Cesar works with Paul Diaz and Junior. (photo credit 3.1)

I always work from my instincts—the gift I believe gives me my understanding of dogs in the first place—but I’ve also been able to add a lot of new tools to my tool kit. Dogs are my teachers, but in the past few years, in my travels around the world since I started my TV show in 2004, I’ve met some interesting human teachers as well, some of them the top names in their field. Among these animal and dog experts—veterinarians, trainers, academics who study animal behavior or learning theory—some have disagreed strongly with me, many have challenged me, but all have influenced my growth, as a man and as a dog professional. Some of them have generously contributed their experience and wisdom to this book, and I hope my own insights and experiences have helped a few of them as well.

There are dozens of theories and ideas about how to train dogs. One saying in the field is that if you ask any two trainers to agree on one thing, the only thing they’ll find they have in common is the belief that a third trainer is doing it all wrong. In doing my research for this book, however, I haven’t found this to be entirely true. Though there is plenty of disagreement and occasionally even ugly infighting, many of the best trainers are open to sharing information and ideas with one another. It’s clear that these trainers are in it for the dogs, not their own egos. I would never criticize another professional because I like to remain open to what that person might have to teach me. And I like to think the best of people, because when I do I find that they often rise to meet my expectations.

Most trainers agree that dog training methods can be broken down in a few general ways. The first division is between techniques based on learning theories and techniques based on natural dog behavior. I am a very new student of learning theories, so my techniques are all pretty much based on hands-on experience and the dog behavior I’ve observed throughout my lifetime. Then there are the different “schools” of dog training, which some people break down simplistically into “traditional” (punishment-based), “positive” (rewards-based), and “balanced” (incorporating elements from both schools).

The truth is that things aren’t quite so simple. A look at the history of dog training will show that techniques and styles of training haven’t always evolved in a straight line.

SOME LANDMARKS IN THE HISTORY OF DOG TRAINING

THE STONE AGE (CIRCA 8000 B.C.) Dogs live side by side with humans, helping in hunting and drafting and providing warmth. They begin to genetically evolve the ability to read human cues as they become domesticated. At the same time, human interdependence with dogs may be changing the course of human evolution. “For instance, a hunting dog that could smell prey reduced the need for humans to have an acute sense of smell for that purpose. Human groups that learned to train and work with dogs had a selective advantage against human groups that did not do so. So just as humans have exerted selective pressures in dog evolution, it seems highly likely that dogs have caused selective pressures in human evolution.”1

CIRCA 3500–3000 B.C. Drawings of dogs with collars appear on the walls of pre-dynastic Egypt.

CIRCA 2600–2100 B.C. In the Egyptian Old Kingdom, murals, collars, and stelae let archaeologists in on the names of favorite dogs, such as Brave One, Reliable, Good Herdsman, North-Wind, Antelope, and even Useless. Other names come from the color of dogs, such as Blacky, while still other dogs are given numbers for names, such as “the Fifth.”

CIRCA 350 B.C. Alexander the Great raises Peritas—either a mastiff or a greyhound-type dog—from puppyhood and takes him along as a companion on all his campaigns. When the king is ambushed by Persia’s Darius III, Peritas allegedly leaps up and bites the lip of a charging elephant, saving Alexander’s life and empire. Legend has it that Alexander was so devastated when Peritas died that he went on to erect numerous monuments to Peritas’s bravery, even naming a city after him.2

CIRCA 127–116 B.C. Marcus Varro, a Roman farmer, records tips on training and raising puppies for herding. This and other written evidence indicate that even the Romans understood the value of early training.

55 B.C. Roman armies conquer Europe accompanied by their “Drovers’ Dogs,” probably ancestors of the modern mastiff and rottweiler. These dogs perform guarding and herding duties for the military and their camp followers.

CIRCA A.D. 700 Ancient Chinese dog breeders and trainers enjoy great status and respect, owing to the advances they have made in the miniaturization of dogs and development of the early toy breeds. Chinese toys, originally bred merely to be companions and foot-warmers, are kept inside the palaces, and their ownership is restricted to members of the royal family.

THE 1500S From royalty on down through the classes, the popularity of dogs as companions, not just hunters and herders, begins to take off across Europe. Dogs perform functions as varied as going into battle with full suits of armor to walking on a primitive treadmill to turn a spit for cooking.

THE 1700S Truffle hunters learn to give their dogs bread as reinforcement when they locate truffles. This technique turns out to be cheaper than using pigs, which cannot be stopped from eating all the truffles they locate.

1788 The first training facility for Seeing Eye dogs is established at the Quinze-Vingts hospital for the blind in Paris, France.

1865 British general W. N. Hutchinson publishes Dog Breaking: The Most Expeditious, Certain and Easy Method, Whether Great Excellence or Only Mediocrity Be Required, dealing primarily with the training of hunting dogs such as pointers and setters. Despite the title, the author advocates an early form of positive training: “[The] brutal usage of a fine high couraged dog [by] Men who had a strong arm and a hard heart to punish—but no temper and no head to instruct [has] made my blood boil.” Hutchinson adds, “It is hard to imagine what it would be impossible to teach a dog, did the attainment of the required accomplishment sufficiently recompense the instructor’s trouble.”3

1868 Sir Dudley Majorbanks, First Baron Tweedmouth of Scotland, sets out to create the “ultimate hunting dog”—a companion and retriever. He begins a breeding line that will produce America’s best-loved dog—the golden retriever.

1882 S. P. Hammond, a writer for Forest and Stream magazine, advocates in his columns and in a book entitled Practical Training that dogs be praised and rewarded with meat when they do something right.

1880S Montague Stevens, a famous bear hunter and friend of Theodore Roosevelt and the sculptor Frederic Remington, trains his New Mexico bear dogs by rewarding them with pieces of bread instead of beating and kicking them, as others of this era are generally doing.

1899 The first canine school for police dogs is started in Ghent, Belgium, using Belgian shepherds, which have recently been established as a breed.

1901 The Germans begin Schutzhund work, a competition devoted to obedience, protection, tracking, and attack work.

1903 Ivan Pavlov publishes the results of his experiments with dogs and digestion, noting that animals can be trained to have a physical, eating-related response to various nonfood stimuli. Pavlov calls this learning process “conditioning.” In 1904 he will be awarded the Nobel Prize for his research.

