10

ISLAMIC ZIYĀRA AND HALAL HOSPITALITY IN PALESTINE

Al-Ḳuds ‘Jerusalem’, al-K̲h̲alīl ‘Hebron’, and Bayt Laḥm ‘Bethlehem’ between 2011 and 2016

Introduction

Over the past few decades, international tourism activity has shown substantial and sustained growth in terms of both the number of tourists and tourism receipts. While the world tourist arrivals and tourism receipts have been growing substantially over the years, world tourism markets witnessed some important changes in the direction of tourism. This has been clear in the increase observed in the relative share of the developing countries, including the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) member countries, in the world tourist arrivals and tourism receipts. As a group, the OIC countries attracted 174.7 million tourists in 2013, compared with 156.4 million in 2009. International tourism receipts in the OIC countries also recorded a significant increase of about $20 billion during the period 2009–2013 and reached $144.1 billion as of 2013 (OIC 2015b). Islam is one of the world’s major religions (Esposito 1999) and has an estimated one-and-a-half billion adherents. These are concentrated in the 57 countries belonging to the OIC and there are sizeable Muslim populations in other nations around the world (OIC 2017).

Over the last two decades, the Islamic lifestyle market has been growing as Shariah-compliant products and services (e.g. Ḥalāl food, Islamic tourism, and Islamic finance) have become an important component of the global economy. With an increasing awareness and expanding numbers of Muslim tourists around the world, many tourism industry players have started to offer special products and services, developed and designed in accordance with the Islamic principles, to cater to the needs and demands of these tourists. Nevertheless, despite attracting significant interest across the globe, Islamic tourism is a relatively new concept in both theory and practice. Islamic tourism activity remained highly concentrated in Muslim majority countries of the OIC, which are currently both the major source markets for Islamic tourism expenditures and popular destinations (OIC 2015b).

Nonetheless, several countries around the world and in the Mediterranean region paid attention to this tourism growth, and this interest in the tourism sector attributed to the growing numbers of Muslim tourists to various destinations across the globe. These countries have built a service infrastructure equipped with facilities that provide services to Muslim visitors (restaurants, resorts, accommodation, flights, etc.) in accordance with the principles of the Islamic S̲h̲ariah law. Travel is one of the fastest growing tourism sectors in the world, with an estimated growth rate of 4.8 per cent against the 3.8 per cent industry average (Dinar Standard 2012). In 2015, it was estimated that there were 117 million Muslim international travellers. This is projected to grow to 168 million by 2020, where the travel expenditure by Muslim travellers is expected to exceed 200 billion USD (Crescent Rating 2015).

A United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) (2016) report revealed the world’s fastest growing tourist destinations for 2017, and the results throw up a few surprises. One of the fastest growing destinations is Palestine (Haines 2017). Earlier in 2017 the street artist, Banksy, opened a boutique hotel in Palestine’s West Bank, which, in hindsight, appears to have been a sage move: tourism in Palestine is booming. According to the UNWTO, the occupied territories of Palestine witnessed a 57.8 per cent rise in international arrivals so far in this year. Overlooking the Israeli West Bank Segregation Wall, Banksy’s politically charged Walled Off Hotel has likely helped raise awareness of tourism in Palestine. However, the numbers of tourists in general and Muslims in particular do not match the religious status of cities, which can receive more than one million Muslim tourists annually. This chapter deals with Islamic and Ḥalāl tourism in three Palestinian cities: al-Ḳuds (Jerusalem), al-K̲h̲alīl (Hebron), and Bayt Laḥm (Bethlehem). This chapter will present the tourism situation in these Palestinian cities and the religious value of visiting the three cities for Muslims according to Islamic teaching (S̲h̲ariah law) and Islamic cultural heritage. In addition, this chapter will raise questions about the forces that affect the tourist situation in these cities, which lead to an increase or decrease in the number of Muslim tourists.

The historical background of Islamic visitors to al-Ḳuds, al-K̲h̲alīl, and Bayt Laḥm

Those who dig into the Arab and Islamic history of Palestine will find great interest in the three major tourism cities of the country, and will join hundreds of companions, some of whom spent their lives in Jerusalem and died there, and the well-known ʿulamāʾ, or intellectuals and religious scientists, referred to traditionally as the faḳīh, muftīun, muḥaddit̲h̲un, and mutakallimun, who came to Jerusalem to pray in the holy sites and to study in al-Aqsa Mosque (Abed Rabo 2012). From the beginning of the eighth century, Muslim visitors and pilgrims came to al-Ḳuds, al-K̲h̲alīl, and Bayt Laḥm to pray in the holy places. The places visited in al-Ḳuds were concentrated mainly on the al-Aqsa Mosque; in al-K̲h̲alīl the visit focused on al-Masjed al-Ibrahimi; and in Bayt Laḥm, the Church of Nativity. In Islam, al-Ḳuds is the land where Allah took the Prophet Mohammed on a night journey from al-Masjid al-Haram in Mecca to al-Masjid al-Aqsa in al-Ḳuds, which blessed its surroundings, and means the whole land of Palestine is blessed. Based on the night of the Isrāʾ, special traditions were circulated and established, e.g. ‘Literature in Praise of Jerusalem’ and ‘The Faḍāʾil literature’ (Athaminah 2013), in the Umayyad period in an attempt to encourage pilgrimage to al-Ḳuds and to pray there (Elad 1995).

In his book Faḍāʾil al Bayt al-Muqaddas, Abū Bakr al-Wāsiṭī (d. after AD 1019) presents an early tradition which dated to the first quarter of the eighth century. He wrote: “He who comes to Bayt al-Muqaddas [Jerusalem] and prays to the right of the rock [on the Haram] and to its north, and prays in the place of the Chain, and gives a little or much charity, his prayers will be answered, and God will remove his sorrows and he will be freed of his sins as on the day his mother gave birth to him” (Al-Wāsiṭī 1979: 23).

