13

Incentives to Fail II: Crime and Education

I OPENED the discussion of incentives with choices affecting work, marriage, and raising a family because the changes of the 1960s were so concrete in these areas and because the presumptive role of economics is so great. Throughout history and among people in every social and economic stratum, choices of when and whether to seek work, when to marry, when and how often to have children, have been intimately bound up with economic considerations. It was not until recently (in historical perspective) that other considerations were nearly as important.

But comparable changes in incentives surrounded other behaviors as well. The most important of these had to do with getting an education and resisting the lure of crime. The rules did not change in the specific, discrete ways that the rules of welfare and employment changed. Nonetheless, incentives changed. My proposition is that the environment in which a young poor person grew up changed in several mutually consistent and interacting ways during the 1960s. The changes in welfare and changes in the risks attached to crime and changes in the educational environment reinforced each other. Together, they radically altered the incentive structure. I characterize these changes, taken together, as encouraging short cuts in some instances (get rich quick or not at all) and “no cuts” in others— meaning that the link between present behavior and future outcomes was obscured altogether.

Crime

Let us assume an economic view of crime: Crime occurs when the prospective benefits sufficiently outweigh the prospective costs. When the risks associated with committing a crime go down, we expect crime to increase, other things being equal. Now, consider two elements of the “risk” equation as they changed from the perspective of the potential offender during the 1960s: the risk of being caught and the risk of going to prison if caught.

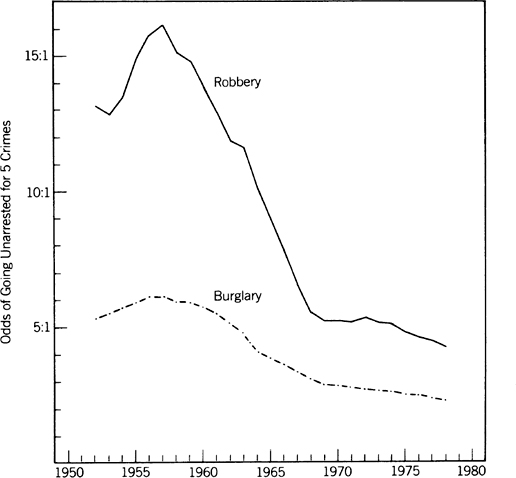

Figure 13.1 uses UCR data to plot the odds of getting away with (not being arrested for) five robberies or burglaries as they changed during the period from 1954 to 1980.1 The decline, which was concentrated during the 1960s, was substantial for burglary, precipitous for robberies.

The Declining Risk of Apprehension, 1954–1980

Data and source information: Appendix table 18.

Note: Five-year moving average was computed from clearance data in appendix table 18. Note that estimate is based on reported crimes. Risk of apprehension is overestimated by exclusion of unreported crimes.

The question of causation does not arise. It makes no difference for our purposes whether the increasing number of crimes overburdened the police, causing the reduction in clearance rates, or whether the declining risk of apprehension encouraged more crime. I simply observe that a thoughtful person watching the world around him during the 1960s was accurately perceiving a considerably reduced risk of getting caught. A youth hanging out on a tough urban street corner in 1960 was unlikely to know many (if any) people who could credibly claim to have gotten away with a string of robberies; in 1970, a youth hanging out on the same street corner might easily know several. When he considered his own chances, it would be only human nature for him to identify with the “successes.”

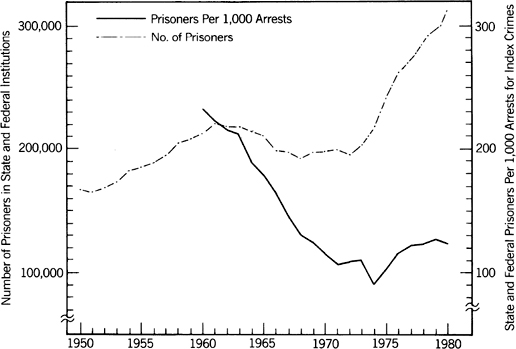

The data on risk of imprisonment tell much the same story, as figure 13.2 shows:

FIGURE 13.2. Decline in Risk of Imprisonment if Caught, 1950–1980

Data and Source Information: Appendix table 23.

