Introduction

Tunisia was a pioneer for Muslim countries entering the global tourism market. The Tunisian tourism industry was developed during the Bourguiba presidency (1957–1987), according to European demand, and soon became a pillar of the national economy. Tunisia currently specialises in coastal tourism, offering all-inclusive packages at seaside resorts (Klabi 2014; Mansfeld & Winckler 2015). Long before the fall of Ben Ali during the 2011 Tunisian Revolution, however, the industry suffered many disparities in regional tourism development, poor product quality, and loss of competitiveness. More recently, the 2015 terrorist attacks targeted tourists at Bardo National Museum and Sousse resorts, which had a dramatic impact on Tunisia’s reputation as a travel destination. Many have observed that beyond the need for regaining notoriety as a safe destination, new initiatives are needed to revitalise the industry. Considering the sector’s historical development and current status, as well as the rising global interest in Muslim tourists, the present study discusses the possibility of transforming Tunisia into a Muslim-friendly travel destination, attracting tourists from underexploited markets.

The number of tourist destinations marketed as ‘Muslim-friendly’ is growing worldwide, and so are the products designed to meet the needs and expectations of Muslim tourists. For example, in several Muslim countries, such as Turkey and the UAE, ‘Sharia-compliant’ hotels are emerging (Eid & El-Gohary 2015). The popularity of such concepts as Islamic or halal tourism is also steadily growing (Scott & Jafari 2010). Despite the degree of vagueness often surrounding such concepts (Hamza, Chouhoud & Tantawi 2012; Henderson 2010), there is increasing interest towards Muslim tourists for a variety of geopolitical, demographic, and economic reasons (see Stephenson, Russell & Edgar 2010; Prayag & Hosany 2014; Stephenson & Ali 2010). During Ben Ali’s regime (1987–2011), most disregarded the potential of the halal market (Sarra 2012), but a debate on halal products (including tourism) emerged after the Revolution (see La Presse 2011, 2012).

Based on field research, the present study discusses and expands upon two previous studies on the tourism of Djerba and Nabeul–Hammamet, authored by Carboni, Perelli and Sistu (2014, 2017). As in the previous studies, the objective of the present research is to investigate the perceptions of key informants in these two areas, crucial to the Tunisian tourism industry, concerning the possibility of developing Muslim-friendly tourism products.

Tunisian tourism: then and now

As a pioneer in exploring the potential of Muslim-friendly tourism development, Tunisia supported its tourism industry through a state initiative based on a clear top-down strategy (Poirier 1995; Bouzahzah & El Menyari 2013; Di Peri 2015). The sector’s growth has been remarkable and relatively fast, both in terms of tourist accommodation capacity and arrivals (Table 12.1).

Table 12.1 Tunisia: bed capacity and tourist arrivals, 1965–2010

| Year | Bed capacity | Tourist arrivals |

|---|---|---|

| 1965 | 8,726 | 165,840 |

| 1971 | 41,252 | 608,206 |

| 1981 | 75,847 | 2,150,996 |

| 1991 | 123,188 | 3,224,015 |

| 2001 | 205,605 | 5,387,300 |

| 2010 | 241,528 | 6,902,749 |

Source: ONTT, Office National du Tourisme Tunisien, 2011.

Created in the 1960s, the five-year National Development Plan has described investments, infrastructure development, and quantitative growth objectives for the sector. During the first stages of development, the Tunisian government operated as planner, owner, and manager of the main resorts. As reported by De Kadt (1979), around 40 per cent of Tunisia’s tourist accommodation capacity between 1960 and 1965 was created through direct government initiatives. Although private initiatives emerged in the 1970s, the state held large control over the industry. At the end of the 1980s, a series of liberalisation policies were promoted by the national authorities through the 1987–1991 National Development Plan, marking the consolidation of Former President Ben Ali’s control over the tourism sector, which lasted until the regime changed in 2011. (For an impressive overview of the role that firms owned by Ben Ali played in the Tunisian economy and their link with market entry regulations, see Rijkers, Freund & Nucifora 2017).

For decades, Tunisia has specialised in providing all-inclusive packages at seaside resorts. Starting in the 1970s, tourism growth in coastal areas planned by the Tunisian State showed dramatic impacts related to regional disparities, water scarcity, adverse working conditions, and economic integration with traditional sectors (Sethom 1979; Poirier 1995; Hazbun 2008; Miossec & Bourgou 2010). Social and cultural disruption caused by tourism development was also reported; in Djerba, for example, a ‘moral’ lecture on tourism development described it as a product of European hegemony that questioned key Tunisian values and identity issues (Bourgou & Kassah 2008).

