Chapter II.6.3

Tissue Engineering Scaffolds

In the search for alternatives to conventional treatment strategies for the repair or replacement of missing or malfunctioning human tissues and organs, promising solutions have been explored through tissue engineering approaches (Langer and Vacanti, 1993). Biomaterials-based scaffolds have played a pivotal role in this quest. The fundamental purpose of a tissue engineering scaffold is to act as a three-dimensional template that may provide mechanical stability, deliver therapeutic agents, and facilitate processes critical in tissue repair, such as tissue induction, cell proliferation and differentiation, and/or guided tissue growth. To date, a wide variety of biomaterials have been explored for application as tissue engineering scaffolds, including metal-based implants, purified extracellular matrix (ECM) xenografts, ceramics, and natural and synthetic polymers. Bioresorbable synthetic polymers are particularly attractive for two main reasons. First, they degrade into products that can be safely metabolized and/or excreted, potentially leaving no residual foreign materials in the recipient, and second they are highly versatile with regard to the control over their physicochemical properties and ease of processability, allowing them to be tailored in an application-specific manner. This chapter provides an overview of bioresorbable synthetic polymeric scaffolds for tissue engineering applications.

Scaffold Design

When designing a polymeric scaffold, a combination of biological and engineering requisites is considered in an application-specific manner. One of the most essential design elements is the biocompatibility of the scaffolds, implying that the scaffold should not demonstrate immunogenicity or elicit an adverse inflammatory response (Babensee et al., 2000). In this regard, the bioresorbable scaffolds should also be sterilizable, and should degrade without significant cytotoxic, inflammatory or immunogenic degradation components. In addition, scaffold design considerations include suitable bulk properties, and the presentation of microenvironments to regulate cell adhesion, spreading, motility, survival, and differentiation.

For anchorage-dependent cells, cell-to-scaffold interactions need to be optimized. Cell-to-scaffold interactions have a direct impact on cell adhesion and morphology, which may in turn affect various cellular processes. These interactions are directly or indirectly influenced by physicochemical characteristics of the polymer surface, including features such as wettability (hydrophilicity), roughness, crystallinity, charge, and functionality (for reviews, see Ruardy et al., 1997; Singh et al., 2008a).

Synthetic polymer surfaces are usually devoid of specific ligands that cell surface receptors recognize, so modification with extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules is often applied to improve cell-to-scaffold interactions (Kraehenbuehl et al., 2008; Weber and Anseth, 2008). The ECM molecules are known to play important roles in integrin-mediated signaling and associated cellular functions (Howe et al., 1998). For this purpose, the presence of pendant functional groups on polymer chains is desirable, because these may be used to conjugate proteins or peptides. In some cases, specific surface functionalities may directly influence the desired cellular activity and function, precluding the need for ECM molecules. For example, it was recently shown that small molecules of specific functionalities (charged phosphate group and hydrophobic t-butyl group) tethered to a poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydrogel can induce osteogenesis and adipogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells in the absence of any cytokine (Benoit et al., 2008).

Substrate rigidity is another important factor that determines cell cytoskeletal shape and associated cellular function (see review by Discher et al., 2005). In general, increased cell adhesion and spreading leads to cell proliferation, while moderate cell adhesion and a rounded cell morphology corresponds to differentiated cellular function (Mooney et al., 1992), and substrate stiffness is known to affect the extent of cell spreading. For example, fibroblasts cultured on soft two-dimensional polyacrylamide substrates (substrate stiffness 14 kPa) display a rounded morphology compared to the cells cultured on stiffer substrates (substrate stiffness 30 kPa), which adopt a flat morphology (Lo et al., 2000). Usually, substrate stiffness similar to the native tissue yields a cellular phenotype similar to that tissue. Another polymer property that impacts cell–scaffold interactions is dimensionality and overall architecture. When compared to two-dimensional environments, a three-dimensional environment has been shown to lead to reduced cell adhesion to the substrate (Cukierman et al., 2001). In addition to impacting individual cell behavior, a three-dimensional environment also facilitates formation of a larger number of cell–cell contacts, allowing for cellular interactions that are often vital in tissue remodeling processes. A three-dimensional scaffold of the shape of native tissue is also desired, to define and guide the ultimate shape of the regenerated tissue.

Porosity, pore size, and interconnectivity of pores are morphological characteristics of scaffolds that have a direct influence on the cell-to-cell interactions, the surface area-to-volume ratio, and mass transport processes critical for cell survival. A high porosity is desirable to maximize the possible accommodation of cell mass and vascular infiltration; however, high porosity values often compromise the mechanical properties of the scaffold (Karageorgiou and Kaplan, 2005). Pore size is another important factor to consider, because it is known to influence the cellular infiltration, cell-to-cell interaction, and transport of nutrients and metabolites (Mikos et al., 1993c). For a given porosity, smaller pore sizes lead to an increased surface area-to-volume ratio, resulting in a larger area available for cell attachment. The minimum pore size that will allow cellular infiltration, either during initial seeding or through cellular proliferation and migration, is dependent on cell size (roughly 10 μm); however, optimal pore sizes are almost always larger, and are dependent on the topological features of the scaffold. Moreover, pore sizes can also be controlled in order to facilitate the process of vascularization, and to reduce fibrotic tissue formation (Ratner, 2007). Recently, it was shown that monodisperse pore sizes of ~35 μm in poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (PHEMA) scaffolds resulted in an improvement of the vascularization of the implants and a reduction in fibrotic tissue formation compared to ~20 μm or ~70 μm pore sizes for soft tissue regeneration (Marshall et al., 2004a,b). In addition to optimization of pore size and porosity, the geometry of the pore network must also be considered. An interconnected pore network is desired in order to minimize inaccessible pore volume, and the tortuosity of this network is an important determinant of mass transport rates. Pore geometries may also critically affect cellular organization in the scaffolds (Ma and Zhang, 2001; Zmora et al., 2002). For example, pores in the form of tubular guidance channels have been widely utilized to promote directed neurite growth.

One of the major engineering considerations in tissue regeneration is the mechanical stability of bioresorbable scaffolds. Usually, the mechanical properties of the scaffolds are required to be similar to the native tissue. A weak structure may not be able to withstand the biomechanical forces encountered in vivo, whereas a stiffer scaffold may lead to stress shielding, a phenomenon where transfer of physical load to the scaffold leads to insufficient mechanical stimulation of tissues surrounding the implant. In addition, due to the degradation of bioresorbable polymeric scaffolds, their mechanical properties change as a function of time, so control over the degradation of tissue engineering scaffolds is a highly desired feature. Degradation of polymeric scaffolds is dependent on several parameters, as listed in Table II.6.3.1 (also see Chapters I.2.6 and II.4.3). Polymers also differ in the mechanism through which they degrade, e.g., surface erosion, bulk erosion, enzymatic action. Ideally, the tissue–polymer construct should provide sufficient mechanical stability consistently throughout the process of reconstruction. In addition, the degradation rate determines the available space for tissue growth and implant integration with the host tissue. In an optimal scenario, the degradation rate of the scaffolds and the rate of tissue formation should be matched to provide consistent structural and mechanical stability to the transplant.

TABLE II.6.3.1 Important Factors that Influence Scaffold Degradation

Another important consideration when designing a scaffold for any tissue engineering application is the selection of a suitable material with desired characteristics, which is discussed in the following section.

Scaffold Materials

Material selection for tissue engineering applications is based on several important factors including biocompatibility, surface characteristics, degradability, processability, and mechanical properties (see review by Thomson et al., 1995a). Synthetic bioresorbable polymers constitute a set of polymers that provide extreme versatility with regard to control over their physicochemical properties, and are generally easy to process into tissue engineering scaffolds. Synthesis of these polymers can be tailored to yield a specific molecular weight, chemical structure, end group chemistry, and composition (homopolymers, copolymers, and polymer blends).