Note: Local jails are not included. Plot represents a trend over time, not the specific probability of being incarcerated as a result of an arrest.

In this case, causes and effects are not quite so entangled. It was not just that we had more people to put in jails than we had jails to hold them (the overburdening problem); we also deliberately stopped putting people in jail as often. From 1961 through 1969, the number of prisoners in federal and state facilities—the absolute number, not just a proportion of arrestees —dropped every year, despite a doubling of crime during the same period.2

The two types of risk are not confounded. The “risk of arrest” and “risk of punishment” each dropped independently. Combined, the change in incentives was considerable.

Accompanying these changes in the numbers were changes in the rules of the game that once again disproportionately affected the poor. The affluent person caught by the police faced effectively the same situation in 1960 and in 1970. The poor person did not. In 1960, he could be picked up more or less on the police officer’s intuition. He was likely to be taken into an interrogation room and questioned without benefit of counsel. He was likely to confess in instances when, if a lawyer had been sitting at his side, he would not have confessed. He was likely to be held in jail until his court date or to have to post bail, a considerable economic punishment in itself. If convicted, he was likely to be given a prison term. By 1970, the poor person had acquired an array of protections and strategems that were formerly denied him—in effect, the same protections and strategems that the rich had always possessed.

These changes extended the practice of equal treatment under the law (good). They also made crime less risky for poor people who were inclined to commit crimes if they thought they could get away with them (bad). One may recognize the latter without opposing the former.

For juveniles, the changes in incentives were especially dramatic. They were concentrated not in the smaller towns and cities, where juveniles generally continued to be treated as before, but in the large cities, where an upsurge in juvenile crime coincided with a movement toward a less punitive approach to delinquents. Consider the punishment of juveniles in Cook County, which includes the city of Chicago. In 1966, when the juvenile crime rate was entering its highest rate of increase, approximately 1,200 juveniles from Cook County were committed to the Illinois state system of training schools. For the next ten years, while the rate of juvenile crime in Cook County increased, the number of commitments dropped steadily. In 1976, fewer than 400 youths were committed—a reduction of two-thirds at a time when arrests were soaring.3 A single statistic conveys how far the risk of penalty had dropped: By the mid-1970s, the average number of arrests of a Cook County youth before he was committed to a reform school for the first time was 13.6.4 In such cities—and as far as we know, Chicago is typical—the risk of significant punishment for first arrests fell close to zero.5 In discussions of why some juveniles become chronic delinquents, it should first of all be noted that, during the 1970s, a youngster who found criminal acts fun or rewarding and had been arrested only once or twice could have chosen to continue committing crimes through the simplest of logics: There was no reason not to.

The reduction in present punishment was accompanied by what may have been the single most significant change (well known to juveniles) in the rules of the game: In many states, including most of the northern urban states, laws were passed that provided for sealing the juvenile court record, tightening existing restrictions to the juvenile record, or, in sixteen states by 1974, purging or “expunging” it—destroying the physical evidence that the youth had ever been in trouble with the courts. The purpose of such acts was to ensure that, no matter what a vindictive prosecutor or judge might want to do, a youth who acquired a record as a juvenile could grow up without the opprobrium of a police record following him through life.

The increased inaccessibility of the juvenile record did little to change the incentives for the minor delinquent who had been arrested a few times for youthful transgressions. Such a record was not going to prevent him from getting many jobs nor would it make much difference if he were arrested as an adult. But the increased restrictions on accessibility had quite important implications for the delinquent with a long record of major offenses. By promising to make the record secret or, even more dramatically, by actually destroying the physical record, the juvenile justice system led the youth to believe that no matter what he did as a juvenile, or how often, it would be as if it had never happened once he reached his eighteenth birthday. Tight restrictions on access to the juvenile arrest and court records radically limited liability for exactly that behavior—chronic, violent delinquency—that the population at large was bemoaning. A teenager engaged in such behavior (or contemplating doing so) could quite reasonably ignore his parents’ lectures about the costs of getting a police record. His parents were in fact wrong.

