Major conventional arms–exporting states now widely support the Arms Trade Treaty and other multilateral arms export initiatives. Why they have done so—in the absence of material gain or norm socialization—not only presents an important empirical puzzle but also addresses several enduring questions for IR theory: Why do states commit to international agreements, especially those that may impose high implementation costs without material benefits in return? What explains norm adoption by “critical” but skeptical states? How does social change take place in the international system? This chapter outlines a theoretical argument about social reputation in international and domestic politics to give fresh insights into these questions through the lens of “responsible” arms export controls.

In this case, states confront both enduring material pressures to avoid multilateral commitments and increasing normative pressures from other states and NGOs to make those commitments. How states reconcile these conflicting pressures and why provide a window into their motivations and priorities in international politics as well as into how broader normative change can occur. In recent years, most top arms supplier states have conformed to normative pressures to commit to humanitarian arms export initiatives. At the same time, they have worried that their support will entail costs for their sovereignty and national security as well as harm their defense industries and domestic economy. Even as states have adopted policies in line with new norms, norm internalization has not caught up with state practice, and compliance is mixed at best. But if norm adoption is instrumental, as it appears to be, what do states hope to get out of it? Without the promise of material gain, why expend time and resources on multilateral initiatives intended to impose costly restrictions on decision making and risk domestic legal challenges and hypocrisy costs if compliance is weak?

This chapter proposes a theory of state behavior that highlights the importance of social reputation to explain states’ commitment to and varied compliance with “responsible” arms export norms. Beyond the arms trade, the theory seeks to contribute to research on international security, norm development, and global governance. I begin with a brief overview of the argument and then review existing IR approaches to reputation. These approaches focus on the economic and military benefits that a reputation for credibility can provide, but they do not acknowledge reputation more broadly as a social concept.1

First, I argue that states care about their reputations for not only material but also social reasons attached to their self-image, legitimacy, and standing in international politics. States may strategically commit to new policies out of concern for their international reputations and the social benefits (or costs) that a good (or bad) reputation can bring. Second, I introduce concern for domestic reputation as a source of variation in states’ compliance. Compliance efforts will be stronger in democracies where export transparency and civil society activity are high, making leaders more vulnerable to reputational damage from scandalous arms deals. Finally, I suggest that alternative explanations have difficulty accommodating cases in which there are gaps between commitment and compliance. Where the international normative environment has changed but norm internalization is slow to emerge, social reputation may provide a more satisfying explanation for states’ policy and practice.

THE ARGUMENT IN BRIEF

Major arms supplier states see neither security nor economic gain to be had from committing to responsible arms trade initiatives. Quite the opposite, in fact: they have long avoided multilateral export controls because of their high costs to security, foreign-policy autonomy, and economic well-being. Instead, states support new arms export initiatives as a means to maintain, repair, or better their reputations as responsible citizens of the international community on the “right side” of conventional arms control. They may strategically support popular norms and policies in order to receive the social benefits a good reputation can bring, such as a positive self-image and increased international legitimacy. Here, norm adoption is instrumental, done to reap social benefits and avoid social costs. Yet without international enforcement and accountability mechanisms to trigger compliance-related reputational concerns, states may avoid costly policy implementation. Where international politics does not offer compliance incentives, the task may fall to domestic politics. In particular, democracies with arms export transparency and NGO activity at home may improve efforts to implement their formal policy commitments in practice in order to protect their domestic reputation from the damage of scandal.

The argument proceeds in two parts. First, states deeply embedded in the international community and its institutions may formally commit to popular multilateral initiatives out of social concern for their reputation among their peers. As the international normative environment has increasingly linked arms transfers to human rights, so too have the related standards by which states collectively judge their legitimacy and standing. Major exporters have pursued arms transfer restraints to conform to new policy expectations in this changed normative environment out of a desire to uphold or improve their international reputation. Their policy commitment seeks to signal that they possess the qualities of good international citizens, supporting peace and human rights. These states respond to social incentives and benefit not in the form of material profit, but rather in the form of social recognition in a deliberate strategy to confirm their self-images and contribute to their external social influence. Unlike other IR approaches, the approach taken here acknowledges an important social dimension to reputation. It does not view reputation solely as a means to material ends based on a catalog of states’ past actions. Instead, it recognizes a role for reputation both as an end in and of itself, having an internal “feel-good” effect on state identity, and as a means to additional social benefits in the international community.

This social reputational dynamic can explain why otherwise skeptical states with significant material stakes in the status quo may nevertheless support new norms and policies. Indeed, the most skeptical states in the case examined here—top exporters of small and major conventional arms—are also the most critical for enabling new norms to reduce arms availability to human rights violators. These states’ largely supportive response to the norm cascade is both instrumental and social. Yet although their policies are available for all to see, their arms trade practices are more easily hidden from international scrutiny. States can therefore reap the reputational rewards of adopting “responsible” policies without necessarily paying the costs of equally “responsible” implementation. Such a gap between commitment and compliance can easily go unpunished in international politics, where transparency is poor and agreements—such as the ATT—lack enforcement capabilities.

The second part of the argument introduces a role for domestic reputation, often overlooked by other IR approaches to reputation, in explaining variation in states’ concern for compliance with new rules and norms. It finds that governments faced with scandal or threat of scandal are more likely to seek improvements to their export practice (not “just” to policy) out of concern for their domestic reputation. Where arms trade practice remains relatively unmonitored at home, the risks of scandal and its effect on the reputation of a state and its leaders are low. However, policy makers in democracies with an active civil society and domestic transparency measures are more sensitive to threats of arms trade scandal. In response, they may attempt to conform more closely to export standards—at least in clear-cut cases of norm violations—rather than suffer the reputational costs of scandal.

Scandals link reputation to domestic politics by highlighting the violation of fundamental societal values. Although arms trade scandals rarely swing elections, they nevertheless erode the image and legitimacy of leaders in the eyes of their constituents and provide an opening for presumptive leaders to win support in their place. This dynamic is most viable in democracies, where transparency and accountability are valued norms of governance and where civil society can mobilize to take governments to task when behavior contravenes stated policies, domestic values, and national identity. Scandals are, in a sense, an extreme and widespread consequence of shaming, hypocrisy costs, or rhetorical entrapment. Without any formal enforcement capacity, the ATT’s long-term effectiveness may lean heavily on such civil society engagement and developments in transparency to tap into states’ domestic reputational concerns and motivate some compliance. Policy commitment may serve an international audience, but compliant practice—at least for some states—may serve a domestic one.

