9

EXPLORING MUSLIM MILLENNIALS’ PERCEPTION AND VALUE PLACED ON THE CONCEPT OF ‘HALAL’ IN THEIR TOURISM PREFERENCES AND BEHAVIOURS

Millennials are much more likely to be intrigued about a trip to Thailand rather than the $8,000 Rolex watch that defined affluence for previous generations.

(Swartz 2016)

What makes the millennial Muslim market unique is their cross-cultural background, their love for the internet, and the mastering of social media. It is not an age group that brands should target but a mind-set.

(Salmani 2016)

Muslim tourists and halal tourism are gaining increased recognition as a distinctive tourist segment and area of tourism research respectively. Stakeholders across tourism industry are gearing up to adopt ‘halal’ tourism, as evident in a number of initiatives across tourism industry (Battour & Ismail 2016). These developments are based on the premise that Muslim consumers value halal products and services. It is irrational to assume Muslim consumers around the globe and across many generational cohorts are uniform in their preferences and behaviours. Therefore, amid the excitement surrounding halal tourism, a pertinent yet unanswered question is the importance of halal in tourism among different segments within the over 1.6 billion Muslim consumer market. This study presented in this chapter explores value of halal among one of the most important Muslim tourist segments—Muslim millennials.

Muslim millennials appear to have a different disposition in the internet-connected world. A 2012 report by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) Malaysia has pointed to different rising incomes and peculiar preferences among the Malaysian millennials. More interest in working flexibly and eyeing international opportunities amid being ardent technology users are some of the defining characteristics for millennials (PwC 2012). Similar observations have been made for Asian millennials in general (Wu 2017). These are among the ever-increasing studies done on millennials. In marketing segmentation research, millennials represent the consumers born between 1980 and 2000 and are also known as Generation Y (PwC 2012; Valentine & Powers 2013). Millennials were born in and later grew up in the era of information technology.

At an industry level, there is an increasing interest in studying the preferences of millennials (aged 18–35 years as of 2016–2017) within the overall Muslim consumer market. This increase in interest is particularly visible in the latest edition of the Global Islamic Economy Report (Thomson Reuters 2016). This edition dedicated a portion of its research on different sectors of the Islamic economy to understanding the preferences of Muslim millennials. Amid the heightened interest in the industry, academic research on Muslim tourists fell short of particularly investigating the preferences of Muslim millennial tourists. This study is an attempt to fill this research gap.

Literature on tourism points to a number of tourist behaviours and decisions that tourists take during travelling. Tourist behaviours and decisions are influenced by different factors including their personality traits. For Muslim tourists, the decisions like destination selection, place to stay, and what and where to eat can be further influenced by Islamic injunctions. This can be expected of Muslim tourists in general, based on the influence of religion on consumer preferences and behaviours. However, when it comes to Muslim millennials, we do not know the significance of halal in their preferences and decisions.

Therefore, to fill this gap in our comprehension, we are exploring the tourist behaviours and preferences of Muslim millennials. In particular, we are trying to identify what is the value of halal in their preferences and decisions. The term ‘halal’ is deeply associated with Islam. It literally means permissible and connotes those things that Muslims can consume. In the same vein, the connotation used for halal in this research question is to see the influence of Islamic injunctions on Muslim consumers’ decision-making in the area of being a tourist. In other words, value placed on halal relates to the importance given to Islamic injunctions. This is expressed in the main research question of this study: What is the value Muslim millennial tourists place on ‘Halal’ in destination choice and other tourist preferences?

The primary research question is focused on the halal element alone. To gain a comprehensive understanding of Muslim millennial tourists, we also undertook to explore the associated research question: What are the different factors that influence tourist preferences and behaviours among the Muslim millennial tourists?

To explore these research questions, the rest of this chapter is organised as follows. A literature review covers research on tourist behaviours, Islam and tourism, and Muslim tourists. This leads to the methodology section detailing the research design. Results and findings are presented next and discussed in detail under different sections. Finally, the chapter concludes with a discussion of findings, which also covers the research limitations and future research directions.

Literature review

To better understand the tourist behaviours among Muslim millennials, this literature review covers the extant literature in tourism, halal tourism, and millennial segmentation. First, a review of different forms of tourist behaviours and preferences are discussed. This is followed by a review of current trends in halal tourism and studies on Muslim tourists’ behaviours and preferences. Finally, the literature review is complemented by reviewing literature on defining millennials as well as Muslim millennials as distinctive segments. A research agenda is developed and presented from this literature review in the next section.