There is growing empirical evidence that raising the costs of criminal behavior—deterrence—reduces its frequency; it is summarized in the notes.6 But to some extent the evidence, hard-won against technical problems and ideological resistance, is superfluous. James Q. Wilson has made the point very well:

People are governed in their daily lives by rewards and penalties of every sort. We shop for bargain prices, praise our children for good behavior and scold them for bad, expect lower interest rates to stimulate home building and fear that higher ones will depress it, and conduct ourselves in public in ways that lead our friends and neighbors to form good opinions of us. To assert that “deterrence doesn’t work” is tantamount to either denying the plainest facts of everyday life or claiming that would-be criminals are utterly different from the rest of us.7

For years, the latter assumption has been buried within other explanations—"Crime is a response to exploitation and poverty, therefore deterrence will not work” (a non sequitur), or, “People are not thinking that far ahead when they commit crimes, therefore deterrence will not work,” and so on. If such explanations are to be truly plausible (that is, believable even to the people who assert them), the inescapable but unspoken conclusion has been, as Wilson suggests, that such persons are utterly different from the rest of us. The assumption is unwarranted, unnecessary, and objectionable.

Education

The basic problem in education has not changed. Persuading youngsters to work hard against the promise of intangible and long-deferred rewards was as tough in 1960 as in 1970. The challenge of creating adequate incentives was no different. But as in the case of crime, the disincentives for a certain type of student changed.

We are not considering children whose parents check their homework every night, or children who from earliest childhood expect to go to college, or children with high IQs and a creative flair. Rather, we are considering children with average or below-average abilities, with parents who ignore their progress or lack of it, with parents who are themselves incompetent to help with homework. We are not considering the small-town school with a few students, but the large urban school. Such children and such schools existed in 1960 as in 1970. Yet among those who stayed in school, more students seemed to learn to read and write and calculate in 1960 than in 1970. How might we employ an incentives approach to account for this?

While learning is hard work, it should be exciting and fun as well. But most large urban schools, though they may try to achieve that ideal, have other concerns that must take priority. They must first of all maintain order in the classroom and secondly make students try to do the work even if they do not want to. With students who come from supportive home environments, these tasks are relatively easy for the school; a bad grade or a comment on a report card is likely to trigger the needed corrective action. But with students who have no backup at home, these tasks are always difficult. Sanctions are required. In 1960, such sanctions consisted of holding a student back, in-school disciplinary measures, suspension, and expulsion. By the 1970s, use of all these sanctions had been sharply circumscribed.

During the same period, the incidence of student disorders went from nowhere to a national problem. Robert Rubel, who has compiled the most extensive data on this topic, divides the history of school disorders into three periods. From 1950 to 1964, disorders were of such low levels of frequency and seriousness that they were hardly worth mentioning. From 1964 to about 1971, disorders exploded, especially those that Rubel calls “teacher-testing.” After 1971, the disorders were less patterned, but they continued to exist at the high levels they had reached during the late 1960s.8 Why should disorders have increased at that time? Rubel points to the generally chaotic nature of the times. Another answer is that we began to permit them.

In part, the intellectual climate altered behavior. Books such as Death at an Early Age led the way for educational reforms that de-emphasized the traditional classroom norms in favor of a more open, less disciplined (or less repressive and ethnocentric, depending on one’s ideology) treatment of the learning process.9 The black pride movement added voices claiming that traditional education was one more example of white middle-class values arbitrarily forced on blacks.10 But there were more concrete reasons for students and teachers alike to change their behavior.

In part, the federal offices that dispensed government help had a hand. They could establish projects implementing preferred strategies, which in the 1960s invariably favored a less traditional, less white-middle-class attitude toward education. They could support efforts to limit the use of suspension and expulsion. They could make imaginative use of the provisions of Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act (enabling them to withdraw federal funds if a school system was found to be discriminating on grounds of race) to bring reluctant school systems around to their point of view.

