The term “empire” has a well-established pedigree within the historiography of Southeast Asia, both mainland and maritime/island (the two areas into which the region is normally subdivided). Angkorean Cambodia is most frequently characterized as an “empire,”1 as is Vietnam, since from the late tenth century onward its rulers generally assumed the Sinic imperial title of hoàng đế (Chinese huangdi). In the island world, Srivijaya (the early maritime polity based on Sumatra)2 is sometimes, though not consistently, honored with this title, as is the last great pre-Islamic Javanese kingdom, Majapahit. The earliest entity to win the status of “empire” was Funan (in the Mekong Delta during the pre-Angkorean period), usually seen as the region’s first state. At the same time, however, historians of Southeast Asia have grown increasingly wary of traditional interpretations of the region’s premodern polities, particularly those emphasizing all-powerful “god-kings” ruling over large expanses of territory with relatively fixed borders. Rulers and their domains have been trimmed down to size by the popularization of various models which emphasize the often fragile nature of royal authority, and the fissiparous tendencies of most polities. Where, then, does this leave mainland Southeast Asia in a discussion of empires and imperialism?

This chapter represents an attempt to formulate a model of “empire” which fits mainland Southeast Asia, specifically the area stretching from Myanmar to Vietnam, before the nineteenth century. The first part of the discussion will provide a brief overview of the various models of Southeast Asian states proposed over the past few decades. The next will synthesize the salient features of these models into a single integrated framework that will hopefully provide a meaningful distinction between what could legitimately be considered Southeast Asian “empires” and their less powerful neighbors. The chapter will conclude with a comparative discussion of kingship and ideology between the Sinic and Indic cultures within the region.

For much of the twentieth century “empire” was used by leading scholars of Southeast Asian history to describe several precolonial polities, notably Funan, Srivijaya, and Angkorean Cambodia. This practice began with colonial-era historians—both European and Asian—who were themselves operating within the intellectual and geopolitical frameworks of empire, so that it did not appear problematic to apply the term to those earlier polities which seemed to have been most powerful, durable, and expansionist in nature. Nor could they be accused of facile Eurocentrism, given that China, Japan, and Mughal India, among others, were widely recognized as “imperial” entities.3

In recent decades, the term “empire,” though not abandoned completely, has become much more restricted in its use for precolonial Southeast Asia. This change, however, is a reaction much less against any perceived Eurocentrism than against a more Sinocentric bias.4 O. W. Wolters was the first scholar to raise the issue of the distorting lens of Chinese sources, which tended to assume that China’s Southeast Asian “vassals” were, like Japan or Korea, smaller copies of itself, “kingdoms” ruled by “kings.” (There could, of course, be no other “emperor” beside the Son of Heaven himself.) Wolters suggested that historians’ heavy reliance on data culled from Chinese texts caused them to exaggerate both the size and the structural strength of early Southeast Asian polities, so that several powerful “kingdoms” found in Chinese sources became “empires” in Western scholarship.5

One of the first targets of this rethinking of early Southeast Asia was Funan, the pre-Angkorean polity centered in the Mekong Delta between roughly the third and sixth centuries ce, which was believed to have been supplanted (forcefully) by the equally large and powerful kingdom of Zhenla, which in turn gave way to Angkor at the beginning of the ninth century. Most historians writing prior to the 1980s described Funan as an “empire,” and published maps showed it as a large, sprawling entity of varying proportions, depending on a particular author’s interpretation.6 Wolters and Claude Jacques, however, whittled “Funan” and “Zhenla” down to a more manageable size—a task subsequently continued and refined by Michael Vickery.7 There is now a general consensus that “Funan,” whatever it may have been, was neither large nor imperial, and even a recent book devoted to it reflects the more modest perspective.8

Funan is not the only “empire” to have been thus downsized; generally speaking the term has considerably less currency than it once did. George Coedès, D. G. E. Hall, and John Cady used it fairly widely, both for specific polities and for collectively categorizing whole groups of states.9 At present, it is less common to find a Southeast Asian history text referring to “empires,” with one significant exception: Angkorean Cambodia. Whether because of its size, its long life, or its famous architectural legacy, Angkor managed to hold on to its “imperial” status while many of its neighbors lost theirs; more on that below.10

Concern with specific terms such as “empire” has generally been outweighed by a broader interest in the nature and structure of the precolonial Southeast Asian state. In the late 1970s, two workshops were held to discuss this subject, which produced a collection of chapters looking at very specific aspects of several precolonial polities. Editor Lorraine Gesick in her introduction noted the “problematic” nature of the classical Southeast Asian “state”: “The closer one looks at any given state in traditional Southeast Asia, the more it seems to dissolve before one’s eyes. Upon examination, it appears not to be ‘governed’ nor even ‘administered’ in any very systematic way at all, and one is forced to ask just what it is that holds such a ‘state’ together.”11 Although this statement would probably be considered somewhat pessimistic three decades on, its implicit but fundamental problematization of the applicability of Western models of the “state” still rings true.

Before the 1977–78 workshops were held, at least two scholars, both of them anthropologists with a historical bent, had already attempted to formulate alternate models for Southeast Asian polities. Stanley Tambiah coined the term “galactic polity” to show the relationship between a core/center and its outlying territories, which he compared to a sun surrounded by different planets, each revolving in its own orbit—in his words “a hierarchy of central points continually subject to the dynamics of pulsation and changing spheres of influence.” These “planets” enjoyed varying degrees of autonomy depending on their geographical distance from the capital and the nature of their relationship with the center (province, tributary, etc.).12 Although Tambiah’s model was meant to apply mainly to Thai history and more specifically to Ayudhya (the polity which became known to foreigners as “Siam”), he did suggest it could be applied elsewhere in Southeast Asia.13 Similarly, Clifford Geertz used a study of precolonial Bali to suggest a “theatre state” model. Geertz’s essential argument was that in the fragmented Balinese geopolitical environment rulers used ritual and displays of culture to proclaim their supremacy as much as they did displays of force. Like Tambiah, Geertz was interested in one particular part of Southeast Asia but believed that his model was potentially applicable to much or all of the region.14

It is significant that the first models specifically intended for Southeast Asian states came from anthropologists, as historians generally tended to chronicle the rise and fall of individual states and the conflicts among them without particular attention to the structure of those states, or the nature of the power which held them together. The first historian who began to do so in the Southeast Asian context in any significant way was Wolters, who in his landmark 1982 study History, Culture, and Region in Southeast Asian Perspectives sought to formulate a model of Southeast Asian polities that would explain the dynamics of their internal structure and external relations in distinctively—though not uniquely—Southeast Asian terms. Wolters chose the mandala, a term of Indic origin which can be found in Sanskrit-language inscriptions in the region. Like the mandala, he argued, many Southeast Asian kingdoms could be represented as a series of concentric circles expanding outward from a core. The ruler’s power radiated outward from this core, growing weaker as it extended from the center to the periphery. Wolters particularly emphasized the structural instability and fluctuating size of these mandalas, dependent as they were on the ruler’s personal charisma and “prowess”; he saw them as expanding and contracting like concertinas, without fixed borders.15

