BARACK OBAMA CAME TO OFFICE with an ambitious agenda for policy change. Most of these changes required congressional approval. To obtain congressional support, he employed a variety of strategies for governing. One strategy centered on creating opportunities for change by taking his case to the public in an effort to leverage public support to win backing in Congress. We saw in chapter 3 that this effort did not succeed. The president found it difficult to move the public.

A second approach to creating opportunities for change is reaching across the congressional aisle and convincing the opposition party to lend support to the president’s initiatives. After analyzing the opportunities for success in this endeavor in the Obama administration in chapter 4, I predicted there was little prospect of obtaining bipartisan support for the president’s core initiatives. Nevertheless, we saw in chapter 5 that the White House made substantial efforts to win Republican votes.

Yet a third strategy for governing focuses on exploiting opportunities for change by managing and maintaining a supportive majority coalition of those predisposed to support the president. Barack Obama enjoyed comfortable majorities in both the House and the Senate as a result of the 2008 elections. I have predicted that if the president were to succeed, he would have to rely almost entirely on the support of his party.

In this chapter, I focus on the major policy initiatives during 2009–2010 to determine whether the president was able to create opportunities for change by convincing Republicans to provide bipartisan support for these proposals. I also examine the success of exploiting the support of the president’s party, emphasizing both the White House’s dependence on Democrats and the challenge of maintaining party unity.

The president made concerted efforts to reach across the aisle and create opportunities for policy change. He wanted Republican votes both to pass legislation and to provide him political cover for controversial stands. Claiming bipartisan support, he felt, would lend legitimacy to the historic policy changes he was proposing. As we have seen, he and his top aides spent many hours meeting with Republicans in large groups and consulting with individual Republicans, especially senators, like Olympia Snowe, Susan Collins, and Charles Grassley. Despite consistent rebuffs, Obama kept trying.

From the beginning, Republicans offered stiff resistance to the president’s overtures. When he went to Capitol Hill to meet with House Republicans on the stimulus bill shortly after his inauguration, Republican Party leaders told him even before negotiations began that their party would vote against the bill in a bloc. On health care reform, when the White House went a long way to meeting a Republican senator’s wishes on health care reform, Obama asked the senator if he could now support the bill. The senator replied, “Unless I can get ten other Republicans to stand with me [an impossible task], I can’t do it.”1 As the president’s tenure unfolded, the divisions on Capitol Hill grew deeper, the rhetoric more hostile, and the cooperation across the aisle less frequent and meaningful. The day after the president upbraided Congress in his 2010 State of the Union address for excessive partisanship, Senate Republicans voted en masse against a plan to require that new spending not add to the deficit.

How successful were Obama’s efforts at bipartisanship? How much Republican support did he obtain for his major initiatives? The discussion in chapter 4 leads us to predict that partisan predispositions would be difficult to change and that the president would obtain few Republican votes for his major initiatives. That is exactly what happened.

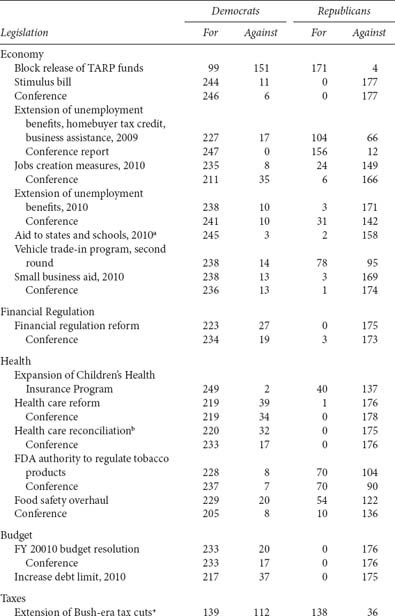

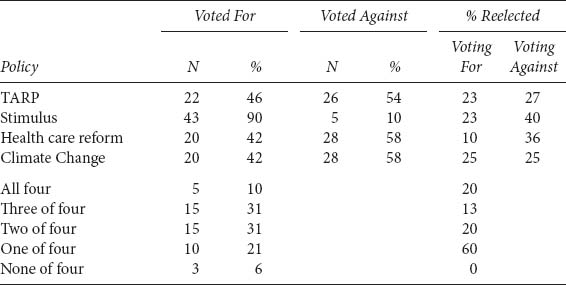

During the transition, President Bush accommodated a request from Obama and formally asked for the release of the remaining half of the TARP funds. Congress had the potential to pass a law blocking the increase, and a number of congressional leaders threatened to do just that, complaining that the Obama administration was not explicit enough about what it was going to do with the money. Obama made a personal trip to Capitol Hill, lobbying for release of the funds and providing more details about how the money would be spent. Nevertheless, all but four House Republicans voted to block release of the funds (table 6.1).

House Republicans were uniform in their opposition to the economic stimulus bill, the new president’s highest priority. Minority Leader John Boehner told his caucus in a meeting before the president arrived that he was going to oppose the House package and that they should too. Similarly, the next day’s debate contrasted with the president’s conciliatory gestures. In the end, all but eleven Democrats voted for the plan, but not a single Republican supported it. Even after negotiations with the Senate that pared down the cost of the bill, no House Republicans voted for its final passage.

TABLE 6.1.

