Introduction

Muslims have lived in China since the eighth century (Lipman 2011), and have developed a unique ethnic group in China known as the Hui (Huízú 回族) (Dillon 2013). The Hui, along with nine other ethnic groups with Muslim culture, including the Uyghyr, the Kazakh, the Kyrgyz, the Tajik, the Uzbek, the Tatar, the Dongxiang, the Salar, and the Baoan, form about 23 million of China’s population in total (Sai & Fischer 2015). China is home to 10.6 million Hui people, the majority of whom are Chinese-speaking practitioners of Islam, though some may practise other religions (Gustafsson & Sai 2014). The Hui make up a large percentage of population in many provincial units, such as Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (20.53 per cent), Gansu (11.89 per cent), Xinjiang (9.29 per cent), Henan (9.05 per cent), Qinghai (7.88 per cent), Yunnan (6.60 per cent), Hebei (5.39 per cent), and Shandong (5.06 per cent) (National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBSC) 2010).

Halal food in China can be traced back to more than 1,300 years ago in China’s history. It has developed into a unique food culture in China, and was signified by two Chinese characters qing zhen (清真). Qing zhen food is widely welcomed by not only Muslims but also non-Muslims in China, for its ethnic cuisine and cooking methods. Almost every Chinese university has its own halal/qing zhen restaurant on its campus. There are 34 provincial units in China, with a population of 1.3 billion (NBSC 2010), and thus regulating and certificating halal food is rather a challenging job, not to mention the complex nature of halal food treatment at different stages of the food supply chain (Liu 2013). Various stakeholders that are involved in this complex process include different ethnic groups with Muslim culture, Islamic associations, central and local governments, Standing Committees of People’s Congress, industrial and commercial bureaus, sanitary bureaus, and quarantine bureaus. More recently, halal food availability has also become significant for the country’s tourism industry given the growth in arrivals from Islamic countries (Statistical, Economic and Social Research and Training Centre for Islamic Countries (SESRIC) 2017). After France, the USA and Spain, China is the fourth most popular destination for arrivals from the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) countries (SESRIC 2017). In addition, halal certification is also becoming increasingly important for tourism and trade initiatives, such as the UNWTO Silk Road Programme (SESRIC 2017) and China’s Silk Road Economic Belt and Maritime Silk Road initiatives (Liu 2015; Yang, Dube & Huang 2016). Understanding the similarities and variations between different provincial units becomes the first task in comprehending the history, reality, and the future of halal food certification in China.

In China, the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (NHAR) is the only autonomous region for the Hui people, a Chinese ethnic group of adherents of Islam. The population of the Hui accounts for a big portion of the population of NHAR. NHAR was the first provincial unit in China to carry out regulations on halal/qing zhen certification and standardisation, and thus is a representative context for understanding regional halal food certification in China.

This chapter first briefly reviews the history of Muslim culture and halal food in China, and further summarises regulations on the halal food certification and standardisation in the 23 provinces, 4 municipalities directly under the central government, 5 autonomous regions, and 2 special administrative regions (SARs) of China. These regulations from different provincial units are compared in terms of a series of criteria, including legislative bodies, with or without standardised certificates or logos, etc. Specifically, NHAR, an autonomous region for Hui people, is studied on its halal food certification as a special case in the chapter. Via the summary of regional halal food regulation frameworks, this chapter depicts the status quo and studies the trend of halal food certification in China. The case study on NHAR further assists in illustrating the history and dynamics of halal food certification in China.

History of halal food in China

Muslim culture and the Hui in China

Since AD 651, the year that Islam was introduced to China in the Tang Dynasty (AD 618–907), Islam has spread into many regions of China (Chang 1987). Nowadays, most Muslim minorities reside in densely populated areas in north-west China, while the Hui reside nationwide (Sai & Fischer 2015; Hall & Page 2017). According to the sixth national census in 2010, China is home to about 23 million Muslims, out of which 10,586,087 are the Hui people (NBSC 2010). Table 19.1 illustrates the Muslim population in each ethnic group. The Hui population increased by 3.4 million in less than 30 years from 1982 to 2010 (Dillon 2013). Hui is the third-largest of China’s minorities after the Zhuang (壮族) and Manchu (满族). The Hui have spread throughout China’s provincial units, and the highest concentration is in NHAR, where 34.5 per cent of the population is Hui (Gustafsson & Sai 2014). The Hui are similar to the Han majority in physical appearance as well as in the use of language (Mandarin in general), but follow Islamic dietary laws consuming halal food only. The Hui in addition follow a religious dress code: “Hui women frequently wear headscarves and men wear white caps” (Gustafsson & Sai 2014: 973). The Hui used to marry only within their own ethnic group, but have become more open to intermarriage with other ethnic groups in recent years.