1907 Police begin patrolling New York City and South Orange, New Jersey, with Belgian shepherds and Irish wolfhounds.

1910 In Germany, Colonel Konrad Most publishes Dog Training: A Manual and thus by default becomes the father of “traditional” dog training. Relying heavily on leash corrections and punishment, Most’s methods will still be used in many police and military training settings one hundred years later. Ironically, Most’s theories are based on the same operant conditioning principles that will later create clicker training.

1911 Edward Thorndike writes a book discussing his “law of effect” theory of learning based on stimulus and response. Thorndike shows that “practice makes perfect” and that animals, if reinforced with positive rewards, can learn quickly. His studies on rewards and consequences will influence Harvard’s B. F. Skinner in his development of behaviorism.4

1915 Baltimore police begin using Airedales from England to patrol the streets. The use of Airedales will be suspended in 1917 after the dogs prove unhelpful in making arrests. The police will fail to notice, however, that no robberies occur where the dogs are on patrol.

• Englishman Edwin Richardson wants to revive the Greek and Roman generals’ practice of using dogs in wartime. Apparently a very spiritual man—Richardson describes the “soul” of a dog and its “sixth sense” when someone it loves is dying—he has trained dogs, mostly collies, Airedales, and retrievers, for the military during World War I. His methods incorporate games and some other forms of positive reinforcement, and the dogs prove to be quick studies. Many dogs are used during the war for communication and for guard duty.

1917 The Germans begin to use dogs to guide soldiers who have been blinded in mustard gas attacks. The French soon follow suit.

1918 U.S. Army corporal Lee Duncan finds an abandoned war dog station in Lorraine, France, with five puppies in a kennel. Duncan takes one of the pups and names him Rin Tin Tin after the finger dolls that French children give to the soldiers. The dog travels to California, proves easily trainable, and is soon employed making movies so successful that the Warner Brothers studio is saved from bankruptcy. The dog will die in 1932 in the arms of his neighbor Jean Harlow and will be buried in Paris. His descendants will work in the movies throughout the 1950s, inspiring many people to try to train their own dogs to do simple tricks.

1925 One of the very first German-trained guide dogs for the blind is given to Helen Keller.

1929 Dorothy Harrison Eustis establishes the American Seeing Eye Foundation to train guide dogs for the blind.

1930 About four hundred dogs are employed as actors in Hollywood, the majority of them mongrel terriers, which have proven to be small enough for indoor scenes, rugged enough for outdoor scenes, and exceedingly smart.

1933 The American Kennel Club obedience competitions are designed by Helen Whitehouse Walker, who wants to prove that her standard poodles are more than just pretty faces.

1938 Harvard’s B. F. Skinner publishes The Behavior of Organisms, based on his research into operant conditioning as a scientifically based learning model for animals and humans. His special focus is on teaching pigeons and rats.

1940 The Motion Picture Association of America (under the Hays Office Production Code) gives the American Humane Association the legal right to oversee the treatment of animals in films, motivated by public outrage over the 1939 movie Jesse James, in which a horse is ridden off a cliff to its death.

1942 The U.S. military says it needs 125,000 dogs for the war and asks people to donate their large breeds. The military manages to train only 19,000 dogs between 1942 and 1945. The Germans reportedly have 200,000 dogs in service.

1943 Marian Breland and her husband, Keller Breland, form a company called Animal Behavior Enterprises (ABE) to teach animals for shows. The Brelands have been students of B. F. Skinner and have begun teaching animals to perform tricks for shows and for commercial clients, such as the dog-food maker General Mills. They will pioneer the use of a “clicker” to teach animals at a distance and to improve timing for affirmations and delayed rewards. The Brelands will also be the first people in the world to train dolphins and birds using Skinner’s principles of applied operant conditioning.

• The movie Lassie Comes Home is filmed. It features a purebred male collie playing the female starring role. The dogs are trained by Rudd Weatherwax and his son Robert, soon to become Hollywood’s first “celebrity” trainers.

1946 William R. Koehler becomes the chief animal trainer for Walt Disney Studios, where he will remain for more than twenty-one years. A former U.S. Army K-9 Corps instructor, Koehler has published a top-selling series of training guides, developed effective programs to train receptive dogs, and devised ways to correct problem animals that would have otherwise been destroyed. He will popularize the use of choke chains, throw chains, long lines, and light lines. Though Koehler’s correction-based methods would later be frequently criticized as unnecessarily harsh and forceful, his methods would become the mainstay of dog training from the 1950s to the 1970s.

1947 The Brelands begin using chickens as training models because they are cheap, they are readily available, and “you can’t choke a chicken” (or you’ll just teach it to run away).

1953 Austrian scientist Konrad Lorenz publishes Man Meets Dog and King Solomon’s Ring, books that popularize animal behaviorism.

1954 Blanche Saunders, author of The Complete Book of Dog Obedience, travels the country to spread the gospel of pet obedience training. She believes that food should not be used as a primary reinforcer (or “bribe,” as she calls it) and advocates praise and head pats as better ways to communicate a job well done.

1956 Baltimore reestablishes its police dog program, which remains the oldest police K-9 program in the country to the present day.

LATE 1950S TO 1960S Frank Inn, an assistant to Rudd Weatherwax in training the original Lassie, goes out on his own and adopts a shelter mutt named Higgins. While wheelchair-bound from an injury, Inn must train Higgins using only his voice, treats, and positive reinforcement. Higgins will soon be cast as the world-famous Benji.

1960S Marian and Keller Breland are hired by the U.S. Navy and meet Bob Bailey, the Navy’s first director of training for its Marine Mammal Program. They will begin a partnership with him, and after Keller Breland dies in 1965, Marian and Bob Bailey will be married in 1976.

1962 William Koehler publishes The Koehler Method of Dog Training, which will become a staple of AKC obedience competitors and the most popular dog training book in history. Koehler’s techniques include the liberal use of praise for good behavior and the important concept of “proofing” a dog—making training effective by ensuring that it takes place in all sorts of different places and under different conditions. He and his son, Dick Koehler, will use their methods to save many last-chance dogs from being euthanized. Despite Koehler’s controversial reputation among modern-day trainers, some of his techniques remain the core of many effective dog training systems still in use.5

1965 Dr. John Paul Scott and Dr. John Fuller publish Genetics and the Social Behavior of the Dog, which some still consider the definitive study of dog behavior. Among many other things, the book identifies the critical periods in the social and learning development of puppies.