House Votes on Major Bills by Party, 111th Congress

Supported by the likes of Rush Limbaugh (who declared that he hoped Obama’s presidency failed) and Sean Hannity (who denounced the stimulus bill on Fox News as the European Socialist Act of 2009), Republicans found their voice in adamant opposition, just as they did with Bill Clinton in 1993 and 1994. Even in the glow of a presidential honeymoon, in the context of Obama’s outreach efforts, and in the face of a national economic crisis, they chose to employ harsh language and loaded terms such as “socialism” to describe his policies. Rediscovering the shortcomings of budget deficits and pork barrel spending, Republicans ran radio advertisements in the districts of thirty Democrats, accusing them of “wasteful Washington spending.”

The lack of bipartisan support on the stimulus bill took Obama by surprise. The White House was also naïve about the brazenness of the opposition. By early 2010, ninety-three Republican members of Congress had cut ribbons or put out press releases in their districts, taking credit for stimulus spending they had voted against.2

The president’s next major battle was over the budget resolution for fiscal year 2010. It did not garner a single Republican vote in either chamber. The legislation to authorize the necessary increase in the debt limit received a similar level of Republican support.

In June 2009, the House passed the landmark American Clean Energy and Security Act, designed to curb U.S. greenhouse-gas emissions. It attracted the support of only eight Republican representatives. Reform of regulations for financial institutions, mortgage loan modification, job creation and small business aid in 2010, an overhaul of student loans, campaign finance (requiring greater disclosure of the role of corporations and other special interest groups in paying for campaign advertising), and civil rights issues regarding wages, hate crimes, and homosexuality in the military also received little or no Republican support. Nor did the DREAM Act proposal to allow illegal immigrants brought to the United States as children to gain legal resident status if they joined the military or went to college.

When the House voted on the health care reform bill on November 7, 2009, it received only one Republican vote. The sole supporter was Representative Anh Cao of Louisiana, a freshman from a New Orleans-based district that went 75 percent for Obama. His victory resulted from two unique factors. First, his opponent, incumbent Representative William J. Jefferson, was under indictment on federal corruption charges. Second, Hurricane Gustav pushed the congressional election in that district into December, when Democratic turnout was much lower than during the presidential election the previous month. Even Anh did not vote for the critical conference report the following March, and no Republicans supported the reconciliation bill on health care.

A few consensual issues brought bipartisan agreement. Protections for credit card holders (especially when it included an unrelated gun rights provision) were popular with the public. Congress was spurred into action by public outcry over such practices as sudden increases in interest rates even for those who paid their bills, hard-to-understand contract terms, and hidden fees. Not a single member of Congress voted against reforming procurement practices in the Department of Defense in committee or on the floor. A bill extending unemployment benefits, continuing a popular homebuyer tax credit, and expanding a tax credit for businesses in 2009 was also popular during an economic downturn, as was the Helping Families Save Their Homes Act.

A few other bills attracted considerable Republican support, including funding the popular “cash for clunkers” program (45 percent of voting Republicans),3 expanding national service programs (41 percent), giving the FDA authority to regulate tobacco products (40 percent), and overhauling food safety law (31 percent). Expansion of the Children’s Health Insurance Program won the support of 23 percent of the Republican representatives. Designating certain public lands as wilderness areas received Republican support in its initial passage, but only 22 percent of Republicans voted for the conference report after controversy arose over gun rights in national parks. All of these bills passed early in the administration and none of them were at the heart of the administration’s legislative program. When the House cleared food safety legislation by agreeing to Senate amendments on December 21, 2010, only ten Republicans voted for the bill.

There were two issues that produced an unusual form of bipartisanship. One was in the area of foreign policy. Over the course of Obama’s tenure, House Democrats became increasingly critical of the war in Afghanistan. Democratic opposition emerged early. The president defended his strategy for Afghanistan in a late-April 2009 meeting with the Congressional Progressive Caucus, a group of more than seventy liberal members. However, on May 14, 2009, when it came time to act on the president’s request for more than $96 billion to fund the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq through the remainder of the fiscal year, fifty-one House Democrats opposed it.4 The next month, with the inclusion of funds for the International Monetary Fund, the bill passed the House again, with thirty Democrats opposing it. We saw in chapter 4 that at the end of 2009, Speaker Nancy Pelosi vowed never again to ask her troops to vote for war spending.5

On March 10, 2010, the House of Representatives held a three-hour debate on a proposal to withdraw American troops by the end of the year. Although the House voted overwhelmingly to reject the withdrawal proposal, sixty Democrats joined with five Republicans in support of pulling out. By July 2010, 148 House Democrats and 160 Republicans backed an appropriations measure to fund the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, but 102 Democrats joined 12 Republicans in opposing the bill. Among those voting against the bill was Representative David Obey, the Democratic chair of the Appropriations Committee, the panel responsible for the measure.6

A similar pattern of bipartisanship support occurred on the extension of the Bush-era tax cuts. Although the president was able to forge a compromise with Republicans that included an extension of unemployment insurance and a re-imposition of a tax on some estates, many Democrats were outraged at continuing tax cuts for the wealthy and exempting even substantial estates from inheritance taxes. As a result, many voted against the president. Republicans, on the other hand, were generally pleased to support the tax cuts and most supported the bill.