A range of bioresorbable polymers have been explored for potential application in tissue engineering (for reviews, see Babensee et al., 1998; Gunatillake and Adhikari, 2003; Martina and Hutmacher, 2007) (Table II.6.3.2) (Chapter I.2.6). Among these, polyesters have been most widely investigated. Poly(α-hydroxy esters) (such as poly(lactic acid) (PLA), poly(glycolic acid) (PGA), and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)) have attracted extensive attention for a variety of biomedical applications. The ease of processability of these polymers into various shapes is a major advantage. However, there is a known concern that their degradation products may lead to a drop in local pH, creating an acidic environment that may harm cells and tissues. Moreover, the degradation products may also catalyze the degradation of these polymers, resulting in different degradation rates depending on the removal of these products (Li et al., 1990). Copolymers that combine poly(α-hydroxy esters) with amino acids, such as block copolymers of poly(lysine-co-lactic acid), have been produced that allow the addition of cell adhesion peptides to lysine groups (Cook et al., 1997). Another important class of polyesters are polylactones, among which poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) has been the most utilized as a tissue engineering scaffold. Blends and block copolymers of PCL with other poly(α-hydroxy esters) (such as poly(L-lactic acid-co-ε-caprolactone) (PLLACL) or poly(D,L-lactic acid-co-ε-caprolactone) (PDLLACL)) have been used to produce polymers with tailored properties, such as degradation rate. Polydioxanone is a bioresorbable poly(ether-ester), which has been used in fiber forms for fixation and other applications (Boland et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2008). Poly(propylene fumarate) (PPF), an unsaturated linear polyester based upon fumaric acid, has also been explored as part of an injectable formulation in tissue engineering applications (Timmer et al., 2003a,b). Cross-linking agents and initiation mechanisms (photoinitiation or thermal initiation) can be altered to form PPF networks of desired properties (Peter et al., 1999; He et al., 2000; Fisher et al., 2002a). Several composites and copolymers of PPF have been developed and investigated, mainly for bone tissue engineering and drug delivery applications.

TABLE II.6.3.2 Scaffold Materials, and Example Applicationsa

aPartially adapted and reproduced with permisson from Gunatillake and Adhikari (2003), and Martina and Hutmacher (2007).

To increase wettability, biocompatibility, and/or softness of bioresorbable polymers, blends and copolymers with non-degradable poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) have been developed, such as block copolymers of PEG with PLLA, PLGA, and PCL (for reviews, see Hoffman, 2002; Baroli, 2007). Injectable, in situ forming hydrogels based on PEG, such as oligo[poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate] (OPF), have also been developed and investigated. An OPF-based hydrogel is biodegradable and demonstrates a high degree of swelling (Jo et al., 2001; Temenoff et al., 2002, 2003). These hydrogels have been recently investigated for bone, cartilage, and osteochondral tissue engineering applications (Shin et al., 2003; Holland et al., 2005; Kasper et al., 2006; Guo et al., 2009).

In addition to those derived from polyesters, a number of bioresorbable materials have been developed from various other polymer families. Many amorphous and soluble pseudo-poly(amino acids) (amino acids linked by both amide and non-amide bonds) have been processed into tissue engineering scaffolds, such as polycarbonates and polyacrylates. Polyanhydrides and poly(anhydrides-co-imides) have been vastly studied for drug delivery, and for use as hard tissue substitutes (Gunatillake and Adhikari, 2003). Degradable polyurethanes and their copolymers have been investigated for skin and other soft tissue engineering and replacement applications (Bruin et al., 1990; Spaans et al., 2000). Polyorthoesters have been used in bone tissue engineering and drug delivery (Andriano et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2004; Nguyen et al., 2008), and lastly, polyphosphates and polyphosphazenes have been mainly used in scaffolds for bone tissue engineering applications (Brown et al., 2008a; Nukavarapu et al., 2008; Deng et al., 2010).

To summarize, a wide variety of synthetic bioresorbable polymers have been investigated for their potential application in tissue engineering. Material selection is a critical factor of the scaffold design for an intended tissue engineering application. The following section briefly discusses a few established strategies for scaffold-assisted tissue regeneration.

Applications of Scaffolds

Tissue Induction

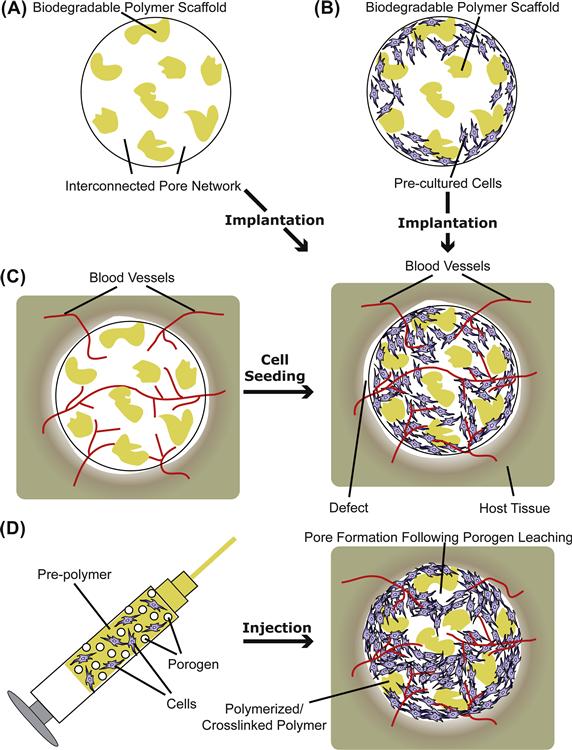

After implantation, a porous acellular three-dimensional scaffold can act as a substrate to allow infiltration and ingrowth of the surrounding host tissue, a process known as tissue induction (Figure II.6.3.1A). For instance, an osteoinductive material has the property of promoting pre-osteoblast infiltration and bone induction. Tissue induction is commonly marked by events of host cell migration, proliferation, and differentiation, as well as vascularization. This scaffold-based approach has the potential of offering an “off-the-shelf” solution for defect repair in the form of implantable acellular devices. The selection of a material and scaffold design (such as pore size and porosity), however, are important factors that can affect the selectivity and extent of tissue induction. Regeneration of various tissues including skin, bone, ligament, and nerve has been investigated using this approach.

FIGURE II.6.3.1 Polymeric scaffolds in tissue engineering applied in prefabricated (A–C) or injectable form (D). Specific applications of prefabricated scaffolds: (A) tissue induction; (B) cell transplantation; and (C) prevascularization.

Cell Transplantation

Cell transplantation is a sub-class of cell-based therapies, where cells placed on a two-dimensional or in a three-dimensional polymeric scaffold facilitate the repair or regeneration of damaged tissue. In this approach, cells obtained from a donor site in a patient are harvested, expanded in culture, seeded onto an appropriate scaffold, and then transplanted to the defect site (Cima et al., 1991; Bancroft and Mikos, 2002) (Figure II.6.3.1B). In most practices, the cells are allowed to attach to the construct, and are cultured for a period of time to allow them to proliferate and/or differentiate before implantation. When using cell transplantation, an appropriate choice of material that favors the attachment and growth of seeded cells and integration of the transplant with the host tissue is critical. Using this approach, transplantation of a variety of differentiated cell types including osteoblasts, chondrocytes, fibroblasts, hepatocytes, and smooth muscle cells has been pursued. Due to the donor site morbidity often associated with the harvest of differentiated cells, transplantation of undifferentiated or pre-differentiated autologous adult stem cells (such as mesenchymal stem cells) has also been investigated. When engineering heterogeneous interfacial structures, a cell transplantation approach can be used to design multiphasic scaffolds containing more than one cell type regionalized spatially into the different phases of the scaffold along its axis (Cao et al., 2003; Schek et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2006; Spalazzi et al., 2008). Recently, a multilayered scaffold design has also been applied for pancreatic islet encapsulation in PEG-based hydrogels, where an additional outer layer serves as an immunoprotective barrier to minimize graft–host interaction (Weber et al., 2008). By using genetically modified cells that are programmed to produce desired bioactive factors at the site of interest, this approach also offers the possibility of simultaneous in situ delivery of cells and bioactive factors that may enhance the tissue regeneration process (Gilbert et al., 1993; Blum et al., 2003).