1966 The U.S. Supreme Court dissolves the Motion Picture Association’s Hays Office Production Code on First Amendment grounds. A side effect will be the American Humane Association’s loss of the legal right to monitor animal action on movie sets.

1970S The U.S. Customs Service begins to use dogs to detect drugs; dogs will soon also be employed to sniff out explosives and fire-starting chemicals.

1975 American veterinarian (and hunting dog breeder) Leon F. Whitney publishes Dog Psychology: The Basis of Dog Training. It integrates research from Scott and Fuller and other data to posit that understanding how dogs see the world is integral to their successful training. (Whitney will later die a controversial figure for his involvement in the modern eugenics movement.)

1978 Barbara Woodhouse publishes No Bad Dogs, one of the first wildly popular books on basic dog training. It relies heavily on the walk and the proper use of a choke chain. Woodhouse says that most “bad dogs” have inexperienced owners who are not training their dogs properly by being consistent, firm, and clear. This book and her British television show will make her the first international celebrity dog trainer.

• The Monks of New Skete, elite breeders and trainers of German shepherd dogs in Cambridge, New York, publish How to Be Your Dog’s Best Friend: A Training Manual for Dog Owners, which sells more than 500,000 copies. They advocate the philosophy that “understanding is the key to communication and compassion with your dog, whether it is a new puppy or an old companion,” and employ a method that combines “traditional” training with positive reinforcement techniques. In later years, the compassionate monks will be dismissed as too harsh by some critics.

1980 The intentional explosion of a horse on the set of the movie Heaven’s Gate enrages a group of crew members and actors. They successfully demand that the Screen Actors Guild include in their contracts with producers a provision to protect animal actors and to reinstate the American Humane Association’s legal right to oversee the treatment of animals on movie sets.

1980S Veterinarian and animal behaviorist Ian Dunbar is dismayed to discover that most trainers won’t work with puppies until they are six months old, long after their most teachable development period has passed. He pioneers off-leash training for puppies and begins writing books and giving seminars on the advantages of off-leash, reward-based training, not just for pros but for the average pet owner as well.

1984 The U.S. Department of Agriculture begins to use beagles to patrol airports for contraband food and other perishable items.

1985 Dolphin trainer Karen Pryor publishes Don’t Shoot the Dog! The New Art of Teaching and Training, which focuses on timing, positive reinforcements, and shaping behavior. Building on her successful work with marine mammals, she reintroduces the concept of distance training—through whistles and clickers—as an advancement of the Brelands’ (see 1943 and 1960s) earlier efforts.

1987 Phoenix-based trainer and behaviorist Gary Wilkes combines Pavlovian conditioning and operant conditioning with a deep knowledge of instinctive dog behavior, gleaned from years working in shelters with tens of thousands of dogs. The result is Click and Treat Training—the first fusion of reinforcement and punishment in the context of instinctive dog behavior designed for pet owners.

1990 Veterinarian Bruce Fogle publishes The Dog’s Mind: Understanding Your Dog’s Behavior, which stresses understanding a dog’s biology and psychology in order to communicate well with him.

1992 Gary Wilkes and Karen Pryor team up to teach behavior analysts and dog trainers what will soon be dubbed “clicker training” by an anonymous trainer on the Internet. Rather than a revision of former methods, clicker training includes extensive use of targeting for practical dog applications, such as heeling, directed movements, and object identification/scent detection. This original “clicker training” method also included some aversive control.

2001 Within hours of the September 11 attack at New York’s World Trade Center, specially trained rescue dogs are on the scene, including German shepherds, Labs, and even a few little dachshunds. Tragically, they make no live finds.

2000S AND BEYOND A slew of cable television shows feature various dog training and rehabilitation methods. The notion that there are “new” and “old” dog training methods obscures the fact that all dog training methods involve some form of operant conditioning, which is in fact pretty old stuff (as old as dogs).6

In researching this book, my co-author and I are grateful to have had help from several different trainers from divergent backgrounds. Surprisingly, we didn’t find as many working professionals who were religiously loyal to one camp or another as we did people who told us they preferred not to be categorized. Instead, they liked to draw from the best and most effective elements of every method available, as well as create original solutions of their own.

Kirk Turner, a professional dog behaviorist who is now a trainer for the Pine Street Foundation cancer-sniffing dogs project, has evolved his own method of working over the span of a twenty-year career. “Because I have the background in pretty much all the different kinds of training, I can make stuff up as I go along. I feel that each dog is different. On my business card, it says that I have a balanced approach. I don’t like to use the word only. And I don’t like to use the word never. And I don’t like to use the word always.”

Barbara De Groodt owns From the Heart Animal Behavior Counseling and Dog Training in Salinas, California, and considers herself a positive behavior-based trainer. “All these methods have a place. Positive has just gotten to the place where everybody says, ‘Oh, if you’re a positive trainer, you’re a cookie pusher.’ No, it doesn’t mean that; it can be praise, playing ball, going for a walk. Any life reward can be used by a positive trainer.”

Bonnie Brown-Cali has trained dogs since 1989. She volunteered for CARDA (California Rescue Dogs Association), sheriffs’ departments, and the Office of Emergency Service in California training and deploying dogs in urban and wilderness searches for missing persons as well as for human remains. She is an independent contractor for Paws With a Cause, training dogs for people with disabilities, and for Working Dogs for Conservation, which trains dogs to look for exotic or endangered species. She does all of this plus her “bread and butter” job as an obedience trainer.

With such a wide spectrum of experience, Bonnie is a member of both the IACP—which advocates balanced methods that include leash corrections—and the APDT, which supports positive, rewards-based training methods. “I like to be a member of various organizations to keep my mind open. But my philosophy always stays the same: bring out the best in a dog by using the training techniques that are appropriate to the dog’s temperament and the ultimate training goals.” She prefers clickers and other reward-based operant conditioning methods to train her service dogs, but she warns against relying on this method for an antisocial dog.

My co-author tells me that on occasion someone will say to her, “I don’t approve of Cesar’s training methods.” When she tells the person that what I’m doing isn’t dog training but dog rehabilitation, he or she often grudgingly admits to having watched only one or two episodes of the show or a one-minute clip on YouTube and typically has not read any of my books or seen my videos. When my co-author asks, “What do you think his methods are?” the answer invariably is something like, “Oh, all the choke chains and the e-collars and the alpha rolls.”

