How to Take Care of Your Brain Body in Middle Age and Older to Keep It Young and Prevent Memory Loss

When most people walk into a room and can’t remember the reason, they automatically think they’re just getting older. They laugh it off and ask their friends if they’re similarly at the are-we-losing-it stage, but internally, they freak out.

What if I told you that what you put on your fork could increase your brain volume and offset memory loss?

Symptoms like memory loss and diminished capacity for learning are the brain symptoms of a brain body out of balance. Instead of rushing to complete Sudoku or serial crossword puzzles, look at the root cause—which, as you know by now, is inflammation, usually originating in the gut, causing neurodegeneration (nerve cell breakdown) and ultimately leading to memory loss.1 Sometimes the reason for the inflammation is simply eating too many of the wrong foods and not enough of the good foods. Add in chronic stress, insufficient exercise, and maybe antibiotics, and, over time, your gut becomes leaky, the bugs get out of balance, you become inflamed, the inflammation passes into your brain, and your synapses weaken. All you notice is that your memory declines.

Memory is no small issue after age forty. My patient Jane’s experience with memory loss was no laughing matter: at age sixty, her short-term memory started to fade. She came to my office with her husband as her advocate, a look of serious concern on both of their faces. Jane explained that her symptoms began just a year or two before with some forgetfulness, like not recalling a word in conversation or sometimes repeating herself, as in asking her husband a question she had already asked. Together they had seen an Alzheimer’s specialist who didn’t think she had the disease (and she didn’t have the so-called Alzheimer’s gene, APOE4) but didn’t know for sure and recommended that she consider hormone therapy to help her memory and cognitive function.

What I found was that for Jane, estrogen was no longer serving in its role as her master regulator of the female brain and body, as we discussed back in the introduction. Her brain was no longer adaptive and able to grow and respond to chemical and physical insults, and memory loss was just one of the symptoms of her brain/body breakdown. Her blood sugar was in the prediabetes range, setting her up for type 3 diabetes—a term that captures the overlap between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease, including a constellation of inflammation, oxidative stress, insulin resistance, increased glycation (a form of sugar-induced aging that occurs when chronically high blood glucose levels injure various proteins, making you look and feel old), and cognitive deficits.2 Several blood tests of inflammation were elevated, putting her at yet greater risk for cognitive decline.3 Her brain MRI showed mild to moderate cerebral atrophy (brain shrinkage), and that scared the daylights out of her.

“What can we do?” she asked plaintively. I felt for her, and I gave her my best recommendations, covered in this chapter. We needed to get estrogen back into its rightful role as the regulator of her brain/body health. You can do that too, if you’re perimenopausal or postmenopausal and estrogen bioidentical hormone therapy is a smart option for you. I’ll show you how to determine if it’s the right choice.

Memory stitches together your inner life. The term memory refers to the complex interplay of multiple brain functions: nerves and chemical processes that govern the learning of new information, storage, and, finally, recall. Most important, memory is the main indicator of the balance in your brain between growth and repair (neurogenesis) versus wear and tear (neurodegeneration). Some of your memories are stored in the brain permanently and can be recalled as needed. Other memories are stored in the temporary memory bank, then discarded.

My memory has never been perfect, but I was better able to remember appointments in my twenties than I am now. My husband and I are similar in this regard. It turns out that after forty, it’s the recall of recent life events, people, faces, names, and dates that starts to fade first. When memory begins to disappear, thoughts do not get properly encoded and stored, leading to a loss of cognitive function and quality of life. Hormone loss can amplify poor memory. The question is, does memory start to go because age is taking its natural course, or because of something we thought was harmless, such as drinking too much wine or not filtering fluoride from our tap water? Read on to find out.

Memory is an important indicator of your cognitive reserve, or your brain’s resistance to damage, injury, decline, and neurodegeneration. A few memory glitches are normal as you age—after all, your brain works perpetually and is constantly interrupted. So how do you tell the difference between a little forgetfulness and early signs of dementia? Even if you have only normal age-related memory issues, there is good news about the malleability and plasticity of memory as you age.

Do You Have Memory Issues?

Do you have now or have you had in the past six months any of the following symptoms or conditions?

- Have you found that a word is “on the tip of your tongue,” but you can’t quite access it?

- Have you forgotten someone told you something and needed to be reminded, especially something you just heard? Or did you mix up the details of what somebody has told you?

- Have you forgotten what you just said, or repeated what you just told or asked someone?

- Have you developed facial blindness (i.e., difficulty recognizing faces)?

- Have you forgotten important details of what you did yesterday?

- Have you experienced less mental clarity or brain fog, particularly later in the day?

- Have you had difficulty remembering what you just read and have to start the page or article over again? Or have you observed that you have difficulty following the thread of complicated stories, conversations, or plots, such as in movies, or started to read something without realizing you had read it before?

- Have you experienced less interest in reading or other cognitive tasks that you previously enjoyed?

- Have you perceived a decrease or simplification in vocabulary?

- Have you forgotten to do things you said you would do or planned to do, or had to check whether you had done something? Can you not recall when something happened?

- Have you detected a decreased ability to communicate in a foreign language that you previously were able to speak and read readily?

- Have you experienced increased anxiety when driving or trying to find your way to familiar places?

- Have you forgotten to tell somebody something important?

- Have you forgotten where things are normally kept?

INTERPRETATION

If you said yes to three or more questions, you may have an issue with memory. Five or more, and it’s highly probable that you have a problem with storing and retrieving information, tracking conversations and tasks, and performing routine activities. No need to freak out just yet—we need to cast a wide net when it comes to memory so that we can catch any loss as early as possible, when inflammation and breakdown might be occurring but before brain/body failure. Help is on the way! The protocol at the end of this chapter will strengthen your recall, reverse memory issues, and help prevent further decline.

How Memory Works

In medical school, I encountered several people with photographic memories. They didn’t need to study for hours in the library like I did, trying to cram an impossible volume of facts into their brain. They saw a biochemical structure of a cholesterol or a diagram of a complicated mechanism in the immune system once and retained it. Similarly, both of my daughters remember lyrics to entire songs after hearing them only a few times, while I can barely jump in with a line from the chorus. But human memory is not designed to be perfect, regardless of age. Perhaps I should repeat that—for memory’s sake: memory is not designed to be flawless.

Memory is complex, involving encoding and storage into short-term memory, and then sometimes long-term memory, and then retrieval of that information. Memory is what allows you to remember past experiences and recall frames of mind, education, impressions, circumstances, habits, and skills. Similar to how I delete emails on my laptop to make space in my inbox, you delete or prune old memories if they no longer seem relevant, like the phone number for your local nail salon that you need just once.

When it comes to memory, the creation of neurons matters less than maintaining the connections between them. We used to think that synapses were simply a transfer point between neurons; now we know that synaptic plasticity is the key capacity of connections between neurons to strengthen or weaken over time in response to higher or lower activity. Synaptic plasticity contributes greatly to learning and memory and may be the answer for older brains to adjust for lesser function as they age.