There was one foreign policy issue on which consensus developed against the president. On January 22, 2009, Obama issued an executive order to close the prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, within a year. Immediately after the president acted, Republicans began warning against moving detainees to prisons on U.S. soil. To thwart the White House’s plan, House Minority Leader John Boehner introduced the “Keep Terrorists Out of America Act.” Lawmakers began tightening the purse strings against any attempt by the president to implement unilaterally a new policy, adding language to several appropriations bills that placed restrictions on moving the prisoners and on shutting down the detention center. Democrats held the line against preventing the administration from bringing prisoners to the United States for trial, but they did accede to a forty-five-day advance notification period and risk assessment for such actions.

In 2010, Congress imposed strict new limits on transferring detainees out of the Guantánamo Bay prison, banning the transfer into the United States of any Guantánamo detainee in fiscal year 2011—even for the purpose of prosecution, prohibiting the purchase or construction of any facility inside the United States for housing detainees being held at Guantánamo, and forbidding the transfer of any detainee to another country unless Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates signed off on the safety of doing so.

The pattern is clear. House Republicans overwhelmingly opposed the most significant legislation the president proposed in the 111th Congress. Whether the issue was the economy, regulating the financial industry, health care reform, the budget, civil rights, immigration, campaign finance reform, student loans, climate change, or mortgage loan modifications, Republicans uniformly opposed Democratic initiatives. Despite the president’s efforts to reach across the aisle, he could not obtain bipartisan support for his major proposals. Even a modest bill on child nutrition championed by Michelle Obama garnered only seventeen Republican votes.

Of course, even a few Republicans could make a difference between winning and losing. On only two bills listed in table 6.1 did Republican support make a difference in the outcome, however. The eight Republican representatives who voted for the climate change mitigation bill made the difference in it passing, because forty-four Democrats voted against it. Whether the president could have won this much Republican support on a conference report if the Senate had also passed a version of the bill is an open question.

The opposition of many Democrats to the extension of the Bush-era tax cuts during the lame-duck session of Congress in 2010 necessitated obtaining Republican support for passage of the bill. Because Republicans were eager to continue the existing tax rates, this support was forthcoming.

Because of their large majorities, Democrats could generally prevail in the House in the face of uniform Republican opposition. The Senate was a different story, however. Given that the number of Democrats was sixty in 2009 and fifty-nine in 2010, and given the need to obtain sixty votes for closure on most measures, there was a premium on obtaining some Republican support as well as on maintaining Democratic unity. In the context of extreme partisan polarization, the president also wanted a patina of bipartisanship for his proposals.

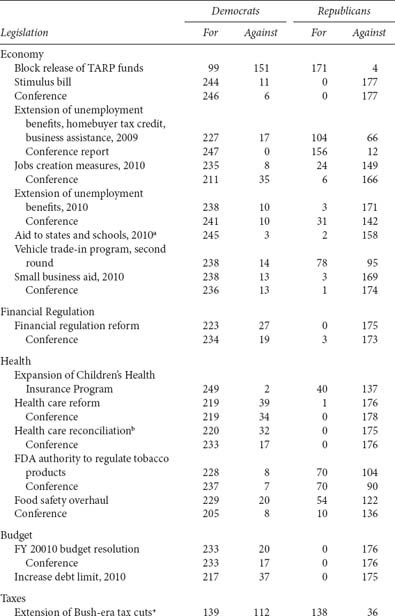

The Senate approved the release of the TARP funds by a 52-42 margin, but only six Republicans voted for Obama’s request (table 6.2). That, however, was a high point of support for the president’s major initiatives. Despite his compromises, the president did little better with Republicans in the Senate than in the House on the stimulus bill. Only three GOP senators supported each version of the stimulus bill: Olympia Snowe and Susan Collins of Maine and Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania—the three most moderate Republican senators. (Soon after, Specter switched parties and became a Democrat.) Adding insult to injury, Republican Senator Judd Gregg of New Hampshire withdrew as nominee as secretary of Commerce, citing “irresolvable conflicts” with the president over his economic stimulus plan. “We are functioning,” he added, “from a different set of views on many critical items of policy.”7

Obama’s efforts to negotiate with Charles Grassley, Olympia Snowe, and Susan Collins on health care reform came to naught. Indeed, Democrats were startled by the speed of the Republican’s rejection of health care proposals they had supported in previous years.8 No Republican senators supported health care reform or the follow-up reconciliation bill.

Similarly, no Republican senator voted for the FY 2010 budget resolution or the authorization for increasing the national debt. None voted for mortgage loan modification, and only two supported aid to states and schools and the conference agreement on the extension of unemployment benefits in 2010. Five or fewer Republican senators supported financial regulation reform, hate crimes expansion, protection against wage discrimination, small business aid in 2010, and the confirmation of Elena Kagan as a Supreme Court justice. Only seven Republican senators voted for the second round of the cash for clunkers program, and only nine supported expansion of the Children’s Health Insurance Program and the confirmation of Sonia Sotomayor as a Supreme Court justice. Eight Republicans voted to repeal “don’t ask, don’t tell,” while fourteen supported jobs creation measures in 2009 (eleven in conference).

TABLE 6.2.

Senate Votes on Major Bills by Party, 111th Congress

Not only did the Republicans overwhelmingly oppose Democratic, and especially White House, initiatives when they came to a vote, but they also did their best to prevent final votes altogether. Their frequent resort to the filibuster succeeded in preventing action on climate change, immigration, and campaign finance.

