Chapter Six

Meet Me at the Mall of

America: Minnesota's

Juvenile Justice System

Learning Objectives

- Articulate the age-crime curve and criminological theories of juvenile crime

- Describe the history of juvenile justice in Minnesota

- Discover landmark U.S. Supreme Court decisions pertaining to juvenile justice

- Explore arrest and incarceration data for Minnesota youth

- Explain the juvenile justice process in Minnesota

- Examine core legal protections for juveniles

- Identify what constitutes child abuse and neglect

- Describe issues pertaining to bullying and school violence

- Analyze the evolution of youth intervention programming and project evaluation

Since opening its doors in 1992, the Mall of America (MOA) in Bloomington has become a leader in retail, entertainment and attractions. With a gross area

of nearly 5 million square feet and unique features such as an aquarium and theme park, MOA is often described as a “city within a city” (Mall of America, 2015a). Thanks to approximately 40 million annual visitors, MOA is also one of the top tourist destinations in the United States. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that children and young people frequent MOA in large numbers.

MOA welcomes “all youth,” however on Friday and Saturday evenings, people under the age of 16 must be accompanied by an adult 21 years or older from 4 p.m. until close (Mall of America, 2015b). Why does MOA operate a parental escort policy? Because MOA is concerned about juvenile delinquency.

The Age-Crime Curve

Mall of America's concern about juvenile delinquency is understandable. Research shows crime is most prevalent during mid-to-late adolescence and is in most cases “limited” to adolescence (Moffitt, 1993). In other words, the incidence of crime increases with age until individuals reach about 16 to 20. It then decreases with age in adulthood. Evidence for this “age-crime curve” has been found across samples that vary in terms of demographic and socioeconomic variables (see Farrington, Piquero, & Jennings, 2013). Adolescent crime is almost a prerequisite for adult crime, yet, paradoxically, “most antisocial children do not become antisocial adults” (Robins, 1978, p. 611). This has led some to conclude age has a direct effect on crime and “aging out” is somewhat inevitable, which, if true, renders the entire juvenile justice system irrelevant (Hirschi & Gottfredson, 1983).

A number of criminological theories provide explanations for the age-crime relationship, as follows:

-

Criminal propensity

—youth engage in crime because they have not yet developed internal controls or an ability to see beyond themselves (e.g., impulse control, self-regulation and moral disengagement; Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990);

-

Rational choice

—youth engage in crime based on a rational calculation of factors such as potential benefits and costs (Cornish & Clarke, 1986; Katz, 1988);

-

Social learning

—exposure to antisocial peers and antisocial peer pressure account for youth crime (Sutherland, 1947; Akers, 2009);

-

Social bond

—youth engage in crime commensurate to their stake in conformity and the extent to which formal or informal social controls, such as parents or teachers, are present (Hirschi, 1969);

-

Strain

—social structures within society pressure youth to commit crime (Merton, 1938). Failure to achieve positively valued goals (e.g., as a result of discrimination), loss of positive stimuli (e.g., death of a loved one), and negative stimuli (e.g., physical or emotional abuse) all constitute sources of “strain” (Agnew 1992); and

-

Procedural justice

—youth engage in crime because previous experiences in the criminal justice system lend them to question the legitimacy of “the law” (Fagan & Tyler, 2005).

There is strong empirical support for social learning theory, owing to the fact most crime is committed in groups and adolescents are particularly susceptible to group processes (Sweeten, Piquero, & Steinberg, 2013). In reality, however, the age-crime relationship cannot be reduced to a single theory or overarching construct. As such, efforts by the juvenile justice system to intervene in the lives of youth involved in crime cannot be discounted (Scott & Steinberg, 2010).

The most basic assumption underlining juvenile justice today is juveniles on the whole do not possess the same

mens rea

or criminal intent as adults because they are not as intellectually, morally, or socially developed as adults (Scott & Steinberg, 2010). The adolescent brain, especially the prefrontal cortex, which controls the brain's most advanced decision-making functions, for example, is still developing, thus risks taken and mistakes made by young offenders may be largely outside of their control (Bonnie & Scott, 2013).

Another basic assumption underlining juvenile justice is

societal reaction

or

criminalization

can potentially transform minor juvenile crime problems into major juvenile crime problems (Becker, 1963; Lemert, 1971). First, juveniles labeled

criminal

or

delinquent

and sanctioned accordingly may interpret their “stigma” as master status, which, in turn, transforms their social identity, and consequently, their behavior (see

Chapter Five

). Second, branded youth also encounter social obstacles that disqualify them from “full social acceptance,” such as obtaining meaningful work, earning a high school diploma or post-secondary degree, or building a strong, participatory civic life (Goffman, 1963, p. 9).

A Brief History of Juvenile Justice in Minnesota

In the long history of criminal justice, juvenile justice is a relatively new development (Friedman, 1993). Early in U.S. history, children who broke the law were treated the same as adult criminals. In the early 1800s, alternatives to treating adults and juveniles the same (and housing them together) emerged

with the creation of houses of refuge and reformatories. The first juvenile court in the United States was established in Cook County, Illinois, in 1899. This court was the first to have

original jurisdiction

to hear cases that apply to juvenile crime. This means that juveniles under the age of 16 would come before this court first. The court was also granted authority over neglected and dependent children.

Six years later, in 1905, Minnesota established its own juvenile courts for youth under 17 (Feld, 2007). The original law to “regulate the treatment and control of dependent, neglected, and delinquent children” defined a “delinquent child” as anyone under 17 who used “vile, obscene, vulgar, profane or indecent language,” was “incorrigible,” associated with “thieves, vicious or immoral persons,” and knowingly frequented “a house of ill fame” or saloon or pool hall, or wandered “about the streets in the night time” or “about any railroad yards or tracks” (Tiffany, 1910).

Juvenile courts flourished for the first half of the 20th century and the focus on offenders over offenses and rehabilitation over punishment had substantial procedural impact. At this time, the legal concept of

