EVERY PRESIDENT NEEDS SUPPORT IN CONGRESS to pass his legislative proposals. Barack Obama began his presidency with what appeared to be a highly favorable strategic position in Congress. Democrats held 257 seats in the House, and after the resolution of the protracted recount in Minnesota, 60 seats in the Senate (including the two Independents who caucused with the Democrats). Recapturing the presidency in the historic election of 2008 was exhilarating for Democrats, and it is reasonable to infer that most of them felt they had a stake in their leader’s success.

We saw in chapter 1 that it is natural for a new president, basking in the glow of an electoral victory, to focus on creating, rather than exploiting, opportunities for change. It may seem quite reasonable for a president who has just won the biggest prize in American politics by convincing voters and party leaders to support his candidacy to conclude that he should be able to convince members of Congress to support his policies. Thus, Obama lost no time to begin, as he put it in his inaugural address, “the work of remaking America.”

As with leading the public, then, presidents may not focus on evaluating existing possibilities when they think they can create their own. Yet, assuming party support in Congress or success in reaching across the aisle to obtain bipartisan support is fraught with dangers. Not a single systematic study exists that demonstrates that presidents can reliably move members of Congress, especially members of the opposition party, to support them.

The best evidence is that presidential persuasion is at the margins of congressional decision making. Even presidents who appeared to dominate Congress were actually facilitators rather than directors of change. They understood their own limitations and quite explicitly took advantage of opportunities in their environments. Working at the margins, they successfully guided legislation through Congress. When these resources diminished, they reverted to the more typical stalemate that usually characterizes presidential-congressional relations.1

In his important work on pivotal politics, Keith Krehbiel examined votes to override presidential vetoes, focusing on those members of Congress who switched their votes from their original votes on the bill. He found that presidents attracted 10 percent of those who originally supported a bill but lost 11 percent of those who originally supported him by opposing the bill. Those closest in ideology to the president were most likely to switch to his side, which may indicate they voted their true views, rather than responding to other interests, when it really counted. Even among those most likely to agree with the White House, legislators within the cluster of pivotal or near-pivotal, the net swing was only 1 in 8. The majority of switchers were from the president’s party, indicating that the desire to avoid a party embarrassment rather than presidential persuasiveness may have motivated their votes.2

It is certainly possible that there is selection bias in votes on veto overrides. Presidents do not veto the same number of bills, and some veto no bills at all. Moreover, presidents may often choose to veto bills on which they are likely to prevail. In addition, most override votes are not close, allowing members of Congress more flexibility in their voting. Whatever the case, Krehbiel’s data do not provide a basis for inferring successful presidential persuasion.

There are several components of the opportunity for obtaining congressional support. First is the presence or absence of the perception of a mandate for change. Do members of Congress think the public has spoken clearly in favor of the president’s proposals? The second component is the presence or absence of unified government. Is the president’s party in control of the congressional agenda? A third aspect of the opportunity structure is the ideological division of members of Congress. Are they likely to agree with the president’s initiatives? Are the parties unified or are there critical cross-pressures that threaten the president’s support?

This chapter analyzes the prospects for support for the president’s program in Congress. First, I examine the question of the perception of a mandate in the 2008 election. Next, I briefly discuss the impact of his party’s majority control of Congress. Finally, and most importantly, I address the degree of ideological polarization in Congress and homogeneity or heterogeneity of each of the parties and its probable impact on the president’s congressional support. By analyzing the opportunity for obtaining congressional support for Obama’s initiatives, it is possible to understand and predict the challenges he faced in convincing members of Congress to support his proposals and the relative utility of this strategy for governing.

First, however, we need to consider the nature of the president’s agenda. The more ambitious the agenda, the more likely it will meet with intense criticism and political pushback. A White House strategy built on the assumption of persuading members of Congress to support the president’s programs can lead to an overly ambitious agenda that lacks the fundamental support it needs to weather the inevitable attacks from the opposition.

In an article written days after the 2008 presidential election, Paul Light maintained that there was not room in government for the kind of breakthrough ideas that Obama had promised. Every Democratic president since Lyndon Johnson had sent fewer major proposals to Congress, just as every Republican president since Richard Nixon had done as well. Thus, Light suggested that instead of presenting a massive agenda to Congress, the new president should start with a few tightly focused progressive initiatives that would whet the appetite for more. His best opportunity for a grand agenda was more likely to be in 2013 than in 2009.3

We saw in chapter 1 that Obama had a different view. He proposed an agenda that confronted the era’s most intractable problems, from a tattered financial system that helped fuel a deep recession to health care, education, and energy policies that had long defied meaningful reform. He persuaded Congress to spend more than three quarters of a trillion dollars to try to jump-start the economy. On his own authority he altered federal rules in areas ranging from stem cell research to the treatment of terrorism suspects. He launched efforts to help strapped homeowners refinance their mortgages, sweep “toxic assets” off bank balance sheets, and shore up consumer credit markets. He also set a timetable for ending the occupation of Iraq, increased the U.S. presence in Afghanistan, and set about improving the American image in the world.