As in the House, there were a few policies that were widely popular and achieved bipartisan agreement. Protections for credit card holders (with its unrelated gun rights provision), the Helping Families Save Their Homes Act, reforming procurement practices in the Department of Defense, and a catch-all bill extending unemployment benefits, a homebuyer tax credit, and business assistance were consensual issues. Granting the FDA authority to regulate tobacco products won 59 percent of voting Republican senators, expanding national service programs won 53 percent of that group, 50 percent of Republicans voted for designating certain public lands as wilderness areas, and 38 percent supported overhauling food safety regulation. A third of Republicans voted to ratify the New START treaty.

The president’s compromise proposal to extend the Bush-era tax cuts irritated a number of Democratic senators, just as it did Democratic members of the House. A third of these senators voted against the president, but Republicans overwhelmingly supported the bill, as tax cuts remained a top priority for them.

Also similar to the House, there was consensus against the president on the question of the disposition of detainees held at Guantánamo Bay. At one point, the Senate voted 90-6 in favor of an amendment prohibiting funding for transferring, releasing, or incarcerating detainees at Guantánamo Bay to or within the United States. The Senate also joined the house in imposing strict restrictions on the president’s movement of prisoners in fiscal year 2011.

Republican support was not crucial to the enactment of most of the president’s program. There are only two bills in table 6.2 on which Republican support made the difference in the outcome. The first is the effort to block release of the TARP funds, which six Republicans opposed and occurred before Obama took office. The other bill is the compromise plan to extend the Bush-era tax cuts passed near the end of the lame-duck Congress in 2010. In addition, the president required Republican support to reach the two-thirds margin for ratifying the New START treaty and for breaking filibusters on issues such as the repeal of “don’t ask, don’t tell.”

Rather than surmounting partisanship, Barack Obama was engulfed in it. Congressional Quarterly found extraordinarily high levels of party line voting, even in the first weeks of the Obama administration. An average of 50 percent of the roll call votes during the Bush years were party unity votes. In 2009, 51 percent of the votes in the House united the parties against each other. The big increase in partisanship was in the Senate, however. The average percentage of party unity votes in the upper chamber during the Bush presidency was 57 percent, including 60 percent in 2007 and 52 percent in 2008. In 2009, 72 percent of the roll call votes in the Senate were party unity votes, the highest percentage ever recorded. Party voting in the Senate was even higher in 2010, with 79 percent of the votes showing majorities of each party opposing each other. The figure for the House declined to 40 percent as it focused on less controversial issues while waiting for the Senate to act on the major issues.9

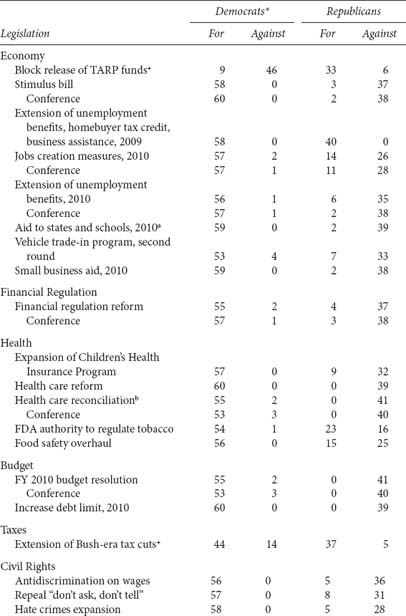

TABLE 6.3.

Presidential Support on Nonunanimous Votes

Underlying the partisan conflict were the clear ideological differences between the parties. Indeed, the distance between the parties in both houses of Congress in 2009 and 2010 was the greatest since the end of Reconstruction.10 Studies employing different methodologies found that there was no ideological overlap at all among Democrats and Republicans in the 111th Congress.11 With a liberal Speaker and a supporting cast of liberal committee chairs running the legislative process in the House, legislation on issues such as the economy, health care, climate change, financial regulation, and civil rights was bound to favor the liberal worldview. Even the most moderate Republicans would have trouble with such policies. The need to obtain a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate gave Republicans more leverage for negotiating more moderate policies, but the number of Republicans interested in compromise was quite small. Thus, there was little potential for the president to obtain support from the opposition.

Table 6.3 shows the support of party groups in each chamber for votes on which Congressional Quarterly determined the White House had expressed a clear position. On these votes, the typical Republican representative supported the president only 16 percent of the time, while Republican senators supported the president on average just 25 percent of the time in 2009. In 2010, Republican members of the House supported the president on average 19 percent of the time, while Republican senators did so 12 percent of the time.

The power of a presidential phone call to Republicans, even moderate Republicans, had severe limits. For example, very early in his tenure Obama called Senator Richard Lugar of Indiana twice to appeal for support for the stimulus bill. One of the calls came just after the president returned from visiting a town in Indiana with one of the highest unemployment rates in the state. Nevertheless, Lugar told the president he was going to vote no.12 Tellingly, Republican obstructionism was Obama’s greatest surprise of his first year in office.

[It wasn’t that] I thought that my political outreach and charm would immediately end partisan politics. I just thought that there would be enough of a sense of urgency that at least for the first year there would be an interest in governing. And you just didn’t see that.13

A strategy of bipartisanship not only failed to win Republican converts, but it also proved to be a costly effort. It blurred the president’s message. Attempting to be bipartisan constrained the president’s ability to clearly repudiate the policies of George W. Bush and keep past Republican policies and policy failures at the forefront of political discourse. It was not until the 2010 midterm elections that Obama freely invoked his predecessor’s presidency in his rhetoric.