parens patriae

meant that the benevolent state could and should act

in loco parentis

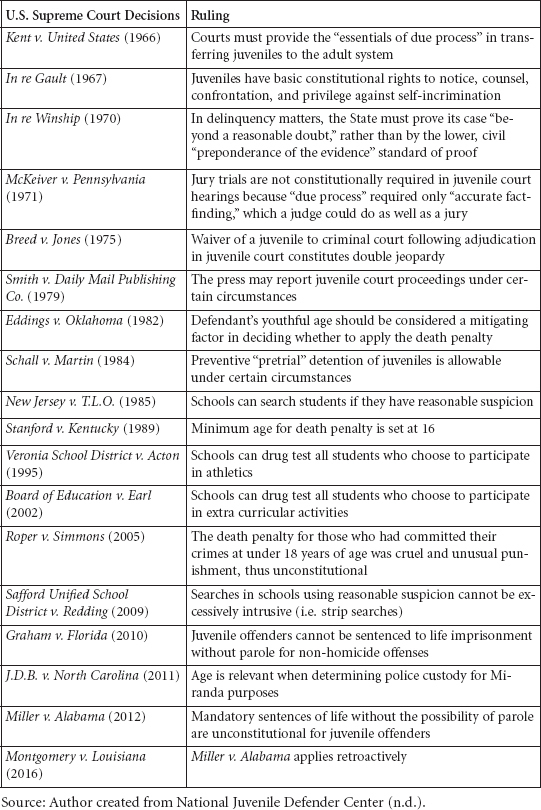

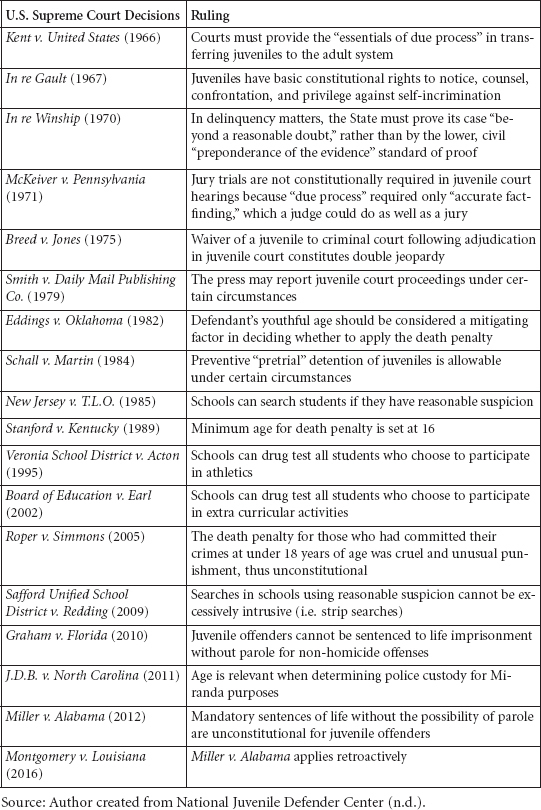

, or in place of the parent, to protect children from adult wrongdoers (Friedman, 1993). As public confidence in indefinite institutionalization (e.g., houses of refuge, reform schools) and the traditional treatment model waned during the 1950s and 1960s, however, formal procedural safeguards for youth were introduced and the juvenile justice system began to take on more characteristics of the adult criminal court. Many of these changes were in response to landmark U.S. Supreme Court decisions pertaining to juvenile justice (see

Table 6.1

).

In Minnesota, a comprehensive revision of the juvenile code in 1959 raised the minimum age of adult prosecution to age 14, where it currently remains (Minnesota Laws 1959 c 685 s 16). In 1973, Minnesota transferred control of juvenile offenders from the Youth Conservation Commission to the Commissioner of Corrections. However, diversion and deinstitutionalization were still the banners of juvenile justice policy (Feld, 2007).

Following a sharp increase in violent juvenile crime in the 1980s and 1990s, the pendulum began to swing toward law and order (Feld, 1984). Spurred by sensationalist media coverage of a “new breed” (DiIulio, 1995, p. 23) of “fatherless, Godless, and jobless”

juvenile superpredators

(Bennett, DiIulio, & Walters, 1996, p. 27) and an impending juvenile “crime wave storm” (Fox, 1996) that never actually materialized (see

Chapter One

), legislatures across the country limited judicial discretion and adopted a more punitive stance toward juvenile offenders. In 1980, for instance, the Minnesota legislature repudiated the “rehabilitative” commitment of the juvenile code to provide “care and guidance ...

as will serve the spiritual, emotional, mental and physical welfare of the minor and the best interests of the state” and repurposed the juvenile court “to promote the public safety and reduce juvenile delinquency ... by developing individual responsibility for lawful behavior” (Minnesota Statutes §260.011; Feld, 1981). As a result, the number of offenses for which a juvenile could be tried as an adult increased significantly.

Table 6.1. Landmark U.S. Supreme Court Decisions Pertaining to Juvenile Justice

The 1980s and 1990s were busy decades in juvenile justice policy in Minnesota (for a review, see Swayze & Buskovick, 2014a). In 1986, for example, the Minnesota legislature opened to the public delinquency hearings of juveniles 16 years of age or older and charged with a felony level offense (Minnesota Statutes §260.155). In 1991, a “crime committed for the benefit of a gang” was added to the Minnesota statute, thus creating sentencing enhancements for juveniles (see

Chapter Seven

). In 1994, Minnesota authorized a new tier of sentencing called Extended Juvenile Jurisdiction (EJJ), which allowed juveniles to be tried and sentenced in juvenile court, but receive stayed adult sentences. That same year, the legislature expanded juvenile certification, allowing 15-year-olds—now 14-year-olds—to be certified to adult court after showing that retaining the child in juvenile court would not serve public safety (Minnesota Statutes §260B.125). And in 1998, Minnesota created mandatory life imprisonment sentences for “heinous” crimes (Minnesota Statutes §609.106).

In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in

Miller v. Alabama

that mandatory life without parole sentences (LWOP) for juveniles convicted of homicide are unconstitutional. However, the Minnesota Supreme Court in 2013, and again in 2014, controversially ruled the

Miller

holding cannot retroactively apply to juveniles given mandatory life without parole sentences. This despite the fact the Minnesota branch of the Department of Justice already conceded

Miller

applies retroactively (Mazurek, 2015). As a result, juveniles within the state of Minnesota face disparate treatment depending on whether the state or federal government prosecutes them (Mazurek, 2015).

Juvenile Crime Data in Minnesota

Over thirty years of juvenile arrest data (

Figure 6.1

) illustrate that juvenile arrests in Minnesota increased 150 percent between 1982 and the peak year of 1998 (see Swayze & Buskovick, 2013). In 1998, there were 134 arrest events for each 1,000 youth aged 10 to 17 in the population. The number and rate of juvenile arrests for

violent crime

peaked in Minnesota and nationally in 1994 (see

Chapter Seven

). Conversely, between 1998 and 2011, juvenile arrests declined in Minnesota by over half (−55%). Ultimately, the number of arrests

in 2013 (36,192) was comparable to the number recorded in 1980 (36,008). Minnesota's juvenile arrest pattern, therefore, largely follows the national pattern during the same period, though the rise and fall are more pronounced in Minnesota than nationally (see

Chapter One

).

Consistent with national trends, the number of females in the Minnesota juvenile justice system has also increased over time. Between 1980 and 1990, females accounted for roughly 25 percent of all juvenile arrests. Between 2005 and 2010, females accounted for 33 percent of total juvenile arrests (Swayze & Buskovick, 2013). Of all violent crime, the most juvenile arrests are for aggravated assault followed by robbery. Despite media depictions, the least common juvenile violent crime is murder. Juvenile property crime totals in Minnesota are dominated by the larceny category, which includes all levels of theft ranging from low-level shoplifting to high-value products (Swayze & Buskovick, 2013).

Minnesota court data illustrate a 325 percent rise in juvenile petitions filed between 1984 and 1998, from approximately 15,0000 to more than 63,0000 (Swayze & Buskovick, 2013). Petitions are all cases brought to court in a given year, regardless of when the case comes to conclusion or whether there is a legal finding of guilt. While the number of juvenile petitions filed between 1998 and 2011 declined by 47 percent, the number of youth petitioned in 2011 (33,828) was still over twice the number recorded in 1980. Higher court volume in the 1990s and 2000s is partially attributable to improved data collection and reporting methodologies (namely the introduction of the Minnesota Court Information System [MNCIS] in 2003), but also the larger proportion of arrests petitioned to court than in the 1980s (Swayze & Buskovick, 2013). Many of these petitions are brought by law enforcement.

Youth involved in the juvenile justice system in Minnesota can be placed out of their homes with a Department of Corrections (DOC) or Department of Human Services (DHS) licensed provider after arrest, pending the outcome of court proceedings, or as a dispositional outcome when court-ordered to a residential program. The 50 percent decline in the use of combined secure (e.g., MCF–Red Wing, see

Chapter Four

) and non-secure correctional placements for juveniles in Minnesota between 2001 and 2010 corresponds to the decrease in juvenile arrests and petitions described above, but also the 1999 closing of Minnesota Correctional Facility–Sauk Centre, also known as the

Minnesota Home School

(Justice Policy Institute, 2013). Prior to closing in 1999, all female juvenile offenders under the jurisdiction of the DOC were housed at Sauk Centre. Today, a small number of serious female juvenile offenders are held in DOC contract facilities such as Woodland Hills in Duluth and the Dakota County Juvenile Services Center in Hastings (Swayze & Buskovick, 2013).

On January 1, 2014, there were 22 juveniles (20 males) committed to the Department of Corrections: 30% were for criminal sexual conduct, 15% for felony theft, 15% for burglary, and the remaining for other crimes (Minnesota House of Representatives, 2015). Furthermore, there were 7,477 under community supervision, of which 7,471 were on probation. A majority (87%) are supervised by local agents (Minnesota House of Representatives, 2015).