Prevascularization

Nutrient diffusion in a scaffold is generally restricted to a few hundred micrometers from the scaffold edge, which imposes one of the major challenges for the regeneration of large three-dimensional organs, such as the liver (Mooney and Mikos, 1999). Development of bioreactor technology has imparted the ability to grow large constructs in vitro, as discussed later. However, most of the cultured cells do not survive when implanted in vivo without their own blood vessels to supply nutrients and oxygen (Mooney and Mikos, 1999). Post-implantation scaffold vascularization may take place, but the rate may not be sufficient to prevent cell death and tissue necrosis, especially in the core of the scaffold. Bioactive factor delivery strategies (discussed later) have been utilized to expedite the vascularization process in polymeric scaffolds via the delivery of angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) (Lee et al., 2002; Peattie et al., 2006; Patel et al., 2008), or by delivering gene expression vectors (e.g., plasmid DNA) that may allow the cells to produce such angiogenic factors in situ (Geiger et al., 2005). Co-culture of endothelial or progenitor cells with the cells of interest is another avenue of research to induce vascularization in the engineered tissue in vitro (see review by Lovett et al., 2009), which may help in the generation of a vascular network early after implantation. To promote sufficient vascularization of the implants, an alternate and effective strategy is to prevascularize a porous scaffold by first implanting it in a highly vascular site where the ingrowth of fibrovascular tissue or vascular tissue may take place by tissue infiltration. These prevascularized implants can then be seeded with cells and transplanted to the site of interest (Figure II.6.3.1C). Scaffold properties (such as pore size and morphology) are important factors that influence the extent of prevascularization, and determine the availability of space for cell seeding and tissue infiltration in the prevascularized implant (Mikos et al., 1993c). Apart from the regeneration of large organs, this strategy has also been applied for the treatment of critical-sized osseous defects. Prevascularized bone flaps were fabricated via ectopic bone formation by suturing an open chamber containing a mixture of a bioresorbable polymer and osteoinductive morcellized bone graft onto the cambium layer of the periosteum at a location remote from the defect site (Thomson et al., 1999), which may then be transplanted to the defect site and anastomosed to the host vasculature via microsurgery. An associated limitation of the prevascularization approach is that it requires multiple surgical procedures.

Injectable Systems for Minimally Invasive Tissue Engineering

In situ cross-linking biomaterials consist of space-filling injectable precursors, which solidify by cross-linking in the defect site (Figure II.6.3.1D). One method of classifying in situ cross-linking materials is based on the initiation mechanism of cross-linking, e.g., thermal initiation (such as PPF and OPF), photoinitiation (such as PEG-diacrylate (PEG-DA) or PPF), and ionic interaction (such as alginate or charged PLGA nanoparticulates) (for reviews see Hou et al., 2004; Kretlow et al., 2007; Van Tomme et al., 2008). Thermogelling polymers also fall under the category of injectable polymers; however, they undergo gelation by virtue of physical transition upon a sufficient temperature change (such as copolymers of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) or poly(ethylene oxide-b-propylene oxide-b-ethylene oxide)) (Ruel-Gariepy and Leroux, 2004). One of the major advantages of in situ cross-linking materials is that they can be administered in a minimally invasive manner. Moreover, they also lend themselves to drug and cell delivery purposes, which can be achieved, under proper conditions of solidification, by simple mixing of cells and/or bioactive factors in the precursor solution (Kretlow et al., 2007). However, there are several additional design criteria that must be met, such as cytocompatibility of all the constituents, suitable rheological properties of the precursor solution, curing time, and polymerization conditions (e.g., temperature, pH, duration of exposure to the initiating wavelength of light, and heat release) that do not negatively impact the implanted cells and the surrounding tissue (Hou et al., 2004).

To facilitate cellular infiltration and guided tissue growth, an in situ cross-linking three-dimensional scaffold can be made highly porous via several methods, including particulate leaching or gas foaming (discussed later) (Peter et al., 1998; Behravesh et al., 2002). Since increased porosities usually lead to a reduction in mechanical properties, the mechanical properties of such materials can be tailored in an application-specific manner by either inclusion of micro- or nanophase materials that provide mechanical reinforcement or by varying the cross-linking mechanism, cross-linking agent, and/or cross-linking density (Timmer et al., 2003b; Shi et al., 2006). However, changes in the precursors or reaction/gelation conditions must be made so as to avoid any adverse reaction on the implanted cells or surrounding tissue. For example, an excessive concentration of the porogen salts, leachable components or cross-linking agents may not be suitable for implanted cells or surrounding host cells. In such cases, an alternate strategy of cell transplantation has been developed, where cells are encapsulated in a cytocompatible environment (in this case, gelatin microspheres) that is then included in the precursor solution to form a composite material (Payne et al., 2002a,b). Similar strategies have been widely applied for the delivery of bioactive factors, where bioresorbable micro- or nanoparticles loaded with bioactive agents can be included in the precursor solution to support sustained temporal release, as discussed in the following section.

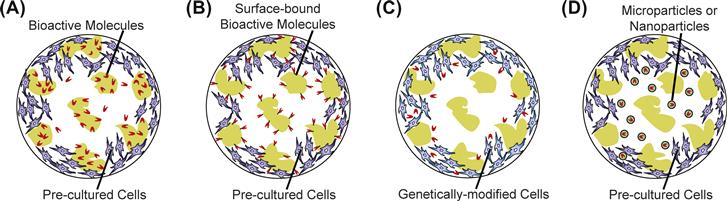

Delivery of Bioactive Molecules

Bioactive molecules comprise many soluble molecules, including growth factors, angiogenic factors, cytokines, hormones, DNA, siRNA, and immunosuppressant drugs, which interact with and modulate the activity of a cell (Holland and Mikos, 2003; Kasper and Mikos, 2004). For instance, early in embryonic development, the fate of the uncommitted cells towards the formation of tissue patterns is governed by the spatiotemporal expression of specific signaling molecules, referred to as morphogens (Gurdon and Bourillot, 2001). Delivery of bioactive molecules is often desirable to induce tissue formation and/or selectively modulate various cellular activities, such as cell proliferation, differentiation or ECM production. For example, bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) constitute a family of proteins that have been exploited to enhance osteogenesis by bone cells (Cheng et al., 2003). In vitro, these bioactive factors are usually delivered in their soluble forms via the cell culture media. However, to administer such tissue inducing factors in vivo locally in a controlled manner, the concept of incorporating these factors into tissue engineering scaffolds has evolved. One approach is to deliver the bioactive factors directly from the supporting matrix (Figure II.6.3.2A). Another approach is to bind these molecules to the substrate surface at the time of scaffold processing (Figure II.6.3.2B). One of the most widely used examples is the use of cell adhesion molecules (such as RGD and YIGSR peptide sequences) covalently linked to the scaffold that provide attachment sites for anchorage dependent cells (see review by Hersel et al., 2003). Similarly, many growth and differentiation factors lead to an increase in desired cellular responses when they are linked covalently to the polymer substrate, as compared to the soluble forms (Hubbell, 2007). For example, recently it was shown that survival of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), osteogenic colony formation of human bone marrow aspirates, and osteogenic differentiation of MSCs were all enhanced in the presence of epidermal growth factor (EGF) covalently attached to the substrate, as compared to the soluble EGF (Fan et al., 2007; Marcantonio et al., 2009; Platt et al., 2009). Alternatively, bioactive factors can be produced in situ using genetically modified cells seeded in the scaffold matrix that produce bioactive factors locally at the site of interest (Gilbert et al., 1993; Blum et al., 2003; Macdonald et al., 2007) (Figure II.6.3.2C). To achieve temporal control over the release of the bioactive factors (e.g., a sustained release over a desired period) in the scaffold, these molecules can be loaded in a carrier, such as bioresorbable micro- or nanoparticles (Figure II.6.3.2D) (Hedberg et al., 2002; Panyam and Labhasetwar, 2003; Kasper et al., 2005). More recently, lipid-based microtubular devices have also been explored as carriers for the delivery of plasmid DNA and growth factors (Meilander et al., 2003; Jain et al., 2006; Johnson et al., 2009). The release of bioactive factors from the carrier in vivo can be a function of many factors, such as molecular diffusion, degradation rate, and local enzyme concentration and activity (for polymers such as gelatin, a naturally derived polymer that degrades through enzymatic action) (Hedberg et al., 2002; Johnson et al., 2009). Depending on the application, the aforementioned delivery strategies also lend themselves to the delivery of multiple growth factors with desired release profiles (Richardson et al., 2001). For example, to explore the synergistic effects of simultaneous delivery of angiogenic and osteogenic proteins, dual growth factor delivery of VEGF and BMP-2 via a scaffold was achieved using acidic and basic gelatin microspheres as carriers, respectively (Patel et al., 2008). Spatial control over the expression of bioactive factors within a scaffold is desirable for the engineering of heterogeneous tissue structures (such as osteochondral tissue). For such applications, spatial patterning of bioactive factors at the time of scaffold processing is possible (Holland et al., 2005, 2007; Guo et al., 2009). Many such heterogeneous scaffold designs with biphasic, multiphasic or graded distribution of bioactive agents are currently under investigation, with the intention of controlling the spatiotemporal release of single or multiple growth factors.

