Directory

CONTENTS

Accommodation

Activities

Business Hours

Children

Climate Charts

Courses

Customs

Dangers & Annoyances

Embassies & Consulates

Food

Gay & Lesbian Travelers

Holidays

Insurance

Internet Access

Legal Matters

Maps

Money

Post

Shopping

Telephone

Time

Toilets

Tourist Information

Travelers with Disabilities

Visas & Tourist Cards

Volunteering

Women Travelers

ACCOMMODATION

Cuban accommodation runs the gamut from CUC$10 beach cabins to five-star resorts. Solo travelers are penalized price-wise, paying 75% of the price of a double room.

In this book, budget means anything under CUC$40 for two people. In this range, casas particulares are almost always better value than a hotel. Only the most deluxe casas particulares in Havana will be anything over CUC$35, where you’re assured quality amenities and attention. In cheaper casas particulares (CUC$15), you may have to share a bath and will have a fan instead of air-con. In the rock-bottom places (campismos, mostly), you’ll be lucky if there are sheets and running water, though there are usually private baths. If you’re staying in a place intended for Cubans, you’ll compromise materially, but the memories are guaranteed to be platinum.

The midrange category (from CUC$40 to CUC$80) is a lottery, with some stylish colonial hotels and some awful places. In midrange hotels, you can expect air-con, private hot-water bath, clean linens, satellite TV, a restaurant and a swimming pool – although the architecture’s often uninspiring and the food not exactly gourmet.

Unsurprisingly, the most comfortable top-end hotels cost CUC$80 and up for two people. These are usually partly foreign-owned and maintain international standards (although service can sometimes be a bit lax). Rooms have everything that a midrange hotel has, plus big, quality beds and linens; a minibar; international phone service; and perhaps a terrace or view. Havana has some real gems.

Factors influencing rates are time of year, location and hotel chain (in this book the chain is listed after the hotel to give you an idea of what standard and services to expect). Low season is generally mid-September to early December and February to May (except for Easter week). Christmas and New Year is what’s called extreme high season, when rates are 25% more than high-season rates. Bargaining is sometimes possible in casas particulares – though as far as foreigners go, it’s not really the done thing. The casa owners in any given area pay generic taxes and the prices you will be quoted reflect this. You’ll find very few casas in Cuba that aren’t priced between CUC$15 to CUC$35, unless you’re up for a long stay. Prearranging Cuban accommodation has become easier now that more Cubans (unofficially) have access to the internet.

The following chains and internet agencies offer online booking and/or information:

- Casa Particular Organization (www.casaparticularcuba.org) Reader-recommended for prebooking private rooms.

- Cubacasas (www.cubacasas.net) The best online source for casa particular information and booking; up to date, accurate and with colorful links to hundreds of private rooms across the island (in English and French).

- Cubalinda.com (www.cubalinda.com) Havana-based, so it knows its business.

- Gran Caribe (www.grancaribe.cu)

- Islazul (www.islazul.cu)

- Sol Meliá (www.solmeliacuba.com) Also offers discounts.

- Vacacionar (www.dtcuba.com) Official site of Directorio Turístico de Cuba.

Campismos

Campismos are where Cubans go on vacation. There are more than 80 of them sprinkled throughout the country and they are wildly popular (an estimated one million Cubans use them annually). Hardly ‘camping,’ most of these installations are simple concrete cabins with bunk beds, foam mattresses and cold showers. Campismos are the best place to meet Cubans, make friends and party in a natural setting.

Campismos are ranked either nacional or internacional. The former are (technically) only for Cubans, while the latter host both Cubans and foreigners and are more upscale, with air-con and/or linens. There are currently a dozen international campismos in Cuba ranging from the hotel-standard Aguas Claras (Pinar del Río) to the more basic Puerto Rico Libre (Holguín). In practice, campismo staff may rent out a nacional cabin (or tent space) to a foreigner pending availability, but it depends on the installation, and many foreigners are turned away (not helpful when you’ve traveled to a way-out place on the pretext of getting in). To avoid this situation, we’ve listed only international campismos in this book.

For a full list of all the country’s campismos (both nacional and internacional), you can pick up an excellent Guía de Campismo (CUC$2.50) from any of the Reservaciones de Campismo offices.

As far as international campismos go, contact the excellent Cubamar ( 7-833-2523/4; www.cubamarviajes.cu; Calle 3 btwn Calle 12 & Malecón, Vedado;

7-833-2523/4; www.cubamarviajes.cu; Calle 3 btwn Calle 12 & Malecón, Vedado;  8:30am-5pm Mon-Sat) in Havana for reservations. If you’re adamant to try winging it in a campismo nacional, try the provincial Campismo Popular office to make a reservation closer to the installation proper (some office addresses can be found in the relevant regional chapters). Cabin accommodation in international campismos costs from CUC$10 to CUC$20 per bed. Prices at the plush cabins of Villas Aguas Claras (Pinar del Río province; Click here) and Guajimico (Cienfuegos province; Click here) are higher.

8:30am-5pm Mon-Sat) in Havana for reservations. If you’re adamant to try winging it in a campismo nacional, try the provincial Campismo Popular office to make a reservation closer to the installation proper (some office addresses can be found in the relevant regional chapters). Cabin accommodation in international campismos costs from CUC$10 to CUC$20 per bed. Prices at the plush cabins of Villas Aguas Claras (Pinar del Río province; Click here) and Guajimico (Cienfuegos province; Click here) are higher.

Cubamar also rents mobile homes (campervans) called autocaravanas, which sleep four adults and two children. Prices are around CUC$165 per day (but vary according to type, season and number of days required) including insurance (plus CUC$400 refundable deposit). You can park these campers wherever it’s legal to park a regular car. There are 21 campismos or hotels that have Campertour facilities giving you access to electricity and water. These are a great alternative for families.

Renegade cyclists aside, few tourists tent camp in Cuba. Yet, the abundance of beaches, plus the helpfulness and generosity of Cubans make camping surprisingly easy and rewarding. Beach camping means insanely aggressive jejenes (sand fleas) and mosquitoes. The repellent sold locally just acts as a marinade for your flesh, so bring something strong – DEET-based if you’re down with chemicals. Camping supplies per se don’t exist; bring your own or improvise.

Casas Particulares

Private rooms are the best option for independent travelers in Cuba and a great way of meeting the locals on their home turf. Furthermore, staying in these venerable, family-orientated establishments will give you a far more open and less censored view of the country with its guard down, and your understanding (and appreciation) of Cuba will grow far richer as a result. Casa owners also often make excellent tour guides.

You’ll know houses renting rooms by the blue insignia on the door marked ‘Arrendador Divisa.’ There are thousands of casas particulares all over Cuba; 3000 in Havana alone and nearly 400 in Trinidad. From penthouses to historical homes, all manner of rooms are available from CUC$15 to CUC$35. Although some houses will treat you like a business paycheck, the vast majority of casa owners are warm, open and impeccable hosts.

Government regulation of casas is intense and it’s illegal to rent out private rooms in resort areas. Owners pay CUC$100 to CUC$250 per room per month depending on location; plus extra for off-street parking, to post a sign advertising their rooms and to serve meals. These taxes must be paid whether the rooms are rented or not. Owners must keep a register of all guests and report each new arrival within 24 hours. For these reasons, you will find it hard to bargain for rooms. You will also be requested to produce your passport (not a photocopy). Penalties are high for infractions, and updated regulations in 2004 restricted casas to two people (excluding minors under 17) per room and only two rooms per house. Regular government inspections ensure that conditions inside casas remain clean, safe and secure. Most proprietors offer breakfast and dinner for an extra rate. Hot showers are a prerequisite. In general, rooms these days provide at least two beds (one is usually a double), a fridge, air-con, a fan and private bath. Bonuses could include a terrace or patio, private entrance, TV, security box, kitchenette and parking space.