Figure 6.1. Total Minnesota Juvenile Arrests, 1980–2013

The Juvenile Justice System in Minnesota

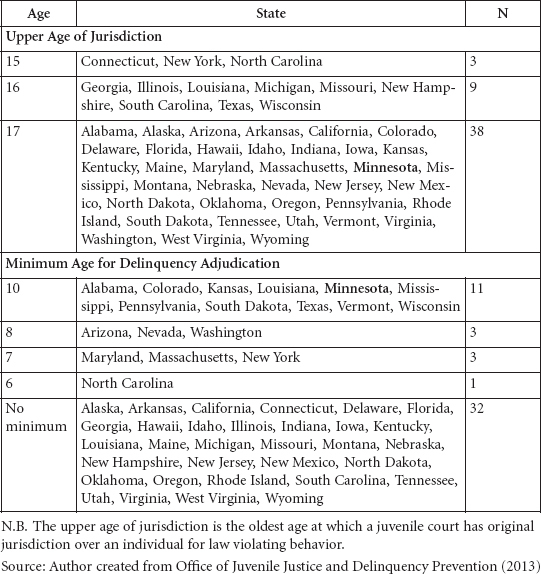

Youth under age 18 presently account for approximately 1.3 million of Minnesota's 5.4 million residents (Swayze & Buskovick, 2014a). Under Minnesota law, children under the age of 14 years are incapable of committing

crime

(Minnesota Statutes §609.055). Anyone who commits a crime when he or she is between the ages of 10 and 17 is considered a juvenile offender (see

Table 6.2

). With a few exceptions for especially violent crimes, most juvenile cases remain in the juvenile court. Younger children are referred to the child welfare system.

Table 6.2. Juvenile Age of Jurisdiction by State

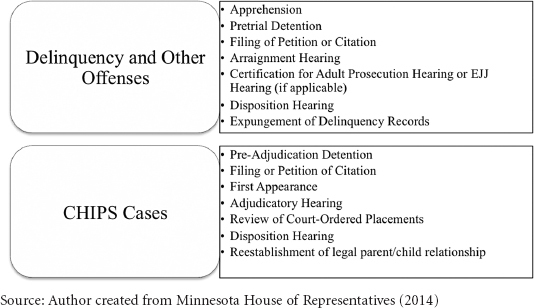

The juvenile court in Minnesota is authorized to hear cases involving 1) juveniles who commit unlawful acts and 2) Children in Need of Protection or Services (CHIPS) from or by the court, and as such there are two different processes (see

Figure 6.1

). When a juvenile falls under the first category of committing an unlawful act and he or she has not been certified to adult court or committed First Degree Murder, then he/she will be in one of four categories:

1)

Delinquent

—under 18 who commit acts that would be unlawful if committed by an adult except for petty offenses.

2)

Extended Jurisdiction Juveniles

—children 14 or older who commit felony-level delinquent act.

3)

Petty Offenders

—acts that are unlawful because of age (like drinking or smoking) and 1st or 2nd nonviolent misdemeanors (see section below labeled “petty offenses” for more detail).

4)

Juvenile traffic offenders

—age and offense may move the case to adult court.

Each of these categories is discussed below.

As for CHIPS cases, there are many reasons why a child would need protection and services from the court, some of which include: the child is abandoned; he/she needs food, clothing, and shelter; the child is medically neglected; the child is abused physically or sexually; the child is a habitual truant; the child has runway; the parents want to revoke their parental rights; and a child is exposed to criminal activity in the home (Minnesota House of Representatives, 2014).

The juvenile court is also responsible for such matters involving termination of parental rights, appointment and removal of guardians, juvenile marriages, adoption matters, foster care matters, persons who contribute to delinquency or neglect of minor, and reestablishment of legal parent and child relationship (Minnesota House of Representatives, 2014). Parental liability laws in Minnesota are limited, but in some situations parents may be civilly responsible for their children's acts. For example, a parent can be responsible for paying for theft (Minnesota Statutes §604.14), damages or injuries caused by their child up to a $1,000 (Minnesota Statutes §540.18), or $5,000 if the crime is bias motivated (Minnesota Statutes §611A.79). Parents are exempt only if they show they made a reasonable effort to control their child's behavior.

Figure 6.2. Court Process for Delinquency and CHIPS Cases

Delinquency

In juvenile court, a defendant is adjudicated

delinquent

rather than found guilty of a

crime

. A delinquent offense is an act committed by a juvenile for which an adult could be prosecuted in criminal court. A delinquent

adjudication

means there has been an admission of guilt by the youth or a legal finding of guilt by a judge; it is the juvenile equivalent of an adult conviction. Adjudications become part of a juvenile's formal criminal record and are often required in order for youth to be placed in certain correctional settings. This can be used to charge or enhance charges. For example, a juvenile is adjudicated on an assault in the first degree. Five years later, the juvenile is now an adult and was arrested for his or her first time as an adult with a firearm. Because of the criminal history showing the adjudication on the assault charge, he or she would be charged at a felony level instead of a possible misdemeanor.

In juvenile court, moreover, there is a

disposition

rather than a

sentence

. The disposition is generally focused on maintaining public safety, but more so rehabilitating the child and returning him or her to law-abiding behavior. Depending on the circumstances of the case, a judge has the ability to order a very broad range of consequences and programming such as:

- Probation supervision

- Restitution

- Community service (also referred to as Sentencing To Service or STS)

- Counseling

- Home detention

- Chemical dependency treatment

- Loss of driver's license

-

Placement at a residential juvenile correctional facility such as Boys Totem Town or the state juvenile correctional facility in Red Wing

(Hennepin County Attorney, 2015)

Minnesota has two case outcomes other than adjudication where the court may impose sanctions and supervision without a formal finding of responsibility:

continuance for dismissal

and

stay of adjudication

(Swayze & Buskovick, 2013). In both cases youth may receive court-imposed sanctions and must remain law abiding for a certain period of time to keep charges off their records. This philosophy is different from adult court where there is a greater focus at sentencing on what the punishment should be for a specific criminal act. Still, as with adult court, victims have a right to receive notice of charges, court proceedings, plea negotiations and dispositions (Hennepin County Attorney, 2015).

Other differences in the juvenile justice system compared to the adult system are that juveniles are generally not tried by a jury of one's peers, rather the judge makes the decision. The court proceedings are generally closed to the public to protect privacy. Parents are involved in the juvenile process. The entrance into the juvenile justice system, in addition to official action (arrest, summons, citation), can come from referral by parents, schools, or other interested parties. In addition to the differences in terms used for adults versus juveniles already highlighted, there are many more including such terms as: “Parole” vs. “aftercare,” “incarceration” vs. “commitment,” “halfway house” vs. “residential care facility,” “reduction of charges” vs. “substitution,” “jail” vs. “detention facility,” etc. And lastly, juveniles also do not have a right to bail; instead they are released to their parents or guardian.

Petty Offenses

The term

status offense

does not exist in Minnesota Statutes or Rules of Procedure, but local practitioners often use the term to describe acts by minors that are illegal by virtue of their age. A status offense is conduct that would not be a crime if committed by an adult. Examples include:

- Truancy—Minnesota Statutes §260A.02 defines continuing truancy as “absent from instruction in a school without valid excuse within a single school year for: (1) three days if the child is in elementary school; or (2) three or more class periods on three days if the child is in middle school, junior high school, or high school.”

- Curfew violations—Minnesota Statutes §245A.05 permits a county to adopt a curfew for any unmarried person under the age of 18 and for various times depending on age. For example, in the largest county in Minnesota, Hennepin, the curfew is 9PM for under 12 years old, 10PM for 12–14 years old, and 11PM for 15–17. On the weekends an hour is added to each (Hennepin County Attorney, 2015a).

- Running away

- Underage possession and/or consumption of tobacco products

- Underage alcohol offenses (N.B. The legal drinking age in Minnesota was 19 until 1986. Today, alcohol possession and use by adults aged 18–20 are crimes punishable under state criminal statutes and are not treated as status offenses.)