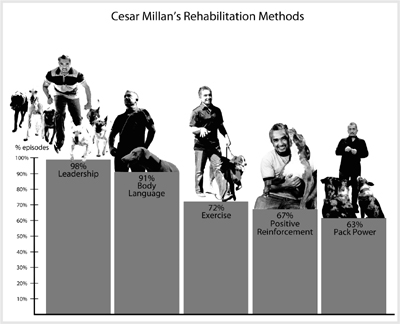

Well, any regular viewer of Dog Whisperer knows that these tools don’t fairly represent what such a critic would call “my methods.” Curious about this, our producers did a show-by-show breakdown, watching hundreds of hours of television and counting when a particular technique was used in any given episode. At the time the breakdown was done, we’d filmed 140 shows, covering over 317 separate cases of problem dog behavior.

Here are the results:

The person who doesn’t approve of my “methods” might be surprised to learn that the number one thing I advocate nearly every show is simply leadership (in 98 percent of the episodes), which I teach as the calm-assertive energy that any leader, teacher, parent, or other positive authority figure projects to her followers. I’ve used the word dominance to describe the energy of leadership, but in the animal world dominance doesn’t mean “brutality,” and assertive certainly doesn’t mean “aggressive.” I believe that good leadership never involves bullying or intimidating; instead, it depends on confidence, knowing what you want, and sending clear, consistent messages about what you want.

The number two method I advocate, according to the producers’ breakdown, is body language (91 percent), which is a primary way in which leadership is projected in most animal species. My third top “method” is exercise—walk your dog properly at least twice a day (72 percent). And what is the fourth most common “method” I’ve used on Dog Whisperer episodes?

This one may shock a few people. I used positive reinforcement in one form or another 67 percent of the time in the first 140 shows. As Barbara De Groodt reminds us, positive reinforcement doesn’t have to mean cookies. It can mean anything that a dog likes and that becomes a motivator or reward for the dog.

Personally, I don’t think I have a specific “method” or “system” that I apply in order to change or improve a dog’s behavior. For me, there is no magic formula. I believe in trusting my instincts and in treating each dog as an individual. Most important, I base my philosophy on this core principle—in order for a dog to be your best friend, you must first be his. If you want an obedient and well-behaved dog, you must fulfill that dog’s needs before asking him to fulfill your own.

Cesar’s Rules FOR BASIC FULFILLMENT

One of the things I learned from my grandfather is to always work with Mother Nature and never against her. The truth is that all behavior modification—and by definition all training techniques—originated in one way or another with how animals learn to survive in nature.

“An animal is an animal is an animal,” says Bob Bailey. You’ll recognize Bob’s name from the short history of dog training presented earlier because he is truly one of the pioneers. A very youthful seventy-something gentleman, Bob still jets all over the world teaching both individuals and governments the most effective ways to work with animals, and he has trained everything from slugs to raccoons to killer whales. Because of his more than sixty years of hands-on experience with animals, as well as his extensive scientific background and training, my co-author approached Bob for an interview for this book. Though he did not know me personally and had heard decidedly mixed reviews about my show and my work, he graciously agreed to play the role of neutral teacher and historian when it came to explaining some of the history and science of operant conditioning. Bob Bailey is a genuine class act as well as a man who is truly passionate about and committed to the subject of his life’s work—animals.

“When I say an animal is an animal, now, that doesn’t mean that I don’t recognize evolutionary situations. Yes, a slug is really very different from a killer whale. But nature has been working on these animals for two billion years. And it really hasn’t treated the slug any differently than it treated the killer whale. It’s totally neutral on this. And the evolutionary process has been the same on all of them, and reinforcement, by and large, generally works the same for all of them, as does punishment. Animals tend to avoid things that are punishing and to go towards things that are not punishing or that they find favorable.”

When I first came to the United States, or even when I started working with dogs, I had no idea what the term operant conditioning meant. To my inexperienced ears, it sounded like something that had to be very complicated and intimidating, something you had to have a PhD to understand. Imagine my surprise when I learned that, when you boil it down, operant conditioning—a term coined by psychologist B. F. Skinner in the mid-1930s—is the science of learning from consequences. This is something animals themselves have been doing without our help since the dawn of time! Animals will do things that produce good consequences, and they will stop doing things that produce bad consequences. Many of you will recognize the “Skinner Box” from your high school or college basic biology courses. B. F. Skinner invented a laboratory-based mechanical-training machine that rewarded animals with food when they pressed levers or pecked at a lighted key. This was how Skinner used the scientific method to analyze and quantify exactly the way a rewards-based training system works.

Operant conditioning is such a key principle of animal behavior that it is a mainstay of human psychology as well. I asked my friend Dr. Alice Clearman Fusco, a psychologist and college professor, to break the concept down for me the way she would for one of her first-year students. “In a nutshell, with operant conditioning the dog is ‘operating’ in the world—he’s doing something—and there is a consequence,” Alice explained. “On the other hand, there is classical conditioning, which occurs when the dog isn’t doing anything and an event occurs in his environment that causes him to make a connection between things.”

We’ve all heard about “Pavlov’s dog.” What Pavlov did was ring a bell and put meat powder in a dog’s mouth. The dog soon associated the bell with food. Very soon the dog would salivate when he heard the bell—not normal behavior. That’s classical conditioning at work. Many of the dogs on my show who have developed what seem to be irrational fears or phobias have actually been classically conditioned to have that fear. For instance, the ATF agent Gavin had been classically conditioned to his fear of loud noises. Gavin wasn’t thinking about the past, and he certainly wasn’t rationalizing; he just knew that a loud noise was a really bad, dangerous experience and his safest response was to shut down. I would describe Gavin as having a canine form of post-traumatic stress disorder that first began when he was around fireworks and thunder on the Fourth of July. Humans can develop the same condition in a similar way. “Most of the research I’ve seen on PTSD regarding conditioning has mentioned classical conditioning as a current theory,” says Dr. Clearman.7

In operant conditioning, while an animal is doing something—engaging in a behavior—something good or bad happens. This gives the lesson that the behavior is desired or not desired. I have spent my life watching dogs interact with one another and with their environments. Operant conditioning is the way nature’s own classroom works. If a dog pokes his nose at a porcupine, he is operantly conditioned (punished) by the quills. If he turns over a trash can and finds a half-eaten cheeseburger, he is operantly conditioned (rewarded) by the food.