The mandala model, though not without its critics, has met with wide acceptance among scholars of Southeast Asian history.16 There is a general consensus that Wolters’s characterization of the inconstant nature of a ruler’s “personal hegemony” is a useful correction to earlier historians who enumerated strong and weak kings and dynasties without looking carefully at the nature of their power. Similarly, the concertina metaphor is a much more accurate representation of most polities than the fixed borders implied by standard historical maps of the region. Indeed, a case can be made that a good map of early Southeast Asia will be organized around centers rather than boundaries.17

The main difficulty in utilizing Wolters’s mandala framework is that it is to some extent a “one-size-fits-all” structure which is applicable to some polities in certain periods of time but without a clear indication of the criteria for its use. Wolters includes Ayudhya, Angkor, Srivijaya, Majapahit, and the pre-Hispanic Philippine polities of Mindoro and Sulu in his list of mandalas. He explicitly excludes Lanna (the Chiang Mai–based kingdom in Northern Thailand), Lane Xang (Laos), and Burma on the grounds that they were probably “impermanent sub regional associations which depended on the waxing and waning of particular mandala centres and which never led to new and more enduring political systems.” Vietnam is also largely disqualified because its borders were “preordained by Heaven and permanent in a manner that the porous borders of the mandalas ... never assumed.”18 Other scholars, by contrast, have argued that Vietnam/Đại Việt—under earlier dynasties, at least—can in fact be considered as a mandala, on the grounds that it shared the structural fragility and multicentric nature of neighboring polities.19

There is of course no compelling reason why all of mainland Southeast Asia, let alone the entire region, should have to be fitted into a single model such as the mandala. Yet finding common characteristics to define the region has become a kind of Holy Grail for Southeast Asianists, and historians are eager to join the quest. That includes two other frameworks which are more ambitious than Wolters’s mandala model in their attempt to cover more of the region.

In the early 1980s, Indologist Hermann Kulke articulated a three-stage model of state formation, first specifically for Java and then more broadly for the region. The broader model was presented at a conference organized in response to Wolters’s 1982 book, where Kulke praised the mandala approach while somehow implying that it was not fully adequate. His critique of Wolters was extremely discreet, but he seemed to suggest that the mandala tells us much more about how a polity functions than about how it was formed in the first place. Moreover—and again this point has to be inferred from Kulke’s discussion—Wolters’s model does not distinguish between different types and stages of mandalas but simply discusses them as a single type of polity.20 Both points are well-taken.

Kulke’s model is structured around three successive stages of state formation: the Chieftaincy, the Early Kingdom, and the Imperial Kingdom. The first of these characterizes polities of limited territory and with little or no institutionalized bureaucracy whose ruler exercises power on a very localized scale. A Chieftaincy which is able to expand and consolidate its power and territory will evolve into an Early Kingdom, whose leader uses a new Indianized title such as “rāja” but is still largely primus inter pares among the other rulers in his region. Early Kingdoms possess the fundamentally fissiparous and centrifugal nature of Wolters’s mandalas. Finally, a select few of these polities are able to grow into supra-regional Imperial Kingdoms, consolidating their own territory and conquering that of neighboring Early Kingdoms, whose autonomy is then “extinguished” through a process of “provincialization” within the imperial entity. Imperial Kingdoms benefit from a considerable and permanent expansion of their core area, are governed through a bureaucracy, and are relatively centripetal in nature, leaving behind the unstable structure of their predecessors.21

The criteria for inclusion within Kulke’s framework are not completely clear. He identifies four Imperial Kingdoms—Pagan, Angkor, Majapahit, and Vietnam—largely on the basis of their structure and durability. Srivijaya and Champa are relegated to the status of Early Kingdoms because they did not survive long enough to morph into imperial entities. Curiously absent from Kulke’s discussion is the Tai world, for reasons which are not explained. The other omission is the Philippines, which is perhaps more understandable given the general lack of specific knowledge about pre-Hispanic polities as well as the general assumption that they were generally smaller than most of their Indianized counterparts.22 Overall, however, his distinction between Early and Imperial Kingdoms is a useful and persuasive one which permits a greater degree of differentiation among Southeast Asian polities than does the more “one-size-fits-all” mandala model.

More recently, Victor Lieberman has authored a massive and highly informative study of mainland Southeast Asian history. He places the region in an even broader comparative perspective with East Asia and Europe, a scale engaged more broadly by this volume and series. Lieberman distinguishes between what he calls the “charter states” of early Southeast Asia—Pagan, Angkor, Champa, and Đại Việt (Vietnam)—and their successors. The charter states are those which essentially laid the foundations for later polities in the early-modern period. Lieberman draws on several of the models discussed above—notably those of Wolters and Tambiah—though he prefers “solar polity” to the latter’s “galactic polity” on the grounds that “most galaxies lack a distinct central body and their components defy enumeration.” The “successor states” are subdivided into “decentralized Indic,” “centralized Indic,” and “Chinese-style” based on criteria of structure, strength, and degree of administrative control (taxation, ability to mobilize manpower, etc.).23 The “charter”-“successor” dichotomy forms the essential taxonomy for Lieberman’s discussion; “polity,” “state,” “kingdom,” and “empire” are more or less interchangeable throughout the book.

Among these various models, Kulke’s Imperial Kingdom is arguably the most useful in allowing us to identify “empires” as distinct entities in mainland Southeast Asia. Yet because of his exclusion of the Tai world and, for all practical purposes, Burma, it is inadequate for the “early-modern period,” when Angkor’s decline facilitated the expansion of Siamese, Burmese, and Vietnamese polities.24 Indeed, Kulke’s classification would probably be more precise if he had limited it to the kingdoms which were more directly “Indianized” and left out Burma and Vietnam completely. One of the reasons that the latter two polities remain peripheral to his argument is that he is looking at Southeast Asia primarily through a “Sanskrit lens,” whereas Vietnam was of course culturally Sinified and Pagan belonged to the Pali-oriented Theravada world. Lieberman’s thorough and lucid taxonomy, however, allows us to neatly classify every significant polity in the region, but the goal of defining a mainland imperial model remains elusive.