The president often declared that he did not have the luxury of addressing the financial crisis and issues such as health care, education, or the environment one at a time. “I’m not choosing to address these additional challenges just because I feel like it or because I’m a glutton for punishment,” he told the Business Roundtable. “I’m doing so because they’re fundamental to our economic growth and ensuring that we don’t have more crises like this in the future.”4 He wanted a more sustained approach than patching the economy until the next bubble, like the technology bubble of the 1990s and the housing bubble of the 2000s.5

In Obama’s view, it was impossible to deal with the economic crisis without fixing the banking system, because one cannot generate a recovery without liquid markets and access to capital. He insisted that the only way to build a strong economy that would truly last was to address underlying problems in American society like unaffordable health care, dependence on foreign oil, and underperforming schools. Reducing dependence on foreign oil required addressing climate change, which in turn required international cooperation and engaging the world with vigorous U.S. diplomacy. His appointment of five prominent White House “czars” with jurisdictions ranging across several departments reflected this syncretic outlook.

Moreover, the president had little patience for waiting to act. “There are those who say these plans are too ambitious, that we should be trying to do less, not more,” he told a town hall meeting in Costa Mesa, California on March 18, 2009. “Well, I say our challenges are too large to ignore.” The next day in Los Angeles he proclaimed, “It would be nice if I could just pick and choose what problems to face, when to face them. So I could say, well, no, I don’t want to deal with the war in Afghanistan right now; I’d prefer not having to deal with climate change right now. And if you could just hold on, even though you don’t have health care, just please wait, because I’ve got other things to do.” Later, on The Tonight Show With Jay Leno, he repeated his standard response to critics who charged he was trying to do too much: “Listen, here’s what I say. I say our challenges are too big to ignore.”6

There was also an element of strategic pragmatism in the president’s view. For example, Obama felt that health care was a once-in-a-lifetime struggle and a fight that could not wait. To have postponed it until 2010 would have meant trying to pass the bill in an election year. To have waited until 2011 would have risked taking on the battle with reduced majorities in the House and Senate.7 Even when the administration began running into resistance to its health care plan in the summer of 2009, and Rahm Emanuel, Vice President Biden, David Axelrod, and others went to Obama and pushed for a pared-back approach that would focus on expanding coverage for lower-income children and families and on reforming the most objectionable practices of insurance companies, Obama persisted in his comprehensive approach.8

Obama and his top strategists, including Axelrod and Emanuel, repeatedly defended the administration’s sweeping agenda by arguing that success breeds success, that each legislative victory would make the next one easier.9 In other words, the White House believed success on one issue on the agenda would create further opportunities on additional policies. Victories would beget victories.

There were some efforts to set priorities, of course. The White House and congressional Democrats deferred fights over tax policy, despite the impending expiration of many of the George W. Bush tax cuts. The White House also opposed a high-profile commission to investigate Bush administration interrogation practices and declined to engage in hot-button debates over gays in the military (until 2010) or gun control.10 The administration also did not make immigration and union card check legislation priorities.11

An electoral mandate—the perception that the voters strongly support the president’s character and policies—can be a powerful symbol in American politics. It can accord added legitimacy and credibility to the newly elected president’s proposals. That is why Obama declared that if he did not talk about health care reform during the 2008 campaign, he could not pass it in his first year in office.12

Concerns for representation and political survival encourage members of Congress to support the president if they feel the people have spoken.13 And members of Congress are susceptible to such beliefs. According to David Mayhew, “Nothing is more important in Capitol Hill politics than the shared conviction that election returns have proven a point.”14 Members of Congress also need to believe that voters have not merely rejected the losers in elections but positively selected the victors and what they stand for.

More important, mandates change the premises of decisions. Following Franklin D. Roosevelt’s decisive win in the 1932 election, the essential question became how government should act to fight the Depression rather than whether it should act. Similarly, following Lyndon Johnson’s overwhelming win in the 1964 election, the dominant question in Congress was not whether to pass new social programs but how many social programs to pass and how much to increase spending. In 1981, the tables were turned; Ronald Reagan’s victory placed a stigma on big government and exalted the unregulated marketplace and large defense efforts. Reagan had won a major victory even before the first congressional vote.

The winners in presidential elections usually claim to have been accorded a mandate,15 but winning an election does not necessarily, or even usually, provide presidents with one. Every election produces a winner, but mandates are much less common. Even presidents who win elections by large margins often find that perceptions of support for their proposals do not accompany their victories. In the presidential elections held between 1952 and 2008, most of the impressive electoral victories (Richard Nixon’s 61 percent in 1972, Ronald Reagan’s 59 percent in 1984, and Dwight Eisenhower’s 57 percent in 1956) did not elicit perceptions of mandates (Lyndon Johnson’s 61 percent in 1964 is the exception).16

Candidates often appeal as broadly as possible in the interest of building a broad electoral coalition. Incumbents frequently avoid specifics on their second-term plans and attempt to increase their vote totals by asking voters to make retrospective judgments. Candidates who do not make their policy plans salient in the campaign undermine their ability effectively to claim policy mandates. Moreover, voters frequently also send mixed signals by electing majorities in Congress from the other party.

When asked about his mandate in 1960, John F. Kennedy reportedly replied, “Mandate, schmandate. The mandate is that I am here and you’re not.”17 Bill Clinton could associate himself with popular initiatives in 1995–1996 to aid his reelection, but could not use this show of voter support as an indicator of public approval of initiatives he did not discuss in the campaign, especially since the public also elected a Republican Congress during his second term. In 2004, George W. Bush won with less than 51 percent of the vote, lacked substantial coattails, and did not emphasize specific policy proposals in his campaign. Thus, his claims of a mandate lacked credibility—as he soon discovered when the public and Congress were unresponsive to his proposals for reforming Social Security.