Many people don’t realize how easy it is to unintentionally use operant conditioning in their daily lives—and to end up with a dog doing the exact opposite of what they want it to do. “I always tell my clients, whether you intentionally or unintentionally do it, you are always reinforcing particular behaviors,” says Barbara De Groodt. “Even if it’s behavior you don’t like, it’s probably because you have unintentionally reinforced it. The classic example is the dog running to the door barking and the owner running behind it yelling, ‘Shut up, shut up, shut up!’ The dog sees it as the whole pack running to the door barking and thinks, ‘Oh, this is great!’ ”

With operant conditioning, there is positive and negative punishment and positive and negative reinforcement. Punishment reduces behaviors and reinforcement increases them.

Note that the terms positive and negative are only about adding or subtracting. They have nothing to do with something being nice or not nice.

“I’m not a positive-only trainer,” Kirk Turner told me. Kirk uses the “clicker method” in training and obedience classes. The clicker method, which will be covered in depth later in the chapter, is often touted as being a positive-only training method. “I believe in relationships, and relationships are not always positive,” he said. “You can try.” Kirk likes to let the consequences come from the environment so they are not associated with a human and seem natural. “I’ve been with wild animals in Africa and they certainly provide consequences, and those aren’t so pretty sometimes.”

Kirk’s training philosophy tends to lean toward reward versus punishment whenever possible, which is one reason he finds the clicker to be a useful tool. His metaphor of a relationship comes into play here. “Relationships with humans and dogs are emotionally based,” he told me. “When I’m using operant conditioning I remove all my emotions except for when the dog offers the behavior that I’m looking for.” So Kirk has turned the “consequence” by which the dog learns into a reward by not reacting to the dog. “When the behavior has happened and I can mark that thought then I will use that emotional attachment to let the dog know that’s what I’m looking for. It’s part of the reward.”

Here’s a table that those who study animal behavior often refer to as the “quadrant” of +P/–P or +R/–R.

| Punishment | Reinforcement | |

| Positive | ADDING something not desired or wanted. Quills are “added” to the dog’s nose when he sniffs too closely at a porcupine. | ADDING something desired or wanted. Treats, massage, praise, play, throwing a ball for a dog to chase—all of this is positive reinforcement. |

| Negative | SUBTRACTING something desired or wanted. If a dog is food-aggressive, claiming the food as yours is negative punishment. | SUBTRACTING something not desired or wanted. The dog comes to you and you pull the quills out—taking the pain away.8 |

It’s important to know these definitions when we are talking about reinforcement and punishment. Sometimes I am criticized for using punishment when I rehabilitate a dog, but in nature, punishment is a part of everyday life. That is one of the reasons I tend to use the term correction—because I learned that in America people get very upset at just hearing the word punishment and assign all sorts of horrible meanings to it. Of course, as Bob Bailey reminds my co-author, using the word correction is just a pretty synonym for the scientific concept of punishment.

“The scientific definition of punishment, by the way,” says Ian Dunbar, veterinarian, animal behaviorist, and a science-based dog trainer from whom we will hear a lot more later in this book, “is that it decreases the immediately preceding behavior such that it is less likely to occur in the future. That’s it, period. It says nothing about punishments being scary or painful. However, by definition punishment must be effective in reducing unwanted behavior; otherwise, it’s not punishment. Let’s put it this way. Behavior is changed by consequences. Consequences are good or bad. From the dog’s point of view, either things get better or things get worse. You can teach the dog to do a lot by encouraging him to get it right and by rewarding him for getting it right. Setting him up so he can’t fail, luring him and rewarding him for getting it right. But you will not get reliability unless you punish the dog when he gets it wrong. Now, this is the biggest thing in dog training that people don’t understand. Everybody makes the assumption that punishment has to be aversive. And the reason for this is, the hundreds of thousands of learning theory experiments that were done years ago were all performed by computers, training rats and pigeons in a laboratory cage. Well, how can a computer reward a rat? Simple, right? It goes click and out comes a treat from a little food dispenser. How can a computer punish a rat? It can’t go, ‘Ha-hem, excuse me, rat, hello, I don’t like what you’re doing.’ So, you know, electric shock. So the point was that in the laboratory where learning theory was created, punishments were always aversive. They always caused pain. However, when people train people or when people train dogs, we realize that of course punishment doesn’t have to be painful or scary.”

Webster’s dictionary defines aversive as “tending to avoid or causing avoidance of a noxious or punishing stimulus.” Noxious means something that causes harm or pain. So when we ask how we can stop unwanted behavior, what we really want to ask is: How can we do it without causing pain or fear? Ian Dunbar proposes a new quadrant to address this. “If on one side you put ‘Is this thing I’m doing punishing, i.e., does it reduce or eliminate the undesirable behavior? Yes or no.’ And ‘Is this thing aversive? Yes or no.’ Meaning, is it painful? Is it scary? We find that two of these quadrants are overflowing: ‘non-aversive, nonpunishments’ and ‘aversive nonpunishments,’ whereas the other two are virtually empty: ‘aversive punishments’ and ‘non-aversive punishments.’ ”

Many of the things dog owners do to get their dogs to obey may be non-aversive, but they are also nonpunishing, which means that they don’t get the behavior to change. “For example, nagging,” says Ian. “Someone says, ‘Oh, don’t do that, Rover. Rover, please, will you sit down. Rover, Rover, Rover! Sit down!’ And then they give up when the dog doesn’t do it. So this wasn’t aversive, but it didn’t change the behavior and so wasn’t a punishment. The dog thinks it’s a riot. The bichon says, ‘I love it when she talks to me that way.’

“On the other hand,” Ian continues, “people are frequently aversive without effectively reducing unwanted behavior, and so this isn’t punishment either. People all too frequently jerk the leash, shout at the dog, and shock it, but you know what? They’re still doing it next week. The dog doesn’t learn, and therefore by definition the aversive stimuli were not punishments either.”

