Vesiculobullous and Selected Pustular Disorders

The focus of this chapter is a group of conditions that result in vesicle or bulla formation. Not all bullous disorders are included here; some are listed according to etiology. Thus, intraepidermal vesicles due to spongiosis are discussed in Chapter 1, viral vesicles (particularly those due to herpesvirus infections) are discussed in Chapter 17, and bullae of porphyria cutanea tarda are included in Chapter 9.

Vesicles and bullae can arise at various levels within the skin, from the stratum corneum to the superficial dermis. Many of them develop in or near the basement membrane zone, a complex structure (as defined ultrastructurally and by antibody studies) that is located between the epidermis and papillary dermis. The major components of this zone, moving from basal keratinocytes toward the dermis, are the hemidesmosome, composed of tonofilaments that insert into an attachment plaque; the lamina lucida, within which can be found a subdesmosomal dense plate and anchoring filaments; the lamina densa; collagen rootlets; and anchoring fibrils. Abnormalities of these structures, whether resulting from genetically determined alterations, mechanical factors, or autoimmune attack, can lead to a separation that appears to be subepidermal, and the level at which separation occurs can be crucial in determining diagnosis, therapeutic options, and prognosis. Diagnosis can often be made on routine light microscopy, with an assist from direct or indirect immunofluorescence, but on occasion, particularly when attempting to determine subtypes of epidermolysis bullosa, ultrastructural evaluation and more sophisticated mapping studies may be necessary.

A significant portion of this chapter will consider a group of autoimmune diseases, often referred to as immunobullous disorders. In addition, topics of discussion will include some pustular eruptions of infancy and adult life, heritable forms of epidermolysis bullosa, inherited and acquired abnormalities of cell-to-cell adhesion, and traumatically induced blisters.

Immunobullous Disorders

Clinical Features

The term pemphigus defines a groups of disorders characterized by the formation of acantholytic blisters that leave denuded areas and involve both skin and mucous membranes. Blisters result from an autoimmune attack on target antigens that are related to components of desmosomes within epithelia—epidermis, mucosa, and adnexal epithelium. The prototype condition of this group, pemphigus vulgaris, shows extensive flaccid blistering of trunk, groin, axillae, and scalp, as well as erosions of mucous membranes. The target antigen is desmoglein 3.1 Blisters have the property of spreading following trauma, such as pressure or twisting; this phenomenon is variably known as the Nikolsky or Asboe-Hansen sign. Extensive loss of fluid and electrolytes and secondary infection can accompany this often severe and persistent disease. Other variants of pemphigus include

• Pemphigus vegetans: a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris in which vegetative plaques develop over intertriginous areas. Most often, this form is a phase that occurs during the course of pemphigus vulgaris.

• Pemphigus foliaceus: an often sporadic form of the disease that is endemic in parts of South America, where it is referred to as fogo selvagem or Brazilian pemphigus.2 It produces shallow erosions and crusted plaques but can undergo transition to pemphigus vulgaris. Oral lesions are rarely observed. The target antigen is desmoglein 1, which is concentrated in desmosomes of the more superficial epidermis.3

• Herpetiform pemphigus: considered a variant of pemphigus foliaceus, although sometimes antibodies to desmoglein 3 (as found in pemphigus vulgaris) can be demonstrated.4 This variant features grouped blisters; this arrangement mimics that seen in herpes viral vesicles.

• Pemphigus erythematosus (Senear-Usher disease): features erythematous, erosive lesions, often involving the malar areas of the face. It shares that clinical feature as well as some immunofluorescent and serologic characteristics with lupus erythematosus (LE).5,6

• Paraneoplastic pemphigus: consists of erosions of the lips and oropharynx, pseudomembranous conjunctivitis, and pruritic skin lesions with blisters and erosions, some of which have a target-like configuration reminiscent of erythema multiforme. There are multiple desmosomal target antigens in this disease, including desmoplakin I (250 kD), the major bullous pemphigoid antigen (230 kD), envoplakin (210 kD), and periplakin (190 kD).7,8 Paraneoplastic pemphigus has a strong association with lymphoproliferative disorders, including T-cell and B-cell lymphomas, thymoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and Castleman disease.9

• Immunoglobulin A (IgA) pemphigus: presents in two forms—one resembles subcorneal pustular dermatosis,10 and the other, called intraepidermal neutrophilic IgA dermatosis, has herpetiform lesions.11 In the subcorneal pustular dermatosis variant, desmocollins are often the target antigens,12 whereas in the intraepidermal neutrophilic IgA dermatosis variant, antibodies to desmogleins 1 and 3 are found.13 The subcorneal pustular dermatosis type may be associated with a monoclonal IgA gammopathy.

Treatment for pemphigus vulgaris, and sometimes the other variants, includes corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive agents. Systemic corticosteroids are sometimes used as the initial approach, followed by other agents, such as azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil, used for their steroid-sparing therapeutic properties.

Microscopic Findings

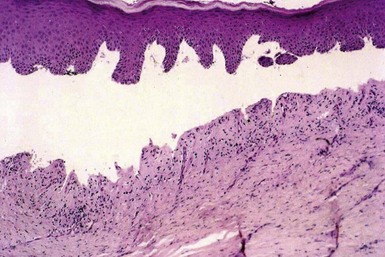

On biopsy, pemphigus vulgaris may show intraepidermal vesicles with eosinophilic spongiosis (Fig. 4-1) in early stages,14 but eventually suprabasilar acantholysis can be identified (Fig. 4-2). The basilar keratinocytes remain attached to the floor of the separation but appear to separate from one another, producing the so-called “row of tombstones” appearance (Fig. 4-3). A few acantholytic cells are identified within the blister.15 The process involves adnexal structures in the vicinity of the lesions, and at times, extensive acantholysis of follicular epithelia is apparent (Fig. 4-4). The dermal infiltrate contains a mixture of inflammatory cells, but often a few eosinophils are identified.

Figure 4-2 Pemphigus vulgaris.

Fully developed lesion, showing suprabasilar acantholysis. Only a few acantholytic cells are seen in the blister cavity.

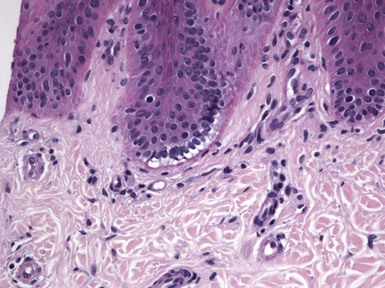

Figure 4-3 Pemphigus vulgaris.

The basilar keratinocytes separate from one another, producing the appearance of a “row of tombstones.”

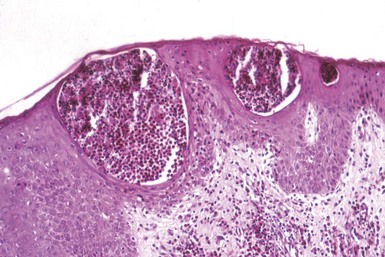

Figure 4-4 Pemphigus vulgaris.

This lesion shows extensive acantholytic changes in follicular units. This is in marked contrast to Hailey-Hailey disease, in which follicular sparing is the rule.

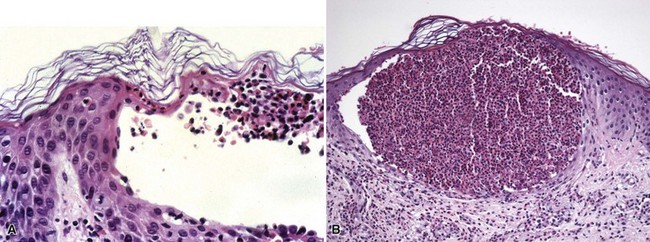

In variants of pemphigus, other microscopic findings occur. Pemphigus vegetans is characterized by hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis with intraepidermal collections of eosinophils (Fig. 4-5); acantholytic foci are not always demonstrable.16 Pemphigus foliaceus shows an intraepidermal vesicle with separation occurring in or near the granular cell layer (Fig. 4-6). At times, the picture is more an erosive than a bullous one, and acantholysis may be subtle, seen best at the edge of the specimen or near follicular ostia. Eosinophilic spongiosis may be present. Pemphigus erythematosus microscopically resembles pemphigus foliaceus (Fig. 4-7). In contrast to other forms of pemphigus, paraneoplastic pemphigus often shows a lichenoid tissue reaction that somewhat resembles erythema multiforme, and acantholysis may or may not be identified (Fig. 4-8). In the two forms of IgA pemphigus, one resembles subcorneal pustular dermatosis (see later discussion), whereas the other, intraepidermal neutrophilic IgA dermatosis, consists of intraepidermal pustules (Fig. 4-9). Slight acantholysis can be seen in the subcorneal pustular dermatosis variant.

Figure 4-5 Pemphigus vegetans.