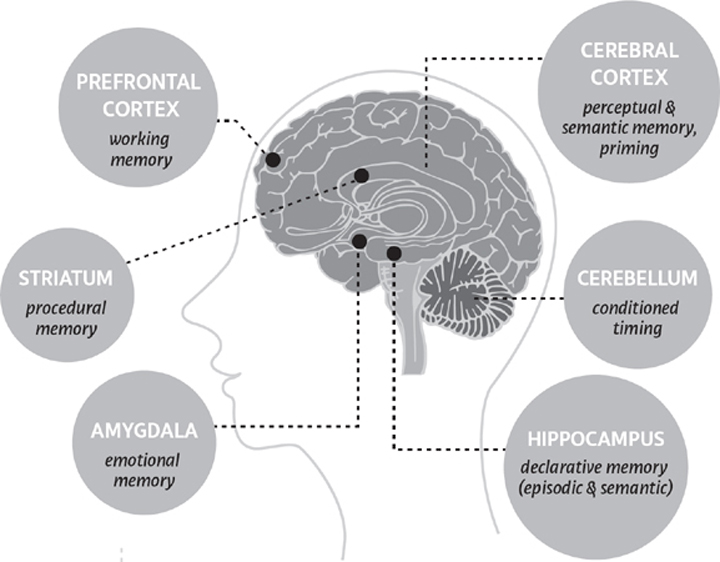

As the name implies, short-term memory is fleeting, whereas long-term memory is more hardy and enduring. Memories aren’t stored like an image in one place but in fragments distributed across various parts of the brain (see Memory in the Brain). Upon recall, your brain reassembles the various pieces for an intact memory. Perhaps because of the fragmentation, our memory is subject to error, even under normal circumstances.

The Science of Memory

Functional brain-imaging techniques have allowed scientists to map how and where memories are made.

- Hippocampus: The hippocampus is the key part of the memory process. Recall from chapter 1 that acquiring and consolidating memories begins in this horseshoe-shaped structure found in both hemispheres in the brain. The hippocampus is the way station before memories are placed into long-term storage. An indexer catalogs memories so they can be reconstructed at a later time.

- Amygdala: The amygdala stores emotionally charged memories.

- Prefrontal cortex (PFC): The CEO of the brain is responsible for the short-term memory of any information that needs to be immediately processed (aka working memory), such as a pitcher who has to remember how many outs there are and where the runners are on base. These temporary and conscious memories are based on linguistics and perception and guide your reasoning, decisions, and behavior.

- Cerebral cortex: This large outer layer of the brain stores and maps long-term memories.

- Striatum, or corpus striatum: Any voluntary activity you do is triggered by the striatum. It receives information about a desired goal from the cerebral cortex and prompts your body to move, in a smooth and fluid manner, based on previous experience. The nucleus accumbens, your reward center, is part of the striatum.

- Cerebellum: As partner to the striatum to effortlessly perform procedures, the cerebellum is key for attention, language, emotional response, and timing based on prior experience, such as how to tie your shoes. The cerebellum helps you hone skills for daily tasks without having to consciously recall each step.

ENCODING

Encoding is the first step of memory-making. Sight, sounds, smells, touch, and words create our perception of something. That perception becomes a construct stored within the brain in either short- or long-term memory and may be recalled later. Sufficient sleep is crucial for memory encoding as well as later offline consolidation of memory. Our hormones—particularly estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone—may influence our ability to encode.4 Not long ago, scientists thought that steroid hormones like these were produced only in the body, not the brain, which meant it would take a long time—hours to days—for them to affect a brain cell. Now we know that the brain itself produces these steroid hormones, called neurosteroids, that can impact brain cells in a very rapid timescale of seconds to minutes.5 Low levels of sex hormones in women are linked to negative bias with memory encoding, meaning the women were more likely to remember negatively charged events.6

Memory in the Brain

SHORT-TERM MEMORY

Your short-term memories consist of information that you need to recall only transiently for a few seconds or minutes, like the date and time of the dental appointment you just made or the price of your dinner entrée at a restaurant. One form of short-term memory is working memory, such as when you’re shopping online and comparing the prices of different brands.

You have space for about seven bits of information at a time, which is why doctors try to get you to remember a seven-digit phone number as part of a test called the “mental status exam.” New memories overwrite the old ones. Distraction also brings in new information that can overwrite what you just learned, requiring you to go back and look up information again, or retrace your steps as you try to remember what you were about to say.

LONG-TERM MEMORY

You know the old saying that people don’t remember what you say, but they remember how you made them feel? Your brain discerns if a memory is important enough to store long-term, usually because of an emotional charge or personal meaningfulness (thank you, amygdala). Long-term memories are stored throughout the cortex as groups of neurons that fire together. As a whole, long-term memories are a gigantic reserve with rather unlimited space in the cerebral cortex, at least in the healthy brain.

There are two types of long-term memory: explicit and implicit. Explicit memories require a conscious effort to recall, including factual knowledge, like what you learned in school, the details of Titanic, or even that bachelorette party you may want to forget. Implicit memories are procedural, like how to floss.

What’s Normal as You Age Vis-à-vis Memory?

As we age, we fall prey to momentary lapses in memory, and not all of them are due to aging or something more serious, like toxicity or dementia. Now, this is the part I know you’re probably most concerned about. We all are! Remember, memory is imperfect for all of us at one time or another. Just think about children or teens in your life—how often do you have to instruct them before they really remember on their own? By age forty or fifty, we’ve all had issues with memory because of correctable problems like a stretch of poor sleep, acute stress, or an overwhelming workload.

However, as you age, mental capacity can get smaller, meaning there’s more pruning. After turning fifty, I’d occasionally be mid-interview, about to make the last two points in response to a question, and my mind would go blank. I’d make the first point, then search for a beat or two for the missing point. This problem is thought to be a result of the frontal lobes briefly losing track of the next step in the brain process. Fortunately, brain exercise helps your frontal lobes stay sharp; consistent meditation and physical fitness improve this type of memory loss.

Not all forms of memory are equally affected by age. Procedural memory, such as how to ride a bike, remains intact. In general, the frontal lobes and hippocampus are more vulnerable than other parts of the body and thereby more susceptible to momentary memory lapses. Other types of declarative memory decline, such as semantic and episodic. Semantic memory is the recall of general facts, like state capitals, world population numbers, and carbon dioxide emissions. (These are the hot topics in our household right now.) Episodic memory is a recall of autobiographical events or episodes at a particular time and place—like a birthday celebration when you were forty. Moreover, spatial memory—such as the geography of your neighboring towns or how to find the bathroom in your friend’s home—tends to decline with time. Lisa Genova’s novel Still Alice, also made into a movie, tells the story of a professor who developed early Alzheimer’s and chronicles painfully how she got lost in familiar territory.

Here’s a summary of how aging affects memory:

- Slower processing speed, so you learn more slowly

- More effort to learn new information in the first place

- Reduced ability to perform tasks involving attention—less detail is taken in, such as where you put your wallet or keys

- Slower recall of memories

These behavioral changes reflect biochemical and structural changes, including a smaller hippocampus, loss of function and structure in the frontal lobes, loss of brain cells, and lower quantity and function of receptors.