In part, the judiciary had a hand. The key event was the Supreme Court’s Gault v. Arizona decision in 1967. The case involved a juvenile court, but the principle enunciated by the Court applied to the schools as well, as the American Civil Liberties Union was quick to point out to school systems nationwide.11 Due process was required for suspension, and the circumstances under which students could be suspended or otherwise disciplined were restricted. Teachers and administrators became vulnerable to lawsuits or professional setbacks for using the discretion that had been taken for granted in I960.12 Urban schools gave up the practice of making a student repeat a grade. “Social promotions” were given regardless of academic progress.

For all these reasons and many more, a student who did not want to learn was much freer not to learn in 1970 than in 1960, and freer to disrupt the learning process for others. Facing no credible sanctions for not learning and possessing no tangible incentives to learn, large numbers of students did things they considered more fun and did not learn. What could have been more natural?

A concomitant to these changes in incentives was that teachers had new reasons not to demand high performance (or any performance at all). In the typical inner-city school, a demanding teaching style would be sure to displease some of the students—as indeed demanding teachers have done everywhere, from time immemorial. But now there was this difference: The rebellious students could make life considerably more miserable for the teacher than the teacher could for the students—through their disruptive behavior in class, through physical threats, or even through official channels, complaining to the administration that the teacher was unreasonable, harsh, or otherwise failing to observe their rights. In the 1960s and into the 1970s, teachers who demanded performance in an inner-city school were asking for trouble.

The dramatic problems of confrontation were combined with the less dramatic ones of absenteeism, tardiness, and failure to do homework. Jackson Toby describes the results:

When only a handful of students attempt to complete homework, teachers stop assigning it; and of course, it is difficult to teach a lesson that depends on material taught yesterday or last week when only a few students can be counted on to be regularly in class. Eventually, in these circumstances, teachers stop putting forth the considerable effort required to educate.13

Toby traces the rest of the chain: Teachers take the maximum number of days off to which they are entitled. Substitute teachers are hard to recruit for the same reasons that the teachers are taking days off. The best students, both black and white, transfer to private or parochial schools, making it that much more difficult to control the remainder. Absent teachers and loss of control lead to more class-cutting. More class-cutting increases the noise in the halls. “In the classrooms, teachers struggle for the attention of the students. Students talk to one another; they engage in playful and not-so-playful fights; they leave repeatedly to visit the toilet or to get drinks of water.”14 Learning does not, cannot, occur.

School administrators in the last half of the 1960s had to finesse the problem of the gap between white and black achievement (see chapter 7). Pushing hard for academic achievement in schools with a mix of blacks and whites led to embarrassment and protests when the white children always seemed to end up winning the academic awards and getting the best grades and scoring highest on the tests. Pushing hard for academic achievement in predominantly black urban schools led to intense resentment by the students and occasionally by parents and the community. It was not the students’ fault they were ill-prepared—racism was to blame, the system was to blame—and solutions that depended on the students’ working doubly hard to make up their deficits were accordingly inappropriate, tantamount to getting the students to cover for the system’s mistakes.

As in the case of work effort, marital behavior, and crime, the empirical evidence is accumulating that the changes in incentives in the classroom are causally linked to the trends in educational outcomes.15 But, as in the the case of Phyllis and Harold, or the case of the villager refusing to grow jute, perhaps the most persuasive evidence is one’s own answer to the question, ‘’What would / do given the same situation?” Given the changes in risks and rewards: If you were a student in the inner-city school of 1970, would you have behaved the same as you would have in 1960? If you were a teacher, would you have enforced the same standards? If you really loved teaching, would you have remained a teacher in the public schools?