Females make up a large percentage of juvenile arrests for status offenses in Minnesota, including one-third of arrests for curfew violations and 50 to 60 percent of arrests for runaway (Swayze & Buskovick, 2013).

In Minnesota, the above are all considered

petty offenses

(Minnesota Statutes §260B.007). While petty offenders are under the delinquency chapter in statute and procedure, the statutes clearly state that petty offenders shall not be adjudicated delinquent. Most traffic offenses, low level theft, disorderly conduct, disturbing the peace, and low level property damage are also offenses which can, and often are, handled as misdemeanor-level petty offenses rather than as misdemeanors, which is their classification if committed by an adult (Hennepin County Attorney, 2015b). Likewise, abused and neglected youth, habitual truants and runaways, youth found in dangerous surroundings, youth engaged in prostitution, and youth committing delinquent acts before the age of 10 are adjudicated as Children in Need of Protection or Services (CHIPS, formerly “dependent and neglected youth”) and not adjudicated delinquent (Minnesota Statutes §260C.007).

Note, non-delinquents can be held in secure juvenile facilities based on “contempt of court” even when their underlying offense would not otherwise meet secure admission criteria. In 1980, the Minnesota Supreme Court ruled in

State ex rel. LEA v. Hammergren

that non-delinquent youth simply had to be notified in advance that failure to follow court conditions could result in secure confinement. The outcome of this decision was the “Hammergren Warning,” named after Donald Hammergren, former Hennepin County Juvenile Detention Facility Superintendent, which must be given by a judge in court, on the record, to this effect (Swayze, 2010).

Diversion

As of July 1995, all county attorneys in Minnesota are required to provide at least one juvenile-pretrial diversion program as an alternative to prosecution (Minnesota Statutes §388.24), although in practice county probation providers are most likely to operate said programs (Swayze & Buskovick, 2012a). Juvenile diversion helps eligible young people who have been cited or arrested for an offense to avoid a charge and a juvenile court record. Young people with little or no juvenile history who have been cited or arrested for a lower-level offense are eligible. So too are lower-level offenses include juvenile petty offenses, most misdemeanor and gross misdemeanor offenses, and with some exceptions, felony property offenses, although there is no uniform standard across Minnesota counties (Swayze & Buskovick, 2012a). Instead of going to court, the offender and his or her parent or guardian attend a diversion intake meeting, complete an assessment, and sign a diversion agreement (Hennepin County Attorney, 2015b).

The diversion agreement typically is a six month contract that requires the offender to accept responsibility for the offense, attend school, adhere to

household rules, remain law-abiding by not committing any new offenses, pay restitution to their victim(s), and participate in appropriate programs or services for their needs and circumstances (e.g., mental health and chemical dependency treatment). Although the juvenile is required to accept responsibility for his or her actions, there is no formal guilty plea or record of an admission (Hennepin County Attorney, 2015b). If the youth follows the conditions of that contract, moreover, there is no charge and no juvenile court record. If the youth chooses not to participate or does not follow the conditions of the diversion contract, however, the case is charged and brought to juvenile court.

Adult Certification

When an offense is particularly serious or violent, a juvenile may be certified as an adult and tried in adult criminal court (Minnesota Statutes §260B.125). Minnesota adopted the term certification as a part of the 1994 Juvenile Court Act. Under the terms of the law, the juvenile must be at least 14 years old, charged with a felony and be a violent or habitual offender to be certified. First-degree murder, however, gives the adult court original jurisdiction (Minnesota Statutes §260B.007, subd. 6(b)). In other words, a 16- or 17-year-old charged with first-degree murder is automatically tried as an adult. Several other offenses, such as a felony with a firearm, are termed “presumptive” in that it is presumed that the 16- or 17-year-old will be certified as an adult. Under these circumstances, the prosecutor can file motions for adult certification or Extended Juvenile Jurisdiction (EJJ), which allows the court to keep the juvenile in juvenile court until he or she is 21 years old (Hennepin County Attorney, 2015b). Approximately 100 youth each year are certified to stand trial as adults in Minnesota, and in the past decade over 300 inmates who were certified as adults at the time of sentencing have been housed in Minnesota prisons (Swayze & Buskovick, 2013). Minnesota Statutes §641.14 makes it clear that a minor cannot be detained or confined with adults unless he or she has been indicted for first-degree murder, certified for trial as an adult, or convicted as an adult.

Blended Sentencing

Extended Juvenile Jurisdiction (EJJ) is Minnesota's blended sentencing option intended to retain youth who qualify for adult certification in the juvenile system. Under EJJ, youth can remain under the jurisdiction of the juvenile court until their 21st birthday. An EJJ designation gives a youth both a juvenile

disposition and a stayed adult sentence. In the event an EJJ youth commits a new offense or violates their conditions of probation supervision, their EJJ status can be revoked with due process, and the adult sentence imposed (Hennepin County Attorney, 2015b).

Approximately 200 to 250 youth are adjudicated EJJ annually (Swayze & Buskovick, 2013). In order to be eligible for EJJ designation, youth must have committed a felony level offense while between the ages of 14 and 17. A prosecutor then either petitions the case with an EJJ motion, petitions the case with an adult certification motion, or chooses to allow the case to proceed in juvenile court. In cases where the offense is a “presumptive certification” and adult certification is not imposed, EJJ designation is the alternative disposition (Minnesota Statutes §260B.130).

Juvenile Probation

As introduced in

Chapter Four

, Minnesota has three delivery systems for the supervision of all adult and juvenile offenders on parole, probation, and supervised release (intensive and regular) as established under the Department of Corrections Contract, the County Probation Act (Minnesota Statutes §244.19) and the Community Corrections Act (Minnesota Statutes §41) (see

Table 6.3

). Each delivery system dictates how services are paid for and how probation staff are employed (see Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2007). In 27

Department of Corrections

(DOC) counties, DOC field agents supervise all adult and juvenile offenders of all offense levels. In 28

County Probation Officer

(CPO) counties, probation officers appointed by the judiciary of the district court supervise all adults and juveniles with the exception of adult felons, who are supervised by DOC agents. And in 32

Community Corrections Act

(CCA) counties, probation officers hired by the county's Community Corrections Department supervise all adult and juvenile probationers of all offense levels.

Under statute and established rules of procedure, youth do not have to be adjudicated delinquent in Minnesota to be placed on probation. Supervision can be a part of a continuance for dismissal disposition as well as a stay of adjudication disposition. The numbers of Minnesota youth on probation peaked at 18,000 in 1999, but has since fallen over 50% to approximately 8,500 in 2013, comparable to figures in the mid 1980s. Declining court volume is one factor in declining juvenile probation volume in Minnesota (Swayze & Buskovick, 2013).

Table 6.3. Court Services Delivery Systems in Minnesota

Core Protections for Juveniles

The federal Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act of 2002 requires that Minnesota monitor its juvenile justice system for four core protections for youth, three of which are related to the appropriate use of secure detention facilities for accused and adjudicated youth (Swayze, 2010). Specifically, the act requires:

- The deinstitutionalization of non-offenders and status-level offenders from secure facilities;

- The removal of delinquent youth from adult jails and police lockups;

- And that juveniles be sight and sound separated from adult inmates whenever they are held in the same facility.

A fourth protection requires that states monitor their juvenile justice system for the over-representation of youth from communities of color, known as Disproportionate Minority Contact (DMC). DMC has shown to exist in most states throughout the U.S. (Kempf-Leonard, 2007). As discussed in

Chapter Four

, youth of color are disparately represented at all stages of justice-system processing in Minnesota. Further, the level of disparity in Minnesota is more severe than

both the national average and comparable states (Swayze & Buskovick, 2012c). In 2010, for example, 44 percent of total juvenile arrests were youth of color compared to just 12 percent in 1980. While the population of youth of color has increased from 5 percent to 22 percent of youth ages 10 to 17, youth of color are still substantially overrepresented in Minnesota at the point of arrest (Swayze & Buskovick, 2013).