Intraepidermal collections of eosinophils. In this example, acantholysis is inapparent.

Figure 4-7 Pemphigus erythematosus.

Acantholysis has occurred in the superficial portion of the epidermis.

Figure 4-8 Paraneoplastic pemphigus.

Vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer is seen on the right side of the figure, whereas acantholysis leading to suprabasilar separation has occurred on the left.

Figure 4-9 Immunoglobulin A (IgA) pemphigus.

Intraepidermal pustules have formed in this variant, known as intraepidermal neutrophilic IgA dermatosis.

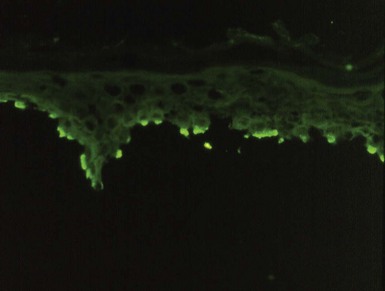

Immunofluorescence (IF) studies, particularly direct IF but to a lesser extent indirect IF, play an important role in the diagnosis of pemphigus. On direct IF, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus vegetans, and paraneoplastic pemphigus show intercellular IgG and C3 deposition involving the full thickness of epidermis (Fig. 4-10), although sometimes staining of upper layers of the epidermis may be diminished. This staining may be linear (producing the so-called “chicken wire” appearance) or particulate. In pemphigus foliaceus, intercellular staining for IgG and C3 is sometimes restricted to superficial portions of the epidermis,17 reflecting the primary location of the target antigen, desmoglein 1. However, in some cases staining of the full thickness of epidermis is seen, in the manner of pemphigus vulgaris. In fact, the majority of the author’s cases of pemphigus foliaceus have shown the latter staining pattern. Pemphigus erythematosus may show staining of the basement membrane zone, resembling a “lupus band,” in addition to intercellular epidermal fluorescence.18 This IF finding may occur even in the absence of clinical or serologic evidence suggesting LE. Similar direct IF findings can be seen as well in paraneoplastic pemphigus. Intercellular IgA deposition is seen in cases of IgA pemphigus (Fig. 4-11).

Figure 4-10 Pemphigus vulgaris, direct immunofluorescence.

Intercellular immunoglobulin G deposition involves most of the epidermis.

Figure 4-11 IgA pemphigus, direct immunofluorescence.

This specimen shows intercellular deposits of IgA.

Indirect IF has been commonly used in the diagnosis of pemphigus, particularly pemphigus vulgaris, but it also has been used as a means of following the course of the disease. The procedure involves layering of various dilutions of patient sera on an epithelial substrate, staining with anti-human IgG antibodies, and determining the antibody titer by finding at what dilution intercellular fluorescence can no longer be detected in the substrate. It is known that antibody titers reflect disease activity. However, they do not always predict disease activity, and therefore many consider clinical evaluation of the patient a better means of assessment.19 Regarding the diagnostic uses of indirect IF in pemphigus, there has been some controversy about whether direct or indirect IF methods are more reliable. Advocates of indirect IF argue that the statistics favor this method when the proper substrate is used, and the best substrate is considered to be monkey esophagus. There are certainly selected situations in which indirect IF might be preferable (e.g., in patients who have only mucous membrane disease, where blood drawing might be a technically easier procedure, or very young or elderly patients who might tolerate obtaining of a blood sample better than a skin biopsy). False-positive pemphigus-like antibodies can be encountered in patients with extensive burns, penicillin-associated drug eruptions, or high-titer blood group antibodies.20 Usually, however, these antibodies are only seen in low dilutions. Indirect IF studies are also not invariably positive; this is particularly true in some patients with pemphigus foliaceus, and they are also positive in only 50% of cases of IgA pemphigus. Indirect IF also can assume great diagnostic importance in cases of paraneoplastic pemphigus, because (unlike other forms of pemphigus), intercellular fluorescence can be found when murine bladder epithelium is used as the substrate.

Differential Diagnosis

Pemphigus vulgaris can be potentially confused with other acantholytic disorders, particularly Hailey-Hailey disease (familial benign chronic pemphigus), an inherited acantholytic disorder, and a similar but localized disorder that appears to be acquired, acantholytic dermatosis of the genitocrural region. However, those conditions usually show much more extensive suprabasilar acantholysis, with separation of keratinocytes in the spinous layer producing the appearance of a “dilapidated brick wall.” Some dyskeratosis can be seen in Hailey-Hailey disease, a feature not seen to the same extent in pemphigus. Importantly, the acantholysis in Hailey-Hailey disease “respects” the hair follicles; that is, follicular epithelia in acantholytic lesions tend to be spared. This is not the case in pemphigus. Dermal infiltrates containing eosinophils are common in pemphigus, and eosinophilic spongiosis may be seen in early disease. This cell type is less common in Hailey-Hailey disease, but eosinophils can occasionally be seen in that disease. Hailey-Hailey disease is not associated with eosinophilic spongiosis. Examples of focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, particularly transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease), can have a pemphigus vulgaris–like configuration, but often some dyskeratosis can be identified. Actinic keratoses with marked acantholysis might occasionally mimic a lesion of pemphigus vulgaris, but some basilar keratinocyte atypia can usually be identified, and the clinical presentation would be quite different from that of pemphigus. IF studies would be definitive, because none of these other conditions shows positive intercellular fluorescence.

The diagnosis of other forms of pemphigus may be difficult. Pemphigus vegetans may bear a superficial resemblance to blastomycosis-like pyoderma, which had previously been termed pyoderma vegetante of Hallopeau or, misleadingly, the Hallopeau variant of pemphigus vegetans. However, that lesion does not show acantholysis, produces negative IF findings, and actually more closely resembles North American blastomycosis microscopically than it does true pemphigus vegetans. In addition, eosinophils are particularly prominent in pemphigus vegetans. Pemphigus foliaceus can be confused with bullous impetigo and subcorneal pustular dermatosis because of the level of splitting—subcorneal, often through the granular cell layer. Pemphigus foliaceus tends to be less pustular than those two diseases, with occasional exceptions, such as some cases of herpetiform pemphigus. Acantholysis is usually, but not always, more evident in pemphigus foliaceus, and occasionally, suprabasilar acantholysis can also be observed. Direct IF can permit a definitive diagnosis; in these diseases, positive intercellular IgG and C3 staining is seen only in pemphigus foliaceus. The same superficial epidermal acantholysis is also characteristic of pemphigus erythematosus, and this permits separation from LE, which pemphigus can resemble both clinically and, partially, on direct IF, since a “lupus band” may be observed. Paraneoplastic pemphigus shows changes resembling erythema multiforme, but most often there are at least foci of suprabasilar acantholysis, and intercellular staining on direct IF is confirmatory of the diagnosis. The morphologic findings of the subcorneal pustular dermatosis–like variant of IgA pemphigus can be virtually identical to those of the disease it resembles. In fact, subcorneal pustular dermatosis may be undergoing redefinition as an entity (see subsequent discussion). However, there are clearly examples of a subcorneal pustular eruption that lack positive intercellular IgA deposition on direct IF study. It would appear that, for this variant of pemphigus, IF studies are essential.

Bullous Pemphigoid

In the early 1950s, Lever distinguished this condition, sometimes simply referred to as pemphigoid, from pemphigus and established it as a separate entity. It is most common among elderly adults, but it can clearly also occur in younger age groups. Although often arising for no apparent reason, it has been associated with certain drugs, including penicillins, sulfur-containing agents, and beta blockers.21 Ultraviolet light exposure has been known to trigger pemphigoid; this has been noticed with the use of ultraviolet therapy and has even been exploited in the experimental elicitation of pemphigoid lesions.22 It also appears that other conditions that can affect the dermal-epidermal junction, such as lichenoid dermatoses or erythema multiforme, can lead to secondary development of pemphigoid due to a phenomenon called epitope spreading.23,24

Most often, tense bullae form over the trunk and intertriginous areas as well as extremities. Blisters can develop in either normal or erythematous skin, and urticarial lesions can sometimes be an early manifestation of the disease. Mucous membrane lesions occur, and disease localized to the lower extremities is occasionally evident. The target antigen of pemphigoid is a 230-kD protein, known as the major pemphigoid antigen, along with a 180-kD protein, known as the minor pemphigoid antigen. These are components of the hemidesmosome complex of the basement membrane zone, the area where subepidermal separation occurs. There are also variants of pemphigoid, whose target antigens reside in the lower portion of the lamina lucida, with molecular weights of 105 kD and 200 kD.

Treatment includes topical and systemic corticosteroids. Tetracycline and niacinamide, dapsone, immunosuppressive therapy, and plasmapheresis may also be useful.