Nevertheless, we have reasons to face growing older and its inevitable memory changes with optimism. It may take slightly longer to learn new information, but retention is the same as that of a younger person. Processing speed may be a little slower, but you can adjust and work around it: crack a joke as you wait for the right word to arrive or pick a second-choice word. As you learn, simply pay attention more closely. In my podcast, I used to have a time-out for the “sexy librarian moment” when I would recap what we just learned. I did it because it helps everyone’s learning, including my own—revisit, review, and recap more after age forty to strengthen and reinforce the memory pathways.

The best news is that memory is malleable, meaning that much of your memory is under your control as you age. Your task is to understand the nefarious factors that increase neurodegeneration and replace them with the virtuous factors that enhance neurogenesis.

What Affects Memory

The most important levers that impact your memory are diet, physical activity, stress, sleep, gut function, social and mental engagement, toxins, and genes. Jane had problems with all of these: on the Perceived Stress scale, her level of perceived stress was high at 32. (Take the simple ten-question test and score yourself—the link as well as how to score it is in the Notes.7) She started wearing a fitness tracker and barely got seven thousand steps per day. Her gut tests showed leaky gut and dysbiosis. Heavy metals were high in her blood, and a gene test showed that she had a variant of the FKBP5 gene, making her potentially more vulnerable to stress.

DIET

I’ve mentioned previously that the brain is only 2 to 3 percent of body weight but consumes up to 25 percent of energy in the body; this mismatch means that the brain is especially hungry for the nutrients you eat compared with other body organs.8 The enormous drive for energy means that brain cells are more vulnerable than the rest of the body to mitochondrial problems and oxidative stress, and once damage occurs, neurodegeneration and memory problems follow.9 Food affects memory in many ways—it can lessen or worsen the stress response, increase or decrease nerve growth factors and neurogenesis, provide antioxidant defense or not, and trigger inflammation in the body that leaks into the brain.10 Sugar is perhaps the best known offender when it comes to your ability to think, learn, and remember—and develop stroke and dementia, including Alzheimer’s.11 Eating more sugar doubles your risk of cognitive impairment.12 For women in their forties, you need to know that perimenopause is when the brain’s ability to regulate sugar in the brain begins to falter because of dropping estrogen levels.13 Importantly, cognitive loss occurs even without a change in weight from excess sugar consumption.14 So if you think your consumption of sugar is acceptable because your weight isn’t going up, think again. Limited data from a small study in younger women ages twenty-five to forty-five suggest saturated fat may worsen memory, while fats found in oily fish (salmon, mackerel, herring, anchovies, sardines) improve it.15 Trans fats: shocker, bad for word recall—avoid them.16 Similarly, in a larger prospective study in older women, saturated fat again predicted worse cognition and verbal memory, whereas monounsaturated fat (think avocados, macadamia nuts, extra dark chocolate) was protective.17 Not surprising, the worst combination for your memory is the high sugar/high saturated fat diet (i.e., the binge-on-a-pint-of-ice-cream diet).18 That combo makes you fat, inflamed, and heading to a nursing home. Forgetaboutit.

GUT

As the foundation of the brain body, the gut/brain connection is critically important to your sound mind. Your gut contains 100 trillion bugs that influence your well-being in various ways, including your risk of anxiety and depression as described in the last two chapters. Microbes have their own memory.19 The DNA belonging to these bugs, your microbiome, is involved in most if not all biological processes, including the messages of the brain, cognitive function and flexibility, and the ability to remember.20 Taken further, when the microbiome of a healthy person is compared with that of a person with memory impairment, there are changes in the bacteria, including Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia. These phyla of bacteria correlated with cognitive test performance.21 In mice, fecal transplants improved memory and learning.22 Why? When your gut wall is leaky, your blood-brain barrier becomes leaky. On a molecular level, the tight junctions between cells loosen, and the process of intestinal permeability is regulated by proteins (like zonulin and occludin) produced in the gut. Inflammation spreads from the body to the brain, and memory can suffer.

Overall, you’re fighting an uphill battle as you age because the composition of the gut microbiota changes in the direction of less diversity and fewer good bacteria.23 You harbor more gram-negative bacteria, which secrete the dreaded lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and create inflammation in the gut that can travel to the brain.24 Changes in gut microbiota can alter blood-brain barrier permeability.25 In sum, the gut microbiota’s effect on inflammation and brain function in the hippocampus can rob you of memory and a sense of calm.26

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

Regular exercise enhances memory and reduces dementia by 38 percent.27 It increases the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is like fertilizer for the soil of your brain.28 It boosts neuroplasticity.29 Whether you’re a kid or an adult, being physically fit is linked to a bigger hippocampus and better memory.30 What type of exercise? How much? Aerobic exercise seems to be the best at preserving brain volume and memory as you age, perhaps because it boosts BDNF, whereas strength training may not be as effective, particularly in women.31 All types of exercise—aerobic, resistance, and multimodal—benefit executive functioning in women more than men.32 Ideally, exercise four or more times per week, which is associated with halving the risk of dementia.33 While it’s never too early to exercise, middle age may reap the greatest benefits. That means you. Now. Today! And it’s never too late—even physical activity in patients sixty-five and older with cognitive impairment and/or dementia can improve cognitive function.34 Conversely, when you don’t move much (like Jane, as documented with her fitness tracker), memory worsens and cognitive function declines.35

Yoga also prepares the body and mind for meditation, which also helps memory. Even inexperienced people improve their memory with yoga—as few as six sessions have been shown to enhance working memory.36 Many other studies confirm that yoga boosts memory and cognitive performance.37 Yoga increases melatonin production, which may improve sleep and indirectly promote better memory, as shown in multiple studies on different populations.38 Specifically, kundalini yoga has been shown to improve memory and executive function in twelve weeks, and it boosts depressed mood and resilience among patients fifty-five and older with mild cognitive impairment.39 In fact, the study showed that kundalini yoga is better than memory-enhancement exercises, which have been considered the gold standard for managing mild cognitive impairment. Yoga turns on the relaxation response and regulates the genes that help you calm down, produce more glutathione (the body’s most important antioxidant) so you can detoxify better, sleep more soundly, and wake up refreshed, ready to remember.40

STRESS

By now you’re probably feeling stressed from hearing about all the horrible things associated with stress. I’ll keep this short. You’ve learned that excess cortisol is a brain/body toxin—it pokes holes in the gut wall, leading to leaky gut, and disrupts the gut/brain axis. Additionally, the hippocampus, the brain’s memory center, is extremely vulnerable to stress.41 When you have a high degree of perceived stress and, as a result, a high level of cortisol, the excess cortisol deactivates and hurts the hippocampus.42 Over time, the hippocampus shrinks in volume in response to prolonged cortisol in the blood.43 Metabolism of the brain in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex decreases significantly, and connections between brain cells weaken.44 Memory becomes impaired, especially retrieval.45

On the other hand, there are hormones that can protect your brain from the neurotoxic effects of cumulative cortisol. In women, estrogen plays an important role in buffering the effect of aging and stress, keeping the volume of the hippocampus larger before menopause compared with men, and growing the hippocampus after menopause in women receiving estrogen therapy.46 In addition to estrogen, DHEA can protect the hippocampus, but not in everyone. In my opinion, preserve your memory: keep your cortisol, estrogen, and DHEA in the mid-range up to menopause, and possibly for up to ten years postmenopause. Scientific proof is lacking, so this is my opinion based on the literature and clinical experience.

