The future has yet to be made. Our present choices give a new form even to the past so that what it means depends on what we do now.

—Radhakrishnan, former president of India and yoga scholar, 1977

• Distinguish traumatic stress disorders from posttraumatic growth

• Describe the neuroscience of traumatic stress

• Use meditation to self-regulate and calm your nervous system

• Practice yoga postures to build resilience and regain self-confidence

• Create an experience of safety and security wherever you are

• Mindfully observe trauma triggers, emotions, thoughts, and behaviors

• Reconsolidate traumatic memories for lasting change

• Alter trauma patterns

If you have experienced trauma, you have had an experience involving threat of death or serious injury to yourself or someone else. Statistics show that although trauma can have harmful effects, it may also stimulate resilience and toughness, and result in meaningful change. In fact, researchers have found that moderate amounts of adversity can be good for you, enabling you to handle future stressors better (Meichenbaum, 2012). Traumatic stress offers an opportunity to reach a higher level of functioning.

Of course, taking an optimistic view of trauma doesn’t trivialize the horrors you might have endured. Your nervous system went through a shock, and what you experienced was extremely disturbing. Long after traumatic events, your nervous system may remain off balance. And you will likely continue to have disturbing memories and worries that may interfere with your everyday life; however, if you have been working your way through this workbook, you know by now that your nervous system has a great deal of plasticity. In fact, it can be quite resilient. And so, you can intervene! With yoga and mindfulness practices, you can transform your trauma into an opportunity to grow.

Yoga and mindfulness provide you with a clear path to calm your nervous system, cultivate your inner strength, and find inspiration in higher values. By engaging your mind, brain, and body, you will hone your resilience. You will be equipped to rise above your initial negative experience, cope successfully with difficulties that must be endured, and overcome problems that can be changed. The meditations and exercises in this section along with the exercises in the other chapters in Part III help you reclaim your life and forge a healthier, happier you!

Jessica had a warm, sheltered upbringing in a small town in a nearby state. She had a bubbly personality and was sometimes accused of being a “ditz” as she told us, but she didn’t care because she was just having too much fun at college. One day she was walking back to her college campus dorm room along the path from the local town. Her mind was miles away. She had taken a short break from exam week studying to do a little shopping. Her backpack was filled with the fortifying snacks she bought for her friends in the dorm. Her attention was brought back to her walk when she heard a rustling in the woods up ahead. She thought, “Oh, that’s nothing” and kept walking. Then she saw a dark, shadowy figure far up ahead, but dismissed its significance as she continued on her way. Suddenly, a disheveled, heavyset man jumped out from the woods, right in front of her. She had a fearful thought about it, but then dismissed her concern with a trusting thought, “Oh, these things don’t happen here.” Suddenly he was right next to her, reaching out to grab her arm. She froze, thinking, “This can’t be happening to me!” As he threw her roughly to the ground, she tried to scream, but it was too late.

Jessica quit school and moved back home, unable to do anything. She saw danger lurking all around her and was afraid to even leave the house. She felt depressed and angry, and often took her anger out on herself. She couldn’t stop remembering the horror of the experience and blamed herself for being an unsuspecting fool in such a scary world. Her trust had become mistrust; her confidence had been replaced by fear and anger.

Yoga and mindfulness were key elements in Jessica’s therapy. She practiced a yoga strength routine given in this chapter several times a week to build up physically. She learned mindfulness, bringing her attention to the present moment, to deepen her awareness and put her in touch with the safety of her parents’ home where she was currently living. Gradually she regained trust in others and in herself. She became more grounded in what she was doing in the present, actual world. She gradually developed confidence that she would recognize and face a threat if it ever happened again, without expecting threat from every dark shadow. Because of this work, her memories were altered. She reconsolidated her shattering traumatic experience into a new, more confident perspective: Though she had lost her innocence, she reclaimed it, through transforming the meaning of her trauma. She used her experience by volunteering as a counselor to help others who had been through trauma. She told us, “I feel somehow vindicated when I realize that my experience, awful though it was, allowed me to be able to help someone else.” Eventually, she returned to college and earned a degree in psychology. When we talked to her some months later, she had started a job working professionally at a trauma center, where she could apply what she learned to help others.