Due to the plethora of casas particulares in Cuba, it has been impossible to include even a fraction of the total in this book. The ones chosen are a combination of reader recommendations and local research. If one casa is full, they’ll almost always be able to recommend you to someone else down the road.

Hotels

All tourist hotels and resorts are at least 51% owned by the Cuban government and are administered by one of five main organizations. Islazul is the cheapest and most popular with Cubans (who pay in Cuban pesos). Although the facilities can be variable at these establishments and the architecture a tad Sovietesque, Islazul hotels are invariably clean, cheap, friendly and, above all, Cuban. They’re also more likely to be situated in the island’s smaller provincial towns. One downside is the blaring on-site discos that often keep guests awake until the small hours. Cubanacán is a step up and offers a nice mix of budget and midrange options in both cities and resort areas. The company has recently developed a new clutch of affordable boutique-style hotels (the Encanto brand) in attractive city centers such as Sancti Spíritus, Baracoa, Remedios and Santiago. Gaviota manages higher-end resorts including glittering 933-room Playa Pesquero, though the chain also has a smattering of cheaper ‘villas’ in places such as Santiago and Cayo Coco. Gran Caribe does midrange to top-end hotels, including many of the all-inclusives in Havana and Varadero. Lastly, Habaguanex is based solely in Havana and manages most of the fastidiously restored historic hotels in Habana Vieja. The profits from these ventures go toward restoring the Unesco World Heritage Site. Because each group has its own niche, throughout this book we mention the chain to which a hotel belongs to give you some idea of what to expect at that particular installation. Except for Islazul properties, tourist hotels are for guests paying in Convertibles only. Since May 2008 Cubans have been allowed to stay in any tourist hotels although financially most of them are still out of reach.

At the top end of the hotel chain you’ll often find foreign chains such as Sol Meliá and Superclubs running hotels in tandem with Cubanacán, Gaviota or Gran Caribe – mainly in the resort areas. The standards and service at these types of places are not unlike resorts in Mexico and the rest of the Caribbean.

Return to beginning of chapter

ACTIVITIES

Cuba offers a wealth of exciting outdoor activities. For a full rundown, see the Outdoors chapter, Click here.

Return to beginning of chapter

BUSINESS HOURS

Cuban business hours are hardly etched in stone, but offices are generally open from 9am to 5pm Monday to Friday. Cubans don’t take a siesta like people in other Latin American countries, so places normally don’t close at midday. Museums and agropecuarios (vegetable markets) are usually closed Monday.

Post offices are open from 8am to 6pm Monday to Saturday, with some main post offices keeping later hours. Banks are usually open from 9am to 3pm weekdays, closing at noon on the last working day of each month. Cadeca exchange offices are generally open from 9am to 6pm Monday to Saturday, and from 9am to noon Sunday.

Pharmacies are generally open from 8am to 8pm, but those marked turno permanente or pilotos are open 24 hours.

In retail outlets everything grinds to a halt during the cambio de turno (shift change) and you won’t be able to order a beer or buy cigarettes until they’re done doing inventory (which can take anywhere from 10 minutes to one hour). Shops are usually closed after noon on Sunday.

Throughout this book, any exceptions to these hours are given in specific listings.

Return to beginning of chapter

CHILDREN

Children are encouraged to talk, sing, dance, think, dream and play, and are integrated into all parts of society: you’ll see them at concerts, restaurants, church, political rallies (giving speeches even!) and parties. Travelers with children will find this embracing attitude heaped upon them, too.

In Cuba there are many travelers with kids, especially Cuban-Americans visiting family with their children; these will be your best sources for on-the-ground information. One aspect of the local culture that parents may find foreign (aside from the material shortages) is the physical contact and human warmth that is so typically Cuban: strangers ruffle kids’ hair, give them kisses or take their hands with regularity. For more general advice, see Lonely Planet’s Travel with Children.

Practicalities

Many simple things aren’t available in Cuba or are hard to find, including baby formula, diaper wipes, disposable diapers, crayons, any medicine, clothing, sunblock etc. On the upside, Cubans are very resourceful and will happily whip up some squash-and-bean baby food or fashion a cloth diaper. In restaurants, there are no high chairs because Cubans cleverly turn one chair around and stack it on another, providing a balanced chair at the right height. Cribs are available in the fancier hotels and resorts, and in casas particulares one will be found. Good baby-sitting abounds: your hotel concierge or casa owner can connect you with good child care. What you won’t find are car seats (or even seat belts in some cases), so bring your own from home.

The key to traveling in Cuba is simply to ask for what you need and some kind person will help you out.

Sights & Activities

Like any great city, Havana has plenty for kids (Click here). It has kids’ theater and cinema, two aquariums, two zoos, a couple of great parks and the massive new Isla del Coco amusement park. Resorts are packed with kids’ programs, from special outings to designated kiddy pools. Guardalavaca has the added advantage of being near many other interesting sights such as the aquarium at Bahía de Naranjo. Parque Baconao in Santiago de Cuba Click here has everything from old cars to dinosaur sculptures and is a fantasy land for kids of all ages.

Other activities kids will love include horseback riding, baseball games, cigar-factory tours, snorkeling, miniature golf, exploring caves, and the waterfalls at El Nicho and Topes de Collantes.

Return to beginning of chapter

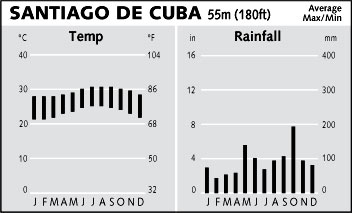

CLIMATE CHARTS

Cuba is hot, with humidity ranging from 81% in summer to 79% in winter. Luckily the heat is nicely moderated by the gentle Northeast Tradewinds and the highest temperature ever recorded on the island was less than 40°C. Beware of cold fronts passing in the winter when evenings can be cool in the west of the island. Cuba’s hurricane season (June to November) should also be considered when planning; see also When to Go.

Return to beginning of chapter

COURSES

Cuba’s rich cultural tradition and the abundance of highly talented, trained professionals make it a great place to study. Officially matriculating students are afforded longer visas and issued a carnet – the identification document that allows foreigners to pay for museums, transport (including colectivos – collective taxis) and theater performances in pesos. Technological and linguistic glitches, plus general unresponsiveness, make it hard to set up courses before arriving, but you can arrange everything once you arrive. In Cuba, things are always better done face to face.

Private one-on-one lessons are available in everything from batá drumming to advanced Spanish grammar. Classes are easily arranged, typically for CUC$5 to CUC$10 an hour at the institutions specializing in your area of interest. Other travelers are a great source of up-to-date information in this regard. See also individual chapters for details on specific courses.

While US citizens can still study in Cuba, their options shrank dramatically when the Bush administration discontinued people-to-people (educational) travel licenses in 2003.

Language

The largest organization offering study visits for foreigners is UniversiTUR SA ( 7-261-4939, 7-55-55-77; agencia@universitur.com; Calle 30 No 768-1 btwn Calle 41 & Av Kohly, Nuevo Vedado, Havana). UniversiTUR arranges regular study and working holidays at any of Cuba’s universities and at many higher education or research institutes. Its most popular programs are intensive courses in Spanish language and Cuban culture at Universidad de La Habana. UniversiTUR has 17 branch offices at various universities throughout Cuba, all providing the same services, though prices vary. While US students can study anywhere in the country, they must arrange study programs for the provinces (except Havana or Matanzas) through Havanatur (Click here).