Jane’s cortisol was high on a dried urine test, and both estrogen and DHEA were low, so cortisol was running the show—raising blood sugar and blood pressure, increasing visceral fat at the waist, poking holes in her gut lining, fanning the fire of inflammation, decreasing lean body mass, lowering brain-derived growth factor production—making blood sticky and slowing down cognitive speed and memory. What helps your memory is to develop stress plasticity or resilience—the ability to cope with and adapt to a wide range of stressors over time.

SLEEP

Sleep is when your brain sorts and stores the day’s information. Would you believe that the primary purpose of sleep is to form memories? So bedtime may be the most important time of the day for your brain’s health and neuroplasticity. During sleep the brain restores neuron networks so they are ready for action once more when you awaken. The space between brain cells enlarges, making room for the flow of ions and debris, like amyloid.47 It’s called the glymphatic pathway, and it works best when you’re sleeping on your right side. Additionally, sleep is the time of healing and repair, when growth hormone and melatonin are at their highest. Autophagy occurs, which is an important editing process that allows your body to remove damaged mitochondria and proteins. Overall, the clearance of metabolic by-products and toxins increases four-fold while sleeping.48 Both REM and non-REM sleep enhance and strengthen long-term signal transmissions between neurons after repeated stimulation—another key requirement for memory and learning. All said, sleep is like hitting a refresh button on the hippocampus.

But how many of us sacrifice sleep for other life demands? When you don’t get sufficient sleep, memories are misfiled or dropped. Sleep deprivation interrupts the movement of information from short-term into long-term memory banks by impairing function, encoding, and consolidation. Hence, memory performance suffers, like when my patients tell me they are experiencing “Mommy brain” and have trouble finding certain words.

Five hours of sleep deprivation in one night’s cycle changes the connections between brain cells, at least temporarily, in mice.49 Insomniacs show pathological thinning of the insulation called myelin around nerve cells; myelin’s job is to enhance the ability of nerves to send signals to each other. Most of the thinning nerve tracks are on the right side of the brain, the seat of emotion, thought, and sensory information (sight, touch, smell), so the person who suffers from sleep deprivation may have more difficulty with proper vision and could be more left-brain activated.50

Lack of sleep affects neurogenesis, particularly in the hippocampus.51 You can even develop false memories if you lose sleep.52 Structurally, sleep deprivation blocks your synaptic plasticity and efficiency by changing the density and shape of neurons (the “dendritic spines” of neurons, to be exact—these are like sprouts on the branches of neurons) of the hippocampus.53 One article called the problem the “tired hippocampus.”54 (Read more details in the Notes.55)

Fortunately, recovery sleep (sleeping more to make up for a sleep deficit) restores memory, meaning that symptoms of poor memory from lack of sleep may be reversible, up to a point. Unfortunately, aging is associated with worsening quality of sleep, including shorter duration and more time awake after you fall asleep. People tend to awaken more frequently starting in middle age and to experience a profound decrease in the deepest stage of slow-wave sleep as they get older.56 Homeostasis in the sleep regulation system and circadian rhythm declines with age. Overall, working memory and new episodic memories get worse. Even though poor sleep is associated with poor cognitive function, including memory, the good news is that older adults are more resilient around the cognitive hits of sleep deprivation and fragmentation compared with younger adults. Still, it’s worth improving sleep in order to enhance cognition, performance, and memory, regardless of age.

TOXINS

By now, you’re probably not surprised to see toxins on the list. Toxins can lead to loss of mental function, reduced brain size, and changes in the structure and function of brain cells, ultimately resulting in memory loss and the rest of the broken seven that we’ve covered.

Alcohol. Alcohol impairs memory, erodes mental function, reduces brain size, and causes brain cell dysfunction.57 Makes you want to put down that glass of wine, doesn’t it? Loss of brain volume is more likely to occur in women compared with men, according to the Framingham Study.58 The more alcohol consumed, the greater the shrinkage. Both alcoholics and people with Alzheimer’s disease demonstrate hippocampal atrophy.59 It’s like the hippocampus receives less blood flow and life energy and ultimately goes soft and decreases in size, like a neglected muscle. Alcohol (technically, ethyl alcohol or ethanol) and acetaldehyde (released as alcohol breaks down) kill brain cells.60

The frontal lobes are most affected by alcohol abuse.61 Alcohol can degrade the prefrontal cortex (the brain’s CEO), involving attention, inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility.62 Further, in a study from the University of California at San Diego of heavy and light drinkers, chronic consumption of alcohol interferes with balance and visual and spatial ability. Heavy drinkers compromise their short-term memory and working memory.63 Granted, that’s why many people drink—they want to forget what just happened at work or home, and alcohol makes forgetting possible. Alcohol also disrupts normal function of estrogen and cortisol, which can impact encoding of memory.

Chronic, dependent drinkers are at greater risk of alcoholic dementia and Korsakoff syndrome, a type of dementia that includes severe amnesia as a result of vitamin B1 deficiency and alcohol toxicity. In a study of twenty-two female adolescents, nineteen of whom were abusing alcohol, results showed that the patients had less gray matter in the frontal lobes, resulting in poor control over behavior and decision-making, impairment in internal awareness, problems with error detection, and antisocial and drug-using behavior.64

Need more evidence relevant to you? When I was in medical school twenty-five years ago, a limit of one glass of wine per day was considered safe for women, two glasses for men. Then most of us thought moderate drinking was no problem—that is, about eight to twelve glasses of wine per week (one glass of wine is five ounces, which is typically about 12 percent alcohol, and contains 14 grams of alcohol). So over the years I began drinking more. Maybe it was an attempt to cope with small children, or just enjoying life near the wine country, but my occasional glass of wine on the weekend became one glass every night, and then two. As a recent New York Times article on the topic by a fellow mother from Berkeley describes: “We tell people to go ahead and have just a little bit of an addictive substance. Let’s acknowledge that that’s complicated.”69

WOMEN AND ALCOHOL

Women are more vulnerable to alcohol’s adverse effects compared with men because we have more fat and less water. We also make less of the detoxifying enzyme called alcohol dehydrogenase, so that acetaldehyde, a possible carcinogen made from the breakdown of alcohol, can accumulate in our bodies. Since we metabolize alcohol differently, women have higher blood alcohol concentrations for the same serving, and the higher levels persist longer. So women are more likely to experience neurotoxicity, liver damage, heart disease, and cancer at lower drinking levels than men.65 Alcohol is more likely to disturb a woman’s sleep, but many women fail to notice.66 Yet women are drinking now more than ever.67 It’s a growing problem. The Washington Post says that white middle-aged women are drinking themselves to death.68 Indeed, more than 70 percent of white women drink, compared to 37 percent of Asian, 41 percent of Latina, and 49 percent of black women. Since 1992, the number of middle-aged women seeking rehab has tripled.

