whole body of efforts” for articulating “national culture.”60 Caricature reverberates with the consequences that follow from warped perspectives as they appear in lived realities. Furthermore, it puts the weightiness of the looking glass front and center insofar as the prefix ana– entails a simultaneous movement of something “up” or “forward” in place or time and “back” or “backward again,” the result of which is something seen or made “anew.” The suffix, –morph, refers to the distinctive character of a thing. These are especially illuminating insights when paired with the knowledge that, in botany, anamorphosis names the strange or monstrous development of some aspect of a body. Once again, caricature is monstrous. It burdens ways of seeing. Humor is its morphology.

Seeing the humor in caricature is like seeing the enormities, oddities, and grotesqueries that influence images and ideas about good or bad character. Caricature makes strange truths, or “truthful misrepresentations,” from distortions and deformities.61 These truths pronounce ways of seeing that might not gain prominence in other images or contexts. Caricature, then, offers clarity in the confusion of perspectives, and more specifically in the various viewpoints that are confused (that is, fused in their differences). There is a spectatorial shift from seeing something for what it normally shows to seeing something from different perspectives. Caricature magnifies the view that what is ridiculous from one perspective seems perfectly right, even perversely “true,” from another. The compositional elements of caricature therefore matter a great deal in terms of what they suggest about characters and cultural characteristics—the size of visuals and text, the layout of the picture, the angles and scales, the iconographic choices, and the allure of the artwork itself. This composition creates a congruence of deformed and ostensibly faithful portrayals in the comic space of something like an editorial cartoon or illustration.62 For their humor, what matters most is the fitting misalignment of objects, themes, concepts, beliefs, and other artifacts made manifest in comic imagery.

In so many caricatures of American national character, anamorphic associations between things like people, animals, creatures, and machines are used to re-create realities based on blends of actual histories and imaginations of what could, would, or should be. Caricature lets the pictura comica mingle with the artificiali perspectiva of collective selfhood. This is why, for Kenneth Burke, caricature is grotesque in the worst of ways: it exploits humor by pretending to respect “categories of judgment, even while outraging them.”63 Humor, says Burke, “pits value against value, disposition against disposition, psychotic weighting against psychotic weighting—but it flatters us by confirming as well as destroying.”64 Where Burke sees a problem in humor that goes too far, or flatters too much, I see possibility. An overloaded image can compel a second look at how and why seemingly incongruous elements are actually in accordance with each other. Simply, visual humor in caricature does not convert downward. It makes sense of folly. This is the lesson of Samuel Beckett’s poem that I reference in the epigraph. Matters of character are so troubling, and yet so terribly trite sometimes, because they contain values, beliefs, convictions, and even civic credos that are subject to competing claims of certainty and doubt. Hence Franklin’s drift away from “smooth Words” and toward the comic imagery in crude looking glasses. Beckett’s struggle with words is likewise a struggle with ways of seeing. So is caricature. This makes sense. Beckett himself was impacted by his experiences in the south of France during the Second World War. He once told minimalist musician Philip Glass that it is possible to listen to music and simultaneously look at the image it evokes. The same is true of words, and the same is also true in acts of looking at images and seeing the words—the vocabularies, the grammars, the ideographs, the ideologies, the iconographies, the identities—associated with them. The caricatures featured in this book make sense of American national character in terms of their historical situations in wartimes, with humor about Americanism that is as real as it is ridiculous.

A Glimpse of What Lies Ahead

My study is a chronology of exemplary caricatures that capture images and ideas of national character in war cultures from World War I until the early twenty-first century. Even more, Caricature and National Character relates how humor mingles with rhetorical cultures in wartimes. Two caveats. First, there is no singular character that defines a nation and its people or captures every possible variance. Plainly, no single caricaturist can glean the singular character of a nation, no matter the historical moment. Distribution outlets for caricatures matter. So do ideological predispositions (like those of Western—even Anglo-Protestant—makings, or of a percolating profession of civic faith), not to mention the complexities and conflicts that exist across any number of discourses and among any number of sociopolitical leanings. The study herein features the works of remarkable individuals who foreground the contradictions of national characteristics that get amplified when armed conflict shapes images and ideas of American ways of life. Together, the artworks of exemplary comic artists articulate what Joseph Boskin might call a “comic zeitgeist” just as, following Raymond Williams, keywords can be read as touchstones for talking about larger structures of feeling and experience.65 Other artists could have been studied. There was Laura Brey, Howard Chandler Christy, Harry S. Bressler, Harry Ryle Hopps, and many more during World War I. There was Bill Mauldin and Herblock during World War II, not to mention Native American cartoonists like Eva Mirabal. There is David Levine’s work across the Cold War. And so on down the line of US war cultures, including other Native cartoonists like Ricardo Caté and Marty Two Bulls, Sr., female cartoonists like Etta Hulme, and Black cartoonists like Darrin Bell.66 What unites the subjects of this book is an overwhelming emphasis on caricature as a vital contact point for grappling with core principles of US national character, like Manifest Destiny, civic duty, and good (and bad) citizenship. Caricatures of national character, in this case, situate public engagements with war as the first principle and the last resort of US Americanism. It has mediated collective identifications and disidentifications with ways of seeing selfhood in a distorted mirror, wherein a nation at war can see itself with a sense of humor and so take stock of its own grotesqueries.