This chapter suggests a model which is to some extent a synthesis of the others but which would enable us to distinguish clearly between “imperial” and “non-imperial” polities across the region. Five key characteristics of a mainland “empire” can be identified. First, while like almost all polities in precolonial Southeast Asia, the “empire” possessed some of the characteristics of a mandala (notably a certain degree of structural fragility and the personalized nature of royal power), it was more stable and durable than the polities that Kulke classifies as Early Kingdoms. Second, as a result of this it maintained a relatively high degree of territorial continuity over the long term (allowing for changes in ruling dynasty and/or capital), and much or all of its precolonial “geo-body” is preserved in a present-day nation-state.25 Third, the “empire’s” historical trajectory incorporated a high degree of territorial expansion through the absorption of other polities. Fourth, it had an ethnically diverse population, but its multiethnic character was due primarily to expansion rather than to immigration (e.g., of Chinese or Indians). Finally, in the geopolitics of the mainland region, the “empire” was generally the aggressor rather than the victim, the attacker rather than the target.

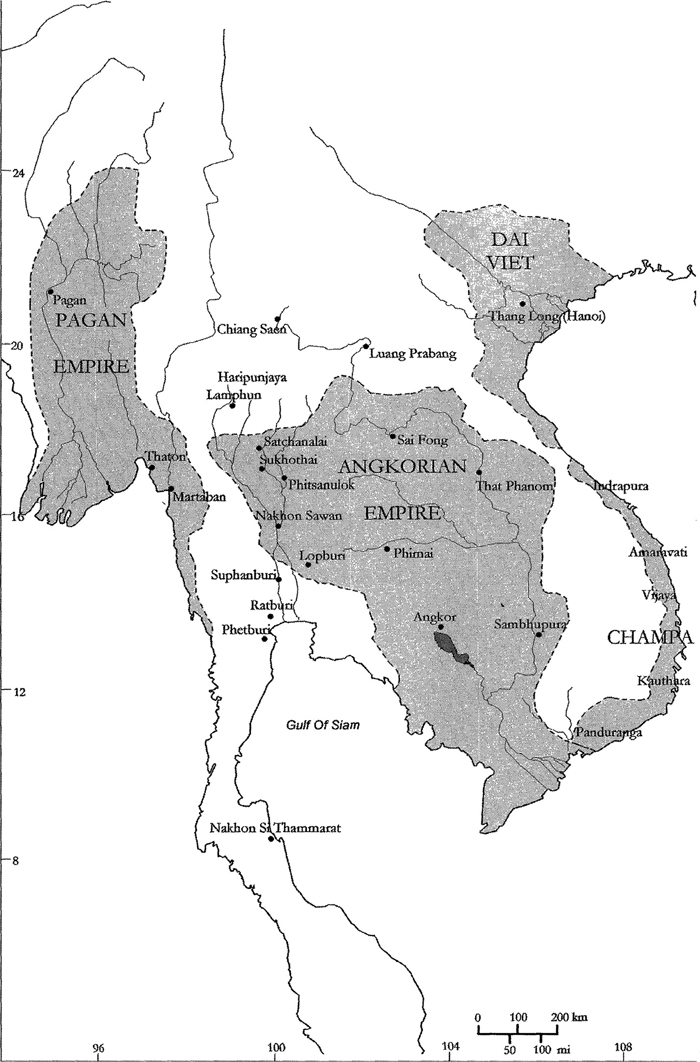

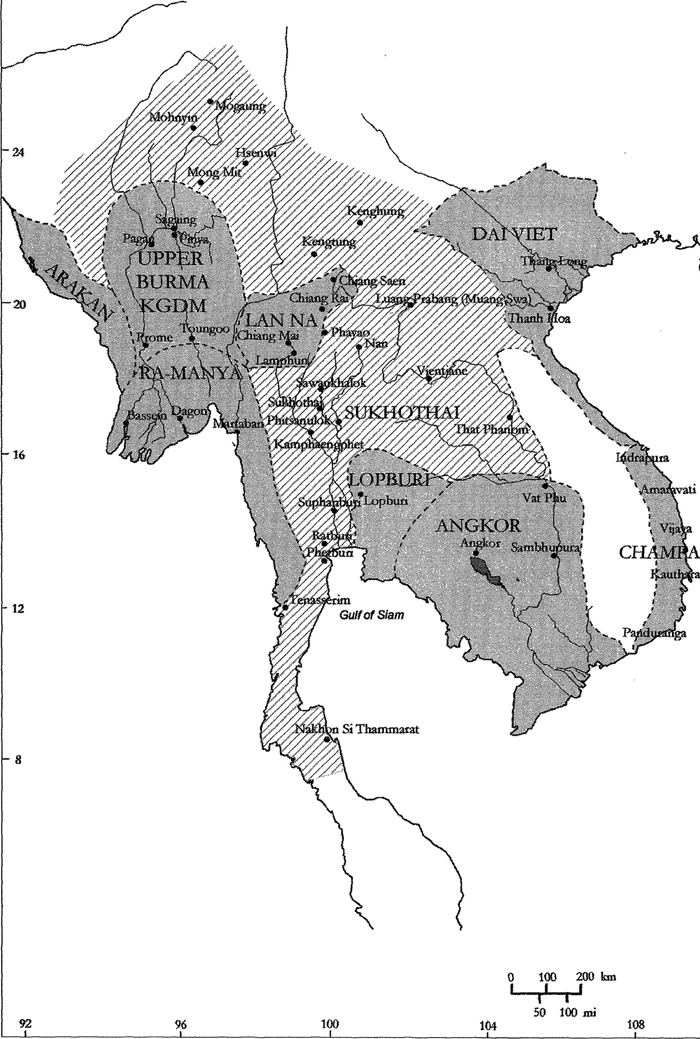

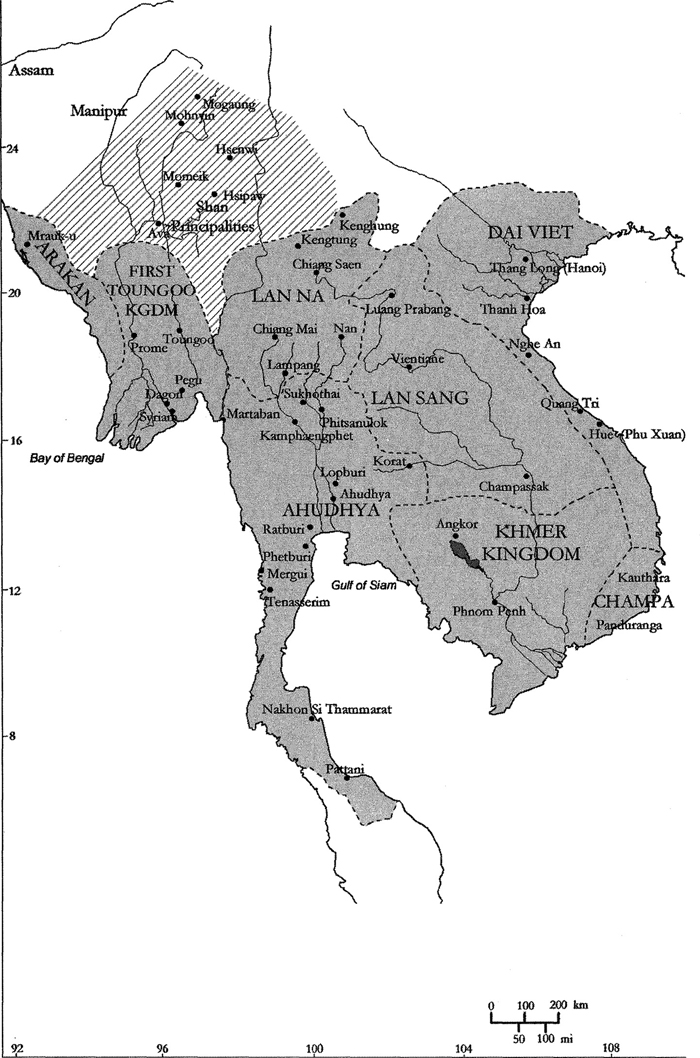

Based on these criteria the history of mainland Southeast Asia can be structured around five main empires: Pagan (the Burmese polity from the mid-ninth through the late thirteenth centuries), Burma (under the Toungoo/Restored Toungoo and Konbaung dynasties from the late fifteenth through the late nineteenth centuries), Siam (including Ayudhya and its successors the Thonburi and Bangkok kingdoms), Vietnam (spanning both its period of unity and its extended division into two separate polities), and Angkor. Although it would be more convenient to treat “Burma” as a single entity, the fragmentation and shrinking of the kingdom which took place during the “Ava period” between the end of Pagan and the rise of the Toungoo Dynasty would seem to justify the distinction made here. (By contrast, Ayudhya and Đại Việt both maintained the same political center and territorial core over a period of several centuries.) Each of these fits the framework just described, and collectively they constitute what might be called the “regional superpowers” of mainland Southeast Asia.

Of the five, Burma experienced the most violent cycles of waxing and waning of dynasties linked to specific capitals. While the political center changed from period to period, and there were frequent civil wars and conflicts between rival polities, there was a consistent “imperial core” which gave continuity to these successive polities, particularly those following Ava. What might be called the “ethnic core” of the polity diversified from its Burman (ethnic Burmese) origins to include Mon and Karen populations under its direct control, as well as the Arakanese with the annexation of that kingdom in the late eighteenth century. The upland Shan, although not under direct Burmese rule, had a long history of political involvement with their suzerain’s affairs, and Burma was still exercising a certain degree of overlordship at the point of British colonization. In addition to the military campaigns against the neighboring groups just mentioned, the Burmese under the Restored Toungoo and Konbaung dynasties constituted the major external threat in the Tai world, effectively controlling Lanna from the mid-sixteenth to late eighteenth centuries, and fighting wars with Lane Xang and Ayudhya as well. The two most serious defeats suffered by the latter kingdom, in 1569 and 1767, were both at the hands of the Burmese.26

