2

Principles of Aquaculture

Paul C. Southgate and John S. Lucas

2.1 Introduction

Many basic principles of aquaculture are not treated systematically in other chapters of this book and are therefore considered here. Subsequent chapters describe farming methods for given species; but why were these species chosen, and what is the sequence of steps required to develop them as commercial aquaculture commodities? Many other factors including farming intensity, sections 2.2–2.5, system design (Chapter 4) and economic viability (Chapter 13) influence the commercial success of aquaculture ventures and to a considerable extent these factors are inter‐related (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 The inter‐relationships between cultured species, culture methods, farm site and economics in an aquaculture venture.

2.2 Intensity of Aquaculture

Intensity of aquaculture describes the various densities of organisms per unit volume or per unit area. It is meaningful in comparisons between the levels of farming of a species or related species. It is, however, meaningless in terms of comparisons of densities of organisms from different groups. For instance, farming tilapia at 100 kg/m3 of water in a recirculating system is considered to be intensive farming; farming marine shrimp at 50 individuals/m2 (1–2 kg/m3) in ponds is considered to be intensive culture. There are, however, characteristics of different intensities of culture that are not specific to groups, and the consideration of culture intensity will be based on these.

Intensity of culture will broadly consider the inputs into the system to maintain adequate growth of the cultured organisms. It comes under the term ‘intensity’ because the greater the intensity (or density) of cultured organisms the greater the requirement for inputs into the system.

2.2.1 Natural Aquatic Ecosystems

All ecosystems, natural and artificial, need some form of energy input to sustain them. Even if there is perfect recycling of organic matter, there will be loss of energy through metabolism and that energy must be replaced.

Natural aquatic ecosystems typically consist of primary producers, various levels of consumers (primary, secondary, etc.) and decomposers. They are self‐supporting with recycling of nutrients and input of energy from the sun. They are characterised by long and complex food webs. There are very large energy losses in this food chain. Energy transfer from one level to another in the food chain is in the order of 10% as a ‘rule of thumb’. The following is a hypothetical example of six levels in a food chain:

- sun’s energy + inorganic nutrients →

- phytoplankton (e.g., flagellates and diatoms) →

- zooplankton and filter feeders (e.g., copepods, invertebrate larvae, bivalves) →

- larger zooplankton (e.g., fish larvae, planktivorous fish) →

- juvenile fish →

- large carnivorous fish.

Thus, in this example consisting of six levels in a food chain, over levels (1) to (6).

(1) 100% → (2) 10% → (3) 1% → (4) 0.1% → (5) 0.01% → (6) 0.001%

This is a very crude approximation, but it illustrates that the final stage of this food chain, for example the large carnivorous fish, has magnitudes less energy (and food) available to it than lower levels in the food chain. The energy lost at each step (very approximately 90%) is lost through:

- metabolism: the metabolic energy required to keep the organism functioning, e.g., locomotion, feeding, digestion of food, circulation of body fluids;

- metabolic wastes excreted and undigested material (faeces) discharged;

- energy expended on reproduction; and

- energy lost to the environment as heat because metabolic processes, like engines, are not 100% efficient.

These substantial declines in energy with each step in the food chain have an obvious implication for aquaculture: it is more efficient to farm primary producers or animals that feed at a low level in the food chain. This is an important factor in developing nations, where aquaculture products are valued as a major source of animal protein and are farmed for food security rather than export trade. With the exception of aquaculture of species such as shrimp, which are directed at international markets, most aquaculture in developing countries, e.g., China and India, is derived from extensive or semi‐intensive culture based on species that feed low in the food chain (Figure 2.2). Not only is it inefficient to produce carnivorous species through a multilevel food chain, but productivity will be very poor per unit area or volume from such extensive or semi‐intensive systems.

Figure 2.2 Relative percentages of carnivorous fishes versus herbivorous and omnivorous fishes produced from aquaculture in China, India and Japan in 2014.

In many developed nations, however, the demand is for aquaculture products that are high in the food chain, e.g., in Japan. In fact, the largest demand is for top or near‐top carnivorous fish and shrimp, as these are regarded as ‘quality’ products (Figure 2.3). These must be fed high‐protein feeds, typically with fishmeal as a major source of protein. Thus, one kind of less valuable seafood is used to produce more valuable seafood, with the consequent loss of energy.

Figure 2.3 Tsukiji market, Tokyo, with frozen bluefin tuna and dealers buying them. Note the required condition of the fish: deep frozen, gutted, de‐finned and de‐gilled.

Source: Photograph by Humanoid one. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike Licence, CC BY‐SA 3.0.

2.2.2 Intensive Aquaculture Systems

Intensive aquaculture systems are a complete contrast to natural systems. In intensive aquaculture all the nutrition for the farmed stock comes from introduced feeds, with no utilisation of natural diets. Intensive systems may be in:

- ponds (e.g., for shrimp in tropical/subtropical regions) (Figure 3.1);

- cages (e.g., for marine fish farming) (Figure 3.5);

- raceways (e.g., for trout species in temperate regions (Figure 3.10); or

- tanks (e.g., for eels in Japan).

The peak stocking density achieved in each case depends upon being able to maintain the water quality conditions required by the cultured organism. Generally, stocking densities are lowest in ponds, followed by cages and with greatest densities achieved for raceways and tanks.

Intensive aquaculture is characterised by:

- very simple food chains, i.e., prepared feeds → cultured organisms;

- low energy losses from feed input, with high food conversion ratios (FCRs)1 from specialised artificial feeds;

- no recycling of energy and totally non‐self‐supporting;

- the requirement for high inputs of energy (e.g., feeds, aeration, filtration, pumping); and

- high yields per unit area or unit volume.

Water quality is usually maintained by high water exchange rates and, in some cases, by mechanical means. In intensive culture in indoor tanks, particulate waste removal, gas exchange and oxygen production are all undertaken by mechanical means. In outdoor intensive systems with a soil substrate and phytoplankton there is settlement of particulate wastes, decomposition by bacteria and gas exchange enhanced by mechanical aeration. Stocking density (mass of farmed stock per volume or area of water, expressed as kg/m3 or kg/ha) in intensive systems varies greatly with the type of system and the cultured organism, but is always relatively high.

2.2.3 Extensive Aquaculture Systems

Extensive aquaculture is used widely, especially in developing countries. It is the major source of aquaculture production in the world

Extensive and intensive aquaculture systems are contrasted in Table 2.1. They differ markedly as extensive aquaculture is part of a natural ecosystem and depends upon it for maintenance of water quality, and much of the animals’ food and other requirements. An extensive aquaculture system, therefore, has limited inputs to maintain animal growth and survival, i.e., it may have some basic organic fertilizers, such as animal and plant wastes, but no aeration, etc. These systems usually have a low stocking density, generally < 500 kg/ha, and the natural productivity of feed (plants and animals) within the system and natural gas exchange is sufficient to support the cultured organisms. Extensive aquaculture is used for pond farming and for organisms grown on or in various substrates, e.g., bivalve and seaweed farming. Seaweed farming differs, of course, from animal farming in terms of food requirements, but the seaweeds are dependent on their environment for inorganic nutrients.

Table 2.1 Comparison of the general characteristics of extensive and intensive aquaculture systems.

| Extensive aquaculture | Intensive aquaculture | |

| Establishment costs | Low | High |

| Farming systems used | Natural water bodies and simple containment structures | Fabricated structures, including tanks, pond systems, raceways, sea cages, etc. |

| Technology level | Low | High |

| Degree of control over the environment, nutrition, predators, competition and disease agents | Very low | High |

| Typical source of seed stock (plant or animal) | From nature | From domesticated broodstock (possibly genetically selected) |

| Operating costs, stocking rates and production levels | Low | High |

| Dependence on local climate and water quality | High, may be some crude adjustment of pH with lime and related substances | Low to very low |

| Monitoring of water quality | Nil | Undertaken regularly |

| Food source for cultured animals | Natural food organisms; often some input of animal and plant wastes | Pelletised fabricated feeds, which must be nutritionally complete |

| Production (kg/ha/yr) | Low (per unit area or volume) (20–500) | High: maximising output of product in minimum surface area, water volume and time 5000–100 000 + * |

| Production costs | Low to very low | High to very high |

* The highest values are extrapolations from m2.