During the beginning of the eighth century most of the Muslims who went to Mecca to perform the Ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲ also came to Jerusalem before or after the Ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲, either to do the iḥram from al-Aqsa or to sanctify their pilgrimage. The most frequent Duʿāʾ (addressed to God) among the Muslims is the sanctity of your Ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲, which is an indication of the phenomenon of sanctifying the pilgrimage, and is preferred by Muslims to be done in Jerusalem. Those who can perform the Ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲, visit Jerusalem to sanctify their pilgrimage and if the pilgrim does so, his pilgrimage has been completed. Some pilgrims came to Jerusalem before the season of the Ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲ in order to prepare themselves for Ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲ or the ʿumra. This action was called iḥram, an act of declaring or making sacred or forbidden. The opposite is iḥlāl, an act of declaring permitted. The word iḥrām has become a technical term for the state of temporary consecration of someone who is performing the ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲ or the ʿumra; a person in this state is referred to as muḥrim. The entering into this holy state (also called iḥlāl) is accomplished, for men and women, by the statement of intention, accompanied by certain rites and, in addition, for men, by the donning of the ritual garment. Famous Muslim scholars like ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿUmar b. al-K̲h̲aṭṭāb (d. in 692–3), the son of the second caliph (r. 13/634–23/644) ʿUmar b. al-K̲h̲aṭṭāb, came to Jerusalem to perform the iḥram in al-Aqsa Mosque before the ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲ (Elad 1995). In the past, entering the state of iḥram from al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem and specifically from the Rock of Jerusalem was the common tradition of the majority of Muslims who performed the Ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲ or ʿumra, for example, Ṣāliḥ b. Yūsuf Abū S̲h̲uʿayb (d. in Ramla in AD 895) performed the Ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲ seventy times, and each time he would perform the iḥram from the Rock of Jerusalem [min Ṣak̲h̲rat Bayt al-Muqaddas] (Elad 1995). In the second half of the tenth century the Jerusalemite geographer al-Muqaddasī who described the people of North Africa, said that there were very few North Africans who did not visit Jerusalem. These huge numbers of Muslims who were visiting Jerusalem in the past are linked to the holiness of Jerusalem and stems from the combining of the pilgrimage to Mecca and al-Medina with the tradition of praying in Jerusalem before and/or after the ʿumra or the Ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲. The Ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲ activities, which Muslims do before or after performing the ʿumra or the Ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲, are based on a very strong Ḥadīth that permits the Ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲ to the three mosques: Mecca, al-Madina, and Jerusalem.

Many commentators explain the verses of the Quran about tourism and there are numerous forms of travel (see also Chapter 2, this volume). The first one is Ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲ that includes pilgrimage and journey to Mecca once in lifetime at least which is obligatory for each healthy adult Muslim except if unable physically. Muslims can make the Ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲ to al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem and other Muslim sacred sites in Palestine. The second is visit, in Arabic is Ziyara, which is related to visiting holy sites and places. The third one is trip, in Arabic Rihlah, which is a trip for other motives for instance learning and work, focusing on a meaningful movement as an element of the spiritual journey in the service of God.

The Prophet said: “Do not set out on a journey (for religious devotion) but for the three mosques—for this mosque of mine (at Medina) the Sacred Mosque (at Mecca), and the Mosque al-Aqsa (Bait al-Maqdis)” (Sahih Al-Bukhari: 15/465]). This Ḥadīth (statement) clearly indicates that to complete the Muslim pilgrimage it is highly preferred to do so by visiting all three mosques, which explains the visits of the famous Muslim companions and followers to Jerusalem through Arab and Islamic history of the city, and also this Ḥadīth is agreed upon by all Muslims as a strong Ḥadīth. Muslims used to visit Jerusalem after the ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲, for example people from K̲h̲urāsān came to Palestine with large groups of pilgrims and visitors in Jerusalem after their pilgrimage in Mecca. In H 414/AD 1024, the pilgrimage convoy passed through Ayla (Elath) and from Ayla to Ramla to the Shamat road to Baghdad. This convoy was described by al-Musabbiһ̣ī who mentioned that it included 200,000 people. In his writing, he declared that the people of Syria gained many economic benefits and that the people of the convoy were happy when they visited Jerusalem (Al-Musabbiһ̣ī 1980).

The phenomenon of visiting Jerusalem, either to sanctify the pilgrimage or to proselytise before the pilgrimage or to visit al-Aqsa and pray there, that existed during the Ottoman rule over Palestine, was limited during the British mandate to the people of Bilad al-Sham until 1948, and after the occupation of Jerusalem in 1967 was confined to the people of Palestine, who are still practising the rite today. This phenomenon has been renewed after the call by Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas and the activity of the Ministry of Awqaf and Islamic Holy Sites in Palestine and groups of Islamic countries that are encouraging Arabs and Muslims to visit Jerusalem and pray at al-Aqsa Mosque. At the end of S̲h̲aʿbān in May 2017, a number of Muslims from South East Asia came to Jerusalem and visited al-Aqsa Mosque to pray and to enter into a state of iḥram there before continuing to Mecca (Ma’an News Agency 2017).

For Muslims, al-K̲h̲alīl and Bayt Laḥm are the places where Prophet Mohammed prayed during the night of the Isrāʾ on his way to al-Ḳuds. On this night the angel Jibril asked him to come down and to pray two rak‘ahs, saying to him, “Here is the tomb of your father Abraham” (Ibn al-Murajja 1995: 331) and when Jibril passed by the Prophet Mohammed over Bayt Laḥm, he said to him, “Come down and pray here two rak‘ahs. Here is the place where your brother Isa ibn Maryam (peace be upon him) was born” (Ibn al-Murajja, 1995: 252). The traditions in praise of al-K̲h̲alīl do not differ in their meaning and structure from the traditions in praise of al-Ḳuds, which also spread from the beginning of the eighth century. These traditions deal with the praises of the tomb of Ibrahim, the rest of the patriarchs and their wives, as well as with al-K̲h̲alīl itself. According to tradition, the pilgrimage to Mecca, as is known, was combined with a visit to the Prophet’s Tomb. The Muslims of that period combined a visit to Mecca with one to Jerusalem, as well as a visit to the tomb of the Prophet Mohammed with one to the Tomb of Abraham in al-K̲h̲alīl (Hebron). The traditions say that all who visit both tombs in a single year are assured acceptance into Paradise. Someone who cannot, or is prevented from, visiting the Tomb of the Prophet, must visit the Tomb of Abraham, to pray and recite Muslim invocations. It is said prayers at Abraham’s tomb will be answered.