REPUTATION IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

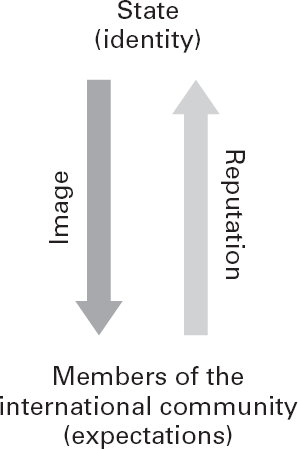

Reputation is a prevalent but often undertheorized concept in IR. The Oxford English Dictionary (1989) defines reputation as “the common or general estimate of a person with respect to character or other qualities; the relative estimation or esteem in which a person or thing is held.”2 But why does reputation matter? According to most IR scholars, reputation is valuable because it informs predictions of states’ future behavior, whether as a credible military ally or opponent or as a credible partner in multilateral cooperation. A reputation for credibility, in turn, is a means to increase states’ military power or economic gain. These motivations, however, fail to capture the reputational benefits accrued from supporting “responsible” arms transfer policy, which are not primarily material but social and focus on the esteem component of reputation. In this section, I outline the standard uses of reputation in IR before I discuss reputation as a social concept. For an overview of the three IR approaches to reputation, see table 2.1. I test the first approach in the chapters to come.

TABLE 2.1. REPUTATION IN INTERNATIONAL POLITICS

| |

Image and social status |

Credible threat |

Credible cooperation |

| Why does reputation matter? |

Affirm positive self-image in line with views of national identity and social influence |

Effective threat making; crisis decision making with limited information |

Ability to enter into profitable cooperative arrangements |

| What is the purpose of reputation? |

Attain and maintain social standing, legitimacy, and influence in international and national politics |

Predict behavior; signal resolve to follow through with threats |

Predict behavior; provide information about own reliability as a partner; regime maintenance |

| What reputation is desirable? |

Good international citizen, transparent and accountable |

Action, resolve, toughness |

Reliable, cooperative, compliant |

| How do states build their reputations? |

Policies in line with societal and international norms |

Follow through on threats |

Comply with international agreements and regimes |

| Target audience |

Domestic and international |

International |

International |

| Other fields of research |

Sociology, anthropology, social psychology, international law |

Game theory |

Game theory, economics, corporate management, international law |

Jonathan Mercer defines reputation as “a judgment of someone’s character (or disposition) that is then used to predict or explain future behavior” (1996:6). To form a reputation, he continues, it is necessary for an observer of an actor’s behavior to use “character-based attributions” to explain its present behavior and attach these judgments to expectations of future behavior (6, 36). IR scholarship typically emphasizes the second part of Mercer’s definition: reputation’s ability to serve as a tool to predict future behavior. Broadly speaking, certain reputations help states get what they want, whether acquiescence to threats or profitable cooperative arrangements. The ability to extract these material gains hinges on the belief that past or present behavior is indicative of likely future behavior. In this sense, reputation is primarily a proxy for past action. This version is often used in international security and political economy research. Although not to be discounted, it is less useful in explaining states’ commitment to “responsible” arms trade initiatives, which also stems from reputational concerns but is geared toward social—not military or economic—advantage.

CREDIBLE THREATS

From a security standpoint, states or leaders seek to build a reputation for making credible threats. From this perspective, threat making and deterrence work because states believe that opponents who demonstrated resolve in the past will demonstrate resolve in the future. States want to stand firm against coercive pressure, and they want their own threats taken seriously. As a result, Thomas Schelling argues, the interdependence of a state’s worldwide commitments makes its reputation for action—not its status, honor, or worth—“one of the few things worth fighting over” (1966:124).3 Reputation also supplements information about an opponent’s likely actions and relative power in order to “assess their strategies in crisis situations” (Crescenzi 2007:385; see also Axelrod 1984 and Crescenzi, Kathman, and Long 2007).

In short, states worry about their reputation because they believe it affects their ability to make credible—and therefore effective—threats. Past behavior serves as information to make more accurate predictions about other states’ behavior in a military crisis, revealing their “type” to be strong or weak (Hugh-Jones and Zultan 2012; Walter 2009). Although Mercer (1996) maintains that the content of a state’s reputation also depends on its relationship with the observer state, the value of its reputation is still the same: a tool to enhance military credibility.4 Daryl Press’s (2005) critique goes further, arguing that states do not actually take their adversaries’ past behavior into account when making decisions during a military crisis. Nevertheless, he notes that states often do seek to protect their own reputations—a puzzling finding for this variant of reputation, whose rationale depends on reputation mattering because of the material outcome it can provide.

Because this use of reputation is threat oriented, it makes at best only a distant connection to arms transfer control policy. Certainly, if a state uses weapons supplies as a coercive tool—requiring another state to comply with its demands or face a cessation of its arms supplies—such threats will be effective only if the recipient believes the supplier state will indeed cut off arms. This use of reputation may relate to the threat and effectiveness of arms embargoes, but it does not address supplier states’ willingness to adopt humanitarian export constraints.

CREDIBLE COOPERATION

For scholars of international political economy, reputation is again about credibility and information, but for cooperative ends rather than for conflict. Compliance with current agreements can serve as an indicator of likely future compliance. Because states cooperate to improve their economic welfare, having a reputation for reliability can “[make] it easier for a government to enter into advantageous international agreements; tarnishing that reputation imposes costs by making agreements more difficult to reach” (Keohane 1984:105–6; see also Guzman 2002; Larson 1997; Sartori 2002; Tomz 2007). Concerned about their reputations as precedent for an unspecified number of future rounds of cooperation, states will keep their commitments, even without specific threats of retaliation for noncompliance (Guzman 2002; Keohane 1984). In deciding whether to enter an agreement with another state, states also determine whether their potential partner can be trusted on the basis of “[its] reputation for fulfilling commitments, the public record of [its] reliability” (Larson 1997:710; see also Ahn, Esarey, and Scholz 2009; Guzman 2002; Sartori 2002; Tomz 2007).5 Here again, a state’s behavior reveals information about its type to other actors, forming a reputation to help potential partners decide if its commitments to cooperate are credible.

Even for J. C. Sharman, who explicitly seeks to offer a “social” version of reputation in international political economy (2006:6), states’ concern for reputation is driven by a profit motive (107). He argues that states act to protect their reputations out of fear of being shunned by investors (10). A reputation for credibility thus matters for the material costs and benefits it provides. But whether investors use reputation in this way is not always clear.6 Moreover, states expect neither enhanced military power nor economic profits from “responsible” arms export controls. In fact, profit incentives may work against them. Restraints shrink available arms markets and reduce profit opportunities. Cutting off arms supplies may also make a government less economically competitive against suppliers with fewer scruples and brand it as an unreliable partner. In a competitive buyer’s market, commitments to rule out or drop certain categories of customers do not sit well with companies’ bottom lines. Instead, to understand why states support such costly standards, it is useful to look to the social benefits and pressures created by reputation.