Tourism and tourist behaviours

An ordinary consumer, living in any part of the world, assumes the role of a traveller when he or she is disinhibited from his home. Yet, for the purpose of compiling information, a tourist or visitor is discerned from a traveller using the length of his/her stay. This distinction is expressed in the definition of a tourist or visitor used by the World Tourist Organization: “A visitor (domestic, inbound or outbound) is classified as a tourist (or overnight visitor), if his/her trip includes an overnight stay, or as a same-day visitor (or excursionist) otherwise” (United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) 2014). Accordingly, a tourism trip is a trip taken by a tourist or visitor for any reason other than gaining employment (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Statistics Division (UNSTATS) 2008). In congruence with these widely inclusive definitions of tourist and tourism, the motivations to undertake tourism are also quite diverse—ranging from tourism for casual recreation to health tourism.

Within the diverse forms of tourism, there are a range of activities which are regarded as tourist behaviours. Pizam and Sussmann (1995) enumerated 20 tourist behaviours including activities like taking photographs, bargaining during shopping, and travelling alone or in groups, among others. Using factor analysis, these behaviours were grouped into five categories including: social interactions, commercial transactions, activities preference, bargaining factor, and knowledge of destination. These behaviours define the travelling style of different individuals and were found to be influenced by the nationality of tourists. Manrai and Manrai (2011) listed a number of behaviours divided in the three categories of before, during, and after-travel behaviours. Examples of tourist behaviours in these lists included binary decision of travelling or not (before travel), length of stay (during travel), and destination revisit intention (after travel).

Another important aspect of tourist behaviour is the decision-making process. Based on an extensive review of earlier studies, Cohen, Prayag and Moital (2014) discussed ‘decision-making’ among the tourists as a key process. They argued that contrary to common belief, tourist decision-making is not an extensive and disciplined process. Among the decisions made by a tourist, selection of destination is a major decision, which has been classified as a tourist behaviour (Manrai & Manrai 2011). Manifested either as a tourist decision or behaviour, destination choice can be attributed to different social, economic, and personality traits. Reviewing literature on tourist behaviours, Lepp and Gibson (2008) talk about the role of sensation-seeking as a distinct personality trait besides novelty-seeking and risk-taking. These traits influence a tourist’s style of travelling and tourism-related preferences.

An emerging area in understanding the factors influencing tourist behaviour is the concept of self-image or self-concept of any tourist. Todd (2001) applied self-theory to study self-concept in the case of tourist behaviour. The self-concept model was found to have some applicability in the context of tourism as well. Consequently, it is important to understand that how a tourist perceives himself or herself, then this self-concept will define their style of thinking and even behaviours. Similar application of consumers’ self-image has also been done in the context of tourism (Murphy, Benckendorff & Moscardo 2007). This also reifies the importance of a consumers’ self-image in his or her tourist behaviour and destination choice.

Islam and tourism: halal tourism

Within the academic and industry research on tourism, halal tourism is a burgeoning area. In successive editions of the Global Islamic Economy Report (GIER), there is a continued emphasis on halal travel as a key segment of Islamic economy. According to recent estimates in GIER, the volume of Islamic economy is around USD1.8 Trillion and halal tourism has hovered around USD150 Billion (Thomson Reuters 2016). To understand the growing industry of halal tourism, it is useful to understand the existing research on Islam’s perspective on tourism.

According to Din (1989), Islam’s views on tourism differ from contemporary, secular views. Seemingly, there is not much encouragement for tourism only for the pleasure of it. Instead, Islam views tourism as a purposeful journey aimed at earning livelihood through trade and even bringing Muslims from different parts of the world together. Such journeys and tourism activity demand perseverance and patience from travellers. Jafari and Scott (2014) have discussed exploring the world as another important facet of travelling (and tourism) in Islam. Their assertion is based on the verses of Holy Quran, which ordain Muslims to engage in travelling for the sake of gaining knowledge and exposure. As a consequence, travelling and tourism has to be an act of consideration and contemplation and should be spiritually ‘purposeful’. These reflections imply that tourism for economic, social, cultural, and learning reasons is permitted and even encouraged in Islam.