Table 19.1 Muslim population in China

| Ethnic group | Total | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hui | 10,586,087 | 5,373,741 | 5,212,346 |

| Uyghyr | 10,069,346 | 5,097,594 | 4,971,752 |

| Kazakh | 1,462,588 | 747,368 | 715,220 |

| Dongxiang | 621,500 | 317,490 | 304,010 |

| Kyrgyz | 186,708 | 94,645 | 92,063 |

| Salar | 130,607 | 66,281 | 64,326 |

| Tajik | 51,069 | 26,112 | 24,957 |

| Uzbek | 10,569 | 5,673 | 4,896 |

| Baoan | 20,074 | 10,016 | 10,058 |

| Tatar | 3,556 | 1,899 | 1,657 |

| Muslim | 23,142,104 | 11,740,819 | 11,401,285 |

| Han | 1,220,844,520 | 625,032,848 | 595,811,672 |

| All | 1,332,810,869 | 682,329,104 | 650,481,765 |

Source: NBSC, 2010.

Halal/qing zhen food in China

Halal food has a long history in China, and it originated with Islam culture being introduced to China in the Tang Dynasty. He (2014) claims that the ideology of China’s halal diet was founded by Yūsuf Khāṣṣ Ḥājib Balasağuni (حاجب خاصّ يوسف) and Mehmud Qeshqeri in Kashgar, Xinjiang. According to He (2014) the principles of ancient Chinese halal diet cover aspects of habitus, food material, cooking methods, hygiene, regimen, and environment.

Halal food is characterised by two Chinese characters qing zhen (清真), meaning the “Pure and True”. These two characters are strongly associated with Hui identity (Yang & Li 2007). They have been used to distinguish restaurants, food shops, bakeries, ice-cream stands, candy wrappers, mosques, Islamic literary works, and can even be found on packages of incense produced in the Dachang Hui autonomous country east of Beijing (Gladney 1996). Although there are alternate terms including haliale (哈俩勒), haliali (哈俩里), and hala (哈拉), all of which are phonetic equivalents of the original Arabic term, the Hui people prefer qing zhen as an indication that the provider of the food or services is Muslim (Gillette 2000; Sai 2013, 2014).

Many Chinese Islamic scholars see qing zhen and halal as inseparable or transferrable. The relationship between qing zhen and halal has evolved historically through the engagement and interaction between Islamic, Chinese, and transnational cultural values, and accordingly qing zhen illustrates the outcome of the localisation and adaptation of Islamic food culture in Chinese culture, and food culture in particular. Qing zhen is “an ethnic term of Chinese-speaking people and its practical usage is linked to ethnic, religious and cultural understandings of Muslims” (Sai & Fischer 2015: 163). Qing zhen food is often considered as inseparable from Chinese cuisine, and is widely consumed by non-Muslims as an ethnic, local, and “clean” cuisine (Sai & Fischer 2015).

Halal/qing zhen food certification in China

Development of halal/qing zhen food certification in China

Halal certification and standardisation were not introduced to China until the late twentieth century. Prior to this, the two Chinese characters qing zhen (清真) were widely used to denote halal food, associated with “a water pot and a hat” (Sai & Fischer 2015: 161). “The water-pot signifies ceremonial cleanliness, and is a guarantee that no pork is used, while the hat indicates respect to customers” (Broomhall 1987: 224).

Different Islamic authorities in China and the People’s Republic of China government’s endeavours with respect to halal/qing zhen certification and standardisation are relatively recent. The politics and policies of qing zhen food regulation are not only affecting Muslim minorities such as the Hui, but are also influencing non-Muslim communities at different levels of their social lives. In principle, government regulation of qing zhen food in China was conducted under the aegis of ethnic policy (Sai 2014), as well as perceived concerns of both Muslim and non-Muslim communities over food safety.