Concept notes

Most of the scholars who studied this type of tourism as well as the tourism institutions in different countries have used several concepts to define this phenomenon. Some of them used the concept: ‘Ḥalāl tourism’ (Battour & Ismail 2016). Others used both terms ‘Islamic tourism’ or ‘Ḥalāl tourism’ in the same study (Jaelani 2017), with both terms used interchangeably, while some institutions use ‘Ḥalāl friendly tourism’ to reflect the same meaning for the previous two concepts. We believe that the definition of these concepts should take into account some basic issues, which will affect the accuracy of the use of these concepts, for example: the purpose of the visit, which may determine the destination of the travel. The purpose of the visit leads us to consider whether is it to perform Ḥad̲j̲d̲j (the fifth of the five pillars (arkān) of Islam, also called the Great Pilgrimage in contrast to the ʿumra or Little Pilgrimage). Therefore, if the visit is to perform religious obligation, such as Ḥad̲j̲d̲j and ʿumra, the travel destination will be Mecca, al-Madina, al-Ḳuds and al-K̲h̲alīl, the four Islamic cities that Muslims are obliged to visit according to Islamic law and Islamic legacy. In this case, the Muslim cannot fulfil the obligatory duties without performing Ḥad̲j̲d̲j to the cities of Mecca and al-Madina, but before travelling to Mecca, Muslims should prepare themselves [Ihram] by praying at al-Aqsa Mosque in al-Ḳuds and in the Ibrahimi Mosque in al-K̲h̲alīl. These activities apply to the concept of ‘Islamic tourism’, which also includes visits to other religious sites such as shrines (Battour & Ismail 2016). This kind of Islamic religious tourism, of course, includes Ḥalāl activity, where a pilgrim obtains Ḥalāl services in accordance with the Islamic Sh̲ariah and its principles and values. Therefore, ‘Islamic tourism’ indeed encompasses what is now known as ‘Ḥalāl tourism’ with all its requirements.

The concept of ‘Islamic tourism’ cannot be applied to all destinations, whether in Arab or Islamic countries because performing Ḥad̲j̲d̲j can be done only in Mecca and the Ihram is preferred to be in al-Ḳuds, and praying in al-Aqsa Mosque, and visiting the Cave of the Patriarchs in al-K̲h̲alīl and praying there. While in terms of ‘Ḥalāl tourism’, it is the concept that applies to the activity of Muslims in Arab or Islamic countries where there are no religious places associated with Ḥad̲j̲d̲j and ʿumra. Therefore, the daily activities of Muslims in these destinations and the services that the Muslims receive there are services based on Islamic law. The third concept that is also used in the Islamic tourism market is ‘Ḥalāl friendly tourism’ which has appeared in the tourism industry market through non-Muslim countries in order to attract Muslim visitors to visit non-Muslim destinations. ‘Ḥalāl friendly tourism’ is another form of ‘Ḥalāl tourism’, but in non-Arab and non-Muslim countries. It aims to Islamise the services provided to Muslim tourists in non-Muslim countries. The common denominator between ‘Ḥalāl friendly tourism’ and ‘Ḥalāl tourism’ is the term Ḥalāl, which means that everything permitted in the Islamic Sh̲ariah is Ḥalāl.

Islamic and Ḥalāl tourism in al-Ḳuds, al-K̲h̲alīl, and Bayt Laḥm

The centre of al-Ḳuds and/or East Jerusalem is the Old City, which is located within the walls of the Ottoman city. While it is just a square kilometre in size, it was and remains a destination for tourists who have come to the city to visit historical and religious places within its walls and explore its rich legacy. Al-K̲h̲alīl, located 32 kilometres south of Jerusalem, is similar to al-Ḳuds in that it is a holy city for Palestinians and Muslims. It is the place where Ibraham al-K̲h̲alīl dwelt, and it contains his remains, and those of his family, Sara, Isaac, Rebkah, Jacob, and Leah. The location of their tombs was the reason al-K̲h̲alīl became a holy place. Between the end of the seventh and the beginning of the eighth centuries the name of the village of Hebron was Habra or Hibra. Muslim geographers of the ninth century called the place the Mosque of Abraham ‘Masjid Ibrahim’. In the middle of the tenth century the Jerusalemite geographer al-Muqaddasī (d. around AD 1000), used the names Habra and Masjid Ibrahim in his book Aḥsan al-taqāsim fī maʿrifat al-aqālīm (The Best Divisions in the Knowledge of the Regions) (Al-Muqaddasī 1906: 172). The name Ibrahim al-K̲h̲alīl, meaning Abraham the Friend (of God), was well known during the early Muslim period, and was used in all traditions that related to the area. Only in the thirteenth century does al-K̲h̲alīl emerge as the actual name of the city (Elad 1996). Bethlehem ‘Bayt Laḥm’ is a Palestinian city located 9 kilometres south of Jerusalem, it began to be honoured and visited by Christians from the fourth century until today. It became equally venerated by Muslims as the birthplace of Īsā ben. Maryam (Bayt Laḥm).

Arabs and Muslims lost their access to visit al-Ḳuds and the West Bank after the Israeli government declared occupation in 1967. Even after the signing of the Camp David Accord between Egypt and Israel in 1978, the Egyptian people refused to visit Jerusalem and the West Bank and considered that visiting these cities would be normalising the occupation. Political events developed in Jerusalem and the West Bank when the first Palestinian Intifada began in 1987, which ended with the signing of the 1993 Oslo Agreement between the PLO and Israel. Other Arab countries such as Jordan signed the Jordanian-Israeli peace agreement, but these agreements have not affected the prohibition of Arabs and Muslims from visiting al-Ḳuds and the West Bank under occupation.