According to Mohsin, Ramli and Alkhulayfi (2016): “Halal tourism refers to the provision of a tourism product and service that meets the needs of Muslim travelers to facilitate worship and dietary requirement that conform to Islamic teachings.” The industry trends and market practices in tourism industry also corroborate this definition of halal tourism. There has been a consistent increase in the number of tourist destinations and organisations keen on accommodating Muslim consumers by being Muslim-friendly (Seth 2016). Japan is one recent example in this regard, where a surge in Muslim tourists mostly from Malaysia and Indonesia led to creating policies and guidelines for making Japan a Muslim-friendly destination (Penn 2015).

Muslim tourists

There are a few studies on finding the preferences of Muslim tourists from different regions. In an unprecedented qualitative research on tourism preferences of Muslim tourists from North America, Shakona et al. (2015) found Islamic injunctions to have a clear influence on Muslim tourist preferences. The study resulted in a list of different considerations of Muslim tourists. These considerations pertained to availability of a mosque to pray, following rules for hijab and Mahram, eating halal food, and being cautious of their actions during the fasting month of Ramadan.

Among Muslim countries, Malaysia has been consistently leading in different indicators that constitute halal travel in the Global Islamic Economy Report (Thomson Reuters 2015, 2016). In addition to the strong and positive indicators for inbound tourism, Malaysian tourists are also deemed to be an important consumer segment among Asian tourists. In a competitive analysis, Kim, Im and King (2015) studied the preferences of Malaysian Muslim tourists comparing South Korea, China, and Japan as destination choices. The study found that ‘environment’ and ‘access to Muslim culture’ were the two most important factors in destination choice among the Malaysia Muslim tourists. Within ‘access to Muslim culture’, factors like accessibility of prayer space and halal restaurants were the main concerns. Another study covering Malaysian tourists focused particularly on students or young tourists. The study focused mainly on their activities and preferences like staying at a hotel or relatives, duration of stay, and spending patterns (Chiu, Ramli, Yusof & Ting 2015).

Among different factors studied, religiosity or religiousness of a tourist is expected to have a bearing on Muslim tourists. In part, this proposition is made based on the generic findings that Muslims as consumers exhibit a great influence of their religion. However, there is evidence of influence of religiosity in tourism literature as well. As Shakona et al. (2015) and Kim et al. (2015) showed, Muslim tourists exhibit a strong influence of Islamic injunctions in destination selection and activities during the trip. Such observations have led to a surge in research in the domain of halal tourism.

Despite the visible importance of Muslim millennials in the industry, there is limited academic research on this segment. In the case of tourism literature, this research gap is even more profound. In research on Muslim tourists, Kim et al. (2015) studied Malaysian Muslim consumers and not specifically millennials. On the other hand, Chiu et al. (2015) focused on young consumers but not necessarily Muslims. Thus, there is no specific study exploring the preferences of Muslim millennial tourists and the value this important segment places on the concept of halal in tourism.

Methodology

This study is mainly exploratory in nature aimed at finding the preferences of Muslim millennial tourists. Primary focus was to determine the value of halal in defining the tourism behaviours and preferences of Muslim millennial tourists. To elicit respondents’ opinions on their tourism preferences and behaviours, a survey consisting of open-ended questions was used. Use of open-ended questions allows respondents to give their opinions more freely albeit there are concerns as to whether they can give their opinions or not (Geer 1988). Haddock and Zanna (1998) have underscored the usefulness of open-ended questions in eliciting consumers’ beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours. They also showed from previous research that respondents do not find it difficult to answer open-ended questions to express their evaluative opinions.

The survey instrument was in two parts. In the first part, open-ended questions for preferences of destination choice, place to stay, and places to eat were asked. In this part, respondents were asked to give their opinions and preferences in open-ended questions, without any mention of halal or Islamic. The second part of the survey contained a mix of open and closed questions. In this part, respondents were specifically asked about their preferences relating to halal in choosing a destination, place to stay, and place to eat. The response options were: not important at all, slightly important, moderately important, very important, and extremely important—later coded on a five-point scale of 1 to 5 respectively. In this way, moderately important at 3.0 was the midpoint response. The last set of questions asked consumers about their self-image on being a Muslim tourist or global tourist. This question was aimed at exploring the self-image of Muslim millennials. Being a global tourist manifested their connectedness, while being a Muslim tourist shows their association with their religion. In this manner, the two parts of the survey were effectively ‘unaided’ and ‘aided’ recall for halal in responses. This allowed for exploring and comparing both the unaided and aided recall for halal in different aspects of tourism.