Over time, the data that seemed to promote moderate drinking have become less clear and robust. Imaging studies have failed to show that drinking offers any benefit to the brain.70 Historically, the data varied or showed an adverse effect only with heavy consumption,71 but moderate alcohol consumption can shrink the brain and its gray matter, too.72 Evidence now suggests more conclusively that moderate drinking can have a deleterious effect on the brain, as shown by a recent study from Oxford that followed 550 people for thirty years with weekly alcohol counts, cognitive testing, and MRIs.73 More alcohol was associated with atrophy of the hippocampus, even among moderate drinkers.

The upshot? Lay off the sauce to preserve your brain and memory.

Mercury. Mercury’s effects on the brain have not been studied as extensively as other toxins. But a study from the University of South Denmark, Harvard School of Public Health, and the University of Copenhagen examined 923 children for mercury levels and neurobehavioral traits. The study found that mercury impairs visual, spatial, and working memory.74 Mercury exposure can come from contaminated seafood, such as tuna and swordfish, and dental amalgams.

Mold. Mold exposure impairs memory, slows reaction time, disorders balance and cerebellar function, and decreases verbal recall, problem solving, and perceptual motor function. Whew! The most common contributors are from molds hiding under or behind appliances like your dishwasher, under drippy sinks, under leaky windows, inside wall cavities where plumbing leaks, on skylights, on air-conditioning coils, and in new buildings that were built in the rain or have water damage. Many molds in homes can impact the nervous system in the areas that control memory, attention, and other functions.75 A study at the University of Southern California studied a group of about one hundred people exposed to mold toxins compared to a group of one hundred people exposed to toxic chemicals (e.g., diesel exhaust, formaldehyde, organophosphate insecticides, cleaning chemicals, carbon monoxide, chlorine). The impairments—such as forgetting the word stroller or epiphany—in the chemically exposed group were about the same as in the mold-exposed group.76

PCBs. PCBs were used widely in electrical appliances and other equipment. Exposure to PCBs is associated with poor visual recognition memory.77 This form of memory begins in early infancy and is remarkably resistant to decay, unless you’re exposed to PCBs. That means if PCBs have affected your memory, you could be staring at a friend at a party for ten minutes before her name comes to you. PCBs are no longer manufactured in the United States but can persist in the environment for decades. PCBs are still present in many products made before 1979, when their use was outlawed.

Aluminum. Excess intake of aluminum causes cognitive impairment, short-term memory dysfunction, and decreased learning.78 Aluminum occurs in soil, air, and water. You may be exposed to aluminum in processed foods containing flour, baking powder, coloring, and anti-caking agents. (But thankfully, you’re not eating processed food by now.) The average US adult eats 7 to 9 mg of aluminum per day in their food, according to the Centers for Disease Control.79 Beverage cans, personal care products like antiperspirants and cosmetics, and medicines are other common sources, including antacids (300 to 600 mg aluminum hydroxide per tablet or capsule), buffered aspirin, and vaccines.

Lead. Even though lead is no longer in household paints, it still lurks in some houses built before 1978, when the federal government banned consumer use of lead-based paint. It can occur in soil, and especially in drinking water, as we witnessed in Flint, Michigan. After the crisis in Flint, five people including the head of the state’s health department were charged with involuntary manslaughter for ignoring a serious problem with lead pipes contaminating the water.80 Lead can seriously harm your brain. Even at low to moderate levels previously considered safe for adults, lead exposure can impair short-term memory.81 For children, there is no safe lower threshold for lead levels without hurting cognitive function, and pregnant women should avoid all exposure to lead.82 Lead affects attention, processing speed, visuospatial ability, working memory, motor function, and general intellectual performance, resulting in lower IQ.83 In animal models, lead creates inflammation and neurodegeneration.84 So it’s no wonder that lead exposure leads to elevated markers of Alzheimer’s disease.85

I know, it seems like toxins are hiding everywhere. Unfortunately, they are. But I promise that we can mitigate their effects and protect our brains. Review the protocol in chapter 2 for specifics.

GENES

We are still identifying and trying to understand the genes most involved in memory. Here are a few of the important ones. (See Appendix B for help on whether to test and, if so, which labs to use.)

- APOE4 (Apolipoprotein E4), the “Alzheimer’s gene,” can affect memory by early midlife (i.e., in your forties).86

- FKBP5 (FK506 binding protein 5) is a gene involved in stress (glutocorticoid receptor sensitivity) and memory formation, including intrusive memories.87

- KIBRA (kidney and brain expressed protein) has certain variants that enhance memory.88

- SCN1A (encoding the α subunit of the type I voltage-gated sodium channel) provides instruction for sodium channels.89

- NR2B codes for part (subunit) of the glutamate (NMDA) receptor and is involved in working memory.90

Three Levels of Impaired Memory

Most of us think of brain damage as what happens when you hit your head on the football field and suffer a concussion or survive a car accident. But brain damage can result from seemingly innocuous things like eating too much sugar, or undergoing stress, or a tick bite. The brain tries to create balance in the face of competing demands, stressors, out-of-whack hormones, endocrine disruptors, and trauma. Memory impairment usually means there’s been damage to brain structures involving storage, retention, and recollection of memories. Impairment can result from mild conditions such as dehydration and nutritional deficiencies to more serious problems like high blood pressure, PTSD, diabetes, small strokes, and dementia.

The three main categories of memory impairment are:

- Age-related memory issues. (See here.)

- Mild cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI is an intermediate category between normal age-related memory loss and dementia. There are two subcategories: amnestic (impaired memory) and nonamnestic (decline of mental functioning such as language, attention, or processing).

- Dementia. Dementia is characterized by a marked impairment of memory and cognitive function that interferes with daily living, sometimes accompanied by personality and behavioral changes like agitation and rage. Short-term memory fades first in dementia. Sixty to 80 percent of cases are Alzheimer’s disease. The hippocampus, which turns perception into memory, is hit hard by Alzheimer’s disease. Vascular dementia is the next most common and results from damage to the blood vessels that provide oxygen to the brain. Vessels can become narrowed or blocked and lead to silent or overt strokes as a result of high blood pressure or pathological cholesterol deposits. When blood flow is compromised, brain cells die.

THE QUESTION OF ESTROGEN THERAPY

The main estrogen you make during the reproductive years, estradiol, is neuroprotective, promotes synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus, and protects against cognitive decline associated with aging and neurodegenerative diseases.

When you have a sensory experience that provokes a memory, estrogen immediately sends signals in the service of improving your learning.91 Estradiol (E2) is the main estrogen of interest when it comes to memory, and it is made in the ovaries, adrenal glands, and brain. After menopause, estrone (E1) is the dominant estrogen, and it’s made primarily in the adrenals and fat tissues, plus a small amount in the ovaries.