In its initial stages, ‘Eurocentric’ Tunisian tourism became overdependent on a few markets (Poirier 1995), with consequences stemming from international flow variations and tour operator intermediation (Miossec 1999; Di Peri 2015). Several European countries and Tunisia’s Maghreb neighbours, specifically Algeria and Libya, have always been the country’s core markets for tourism, which were strongly impacted by the events of 2015 (Mansfeld & Winckler 2015). In 2010, before the Revolution, Europeans and Maghrebians accounted for over 55 per cent and 42.5 per cent of tourist arrivals, respectively (ONTT 2012). Over the last few years, due to internal instability, Libyan arrivals have decreased. This reduction in arrivals, which mainly affected southern coastal destinations close to the Libyan border, was partially mitigated by a rise in Algerian tourists.

Maghrebians and Europeans traditionally differ in their travel motivations. Coastal tourism has always been the only reason that Europeans visit Tunisia, while a break from less safe and/or more restrictive social environments lies at the base of Maghrebians’ motivations. Maghreb tourism activities also include shopping or health care, and over the last decade, Tunisia has emerged as a medical tourist destination, especially the central-southern part of the country. Like any stereotypical ‘VIP experience’ of cosmetic surgery, Tunisia’s marketed ‘beautyscape’ includes a (sometimes uneasy) cohabitation between Western patient–travellers seeking low-cost services—mostly unaware of the geopolitical context—and Libyans escaping from war zones or other Maghreb visitors (Holliday, Bell, Cheung, Jones & Probyn 2015).

Europeans and Maghrebians also differ in their accommodation choices. Europeans account for the vast majority of nights spent in hotels and other registered accommodation. On the contrary, visitors from North African countries traditionally prefer holiday houses and unregistered accommodation. In 2010, for example, only 19 per cent of North African tourists stayed in hotels (ONTT 2012), while 80 per cent of hotel guests in 2000–2009 were Europeans (Institut Arabe des Chefs d’Entreprises (IACE) 2011).

For a long time, Tunisia has enjoyed its reputation as a safe destination. The tourism sector, called a ‘developmental miracle’ by Ben Ali’s regime (Di Peri 2015), supported the discourse surrounding Tunisia’s status as a stable, open Muslim country (Hazbun 2008; Hibou 2011). However, after 9/11 and the events that followed, such as the 2002 terrorist attack in Djerba, the country’s international reputation began to decline (Al-Hamarneh & Steiner 2004; Steiner 2010). The 2011 regime change coincided with the apex of the stagnation in Tunisia’s transition to a mature coastal destination (IACE 2011). Regional instabilities and security bias further impacted the tourism industry, leading to a crisis that is still unresolved as of 2017, despite slow recovery of European visitor flows.

