7

Education

IN 1983, a “National Commission on Excellence in Education,” appointed by the secretary of the Department of Education, released its final report with the foreboding title A Nation at Risk. The report told us that American education had been going downhill for nearly twenty years and had arrived at a terrible state. “We have, in effect,” wrote the Commission, “been committing an act of unthinking, unilateral educational disarmament.,”1

A Nation at Risk put the imprimatur of official Washington on a conclusion that nearly everyone was prepared to accept anyway. But the story of what happened, and when, is more interesting than a tale of unbroken disaster. The schools deteriorated after 1964, yes; but what is less publicized is that there were signs in the 1950s and early 1960s that the schools were doing quite well in many respects and were improving. Nor were the improvements for only a favored few. On the contrary, the data suggest that education was improving for the poor and the disadvantaged as well as for the affluent.

The Federal Dollars

As in the case of the jobs programs, the federal investment during the reform period and after was huge. Between 1965 and 1980, more than $60 billion (1980 dollars as always) was earmarked for the improvement of elementary and secondary education of the disadvantaged, and more than $25 billion was spent on grants and loans to students engaged in post-secondary education.2 And as in the case of the jobs programs, very little had been spent for these purposes by the federal government prior to 1965. What was the return on the investment? We will inquire into the education of the poor and disadvantaged, using black children as the basis for our assessment. We will examine first the quantity of education they received, then consider the quality of that education.

Quantity I: Enrollment in High School

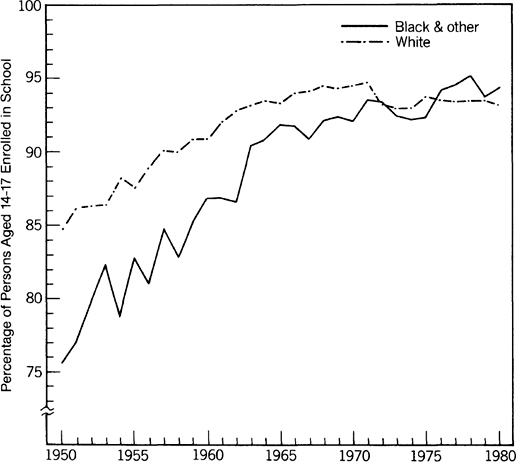

In 1950, nearly one out of four black youths of high school age was not officially enrolled in school. By 1980, only one out of eighteen was not officially enrolled in school.3 By any standard, the progress was enormous. Virtually all of it occurred before the reform period. Figure 7.1 shows the pertinent trendline:

School Enrollment of Persons 14–17 Years Old by Race, 1950,–1980

Data and Source Information: Appendix table 12.

From 1950 to 1963, the black enrollment percentage increased from 76 percent to over 90 percent. By 1965,92 percent of minority children of high school age were enrolled in school, compared with about 93 percent of white children. Essential parity had been achieved. In subsequent years, enrollment rates rose more slowly—a natural result of nearing the saturation point—and stood in 1980 at 94 percent for blacks and 93 percent for whites. For both whites and blacks, enrollment was effectively universal.

In one respect the gains made by black children are not adequately reflected in these data. Prior to the 1950s, black children in segregated systems (segregation was compulsory in seventeen states and permitted in four others when the Brown decision was handed down) not only had inferior facilities but often had a shorter school year than did white students. Even before the Brown decision took effect (which did not happen widely until the late 1960s and early 1970s), the 1950s saw major improvements in such dimensions. By 1954, the length of the school year in black southern schools had come within two days of the national average, and average days attended per pupil had closed to a nine-day difference from a twenty-six-day difference in 1940 and a forty-six day difference in 1930.4

In another sense, the quantity of education has probably been diminishing for blacks of high school age. Reported enrollment figures in inner-city schools exaggerate actual enrollees, and reported days of attendance exaggerate actual hours of class time. Based on a reconstruction of real versus reported attendance at five inner-city high schools in New York City, Atlanta, and Indianapolis, the statistics grossly underestimate actual classes missed. Underestimates of dropout rates are also very high.5