We have an unconscious system that helps us to detect a threat to our safety, a brain-body response at the level of the nervous system known as neuroception (Porges, 2011). Several brain systems with a link to cognition and emotions are involved. When facing a perceived threat, your amygdala sends messages to your endocrine system as part of the stress pathway that links the hypothalamus, pituitary, and adrenal glands together. Please review Chapter 11, pages 84-85, where we described the details of the fear/stress pathway. Thus, this pathway is not only activated by an immediate threat but is also triggered by memories of the traumatic event. This arises because the hippocampus, where memories are stored, is closely linked to the amygdala. The proximity and interaction of these brain areas helps to explain how you keep remembering the threat even though it occurred in the past.

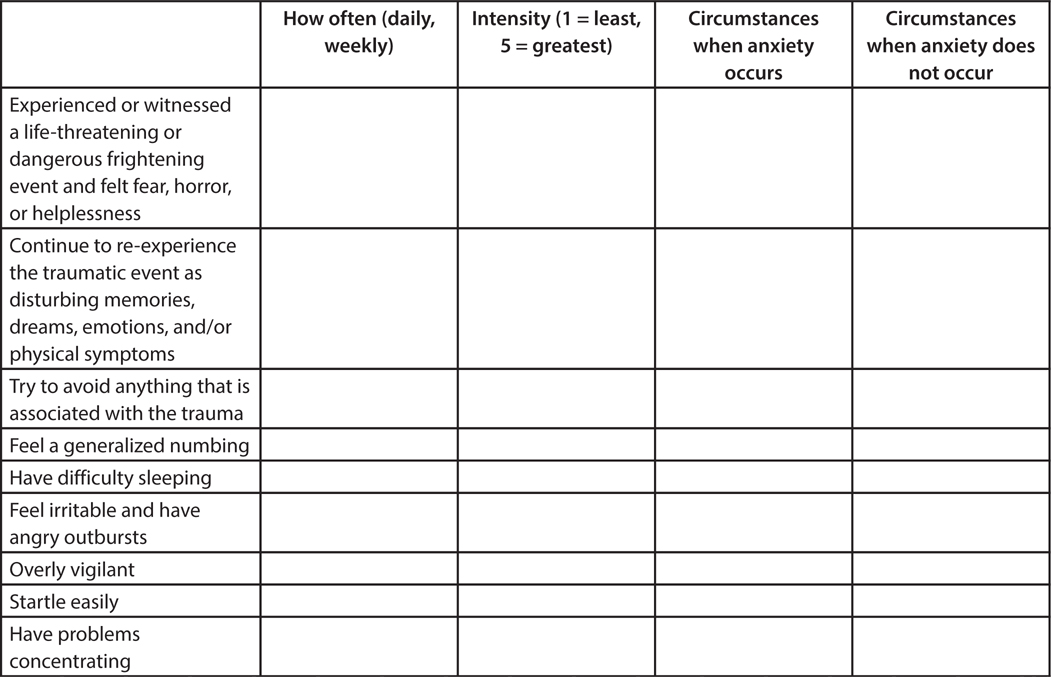

There are three main categories of trauma disorders, each with known causes and characteristic reactions. The disorder checklists can help you to categorize the kind of trauma you have experienced. A growth chart is also provided to help you reroute your experience into something transformative.

If you had a single traumatic event, such as one resulting from a car accident or a damaging storm, but have otherwise led a normal life, you have what is called an ASD. ASD sufferers tend to get over the trauma in several months, especially with meditation and brief psychotherapy.

PTSD has become one of the most pervasive problems in modern times. When trauma recurs, such as from a war, rape, or a serious one-time trauma, the diagnosis will be PTSD. Recovery often takes longer than ASD. The most extreme form of PTSD derives from horrific events, such as when active-duty soldiers face death and mutilations, women endure multiple rapes, or children grow up in war-torn areas. These kinds of severe trauma usually require long-term treatment.