7-261-4939, 7-55-55-77; agencia@universitur.com; Calle 30 No 768-1 btwn Calle 41 & Av Kohly, Nuevo Vedado, Havana). UniversiTUR arranges regular study and working holidays at any of Cuba’s universities and at many higher education or research institutes. Its most popular programs are intensive courses in Spanish language and Cuban culture at Universidad de La Habana. UniversiTUR has 17 branch offices at various universities throughout Cuba, all providing the same services, though prices vary. While US students can study anywhere in the country, they must arrange study programs for the provinces (except Havana or Matanzas) through Havanatur (Click here).

Students heading to Cuba should bring a good bilingual dictionary and a basic ‘learn Spanish’ textbook, as such books are scarce or expensive in Cuba. You might sign up for a two-week course at a university to get your feet wet and then jump into private classes once you’ve made some contacts.

Culture & Dance

Dance classes are available all over Cuba, although Havana and Santiago are your best bets. Institutions to try include the Casa del Caribe (Map;  22-64-22-85; Calle 13 No 154, Vista Alegre, 90100 Santiago de Cuba), the Conjunto Folklórico Nacional (Map;

22-64-22-85; Calle 13 No 154, Vista Alegre, 90100 Santiago de Cuba), the Conjunto Folklórico Nacional (Map;  7-830-3060; Calle 4 No 103, btwn Calzada & Calle 5, Vedado, Havana) and the Centro Andaluz (Map;

7-830-3060; Calle 4 No 103, btwn Calzada & Calle 5, Vedado, Havana) and the Centro Andaluz (Map;  7-863-6745; fax 7-66-69-01; Paseo de Martí No 104 btwn Genios & Refugio, Centro Habana). See the individual chapters for details.

7-863-6745; fax 7-66-69-01; Paseo de Martí No 104 btwn Genios & Refugio, Centro Habana). See the individual chapters for details.

Art & Film

Courses for foreigners can be arranged throughout the year by the Oficina de Relaciones Internacionales of the Instituto Superior de Arte (Map;  7-208-0017; isa@cubarte.cult.cu, www.isa.cult.cu; Calle 120 No 1110, Cubanacán, Playa, Havana 11600). Courses in percussion and dance are available almost anytime, but other subjects, such as the visual arts, music, theater and aesthetics, are offered when professors are available.

7-208-0017; isa@cubarte.cult.cu, www.isa.cult.cu; Calle 120 No 1110, Cubanacán, Playa, Havana 11600). Courses in percussion and dance are available almost anytime, but other subjects, such as the visual arts, music, theater and aesthetics, are offered when professors are available.

Courses usually involve four hours of classes a week and cost between CUC$10 and CUC$15 per hour. Prospective students must apply in the last week of August for the fall semester or the last three weeks of January for spring. The school is closed for holidays throughout July and until the third week in August. The institute also accepts graduate students for its regular winter courses, and an entire year of study here (beginning in September) as part of the regular five-year program costs CUC$2500. Accommodation in student dormitories can be arranged.

The Escuela Internacional de Cine, Televisión y Video ( 47-38-22-46, 47-38-23-68; Apartado Aéreo 4041, San Antonio de los Baños, Provincia de La Habana) educates broadcasting professionals from all over the world (especially developing countries). Under the patronage of novelist Gabriel García Márquez, it’s run by the foundation that also organizes the annual film festival in Havana. The campus is at Finca San Tranquilino, Carretera de Vereda Nueva, 5km northwest of San Antonio de los Baños. Prospective filmmaking students should apply in writing in advance (personal inquiries at the gate are not welcome).

47-38-22-46, 47-38-23-68; Apartado Aéreo 4041, San Antonio de los Baños, Provincia de La Habana) educates broadcasting professionals from all over the world (especially developing countries). Under the patronage of novelist Gabriel García Márquez, it’s run by the foundation that also organizes the annual film festival in Havana. The campus is at Finca San Tranquilino, Carretera de Vereda Nueva, 5km northwest of San Antonio de los Baños. Prospective filmmaking students should apply in writing in advance (personal inquiries at the gate are not welcome).

Return to beginning of chapter

CUSTOMS

Cuban customs regulations are complicated. For the full scoop see www.aduana.co.cu. Travelers are allowed to bring in personal belongings (including photography equipment, binoculars, musical instrument, tape recorder, radio, personal computer, tent, fishing rod, bicycle, canoe and other sporting gear), and gifts up to CUC$50.

Items that do not fit into the categories mentioned above are subject to a 100% customs duty to a maximum of CUC$1000.

Items prohibited entry into Cuba include narcotics, explosives, pornography, electrical appliances broadly defined, global positioning systems, prerecorded video cassettes and ‘any item attempting against the security and internal order of the country,’ including some books. Canned, processed and dried food are no problem, nor are pets.

Exporting undocumented art and items of cultural patrimony is restricted and involves fees. If you didn’t get an official certificate at point of sale, you’ll need to obtain one from the Registro Nacional de Bienes Culturales (Map; Calle 17 No 1009 btwn Calles 10 & 12, Vedado, Havana;  9am-noon Mon-Fri). Bring the objects here for inspection; fill in a form; pay a fee of between CUC$10 and CUC$30, which covers from one to five pieces of artwork; and return 24 hours later to pick up the certificate.

9am-noon Mon-Fri). Bring the objects here for inspection; fill in a form; pay a fee of between CUC$10 and CUC$30, which covers from one to five pieces of artwork; and return 24 hours later to pick up the certificate.

You are allowed to export 50 boxed cigars duty-free (or 23 singles), US$5000 (or equivalent) in cash and only CUC$200.

Return to beginning of chapter

DANGERS & ANNOYANCES

Cuba is generally safer than most countries, and violent attacks are extremely rare. Petty theft (eg rifled luggage in hotel rooms or unattended shoes disappearing from the beach) is common, but preventative measures work wonders. Pickpocketing is preventable: wear your bag in front of you on crowded buses and at busy markets, and only take what money you’ll need to the disco.

Begging is more widespread and is exacerbated by tourists who amuse themselves by handing out money, soap, pens, chewing gum and other things to people on the street. Sadly, it seems that some Cubans have dropped out of productive jobs because they’ve found it is more lucrative to hustle tourists or beg than to work. It’s painful for everyone when beggars earn more money than doctors. If you truly want to do something to help, pharmacies and hospitals will accept medicine donations, schools happily take pens, paper, crayons etc, and libraries will gratefully accept books. Alternatively pass stuff onto to your casa particular owner. Hustlers are called jineteros/jineteras (male/female touts), and can be a real nuisance.

If you’re sensitive to smoke, you’ll choke in Cuba, and despite government laws supposedly banning smoking in public places, people appear to light wherever and whenever they like.

Despite the many strides Cuba has made since the Revolution in stamping out racial discrimination, traces still linger and visitors of non-European origin are more likely to attract the attention of the police than those that look obviously non-Cuban. Latin, South Asian or black visitors may have to show passports to enter hotels and other places from which ordinary Cubans are barred (under the pretext that they think you’re Cuban). Likewise, racially mixed pairs (especially black-white couples) will usually encounter more questions, demanding of papers and hassle than other travelers.

Return to beginning of chapter

EMBASSIES & CONSULATES

Most embassies are open from 8am to noon on weekdays.

- Australia See Canada.

- Austria (Map;

7-204-2825; Calle 4 No 101, Miramar, Havana)

7-204-2825; Calle 4 No 101, Miramar, Havana) - Canada Havana (Map;

7-204-2517; Calle 30 No 518, Playa); Varadero (Map;

7-204-2517; Calle 30 No 518, Playa); Varadero (Map;  45-61-20-78; Calle 13 No 422 btwn Av 1 & Camino del Mar) Also represents Australia.