Microscopic Findings

The essential biopsy finding of a fully developed lesion is subepidermal separation. Eosinophilic spongiosis may be an early change in pemphigoid, just as is the case with some examples of pemphigus (Fig. 4-12). Lesions can be sorted into two basic histopathologic configurations: “infiltrate-poor,” in which there may be only a few inflammatory cells, including eosinophils around dermal vessels25 (Fig. 4-13), and “infiltrate-rich,” showing edema and a prominent perivascular and periadnexal infiltrate that usually includes numerous eosinophils (Fig. 4-14). At times, papillary neutrophilic or eosinophilic microabscesses may be present.26 The changes in very early lesions may be quite subtle, resembling ordinary urticaria, whereas in late, resolving lesions, re-epithelialization may obscure the most diagnostic finding, that of subepidermal separation.

Figure 4-12 Bullous pemphigoid.

This lesion shows eosinophilic spongiosis. A few eosinophils can be found within this intraepidermal vesicle.

Figure 4-14 Bullous pemphigoid, infiltrate-rich type.

Numerous eosinophils are seen within the blister cavity.

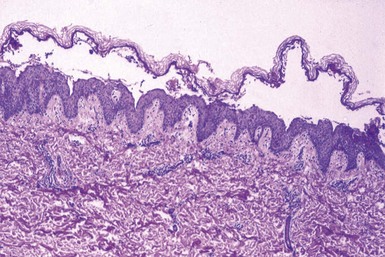

Direct IF study shows linear deposition of IgG and C3 along the dermal-epidermal junction of perilesional skin27 (Fig. 4-15). There may be a continuous band or a discontinuous staining pattern, resembling a “hash line” and often called the interrupted linear pattern of immunofluorescence (Fig. 4-16). The latter emphasizes the hemidesmosomal focus of the immune attack in this disease. IgG is positive in most cases, but not infrequently linear C3 deposition is either the only finding or is much more pronounced than IgG deposition. Other immunoglobulins, particularly IgA, may also be positive, but they are typically weaker than IgG, an important diagnostic clue. The author has occasionally observed examples of pemphigoid in which basement membrane zone fluorescence includes an intercellular component among basilar keratinocytes. False-negative IF studies may occur in up to one third of cases of pemphigoid when biopsies are obtained from the lower extremities.28 The selection of perilesional skin for IF study is important, because biopsies containing only blistered skin may be negative or nonspecific. Indirect IF, using monkey esophagus substrate, shows linear basement membrane zone fluorescence in about 70% of cases. Unlike pemphigus, antibody titers performed by indirect IF do not correlate with disease activity.

Differential Diagnosis

At the early stage of eosinophilic spongiosis, pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris can certainly resemble one another. However, direct IF allows clear separation of the two, and the acantholytic appearance that defines classic pemphigus is not confused with the subepidermal separation of pemphigoid. Reliable differentiation from cicatricial pemphigoid with cutaneous involvement, or pemphigoid (herpes) gestationis, may not be possible, and they are widely considered variants of the same disease. However, cicatricial pemphigoid may actually be a complex of diseases that includes the mucosal variant of linear IgA disease and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita as well as pemphigoid. This may allow differentiation based on direct IF methods (see later discussion). In addition, cicatricial pemphigoid tends to show more neutrophils than eosinophils and a greater degree of scarring than ordinary pemphigoid.

A significant differential diagnostic problem can arise in differentiating pemphigoid from epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, because there can be overlapping clinical as well as microscopic features (see subsequent discussion). Both conditions can show linear IgG and C3 deposition along the dermal-epidermal junction. However, the target antigens differ. In epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, antibody binds to type VII collagen, a component of anchoring fibrils that are found below the lamina densa of the basement membrane zone. In pemphigoid, the target antigen is the hemidesmosome complex, above the lamina densa. This difference can be exploited by a procedure known as saline splitting. Tissues incubated in normal saline separate through the lamina lucida of the basement membrane zone. If the separated tissues are stained with antibodies to IgG, linear fluorescence is seen at the floor of the separation in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, whereas bullous pemphigoid shows linear staining along the roof of the separation, or sometimes along both the roof and the floor. Only rarely is staining in pemphigoid found only along the floor of the separation; these are probably examples of the rare anti-p200 pemphigoid, whose target antigen resides in the lower lamina lucida of the basement membrane zone.29 Saline splitting can be performed either as part of a direct or indirect IF procedure. The author has most often used this method in direct IF, with very reliable results.

Pemphigoid gestationis shows considerable microscopic overlap with pemphigoid, although there may be pronounced edema of dermal papillae (“teardrop-shaped” papillae). On direct IF, pemphigoid gestationis is more apt than pemphigoid to show only linear C3 deposition along the junctional zone, and indirect IF studies are typically negative unless a complement-enhanced procedure is performed (see later discussion). A major distinction is that pemphigoid, in the author’s experience, is distinctly unusual in young adults. This is highlighted by a recent case in a woman in the third decade of life, who had a bullous disease, deposition of linear basement membrane zone IgG and C3, and no known history of pregnancy. Further investigation showed that she had an “aborted” pregnancy several months earlier, markedly elevated human chorionic gonadotropin levels, and, in addition, an undetected choriocarcinoma. Linear IgA disease can closely resemble pemphigoid and on biopsy can show papillary neutrophilic microabscesses. However, elicitation by drug (e.g., vancomycin) can often be shown, and the positive linear IgA deposition that defines the disease is regularly found on direct IF study. Similarly, papillary neutrophilic microabscesses are a hallmark of dermatitis herpetiformis, but direct IF study shows granular IgA deposition (often accompanied by C3 and fibrin) along the basement membrane zone, often concentrated at tips of dermal papillae. Erythema multiforme has a distinct set of microscopic changes (vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer, apoptotic body formation at all levels of the epidermis, and a mild upper dermal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate) and shows negative or nonspecific findings on direct IF study. However, the author has seen examples of erythema multiforme evolving into bullous pemphigoid, probably as a result of epitope spreading.

Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

This is an unusual bullous eruption occurring in patients with lichen planus. It does not represent blistering in a lesion of lichen planus due to extensive vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer, although that phenomenon also occurs (see Chapter 3). Tense bullae develop in areas of skin not directly involved with lichen planus lesions but can also occasionally incorporate these lesions. Despite a close resemblance to pemphigoid, lichen planus pemphigoides has a different target antigen30: a 200-kD protein, as well as the minor 180-kD pemphigoid antigen.31 Microscopically, there is a subepidermal bulla with a mild perivascular infiltrate that may be composed of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and/or neutrophils (Fig. 4-17). More typical lichenoid tissue changes can sometimes be identified. With direct IF, linear IgG and C3 deposition are identified along the dermal-epidermal junction, and linear staining is also visible on indirect IF.32 Using the saline splitting procedure, staining of the roof of the resulting separation occurs, in a manner similar to pemphigoid.

Pemphigoid (Herpes) Gestationis

Pemphigoid gestationis, formerly known as herpes gestationis, is an eruption of pregnancy that typically begins in the second or third trimester as urticarial plaques with the evolution of blisters over the trunk and extremities. It usually subsides shortly after parturition, but it may develop progressively earlier with succeeding pregnancies, and it may continue to flare, following a pregnancy, with menses, or on oral contraceptives.33 Reportedly, an association with choriocarcinoma has occurred on a number of occasions.34 Transplacental transfer to the infant also can occur, but it is apparently not associated with an increased risk of fetal mortality, as had been believed in the past.35,36 The target antigen is the 180-kD minor bullous pemphigoid antigen, believed to be a component of type XVII collagen.

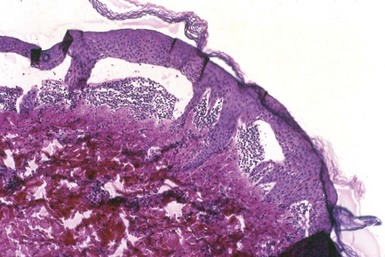

Microscopic Findings

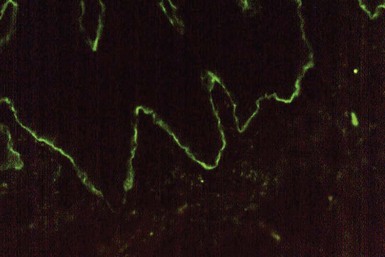

On biopsy, there is papillary dermal edema, sometimes producing “teardrop-shaped” dermal papillae (Fig. 4-18). Subepidermal separation may ensue, associated with basal cell degeneration. A perivascular lymphocytic and eosinophilic infiltrate is also present.37 As in bullous pemphigoid, eosinophilic spongiosis can occur, particularly in early lesions.14 Direct IF regularly shows linear C3 deposition along the dermal-epidermal junction (Fig. 4-19), and IgG staining is less frequent (much less frequent, in the author’s experience).38 Saline splitting shows staining of the roof of the separation, as in bullous pemphigoid. Indirect IF is usually negative when performed in the usual way, but a procedure known as complement-enhanced indirect IF can show basement membrane zone complement deposition. This technique involves adding a source of complement (such as normal human serum) to the indirect IF protocol and then staining the treated substrate with anticomplement antibody.39 This phenomenon occurs because the circulating immunoglobulin (IgG1 class) is difficult to detect directly but avidly binds complement, and the addition of a complement source thereby enhances the sensitivity of indirect IF testing.