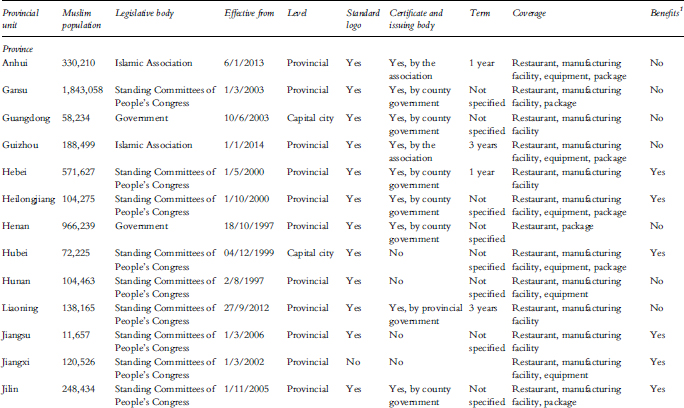

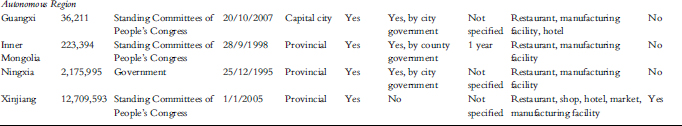

Many provincial units have established their own regulations on qing zhen food certification and standardisation, and the legislative bodies include provincial or local governments, the Standing Committees of People’s Congress, and regional Islamic associations. Different regulations further apply at four levels: provincial units, capital cities, prefecture-level cities, and county units. There is currently no national-level regulation on qing zhen food certification and standardisation in China, except general regulations to support all ethnic groups in the Regulations on Urban Ethnic Work carried out on 15 September 1993, as well as in the Regulation on Religious Affairs carried out on 30 November 2004 and revised on 14 June 2017 (State Council of the People’s Republic of China (SCPRC) 2017). In this regulation, it is stated that qing zhen food manufacture and services should be protected and supported (The State Ethnic Affairs Commission of PRC (SEAC) 1993). In addition, there are no specially established regulation-enforcing departments at any level, and cases such as violations to these regulations are often dealt with by general functional departments, such as industrial and commercial bureaus, sanitary bureaus, and quarantine bureaus. The summary of qing zhen food certification in China is illustrated in Table 19.2, based on a review of all available documents on halal/qing zhen food certification from governments, Standing Committees of People’s Congress, Islamic associations across all provincial units of China. Specifically, 30 halal food certification related documents were found from government websites, webpages of Islamic associations, legal document databases. These documents are from national to city levels, specifying regulations and guidelines of halal food certification in China.

Table 19.2 Qing zhen food certification in China

Note: 1 Benefits refers to the receipt of financial or policy support from government or associations after certification has been granted.

Summary of qing zhen food certification in China

In summary, 24 out of 34 (70.6 per cent) provincial units have provincial-level regulations in place for qing zhen food certification and standardisation, and 4 (11.8 per cent) other provincial units have capital-city-level regulations (Guangdong, Hubei, Sichuan, and Guangxi). The provinces or municipalities directly under the central government or autonomous regions without regulations on qing zhen food certification and standardisation are: Fujian, Hainan, Taiwan, and Tibet. Neither Hong Kong nor Macau has any specific regulations with respect to supervising qing zhen food related business. The majority of these regulations were developed between 1995 and 2005, after the enactment of the Regulations on Urban Ethnic Work in 1993. Sixteen regulations were made by the Standing Committees of People’s Congress at the provincial level, except that of Sichuan (made by the Standing Committees of Chengdu People’s Congress). Nine regulations were written by relevant offices in the governments, and the Islamic associations released the other three. The majority of regulations specify the application of standardised logos (24 provincial units) and certificates (17 provincial units). However, contents vary to a great extent from province to province and many regulations lack details. For instance, very few regulations specify how long the period of certification is valid for. Table 19.3 illustrates the descriptive statistics summarising basic characteristics of these regulations.