Estradiol, both endogenous (the type made by you inside your body) and exogenous (i.e., estradiol therapy), benefits memory up to a certain point. There’s a threshold that you reach with estrogen and memory, probably in the first ten years of menopause, when estrogen therapy stops being helpful. Based on the science, estrogen therapy may benefit healthy nerve cells, but weaker neurons may be compromised by long-term treatment. That is, once the memory loss and dementia process begins, treatment with estrogen is no longer effective and may even increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.92 So there is a window of opportunity to take estrogen for cognitive health and memory.93

While estrogen treatment in perimenopause and early menopause may postpone memory loss, it works in a bell-shaped dose-response. That means your best memory occurs when estrogen is midlevel—not too high and not too low.94 Put another way, low levels of estradiol and high levels of estradiol are associated with poor memory, cognitive impairment, and declining brain function. However, the conventional approach at this time is not to treat women in menopause for the primary (before symptoms) or secondary (when symptoms start) prevention of dementia.95

So the debate rages on with many advocates for and against the use of estrogen for brain/body health as a woman ages, and specifically about the exact “midlevel” of estrogen that is optimal for the brain body.96 The antiaging estradiol enthusiasts believe it is 80 pg/mL, while the more conservative epidemiologists concerned about prevention of osteoporosis believe it is somewhere between 5 and 20 pg/mL (as opposed to normal postmenopausal levels that are often less than 5 pg/mL).97 After age forty-three or thereabouts, the ability of estradiol to improve cognition declines due to decreased estradiol levels and decreased expression of estrogen receptors.98 Women who have their ovaries surgically removed and experience low levels of estradiol as a result show diminished cognitive function that is reversed by estrogen therapy, if it’s begun immediately following surgery.99 Menopausal women (mean age fifty-three) seem to experience mood benefits from estrogen therapy but not necessarily cognitive benefits.100 Other studies of the benefits of exogenous estrogens for memory and executive function probably weren’t large enough to achieve the power to prove they work or not.101 So the appropriate next question is: if you want to start estrogen (estradiol) replacement to prevent or reverse memory decline, when is the best time to start?

Common sense says to start at the time of estradiol decline, which begins for most women in their forties, but it’s a complex decision. The trick is to define your own window of opportunity to take estrogen for the maximum cognitive benefits, including memory, and it seems to be from about age forty-three to sixty-one.102 From the Women’s Health Initiative, the optimal period of estrogen therapy when considering heart disease and breast cancer is ages fifty to fifty-nine, but what about memory? It seems that earlier initiation may be better to protect against cognitive aging that occurs fifteen to twenty years later. Further, we may want to preserve estrogen levels instead of allowing them to drop in late perimenopause and early menopause and then try to play catch-up—the benefits of estradiol on the brain seem to decline if you take it after ovarian hormone deprivation, i.e., low estradiol levels.103

There are other factors to consider. On the positive side, estrogen preserves memory, brain function, vaginal lubrication, and bone strength and prevents hip fractures and colon cancer. Estradiol helps to preserve the blood-brain barrier, prevents neuroinflammation, refortifies weak mitochondria, and promotes neurogenesis in the hippocampus.104 Therefore, you won’t be surprised to learn that estradiol may help reverse the memory symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease and might be helpful—we don’t yet know definitively—in women at risk for dementia.105 On the other hand, oral estradiol increases the risk of stroke and may increase the risk of cardiovascular problems in susceptible women. Transdermal estrogen is far safer than oral and is the only type of estrogen that I prescribe.106 If you have a uterus, you will need to take progesterone or progestin (synthetic progesterone) to protect the uterine lining from cancer.

What I’ve done in my practice is to make a risk, benefit, and alternatives balance sheet for each patient based on her risk factors, genomics, and quality of life. It’s not as simple as a yes/no answer of whether you should take estrogen. Rather, it’s a question of whether it makes sense given your circumstances and whether it should be an in-between dose (like half a dose or three-quarters of the standard estradiol dose) and maybe even for a short period of three months (which can confer longer benefits107 and can serve as an n=1 experiment for how estradiol works specifically for you). Fortunately, estradiol is available by prescription only, so there is a gatekeeper in place who can help you decide if taking estradiol is right for you.

Risks of Estrogen Therapy After Seven Years of Treatment |

||

Event |

Risk without estrogen therapy |

Risk with estrogen therapy |

Venous thromboembolism (blood clot) |

16/1,000 |

16–28/1,000 |

Stroke |

24/1,000 |

25–40/1,000 |

Gallbladder disease |

27/1,000 |

38–60/1,000 |

Breast cancer |

25/1,000 |

15–25/1,000 |

Clinical fracture |

141/1,000 |

92–113/1,000 |

Coronary events |

No increased risk |

No increased risk |

The Brain Body Protocol: Restoring Memory

Our brains are remarkable because of their ability to bounce back—i.e., neuroplasticity! You can prevent decline or stop further decline up to a point, and it’s important to start now during middle age. Many simple things can improve blood flow to the brain, heal body inflammation (which may reverse brain inflammation and damage), and rebuild the memory center. Overall, there’s not one tip that solves the whole problem. Rather, we need to try several proven things at once.

So how do you put all this information into a doable plan that protects your brain? Most of this protocol includes simple changes that easily fit into any lifestyle, resulting in better neurogenesis, increased synaptic plasticity, and halting of neurodegeneration. Since memory is your main issue, perform this protocol for forty days and then incorporate your new habits for the rest of your life.

BASIC PROTOCOL

Step 1. Eat for memory.

The big idea is to eat more of the foods that strengthen the memory and avoid the foods that don’t. That means we’ll restore the brain/body axis with the way you eat.

- Eat three meals per day, no snacks in between, ideally following an eight-hour eating window and sixteen-hour overnight fast to promote mild ketosis, which can help prevent Alzheimer’s disease, reduce inflammation, reset insulin, and improve cognitive function.108 Ketones like beta-hydroxybutyrate are a more efficient fuel source and increase production of BDNF.109

- Aim for one to two pounds per day of nonstarchy vegetables. Set the goal to enjoy twenty to thirty different species, all colors of the rainbow, each week. There’s no evidence that fruits or juices are effective in memory repair, so focus on the vegetables!110

- Eat protein at each meal, ideally fish,111 nuts, seeds, eggs, or anti-inflammatory animal protein.

- Add in more plant-based fat. The usual suspects: avocados, macadamia nuts, and coconut meat, milk, and cream. Cook with coconut oil, olive oil, or pastured ghee.112

- Consume prebiotic foods such as asparagus, fennel, garlic, leeks, and onions.

- Add in probiotic food like sauerkraut, miso, and tempeh.

- Drink bone broth.

Avoid:

- Sugar.

- Processed food.

- Alcohol, so you can keep estrogen and cortisol in balance and optimize sleep.

- Grains (wheat, rice, oats, corn) and pulses (beans, lentils).

- Dairy—I recommend an elimination diet for forty days, then add it back in to see if you react.

- Advanced glycation end products (AGEs)—AGEs can be made inside the body or consumed in the food you eat. Specific cooking methods can dramatically increase AGEs in your food. This means that in addition to keeping your blood sugar normalized (see Step 3), avoid fatty foods that are fried, barbecued, grilled, roasted, sautéed, broiled, seared, or toasted. Dry heat causes AGE formation to increase ten- to a hundred-fold. Foods highest in AGEs are red meat, fried eggs, butter, cream cheese and other particular cheeses, and highly processed products. So even if your diet seems healthy, you may unwittingly consume unhealthy amounts of AGEs because of how your food is cooked.