FIGURE II.6.3.2 Localized delivery of bioactive factors. (A) Bioactive factors released directly from a scaffold. (B) Bioactive factors chemically conjugated to the surface of a scaffold. (C) Localized production of bioactive agents by genetically modified cells seeded in a scaffold. (D) Controlled delivery of bioactive factors from a carrier (such as microparticles or nanoparticles) dispersed within the porosity of a scaffold.

In summary, the basic function of a tissue engineering scaffold is to provide a three-dimensional environment for tissue growth. Addition of other features to a scaffold (e.g., drug carrying ability or injectibility) imparts another degree of functionality to the scaffold that makes it more suitable for certain applications. In the following section, an overview of general scaffold fabrication techniques is provided.

Scaffold Processing Techniques

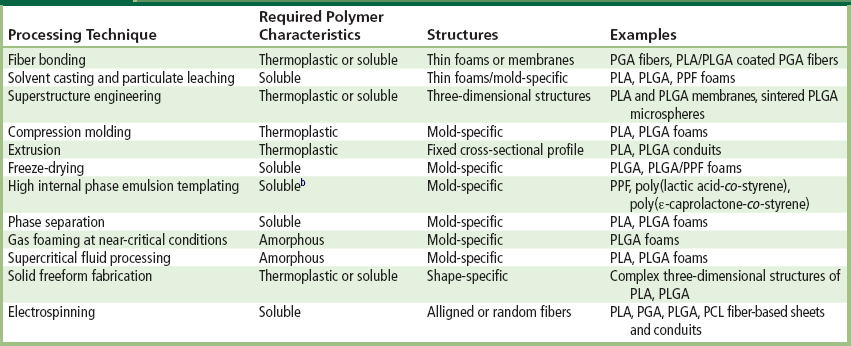

Various manufacturing methodologies have been developed to form porous three-dimensional substrates. In each of these techniques, one or more bioresorbable polymers of desired characteristics are processed uniquely to produce porous three-dimensional structures of particular shapes and morphologies (Hutmacher, 2000) (Table II.6.3.3). Polymer processing steps usually involve: (1) heat-assisted fusion/melting of the polymers above their glass transition or melting temperatures; (2) dissolution in organic solvents; (3) treatment with gases or supercritical fluids under high pressure; and/or (4) porogen (such as salt crystals, soluble microspheres or wax) leaching. Scaffold shape and morphology, mechanical properties, and biocompatibility are greatly influenced by the choice of scaffold processing technique. A majority of these techniques allow for the incorporation of bioactive molecules into the polymer matrix. However, due to exposure to harsh chemical and thermal environments, retention of the bioactivity for sustained drug release has been a significant challenge. In the following sections, some established scaffold fabrication techniques are presented.

TABLE II.6.3.3 Fabrication Techniques for Three-Dimensional Scaffold Production, Required Polymer Characteristics, Geometry Produced, and Example Materials Processeda

aAdapted with permission from Hutmacher (2010).

Fiber Bonding

Fiber-based technologies for scaffold fabrication have been very appealing, due to the large surface area-to-volume ratio that they provide, their early commercial availability, and the ease of fabrication of the fibers by industrial processes (such as hot drawing) (Freed et al., 1994). PGA fiber-based tassels and felts were some of the earliest constructs produced for organ regeneration purposes (Vacanti et al., 1991). However, the mechanical instability of such structures imposed a limitation on their in vivo application. To address this issue, a method was developed to fabricate bonded fiber networks of high porosities (up to 81%) (Mikos et al., 1993a). With this method, a non-bonded PGA fiber mesh is immersed in a PLA solution in methylene chloride. Following the evaporation of the organic solvent, the PLA–PGA composite is heated above the melting temperature of PGA. PGA fibers melt and bond with other PGA fibers at their contact points, while the molten PLA provides a structural casing around the fibers that prevents them from collapsing. PLA is finally removed by selective dissolution in methylene chloride, leaving the PGA fibers in an interlocked structure. Due to the specificity of the fiber bonding method with regard to the two polymers selected (they must be immiscible with appropriate relative melting temperatures) and to the solvent, the general use of this technique is precluded.

An alternate method of fiber bonding has also been developed, where PGA fibers are bonded by spray casting an atomized solution of PLA or PLGA in chloroform over the PGA fiber mesh placed on a rotating Teflon® mold (Mooney et al., 1996b). The PGA fibers are coated with a thin layer of sprayed polymer, which bonds the fibers at their cross-points. Solvent evaporation results in the formation of a thin tubular conduit made of bonded fibers. Such conduits were shown to support fibrovascular tissue in-growth following implantation (Mooney et al., 1996b). This fabrication technique, although useful for the preparation of thin fiber matrices, does not generally allow for the creation of complex three-dimensional structures. With the advent of computerized scaffold fabrication methodologies, complex fiber-based structures have now been created using solid freeform fabrication techniques, such as fused deposition modeling, as discussed later.

Solvent Casting/Particulate Leaching

Some of the drawbacks of fiber bonding techniques were addressed by the development of a new method, a solvent casting and particulate leaching (SC/PL) technique, which provides desired control over the porosity, pore size, surface area-to-volume ratio, and crystallinity of the prepared porous scaffolds (Mikos et al., 1994b). In an example of this method, sieved salt particles are dispersed in a solution of PLA dissolved in chloroform, which is used to cast a membrane on a platform (such as a glass petri dish). Following solvent evaporation, the dry polymer–salt composite is heated above the melting point of the polymer, then annealed or quenched at controlled cooling rates to produce a semicrystalline or amorphous polymer composite. The composites are then placed in water to leach out the salt particles, and subsequent drying yields polymer membranes that are highly porous. Regulation of the porogen-to-polymer weight ratio, porogen size, and cooling rate during the annealing/quenching step provides independent control over the production of scaffolds with desired porosity, pore sizes, and crystallinity, respectively. For example, PLA membranes fabricated using the SC/PL technique demonstrated porosities up to 93%, and median pore diameters up to 500 μm (Mikos et al., 1994b). Scaffolds produced using the SC/PL technique have been shown to support cell attachment and growth in vitro, as well as in vivo (Ishaug-Riley et al., 1997, 1998).