Table 19.3 Statistical overview of provincial unit halal regulations

| Number of provincial units | 34 |

|---|---|

| Provincial units with regulations | 28 (82.4%) |

| Provincial units without regulations | 6 (17.6%) |

| Regulations at provincial level | 24 (70.6%) |

| Regulations at capital level | 4 (11.8%) |

| By the Standing Committees of People’s Congress | 16 (47.1%) |

| By the government | 9 (26.5%) |

| By the Islamic association | 3 (8.8%) |

| With standardised logo | 24 (70.6%) |

| Without standardised logo | 4 (11.8%) |

| With certificate | 17 (50.0%) |

| Without certificate | 11 (32.4%) |

| With policy support | 9 (26.5%) |

| Without policy support | 19 (55.9%) |

| Regulations specific to qing zhen food | 25 (73.5%) |

| Regulations on general ethnic affairs | 3 (8.8%) |

The regulations on halal or qing zhen food can be defined into four streams (La 2008):

(1) The first stream of regulations defines halal or qing zhen food as food that is permissible or lawful in traditional Islamic law, i.e. religiously defined. One example of this type of definition of qing zhen food is in Gansu’s regulation on qing zhen food certification:

Qing zhen food in this regulation refers to all food produced, processed, transported, and sold that is lawful in Islamic law.

(2) The second stream of regulations defines qing zhen food from the ethnic perspective. Provinces such as NHAR, Xinjiang, Liaoning, and Henan follow this definition. For instance, the regulation from Shandong province defines qing zhen food as follows:

Qing zhen food refers to the collection of food that is produced and processed in terms of the religious and cultural customs of the ethnic groups of the Hui, the Uyghyr, the Kazakh, the Kyrgyz, the Tajik, the Uzbek, the Tatar, the Dongxiang, the Salar and the Baoan.

(3) The third stream of regulations defines qing zhen food combining both religious and ethnic perspective such as Shanghai’s regulations.

(4) The last stream of regulations is limited in clearly explaining what qing zhen food is, or does not have a clear definition at all.

Several provinces have no regulations specifically on halal food or the Muslim community, but rather use those regulating general ethnic matters for a wider audience. For instance, the titles of the regulations of Hubei, Jiangxi, and Chongqing are Regulations on Ethnic Affairs. These regulations do include items on qing zhen food but are limited in details.

Regulations on qing zhen food in different regions also vary greatly in terms such as requirements on ethnics, personnel, food processing, food supply, treatments of equipment, as well as qing zhen food practitioners’ rights. For instance, Nanning Qing Zhen Food Regulation permits only Muslim owners to apply for qing zhen certificates, and requires qing zhen food appliances only when preparing qing zhen food. This regulation also entitles qing zhen food practitioners the rights of not serving customers with food not permissive or lawful in the definition of qing zhen. Regulation in Henan Province specifies that the ratio of Muslim to other staff in a qing zhen food manufacturing business should not be less than 15 per cent, that in a qing zhen food distribution company it should not be less than 20 per cent, and that in qing zhen restaurants it should not be less than 25 per cent. Other provinces such as Beijing, Inner Mongolia, Shaanxi, Shanxi, Tianjin, and Yunnan, also have similar requirements. Except for NHAR, the highest requirements for such ratios are in the regulation of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region where at least 40 per cent of the staff should be Muslims in qing zhen food processing companies.

The majority of regulations in China empower regional ethnic affairs departments or offices in the government issuing qing zhen logos and certificates. However, in many provinces and regions, it is the general commercial bureaus, rather than the ethnic affairs departments, that supervise and manage the halal market, as well as the law enforcement. A few other regulations entrust regional industrial and commercial offices with full authority for qing zhen food certification. This “issued-by-one-supervised-by-another” practice has both advantages and disadvantages. On the positive side, this practice avoids giving too much power to regional ethnic affairs departments that are often without specific expertise in market supervision. However, it is also the main cause for confusion in the market as general regional industrial and commercial offices work on all aspects of the market supervision, and often overlook the specific required practices of the qing zhen food sector (Zhang 2006).