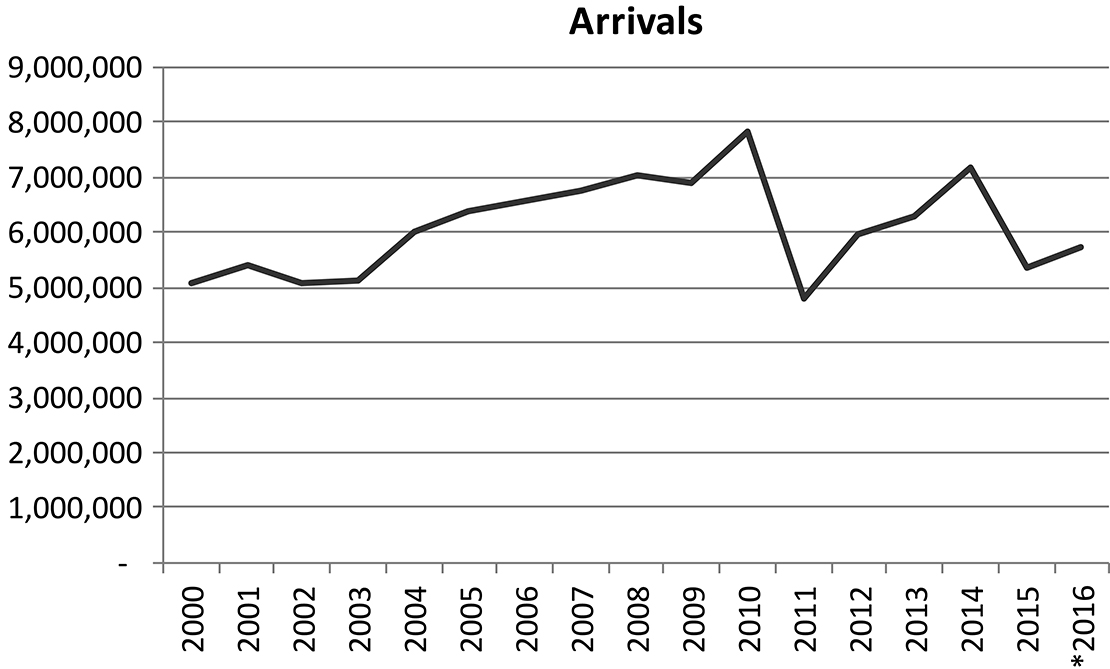

The effects of the Arab Spring uprising on the Tunisian tourism industry have also been investigated. Econometric estimations of international tourist arrivals indicated that the pre-uprising decline in the tourism sector would probably last due to its post-uprising reduction in competitiveness (Perles-Ribes, Ramón-Rodríguez, Moreno-Izquierdo & Torregrosa Martí 2018). In 2010, Tunisia received almost 7 million international tourists, declining to about 4.78 million in 2011. Similarly, overnight stays decreased from 35.5 million in 2010 to 20.6 million in 2011 (ONTT 2012) (Figures 12.1 and 12.2). Although the Tunisian tourism industry slowly recovered during the 2012–2014 seasons, industry performances returned to 2011 levels after the 2015 attacks at Bardo National Museum in Tunis, leaving 20 dead, and Sousse beach, leaving 38 dead. The industry was mostly affected by a mix of national attacks against tourists and international crises (i.e. the arrival of Syrian and Libyan refugees) occurring in 2015. Consequently, as demonstrated by Cirer-Costa (2017), several North Mediterranean markets rose in demand as they were perceived as destinations with relatively reduced risk and decent security.

Figure 12.1 Tunisia: overnight stays, 2000–2016

Source: ONTT, 2012, 2017.

Note: * Not definitive.

Figure 12.2 Tunisia: tourist arrivals, 2000–2016

Source: ONTT, 2012, 2017.

Note: * Not definitive.

Security issues are not the only challenges currently affecting Tunisia’s tourism. Structural loss of competitiveness, ageing buildings, quality issues, and low availability of capital for indebted hotels represent the consolidated issues plaguing the hotel sector. (For an analysis of Tunisian hotel competitiveness, see Khlif 2006; Errais 2015; Di Peri 2015.) Furthermore, the sector is characterised by an overdependence on a few markets and a single tourism segment: coastal tourism.

Despite efforts made towards diversifying its tourism products, Tunisia has never achieved a strong alternative to coastal tourism. For example, heritage tourism—which commonly occurs in mass coastal tourism—has always been complementary to package vacations, as evidenced by seasonal and inter-annual variations in visitor statistics. Accordingly, the Tunisian tourism industry has participated in the national memory for decades, building, producing, and reproducing a ‘mythological heritage’ (Perelli & Sistu 2013). The Archaeological Site of Carthage, for example, represents the dominant discourse of a Mediterranean and African identity that overwhelms the Arab-Islamic past. Middle-class Western and Maghreb heritage tourism legitimised the official narrative of national identity, with little to no space left for counter-memories and alternative narratives of the past (Larguèche 2008).

Islam has never played a significant role in developing Tunisia’s tourism sector, as Former President Bourguiba imposed a clear separation between religion and the state (Tessler 1980). A slight shift occurred with Ben Ali, who ‘reintroduced the idea of Islam as a specific and crucial element of Tunisian culture, history and identity’ (Haugbølle 2015: 324). Regardless, no significant changes occurred, and Islam never influenced the sector’s development. During Ben Ali’s regime, the potential of the halal market was generally ignored (Sarra 2012), and it was not until just after the Revolution that a debate on halal products and tourism emerged (see La Presse 2011, 2012).

Ben Ali’s fall—and the unprecedented freedom of speech that Tunisians now enjoy—has allowed for increased public debate on several issues. For example, a debate on ‘Tunisianity’ entered the marketing domain after 2011, with profound effect (Touzani, Hirschman & Smaoui 2016). Public debate on Tunisian identity at the crossroads of Arab–Muslim, French–Western and other heritages (e.g. Berber, Sub-Saharan and Jewish) is not new (Pouessel 2012), but today’s discourse also considers the role of Turkish heritage and, at the same time, its former colonial power (as the Ottoman Empire) and current reference in the Middle East.