Child Abuse and Neglect

In September 2015, Minnesota Vikings running back Adrian Peterson, one of the National Football League's top stars, was charged with one count of reckless or negligent injury to a child, a felony, for disciplining his 4-year-old son with a switch. The case was eventually pled down to a single charge of reckless assault, a misdemeanor, but Peterson still missed the entire NFL season and suffered untold damage to his once stellar reputation. More importantly, his actions shone a national spotlight on the fine line between discipline and abuse (Zinser, 2014).

For much of history there were no laws protecting children from physical abuse from their parents, to the extent that the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to

Animals

brought the very first case in New York in 1874 (Markel, 2009). Today, Minnesota, acting as a parent, has the authority to intervene in cases involving child abuse and neglect. Child

abuse

is the mistreatment (sexual, physical, or mental) of anyone below 18 years old, whereas

neglect

is when a child is denied basic necessitates or is not provided proper protection or supervision (Minnesota Statutes §626.556). The Minnesota Maltreatment of Minority Act further defines what constitutes each of these behaviors, as outlined in

Table 6.4

. Anyone who knows of cases involving child abuse and neglect should report a case. There are several people who are required by law to report a suspected case of abuse and neglect, including clergy, educators, health care, law enforcement, child care workers, mental health professionals, social services, guardians

ad litem

(see next section), and correctional staff (Minnesota Statutes §626.556, subd. 3). The Child Safety and Permanency Division of the Minnesota Department of Human Services has

A Resource Guide for Mandated Reporters

(2012) to ensure mandated reporters know the process for reporting and associated laws and policies.

The Minnesota Department of Human Services (2015) works with social service agencies in each of the 87 counties and 11 tribal lands in Minnesota who deal with child maltreatment. In 2013, 19,000 reports of child maltreatment were made throughout the state, of which three quarters of the

reports received a family

assessment

and the remaining a family

investigation.

The later is for when a family will not participate in an assessment or when

a child is in immediate or significant danger. After an investigation, if the findings are such, a petition may be filled with the court and brought to a CHIPS Court. In 2000, the Children's Justice Initiative was formed by the Minnesota Supreme Court and the Minnesota Human Services to ensure that any decisions/recommendations made should be from the “eyes of the child” and must achieve at least one of the following: (1) child safety; (2) child stability; (3) permanency for the child; (4) timeliness of process; (5) system accountability; and/or (6) due process protection for the parties (Minnesota Judicial Branch, 2015).

Table 6.4. Behaviors that Constitute Abuse or Neglect

In addition to child abuse and neglect cases, there are several laws in Minnesota that define certain acts committed with or against children as crimes or petty misdemeanors. These acts include such things as providing a tattoo to a minor without parental consent (Minnesota Statutes §146B.07; §645.241), allowing a child to tan with ultraviolet light (Minnesota Statutes §325H.01–325H.10), giving a lottery ticket to someone under the age of 18 (Minnesota Statutes §240.13), a pawnbroker making a purchase from someone under the age of 18 (Minnesota Statutes §325J.08), and marrying someone under the age of 18 without parental consent (Minnesota Statutes §609.265).

Guardians ad Litem

Guardians

ad litem

(GAL) are objective adults, court-appointed to serve as advocates for children involved in a court case. In legal terms, GAL means “guardian of the lawsuit” (State Guardian ad Litem Board, 2013). GAL are spokespersons for the short- and long-term

best interests of the child

appointed in different kinds of cases, including child abuse and neglect cases filed in Juvenile Court (Minnesota Statutes §260C.163), and divorce or custody cases filed in Family Court (Minnesota Statutes §518.165).

Guardians

ad litem

in Minnesota include specially trained community volunteers and state employees. They are reimbursed for services at the following rates:

As outlined by the State Guardian ad Litem Board (2013a), GAL are different from legal guardians because they have no control over the person or property of the child and do not provide a home for the child. GAL also do not function as the child's attorney and provide direct services to the child. Instead, they gather information. GAL interview and observe children and their families. They review social service, medical, school, psychological and criminal records and reports. They attend meetings with the other professionals involved with the children and their families. They outline options and make non-binding written and oral

recommendations

to the court to enable the court to make the best possible decisions. Finally, GAL monitor court ordered plans to ensure children's best interests are being met.

The GAL program emerged in Minnesota following the Federal Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act mandate in 1974. With no obvious state agency to administer a statewide GAL program, however, Minnesota delegated responsibility to individual district courts and counties, resulting in a decentralized system. In 1995, in response to concerns raised by citizens to the Legislature about this system, the Office of the Legislative Auditor (1995, p. 47) conducted a statewide review of GAL services and in their report concluded:

There are 53 local (county-funded) programs. There is little consistency in how counties recruit, select, and supervise guardians. There is no standard training, no system to process complaints and no uniform procedures to remove a GAL. The Supreme Court needs to develop broad guidelines addressing recruitment, selection, supervision, and evaluation for programs to use in administering their program.

Since the Legislative Auditor's Report, there have been a series of reforms to the GAL system, including Rules of GAL Procedure; mandatory statewide training requirements and administrative standards to improve performance and accountability; and an independent GAL Board, thus moving the program outside of the court system (Minnesota Statutes §480.35).

Bullying and School Violence

For most of the year, children spend more time at school than anywhere else other than their own home. School safety, therefore, is of paramount concern. Violence prevention education has been a mainstay of Minnesota schools since 1992, but only since 2005 have all Minnesota school boards been required to adopt a written policy prohibiting the intimidation or bullying of any student (Swayze & Buskovick, 2014a). After Governor Tim Pawlenty vetoed

an anti-bullying measure in 2009, however, Minnesota policy-makers have argued over proper language and measurements that would outline legislation aimed at improving student safety (McGuire, 2015). It took a potential lawsuit against the Anoka-Hennepin school district, Minnesota's largest, for failing to prevent bullying taking place within its schools, to finally force the issue, resulting in the 2014 Safe and Supportive Schools Act (Minnesota Statutes §121A.031).

The Safe and Supportive Schools Act replaced a 37-word anti-bullying law that was widely considered one of the nation's weakest (McGuire, 2015). The new law requires school districts to track and investigate cases of bullying and train teachers and administrators to prevent it (McGuire, 2014). The new law also includes the following components:

- A clear definition of bullying and intimidation;

- Various protective measures for students who are more likely to be bullied or harassed because of their race, color, creed, religion, disability, sex, age etc.; and

-

Specific procedures school staff must follow when an incident of bullying is reported.

(Outfront Minnesota, 2013)

School districts are not required to keep data they gather on bullying or report it, nor require mandatory training for school volunteers. Further, schools are only required to adopt the new legislation if they do not already have an anti-bullying plan in place (McGuire, 2014). Whether or not the new law will reduce bullying within Minnesota schools, therefore, remains to be seen.

Endemic bullying is of course not the only safety concern in Minnesota schools. The 1999 Columbine High School massacre in Columbine, Colorado, and the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Newtown, Connecticut, are two of the most infamous cases of school violence in America (see Fox & DeLateur, 2014), but Minnesota too has had school shootings (Swayze & Buskovick, 2014b). The first occurred in 1966 in the northern Minnesota town of Grand Rapids. A 15-year-old middle school student shot another student and killed a school administrator in the parking lot at the start of the school day. The first

high profile

school shooting was in 2003 when a freshman opened fire at Rocori High School in the town of Cold Spring, killing two students. But the

most

high profile Minnesota case is the 2005 Red Lake Indian Reservation spree killing (see

Chapter One

), which resulted in the death of two adults in the community and seven people at the high school, including an unarmed security guard at the entrance of the building, a teacher, and five students. Seven other people were injured.

