8

Crime

PEOPLE SURVIVE. Large and increasing numbers of young persons in the 1960s were no longer in the job market, or were in the job market only intermittently, or were unsuccessful at finding a job when they tried. Large numbers of them were functionally illiterate and without skills that the larger society values. Yet they were surviving. One of the ways in which they were surviving was through crime. In the mid-1960s, in a marked departure from the trends of recent American history, the number of people engaging in criminal activity—and the number of their victims—increased explosively. The people who suffered most from this change were urban blacks.

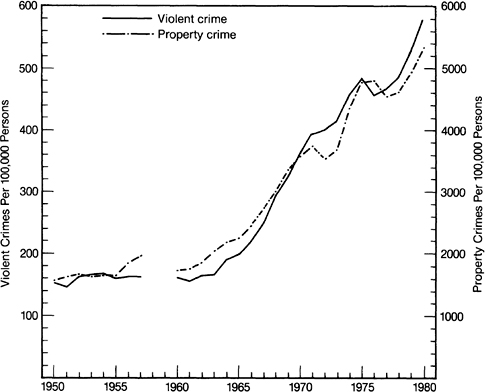

The primary source of data we shall use is the Uniform Crime Report (UCR) program conducted by the FBI. For data on victims we shall also draw on the victimization surveys that have been conducted periodically since the mid-1960s. These data, like all crime data, are subject to numerous caveats. Readers are referred to the notes that accompany specific points. Because of the inherent complexity of interpreting crime data, which deal with an especially hard-to-observe phenomenon, I shall limit the discussion to a few of the most basic trends. In all cases, we shall focus on the “index” offenses—murder, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault (summed to make the “Violent Crime” index) and burglary, larceny, and auto theft (summed to make the “Property Crime” index).1 The trendlines for the two crime indexes are shown in figure 8.1.

Crimes Reported to the Police: Indexes for 1950–1980

Data and Source Information: Appendix table 18 and note 2, chapter 8.

Note: Data for 1950–57 are based on 353 cities of 25,000 population or greater. Data for 1960-80 include all reporting jurisdictions.

Crime from 1950 to 1980: An Overview

It may come as a surprise to those who remember J. Edgar Hoover’s annual warnings during the 1950s that crime was dangerously on the rise or the 1950s movies about the breakdown of law and order (Blackboard Jungle, The Wild Ones), but the crime rate in those days was almost tediously constant and low. Violent crime remained nearly unchanged during the 1950s, while property crime probably increased slightly in the last half of the 1950s. Rates for both types of crime were stable in the first few years of the 1960s.2

Some kinds of crime actually decreased during the 1950s and into the early 1960s. Homicide, the crime for which historical data are most complete and most accurate, went from 5.3 per 100,000 in 1950 to about 4.5 throughout the last half of the 1950s, and as late as 1964 it stood at only 5.1.3

Then, in about 1964—the take-off year varies by type of crime—the crime rate started to climb steeply for both property and violent crime. The rates for the individual elements of the indexes are as follows:

| Percentage Change, 1963–80 | |

| Violent Crime | |

| Murder | + 122 |

| Forcible Rape | + 287 |

| Robbery | + 294 |

| Aggravated Assault | + 215 |

| Property Crime | |

| Burglary | + 189 |

| Larceny | + 159 |

| Auto Theft | + 128 |

All sorts of crime got worse—not only according to the UCR data, but also according to other, independent measures. The general topic of the UCR data and the “real” crime rate has been a subject of intense research and debate over the years. After a period of controversy about whether crime was really increasing at all (for a time, the increase was argued to be an artifact), a degree of consensus has been established.4 During the late 1960s and early 1970s, crime of all types did, in fact, soar.5 For trends after 1973, there is still argument. The UCR data show substantial increases in both indexes, while the National Crime Survey shows slight changes both up and down.6 The jury is still out on where the true increase lies.

The Criminals

The focus of our interest is the 1960s, and not the crime but the criminal and the victim. Who was behind the sudden rise? Who was hurt?

We begin with the criminals. We know first that they were male; that has been true for as long as statistics have been kept. In 1954, males accounted for 89 percent of arrests for violent crimes; in 1974, they accounted for 90 percent. In this regard, little changed.

Second, they were young. In 1954, persons under twenty-five years of age accounted for 40 percent of arrests for violent crimes. In 1974, that proportion had increased to 60 percent.

Third, they were more often black than white, but no more so than they had been in the past. In 1954, blacks accounted for 57 percent of arrests for violent crimes. In 1974, that proportion had dropped—not increased, as the folk wisdom usually has it—to 52 percent.