SOCIAL REPUTATION AND CONVENTIONAL ARMS TRANSFERS POLICY

The version of reputation I develop here emphasizes reputation as a judgment of states’ character and not simply as the sum total of their past actions. As such, it differs in a number of respects from the variants just outlined. First, it recognizes the importance of reputation as a policy end, not solely as a means to achieve other policies. States attach social value to their reputations and may commit to policies as a means to enhance their reputations. Second, it considers a role for domestic reputation linked to compliance. Governments’ concern for reputation can have tangible domestic effects when conditions are ripe for scandal brought on by a gap between professed policies and irresponsible practice, revealed in the public domain. Finally, it creates an opening to consider a more eclectic theoretical view of international politics. States are strategic actors operating in a social setting where norms and institutions affect the behaviors that are collectively valued and that build reputation. States adopt policies to enhance their reputation in the international community; they apply rational strategies to achieve social goals.7 Reputation is therefore a concept that can apply to both rationalist and constructivist research and serve to find an area of common ground between the two.

In a new normative environment linking arms transfers to human rights, states face social pressures at the international level to commit to responsible arms transfer controls. As a group, democracies are the most likely to respond to these pressures: their domestic obligations to the rule of law and other democratic values can translate to international politics (Doyle 1986; Simmons 1998; Slaughter 1995). In addition, democracies are subject to greater internal and external pressure to conform to international norms related to peace, human rights, and international law (Burley 1992; Simmons 1998). Nondemocracies can also face external social pressure to conform to norms,8 but without the added expectations attached to democratic values and the rule of law. After all, the ATT has been overwhelmingly supported by democracies and nondemocracies alike. Moreover, skeptical states such as Russia and China have kept a low profile and refrained from blocking ATT progress, despite their distaste for its sovereignty costs and the domestic human rights standards it seeks to enforce. Reputational concerns may therefore keep dissenting states from publicly voicing opposition. Nevertheless, in general, social reputation tends to be a more powerful commitment incentive among democracies due to shared values and the social pressures to conform to them.

At the domestic level, the link between reputation, scandal, and compliance is confined to democracies. Although corruption can occur anywhere, scandals need democracy, where political power is subject to popular accountability and sanctioned by strict rules of legal process (Markovits and Silverstein 1988). Scandals also rely on democratic expectations of transparency and free media to flourish in the public eye. Later in the chapter, I describe the conditions that make some democracies more sensitive to the threat of arms trade scandal and the reputational damage it can inflict. However, the vulnerability of more scandal-prone governments to reputational damage may be tempered by the structure of executive responsibility.9 The effects of scandal may be more potent where executive responsibility affects the whole party in power and is not dependent on drawing a clear link to a single leader at the top. Because of the difficulty of directly implicating a single executive for irresponsible state action in this case, leaders in presidential systems may be less concerned about reputational damage from arms trade scandal. In contrast, in parliamentary systems, the party in power can suffer collectively in response to scandal and may be more likely to adjust its behavior accordingly. I detail both the international and domestic reputation arguments in the following sections.

REPUTATION AMONG STATES

REPUTATION AS A SOCIAL INCENTIVE

At the international level, states may strive to maintain or improve their reputation by adopting policies in line with rules and norms of the international community and its institutions in order to signal their “good international citizenship.” In the traditions of constructivism and the English School, I observe that international politics can foster social standards and encourage social behavior on the part of states. And, like Ian Hurd (2007) and Alastair Iain Johnston (2008), I argue that states are rational actors within a social context. When material incentives to cooperate or comply are absent—or material costs are present—social incentives can nevertheless motivate leaders to commit to popular initiatives. States’ concern for reputation and how others in the international community view them can prompt support for policies they might otherwise oppose.10 States care about their reputations, first, as a positive reinforcer for their self-image and identity. A good reputation has a feel-good effect on state identity. Second, states care about their reputations because of the implications for their legitimacy and social standing, particularly within international institutions, which can set behavioral expectations and advertise states’ policy commitments. Moreover, reputation not only is important to states in the abstract but is also connected to and carried by its individual diplomats and elites meeting in international fora as representatives of their countries.11

Many states that once shunned multilateral conventional arms export standards now support them because they want to be viewed as conforming to international norms. In contemporary politics, “good” or “responsible” international citizenship broadly refers to a state’s active commitment to human, social, and economic rights or other collective goods (Lebovic and Voeten 2006; Wheeler and Dunne 1998), which states can signal through their policy choices.12 The value of a good reputation attached to conventional arms control is not derived from anticipated increases in procurement or overseas sales. As I show in chapter 4, industry has been slow to back government initiatives to the extent that it has at all, and benefits directly connected to increased power and economic gain are negligible to nonexistent. Nor do states appear to possess deeply internalized normative convictions about new policies. Rather, it requires a broader understanding of reputation, connected to social standing and recognition, to explain states’ willingness to support “responsible” arms transfer standards.

International relations research typically describes social status as a tool of small or weak states to gain political influence in global politics that is not available to them through traditional military or market power (Ingebritsen 2006). Yet social goals can also be sought by more powerful states embedded in the international community (Johnston 2008). International embeddedness both reduces states’ insulation from international rules and enhances their desire for social standing. A good international reputation typically requires states to participate in rules, norms, and responsibilities recognized as legitimate by international society (Chayes and Chayes 1995; Franck 1990; Wendt 1999; Wheeler and Dunne 1998).13 States seek both “conformity and esteem” in international politics, stemming from social pressure and a desire for legitimation from their peers (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998:903). Even where norms are not internalized, states may therefore be socialized to conform to expectations in order to gain recognition and prestige while avoiding shame and social opprobrium (J. Busby 2008; Johnston 2008; Zarakol 2011).

As a judgment on states’ policies and actions, reputation is wrapped up with states’ internal or self-images as well as with how they are perceived by other international actors. The term image can refer both to how a state sees itself (i.e., its national self-image14) and to how it wants others to see it (i.e., the external image it projects from its policies and practice15). It is this latter external image that shapes a state’s reputation, which is a judgment by others of the images that a state projects, intentional or otherwise. Although states cannot control this collective judgment—reputation is, after all, relational and defined by others—they can seek to shape it through their publicly observable behavior (Jervis 1970; Klotz 1995; O’Neill 2006). Image management is essentially the point of public diplomacy and “nation-branding” campaigns. As actors try to “control the impression” other actors have of them, they play a social part to their audience over time that reinforces an acquired value system, whether their behavior is sincere or not (Boulding 1956; Goffman 1959).16 Figure 2.1 captures this relational component of reputation and the role of image in shaping it. In this sense, reputation serves as feedback to a state from others in the international community about the image it projects.

Reputation contains two interwoven dynamics that make it a persuasive social incentive among states tightly bound to the international community. As Axel Honneth (1995) argues, social recognition brings self-respect and a confirmation of equal status as well as esteem and increased standing in a community of shared values. First, states and their leaders seek to confirm their equal status and with it their identities as good international citizens. A good reputation confers and reinforces a positive self-image. States keep up with evolving norms of appropriate behavior in part to be recognized as legitimate and equal members of the international community (Abdelal et al. 2009; Wendt 2004; Zarakol 2011). Normative obligation is “a necessary reciprocal incident of membership in the community” (Franck 1988:753) and helps define its “boundaries and distinctive practices” (Abdelal et al. 2009:21; see also Chayes and Chayes 1995; Franck 1990; Henkin 1968; Wendt 1999). By conforming to international expectations, states can develop reputations that align more closely with their identities and can be recognized by their peers as equals with the capacity and right to act in international affairs.17

FIGURE 2.1. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN REPUTATION AND IMAGE.