Differential Diagnosis

The microscopic differential diagnosis in early stages can include either urticaria or other conditions characterized by eosinophilic spongiosis. Fully developed blisters are difficult to distinguish from bullous pemphigoid. In the presence of papillary neutrophilic and/or eosinophilic microabscesses, consideration is also given to epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA disease, or bullous LE. The clinical history, usually that of a young woman who is or has recently been pregnant, would heavily favor pemphigoid gestationis, and IF findings would provide strong support. In the author’s experience, bullous pemphigoid is extremely unusual in young persons. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita also favors middle-aged to older adults, and an immunofluorescent procedure with saline splitting would show staining of the floor, rather than the roof, of the subepidermal separation. Dermatitis herpetiformis and linear IgA disease would show, respectively, granular or linear basement membrane zone IgA deposits on direct IF. Bullous LE could certainly occur in a young woman and possibly during pregnancy, and both conditions would show linear IgG and/or C3 basement membrane zone deposition. However, the majority of patients with bullous LE have other clinical or serologic evidence of LE, and again, saline splitting in that disease would show positivity along the floor, rather than the roof, of the subepidermal separation.

Cicatricial Pemphigoid (Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid)

Formerly and somewhat unfortunately called “benign” mucous membrane pemphigoid, cicatricial pemphigoid shows blistering of ocular, oral, or other mucosal surfaces, with resultant scarring.40 Blindness can result in up to 20% of the cases with conjunctival involvement. Cicatricial pemphigoid is also a cause of desquamative gingivitis. Skin lesions can develop in one third of cases, and dermatologic involvement varies from a widespread, nonscarring bullous eruption to intermittent, eruptive disease of the head and neck, particularly the scalp, with atrophic scarring, the so-called Brunsting-Perry variant. Although previously considered a single disease entity, cicatricial pemphigoid may represent a complex of disorders,41 including classic cicatricial pemphigoid (essentially, a mucous membrane variant of bullous pemphigoid), mucosal linear IgA disease, and mucosal epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. The target antigens include the major and minor bullous pemphigoid antigens, epiligrin, or laminin 5 (one component of which is a 100-kD protein), and the β4 subunit of α6β4 integrin, although others have been identified in individual cases.

Microscopic Findings

Microscopic features include a subepithelial bulla and an inflammatory infiltrate that includes lymphocytes and neutrophils with variable numbers of eosinophils; in fact, eosinophils may well be inconspicuous. Subepithelial fibrosis and/or scarring are also evident (Fig. 4-20). Direct IF shows linear basement membrane zone deposition, usually consisting of IgG and/or C3, in perilesional skin or mucosa (Fig. 4-21). Occasionally, linear IgA deposition is encountered, either together with other immunoglobulins or, more rarely, as an isolated finding. Indirect IF may or may not show linear IgG or IgA along the basement membrane zone; the titers may correlate with disease activity. Results of saline splitting procedures vary, depending on the subtype of cicatricial pemphigoid; the bullous pemphigoid–like cases show staining of the roof of the subepidermal separation, whereas the antiepiligrin or laminin 5 cases show staining along the floor of the separation.42,43

Differential Diagnosis

The microscopic differential diagnosis includes many of the subepidermal immunobullous diseases, but the primarily mucosal location of most examples can usually lead to the correct diagnosis. In fact, it may be that cicatricial pemphigoid can represent a “mucosal” subtype of bullous pemphigoid, linear IgA disease, or epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, and direct IF studies can help clarify this relationship. However, it is important to point out that the target antigens of IgA cicatricial pemphigoid may differ from those of cutaneous linear IgA disease, and the same can be said of cicatricial pemphigoid with staining of the floor of a saline split preparation, when compared with epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.

In the author’s experience, a more common diagnostic problem is the categorization of a case of conjunctivitis or desquamative gingivitis as either cicatricial pemphigoid or mucosal lichen planus. There can be considerable overlap in the clinical presentations of these two diseases. The microscopic task is made more difficult by the technical problems inherent in biopsy of these two sites, especially in the case of friable tissue. However, bandlike subepithelial lymphocytic inflammation clearly favors lichen planus, whereas a more mixed inflammatory reaction and scarring tend to favor cicatricial pemphigoid. In this situation, assuming that an intact specimen is submitted, direct IF can be immensely helpful, in that positive linear basement membrane zone IgG, C3, or IgA deposition favors cicatricial pemphigoid, whereas IgM-positive Civatte bodies and a shaggy fibrin band are characteristic of lichen planus.

Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is an acquired immunobullous disease with clinical and, sometimes, histopathologic resemblances to hereditary forms of epidermolysis bullosa. However, it tends to occur frequently in middle-aged to older adults. Acral skin (usually) displays increased fragility and noninflammatory bullae, and scarring and milia formation ensue.44 The lesions can mimic those of pemphigoid, or there can be cicatricial pemphigoid-like mucosal lesions. The target antigen is type VII collagen, a component of anchoring fibrils, and has a molecular weight of 290 kD.

Treatment includes systemic corticosteroids, azathioprine, dapsone, and a variety of other agents.

Microscopic Findings

Microscopically, there is typically an infiltrate-poor subepidermal bulla (Fig. 4-22), but inflammatory lesions contain lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils. Occasionally, some examples display papillary neutrophilic microabscesses (Fig. 4-23). Direct IF shows linear IgG, C3, and sometimes other immunoglobulins along the dermal-epidermal junction. Indirect IF can also show circulating anti–basement membrane zone antibodies. The saline splitting procedure, used in conjunction with either direct or indirect IF methods, usually shows staining of the floor, rather than the roof, of the resulting subepidermal separation.45

Differential Diagnosis

On routine light microscopy, noninflammatory lesions of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita can closely resemble hereditary forms of epidermolysis bullosa, particularly the junctional or dermolytic types. However, heritable forms of epidermolysis bullosa typically begin in infancy and childhood, and IF studies are negative.

The major problem in differential diagnosis is the distinction between epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and bullous pemphigoid of either the infiltrate-poor or infiltrate-rich types. Eosinophils are usually a hallmark of pemphigoid, whereas this is not the case for epidermolysis bullosa acquisita; however, exceptions can occur. IF findings are also quite similar. In the author’s experience, the “interrupted” linear pattern of junctional staining, when present, is generally indicative of pemphigoid, because it reflects the hemidesmosomal location of the target antigen. In situations where continuous linear basement membrane zone fluorescence occurs, the saline splitting procedure is most useful, in that IgG staining is generally visible in the floor of the separation in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita but most often in the roof of the separation in pemphigoid. The same can be said for pemphigoid gestationis although usually the clinical history is decisive. However, pemphigoid can occasionally show staining only in the floor of a saline split preparation; some of these may be examples of anti-p200 pemphigoid. Pang and colleagues emphasized this issue and suggested using invertebrate skin in an indirect IF procedure. Toad skin apparently possesses the bullous pemphigoid and not the epidermolysis bullosa acquisita antigen, and therefore a positive indirect IF procedure using this substrate and patient serum is indicative of pemphigoid.46 An additional theoretical problem is that IF staining of the roof of a subepidermal separation in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita could occur as a consequence of epitope spreading.

It is also possible to confuse examples of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita with papillary neutrophilic microabscesses with dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA disease, or bullous LE. IgA staining of the basement membrane zone, in a granular or linear pattern, favors one of the first two diagnoses. In the occasional situation where epidermolysis bullosa acquisita also displays linear IgA deposition, invariably IgG is also present and is typically expressed more strongly than IgA. Both bullous LE and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita can show deposits of multiple immunoglobulins in linear fashion along the dermal-epidermal junction, and in both cases their target antigens are components of type VII collagen, found in the anchoring fibrils of the sublamina densa zone.47,48 Therefore, the results of saline splitting may be identical in both, showing staining of the floor of the resulting separation. Clinical data supporting the diagnosis of LE would obviously be important, but there are previous reported examples of a bullous disease resembling epidermolysis bullosa acquisita in patients with LE. Therefore, authorities have suggested that the two conditions are closely related or variants of the same process. One additional finding that would point toward a diagnosis of LE in such circumstances is the finding of an antinuclear antibody, along with basement membrane zone fluorescence, on either direct IF or indirect IF testing (see subsequent discussion).