The questionnaire was administered using the online survey platform, Qualtrics. The interactive features of Qualtrics ensured that in this self-administered survey, respondents had to reply progressively from one section to the other. They were not allowed to navigate back to previous parts. Such an arrangement ensured that respondents could not change their responses in the first part (where no cues for halal were given), after seeing the second part (which was about the importance of halal in tourist activities). If any respondent had gone back to the first part after realising the importance of halal in the second part, the element of unaided recall would be missed. In this way, a mix of pure open-ended, unaided questions in the first part and hybrid of open- and close-ended questions in the second part, allowed deeper exploration of consumers’ actual preferences. Here it is important to note that Reja, Manfreda, Hlebec and Vehovar (2003) have shown concerns on data quality of open-ended versus close-ended online questionnaires. These concerns pertain mostly to missing data and possible issues of generic answers. In our case, since the questions were aimed at exploring traits and association with halal or Islamic values, we believe that open-ended questions would not be problematic.

Results and findings

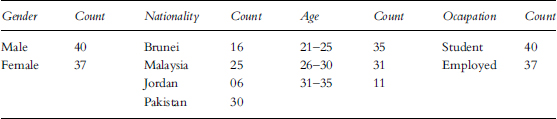

A survey link from Qualtrics platform was sent to students in different social networks and personal contact lists of the authors. In all, 77 respondents completed the survey. Around 20 respondents partially completed the survey or their responses were not properly recorded. These were not included in the analysis. Most of the respondents were in the age group 21 to 30 years. They were evenly divided in terms of gender as well as in terms of occupation. The respondents were mostly from South East Asia (Brunei and Malaysia), followed by South Asia (Pakistan) and Middle East (Jordan). South Asian and South East Asian consumers are the largest geographical segments of the global Muslim population, representing 35 per cent and 26 per cent of the 1.6 billion global Muslim population. These important segments are aptly represented in the geographical breakdown of respondents, as shown in Table 9.1.

Tourist preferences

The first part of the questionnaire contained questions which were purely exploratory in the sense that respondents were asked about their preferences and choices in open-ended questions. We wanted to see whether they showed any association with halal or Islamic lifestyle in any way. The first three questions within the first part asked respondents to list five considerations each for destination choice, selecting places to stay, and places to eat. Responses for each of these questions were reviewed to search for those considerations which related in any way with halal or Islamic injunctions. Since the open-ended responses gave liberty to the respondent to use any words or phrases, it was important to scan all responses to search for any association with Islamic values.

For the first question, considerations for destination choices, 77 respondents gave 312 responses. Out of these 312 considerations, only 15 responses could be related in any way with ‘halal’ or Islamic. These 15 responses by 14 different respondents represented 4.8 per cent of total responses and 18.2 per cent of total respondents. Within these 14 responses, majority included consideration for availability of halal food, followed by consideration that the country should be a Muslim country. In the same manner, the next question asked respondents to list considerations for places to stay. Out of the 323 responses or considerations, only 7 responses by as many respondents were related to halal or Islam in any way. This represented 2.1 per cent of total responses or 9.1 per cent of total respondents showing any consideration for halal. Even though these considerations were for places to stay, availability of halal food dominated again. Five out of these 7 responses were focused on availability of halal food. The other two focused on availability of prayer place. Situation was quite different in the third question in this series, which was about selecting a place to eat. Here, results showed a different picture altogether. Some 43 responses out of a total 319 responses by 43 respondents were for halal food. These responses were 13.4 per cent of total responses by 55.8 per cent of total respondents.

In these three questions, considerations for halal or any Islamic injunctions seemed significant only for selecting places to eat. Respondents seemed to have placed little value on halal or Islamic injunctions in destination choices or places to stay. Regardless how significant or insignificant consideration for halal was across the three tourist decisions or behaviours, the focus remained on availability of halal foods.

Preferred destinations

Within the first part, respondents were also asked for their preferred destinations for travelling. Intention was to understand whether Muslim or non-Muslim destinations are the preference for Muslim millennials. When asked to choose between a foreign or local destination, 58 or 75 per cent of respondents wanted to go to a foreign destination compared to 19 preferring a local destination. This favouring of a foreign over local destination should be seen in the context that the local destination of these respondents was a Muslim country. The nationality-wise breakdown shows that in terms of proportion, Bruneian and Jordanian consumers showed somewhat stronger preference for a foreign destination over a local destination. In terms of gender, the proportion was representative of the overall breakdown, hence no gender differences were observed in the choice for preferred destination. Breakdown of responses in terms of nationality and gender is given in Table 9.2.