Source: Based on Whetten 1997.

Second, states may seek not only to be recognized as equals but also to distinguish themselves among their peers. Policy leadership and a good reputation can bring increased social standing or prestige.18 This aspect of reputation refers to a state’s position in a social hierarchy of “respect, deference and social influence,” valuable as both a means to gain influence and an end in itself (Ridgeway and Walker 1995:281–82; see also D. Bromley 1993; Huberman, Loch, and Önçüler 2004).19 Social hierarchy does not replace the formal anarchy of the international system. Rather, it suggests that some states informally enjoy a more favored and influential position than others, which can stem from hard or soft power.20 States, wishing to improve their reputations, may therefore seek to outperform their peers, particularly with respect to policies on issues close to their self-image (Tesser and Campbell 1980). In this case, some states may adopt “more responsible” policies than prescribed by community norms in order to set themselves apart from other states and enhance their legitimacy, esteem, and prestige.

States’ concern for reputation thus illuminates a search for recognition of their equal status as “good” members of the international community and an effort to increase their standing in that community. Within a group, social status and esteem can be valued for their own sake and sought independently of—or even in place of—material gain (Huberman, Loch, and Önçüler 2004). Alexander Wendt, for example, asserts that among a state’s interests is a “need to feel good about itself, for respect or status” (1999:236; see also Chayes and Chayes 1995; Finnemore and Sikkink 1998; Lebow 2008). More fundamentally, states’ concern for reputation points to a need for social approval within the framework of positively valued identity characteristics of a particular group (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998; Shannon 2000; Tajfel and Turner 1986). In turn, external validation from a state’s peers can serve to confirm and even shape its understanding of its own identity.21 Identity is grounded both in an actor’s internal or self-understanding and in an external interpretation of that identity by other actors (Wendt 1999:224).22 This external interpretation of identity can be and is reflected in a state’s reputation and helps explain why reputation functions as a social concept.

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTIONS AS A SOCIAL SETTING

Reputation is more easily formed in the context of international institutions. Institutions help legitimate rules and norms, leading to actors’ perceptions that they should be obeyed and forming the basis for expectations of appropriate behavior and good international citizenship (Hurd 2007). Institutions also provide a setting for regular and intensive interaction among diplomats, in which peers’ judgments take on greater meaning and socialize states into policy expectations.23 Finally, participation in international institutions can force states to publicly declare their positions, making their policy choices more observable to other actors and therefore subject to social appraisal. As a result, reputation can be more easily assessed and assigned.24 In some cases, institutions may also make peer-review processes and other monitoring mechanisms available to examine state performance.

Institutions introduce an opportunity for states to strategically choose policies to maintain, enhance, or repair their reputations. “Indeed,” Johnston notes, “there is no point engaging in [behavior] for reputational purposes unless [that behavior] is observable to others” (2008:7; see also O’Neill 2006). UN General Assembly votes, for example, put states’ policy positions on public display. Even where consensus rules may mask individual policy choices from public view, diplomats in the room are nevertheless aware of who dissents from the norm.25 As I discuss in chapter 4, multilateral fora on issues related to the conventional arms trade have proliferated in the past decade, providing a community of diplomats who interact regularly and in the process have established policy expectations and the ability to assess whether those expectations are met. For small arms specifically, they have also created institutionalized reviews of states’ policies and aid giving through national reporting to the UN and published assessments of those reports.26

Especially within international institutions, leaders who “value their social standing in international society seek to avoid negative social judgments” and choose policies, behavior, and their justifications for both accordingly (Shannon 2000:294; see also Chayes and Chayes 1995; Johnston 2008; Lumsdaine 1993). Members in a society ostracize, criticize, and punish norm violators just as they reward norm followers, in turn either revoking or granting reputational benefits (O’Neill 1999:197). In this way, reputation becomes a constraint on a state’s actions. States typically prefer to “avoid the social pressures of remaining aloof from a multilateral agreement to which most of their peers have already committed themselves” (Simmons 2009:13). Not only have “responsible” arms transfer controls become a means to enhance reputation, but not adopting them is also seen as having potential reputational costs. Policy opposition may carry social stigma, as the United States discovered when it sought to weaken consensus-driven small arms agreements and cast the sole “no” vote on the ATT initiative until late 2009.

Such forms of social control are recognized as important for the functioning of the less formally codified international community.27 A good reputation reinforces a state’s positive self-image and helps it wield social influence and moral authority by improving its standing and legitimacy. However extensive a state’s hard power, social influence can be a cheaper and subtler resource to bring fellow states’ preferences in line with its own. Indeed, the ability to leverage soft power—“the ability to get what you want through attraction rather than coercion or payments” (Nye 2004:x)—is based on a positive image abroad and suggests that relying solely on military power can be inefficient and counterproductive. States are also “motivated by a desire to avoid the sense of shame or social disgrace that commonly befalls those who widely break accepted rules” (Young 1992:177; see also Zarakol 2011). A damaged reputation can lessen a state’s influence or “political capital” in international politics and its ability to achieve its policy agenda in international institutions (American Political Science Association 2009:7, 12).

This relationship between reputation and influence points to social influence as an additional instrumental motivation behind states’ concern for reputation. Indeed, social reputational concerns illustrate the intimate connection between social norms and strategic behavior. States and their leaders are often motivated by a combination of material and social interests as well as normative expectations.28 Nevertheless, states are limited in how flexible they can be with their reputation-building policy choices, without which their influence also cannot grow. States must adopt and promote policies that reflect the reputation they wish to promote and maintain (Chong 1992; Ingebritsen 2006), while also counteracting any negative images that may serve to undermine their reputation and related influence.29 As Dennis Chong observes, “By not acting on [his or her] self-professed values, each person’s reputation would be diminished in the eyes of the others” (1992:191). The importance of consistency between values and policy30 is multiplied when states take a leadership role to promote a policy on the international agenda (J. Busby 2008; Wheeler and Dunne 1998). In these circumstances, states stake their reputations not only on their own policy and behavior but also on their success in spreading similar policies elsewhere.

LIMITATIONS OF SOCIAL REPUTATION AS A CONSTRAINT ON STATES’ BEHAVIOR

Despite the strong social (and material) incentives that can drive states’ reputational concerns, reputation’s ability to shape states’ behavior can have two main limitations. First, it may operate more strongly within rather than across issue areas.31 Just as individuals or states are often said to have multiple identities, so too can they have multiple, compartmentalized reputations (D. Bromley 1993:44; R. Fisher 1981:130). When it comes to the consequences of reputation for states’ credibility, multiple reputations is a matter of practicality: states must work together over a wide range of issues. To assume that disreputable behavior in one area spoils the credibility of cooperation in all would be inconvenient, costly, and problematic. Nor do states have reason to believe that this would be the case; the value and content of and interest in cooperative behavior also vary across issues (Downs and Jones 2002).32 However, when states’ attention is turned to social concerns for “good international citizenship,” the benefits gained from containing a reputation to one area may be less relevant. In such cases, states perceive their policy choices as contributing to a broader reputation with implications for their legitimacy and standing rather than to separate reputations with implications for their credibility in other issue areas.

