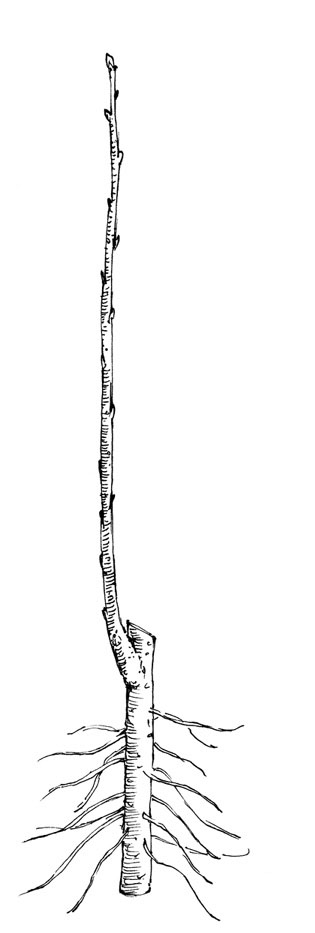

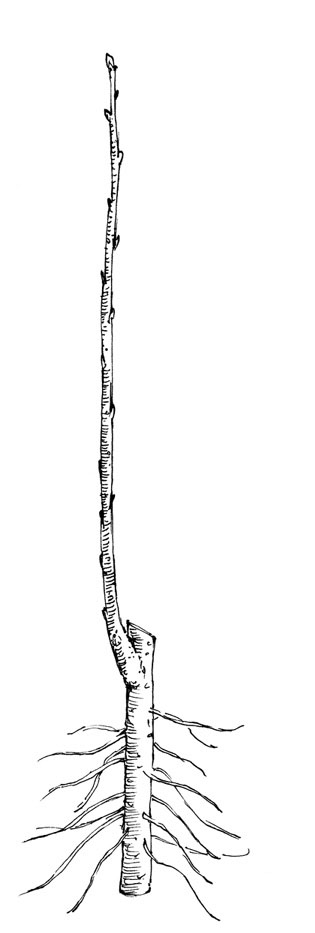

Figure 7.1

Whip.

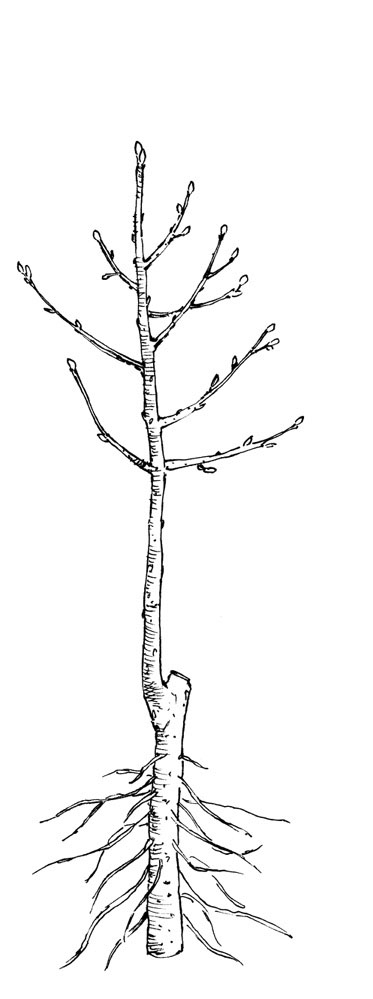

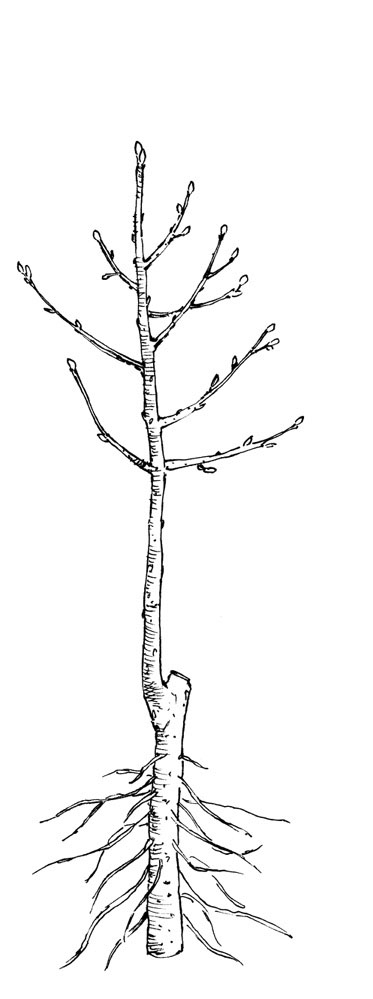

Feathered planting stock for orchards.

We have reached the stage where it is time to order trees for planting. By now, you have carefully evaluated your site, corrected drainage and nutrient problems, designed and laid out your orchard or evaluated your existing orchard layout, and picked out crops and varieties. The next steps involve purchasing high-quality plants, caring for them before planting, and setting them into the ground.

If you have a large orchard, you will likely buy your trees from specialized wholesale nurseries. Ask other fruit growers, fruit-growing organizations, fruit specialists at universities, and Cooperative Extension and Provincial offices for referrals. You want to make sure that you deal with nurseries that you can trust, not only to provide quality trees, but also expertise in fruit tree care during and after the purchase.

Homeowners have the options of buying from local retail nurseries or purchasing from mail-order companies. Here I cannot overemphasize the importance of dealing with reputable nurseries experienced in working with fruit crops. Ask other fruit growers, Master Gardeners, or local fruit specialists for referrals of nurseries you can trust. This goes for local nurseries as well as mail-order companies.