Bullous Lupus Erythematosus

Patients with bullous LE present with asymmetric, nonpruritic, photodistributed bullae. These lesions may occur singly or may be grouped. Patients usually have established systemic LE,49 but skin lesions more typical of LE may not be present, and American College of Rheumatology criteria for the disease may not be met.50 The target antigens are the 290-kD and 145-kD components of type VII collagen, which as previously mentioned is a constituent of the anchoring fibrils of the sublamina densa basement membrane zone.

The lesions are often, but not invariably,51 responsive to dapsone, a drug also used in the management of dermatitis herpetiformis.

Microscopic Findings

The lesions of bullous LE do not display many of the characteristics of typical LE skin lesions but instead show papillary dermal neutrophilic microabscesses and subepidermal separation49 (Figs. 4-24 and 4-25). However, dermal mucin deposition may be detected. This is clearly not the picture one would expect when blisters arise in ordinary lesions of cutaneous LE, in which case separation occurs in the context of extensive vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer and may be accompanied by hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy, and perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic inflammation. Direct IF shows linear or granular IgG, C3, or other immunoglobulins along the dermal-epidermal junction (Fig. 4-26). On indirect IF, basement membrane zone deposits are rarely found, but when present, suggest a link with epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. An antinuclear antibody can be detected in keratinocyte nuclei on either direct or indirect IF (Fig. 4-27). In a few cases, bullous LE has been associated with antiphospholipid antibodies.52

Figure 4-24 Bullous lupus erythematosus (LE).

There is a subepidermal separation with accumulations of inflammatory cells—mostly neutrophils—at the base.

Figure 4-26 Bullous LE, direct immunofluorescence.

This case shows linear immunoglobulin G deposition along the dermal-epidermal junction.

Figure 4-27 Bullous LE, direct immunofluorescence, saline-splitting procedure.

Linear immunoglobulin G deposition is evident along the floor of the resulting subepidermal separation. This outcome would be expected in LE and would also be seen in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. In addition, antinuclear antibody staining can be seen in keratinocyte nuclei. It is possible that intranuclear binding sites were unmasked during incubation in 1 molar NaCl.

Differential Diagnosis

As previously mentioned, the microscopic features are not those of typical LE, making the diagnosis difficult in the absence of clinical and serologic data. Uncommonly, patients with LE may develop a nonbullous neutrophilic dermatosis. Such lesions consist of pruritic papules and plaques, and they show a superficial dermal neutrophilic infiltrate with leukocytoclasis in the absence of vasculitis.53 The differential diagnosis of subepidermal blisters with papillary neutrophilic microabscesses includes dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA disease, some examples of bullous pemphigoid, and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Direct or indirect IF studies may be essential in establishing the diagnosis in each of these disorders. When granular IgA deposition is seen in bullous LE, other immunoglobulins are likely to be present as well, and staining for these is typically at least as intense, or more so, as it is for IgA. The same can be said when there is linear IgA deposition in bullous LE. Saline splitting can be helpful in ruling out pemphigoid, because immunoglobulins in bullous LE would be expected to stain the floor, rather than the roof, of the subepidermal separation. The difficulties in separating bullous LE from epidermolysis bullosa acquisita have been discussed in the previous section. This is particularly the case when linear staining with multiple immunoglobulins is present. Saline splitting is not helpful in this instance, because the target antigens in the two conditions are similar. Again, detection of an antinuclear antibody in epidermal keratinocytes is supportive of the diagnosis of bullous LE. It should also be mentioned that a prozone phenomenon rarely occurs in antinuclear antibody testing54; in at least one such case, performance of a saline splitting procedure unmasked an antinuclear antibody that had been negative by more traditional laboratory methods.

Dermatitis Herpetiformis

Dermatitis herpetiformis presents as a symmetrical eruption involving extensor surfaces, consisting of grouped, tense, extremely pruritic vesicles on erythematous bases. This grouping is reminiscent of that associated with infections by herpes simplex and varicella-zoster viruses—hence, the diagnostic terminology. As a result of pruritus, lesions are often excoriated, and sometimes it is difficult to demonstrate intact vesicles.55,56 Spruelike changes can be found when jejunal biopsies are performed, and there is a high frequency of the human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) B8, DR3, and Dqw2. Investigators believe that IgA antibodies, perhaps formed in the gut, bind to bundles of microfibrils in the papillary dermis, followed by complement deposition and recruitment of neutrophils.57,58

Dermatitis herpetiformis is a chronic, relapsing disease that can be well controlled, but not cured, by the drugs dapsone and sulfapyridine. A strict gluten-free diet can also be helpful, resulting in decreased dosages or even discontinuation of these agents. Malignancy has been reported in dermatitis herpetiformis, particularly enteropathy-associated non-Hodgkin lymphoma. However, recent studies appear to indicate only a slightly increased risk of malignancy in these patients, and in fact there may actually be a decrease in mortality.59,60 A gluten-free diet may serve a protective role.61

Microscopic Findings

The hallmark of the histopathology in dermatitis herpetiformis is the formation of papillary dermal neutrophilic microabscesses (Fig. 4-28). Cleftlike spaces develop over these microabscesses, which can coalesce to form clinically apparent vesicles.62 Eosinophils are sometimes visible and are said to be more prominent in older lesions. There is also an underlying perivascular dermal infiltrate that includes neutrophils, lymphocytes, and eosinophils in varying combinations. Leukocytoclasis is sometimes observed, and this may create an impression of vasculitis in some cases. Direct IF is of great help in diagnosis, because it shows granular to particulate IgA deposition along the dermal-epidermal junction, frequently concentrated at the tips of dermal papillae (Fig. 4-29).63 C3 complement and/or fibrin are often, but not invariably, found in the same vicinity. Indirect IF studies are negative, except that diagnostic antiendomysial IgA antibodies can be found with some substrates.

Differential Diagnosis

Dermatitis herpetiformis is the prototype disorder showing papillary neutrophilic microabscesses, sometimes including eosinophils. However, as mentioned previously, similar changes can be seen in a number of the immunobullous diseases, including bullous pemphigoid (and the variant disorders cicatricial pemphigoid and pemphigoid gestationis), epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, bullous LE, and linear IgA disease. Distinction among these disorders depends largely on direct IF studies. The only one of these disorders that might create confusion on IF study would be bullous LE with granular IgA deposition along the junctional zone. However, as mentioned previously, other immunoglobulins would also be present, of at least equal or greater intensity. Other conditions that feature neutrophils in the dermis can occasionally show accumulation of these cells in the dermal papillae and therefore resemble dermatitis herpetiformis to a degree. A common example is florid leukocytoclastic vasculitis. In that particular example, unequivocal vasculitis is identified, and direct IF study shows granular deposition of immunoglobulins and complement around vessels; the junctional zone is typically spared, with the possible exception of some granular C3 or fibrin deposition.

One caveat regarding dermatitis herpetiformis—routinely performed biopsy specimens may not always show diagnostic changes, but the classic direct IF findings can still be seen. In a recent example in the author’s laboratory, the clinician sent biopsy specimens to rule out dermatitis herpetiformis. Both the hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections and the IF sections showed only the morphologic features of verruca plana, and yet the direct IF findings were diagnostic for dermatitis herpetiformis.

Linear Immunoglobulin A Disease

This designation describes several different clinical disorders, including an eruption of childhood that features polycyclic lesions ringed by blisters that occur periorally and over the trunk (chronic recurrent bullous dermatosis of childhood),64 a widespread bullous eruption in adults,65 and the previously mentioned mucous membrane lesions that may comprise a subtype of cicatricial pemphigoid. The adult type has a strong association with certain drugs, including vancomycin (particularly common, in the author’s experience), captopril, furosemide, ibuprofen, lithium, naproxen, and trimethoprim.66 Although once considered a variant of dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA disease has different HLA types, and affected patients are usually only partly responsive to dapsone therapy. The involved target antigens vary considerably. They include 97-kD and 120-kD proteins, degradation products of the minor 180-kD bullous pemphigoid antigen,67 as well as a lamina densa protein that may be a component of type VII collagen.68

Microscopic Findings

The histopathology of linear IgA disease is similar to that of dermatitis herpetiformis in that papillary neutrophilic microabscesses are present. However, papillary neutrophils are sometimes continuous along the junctional zone, producing larger areas of separation than normally encountered in dermatitis herpetiformis (Fig. 4-30), and organization into discrete microabscesses may not be as well developed. Direct IF shows linear IgA deposition, with or without C3 deposition, along the dermal-epidermal junction (Fig. 4-31).69 Indirect IF occasionally shows linear IgA deposits.