Second, reputation’s ability to influence state behavior is limited when states’ policies are observable to other actors but their practices are not. Even when policy is observable and subject to reputational judgment, practice may not be. Transparency measures play a significant role in generating compliance with international norms and treaties (Chayes and Chayes 1995:135; Norman and Trachtman 2005). Because reputation is assessed from observed policy and practice, where transparency is limited, scrutiny of practice must also be limited. Low levels of public information on compliance restrict the evaluative capacity of an issue for states’ reputations and allow for more superficial norm adoption (Guzman 2002; Norman and Trachtman 2005). In the absence of international accountability mechanisms, governments can therefore look forward to the kudos brought on by adopting popular policies, without having to worry about paying high implementation costs—or being punished by other international actors if they do not. Thus, a state may sign on to an agreement with little intention of adhering to its obligations, “especially if it believes that its violations might not be detected” (Henkin 1968:34). Although some might dismiss such behavior as “cheap talk” or “mere window dressing,”33 social reputational concerns can explain why states bother to commit to invest in such commitments at all. States are willing to risk potential—but by no means certain—hypocrisy costs or rhetorical entrapment in the future to receive what they see as certain social benefits (and to avoid social costs) in the present. Moreover, where either norms or behavior are ambiguous, a state may more easily deny accusations of noncompliance to reduce its reputational damage (Guzman 2002:1863).

The social reputation argument therefore suggests that a convergence of practice and policy—although conceivable without public scrutiny of state practice34—is less likely without more comprehensive and widespread transparency and accountability measures. Costly rules, standards, and norms may be adopted into policies not for their inherent value but (at least initially) for the value of the reputation to which they contribute. For the conventional arms trade, international monitoring and evaluation of export practices are largely absent, even where trade information is available. Indeed, despite a distinctive shift in arms transfer policy among most major exporters in response to evolving international norms, changes in export practice are slow in coming, as I show in chapter 3.35 States’ underlying arms export preferences have remained relatively stable even as policies have adapted to new norms not for their material benefits but rather for their social reputational gains in the international community.

REPUTATION IN DOMESTIC POLITICS

SCANDAL AND REPUTATIONAL DAMAGE

Multilateral conventional arms transfer policies are typically represented by states’ ministries of foreign affairs, which take a direct interest in their international reputations. Policy implementation, however, is carried out by multiple government agencies and leaves the most politically sensitive cases to top decision makers more responsive to domestic audiences. Yet domestic constituencies are typically uninterested in arms transfers, a complex issue followed only by a small set of specialists, NGOs, and the defense industry. For politicians, arms export controls bring few electoral benefits and restricting defense markets has been seen—rightly or wrongly—as costly to employment and national security. Looking to public pressure to explain changes in export control policy can therefore be difficult. Nevertheless, as some scholars point out, the adoption of international rules into domestic politics is often key to enhancing compliance (Keohane 1998; Koh 1998; Simmons 2009).

Without public interest or legally binding treaties to open up a role for enforcement by domestic courts (Simmons 2009; Smith-Cannoy 2012), domestic strategies to provoke compliance are limited. Whether the ATT (legally binding on state parties) will introduce a genuine source of domestic enforcement remains to be seen; mobilizing the public to push compliance—in the courts or otherwise—tends to be difficult. In this section, I argue that it is primarily with the onset or threat of scandal that governments seek some changes in arms trade practices for domestic political gain—or for salvation.36 Scandals emerge when arms deals are publicly revealed that violate fundamental national values and threaten governments’ reputations at home. When values and norms are expressed in multilateral regimes, violations become easier for domestic actors to identify and spotlight in the public sphere. International law thus can “formally restate social values and norms” (Lutz and Sikkink 2000:657) and legitimate domestic groups’ calls for behavioral change (Simmons 2009). When rules and their violations are clear-cut, civil society can engage in “naming and shaming,” as well as rhetorical entrapment to create a public crisis of reputation (i.e., scandal) for leaders in power.

Scandals work with reputation to generate compliance in two ways. First, severe scandal outbreak can push politicians to improve practice and repair reputational damage. Second, an increased threat of scandal can cause decision makers to choose arms trade partners more carefully in order to avoid scandal. As arms trade transparency measures make more information publicly available, and as civil society actors are willing and able to make use of that information, export decisions become more susceptible to scrutiny. Policy makers, in turn, become more sensitive to scandal and concerned about compliance, at least in extreme cases of clear norm violations. As such, scandals are domestic political phenomena with (depending on the issue) important implications for states’ foreign policy and practice.

A scandal entails public knowledge of “a departure or lapse from the normative standards that guide behavior in public office” (Williams 1998:7).37 It is not “merely” corruption but rather a public revealing of corruption in which a politician, party, or government faces a crisis of reputation.38 Yet an action need not be illegal to bring on scandal. As Suzanne Garment observes, “An act that affronts the moral sensibilities or pretensions of its audience may cause a scandal even if it is in reality no sin” (1992:14). What makes for a scandal thus varies across cultures, societies, and political systems,39 and a government’s and leader’s practices are judged against the shared values of the society of which they are a part. A favorite popular example is the ubiquity of sex scandals in American politics compared to many European publics’ less perturbed reactions to similar reports in their own national politics.

When it comes to the arms trade, major supplier states have varied in their historic susceptibility to scandal due to differences in their relationships with the arms trade, views of the arms trade as a tool of foreign policy, and the interplay of both of these factors with societal values and government structures. Some states appear somewhat more prone to arms trade scandals, such as Belgium, occasionally Germany, and increasingly Great Britain. However, public responses to similar events in other states—for example, France and the United States—have been more subdued. Even so, as governments agree to common export standards linking arms transfers to peace and human rights, the societal values associated with governments’ conduct of the arms trade appear to be converging over time.