Apart from seaweeds and bivalves, a considerable amount of extensive aquaculture is of low‐value fish, such as carps and tilapias. This is possible because of the low costs of production associated with extensive culture.

Extensive versus intensive aquaculture is rather like the difference between:

- feed‐lot cattle, which are totally dependent on the feed‐lot environment and the feed provided (intensive culture);

and

- free‐range cattle roaming through natural vegetation on a large cattle station or ranch, feeding on natural pasture and with minimal husbandry (extensive culture).

In each case there is a harvest of beef, but the harvest per hectare is magnitudes higher from the feed‐lot system. None‐the‐less, both systems can be profitable. Profitability depends on the difference between total cost of production and farm‐gate value of the product.

2.2.4 Semi‐Intensive Aquaculture Systems

There is no abrupt cut‐off point between extensive and intensive aquaculture (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2 Examples of extensive, semi‐intensive and intensive grow‐out aquaculture showing the continuity between levels.

| Harvest rate (kg/ha) | Examples of farmed animals and structure | Farming methods | Level of culture |

| 90 | Freshwater crayfish, large‐mouth bass in dam | Simple stocking | Extensive |

| >10 000 | Marine mussels raft/longline | No supplementary feeding, suspended in water currents to filter feed | Extensive |

| 900 | Carps, catfish, tilapia in pond | Some supplementary feeding and pond fertilisation, possible emergency aeration | Semi‐intensive |

| 6000 | Shrimp in pond | Almost complete diet, regular water exchange, aeration | Intensive |

| 15 000 | Sea bream, sea bass Atlantic salmon in cage | Complete diet | Intensive |

| >60 000* | Eels, barramundi battery tank systems in warehouse | Complete diet, recirculation and rigorous water quality control | Intensive |

* Extrapolated.

Semi‐intensive aquaculture is used as an approximation to describe the middle ground. Semi‐intensive aquaculture systems rely to an extent on natural productivity; however, there is more supplementation of the natural system. Supplementation may take many forms, including:

- provision of aeration to maintain dissolved oxygen (DO) levels;

- addition of inorganic or organic fertilizers to improve natural productivity; and

- addition of prepared feeds (supplemental feeding).

Semi‐intensive culture is almost exclusive to ponds and allows for an increase in the stocking density within the pond. Further comparisons of the three levels of culture intensity related to tilapia culture are given in Table 18.2.

2.3 Polyculture

Polyculture is the deliberate farming together of complementary species, i.e., species occupying complementary niches, especially in regard to their food and feeding (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4 Natural food resources utilised by major fish species cultivated in Chinese carp polyculture ponds. Grass carp (a) and wuchang fish (b) feed upon terrestrial vegetation and aquatic macrophytes; silver carp (c) graze upon phytoplankton; bighead carp (d) consume zooplankton; tilapias (e) feed upon both kinds of plankton, green fodders and benthic organic matter; black carp (f) feed on molluscs; and common carp (g) and mud carp (h) consume benthic invertebrates and bottom detritus.

Source: Zweig 1985. Reproduced with permission from Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Polyculture increases production per unit area or unit volume of the pond by maximising the utilisation of nutritional niches within the pond. A greater proportion of the primary production is utilised as the target species are linked to more of the food webs than a single species, resulting in increased productivity. They also have the effect of reducing the complexity of the food webs because they ‘cover’ a high proportion of primary production at its sources with their feeding. In these ways, polyculture systems may average fish production of ca. 3 t/ha/yr in ponds in which there is heavy addition of manure fertilizer. With supplemental feeding there may be yields up to 16 t/ha/yr. Carp polyculture is described in greater detail in section 16.5.2 (Carps).

In some semi‐intensive systems, such as ponds, there may be stocking with species that facilitate a target species’ growth and health through supporting activities, e.g., a detritivore removing benthic waste from the environment before it creates anoxic conditions in the lower water column; carnivorous fishes that keeps down the numbers of small fishes that would steal the soft‐shelled turtles’ food.

A new form of polyculture that is being researched is the use of effluent from ponds, e.g., shrimp ponds, for the farming of complementary species. The effluent, rich in nutrients and sediment and potentially an environmental hazard, may be passed through further ponds containing animals or plants that extract the nutrients and sediment from the effluent. There may be

- bivalves, which filter the water of sediment, microalgae and some bacteria;

- macroalgae, which extract nutrients from the water (Figure 2.5); and

- mangroves which trap sediments with the production of wood.

Figure 2.5 An experimental 150 000 L raceway system used to treat waste water from a shrimp farm in north Queensland, Australia. The raceways contain green seaweed (Ulva sp.) that removes dissolved nutrients, resulting in a secondary commercial product for the farm.

Source: Reproduced with permission from MBD Energy Ltd.

The objective is not only to restore the quality of the effluent water, to the extent that it can be recycled into the aquaculture system or discharged, but also to produce a commercial crop from the effluent‐treating organisms.

For land‐based intensive aquaculture systems such as shrimp farming, environmental regulation of discharge has increased worldwide and this has provided impetus to develop improved waste management systems, beyond rudimentary systems using single‐step settlement ponds. Contemporary approaches to this problem include multistep systems that sequentially remove particulates and dissolved nutrients (Castine et al., 2013), and may involve assimilation of dissolved nutrients into harvestable biomass such as seaweeds (Figure 2.5) providing secondary products of commercial value. Another relatively recent development is that of polychaete‐assisted sand filter (PASF) systems that utilise shallow sand beds containing polychaetes (Perinereis spp.) to filter aquaculture effluent. The sand‐worm filters can remove significant quantities of suspended solids, chlorophyll, nitrogen and phosphorus and produce a valuable by‐product (worms) that are used in shrimp maturation diets and as fishing bait (Palmer, 2010). These developing forms of polyculture differ from traditional polyculture in that the complementary species are isolated in different parts of the system.

Similar technology is also being utilised in some countries to ‘upgrade’ the quality of recycled water to increase its value as a resource in a cost neutral fashion. Aquaculture recycled water, only previously usable for plantation watering, can be used for horticulture activities.

2.4 Integrated Agri‐Aquaculture Systems

Aquaculture was traditionally developed on an integrated basis, and much aquaculture in Asian countries still operates in this way. Integration involves:

- growing a variety of aquatic species in a single body of water;

- water re‐use for successive aquaculture species or other crops; and

- integration of aquaculture with other farm production or by‐products.

Traditional integrated aquaculture usually occurs on a family farm in which there are plant crops, animal rearing and aquaculture. Aquaculture is extensive and the farmed animals are low in the food web. Ponds are fertilized with faeces from pigs, ducks, humans, etc., whatever is reared or used on the farm (Figure 2.6). Wastes from crops, e.g., stubble from cereal crops, may be added to the ponds as food for benthic feeders and detritivores. Ponds are not drained but re‐used for successive aquaculture crops. In some cases, the aquaculture animals are added to fields where the crop, typically rice, is grown partially submerged in water. Freshwater crayfish (section 23.4.5.2) and Chinese mitten crabs (section 23.3.3.5; Figures 23.6 and 23.7) are examples of this. The cultured animals feed on the plant waste materials and grow, and are harvested after the crop, when the field is drained. A double crop, plant and animal, is obtained from the field.

Figure 2.6 Fish pond and vegetable garden on a farm near Yangshuo, Guangxi, southern China. The shed over the pond is probably used as a latrine and for storage.

Source: Reproduced with permission of John Lucas.