DTD occurs if you have been raised with continual abuse, lacked a supportive environment or grown up in a war-torn area. If you have a diagnosis of DTD, you should find a good therapist who can provide you with support over time. We recommend someone who is sympathetic to yoga and mindfulness or hypnosis, since these methods have been shown to be especially helpful for traumatic stress problems. Part of helpful therapy involves guidance in how to develop healthy psychological and physical habits, which you may not have acquired as a child.

FIGURE 13.1 ASD, PTSD, and DTD Checklist

PTG is the change people undergo from the struggles they endure when meeting an extremely challenging situation. Surprisingly, some people who endure a trauma eventually become more flexible, stronger, and more resilient. Following the challenges of trauma, you can be transformed and strengthened. The growth does not occur from the trauma, but from how you deal with it.

Even if you have not experienced all of the indicators of PTG, we encourage you to fill out this checklist again after you have worked through the chapter. Give yourself some time, and you will find more to check off!

Fill out this checklist now, and then fill it out again after you have read this chapter (see Figure 13.10).

FIGURE 13.2 Posttraumatic Growth Checklist

You have inherent inner strength. If you are a soldier, you have probably had experiences of being strong and capable. And even those not in the military probably did not feel helpless, fearful, or lacking in confidence before the traumatic event. Yoga poses can build your feeling of strength and confidence bottom up, as you take a strong body posture. The key point of the therapeutic application of these postures is to feel strength and extend it confidently. Pushing your body posture is not the goal. Instead, be comfortable as you use these postures to build and express your power!

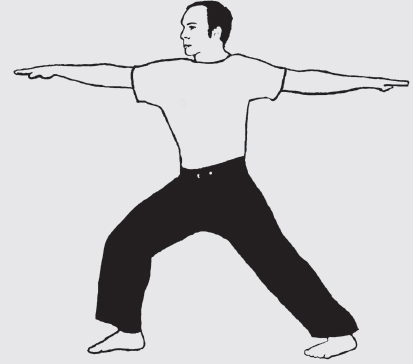

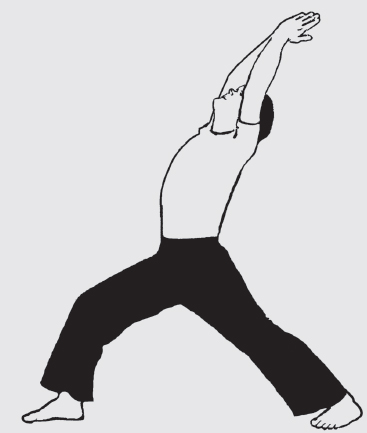

The warrior sequence is symbolic of taking a strong stand, and you will feel your natural capacity to be a strong person as you embody the warrior series. Move slowly in and out of each position, keeping your motions smooth. Hold each position as long as you can, breathing in and out, and then move slowly into the next position.

FIGURE 6.18 Warrior 1

Perform the first warrior pose in this sequence as described in Chapter 6, in the exercise “Taking a Confident Stance in the Warrior Pose” on page 54.

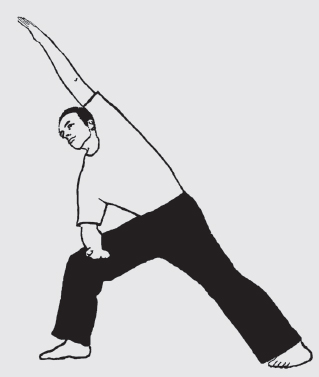

FIGURE 13.3 Warrior 2

Face your chest and torso toward the right so that your whole body faces squarely right. You may let your back foot pivot diagonally to take the strain off your knees. Raise your arms straight over your head with palms facing forward and arch your back gently with the inhale. Hold for several seconds as you breathe comfortably in and out several times. Then lower your arms back to the first warrior position as you exhale.

FIGURE 13.4 Warrior 3

Exhale as you lean to the right, resting the elbow of your right arm on your right knee. Extend your left hand overhead and toward the right as you lean your upper body to the right. Feel a stretch through your right arm, waist, and left leg. Repeat all three positions on the other side. Perform the entire sequence twice.