In addition, the White House’s efforts to achieve bipartisan support hindered articulating the positive goals of its proposals. As White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel told the Washington Post, “Rather than jobs being the message, [we had] bipartisanship being the message.”14 As the Democrats would soon learn, it was jobs, not bipartisanship, that concerned the public. In hindsight, White House officials largely agree they should not have let the health care process drag out while waiting for Republican support that would never come. As a top presidential advisor put it, “It lent itself to the perception that he [Obama] wasn’t doing anything on the economy.”15

The quest for bipartisanship also delayed the legislative process and gave the president’s opponents additional opportunities to organize and criticize his proposals. For example, with Ted Kennedy ill, Max Baucus, chair of the Senate Finance Committee, became the lead Senate negotiator on health care and spent months trying to win the support of a few Republican senators, like Chuck Grassley of Iowa and Olympia Snowe of Maine. Few in the White House were pleased with Baucus as their point man, but they were pulled between two competing imperatives—speed and bipartisanship. Emanuel knew that the longer a big, complicated initiative like health care lingered in Congress, the more political freight it would take on. Yet he and Obama were determined to obtain Republican votes to give the effort more legitimacy, and that took patient negotiating.16 In the end, of course, the negotiations failed, and the delays they caused gave opponents additional time to hammer “ObamaCare.”

Finally, negotiating with Republicans risked alienating the enthusiastic supporters who helped Obama in the White House. Although it is not possible to know for certain, the lack of enthusiasm of Democrats about voting in the 2010 midterm elections may be traced in part to the president’s willingness to negotiate, however futilely, with Republicans. Moreover, despite the supposed appeal of bipartisanship to Independents, they were the partisan grouping most likely to change their congressional voting from Democrat to Republican in 2010.17

Receiving little or no support from Republicans, Obama had no choice but to rely on the votes of his fellow partisans. Fortunately for the president, Democrats had large majorities, including the decisive 60th Senate vote secured when Al Franken finally was declared the victor in the Minnesota Senate race and Arlen Specter switched parties. If the president and his Democratic allies were to succeed, they would have to exploit effectively the opportunity provided by the cohorts of Democrats predisposed toward activist government.

These robust majorities brought leadership challenges, however, because they represented a broad range on the ideological spectrum, stretching from the strongly liberal views of large blocs of Democrats in each chamber to the conservatism of Ben Nelson in the Senate and Bobby Bright in the House.

In the House, the leadership almost always prevailed, even in the face of legislation unpopular with the public such as health care reform. Only on climate change legislation did the Democrats need to rely on Republican votes to pass legislation. Democratic representatives supported the president on average 92 percent of the time on nonunanimous votes in 2009 and 85 percent of the time in 2010 (table 6.3). Democrats from the South averaged 89 percent support for the president in 2009 and 81 percent in 2010.

The core of Democratic support consisted of members elected from districts that Obama carried in 2008. For example, House Democrats who represented such districts voted 199-8 for final approval of the Senate health care bill, 201-1 for Obama’s stimulus plan, 194-1 for federal tobacco regulation, 191-8 for financial reform, and 189-15 for climate-change legislation.18

As public support for the president and activist government eroded, Democratic support for the president’s program declined. Most of the Democratic opposition was from cross-pressured members from more conservative constituencies than the typical member of the Democratic caucus. Twenty of the twenty-four Democrats who voted against the original passage of the Helping Families Save Their Homes Act were from McCain districts, as were fifteen of the twenty Democrats who opposed the FY 2010 budget resolution, and twenty-nine of the forty-four Democrats who opposed the climate-change bill.

Democrats were aware of dissatisfaction in their constituencies and acted strategically to try to preserve their seats while at the same time supporting the White House as much as they could. Two of the most controversial votes in the 111th Congress were on health care and climate-change legislation. Thirty-seven House Democrats did not support the leadership on just one of these issues, which allowed them to point in future ads to an instance in which they “bucked the leadership.” Sixteen, almost all of them from GOP-leaning districts, who voted for the climate-change bill pivoted to vote against health care reform. Similarly, twenty-one House Democrats, many of them from Rust Belt blue-collar districts, who opposed climate change backed health care reform.

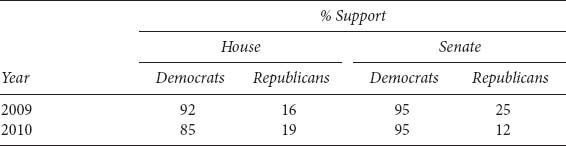

TABLE 6.4.