Table 9.2 Preferred destination—foreign versus local destination

| Responses | Foreign destination | Local destination |

|---|---|---|

| Percentage figures in brackets show proportion of total | ||

| Overall (n = 77) | 58 (75%) | 19 (25%) |

| Nationality | ||

| Malaysia (25) | 16 (64%) | 9 (36%) |

| Brunei (16) | 16 (100%) | – |

| Pakistan (30) | 20 (67%) | 10 (33%) |

| Jordan (6) | 6 (100%) | – |

| Gender-wise | ||

| Male (40) | 30 (75%) | 10 (25%) |

| Female (37) | 28 (76%) | 9 (24%) |

In further examining the choice between a local or foreign destination, the next question asked respondents to list up to five international destinations they would prefer to go. A total of 376 international destinations were listed. Out of these, 270 or 71.8 per cent were non-Muslim countries and 106 or 28.2 per cent were Muslim countries. The breakdown of these destinations validated the earlier response of a stronger preference for non-Muslim countries over Muslim countries. A review of country-wise breakdown did not show any specific patterns and thus is not presented here.

Importance for halal

While the first part of the survey explored an unaided recall or association with halal, the second part was more of an aided recall for association with Halal. In this part, the questions sought consumers’ preferences in destination choice, selecting place to stay, and place to eat—the same areas as of the first part. However, here the questions were deliberately framed to highlight the importance of halal or Muslim-friendliness in these three areas. Respondents were asked about the importance of halal or Muslim-friendliness in their destination choice, place to stay, or place to eat. In this way, the respondents were answering more specifically about the importance of halal in their tourism preference. In the previous part, we noticed nominal association with issues related to halal or Islam. Surprisingly, in this part, the responses showed a much more pronounced importance of halal across the three decisions—destination choice, place to stay, and place to eat.

Three successive questions asked respondents to rate the importance of halal or Shariah-compliance in choosing destination, place to stay, and place to eat. In the aggregate scores for all respondents, the average score for importance of halal in selecting place to eat was 4.55. On a scale of 1 to 5, this was well above the mid-point value of 3.0. Importance of halal in selecting a place to eat was also much higher than importance of halal in destination selection (3.51) and selecting place to stay (3.36). These responses show that for consumers the concept of halal is most important in the case of places to eat and moderately important in deciding the destination or place to stay. Nationality-wise averages showed that Malaysian consumers gave highest importance to halal compared to consumers from any other country and in any decision. They are followed by Jordan, Pakistan, and Brunei. Gender-wise averages were generally representative of the overall scores. Therefore, no major male–female disparity could be observed. Responses to these questions are tabulated in Table 9.3, showing the importance of halal in three areas.

Table 9.3 Importance of halal in different tourist behaviours

| Responses | Importance of halal in destination selection | Importance of halal in selecting place to eat | Importance of halal in selecting place to stay |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 3.51 | 4.55 | 3.36 |

| Nationality | |||

| Malaysia | 4.64 | 4.80 | 4.00 |

| Brunei | 2.75 | 3.88 | 2.88 |

| Pakistan | 2.90 | 4.67 | 3.07 |

| Jordan | 3.83 | 4.67 | 3.50 |

| Gender-wise | |||

| Male | 3.33 | 4.73 | 3.25 |

| Female | 3.70 | 4.35 | 3.49 |

A subsequent question asked the respondents to select the features they thought were expected to be in a halal or Shariah-compliant tourist destination. Our motivation to ask this question was to explore the consumers’ expectations from a tourist destination that brands itself as a halal or Muslim-friendly tourist destination. This question was a hybrid of open-ended and close-ended questions as there were four multiple-choice options in addition to an option of ‘other’ features. In other features, respondents could list their own preferences. This made this question a mix of close-ended and open-ended. Out of 164 options selected by all respondents, Offered prayer place was the leading option selected by 66 respondents and it constituted 40.2 per cent of total responses. This was followed by Do not serve wine/alcohol (42 respondents, 25.6 per cent of total responses), Require modest dressing (23 respondents, 14.0 per cent of total responses), Restricts non-family male–female interactions (17 respondents, 10.4 per cent of total responses). Among the options given by 16 respondents using the other features options, half mentioned halal food as a feature they expect from a halal or Shariah-compliant tourist destination.