Modern aquaculture in developed countries has moved against integrated aquaculture. The move has been towards developing monoculture systems for high‐value species with single use of water. However, the limited availability of water and realisation of the global importance of water resources has led to a move towards aquaculture integration in countries where monoculture industries have developed.

Integrated agri‐aquaculture systems (IAASs) have been variously defined (see Cohen, 1997; Edwards, 1998). The basic premise of IAASs is the multiple use of water for both traditional terrestrial farming and aquaculture in a profitable and ecologically sustainable manner. As a result, integrated agri‐aquaculture embraces a diversity of practices, systems and operations.

Water is one of the world’s most precious and inefficiently utilised natural resources. Integration of farming practices to enhance productivity and water‐use efficiency will contribute to the ecologically sustainable development of natural resources. IAASs allow for irrigated farming systems and the multiple use of the same water, typically for fish production first and then for irrigation.

Presently, IAASs most commonly occur in countries with very limited water resources. In many developing countries of the world and in Israel, IAASs are highly developed and make optimal use of the available water. In Israel, fresh surface water and brackish groundwater have been utilised in the integrated farming of a variety of fish species with a variety of land crops (Cohen, 1997). In Asian countries, fish, rice crops and ducks have been integrated to better utilise available water, land and nutrients.

In developed countries, such as the USA and those in Europe, IAAS technology has generally been limited to small‐scale systems linked to irrigation farming. Opportunities commonly include use of traditional farm water storage facilities (dams), irrigation channels, ground and surface water and inland saline groundwater. With advances in technology such as floating raceways, larger scale systems are now being trialed.

2.5 Static, Open, Semi‐Closed and Recirculating (Closed) Systems

2.5.1 Static Systems

Much global aquaculture production uses traditional pond farming methods. These ponds are static, with no exchange of water during the farming period. There may be some topping up to offset evaporation.

Static pond farming is usually extensive because of major problems in maintaining water quality under conditions of a large biomass of cultured animals per unit volume of static water (Table 2.3). Increasing biomass requires increasing inputs of fertilizers and supplementary food input to maintain productivity. This, in turn, requires management for such water quality problems as unacceptable levels of nitrogen compounds and low DO (Dissolved Oxygen) levels at night. With supplementary aeration it may be possible to maintain DO with a higher biomass and achieve greater productivity (Figures 3.12 and 4.9). Aerators are, however, often not available or feasible (without electricity) in rural regions where static pond farming is employed.

Table 2.3 Example of aquaculture in combinations of different levels of farming intensity together with open, static, semi‐closed and recirculating (closed) systems.

| Farming intensity | |||

| System | Extensive | Semi‐intensive | Intensive |

| Open | Long‐line farming of scallops, table oysters in mesh baskets | Enclosures within freshwater lakes for culturing fish, such as tilapia | Sea cage farming of fish, such as sea bream, sea bass, Atlantic salmon |

| Static (ponds) | Carp polyculture in ponds, milkfish farming in lakes | Freshwater fish polyculture with aeration | Saltwater crocodiles |

| Semi‐closed | Mud crab farming in tidal ponds in mangroves | Pond farming of shrimp at 20 animals/m2 | Pond farming of shrimp at ca. 50 animals/m2 |

| Closed | X | X | Indoor culture of high‐value fish |

X, very uncommon.

2.5.2 Open Systems

In these systems the environment is the aquaculture farm, i.e., the farming organisms are confined or protected within the farm in a vast amount of water (e.g., a lake or an ocean) so that water quality is maintained by natural flows and processing. There is no artificial circulation of water through or within the system. The following are two examples of open systems.

- Cage systems are classified as open systems when they are placed within a large body of water such as an ocean or an estuary (Figures 3.4 and 3.5). In these cage systems the fishes are generally at high density and formulated feed is supplied (Figure 2.7). Water quality is, however, maintained by natural currents and tides. Therefore, these are intensive open systems (Table 2.3).

- Bivalve farming on racks or long‐lines placed in the open water is an open system (Figures 2.14, 5.2 and 24.13). Natural currents and tides maintain water quality. The bivalves gain their food by filtering phytoplankton from the water flowing past. These are extensive open systems (Table 2.3).

Figure 2.7 Yellowtail, Serolia rivoliana, cultured at high density in an open ocean sea cage off the Kona Coast of Hawaii.

Source: Kampachi Farms. Reproduced with permission from N. A. Sims, Co‐CEO, Kampachi Farms, LLC.

Open systems tend to have low operating costs, as there is no requirement for pumping. Capital costs vary greatly depending on the type of farming, with bivalve farming systems generally of low cost and intensive fish cage farming systems of high capital cost. Generally, sites for open water farming are not available for freehold purchase and must be leased from the appropriate government agency (e.g., oyster leases). Ideal locations for open water farming are also often popular for other uses, such as boating, and user conflict can result.

Open systems are prone to problems that either don’t apply to or are more difficult to mitigate than in other farming systems. A major problem associated with site selection for open systems is lack of control over water quality. The quality of water depends on local factors and cannot be moderated. It is therefore essential that the farmer is aware of all extremes of water quality occurring at the site, i.e., water temperature, salinity, algae blooms, prior to developing an aquaculture facility. Seasonal variations in environmental factors may result in large variations in growth rates, and local differences in the environment may also cause major differences in growth and survival. Climate change has now introduced an additional variable to the location of new farms and the operation of existing farms. Historical water quality data previously used to indicate the likely future water quality may be of limited use. Scenario testing, i.e., potential changes in water quality that may occur with climate change, will be required to inform choices of farm location and management. Possible seawater rise as a result of climate change may also impact on estuarine or delta based industries. For example, the Vietnam catfish industry may have a greater saline water source in the future.

Open systems are also more prone to predation. Predation can be controlled through the addition of some protective devices (Figure 5.2); moreover, methods of predator control in most countries must be non‐destructive (not shooting!) and are generally expensive to operate and maintain. Predation may also extend beyond wild animals to human interference or poaching. Although interfering with aquaculture equipment and stock is an offence in most countries, enforcement is difficult and the responsibility to protect equipment and stock often falls to the system operator.

2.5.3 Semi‐Closed Systems

Semi‐closed systems include ponds, tanks and raceways where the water supply is confined in discrete units with some flow‐through of water. These systems fall distinctly between static and open systems in terms of water exchange with adjacent water sources. There is a degree of water exchange in semi‐closed systems that are substantially greater than in static systems and much less than in open systems. Another major difference between semi‐closed and open aquaculture systems is that water is continuously or frequently brought to the farm. The water source may be freshwater, brackish or marine. Characteristics of freshwater and brackish water sources are outlined in Tables 2.4 and 2.5 and aspects of marine water supply are outlined in Chapter 3.

Table 2.4 Freshwater sources for semi‐closed farming.

| Water source | Advantages | Potential problems |

| Lakes and reservoirs | Large volumes available |

|

| Streams or shallow springs | High oxygen content |

|

| Deep springs | Quite constant supply Sediment free |

|

| Wells | Quite constant supply Sediment free |

|

Table 2.5 Brackish water source for semi‐closed farming.

| Water source | Advantages | Potential problems |

| Estuary |

|

|

|

| |

| ||

| ||

| ||

|

Water is drawn from a reliable source and flows to and through the farm, driven by gravity, tidal exchange or, most commonly, pumping. In these systems, water is exchanged to maintain water quality. As the farm is not located within a natural aquatic environment, there is a degree of control over water quality, but only to the extent that water flow can be increased, decreased or stopped. If the source of water becomes contaminated or of unacceptable quality, the farmer can stop the water flow, but this leaves the stock in static water of deteriorating quality. The benefits of semi‐closed systems vary from:

- enhancing production from ponds by exchanging some water while maintaining some reliance on natural processes of the pond ecosystem;

to

- complete reliance of water quality on water exchange (e.g., raceways) resulting in a large increase in production.

In the latter, water use per unit of production is extremely high. In these systems water may make single or multiple passes through the culture structures.