These defeats, however, were relatively small though tragic blots on a broader historical record of Siamese victories and expansion. Although the kingdom of Ayudhya started as a primus inter pares among several different Tai polities in the region, it enjoyed a comparatively high degree of stability and structural integrity over the long run which enabled it to absorb smaller and weaker neighbors such as Sukhothai and Nakhon Si Thammarat (to its north and south, respectively). By the time of its collapse in 1767, it had established suzerainty over Cambodia and several Malay states. The short-lived Thonburi polity of King Taksin (1767–82), established almost immediately after Ayudhya’s fall, and the Bangkok dynasty which replaced it and is still in power today, replaced Burmese overlordship in Lanna with their own, and expanded their influence in the Lao kingdoms across the Mekong. It was only the advent of British and French imperialism which shrunk Siam’s sphere of influence, and even after signing away all claims to most of its non-Siamese vassal territories, it was still able to incorporate the Lanna territories and the Lao territories on the west bank of the Mekong within its own borders.27

Vietnam, like Burma, went through cycles of division and unity for much of its history, but they were arguably less violent. The first durable dynasties—the Lý (early eleventh to early thirteenth centuries) and the Trần (early thirteenth to late fourteenth centuries)—established a polity with a relatively fixed territorial core and began the centuries-long process of southward expansion. (Although Vietnam—known as Đại Việt for most of this period—was smaller and ethnically more homogeneous under these two dynasties, the foundations and precedents for later institutional growth and territorial expansion were established before 1400.) A twenty-year interlude of Chinese occupation in the early 1400s was followed by the foundation of the Lê dynasty, which ruled a unified Đại Việt for a hundred years before being replaced by the usurping Mạc dynasty for much of the sixteenth century. A civil war reestablished the Lê at the very end of that century, but for most of the next 200 years there were effectively two Vietnams: Đại Việt in the north (known to Europeans as Tonkin and to Vietnamese as Đàng Ngoài) and a southern kingdom known to Westerners as Cochin China and to Vietnamese as Đàng Trong. Following three decades of divisive warfare in the late 1700s, the Nguyễn dynasty—Vietnam’s last—unified the country at the turn of the century and ruled it through the period of French colonialism, France having chosen to maintain this monarchy under its “protection.”28

As just noted, most of Vietnam’s territorial expansion was southward, with the gradual conquest and colonization of the lands belonging to the Cham (known collectively as Champa) and then the Mekong Delta, inhabited by Cambodians. This expansion, usually referred to as the Nam Tiến (southward advance), constituted the main thrust of Vietnamese imperialism—a phenomenon which remains embarrassing and sensitive even today for historians who wish to portray their country as the constant historical victim of aggression rather than as an aggressor itself.29 From the seventeenth century onward, the Vietnamese were in direct competition with the Siamese for influence in Cambodia and—subsequently and to a lesser extent—in the Lao kingdoms. As for the upland areas of what is now northern, northwestern, and central Vietnam, some parts of them came under Vietnamese overlordship (though not direct control) whereas others remained completely independent until they were pacified by the French.