Avoid the temptation to save a few dollars by buying at big chain stores. At such places, you will rarely find salespeople skilled with tree fruits, and chances are great that you will end up with varieties and rootstocks unsuitable for your area. Instead, try to purchase only from well-known nurseries that specialize in growing the fruits you are interested in and that work for your climate. You are generally better off avoiding nurseries that offer everything from vegetables to ornamentals to fruits to herbs. Fruit growers in Florida are likely to deal with different suppliers than those in Manitoba, simply because of dramatically different climates. Avoid nurseries that sensationalize or exaggerate plant descriptions. If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.

Before purchasing your trees, you should have a clear idea of the varieties and rootstocks that you want. Be firm and shop around, if necessary. Do not allow yourself to be pressured into buying varieties or rootstocks that you do not want. You may find it necessary to make some compromises, as varieties come and go in the nursery trade and not all the varieties and rootstocks that you want may be available. When you select your alternate trees, however, make sure you purchase something you like and that will perform well in your orchard. Don’t buy plants simply because a nursery is overstocked on that item or is sold out of what you want.

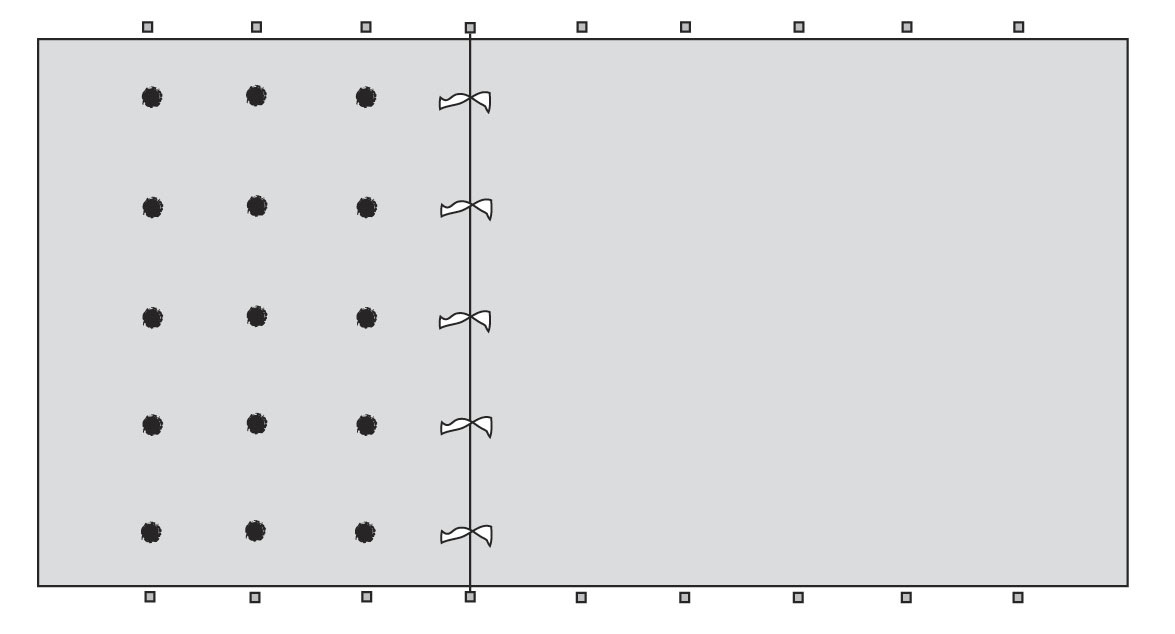

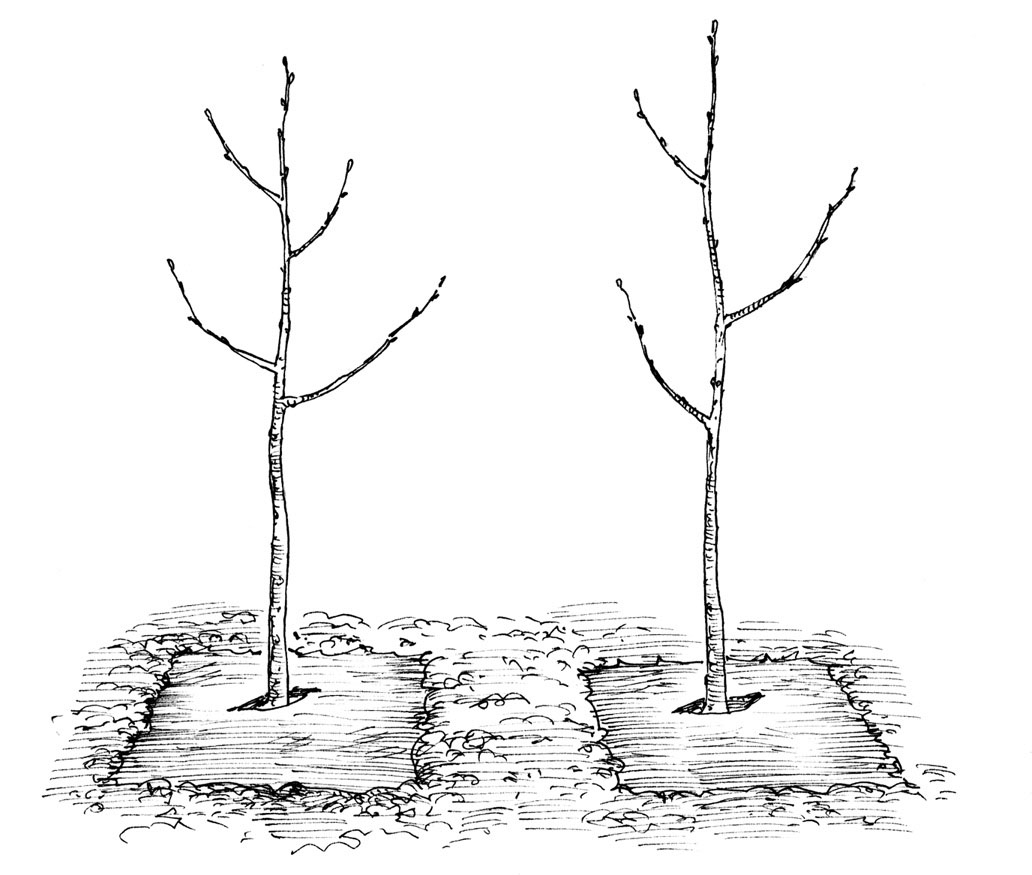

Fruit tree planting stock for commercial orchards and from mail-order nurseries is usually sold as unbranched (whip) or branched (feathered), bare-root trees that have been dug from fields and had the soil shaken from the roots (see figure 7.1). Depending on the crop, these trees are about 3 to 6 feet tall. They are usually dug in the fall, stored in refrigeration over the winter, and shipped for spring planting. Particularly in warmer climates and for some crops, the trees or bushes may be planted in the fall or dug and shipped in the spring.

Whip.

Feathered planting stock for orchards.

Whips were once favored by commercial growers who wanted to choose the locations of the main scaffold branches for themselves. Particularly for apples and pears, feathered planting stock has become much more popular and works well with high-density plantings and axis training systems that avoid permanent scaffold branches in favor of small, short-lived fruiting wood that is replaced frequently. Not having to head back a whip to stimulate lateral branch growth can save at least a full year in getting to market with the new training systems.

When ordering bare-root trees, arrange to have the nursery deliver them as close to planting time as possible. Bare-root trees are highly perishable unless stored at temperatures around 32 to 38°F (0 to 3°C) in high humidity. By carefully timing the shipment and being ready to plant as soon as the stock arrives, you will save yourself the many headaches involved in storing planting stock.

If you cannot plant immediately upon delivery, arrange to have the planting stock placed into cold storage. The roots will probably be packed with damp shredded paper, sphagnum moss, or shredded wood fibers and wrapped in plastic film. Be sure to keep the materials and wrappings in place to prevent the roots from drying out.

If cold storage is not available, remove the plastic film and bury the roots and several inches of the lower trunks in damp sawdust or compost. This process is called “heeling” and prevents the roots from drying out. If the trees have broken dormancy and the buds are swelling or leaves are developing, protect the trees from freezing while they are heeled in.