Certain conditions promote the perception of a mandate.18 The first is a large margin of victory. Obama’s 52.9 percent of the vote hardly qualifies as a landslide. Similarly, a surprisingly large victory accompanying a change in the party in the White House may have a powerful psychological impact, as it did in Ronald Reagan’s victory over Jimmy Carter in 1980. Obama was the projected winner for weeks before Election Day, however, and he won by the margin that polls had predicted. The president can also benefit from hyperbole in media analyses of election results that exaggerate the one-sidedness of his victory. Although the press celebrated the election of an African American, it did not exaggerate the size of Obama’s vote.

The impression of long coattails can also add to the perception of a mandate, and it is possible that some Democrats would view themselves as having benefitted from the president’s coattails and thus give him the benefit of the doubt on tough votes. Ironically, more than half of the Democrats’ net gain of 21 House seats in 2008 came in districts that Obama lost: 12 freshman Democrats won previously Republican-held seats in districts that John McCain carried. Overall, all but 35 of the 257 House Democrats won a higher percentage of the vote in their districts than Obama did. Furthermore, only 12 of the 33 first-term Democrats in the House ran behind the president. Six of the 12 won 52 percent or less of the vote in taking Republican-held seats and thus were likely to be heavily cross-pressured. Democrats who were able to establish their own political identity might not feel compelled always to vote hand-in-hand with the new administration, freeing them to vote independently if they saw some daylight between their constituents and the Obama administration.19

Most winning Democratic senatorial candidates ran ahead of Obama. Only in Colorado, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Oregon, and New Jersey did he run ahead of winning Democrats. Moreover, only in the first four of these was the winner’s margin close enough that Obama’s coattails could have made a difference in the outcome.

A campaign oriented around a major change in public policy coupled with the consistency of the new president’s program with the prevailing tides of opinion in both the country and his party, and a sense that the public’s views have shifted, may enhance the perception of a mandate. We have seen in chapter 1, however, that the public’s views did not shift in 2008 and that Obama’s program did not seem to be consistent with the prevailing tides of opinion in the country.

In sum, Obama won a clear victory but not one that encouraged perceptions of a mandate. Moreover, there was little he could do to influence these perceptions. To succeed in Congress, he would have to rely on other resources.

Attaining agenda status for a bill is a necessary prelude to its passage, and thus obtaining agenda space for his most important proposals is at the core of every president’s legislative strategy. The burdens of leadership are considerably less at the agenda stage than at the floor stage, where the president must try to influence decisions regarding the political and substantive merits of a policy. At the agenda stage, in contrast, the president only has to convince members that his proposals are important enough to warrant attention. The White House generally succeeds in obtaining congressional attention to its legislative proposals,20 and the Obama presidency was no exception.

Controlling the agenda also means setting the terms on which a chamber considers a proposal. In the House, the timing of a floor vote and the sequence, number, and substance of amendments on legislation are under the control of the majority party leadership. It was reasonable to expect the Democratic leadership to use this power to ease the path for the president’s agenda.21

In the Senate, where power is more decentralized, we should expect that the president would face far greater difficulty in influencing the agenda. Moreover, Republicans were practiced at using the filibuster to prevent issues from coming to a vote. In addition, influence over the agenda offers the majority much less influence over the outcome of votes than it does in the House.

Despite David Mayhew’s innovative study, which found that the likelihood of passing major laws was as great under divided government as when the White House enjoyed unified control,22 other research has found that divided government reduces legislative productivity.23 Party majorities and agenda control also largely free the president from having to deal with the opposition’s legislation. The president does not need to invest his time, energy, and political capital in fighting veto battles, and he is much less likely to face the embarrassing situation in which he must veto popular legislation that he opposes.24

Unified government is not a panacea, however. Divided government is primarily a constraint on the passage of legislation the administration opposes, the congressional initiatives of the opposition party. The most significant proposals of presidents are no more likely to pass under unified government than under divided government.25 There are other, powerful influences on congressional support for the president’s programs. Among the most important of these are the partisan polarization and ideological diversity within Congress.

A primary obstacle to passing major changes in public policy is the challenge of obtaining support from the opposition party.26 Such support can be critical in overcoming a Senate filibuster or effectively appealing to Independents in the public, who find bipartisanship reassuring. The Washington Post reported that the Obama legislative agenda was built around what some termed an “advancing tide” theory.

Democrats would start with bills that targeted relatively narrow problems, such as expanding health care for low-income children, reforming Pentagon contracting practices and curbing abuses by credit-card companies. Republicans would see the victories stack up and would want to take credit alongside a popular president. As momentum built, larger bipartisan coalitions would form to tackle more ambitious initiatives.27

Just how realistic was the prospect of obtaining Republican support?