Tourism began to flourish after the Oslo Agreement. By 1999 the number of tourists to Israel and al-Ḳuds reached up to 2,923,200 tourists and in 2000 the number was still climbing, reaching around 3,000,000 tourists. In 2001, the outbreak of the al-Aqsa Intifada led to a significant drop in the number of tourists who visited Jerusalem, plummeting from 3,000,000 to 639,300. The drop in tourism was due to the violence that erupted during the Intifada (Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies (JIIS) 2017). Eventually tourism began to recover as a result of stability, and by 2004 the number of tourists began to increase again. This number is almost unassuming if we compare it with Christian and Jewish tourist arrivals to Jerusalem, and it will be negligible compared to the huge number of Muslim tourist arrivals in other cities in the OIC, which in 2011 reached about 58.7 million Muslim tourists. Palestinian cities have received few Muslim tourists in comparison to other cities in the region. For example, during 2016, Mecca received 6 million pilgrims (this number is not including the Ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲), who performed the ʿumra (Al-Emarat alyoum 2015). While Jerusalem has received 2,568,300 tourists during 2015, only 440,900 of them stayed overnight in al-Ḳuds hotels, 54,331 of whom were Muslims, which is about 2.5 per cent. The number of visitors from different nationalities and religions increased very slowly during 2016 to reach 2,665,600, only 481,100 of whom stayed overnight in al-Ḳuds (JIIS 2017).

Up until 2011, very few Arab and Muslim tourists visited Palestine. However, since 2011 there has been a new phenomenon in the Palestinian and regional tourism market, namely, Islamic tourism to al-Ḳuds, al-K̲h̲alīl, and Bayt Laḥm, despite the controversy among Muslim scholars over the legality of visiting the cities due to the ongoing occupation.

Palestinians in general and the people of the three Palestinian cities, al-Ḳuds, al-K̲h̲alīl, and Bayt Laḥm, live in a traditional conservative society, whose traditions are reflected in the social context and in the preservation of traditional principles of socialisation, which are transferred from society to the individual. The conservative traditions stem from the Islamic religion, as well as Arab customs and traditions, which are not separated in Palestinian society. Because Palestinians have kept and preserved the importance of Palestine as a holy land, tourists are able and encouraged to visit Palestine under the concept of Islamic/Ḥalāl tourism. They will pray at al-Aqsa Mosque, which is one of the three holy mosques in Islam, visit the Nativity “Mahd Isa” in Bayt Laḥm (the birthplace of Jesus, considered a prophet in Islam), and pray at the Ibrahimi Mosque in al-K̲h̲alīl. Because Palestinians have maintained a religious culture, Muslim tourists will receive Ḥalāl services at their hotel accommodation and Ḥalāl food served in Palestinian restaurants. In addition, any tourist in Palestine will find that a mosque is never more than a few blocks away from their accommodation. Muslims visiting al-Ḳuds, al-K̲h̲alīl, and Bayt Laḥm will also find that within hotels there are places designated for prayer, while those who wish to pray in local mosques of these cities only need a few minutes to walk through the traditional markets to reach a mosque. The advantage of these sites is their location, where hotels, restaurants, and the aswāḳ (market/Sūḳ) traditional markets, and shopping centres are located close to religious and historical sites, which is a strong feature to attract Muslim tourists to visit these cities. During their stay, Muslim tourists will also discover the daily lives of Palestinians in the cities and refugee camps nearby.

There are also some Muslim tourists who come individually from non-Islamic countries to Palestine. These Muslim tourists often rent small apartments or rooms from Palestinian families to live in. Some of them rent rooms in refugee camps in Bayt Laḥm and al-K̲h̲alīl.

Palestinians in al-Ḳuds, al-K̲h̲alīl, and Bayt Laḥm especially, have created many initiatives and organisations to encourage this type of tourism, such as the Jerusalem Tourism Cluster (JTC) in Jerusalem, Visit Palestine, and Volunteer Palestine. Volunteer Palestine, for example, is an awareness-raising travel organisation for international visitors, established by refugees from Bayt Laḥm which runs volunteer placements within refugee camps in Palestine. As part of the volunteering placement, they facilitate homestays, political tours, and cultural activities to ensure the visitors experience the best of Palestine. While the organisation welcomes volunteers and tourists from all over the world, it places a special importance on targeting the Palestinian diaspora and Muslim international communities.

With the success of such programmes in the volunteer-tourism sphere, one could imagine a new concept of Ḥalāl volunteer-tourism flourishing in this market. With many Muslim cultures maintaining a conservative lifestyle around the world, the option of volunteering with an organisation promising a Ḥalāl experience could open up options for youth from conservative communities, particularly young women, to travel with the blessings of conservative family members.

While Palestine offers a plethora of religious sites and institutions for volunteers and tourists, the land also offers visitors an opportunity to go sightseeing at the natural sites and villages of the country, where they will also find all the necessary requirements for Islamic tourism and Ḥalāl services. Muslim tourists can enjoy The Masar Ibrahim al-K̲h̲alīl (Abraham’s Path, see Isaac 2017), a trail that runs through the West Bank from the Mediterranean olive groves of the highlands of the north to the silence of the deserts in the south, from the area west of Jenin to the area south of al-Haram Al-Ibrahimi in the city of al-K̲h̲alīl (Hebron).

In July 2017, the United Nations cultural arm declared the Old City of Hebron a protected heritage site in a secret ballot, an issue that has triggered a new Israeli-Palestinian controversy at the international body. UNESCO voted 12 to 3, with 6 abstentions, to give heritage status to Hebron in the Israeli-occupied West Bank. Hebron is home to more than 200,000 Palestinians and a few hundred Israeli settlers, who live in a heavily fortified enclave near the site known to Muslims as the Ibrahimi Mosque and to Jews as the Tomb of the Patriarchs. The resolution, brought by the Palestinians and which declares Hebron’s Old City as an area of outstanding universal value, was fast-tracked on the basis that the site was under threat, with the Palestinians accusing Israel of an ‘alarming’ number of violations, including vandalism and damage to properties. According to the UNESCO resolution Hebron is one of the oldest cities in the world, dating from the chalcolithic period or more than 3,000 years BC (Al-Jazeera 2017).

Tourist arrivals, hotels, and accommodation

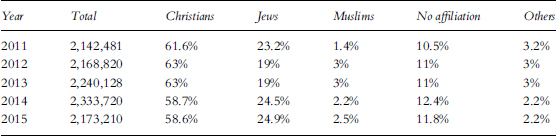

Despite the religious and historical importance of the city in Islam, the number of Muslims who visit al-Ḳuds is small compared to the number of Christians and Jews that visit Jerusalem (Table 10.1), or Muslim tourists visiting other Muslim cities or non-Muslim cities in the world. Table 10.1 shows the percentage of Muslim tourists who visited Jerusalem during the period 2011–2015, compared to other tourists from other religions during the same period (JIIS 2017).