Second, while my focus is on humorous characterizations of homegrown images around collective selfhood, I still attend to some of the transnational circumstances that impact competing images and ideas. The image of the United States on the world stage overlapped with Revolutionary sentimentalism, sectionalism, and white supremacy in the Civil War period. During World War I, international alliances were often pegged as pillars of the fight to save the world for American-styled democracy (despite the rampant and countervailing forces of nativism and interventionism). The Second World War, too, saw the United States shrinking in the shadows of isolationism before FDR’s hearts-and-minds rhetoric made the international campaign against totalitarianism a nationalistic rendezvous with Manifest Destiny. Throughout the Cold War, foreign adversaries were constantly compared to those in the minority classes seeking freedoms at home, both by domestic commentators and critics looking from the outside in. Many of these adversarial perspectives endure in the specters of America First jingoism, White Nationalist nostalgia, and patriarchal war mentalities today. In each wartime, certain characteristics of Americanism can be identified in the comic play of rival nations, contradictory distortions of civil rights and civic duties, and powerful appeals to the strange truths of character that crop up in the totalizing fictions of caricature. Consequently, the caricature artist stands as a sort of cultural representative for distilling the crises in national character that are catalyzed by armed conflict and attendant cultural warfare. I read caricatures from a rhetorical vantage while relating those readings to the contexts and conjunctures of which they are visual articulations. The result, I hope, is a transhistorical look at a characterology of US wartime public culture as it appears in and through humorous caricatures of how to live out the American creed.

I begin with the First World War. Much of the in-fighting over the nature of Americanism at this point was reoriented toward a mode of Americanization that might facilitate a countrywide inculcation of ideal citizenship. From Allied victory to what Tom Engelhardt terms “victory culture,”67 and then again from the rise of defeatism and despair during the Cold War to the regeneration of triumphalist mindsets in the War on Terror, caricature provides opportunities to take pause and reconsider how founding principles thrive on tensions between both monstrous and magnificent pictures of nationalistic virtue. It dwells on distorted reflections of patriotism as the last refuge of the scoundrel. In the fog of war, appeals to national character are a sort of American version of the Angels of Mons protecting the body politic. Caricature is a comic demon “[holding] up to God and his creatures the mirror wherein universal individuality dissolves.”68 In the looking glass of caricature is the comic dissolution of national character.

This book unfolds as follows. Chapter 1 considers conceptions of civic duty in the comic underbellies of James Montgomery Flagg’s renowned “I Want YOU” poster. Moving away from conventional notions of Uncle Sam as the catalyst to a groundswell of support for the Great War, or of Flagg’s infamous poster as purely and simply about American patriotism, the first chapter approaches Uncle Sam’s personification of the United States (and the government besides) as a caricature of the nation-state. Uncle Sam is read as a sendup of state-sanctioned “good” character who makes a mockery of US Americanism when his temptations to war footings are coupled with a glaring sexual humor that is unapologetic in its enticement to serve.

These temptations and enticements are rendered even more weirdly and more eerily hawkish in the transmogrifications of some early works by Theodor Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss. The second chapter examines how Dr. Seuss put his familiar quirkiness and affinity for human-animal imbrications to work during the Second World War in over four hundred editorial cartoons (published in the popular leftist newspaper, PM). Uncle Sam figures prominently in Dr. Seuss’s PM caricatures, which pursue a view of true American character through revisions to tried-and-true national iconography, but even more so through humor in iconography that juxtaposes eagles with ostriches, valiant friends with enemy vermin, and phantasmagoric war machines with all their grit and grime. Dr. Seuss’s caricatures constitute a comic abstraction of national character as seen through the looking glass, dirtily, and with a mode of defacement that uses comicality as an ethos to judge the Self. Chapter 2 takes up the Americanism in Dr. Seuss’s ridicule of US neutrality, his mockery of pacifism, and his lampoons of the flimsy civic principles for democracy that seem to slacken in the face of self-defense.