If water is exchanged by pumping, the costs of pumping may be high, depending on the height water has to be pumped and the volume of water exchanged (section 3.4.3).

In large semi‐closed systems with semi‐intensive to intensive culture (Table 2.3), water flow is generally high to very high. It is generally recommended that water exchange is in the range 5–10% per day for semi‐intensive ponds (Boyd, 1991) and up to 30–40% per day for intensive pond (Yoo and Boyd, 1994). An exchange rate of 1% per day is equal to 100 m3/ha/m of average pond depth (Yoo and Boyd, 1994). That is, an exchange rate of 5% per day in a 1‐ha pond of average depth 2 m requires a total of 1000 m3/day of water. In addition to this, water loss from evaporation and seepage must be considered. Boyd (1991) provides further details for determining exchange rates.

2.5.4 Recirculating (Closed) Systems

Recirculating systems usually have minimal connection with the ambient environment and the original water source (Table 2.6). These systems have minimal exchange of water during a production cycle, hence the description as ‘closed’ systems. Water is added to offset the effects of evaporation or incidental losses or, more frequently, to maintain water quality. Some water is discharged and replaced each day in most recirculating tank systems with intensive culture (Losordo, 1998a, b). This arises from aspects of the regular maintenance system, such as removing accumulated solids from filters. Water quality in completely closed tank systems with intensive culture is much more difficult to maintain than in systems in which there is a regular 5% or more replacement per day (Losordo, 1998a, b). Even with some limited water exchange each day, water quality within a recirculating tank system will only be maintained by artificial manipulation (Figure 4.15). Losordo et al. (2001) reviewed these systems and their critical considerations, status and future.

Table 2.6 General characteristics, advantage and potential problems of recirculating aquaculture systems in indoor conditions.

| Characteristics | Advantages | Potential problems and disadvantages |

|

|

|

The cost of construction and production in intensive recirculating tank systems has limited the commercial development of these systems for grow‐out production, i.e., the final farming phase to market size. However, the possibility of high yields with year‐round production close to markets drives their development. Some of the advantages and potential disadvantages of recirculating systems are outlined in Table 2.6.

2.6 Selecting a New Species for Farming

The following sections mainly relate to aquaculture initiatives in developed countries. Which species shall be farmed? What type of system will be used to grow the selected species? The inter‐related components for aquaculture were outlined in Figure 2.1. Unfortunately, many new aquaculture ventures fail because at least one component wasn’t properly considered before undertaking the venture.

Criteria for selecting new species for commercial aquaculture were outlined by Avault (1996). The choice of aquaculture species is often a balance between biological knowledge and economics.

2.6.1 Selecting an Appropriate Species

The biological knowledge required for successful farming of a species is diverse and will be outlined in the following section.

There is a wide range of uses of aquaculture products, and while there are hundreds of farmed species, there is potential for many more. Aquaculture is much more than production of protein for human consumption, although this is the most frequent objective of new farming ventures. Other production objectives of aquaculture include:

- industrial products, e.g., agar/alginate;

- pharmaceutical products, e.g., UV‐resistant compound, cancer‐fighting agents;

- ‘gem stones’ e.g., pearls from pearl oysters, abalone and conch;

- augmenting wild stocks for conservation, wild fisheries or recreational fisheries;

- ‘ornamental’ species for the aquarium industry;

- crocodile and alligator hides (Figure 2.8); and

- food and feed components for the early development stages of cultured fish and invertebrates, e.g., phytoplankton and zooplankton.

Figure 2.8 Crocodile farm.

Source: Photograph by Rick Bayok. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike Licence, CC BY‐SA 3.0.

Thus, the characteristics of the selected species will vary according to the production objectives. The use of the product may determine the market price, and this will in turn influence the economic viability of the venture.

2.6.2 Requirements for a Suitable Farmed Species

Aquaculture projects frequently fail as a result of an inadequate understanding of all facets of the biology and economics of the target species or by selection of species that do not have appropriate characteristics. Avault (1996) listed the following issues to be considered when selecting an aquaculture species.

2.6.2.1 Water Temperature and Water Quality

Each species has specific requirements for various water quality parameters. These parameters include temperature, dissolved oxygen, salinity, pH and ammonia/nitrite/nitrate nitrogen (Chapter 4). It is important to understand not only the optimum levels for growth, survival, reproduction and condition, but also the tolerated ranges of the target species for these parameters.

2.6.2.2 Growth Rate

Species showing rapid growth rates to reach market size are clearly preferred for aquaculture. It is generally considered inappropriate to farm a species that requires more than two years to reach market size. Furthermore, growth rate must be considered in relation to risk and economics. Risk comes with the chance of losing the product to disease or system failure during the grow‐out period. If, however, the risk of product losses is low, or the product is of substantially higher value than similar faster‐growing species, then species with slower growth rates may be cultured effectively.

2.6.2.3 Feeding Habits and Nutrition

The feeding habits and food requirements of a species can greatly influence the profitability of farming. Feeding habits can generally be divided according to production phase, i.e., hatchery/nursery, juvenile and grow‐out phases. In general, feeding habits change markedly after the hatchery/nursery phase, with the juvenile and grow‐out animals having similar feeding habits. Thus, the nutritional requirements for both live and artificial diets, feeding techniques and expected growth rates must be known as comprehensively as possible. Determining nutrition requirements is a complex process, which is still being undertaken for long‐term cultured species, but testing with available commercial feeds is appropriate.

Feeding habits include the foods and the position in the water column in which the animal feeds. Food requirements affect feeding costs, with animals feeding higher in the food chain, i.e., carnivores, generally requiring more expensive diets/feeds. The ability to accept an artificial diet is also of importance, as live feeds are expensive to produce in terms of space, labour and consumables. At the other end of the spectrum, extensively cultured grazing gastropods and filter‐feeding bivalves feed from their environment without supplementation. The position in the water column at which the animal feeds can affect the type of aquaculture system used. For example, if a fish is a benthic feeder, it is unlikely that it can be effectively cultured in a floating cage.

2.6.2.4 Reproductive Biology

A reliable source of juveniles or ‘seed’ is fundamental to all aquaculture ventures. Seed must be available in the required quality and quantity and at the appropriate times. Although some aquaculture industries have been developed using wild‐caught seed, e.g., table oysters and milkfish, it is highly desirable that the target species can be bred in captivity. In addition to being able to reproduce in captivity, it is also desirable that a farmed species has high fecundity, either a large number of eggs per spawning or multiple spawnings per season. High fecundity helps offset the high costs of maintaining and spawning broodstock. Captive breeding is of course necessary for genetic selection.

2.6.2.5 Hardiness

To achieve acceptable levels of production, it is likely that farmed species will be exposed to conditions that differ considerably from their natural environment. Farmed animals generally experience social crowding, a degree of diminished water quality and handling. All these parameters will create stress. The cultured species should be able to adapt to these stresses and maintain high survival and optimal growth. It is important to consider the effects of these stresses on all stages of the life cycle. Combined with the ability to adapt to the stresses of farming is an ability to resist disease. The likelihood of disease occurrence and proliferation is higher in farming than in the wild, and a species susceptible to mass mortalities from low levels of disease is undesirable.

2.6.2.6 Profitability

A thorough investigation of the markets for the target species is an essential undertaking in aquaculture venture. As previously described, there is a range of uses for aquaculture products, all of which may be considered when selecting the target species. Some species may also have several marketing opportunities. Some fish species may be:

- sold as fingerlings for restocking;

- grown to plate size; and

- grown to a larger size for filleting.

A table oyster may be sold to oyster farms as seed or sold after grow‐out as adults in the shell, or shelled, or shelled and smoked. It is important to identify the best market(s) for the product and the market values of potential products. A decision on the economics of farming can then be made.

2.6.2.7 Economics

Aquaculture, especially in developed countries, is fundamentally a way to make money, whatever else are its attractions. At all stages of selecting an aquaculture species, the underlying aim is profit (Chapter 14). Thus, all the costs of production, including stock, feed, electricity, interest on money borrowed, labour, etc. and the returns from the sale of the product must be estimated with detailed cost and return analysis.