Two reasons account for the discrepancy in the school systems from which I have data. One is a policy of “enrolled until proved otherwise.” In some school systems, unless a student formally declares to the school that he or she has dropped out, the student is carried on the rolls to the end of the current year—in some cases (although not by official policy), indefinitely. These practices are not necessarily a product of loose standards. State and federal aid is typically linked to the number of students enrolled. School systems strapped for resources have a clear and present incentive to show as many students on the books as possible.

The second reason relates to overload. In a school where 99 percent of the students are in class, the 1 percent roaming the halls is conspicuous and easily dealt with. When large numbers of students are in the halls and the stairwells, congregated in groups, they are not easily dealt with. Thus it happens that students in some schools could with impunity use the school as a sort of social center, going to home room in the morning and cutting most or all of the rest of their classes. The student is nonetheless shown on the books as having attended school that day and counted in the computation of attendance figures.

I am not aware of data that permit generalizations about the magnitude of the problem or the relative problem in inner-city and suburban schools even for a single year, let alone for a time series stretching back to the 1960s and 1950s. But a significant problem is generally if unsystematically conceded to exist and, completely apart from the issue of quality of education, must lead us to wonder what an accurate plot of “hours spent in class” would look like for black students from 1950 to 1980.

Quantity II: College and Beyond

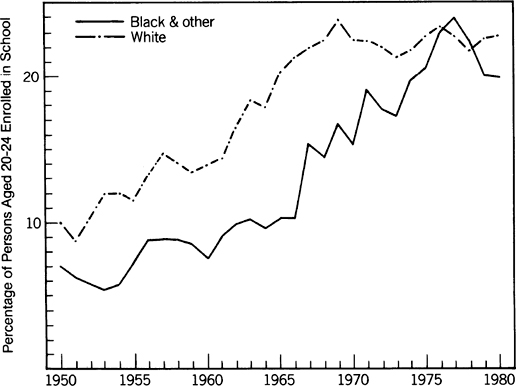

The 1960s saw an unprecedented increase in college attendance by black students. In 1960, only 7 percent of blacks aged 20,–24 were enrolled in college; in 1970, this figure had more than doubled, to 16 percent. The period of most rapid increase came with the onset of the federal programs to provide financial assistance. Figure 7.2 shows the enrollment figures for persons aged 20–24. In 1967, the first school year in which significant funding from the education acts of 1965 became available, black enrollment jumped by half, from 10 to 15 percent of that age group. Progress continued through 1977, as black enrollment in colleges continued to increase during a period when white enrollment was dropping slightly. In 1977, blacks caught up—24 percent of blacks aged 20-24 were enrolled in school, compared with 23 percent of whites in the same age group. Only eleven years earlier, the proportions of whites enrolled was twice that of blacks. After 1977, the proportion of black students 20–24 years of age enrolled in school fell each year through 1980, despite continuing increases in loans and grants during those years.

School Enrollment of Persons 20–24 Years Old by Race, 1950–1980

Data and Source Information: Appendix table 12.

Quality: What Has Been Learned?

We have no single measure for documenting the quality of education. There is no equivalent to the unemployment rate for assessing educational achievement. Until 1983, the deterioration of American public education had been documented mostly through horror stories in newspaper feature articles about rampant illiteracy among high school graduates and about chaotic high schools in the inner city where the teachers worked in fear of their students. In 1981, the Department of Education, concerned by what it called “the widespread public perception that something is seriously remiss in our educational system,” appointed the national commission. Over a period of eighteen months, the commission ordered special papers; heard voluminous testimony from educators, parents, scholars, and public officials; and reanalyzed the existing data bases. In the end, their much-publicized report documented most of the horror stories. The commission found them to be true, to a greater extent and in more dismaying dimensions than most had imagined. A few examples:

- Nearly 40 percent of 17-year-olds could not draw inferences from written materials; two-thirds could not solve a mathematics problem requiring a sequence of steps.6

- “Secondary school curricula have been homogenized, diluted, and diffused to the point that they no longer have a central purpose,” Whereas in 1964 only 12 percent of high school students were on a “general” track (neither vocational nor preparatory to college), by 1979 that proportion had grown to 42 percent.