In 2011, 2,142,481 million tourists visited Jerusalem. Only 477,300 of those tourists stayed in East Jerusalem hotels, 29,995 of which were Muslims, making up just 1.4 per cent of the total number of tourists who visited the city that year. The number of Muslim visitors to Jerusalem doubled in 2012. With 3 per cent of all visitors to Jerusalem being Muslim during that year, the number of Muslim tourists in the city increased to about 65,646 out of the 2,168,820 visitors documented. Of those in 2012, 448,200 tourists among them stayed in East Jerusalem. In 2013, the number of Muslim visitors continued to increase, reaching 67,204 Muslim tourists out of 2,240,128 visitors who came to the city. Among them, just 443,300 tourists stayed in East Jerusalem hotels. The number of Muslim tourists who visited Jerusalem decreased slightly in 2014 and 2015. In 2014, 51,342 Muslim tourists visited Jerusalem, representing 2.2 per cent of the total 2,333,720 tourists who visited the city, among them only 510,000 tourists stayed overnight in East Jerusalem hotels.

Although a newspaper report published in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz in 2015 indicated that the number of Muslim tourists significantly increased in 2015, official numbers dispute the reported increase. Haaretz reported 80,000 Muslim tourists to East Jerusalem in 2015: 26,700 of which were Indonesians, 23,000 Turkish, 17,700 Jordanians, 9,000 Malaysians, and 3,300 Moroccans (Paltoday 2015). These numbers differ from the official numbers given by the JIIS centre in 2015, which documented 54,330 Muslim tourists, about 2.5 per cent of the 2,173,210 total (JIIS 2017), which indicates an increase of 3,000 Muslims tourists between 2014 and 2015.

While the highly respected Travel and Leisure (T&L) magazine listed Jerusalem as one of the top ten tourist destinations in the world in 2015 (Lieberman 2015), Jerusalem still experiences low rates of tourism when compared to other international tourism cities due to the instability created by occupation. For example, tourism observers attribute the drop in the number of tourists who visited Israel during 2014 and 2015 to the Israeli war on Gaza (Al-Jazeera 2015). Analysing the statistics, it seems the war in Gaza caused a decrease in the number of Muslim tourists in particular during that period (see Table 10.1) (see also Isaac, Hall & Higgins-Desbiolles 2016).

Between 2011 and 2015, the number of hotels operating in Jerusalem’s Old City and surrounding area stood at 30 hotels. In 2016 the number rose to 31. The total number of rooms offered in these hotels ranged between 1,905 in 2011 to 2,052 in 2016 (JIIS 2017). During the period between 2011 and 2015, the restaurants available in al-Ḳuds hotels increased from 32 restaurants to 41, creating an increase in potential capacity from more than 3,105 customers to a new capacity of 4,000 customers (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) 2016).

Regarding the number of Muslim tourists who visited Bayt Laḥm and al-K̲h̲alīl, we do not have official statistics from the Ministry of Tourism or the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for the numbers. The statistics provided by the Ministry of Tourism through the tourism and antiquities police or those provided by the PCBS are statistics according to the country or the regions that tourists came from. The figures and percentages presented in this chapter about the numbers of Muslim tourists who visited East Jerusalem are supposed to apply also to the Muslim tourists who visit the cities of al-K̲h̲alīl and Bayt Laḥm because these cities are part of the organised tour for Muslim tourists who visit these three cities (Paltoday 2015).

The number of tourists who visited the cities of al-K̲h̲alīl and Bayt Laḥm and stayed overnight between 2011 and 2015, according to the PCBS, ranged between 225,164 and 314,380 tourists, which is half of the total number of tourists visiting East Jerusalem, and less than 1 per cent of the total tourists who visited Jerusalem in general. The number of hotels operating in al-K̲h̲alīl and Bayt Laḥm is slightly higher than the hotels in al-Ḳuds. In 2011, there were 28 hotels operating in Bayt Laḥm and al-K̲h̲alīl, while in 2015, the number of hotels increased to 37, most of which were located in Bayt Laḥm. The number of rooms in these hotels during the period between 2011 and 2015 ranged from 2,125 rooms to 3,194 rooms in 2015. The number of restaurants operating in these hotels during this period range between 40 restaurants in 2011 with a capacity of 2,125 customers. In 2015 it increased to 56 restaurants, reaching a capacity of 10,899 customers (PCBS 2016). These are restaurants located within hotels, but there are dozens of special tourist restaurants located within the historical markets and in the centres of these cities (Halaika, Nakashian & Dahadha 2016).

Ḥalāl food

All restaurants within hotels or private restaurants in Palestine serve Ḥalāl food to their customers. The meat of poultry or sheep offered in these hotels and restaurants is meat slaughtered in slaughterhouses in al-Ḳuds, al-K̲h̲alīl, and Bayt Laḥm. In the process of creating Ḥalāl meat, the name of God is mentioned during the slaughter, based on the rule of the ‘good things’ or ‘ṭayyibāt’ which outlines what is lawful for Muslims to eat, which constitutes an important part of Ḥalāl food according to the Quran: “Eat then of that over which the Name of Allah has been mentioned (when slaughtered), if you truly believe in His verses” (Quran). And Allah Said: “O you who believe, eat of the good things, that are lawful, wherewith We have provided you, and give thanks to God, for what He has made lawful for you, if it be Him that you worship.” The Prophet Mohammed (peace be upon him) said: “O people, Allah is ṭayyib (pure and good) and He accepts only what is ṭayyib. Verily, Allah has commanded the believers as He commanded His Messengers. Allah said: O Messengers!, Eat of the Tayyibat and do righteous deeds. Verily, I am well-acquainted with what you do.”