Step 2. Mind your eating atmosphere (and with whom you eat).

The sad fact is that 20 percent of Americans eat regularly in their cars. Twenty percent! Our genes are not designed for eating in the atmosphere of a toxin-filled vehicle. We were built and evolved to eat with people we love. In fact, science shows that as you get older, the people with whom you eat is just as important as what you eat. More social integration around meals protects you from losing your marbles as you get older.113 The worst situation is older women eating alone with compromised nutrition. The takeaway: get the nutrition you need and eat your meals with people you enjoy.

Step 3. Normalize your blood sugar.

High blood sugar crashes your memory, processing speed, attention, and executive function. Even conventional scientists recommend earlier intervention in the prediabetes phase.114 Most people with blood sugar problems like prediabetes have no idea, so start here with a blood test. If your hemoglobin A1C or fasting glucose are not in the optimal range, pay attention, because this is the biggest driver of current and future cognitive decline. Remember that if you control your blood sugar, you can prevent 60 percent of the cognitive decline that occurs as you age.115 At the risk of sounding like a broken record, here’s what you can do to improve blood sugar levels (note that many of these strategies are the same as the memory diet in Step 1):

- Control your carb intake. Carbohydrates are broken down into glucose, which raises blood sugar levels. Reducing carb intake can help normalize blood sugar. Define your carb threshold as described in chapter 3 and commit to staying under your threshold. Implement portion control.

- Perform intermittent fasting, ideally the 16/8 protocol as described here, five to seven days per week.

- Sleep seven to eight and a half hours every night. One night of bad sleep will raise your blood sugar. See additional tactics in Step 4.

- Increase your fiber intake, such as by eating one to two pounds of vegetables per day.

- Exercise regularly.

- Drink filtered water and stay hydrated.

- Monitor your stress levels. Chronically high perceived stress raises cortisol and blood sugar.

- Discuss with and order from your clinician an insulin/glucose challenge test. In general, I suggest that if you have any memory issues (or weight or fat gain), you track your blood sugar level and aim for the optimal zone (see Notes for details116). It may take more than forty days to reset your blood sugar, depending on where you start and previous damage to metabolism.

- Consider the use of supplements such as berberine, chromium, cinnamon, and fenugreek.

Step 4. Make the other lifestyle changes that balance your hormones and improve metabolic flexibility.

- Get a good night’s sleep, ideally seven to eight and a half hours per night, to store memories and think clearly the next day. This will help you make adequate hormones.

—If you can’t seem to sleep more, try camping or being out in nature. A study from the University of Colorado showed that one weekend of backcountry camping with natural light—sunlight, moonlight, firelight, and flashlights (no other artificial lights, including personal electronics, were allowed) helped reset melatonin so that sleep began earlier (by two and a half hours). It shifted the circadian rhythm by 69 percent. The camping itself probably has less of a benefit than being in nature and sleeping when the sun sets and waking with sunrise.

—For women, sleep in a room at 64 degrees Fahrenheit or cooler. I’ve written about how temperature control helps women sleep better as they age, but often 64 degrees is too cold for their sleeping partners. Another strategy is to cool your bed on a local level using something like the ChiliPad, which can serve as a mattress pad on your side of the bed or under your pillowcase. It allows you to dial in the best temperature for your sleep, with a range from 55 to 110 degrees.

- Napping is another pathway to memory consolidation. A nap of twenty to ninety minutes appears to be ideal, according to one study—though medical opinions vary and naps seem to benefit younger more than older adults.117 If you’ve read my previous books, you know that I’m a fan of the siesta because it reduces sleepiness, improves memory, prepares you for learning, enhances cognitive function, and boosts emotional stability, regardless of whether you obtained sufficient sleep the night before.118 Duration matters: brief naps of fewer than fifteen minutes provide immediate benefits that last up to three hours, whereas naps of thirty minutes or longer can cause sleep inertia (grogginess) when you first awaken, and may interfere with deep (non-dream) sleep at night, but then provide cognitive improvement for longer, up to many hours.119 One of the best ways to reap the brain/body benefits of naps is to sleep for up to thirty minutes, then exercise afterward to wake up.120

- Detoxify your environment from mold, mercury, aluminum, PCBs, and lead (see chapter 2).

Step 5. Exercise for memory.

- Physical. Strength or resistance training improves memory and cognition.121 It raises testosterone and growth hormone to help you grow new nerve cells.122 A single bout of high-intensity interval training improves memory in women.123 Modest increases in physical activity in the range of 10 percent can significantly reduce the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.124 Multiple modalities are best, and women may benefit from the cognitive effects on executive function, including memory, more than men.125 Exercise boosts the size of the brain, particularly the hippocampus, counteracting the shrinking effect of age. Additionally, exercise boosts BDNF, which promotes neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and blood flow to the brain. Recommendation: a minimum of 150 minutes of moderate or HIIT exercise per week. That’s just thirty minutes a day for five days a week!

- Mental. Bilingualism or multilingualism builds cognitive reserve and protects your brain from aging.126

- Spiritual. Meditation, yoga, and alternate nostril breathing all help memory.

—Meditation can increase blood flow in the brain and improve memory, even in older folks with age-related memory loss, mild cognitive impairment, and early Alzheimer’s disease.127 A ten-day mindfulness retreat enhanced the capacity of working memory, improved attention, and lowered anxiety, negative mood, and depression of participants, and a four-day mindfulness retreat improved working memory for people who hadn’t previously meditated.128

—Kundalini yoga boosts executive function in people with mild memory impairment. Yoga two to four times per week for thirty minutes or longer was very helpful to Jane, and I recommend that for you, along with several of the supplements mentioned in the next step of the Brain Body Diet. Add in the silent chanting of a mantra, usually part of kundalini but also simple to do on your own for a few minutes, to activate the hippocampus.129

—Left nostril breathing stimulates memory in the right brain hemisphere, and right nostril breathing seems to help with numerical data retrieval as a result of left-brain activation—and benefits occur after thirty minutes for four consecutive days.130

YOGA FOR MEMORY: EASY POSE WITH THREE LOCKS

When I practice kundalini yoga, my final pose before Corpse pose (Sivasana) is Easy pose with application of the three energetic locks. I think of the locks as locking in memory, especially if it’s leaky. Yogi Bhajan, the charismatic teacher from Pakistan who brought kundalini yoga to the West in 1968, taught this kriya as part of a practice for memory in 1969.131

The three locks together are called Maha Bandha: Mula Bandha (root lock) is where you pull up your pelvic floor, like you’re trying to stop the flow of urine; Uddiyana Bandha (diaphragm lock) is where you keep lips closed and pull abdominal muscles and organs upward toward the thoracic spine; and Jalandhara Bandha (neck lock) is where you tuck your chin toward chest, pressing into the front of the neck.