Support for Major Obama Initiatives and Success in Midterm Elections of House Democrats Representing Districts Won by McCain in 2008

When the House passed the bill to increase the federal debt ceiling by $290 billion in December 2009, by a vote of 218-214, thirty-nine Democrats joined all Republicans in opposition. Thirty-two of thirty-nine Democrats who voted “no” were first- or second-term members who represented districts that they wrested from Republican control. Of the twenty-six House Democrats who captured Republican-held districts in the 2008 election, twenty bucked their party leadership and voted with the Republicans on the debt limit bill. The Democrats in opposition included Paul W. Hodes of New Hampshire and Kendrick B. Meek of Florida, who typically sided with their party but who were running for open Senate seats in 2010.19

The Democrats elected in districts that preferred John McCain did not support Obama and the House leadership nearly as reliably as did those from more Democratic districts. National Journal looked at eight key votes in the House in 2009 that were crucial to the Obama agenda: the economic stimulus package; the budget resolution; climate-change legislation; student-loan reform; the health care overhaul; financial regulation; the debt ceiling increase; and the jobs bill. Democrats representing districts won by John McCain dissented from the Democratic majority, on average, on three of the eight key votes.20

The second and third columns in table 6.4 show how Democrats representing House districts won by McCain voted on four key issues in the 111th Congress. Except for the stimulus bill, a majority of Democrats from these districts opposed the key Obama proposals. Other Democrats, as we have seen, overwhelmingly backed the president.

By comparing the last two columns of the table, we can also see that it was appropriate for Democrats representing McCain districts to feel electorally insecure. They were likely to lose their seats no matter how they voted. Indeed, Democrats lost thirty-six of the forty-eight seats they held that McCain had carried in 2008. The greatest difference among the policies was with health care reform. Only 10 percent of this group who voted for the president’s proposal won reelection, while 36 percent of those who opposed Obama won. With the stimulus bill, 23 percent of those voting for it won reelection, in contrast to a 40 percent rate for those opposing the bill.

Often constituency and ideological influences on the more moderate House Democrats reinforced each other. For example, twenty-three House Democrats voted against both health care reform and the cap-and-trade climate bill. Nineteen of these were right of the House’s center, seventeen were from the South, and eighteen represented districts won by John McCain.

In 1994, the last time that a House Democratic majority was swept away, Democrats held 258 seats, just as they did after the 2008 elections. Ten Democrats from districts carried by President George H.W. Bush in 1992 voted against both the 1993 Clinton budget and the assault weapons ban in the 1994 crime bill. All ten won reelection. So did eleven of the nineteen Democrats from Bush districts who voted for only one of those measures. Conversely, only three of the ten Bush-district Democrats who voted for both measures survived the Republican wave.21

In the 111th Congress, Democratic leaders, including Speaker Nancy Pelosi and White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel, understood that their House majority was built on a layer of conservative-leaning districts won under highly favorable conditions in 2006 and 2008. Having no wish to lose their majority in 2010, they actively discouraged members from some of those districts from voting in ways that would be construed as out of tune with their constituents.22 On climate-change mitigation, health care reform, debt limit, and campaign finance legislation, the Democratic leaders managed to get the bill passed with just over the minimum votes necessary while giving maximum cover to their potentially vulnerable incumbents. Christopher Van Hollen, the chair of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, signaled to members that they were free to vote their districts. “We can do both. . . . I am OK with members being independent-minded.”23

Nevertheless, many vulnerable House Democrats took the risk to give the president the benefit of the doubt. This courage pleased Republicans. Speaking of Democrats’ support for liberal legislation, Thomas Price, the chair of the Caucus of House Conservatives, happily declared, “Rarely do we see members of Congress vote against their own political survival in favor of their leadership so often.” He called such votes an “absolutely unique-in-our-history activity on the part of representatives where they’re not representing their districts over and over and over again.”24

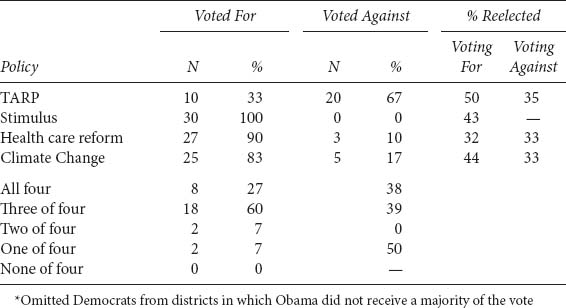

TABLE 6.5.

Support for Major Obama Initiatives and Success in Midterm Elections of House Democrats Representing Districts Won from Republicans in 2006 and 2008*

Table 6.5 shows how another set of cross-pressured Democrats, those representing districts won from Republicans in 2006 and 2008, voted on the four key issues. I have omitted the Democrats who also represented districts that Obama lost in 2008 to prevent overlap in the data. These Democratic representatives offered the president much more support than those from the McCain districts analyzed in table 6.4. Aside from TARP, they gave Obama high levels of support, ranging from 83 percent on climate change to 100 percent on the economic stimulus. These members were either more liberal than the members from McCain districts (it is difficult to say, because many members in both groups were new) or felt safer in taking a risk to support the president.

Apparently, these Democrats knew their districts, and their support for Obama’s initiatives pleased many of their constituents. Despite the fact that they represented districts that had recently elected Republicans to the House, 43 percent won reelection. As the last columns of table 6.5 show, those supporting TARP and climate-change legislation were more likely to win reelection than those who opposed them. Ninety percent supported health care reform, and they won at the same rate as the three who opposed it.

The necessity of reaching the 60-vote threshold in the Senate put a premium on party unity. Democratic leaders often had to muster every single member of their caucus behind a vote. They continuously had to cajole recalcitrant members and alter legislation to suit senators most likely to defect.