Misdirected Synergism

The discrete empirical links between changes in sanctions for crime and criminal behavior, between changes in school rules and learning, or between changes in welfare policy and work effort are essential bits of the puzzle, but they are also too tightly focused. None of the individual links is nearly as important as the aggregate change between the world in which a poor youngster grew up in the 1950s and the one in which he or she grew up in the 1970s. All the changes in the incentives pointed in the same direction. It was easier to get along without a job. It was easier for a man to have a baby without being responsible for it, for a woman to have a baby without having a husband. It was easier to get away with crime. Because it was easier for others to get away with crime, it was easier to obtain drugs. Because it was easier to get away with crime, it was easier to support a drug habit. Because it was easier to get along without a job, it was easier to ignore education. Because it was easier to get along without a job, it was easier to walk away from a job and thereby accumulate a record as an unreliable employee.

In the end, all these changes in behavior were traps. Anyone who gets caught often enough begins going to jail. Anyone who reaches his mid-twenties without a record as a good worker is probably stuck for the rest of his life with the self-fulfilling prophecy he has set up—it is already too late for him to change the way he thinks about himself or to get others to think differently of him. Any teenager who has children and must rely on public assistance to support them has struck a Faustian bargain with the system that nearly ensures that she will live in poverty the rest of her days. The interconnections among the changes in incentives I have described and the behaviors that have grown among the poor and disadvantaged are endless. So also are their consequences for the people who have been seduced into long-term disaster by that most human of impulses, the pursuit of one’s short-term best interest.

Present Sticks, and a Distant Carrot

The alternative future for a Harold and Phyllis is not the executive suite and an estate in the country. It is probably no more than getting by. If I were to concoct an imaginary ending, neither too optimistic nor too pessimistic, to the story of the 1960 Harold and Phyllis it would go something like this.

When we left Harold, he had taken the job in the laundry. He was stuck with the steam press he hated. Sometimes, however, he got a chance to do a little part-time work driving a delivery truck for the laundry. After three years of this, the regular driver left and Harold replaced him. Driving the truck paid a little more money than the presses, but not much. After six years of driving the delivery truck, a truck-driver friend of Harold’s helped him get a similar job for a large company. It was a unionized job, and Harold was still working for the company in 1970, with occasional layoffs —fewer, as his seniority piled up. Phyllis had two more babies, and Harold’s wage, even though he now made $5 an hour, was barely enough to go around. But it did go around.

It is not much of a Horatio Alger story. The 1960 Harold had a little luck, no more and maybe a little less than one can reasonably expect. His experience typifies the job path of millions of American workers: starting on an unskilled job near the minimum wage, picking up a few skills along with a record as a reliable worker, eventually happening across an opportunity to move into a job with a little more money and security.

The rationale for holding onto a bad job is thus very tentative, long-term, and without guarantees: “Work hard, stick to the job no matter how bad it is, and you will probably climb out of poverty but not very far out.” For blacks, the uncertainty and distance of the incentive have been compounded by discrimination that makes it harder to get and hold jobs. The rewards for studying in school and keeping out of trouble with the law are uncertain and not enticing.

Against this meager incentive on the plus side, we have examined an array of negative incentives. The imbalance is not a function of a particular social policy. It is not a function even of a particular social system. Rather, there is this truth: The tangible incentives that any society can realistically hold out to the poor youth of average abilities and average industriousness are mostly penalties, mostly disincentives. “Do not study, and we will throw you out; commit crimes, and we will put you in jail; do not work, and we will make sure that your existence is so uncomfortable that any job will be preferable to it.” To promise much more is a fraud.

Given this Hobbesian state of affairs, why have I presented the story of Harold’s and Phyllis changed incentives as a negative one? In 1960 the couple was condemned to an income at a bare survival level. In 1970, the same miserable job plus the supplements from government support gave the two of them a combined real income more than twice as large. Why is this not progress? One answer is that what we did for the mediocre hurt many others who were not of average abilities and (originally) average industriousness. Another answer is that, even for many of the Harolds and the Phyllises, we demeaned their quality of life in ways that the added dollars could not compensate. The changes in incentives not only interacted to produce a different short-term rationality; they interacted to change the very nature of the satisfactions and rewards. Let us leave behind the economic incentives and turn to another set: the incentives associated with status.