Planting stock in local retail nurseries is often sold in containers. In many cases, the planting stock is purchased by the nursery as bare root and stuck into containers of potting soil for resale. You pay a premium for containerized trees, their chief advantage being convenience. You can allow the trees to remain in the pots for several months or more before planting, if necessary, without having to provide refrigerated storage. Containerized trees are also generally larger than the bare-root trees favored for commercial planting. Smaller orchard crops, such as bush cherries or saskatoons, are typically grown in pots and shipped with or without the containers enclosing the root balls. Again, the container-grown plants give you flexibility in deciding when to plant.

Containerized trees are generally easier to store than bare-root trees. If the trees have been kept outdoors in their containers at a nursery near your site, you can probably continue to leave the plants outdoors until planting. If, however, your site is still experiencing freezing temperatures and the trees are coming from a milder climate and have already broken dormancy, protect them against freezing temperatures. Even for the most cold-hardy varieties, buds that are close to breaking and emerged leaves and flowers can be killed at temperatures of about 29°F (−2°C) or less.

For example, your orchard might be located in Missoula, Montana, and the planting stock comes from a nursery in a coastal or southern region. You may still have snow on the ground with temperatures below freezing when the trees arrive, already leafed out. Exposing those trees to your subfreezing temperatures could damage or kill them. In such a case, protect the trees against freezing. Generally, they can be kept in cold storage at 34 to 40°F (1 to 4°C) for several weeks without serious problems. For orders of just a few trees, consider potting the trees up and leaving them inside an unheated garage or porch. For all kinds of planting stock, keep the roots moist but not soaking in or saturated with water.

Some planting stock is now grown in fabric root bags with either soil-filled root bags buried in the ground or bags filled with potting soil supported above the ground. These bags are made of the same material used for weed barrier fabrics and confine the roots within the bags. Some types of bags effectively prune at least some of the roots where they contact the fabric, thereby creating a dense, rather fibrous root system that will establish well once planted. Be aware, however, that root circling within root bags is not uncommon. Sometimes one or two roots penetrate the bags and most of the root system develops outside of the root bag, where it is lost when the plant stock is lifted from the nursery.

Be sure to examine each root ball at the time of planting. You should see an evenly distributed network of fine roots all around the outside of the root ball. Reject those with large, circling roots that will provide poor anchorage and possibly cause girdling later on. Also reject those with large roots that have penetrated the bag and been cut off.

When planting containerized trees, remove plastic containers completely before setting the trees into the ground. While this might sound absurdly simple, my colleagues and I are often called out to examine dead or dying plants only to discover that the plants were set into the ground pots and all. With no way for the root systems to grow, the trees soon die. For fiber pots, the situation is less clear. Some fiber pots quickly degrade in the soil and allow the roots to penetrate, while others do not. I recommend removing fiber pots completely, if at all possible. At the least, remove four wide, vertical strips of the fiber pot material around the sides of the pot and make an X-shaped cut across the bottom of the pot, penetrating into the root ball. When planting root-bag trees, always slit the root bags on several sides and strip away and remove all of the fabric as the trees are set into the holes. This practice is different from that used for ball-and-burlap landscape tree planting stock, where the burlap is usually left partially or completely in place. Tree roots can penetrate burlap to form healthy, well-distributed root systems. The roots cannot penetrate root-bag fabrics. If your trees come planted in plastic film bags, be sure to remove all of the film before you plant. Take care to disturb the root balls as little as possible when planting.