Finally, we come to Angkor (more properly Angkorean Cambodia), which has for most foreign scholars remained the most “imperial” of the early Southeast Asian polities and the only one which is consistently designated as an “empire.” This status is partly due to its size, which although sometimes exaggerated by present-day maps (especially in terms of its control over present-day Thai and Lao territory) was undeniably considerable. At its height under the great King Jayavarman VII (ca. 1181–ca. 1220) it was almost certainly the largest polity in the region, and the scope of its territory was only surpassed by Burma and Ayudhya after its disappearance from the geopolitical scene. Although the available inscriptions tell us much less than we would like to know about its structure and governance, over the long term it seems to have enjoyed a reasonable degree of political stability and continuity even while remaining in some respects a typical Southeast Asian mandala. During its early centuries it expanded from its ethnic Khmer core to govern a large swathe of territory which was probably Mon, and at its zenith its realm included a certain number of Tai-speaking migrants along the periphery, although admittedly extant historical sources do not permit us to reconstruct the displacement of Angkorean rule by Tai polities with any degree of precision.30 The gradual contraction of its sphere of influence starting at the earliest in the mid-thirteenth century, concomitant with the expansion of the Tai world, culminated in the reduction of the Cambodian polity to roughly its present size (though still including the Mekong Delta) by the fifteenth century, along with a shift in its power center from Angkor to the area around Phnom Penh where it has remained since that time.31

It is precisely because of the fairly clear chronological and geopolitical boundary between the Angkorean and post-Angkorean polities that only the former is classified as an “empire” under our present model. The Cambodia which survived from 1500 onward comprised largely though not exclusively an ethnic Khmer population and, more important for our purposes, continued to shrink rather than to expand. Although it was able to hold its own politically and military through the sixteenth century, from the early 1600s onward it was permanently caught between its powerful neighbors to the West and East and was never again to enjoy true political independence until after the end of French colonial rule. Swatches of territory in its western provinces came under Siamese rule, while the Mekong Delta gradually shifted over to Vietnamese control. Almost nowhere else in Southeast Asia is there such a clear shift from being a geopolitical aggressor to being a victim.32

Three other polities which played a significant role in the region’s history should be mentioned here although they do not meet the criteria for being “empires.” Champa, while once considered as a single kingdom and by some scholars even as an empire, is now seen by most historians as at most a kind of federation or grouping of smaller mandala-style kingdoms. The earliest Cham polity may have been in existence as early as the third century, and the last one was not completely swallowed up by Vietnam until the early 1800s, but it is virtually impossible to squeeze it into an “imperial” framework.33 Lanna, the Northern Thai kingdom founded in the late thirteenth century, existed as a separate polity for more than 500 years, but it never achieved a high degree of internal stability, and for much of its existence it was subordinate to either Burmese or Siamese overlordship.34 Finally, the Lao kingdom of Lane Xang (established as a single entity in the mid-fourteenth century) only existed as a relatively unified polity until 1700, when it broke into several smaller and more vulnerable components.35

These empires can be roughly classified as “Indic” or “Sinic” based on the civilizations which most heavily influenced their respective cultures. The first category can be further subdivided into “Hindu-Buddhist”36 and “Theravada” polities, the former referring to Angkor and the latter to Pagan/Burma and the Tai kingdoms. (Although Angkor by its final century had shifted to Theravada Buddhism, for most of its history its ruling class included devotees of Śiva, Viṣṇu, and/or Buddha, the latter through the teachings of Indian schools, mainly Mahayana.) We will consider kingship and ideology first in the Indic world, then in Sinic Vietnam, and finally in a brief comparative context.

The distinction between “king” and “emperor,” though very clear in some cultures, is neither clear nor consistent in the world of Indic kingship. Most rulers were “kings,” “great kings,” or “kings of kings,” with various titles and honors appended to those basic appellations. Within a specifically Theravada Buddhist context, the ideal ruler was a dhammarāja, the Pali-language term for a king who exemplified the ideals of the dhamma (Sanskrit dharma) or Buddhist teachings. A particularly ambitious Theravada ruler might claim to be a chakkavatti (Sans. chakravartin)—usually translated as “wheel-rolling ruler,” the wheel symbolizing the dhamma. A chakkavatti was a sort of “dhammarāja on steroids” ready and willing to expand his territory through a combination of superior virtue and military strength. Only a few rulers in Burmese and Thai history laid claim to this title, and chakkavatti status was largely a self-proclaimed attribute rather than a separate category of ruler.37

Legitimacy in Indic kingship was based to a large extent on individual attributes, although family/dynastic connections were not irrelevant. Angkorean rulers in particular were very much concerned with demonstrating their blood ties to earlier kings, and their inscriptions often contained genealogical information. (In some cases scholars believe that these family details were partly or completely falsified in order to buttress a questionable claim to the throne.) That said, a king was of course obliged to demonstrate his virtue as a follower of the particular deity he worshipped, and his spiritual merits would be enumerated with considerable rhetorical flourish in any inscription linked to his authority.38

Theravada polities, while existing within the framework of dynastic lines, generally articulated their ideas of legitimacy more in terms of the individual’s merits than of his lineage. In the context of Pagan, Michael Aung-Thwin has aptly coined the term “kammarāja” to emphasize the importance of a ruler’s kamma (the Pali equivalent of the better-known Sanskrit term karma), the balance of his good and bad deeds from his previous existences which had enabled him to take the throne.39 As in Angkor, the ruler had to demonstrate his spiritual merits and religious devotion, which, along with the general prosperity of his realm, were indications that his kamma had “bequeathed” him the right to rule. A glaring deficiency in any of the areas just mentioned would raise serious questions about this right and leave him vulnerable to the claims of a rival. Rivalry could and did frequently take place within a ruling lineage, but it could just as easily come from outside that lineage, and if it did, royal blood would offer little protection to a ruler otherwise deemed unfit to sit on the throne.

The Sinic worldview inherited by the Vietnamese—particularly, though not exclusively, the ruling class—makes a clear distinction between an “emperor” (hoàng đế/huangdi) and a “king” (vương/wang), although traditionally it does not distinguish between “empire” and “kingdom,” both of which are simply “countries” (quốc/guo). By contrast, the indigenous and colloquial Vietnamese term for a ruler, “vua,” can refer to either an “emperor” or a “king” depending on the context, and outside the ruling class the difference between the two may not have been very relevant, since most Vietnamese would have had no contact with, or knowledge of, any ruler other than their own.40 For the ruling elite, however, the difference was highly significant. If the chronicles are correct, every Vietnamese monarch from the mid-tenth century onward used the Sino-Vietnamese title (hoàng) đế in the context of his own realm, but in dealings with China, the “emperor” had to be downgraded to a “king” because only one full-fledged “Son of Heaven” could exist, and he could not be in Hanoi or Hue. Conversely, all other rulers of whom the Vietnamese had knowledge (Cham, Cambodian, Thai, etc.) were routinely referred to as “kings.”41

The process of Sinicization of Vietnam’s political culture was a long and gradual one, and textual evidence suggests that Confucianism was not firmly in place as an ideology until after the fifteenth-century Ming Occupation. The first decades of independence in the tenth century saw a somewhat disconnected series of rulers who, despite later historians’ valiant efforts to reshape their reigns into successive though short-lived dynasties, seem to have been more or less independent strong men, the kind of leader whom Wolters dubs “men of prowess.”42 The Lý and Trần rulers were almost certainly more devoutly Buddhist than they were Confucianist, and they did things which shocked later generations of scholars, such as honoring Buddha more prominently than the ancestral spirits or holding a birthday party during a time of mourning for a parent. It is probable that their legitimacy in their subjects’ eyes was framed mainly in Buddhist terms, though it also seems clear that Confucian ideas of royal succession based on primogeniture and the importance of dynastic ties were beginning to take hold during this time.43