While the SC/PL technique is simple and inexpensive, extensive use of organic solvents during fabrication limits the possibility of using these matrices as carriers of specific bioactive agents. Moreover, the method is restricted to producing brittle thin membranes (up to 3 mm) (Wake et al., 1996). In one variation, blending of PEG with PLGA for the SC/PL technique resulted in an improvement in the pliability of the resulting membranes (Wake et al., 1996). In another method, thick scaffolds were constructed using particulate hydrocarbon wax as a porogen (Shastri et al., 2000). In this case, a mixture of viscous polymer solution and porogen is placed in a Teflon® mold. A hydrocarbon solvent (such as pentane or hexane) treatment is then used for selective extraction of the porogen from the mold, leaving a porous polymer foam matrix. PLA- and PLGA-based scaffolds fabricated using this method demonstrated porosities up to 87% and pore sizes above 100 μm, and this process supports the construction of thick shape-specific scaffolds.

In general, the SC/PL technique can be extended to any bioresorbable polymer that is soluble in an appropriate solvent (e.g., methylene chloride or chloroform), such as PLA or PLGA. In addition, a modified method of thermal cross-linking/particulate leaching has also been applied for cross-linkable polymers such as PPF. For example, by cross-linking the PPF in the presence of salt particles that are eventually leached in water, PPF scaffolds with porosities up to 75% and pore sizes in the range of 300–800 μm were prepared (Fisher et al., 2003). These scaffolds can be processed to allow for the incorporation of bioactive factors, and have been investigated for in vivo use in soft and hard tissue replacements (Fisher et al., 2002b; Hedberg et al., 2002, 2005). In addition, by incorporating another material phase (such as β-tricalcium phosphate or single-walled carbon nanotubes) in the scaffold design, reinforced porous PPF-based composite scaffolds can also be constructed to yield improved mechanical characteristics (Peter et al., 1997; Shi et al., 2005).

Superstructure Engineering

Superstructure refers to a three-dimensional structure made of superimposed two-dimensional structural elements such as fibers, pores or microspheres, which are ordered in a periodic, stochastic or fractal pattern (Wintermantel et al., 1996). Both individual elements and the pattern of organization determine the characteristics of the scaffold. Stable superstructures can be created from reproducible individual elements, the coherence of which determines the anisotropic structural behavior of the constructs (Wintermantel et al., 1996). An example of a superstructure is a three-dimensional structure produced by multiple stacked membranes fabricated using a membrane lamination process (Mikos et al., 1993b). In this method, individual membranes prepared by a SC/PL method are bonded together using chloroform on their contact surface to yield a shape-specific three-dimensional structure. Periodic arrangement of polymer microspheres is another simple example of a superstructure made of microspheres as the structural element. Recently, a variety of methods have been employed to produce polymer microsphere-based scaffolds by sintering the microspheres packed in a mold (Borden et al., 2004; Brown et al., 2008a; Jaklenec et al., 2008; Singh et al., 2008b, 2010). Here, the size of the microspheres and their packing configuration determines the coherence of the structure. For example, monodisperse microspheres in a cubic lattice yield a stable isotropic structure.

Compression Molding

Compression molding is a scaffold fabrication technique used with thermoplastic polymers. In an example of the compression molding technique, PLGA powder is mixed with gelatin microparticles and loaded in a Teflon® mold (Thomson et al., 1995b). The mixture is heated above the glass transition temperature of the amorphous polymer, while being compressed under a constant force. The composite is then removed from the mold, and the embedded gelatin is leached out in water. Porosity and pore sizes of the PLGA scaffolds thus produced can be varied selectively by altering the initial gelatin loading and gelatin microsphere size, respectively. This method avoids the use of any organic solvents, and may allow for the incorporation of bioactive factors in the polymer or porogen phase when performed at relatively low temperatures. By changing the mold geometry, it is also possible to prepare shape-specific scaffolds.

Several variations of compression molding exist. To extend the application of this process to bioresorbable semicrystalline polymers, such as PLA or PGA, a similar compression molding method has been use in which the mixture of polymer and porogen is heated above the melting temperature of the polymer. Melt-based compression molding has also been widely applied to create blends of polymers. Retention of the biological activity of bioactive factors at such elevated temperatures, however, is difficult. In another variation, compression molding can be applied together with the SC/PL technique to fabricate porous three-dimensional foams. In this method, solid pieces of polymer–salt composites are obtained by drying the cast polymer–salt solution or by coagulating it in an anti-solvent (Widmer et al., 1998; Hou et al., 2003). Particulate polymer–salt composites (<5 mm edge length) can then be compression molded, and subsequent salt leaching results in an open-cell foamed three-dimensional porous scaffold. This method has been shown to result in a relatively homogeneous pore morphology compared to the SC/PL method. Compared to the compression molding method, the SC/compression molding/PL method also offers the possibility of fabricating composites with another solid phase homogeneously distributed in the foamed three-dimensional structure. Using this method, foamed three-dimensional scaffolds reinforced homogeneously with osteoconductive hydroxyapatite microfibers were produced, and these demonstrated superior compressive strength compared to non-reinforced scaffolds of the same porosity within a certain range of polymer-to-fiber ratios (Thomson et al., 1998). Such a variation in scaffold fabrication is favorable for bone tissue engineering applications, because both incorporation of osteoconductive elements and improvement in mechanical properties are desired characteristics.

Extrusion

Extrusion is a well-known process applied to form objects of a predefined fixed cross-section; it has been used to process thermoplastic bioresorbable polymers for three-dimensional scaffold fabrication with macroscale cross-sectional areas (>1 mm). Processing of polymers using various extrusion methods, such as solid-state extrusion (die drawing), cylinder-piston (ram) extrusion or hydrostatic extrusion, generally changes the polymer chain orientation, leading to increases in their strength and modulus of elasticity (Ferguson et al., 1996). Using a mixture of polymer powders, extrusion methods can be readily applied to create solid blends of polymers. To create porous scaffolds, an SC/melt–extrusion/PL technique has been developed (Widmer et al., 1998). Dry polymer–salt composites produced by SC are cut into pieces (<5 mm edge length) and placed in a custom piston extrusion tool connected to a hydraulic press. The polymer is heated to the desired processing temperatures and equilibrated, then extruded by applying pressure using the hydraulic press to produce tubular constructs. Constructs of desired length are cut from the tube, and are then placed in water for salt leaching. Porous tubular conduits thus produced have been used for guided tissue engineering applications, including peripheral nerve regeneration (Evans et al., 2002). As with the SC/PL techniques, porogen-to-polymer weight ratio and porogen size can be selectively altered to produce scaffolds of desired porosity and pore sizes, respectively. In addition, processing temperature is another important variable that influences the pressure required for extrusion, and can influence the scaffold morphology and thermal degradation of the scaffold.

Freeze-Drying

Freeze-drying is a simple approach for polymer foam fabrication. The polymer is dissolved in a solvent such as benzene or glacial acetic acid, then frozen and lyophilized under high vacuum to remove the dispersed solvent (Hsu et al., 1997). Depending on the polymer–solvent system used, the resulting scaffolds demonstrate leaflet or capillary-like microfeatures. Several materials, including PLA, PLGA, and PLGA/PPF, have been used to fabricate polymer foam scaffolds using this method (Hsu et al., 1997). These scaffolds usually have a random pore structure and network. Due to their low density and pore connectivity, further processing, such as grinding and extrusion, is usually required to fabricate matrices useful for application.

An emulsion freeze-drying method is very similar to the freeze-drying approach; however, it involves the formation of an emulsion (Whang et al., 1995). The polymer is first dissolved in a solvent; then water is added to form a water-in-oil emulsion. The polymer is subsequently quenched in liquid nitrogen and freeze-dried to remove the dispersed water and solvent. Important process parameters include the polymer–solvent system, molecular weight of the polymer, polymer solution-to-water ratio, and emulsion viscosity. Using this technique, PLGA (methylene chloride as solvent) and PLA (dioxane as solvent) scaffolds with porosities greater than 90% have been prepared (Whang et al., 1995; Hu et al., 2002). Compared to the SC/PL technique, the emulsion freeze-drying method produces foams with a lower median pore diameter and higher specific pore surface area.