Fruit trees that are dug with the root balls intact and enclosed in burlap are sometimes used for small plantings where large trees are wanted quickly. This technique is called ball-and-burlap, and the burlap-wrapped root balls may or may not be supported with wire baskets.

Keep the root balls buried in moist compost, sawdust, or wood chips for short-term storage and plant as soon as possible. While they are in storage, keep the root balls moist and apply a liquid fertilizer weekly if the trees have broken dormancy and begun forming leaves and flowers.

Handle the trees very carefully, and do not allow the root balls to be dropped, shaken, or otherwise damaged. Lift the plants by the bottoms of the root balls and never by the trunk or stem. Pulling on or twisting a trunk will break many small roots within the ball and can stunt or kill a plant. Once the root ball is gently placed in the planting hole, remove any twine or other ties around the trunk and peel the fabric back away from the trunk for at least several inches. Slit the fabric vertically at least four times around the root ball. Do not remove the burlap fabric or wire basket; trying to do so often damages the root balls and can stunt or kill the trees. Research has shown that the roots easily penetrate the burlap and grow through the wire basket openings.

Before planting, you should have your irrigation system in place and operational, as well as trellis poles and anchors (see chapter 12). If your site is susceptible to pressure from moose, white-tailed deer, or other herbivores, strongly consider installing an herbivore fence before planting your trees or bushes (see chapter 11). This is the only effective method of keeping herbivores out of an orchard in areas where the animals are abundant.

In chapter 4, we went into detail on how to prepare the field and lay out planting blocks. Now we need to mark the planting rows within those blocks. Two methods are commonly used to mark planting rows: you can stake out rows by hand, or use a tractor. For small orchards, choose one side of the planting block that will be parallel to the tree rows. Using this line as your reference, measure along the adjacent ends of the planting blocks and place stakes at what will be the ends of each row. For example, say you want a 12-foot row spacing. Starting at the corners of the block and following the marked end lines, place a stake every 12 feet along both end lines. Depending on your design, you might want to locate the first row 6 feet from the side of the block and the second and all other rows at 12-foot spacings. Stretch a measuring tape or marked rope between corresponding stakes and set stakes or flags to mark where you want the trees within rows (see figure 7.2). Tying knots or flags in a rope as long as the orchard block simplifies this process (figure 7.2). Ensure the knots or flags are the same distance apart as you want your trees.

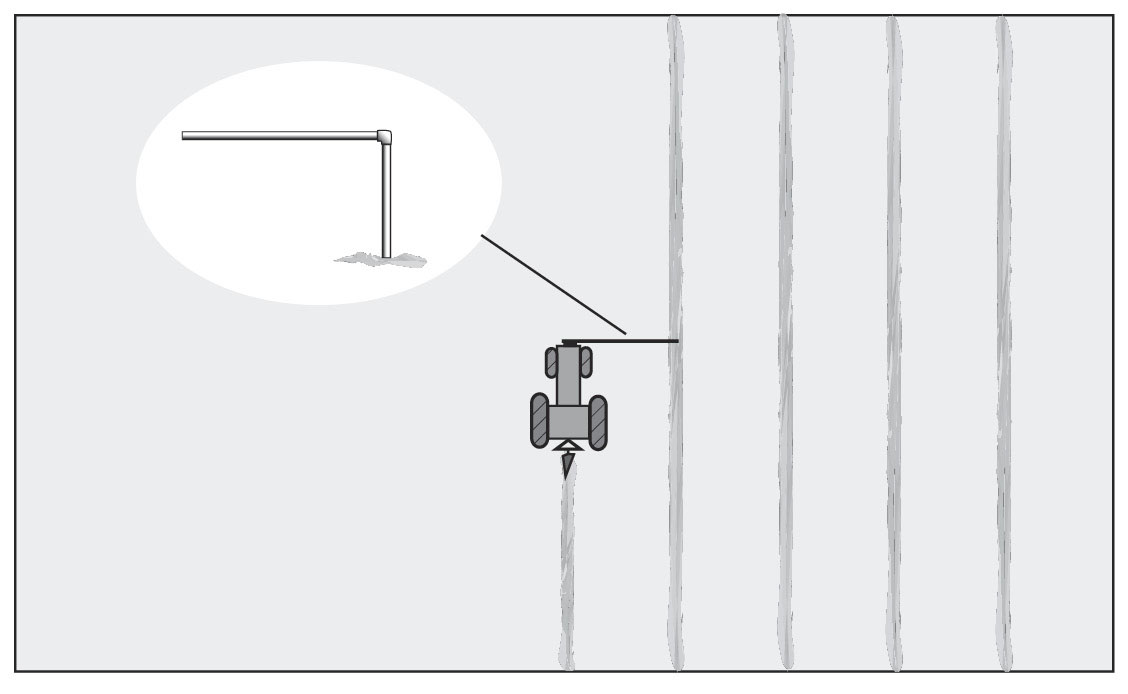

For larger orchards or where the tree lines follow a curve, obtain a plastic pipe or metal electrical conduit a few feet longer than the desired distance between rows and fasten a short pipe at a right angle to one end (see figure 7.3). Fasten the other end of the pipe to the front end of a tractor. The pipe should extend the length of the desired between-row spacing. Equip the tractor with a small plow blade, shank, or coulter wheel attached to a tool bar and centered on the back of the tractor. By centering the outer end of the pole over the reference line for the block, you create a furrow in the field marking the first tree row. Repeat the procedure using the furrows you make as reference lines.