45-61-20-78; Calle 13 No 422 btwn Av 1 & Camino del Mar) Also represents Australia. - Denmark (Map;

7-33-81-28; 4th fl, Paseo de Martí No 20, Centro Habana, Havana)

7-33-81-28; 4th fl, Paseo de Martí No 20, Centro Habana, Havana) - France (Map;

7-204-2308; Calle 14 No 312 btwn Avs 3 & 5, Miramar, Havana)

7-204-2308; Calle 14 No 312 btwn Avs 3 & 5, Miramar, Havana) - Germany (Map;

7-833-2539; Calle 13 No 652, Vedado, Havana)

7-833-2539; Calle 13 No 652, Vedado, Havana) - Italy (Map;

7-204-5615; Av 5 No 402, Miramar, Havana)

7-204-5615; Av 5 No 402, Miramar, Havana) - Japan (Map;

7-204-3508; Miramar Trade Center, cnr Av 3 & Calle 80, Playa, Havana)

7-204-3508; Miramar Trade Center, cnr Av 3 & Calle 80, Playa, Havana) - Mexico (Map;

7-204-7722; Calle 12 No 518, Miramar, Havana)

7-204-7722; Calle 12 No 518, Miramar, Havana) - Netherlands (Map;

7-204-2511; Calle 8 No 307 btwn Avs 3 & 5, Miramar, Havana)

7-204-2511; Calle 8 No 307 btwn Avs 3 & 5, Miramar, Havana) - New Zealand See UK.

- Russia (Map; Av 5 No 6402 btwn Calles 62 & 66, Playa, Havana)

- Spain (Map;

7-866-8029; Cárcel No 51, Centro Habana, Havana)

7-866-8029; Cárcel No 51, Centro Habana, Havana) - Sweden (Map;

7-204-2831; fax 7-204-1194; Calle 34 No 510, Miramar, Havana)

7-204-2831; fax 7-204-1194; Calle 34 No 510, Miramar, Havana) - Switzerland (Map;

7-204-2611; Av 5 No 2005, btwn Avs 20 & 22, Miramar, Havana)

7-204-2611; Av 5 No 2005, btwn Avs 20 & 22, Miramar, Havana) - UK (Map;

7-204-1771; Calle 34 No 708, Miramar, Havana) Also represents New Zealand.

7-204-1771; Calle 34 No 708, Miramar, Havana) Also represents New Zealand. - USA (Map;

7-833-3026; US Interests Section, Calzada btwn Calles L & M, Vedado, Havana)

7-833-3026; US Interests Section, Calzada btwn Calles L & M, Vedado, Havana)

Return to beginning of chapter

FOOD

It will be a very rare meal in Cuba that costs over CUC$25. In this book, restaurant listings are presented in the following order: budget (meals for under CUC$5), midrange (meals for CUC$5 to CUC$10) and top end (meals for over CUC$10). Restaurant are generally open from 11am to 11pm daily. Before you dig in, check out the detailed information in the Food & Drink chapter.

Return to beginning of chapter

GAY & LESBIAN TRAVELERS

While Cuba can’t be called a queer destination (yet), it’s more tolerant than many other Latin American countries. The hit movie Fresa y Chocolate (Strawberry and Chocolate, 1994) sparked a national dialogue about homosexuality, and Cuba is pretty tolerant, all things considered. People from more accepting societies may find this tolerance too ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ or tokenistic (everybody has a gay friend/relative/coworker, whom they’ll mention when the topic arises), but what the hell, you have to start somewhere and Cuba is moving in the right direction.

Machismo shows an ugly face when it comes to lesbians and female homosexuality has not enjoyed the aperture of male homosexuality. For this reason, female lovers can share rooms and otherwise ‘pass’ with facility. However Jurassic you might find that, it’s a workable solution to a sticky problem. There are occasional fiestas para chicas (not necessarily all-girl parties, but close); ask around at the Cine Yara (Map;  7-832-9430; cnr Calles 23 & L, Vedado, Havana).

7-832-9430; cnr Calles 23 & L, Vedado, Havana).

Cubans are physical with each other and you’ll see men hugging, women holding hands and lots of friendly caressing. This type of casual touching shouldn’t be a problem, but take care when that hug among friends turns overtly sensual in public.

See also boxed text.

Return to beginning of chapter

HOLIDAYS

The Cuban calendar is loaded with holidays, but there are only a few that might affect your travel plans; among them are December 25 (not declared an official holiday until after the Pope visited in 1998), January 1, May 1 and July 26. On these days, stores will be closed and transport (except for planes) erratic. On May 1, especially, buses are dedicated to shuttling people to the Plaza de la Revolución in every major city and town and you can just forget about getting inner-city transport.

July and August mean crowded beaches and sold-out campismos and hotels.

Return to beginning of chapter

INSURANCE

Insurance pays off only if something serious happens, but that’s what insurance is for, so you’d be foolish to travel without cover. Outpatient treatment at international clinics designed for foreigners is reasonably priced, but emergency and prolonged hospitalization get expensive (the free medical system for Cubans should only be used when there is no other option).

If you’re really concerned about your health, consider purchasing travel insurance once you arrive at Asistur (Map;  7-866-4499, alarm 7-866-8527; www.asistur.cu; Paseo de Martí No 208, Centro Havana, Havana). It has two types of coverage. For non-Americans the policy costs CUC$2.50 per day and covers up to CUC$400 in lost luggage, CUC$7000 in medical expenses and CUC$5000 each for repatriation of remains or jail bail. For Americans, similar coverage costs CUC$8 per day and provides up to CUC$25,000 in health-care costs, plus CUC$7000 to repatriate remains or evacuate you. See also Click here.

7-866-4499, alarm 7-866-8527; www.asistur.cu; Paseo de Martí No 208, Centro Havana, Havana). It has two types of coverage. For non-Americans the policy costs CUC$2.50 per day and covers up to CUC$400 in lost luggage, CUC$7000 in medical expenses and CUC$5000 each for repatriation of remains or jail bail. For Americans, similar coverage costs CUC$8 per day and provides up to CUC$25,000 in health-care costs, plus CUC$7000 to repatriate remains or evacuate you. See also Click here.

It’s strongly recommended that you take car insurance for a variety of reasons; Click here for details.

Worldwide travel insurance is available at www.lonelyplanet.com/travel_services.

Return to beginning of chapter

INTERNET ACCESS

With state-run telecommunications company Etecsa re-establishing its monopoly as service providers, internet access is available all over the country in Etecsa’s spanking new telepuntos. You’ll find one of its swish, airconditioned sales offices in almost every provincial town and it is your best point of call for fast and reliable internet access. The drill is to buy a one-hour user card (CUC$6) with scratch-off usuario (code) and contraseña (password) and help yourself to an available computer. These cards are interchangeable in any telepunto across the country so you don’t have to use up your whole hour in one go.

The downside of the Etecsa monopoly is that there are few, if any, independent internet cafes outside of the telepuntos and many of the smaller hotels – unable to afford the service fee – have had to dispense of their computers. As a general rule, most four- and five-star hotels (and all resort hotels) will have their own internet cafes although the fees here are often higher (sometimes as much as CUC$12 per hour).

As internet access for Cubans is restricted (they’re only allowed internet under supervision, eg in educational programs or if their job deems it necessary), you may be asked to show your passport when using a telepunto (although if you look obviously foreign, they won’t bother). On the plus side, the Etecsa places are open long hours and not often that crowded.