- By 1980, remedial mathematics courses constituted a quarter of all mathematics courses taught in public universities.

- Traditional performance standards had become meaningless; as homework decreased and real student achievement declined, grades rose.

- “Minimum competency” examinations were tending to lower educational standards for all.

The commission used a quote from Paul Copperman to summarize the state of decay it had found:

Each generation of Americans has outstripped its parents in education, in literacy, in economic attainment. For the first time in the history of our country, the educational skills of one generation will not surpass, will not equal, not even approach, those of their parents.7

Only scattered, limited criticisms of the report were voiced, despite the harsh language that the commission used. Few were prepared to defend the state of American education.

But when did all this happen? Whose education was most harmed? Was anyone’s helped? The commission focused on the 1970s; we want to know about the 1950s and 1960s as well. The commission generalized about American education as a whole; we want to track the quality of education provided to the poor and disadvantaged.

Events have conspired to make this task extremely difficult. Educational measures are the ones on which we have the most trouble documenting precisely how the children of the poor, and especially poor black students, have fared. The lacuna is no accident. Until the mid-1960s, breakdowns of standardized test scores and other achievement measures by race were meager because educational policy frowned upon—often forbade—racial identification on test sheets or transcripts. It was one of the ways in which institutions in the 1950s were inching toward the ideal of a color-blind society. After the mid-1960s, the situation was reversed. The student’s race became a crucial piece of information to be used on behalf of minority students in such things as admissions. But data about black test scores remained sparse because of fears that too much would be made of poor scores.

Drawing from the scattered data that do exist, I will venture two conclusions: (1) Education for the disadvantaged was probably improving, perhaps dramatically, during the 1950s and early 1960s; and (2) the federal investment of $60 billion in elementary and secondary education for the disadvantaged bought nothing discernible. After the mid 1960s, public education for the disadvantaged suffered as much as, and probably even more than, education for youth in general.

Looking Up: Progress Until the Mid-1960s

In the discussion of jobs and earnings, I pointed to the dramatic increase in black “returns to education” during the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. To recapitulate, an extra year of education in the 1940s and earlier brought a much smaller proportional increase in income for a black than it did for a white. As time went on, this gap narrowed. Then blacks gained ground rapidly in the late 1940s and 1950s and reached a crossover point sometime between 1959 and 1962. By 1963–65, the proportional increase in wages per extra year of schooling was 58 percent larger for blacks than for whites —a remarkable turnaround. But what caused it? The answer could not be national policy: The large increases in returns to education occurred before any of the significant civil rights legislation or court decisions had affected school practices.

Finis Welch, who first identified the change in black returns to education, advanced the hypothesis that schooling had improved for blacks. First, he pointed to the black-white differences in statistics on schools. “There,” he writes, “the data are clear: Through time the relative quality of black schooling has risen rapidly.”8 By the time of the Brown decision, disparities in black and white enrollment, attendance, and expenditures had fallen dramatically from those of the 1920s and 1930s. Acknowledging that some of the increased returns to education might be traced to a downward drift in market discrimination, Welch pointed out that such explanations had great difficulty in explaining the data:

In behalf of the quality of schooling hypothesis let me summarize the trends revealed here with which [alternative hypotheses] must contend. First, not only have relative black incomes increased but the gain has been greatest for higher school completion levels. Second, the phenomenon of rising returns to schooling is not only true in comparing black relative to white incomes but holds within the races as well: Young blacks fare better in comparison to young whites than do older blacks in comparison to older whites and schooling contains more of an income boost for young blacks and young whites than for older generations of their own races [emphasis in the original].9

Simple reductions in racial discrimination would not produce these results. Improving education would.