Generally speaking, the safest place for children to be is in school (Robers et al., 2014), but extreme cases such as those aforementioned raise the specter of dangerous schools. Following the Red Lake shooting, for instance, Minnesota established the School Safety Center (MnSSC) within the Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Management and schools began adding

lock-down drills

to their crisis management policies (Swayze & Buskovick, 2014a). Following the 2012 Newtown shootings, which killed 20 children and 6 adult staff members, moreover, National Rifle Association spokesman Wayne LaPierre called for armed guards in every school (Fox & DeLateur, 2014). Civilian teachers from 15 states signed up for armed teacher training. And schools across the country began cracking down on supposedly troublesome behaviors, from making a “gun out of Lego” to playing “cops and robbers” in the playground (Densley, 2013). In reality, however, school crime and violence has been decreasing locally and nationally for two decades (Robers et al., 2014).

Law enforcement has long been present in Minnesota schools (Swayze & Buskovick, 2014b). Minneapolis developed one of the nation's first Police School Liaison Programs (PSLP) in 1967 and through local programs, but also the federal Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E., see Ennett et al., 1994) and Gang Resistance Education and Training (G.R.E.A.T., see Esbensen et al., 2013. See also

Chapter Seven

for a discussion of juvenile gangs) programs in the 1980s and 1990s, respectively, police entered schools in a crime prevention role. It was not until the late 1990s that formal School Resource Officer (SRO) programs to place cops in classrooms emerged. Between 1999 and 2005, for example, 77 Minnesota law enforcement agencies received federal grants to fund the creation of new SRO positions (Swayze & Buskovick, 2014b).

A 2013 survey of SROs in Minnesota schools found that nearly 3-in-10 public schools have them (Swayze & Buskovick, 2014b). In high schools, it is as high as 6-in-10. Minnesota SROs self-reported enjoying working with youth and school staff and believing they are used appropriately in schools. Many reported their SRO work was the most rewarding and useful law enforcement position they ever held. There are challenges, however, such as defining and adhering to the role of SROs in schools; adequate training in youth development and how to interact effectively with children and youth at various developmental stages; and ways to work in partnership with youth, school staff, and the parents of students (Swayze & Buskovick, 2014b).

Survey authors Swayze and Buskovick (2014b) offer six recommendations to improve SRO programs. First, law enforcement agencies should ensure that officers assigned to be SROs are highly motivated to perform this work. Second,

schools and law enforcement agencies should develop a memorandum of understanding that states SROs' roles and duties. Third, SROs should be well-trained in preparation for SRO duties. Fourth, SROs and school staff should be cross-trained, so as to facilitate informed cooperation between SROs and school staff. Fifth, SROs should give high priority to preventing crime and disorder in schools rather than focusing on a reactive response after incidents have occurred. Sixth, the impact of SROs on school security and safety should be appropriately evaluated.

There is no clear evidence SROs or other measures such as metal detectors, random searches, drug-sniffing dogs, radio frequency monitors, and surveillance cameras make schools safer (Mukherjee, 2007). Some studies have found a decrease in violence in schools with in-house police officers, while others have found no relationship at all (American Psychological Association, 2006). Part of the problem is that police officers are trained in how to deal with conflict, not how to counsel youth and defuse typical adolescent drama. Student problems, in turn, are redefined as criminal issues requiring a criminal justice response (Na & Gottfredson, 2013; Theriot, 2009). And student problems increase because suspension, expulsion, arrest, etc., fail to address the underlying social and psychological causes of student misbehavior (Densley, 2013). Students cannot speak to appropriate adults if their problems involve criminal activity (e.g., drug use) for fear they will be punished under “zero tolerance” polices that automatically impose severe punishment regardless of circumstances (Skiba & Knesting, 2001).

Indeed, young people throughout the country have been punished for infractions to zero tolerance policies where the intent to commit harm was not readily present. In Anoka, Minnesota, for example, a high school student was suspended for ten days because he left a box cutter in his car that he used for work at a grocery store. Having the box cutter on school grounds was a violation of the school's zero tolerance policy (Kroman, 2008). In 2014, the Obama Administration sent a message to schools to end zero tolerance policies because of their costly disparities and practice. Recommendations were provided to include training in conflict resolution and de-escalation techniques and to more clearly articulate the responsibilities of security personnel to increase understanding about what constitutes a school infraction versus a threat to school safety (Associated Press, 2014).

In his 2010 book,

Homeroom Security: School Discipline in an Age of Fear

, sociologist Aaron Kupchik finds, “the presence of police in schools is unlikely to prevent another school shooting and the potential for oppression of students—especially poor and racial/ethnic minority youth—is a more realistic and common threat than Columbine” (p.82). Indeed, some, including St.

Catherine University professor Katherine Heitzeg (2009), argue too broad educational policies that disproportionately penalize students of color compared to their white peers and lead to school suspension or expulsion constitute a “schoolhouse to jailhouse track” or “school to prison pipeline” (see also, Petteruti, 2011). During the 2012–13 school year, approximately 12% of disciplinary incidents in Minnesota schools, involving 5,476 unique students, involved a referral to law enforcement. It is unknown how many referrals to law enforcement resulted in a formal citation or charges (Swayze & Buskovick, 2014b).

Youth Intervention Programs

A 1974 survey of 231 studies on offender rehabilitation headed by New York sociologist Robert Martinson concluded, “with few and isolated exceptions, the rehabilitation efforts that have been reported so far have had no appreciable effect on recidivism” (p. 25; see also, Lipton, Martinson, & Woks, 1975). In short order, and despite the fact the phrase never appeared in the original report, Martinson's survey came to be known simply as the “nothing works” study (Wilson, 1980). The supposedly incontrovertible truth that

nothing works

in rehabilitating offenders appealed to Left and Right alike (Cullen & Jonson 2009, p. 294). Liberals used the idea to justify an end to indeterminate sentencing tied to vague rehabilitation criteria such as “attitudinal change.” Conservatives used the idea to promote retributive

tough on crime

policies such as mandatory prison terms and capital punishment. Two decades of punitive juvenile justice policy practice from “scared straight” programs to correctional boot camps followed (Kleiman, 2009).

The problem was, the null results noted by Martinson and colleagues were tied more to

process

issues of program fidelity (i.e., inappropriate management and implementation) than

outcome

issues of program effectiveness (Cullen & Jonson, 2009). A deeper read of the original study also reveals some rehabilitative programs could be successful contingent upon how success is defined. However, the

nothing works

doctrine took hold, so much so that when Gendreau and Ross (1987) found in fact

many things work

, their findings were discredited and largely dismissed (see Cullen & Jonson, 2009).

As crime continued to rise in the 1990s, and local, state, and federal agencies threw more and more money at the problem, there was increasing recognition that our thinking is really little more than models and interpretations (Barnes, 1990) and funding for crime control programming had to be tied to rigorous and scientifically recognized standards of evidence. One good thing that came out of the “nothing works” ideology was researchers developed more

robust means to explain why some interventions were effective and others were not (e.g., Andrews et al., 1990). In 1995, for instance, the National Institute of Justice commissioned an independent review of over 500 program impact evaluations, which concluded, “some prevention programs work, some do not, some are promising, and some have not been tested adequately” (Sherman et al., 1998, p. v). Finally,

something worked

, just not the punitive “scared straight,” “shock incarceration,” and “boot camp” programs that supplanted rehabilitation during the

nothing works

era. Instead, what worked were programs dedicated to ameliorating underlying

risk factors

at the individual, family, peer, school, and community levels that statistically increase the likelihood of juvenile delinquency (Sherman et al., 1998).