See also Getting Started, for a list of useful internet resources on Cuba.

Return to beginning of chapter

LEGAL MATTERS

Cuban police are everywhere and they’re usually very friendly – more likely to ask you for a date than a bribe. Corruption is a serious offense in Cuba and typically no one wants to get messed up in it. Getting caught out without identification is never good; carry some around just in case (a driver’s license, a copy of your passport or student ID card should be sufficient).

Drugs are prohibited in Cuba though you may still get offered marijuana and cocaine on the streets of Havana. Penalties for buying, selling, holding or taking drugs are serious, and Cuba is making a concerted effort to treat demand and curtail supply; it is only the foolish traveler who partakes while on a Cuban vacation.

Return to beginning of chapter

MAPS

Signage is awful in Cuba so a good map is essential for drivers and cyclists alike. The comprehensive Guía de Carreteras (CUC$6), published in Italy, includes the best maps available in Cuba. It has a complete index, a detailed Havana map and useful information in English, Spanish, Italian and French. Handier is the all-purpose Automapa Nacional, available at hotel shops and car-rental offices.

The best map published outside Cuba is the Freytag & Berndt 1:1.25 million Cuba map. The island map is good, and it has indexed town plans of Havana, Playas del Este, Varadero, Cienfuegos, Camagüey and Santiago de Cuba.

For good basic maps, pick up one of the provincial Guías available in Infotur offices.

Return to beginning of chapter

MONEY

This is a tricky part of any Cuban trip and the double economy takes some getting used to. Two currencies circulate in Cuba: Convertible pesos (CUC$) and Cuban pesos (referred to as moneda nacional, abbreviated MN). Most things tourists pay for are in Convertibles (eg accommodation, rental cars, bus tickets, museum admission and internet access). At the time of writing, Cuban pesos were selling at 25 to one Convertible, and while there are many things you can’t buy with moneda nacional, using them on certain occasions means you’ll see a bigger slice of authentic Cuba. The prices in this book are in Convertibles unless otherwise stated.

Making everything a little more confusing, euros are also accepted at the Varadero, Guardalavaca, Cayo Largo del Sur, as well as Cayo Coco and Cayo Guillermo resorts, but once you leave the resort grounds, you’ll still need Convertibles. For information on costs, Click here, and for exchange rates go to the Quick Reference on the inside front cover of this book.

The best currencies to bring to Cuba are euros, Canadian dollars or pounds sterling (all liable to an 8% to 11.25% commission). The worst is US dollars and – despite the prices you might see posted up in bank windows – the commission you’ll get charged is a whopping 20% (the normal 10% commission plus an extra 10% penalty – often not displayed). At the time of writing, traveler’s checks issued by US banks could be exchanged at branches of Banco Financiero Internacional, but credit cards issued by US banks could not be used at all. Note that Australian dollars are not accepted anywhere in Cuba.

Cadeca branches in every city and town sell Cuban pesos. You won’t need more than CUC$10 worth of pesos a week. In addition to the offices located on the maps in this book, there is almost always a branch at the local agropecuario (vegetable market). If you get caught without Cuban pesos and are drooling for that ice-cream cone, you can always use Convertibles; in street transactions such as these, CUC$1 is equal to 25 pesos and you’ll receive change in pesos. There is no black market in Cuba, only hustlers trying to fleece you with money-changing scams (see boxed text,).

ATMs & Credit Cards

When the banks are open, the machines are working and the phone lines are live, credit cards are an option – as long as the cards are not issued by US banks. You will be charged an 11.25% fee on every credit-card transaction. This is made up of the 8% levy charged for all foreign currency exchanges (which must first be converted into US dollars) plus a standard 3.25% conversion fee. However, in reality, credit card and cash payments work out roughly the same; with cash you pay the 11.25% levy when you exchange your foreign money into Convertibles at the bank. Nonetheless, due to poor processing facilities, lack of electronic equipment and nonacceptance of many US-linked cards, cash is still by far the best option in Cuba.

Cash advances can be drawn from credit cards but the commission’s the same. Check with your home bank before you leave, as many banks won’t authorize large withdrawals in foreign countries unless you notify them of your travel plans first.

ATMs are good for credit cards only and are the equivalent to obtaining a cash advance over the counter. In reality it is best to avoid them altogether (especially when the banks are closed), as they are notorious for eating up people’s cards.

Some, but not all, debit cards work in Cuba. Take care as machines sometimes ‘eat’ cards.

Cash

Cuba is a cash economy and credit cards don’t have the importance or ubiquity that they do elsewhere in the western hemisphere. Although carrying just cash is far riskier than the usual cash/credit-card/traveler’s-check mix, it’s infinitely more convenient. As long as you use a concealed money belt and keep the cash on you or in your hotel’s safe deposit box at all times, you should be OK.

It’s better to ask for CUC$20/10/5/3/1 bills when you’re changing money, as many smaller Cuban businesses (taxis, restaurants etc) can’t change anything bigger (ie CUC$50 or CUC$100 bills) and the words no hay cambio (no change) resonate everywhere. If desperate, you can always break big bills at hotels.

Denominations & Lingo

One of the most confusing parts of a double economy is terminology. Cuban pesos are called moneda nacional (abbreviated MN) or pesos Cubanos or simply pesos, while Convertible pesos are called pesos convertibles (abbreviated CUC) or often just simply…pesos. Sometimes you’ll be negotiating in pesos (Cubanos) and your counterpart will be negotiating in pesos (Convertibles). It doesn’t help that the notes look similar as well. Worse, the symbol for both Convertibles and Cuban pesos is $. You can imagine the potential scams just working these combinations.

The Cuban peso comes in notes of one, five, 10, 20, 50 and 100 pesos; and coins of one (rare), five and 20 centavos, and one and three pesos. The five-centavo coin is called a medio, the 20-centavo coin a peseta. Centavos are also called kilos.

The Convertible peso comes in multicolored notes of one, three, five, 10, 20, 50 and 100 pesos; and coins of five, 10, 25 and 50 centavos, and one peso.

Tipping

If you’re not in the habit of tipping, you’ll learn fast in Cuba. Wandering son (Cuban popular music) septets, parking guards, ladies at bathroom entrances, restaurant wait staff, tour guides – they all work for hard-currency tips. Musicians who besiege tourists while they dine, converse or flirt will want a Convertible, but only give what you feel the music is worth. Washroom attendants expect CUC$0.05 to CUC$0.10, while parqueadores (parking attendants) should get CUC$0.25 for a short watch and CUC$1 for each 12 hours. For a day tour, CUC$2 per person is appropriate for a tour guide. Taxi drivers will appreciate 10% of the meter fare, but if you’ve negotiated a ride without the meter, don’t tip as the whole fare is going straight into their wallets.

Tipping can quickly resolver las cosas (fix things up). If you want to stay beyond the hotel check-out time or enter a site after hours, for instance, small tips (CUC$1 to CUC$5) bend rules, open doors and send people looking the other way. For tipping in restaurants and other advice, see the Food & Drink chapter (see boxed text,).

Traveler’s Checks

While they add security and it makes sense to carry a few for that purpose, traveler’s checks are a hassle in Cuba although they work out better value than credit cards. Bear in mind that you’ll pay commission at both the buying and selling ends (3% to 6%) and also be aware that some hotels and banks won’t accept them (especially in the provinces). The Banco Financiero Internacional is your best bet for changing Amex checks, though a much safer all-round option is to bring Thomas Cook.