These are some of the indirect reasons for thinking that education for blacks was improving meaningfully during the 1950s. When we turn to the fragmentary test data that are available, we find some confirmation. New York City reading score data compiled by Welch are strikingly consistent with his argument. These were the “grade equivalent” scores from schools with at least 90 percent black enrollment:

| Grade Equivalent Scores for | ||

| Year | Third Graders | Sixth Graders |

| 1957 | 2.67 | 4.88 |

| 1960 | 2.87 | 5.22 |

| 1965 | 3.19 | 5.67 |

Put roughly, whereas the average sixth-grader in 1957 was functioning at a level more than one year behind the norm, a sixth-grader in 1965 was only a few months behind. Third-graders caught up completely. According to these data, black education was improving significantly through 1965.10

We find further support from the results of tests administered to two large, nationally representative samples of students in 1960 and 1965. In 1960, the American Institutes for Research, under the sponsorship of the U.S. Office of Education, began an unprecedented attempt to capture a slice of the American population for lifelong study. It was called “Project TALENT,” and it assembled extensive academic and personal data on all students in a nationally representative stratified sample of 987 high schools. As part of the Project TALENT instruments, a battery of seven cognitive tests was administered to each student, and a weighted composite called “General Academic Aptitude” was computed.11 These were the mean scores for ninth graders in 1960:

| Males | Females | Total | |

| White | 444 | 469 | 456 |

| Black | 300 | 319 | 309 |

The black mean score in 1960 was approximately a third lower than the white score.

In the fall of 1965, we have another fix on the racial difference from a national, stratified sample plan covering 900,000 pupils in the first and twelfth grades. The study, commissioned by the Office of Education, became known as the “Coleman Report.”12 The battery consisted of five tests (nonverbal, verbal, reading, mathematics, and general information). The results were:

| Test | White | Black |

| Nonverbal | 52.0 | 40.9 |

| Verbal | 52.1 | 40.9 |

| Reading | 51.9 | 42.2 |

| Mathematics | 51.8 | 41.8 |

| General Information | 52.2 | 40.6 |

| Average of the Five Tests | 52.0 | 41.1 |

The results still showed a major black-white difference, and the study as a whole was used as evidence for the need for massive federal assistance to help black students catch up. But insofar as we can determine from a comparison with the 1960 test, black students were already in the process of catching up. The intuitive way to see this is by putting the black-white scores in terms of proportions—in 1960, the black score was only 68 percent of the white score; in 1965, the black score was a noticeably higher 79 percent of the white score. For a variety of reasons, comparisons of proportions can be meaningless across different tests. But in this case, the intuitive sense that the 1965 black-white gap was smaller than the 1960 gap is corroborated by a comparison of standard deviations, the technical basis for comparing inter-group differences across tests.13 The black-white difference on the 1960 test was equal to 1.28 standard deviations; in the 1965 test, the difference had narrowed to 1.09 standard deviations.

Comparing results on different test batteries is always tricky. But the general aptitude batteries in the Project TALENT and Coleman studies were testing for similar qualities and used very large and representative samples; there is reason to pay some attention to the narrower difference in the 1965 results. Added to the other bits of evidence, and given no countervailing data that black education was getting worse during the pre-1965 period, the evidence available to us points to the conclusion that public elementary and secondary education for blacks was getting better —in terms of test scores, and in terms of the economic benefits that better education seems to have been yielding.

The State of Black Education by 1980

The rest of the story is grim, so grim that it is reasonable to question whether the data I am about to present can be taken at face value. For that reason, an extended discussion of the “cultural bias” issue and test scores is presented in the notes.14 Put briefly, as of 1980 the gap in educational achievement between black and white students leaving high school was so great that it threatened to defeat any other attempts to narrow the economic differences separating blacks from whites. We will consider first the overall profile of youth, then concentrate on those who are college-bound.