The language of risk factors dominates contemporary discussions of crime prevention (Sherman et al., 2006). In Minnesota, for example, the Risk-Needs-Responsivity (R-N-R) model underlines much juvenile probation policy and practice (Andrews, Bonta, & Hoge, 1990). The risk principle states the level of service should match a juvenile's risk of reoffending. High-risk offenders get more intervention while low-risk offenders receive minimal or no intervention. The need principle states static (e.g., criminal history) and dynamic (e.g., social networks) risk factors should be assessed using actuarial assessment tools such as the Youth Level of Service/Case Management Inventory 2.0 (Hoge & Andrews, 2011) and treatment should be focused on individual

criminogenic needs

such as substance abuse (Andrews & Bonta, 2006). Finally, the responsivity principle essentially entails providing the right treatment at the right level. Agencies provide

cognitive behavioral treatment

, for instance, to maximize a youth's ability to learn from rehabilitative intervention or strength-based services such as

motivational interviewing

to engage families and other key stakeholders in a youth's recovery. However, Minnesota agencies do not always adhere to the R-N-R model. In many counties, for instance, juvenile sex offenders or high profile offenders are supervised at an intense level regardless of risk.

In 2003, Minnesota implemented mental health screenings for most justice system involved youth, contingent upon active parental consent (Minnesota Statutes §260B.157). Further guided by R-N-R thinking, several Minnesota jurisdictions now limit use of out-of-home placement, providing culturally- and gender-responsive programming in the least restrictive setting necessary to protect public safety (Swayze & Buskovick, 2014a). In 2005, for instance, three of Minnesota's largest counties—Dakota, Hennepin, and Ramsey—adopted the Annie E. Casey Foundation's (2015) Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative (JDAI) to divert youth from secure confinement and ensure admissions relied upon objective, validated risk-assessment tools that ascertain risk to

public safety (Swayze & Buskovick, 2014a). St. Louis County joined the initiative in 2009.

Specialty courts and diversion programs once deemed “soft” on crime also appear to be gaining a foothold (see

Chapter Three

). Teen courts, for instance, offer a dispositional alternative to the traditional juvenile justice system in which the young offenders' teenage peers hear facts surrounding the incident, deliberate, and determine a disposition, which often includes community service or alcohol or drug treatment (Butts & Buck, 2000). Teen courts are based on assumptions that (a) if antisocial peers can increase antisocial behavior then pro-social peers can encourage pro-social behavior and (b) adolescents are more likely to be influenced by their peers as opposed to adult authority figures in the formal juvenile justice system (Butts & Buck, 2000). In simple terms, teen courts harness the power of positive peer pressure. There are presently no definitive studies about teen court outcomes, and some concerns exist about selection bias in the system, but results are generally positive (see Butts et al., 2012).

In 1976, the Minnesota State Legislature created the Youth Intervention Program (YIP) to provide financial resources to “Youth Intervention Programs.” By statute,

Youth Intervention Program means a nonresidential community-based program providing advocacy, education, counseling, mentoring, and referral services to youth and their families experiencing personal, familial, school, legal, or chemical problems with the goal of resolving the present problems and preventing the occurrence of the problems in the future.

(Minnesota Statutes §299A.73 Subd. 1)

The 25 organizations that initially received State YIP funding established the Minnesota Youth Intervention Programs Association (YIPA) in 1978 and in 1984 incorporated as a 501(c) (3) nonprofit. YIPA does not directly serve youth, but rather the practitioners and organizations that do. YIPA offers professional development for youth intervention organizations and workers, a forum for collaboration, and advocacy for funding and support for programs throughout Minnesota. In 2012, 51 programs across Minnesota were selected to receive YIP funding (Swayze & Buskovick, 2012b). In addition to the programs identified under YIP, there are many other school, religious, sports, recreation, music, arts, scouting, etc. programs in Minnesota that work with youth to help prevent them from committing crimes in the first place or help them to stop committing further crime.

As mentioned in

Chapter One

, restorative justice has strong roots in Minnesota. This is especially true for responding to juvenile offenders because of

diversion. Juveniles engage in restorative justice practices (victim-offender dialogue, conferencing, and circle work) through non-profit agencies to address their individual cases. Incorporating the value of community, offenders engage in the above processes providing conscious healing and culturally relevant responses to harm, which has been identified as a diversionary best practice (Swayze & Buskovick, 2012a). Cass County, in conjunction with the Leech Lake Tribal Court, is a great example of a best practice in providing diversion for first time offending youth. A panel of reservation community members meet with the juvenile and incorporate Ojibwe teachings to respond to the offense. The youth then returns to the community panel with a presentation of their choice illustrating their reflection of the Ojibwe values discussed and their connection realization of the harm as a result of their offense. Another example is in Carver County, where a Youth Empowerment Circle had been created to allow offenders encountering barriers to payment to participate in a circle process to earn monetary credit. These types of programs assist in providing the diversion of further court proceedings and probation revocation for the juveniles while incorporating a community, value-oriented and restoration-focused approach for the psychosocial development of the youth.

Youth involvement in crime in Minnesota is at low levels not see since the 1980s. Is this a lull or a permanent change? Is Minnesota's juvenile justice system working? Perhaps. But we cannot forget those currently in the system. What are their needs? Many juvenile offenders in Minnesota have suffered one or more adverse childhood experiences such as abuse, having a mentally ill parent, domestic violence against a parent, a household member in prison, divorced parents, or a household member with a drug or alcohol problem (Swayze & Buskovick, 2012d). Likewise, many juvenile offenders were themselves victims of crime or exposed to one or more traumatic events that threatened or caused great physical harm in childhood (Swayze & Buskovick, 2012d). The prevalence of trauma in the lives of young people has led to calls for

trauma-informed

juvenile justice that takes steps to reduce the lasting and substantial collateral costs of incarceration on youth—potentially the next evolutionary stage in the system.

Keywords

Abuse

Adjudication

Adult Certification

Age of Jurisdiction

Age-Crime Curve

Blended Sentencing

Bullying

Child Abuse

Children in Need of Protection or Services (CHIPS)

Community Corrections Act

Continuance for Dismissal

County Probation Act

Delinquent

Disposition

Disproportionate Minority Contact

Diversion

Extended Juvenile Jurisdiction (EJJ)

Hammergren Warning

Guardians ad litem

In loco parentis

Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative (JDAI)

Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act of 2002

Mandated Reporter

Mens rea

Neglect

“Nothing Works”

Parental Liability

Parens patriae

Petty Offense

Procedural Justice

Rational Choice Theory

Risk-Needs-Responsivity (R-N-R)

School Resource Officer

School Shootings

School to Prison Pipeline

Social Bond Theory

Social Learning Theory

Stay of Adjudication

Strain Theory

Superpredator

Trauma

Youth Intervention Program

Zero Tolerance

Selected Internet Sites

Discussion Questions

- What is the relationship between crime and age?

- Do you think we even need a separate juvenile court system? Why/why not?

- What are some of the key differences between the adult and juvenile justice process?

- What do you think is the most important action a parent can do to help their children not become criminal?

- Under what circumstances, if any, do you think juveniles should be waived to adult court?

- What do you think should be the punishment for a parent found guilty of neglecting their children and why?

- What can/should schools do to help stop bullying and prevent violence?

- Do you think juveniles should have a right to a jury trial?

- Do you think parents should be held civilly liable for their children's behavior?

References

Agnew, R. (1992). Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency.

Criminology

, 30, 47–87.

Akers, R. (2009).

Social learning and social structure: A general theory of crime

. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

American Psychological Association. (2006).

Are zero tolerance policies effective in the schools? An evidentiary review and recommendations

. Washington DC: Author.

Andrews, D., & Bonta, J. (2006).

The psychology of criminal conduct

(4th ed.). Newark, NJ: LexisNexis.

Andrews, D., Bonta, J., & Hoge, R. (1990). Classification for effective rehabilitation: Rediscovering psychology.

Criminal Justice and Behavior, 17

, 19–52.

Andrews, D., Zinger, I., Hoge, R., Bonta, J., Gendreau, P., & Cullen, F. (1990). Does correctional treatment work? A psychologically informed meta-analysis. C

riminology, 28

, 369–404.

Barnes, J. (1990).

Models and interpretations

. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Becker, H. (1963).

Outsiders: studies in the sociology of deviance

. New York: Free Press.

Bennett, W., Dilulio J., & Walters, J. (1996).