Return to beginning of chapter

POST

Letters and postcards sent to Europe and the US take about a month to arrive. While sellos (stamps) are sold in Cuban pesos and Convertibles, correspondence bearing the latter has a better chance of arriving. Postcards cost CUC$0.65 to all countries. Letters cost CUC$0.65 to the Americas, CUC$0.75 to Europe and CUC$0.85 to all other countries. Prepaid postcards, including international postage, are available at most hotel shops and post offices and are the surest bet for successful delivery. For important mail, you’re better off using DHL, located in all the major cities; it costs CUC$55 for a 900g letter pack to Australia, or CUC$50 to Europe.

Return to beginning of chapter

SHOPPING

If shopping’s one of your favorite vacation pastimes, don’t make a special trip to Cuba. To the relief of many and the disappointment of a few, Western-style consumerism hasn’t yet reached the time-warped streets of Cuba’s austere capital. That’s not to say you have to walk away empty-handed. Pampering to a growing number of well-off travelers, Cuba’s tourist industry has upped the ante considerably in recent years and specialist shops are spreading fast.

The Holy Grail for most foreign souvenir-hunters is a box of Cuban cigars, closely followed by a bottle of Cuban rum, both of which are significantly cheaper than in stores in Europe or Canada. Another often overlooked bargain is a bag of Cuban coffee, a potent and aromatic brew made from organically grown beans and best served espresso-style with a dash of sugar.

Elsewhere memorabilia is thin on the ground. Aimed strictly at the tourist market, you’ll find cheap dolls, flimsy trinkets, mediocre woodcarvings and low-quality leather goods, but Cuba is a world leader in none of these things. Far better as long-lasting souvenirs are salsa CDs, arty movie posters, musical instruments or a quirky string of Santería beads.

Paintings are another of Cuba’s fortes and local artists selling their work from small private studios are both numerous and talented. If you buy an original painting, print or sculpture, be sure to ask for a receipt to prove you bought it at an official sales outlet; otherwise, it could be confiscated by customs upon departure (Click here).

In a country where clothes were – until recently – rationed, and lycra is still considered to be the height of cool, finding the latest pair of Tommy Hilfiger jeans could prove a little difficult. Incurable fashion junkies can spend their Convertibles on pleated guayabera shirts or a yawningly predictable Che Guevara T-shirt (if you don’t mind being reduced to a walking cliché). Take your pick.

Cigars

Visitors are allowed to export CUC$2000 worth of documented cigars per person. Amounts in excess of this, or black-market cigars without receipts, will be confiscated (Cuban customs is serious about this, with an ongoing investigation into cigar rings and more than half a million seizures of undocumented cigars annually). The tax-free limit without a receipt is two boxes (50 cigars) or 23 singles of any size or cost. Of course, you can buy additional cigars in the airport departure lounge once you’ve passed Cuban customs, but beware of your limits when entering other countries. (Mexican customs in Cancún, for instance, conducts rigorous cigar searches.) If you traveled without a license to Cuba, US customs will seize any tobacco you have upon entering; licensed travelers are permitted to bring the equivalent of US$100 worth of cigars into the US. (Imitation Cuban cigars sold in the US contain no Cuban tobacco.)

La Casa del Habano (www.habanos.net) is the national cigar store chain, where the staff is well informed, there’s a wide selection and sometimes a smoking lounge.

For more information on Cuban cigars, see the boxed text.

Return to beginning of chapter

TELEPHONE

The Cuban phone system is still undergoing some upgrading, so beware of phone-number changes. Normally a recorded message will inform you of any recent upgrades. Most of the country’s Etecsa telepuntos have now been completely refurbished, which means there will be a spick-and-span (as well as airconditioned) phone and internet office in almost every provincial town.

Mobile Phones

Cuba’s two mobile-phone companies are c.com ( 7-264-2266) and Cubacel (www.cubacel.com). While you may be able to use your own equipment, you have to prebuy their services. Cubacel has more than 15 offices around the country (including the Havana airport) where you can do this. Its plan costs approximately CUC$3 per day and each local call costs from CUC$0.52 to CUC$0.70. Note that you pay for incoming as well as outgoing calls. International rates are CUC$2.70 per minute to the US and CUC$5.85 per minute to Europe.

7-264-2266) and Cubacel (www.cubacel.com). While you may be able to use your own equipment, you have to prebuy their services. Cubacel has more than 15 offices around the country (including the Havana airport) where you can do this. Its plan costs approximately CUC$3 per day and each local call costs from CUC$0.52 to CUC$0.70. Note that you pay for incoming as well as outgoing calls. International rates are CUC$2.70 per minute to the US and CUC$5.85 per minute to Europe.

Phone Codes

To call Cuba from abroad, dial your international access code, Cuba’s country code ( 53), the city or area code (minus ‘0’ which is used when dialing domestically between provinces), and the local number. In this book, area codes are indicated at the start of each chapter. To call internationally from Cuba, dial Cuba’s international access code (

53), the city or area code (minus ‘0’ which is used when dialing domestically between provinces), and the local number. In this book, area codes are indicated at the start of each chapter. To call internationally from Cuba, dial Cuba’s international access code ( 119), the country code, the area code and the number. To the US, you just dial

119), the country code, the area code and the number. To the US, you just dial  119, then 1, the area code and the number.

119, then 1, the area code and the number.

To place a call through an international operator, dial  09, except to the US, which can be reached with an operator on

09, except to the US, which can be reached with an operator on  66-12-12. Not all private phones in Cuba have international service, in which case you’ll want to call collect (reverse charges or cobro revertido). This service is available only to Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, France, Italy, Mexico, Panama, Spain, UK, US and Venezuela. International operators are available 24 hours and speak English. You cannot call collect from public phones.

66-12-12. Not all private phones in Cuba have international service, in which case you’ll want to call collect (reverse charges or cobro revertido). This service is available only to Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, France, Italy, Mexico, Panama, Spain, UK, US and Venezuela. International operators are available 24 hours and speak English. You cannot call collect from public phones.

Phonecards

Etecsa is where you buy phonecards, send and receive faxes, use the internet and make international calls. Blue public Etecsa phones accepting magnetized or computer-chip cards are everywhere. The cards are sold in Convertibles: CUC$5, CUC$10 and CUC$20, and Cuban pesos: three, five and seven pesos. You can call nationally with either, but you can call internationally only with Convertible cards. If you are mostly going to be making national and local calls, buy a peso card as it’s much more economical.

The best cards for calls from Havana are called Propia. They come in pesos (five- and 10-peso denominations) and Convertibles (CUC$10 and CUC$25 denominations) and allow you to call from any phone – even ones permitting only emergency calls – using a personal code. The rates are the cheapest as well.

Phone Rates

Local calls cost five centavos per minute, while interprovincial calls cost from 35 centavos to one peso per minute (note that only the peso coins with the star work in pay phones). Since most coin phones don’t return change, common courtesy asks that you push the ‘R’ button so that the next person in line can make their call with your remaining money.

International calls made with a card cost from CUC$2 per minute to the US and Canada and CUC$5 to Europe and Oceania. Calls placed through an operator cost slightly more.

Return to beginning of chapter

TIME

Cuba is on UTC/GMT minus five between October and April and UTC/GMT minus four (daylight-saving time) between April and October – the same as New York or Washington.

Return to beginning of chapter

TOILETS

Look for public toilets at bus stations, tourist hotels or restaurants, and gas stations. It is unlikely you’ll meet a Cuban who would deny a needy traveler the use of their bathroom. In public restrooms there often won’t be water or toilet paper and never a toilet seat. The faster you learn to squat and carry your own supply of paper, the happier you’ll be. Frequently there will be an attendant outside bathrooms supplying toilet paper and you’re expected to leave CUC$0.05 or CUC$0.10 in the plate provided. If the bathrooms are dirty or the attendant doesn’t supply paper, you shouldn’t feel compelled to leave money.