Ian Dunbar describes all this in scientific terms, but I would explain it in a slightly different way. The fact is that no animal ever responds positively to angry, frustrated, or fearful energy. If you are trying to correct your dog and you are not in a calm-assertive state, your dog will react to your unstable emotions and be unable to understand what you want to communicate to him. At the same time, if you are nagging your dog and being ineffective, not only is your energy just nasty, negative, and unhelpful, but you are probably not 100 percent committed to changing your dog’s behavior either.

“The use of aversive punishment is actually quite rare,” Ian says. “When a trainer who’s using his voice, using a leash correction, or maybe even using an electronic collar does it correctly, you only see the trainer use it once or twice. Then they don’t need it anymore because now the dog never runs away. Once, twice with the collar, and he never chases sheep again. Aversive punishment only needs to be used once or twice. However, this is not what you see most of the time. Instead, what we see is people who have the dog on-leash, and they’re jerking at it all the time, they never stop shouting, and they never take the shock collar off. This is not punishment. Depending on the severity, it is either harassment or abuse.

“The quadrant that’s virtually empty,” Ian continues, “is non-aversive punishment. In reality, though, it’s surprisingly easy and extremely effective to eliminate undesirable behavior with softly spoken instructive reprimands.”

Ian Dunbar very successfully teaches people to use voice commands as effective non-aversive punishments, a method he describes in detail in Chapter 6. By this definition, I would describe the way I use body language, energy, and sound (such as “Tssst!” or “Hey!”) as also being forms of non-aversive punishments. I might add the use of touch to this category if it is firm, not harsh, and does not cause pain, although there are those who definitely disagree with me here. I happen to believe that physical touch is an important part of the way dogs “talk” to one another. Touch is the very first sense that a dog develops.9 My observation is that dogs use firm touch—not violent or aggressive touch, but assertive touch—with one another as a follow-through to a warning given by eye contact or body language and energy, and that to speak their language, it helps if I use it too. If the touch is neither severe nor done in anger or frustration—for example, an insistent touch on your friend’s shoulder to get her attention in a dark movie theater—then, to my mind, it is simply a method of communication, not an “aversive” punishment. Of course, the removal of something a dog likes is also a form of non-aversive punishment (technically, negative punishment)—such as the withholding of attention, a reward, or a favorite activity or claiming a space or an object that a dog likes.

The rule of thumb in operant conditioning is that positive reinforcement, not punishment, is not only the most humane but also the most effective way to create or shape any type of new behavior.

“I have never had to use punishment to ever get a behavior. Never. I mean, that’s a zero,” states Bob Bailey emphatically. “I have used punishment to suppress behavior that I didn’t want. But only in circumstances where it would be high-risk behavior or somebody’s going to get hurt or the dog is going to get hurt or it’s really going to cause damage to property or something like that. Instead of punishment, I have tried to modify the environment in such a way that the animal can’t do bad things. And by proper reinforcement, I’ve gotten the behavior I want, and I’ve made the game worthwhile enough for the dog to play the game. In that way, the punishment issue just didn’t come up.

“If I am going to use a punisher,” Bob continues, “I am going to use a punisher that I am absolutely sure is going to stop the behavior dead. If you have to use a punisher any more than roughly three times to stop the behavior, you’re not doing it right.”

The bottom line is that aversive punishment isn’t something to mess around with. It should work right away or you shouldn’t do it. If you are pulling or poking at your dog more than once or twice and she isn’t getting the message, then you can’t blame the dog. You need to stop and completely rethink your strategy, not to mention your own state of mind, which, in my experience, is most often the heart of the problem.

Where does this leave leash pops or side pulls? There are those who are totally opposed to them, and I respect that. But many trainers do employ them. I use them and teach owners to use them correctly, but I want them to be a means to an end, not something that goes on all the time, every day, for the rest of your dog’s life. When properly used, the leash pop—which administers a physical sensation that is not meant to hurt or “jerk” but instead to get a dog’s attention—communicates to the dog that something he is doing needs to be changed. If timed exactly with the unwanted behavior, and if the correct solution (what you want the dog to do instead) is offered concurrently with the correction, popping the leash can be a teaching tool, not a lifelong crutch to use in order to “nag” your dog into good manners.

It wasn’t really B. F. Skinner who “invented” the modern art of rewards-based animal training. It was his two young graduate assistants, Marian and Keller Breland. Bob Bailey kindly gave my co-author and me a copy of his educational video Patient Like the Chipmunks, which chronicles the history of Skinner-based operant conditioning and the fascinating story of Animal Behavior Enterprises, which was founded by the Brelands in 1943. Back then, Bob recounts, Marian and Keller weren’t even sure there was a living to be made training animals. But they were certain they knew how to do it. Using operant conditioning methods, the Brelands first discovered the concept of “shaping.” Instead of waiting all day for an animal to perform a behavior and then “capturing” it with a reward, they began rewarding the animal for every small step it took toward the desired action—kind of like that party game Hot and Cold that we used to play as kids. Eventually, the animal would hit the jackpot and perform exactly the behavior the trainers had been looking for.

Their next big discovery came in 1945. “While shaping tricks, the Brelands noticed that the animals themselves seemed to be paying attention to the noises made by the hand-held food-reward switches,” writes Patrick Burns, a trainer of working Jack Russell terriers, in Dogs Today magazine. “Keller and Marian Breland soon discovered that an acoustic secondary enforcer, such as a click or whistle, could communicate to an animal the precise action being rewarded, and it could do so from a distance.”10

The Brelands called this a bridging stimulus, which their colleague Bob Bailey shortened to the term bridge when he was director of training for the U.S. Navy’s Marine Mammal Program. That bridge was usually a clicker or a whistle. In this way, the Brelands and Bailey actually practiced an early form of clicker training long before it was popularized by dolphin trainer Karen Pryor in the late ’80s and early ’90s.

“All the clicker does is tell the animal that it’s done what you want it to do correctly and there will be a primary reinforcer coming, which is food or a toy. But you have to make it worthwhile for the animal,” Bob Bailey explained to my co-author. “That’s one of the things that I try to get across to people. It has to be worthwhile for the animal to play our silly little game. Whatever the silly little game is, to the animal it’s nothing that it probably would have done if the animal were living two million years ago out in the bush. It wouldn’t be sitting in front of somebody or retrieving a little toy for a kid or something like that. It would be out earning a living. But the animal got secondary reinforcers back then too. When it did something, something happened, and as a result it ended up with food, and so it would change its behavior to do that more often and solve problems that way. So it was really nature that used the bridge first. The rest of us, we’re all Johnny-come-latelies.”