The governing core was the thirty-seven Democratic senators elected from the states that had supported the party’s presidential nominees in at least two of the previous three elections. These senators had almost perfect party unity scores in 2009 and 2010, as calculated by Congressional Quarterly. Around that axis, Democratic leaders assembled shifting coalitions of Democrats from states that were more closely divided.

Ultimately, they were remarkably successful. On the most historic votes, those on the stimulus plan and health care reform, every Senate Democrat backed Obama. Democratic senators supported the president on average 95 percent of the time on nonunanimous votes in both 2009 and 2010 (table 6.3). Only a few senators, Evan Byah, Claire McCaskill, and Russ Feingold, varied much around the mean. The seven Democrats from the South also averaged 95 percent support for the president, as did Joe Lieberman. In both 2009 and 2010, Senate Democrats voted with their caucus colleagues 91 percent of the time on party unity votes, eclipsing their record of 89 percent set a decade earlier.25

The high level of Democratic cohesion on votes dividing the parties obscures the considerable difficulty of achieving it. Figures on presidential support do not represent issues, such as legislation on immigration, climate change, “don’t ask, don’t tell,” food safety, and campaign finance, that never came to a vote because the Democrats could not agree among themselves. Nor do they reflect the dilution of legislation to please a few holdouts on economic stimulus, health care, financial regulation, and other matters.

Their impressive record of victories should not obscure the challenges the White House and Democratic leaders faced. A substantial number of House Democrats voted against the president on many of the most important bills. When the House passed Democrats’ cap-and-trade energy legislation in June 2009, forty-four Democrats voted no. Thirty-seven voted against increasing the debt limit, thirty-six opposed campaign finance reform, thirty-five opposed jobs creation measures in 2010, twenty-seven voted against the initial version of financial regulation reform (nineteen opposed the final version), twenty-six opposed “don’t ask, don’t tell,” and twenty voted against the FY 2010 budget resolution and the overhaul of food safety regulation. Given Republican unity in opposing Democratic initiatives, it is ironic that the bipartisan position was typically in opposition to the White House.

Health care reform illustrates the president’s problem in holding his party coalition together. Democrats in both chambers engaged in protracted negotiations to try to reach agreement, repeatedly derailing the White House’s schedule. They disagreed on a host of provisions, ranging from funding for abortions to a public option for health insurance.

At times, Democrats who favored remaking the health system attacked fellow Democrats who were undecided or opposed an overhaul. The Democratic National Committee, for example, ran ads intended to pressure Democratic senators like Kent Conrad, Evan Byah, Bill Nelson, Mary Landrieu, Blanche Lincoln, and Ben Nelson. Some ads were aimed at bolstering moderate and conservative House Democrats who needed ammunition to counter the intense campaign against revamping the system. Liberal groups like MoveOn. org, Health Care for America Now, Change Congress and its sister group Progressive Change Campaign Committee, and the Service Employees International Union sponsored more personal attacks against a few conservative House and Senate Democrats who voted against a Democratic health bill in committee or who were otherwise unsupportive.26

Liberal activists also ran television advertisements against moderate Democrats who were not supporting the public option. White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel berated them as being counterproductive. Later, the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, a group formed in 2009 to advocate for liberal candidates and issues, ran ads in Emanuel’s political base of Chicago (where he would eventually run for—and become—mayor). The ad featured a voter from Emanuel’s old congressional district describing troubles with a health insurer. “A lot of us back home hope Rahm Emanuel is fighting for people like us as White House chief of staff,” the man said into the camera. “But if he sides with the insurance companies and undermines the public option, well, he won’t have many fans in Chicago.”27

In the battle over health care, both sides targeted a few dozen moderate Democrats and a dozen anti-abortion Democrats.28 The president had to make a personal visit to the House on the day of the first vote on the health care bill in November 2009 to bolster his troops. Nevertheless, the bill only passed on a 220-215 vote. Thirty-nine Democrats—more than 1 out of 7—voted against the White House and the Democratic leadership. Thirty-one of these members represented districts won by John McCain in 2008. Fourteen were freshmen and twelve were from districts that switched from Republican in 2008. Twenty-four were in the Blue Dog coalition of fiscally conservative Democrats. Dennis Kucinich of Ohio also opposed the bill—because he wanted a more liberal policy. Artur Davis of Alabama, who was running for governor in that conservative state, could not risk supporting the bill.

Following the election of Scott Brown in Massachusetts in January 2010, it became clear that the House would have to vote to accept the Senate health care bill, and it did so on March 21, 2010. Thirty-four Democrats voted “no,” however, including five who had voted for the House version months earlier. Twenty-nine Democrats voted no on both versions of the bill. Only the switch of eight Democrats from “no” to “yes” saved the bill.

District competitiveness (and thus a representative’s vulnerability) strongly influenced Democrats’ votes on health care. None of the twelve Democratic representatives running in a constituency (their congressional district or the state if they were seeking statewide office in 2010) where Obama won less than 40 percent of the vote in 2008 supported the final version of health care reform. In addition, only thirteen of the thirty representatives running where the president won 40-49 percent of the vote supported the bill. On the other hand, all but seven of the 195 Democrats running in constituencies that Obama won voted for health care reform.29

Ideology mattered too. All but two of the 152 most liberal Democrats voted for the final version of the health care bill, as did forty-four of the next fifty-one most liberal. However, only twenty-five of the fifty most moderate or conservative Democrats supported passage.30 Just over half of the conservative Blue Dogs coalition supported the bill.