Cuban sewer systems are not designed to take toilet paper and every bathroom has a small waste basket beside the toilet for this purpose. Aside from at top-end hotels and resorts, you should discard your paper in this basket or risk an embarrassing backup.

Return to beginning of chapter

TOURIST INFORMATION

At the time of writing, Infotur (www.infotur.cu), Cuba’s official tourist information bureau, had offices in Havana (Habana Vieja, Miramar, Playas del Este, Expocuba, the José Martí Airport), Trinidad and Ciego de Ávila (in the city and at Jardines del Rey airport, Cayo Coco). Travel agencies, such as Cubanacán or Cubatur, can usually supply some general information.

Return to beginning of chapter

TRAVELERS WITH DISABILITIES

Cuba’s inclusive culture translates to disabled travelers, and while facilities may be lacking, the generous nature of Cubans generally compensates. Sight-impaired travelers will be helped across streets and given priority in lines. The same holds true for travelers in wheelchairs, who will find the few ramps ridiculously steep and will have trouble in colonial parts of town where sidewalks are narrow and streets are cobblestone. Elevators are often out of order. Etecsa phone centers have telephone equipment for the hearing-impaired and TV programs are broadcast with closed captioning.

Return to beginning of chapter

VISAS & TOURIST CARDS

Regular tourists who plan to spend up to two months in Cuba do not need visas. Instead, you get a tarjeta de turista (tourist card) valid for 30 days (Canadians get 90 days), which can be extended for another 30 days once you’re in Cuba. Those going ‘air only’ usually buy the tourist card from the travel agency or airline office that sells them the plane ticket (equivalent of US$15 extra). Package tourists receive their card with their other travel documents.

Unlicensed tourists originating in the US buy their tourist card at the airline desk in the country through which they’re traveling en route to Cuba (equivalent of US$25). You are usually not allowed to board a plane to Cuba without this card, but if by some chance you are, you should be able to buy one at Aeropuerto Internacional José Martí in Havana – although this is a hassle (and risk) best avoided. Once in Havana, tourist-card extensions or replacements cost another CUC$25. You cannot leave Cuba without presenting your tourist card, so don’t lose it. You are not permitted entry to Cuba without an onward ticket. Note that Cubans don’t stamp your passport on either entry or exit; instead they stamp your tourist card.

The ‘address in Cuba’ line should be filled in, if only to avoid unnecessary questioning. As long as you are staying in a legal casa particular or hotel, you shouldn’t have problems.

Business travelers and journalists need visas. Applications should be made through a consulate at least three weeks in advance (longer if you apply through a consulate in a country other than your own).

Visitors with visas or anyone who has stayed in Cuba longer than 90 days must apply for an exit permit from an immigration office. The Cuban consulate in London issues official visas (£32 plus two photos). They take two weeks to process, and the name of an official contact in Cuba is necessary.

Extensions

For most travelers, obtaining an extension once in Cuba is easy: you just go to the inmigración (immigration office) and present your documents and CUC$25 in stamps. Obtain these stamps from a branch of Bandec or Banco Financiero Internacional beforehand. You’ll only receive an additional 30 days after your original 30 days, but you can exit and re-enter the country for 24 hours and start over again (some travel agencies in Havana have special deals for this type of trip; Click here). Attend to extensions at least a few business days before your visa is due to expire and never attempt travel around Cuba with an expired visa. Nearly all provincial towns have an immigration office (closed Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday) though the staff rarely speak English and they aren’t always overhelpful. Try to avoid Havana’s office if you can as it gets ridiculously crowded.

- Baracoa (Map; Antonio Maceo No 48;

8am-noon & 2-4pm Mon-Fri)

8am-noon & 2-4pm Mon-Fri) - Bayamo (Map; Carretera Central Km 2;

9am-noon & 1:30-4pm Tue & Thu-Fri) In a big complex 200m south of the Hotel Sierra Maestra.

9am-noon & 1:30-4pm Tue & Thu-Fri) In a big complex 200m south of the Hotel Sierra Maestra. - Camagüey (Map; Calle 3 No 156 btwn Calles 8 & 10, Reparto Vista Hermosa;

8am-11:30am & 1-3pm Mon-Fri, except Wed)

8am-11:30am & 1-3pm Mon-Fri, except Wed) - Ciego de Ávila (Map; cnr Delgado & Independencia;

8am-noon & 1-5pm Mon & Tue, 8am-noon Wed-Fri)

8am-noon & 1-5pm Mon & Tue, 8am-noon Wed-Fri) - Cienfuegos (Map;

43-52-10-17; Av 46 btwn Calles 29 & 31)

43-52-10-17; Av 46 btwn Calles 29 & 31) - Guantánamo (Map; Calle 1 Oeste btwn Calles 14 & 15 Norte;

8:30am-noon & 2-4pm Mon-Thu) Directly behind Hotel Guantánamo.

8:30am-noon & 2-4pm Mon-Thu) Directly behind Hotel Guantánamo. - Guardalavaca (Map;

24-43-02-26/7) In the police station at the entrance to the resort. Head here for visa extensions; there’s also an immigration office in Banes.

24-43-02-26/7) In the police station at the entrance to the resort. Head here for visa extensions; there’s also an immigration office in Banes. - Havana (Map; cnr Calle Factor al final & Santa Ana, Nuevo Vedado) This office is specifically for extensions and has long queues. Get there early. It has no phone, but you can direct questions to immigration proper at

7-203-0307.

7-203-0307. - Holguín (Map; cnr General Marrero & General Vázquez;

8am-noon & 2-4pm Mon-Fri) Arrive early – it gets crowded here.

8am-noon & 2-4pm Mon-Fri) Arrive early – it gets crowded here. - Las Tunas (off Map; Av Camilo Cienfuegos, Reparto Buenavista) Northeast of the train station.

- Sancti Spíritus (Map;

41-32-47-29; Independencia Norte No 107;

41-32-47-29; Independencia Norte No 107;  8:30am-noon & 1:30-3:30pm Mon-Thu)

8:30am-noon & 1:30-3:30pm Mon-Thu) - Santa Clara (off Map; cnr Av Sandino & Sexta;

8am-noon & 1-3pm Mon-Thu) Three blocks east of Estadio Sandino.

8am-noon & 1-3pm Mon-Thu) Three blocks east of Estadio Sandino. - Santiago de Cuba (Map;

22-69-36-07; Calle 13 No 6 btwn Av General Cebreco & Calle 4;

22-69-36-07; Calle 13 No 6 btwn Av General Cebreco & Calle 4;  8:30am-noon & 2-4pm Mon, Tue, Thu & Fri) Stamps for visa extensions are sold at the Banco de Crédito y Comercio at Felix Peña No 614 on Parque Céspedes.

8:30am-noon & 2-4pm Mon, Tue, Thu & Fri) Stamps for visa extensions are sold at the Banco de Crédito y Comercio at Felix Peña No 614 on Parque Céspedes. - Trinidad (Map; Julio Cueva Díaz;

8am-5pm Tue-Thu) Off Paseo Agramonte.

8am-5pm Tue-Thu) Off Paseo Agramonte. - Varadero (Map; cnr Av 1 & Calle 39;

8am-3:30pm Mon-Fri)

8am-3:30pm Mon-Fri)

Entry Permits for Cubans & Naturalized Citizens

Naturalized citizens of other countries who were born in Cuba require an autorización de entrada (entry permit) issued by a Cuban embassy or consulate. Called a Vigencia de Viaje, it allows Cubans resident abroad to visit Cuba as many times as they like over a two-year period. Persons hostile to the Revolution or with a criminal record are not eligible.