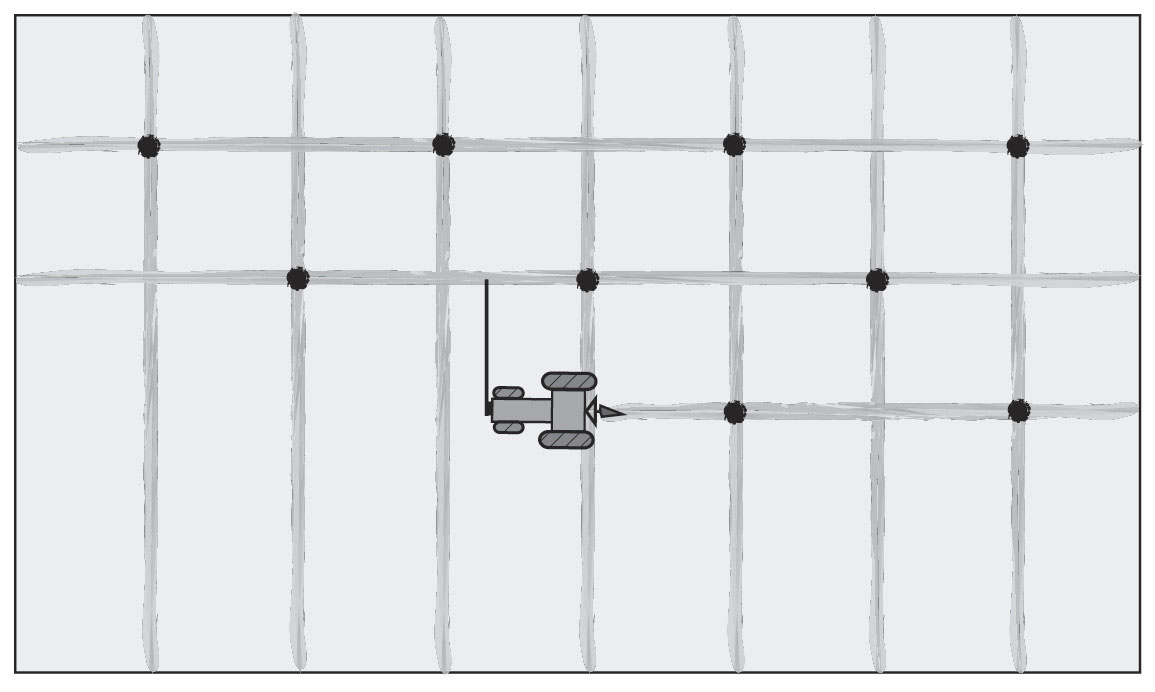

Use stakes or flags to mark the ends of the tree rows along the sides of the planting block. Using a rope longer than the length of the tree rows, tie knots or flags the distance apart that you want your trees planted. Pull the rope tightly between corresponding stakes along the ends of the planting block, and use stakes to mark the location for each tree in that row. The trees can be set in a square grid (as shown here) or offset (figure 3.7).

You can use a measuring tape or flagged rope, as described above, to mark planting hole locations within the rows. A wooden pole or section of PVC pipe cut as long as you want the trees apart is also a convenient way to measure between planting holes. This technique works particularly well in high-density plantings where trees are closely spaced within rows.

When the trees are spaced more than about 12 feet apart, you can use the tractor and reference bar method to locate the planting holes. Set the bar length to mark one-half the desired in-row spacing, place the reference point of the bar over a block-end reference line, and plow at right angles to the planting rows (see figure 7.4). Mark every other furrow intersection point in each row with a flag or stake. This design creates a triangular planting that maximizes the distance between trees in adjacent rows.

Install a chisel or narrow-furrow plow to the toolbar on the tractor. Attach a spacing rod that extends from the front center of the tractor the distance that you want the tree rows apart. Lightweight metal electrical conduit or rigid PVC pipe works well. A 90-degree extension (see inset) that reaches nearly to the ground at the outer end of the spacing bar is helpful in keeping the rod centered over reference lines. Keep the end of the spacing rod centered over the reference line you established earlier along the edge of the planting block and plow along the tree rows. Then use the tree row you have made as a reference line and repeat.

When planting only a small number of trees, a hand shovel works very well. For larger numbers of trees, a tractor-mounted auger will be highly desirable for most sites, except those too rocky for augers to be used effectively. In extreme cases, a small backhoe may be used. In all cases, dig the holes on the centerline of the planting row and be sure the holes are evenly spaced within the row. As the trees mature, uneven rows and poorly spaced trees will make access difficult and increase management problems.

Lay out the tree crop rows as described in figure 7.3, then adjust the spacing bar for one-half the distance between trees within rows. Use one edge line of the planting block as a reference line and plow a furrow. Every other intersection of this new furrow with the tree crop rows is the location for planting a tree. Staggering the planting hole locations in adjacent rows creates a triangular tree layout that maximizes the distance between trees. Repeat using each new furrow as a reference line.

However you dig them, make sure the holes are large enough to place the roots inside without bending any of the roots or crowding them together against the sides of the hole. In most cases, planting holes 18 inches in diameter and 18 inches deep should suffice. Ball-and -burlap trees will require larger holes. If in doubt, measure the root balls or spread of the bare roots, or contact the nursery you are buying from before digging the holes. Have a shovel on hand during planting to make any necessary adjustments to the hole dimensions. Do not prune roots or cut down root balls in order to fit them into a hole. Instead, make the hole wider. When planting large numbers of trees, you may find it helpful to have the holes dug before the trees arrive from the nursery.