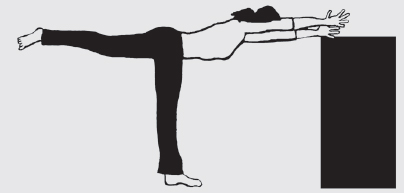

Your feeling of self-support comes from your legs. The expression “To stand on your own two feet” means to be self-sufficient and capable of handling your life. When you are physically stronger, you will find it easier to stand up to the challenges you face. The T-pose will strengthen your legs and back, while toning your abdominal areas. It also strengthens your knees. And as a balance asana, it will enhance your concentration. All of these qualities will increase your resilience and confidence.

Begin doing this exercise with the support of a counter or wall. Stand upright, about three feet away from your support. Raise your arms up overhead and inhale. Bring one leg up behind you as you lower your upper body parallel with the floor. Let your extended hands rest on the support. Your body will be in the shape of a T. Look at one spot on the floor as you keep your neck straight. Sense where your balance point is. If you feel steady enough, lift your hands slightly away from the support, to balance on your own. Breathe in and out as you hold this position as long as you can comfortably.

FIGURE 13.5 T-Pose 1

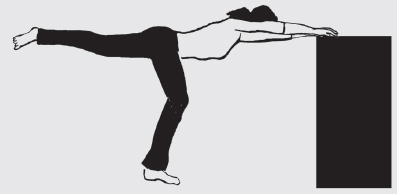

Next, bend your supporting knee as you maintain the position with your hands extended in front. Don’t perform the knee-bending part of this exercise if you have knee problems. But if your knees feel comfortable, keep your arms parallel to the floor and hold with your leading knee bent, and then straighten again. When you feel ready, return to the mountain pose (standing upright). Continue to stand in the mountain pose for a moment or two, then rest. Once you feel adequately rested, repeat on the other side.

FIGURE 13.6 T-Pose 2

Adding strength is not just a matter of discipline or building muscle. It also requires a strengthening of the spirit. Yoga draws from the spirit of animals to bring out the practitioner’s inner strength. Each animal has a different spirit to draw from. For example, stretching like a cat adds flexibility and resiliency. The cobra’s coiling ability can be translated into making your spine stronger and more flexible. And you can draw from a lion’s ferocity to raise your vitality and develop the stronger side of your nature. Perform the lion pose with power and intensity. This pose helps to tone your facial muscles and releases emotional tension. Following the exercise your face and neck areas will feel more relaxed.

The lion is performed in the pelvic pose, in a kneeling position. If sitting on the floor is uncomfortable, you can do this posture from a chair. Place your hands on your knees and inhale completely. Then exhale sharply as you learn forward. At the same time, tense and separate your fingers, tense the muscles in your face and neck, open your eyes and mouth wide, and stick out your tongue. Hold for approximately 15 seconds and then slowly withdraw your tongue; relax your eyes, face, and neck; relax your fingers; and settle back into the pelvic posture. Repeat several times. Between sets, relax your muscles and breathe gently.

FIGURE 13.7 Lion

You can create your own sense of safety using yoga postures and meditation. These practices develop a calm center that can bring out a sense of being secure from within. Without dependence on anything outside of your own resources, you may find refuge in the following meditative moment.

Certain yoga postures can enhance your ability to regulate your own emotions, by calming your nervous system and quieting your mind. The child pose is a posture for self-soothing with a special comforting quality. It provides a feeling of self-support that can be reassuring especially when you are feeling unsafe and insecure. Here are several variations.

Sit on your feet in the kneeling pelvic pose (see Figure 6.15). Bend forward slowly until your cheek touches the floor. Allow your arms to rest comfortably at your sides with your elbows bent so that they can relax on the floor (see Figure 6.19 Child Pose). For a variation, rest your forehead on the floor as you extend your arms out in front of your head, for another experience of self-support, as your arms cradle around your head. You may need to shift or move slightly to find the most comfortable position. Breathe calmly and rest in this position. If you have trouble sitting on the floor, try the child pose while sitting on a chair at a table. Lay your head facedown on the table. Place your arms next to your head on either side. Breathe comfortably for several minutes. You will feel protected and supported in all of these soothing child poses.