Perhaps the most important fact about Congress in 2009 was that partisan polarization had been at an historic high. Important work on voting patterns in Congress has found that the 110th Congress had the highest level of party polarization since the end of Reconstruction.28 Similarly, Congressional Quarterly found that George W. Bush presided over the most polarized period at the Capitol since it began quantifying partisanship in the House and Senate in 1953. There had been a high percentage of party unity votes—those that pitted a majority of Republicans against a majority of Democrats—and an increasing propensity of individual lawmakers to vote with their fellow partisans.29

There was no reason to expect partisan polarization to diminish in the Obama administration. Republican constituencies send stalwart Republicans to Congress, whose job it is to oppose a Democratic president. Most of these senators and representatives were unlikely to be responsive to core Obama supporters. They knew their constituencies, and they knew Obama was unlikely to have much support in them. Thus, few of the Republicans’ electoral constituencies showed any enthusiasm for health care reform. As Gary Jacobson has shown, the partisan divisions that emerged in Congress on the health care issue were firmly rooted in district opinion and electoral politics.30 Moreover, conservative Republicans were the group of political identifiers least likely to support compromising “to get things done.”31

On the day before the House voted on the final version of the economic stimulus bill, the president took Aaron Schock, a freshman Republican member of Congress, aboard Air Force One to visit Illinois. Before an audience in Schock’s district, Obama praised him as “a very talented young man” and expressed “great confidence in him to do the right thing for the people of Peoria.” But when the representative stood on the House floor less than twenty-four hours later, his view of the right thing for the people of Peoria was to vote against the president. “They know that this bill is not stimulus,” Schock said of his constituents. “They know that this bill will not do anything to create long-term, sustained economic growth.”32 Schock was typical of Republicans in early 2009, who viewed the stimulus debate as an opportunity to rededicate their divided, demoralized party around the ideas of big tax cuts and limited government spending.

In the 111th Congress (2009–2010), nearly half of the Republicans in both the House and Senate were elected from the eleven states of the Confederacy, plus Kentucky and Oklahoma. In each chamber, Southerners made up a larger share of the Republican caucus than ever before. At the same time, Republicans held a smaller share of non-Southern seats in the House and Senate than at any other point in its history except during the early days of the New Deal.33 The party’s increasing identification with staunch Southern economic and social conservatism made it much more difficult for Obama to reach across the aisle. Southern House Republicans, for instance, overwhelmingly opposed him, even on the handful of issues where he has made inroads among GOP legislators from other regions. Nearly one-third of House Republicans from outside of the South supported expanding the State Children’s Health Insurance Program, but only one-tenth of Southern House Republicans did so. Likewise, just 5 percent of Southern House Republicans supported the bill expanding the national service program, compared with 22 percent of Republicans from other states.

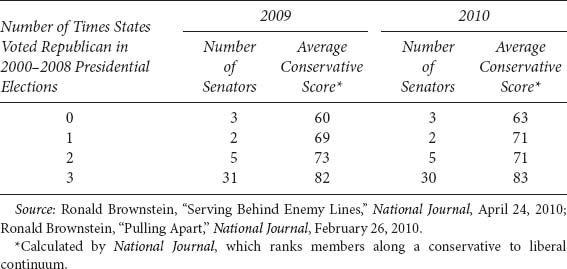

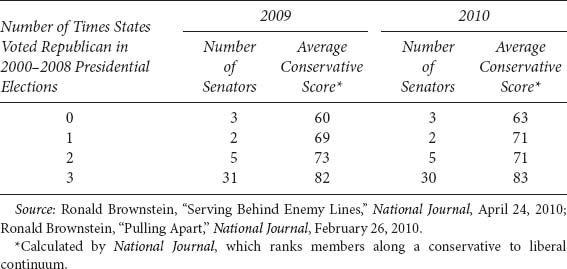

The Republican Party’s losses in swing areas since 2006 accelerated its homogenization. Few Republicans represented Democratic-leaning districts. As a result, far fewer congressional Republicans than Democrats had to worry about moderate public opinion. Fully thirty-one of the forty Republican senators serving in 2009 (thirty-one of forty-one in 2010), for example, were elected from the eighteen states that twice backed Bush and also voted for McCain. Five other senators represented states that voted for Bush twice and then supported Obama. Just six Republican senators were elected by states that voted Democratic in at least two of the past three presidential elections. One of these lawmakers, Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania, switched parties to become a Democrat.

Table 4.1 shows the impact of these constituency cross-pressures on voting of Republican senators in 2009 and 2010. Most Republican senators represented reliably Republican states, and these senators voted in a considerably more conservative direction than their party colleagues from states that were more likely to support Democratic presidential candidates. At the time of the vote to repeal “don’t ask, don’t tell,” there were eleven Republican senators from states President Obama had won in 2008. Of these, seven voted for repeal, three voted against, and one did not vote. On the other hand, only one of the thirty-one senators from states John McCain carried in 2008 voted for repeal.34

In addition, Republican members of Congress faced strong pressure to oppose proposals of the other party. Senators Max Baucus and Charles Grassley, the leaders of the Senate Finance Committee’s negotiations over health care reform, both confronted whispers that they might lose their leadership positions if they conceded too much to the other side. Iowa conservatives even threatened that Grassley could face a 2010 primary challenge if he backed Baucus. Obama had Grassley to the White House half a dozen times to talk about health care reform. Just before August 2009 summer recess, the president asked him, “If we give you everything you want—and agree to no public plan—can you guarantee you would support the bill?” “I can’t guarantee I would,” Grassley replied.35 Before he switched to the Democratic Party, Arlen Specter reported that Republican Senate leader Mitch McConnell put heavy pressure on Republicans like himself, Olympia Snowe, Susan Collins, George Voinovich, Lisa Murkowski, and Mel Martinez not to cooperate with the White House.36