But proportionate changes do not address the issue that concerns us. Our purpose is not to fix the “blame” for the crime problem, but to identify the difference between the behavior of the poor and disadvantaged before the surge in crime and during it. We are using blacks as our proxy for that group. And in this sense, black behavior toward crime changed in a way that is qualitatively different from the way that white behavior changed.7

THE SPECIAL CASE OF HOMICIDE

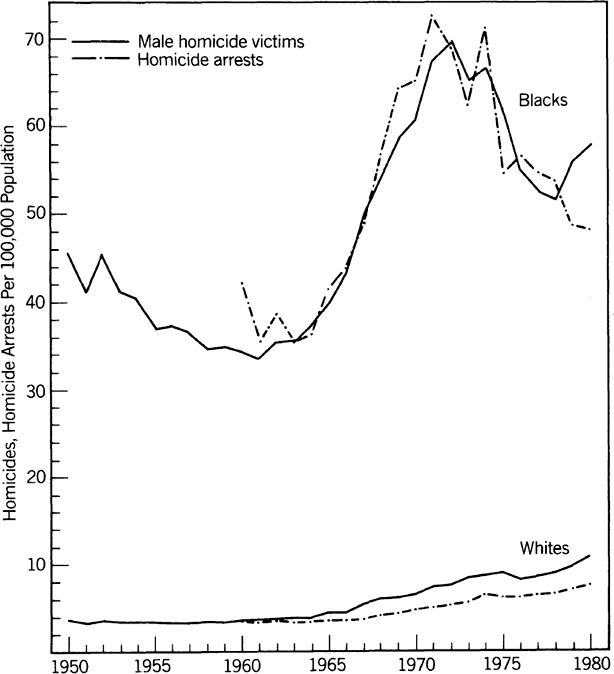

The crime for which we have the best historical data is homicide. Homicide is almost always reported; almost always solved; and has been the subject of careful record-keeping. Figure 8.2 shows the trendline for victims from 1950 to 1980, and for arrests from 1960 to 1980.

Before considering the steep, abrupt rise in the 1960s, let us consider the experience of 1950–60, when homicide victimization dropped—22 percent for black males.8 It was a large reduction for a single decade. It was all the more remarkable when one considers that it coincided with a period of rapid black migration into urban centers—a 24 percent increase from just 1950 to 1960 in the proportion of blacks living in central cities, a much faster increase than in subsequent years.9 The black homicide rate “should” have been rising in the statistics, if only because so many more blacks were moving to places where the homicide rate tends to be high. But it fell instead.

Male Homicides and Homicide Arrests by Race, 1950–1980

Data and Source Information: Appendix table 18.

If this reduction in the black homicide rate had occurred following the institution of a program that was supposed to reduce crime, it would have been cause for dozens of analyses. Perhaps because it happened on its own, it has attracted little attention, and we know little about it except for the fact that it did occur, was substantial, and was highly positive.

Then came the rise. Put simply, it was much more dangerous to be black in 1972 than it was in 1965, whereas it was not much more dangerous to be white. Lest this be thought an abstraction, consider the odds. Arnold Barnett and his colleagues at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have calculated that, at 1970 levels of homicide, a person who lived his life in a large American city ran a greater risk of being murdered than an American soldier in the Second World War ran of being killed in combat.10 If this analysis were restricted to the ghettoes of large American cities, the risk would be some orders of magnitude larger yet, and larger than it had been ten years before.

VIOLENT CRIMINALS IN GENERAL

Blacks historically have been arrested at much higher rates than whites for all violent crimes, not just homicide. The pattern in the homicide arrest data has parallels in the UCR data on arrests for the other predatory crimes that are the crux of “the crime problem.”

We may make use of these data to draw inferences despite knowing that arrest does not always mean guilt. The notes discuss some of the technical issues at length, including the contaminating factor of racism. The conclusion (as suggested by the close match between homicide arrest and victimization trends in figure 8.2) is that the trendlines are indeed interpretable as evidence of the incidence of criminal behavior. There is reason to believe that, if anything, the increase in black criminal activity is considerably understated by the official data.11

In 1960, when our detailed examination of the racial breakdown for crime other than homicide begins, blacks were being arrested for violent crimes (homicide, robbery, rape, aggravated assault) at a rate 10 times the rate for whites (arrests relative to the size of the male population aged 13–39).12 As in the case of homicide, however, the arrest rates as of the early 1960s seemed to be holding steady or dropping.