Use of the Qing zhen logo in China

As can be seen in Table 19.2, standardised logos are available in 24 provincial units. However, none of these provincial-, city-, or county-level units releases its certified logo design to the public. Unfortunately, there are a huge number of certified and uncertified qing zhen logos across China, for a number of reasons. First, there is no national-level legislation or supervision on this matter and each region has its own regulation and design of qing zhen logo. Second, regulations from each provincial unit often lead to a lack of transparency in certifying qing zhen logos, as a result of which it is difficult for the public to distinguish certified logos from uncertified ones. Third, the use of qing zhen logos lacks supervision (La 2008), and usage of uncertified logos are generally not penalised. As discussed above, the “issued-by-one-supervised-by-another” therefore leads to chaos in the market with respect to logo use. Lastly, non-Muslim consumers in China are open to qing zhen food, motivating individual food manufacturing companies and restaurant owners to develop and use qing zhen logos. For example, Lanzhou Noodle Soup, also known as Lanzhou Lamian or Lanzhou Ramen (兰州拉面) is a famous qing zhen food made of stewed beef and noodles, created by the Hui people in Gansu area during the Tang Dynasty of China. There are numerous restaurants branding Lanzhou noodle soup almost everywhere in China. However, each of them has a different brand name and qing zhen logo. Figure 19.1 illustrates some examples of the variety of qing zhen logo usage in Lanzhou Noodle Soup restaurants. Different famous food brands in China also introduced a qing zhen version of their products and labelled these products with various qing zhen logos, such as milk brand Yili (伊利), cooking oil brand Luhua (鲁花), and the biscuit brand Oreo.

Figure 19.1 Different usage of qing zhen logos by Lanzhou Noodle Soup restaurants

The chaotic market circumstances of using a qing zhen logo have created opportunities for qing zhen food business owners and plays an important role in forming new marketing strategies. Niujie street (牛街) is a neighbourhood in Xicheng District in south-west Beijing, populated by the Hui people in majority, and is the home of a number of traditional Beijing-style qing zhen food shops. Due to the confusion surrounding qing zhen logo usage, the Niujie Qing Zhen Food Chamber of Commerce created and announced its collaborative qing zhen brand logo in December 2015, although it has not yet been recognised by the Beijing Hui community to date. Niujie qing zhen food practitioners create their own qing zhen logo as a brand, an identity, and also as a symbol to promote their historical qing zhen food heritage (as illustrated in Figure 19.2). However, the development of the logo was not a challenge by Niujie qing zhen food practitioners of the authority of the Beijing government in regulating qing zhen food, even though Beijing has its own qing zhen brand logo initiative. Instead, the district industrial and commercial office actually led the formation of the Niujie Qing Zhen Food Chamber of Commerce and provided great support for the design of this logo (China News 2015). From this perspective the logo becomes attached as much to local food promotion as it does to specific concerns over the halal status of foods.

Figure 19.2 Niujie qing zhen food practitioners’ own qing zhen brands

Qing zhen food without regulations

There are several provincial units in China without regulations on qing zhen food certification and standardisation. For instance, in Fujian Province in southern China, there are few Muslims, hardly any qing zhen food shops, few qing zhen/halal restaurants, and no official halal standards. Sai (2014) studied an area in Fujian Province and found that, instead, the two principles essential to halal matters were honesty and responsibility, factors associated with halal restaurants in other countries in which Muslims are in a minority (Wan Hassan & Hall 2003; Wan Hassan 2009). Sai’s case study found that halal food (especially halal meat) shoppers secure the authenticity of halal food via two approaches: (1) to participate in animal slaughter to assure that the food process is permissible or lawful in traditional Islamic law; or (2) to obtain qing zhen food from a trustworthy personal contact. Generally, qing zhen restaurants display a self-made qing zhen logo or mark to indicate their identities. Sai found an interesting case when a Muslim owner sold his restaurant to a non-Muslim owner without removing his qing zhen logo. The imam visited the restaurant and convinced the new owner to remove the logo, after explaining the significance of qing zhen to Muslims. Interestingly, the public criticised the previous Muslim owner for being irresponsible and not removing the qing zhen logo before selling the restaurant.

Halal/qing zhen food certification in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (NHAR)

Autonomous regions in China are first-level administrative divisions of China that are autonomous where ethnic minorities have more legislative rights. Out of the five autonomous regions, NHAR is the only autonomous region for the Hui people, a Chinese ethnic group that is composed predominantly of adherents of Islam. NHAR’s ethnic legislation has been operating since 1954 (Li & Cai 1999). The population of the Hui people in NHAR is 2.17 million, accounting for 34.5 per cent of the population of NHAR. The Regulation on Halal/qing zhen Food of Yinchuan (the capital city of NHAR) was declared on 25 April 1992, and is the earliest and most detailed regulation on halal food certification and standardisation in China. It specifies processes in the manufacture, production, storage, sales, transportation, and other aspects of halal food business (Li & Cai 1999; Wang 2016).