Eating Ḥalāl food and living a Ḥalāl lifestyle is a prerequisite for Allah to respond to the prayer of Muslims, and according to Islam, Allah does not respond to the person who lives a Ḥarām (the opposite of Halal) lifestyle and eats Ḥarām food. In the Muslim Hadiths, The Prophet makes “mention of travelers who travel for a long period of time. In the writings, an example is given of a traveler with disheveled hair who is covered in dust. The traveler lifts his hand towards the sky and thus makes the supplication: ‘My Rubb! My Rubb!’ But his food is unlawful, his drink is unlawful, his clothes are unlawful and his nourishment is unlawful, how can, then his supplication be accepted?”

The vegetables and fruits offered in these restaurants and hotels are produced in the Palestinian land in Al-K̲h̲alīl, Bayt Laḥm, Jericho, or the northern Palestinian governorates, which provide the Palestinian market with the freshest vegetables and fruits. The Palestinian farmers in these governorates apply the rules of Ḥalāl agriculture and they are also fighting and controlling their land despite the attacks of Israeli settlers on Palestinian farmers in these provinces (Al-Haq 2017).

Islamic tourism phenomenon in Palestine

The phenomenon of Islamic tourism was not prevalent before 2011, the absence of which may be related to the instability that followed the al-Aqsa Intifada in October 2000, and the Fatwas issued by Muslim scholars forbidding visits to al-Ḳuds, and the West Bank under Israeli occupation. But since 2011 this phenomenon has become remarkable and the cities in the West Bank are witnessing an influx of tourists from Muslim countries (see the previous section for numbers of Muslim tourists between 2011 and 2015). In an interview conducted by Ma’an News Agency in June 2013 the Palestinian Tourism Minister Rula Maa‘yaa said: “Islamic tourism to Palestine began late last year (2012), and was increased day after day, especially with the President’s calls and the ministry’s contacts with Islamic countries, to encourage its residents to visit the Palestinian cities” (Ma’an New Agency 2013). It seems that the speech of Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas at the international conference held in Doha, Qatar, on 26–27 February 2012, in which he called upon Arabs, Muslims, and Christians to visit Jerusalem in order to preserve the Arab and Islamic character of the city, has resonated in many Arab and Islamic countries such as Turkey, Malaysia, Indonesia, Jordan, and Morocco. During the conference, Abbas discouraged countries from continuing a boycott of tourism to the area, declaring the importance of:

encourage[ing] all who can, especially our brothers from the Arab and Islamic countries, as well as our Arab, Muslim and Christian brothers in Europe and the United States to visit al-Ḳuds. This move will have its political, moral, economic and humanitarian repercussions. al-Ḳuds belongs to us and we all have no one to prevent us from reaching it. The influx of crowds and the congestion of its streets and holy sites will strengthen the steadfastness of its citizens and contribute to the protection and consolidation of the identity, history and heritage of the city targeted by the eradication. The occupiers will remember that the issue of al-Ḳuds is the cause of every Arab, every Muslim and every Christian. We confirm here that the visit of the prisoner is a support for him and does not in any way mean normalization with the prisoner.

(Abbas 2012)

On 18 April 2012, Prince Ghazi bin Muhammad, the King Abdullah II’s personal adviser and head of the Royal āl al-Bayt Society, and the former Egyptian Mufti Ali Gum‘a visited Jerusalem together (Al-Jazeera 2012). The call of the Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas to encourage Arabs, Muslims, and friends to visit al-Ḳuds had led to a debate among Muslim scholars on the issue of Muslims and Arabs visiting al-Ḳuds under Israeli occupation. In opposition to the Palestinian President’s call to visit al-Ḳuds, the chairman of the International Union of Muslim Scholars (IUMS), Dr Yusuf Qaradawi, has issued a fatwa prohibiting the visit to al-Ḳuds to non-Palestinians, in order to “not legalize the Israeli occupation in the city” (Donia al-Watan 2012). The Palestinian official position remained constant and called for intensifying visits by Muslims to al-Ḳuds, al-K̲h̲alīl, and Bayt Laḥm, as well as the Jordanian position. Therefore, the two sides held a series of activities: On 31 March 2013 King Abdullah II and Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas signed a “trusteeship and sovereignty” agreement, which continued Jordan’s right to “guardianship” and “defense of al-Ḳuds and holy sites” in Palestine (Jordanzad 2013).

Between 28 and 30 April 2014, an international conference concerning Jerusalem was held in Amman, entitled “al-Tariq ‘ila al-Ḳuds\The Road to Jerusalem”, under the patronage of Jordan’s King Abdullah II, the Jerusalem Committee for Jerusalem Affairs, and the Arab Parliament. The subject of the discussion was Israeli violations at al-Aqsa Mosque and ways of assisting Palestinians living in Jerusalem. The conference was attended by Muslim and Christian clerics: the former Egyptian Mufti, Ali Gum‘a; Mufti al-Ḳuds, and the Palestinian territories, Sheikh Muhammad Hussein, Palestinian Minister of Religious Affairs Mahmoud al-Habash, Jordanian Minister of Endowments, and others, as well as politicians (Al-wakeel News 2014). At the end of the conference, the participants issued a fatwa permitting Muslims to visit al-Aqsa, but restricting it only to Palestinian visitors or to Muslim visitors with citizenship from countries outside the Muslim world. The fatwa actually cancels the earlier fatwa issued by al-Qaradhawi. Palestine and Jordan encouraged all Muslims to visit al-Aqsa Mosque, but the fatwa issued in the conference “The Road to Jerusalem” does not permit visits to al-Ḳuds to all Muslims, it is includes “Palestinians … regardless of their nationalities” and “Muslims with passports from countries outside the Muslim World” could visit al-Ḳuds, as long as they didn’t financially aid the “occupation” (Al-wakeel News 2014).