Then, as in the case of homicide, the rates went up for both blacks and whites—but in different magnitudes and different patterns. Among blacks, the increase per 100,000 was much larger, and it was much more concentrated in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Consider the period from 1965 to 1970, which “should” (if the trend had been linear) have accounted for about 25 percent of the overall change in violent crime from 1960 to 1980. The year-by-year rates are presented in table 20 of the appendix, along with additional breakdowns for property crimes and for juveniles versus adults (appendix table 21). These numbers summarize the situation for arrests for violent crimes per 100,000 males aged 13–39:

| Blacks and Others | Whites | |

| Rate of arrests in 1960 | 2,529 | 250 |

| Change in the rate, 1965–70 | + 866 | + 118 |

| Rate of arrests as of 1980 | 3,485 | 661 |

| Percent of the 1960–80 increase that occurred during 1965–70 | 91% | 29% |

Source: Computed from UCR arrest data and CPS population data. See note 12 for discussion.

The increase in arrests for violent crimes among blacks during the 1965–70 period was seven times that of whites. The proportion of the 1960–80 increase that occurred in 1965–70 was 91 percent—compared with a barely-higher-than-expected 29 percent of the white increase. In reality, the bunching in the black increase is even more concentrated than the 1965–70 period suggests. From just 1966 to 1969, black arrests for violent crime increased by 958 per 100,000—slighter more in that brief time than the net increase of 956 per 100,000 during the entire period 1960–80. It is fundamentally misleading to see the black crime problem as one that has been getting worse indefinitely. It got worse very suddenly, over a very concentrated period of time.

Interpretations of why crime increased must accommodate this unusual profile. I will suggest one interpretation in chapter 13. Another, however, presents itself so intuitively that it deserves brief comment here: The late 1960s were the riot years. The nation went through a time of intense racial strife during which blacks widely rejected the legitimacy of white norms and white laws. Crime went up as one symptom of that rejection.

As a statement about how inner-city blacks who were committing crimes during those years felt about what they were doing, the explanation may have merit; I will not argue the point. The problem with using it as a statement about why crime increased is that the increase outlasted the riots. Black arrest rates during the 1970s generally peaked in mid-decade and subsided to some extent for some crimes thereafter (as shown in appendix table 20), but as of 1980 the rates were still roughly where they were after they shot upward in the late 1960s. Broadly construed, the reason presumably lies in a socialization process that took root in the sixties. But whatever part political socializing forces of the sixties contributed to the initial surge, they cannot easily be used to account for the continuing vitality of the black crime rate throughout the 1970s. Nor is it intellectually satisfying to hypothesize that blacks “got used to” sustaining the higher crime rate out of some sort of inertia. The jump in black arrests for violent crimes (and, for that matter, for property crimes) was too sudden, too large, and lasted too long to be dismissed as just an anomaly of a turbulent decade.

The Victims

Meanwhile, what of the victims? It has become a truism in discussions of what is wrong with the American system of justice that the victim is forgotten. It is more accurate to say that black victims, and especially low-income black victims in the inner-city, have been forgotten. Judging from the available data, they have paid a far heavier price for the rise in crime than have whites.

The first good data are from 1965–66, when the President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and the Administration of Justice conducted a large-scale survey of criminal victimization. The survey, which occurred near the beginning of the rise in crime, revealed the dramatic effect of both race and economics on the probability of becoming a victim. To take just one example: Among middle-income whites (income of roughly $15,700–26,000 in 1980 dollars), only 42 per 100,000 were victims of robbery. Among poor whites (income of less than $7,800), the rate was 116. Among poor blacks, the rate was 278.13

As crime rose in last half of the 1960s, the augmented risks of daily life were vastly greater for the poor, and especially for poor blacks, than they were for the affluent and the white. To see this, let us think in terms of the numbers of persons “penalized” by being poor or black in 1979 compared with 1965. I use victimizations per 100,000 for middle-income whites as the baseline number—a sort of “standard number of victims” at any given point in history—and ask, how many more people (for each 100,000 persons) are victimized among poor whites? Among poor blacks? These are the results for 1965 versus 1979:

| 1965 | 1979 | |

| Excess victimizations among poor whites (per 100,000) | ||

| Raped | 8 | 169 |

| Robbed | 74 | 382 |

| Assaulted (aggravated) | –1 | 768 |

| Excess victimizations among poor blacks (per 100,000) | ||

| Raped | 101 | 211 |

| Robbed | 236 | 1,143 |

| Assaulted (aggravated) | 242 | 660 |

Sources: Philip H. Ennis, “Criminal Victimization in the United States. Field Surveys II. A Report of a National Survey,” President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and the Administration of Justice (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1967), 31. Timothy J. Flanagan, David J. van Alystyne, and Michael R. Gottfredson, eds., Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics—1981 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1982), table 3.12.