From the fifteenth century onward, however, Confucian ideals gradually became more firmly implanted in Vietnamese society, and not just within the ruling class—most probably because one of the most significant aspects of the Ming Occupation was the expansion of the educational system. The belief in legitimacy derived from the Heavenly Mandate (Thiên Mệnh/Tianming) became thoroughly entrenched, and while an individual ruler’s virtue (đức/de) was certainly important, his attachment to a dynastic lineage was even more so. Dynastic change was no small occurrence, and clear evidence of one family’s decline (and thus the loss of the Heavenly Mandate) was necessary before another family could legitimately take its place. (It is worth noting, for example, that for almost the entire period between 1428 and 1789 there was a Lê ruler governing at least some part of Vietnam, despite the extended Mạc usurpation/interregnum of the sixteenth century and the existence of the separate Nguyễn kingdom from roughly 1600 onward.)44

One of the challenges to formulating a single model for mainland Southeast Asia—whether it be state structure, kingship, or in this case empire—is the need to incorporate both the Indic and Sinic worldviews. In this comparative discussion there are three main points of comparison between Vietnam and its Indic neighbors to consider: legitimacy and dynastic stability, structural or state stability, and the ideology of territorial expansion. I will suggest that broadly speaking, the Sinic model provided more strength and stability in the first two areas while in the third, the two models were equally effective, even though they articulated their respective ideologies in different terms.45

As was noted above, legitimacy in the Indic polities was linked to individual rulers’ merits more than to their lineage, although genealogical claims were not irrelevant. It seems that family ties were more significant in Angkor than in the Theravada polities, whose rulers were generally more concerned with proving their own merit than with demonstrating their legitimacy as a member of the ruling family. It is tempting to hypothesize that this can be explained by the difference between Angkor’s Hindu-Buddhist framework of kingship and the Sinhalese model that was imported into Theravada kingdoms, but such a hypothesis would need to be evaluated by scholars with greater expertise than mine in the original theories of kingship in India and Sri Lanka. Certainly Theravada at the level of praxis is structured around a preoccupation with individual merit-making and karma, and this could well be reflected in a greater emphasis on personal qualities when it came to royal legitimacy.

The Confucian worldview which gradually penetrated Vietnamese society and came to characterize its kingship by the early fifteenth century (and almost certainly before that, though to what extent is unclear) attributed great weight to an individual’s “virtue,” but the counterweight to this was the legitimacy of the Mandate of Heaven, which was bestowed on a dynasty rather than an individual. The consequence of this was that a dynasty could produce one or two incompetent or immoral rulers without its legitimacy being seriously questioned; in other words, a rotten apple or two did not spoil the whole bunch. It usually took a sequence of bad rulers, along with the ominous portents of natural disasters (reinforced by the human suffering that these produced if the state’s response to them was inadequate) to bring about a consensus that the ruling dynasty had lost the Heavenly Mandate and could be legitimately challenged or replaced. The fact that for almost the entire period between 1000 and 1900 Vietnamese were under the rule of one of only four dynasties (Lý, Trần, Lê, and Nguyễn) testifies to the relative long-term stability of the Sinic dynastic model.

Confucian ideology also provided a stabilizing element through the practice of royal succession based on primogeniture. This practice was largely institutionalized from the beginning of the Lý, and although Vietnamese history has no shortage of episodes of succession crises (usually due to rivalries between siblings, especially those of different mothers), on the whole there were fewer of them than in the Indic kingdoms. For Angkor we do not have chronicles to narrate the events surrounding the accession of each ruler, but the scholars who have gone through the inscriptions to map out the polity’s history have found ample evidence of political instability, usurpation, and the occasional civil war. For the Theravada polities there were extended periods when every single royal succession caused bloodshed; in Burma there was a violent succession crisis as late as the mid-nineteenth century, when half the country was already under British rule. Overall the pattern of succession was a key factor behind the stability (or lack thereof) in Southeast Asian empires.

A second important difference between the two models was the nature of the state. Although the early Vietnamese dynasties relied on a mixture of princes, officials, and (in the eleventh century, at least) monks to govern their polity, the basic structures of a Chinese-style administration were gradually put in place. The establishment of the Lê saw the consolidation of a full-fledged Confucian state which modeled itself after China as closely as possible, and from that point onward government by mandarins trained in the examination system became the norm. (The examination system was abolished only under colonial rule, and in much of Vietnam the French preserved it until just before the First World War). This contrasted significantly with the Theravada states, which were based on hierarchies and networks of personal ties. This is not to say that there were no official positions or titles in these hierarchies or that personal ties did not count in the Vietnamese bureaucracy, but the core nature of the state differed significantly between the two models. Angkor seems to have been to some extent a blend of the two: there is evidence of a fairly well-structured bureaucracy, but analysis of the corpus of inscriptions shows the influence of powerful families linked to specific regions of the polity.46

What are the possible implications for the stability of these polities? If we consider this point together with the previous one, it is worth noting that in the Vietnamese system it was extremely difficult for someone from outside the royal family to overthrow the ruling dynasty and replace it with another, since a commoner would have a very difficult time proving that he was more deserving of the Heavenly Mandate. In the two cases where a Vietnamese dynasty was permanently displaced by usurpation—the Lý in the early thirteenth and the Trần in the late fourteenth century—the usurping family had previously married into the royal clan and thus took power “from within.” By contrast, when the Lê were pushed out by the Mạc in the 1520s, they reestablished themselves in another part of the kingdom almost immediately and eventually regained the throne. Conversely, in Theravada polities where individual merit contributed to legitimacy more than family affiliation and where many officials had regional power bases with their own supplies of manpower, it was not difficult for an ambitious noble from a province outside the capital to seize power and proclaim a new dynasty. A noble family could become a royal family literally overnight, and as long as its hold on power was firm, its newfound royal credentials would generally go unchallenged. This was particularly the case in Ayudhya, where it happened twice in the course of the seventeenth century.