Anti-abortion sentiment also made some difference in support for the bill. Twenty-four of the sixty-two Democrats who voted yes on the amendment to restrict funding for abortions voted against the final bill, while all but ten of the 191 Democrats voting no on the amendment supported the bill.

Exploiting opportunities requires effective leadership. We saw in chapter 5 that the White House relied heavily on the very effective congressional party leaders to craft coalitions and then intervene at strategic points toward the end of the legislative process. It is difficult to determine the president’s impact, but the fairest statement is probably that it was modest. We have seen, for example, that the most aggressive effort to persuade Congress during the Obama presidency was on the House’s consideration of the Senate’s health care reform bill in March 2010. The president was fully engaged, as was the House leadership. Nevertheless, the net gain among House Democrats over the initial approval of health care reform the previous November was three votes.

At the same time, these votes were critical at the margins of coalition building. Moreover, it is reasonable to argue that votes were much more difficult to obtain in March 2010 than in November 2009, especially after the victory of Scott Brown in the Massachusetts Senate election to fill Edward Kennedy’s seat. Thus, the full court press may have held onto Democratic votes that might otherwise have slipped into opposition.

Not every Democrat responded to the president’s pleas for support.31 The president also called Democratic Representative Chet Edwards, the only member of the House on his public list of potential vice presidential candidates in 2008, asking for his vote on health care reform on the original House vote. Edwards declined “respectfully.”32

At a party on March 17, 2010, to toast the enactment of a law imposing “pay as you go” budget restrictions, Obama put his arm around Representative Jason Altmire’s shoulder, turned away from the others, and leaned in close to the congressman. “We have to do this,” Obama said about the health care reform bill. “It is essential to bringing down the deficit.” “I want to represent my district,” Altmire replied. “As you know, it is politically split.” As the president moved toward a lectern to address the entire room, Rahm Emanuel, who helped Altmire win his seat in Congress in 2006, cornered Altmire. “Your constituents like you; you’ve built up a reservoir of goodwill,” Emanuel argued. “You have an opportunity before this vote to go back home and explain it to them.”33 The next day, Altmire was back at the White House for a meeting with centrists in the New Democrat Coalition.

Despite the high-level attention at the White House St. Patrick’s Day party, a sit-down with Emanuel, a few more phone calls from the president, and three from Cabinet-level officials, Altmire e-mailed the chief of staff two days before the final vote to say that he planned to announce that he would vote no. “Don’t do it,” Emanuel punched back on his BlackBerry. Nevertheless, that afternoon Altmire released his statement. At 7:30, Obama called once more. “I want to give you something to think about before the vote,” the president said gently into the phone. “Picture yourself on Monday morning. You wake up and look at the paper. It’s the greatest thing Congress has done in fifty years. And you were on the wrong team.” In the end, however, Altmire joined thirty-three other Democrats in voting against the president.

The White House had better luck with Representative Melissa Bean, employing a good cop/bad cop approach. After one group meeting, Obama asked her to stay behind. “Let me talk to my homegirl,” he joked. They compared notes on their families—both have two daughters. Then Obama made a gentle plea: “These reforms are really important.” A few days later, Emanuel was more direct, reminding Bean of the support he lent in her campaigns and why she came to Washington. “You ran because you care about the deficit,” he said. “This is north of $1 trillion in deficit reduction.” Bean wanted to see the final bill and a cost estimate. “The Senate bill is stronger than the House bill, and you voted for the House bill,” Emanuel countered. “Melissa, name me once in the last six years you voted for a bill with more deficit reduction,” he asked, and added that if she opposed the health care legislation, “don’t ever send me another press release about deficit reduction.” She voted yes.

Despite the Obama White House’s efforts to reach across the aisle, bipartisanship was not a success. Critical features of the context of the Obama presidency, especially the high levels of partisan polarization in the public and Congress that we discussed in chapters 1 and 4, made it unlikely that the president would obtain any significant Republican support for his core initiatives. Only if Obama would adopt Republican policies would he receive Republican support—and no one should have expected him to become a hard right conservative.

Lacking Republican support, the president had to rely on his party to change policy. Democrats gave the White House very high levels of support. The White House strategy of applying pressure quietly while letting congressional leaders find ways to build coalitions proved to be a wise one. Nevertheless, moderate Democrats representing conservative constituencies frequently voted with the Republicans in opposition to the White House.

The president was dependent on exploiting the opportunities presented by those disposed to support his initiatives. He could not create opportunities to expand his support in Congress. In this limitation, Obama was no different from other presidents. The impact of persuasion on the outcome of congressional votes is usually relatively modest. Conversion is likely to be at the margins of coalition building in Congress rather than at the core of policy change.

It should be no surprise that presidential legislative leadership is more useful in exploiting opportunities than in creating broad possibilities for policy change. Efforts at influencing members of Congress occur in an environment largely beyond the president’s control and must compete with other, more stable factors that affect voting in Congress in addition to party. These influences include ideology, personal views and commitments on specific policies, and the interests of constituencies. By the time a president tries to exercise influence on a vote, most members of Congress have made up their minds on the basis of these other factors. As a result, a president’s legislative leadership is likely to be critical only for those members of Congress who remain open to conversion after other influences have had their impact. Although the size and composition of this group varies from issue to issue, it will almost always be a small minority in each chamber.