Despite targeting a species that is very suitable for farming, an aquaculture operation may fail if:

- there is insufficient demand for the product; or

- the product can’t be produced at a profitable level compared to other sources on the market.

Economists have produced a variety of software that allows prospective aquaculture farmers and aquaculture companies to undertake all the appropriate economic calculations. The economic feasibility of the farming can be determined by combining market analysis and biological feasibility.

There may be alternative production systems for rearing a species. It may be possible to match the type of production system, and its associated costs, to the species and its market price to achieve profitability. For example, growing fish in an intensive, recirculating tank system may cost USD 4–8/kg to grow to market size. The market price for this species would clearly need to be significantly higher than the production cost to ensure economic feasibility. If not, then the farmer or aquaculture company must investigate an alternative cheaper method of production, e.g., semi‐intensive pond culture, which may reduce production costs per kilogram of market size fish.

It is not just a matter of having a positive balance of profit to costs. If the rate of return on the investment in an aquaculture venture is not greater than the prevailing standard rate of return from investments, then the venture is effectively unprofitable. The committed funds would be better used for a lower‐risk investment (Chapter 14).

2.6.3 Compromise

The ideal farmed species possesses all the above characteristics; however, few if any species are ideal, and generally there is some compromise in terms of these characteristics.

The choice of a species for aquaculture production may be between these extremes:

- A species or product has an existing market and can be readily marketed. The farmer or aquaculture company can enter an established market and the decision to farm is based upon the economic attractiveness. If there is biological information to allow management throughout the life cycle, then, given economic feasibility, successful farming is nearly assured. There may be problems in farming, however, if there are aspects of the life cycle that are incompletely understood. The farmer or aquaculture company must take the risk of failure, despite the ready market.

- The biological feasibility of farming is high, but there is a limited market, or the market price is low. In this case, the decision to farm is based upon the fact that control of the life cycle is complete, rather than on immediate economic attractiveness. Obviously, the product must be marketable, but the risk is whether there are sufficient time and resources to develop a market. If a market is established, and given that farming is economically feasible, the venture will be successful.

If a product does not suit a market, farming the product will be unsuccessful; however, an alternative to changing the species may be a matter of changing the market niche or undertaking an innovative marketing campaign. This approach has been exemplified for a number of fish species, e.g., tilapias in Asia (Chapter 18) and channel catfish in the USA (Chapter 19), and for mussels exported from New Zealand as ‘Kiwi clams’ (Chapter 24).

2.7 Developing a New Farm or a New Farmed Species

2.7.1 Rapid Development

If the aquaculture species of choice is farmed widely in the region and techniques are well developed, then developing a new farm for the species may be relatively simple and the major concerns regarding success will be economic. Establishing an operation will be a matter of applying existing technologies to the chosen farm site. This is the pattern of development throughout most of the regions where aquaculture is growing rapidly. The growth of Procambarus clarkii farming in China is a prime example of this pattern (Figure 23.10).

This is not always the case and some trial and error with husbandry may be required: the technology from one site is not automatically applicable to another site, especially for pond aquaculture. There are local differences in soil type, topography, water accessibility, etc., but the operation should come in at the commercial trial stage (section 2.7.1.4). Furthermore, provided the training of employees is satisfactory (it is very advisable to employ people who are already experienced in the industry), success is likely.

2.7.2 More Technically‐Demanding Development

If the species is only farmed in other regions, then development may be more difficult. Difficulties may arise from production differences, e.g., the species requires more technological development or regional climatic differences can impact upon traditional or developed farming technologies.

If the target species is a new species to the aquaculture industry, or if it is proposed to farm the species under very different conditions, e.g., intensive vs. extensive, it will be necessary to develop suitable farming techniques. The following development protocol is recommended to determine the suitability of the species, especially in developed countries where large investments are committed.

2.7.2.1 Stages of Development

Many aquaculture ventures fail at various points during the following development protocol. The key is not to make large investments in a new species and methods of farming until the preliminary stages, outlined below, give some confidence in its potential.

This process of developing the farming of a new species in a developed country is most likely to be the prerogative of an aquaculture company rather than a single farmer, in view of the capital costs, diverse activities and expertise, including legal expertise, required. As well as early establishment costs, considerable capital is needed to sustain the operations unit they develop to the point where there are net positive returns. This will take a substantial period.

Screening

The aim of this stage is to make an informed decision about the farming potential of the species.

Provided the species looks promising, any legal constraints to farming must be investigated, e.g., permits, translocation issues. This will inform a prospective company of the legal possibilities.

It is important at this stage to produce some preliminary figures on the potential returns on investment. These figures must be realistic and not work on the lowest possible production costs and highest possible production rates and market price. By adopting mid‐range values, the reality of farming the species is more likely to be reflected. Potential investors must err on the conservative side. Determining the return on investment must incorporate all economic aspects, including capital investment on land purchase and infrastructure, depreciation of assets and interest rates on borrowed money, as well as annual production costs. In addition, the potential return on the invested capital if it was used in an alternative investment strategy must be calculated (Chapter 14). Software programs are available commercially and often through government aquaculture extension agencies, to produce the appropriate economic information.

The target species may be accepted or rejected at this stage based upon its desirable characteristics, its biological potential for farming, the availability of a market and the economics of farming. If the species is accepted, development should proceed by moving to the research stage.

Research Trials

After screening there must be research into the biology and husbandry of the species. This research will provide the information required for the development of appropriate farming systems and husbandry techniques (Figure 2.9). Research trials will investigate factors such as environmental requirements of the target species, optimal stocking densities and feeding protocols, reproductive physiology and broodstock husbandry, nutritional requirements and growth rates of relevant life cycle stages.

Figure 2.9 There are ready markets in SE Asia for high‐value tropical sea cucumbers such as Holothuria scabra, where they may fetch more than USD 200/kg when dried. But methods for commercial culture have not yet been developed for this species.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Cathy Hair.

The species may prove to be undesirable on the basis of one or more of the above areas and be rejected.

If the trials are successful, this may be the appropriate stage, if not earlier, to choose a farming site and undertake the legal processes involved in acquiring the site or some title to the site.

Pilot Trial

Using the information derived from research trials, a pilot trial can be conducted. Aquaculturists consider this as taking culture from the laboratory into the ‘real world’. In this trial, the farming structure, e.g., tanks, ponds, cages, raceways, is small and a low number of animals used. This trial will provide semi‐commercial values for and/or information on:

- survival;

- potential yields;

- FCRs;

- water quality problems;

- handling difficulties; and

- economics of farming.

It is important at this stage to determine impediments to larger‐scale farming. If problems are indicated, the company should either fund more research, or advise the staff to modify techniques and conduct further pilot trials.

Commercial Trial

The commercial trial is a scale‐up of the pilot trial. During commercial trials the company must use full‐sized farming units and larger numbers of animals. A site must have been secured and capital invested on infrastructure development.

The commercial trial provides information on production costs and potential profits, and on the husbandry of large numbers of animals. The commercial trial may identify difficulties in animal husbandry or cost dynamics associated with the larger farming systems.

At this time some preliminary market development must be undertaken. However, it should be noted that it is difficult to establish firm markets before full‐scale production is established.

Full‐Scale Production

Full‐scale production involves the company developing the full number of farming units. It is important that other aspects of the farming units, such as structure size and shape, flow dynamics and husbandry, are not modified from those used in the commercial trial. Full production requires substantial capital and infrastructure development at the site. Under‐capitalisation, leading to problems of liquidity, has been a major problem in developing aquaculture industries.

Firm markets, e.g., restaurants, major retailers, can be established as production expands.

2.7.2.2 Time‐Scales for Development

The time‐scale for development of a new species is important for aquaculture companies undertaking this venture. In the above protocol the length of time spent at each stage depends on many factors.