During the 22nd season of the International Islamic Fiqh Academy (IIFA) which was held in Kuwait between 22 and 25 March 2015, the IIFA issued a decree stating that visiting al-Ḳuds is a permissible and recommended act and it is obligatory to help the city and its people (OIC 2015a). The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) general secretary selected al-Kuds as the Capital of Islamic Tourism for 2015 at the eighth conference of Ministers of Tourism held in Banjul, Gambia, between 4 and 6 December 2013. The Ministry of the Awḳaf and Religious Affairs, as well as the Palestinian Ministry of Tourism, continued to coordinate with the Ministries of the Awḳaf in the Islamic countries and also with the OIC to encourage Muslims to visit al-Ḳuds, al-K̲h̲alīl, and Bayt Laḥm. Between 14 and 15 June 2015, the Palestinian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities hosted the United Nation World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) International Conference on Religious Tourism in Bayt Laḥm (Isaac 2015). It was the first time that the UNWTO organised a conference in an observer member state. The attendants of the conference included international ministers, tourism professionals, and tourism academics. At the conference, the Palestinian private sector presented the services it offered through an exhibition alongside the meeting. The conference was very important for Palestine, the audience was aware of the potential of the tourist sector in Palestine, which is witnessing an increase in the number of hotels and a remarkable development in the services provided, which include traditional crafts, transportation and services of tourist offices, tourist police services, and qualified tourist guides from Palestinian universities and colleges.

The places Muslim tourists can visit: al-Ḳuds, al-K̲h̲alīl, and Bayt Laḥm

There are many places Muslims can visit in al-Ḳuds especially within the Aqsa Mosque area, e.g. the Dome of the Rock, the Dome of the Prophet, the Dome of Ascension, the Dome of the Chain, the Gate of Mercy, the Gate of the Tribes and the Gate of the Prophet, and also there are places outside the Aqsa Mosque to visit such as the Mount of Olives. Muslims in al-K̲h̲alīl can visit Masjid Ibrahim: the Cave of Patriarchs, Bir Haram Ar-Rameh (Ramet Al-khalil\Mamre), the Old City of al-K̲h̲alīl, al-K̲h̲alīl refugee camps, al Aroub Refugee Camp, and Fawwar. In Bayt Laḥm, Muslims can visit the Church of the Nativity and Omar Mosque, the Old City of Bayt Laḥm, and the refugee camps within the city.

Despite the historical and religious status of the country, Palestine has one of the lowest numbers of visitors in comparison to other countries in the region, which receive millions of tourists every year. Therefore, its regional market has remained extremely low and very weak even amid global increases in the number of tourists. During 2015, about 2,799,397 tourists visited Israel/Palestine (JIIS 2017) out of 53 million tourists who visited the Middle East region (UNWTO 2016). Al-Kuds, al-K̲h̲alīl, and Bayt Laḥm are three major holy cities in Palestine. These cities have long been a destination for travellers from all over the world, because of the religious-cultural status of their holy sites. These cities also have the lowest number of both non-Muslim and Muslim tourists in comparison with other cities in the region.

The main obstacles facing tourism in Palestine are the continued Israeli occupation of the Palestinian territories, where Palestinians cannot exploit the abundant amount of tourist resources in their cities, which are under Israeli control, such as Jerusalem and Hebron. For example, in 1997 the al-K̲h̲alīl Protocol divided the city of al-K̲h̲alīl into two parts. H1, comprising around 80 per cent of the city under full control of the Palestinian Authority, and H2, comprising around 20 per cent and including the Old City and the most affected areas, under the control of Israel. The Palestinian Authority has control over civil affairs, except in the settlement, and Israel controls the security affairs of both H1 and H2 (Clarke 2000; Isaac et al. 2016).

Israel continues to control the tourism sector in general by controlling the crossings and borders and stringently controls the numbers of tourists coming to Palestinian cities. Efforts must be intensified in order to make Palestinian cities independent tourist destinations, which would have a positive impact on the development of these cities economically, due to the likely increase in private sector investments in tourism (Isaac et al. 2016). The lack of Muslim and non-Muslim tourism in Palestinian cities has extreme negative effects on the GDP of these cities, and severely impacts the operational capacity, including employment opportunities, investments, development, and so much more.

Conclusion

This chapter deals with Islamic and Ḥalāl tourism in three Palestinian cities: al-Ḳuds ‘Jerusalem’, al-K̲h̲alīl ‘Hebron’, and Bayt Laḥm ‘Bethlehem’. This chapter presented the tourism situation in these Palestinian cities and the religious value of visiting the three cities for Muslims according to Islamic teaching (S̲h̲ariah law) and Islamic cultural heritage.

Islamic tourism is an activity, experience, occasion, or purpose to visit historical places, heritage, culture, arts, business, health, education, Islamic history, sports, shopping, or any other human interests but on condition of Shariah compliance. Also, in Islamic tourism, people travel for their vacation and recreation and to be satisfied with Allah. Thus, tourism is a section of human life which does not contradict the main theme of Islam. Islamic and Halāl tourism is indeed a promising market for the tourism industry in Palestine. One of the main opportunities for the tourism sector in Palestine consists of the need of the Muslims conducting the Ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲ rites to visit the al-Aqsa Mosque, in Jerusalem as a complementary part for their Ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲, which could open the potential for millions of visitors to Palestine per year. Islamic tourism is a recent phenomenon in the theory and practice of global tourism industry. Traditionally Islamic tourism was often associated with Ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲ and ʿumra only. However, recently there has been an influx of products and services designed specifically to cater to the business and leisure-related segments of Muslim tourists across the globe. Islamic tourism remains an emerging niche market with 108 million Muslim travellers, accounting for 10 to 12 per cent of the global tourism sector.

References

Abbas, M. (2012) ‘Jerusalem: Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas speech’, International Conference on Jerusalem, 26–27 February, Doha: Qatar. [online] Available at: http://qatarconferences.org/jerusalem/arabic/palestine (accessed 15 June 2017).

Abed Rabo, O. (2012) Jerusalem During the Fāṭimid and Seljūq Periods: Archaeological and Historical Aspects. PhD. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University.

Al-Emarat alyoum. (2015) ‘Saudi Arabia: 6 million Muslims perform umrah in 1436 AH’. (Arabic) [online] Available at: www.emaratalyoum.com/life/four-sides/2015-11-23.1.843206 (accessed 20 July 2017).

Al-Haq. (2017) ‘Settlements and settler violence’. [online] Available at: www.alhaq.org/advocacy/topics/settlements-and-settler-violence (accessed 10 August 2017).

Al-Jazeera. (2012) ‘Alwilayat al‘urduniyat a‘laa ‘awqaf al-quds’. [online] Available at: www.aljazeera.net/news/reportsandinterviews (accessed 22 April 2012].