Although the various empires may have differed in terms of their concepts of legitimacy and kingship and the stability of their state, they all shared the ambition for territorial expansion and the ability to justify it in terms of their particular ideology. The rulers of Đại Việt expected their neighbors, all of whom were represented (at least on paper, though probably not always in reality) as vassals or tributaries, to show proper respect and deference to their “virtue” and “authority” (uy, Ch. wei). Any lesser ruler who failed to do so was fair game for an attack in order to bring him back into line. The invasion might be a one-off campaign (as with attacks on Champa in 1044 and Lane Xang in 1479) or a more protracted affair leading to territorial conquest, such as the major onslaught on Champa in 1471.47

Angkorean epigraphy does not tell us a lot about military campaigns in particular or territorial expansion in general, and the scope of the empire’s territory under a particular ruler can only be mapped out very roughly by the location of his inscriptions. The rhetoric of conquest is certainly there, however.48 In Theravada polities, above and beyond the cakkavatti ideal discussed above, which was directly linked to expansion and war, a ruler could invoke his own superior merit to attack a neighbor on the grounds that its ruler was not sufficiently patronizing or protecting Buddhism in his realm.49 As with Vietnam, such campaigns could involve a short-term invasion (probably with some capture of manpower) or long-term annexation, depending on the situation. The language of aggression varied, but the results were the same.

We can suggest, then, that a particular model of “empire” based on the five characteristics enumerated above characterized the strongest and most durable polities of precolonial mainland Southeast Asia. This model is certainly not unique to the region, but it does transcend ethnic and cultural differences while recognizing the possibility of ideological and structural variation within the imperial framework. While these polities were not the only players on the geopolitical scene, over the long term they were the main ones, and without exception their smaller, weaker neighbors ended up as their vassals and tributaries, when not partially or completely absorbed as directly ruled provinces. These empires dominated the region well into the nineteenth century, even after the arrival of the British and French (beginning with the First Anglo-Burmese War of 1824–26). Their confrontation with the Western imperial Great Powers belongs to the next chapter of the historical narrative.

Notes

1See, for example, three books spanning a century of scholarship on Angkor: Georges Maspéro, L’empire khmèr (Phnom Penh: Imprimerie du Protectorat, 1904); Lawrence Palmer Briggs, The Ancient Khmer Empire (Philadelphia, PA: American Philosophical Society, 1951); and Claude Jacques and Philippe Lafond, The Khmer Empire, trans. Tom White (Bangkok: River Books, 2007).

2On Srivijaya and other Malay polities, see the chapter by Sher Banu Khan in this volume.

3See the chapters by Wang Jinping, Frederick Vermote, and Murari Jha in this volume.

4One of the few concerted attacks on perceived Eurocentrism in Western historiography on precolonial Southeast Asian history is by Michael Aung-Thwin, who is particularly bothered by what he perceives as the distorting implications of the term “classical”; see his “The Classical in Southeast Asia: The Present in the Past,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 26, no. 1 (1995), 75–91.

5O. W. Wolters, “Northwestern Cambodia in the Seventh Century,” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 37, no. 2 (1974), 355–84.

6See, for example, the important textbooks by George Coedès, The Indianized States of Southeast Asia, ed. Walter F. Vella and trans. Susan Brown Cowing (Honolulu: East-West Center Press, 1968); D. G. E. Hall, A History of South-East Asia, 4th edn (New York: St Martin’s Press, 1981); and John F. Cady, Southeast Asia: Its Historical Development (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964). Such maps can be found today on numerous websites, including Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Funan).

7Claude Jacques, “‘Funan,’ ‘Zhenla.’ The Reality Concealed by These Chinese Views of Indochina,” in Early South-East Asia: Essays in Archaeology, History and Historical Geography, ed. R. B. Smith and W. Watson (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), pp. 371–9; Michael Vickery, “Where and What Was Chenla,” in Recherches nouvelles sur le Cambodge, ed. François Bizot (Paris: École Française d’Extême-Orient, 1994), pp. 197–212; Michael Vickery, “Funan Reviewed: Deconstructing the Ancients,” Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient 90 (2003), 101–43.

8James C. M. Khoo (ed.), Art and Archaeology of Fu Nan: Pre-Khmer Kingdom of the Lower Mekong Valley (Bangkok: Orchid Press, 2003).

9See Coedès, Indianized States; Hall, History; and Cady, Southeast Asia.

10A recent and more systematic discussion of Angkor as an “empire” is found in Eileen Lustig, “Power and Pragmatism in the Political Economy of Angkor,” PhD dissertation, Department of Archaeology, University of Sydney, 2009.

11“Introduction,” in Centers, Symbols, and Hierarchies: Essays on the Classical States of Southeast Asia, ed. Lorraine Gesick (New Haven: Yale University Southeast Asia Studies, 1983), p. 1.

12Stanley J. Tambiah, World Conqueror and World Renouncer: A Study of Buddhism and Polity in Thailand against a Historical Background (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1976), p. 113.

13Stanley J. Tambiah, “The Galactic Polity in Southeast Asia,” in Tambiah, Culture, Thought, and Social Action (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1973), pp. 3–31.

14Clifford Geertz, Negara: The Theatre State in Nineteenth-Century Bali (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980).

15See O. W. Wolters, History, Culture, and Region in Southeast Asian Perspectives, rev. edn (Ithaca, NY: Cornell Southeast Asia Program, 1999).

16It is used, for example, by Charles Higham, Early Mainland Southeast Asia: From First Humans to Angkor (Bangkok: River Books, 2014); and Paul Michel Munoz, Early Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula (Singapore: Éditions Didier Millet, 2006). One attempt to criticize the mandala model is Deborah Tooker, “Putting the Mandala in Its Place,” Journal of Asian Studies 55, no. 2 (1996), 323–58; however, a case can be made that Tooker is to some extent setting up a straw man because she is critiquing Wolters’s model in the context of the uplands, where he did not try to apply it.

17See, for example, the maps in Higham, Early Mainland Southeast Asia.

18Wolters, History, Culture, and Region, pp. 35–6.

19See, for example, John Whitmore, “‘Elephants Can Actually Swim’: Contemporary Chinese Views of Late Ly Dai Viet,” in Southeast Asia in the 9th to 14th Centuries, ed. David G. Marr and A. C. Milner (Canberra and Singapore: ANU RSPS and ISEAS), pp. 117–37.

20Hermann Kulke, “The Early and the Imperial Kingdom in Southeast Asian History,” in Marr and Milner, eds, Southeast Asia, pp. 1–22.

21Ibid.

22Ibid. The term “Tai” refers to speakers of various different languages, the most important in Southeast Asia being Thai, Lao, and Shan. The “Tai world” in this context would include the kingdoms of Sukhothai, Ayudhya, Lane Xang, and Lanna.

23Victor Lieberman, Strange Parallels Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800–1830, vol. 1 (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), pp. 31–7; quotation from p. 33.

24In the case of the Siamese, it is probably more accurate to say that the expansion of the Tai kingdoms and the contraction of the Angkorean polity occurred in tandem with each other. A more precise cause-and-effect relationship is difficult to determine.

25On the geo-body, see Thongchai Winichakul, Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-Body of a Nation (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1994). Thongchai’s concept incorporates spatial/geographical/territorial and emotional/psychological elements of nationhood.