FIGURE 13.8 Child Pose 2

Meditation can help create a sense of comfort and security. Practice this visualization regularly to initiate a change in your sense of safety.

Think of a time when you felt calm and comfortable. Usually people think of a tranquil place in nature, but you might also have a memory of being in a room that you enjoyed or with loved ones. Recall that place, and how you felt when you were there or imagine how you would feel if you went there. What do you see and hear? Sense the aromas in the air, the feeling of a breeze and sun on your skin. Vividly picture yourself there. Draw on your own experiences from the past or even a fictional place from a book or movie. Visualize a sanctuary and go there to rest.

Sanctuary is always possible in the here and now moment of mindful presence. You can carry peace of mind with you always and anywhere.

Sit quietly in meditation. Let all your sensations settle. Breathe comfortably, in and out, allowing your breathing rate to be relaxed and calm. Now clear your mind of all thoughts. As soon as a new thought appears, let it go and meditate in the present moment. Keep working on letting your stream of consciousness be clear of any thought outside of this quiet moment. Now, sitting quietly, there is no worry, fear, or stress. Everything is serene and peaceful. Here is true sanctuary, always available if you simply make the effort to recognize that it is there.

The root chakra (see Figure 5.4) is located at the base of the spine, where your body rests when you are sitting cross-legged on the floor or on a chair. This chakra represents security and support. Focusing on this area will nurture feelings of safety from your own internal core.

Sit comfortably on the ground outside, cross-legged in the easy pose. (If sitting on the ground is uncomfortable, perform this meditation sitting in a comfortable chair.) Close your eyes and focus your attention on the root chakra, at the base of your spine. Visualize the color red, spreading out from your base, bringing strength and stability with each breath in and out. Feel your connection to the ground where you sit (or feel the support from the chair). Draw from its strength and stability. Visualize each breath in, flowing down to your root, connecting you to the stability of the ground, and then flowing out again as you exhale, relaxed and calm. Enjoy this moment, grounded in the present, stable, strong, and capable, arising now from your own root.

Trauma is stored in your memory. In general, memory has two main systems:

1. Explicit memory is conscious and engages in recalling your daily experiences, known as episodic memory. It works through your prefrontal cortex—the thinking brain and the hippocampus—where memories are stored.

2. Implicit memory is unconscious and emotional. These memories are amygdala centered and are not immediately accessible to conscious awareness.

Traumatic memories are often stored as implicit memories. They are not easy to change. When you experience a trauma, the overwhelming intensity of experiencing triggers a rush of neurotransmitters that activate the HPA pathway. This blocks your explicit memory system, leading to amnesia of the event itself, preventing you from remembering exactly what happened; however, since the traumatic event is processed through the emotional limbic system as well, it is stored as an unconscious, implicit memory. So a simple cue, even remotely related, could elicit a flood of patterned reactions, entrenching the traumatic memory in your brain.

You can initiate a change in your typical trauma pattern and literally rewire your brain so that the reaction will no longer be the same. The next series of exercises takes you through a process of (1) becoming mindfully aware of the pattern and (2) changing the pattern in several ways so that you reconsolidate the memory in a new, less disturbing way.

Your trauma pattern has four key elements:

1. Triggers

2. Emotional responses

3. Corresponding thoughts

4. Typical behaviors

Begin by mindfully observing each of these elements, and you will shift your traumatic memory from being implicit and unconscious, leading to a reaction that is out of control, to becoming explicit, conscious, and manageable, putting you in the driver’s seat of your reaction and back in control.

We have seen with our clients who have been through trauma that some learn to know exactly what triggers a reaction, and others don’t. For example, soldiers often learn that any loud noise will elicit their reaction, but a woman who was molested as a child may not be able to pinpoint her triggers.