Arms trade scandals rarely topple governments or decide elections.40 This is not surprising: voters are unlikely to punish scandalized incumbents in elections, whether because they benefit from the politician’s position of power or because other issues are simply more important to them (Dobratz and Whitfield 1992; Mancuso 1998). Nevertheless, scandals are costly. They boost opposition strength and detract from the government’s domestic legitimacy. Leaders may be perceived as less trustworthy by the public and lose legislative influence.41 Scandals may even set off questions about the exercise of government itself (Bowler and Karp 2004; Mancuso 1998). These consequences stem from tarnished reputations and reduced political capital for those deemed responsible for the government’s irresponsible decisions.42

In democracies, where leaders are subject to the scrutiny of the public and open press, the likelihood of scandals and their detrimental effects escalate in tandem (Markovits and Silverstein 1988; J. Thompson 2000; Williams 1998). As transparency of government practice improves, this dynamic becomes ever more salient. By nature, a scandal occurs when norm-violating government practices come into public view. If there appears to be an upswing in scandals in American politics in recent years, says Paul Apostolidis, “it’s not that politicians are behaving more badly. We’re just learning about it more often” (qtd. in Kleinfield 2008). Transparency measures increase public information about where a country’s arms exports are going and open up its decisions to public opprobrium. If domestic actors are willing and able to spotlight “irresponsible” arms exports in the media, the result may be heightened “scandal sensitivity,” which can pressure governments to choose their trade partners more carefully in order to avoid reputational damage.

Governments’ desire to avoid the reputational fallout of scandal in domestic politics is also motivated by a desire for a positive image. In general, a positive image is maintained by the promotion of conformity to domestic norms and values, whether conformity is real or perceived.43 As Matthew Hirshberg notes, “A positive national self-image is crucial to continued public acquiescence and support for government, and thus to the smooth, on-going functioning of the state” (1993:78). The social control that comes from government legitimacy greatly reduces the costs of governing and, in cases of established democratic regimes in particular, can be essential to it.

In contrast, behavior that deviates from closely held internal definitions of identity and values results in cognitive dissonance (Shannon 2000) and may force a society to confront the relationship between its policies and its actions. In violating deeply rooted conceptions of identity—“we are a good/responsible/ethical member of the international community”—practice that appears irresponsible in the public sphere can lead to scandal. Governments may initially adopt and promote “responsible” arms export standards without much attention from their constituents. However, if governments are caught circumventing or violating those standards, NGOs, media, and the public will be more likely to pay attention. Scandals call public attention to discrepancies between states’ values and identity and their actions. Because governments care about their reputations, the rhetorical entrapment and hypocrisy costs generated by the need to reconcile policy rhetoric and implementation may cause them to comply with policies in which they may have had no interest otherwise (J. Busby 2008; Greenhill 2010; Schimmelfennig 2001).

Scandals therefore have two main effects on compliance. First, when scandals erupt, governments will take highly visible action to counteract negative reports, especially when high-level leaders are directly implicated in the scandal-causing decision. Chong states, “We will defend our reputations vigorously when it is [sic] at risk and be more self-serving when reasonably assured that no one is looking” (1992:187). Second, when the threat of scandal is heightened, governments will act with at least some greater diligence to meet standards dictated by national policy, domestic values, and the international community (Chong 1992). It is, as Oran Young observes, “the prospect of being found out [that] is often just as important, and sometimes more important, to the potential violator than the prospect of becoming the target of more or less severe sanctions of a conventional or material sort” (1992:176–77).

As I show in chapter 5, improvements in arms trade transparency and the presence of active domestic NGOs together can make leaders more sensitive to the possibility of scandals. More information about states’ arms export activities enables cases of noncompliance to be identified. For “naming and shaming” and rhetorical entrapment strategies to work, however, there must not only be information about discrepancies between policy and practice but also actors willing to advertise and condemn those discrepancies (Chong 1992:190). In the post–Cold War era, arms control NGOs—to the surprise of many, including perhaps the NGOs themselves—have emerged prominently in this role.

DOMESTIC NGOS, TRANSPARENCY, AND ACCOUNTABILITY

Changes in international expectations regarding conventional arms export policy have been facilitated—but not necessarily led—by NGOs. As Denise Garcia points out, “the influence of NGOs is more manifest” in the case of landmines than in the case of small arms, where states have been much more integral to the process of norm diffusion (2006:25). Government sponsorship can be crucial for convincing other states to join new initiatives (Koh 1998), and in the case of conventional weapons, big-state leadership especially has been key to growing support among other major suppliers. Even so, as I show in chapter 3, NGOs helped put small arms on the agenda, often in partnership with affected states. NGOs and epistemic communities used technical expertise, field experience, and empirical research to establish connections between problems in the developing world and the spread of small and major conventional arms (D. Garcia 2006). In many countries, NGOs have since then been invited to participate in discussions as consultants and even delegation members.

Partnerships between NGOs and “like-minded states” have become more common, even in the once highly secretive and statist area of conventional arms control.44 Largely as a result of the landmine campaign, officials commonly describe a fundamental shift in their efforts to open up to NGOs (D. Garcia 2006; Hampson and Reid 2003; Malone 2002). Democratic states especially have found political value at home in working closely with civil society actors to signal their public accountability and transparency and to legitimatize their policies. Even in countries where NGO–government links have traditionally been weak, such as France, officials have made efforts in recent years to reach out to NGOs for consultations and information exchanges about conventional arms policy.

While partnering with many states on international policy promotion, NGOs have also sought to maintain sufficient distance to critique government policies and practices.45 Even where international laws and norms are weak, civil society can help serve “the function of much-needed enforcement mechanisms” (Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui 2005:1402). This is where NGOs have perhaps been the most influential on arms export controls. By highlighting specific cases of “irresponsible” arms exports in the media, NGOs publicize the gap between governments’ policy and practice—and, more fundamentally, between their self-image as responsible states and their irresponsible practices. Such influence suggests that shaming may work when states violate fundamental notions of domestic values tied to national identity.46 And because arms trade transparency has improved since the end of the Cold War, with initiatives such as the UN Register of Conventional Arms, the Wassenaar Arrangement on Export Controls for Conventional Arms and Dual-Use Goods and Technologies, the EU Code of Conduct, and national reporting, NGO whistle-blowing has become both easier and more influential.

Robert Keohane observes, “Without transparency, the transnational norm entrepreneurs cannot undertake their key task of exposing the inconsistency between norms accepted within the domestic society (as well as transnationally), on the one hand, and state practice, on the other” (1998:710). As I describe in chapter 3, the movement toward arms trade transparency has occurred alongside an international movement toward transparency more broadly.47 Defined as “the ease with which the public can monitor government behavior with respect to the commitment” in question (Broz 2002:864), transparency has become an expected tool of government and corporate accountability.48 Although transparency norms have evolved separately from new export standards, they have nevertheless helped promote those standards and, in some cases, compliance with them. Nevertheless, simply revealing information does not ensure accountability; the information must also be in a form that is accessible and understandable to the public (Fung et al. 2004). In the case of arms transfers, NGOs often do the legwork to transform hundreds of pages of national reports and registers into information that the media and public can digest.

Transparency enhances a public’s potential knowledge of a government’s wrongdoing and the “clarity of responsibility” in policy making (Powell and Whitten 1993). The threat of publicizing a government’s severe wrongdoings creates an incentive for it to alter its behavior—at least at the margins—to avoid audience costs or bad publicity.49 Transparency thus wields a double-edged sword for governments: democracies especially strive to improve transparency as a signal of good governance (Besley 2006; Best 2005).50 Yet transparency also provides ammunition for NGOs to call governments to task on “bad” arms deals that have the potential to resonate with the media and public. And as more information is available about government practices, the possibility of rhetorical entrapment and scandal becomes greater.