In a similar vein, the executive committee of the Charleston County, South Carolina, Republican Party censored Republican Senator Lindsey Graham because “U.S. Sen. Lindsey Graham in the name of bipartisanship continues to weaken the Republican brand and tarnish the ideals of freedom, rule of law, and fiscal conservatism.”37 Two months later the Lexington County Republican Party Executive Committee censored him for his stands on a range of policies, which it charged “debased” Republican beliefs.38 When asked in 2010 if he would be as bipartisan if he were facing reelection that November, Graham replied, “The answer’s probably no.” Similarly, he understood that John McCain had to win his primary for renomination in Arizona and thus could not take bipartisan stances.39

TABLE 4.1.

Senate Republican Conservatism by Partisanship of State, 2009–2010

In January 2010, 55 percent of Republicans and Republican leaners wanted Republican leaders in Congress, who were following a consistently conservative path, to move in a more conservative direction.40 In perhaps the most extreme expression of this orientation, four months later the Utah Republican Party denied longtime conservative Senator Robert Bennett its nomination for reelection. The previous month, Republican Governor Charlie Crist had to leave his party and run for the Senate as an Independent in Florida because he was unlikely to win the Republican nomination against conservative Marco Rubio. In September, Senator Lisa Murkowski lost her renomination in Alaska to a largely unknown candidate on the far right of the political spectrum. The previous year, Republican Senator Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania switched parties, believing there was little chance he could win a Republican primary against conservative Pat Toomey.

Similarly, House Republicans with any moderate leanings were more concerned about the pressures from their right than about potential fallout from opposing a popular president. The conservative Republican Study Committee—which included more than 100 of the 178 House Republicans—called for enforcing party unity on big issues and hinted at retribution against defectors. Conservatives also raised the prospect of primary challenges,41 as they did in the 2009 race to fill the seat in New York State’s 23rd congressional district. Led by Sarah Palin and Dick Armey, conservatives forced the Republican candidate to withdraw from the race shortly before Election Day.

Compounding the pressure has been the development of partisan communications networks—led by liberal blogs and conservative talk radio—that relentlessly incite each party’s base against the other. These constant fusillades help explain why presidents now face lopsided disapproval from the opposition party’s voters more quickly than ever—a trend that discourages that party’s legislators from working with the White House.

These centrifugal forces affect most the Republican Party. The Right has more leverage to discipline legislators because, as we have seen, conservative voters constitute a larger share of the GOP coalition than do liberals of the Democratic Party. The Right’s partisan communications network is also more ferocious than the Left’s.

Given the broad influences of ideology and constituency, it is not surprising that Frances Lee has shown that presidential leadership itself demarcates and deepens cleavages in Congress. The differences between the parties and the cohesion within them on floor votes are typically greater when the president takes a stand on issues. When the president adopts a position, members of his party have a stake in his success, while opposition party members have a stake in the president losing. Moreover, both parties take cues from the president that help define their policy views, especially when the lines of party cleavage are not clearly at stake or already well established.42 This dynamic of presidential leadership was likely to complicate further Obama’s efforts to win Republican support.

According to Republican Representative Michael Castle of Delaware, the gulf between the parties had grown so wide that most Republicans simply refused to vote for any Democratic legislation. “We are just into a mode where there is a lot of Republican resistance to voting for anything the Democrats are for or the White House is for.”43

It was unlikely, then, that Obama would receive much support from Republicans. But what about the Democrats? Even before taking office, Obama endured a baptism by friendly fire. The expanded and emboldened congressional Democrats greeted his tax proposals with disdain, dragged him into a political squabble over his Senate successor, and chafed at key appointments to his administration. Obama called for bold action on a stimulus plan to rescue the sagging economy and saw his party’s leaders respond by pushing the deadline for the package from Inauguration Day to mid-February.

Democrats described two forces as contributing to the less-than-full embrace of Obama out of the gates: a weariness of being taken for granted for eight years by the outgoing Bush administration, and a sense that the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program was rushed through in the fall of 2008 in two weeks, a de facto abdication of Congress’s responsibility. House Majority Leader Steny H. Hoyer dismissed a reporter’s suggestion that Democrats would go easy on oversight of the administration, holding up a copy of the congressional newspaper The Hill with its headline quoting Senate Majority Leader Harry M. Reid’s declaration that “I Don’t Work for Obama.”44

The new administration also faced a potential problem in trying to steer congressional leaders and committee chairs who might be reluctant to surrender too much of the power they regained from Republicans in 2006. “Many members of Congress have been there many years, and there are some people who just two years ago got back the gavel, who now have to cede some of their authority to the incoming administration,” said Howard Paster, President Bill Clinton’s first director of legislative affairs. “They are going to be supportive, but they are also not going to cede all of their authority. Human nature doesn’t allow for that.”45

Nevertheless, Democrats wanted the president to succeed and knew that their success was directly related to his. To succeed, however, the president would have to hold his party cohort together. Did Democrats represent a coherent coalition that would naturally support the president’s initiatives? Did Democrats come from constituencies that were solidly behind Obama? To answer these questions, we need to explore the cross-pressures between party and constituency that have plagued Democratic coalitions since the New Deal as well as the diversity of ideological positions in the Democratic cohort.