I put the numbers in these terms (“excess” victimizations) to emphasize a point. It is true that rising crime has been a problem for everyone. The white middle-income victimization rates in 1979 were far higher than they were in the 1965 survey—seven times higher for rape, almost ten times higher for robbery, six times higher for aggravated assault.14 But more than enough attention has gravitated to such numbers, and to the image of the black urban street mugger preying on the innocent white middle class. The purpose of the comparison I have drawn is to highlight the great human price paid for this increase in crime by poor people and blacks.15

Summary of the Federal Effort

PRIOR TO 1968, the federal role in crime-stopping had been limited essentially to the work of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, with a few other bits and pieces in the Department of the Treasury. It was a highly visible role; under the direction of J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI sustained for many years the image of an elite, nearly infallible instrument for catching criminals. But the FBI’s charter was limited to certain categories of crime (for the most part, interstate cases) and to a modest training function for local law-enforcement agencies. In the late 1960s, as the federal government was launching ambitious initiatives in every other area of social policy, it was only natural that some way would be found to apply federal muscle to the crime problem. But which way to go? Get tough (the conservative prescription)? Or attack the problem at its roots (the liberal prescription)?

The conservatives (and apparently much of the electorate) got what they wanted, a program that would try to strengthen the hand of the law enforcers in catching criminals. A national police force was out of the question. But the federal government could assist local law enforcement, whence the rationale for the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA), created as part of the omnibus crime bill passed in the election year of 1968.

LEAA provided help of all kinds. It gave grants directly to police departments, courts, and correctional facilities; it also dispensed large “block grants” to the states for apportioning to localities. LEAA’s research arm, the National Institute of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice, sponsored research to augment our knowledge about crime and its causes. It developed uniform criminal justice “standards” against which to assess and, it was hoped, reduce the enormous diversity in practices. It tried to introduce rationality and method into a system that, from a national perspective, was a tangle of local idiosyncracies and suspect traditions.

Side by side with LEAA, the federal government undertook much more extensive programs that, in the liberal view, were likely to do more to reduce crime than anything LEAA could come up with. They did not bear the label of “anticrime” programs, but their sponsors openly saw crime as the understandable response of people who lacked alternatives and saw the social programs of the late 1960s as the best hope for providing those alternatives.

The social programs were accompanied by an unlegislated but widespread alteration in the norms of operation for the criminal justice system. Sometimes these changes were mandated by court decisions, sometimes they were ordered by administrators, sometimes they just happened as a result of a collective agreement about the right way to do things. From whatever source, practices such as release on recognizance, use of probation, plea bargaining, alternative sentences, and suspended sentences expanded.

The competing demands of the two approaches were most clearly evident in the federal effort to combat juvenile delinquency. The image of the delinquent had been radically altered by the experience of the 1960s. Among members of the general public, the decade saw a transformation of the image of the delinquent from truant and hubcap thief to urban mugger. But the persons manning the antipov-erty programs saw the urban delinquent as a leading emblem of society’s failure to deal with the problems of youth, especially urban black youth. “Youth-serving” programs grew rapidly. By 1972, a federal inventory of such programs counted 166 of them, scattered among the Departments of Labor, Housing and Urban Development, Agriculture, Justice, and HEW. In 1974, the Congress acted to consolidate and coordinate the programs by creating the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. The language of the act (PL 93–415) explicitly instructed the new agency to minimize institution-alization, to focus on prevention rather than crime-suppression activities, and in general to implement the doctrine of the “least drastic alternative” (that is, choose the least punitive, disrupting option in dealing with an apprehended delinquent).

The dollar commitment to these efforts followed the familiar curve. In 1950, the combined budget of the Department of Justice and the FBI was $455 million in 1980 dollars. The combined figure climbed steadily but slowly through the 1960s (as in other instances, the increase in expenditures lagged behind the increase in rhetoric), standing at $1.2 billion in 1969, the first year that LEAA’s budget was added in. Within only three years, that total had nearly doubled to $2.3 billion. Annual funding for the Department of Justice, FBI, and LEAA eventually reached more than $3.4 billion before disillusionment with LEAA set in during the late 1970s and its allocations were cut. By 1980, annual funding was at $2.6 billion.

These figures understate the funding for programs to prevent crime by omitting the substantial sums expended under the initial antipoverty bills and by agencies other than those included in the Department of Justice. But determining how much money to assign to the anticrime effort (as opposed to general efforts to help disadvantaged populations) is highly subjective. The figures for the Department of Justice capture the bulk of the money spent directly on the criminal and the delinquent and the justice system, and as such they may be read as a minimum representation of the total effort.