Educational Achievement: The Average High School Graduate

Since the Second World War, the Department of Defense has administered a basic test of vocational aptitude to its recruits and draftees. The results of these tests could not be used to interpret trends in the population at large, because the nature of the population of recruits entering the armed forces varies so widely over time. In 1980, the Department of Defense decided to investigate how the scores of its recruits compared with the general population of youth. It therefore coordinated the administration of its Armed Service Vocational Aptitude Battery with the National Longitudinal Survey (NLS) of Youth Labor Force Behavior to provide a nationally representative, large-sample assessment of persons aged 18–23.

The results for the basic test of verbal and numeric skills (the Armed Forces Qualification Test, or AFQT) were as follows:

| Males | Females | Total | |

| White | 56.6 | 55.3 | 56.0 |

| Black | 23.9 | 24.7 | 24.3 |

Overall, the white mean score was 2.3 times the black mean score. The ratio was roughly the same for all age categories within the 18–23 year-old population.15 More detailed breakdowns by educational level and other variables are shown in table 15 of the appendix.

It is difficult to specify exactly what such a difference means, except that it is obviously extremely large. A better idea of the substantive meaning of the difference is conveyed by the results of a test of reading skills included in the survey: The average white was reading at nearly a tenth-grade level (9.9), while the average black tested was reading at a seventh grade level (7.0).16 But a still clearer sense of the seriousness of the gap may be seen from a test with which most readers have personal experience: the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT).

Educational Achievement: The College-Bound

The College Board, which administers the SAT, did not begin to collect background information on its testing population until 1971–72, and not until 1981 did the College Board finally decide to make public the racial breakdown of scores. It took until then for the Board to resolve a controversy between, as the Board put it, “those who fear that publication of these data will serve to convey a misperception of minority students’ ability, and those who believe that exposure of the data to public scrutiny will better serve minority interests by demonstrating the need for (and thus lead to) more affirmative action with respect to access to higher education.”17

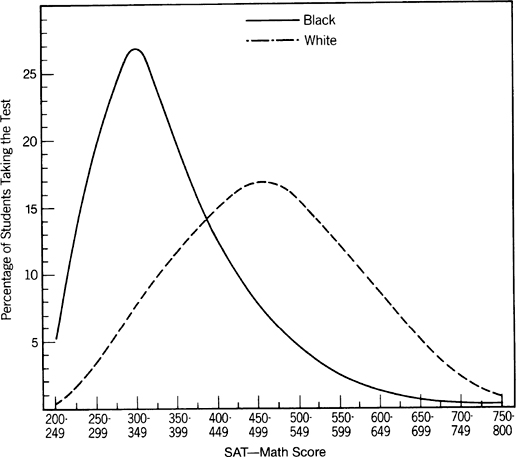

As of 1980, the mean SAT score of blacks was 330 for the verbal test and 360 for the math test, more than 100 points lower in each test than the mean for whites. The gap was concentrated in the extremely poor scores. The lower bound for the SATs is 200. Whereas only 3.5 percent of white test-takers scored less than 300, fully a quarter—25.0 percent— of black test-takers scored in that category. The extent of the difference is shown graphically in figure 7.3, using the scores from the mathematics component of the SAT.