As each party’s electoral coalition has grown more ideologically homogeneous since the 1960s, the country has witnessed an increase in straight party voting. The increasing sophistication of redistricting software, which has allowed state legislatures to draw districts that reliably lean toward one party, has reinforced the trend of House and presidential candidates of the same party winning a district. In 2004, there were only fifty-nine split districts, the lowest number in the post–World War II era. Bush carried forty-one Democratic House districts and John Kerry won in eighteen Republican ones.

The 2008 election represented an exception to the trend, however. The number of split districts increased to eighty-three. Forty-eight House Democrats represented districts that preferred Republican presidential nominee John McCain to Obama in 2008. Most of these districts were in Southern and Border states or culturally conservative rural areas where Obama struggled. Twenty-three of these Democrats were serving their first or second terms in the 111th Congress. Nine won with less than 55 percent of the vote in 2008, and another ten obtained less than 60 percent.

In sum, the Democratic House majority depended entirely upon members whose constituents voted for John McCain. We should expect these cross-pressured members to find it more difficult to support liberal policies than other members of the caucus.

These members faced serious cross pressures when it came to voting on the president’s most important initiatives. The opposition party views members representing split districts as tempting targets, especially when they are held by members who have yet to establish themselves or when the most recent presidential results seem to confirm longer-term changes in the district’s demography and partisanship.

If we step back a bit further, we find even more Democrats would be cross-pressured. One-third (84) of the 257 Democratic House members elected in 2008 represented districts won by President Bush in 2004 or John McCain in 2008. Forty-eight of those Democrats—eight more than the size of their party’ majority—were from districts that voted for both Bush in 2004 and McCain in 2008. That group composed nearly one-fifth of the Democratic House contingent. Thus, many of the gains of Democrats in 2006 and 2008 came from Republican-leaning districts.

By way of contrast, Obama won thirty-four districts that elected a Republican to the House. Only six of these representatives were not at least in their third term, however. It is true that nine of the remaining twenty-eight Republicans were reelected in 2008 with less than 55 percent of the vote, and another ten won reelection with less than 60 percent. One might think that legislators from such closely contested terrain would instinctively prefer compromise to confrontation and that such an orientation would benefit the new president. Yet we have seen that powerful forces pushed them toward confrontation rather than cooperation and thus offered little potential for Obama to obtain their support.

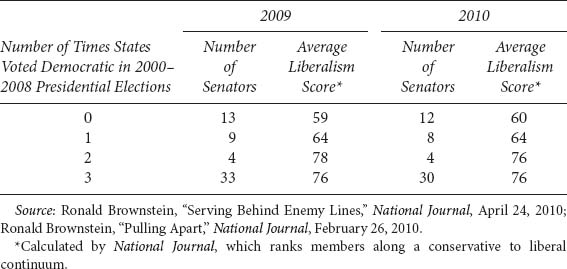

The Senate was no more favorable for the president. Although eight Republican senators represented states Obama won, twelve Democrats represented McCain states. Twenty-two of the sixty Democratic senators (37 percent) in 2009 represented states that had voted Republican in at least two of the previous three presidential elections. Table 4.2 shows the impact of these cross-pressures. Democrats from states that were more likely to support Republican presidential candidates were considerably less liberal than their Democratic colleagues from more reliably Democratic states. Moreover, a substantial number of Democratic senators represented Republican states.

There were constituency pressures in addition to partisanship, of course. Regarding climate change legislation, for example, ten moderate Senate Democrats from states dependent on coal and manufacturing sent a letter to President Obama in August saying they would not support any climate change bill that did not protect American industries from competition from countries that did not impose similar restraints on climate-altering gases. Without their support, it was unlikely that the Senate could pass a major climate change bill.46

TABLE 4.2.

Senate Democratic Liberalism by Partisanship of State, 2009–2010

Ultimately, forty-four House Democrats opposed the bill. Many of them represented districts that relied heavily on coal for electricity and manufacturing for jobs. The president understood. “I think those forty-four Democrats are sensitive to the immediate political climate of uncertainty around this issue,” Obama said. “They’ve got to run every two years, and I completely understand that.”47

The Helping Families Save Their Homes Act lost its centerpiece: a change in bankruptcy law the president had once championed that would have given judges the power to lower the amount owed on a home loan. Twelve Democratic Senators joined thirty-nine Republicans to vote against the provision. Some Democrats, like Tim Johnson of South Dakota and Thomas R. Carper of Delaware, represented states that are the corporate home to major banks.48

Constituency pressures are always important to members of Congress, but so are their policy views. Much of the growth of the Democratic contingents in the House and the Senate in the 2006 and 2008 elections was the result of success in areas characterized by ideological moderation. It is not surprising that such constituencies elected moderates to Congress. Coalescing these members with the large liberal core of the Democratic caucuses was likely to present a challenge to achieving party unity.

THE MODERATES A substantial segment of Democrats were moderate on economic and fiscal matters. There were a number of centrist, pro-business Democratic groups, including the New Democrat Coalition (with sixty-nine members), the Democratic Leadership Council, the NDN (founded as the New Democrat Network), and the Third Way. Most visible were the fifty-four members of the House’s Blue Dog Coalition of fiscally conservative Democrats.