Another class of emulsion-derived porous polymeric foams known as polyHIPEs (Barby and Haq, 1982) are formed by a high internal phase emulsion templating method (see review by Cameron, 2005). A high internal phase emulsion (HIPE) consists of a monomer (external) phase and a droplet (internal) phase, and is defined by a characteristic internal phase volume fraction of at least 0.74 (Lissant, 1974). In this method, the continuous macromer phase is first polymerized around a template of the droplet phase, and subsequent removal of the droplet phase results in the formation of a porous polyHIPE. Many polyHIPEs have been recently investigated for their tissue engineering applications, including polyHIPEs based on PPF, poly(lactic acid-co-styrene), and poly(ε-caprolactone-co-styrene) (Busby et al., 2001, 2002; Christenson et al., 2007). Factors that govern pore size, pore interconnectivity, and porosity of the polyHIPEs include composition of the HIPE (e.g., composition and viscosity of the two phases, volume fraction of the droplet phase), the droplet radius, molecular weight of the macromer, and cross-linker density.

Phase Separation

In the thermally-induced liquid–liquid phase separation technique, the polymer is first dissolved in a solvent that has a low melting point and that can be easily sublimed (such as molten phenol, naphthalene or dioxane) (Lo et al., 1995; Nam and Park, 1999a,b). Lowering the solution temperature below the melting point of the solvent leads to liquid–liquid phase separation, and later quenching of the phase-separated solution creates a two-phase solid. Subsequent removal of the solvent via freeze-drying for several days results in a porous polymeric scaffold. There are several process variables that can affect the morphology of the scaffolds, including the polymer–solvent system, polymer concentration, molecular weight, and cooling rate. For example, this technique was used to prepare polymer foams with porosities greater than 90% and pore sizes close to 100 μm (Nam and Park, 1999a). This process also allows the incorporation of bioactive factors, which can be homogeneously mixed in the polymer solution before inducing phase separation (Nam and Park, 1999a). Depending on the choice of solvent, however, the bioactive factors may become denatured and lose some of their activity (Lo et al., 1995). More recently, phase separation has also been utilized to produce interconnected nanostructured networks (Chen and Ma, 2004; Yang et al., 2004). Using tetrahydrofuran as a solvent, PLA nanofibrous scaffolds were produced via phase separation with fibers in the range of 50–300 nm, and were shown to support neural stem cell differentiation and neurite outgrowth (Yang et al., 2004). It is, however, difficult to control the orientation of the fibers produced in such nanostructured networks (Murugan and Ramakrishna, 2007).

Gas Foaming and Supercritical Fluid Processing

Processing of many bioresorbable amorphous polymers with gases at ambient temperature and high (critical, near-critical or sub-critical) pressures has offered an alternative method for porous scaffold fabrication. Specifically, carbon dioxide (CO2) has been most widely used, as it is inexpensive, non-toxic, non-flammable, recoverable, and reusable. The polymer is first saturated with CO2 at high pressures in a vessel, which is followed by depressurization to ambient levels that results in nucleation of the gas, forming pores in the material. The amount of dissolved CO2, the rate and type of gas nucleation, and the rate of gas diffusion to the pore nuclei are factors that primarily determine the pore structure and porosity of the resulting scaffold. Application of gas foaming (GF) at near-critical pressures (5.5 MPa) has been shown to produce highly porous scaffolds (>90% porosity and around 100 μm pore size) from pre-processed solid PLGA discs (Mooney et al., 1996a), and the technique has also been shown to allow the retention and delivery of active growth factors (Sheridan et al., 2000). In contrast to gas foaming at near-critical conditions, supercritical CO2 (Tc = 304.1 K, Pc = 73.8 bar) absorbs into and liquifies many materials by lowering their glass transition temperatures (Jung and Perrut, 2001), and a supercritical fluid processing method has been used to incorporate bioactive factors and/or cells at the time of scaffold fabrication in a single step (Howdle et al., 2001; Ginty et al., 2006). Although these foaming techniques are advantageous over temperature-regulated or organic solvent-assisted scaffold fabrication for the incorporation of bioactive factors, an inherent limitation is the closed-cell structure and lack of pore interconnectivity. This problem was addressed by a modified technique of gas foaming/particulate leaching (GF/PL), where porogens (NaCl) included at the time of processing were leached out following gas foaming, resulting in an open pore structure of macropores (effected by porogen leaching), along with a non-interconnected microporous network (Harris et al., 1998; Murphy et al., 2000). The matrices produced demonstrate a relatively homogeneous pore structure, and higher mechanical strength than those fabricated with SC/PL.

In lieu of direct processing of polymers with CO2, on-site production of CO2 and foaming can be achieved using effervescent salts (Nam et al., 2000). For example, a combination of ascorbic acid, ammonium persulfate, and sodium bicarbonate was used to form highly porous hydrogels for bone tissue engineering (Behravesh et al., 2002), and these foams demonstrated excellent compatibility for marrow stromal cell differentiation and production of bone matrix in vitro (Behravesh and Mikos, 2003).

Solid Freeform Fabrication

Solid freeform fabrication (SFF), also known as rapid prototyping (RP), refers to a set of automated computer-assisted fabrication technologies, which have been utilized to produce porous three-dimensional scaffolds using bioresorbable materials. Examples of SFF techniques include three-dimensional printing (3DP), stereolithography, fused deposition modeling, selective laser sintering (SLS), and ballistic particle manufacturing. The underlying principle is analogous to a bottom-to-top approach, where mold-less creation of complex scaffolds is achieved by addition of materials to form cross-sectional levels in a layer-by-layer manner (obtained by computer-assisted design (CAD)), followed by layer fusion to yield a three-dimensional structure. These methods provide selective and precise spatial control over the scaffold morphology, including material composition, pore size, porosity, and microstructure. In addition, some technologies also offer the ability to pattern cells or bioactive molecules during the scaffold fabrication process.

SLS involves computerized laser scanning for the creation of patterned objects (Bartels et al., 1993). In SLS, a layer of polymer powder is first spread over a building platform. A desired two-dimensional profile is created by selectively scanning the polymer powder by an x–y controlled laser beam, which heats the polymer surface to or above its glass transition temperature. Upon cooling, the polymer particulates transition from a rubber to a glassy state, and fuse with the surrounding particulates. The layered scanning process is repeated with a fresh layer of polymer powder until the desired scaffold dimensions are met. Using this method, many bioresorbable materials have been processed into scaffolds, including PLLA, PCL, and PLGA, with or without a bioceramic component (Tan et al., 2003; Williams et al., 2005; Wiria et al., 2007; Simpson et al., 2008).

In stereolithography, computer-controlled movement of an ultraviolet laser is used to photopolymerize a liquid precursor solution in desired three-dimensional shapes. For example, a diethyl fumarate/PPF resin was used as a liquid base material in a custom-design stereolithography apparatus (Cooke et al., 2003). In a bottom-to-top manner, desired two-dimensional patterns of a fixed thickness (in this case, 100 μm) were created in the surface layer of the liquid resin over a building platform placed in a resin-filled tank. Sequential layers of 100 μm thickness were produced by lowering the stage in the tank by a fixed step-size of one layer, allowing the resin to cover the finished layer, and then exposing the fresh surface layer to UV. Both dimensions of the laser and resolution of the movement in the z-direction determine the overall resolution of the fabricated scaffolds. Using PEG-based photopolymerizable precursor solutions with cytocompatible photoinitiators, stereolithography has also been utilized to create fibroblast and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell-loaded three-dimensional hydrogel constructs (Dhariwala et al., 2004; Arcaute et al., 2006). In some variations of the stereolithography technique, photopatterning of a precursor can be performed by selective exposure to UV via a designed photomask, which can also allow precise pore or cell positioning within the fabricated constructs (Albrecht et al., 2005; Bryant et al., 2007).