Differential Diagnosis

Despite the previously stated microscopic resemblance to other immunobullous diseases, of which dermatitis herpetiformis is the prototype, the direct IF findings in linear IgA disease are quite striking and almost always diagnostic. However, in a minority of cases of linear IgA disease, linear deposition of other immunoglobulins is seen in addition to IgA. This can create confusion with examples of bullous LE, bullous pemphigoid, or cicatricial pemphigoid that include IgA among other immunoglobulins showing linear basement membrane zone deposits. Saline splitting may not provide additional help in this regard. Typically in linear IgA disease, IgA staining is stronger than for other immunoglobulins, whereas the reverse is the case in other immunobullous diseases. Nevertheless, correlation with other clinical and laboratory findings may be necessary.

Erythema Multiforme and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Erythema multiforme is a blistering disorder that can demonstrate varying degrees of severity. Although urticaria-like or papular lesions may occur, particularly in early stages, the hallmark is the iris, or target lesion that shows a central necrotic bulla. Numerous triggering factors are known, but among the best established are herpes simplex infection, a common cause of erythema multiforme in younger individuals, and certain medications, frequently encountered in older individuals. Recurrent bouts of erythema multiforme may occur in patients who develop recurrent herpesvirus infections, whereas drug-induced erythema multiforme in older individuals may last for longer periods of time, up to 3 to 4 weeks or more.70 Erythema multiforme is believed to represent a cell-mediated response to the various etiologic agents that can trigger the disease. The Stevens-Johnson variant, a more extensive form of erythema multiforme that is typically accompanied by prominent mucous membrane involvement, is often related to drug ingestion.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis, characterized by widespread erythema and exfoliation, is considered by some to represent a severe variant of erythema multiforme. It is also most often associated with drugs, particularly trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and other antibiotics, allopurinol, and anticonvulsants. Loss of fluid and electrolytes and infection are among the complications of this disorder.

Treatment of erythema multiforme includes removing the underlying cause (e.g., antiviral therapy or discontinuation of the offending medication) and symptomatic treatment. Management of toxic epidermal necrolysis involves intravenous immunoglobulin and replacement of fluid and electrolytes.

Microscopic Findings

Classic erythema multiforme consists of a triad of findings: vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer, apoptotic keratinocytes that can be found at all levels of the involved epidermis, and a relatively sparse superficial perivascular dermal infiltrate composed mainly of lymphocytes (Fig. 4-32).71 Papillary dermal edema may be the predominant feature when biopsies are obtained from the border of a lesion, whereas keratinocyte apoptosis (necrosis) may be the chief finding when specimens are obtained from the center of a necrotic blister. The epidermis is often of approximately normal thickness, and the stratum corneum may retain its normal basket-weave appearance, a reflection of the rapidity of lesional development. Blisters result from the extensive basilar vacuolar change with resulting cleft formation. The dermal infiltrate is often surprisingly mild. Although lymphocytes predominate, eosinophils are not infrequently found, and they can be numerous (>3/high-power field) in drug-induced cases.70 The epidermal changes are more severe in Stevens-Johnson syndrome (Fig. 4-33). Direct IF is often performed to rule out other blistering disorders—in particular, immunobullous diseases. The results are usually negative, although sometimes apoptotic (Civatte) bodies stain for IgM, and there may be granular C3 deposition in papillary dermal vessels or along the dermal-epidermal junction. Indirect IF studies are negative in this disease. Toxic epidermal necrolysis shows full-thickness epidermal necrosis (Fig. 4-34); however, early lesions may show extensive apoptosis. Dermal inflammation is notably sparse in many cases.

Figure 4-32 Erythema multiforme.

There is vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer leading to subepidermal separation, along with numerous apoptotic keratinocytes and a relatively modest perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate.

Differential Diagnosis

The constellation of features in erythema multiforme is quite characteristic, if not pathognomonic, and allows a diagnosis in most instances. Early papular or urticarial lesions may be the most problematic due to their nonspecific features. Most immunobullous diseases look quite different from erythema multiforme and can easily be excluded on a routine biopsy, with or without supplementation by direct IF. One possible exception is paraneoplastic pemphigus, which can closely mimic erythema multiforme microscopically, but shows different direct IF findings (intercellular and, sometimes, basement membrane zone fluorescence). Other differential diagnostic considerations included fixed drug eruption and pityriasis lichenoides acuta. Fixed drug eruption is limited to one or a few clinical locations and is exemplified by a discrete zone of recurrent erythema following ingestion of a particular agent. Biopsies show epidermal changes closely mimicking erythema multiforme, but there is a superficial and deep perivascular dermal infiltrate in fixed drug eruption, and neutrophils may be more evident. The author has seen rare examples of a spongiotic variant of fixed drug with prominent eosinophils and neutrophils, and this form would be readily distinguishable from erythema multiforme (see Chapter 12). Pityriasis lichenoides acuta can closely mimic erythema multiforme microscopically. However, usually there is a greater degree of parakeratosis and exocytosis of inflammatory cells in the former, and the dermal infiltrate may be more wedge-shaped and show evidence for lymphocytic vasculitis. Two other conditions that can resemble erythema multiforme microscopically but have substantially different clinical presentations are graft-versus-host disease and occasional examples of exfoliative dermatitis due to drugs, underlying neoplasm, or distant focus of infection.

An important clinical differential consideration for toxic epidermal necrolysis is staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, a primarily childhood disease due to the effects of exfoliative exotoxins types A and B. However, the latter disease typically has a much better prognosis and microscopically shows only superficial rather than full-thickness epidermal necrosis. This can be determined not only on routine biopsy specimens but also in a rapid procedure performed on frozen sections of separated skin.

Inherited Blistering Diseases

Clinical Features

Initially described by the Hailey brothers, this autosomal dominant disease is probably best designated by the eponym rather than its other name, familial benign chronic pemphigus. Hailey-Hailey disease features erythematous plaques with flaccid bullae that rupture and produce crusting and erosions. It commonly occurs in intertriginous areas. The chief finding, a loss of cohesion among epidermal keratinocytes, results from an abnormality of adherens junctions. The involved gene, ATP2CI, encodes a calcium pump (ATPase) that may be important in the maintenance of epidermal integrity.72 This is not an immune-mediated disease.

Treatment is largely supportive, including antibiotics for infection, dermabrasion, and grafting. However, clinicians have used a variety of other agents, such as photodynamic therapy and topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Microscopic Findings

On biopsy, lesions show extensive suprabasilar acantholysis involving epidermal keratinocytes, so much so that the resulting changes have been likened to a “dilapidated brick wall” (Fig. 4-35). At the base of a lesion, a single row of basilar keratinocytes lines the dermal papillae, producing structures called villi, and narrow strands of keratinocytes protrude into the underlying dermis. Follicular epithelia in the vicinity of lesions are spared (see Fig. 4-35). On occasion, some dyskeratosis can be identified, manifesting as cells with pyknotic nuclei surrounded by clear halos (corps ronds) or displaying elongated, pyknotic nuclei (grains) (Fig. 4-36).73 Dermal inflammation is variable and usually attracts little attention; the author has seen at least one case in which eosinophils were prominent. Direct and indirect IF studies are negative in this disease.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of Hailey-Hailey disease includes other acantholytic dermatoses. The most important of these is pemphigus. Although both disorders show suprabasilar acantholysis, the degree of acantholysis tends to be much greater in Hailey-Hailey disease, whereas in pemphigus, often only a few acantholytic cells are evident in the blister cavity. It is possible to observe dyskeratosis, at least focally, in Hailey-Hailey disease, and this is not a common feature of pemphigus. Eosinophilic spongiosis is not a feature of Hailey-Hailey disease, but on the other hand, eosinophils are often prominent in the dermal infiltrate of pemphigus lesions, and eosinophilic spongiosis may be identified in early lesions. Dermal eosinophils are not usually conspicuous but can be; the author has seen this on several occasions. One other major differentiating feature is follicular involvement. Although follicles are spared in Hailey-Hailey disease, they are typically involved in pemphigus and in fact may constitute a prominent feature in some examples of the latter disease. Direct IF study is often decisive, because positive intercellular IgG and C3 deposits are not evident in Hailey-Hailey disease but are seen in the epidermis in pemphigus.

Other acantholytic dermatoses must be ruled out. Darier disease (keratosis follicularis), another genodermatosis combining acantholysis with dyskeratosis, may show overlapping features with Hailey-Hailey disease, and for a time, the latter was considered a possible blistering variant of Darier disease. However, in most instances, Darier disease displays microscopic clefts rather than bullae, and dyskeratosis is much more prominent than in Hailey-Hailey disease (see later discussion). The same considerations would apply to other, acquired conditions showing focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, particularly Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). The latter tends to occur in middle-aged patients as scaly papules, particularly over the trunk. That scenario is often decisive. Microscopically, Grover disease can have at least five microscopic configurations associated with acantholysis: pemphigus-like, Hailey-Hailey–like, spongiotic, Darier-like, or pemphigus foliaceus–like. Obviously the greatest difficulty vis-à-vis this particular differential is created by the forms of Grover disease resembling pemphigus or Hailey-Hailey disease. However, the small, self-limited nature of the lesions would ordinarily allow a confident diagnosis. A further consideration is the entity acantholytic dermatosis of the genitocrural region (papular acantholytic dyskeratosis). These papular lesions often have histopathologic changes identical to those of Hailey-Hailey disease (Fig. 4-37), but they are localized and lack the familial history of the latter. As in Hailey-Hailey disease, direct IF studies are negative.