Ideological differences represented more than fiscal or economic matters. The challenges presented by the diversity of views within the Democratic caucus were especially clear regarding the amendment to the health care reform bill offered by Representative Bart Stupak of Michigan. The amendment would prevent women who received federal insurance subsidies from buying abortion coverage (critics asserted it would make it difficult for women who bought their own insurance to obtain coverage). Stupak had the leverage to win a counterintuitive victory that forced a Democratic-controlled Congress to pass a measure that was hailed as an anti-abortion triumph. For his efforts, the New York Times reported, he endured more hatred than perhaps any other member of Congress, much of it from fellow Democrats.49

The National Journal’s vote ratings for the 2009 session of Congress succinctly illustrate the diversity and the results of cross-pressures within the Democratic caucus. The seventy-seven House Democrats in the Progressive Coalition had an average liberalism score of 83 percent, while the average for the fifty-four Democrats in the Blue Dog Coalition was 53 percent. (The average for all House Democrats was 70 percent.)50

There were similar problems with the Senate. Charlie Cook calculated that the 111th Congress had twenty-three to twenty-six relatively centrist senators (mostly Democrats) and about forty-one true-blue liberals.51 Therefore, even if fairly liberal legislation passed the House, which also had a substantial number of moderate Democrats, the odds were good that it would face difficulties in the Senate.

For example, a significant split developed between the two Democratic senators leading efforts to remake the nation’s health care system. They disagreed over the contours of a public health insurance plan, the most explosive issue in the debate. Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts made it clear that he favored a robust public health care plan, a government-sponsored entity that would compete with private insurers. By contrast, Senator Max Baucus of Montana, chair of the Finance Committee, worked for months with the panel’s senior Republican, Charles E. Grassley of Iowa, in the hope of forging a bipartisan bill which would not include the option of a public plan.52

Organized labor was a key element in Obama’s electoral coalition, and it placed a high priority on the passage of the so-called card-check provision that would have required employers to recognize a union as soon as a majority of workers signed cards saying they wanted a union. Nevertheless, in an example of the power of moderate Democrats to constrain their party’s more liberal legislative efforts, Democrats had to drop the provision.53

Often both ideological and constituency pressures overlapped. For example, thirty-three members of the Blue Dog Coalition represented districts won by McCain. It is not surprising that such members would be concerned about the midterm elections after domestic spending, the annual deficit, and the national debt all jumped by record amounts. Thus, the potential for clashes on major issues with a largely liberal Democratic majority was substantial. Moreover, it was just such members who became the targets of Republicans and their interest-group allies in major legislative battles.54

It is perhaps in recognition of the challenge of governing with his own party that the president planned to use the new Organizing for America network in part to pressure lawmakers—particularly wavering Democrats—to help him pass complex legislation on the economy, health care, and energy.55

Similarly, a group of liberal bloggers announced in February 2009 that it was teaming up with organized labor and MoveOn.org to form a political action committee, Accountability Now, that would seek to push the Democratic Party farther to the left. The bloggers said they were planning to recruit liberal candidates for challenges against more centrist Democrats currently in Congress. Their intention was to enable Obama to seek more liberal policies without fear of losing support from the more conservative members of his party serving in Congress. (They did not rule out occasional friction with Obama, as well.) The Service Employees International Union and Daily Kos also supported this effort.56 The PAC’s first candidate for the 2010 election was Arkansas Lt. Governor Bill Halter, who would challenge Democrat Blanche Lincoln for her Senate seat.

When the White House encountered resistance from moderate Democrats in the Senate on its budget, Americans United for Change, a group financed largely by organized labor, organized an ad campaign with the permission of Democratic strategists close to the White House. The new television advertisements urged centrist Democrats, many of whom had a streak of fiscal conservatism that made them leery of the increases proposed by the president, to support the budget. The spots were broadcast in eleven states and urged senators to support the administration’s budget priorities as well. At the same time, Obama’s former campaign team urged supporters to call their members of Congress.57

THE LIBERALS Governing from the left would be a challenge. Governing from the middle would be no picnic, either. One of Obama’s biggest challenges was dealing with the left of his own party. Two weeks before his inauguration and just hours after he publicly called for speedy passage of a stimulus package to prevent the economic crisis from lasting for years, the president-elect’s economic recovery plan ran into crossfire from congressional Democrats. They complained that major components of his plan were not bold enough and urged more focus on creating jobs and rebuilding the nation’s energy infrastructure rather than cutting taxes. Further complicating the picture, Democratic senators said they would try to attach legislation to the package that would allow bankruptcy courts to modify home loans, a move Republicans opposed. While conservatives criticized the heavy spending, and moderate Democrats expressed concern about the swelling deficit, liberals pushed for even more money to be devoted to social programs, alternative-energy development, and road, bridge, and school construction.58

When Justice David Souter announced his resignation, President Obama’s aides invited liberal activists to the White House to discuss his upcoming Supreme Court selection. They told the activists not to lobby for their favorites in the news media or talk down candidates they opposed.59

The president touched off a controversy with the left when he reversed his decision to release photographs showing prisoners being abused while in U.S. custody, arguing that public disclosure would threaten the safety of U.S. military personnel abroad and could inflame the rest of the world as he was trying to win new respect for the United States. This action was followed by the decision to resume, with some modifications, the military tribunals used by the Bush administration since the attacks of September 11, 2001. Although administration officials insisted that prisoners would be given more rights than they had under Bush, human rights and civil liberties groups condemned the decision.