This unprecedented debate has also given room to discussion about the potential of the halal market. Post-revolutionary governments have been very careful to reassure mass tourism operators that there is no risk of Islamisation. At the Sixth International Conference of the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), held in Djerba in April 2012, Former Prime Minister Hamadi Jebali declared that ‘there is no halal or haram tourism, there’s simply tourism’ (Ben Nessir 2012). More recently, during the summer of 2017, Minister of Tourism Selma Elloumi confirmed that halal tourism does not officially exist in Tunisia as a separate niche from existing family tourism products (Krimi 2017).

The Muslim-friendly option

This research focuses on two leading Tunisian destinations, Djerba and Nabeul–Hammamet, which together account for 33 per cent of hotels and over 40 per cent of tourist accommodation capacity across the nation. Djerba is the largest island of North Africa (514 km2) and, since the 1960s, has been one of the most popular Tunisian destinations for mass coastal tourism. The eastern coast hosts almost all of Djerba’s tourism infrastructure. Data on the island show the same trends towards stagnation and decline observable at the national level, for the same reasons mentioned earlier and due to the 2002 bomb attack on the El Ghriba Synagogue. Before the 2011 crisis, European tourists accounted for over 87 per cent of the 980,000 hotel arrivals, while Libyans, who represented the largest portion of non-European visitors, made up only 4.5 per cent (ONTT 2011). With respect to the present research questions, it is important to note that Jewish pilgrimages and related heritage attractions are consolidated tourism products in Djerba. Strategies for bridging the Jewish minority with Tunisia’s tourism, heritage, contemporary history, and national identity building are well observable, such as the Ghriba Synagogue pilgrimage. This pilgrimage and the related festival are top tourist attractions and icons of Tunisian religious tolerance (Carboni et al. 2014; Perelli & Sistu 2013; Boussetta 2018).

The Cap Bon Peninsula hosts the Nabeul–Hammamet area, an almost entirely urbanised coastline that is one of the leading tourist destinations in the country. Like everywhere else in the country, the fall of Ben Ali’s regime affected Cap Bon: tourist overnight stays decreased from 9.4 million in 2010 to 6.1 million in 2013. Hotel customers are traditionally Europeans, with Algerians and Libyans accounting for less than 5 per cent of total hotel stays.

The present research expands upon two previous studies by Carboni et al. (2014, 2017) conducted in the Djerba and Nabeul–Hammamet areas, applying the same methodology. As such, the present research is based on a qualitative research method that incorporates the consultation of secondary sources and interviews. The primary data (semi-structured interviews) were collected between 2012 and 2017 from 34 men and 13 women across several ages. The interviewees included tourism professionals, non-profit organisation representatives, local administrators, owners of tourist accommodation facilities, local and national tourism-related agencies, and local academics.

The interview structures were the same for both areas. The first section started with the interviewees’ opinions about the current state of the destination’s tourism sector. The focus then shifted to the relationship between the local population and tourists, with some questions about the impact of tourist presence. Finally, the rising interest in Muslim-friendly tourism was investigated via individual opinions and knowledge of the phenomenon’s main characteristics, including questions concerned with the interviewees’ opinions on the potential of halal tourism for the Tunisian market. The presentation of the results follows the same structure of the interview questions.

Security issues emerged as one of the main themes, mainly related to the 2011 events. According to several interviewees, European and Gulf State mass media overemphasised the security issues and represented the Revolution in ways that greatly compromised Tunisia’s reputation as a safe tourist destination. Some interviewees stated that, according to their personal beliefs, fearful discourses were intended to harm the country. The interviewees did not underestimate the risks related to Islamic terrorism, such as the attacks at Bardo National Museum and the coastal Sousse resorts. However, they did blame international mass media for their excessive emphasis on instability and insecurity within Tunisia.

The interviewees clearly recognised the main problems in the tourism industry, as most of the long-lasting topics of national debate over industry performances emerged during the interviews. Several interviewees mentioned the low quality of services, market positioning, low-cost mass products, high seasonality, and lack of differentiation as the sector’s most critical weaknesses. Regarding Djerba, concerns emerged over the environmental and social effects of mass tourism development and the unequal distribution of tourism-related benefits among the local communities. The island’s maisons d’hôtes (guest houses) were indicated by many interviewees as a valid solution for increasing the number of structures owned by local entrepreneurs and the interaction between tourists and the local population. Local ownership would also provide greater income to the community. Other interviewees described the potential of the maisons d’hôtes as slightly controversial in terms of quality, health regulations, and safety. Furthermore, the interviewees indicated that the integration of this kind of accommodation with traditional operators, such as travel agencies, is still underdeveloped.