Self-image as a Muslim tourist versus global tourist

Based on the self-concept theory or concept of self-image, one important question in the survey sought self-rating as either a Muslim or global tourist. Respondents were also asked to give a rationale for their self-rating. Muslim millennial tourists seemingly have duality of being a Muslim and a globally connected person willing to experience other cultures. Whether they have a self-image of being a ‘Muslim tourist’ or a ‘global tourist’ can have implications for their thinking style and tourist behaviours. Thus, in the second part, where responses were already framed in a specific context of halal, the last two questions were aimed at exploring the self-image held by Muslim millennial tourists. Respondents were asked, on a scale of 0 to 10, the extent to which they see themselves as a global tourist or a Muslim tourist. Owing to the interactivity of the online response format, the responses could be given in intervals of 0.5, for a finer gradation.

The responses in this question were highly elucidating, to say the least. Average score for self-image of Muslim tourist (6.99 out of 10) was slightly higher than that of global tourist (6.09). Scores for Muslim tourist and global tourist had a correlation of – 0.31, which means respondents who identify themselves more as a Muslim tourist tend to agree less with being a global tourist. Scores for self-image, both nationality- and gender-wise, are presented in Table 9.4. All scores are out of 10.

Table 9.4 Self-image as a Muslim tourist versus as a global tourist

| Responses | Muslim tourist | Global tourist | Correlation (r) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 6.99 | 6.09 | – 0.31 |

| Nationality | |||

| Malaysia | 7.98 | 5.30 | 0.02 |

| Brunei | 6.69 | 6.75 | – 0.48 |

| Pakistan | 6.32 | 6.80 | 0.36 |

| Jordan | 7.08 | 4.08 | – 0.48 |

| Gender-wise | |||

| Male | 7.24 | 6.08 | – 0.29 |

| Female | 6.73 | 6.11 | – 0.34 |

Note: All scores are out of 10.

There are glaring differences in preferences of respondents from different countries. Malaysian and Jordanian respondents considered themselves more as a Muslim tourist than a global tourist. An opposite scenario was there for the Pakistani tourists. Bruneian consumers showed an intermediate perspective. The correlation data also show diversity among respondents from different countries. Being identified more as a Muslim tourist meant less as a global tourist for Bruneian and Jordanian respondents. However, for Malaysian respondents, there was no correlation in this regard. For Pakistani consumers, the positive relation showed plausibility of being a global tourist while being a Muslim tourist, at the same time.

A related and equally important question followed this self-image rating. After self-rating as global and Muslim tourists, the respondents were asked to give a rationale for their ratings. Beyond the quantified observations, the reasons for holding a particular self-image was also insightful. The reasons for holding the self-image as a Muslim tourist validated a key finding from previous questions in the survey. The results of previous questions showed that concepts of halal and Shariah-compliance were mostly related with food. In these self-image questions, similar observations were made as respondents giving high ratings for self-image of being a Muslim tourist did mostly because of concerns for halal food. On the other hand, those who responded highly on self-image of being a global tourist mostly showed interest in experiencing different cultures. These opinions and their diversity can be best expressed in the following four selected responses in which the respondents are rationalising their choice of being a global or Muslim tourist.

Travelling is all about learning. If you restrict yourself and not be open to new experiences then it is really difficult for you to learn and groom. Personally, for me travelling has taught me more than I’ve learned from my Bachelor’s degree. Being open to new experiences is the key.

(Male, 24, Pakistani/Muslim tourist: 5.0, Global tourist: 9.5)

I would consider myself a Muslim tourist as long as Halal food is available the bathrooms have Muslim showers and clean water. In terms of being a global tourist, it’s always exciting to experience different cultures. That is one of my reasons for being fond of travelling.

(Female, 27, Pakistani/Muslim tourist: 6.0, Global tourist: 6.0)

Being a Muslim, I must be conscious about my values as Muslim to make sure I don’t comprise my religious values in seeking for worldly pleasure, but at same time taking tourism as avenue for educating oneself, which is also consonant with Islamic religion, so as a global tourist here, I would long to get to learn more to the maximum from that place, being that I am open-minded person.