There are no hard-and-fast rules about the college performance of people who score at various levels on the SAT. Hard work, motivation, and a variety of other factors are all important. Nonetheless, an SAT score in the region of 400 or less indicates a deficiency of skills that makes it extremely difficult for a student to cope with a demanding college curriculum. Applying the rule, rough as it is, to the distribution of scores on the SAT tests, the implication for classroom performance of a cross-section of black test-takers is that a large majority would fail a true college-level course: 71 percent of black students taking the SAT in 1980 scored less than 400 in the mathematics component of the SAT, and 77 percent scored less than 400 in the verbal component.18

When this state of affairs is combined with pressure (indeed, legal demands) not to show racial patterns in grading and placement in honors courses, at least one reason for the widely publicized deterioration in educational standards is obvious. The only way to avoid racial patterns in grading or placement in honors courses, or any other decisions based on achievement measures, is to employ a double standard of some sort if in fact one racial group has a markedly different pattern of achievement.19

FIGURE 7.3.

Distribution of SAT-Math Scores by Race, 1980

Data and Source Information: Appendix table 16.

In drawing an overall assessment from these data, the echoes of the results on wages and occupations and the “pulling away” process are unmistakable. At the top of the ladder, there was surely progress. The mere fact that so many more blacks were going to college in the 1970s than in the 1950s and early 1960s suggests that improvement occurred. (Even if college education has been getting worse and preparation has been inadequate, we will assume that a bad college education is better than none at all.) We cannot make the same statement about the large majority of black students who do not get that far. At the high-school level, the basic job of keeping kids in school had already come within a fraction of saturation by 1965. The large historical gap in school enrollment between blacks and whites had been closed to within 2 percentage points. While the quality of secondary education was sliding downhill, it could not cling to the excuse that at least it was providing some education to disadvantaged students who previously had gotten none. It was providing worse education, period. Everything we know about inner-city schools suggests that the deterioration in these schools, which served the most disadvantaged of all students, was greater than anywhere else.

Summary of the Federal Effort

IN THE BEGINNING of the period 1950–80, there was no federal effort to speak of. The reasons for federal standoffishness were “race, religion, and fear of federal control,” as Diane Ravitch has put it. Northerners were unwilling to fund segregated southern schools, and southerners would not vote for a bill that excluded them. An analogous standoff prevented funding that would include or exclude non-public (largely Catholic) schools. And everyone was determined that the federal government not intrude into decisions about local education—in America, one of the most fiercely protected preserves of local government.

The harbinger of the expanded role was Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which struck down the “separate but equal” doctrine. But for several years its importance was more symbolic than real. Brown I (the actual decision) spoke eloquently against segregated schools as a violation of constitutional protections. Brown II (the guidelines for implementing Brown I, issued a year later) left the working-out of desegregation in the hands of local authorities. The result was that, despite a few dramatic pitched battles—the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock, George Wallace and his stand in the schoolhouse door, the admission of James Meredith to the University of Mississippi—relatively little changed in southern school attendance patterns until late in the 1960s. It was not until 1968, in Green v. County School Board, that the Court said that “freedom of choice” solutions were inadequate unless they actually resulted in mixed classrooms, and that desegregation must be ended “root and branch” by whatever means worked. See Frank T. Read, “Judicial Evolution of the Law of School Integration Since Brown v. Board of Education,” Law and Contemporary Problems 39 (Winter 1975), pp. 7–49. Meanwhile, in the North, de jure segregation was not the problem.

When the federal government finally did become involved in financing education, it was out of fear for the nation’s standing vis-à-vis the Soviet Union. The shock of Sputnik in the fall of 1957 jarred loose the first major federal funding of public education so that we might catch up with the Russians. The name of the legislation, “The National Defense Education Act of 1958” (NDEA), reflected its narrowly construed justification. The Congress continued to thwart efforts to pass more general bills to assist the schools.

The huge legislative majority that President Johnson brought away from the 1964 election—68 to 32 in the Senate, 295 to 140 in the House—overwhelmed the special interests that had stymied past efforts to involve the federal government in education. As in so many other initiatives, poverty provided a new rationale: in this instance, for sidestepping the public school-private school controversy. The basis for aid would be the poverty of the students. Whether they attended private or public schools, they would be eligible to receive the services dispensed by public agencies. The result was the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965.