On 1 January 2003, NHAR Guidelines for Qing Zhen Food Certification were introduced in NHAR. The guidelines were an updated version of the regulation developed in 1992. The Qing zhen logo was also updated by a new design. Figure 19.3 illustrates the introduced standard qing zhen food logo for NHAR. These guidelines have the strictest requirement on personnel in China, and require that all directors, procurement managers, storage managers, chefs, and at least 40 per cent of regular staff must be Muslims (Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region Government (NHARG) 2002). The guidelines empower both ethnic affairs departments and industrial and commercial departments in supervising and managing qing zhen food certification in a collaborative form. As of 2016, 20 institutions in 16 foreign countries and regions, including Malaysia, Australia, and New Zealand, had signed a mutual recognition agreement on halal food standards with Ningxia (Yang et al. 2016).

In 2013, five provinces in western China including NHAR, Gansu, Qinghai, Shaanxi, and Yunnan jointly founded the Regional Qing Zhen Food Certification Federation, and agreed to establish confederal guidelines entitled Guidelines for Qing Zhen Food Certification. This document equates qing zhen with halal, citing the Codex Alimentarius Commission’s General Guidelines for using the term of ‘halal’ (Sai 2013). The new halal logos and certificates, issued by Islamic associations, incorporate not only qing zhen in Chinese characters, but also halal in English or Arabic in some instances, which may also reflect the growth in international tourism by Muslims (SESRIC 2017) as well as the desire to increase exports. “More and more halal productions, such as halal beef and mutton, dehydrated vegetables, dairy, sauces, and health care products, etc., have been successfully entered into the Middle East, Europe and the United States markets” (Yang et al. 2016: 2). The guidelines cover a population of 5.10 million Hui people (NBSC 2010). These guidelines were mainly developed based on NHAR Guidelines for Qing Zhen Food Certification, and specify in more detail the food materials not permitted in qing zhen food. Another three provincial units of China, Henan, Sichuan, and Tianjin, joined these guidelines in 2015, extending the coverage of these guidelines to a population of 6.34 million Hui people (NBSC 2010) as well as the export market.

A major initiative of these confederal guidelines was to push a “global assemblage” between China’s qing zhen industries and halal industries in other countries, e.g. Malaysia (China Daily 2013). A standardisation and internationalisation of qing zhen food certification potentially enables a market transformation of China’s qing zhen industry so as to connect to the global halal market, which may play an important role in China’s initiative of the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road given the increased connectivity that this provides to major Islamic markets in the Middle East, South and South East Asia and North Africa (Liu 2015; Hall & Page 2017; Li 2018). This effort also reinforces regional government’s commitment to ensuring the reliability and authority of qing zhen certification in China (Sai 2013). As of 2016, China’s share of the international halal food trade was estimated at around 0.5 per cent (Yang et al. 2016) therefore highlighting the potential for Chinese halal food production in the future (Brose 2017, 2018). However, major barriers for development of Chinese halal exports are the certification process as well as halal logistics. According to Yang et al. (2016) their interviews with halal food producers and government agencies suggested that

obtaining a halal certification in Ningxia is not very difficult for firms, but the effect of it on the export of products is unsatisfied. The survey result shows that companies have to apply for halal certification abroad because of lacking of standard mutual recognition, which virtually not only increased the operating costs, but also, more important, made the authentication process long and complex. Otherwise, understanding the foreign requirements, filling in the relevant formalities, and receiving the foreign certification test interview are also the greater challenges for the enterprises to face.

(Yang 2016: 3)

Conclusions

China has a growing regulatory system for halal food that covers both production and supply to consumers, whether local or to the increasing numbers of Islamic tourists. However, its devolved nature and management structures creates substantial issues with respect to the authorised use of halal logos as well as their recognition in the marketplace. These issues are becoming of even greater concern given the interest of the Chinese government as well as some provincial governments, such as that of NHAR, in expanding halal exports, given the Chinese government’s investment in new Silk Road initiatives as part of its international trade, tourism, and diplomacy strategy (Li 2018). In this China experiences some of the same problems with respect to halal certification, logistics, access, and end-consumer confidence in halal food markets as other non-Islamic countries (Abdul-Talib & Abd-Razak 2013).