(Male, 33, Malaysian/Muslim tourist: 8.0, Global tourist: 5.0)

As a Muslim tourist, I would not consider eating non-halal food. As a global tourist, I would have no qualms about observing/trying different traditions as long as I am not required to eat/touch non-halal items, and am provided the facility to pray.

(Female, 24, Bruneian/Muslim tourist: 10.0, Global tourist: 5.0)

Discussion and conclusion

This exploratory survey forays into understanding the preferences and behaviours of Muslim millennial consumers in the domain of tourism. The findings and implications of this study are quite insightful. First, it merits mentioning that gender differences were not observed. Male and female respondents were almost equally represented in the sample and their responses were found to be almost similar. In other words, the responses for different questions by male and female respondents were almost the same as aggregate responses. This gender-neutrality of responses contrasts with some previous studies in tourism research, where gender differences were found to be profound and/or females were found to be more active in travelling than males (Tilley & Houston 2016).

The main takeaway from this study are the findings about value accorded to halal by Muslim millennials. Through responses to open-ended and close-ended questions, it was evident that Muslim millennials had much less concern of the importance of halal in selecting the tourist destination and place to stay. Especially in the open-ended, unaided questions on their preferences, there were nominal considerations for halal. Willingness to experience and budget seemed to be more important in selecting a tourist destination and place to stay. In total contrast, the consideration for halal was very high in selecting what and where to eat. Muslim millennials showed a strong concern for access to halal food and that is their key concern in selecting a place to eat, above any other consideration of hygiene and cost. Interestingly, the concern for halal food was so strong that it even influences their tourist destination selection and place to stay within the selected destination.

A related insight gained from the results is that ‘experience’ rather than ‘halal’ drives the Muslim millennial tourists and shapes their tourism preferences. Muslim millennial tourists are driven by an urge to experience other cultures, natural scenery, and historical places. They are more outward, keen to explore other cultures. Being experience-oriented is a dominant psychographic trait among millennials or Generation Y, as shown by Valentine and Powers (2013). This study corroborated this observation for Muslim millennials.

There are differences in consumers from different Muslim countries. For instance, Pakistani consumers seem to have a more global outlook compared to Malaysian consumers, who strongly identify as Muslim tourists. Within South East Asia, Malaysian consumers outpace Bruneian consumers in identifying strongly with being a Muslim tourist. A plausible explanation for these differences are the local cultures. Pakistan, the second most populous Muslim country, has more than 95 per cent Muslim population compared to 65 per cent in Malaysia and 70 per cent in Brunei. Both Pakistan and Brunei are conservative societies in their socio-political disposition. Malaysia has over the years grown into a more diversified and globalised society. It can be said that Muslim millennials in the conservative societies are longing for a globalised lifestyle while those living in a globalised lifestyle are bent on being relatively more conservative.

Finally, as for the limitations of this study, it merits mentioning that use of open-ended questions and qualitative approach proved insightful. Still, a small sample size was a limitation that needs to be addressed in future studies. Since there were differences observed among respondents from different countries, it is important that in future studies samples from different Muslim consumers are taken. Even within South East Asia, respondents from Brunei and Malaysia showed diverging responses in some areas. Differences were greater among South Asian, South East Asian, and Middle Eastern consumers. This exploratory study is expected to open up new avenues for research in Muslim tourism, millennial tourism, and of course Muslim millennial consumers and tourists.

References

Battour, M. and Ismail, M.N. (2016) ‘Halal tourism: Concepts, practises, challenges and future’, Tourism Management Perspectives, 19 (B): 150–154.

Chiu, L.K., Ramli, K.I., Yusof, N.S. and Ting, C.S. (2015) ‘Examining young Malaysians travel behavior and expenditure patterns in domestic tourism’. In The 2015 International Academic Research Conference. Paris, France: 47–54.

Cohen, S.A., Prayag, G. and Moital, M. (2014) ‘Consumer behaviour in tourism: Concepts, influences and opportunities’, Current Issues in Tourism, 17 (10): 872–909.

Din, K.H. (1989) ‘Islam and tourism’, Annals of Tourism Research, 16 (4): 542–563.

Geer, J.G. (1988) ‘What do open-ended questions measure?’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 52 (3): 365–371.

Haddock, G. and Zanna, M.P. (1998) ‘On the use of open-ended measures to assess attitudinal components’, British Journal of Social Psychology, 37 (2): 129–149.