The 3DP technique is an automated inkjet printing-based technology (Sachs et al., 1993). In 3DP technique, a layer of polymer powder is first spread over a building platform. Using the print head of an inkjet printer, a desired two-dimensional profile is created by depositing a binder material (e.g., an organic solvent) over this layer to selectively join the polymer powder. The building platform is lowered and the process is repeated with a fresh layer of powder placed over the last finished layer until the desired part is obtained. The unbound powder is finally removed to yield the desired three-dimensional scaffold. Spatial resolution of this technique (~50–250 μm) is dependent on several factors, such as the size of the polymer particulate/powder being used, the size of the printed droplet, and the resolution of the printhead movement. 3DP is performed at ambient temperature, and allows the integration of controlled release features (Wu et al., 1996). Various direct and modified 3DP techniques have been utilized to create composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering applications (Taboas et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2006; Ge et al., 2009).

Controlled dispensing methodologies have also been developed, where a polymer is deposited over a building platform in a layered fashion. The fused deposition modeling process is one such example, which involves controlled deposition of a melted/cast material through a computer-controlled nozzle in an automated layer-by-layer manner (Crump, 1992; Cao et al., 2003; Taboas et al., 2003).

In general, SFF techniques allow fabrication of precise complex shapes. In specific applications, some SFF techniques can also be used in combination with conventional scaffold fabrication techniques. For example, incorporation of porogens in the polymer powder for 3DP can be performed to introduce additional microfeatures in the scaffolds, which can improve the available surface area for cell attachment and mass transport, and enhance guided tissue regeneration (Kim et al., 1998b).

One limitation of the discussed techniques, with rare exceptions, is their inability to incorporate and pattern cells during the scaffold fabrication in a cytocompatible manner. Recently, development of new techniques that allow printing of cells during scaffold fabrication has been an area of great interest, the so-called organ printing or bioprinting technologies. In the automated process of bioprinting, controlled deposition of cell suspensions or cellular aggregates (“spheroids”) is applied to create three-dimensional cellular constructs of desired geometries (see review by Mironov et al., 2008). Direct inkjet printing of cells on hydrogels has been used to produce two-dimensional or multi-layered structures (Boland et al., 2003; Wilson and Boland, 2003; Xu et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2009). Using modified controlled dispensing methodologies, direct printing of cells loaded in cross-linkable viscous hydrogel precursors has been accomplished via extrusion, microstereolithography or inkjet printing (Smith et al., 2004; Cohen et al., 2006; Lu et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2007; Moon et al., 2010). In addition, self-assembly of multicellular structures has also been investigated, where controlled dispensing of cellular aggregates is performed directly into a hydrogel (Mironov et al., 2009). The bioprinting techniques show promise to alleviate some major challenges associated with the traditional approaches, including cell seeding at high densities, user-defined positioning of multiple cell types, and creation of vascular beds within large three-dimensional structures (Boland et al., 2006; Mironov et al., 2009).

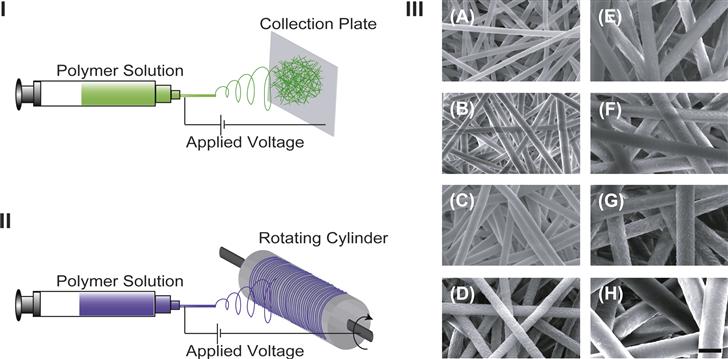

Electrospinning

Electrospinning is a versatile process with high production capability that has been used to form non-woven micro- and/or nanofibrous scaffolds using synthetic bioresorbable polymers (for reviews see Pham et al., 2006a; Murugan and Ramakrishna, 2007) (Figure II.6.3.3I). In a simple set-up, a dissolved solution of polymer is passed through a needle at a controlled rate. An electric field applied using a high voltage source across the needle and a grounded collector charges the surface of the polymer droplet held at the needle tip. When the forces of electrostatic repulsion within the solution overcome the surface tension, a thin polymer jet forms. Solvent evaporation occurs as the jet travels from the needle tip to the collector where polymer fibers are formed and deposited on the collector. Anisotropically distributed polymer fibers can be produced using a rotating mandrel or patterned electrodes, and these have been shown to influence the polarity of the cells (Figure II.6.3.3II) (Li et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2005). There are several variables (e.g., solution viscosity, polymer charge density, polymer molecular weight, surface tension, electric field strength, tip-to-collector distance, needle design, and the composition and design of the collector) that influence the process of electrospinning, and each can be varied selectively to obtain the desired fiber and scaffold morphology (Pham et al., 2006a). For example, by adjusting these variables, poly(ε-caprolactone) microfibers with a range of selected fiber diameters were produced (Figure II.6.3.3 III) (Pham et al., 2006b). In electrospun matrices, fiber size is the primary factor that defines the pore sizes and porosity of the scaffold. Recently, nanofibrous scaffolds have received special attention in tissue engineering, as the scaffolds are highly porous (>90% porosity) with a fiber architecture that resembles closely the nanofeatures of native ECM (Li et al., 2002). Due to the presence of nanofibers, a multi-layered PCL nanofiber/microfiber scaffold was shown to enhance cell attachment and spreading of rat marrow stromal cells, compared to scaffolds containing microfibers alone (Pham et al., 2006b). The electrospinning process also allows the possibility of controlled delivery of single or multiple bioactive factors. For example, using a coaxial needle design, core shell fibers with PEG as the core and PCL as the shell were produced that can be used for the controlled release of dual bioactive factors (Saraf et al., 2009, 2010). An issue that must often be addressed is that the nanodimensioned fibers have nanodimensioned interstices between them, hindering cell entry into the porous structure.

FIGURE II.6.3.3 Electrospinning process for the fabrication of fiber mesh scaffolds. (I, II) Schematic representations of electrospinning set-ups commonly used for the production of a non-woven fiber mesh (I), and an annulus of oriented fibers (II). (III) Scanning electron micrographs of electrospun non-woven poly(ε-caprolactone) microfibers of different fiber diameters: (A) 2 μm; (B) 3 μm; (C) 4 μm; (D) 5 μm; (E) 6 μm; (F) 7 μm; (G) 8 μm; and (H) 10 μm. (Scale bar: 10 μm) (Reproduced with permission from Pham et al., 2006a.)

In summary, manufacturing methodologies described herein have been widely applied to process bioresorbable synthetic materials into porous three-dimensional scaffolds. The selection of the technique depends both on the envisioned application, and on the material under consideration. Post-fabrication, the attributes of the processed scaffolds are usually determined by characterizing the scaffolds, as discussed in the following section.

Characterization of Processed Scaffolds

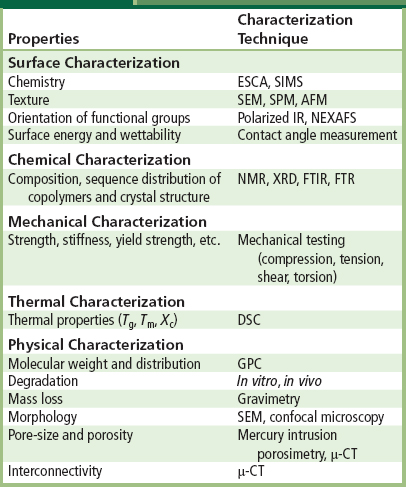

A number of techniques are available for the characterization of scaffolds (Table II.6.3.4). Surface chemistry of polymers (Chapter I.1.5) can be characterized by electron spectroscopy for chemical analysis (ESCA) and secondary ion mass spectroscopy (SIMS), among other techniques. Polarized infrared (IR) and near-edge X-ray absorption fine structure (NEXAFS) are employed to determine the orientation of the functional groups. Contact angle measurements provide information about the surface energy and wettability (hydrophilicity) of the polymer surface. Surface texture and roughness can be qualitatively or quantitatively assessed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), scanning probe microscopy (SPM) or atomic force microscopy (AFM). AFM may also be employed to determine the surface rigidity.