In response to growing transparency and NGO engagement, governments may be motivated to make changes in their behavior in order to avoid or deal with the costs of scandal. Joshua Busby notes, “Advocates can shape the general image and reputation of decision-makers through praise and shame, making them ‘look good’ or ‘look bad’ ” (2007:251). The media, in turn, provide the critical means by which “political and public attention [is focused] on particular incidents” (Tanner 2001:159; see also Apodaca 2007).51 In doing so, the media makes transparency a functional tool of accountability whereby information is disseminated to the public (Besley 2006; Fung, Graham, and Weil 2007). In essence, the media collectivize awareness of scandalous acts in the public sphere (Tanner 2001). “After all,” observes Anthony King, “a scandal by definition is not a scandal until knowledge of it becomes public” (1984:2). NGOs have therefore purposefully engaged in “a new kind of media oriented politics” (Dezalay and Garth 2006:232; see also Simmons 2009) as a means to raise public attention and increase costs to governments for behaving “badly”—that is, contrary to their public commitments.52

In fact, governments contend that the anticipation of NGO criticism spread by the media has been behind their move to better scrutinize and justify arms export decisions. In a parallel example, Mark Duggan and Steven Levitt (2000) find that match rigging in Japanese sumo wrestling drops when media attention increases in anticipation of corruption, in order to avoid future scandal. Scandal even occasionally encourages policy change. NGOs have had a hand in creating and sustaining arms trade scandals in recent years by drawing media attention to flagrant noncompliant behavior in hopes of improving future compliance. States with transparency and active civil society groups are more susceptible to scandal and tarnished reputations that are due to clearly “irresponsible” export decisions. In this manner, NGOs are a direct conduit between reputation and practice in domestic politics, exploiting governments’ interest in avoiding rampant bad press at home. Unlike the alternative explanations outlined next, this perspective avoids depending on a close alignment between commitment and compliance and can explain changing practices in a subset of cases where reputational incentives are strong.

ALTERNATIVE EXPLANATIONS AND THE NEED FOR ANALYTICAL ECLECTICISM

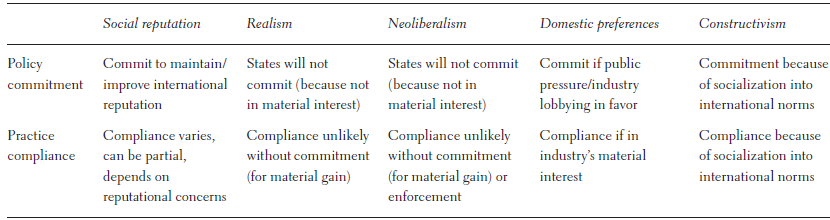

Research explaining major suppliers’ support for “responsible” arms export controls is lacking, but suitable prepackaged explanations are also hard to come by. The alternative explanations outlined here are based primarily on the assumptions and arguments of IR theories and how they conceive of states’ interests in relation to their commitment to international rules and norms. The theoretical expectations for state policy and practice are summarized in table 2.2. Yet standard IR theories often rely on commitment and compliance working hand in hand in their explanations of states’ policy choices. In cases like this one, where commitment and compliance are largely divorced, I argue that these explanations are restricted in their ability to account for states’ behavior.

REALISM: ARMS TRANSFERS AND NATIONAL SECURITY

Major suppliers’ support for new arms export controls presents a challenge for realism. For states to support humanitarian export policies, they must either anticipate net material gains from new controls or see them as simply codifying their existing practice (Downs, Rocke, and Barsoom 1996; Goldsmith and Posner 2005; Morrow 2007). Commitment must therefore come with compliance, so that states can receive the benefits they seek from an agreement or because the agreement happens to reflect what they are already doing. For example, if major exporters support multilateral export controls to improve national security by reducing the need for external intervention (or at least the costs of it), they can accrue these benefits only by stopping supplies to problematic recipients in practice.

TABLE 2.2. SUMMARY OF THEORETICAL EXPECTATIONS

Yet the potential benefits of multilateral export controls are easily trumped by their direct, high costs to state sovereignty and national security, as the historical record shows. In an anarchical international system, states must prioritize basic security needs, in part by avoiding dependence on others (K. Waltz 1979). As long as arms transfers are considered necessary to maintain a viable national defense industry, states will prevent external restrictions for fear of weakening their defense capabilities.53 Any material benefits that might come from new export controls would be significantly outweighed by the costs to states’ security. By restraining exports, “responsible” arms transfer controls might undermine states’ foreign-policy autonomy, their defense industries, and, by extension, their material positions in the international system.54 Overall, humanitarian export policies thus fail to serve state interest, defined by the preservation and enhancement of material power capabilities.55 Confronted by the high costs to material power created by export controls unrelated to national security, commitment to—and certainly compliance with—such policies would be unexpected.

From a realist perspective, then, the states with low export dependence (such as the United States) at least might not oppose new export controls. Similarly, the states most involved in external interventions (again, such as the United States56) might even support them. In addition, supportive policy makers will link humanitarian controls to material power interests and capabilities, whether as a reduction of intervention costs or as backing for the defense industry. It is not that states necessarily lack the moral interests behind humanitarian export controls, but that moral interests are “less tangible, and policy, for better or worse, tends to be made in response to relatively tangible national objectives” (Donnelly 1986:616). Without evidence of coercion from a powerful supporter or a pure “coincidence of interest” (Goldsmith and Posner 2005) to motivate states’ commitment (and compliance), realism may be more useful to identify the puzzle of shared humanitarian export controls rather than to serve as its explanation.

NEOLIBERALISM: ARMS TRANSFERS AND ECONOMIC GAIN

In order to commit to and comply with international regimes, states, from a neoliberal perspective, must derive some mutual economic gain from cooperation (Keohane 1984) or solve a costly collective-action problem (Simmons 1998). In short, self-interested states must deem cooperation to be in their material interest. Without the promise of such benefits, regime formation is difficult to explain. If the material benefits from trading arms outweigh the benefits of restricting arms sales, states will be more likely to oppose a restrictive regime. Supportive states may therefore be those that have already adopted unilateral restrictions and wish to “level the playing field” to their economic advantage (never mind explaining the prior adoption of unilateral standards). Yet if those rare arms exporters with existing national humanitarian standards—such as the United States or Germany—were initially reluctant to agree to similar standards on a larger scale, then the “level playing field” argument loses traction.