After the initial Selection and Research phases, it will involve:

- pilot trials which may be over two growing seasons; and

- commercial trials which may be over two growing seasons.

There is a long period before commercial production, but omitting steps within this protocol is a common mistake in aquaculture development. It is often costly and results in the failure of many new aquaculture ventures. Prospectuses for new companies often do not include a development protocol, and many ventures proceed with insufficient information about farming requirements of the target species. Many ventures targeting new species move directly to commercial trials or attempt full‐scale production. Omitting pilot trials, even if the species is well known, or not correcting major problems before moving to commercial trials often results in the construction of inappropriate aquaculture facilities and economic failure. However, sequential development, as outlined above, provides a sound basis for decision‐making and appropriate progression of aquaculture ventures.

Another factor arising from the duration of aquaculture development of new species is that the aquaculture venture must have been planned with sufficient capital resources to cover the period of years before there is full‐scale commercial production and net positive flow of profit begins. As is evident above, this can be a long and costly period for a venture with a new species. It is not uncommon for there to be too much optimism about the time to profit from the farming of an exciting new species and the venture flounders as funds are exhausted.

2.8 Case Studies

The following case studies present brief outlines of farming and marketing for some aquatic animals that have met with varied success for commercial aquaculture. They illustrate some of the key drivers of success and bottlenecks to commercial development and long‐term sustainability.

It should be noted that these case studies show completely different time‐scales for developing the farming of new species on small farms in undeveloped countries compared to the time‐scales in developed countries. In the case of spiny lobsters, the farmers bypassed the extremely difficult culture of early larval stages and collected post‐larvae in the field. They also had the advantage of knowing the kinds of food that decapod crustaceans need. Farmers in French Polynesia used the same approach in bypassing the culture of pearl oyster larvae and collecting post‐larvae, known as ‘spat’. They also had the advantage that there was a history of cultured pearl oyster farming in Japan and technicians were available to ‘seed’ the pearl oysters for cultured pearl production (section 2.8.3).

2.8.1 Case Study 1: Spiny Lobsters

Spiny or rock lobsters occur from the tropics and subtropics (mainly the Panulirus species) to temperate waters (mainly the Jasus species). They inhabit protective habitats in reefs and other hard substrates. There are fisheries for spiny lobsters in many parts of their distributions and typically the natural stocks are overfished due to high market demand. Spiny lobsters have the highest or near highest market value of all decapod crustaceans. A capture fishery of 6,000 t/yr, based on the Western Australian spiny lobster (Panulirus cygnus), has a value of ca. USD 200 million/yr. They are very valuable in Asian markets as a live product and exporters obtain USD 30+/kg. Live painted spiny lobsters, Panulirus ornatus, are particularly popular because of their attractive pigmentation. Aquaculture has a potential advantage over capture fisheries in more readily producing live product and pursuing this lucrative market. Also, importantly, it would overcome the limitations of widespread overfishing. Thus, in countries such as Japan and Australia there is much interest in farming spiny lobsters.

Routine commercial farming of spiny lobsters through their life cycle is one of the ‘Holy Grails’ of aquaculture, i.e., a target that will not be achieved without a great deal more effort and research. Breeding stock can be maintained in broodstock tanks and readily spawned, producing numerous eggs; but the larval stages that follow require 8 months to almost 2 years to complete the planktonic phase of their life cycle. To sustain the larvae over such a long period of time requires a huge technical commitment. Furthermore, the chances of bacterial infection, contamination, equipment failure and other sources of culture ‘crashes’ are high over such a protracted period. Having mass mortality in a culture of 7‐month‐old larvae is catastrophic compared with having mass mortality in a culture of 7‐day‐old shrimp or bivalve larvae, which can be discarded and then the culture process begun again quite promptly.

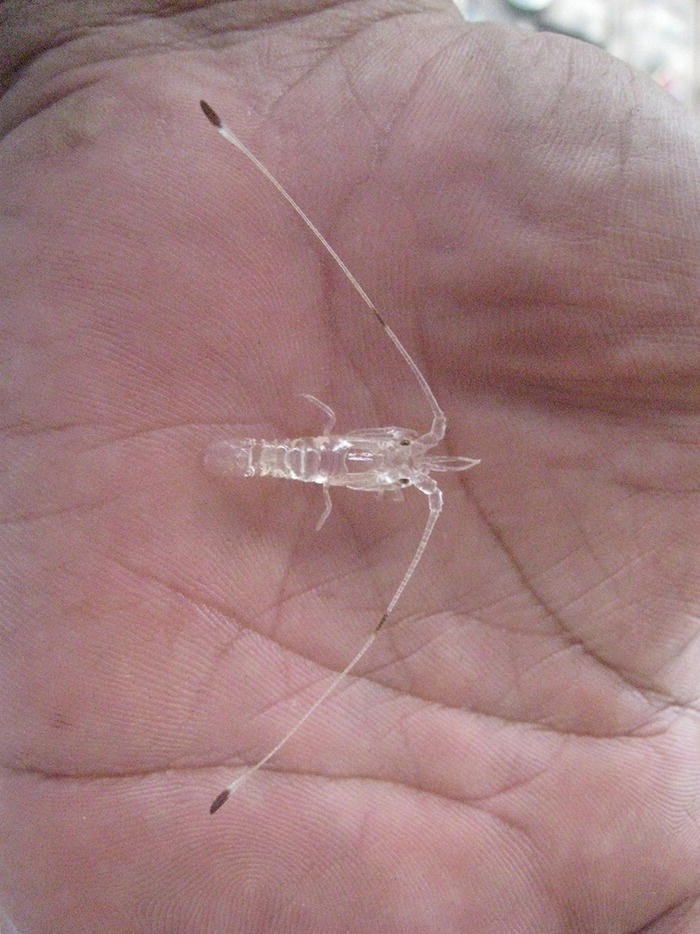

The nature of the phyllosoma larvae, adds further to the problems of culture. The long period of development involves numerous larval stages and corresponding numbers of risky moults as they progressively develop. The phyllosomae are leaf like, transparent, fragile, and difficult to feed. Their long thin appendages beat the water as they swim, and they trap slow‐moving soft and relatively large particles rather haphazardly. The trapped particles are pushed in towards the mouth region where they are masticated and ingested. Artemia nauplii and later stages of Artemia are usually used as the food source in culture, but adequate nutrition is a problem as the larvae progressively die during the latter stages of development. Current research is focused on development of more appropriate foods for phyllosoma larvae, and on culture techniques that reduce the levels of maintenance and risk.

This is an example of where the difference between developing a farmed species in developed and developing countries is very evident.

It is possible to bypass the hatchery phase and collect the post‐larvae in the field. Phyllosoma larvae tend to occur in current systems that bring them back inshore at the end of their long planktonic phase. They are typical of decapod crustaceans with a transitional stage, the puerulus, between the last planktonic phyllosoma stage and the first juvenile instar (Figure 2.10). The puerulus deliberately settles from the plankton onto a suitable substrate for the juvenile stages. In some areas where the currents bring in large numbers of puerulus larvae, it is possible to capture substantial numbers of them.

Figure 2.10 Newly‐settled puerulus larva of Panulirus ornatus, collected from the field.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Dr Clive Jones.

In central provinces of Vietnam, a spiny lobster farming industry is based on:

- puerulus larvae captured in dip nets when they are attracted by lights; and

- recently‐settled juveniles in attraction traps of netting bundles and wood with shelter holes that are suspended in the water column;

There are specialist spiny lobster ‘seed’ collectors who sell the young juveniles to farmers who grow them to commercial size in sea cages. Juvenile and adult spiny lobsters are robust and have been reared in sea cages using trash fish (Figure 2.11). However, as the Vietnam industry has expanded there have been environmental and disease problems arising from this technique and overcrowding. The supply of seed is also a problem, being erratic and declining in many areas.