That Dr. Seuss’s wartime caricatures also relied heavily on racial stereotypes and ethical gray areas makes my turn to Ollie Harrington in chapter 3 all too necessary. Like Harrington, both Flagg and Dr. Seuss homed in on what they saw as the laughable qualities of anyone proclaiming to embody an American character without responding to a call of civic duty. But while Dr. Seuss and Flagg took US goodness for granted in their pleas for political action, Harrington picked apart various discriminations and oppressions as what he came to define as the “hilarious chaos” in his wartime caricatures, many of which appear under the heading “Dark Laughter.” Harrington’s work spans from World War II all the way to end of the Cold War. I focus on a collection of those from the Pittsburgh Courier and the Daily Worker (eventually renamed the Daily World) in the early 1960s through the mid-1970s. This body of editorial cartoon artwork showcases the civic ills plaguing the lives of Black children on the home front and shows just how much the peculiar tensions between the maturation and decay of American character across the Cold War are so much more potent when they are humored by a Black children’s crusade.

The last chapter turns to Ann Telnaes. Like Harrington, a victim of McCarthyism and a self-exile who spent the bulk of his career overseas either in Paris or in East Germany, Telnaes embodies the outsider looking in.69 Telnaes is an independent cartoonist and Swedish-born emigrant who has made a career of coming to comic terms with prevailing attitudes about race, ethnicity, religion, gender, and class in the United States. For Telnaes, all wars are culture wars just as all cultural warfare is about rhetorical claims to civic identities. Chapter 4 begins with a look at some of Telnaes’s caricatures from the exhibition Humor’s Edge, which ran from June 3 through September 11 in 2004. The exhibition features the works that earned Telnaes a Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning, originally appearing in publications like the Washington Post, the New York Times, and the Chicago Tribune. However, while her work became prominent during the George W. Bush administration, it has become perhaps even more potent since the rise of Trumpism. What many critics and commentators disparagingly refer to as “Trump’s America” is driven by a president who embodies American character as if it is a Churchill-like campaign of “ungentlemanly warfare.” President Donald J. Trump is a lightning rod for recurrent themes in US Americanism of racism, sexism, misogyny, bigotry, and hypernationalism. In discourses and scholarship about rhetorical presidentialism, the president is often seen as the American character. Telnaes utilizes caricature as a way of seeing Trump as the figurehead for an imperial presidency but also as the culmination of perverted democratic (never mind Constitutional) principles. The final chapter of Caricature and National Character therefore takes up Telnaes’s comic imagery of King Trump as a means of understanding how US American national character in the early twenty-first century seems to amplify warfare itself as a principle of political conduct, from trade wars to actual armed conflict, and then again from newfangled culture wars at home to outmoded notions of neo-isolationism. This is a troubling, yet telling, principle on which to conclude, if for nothing more than its recollection of the idea that democracy—whether stretched to its principled limits or pushed to the end of its lines—is potentially riven by its reliance on a peaceable bellum omnium contra omnes, a war of all against all.

It is important to note here that comic images do not necessarily make for “good” visions. In fact, caricature is oftentimes a vicious means of amplifying normative perspectives on selves and others, reinforcing rather than evacuating “stereotypes, prejudices, and narrow horizons.”70 It is also not always a picture or portrait. Sometimes it is a logic of representation, as it was in the containment culture of the Cold War with its officious, and at times official, caricature of East-West relations. To take a caricature seriously is therefore to look carefully at different perspectives as well as perspectives in difference. Additionally, to become a caricature, or to act as if another character is a caricature in the flesh, is to, well, humor its limits. The stakes of engaging caricatures of wartime national characters are so high because to study war culture is to see these limits in “the visual construction of national identities through the mythologies that are mobilized to sustain them and to suppress other ways of seeing.”71 In this sense, even “new” images can reinforce “old” perspectives. In this sense, too, Telnaes rounds out a comic tradition in US American humor not only of utilizing caricature to articulate national character but also to consider the very democratic underpinnings of the human condition—or, the Human Comedy. The artfulness of caricatures and their embroilments with ideas of US national character during times of war demonstrate the ways in which pictures can become Pygmalions, and then again personifications that impact real-life experiences.72 Caricature, in other words, is most dangerous when humor is evacuated from its take on a situation. This book therefore concludes with a rumination on the idea that wartime caricatures goad us not to dwarf the magnitude of national character but rather to dwell on its details, especially when even the most comic of situations turn dire. After all, the visual humor of caricatures can actually provoke a rhetorical laughter that lets us put our ugliest expressions and enactments of collective selfhood back together with the very burdens of good and bad character that might otherwise stay omitted, if not go without seeing.