Use a hand shovel to break away any smooth, compacted layers on the sides of the holes (glazing) before setting in the trees. Glazing is most likely to occur when soils are wet, contain large amounts of clay or silt, and when an auger is used to dig the holes. The dense, smooth glazing can inhibit root growth and interfere with water movement.

Make the holes deep enough to set the plants at the same depth as they grew in the nursery. Planting too deep or too shallow can stunt or kill plants. Because the soil and the trees will settle somewhat in the planting holes, you may choose to plant trees slightly shallower than they grew in the nursery. In some cases, trees with interstems are planted deeply enough to place the lower graft union at or slightly below the soil surface. When using this strategy, use only trees that have had the interstem grafted very low on the rootstock so as not to plant too deeply.

A common recommendation is to form a firm, cone-shaped mound of soil in the bottom of the hole to drape the tree roots over. This strategy works well for bare root trees and small plantings. The idea is to set the tree roots on the cone and backfill the planting hole, evenly distributing the roots around the hole and providing maximum support. When planting hundreds or thousands of trees, however, the method is usually too slow and labor intensive to be practicable. Holes for containerized or ball-and-burlap trees need to be just deep enough to receive the root ball and maintain the height at the same depth the tree grew in the nursery. You can make the holes wider, however, so that you can make adjustments to the plant’s location.

Years ago, fruit specialists sometimes recommended pruning the roots and tops of newly planted trees to “keep them in balance.” We no longer make that recommendation. Prune bare roots only if they have been broken during digging or shipping. Never prune roots simply so that they will fit into a planting hole.

Dealing with girdling roots. For container-grown plants and some plants grown in root bags, circling roots can form around the outsides of the root ball on plants left too long in the containers. A few roots circling partway around the outside of a root ball do not cause any problems. In such cases, use a very sharp utility knife to make two or three slices down the sides and a cross on the bottom of the root ball. If in doubt, wash the soil gently away from the roots of a plant or two. I have found plants where the roots developed first in coils about 4 inches in diameter and later in coils about 6 inches in diameter. In these severe cases, the plants had been rootbound in 4-inch starter containers before being transplanted to 1-gallon containers and again allowed to become rootbound. If severe root circling is present, document what you have found with photos and reject the shipment. Trees with circling root systems will never anchor properly and may eventually die due to the roots girdling one another or the main trunk.

You may have heard of a practice called “butterflying,” where the planter attempts to salvage rootbound container-grown plants by splitting the root ball with a shovel. At best, rootbound plants treated this way will be slow to establish and may well be stunted their entire lives; in many cases, plants will simply die. If your plants are so rootbound as to need the root balls split, discard the plants and obtain healthy planting stock.

Checking for pests and diseases. If you see evidence of diseases or pests on the roots, collar, or trunks, stop immediately. Disease and pest symptoms include tumor-like swellings, cankers, brownish or black discoloration, stubby roots, swollen root tips, borer holes on trunks and stems, and the pests themselves. Do not plant infected or infested trees. Contact the nursery immediately and provide them with photos, if you can, of the affected tissues. Planting infected or infested stock not only ensures that you will have at least one problem tree; it can also introduce very serious pests and diseases into your orchard. Plant only healthy, pest- and disease-free trees.

Keeping roots moist. During the planting process, keep bare roots and root balls moist at all times. For bare-root trees, bring out of storage no more trees than you can plant in an hour or so and keep the roots covered with wet burlap sacks or similar materials. People sometimes recommend placing the roots inside a bucket of water before planting. If you have kept the roots properly moist, this step should not be necessary, and extended immersion can damage or kill roots.

Mycorrhizal fungi (mycorrhizae) are naturally occurring, soil-dwelling fungi that form associations with plants by colonizing the roots and spreading fungal strands (mycelia) into the soil. The fungi benefit from receiving carbohydrates and other biochemicals from the roots. In exchange, the mycorrhizae greatly increase the effective root surface area and increase uptake of water and nutrients. By colonizing the root surface, the mycorrhizae also help exclude and protect against harmful microbes, including certain root rot fungi. Trees with mycorrhizal associations will generally be more drought-tolerant and require less fertilizer than trees without mycorrhizae.

Types of microorganisms. Many different mycorrhizal types and species exist and your soils probably already contain healthy populations. If your soil has been damaged by fumigation, neglect, or poor management, however, your trees may benefit from adding mycorrhizae. Otherwise healthy sandy soils can also be deficient in mycorrhizae.

Endomycorrhizae are the most useful for fruit trees and many other crop species. These species of fungi penetrate into the root cells of the host plants. Mycorrhizal products sold for fruit growers and other organic producers typically include one or more of the following endomycorrhizae (Glomus species are the most common endomycorrhizae found in commercial products):

Ectomycorrhizal fungi live on the outside surfaces of host plant roots. While ectomycorrhizae have a much smaller range of plant hosts than endomycorrhizae and are not generally considered beneficial for fruit trees, they may be included in blends with the endomycorrhizae species listed above. Ectomycorrhizal species found in commercial mycorrhizal blends include:

Ericoid mycorrhizae are beneficial for blueberries, huckleberries, lingonberries, rhododendrons, and other acid-loving plants. They are not useful for the crops described in this book.

Choosing products. When purchasing a mycorrhizae product for your orchard, keep the following two strategies in mind. First, deal with companies that specialize only in microbial products, rather than general garden products. There are many commercial mycorrhizal products sold, not all of which are effective; deal with someone who really knows mycorrhizae. Second, don’t buy any mycorrhizal product that does not list the species included and the spore count. If you do not know what is in the product, you have no way of knowing if it will benefit your orchard. The same caution applies to spore count. The higher the spore count, the more concentrated and effective the product will be. If the species included in the product and spore count are not specified, be very skeptical of the product. Don’t be lulled by advertising “testimonials.” There are very good products on the market; it’s worth taking the time to find them. Before using any microbial product, ensure that it can be used by certified organic growers in your area.