The cohabitation of tourists from different countries and faiths was cited as a well-established fact in Tunisia. The interviewees considered this to be a consequence of Tunisia’s history of hospitality, a result of the long-term cohabitation of Arab, Jewish, Berber, and European communities. Regarding Djerba, several interviewees described hospitality as a value that exceeded nationality or religion and a very local cultural trait. The annual Jewish pilgrimage to Ghriba Synagogue is commonly referred to as a symbol of the country’s religious tolerance, both by Tunisian residents and the government’s discourse on Tunisianity (Perelli & Sistu 2013).

Regarding the cohabitation of tourists with different origins and backgrounds, the interviewees tended to focus on Europeans and Maghrebians, specifically Algerians and Libyans. Tourists from Algeria and Libya, as mentioned earlier, have always been a significant portion of international arrivals. This is surely related to their geographical proximity as well as to a consolidated tradition of transnational mobility between these neighbour countries, as stated by some interviewees. The interviewees also noted that the interactions between Europeans and Maghrebians has always been limited, as the latter tend to stay in unregistered facilities (e.g. vacation homes), whilst the former prefer hotels and other registered accommodation. A small minority of relatively wealthy Maghrebians, mainly Libyans, may share tourism facilities with Western tourists, with no apparent conflicts.

Most disparate were the interviewees’ opinions about tourists from the Gulf countries. Despite the low numbers of international arrivals from the Gulf countries (e.g. just 15,000 Gulf tourists visited Tunisia in 2014) (Agence Anadolu 2015), a very strong perception of the differences between Gulf tourists and their Arab neighbours emerged among the interviewees. Nearly every interviewee who mentioned Gulf tourists highlighted that they can be controversial. On the one hand, they tended to have a high spending limit; on the other hand, their interactions with locals are not necessarily positive. Some interviewees reported issues with Gulf tourists’ attitudes towards nightlife, prostitution, and respecting local employees.

A sense of caution appeared among the interviewees regarding the possible impacts of the growth of the Muslim tourist market share. According to some interviewees, Maghreb potential as the main component of intra-Arabic tourism has been undervalued; Maghrebians may positively affect local tourism and provide a sound solution for reducing the majority share of European markets. This demonstrates a pragmatic point of view, as the overly simplistic ideal of easy cohabitation was discarded. For example, interviewees who worked with tourists from Iran, a non-Arab Muslim country, perceived them to be a promising niche, and local agencies and tour operators cited that they were generally good customers.

The interviewees were relatively well informed about the worldwide growth of tourism products that considered Muslim religious sensitivities. This awareness appeared to be influenced by the current national debate on halal products. Interviewees more directly involved in marketing declared their interest towards the topic as one that was connected to the need for new markets. Several interviewees suggested a ‘technical’ approach to this issue, underlining the potential of such products in terms of new markets and product diversification. For example, many hotel managers and tourism professionals indicated Turkey as a successful model for this approach. The main assets of the Turkish model include the variety of tourism services and products, the integration of Western and Muslim tourism, fair prices, and excellent quality. Nevertheless, the interviewees were enthusiastic about and open to Muslim-friendly products, conceiving them as a tool for diversifying Tunisian tourism but not as the only products the country should offer.

The interviewees’ perceptions towards the potential of products closer to Muslim religious sensibilities were not unanimous, however. Possibly due to the national debate over the role of Islam in post-revolutionary Tunisia, the interviewees expressed a sensitivity towards differentiating tourists based on religion. Some interviewees were worried about the idea of segregating tourists of different faiths, as such actions would somehow threaten the Tunisian tradition of multicultural cohabitation. The political implications behind the development of halal tourism products and the risk of polarisation in Tunisian destinations were also reported, such as regulations on alcohol consumption or gender segregation. Furthermore, among the interviewees who did not exclude such future developments as a viable tourism niche was recognition that there were several obstacles to its feasibility. The most-mentioned element concerned the very same nature of contemporary Tunisian mass tourism, especially regarding demand. According to the interviewees, today’s tourists are not interested in a different product, especially those that are intended to target intra-Arab consumers. In both Nabeul–Hammamet and Djerba, there is a perception that tourists are motivated to take advantage of a more liberal climate in terms of nightlife and tourist behaviour. This is especially the case for Libyan visitors to Djerba.