As of late 2018, there is undoubtedly substantial contestation between different perspectives on halal certification and food in China. On one hand there is enthusiasm for the promotion of certification and production efforts given the potential of the international halal food market and the country’ substantial investments in new transport infrastructure as part of Belt and Road initiatives. However, at the same time authorities in Xinjiang have launched a campaign against religious extremism, mainly focusing on preventing the generalisation of qing zhen concept beyond food domain, which might be interpreted differently by various stakeholders. This has been interpreted as a campaign against the spread of halal products (Kuo 2018). According to the state-owned Global Times in an article about the new campaign in Urumqi, “A group of people in the society are calling for halal/qing zhen certification for almost all product rather than food only, such as qing zhen water, qing zhen paper, qing zhen toothpaste, qing zhen cosmetics, etc. This is what we see as a pan-halal tendency” (Ye 2016). The initiative has also spread to Gansu province, home to a large population of Hui Muslims, where officials shut down more than 700 shops selling “pan-halal products” in March 2018 (Kuo 2018). The Chinese case demonstrates that while there is enthusiasm to export halal products and therefore develop halal foods and logistics there are clear tensions between domestic and international policy positions and broader concerns over Islam in society and the potential challenges this has for the politics of food, heritage, and identity in China.

References

Abdul-Talib, A.N. and Abd-Razak, I.S. (2013) ‘Cultivating export market oriented behaviour in Halal marketing: Addressing the issues and challenges in going global’, Journal of Islamic Marketing, 4 (2): 187–197.

Broomhall, M. (1987) Islam in China. London: Darf Publishers.

Brose, M. (2017) ‘Permitted and pure: Packaged halal snack food from Southwest China’, International Journal of Food Design, 2 (2): 167–182.

Brose, M. (2018) ‘China and transregional Halal circuits’, Review of Religion and Chinese Society, 5 (2): 208–227.

Chang, H.Y. (1987) ‘The Hui (Muslim) minority in China: An historical overview’, Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs Journal, 8 (1): 62–78.

China Daily. (2013) ‘Halal food helps Ningxia explore int’l market’, China Daily, USA, 16 September. [online] Available at: http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/food/2013-09/16/content_16972391.htm (accessed 15 September 2017).

China News. (2015) ‘牛街有了集体商标 “牛街清真食品”标识公布 [Niujie is introducing its collaborative “Niujie Qing Zhen Food” logo]’, China News, Beijing, 8 December. [online] Available at: www.chinanews.com/cj/2015/12-08/7661645.shtml (accessed 15 August 2017).

Dillon, M. (2013) China’s Muslim Hui Community: Migration, Settlement and Sects. London: Routledge.

Gillette, M.B. (2000) Between Mecca and Beijing: Modernization and Consumption among Urban Chinese Muslims. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Gladney, D.C. (1996) Muslim Chinese: Ethnic Nationalism in the People’s Republic. Harvard East Asian Monographs, 149. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University.

Gustafsson, B. and Sai, D. (2014) ‘Why is there no income gap between the Hui Muslim minority and the Han majority in rural Ningxia, China?’, China Quarterly, 220: 968–987.

Hall, C.M. and Page, S.J. (2017) ‘Tourism in East and North-East Asia: Introduction’, in C.M. Hall and S.J. Page (eds) The Routledge Handbook of Tourism in Asia. Abingdon: Routledge, 301–308.

He, S. 何顺斌 (2014)中国清真烹饪 [Halal Food in China]. Beijing: China Light Industry Press.

Kuo, L. (2018) ‘Chinese authorities launch “anti-halal” crackdown in Xinjiang. Party officials also urged government officers to speak Mandarin at work and in public’, The Guardian, 10 October. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/oct/10/chinese-authorities-launch-anti-halal-crackdown-in-xinjiang

La, Y. 喇延真 (2008) ‘全国清真食品管理法规制定应注意的几个问题 [Some problems to be paid attention to in making the regulations of nation-wide Muslim food management]’, Journal of the Second Northwest University for Nationalities, 82 (4): 125–127.

Li, F. (2018) ‘The role of Islam in the development of the “Belt and Road” initiative’, Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, 12 (1): 35–45.

Li, W. 李温 and Cai, W. 蔡伟 (1999) ‘宁夏民族立法建设五十年 [50 years of NHAR’s ethnic legislation]’, Social Sciences in Ningxia, 5: 26–30.