A product that blends at least several species of endomycorrhizae is usually preferable to a product with a single fungal species. More species means that it will be adaptable to a wider range of soils, host plants, and growing conditions. Again, endomycorrhizae are much more likely to benefit fruit trees than ectomycorrhizae. For root dips and root ball drenches, purchase only mycorrhizal inoculants. Products that include both mycorrhizae and fertilizers can damage the roots and are not recommended at the time of planting. These combination products are best applied after the trees are planted.

Treating the plants. The best way to treat bare-root plants is to dip the roots into a slurry containing desirable mycorrhizae just before planting. For container-grown or ball-and-burlap trees, drench the root balls with water containing mycorrhizae. Follow the product label directions.

Certain bacteria can also be valuable as a root treatment at the time of planting. Crown gall is a bacterial disease that causes tumor-like galls on the roots, collars, trunks, and stems of many species of woody plants. The disease is caused by Rhizobium radiobacter (formerly known as Agrobacterium tumefaciens), which dwells in the soil and can exist without a plant host for many years. The disease is usually spread to uninfected fields on infected planting stock or on soil particles carried from an infected field on equipment, runoff water, or feet. Certain closely related but nonpathogenic bacteria can protect against crown gall by colonizing the roots and excluding the disease organism. Dipping the bare roots into a slurry containing Rhizobium (Agrobacterium) radiobacter strains K84 or K1026 immediately before planting can provide good protection for at least the first year and help the plants become well established. Be sure that the product you use is registered for certified organic growers and for your state or province.

As we discussed in chapter 4, if you are going to add an amendment such as compost, peat moss, or other organic materials, with the exception of phosphorus, it is best to add it to the planting row or the entire orchard rather than to the planting holes.

Adding amendments to planting holes can create very serious problems and should never be used for fruit trees and bushes. The rule of thumb is that the only thing besides the roots that goes into the hole is what came out of it in the first place.

Add amendments throughout the planting row or entire orchard and till them in 6 to 12 inches deep. For bush fruits, you may obtain satisfactory results by amending only the planting row. Fruit trees have much larger root systems that quickly grow far beyond the planting row. Once the amendments have been applied and tilled in, mark the planting rows, dig the holes, and set the trees. You gain all of the benefits of the amendments and avoid the problems. The amendments will be available to the growing root systems as the orchard crops mature and to the roots of alley crops and companion plants.

In soils where available phosphorus is deficient, you can add phosphorus directly to the planting hole before setting the trees into place. This is also a good strategy on soils with pH below 6.0. For organic growers, add one or two handfuls of steamed bonemeal to the bottom of the planting hole, cover the bonemeal with 2 inches of soil, and set the trees in place. This can help maintain the plants until the root systems become well established. Bonemeal will not damage the plants. Never add materials that contain nitrogen, potassium, or boron to the planting holes.

Once the holes are dug and you have pruned off damaged roots and treated the roots with beneficial mycorrhizae and radiobacter organisms, set the roots or root balls gently into the planting holes at the same depth as or slightly shallower than the plants grew in the nursery. Start backfilling the planting hole in shallow layers, firming each layer with your hands, until the hole is filled. Remember to backfill using only the material that came out of the hole and avoid the temptation to tramp the soil into place with your feet. The unfortunately popular “death stomp” can severely damage roots, especially bare roots. Once the hole is filled, you can gently walk around the plants to firm the soil in place.

A common practice is to create shallow bowls of soil around newly planted trees to catch rain and irrigation water. On soils that are well drained to excessively well drained, the practice can be helpful. On heavier soils or where drainage is otherwise poor, the tree basins can create saturated soils around the roots and increase the chance of root disorders and diseases. Tree basins are most likely to be used for very small plantings where the trees are irrigated individually by hand. Where overhead or drip irrigation is used, tree basins are likely to cause more trouble than good.

Once the trees have been set and the soil firmed around the roots, an excellent strategy is to irrigate heavily to settle the soil around the roots. This practice helps eliminate air pockets around the roots that can cause the roots to dry out. After irrigating, check to see that the plant is at the same level at which it grew in the nursery and adjust the depth, if necessary.

Depending on crop, rootstock, and training system, you may now need to stake or trellis the trees, as we will discuss in chapter 12. Not all trees need staking or trellising, however. Unfortunately, the current trend, particularly in the landscape industry, is to stake every newly planted tree and then tie it down with enough rope for the last roundup. There seems to be a fear that the trees will somehow escape.

Larger ball-and-burlap and containerized trees can be top-heavy and may benefit from temporary staking to prevent them from falling or blowing over, even if they will eventually be freestanding. In these cases of freestanding trees, the usual procedure is to use three evenly spaced wires staked to the ground, each separated by 120 degrees. The wires are looped around the tree trunk just above a branch to keep the loop from slipping down the trunk. Rubber hose is used to line the loops and protect the trunk from damage due to rubbing. When staking trees in this fashion, keep the loops loose enough to allow the tree to move in the wind several inches in each direction. That motion forms the reaction wood that will give the trunk strength and allow it to eventually stand on its own.

Even small trees destined to be freestanding are sometimes staked in order to form straight trunks. Likewise, trees that will be trained to tall spindles and other axis systems are often trained to poles, even if only temporarily. Metal tree stakes, bamboo poles, metal electrical conduit, and PVC pipe all serve as excellent temporary training stakes, depending on the height that you need. Fasten the trees to the stakes using wide tape designed for tying trees and grapes. Avoid zip ties, wire, fishing lines, and thin cords, as these cut into the bark. Check the ties frequently and loosen them, as necessary, to prevent girdling the trunk.