26See Lieberman, Strange Parallels, chap. 2; Victor Lieberman, Burmese Administrative Cycles: Anarchy and Conquest, c. 1580–1760 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984); and William J. Koenig, The Burmese Polity, 1752–1819: Politics, Administration and Social Organization in the Early Kon-baung Period (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies, 1990).

27See Lieberman, Strange Parallels, chap. 3; David Wyatt, Thailand: A Short History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003); and B. J. Terwiel, Thailand’s Political History: From the Fall of Ayutthaya in 1767 to Recent Times (Bangkok: River Books, 2005).

28See Lieberman, Strange Parallels, chap. 1; K. W. Taylor, A History of the Vietnamese (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013); and Lê Thành Khôi, Histoire du Viêt-Nam; des origines à 1858 (Paris: Sudestasie, 1981).

29This issue is discussed in more detail in Bruce M. Lockhart, “Colonial and Post-Colonial Constructions of ‘Champa,’” in The Cham of Vietnam: History, Society, and Art, ed. Trần Kỳ Phương and Bruce M. Lockhart (Singapore: NUS Press, 2011), pp. 16–22.

30Migration of Tai-speakers from their home region in the present Sino-Vietnamese border region probably began in the early second millennium ce. The first polities under Tai rulers in the northern regions of what is now Thailand appeared after 1200 along the peripheries of the Angkorean empire, and it was precisely during the thirteenth century that Angkorean influence in that area began to contract.

31See David Chandler, History of Cambodia, 4th edn (Boulder: Westview Press, 2008).

32This process is summarized in ibid. and covered in detail in Mak Phoeun, Histoire du Cambodge de la fin du XVIe siècle au début du XVIIIe (Paris: École Française d’Extrême-Orient, 1995); and Khin Sok, Le Cambodge entre le Siam et le Viêtnam (de 1775 à 1860) (Paris: École Française d’Extrême-Orient, 1991).

33The recent rethinking of Champa is discussed in various chapters of Phương and Lockhart, eds, Cham of Vietnam.

34General histories of Lanna can be found in Saratsawadi Ongsakun, History of Lan Na (Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 2005); and Hans Penth, A Brief History of Lan Na: Civilisations of North Thailand (Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 2000).

35See Martin Stuart-Fox, The Lao Kingdom of Lan Xang: Rise and Decline (Bangkok: White Lotus Press, 1998).

36My use of this term does not ignore the issues raised by some scholars as to whether present-day “Hinduism” is a construct put together in colonial India; “Hindu” in this context is a shorthand for Saivite, Vishnuite, and Brahmanic beliefs.

37This concept of kingship is discussed in detail in Tambiah, World Conqueror, pp. 39–53; and Sunait Chutintaranond, “‘Cakravartin’: The Ideology of Traditional Warfare in Siam and Burma, 1548–1605,” PhD dissertation, Cornell University, 1990, pp. 71–135. Sunait mentions several examples of Burmese and Siamese kings who claimed the attributes of a cakkavatti (pp. 93–6). Modern Thai uses “chakkaphat” and “chakkawat,” derivatives of the Pali term, to translate “emperor” and “empire,” respectively, but not in reference to Southeast Asian rulers.

38Ian Mabbett, “Kingship in Angkor,” Journal of the Siam Society 66, no. 2 (1978), 1–58.

39Michael Aung-Thwin, “Divinity, Spirit, and Human: Conceptions of Classical Burmese Kingship,” in Gesick, ed., Centers, Symbols, and Hierarchies, pp. 69–72; and Aung-Thwin, “Kingship, the Sangha, and Society in Pagan,” in Explorations in Early Southeast Asian History, ed. Kenneth R. Hall and John K. Whitmore (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies, 1976), pp. 205–55.

40See Alexander Barton Woodside, Vietnam and the Chinese Model, 2nd edn (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988), pp. 9–11, for a discussion of the semantic and cultural differences between the terms “vua” and “hoàng đế.”

41Any attempt to sort out terminological issues for Vietnam’s precolonial history is always made more complicated by the fact that most Vietnamese texts, especially chronicles and diplomatic correspondence, were written in classical Chinese by Confucian scholars for whom maintaining these hierarchical and semantic distinctions was crucial. It is quite possible that outside the Court all rulers—Chinese, Vietnamese, Siamese, and so on—were simply referred to informally as “vua,” but this cannot be determined from the sources.

42On “prowess” in Southeast Asian rulers, see Wolters, History, Culture and Region, pp. 18–21, 93–5, 112–13.

43Keith Taylor has also stressed the significance of animistic beliefs for at least the early Lý rulers, though this seems to have gradually faded away; see Taylor, “Authority and Legitimacy in 11th Century Vietnam,” in Marr and Milner, eds, Southeast Asia, pp. 139–75. The non-Confucianist nature of Trần-dynasty Đại Việt is ably discussed in Shawn McHale, “‘Texts and Bodies’: Refashioning the Disturbing Past of Tran Vietnam,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 42, no. 4 (1999), 494–518.

44An excellent overview of Vietnamese kingship is Nguyễn Thế Anh, “La conception de la monarchie divine dans le Việt-Nam traditionnel,” Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient 84 (1997), 147–57.

45Lieberman, Strange Parallels, covers some of the same comparative ground as this part of the chapter. Although I have read and generally agree with his arguments, the ideas here are derived from my own scholarly trajectory as a comparativist of Vietnam and the Tai world.

46See the discussion in Lustig, “Power and Pragmatism.”

47Prior to invading Champa in 1044, the Lý ruler mused out loud as to whether the Cham had failed to send tribute because his “authority and virtue” (uy đức) had failed to reach their distant country; see Đại Việt Sử Ký Toàn Thư [Complete annals of Đại Việt] (Hànội: Khoa Học Xã Hội, 1993), vol. 1, p. 264 (entry for 1043). An excellent study of the much harsher official Confucianist rhetoric linked to the campaigns of the 1470s is John Whitmore, “The Two Great Campaigns of the Hong-Duc era (1470–1497) in Dai Viet,” South East Asia Research 12, no. 1 (2004), 119–36.

48To cite just one example, the tenth-century ruler Rajendravarman was said to have fought “like Rama” in his campaigns against the “powerful and evil” Mon and Cham rulers, shooting arrows in every direction; Inscription K872 from Prasat Ben Vien, in George Coedès (ed.), Inscriptions du Cambodge, vol. 5 (Paris: Éditions de Boccard, 1950), p. 101.

49See, for example, the discussion of the Burmese Konbaung ruler’s stated justification for invading Arakan in 1784–85 in Jacques Leider, “Politics of Integration and Cultures of Resistance: A Study of Burma’s Conquest and Administration of Arakan (1785–1825),” paper presented at the Workshop on Asian Expansions: The Historical Processes of Polity Expansion in Asia, Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, 2006.