Lipman, J.N. (2011) Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

Liu, J. 刘建功 (2013) ‘基于物联网的清真食品安全和清真认证可追溯系统研究 [Research on the tracibility system of halal identification and the safety of halal food based on the internet of things]’, Journal of Beifang University of Nationalities, 6 (114): 56–59.

Liu, J. (2015) ‘The research of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region’s Halal food Muslim supply chain in Silk Road Economic Belt’. In International Conference on Social Science and Technology Education (ICSSTE 2015). [online] Sanya, China, 974–978. Available at: www.atlantis-press.com/php/download_paper.php?id=18910 (accessed 29 September 2017).

National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBSC). (2010) ‘Tabulation of the 2010 population census of the People’s Republic of China’, NBSC, Beijing. [online] Available at: www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/pcsj/rkpc/6rp/indexch.htm (accessed 2 August 2017).

Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region Government (NHARG). (2002) ‘Guidelines for Qing Zhen Food Certification’, NHARG, Yinchuan. [online] Available at: http://ningxia.mofcom.gov.cn/article/qzcy/201303/20130300072454.shtml (accessed 2 September 2017).

Sai, Y. (2013) ‘Shoku no Halal wo Meguru Tayou na Koe to Jissen [Multiple voices and practices in halal food and eating]’, Waseda Asia Review, 14: 82–85.

Sai, Y. (2014) ‘Policy, practice, and perceptions of Qingzhen [Halal] in China’, Online Journal of Research in Islamic Studies, 1 (2): 1–12.

Sai, Y. and Fischer, J. (2015) ‘Muslim food consumption in China: Between Qingzhen and Halal1ʹ. In F. Bergeaud-Blackler, J. Fischer and J. Lever (eds) Halal Matters: Islam, Politics and Markets in Global Perspective. London: Routledge, 160–174.

State Council of the People’s Republic of China (SCPRC). (2017) ‘宗教事务条例 [Regulation on Religious Affairs]’, SCPRC, Beijing. [online] Available at: www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2017-09/07/content_5223282.htm (accessed 29 September 2017).

Statistical, Economic and Social Research and Training Centre for Islamic Countries (SESRIC) (2017) International Tourism in the OIC Countries: Prospects and Challenges 2017. Ankara: Organization of Islamic Cooperation, The Statistical, Economic and Social Research and Training Centre for Islamic Countries (SESRIC).

The State Ethnic Affairs Commission of PRC (SEAC). (1993) ‘城市民族工作条例 [Regulations on Urban Ethnic Work]’, SEAC, Beijing. [online] Available at: www.seac.gov.cn/gjmw/zcfg/2004-07-23/1168742761849065.htm (accessed 2 August 2017).

Wan Hassan, M. (2009) Halal Restaurants in New Zealand—Implications for the Hospitality and Tourism Industry. PhD Thesis, University of Otago.

Wan Hassan, M. and Hall, C.M. (2003) ‘The demand for halal food among Muslim travelers in New Zealand’, in C.M. Hall, E. Sharples, R. Mitchell, B. Cambourne and N. Macionis (eds) Food Tourism Around the World: Development, Management and Markets, Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 81–101.

Wang, J. 汪景涛 (2016) ‘关于我国西北地区清真标识泛化问题的几点思考 [Study on the generalization of Muslim logo in northwest China]’, Journal of Hunan Police Academy, 28 (6): 29–35.

Yang, H.J., Dube, F. and Huang, L.J. (2016). ‘Research on the factors influencing halal food industry internationalization: A case study of Ningxia (China)’. 3rd International Conference on Economics and Management (ICEM 2016), DEStech Transactions on Economics, Business and Management, DOI: 10.12783/dtem/icem2016/4069

Yang, W. 杨文笔 & Li, H. 李华 (2007) ‘回族“清真文化”论 [Hui tribe “Islamic Culture” shallow discuss]’, Nationalities Research in Qinghai, 18 (1): 100–104.

Ye, X.W. 叶小文(2016). 警惕宗教“泛化”后面的“极端化”[Watch out for the “extremism” behind pan-religious tendency] The Global Times, 7 May. Available: http://opinion.huanqiu.com/1152/2016-05/8873522.html

Zhang, Z. 张忠孝. (2006). ‘“清真食品” 定义和范围界定问题的探析 [Study on the definition of qing zhen food]’, Journal of Hui Muslim Minority Studies, 1: 165–168.