Figure 2.11 Spiny lobsters, Panulirus ornatus, reared from cage culture at Pemongkong village, East Lombok, Indonesia.

Source: Reproduced with permission from FAO Aquaculture photo library/ I. Christensen.

This activity of trapping puerulus larvae as they settle is feasible at other locations such as within the distribution of Panulirus cygnus in Western Australia. However, the fishers are strongly opposed, seeing this as reducing the subsequent numbers of commercial lobsters.

Research on culturing spiny lobster larvae is being funded with millions of dollars from government and commercial sources. The stakes are high with the prize of success being an extremely valuable aquaculture industry.

2.8.2 Case Study 2: Southern Bluefin Tuna

Like spiny lobsters the farming of Southern bluefin tuna (SBT) (Thunnus maccoyii), through its complete life cycle at a commercial level is one of the ‘Holy Grails’ of aquaculture. The SBT is a very large fish, reaching up to 250 kg (Figures 2.3 and 2.12). It has a world‐wide distribution in the southern oceans between 30–50°S.2 They are adapted for fast swimming. Through a specialised circulatory system, they are able to maintain their core body temperature up to 10°C above the ambient water temperature. This maintains a high metabolic rate of the core swimming muscles, which in turn generate heat to maintain the core temperature. The large warm muscles enable the tuna to swim very fast. This requires a lot of oxygen and they ‘ram’ ventilate, forcing water through the mouth and over the gills. This also requires high food consumption and they are opportunistic feeders, especially on small pelagic fishes.

Figure 2.12 Catching a juvenile Southern bluefin tuna (Thunnus maccoyii). The tuna will be tagged and released. This was part of a program by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO, Australia) to determine the tuna’s areas of distribution and behaviour.

Source: Photograph by CSIRO. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons license, CC BY‐SA 3.0.

This high‐speed predatory fish doesn’t recommend itself as a likely candidate for aquaculture. However, the driving force is the great value of the product. SBT is in high demand for sushi and sashimi, perhaps as the most highly regarded fish for these purposes. The greatest demand for SBT is in Japan and the Tsukiji Market, Tokyo, is the largest wholesale market of SBT (Figure 2.3). The tuna typically sell for USD 20+/kg, price depending on quality and size. This means that a 50 kg fish sells for USD 1000+ and it is difficult to ignore a market where a single fish is worth USD 1000 or more.

With the high value of SBT it was inevitable that there would be commercial fishing, and serious fishing began in the 1950s. It reached a peak in the period 1960–1983 when there were global catches >40 000 t/yr. Catches peaked in 1972 at 55 000 t. Japan was by far the heaviest fisher, taking 46 000 t in 1969. Catches are now regulated to be in the vicinity of 10 000 t/yr. The SBT is now classified as Critically Threatened by the IUCN. By 1994 it was recognised that the SBT was being fished at unsustainable levels and the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT) was formed. Its objective was to ensure, through appropriate management, the conservation and optimum utilisation of the global fishery. A number of countries have joined the CCSBT, including the major fishers Japan and Australia. The total allowable catch for all involved nations combined was 9449 t for the 2010/2011 season. It seems, however, that Japan has probably taken substantially above its quota over the previous 20 years.

This situation invited aquaculture as an alternative to over‐fishing. However, instead of spawning and rearing to marketable size and even closing the life cycle, aquaculture of SBT took the same path as that used for spiny lobster farming in Asia and initial black pearl culture in French Polynesia. Culture of the difficult early stages of these species was bypassed by collecting settling post‐larvae of the spiny lobster (section 2.8.1) and spat from settled larvae for the black‐lip pearl oyster (section 2.8.3). Bypassing the early development stages in SBT was, however, on a much more industrial scale that is appropriately called ‘ranching’. SBT ranching began in 1992 offshore from Port Lincoln, South Australia, and this remains the centre for SBT aquaculture. The industry grew steadily and had a mean production of ca. 7000 t/yr over the period 2010–2014. This represents about USD 128 × 106 /yr (USD 18/kg). SBT ranching developed into the most valuable aquaculture industry in Australia.

Juvenile SBT ca. 15 kg are purse seined on the continental shelf in the Great Australian Bight region from December–April. They are then transferred to specialised circular sea cages with multiple towing lines and internal lines to keep their circular shape. The sea cages are towed very slowly back to the farms at Port Lincoln so that the cages maintain their shape and tuna are not forced against the net and damaged. On reaching the farms the juvenile SBT are transferred from the tow sea cages into 40–50 m diam sea cages on the farms. They need such large sea cages to accommodate their swimming speed. Also, their skin is delicate and can be damaged by collisions with the enclosing netting and with handing.

SBT are problem feeders in the ranching situation. They don’t readily accept either dry or moist pelletised feeds and are fed small pelagic fish, bait fish, such as sardines. Some of the baitfish is imported from overseas, but there is an intense fishery for sardines in southern Australia for tuna feed. There has been research to develop suitable pelletised feeds but, so far, they are uneconomic compared with baitfish. Not only are SBT fed with baitfish, but with their high metabolic rate, they need a lot of food and are fed twice a day. There are apparently no data on their FCR but there are data for the related Northern bluefin tuna (NBT) (Thunnus orientalis) and they are exceedingly poor: FCR for feeding with sardines is 17.8:1 and with sardines and squid is 22.6:1 (Estess et al., 2014). These exceedingly poor FCRs are due to more than 80% of the energy ingested being unavailable for tissue growth. It is expended on maintaining the elevated body temperatures and high metabolic rate.

After 3–8 months the juvenile SBT reach 30–40 kg and are marketed. The fish are gently harvested: they readily bruise, and this reduces their value. Most are for the Japanese market which requires them to be killed and prepared in a specific way. Then they are flash frozen and airfreighted to Tokyo (Figure 2.3).

This form of ranching aquaculture still involves fishing the depleted stock. Furthermore, it is capturing immature fish and diminishing the subsequent spawning population. There is need to go the next step and rear from spawning to commercial size, even to close the life cycle in culture conditions. This has been achieved for the NBT by researchers at Kindai University Aquaculture Research Institute, Osaka, Japan3. They closed the life cycle and by 2007 had the 3rd generation of captive‐cultured fishes. In 2004 they shipped the first batch of captive‐bred fish to market.

An Australian aquaculture company undertook the challenge of spawning and rearing SBT to commercial size. Probably there was the encouragement of the success with NBT in Japan. In 2007, the company treated large wild‐caught broodstock of SBT with hormones to induce gonad maturation and spawning, and obtained the first batch of eggs. The company upgraded their plant to have a special purpose SBT larval rearing recirculation facility. During summer 2009 to2010 there were further successes with induced spawnings. Fingerlings were reared up to 40 days old, but grow‐out of commercial quantities of SBT fingerlings was not successful at that time. The production of SBT juveniles was slower and more difficult than anticipated and a decision was made to defer the project. The company will maintain its broodstock to enable discrete research in the future; however, they do not expect commercial production to be achieved over the short to medium term.

2.8.3 Case Study 3: Cultured ‘Black’ Pearls

The black‐lip pearl oyster, Pinctada margaritifera, has a broad Indo‐Pacific distribution from the Red Sea and east African coasts to Polynesia. There is a long history of fishing for these oysters to supply mother‐of‐pearl, but since the mid‐1970s this species has been used for cultured ‘black’ pearl production in French Polynesia. Cultured ‘black’ or ‘Tahitian’ pearls have an international reputation for their beauty and their range of colours which is unmatched by other species of pearl oyster. Industry development in French Polynesia was based on the collection of juvenile oysters from the wild using ‘spat collectors’ (section 24.4.1). This involves deployment of appropriate substrates (spat collectors) in the ocean to coincide with larval settlement on the collectors. Juvenile oysters that recruit to the collectors (Figure 2.13) can be sold to large farms for pearl production or retained for artisanal pearl production. This activity can be undertaken by local people at low cost and provides a valuable income for remote communities. Because of the socio‐economic benefits offered by pearl farming, the French Polynesia government actively supported expansion of the industry and by 1999 there were more than 2700 leases for pearl farming throughout French Polynesia.