The war in Afghanistan was likely to prove an especially difficult sell among Democrats. As we have seen, as early as March 2009, only 49 percent of Democrats in the public approved of Obama’s decision to send 17,000 more troops to Afghanistan.60 By October 2009, only 36 percent of Democrats supported sending even more troops in response to General Stanley McChrystal’s request for 40,000 additional soldiers. Indeed, 50 percent of Democrats wanted to begin withdrawing troops.61

In a year-end briefing on the legislative session, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi made it clear that the president would have to argue his own case to House Democrats as he sought support for a planned surge of 30,000 troops into Afghanistan. She added that she was finished asking her colleagues to back wars that they did not support. “The president’s going to have to make his case,” Pelosi told reporters. In June, she had urged her colleagues to support a more than $100 billion supplemental funding bill for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, arguing that they needed to give the new president time to come up with a plan. But she also promised never to ask them to vote for war spending again.62

As Obama’s and the Democrats’ approval ratings fell and the president attempted to reposition himself to appeal to the middle of the electorate, some on the left excoriated him. When word leaked that in his first State of the Union message, he would propose freezing a portion of the domestic budget for three years, Rachel Maddow of MSNBC likened the plan to “stupid Hooverism.” Many liberals remained angry that the president had not pushed harder for the “public option” on health care.

Perhaps the biggest collision with the left occurred over the extension of the Bush-era tax cuts during the lame-duck session of the 111th Congress. Many prominent liberals attacked the president for abandoning his principles in agreeing to extend the tax cuts for the wealthy and to a high threshold for the estate tax. House Democrats passed a resolution opposing the compromise plan the White House worked out with Republican leaders. The Progressive Change Campaign Committee, a liberal group that had repeatedly attacked Obama on the left, aired two television commercials demanding that the president not agree to any compromise with the GOP that would extend tax cuts for household incomes above $250,000 a year. At the same time, Moveon.Org released its own new ad that included a video montage from Americans all over the country urging the president not to compromise.63 Sam Graham-Felsen, who described himself as Obama’s chief blogger during the 2008 campaign, wrote an op-ed in the Washington Post complaining that the president had not activated his grassroots supporters in major legislative battles and needed to do so on taxes.64

This opposition frustrated the president. In an unscheduled visit to the White House briefing room, Obama displayed uncharacteristic emotion when he suggested that liberals were unrealistic about what they could achieve in Washington.

This is the public option debate all over again. So I pass a signature piece of legislation, where we finally get health care for all Americans, something that Democrats have been fighting for for a hundred years, but because there was a provision in there that they didn’t get, that would have affected maybe a couple of million people, even though we got health insurance for 30 million people and the potential for lower premiums for 100 million people, that somehow that was a sign of weakness and compromise.65

In addition, liberals should not keep complaining every time they do not get everything they want:

Now, if that’s the standard by which we are measuring success or core principles, then, let’s face it, we will never get anything done. People will have the satisfaction of having a purist position and no victories for the American people. And we will be able to feel good about ourselves and sanctimonious about how pure our intentions are and how tough we are, and in the meantime, the American people are still seeing themselves not able to get health insurance because of a preexisting condition, or not being able to pay their bills because their unemployment insurance ran out.66

Despite large Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress, Barack Obama was unlikely to find it easy to pass the most significant components of his legislative program. To begin, he did not enjoy a widespread perception that his election signaled a mandate for substantial changes in public policy. His margin of victory was not especially large and his coattails were short. Moreover, the public had not shifted its views in a more liberal direction. Unified government was certainly an advantage in influencing the congressional agenda, but it did not guarantee presidential dominance of the legislature.

The White House anticipated that it could attract bipartisan support from Republicans. The foundations of this expectation were weak, however. Partisan polarization was at an historic high, and the Republican Party’s locus in the economic and social conservatism of the South reinforced the disinclination of Republicans to offer support across the aisle. Indeed, the more homogeneous conservative ideology of Republican activists and the Right’s strident and ever-expanding communications network meant that Obama would face a vigorous partisan opposition with strong incentives not to cooperate with the White House.

Democrats were more ideologically diverse than Republicans, posing yet another challenge for Obama. Many Democratic members of Congress represented Republican-leaning districts, and many were more moderate than the president. Democratic majorities in both chambers of Congress depended entirely upon members whose constituents voted for John McCain.

These cross-pressured and ideologically divergent members were much less likely to support Obama’s initiatives than the rest of the Democratic caucus. At the same time, liberals were likely to be frustrated at efforts to placate their more moderate colleagues.

The analysis of Barack Obama’s opportunities for obtaining congressional support leads us to predict that obtaining the legislature’s backing for his most significant initiatives would pose challenges. It seems especially clear that he would attract few Republican votes for these policies and, thus, that bipartisanship would not be a successful strategy for governing. Instead, he would have to rely on party leadership. In chapter 5, I examine the president’s leadership of Congress, and in chapter 6, I test the prediction by examining the congressional support the president actually received.