Practice mindfulness in the moment when your reaction is triggered. Stop and pay attention to what you are experiencing as it happens. At first, you may not think to practice until after your reaction has already been triggered, but whenever you start, this process will prove helpful. In time you will become aware more quickly, so don’t be discouraged. Remember to suspend judgment, observe, and trust that mindful awareness will be helpful.

As soon as you react, notice your emotions. What do you feel? Observe your sensations (such as your heart beating, palms sweating, or stomach tightening) and your feelings (for example, panic, frightened, or angry) and any other experiences you might be having. Try to assess the intensity of your reactions, and whether your experience alters as time passes. Once again, even if they are somewhat uncomfortable, stay calm, at a manageable distance, with the qualities of the experience as best you can. With your mindful eye, you can watch the dark clouds of your experiences flow past, with their distinct patterns changing moment by moment. In so doing, this will help you to feel a little less threatened, as you see clear skies on the horizon. Trust the process because you are developing helpful abilities that will alter the effects of your traumatic experience.

Now observe the thought patterns that arise. Notice just what you are saying to yourself when you have the emotional reaction. You may be telling yourself negative, scary things. If you perceive negativity, watch how your thinking unfolds. Do your thoughts become increasingly negative? Do you get into an internal argument? Do your thoughts repeat or are you thinking a long, escalating series of thoughts? If you find yourself carried away by a particular stream of thought at some point, climb back on shore as soon as you can and resume observing objectively.

Now turn your attention to your behavior. What do you typically do when you start feeling and thinking that way? Do you withdraw and keep to yourself? Or perhaps you explode with anger? Or maybe you find yourself crying? How does your body respond? Perhaps it tightens up, or just feels fatigued? As always, observe your typical behaviors nonjudgmentally.

At a time when you are not feeling disturbed, take a few mindful moments to sit quietly in the comfort of your home, out in nature, or even in the therapy office. Allow your breathing to be comfortable and let yourself relax. Mindfully observe the sensations, thoughts, and feelings you have as you are safely sitting there. Enjoy the security and comfort for several minutes.

Now, allow yourself to think briefly about the traumatic pattern that you worked with in the previous four exercises. Remind yourself that you are in a different place physically and mentally. You are re-examining the memory now in the safety of your own home or therapist’s office.

Remain as calm as you can in the present moment, and notice the details, but with a difference. Breathe and deliberately relax as you let yourself ponder the reality that nothing dangerous was really happening when your reaction was last triggered.

If your emotions begin to rise, counter them with a reassurance that you are okay as you sit centered in this quiet moment. You might find your feelings escalate, and if so, look around you and pay attention to where you are now, to allow yourself to become comfortable again.

When you are calm once more, observe your thought patterns during this reaction. Perhaps you are telling yourself how awful it was, how unfair it was, how disturbed you were, or some other “uh-oh” type of thought. Notice how these thoughts fuel your emotions. Try to recall that, no matter how terrible it was, you survived. The horrible time has passed.

The experience you have while meditating brings a sense of how you are the master of your life. You may not be able to control contingency, but you can control how you interpret it. You can be ever more at peace, even when you have experienced a traumatic event, by cultivating acceptance meditatively.

Meditate on breathing for a few minutes, noticing each breath, in and out. Your breathing finds its own natural rhythm. All you have to do is allow it to happen. Many things are like this. When you have the flu, you can drink extra water and get sufficient rest, but ultimately, nature takes its course and your body eventually heals. This is also true of trauma. If you take care of your physical and psychological health, your brain-mind-body system will find its natural balance again. Nature will take its course. Can you think of other examples of how the mind-brain-body system restores balance of itself? As you sit in meditation, accept that this natural healing process can help you now. Trust that you can return to normal when the time is right, allowing your recovery process to take the time it needs. Our brains are capable of growing and developing as needed. Have confidence in the process.

Adopt a mindful nonjudgmental attitude whenever you find yourself revving up your reactions by telling yourself how bad it was and how terrible you feel. Keep working on letting these evaluations go. Although the event might have been terrible, your negative judgments will not reduce the effects. Instead, bring yourself into the present moment and focus on your present experience. Keep working on questioning any negative evaluations. When you can accept what is, you open the way to changing your trauma pattern so that it will no longer trouble you.