Figure 2.13 Collection of pearl oyster (Pinctada margaritifera) juveniles or ‘spat’ at Namarai, Fiji. Oysters recruit to suspended ropes that are deployedin the sea to coincide with settlement of oyster larvae.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Paul Southgate.

Export of pearls from French Polynesia peaked in the year 2000 at more than 11 t with a value of around USD 200 million and this marked a turning point for the industry. A flood of lower‐grade pearls brought down international prices for Tahitian pearls and market demand declined. The French Polynesian government introduced a series of measures to help stabilise the industry. They included an official classification system, minimum quality standards applied to pearls for export (e.g., nacre thickness and surface quality) and legislation to control pearl production. This intervention had positive impacts with an increase in export values and stabilised production levels. Export values increased to USD 126 million in 2005, from a low of USD 95 million in 2003. Yet despite actions to stabilise the industry, the average export price of a cultured pearl fell from ~ USD 18 to ~ USD 4.5 in the decade to 2015 and average size and average quality were lower than they were a decade before (Ky et al., 2015). As well as quality issues, the industry was severely affected by the global economic downturn that began in 2007/08 which reduced global demand for all luxury goods. The number of pearl farms in French Polynesia has now declined to 487 and the current export value of the industry is ca.USD 73 million (Ky et al., 2015).

Despite a backdrop of over‐production and declining international demand for cultured pearls from French Polynesia, Fiji entered the cultured pearl industry in the year 2000 (Figure 2.14) Benefiting from the lessons learned in French Polynesia, Fijian cultured pearl production focuses on relatively low production volumes and export of the highest quality pearls. It also developed a marketing strategy promoting the unique pearl colours produced in Fiji which differ from those of Tahitian pearls and are not available from any other source. Fijian cultured pearls quickly gained an international reputation for their quality and colour range (Figure 2.15) and supply is unable to meet international demand. The Fijian government actively supports expansion of pearl culture throughout Fiji and, with appropriate consideration of quality control and marketing, continued growth of the Fijian cultured pearl industry is likely.

Figure 2.14 Pearl oysters (Pinctada margaritifera) cultured on ‘chaplets’ (tied to ropes) suspended from a longline in Savusavu Bay, Fiji.

Source: Reproduced with permission from C. M. Prevost, Civa Pearls, Fiji.

Figure 2.15 Cultured pearls from Fiji generate strong market demand because of their high quality and unique colour range.

Source: Reproduced with permission from C.M. Prevost, Civa Pearls, Fiji.

The cultured ‘black’ pearl industry produces luxury items of high value that, in normal times, find a ready market. However, the experiences of the French Polynesian cultured pearl industry illustrate the importance of control over both production volume and product quality. Unrestrained production and poor quality‐control resulted in a major devaluing of the product, reduction in the number of farms and in industry production. The industry was also affected by loss of reputation which is a key component of successful marketing of luxury products. Reduced demand for cultured pearls as a result of the global economic crisis also illustrates the potential impacts of external influences on the economic viability of aquaculture ventures. Yet despite these factors, pearl culture in Fiji has developed successfully based on the experiences of the French Polynesian industry, and through production of a ‘rare’ and unique product targeting a niche market. These factors have supported continued industry expansion in Fiji over recent years.

Cultured pearl industries in the Pacific have developed on the basis of wild spat collection, which, like the spiny lobster example above, allows the technically demanding hatchery phase to be bypassed. The simple methods required for spat collection allow local people to enter the industry at a number of levels. They can generate income through sales of collected spat, retain spat for subsequent sales of mother‐of‐pearl (oyster shells) or shell handicrafts, or retain oyster for pearl production. These factors have supported expansion of cultured ‘black’ pearl production from French Polynesia to a number of other Pacific island countries. This development is enthusiastically supported at government level because as well as potential export income from pearl sales, there can be considerable socio‐economic benefits to remote coastal communities.

2.9 Summary

- Intensity of aquaculture ranges from natural ecosystems in ponds, yielding 0.009 kg/m2, to intense recirculating systems that are highly regulated and yield 6 kg/m2. Culture intensity, i.e., extensive, semi‐intensive and intensive, is reflected in the level of inputs that are required to maintain adequate growth of the cultured organisms.

- Extensive and semi‐intensive aquaculture are more characteristic of developing countries. The demand in developed countries is for carnivorous species that are farmed in intensive conditions with high protein feeds.

- Other forms of aquaculture are polyculture, where complementary species are cultured together in ponds to increase productivity, and agri‐aquaculture, where cultured species are grown within wet crops or in ponds that receive farm wastes. These are typical of traditional aquaculture.

- The degree of water exchange through the farm is another variable. They may be static, e.g., ponds; or open, e.g., fish cages in the ocean; or semi‐open, e.g., tanks with water flowing through them.

- Selecting a new species to develop for aquaculture is a complex process, especially in developed countries. Economics, e.g., demand and profitability, the animal’s biology and appropriate farm sites must be considered. Appropriate aspects of biology are needed in the selected species, including hardiness, ability to tolerate crowded conditions, variations in water quality and handling.

- Establishing new farms for a commonly farmed species may be straightforward in developing countries. However, bringing a new species to the point of profitable commercial farming in developed countries is complex and requires a series of developmental stages. The duration of the development period may cause the venture to fail as the company involved has insufficient capital to sustain the venture until it is profitable.

- Three case studies of aquaculture developments are presented: black pearl farming in Polynesia, rock lobster farming in Vietnam and Southern bluefin tuna in South Australia. None of these show the full pattern of developing the aquaculture of a new species. They found ways to by‐pass the early developmental stages which are the difficult part of the life cycle. An attempt to rear Southern bluefin tuna from spawning was abandoned when it became clear that reaching commercial production by this technique would take a long time.

References

- Avault, J.W. Jr (1996). Fundamentals of Aquaculture: A Step‐by‐Step Guide to Commercial Aquaculture. AVA Publishing Co., Baton Rouge, LA.

- Boyd, C.E. (1991). Water Quality in Ponds for Aquaculture. Auburn University, Alabama.

- Castine, S.A., McKinnon, D.A., Paul, N.A. et al. (2013). Wastewater treatment for land‐based aquaculture: improvements and value adding alternatives in model systems in Australia. Aquaculture Environment Interactions, 4, 285–300.

- Cohen, D. (1997). Integration of aquaculture and irrigation: rationale, principles and its practice in Israel. International Water and Irrigation Review, 17, 8–18.

- Edwards, P. (1998). A system approach for the promotion of integrated aquaculture. Aquaculture Economics and Management, 2, 1–12.

- Estess, E.E., Coffey, D.M., Shimose, T, et al. (2014). Bioenergetics of captive Pacific bluefin tuna (Thunnus orientalis). Aquaculture, 434, 137–144.

- Ky, C.L., Nakasai, S., Molinari, N, et al. (2015). Influence of grafter skill and season on cultured pearl shape, circles and rejects in Pinctada margaritifera aquaculture in Mangareva lagoon. Aquaculture,435, 361–370.

- Losordo, T.M. (1998a). Recirculating aquaculture production systems: the status and future. Aquaculture Magazine, 24(1), 38–45.

- Losordo, T.M. (1998b). Recirculating aquaculture production systems: the status and future, part II. Aquaculture Magazine, 24(2), 45–53.

- Losordo, T.M., Masser, M.P. and Rakocy, J. (2001). Recirculating aquaculture tank production systems. An overview of critical considerations. World Aquaculture, 32(1), 18–22.

- Palmer, P.J. (2010). Polychaete‐assisted sand filters. Aquaculture, 306, 369–377.

- Yoo, K.H. and Boyd, C.E. (1994). Hydrology and Water Supply for Pond Aquaculture. Chapman and Hall, New York.