Bullous Darier Disease

The preceding discussion delineates the microscopic differences between Hailey-Hailey disease and Darier disease (see Chapter 16). However, rare examples of bullous Darier disease do occur.74,75 Occasionally, lesions of Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis—an acquired disorder featuring focal acantholytic dyskeratosis) may also form bullae. These appear to result from an exaggeration of the suprabasilar clefting that is a hallmark of the disease (Fig. 4-38). In one such case, other subtle findings—particularly nail changes—facilitated the diagnosis, even though in other respects the cutaneous findings were atypical. The marked degree of dyskeratosis, with well-formed corps ronds and grains, enables a correct diagnosis, and direct IF studies would be negative.

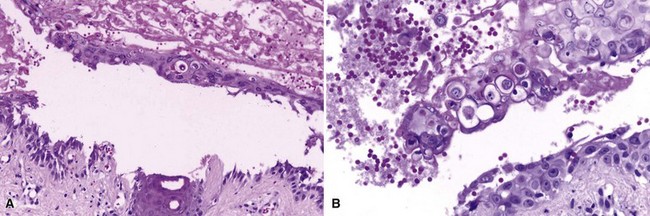

Figure 4-38 Bullous Darier disease.

A, Suprabasilar separation has occurred, in the vicinity of a follicular unit. This is basically an exaggeration of the less extensive clefting that usually develops in this disease. B, Detail of the blister roof, showing prominent dyskeratosis with corps rond formation.

Hereditary Epidermolysis Bullosa

The term epidermolysis bullosa refers to an extensive grouping of disorders that produce blistering either within the epidermis or at various levels of the basement membrane zone. Although numerous clinical varieties have been described, these disorders can generally be divided into intraepidermal, junctional, or dermolytic types.

The major intraepidermal types include the dominantly inherited epidermolysis bullosa simplex and Weber-Cockayne disease, also known as “recurrent bullous eruption of the hands and feet.” Epidermolysis bullosa simplex consists of vesicles and bullae that tend to occur with trauma to acral surfaces, especially the elbows, knees, lower legs, and feet. The condition usually begins shortly after birth. Fortunately, other complications are rare, and although troubling, this is considered one of the milder forms of epidermolysis bullosa. Weber-Cockayne disease manifests in the first several years of life but may not become apparent until adolescence, when it initially is often believed to be an exaggeration of normal friction blistering. Both of these disorders involve mutations of the keratin 5 and/or 14 genes.76,77

Junctional epidermolysis bullosa is an autosomal recessive disorder that includes a severe variant, often lethal in infancy, termed Herlitz disease,78 as well as several more benign forms with better prognosis.79 In Herlitz disease, there is extensive blistering and denudation of skin and mucous membranes that may be present at birth. Death may result from the complications of laryngeal or bronchial involvement, although survival past infancy has reportedly occurred. This form of the disease is associated with mutations of genes coding for polypeptide subunits of laminin 5: specifically, LAMA3, LAMB3, and LAMC2.80 Other rare forms include junctional epidermolysis bullosa with pyloric atresia, a severe form that may also be lethal at birth; cicatricial junctional epidermolysis bullosa, which produces syndactyly and joint contractures; generalized atrophic benign epidermolysis bullosa, in which patients can survive to adult life; and localized (pretibial) and inverse (truncal rather than acral involvement) atrophic forms. The genetic defects in these disorders, in some cases, have been shown to differ from those of Herlitz disease.

Dermolytic forms of epidermolysis bullosa result in varying degrees of scarring, because separation occurs in the sublamina densa zone.81 Those types with autosomal dominant inheritance are most often associated with blistering early in life, accompanied by scarring and milia formation. Hypertrophic scars develop in the Cockayne-Touraine variant, whereas pale to flesh-colored albopapuloid lesions are typical of the Pasini type. A rare pretibial variant first develops more typically in later childhood or early adult life. Type VII collagen, the important component of anchoring fibrils in the sublamina densa zone, is often abnormal in these dominant varieties of the disease, and this in turn is linked to abnormalities of the COL7A1 gene on chromosome 3.82 The major recessively inherited forms of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa include a localized type and two generalized variants: (1) the mild, or mitis, type and (2) the better known, severe, Hallopeau-Siemens type. In the latter, mucocutaneous blistering is present at birth, causing (as one of the most distinctive features) fusion of the digits and producing a mitten-like deformity of the hands and feet. Growth retardation, joint contractures, and anemia are present, and development of squamous cell carcinomas takes place in older patients in areas of repeated blistering and scarring. Again, these forms of the disease result from mutations in the COL7A1 gene that encodes type VII collagen, a component of anchoring fibrils in the sublamina densa zone of the basement membrane.

Microscopic Findings

In epidermolysis bullosa simplex, fully developed lesions have the appearance of an infiltrate-poor subepidermal bulla, but in reality the initial change involves degeneration of the infranuclear portions of basilar keratinocytes.83 Observation of this feature is best at the edge of a blister, or in subclinical lesions purposely created with a pencil eraser or other device; then, degeneration of basilar keratinocytes is evident, with the impression that the infranuclear portions of these cells are “pulling away” from the underling dermis (Fig. 4-39). In fully developed blisters, fragments of keratinocyte cytoplasm attached to the floor of what appears to be a “subepidermal” split are apparent. This produces a fringelike arrangement that can often be seen in routinely stained sections (Fig. 4-40) but may stand out with cytokeratin staining or on electron microscopy. In Weber-Cockayne disease, the area of separation appears to involve the mid or upper epidermis. Because purposely induced blisters in this variant of the disease form in the basilar layer, as is true in epidermolysis bullosa simplex, a “two hit” theory has been proposed to explain the usual microscopic appearance of separation in upper levels of the epidermis. Initial injury to germinative basilar keratinocytes (Fig. 4-41) is presumably followed by later injury to altered cells that, at the time of biopsy, have migrated to a more superficial epidermal location (Fig. 4-42).

Figure 4-39 Epidermolysis bullosa simplex.

This change was induced by a pencil eraser. Note the infranuclear degeneration of basilar keratinocytes with early separation from underlying tissues.

Figure 4-40 Epidermolysis bullosa simplex.

At low magnification, this lesion appeared to be a subepidermal blister. At higher magnification, it can be seen that the base is composed of basal keratinocyte cytoplasmic fragments attached to the dermal side of the split.

Figure 4-41 Epidermolysis bullosa simplex, Weber-Cockayne type.

Early changes include infranuclear degeneration with basilar vacuolization.

Figure 4-42 Epidermolysis bullosa simplex, Weber-Cockayne type.

A fully developed blister shows keratinocyte degeneration and separation occurring through the superficial portion of the viable epidermis.

In junctional types of epidermolysis bullosa, separation occurs through the lamina lucida of the basement membrane zone, giving the low-power appearance of an infiltrate-poor subepidermal bulla (Fig. 4-43). Immunostaining shows laminin and type IV collagen at the floor of the separation, distinguishing this group of disorders from the dystrophic forms of epidermolysis bullosa.84 On electron microscopy, absence or hypoplasia of hemidesmosomes can be demonstrated.85

Figure 4-43 Junctional epidermolysis bullosa.

This section shows a “clean” subepidermal separation, with no scarring and minimal inflammation. Ultrastructural examination shows hypoplasia or absence of hemidesmosomes.