Over the next thirty years, the Brelands and Bailey taught hundreds of animals to perform in everything from corporate demonstrations to theme park shows to commercials, television shows, and movies. They also trained other animal trainers who went on to work at such venues as Busch Gardens, Disney World, and Sea World. Animal Behavior Enterprises contracted with major amusement parks such as Marineland of Florida, Marineland of the Pacific, Parrot Jungle, and Six Flags.

The ABE training sessions were never more than twenty minutes at a time—usually less, says Bob—and took place one to three times a day, depending on how much time the company had to produce a finished animal show. Timing and the rate of reinforcement were the secrets of ABE’s success. Interestingly, the vast majority of times Bob and his team didn’t end up actually working with the animals they trained. They’d get hired to do a show, produce the show, and train the animal actors so that anyone could work with them.

“Our trainers changed animals about every two to six weeks depending on what they happened to be working with. They would be rotating all the time so that the animal worked for many people, as long as they followed the same protocol. All of our trainers trained exactly the same way. We had one method of training, and it evolved over time. If somebody came up with a better way of doing it, then by Jove, we’re going to use that new way, but they had to prove that it was indeed a better way.”

Bob explained to us that he believes trainers who are truly dedicated to their craft are guided as much by philosophy as by procedure, and his personal philosophy is to choose reward over punishment whenever possible. “I believe the least intrusive procedure needed to get a behavior or to stop a behavior is best for the trainer and for the animal; a belief which does not preclude my using whatever punishment or force necessary to stop dangerous behavior. I think trainers philosophically oriented toward ‘correction,’ or other punishment euphemisms, can default under stress to coercive procedures which, in my view, often create more problems than they solve.”

“I don’t believe much in ideology,” Bob added. “If I found an ethical method faster than behavior analysis or operant conditioning, if someone sent me an e-mail that opened a new door, I would drop what I’m doing and never look back. I’m not wedded to an ideology. It’s the science. It’s the technology.”

Since the early ’90s, the clicker has become one of the most popular tools in dog training circles. I’ve never used a clicker because I always perceived it as more of a training tool for building new behaviors than a tool for rehabilitation. In doing research for this book, however, I’ve witnessed people do incredibly creative things with this very simple tool. It has been used for everything from teaching simple obedience to behavior modification to training working dogs in specific tasks to training dogs to detect cancer in human breath, which you’ll read about in Chapter 8. Many of the professionals we interviewed for this book were enthusiastic about the clicker’s many uses.

Kirk Turner has been training dogs professionally for more than twenty years and came to the clicker out of a desire to not use physical force on animals. He took the time to explain why he prefers to use this versatile tool. “I like it because basically you’re expanding the dog’s mind,” he said. “You’re making the dog actually think in a positive way without putting any negatives in the situation. He has to think about what it is that’s actually going to get him some kind of reward.

“The thing to understand about the clicker is it means three things,” Kirk explained. “It means ‘That’s what I’m looking for, right there’; it means the reward is on the way; and the click means end of the exercise.” The clicker also works great from a distance. “I do recall exercises with families,” Kirk explained. “I have them all stand around in a circle. I point at one person in the family and tell them, ‘Do anything you can to get the dog to you.’ ” The rest of the family has to ignore the dog completely. Kirk stands on the outside of the circle and operates the clicker. This way, when the dog goes to the person who is calling him, the behavior is marked immediately from a remote distance.

Clickers can also be used to phase out food for dogs that are food-centric. “Once you’ve trained the behavior, you want to go into an intermittent reward system so that you’re not rewarding them every single time,” Kirk said. First he rewards the dog with a treat every time it performs the desired behavior, then he will ask the dog for the correct behavior three times before he will give a treat, and then maybe seven times. “Over a period of days, I can really lessen those rewards and eventually not do any kind of reward at all.”

“A clicker is a wonderful tool for shaping behaviors for obedience, tricks, scent discrimination, and service dog tasks,” Bonnie Brown-Cali shares. “I teach a dog that a click means food is on the way. Once a dog understands this, then I can use a click to train behaviors. The timing of the click is critical, as it tells the dog that the last behavior performed is going to be rewarded. For instance, if I have a dog that is showing aversion to a scent that I want to train on, I can use the click to change the dog’s perspective. Now this scent means something good. From there, I can shape an alert for the dog to perform when he locates the scent. If the dog already knows the command ‘sit,’ I can tell the dog to sit at the scent and then click when the behavior is performed. Since the click means that food is on the way, I can click from a distance to tell the dog that what he did is correct, and the reward is coming. Then, once the behavior is shaped, the command ‘sit’ and the clicker are phased out.”

“I’m not a clicker trainer per se,” says behavior-based trainer Barbara De Groodt. “I use them for some fast-moving dogs and for some people who have disabilities and want to teach a service dog to do something. I also use the clicker for people who are way over the top with their praise or corrections. I can bring them to sort of a normal level, instead of the person who goes, ‘Great dog!’ all the time. The clicker brings them into a more normal range. The clicker doesn’t have emotion and always has the same consistent meaning.”

As Barbara points out, too much praise or excitement can often block your dog from learning what you are trying to teach him. I always recommend calm-assertive energy. In his informative and sometimes controversial blog Terrierman’s Daily Dose, writer Patrick Burns makes the argument that clickers work for so many people because they help to create a calm-assertive state of mind and body that paves the way for clear communication.

“When Millan talks about being ‘calm and assertive,’ what he is really talking about is making fewer signals and making clearer ones,” Burns writes. “Let’s look at clicker training. What does a clicker do when put in the hands of a new wanna-be trainer? When a trainer has a clicker in hand, and is focused on getting the noise timed exactly right, is the trainer flailing around with his or her hands? No. Is he or she talking? No. In fact, they are not supposed to be moving at all. And in clicker training, it is the clicker that does the talking, not the human. Is the clicker assertive? You bet! The clicker sends just ONE clear signal—a signal that says ‘We could use a little more of that.’ ”11

Some trainers we interviewed found the clicker to be a little too constricting in their efforts to shape a dog’s behavior. “I rarely use clickers anymore,” says Joel Silverman, who started out as a clicker-based marine mammal trainer at Sea World and transitioned into dogs as the host of Good Dog U on Animal Planet. “People who think clickers can solve every behavior problem in every situation are fooling themselves. You take a high–prey aggression dog that wants nothing more than to go after somebody, and I’m telling you, treats and clickers and cookies and kisses are not going to do it.”