With respect to supply, the interviewees believed that deeply rooted criticisms of the Tunisian tourism industry would strongly restrict halal tourism development. Lack of financial resources and difficulties in credit access would limit hotels’ abilities to alter their facilities according to halal tourism needs (e.g. gender segregation in sports and spa facilities or separate prayer rooms). Due to such restraints, several interviewees remarked that investors should support the improvement and diversification of the existing supply, rather than create and bolster demand for Muslim-friendly tourism.

Finally, the growing attention towards ‘local development’ emerged during the interviews, and several interviewees stressed the need for reducing social and environmental impacts and increasing the benefit for local communities. Some interviewees described this local turn in existing tourism, including offering real experiences of material and immaterial local heritage to tourists, as the real priority.

Conclusion

An accurate overview of the current Tunisian tourism industry reveals how any fear of Islamisation is unfounded. Despite the regional challenges and the emerging post-revolutionary role of political Islam, Tunisia is still not too keen on religious extremism in any form. Interviewees, especially the younger ones, involved in the post-revolutionary debate on the role of political Islam in Tunisia somehow associated Muslim-friendly tourism with the risk of moving backwards as a society. They feared that emphasis on religious differences in the tourism sector would eventually result in polarisation, but until now, there coexist visions over delicate issues, such as Tunisian gender norms.

On the other hand, tourism professionals expressed their approval of Muslim-friendly tourism as a differentiation tool, which is partly a consequence of the large-scale recognition of the growing presence of Muslim consumers in the international tourism market. As an example, references to Turkey as a model for tourism development is mainly connected to the nation’s ability to manage cohabitation of Muslim and non-Muslim tourists. As demonstrated by Elaziz and Kurt (2017), Muslims in Turkey integrate tourism consumption with religious norms, living a hybrid experience, the results of which still need more in-depth research.

Similar degrees of uncertainty have emerged in Tunisia regarding tourism consumption by Maghrebians (2 million Algerian tourists are expected to visit Tunisia in 2017, nearly double the number in 2016) or Tunisians living in Europe. As reported by some interviewees, inter-Arab contact between locals and tourists (e.g. Libyan tourists in southern destinations, like Djerba) is not necessarily easy. The reputation of Tunisia’s Maghreb neighbours can be worse than one would expect, stemming from the local perception that their behaviours are just as inappropriate as Westerners’. Domestic tourists also show great variability and diversity in reputation and behaviour. As underlined by Hazbun (2007, 2008, 2010), more research is needed on the role of tourism in producing and consolidating transnational, hybrid knowledge of globalisation in North Africa and the Middle East. An increased understanding of the contribution of local tourist consumption, the role of the government, the development of tour agencies, and the power of local communities in shaping contemporary tourism within the region is needed, including Tunisian development of Muslim-friendly tourism products.

In the interviewees’ eyes, the success of Muslim-friendly tourism development in Tunisia seems to be associated with the guarantee of a certain occupancy rate and adequate profits without any adverse effects on consolidated Western demand. In other words, what the present research has revealed is the need for new, local tourism development, as opposed to the moralisation of communities’ customs and social lives according to religious tradition. Tourism professionals are aware of the complexity of this issue, such as the national debate on Tunisian identity and new methods for tourism development following the mass tourism crisis. When describing tourism as part of daily life in a coastal community, the interviewees offered a Tunisian approach to Muslim-friendly tourism development. Along with the tour operators’ support, other dynamics that can contribute to a new development model for Tunisia’s tourism industry include: the integration of new narratives regarding the articulate, multifaceted history and heritage of Tunisia; the consolidation of correlated economic sectors into the tourism value chain; the cooperation between inter-Arab and domestic tourism efforts, with integration of non-Muslim demand; and increased design and diversification of local tourism experiences and products.

References

Agence Anadolu. (2015) ‘La Tunisie espère augmenter le nombre de touristes du Golfe de 10% en 2015’. [online] Available at: http://aa.com.tr/fr/economie/la-tunisie-esp%C3%A8re-augmenter-le-nombre-de-touristes-du-golfe-de-10-en-2015/49295.

Al-Hamarneh, A. and Steiner, C. (2004) ‘Islamic tourism: Rethinking the strategies of tourism development in the Arab World after September 11, 2011’, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 24 (1): 173–182.

Ben Nessir, C. (2012) ‘Il n’y a pas de tourisme halal’, La Presse, 17 April. [online] Available at: www.lapresse.tn/component/nationals/?task=article&id=48453 (accessed 26 October 2017).