All forms of dermolytic (dystrophic) epidermolysis bullosa show infiltrate-poor subepidermal blistering with varying degrees of scar formation. Milder scarring and milia formation are particularly seen in the dominant forms (Fig. 4-44), whereas scarring is more extensive in the recessive variants (Fig. 4-45). The albopapuloid lesions of the Pasini type of dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa show hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, and dermal fibrosis, some of which is perifollicular.86 The level of separation can be demonstrated with staining for laminin and type IV collagen, which exists in the roof of the blister in dystrophic variants. If available, staining for antibodies to type VII collagen is used, and weak or absent staining is apparent in the recessive dystrophic forms. Ultrastructural studies confirm the level of separation beneath the lamina densa in these disorders and show diminished (dominant forms) or absent (recessive forms) anchoring fibrils.85

Differential Diagnosis

For all types of epidermolysis bullosa, knowledge of the hereditary nature of the disease can be decisive in properly categorizing the disorder, and direct IF studies can further exclude those immunobullous diseases that are potential microscopic mimics. In epidermolysis bullosa simplex, fully developed blisters appear to be subepidermal, but as previously noted, careful inspection of the junctional zone lateral to the blister often shows degeneration of infranuclear portions of basilar keratinocytes. The history of childhood disease, usual absence of a significant inflammatory component, and negative routine direct IF studies help distinguish junctional forms of epidermolysis bullosa from immunobullous disorders such as bullous pemphigoid. The ultrastructural finding of hypoplastic hemidesmosomes substantiates the diagnosis. Microscopic examination in cases of dermolytic epidermolysis bullosa are often said to be of little value. However, with use of immunostains, including direct IF, this group of entities can often be diagnosed with reasonable certainty, at least to the point where they can be distinguished from infiltrate-poor immunobullous disorders such as epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and some examples of pemphigoid. A distinction from epidermolysis bullosa simplex and junctional epidermolysis bullosa is also possible, although electron microscopy is most useful in this regard. Specialized antibody studies are available at some institutions to allow more precise categorization among the subtypes of epidermolysis bullosa.

Selected Pustular Disorders

Pustular Dermatoses of Infancy

Clinical Features

The development of pustules in infancy is characteristic of three conditions. Erythema toxicum neonatorum, which occurs during the first few days of life, consists of patchy erythema involving the face, trunk, and proximal extremities. Papules and pustules that appear to be follicular-based are also evident. This self-limited dermatosis typically disappears within a week or so. Dermatologists are often not consulted about this common disorder, and biopsies are rarely obtained. Acropustulosis of infancy, in which pruritic vesicopustules develop over the extremities,87 typically begins in the first few months of life and may persist or recur over a period of several years. Lesions can mimic those of scabies, and a relationship to that disorder or to atopy has been described. Transient neonatal pustular melanosis, a similar condition, is somewhat more widespread in distribution. It is characterized by vesicopustules that rupture to leave hyperpigmented macules, often with scaly edges. These lesions resolve after a few days, although the associated pigmentation fades more gradually.88

Microscopic Findings

On biopsy, erythema toxicum neonatorum shows eosinophils within the outer root sheath and infundibulum of hair follicles as well as scattered within the superficial dermis (Fig. 4-46A). In fully formed lesions, eosinophils accumulate in a subcorneal location adjacent to follicular ostia (see Fig. 4-46B).89 In acropustulosis of infancy, there is formation of intraepidermal pustules that eventually reach a subcorneal location (Fig. 4-47). Neutrophils tend to predominate, but eosinophils may occur.90 The findings in transient neonatal pustular melanosis are similar to those in acropustulosis of infancy, although the pigmented macules display basilar hypermelanosis.91

Differential Diagnosis

Erythema toxicum neonatorum can resemble other dermatoses characterized by eosinophilic microabscess formation in the epidermis. The most significant problem would arise in distinguishing this disorder from the early “bullous” phase of the X-linked dominant disorder incontinentia pigmenti, which also arises early in life. However, erythema toxicum neonatorum is more transient, and its chief clinical finding, in contrast to the linear vesicles of incontinentia pigmenti, is actually macular erythema. The papules and pustules of erythema toxicum neonatorum are clearly folliculocentric, unlike in incontinentia pigmenti, in which eosinophilic spongiosis and intraepidermal microabscess formation are most prominent. Acropustulosis of infancy and transient neonatal pustular melanosis may be difficult to distinguish from one another, particularly when the former disease occurs in individuals with dark complexions, and clinical information would then be required. Two other conditions that could mimic these two disorders microscopically are bullous/pustular impetigo and subcorneal pustular dermatosis (including the subcorneal pustular dermatosis variant of IgA pemphigus). The first of these may be difficult to distinguish in the absence of clinical information, but the latter is a primarily a condition of adults (a few children have been reported with the disease). Direct IF would be useful in the unlikely event that IgA pemphigus were a serious clinical consideration.

Subcorneal Pustular Dermatosis

Sneddon and Wilkinson first described this chronic, relapsing condition in 1956.92 It occurs mainly in middle age and particularly in women, although some children reportedly have the disorder. Pustules, some forming annular configurations, develop, especially over the trunk and in intertriginous areas. It is a problematic dermatosis in that some cases, including those with IgA monoclonal gammopathy, have proven to be IgA pemphigus,93 and others show a distinct overlap with generalized pustular psoriasis.94,95 It remains to be seen if subcorneal pustular dermatosis persists as a defined clinicopathologic entity, but it is still important in terms of differential diagnosis.

Sulfapyridine and dapsone are mainstays of treatment. However, various other therapies have been used.

Microscopic Findings

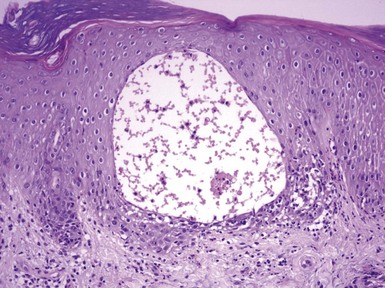

The disease name well describes the essential histopathologic change: the formation of subcorneal pustules with minimal acantholysis and, at least classically, the absence of spongiform pustulation (Fig. 4-48).96 A mixed superficial dermal infiltrate often includes neutrophils. Direct IF is negative; those examples with intercellular IgA deposition are now classified as the subcorneal pustular dermatosis variant of IgA pemphigus.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of subcorneal pustular dermatosis includes the full spectrum of pustular diseases, most of which can be ruled out on clinical grounds. Although bullous impetigo can appear virtually identical, normally it would not have as florid a clinical presentation and could be distinguished by culture studies. Pemphigus foliaceus tends not to produce such discrete pustules, and acantholysis is much more evident. IgA pemphigus can have identical histopathologic findings but is recognized by direct IF due to the intercellular deposition of IgA within the epidermis. Pustular psoriasis is a major consideration, and some cases originally reported as subcorneal pustular dermatosis eventually proved to be examples of pustular psoriasis. However, pustular psoriasis is typified by spongiform pustulation, in which neutrophils are found within spongiotic spaces in the superficial spinous layer; this should not be the case in subcorneal pustular dermatosis, and in the author’s view such a finding would be prima facie evidence for pustular psoriasis or a small group of related conditions (candidiasis, geographic tongue, Reiter syndrome). Drug-related cases mimicking subcorneal pustular dermatosis may actually represent acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. However, in contrast to subcorneal pustular dermatosis, that condition features intraepidermal pustules with slight spongiform pustulation, apoptotic keratinocytes, eosinophils, and sometimes leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

Traumatic Blisters

Various forms of superficial injury to the skin can produce bullae, and these have characteristic microscopic changes. In purest form, they are all infiltrate-poor, although inflammation can be seen in long-standing, infected, or additionally traumatized lesions. Friction blisters show a cleavage plane high in the epidermis, just beneath the granular cell layer. These are difficult or impossible to distinguish from the lesions of Weber-Cockayne disease. Suction blisters are located subepidermally. Thermal burns and cryotherapy both produce subepidermal bullae (Fig. 4-49). Similarly, electrical injury produces subepidermal separation. In the realm of dermatopathology, this is most frequently encountered in electrodesiccation injury or when cutting current is used in the excision of large specimens. These blisters show vertical “stretching” of the overlying degenerated basilar keratinocytes and an intensely eosinophilic to basophilic, amorphous appearance of superficial dermal collagen bundles. Coma blisters are found at pressure sites and believed to result from pressure, ischemia, and local tissue hypoxia. They are associated with ingestion of certain drugs, especially barbiturates, but are also seen in conjunction with certain infections or metabolic abnormalities. Microscopic findings include subepidermal blisters with both epidermal and sweat gland necrosis (Fig. 4-50) and minimal inflammation. Re-epithelialization can be seen in later stages (see Fig. 4-50A). Subepidermal separation also commonly occurs overlying dermal scars. This is usually an incidental finding and not associated with the clinical appearance of a blister; it probably results from trauma related to tissue handling, particularly when involving scars with a recently re-epithelialized surface.

References

1. Iwatsuki, K, Takigawa, M, Imaizumi, S, et al. In vivo binding site of pemphigus vulgaris antibodies and their fate during acantholysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:578–582.

2. Culton, DA, Qian, Y, Li, N, et al. Advances in pemphigus and its endemic pemphigus foliaceus (fogo selvagem) phenotype: a paradigm of human autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 2008;31:311–324.

3. Kowalczyk, AP, Anderson, JE, Borgwardt, JE, et al. Pemphigus sera recognize conformationally sensitive epitopes in the amino-terminal region of desmoglein-1. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;105:147–152.

4. Miura, T, Kawakami, Y, Oyama, N, et al. A case of pemphigus herpetiformis with absence of antibodies to desmogleins 1 and 3. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:101–103.