Jafari, J. and Scott, N. (2014) ‘Muslim world and its tourisms’, Annals of Tourism Research, 44 (1): 1–19.

Kim, S., Im, H.H. and King, B.E. (2015) ‘Muslim travelers in Asia’, Journal of Vacation Marketing, 21 (1): 3–21.

Lepp, A. and Gibson, H. (2008) ‘Sensation seeking and tourism: Tourist role, perception of risk and destination choice’, Tourism Management, 29 (4): 740–750.

Manrai, L.A. and Manrai, A.K. (2011) ‘Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and tourist behaviors: A review and conceptual framework’, Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science, 16 (31): 23–48.

Mohsin, A., Ramli, N. and Alkhulayfi, B.A. (2016) ‘Halal tourism: Emerging opportunities’, Tourism Management Perspectives, 19 (B): 137–143.

Murphy, L., Benckendorff, P. and Moscardo, G. (2007) ‘Linking travel motivation, tourist self-image and destination brand personality’, Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 22 (2): 45–59.

Penn, M. (2015) ‘Japan embraces Muslim visitors to bolster tourism’, AlJazeera, 17 December. [online] Available at: www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2015/12/japan-embraces-muslim-visitors-bolster-tourism-151215112245391.html

Pizam, A. and Sussmann, S. (1995) ‘Does nationality affect tourist behavior?’, Annals of Tourism Research, 22 (4): 901–917.

Pricewaterhouse Coopers (PwC). (2012) Millennials at Work: Reshaping the Workforce. [pdf] Available at: https://www.pwc.com/my/en/assets/publications/millennials-at-work.pdf

Reja, U., Manfreda, K.L., Hlebec, V. and Vehovar, V. (2003) ‘Open-ended vs. close-ended questions in web questionnaires’, Developments in Applied Statistics, 19 (1): 159–177.

Salmani, S. (2016) ‘Introducing the millennial Muslim—and the global market that is worth trillions of dollars’, Mvslim.com, 7 April. [online] Available at: http://mvslim.com/introducing-the-millennial-muslim-the-global-market-that-is-worth-trillions-of-dollars/

Seth, S. (2016) ‘Halal travel morphs as Muslims seek new experiences and destinations’, Global Islamic Economy Gateway, 6 December. [online] Available at: www.salaamgateway.com/en/story/halal_travel_morphs_as_muslims_seek_new_experiences_and_destinations_-SALAAM06122016084107/

Shakona, M., Backman, K., Backman, S., Norman, W., Luo, Y. and Duffy, L. (2015) ‘Understanding the traveling behavior of Muslims in the United States’, International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 9 (1): 22–35.

Swartz, L. (2016) ‘What you need to know about millennial travelers’, Millennial Marketing. [online] Available at: www.millennialmarketing.com/2016/05/what-you-need-to-know-about-millennial-travelers/

Thomson Reuters. (2015) State of the Global Islamic Economy Report 2015/16. [pdf] Available at: https://ceif.iba.edu.pk/pdf/ThomsonReuters-StateoftheGlobalIslamicEconomyReport201516.pdf

Thomson Reuters. (2016) State of the Global Islamic Economy Report 2016/17. [pdf] Available at: https://ceif.iba.edu.pk/pdf/ThomsonReuters-stateoftheGlobalIslamicEconomyReport201617.pdf

Tilley, S. and Houston, D. (2016) ‘The gender turnaround: Young women now travelling more than young men’, Journal of Transport Geography, 54: 349–358.

Todd, S. (2001) ‘Self-concept: A tourism application’, Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 1 (2): 184–196.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Statistics Division (UNSTATS). (2008) International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics 2008. [online] Available at: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/publication/Seriesm/SeriesM_83rev1e.pdf#page=21 (accessed 22 September 2017).

United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). (2014) Glossary of Tourism Terms. [pdf] Available at: http://cf.cdn.unwto.org/sites/all/files/Glossary-of-terms.pdf (accessed 22 September 2017).

Valentine, D.B. and Powers, T.L. (2013) ‘Generation Y values and lifestyle segments’, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 30 (7): 597–606.

Wu, S. (2017) ‘Reaching Asia’s affluent millennials’, Asia Research PTE Limited. [online] Available at: https://asia-research.net/reaching-asias-affluent-millennials/