Bourgou, M. and Kassah, A. (2008) L’île de Djerba. Tourisme, Environnement et Patrimoine. Tunis: Cérès Editions.

Boussetta, M. (2018) ‘Reducing barriers: How the Jews of Djerba are using tourism to assert their place in the modern nation state of Tunisia’, Journal of North African Studies, 23 (1–2): 311–331.

Bouzahzah, M. and El Menyari, Y. (2013) ‘International tourism and economic growth: The case of Morocco and Tunisia’, Journal of North African Studies, 18 (4): 592–607.

Carboni, M., Perelli, C. and Sistu, G. (2014) ‘Is Islamic tourism a viable option for Tunisian tourism? Insights from Djerba’, Tourism Management Perspectives, 11: 1–9.

Carboni, M., Perelli, C. and Sistu, G. (2017) ‘Developing tourism products in line with Islamic beliefs: Some insights from Nabeul–Hammamet’, Journal of North African Studies, 22 (1): 87–108.

Cirer-Costa, J.C. (2017) ‘Turbulence in Mediterranean tourism’, Tourism Management Perspectives, 22: 27–33.

De Kadt, E. (1979) Tourism: Passport to Development? Perspectives on the Social and Cultural Effects of Tourism in Developing Countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Di Peri, R. (2015) ‘An enduring “touristic miracle” in Tunisia? Coping with old challenges after the revolution’, British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 42 (1): 104–118.

Eid, R. and El-Gohary, H. (2015) ‘The role of Islamic religiosity on the relationship between perceived value and tourist satisfaction’, Tourism Management, 46: 477–488.

Elaziz, M.F. and Kurt, A. (2017) ‘Religiosity, consumerism and halal tourism: A study of seaside tourism organizations in Turkey’, Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 65 (1): 115–128.

Errais, E. (2015) ‘To invest or not invest in a distressed hospitality sector: The case of Tunisia’, Journal of Private Equity, 18 (2): 83–100.

Hamza, I.M., Chouhoud, R. and Tantawi P. (2012) ‘Islamic tourism: Exploring perceptions & possibilities in Egypt’, African Journal of Business and Economic Research, 7 (1): 85–98.

Haugbølle, R.H. (2015) ‘New expressions of Islam in Tunisia: An ethnographic approach’, Journal of North African Studies, 20 (3): 319–335.

Hazbun, W. (2007) ‘Images of openness, spaces of control: The politics of tourism development in Tunisia’, Arab Studies Journal, 15/16, (2/1): 10–35.

Hazbun, W. (2008) Beaches, Ruins, Resorts: The Politics of Tourism in the Arab World. Chicago, IL: University of Minnesota Press.

Hazbun, W. (2010) ‘Modernity on the beach: A postcolonial reading from southern shores’, Tourist Studies, 9 (3): 203–222.

Henderson, J.C. (2010) ‘Sharia-compliant Hotels’, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 10 (3): 246–254.

Hibou, B. (2011) ‘Macroéconomie et domination politique en Tunisie: du “miracle économique” benaliste aux enjeux socio-économiques du moment révolutionnaire’, Politique Africaine, 124: 127–154.

Holliday, R., Bell, D., Cheung, O., Jones, M. and Probyn, E. (2015) ‘Brief encounters: Assembling cosmetic surgery tourism’, Social Science & Medicine, 124: 298–304.

Institut Arabe des Chefs d’Entreprises (IACE). (2011) Le tourisme en Tunisie: Constat du secteur, défis et perspectives. Tunis: IACE.

Khlif, W. (2006) ‘L’hôtellerie tunisienne: Radioscopie d’un secteur en crise’, L’Année du Maghreb, 1: 375–394.

Klabi, F. (2014) ‘Forecasting non-residents’ monthly entries to Tunisia and accuracy comparison of time-series methods’, Journal of North African Studies, 19 (5): 770–791.

Krimi, A. (2017) ‘Selma Elloumi: le tourisme “Halal” n’existe pas en Tunisie’, l’Economiste Maghrébin, 7 July. [online] Available at: www.leconomistemaghrebin.com/2017/07/07/selma-elloumi-tourisme-halal-nexiste-tunisie/(accessed 26 October 2017).

La Presse. (2011) ‘Vers l’instauration d’un tourisme religieux …’, 10 November. [online]. Available at: www.lapresse.tn/26022016/40103/vers-linstauration-dun-tourisme-religieux%E2%80%A6.html.