- Sit in Easy pose, with knees bent and legs crossed. Lengthen your spine from sit bones to crown.

- Breathe long and deep for three minutes. Keep your eyes closed.

- Deeply inhale, holding your breath at the top of the inhale, and apply the three locks, starting first with Mula Bandha, then Uddiyana Bandha, and then Jalandhara Bandha. Hold as long as is comfortable, trying ten seconds to longer.

- Then release in the reverse sequence: Jalandhara Bandha, Uddiyana Bandha, and Mula Bandha.

- Sit quietly and breathe before taking Sivasana.

Step 6. Supplement your memory.

Start with just one for two weeks, then add a second if your memory still needs help. If you are taking prescription medications, talk first with your pharmacist about any interactions.

- Bacopa has been used for thousands of years in Ayurvedic medicine to enhance memory, relieve pain, and treat epilepsy. Bacopa protects cells in the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and striatum against toxicity and DNA damage, which are commonly implicated in Alzheimer’s disease.132 Several studies show that it improves memory, verbal learning, retention, and information processing in healthy people.133 Bacopa improves synaptic plasticity when taken for up to twelve weeks.134 Dose: 250 to 500 mg, twice daily. Side effects include palpitations, dry mouth, nausea, thirst, and fatigue.

- Citicoline is the exogenous version of the natural intracellular precursor of phosphatidylcholine135 and boosts neuroplasticity. Citicoline promotes neurogenesis and has been shown to help memory impairment, especially of vascular origin—such as from stroke or vascular dementia.136 Initially developed for the treatment of stroke, it can be used to improve memory and even has the support of the Cochrane collaboration’s systematic review.137 There are limited data supporting citicoline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.138 Dose: 500 to 2,000 mg per day.

- Curcumin improves memory in patients without dementia, according to a randomized trial lasting eighteen months.139 This result confirms previous trials showing a benefit to working memory and attention within one hour of curcumin dose. Bioavailable curcumin can help working memory and attention within one hour.140 Dose: 90 mg twice per day.

- Huperzine A seems to improve memory across the age span. It is an alkaloid isolated from Chinese club moss, Huperzia serrata, an inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase (an enzyme that breaks down the neurotransmitter acetylcholine) that is said to help both central and peripheral activity with the ability to protect cells against hydrogen peroxide, amyloid beta protein (or peptide), glutamate, and stroke. It has been shown to improve memory in healthy adolescents.141 Multiple randomized trials suggest that Huperzine A is effective in improving memory and other outcomes in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia.142 Dose: 200 mcg per day.

- Omega-3s. More than twelve good-quality randomized trials have been published on the effect of omega-3 fats (DHA + EPA or DHA) on cognition and memory. Overall, participants with mild cognitive impairment gained a modest benefit from omega-3 supplements, especially for immediate recall, speed, and attention.143 However, not all trials show a benefit.144 DHA quells inflammation, improves memory, and prevents neurodegeneration in conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease.145 DHA increases production of BDNF, which helps enhance the structure and function of brain cells. Dose: 900 to 1,700 mg per day of DHA and EPA. The most proven form for memory is derived from marine algae. I suggest taking it for six months at a dose of at least 900 mg per day.

- Phosphatidylserine (PS) is one of my favorite memory supplements because it is like a cleanup crew. Multiple trials show that PS improves memory, attention, arousal, and verbal fluency in aging folks with cognitive decline.146 It seems to work best in patients with good cognitive function at baseline. The majority of studies are positive, but not all.147 Benefits seem to fade after sixteen weeks when combined with other treatments,148 so think of it as a “pulse” to boost your memory. Dose: 300 to 800 mg per day.

- Vitamin D calms down neuroinflammation by reducing cytokines (the weapons of the immune system that cause damage in the brain body).149 The ideal dose is based on your genetics and sun exposure, so the best strategy is to measure 25-hydroxy vitamin D in your blood after taking a consistent dose. Aim to get enough vitamin D to keep serum level at 60 to 90 ng/mL, associated with optimal sleep and the lowest risk of dementia. Dose: 2,000 to 5,000 IU/day, but the best strategy given the multiple genes involved in vitamin D metabolism is to track your blood level over time and to get out into the sun for thirty minutes per day.

- DHEA is an important sex hormone that is made in the brain and adrenal glands. It has many important jobs in the brain body, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, BDNF-raising, stress-buffering, and antiaging activities.150 However, taking DHEA does not seem to improve memory in people over the age of fifty.151 There may be a window of time during which taking DHEA is helpful, such as in younger women before the age of fifty, but the data are mixed.152

- Other. Additional supplements are found in the Notes, including acetyl-L-carnitine, cinnamon, magnesium L-threonate, and pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ).153

ADVANCED PROTOCOL

If your memory is not better within two weeks, add one or more of the steps of the Advanced Protocol.

Step 7: Initiate hormone therapy.

Since hormones decline in middle age, does it help memory and general cognitive ability to add back sex hormones as you lose them, such as estrogen in women and testosterone in men? The answer is, “It depends.”

- Estrogen as bioidentical hormone replacement could be beneficial for some women (see the sidebar here).

- Testosterone seems to enhance memory encoding in men but not women,154 and though animal studies suggest that testosterone helps memory and cognition,155 the data on the role of supplemental testosterone in men with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease have been mixed.156 However, one small trial suggested that testosterone therapy in women may improve postmenopausal verbal learning and memory.157

Test your hormones, including thyroid, estrogen, progesterone, and cortisol—and then work with your clinician to adjust in a way that makes sense for your situation.

Step 8: Perform computer-based cognitive training.

Computer-based cognitive training is growing in popularity and seems to be more effective than any pill. Evidence is moderate that cognitive training in adults with normal cognition improves memory, reasoning, and processing speed. In a meta-analysis of fifty-two studies, computer-based cognitive training improved nonverbal, verbal, and working memory.158 The benefit seems to last two to five years, with the memory benefits fading by ten years post-training.159

There are many approaches to enhance memory with the help of a computer or app: brain training programs, working memory training programs, and video games.160 The best tested are Elevate, Lumosity, Fit Brains, Brain HQ, and Brain Workshop. Many are effective in as little as ten to twenty minutes per day, five times per week, and four of the five (at time of publication) can be downloaded and used on your smartphone.

Last Word

It’s time to rewrite the future of your brain body. Memory decline need not be in the cards for you. A little forgetfulness is normal, but in my case, the right diet, intermittent fasting (described in chapters 2 and 3), social eating, phosphatidylserine, plus high-dose vitamin D worked wonders on my own memory. Simple fixes like eating a diet rich in vegetables, nuts, and fish—along with making sure you get enough sleep and exercise—can go a long way toward making your brain bigger as you age and improving your cognitive function, whether you’re middle-aged and just becoming aware of your forgetfulness, or you’re older and fearing gradual decline.

Memory will never be perfect. But when consistent issues arise, take a closer look at the way you eat, move, think, and supplement—and, most important, make your brain/body relationship a priority. The challenge is to identify the brain/body issues that are causing neurodegeneration and memory loss. Once identified, they can be remedied with an integrated approach.