The Cuban government does not recognize dual citizenship. All persons born in Cuba are considered Cuban citizens unless they have formally renounced their citizenship at a Cuban diplomatic mission and the renunciation has been accepted. Cuban-Americans with questions about dual nationality can contact the Office of Overseas Citizens Services, Department of State, Washington, DC 20520.

Licenses for US Visitors

In 1961 the US government imposed an order limiting the freedom of its citizens to visit Cuba, and airline offices and travel agencies in the US are forbidden to book tourist travel to Cuba via third countries. However, the Cuban government has never banned Americans from visiting Cuba, and it continues to welcome US passport holders under exactly the same terms as any other visitor.

Americans traditionally go to Cuba via Canada, Mexico, the Bahamas, Jamaica or any other third country. Since American travel agents are prohibited from handling tourism arrangements, most Americans go through a foreign travel agency. Travel agents in those countries (Click here) routinely arrange Cuban tourist cards, flight reservations and accommodation packages.

The immigration officials in Cuba know very well that a Cuban stamp in a US passport can create problems. However, many Americans request that immigration officers not stamp their passport before they hand it over. The officer will instead stamp their tourist card, which is collected upon departure from Cuba. Those who don’t ask usually get a tiny stamp on page 16 or the last page in the shape of a plane, barn, moon or some other random symbol that doesn’t mention Cuba.

The US government has an ‘Interests Section’ in Havana, but American visitors are advised to go there only if something goes terribly wrong. Therefore, unofficial US visitors are especially careful not to lose their passports while in Cuba, as this would put them in a very difficult position. Many Cuban hotels rent security boxes (CUC$2 per day) to guests and nonguests alike, and you can carry a photocopy of your passport for identification on the street.

At the time of writing there were two types of licenses issued by the US government to visit Cuba: general licenses (typically for government officials, journalists and professional researchers) and specific licenses (for visiting family members, humanitarian projects, public performances, religious activities and educational activities). The Bush administration cut back on both types of licenses in 2003 cutting off 70% of the travel that had previously been deemed ‘legal.’ Early moves by the Obama administration have been less asphyxiating and in April 2009 the ‘visiting family members’ category was opened up. Cuban-Americans now face neither time stipulations nor financial restrictions when visiting extended family members on the island.

For more information, contact the Licensing Division ( 202-622-2480; www.treas.gov/ofac; Office of Foreign Assets Control, US Department of the Treasury, 2nd fl, Annex Bldg, 1500 Pennsylvania Ave NW, Washington, DC 20220). Travel arrangements for those eligible for a license can be made by specialized US companies such as Marazul or ABC Charters (Click here).

202-622-2480; www.treas.gov/ofac; Office of Foreign Assets Control, US Department of the Treasury, 2nd fl, Annex Bldg, 1500 Pennsylvania Ave NW, Washington, DC 20220). Travel arrangements for those eligible for a license can be made by specialized US companies such as Marazul or ABC Charters (Click here).

Under the Trading with the Enemy Act, goods originating in Cuba are prohibited from being brought into the US by anyone but licensed travelers. Cuban cigars, rum, coffee etc will be confiscated by US customs, and officials can create additional problems if they feel so inclined. Possession of Cuban goods inside the US or bringing them in from a third country is also banned.

American travelers who choose to go to Cuba (and wish to avoid unnecessary hassles with the US border guards) get rid of anything related to their trip to Cuba, including used airline tickets, baggage tags, travel documents, receipts and souvenirs, before returning to the US. If Cuban officials don’t stamp their passport, there will be no official record of their trip. They also use a prepaid Cuban telephone card to make calls to the US in order to avoid there being records of collect or operator-assisted telephone calls.

Since September 11, 2001, all international travel issues have taken on new import, and there has been a crackdown on ‘illegal’ travel to Cuba. Though it has nothing to do with terrorism, some Americans returning from Cuba have had ‘transit to Cuba’ written in their passports by Jamaican customs officials. Customs officials at major US entry points (eg New York, Houston, Miami) are onto backpackers coming off Cancún and Montego Bay flights with throngs of honeymoon couples, or tanned gentlemen arriving from Toronto in January. They’re starting to ask questions, reminding travelers that it’s a felony to lie to a customs agent as they do so.

The maximum penalty for ‘unauthorized’ Americans traveling to Cuba is US$250,000 and 10 years in prison. In practice, people are usually fined US$7500. Under the Bush administration, the number of people threatened with legal action had more than tripled, however the early signs from the Obama administration indicate these numbers are likely to fall. More than 100,000 US citizens a year travel to Cuba with no consequences. However, as long as these regulations remain in place, visiting Cuba certainly qualifies as soft adventure travel for Americans. There are many organizations, including a group of congresspeople on Capitol Hill, working to lift the travel ban (see www.cubacentral.com for more information).

Return to beginning of chapter

VOLUNTEERING

There are a number of bodies offering volunteer work in Cuba though it is always best to organize things in your home country first. Just turning up in Havana and volunteering can be difficult, if not impossible. Take a look at the following:

- Canada-Cuba Farmer to Farmer Project (www.farmertofarmer.ca) Vancouver-based sustainable agriculture organization.

- Canada World Youth (

514-931-3526; www.cwy-jcm.org) Head office in Montreal, Canada.

514-931-3526; www.cwy-jcm.org) Head office in Montreal, Canada. - Cuban Solidarity Campaign (

020 8800 0155; www.cuba-solidarity.org) Head office in London, UK.

020 8800 0155; www.cuba-solidarity.org) Head office in London, UK. - National Network on Cuba (www.cubasolidarity.com) US-based solidarity group.

- Pastors for Peace (PFP;

212-926-5757; www.ifco news.org) Collects donations across the US to take to Cuba.

212-926-5757; www.ifco news.org) Collects donations across the US to take to Cuba. - Witness for Peace (WFP;

202-588-1471; www.witnessforpeace.org) Looking for Spanish-speakers with a two-year commitment.

202-588-1471; www.witnessforpeace.org) Looking for Spanish-speakers with a two-year commitment.

Return to beginning of chapter

WOMEN TRAVELERS

In terms of personal safety, Cuba is a dream destination for women travelers. Most streets can be walked alone at night, violent crime is rare and the chivalrous part of machismo means you’ll never step into oncoming traffic. But machismo cuts both ways, with protecting on one side and pursuing – relentlessly – on the other. Cuban women are used to piropos (the whistles, kissing sounds and compliments constantly ringing in their ears), and might even reply with their own if they’re feeling frisky. For foreign women, however, it can feel like an invasion.

Ignoring piropos is the first step. But sometimes ignoring them isn’t enough. Learn some rejoinders in Spanish so you can shut men up. No me moleste (don’t bother me), está bueno ya (all right already) or que falta respeto (how disrespectful) are good ones, as is the withering ‘don’t you dare’ stare that is also part of the Cuban woman’s arsenal. Wearing plain, modest clothes might help lessen unwanted attention; topless sunbathing is out. An absent husband, invented or not, seldom has any effect. If you go to a disco, be very clear with Cuban dance partners what you are and are not interested in. Dancing is a kind of foreplay in Cuba and may be viewed as an invitation for something more. Cubans appreciate directness and as long as you set the boundaries, you’ll have a fabulous time. Being in the company of a Cuban man is the best way to prevent piropos, and if all else fails, retire to the pool for a day out of the line of fire and re-energize.

Traveling alone can be seen as an invitation for all kinds of come-ons; solo women travelers won’t have an easy time of it. Hooking up with a male traveler (or another woman, at least to deflect the barrage) can do wonders.