Body count: moral poverty, and how to win America's war against crime and drugs

. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Bonnie, R. & Scott, E. (2013). The teenage brain: Adolescent brain research and the law.

Current Directions in Psychological Science

, 22, 158–161.

Butts, J., & Buck, J. (2000).

Teen courts: A focus on research

. OJJDP Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice.

Butts, J., Roman, J., & Lynn-Whaley, J. (2012). Varieties of juvenile court: Non-specialized courts, teen courts, drug courts, and mental health courts. In B. Feld and D. Bishop (Eds.),

Oxford Handbook of Juvenile Crime and Juvenile Justice

(pp. 606–635). New York: Oxford University Press.

Cornish, D. & Clarke, R. (1986).

The reasoning criminal: rational choice perspectives on offending

. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Cullen, F. & Jonson, C. (2011). Rehabilitation and treatment programs. In J. Wilson & J. Petersilia (Eds.),

Crime and public policy

(pp. 293–344). New York: Oxford University Press.

Dilulio, J. (1995). The coming of the super-predators.

The National Review

, November 27, 23–28.

Ennett, S., Tobler, N., Ringwalt, C., & Flewelling, R. (1994). Resistance education? A meta-analysis of Project D.A.R.E. outcome evaluations.

American Journal of Public Health

, 84, 1394–1401.

Esbensen, F-A, Osgood, D., Peterson, D., Taylor, T., & Carson, D. (2013). Short- and long-term outcome results from a multisite evaluation of the G.R.E.A.T. program.

Criminology & Public Policy

, 12, 375–411.

Fagan, J., & Tyler, T. (2005). Legal socialization of children and adolescents.

Social Justice Research, 18

, 217–241.

Farrington, D., Piquero, A, & Jennings, W. (2013).

Offending from childhood to late middle age: Recent results from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development

. New York: Springer.

Feld, B. (1981). Juvenile court legislative reform and the serious young offender: Dismantling the ‘rehabilitative ideal.’

Minnesota Law Review

, 65, 167.

Feld, B. (1984). Criminalizing juvenile justice: Rules of procedure for the juvenile court.

Minnesota Law Review

, 69, 141.

Fox, J. & DeLateur, M. (2014). Mass shootings in America: Moving beyond Newtown.

Homicide Studies

, 18, 125–145.

Friedman, L. (1993).

Crime and punishment in American history

. New York: Basic Books.

Gendreau, P. & Ross, R. (1987). Revivification of rehabilitation: Evidence from the 1980s,

Justice Quarterly

, 4, 349–407.

Goffman, E. (1963).

Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity

. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Gottfredson, M., & Hirschi, T. (1990).

A general theory of crime

. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Hirschi, T. (1969).

Causes of delinquency

. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hirschi, T, &. Gottfredson, M. (1983). Age and the explanation of crime.

American Journal of Sociology

, 89, 552–584.

Hoge, R. & Andrews, D. (2011).

Youth level of service/case management inventory 2.0

. Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems Inc.

Katz, J. (1988).

Seductions of crime: Moral and sensual attractions in doing evil

. New York: Basic Books.

Kempf-Leonard, K. (2007). Minority youths and juvenile justice: Disproportionate minority contact after nearly 20 years of reform efforts. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 5(1), 71–87.

Kleiman, M. (2009).

When brute force fails: How to have less crime and less punishment.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kupchik, A. (2010).

Homeroom security: School discipline in an age of fear

. New York: NYU Press.

Lemert, E. (1971).

Instead of court: diversion in juvenile justice

. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health.

Lipton, D., Martinson, R., & Wilks, J. (1975).

The effectiveness of correctional treatment: A survey of treatment valuation studies

. New York: Praeger Press.

Martinson, R. (1974). What works? Questions and answers about prison reform.

The Public Interest

, 35, 22–54.

Mazurek, A. (2015). Criminal law: No looking back: Narrowing the scope of the retroactivity doctrine for juveniles sentenced to life without release—Roman Nose v. State.

William Mitchell Law Review

, 41, 330–365.

Merton, R. (1938). Social structure and anomie.

American Sociological Review

, 3, 672–682.

Miller v. Alabama

, 567 U.S. ___ (2012).

Moffitt, T. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course persistent anti-social behavior: A developmental taxonomy.

Psychological Review

, 104, 674–701.

Mukherjee E. (2007).

Criminalizing the classroom: The over-policing of New York City schools

. New York: New York Civil Liberties Union.

Na, C. & Gottfredson, D. (2013). Police in schools: Effects on school crime and the processing of offending behaviors.

Justice Quarterly

, 30, 619–650.

Office of the Legislative Auditor. (1995).

Guardians ad litem

. St. Paul, MN: Program Evaluation Division, State of Minnesota.

Petteruti A. (2011).

Education under arrest: The case against police and schools

. Washington, DC: Justice Policy Institute.

Robers, S., Kemp, J., Rathbun, A., & Morgan, R. (2014).

Indicators of school crime and safety: 2013 (NCES 2014-042/NCJ 243299)

. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, and Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice.

Robins, L. (1978). Sturdy childhood predictors of adult antisocial behavior: Replications from longitudinal studies.

Psychological Medicine

, 8, 611–622.

Sutherland, E. (1947).

Principles of criminology (4th edition)

. Philadelphia, PA: Lippencott.

Scott, E. & Steinberg, L. (2010).

Rethinking juvenile justice

. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sherman, L., Farrington, D., Walsh, B., & MacKenzie, D. (Eds). (2006).

Evidence-based crime prevention

(Revised Edition). London: Routledge.

Sherman, L., Gottfredson, D., MacKenzie, D., Eck, J. Reuter, P., & Bushway, S. (1998).

Preventing crime: what works, what doesn't, what's promising, a report to the United States congress

. Washington DC: National Institute of Justice.

Skiba, R. & Knesting, K. (2001). Zero tolerance, zero evidence: An analysis of school disciplinary practice.

New Directions for Youth Development

, 92, 17–43.

State Ex Rel. LEA v. Hammergren

, 294 N.W.2d 705 (1980).

Swayze, D. (2010).

The federal juvenile justice and delinquency prevention act vs. Minnesota statutes and rules of juvenile procedure.

St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Department of Public Safety, Office of Justice Programs.

Swayze, D. & Buskovick, D. (2012a).

Minnesota juvenile diversion: A summary of statewide practices and programming

. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Department of Public Safety, Office of Justice Programs.

Swayze, D., & Buskovick, D. (2012b).

Minnesota youth intervention programs: A statistical analysis of participant pre- and post-program surveys

. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Department of Public Safety, Office of Justice Programs.

Swayze, D., & Buskovick, D. (2012c).

On the level: Disproportionate minority contact in Minnesota's juvenile justice system

. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Department of Public Safety, Office of Justice Programs.

Swayze, D., & Buskovick, D. (2012d)

Youth in Minnesota correctional facilities and the effects of trauma: Responses to the 2010 Minnesota student survey.

St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Department of Public Safety, Office of Justice Programs.

Swayze, D., & Buskovick, D. (2013).

Back to the future: Thirty years of juvenile justice data in Minnesota, 1980–2010

. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Department of Public Safety, Office of Justice Programs.

Swayze, D., & Buskovick, D. (2014a).

Back to the future: Thirty years of Minnesota juvenile justice policy and practice, 1980–2010

. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Department of Public Safety Office of Justice Programs.

Swayze, D. & Buskovick, D. (2014b).

Law enforcement in Minnesota schools: A statewide survey of school resource officers.

St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Statistical Analysis Center.

Sweeten, G., Piquero, A., & Steinberg, L. (2013). Age and the explanation of crime, revisited.

Journal of Youth and Adolescents

, 42, 921–938.

Theriot, M. (2009). School resource officers and the criminalization of student behavior.

Journal of Criminal Justice

, 37, 280–287.

Wilson, J. Q. (1980). What works revisited: New findings on criminal rehabilitation.

The Public Interest

, 61, 3–17.