Al-Jazeera. (2015) ‘The number of tourists in Israel decreased by 16%’. [online] Available at: www.aljazeera.net/news/ebusiness (accessed 17 June 2015).

Al-Jazeera. (2017) ‘UNESCO declares Hebron old city a World Heritage Site’. [online] Available at: www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/07/unesco-declares-hebron-city-world-heritage-site-170707100548525.html (accessed 30 August 2017).

Al-Muqaddasī, M.b., Aḥmad b. and Al-Bannāʾ A.B. (1906) Aḥsan al-taqāsim fī maʿrifat al-aqālīm, Leiden.

Al-Musabbiһ̣ī, ‘Izz al-Mulk Muhammad Ibn Ahmad. (1980) Akhbar Msr fi sntin (414–415 h.), Msr./Egypt.

Al-wakeel News. (2014) ‘Final statement of the road to Jerusalem Conference’. (Arabic) [online] Available at: www.alwakeelnews.com/article/95705 (accessed 16 August 2017).

Al-Wāsiṭī, Muhammad b. Ahamad, Abū Bakr al-Wāsiṭī. (1979) Faḍāʾil al Bayt al-Muqaddas (Ed. I. Hasson), Jerusalem.

Athaminah, K. (2013) Al-Quds wa-al-Islam: Dirasah fi qadasatiha min al-manzur al-islami. Beirut: Institute of Palestinian Studies.

Battour, M. and Ismail, M.N. (2016) ‘Halal tourism: Concepts, practices, challenges and future’, Tourism Management Perspectives, 19 (B): 150–154.

Clarke, R. (2000) ‘Self-presentation in a contested city: Palestinian and Israeli political tourism in Hebron’, Anthropology Today, 16 (5): 61–85.

Crescent Rating. (2015) Muslim/Halal Travel Market: Basic Concepts, Terms and Definitions. Singapore: Crescent Ratings.

Dinar Standard. (2012) ‘Global Muslim lifestyle tourism market: Landscape & consumer needs study’. [online] Available at: https://www.slideshare.net/DinarStandard/global-muslim-lifestyle-tourism (accessed 18 June 2017).

Donia al-Watan. (2012) ‘Al-Qaradawi‘s fatwa raises divisions among scholars’. [online] Available at: https://www.alwatanvoice.com/arabic/content/print/255764.html (accessed 3 June 2012).

Elad, A. (1995) Medieval Jerusalem and Islamic Worship: Holy Places, Ceremonies, Pilgrimages. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Elad, A. (1996) ‘Pilgrims and pilgrimage to Hebron (al-K̲h̲alīl) during the early Muslim period (6389–1099)’. In B.F. Le Beau and M. Mor (eds) Pilgrims and Travelers to the Holy Land, Studies in Jewish Civilization. Omaha, NB: Creighton University Press, 21–61.

Esposito, J. (ed.) (1999) The Oxford History of Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Haines, G. (2017) ‘10 surprising destinations where tourism is booming in 2017’. The Telegraph, 27 September. [online] Available at: www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/news/surprising-countries-where-tourism-is-booming-in-2017/ (accessed 20 August 2017).

Halaika M., Nakashian S. and Dahadha A.I. (2016) Development of Tourism Sector in East Jerusalem. Jerusalem and Ramallah: Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS).

Ibn al-Murajja, Abu ‘lMa‘ali, al-Musharraf b. al Murajja. (1995) Faḍāʾil Bayt al-Maqdis wa-‘I-Sham wa –‘I-Khalil. (Ed. O. Livne), Shafa-Amro.

Isaac, R.K. (2015) ‘Understanding religious tourism—motivations and trends’, paper presented at the UNWTO International Conference on Religious Tourism: Fostering Sustainable Socio-economic Development in Host Communities, Bethlehem, State of Palestine, 15–16 June 2015.

Isaac, R.K. (2017) ‘Taking you home: The Masar Ibrahim Al-khalil in Palestine’. In: C.M. Hall, Y. Ram and N. Shoval (eds) The Routledge International Handbook of Walking. London: Routledge, 172–183.

Isaac, R., Hall, C.M. and Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (eds) (2016) The Politics and Power of Tourism in Palestine. Abingdon: Routledge.

Jaelani, A. (2017) ‘Halal tourism industry in Indonesia: Potential and prospects’, International Review of Management and Marketing,7 (3). [online] Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2899864

Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies (JIIS). (2017) Statistical Yearbook of Jerusalem, No. 31, 2017 Edition. Chapter XI—Tourism. Jerusalem.

Jordanzad. (2013) ‘The Jordanian custodianship of the Alqsa: Return the unity of the two Banks’. (Arabic). [online] Available at: www.jordanzad.com/index.php?page=tag&hashtag=مسجد&pn=233 (accessed 6 April 2013).

Lieberman, M. (2015) World-best-cities. [online] Available at: www.travelandleisure.com (accessed 4 August 2015).

Ma’an News Agency. (2013) ‘Islamic tourism’. (Arabic) [online] Available at: www.maannews.net/Content.aspx?id=603164 (accessed 9 June 2013).

Ma’an News Agency. (2017) ‘Muslims from Southeast Asia enter into a state of iḥram in al-Aqsa to perform “Umra”’. (Arabic) [online] Available at: https://maannews.net/Content.aspx?id=909291 (accessed 27 May 2017).

Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). (2015a) ‘Visiting Al-Quds permissible and recommended: International Islamic Fiqh Academy issues decree’. Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) Journal, 29: 45.

Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). (2015b) International Tourism in the OIC Countries: Prospects and Challenges. Ankara: OIC.

Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). (2017) ‘Member states’. [online] Available at: www.oic-oci.org/states/?lan=en (accessed 4 May 2017).

Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) 2011–2016. Ramallah: MOTA.

Paltoday. (2015) ‘Jerusalem tourism gets lifeline from unlikely source: Muslim visitors’. (Arabic) [online] Available at: https://paltoday.ps/ar/post/234292 (accessed 7 June 2015).

United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). (2016) UNWTO World Tourism Barometer 2016. Madrid, Spain: UNWTO.