You have initiated a healing process. By regularly calming your emotions, letting go of negative thinking, and accepting yourself, you will begin to feel more at ease in the world.

Changing a long-standing pattern takes repeated practice. You are reversing what may have become an entrenched pattern, and it may take time to shift the balance and feel the effects. Journaling and charting can help you sustain the process.

Witnessing evil or death transforms you. By touching the depths, you reach the heights. You can now steer your life by following an enlightened compass and remaining attuned to what is truly important and meaningful for you.

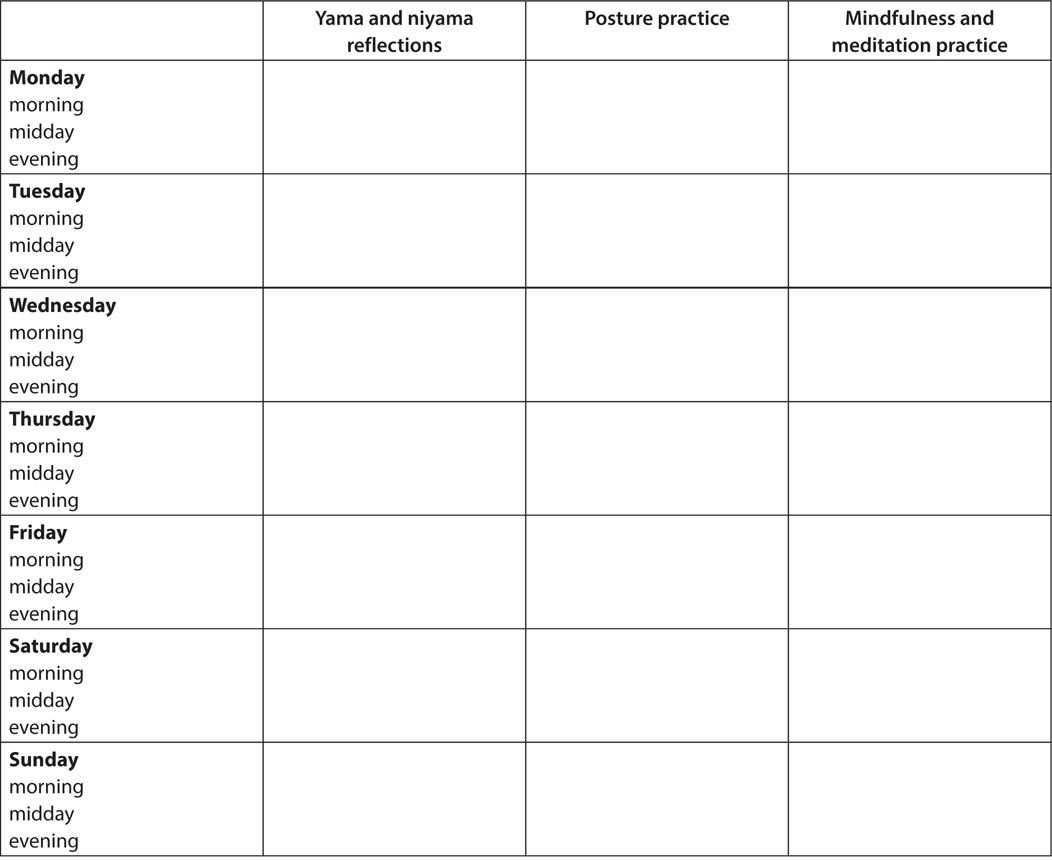

Read through the yamas and niyamas again, and reflect on each one, finding inspiration to help you guide your life in a better direction.

1. Can you seek higher values?

2. Would you like to take a new direction for work or relationships?

3. Are you interested in helping others?

4. Having suffered, do you have greater compassion for other people’s suffering?

5. List the ways you would like to fulfill your potential.

FIGURE 13.9 Charting Your Practice

Fill out this chart again after you have gone through the chapter. Continue to return to it from time to time to observe tangible changes you are making. You may have other qualities to add to this list. Please feel free to make your own creative discoveries!