Once a regime is established, compliance hinges primarily on states’ desire to receive the resulting benefits now and in the future (Keohane 1984; Simmons 1998) and secondarily on the form of the agreement. Without compliance, the benefits from present-day cooperation—and potential economic payoffs from related future agreements—will not materialize. In this sense, compliance should reflect the material motivations that should be behind states’ willingness to cooperate; compliance should again follow commitment. Some neoliberals nevertheless point out that, absent strong enforcement and monitoring mechanisms, a regime will have trouble inducing compliance (Fortna 2003; Hafner-Burton 2005; Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui 2005). Arms export controls have become institutionalized in most regions, and their numbers are growing internationally. However, because most are not subject to any costly enforcement, their effect on state activity may be minimal.57

DOMESTIC LIBERALISM: DEFENSE INDUSTRY INTERESTS

Liberal theories of domestic interests explore the influence of societal actors as they shape states’ broader interests and preferences (Milner 1997; Moravcsik 1997). The state is not so much an actor in world politics in its own right but rather a “representative institution constantly subject to capture and recapture, construction and reconstruction by coalitions of social actors” and their interests (Moravcsik 1997:518). In some cases—such as the landmine ban—domestic public pressure may drive states’ policy commitments. In the case of arms transfers, many experts’ primary expectation—and the conventional wisdom—is that policies will reflect the powerful, well-funded, and well-networked voice of the arms industry (Hartung 1996; Moravcsik 1992).58 I explore both of these possible explanations—public pressure and defense industry preferences—later in the case studies.

The concept of the military-industrial complex (MIC) encapsulates the close relationship between government and the defense industry and industry’s influence in government decision making.59 Government policies, financial aid for foreign sales, and export decisions commonly reflect industrial interests designed to keep companies in business (Hartung 1996; Moravcsik 1992). According to this perspective, governments should take their policy cues from the defense industry. If industry perceives material benefits from new export controls—perhaps to level the playing field or to pursue profitable coproduction arrangements abroad—it will push policy makers to commit to them. If, however, industry perceives an economic incentive (or even need) to exploit foreign markets to survive, governments will seek less restrictive policies.

The substance and timing of defense industry policies in this case is key: if industry has either ignored the issue or followed the lead of supportive governments, this explanation is less plausible. An alternative societal-level explanation might look to evidence of a groundswell of public pressure on governments to generate policy commitment. Yet I find in the case study chapters ahead that public or industry pressure in advance of states’ commitment decisions is missing. Without such domestic-level pressures, domestic liberalism struggles to explain governments’ policy support. This is not to argue that domestic politics do not play a role. Indeed, as I have argued, domestic politics can prove essential for compliance. It then becomes a question of whether states’ practice simply reflects societal interests according to domestic liberalism or whether it anticipates and reacts to them based on their international commitments for more complex reasons.

CONSTRUCTIVISM: ARMS TRANSFERS AND INTERNATIONAL NORMS

For constructivists, interests are not determined solely by material power or societal demands but are instead constructed through social interactions in domestic and international politics.60 In light of the increasing integration of established international norms of human rights and state responsibility61 into arms trade agreements, states’ interests themselves should come to embrace and internalize these changes. Even in the absence of formal institutions, hard law, or coercive measures, normative obligations established in shared customs should affect not only states’ policy but also their compliance with that policy (Checkel 2001; Finnemore and Toope 2001). Here again, commitment and compliance come together.

Norms create prescriptions for behavior “that predispose states to act in certain ways” (Wendt 1999:234; see also Finnemore 1996a, 1996b).62 Constructivism therefore expects that states’ export policy and practice will reflect new humanitarian standards. For example, Garcia (2011) argues that support for humanitarian arms control policy stems from other-oriented moral progress in international politics that has transformed states’ interests. Precisely to whom these expectations apply, however, divides constructivists. A broad form of constructivism expects norms to shape the behavior of all states in similar ways. Interests are socialized by international institutions and governed by the logic of appropriateness, thus predicting “similar behavior from dissimilar actors because rules and norms may make similar behavioral claims on dissimilar actors” (Finnemore 1996b:30; see also Koh 1998). All states—regardless of regime type, power, or position—should be similarly affected by the spread of arms transfer norms. A more narrow approach (also related to the English School) would limit the influence of norms to a subsystemic group of states with shared values and beliefs (Bull 1977; Klotz 1995). This approach points to democracies as the group of states most likely to be susceptible to human rights norms63 due to a shared community of values, an internal commitment to human rights, and greater openness to societal influence and accountability (Burley 1992; Henkin 1968; Risse-Kappen 1995b; Slaughter 1995).

However, these expectations may be overly optimistic in this case. As Andrew Hurrell points out, the real test of the strength of international rules and norms is their ability to bind states “despite countervailing self-interest” (1993:53). If the empirical evidence reveals gaps between states’ policy and practice or between their public and private policy preferences, states’ normative commitment to new policies must be questioned. Noncompliance that reflects states’ material interests rather than normative obligations would especially call into question constructivist explanations. Of course, it may simply be too early in the “responsible” arms transfer norm life cycle to impose strong expectations on state practice. If states become increasingly compliant over time, it may suggest that norms are becoming accepted and valued for their own sake—though their initial adoption would still have resulted from instrumental, not normative, motivations.64

The chapters ahead explore and explain the policies and practice of top conventional arms exporters. First, historical and statistical patterns of arms trade practice set the stage for a more in-depth analysis of international and domestic material and social pressures to account for major exporters’ dramatic change in arms trade policy. Most of the alternative explanations have difficulty accounting for commitment without compliance, suggesting the need for a more analytically eclectic explanation to understand the policy–practice gap.65 Although scholars often acknowledge the role that mechanisms and motivations associated with both rationalist and constructivist theories can play in determining the decisions of political actors, the task of combining them in practice is often left incomplete. Yet, as I show, it is the combination of normative change, social incentives, and state interest—channeled through concern for social reputation—that can explain states’ commitment to “responsible” arms export policies and their poor (but potentially improving) compliance.

The social reputation argument combines rational and social motivations for states’ policy and practice for a more complete analytical account of state behavior. It views states as rational actors responding to social incentives within a changed international normative environment. Particularly in the context of international institutions, policy expectations can shift and, with them, states’ motivations to support those policies. In the case of conventional arms transfers, states have faced contradictory material and social interests. I argue that their commitment to “responsible” export standards stems from social pressure at the international level. That pressure, however, does not necessarily transform their private preferences.66

Compliance with new standards presents costly trade-offs for states seeking to maintain a viable defense industry and flexible foreign policy. Without international accountability, states may balance these trade-offs by engaging in less-restrictive practices without harming their international reputations. Yet as arms trade transparency improves and civil society activism spreads, democracies especially may face domestic consequences for clear-cut cases of poor compliance and so may choose to reform practice at the margins to avoid negative public attention. In contrast, if states have internalized new norms or seek material benefits from new policies, their practice should more fully reflect those norms and policies. The book next explores historical and statistical trends in conventional arms export policy and practice. It assesses the normative status quo and challenges in creating multilateral policy success in the twentieth century, the sources behind international normative shifts in the 1990s, and the influence of human rights on major exporters’ practice. In doing so, it surveys not only the policy landscape over time but also demonstrates the gap between commitment and compliance, leading to the case studies to explain these findings in greater depth and the need for the social reputational argument.