La Presse. (2012) ‘La Tunisie, plateforme des industries halal vers l’Europe et l’Afrique’, 16 May. [online]. Available at: www.lapresse.tn/26022016/49882/la-tunisie-plateforme-des-industri es-halal-vers-leurope-et-lafrique.html.

Larguèche, A. (2008) ‘L’histoire à l’épreuve du patrimoine’, L’Année du Maghreb, 4: 191–200.

Mansfeld, Y. and Winckler, O. (2015) ‘Can this be Spring? Assessing the impact of the “Arab Spring” on the Arab tourism industry’, Tourism, 63 (2): 205–223.

Miossec, J.M. (1999) ‘Les acteurs de l’amenagement tunisien: les leçon d’une performance’. In M. Berriane and H. Popp (eds) Le Tourisme au Maghreb: Diversification du produit et développement local et régional. Rabat: Faculté des Lettres et Sciences Humaines de Rabat, 65–85.

Miossec, J.M. and Bourgou, M. (2010) Les littoraux: Enjeux et dynamiques. Paris: PUF.

Office National du Tourisme Tunisien (ONTT). (2011) Le Tourisme Tunisien en chiffres 2010. Tunis: ONTT.

Office National du Tourisme Tunisien (ONTT). (2012) Le Tourisme Tunisien en chiffres 2011. Tunis: ONTT.

Office National du Tourisme Tunisien (ONTT). (2017) Le Tourisme Tunisien en chiffres 2016. Tunis: ONTT.

Perelli, C. and Sistu, G. (2013) ‘Jasmines for tourists. Heritage policies in Tunisia over the last decades’. In J. Kaminski, A.M. Benson and D. Arnold (eds) Contemporary Issues in Cultural Heritage Tourism. Abingdon: Routledge, 71–87.

Perles-Ribes, J.F., Ramón-Rodríguez, A.B., Moreno-Izquierdo, L. and Torregrosa Martí, M. (2018) ‘Winners and losers in the Arab uprisings: A Mediterranean tourism perspective’, Current Issues in Tourism, 21 (16): 1810–1829.

Poirier, R. (1995) ‘Tourism and development in Tunisia’, Annals of Tourism Research, 22 (1): 157–171.

Pouessel, S. (2012) ‘Les marges renaissantes: Amazigh, Juif, Noir. Ce que la révolution a changé dans ce “petit pays homogène par excellence” qu’est la Tunisie’, L’Année du Maghreb, 8: 143–160.

Prayag, G. and Hosany, S. (2014) ‘When Middle East meets West: Understanding the motives and perceptions of young tourists from United Arab Emirates’, Tourism Management, 40: 35–45.

Rijkers, B., Freund, C. and Nucifora, A. (2017) ‘All in the family: State capture in Tunisia’, Journal of Development Economics, 124: 41–59.

Sarra, A. (2012) Tunisie—Exportations: Le marché halal … est toujours à notre portée. [online] Web Manager Center. Available at: www.webmanagercenter.com/management/imprim.php?id=119954&pg=1.

Scott, N. and Jafari, J. (2010) ‘Islam and tourism’. In N. Scott and J. Jafari (eds) Tourism in the Muslim World. Bingley, West Yorkshire: Emerald, 1–13.

Sethom, H. (1979) ‘Les tentatives de remodelage de l’espace tunisien depuis l’indépendance’, Méditerranée, 35: 119–125.

Steiner, C. (2010) ‘Impacts of September 11: A two-sided neighborhood effect’. In N. Scott and J. Jafari (eds) Tourism in the Muslim World. Bingley, West Yorkshire: Emerald, 181–204.

Stephenson, M.L. and Ali, N. (2010) ‘Tourism and Islamophobia in non-Muslim states’. In N. Scott and J. Jafari (eds) Tourism in the Muslim World. Bingley, West Yorkshire: Emerald, 235–251.

Stephenson M.L., Russell, K. and Edgar, D. (2010) ‘Islamic hospitality in the UAE: Indigenization of products and human capital’, Journal of Islamic Marketing, 1 (1): 9–24.

Tessler, M.A. (1980) ‘Political change and the Islamic revival in Tunisia’, The Maghreb Review, 5 (1): 8–19.

Touzani M., Hirschman, E.C. and Smaoui, F. (2016) ‘Marketing communications, acculturation in situ, and the legacy of colonialism in revolutionary times’, Journal of Macromarketing, 36 (2): 215–228.