Even as that bill passed, however, other considerations were leading to an expansion of federal involvement in the schools and its hopes for them:

- The federal government wanted to eliminate racial segregation of the schools—not only the de jure segregation struck down in the Brown decision, but the de facto segregation that was nearly universal in urban America

- It wanted to provide compensatory education for students who were at a special disadvantage—physically, mentally, economically, or sociologically

- It wanted to protect students’ rights

- It wanted to keep all students in school through the twelfth grade

- It wanted to remove race bias, sex bias, and a variety of other biases from the curriculum and from the pedagogy of the nation’s schools

- It wanted different, better methods of teaching those who were not doing well under traditional methods—with several schools of thought contending about how this might be done

- It wanted to provide bilingual education for students, mainly Hispanic, whose first language was not English

Some of these goals came attached to legislation, some to Supreme Court decisions, some to policies promulgated by the Office of Education (later the Department of Education). To further complicate matters, each of these goals had its own constituency in the public at large and within the educational establishment in particular. Moreover, the transformation of the federal role in education during the period we are examining—and transformation is not an extravagant word for it—was an overlay on an existing system, and the interaction between what the government found itself doing, what educators were intending to do on their own, and what was going on in society outside the school is exceedingly complex. In the subsequent interpretation (chapter 13) of what went wrong, I shall pick out certain elements that seem to me to stand out as especially important —namely, those that affected the ability of a teacher to engage in the act of teaching. But for the moment let us consider the dollars. At least, our educational deficiencies in the period since 1965 cannot be blamed on federal neglect.

Title I of ESEA opened the door to direct federal support of elementary and secondary education, allocating funds to the states according to the number of children from families that fell below specified income levels. The purpose of the funds was “compensatory education” for low-income students. Even from the beginning, funding was high. ESEA and the other programs for disadvantaged students are an important exception to the generalization that the Great Society programs were not implemented in a big way until after the reform period. Funding for disadvantaged elementary and secondary students went from nowhere in 1964 to over $3 billion (in 1980 dollars) by 1966. By 1968, funding had reached the real spending level it would maintain through the first half of the 1970s. See W. Vance Grant and Leo J. Eiden, Digest of Educational Statistics 1981 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1982), table 161. This source, prepared by the National Center for Educational Statistics, is hereafter designated DES-81.

In higher education, the first problem facing disadvantaged students was getting the money to go to school. To that end, the NDEA loan program begun in 1958 was augmented by the Higher Education Act of 1965, which for the first time provided federal scholarships (not just loans) for undergraduates. Total funding of grants and loans combined ran just under a billion dollars (1980 dollars) through 1970, and slightly more than a billion through 1973. Then the budgets took off, doubling in another two years and reaching more than $4 billion annually by 1980. (The figures for student loans include both NDEA and insured loans. The figures for grants are predominantly Basic and Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grants, plus a scattering of other programs (DES-81, table 163, note 6).

To get a sense of how large the effort became, consider that grants and loans totalling $4.4 billion—the figure for 1980—are equivalent to a million annual awards of $4,400 in support. Even in 1972, when the size of the grant and loan programs was comparatively small, 32 percent of all college freshmen were receiving federal assistance. Among freshmen in the lowest socioeconomic quartile, 47 percent were receiving federal assistance. Fifty-three percent of all black students were receiving federal support in a year when the size of the program, in constant dollars, was only a fifth of the size it would reach by 1980 (DES-81, table 135).

Diane Ravitch’s The Troubled Crusade: American Education 1945–1980 (New York: Basic Books, 1983) is the best single account of the course of American education during the period we are examining. For a review of the provisions of federal education programs, see Ravitch, Troubled Crusade, and Henry M. Levin, “A Decade of Policy Developments in Improving Education and Training for Low-Income Populations,” in Robert H. Haveman, ed., A Decade of Federal Antipoverty Programs: Achievements, Failures, and Lessons (New York: Academic Press, 1977), 123–96.