Mark Harden is a thirty-year veteran of professional training, having worked with nearly every variety of animal there is for movies and television. “I don’t use clickers with dogs. I hate them for dogs. Now, I’m a clicker wizard with cats, monkeys, birds, parrots, anything like that. The clicker works so well with cats, for example, because they’re not as focused on me. They’re more about the food. They want food and ritual. They’re not reading my face. Maybe one in a hundred cats actually looks at my face. When they do, it really creeps me out.”

In working with dogs, however, Mark feels that the clicker can block the flow of trainer-animal communication. “The clicker is a waste of a perfectly good hand. I mean, when I work, maybe I’ve got a look stick in one hand, I’ve got a bait bag, and I’m trying to get food. I’m trying to time my pay. My theory is that the dogs I’m working with are very in tune with me. Dogs have a way of reading my face. My vocals. My body language. They read everything about me. So to me, the clicker becomes this sort of anonymous noise that I have to teach them to understand. And I can do everything and more with my voice. Personally, I find that most people don’t use the clicker correctly, and then it screws up your timing like crazy.”

“The Brelands pioneered the use of the secondary reinforcer as a methodology,” Bob Bailey reminds us, “but now this notion of the clicker kind of caught on, and I’m afraid there’s a lot of people who have decided that there is magic in a clicker. Of course, that’s just not true.”

It was the Brelands themselves who first began to realize that the science of operant conditioning had some built-in drawbacks that would need to be overcome and understood for their animal training business to flourish. In fact, those drawbacks came from Mother Nature herself. In a 1961 paper entitled “The Misbehavior of Organisms,” Keller and Marian Breland described their first experience with the failure of reward-based operant conditioning:

It seems that when working with pigs, chickens and raccoons, the animals would often learn a trick and then begin to drift away from the learned behavior and towards more instinctive, unreinforced, foraging actions.12

Calling this syndrome “instinctive drift,” the two researchers were shocked to discover it because it went against all the laws of 1950s-era positive reinforcement theory. The Brelands had been basing their previous work on what they thought was a hard-and-fast rule—that behaviors followed by food reinforcement should be strengthened, while behaviors that prevent food reinforcement should be eliminated. But some animals dared break these rules when their instincts reared their ancient heads. The Brelands discovered that some instinctive behaviors can even hold a hungry animal back from choosing food reinforcement!

“The Brelands did not overstate the problem, nor did they quantify it,” writes Patrick Burns. “They simply stated a fact: instinct existed, and sometimes it bubbled up and over-rode trained behaviors.”

In their landmark paper, the Brelands took the first step toward incorporating the concepts of the animal ethologists—scientists who study animals in their natural environments—into their operant conditioning and training work, which made their methods even more effective. They turned out to be light-years ahead of their mentor, B. F. Skinner, in this regard. “He taught that all you needed to study was behavior,” writes Temple Grandin in Animals in Translation. “You weren’t supposed to speculate about what was inside a person’s or an animal’s head … you couldn’t talk about it. You could measure only behavior, therefore you could study only behavior.”

The now-famous Grandin was just a college student back in the 1960s, when B. F. Skinner was God and the science of behaviorism was Gospel. “Behaviorists thought these basic concepts explained everything about animals, who were basically just stimulus-response machines. It’s probably hard for people to imagine the power this idea had back then. It was almost a religion.”

When Grandin finally got the chance to visit her idol at his office at Harvard, they had a very revealing conversation. “I finally said to him, ‘Dr. Skinner, if we could just learn how the brain works,’ ” Grandin chronicles. “He said, ‘We don’t need to learn about the brain, we have operant conditioning.’ I remember driving back to school going over this in my mind, and finally saying to myself, ‘I don’t think I believe that.’ ”13

As it turns out, the Brelands didn’t believe it anymore either. They wrote:

After 14 years of continuous conditioning and observation of thousands of animals, it is our reluctant conclusion that the behavior of any species cannot be adequately understood, predicted, or controlled without knowledge of its instinctive patterns, evolutionary history, and ecological niche.

What the Brelands discovered using repetitions and statistics and the scientific method mirrors my own very unscientific message that dog training is something that was invented by humans, but dog psychology was invented by Mother Nature. This is why I urge you to think of your dog in four ways, in the correct order: animal, species dog, breed, name. The early behaviorists were thinking animal only. The early ethologists were thinking mostly species and breed. Many Kennel Club people are thinking breed first. And most American pet owners are thinking either breed name or just plain name—for example, “My dog is Fluffy, and Fluffy is my daughter.” The Brelands’ paper back in 1961 was the beginning of putting it all together to understand that we have to honor and respect the whole being of a dog or any animal before we can clearly communicate with it.

I first learned that others were thinking along these lines when I read Dog Psychology: The Basis of Dog Training by Leon F. Whitney, a veterinarian and hunting hound breeder and trainer, and The Dog’s Mind: Understanding Your Dog’s Behavior by Dr. Bruce Fogle, a British veterinarian and a founding member of the Society for Companion Animal Studies in the United Kingdom and the Delta Society in the United States. This past spring, sixteen years after first opening his book, I had the opportunity to have lunch with the venerable Dr. Fogle in Cannes, France, and to thank him in person for letting me know that my ideas and observations about dogs weren’t crazy after all. The good doctor is sort of a hero of mine, and we were both delighted to find out that we share many views, especially the observation that many dog behavior issues—even some “psychosomatic” medical issues that show up in Dr. Fogle’s veterinary office—can be traced back to a dog’s unhealthy interaction with its human owners.

“You know, operant conditioning is such a valid way of training,” says Kirk Turner, a big believer himself in operant conditioning, clicker training, and positive reinforcement. “What gets in the way is life for many people with dogs. As you know from your TV show, Cesar, the problem isn’t usually the dogs. They are a piece of cake. It’s usually the owners that you really have to figure out.”

Like Kirk, I’ve discovered that before we even think about rules to train our dogs, we need a better set of rules in order to train ourselves.