For trees that will be trained to trellis wires, some growers prefer to avoid the use of stakes or poles, largely due to cost, and tie the trees directly to the trellis wires. In such cases, the lowest trellis wire is usually no more than 2 to 3 feet above the ground. Special wire clips that surround the trunk and clip to the trellis wire are available from nursery supply companies. These clips allow you to quickly and securely support the trees on the trellis wires and are a marked improvement over tying.

For trees that are to be grown on poles or trellises, whether to install the support posts and wires now or later depends on the training system and size of the trees. In general, it is best to train the trees early. Straightening a bent trunk or developing a new scaffold limb on an older trunk can be challenging. Within reason, the sooner you can get the trees trained, the quicker the tree will produce and the fewer problems you will have correcting badly trained trees.

If you are training the trees to posts, such as with the slender spindle system described in chapters 3 and 12, you can plant the trees and set the posts at the same time. When the tree support posts are metal pipes or T posts that will be driven into the ground, rather than buried, the posts can be driven in after the trees are planted, taking care not to drive the posts through the root balls.

For most orchard crops, the critical steps following planting are to keep the soil moist, control vegetation around the trees and bushes, and control pests and diseases.

Depending on the crop and training system, you may also head back newly planted trees to encourage scaffold limbs at a particular height and may begin summer pinching on whips and feathered trees as you select and develop scaffold limbs or fruiting wood. For slender spindle and axis systems, you will need to begin tying trunks and lateral branches to trellis wires and poles. For all tree crops, use clothespins, weights, and/or spreader bars to bend down branches and develop wide branch angles. The latter step, alone, greatly adds to a tree’s strength and health. These steps are discussed in detail in chapter 12.

Regardless of the irrigation system used (see chapter 2), the goal is to keep the soil moist, but not saturated, throughout the root zone. A common tendency is to overirrigate newly planted trees and bushes. As long as the soil is moist, no irrigation is needed. Use this strategy throughout the planting year and the year following planting, while the root systems are establishing. By the third year, the root systems should be extensive enough that irrigation can be reduced somewhat.

Plan on keeping the planting rows free of vegetation for at least the planting year and following year (we’ll go into orchard floor management in detail in chapter 9). Eliminating competition during the critical establishment stage greatly increases tree survival and growth.

Mulches and weed fabrics. Now that your trees are in the ground, you are faced with complicated decisions on whether and how to apply organic mulches and weed barrier fabrics, or to keep the soil surface bare. Each strategy has its advantages and challenges.

The first factor to consider is how well the soil has been prepared before planting. If you are confident that the pH is both correct and stable, all nutrient deficiencies have been corrected, the soil organic matter concentration is in the range you want, and annual and perennial weeds are under control, then you have great flexibility in your choices. On the other hand, if the pH is still too high or low, weed barrier fabrics and deep organic mulches are not good choices. This caution is especially true when pH is too low and you need to incorporate a liming material into the planting zone. Weed barrier fabrics and organic mulches, such as bark or sawdust, make incorporating lime and immobile fertilizers and soil amendments very difficult or impossible. Organic mulches are also largely ineffective against established perennial weeds.

Leaving the soil bare, however, greatly increases weed problems within the planting rows. With few organic herbicides available and none particularly effective against perennial weeds, organic fruit growers must rely on mechanical cultivation, hand weeding, thermal weeders, and spot spraying organic contact herbicides.

A compromise that provides good weed control while allowing you to continue applying soil amendments is to place a piece of weed barrier fabric around individual trees or bushes (see figure 7.5). Depending on your in-row spacing, cut out weed fabric squares that are 24 to 36 inches per side. Make a slit from one side to the center of each square and make a hole in the center just large enough for the trunk or collar to fit through. The fabric squares can be staked into place with wooden pegs or aluminum or steel wire staples. Alternatively, you can bury the fabric edges with soil to hold the squares in place. These fabric squares keep a bare zone of soil around the orchard crop plants while allowing cultivation and other cultural activities. Using small squares also greatly reduces the cost of weed fabric and reduces disposal problems later.

Use small squares (2×2 feet to 3×3 feet) of weed barrier fabric to maintain a vegetation-free zone around individual trees.

Perennial alley crops. Bare alleyways create problems in the form of soil erosion, soil compaction, dust, loss of organic matter, and poor access during wet weather. For mature orchards where irrigation water and/or rain are adequate for both the orchard crops and alley crop, permanent alley crops can do a good job of preventing erosion, soil compaction, and loss of soil organic matter. The negative side is that alley crops compete with your orchard crops for soil moisture and nutrients and can reduce fruit yields. There are several approaches to permanent alley crops, two approaches being especially popular at the moment: 1) The alley crops can be made up of a sod-forming grass or blend of grasses, often supplemented with clovers; or 2) the alley crop can be made up of legumes, usually alfalfa or alfalfa blended with clovers, such as white Dutch clover. In areas where soil frost heaving is not severe, bunch-forming grasses that go dormant during the hot, dry summer months can reduce competition with the orchard crops while still reducing soil compaction and erosion and allowing access during wet conditions. Typical permanent cover crops include various fescues, wheatgrasses, alfalfa, and clovers.

Annual alley crops. For a young fruit planting where soil amendments may be required, consider using annual cover crops, such as barley, oats, ryegrass, or wheat, supplemented with peas. Annual alley crops provide many of the benefits of permanent covers, but they can be quickly and easily removed, if necessary.

Whatever strategies you choose, keep in mind that young fruit trees and bushes compete poorly with other vegetation. At a minimum, keep a 3- to 4-foot diameter, vegetation-free circle around each newly planted tree or bush.