TABLE II.6.3.4 Bioresorbable Polymeric Scaffold Characterization Techniques

To determine the bulk properties (such as information regarding polymer composition, sequence distribution of co-polymers, and crystal structure), chemical characterization of the polymers can be performed using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, Fourier transform IR (FTIR) spectroscopy, FT-Raman (FTR) spectroscopy, and X-ray diffraction (XRD). Bulk mechanical properties are usually characterized by uniaxial mechanical testing under different modes of loading (e.g., compression, tension, shear, and torsion), and provide valuable data regarding mechanical characteristics (such as strength and modulus). Thermal properties (glass transition temperature (Tg), melting temperature (Tm) and degree of crystallinity (Xc)) are determined by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). Molecular weight and distribution are commonly determined by size exclusion chromatography methods, such as gel permeation chromatography (GPC). SEM and confocal microscopy can be employed to determine the microscopic structure and pore morphology qualitatively, while mercury intrusion porosimetry and μ-computed tomography (μ-CT) are useful techniques to determine the porosity and/or pore interconnectivity of the scaffolds quantitatively. Additionally, mass loss from the scaffold can be characterized by simple gravimetric evaluations. To characterize the in vitro degradation of the scaffolds, a combination of physical, chemical, and mechanical properties can be assessed as a function of time on scaffold samples placed under simulated physiological conditions. In vivo assessment is usually required, however, to assess “true” degradation rates, which are ideally coupled with the rate of tissue regeneration. Like in vitro degradation assessment, the in vitro release profile of any impregnated biomolecule from the scaffold can be quantitatively determined by using various techniques, such as radioactivity measurements of radiolabelled biomolecules.

Cell Seeding and Culture in Three-Dimensional Scaffolds

Engineering of large tissues and organs ex vivo generally requires culture of cells seeded at high densities in bioresorbable scaffolds in a controlled culture environment. However, there are many practical challenges that need to be overcome, such as uniform cell seeding, sufficient nutrient supply, and waste removal. In addition, control over the culture environment, including temperature, oxygen tension, pH, biochemical and mechanical stimulation (such as compression and shear stress), is desired (Vunjak-Novakovic, 2003 and Chapter II.6.6). To gain control over the physicochemical and hydrodynamic environment in culture conditions, various strategies have been developed that are used for cell seeding and culture of polymer constructs, some of which are described here.

Static Seeding and Culture

Static conditions represent the simplest form of cell seeding and culture. A cell suspension is allowed to adsorb onto a porous polymeric scaffold, cells are permitted to attach, and the constructs are then cultured in the presence of culture media (Figure II.6.3.4A). A major drawback of this method is that the penetration of a majority of cells in the scaffolds is generally limited to depths of approximately a few hundred microns (Ishaug et al., 1997), leading to undesired heterogeneous tissue growth. To improve cell penetration, several variations of seeding techniques exist, such as cell seeding by injection, centrifugation, and application of vacuum (van Wachem et al., 1990; Mikos et al., 1994a; Kim et al., 1998a; Godbey et al., 2004; Roh et al., 2007), which have all been shown to improve the cell distribution. To improve the cell seeding density in hydrophobic polymeric materials, various methods have been developed. Pre-wetting a hydrophobic polymeric scaffold with ethanol and water helps to increase the available volume for cell penetration by the displacement of air from the pores (Mikos et al., 1994a). Similarly, hydrolysis of the polymer surface or infiltration with hydrophilic polymers has been shown to increase the cellularity of the constructs (Mooney et al., 1995; Gao et al., 1998). As molecular diffusion is the primary driving force for nutrient supply and waste removal under static conditions, poor cell survival in the central parts of the scaffold is usually seen due to the gradients of nutrients and metabolites generated across the scaffold (Goldstein et al., 2001; Vunjak-Novakovic, 2003). To gain uniform cellularity and continuous convection-driven mass transport, various bioreactor devices have been built that are more suitable for the culture of large constructs and allow the possibility of multiple scaffold processing and scale-up, discussed next.

FIGURE II.6.3.4 Dynamic cell seeding and culture techniques used in vitro. (A) Static culture in a well plate. (B) Rotary vessel. (C) Spinner flask. (D) Flow perfusion system.

Spinner Flask Culture

In spinner flask culture, fluid flow driven by a magnetic stir bar creates a well-mixed cell suspension for dynamic seeding and culture of the scaffolds that are fixed inside the flask on needles or wires (Figure II.6.3.4B) (Sikavitsas et al., 2002). This technique has been applied to culture a variety of cells, including chondrocytes, hepatocytes, MSCs, and umbilical cord matrix stem cells (Yamada et al., 1998; Sikavitsas et al., 2002; Bailey et al., 2007). Optimization of stirring speed is usually desired, as turbulence and eddies generated at high speeds may improve cell penetration and mass transfer; however, these high speeds can also result in cell damage or ECM loss. Due to the velocity field created by the vortex of the stir bar and eddies generated on the rough surfaces of the scaffolds, convection is almost always higher at the exterior of the scaffold than in the interior (Goldstein et al., 2001; Vunjak-Novakovic, 2003). As a result, matrix formation in peripheral scaffold areas has been reported to be more prominent than in areas near the center (Vunjak-Novakovic et al., 2002; Meinel et al., 2004).

Rotary Vessel Culture

Rotary vessel culture usually involves the use of a rotating-wall cylindrical vessel (RWV) or two concentric vessels with the purpose of creating a microgravity environment for the constructs placed inside the vessel (Figure II.6.3.4C) (Freed and Vunjak-Novakovic, 1997). Centrifugal forces generated due to the rotation of the cylinder counterbalance the gravitational pull on the scaffolds, suspending the scaffolds in the culture medium in a low-shear laminar flow-dominated environment. By controlling the rotational speed, penetration of nutrients and oxygen into the scaffold can be adjusted. Rotary vessel culture is especially useful for applications where enhanced mass transport is needed in low shear environments. Rotary vessel culture has been applied for the engineering of musculoskeletal tissues (Freed et al., 1997; Goldstein et al., 2001; Sikavitsas et al., 2002; Detamore and Athanasiou, 2005), among other tissues.

Perfusion Culture

Direct flow perfusion culture systems have been developed for the in vitro reconstruction of large three-dimensional tissues and organs (Figure II.6.3.4D) (Griffith et al., 1997; Kim et al., 1998b; Bancroft et al., 2002; Grayson et al., 2008). In general, the culture medium continually circulates through the cell–polymer constructs. With a continuous flow of culture media through the porous structure of a scaffold, most mass transfer limitations are mitigated. In addition, flow-induced shear stresses can be modulated to upregulate desired cellular processes (such as cell differentiation or ECM production) in specific applications. For instance, increasing the shear stress resulted in an increased matrix deposition by MSCs cultured on three-dimensional scaffolds in a perfusion bioreactor (Sikavitsas et al., 2003). In another study, shear stress generated by direct perfusion was found to induce osteogenic differentiation of MSCs, even in the absence of other biochemical factors (Holtorf et al., 2005). Flow perfusion culture has also been shown to significantly outperform static culture, resulting in increased cellular proliferation, differentiation, and ECM deposition (van den Dolder et al., 2003; Datta et al., 2006). In addition to direct flow perfusion culture, other complex designs of perfusion bioreactors have also been developed, such as oscillatory flow perfusion bioreactors or pulsatile flow perfusion bioreactors (Brown et al., 2008b; Du et al., 2009).

Culture in Mechanically Stimulated Conditions

Mechanotransduction plays a key role in tissue development and maintenance (see reviews by Goodman and Aspenberg, 1993; Duncan and Turner, 1995; Sikavitsas et al., 2001; Ingber, 2006) (also see Chapter II.1.6). With the hypothesis that culture of cells in conditions that mimic the in vivo environment can optimize tissue regeneration in vitro, effects of biophysical forces on tissue growth in vitro have been widely studied, particularly for musculoskeletal and cardiovascular tissue engineering. The selection of mode of loading depends on the particular tissue engineering application, e.g., compression or shear for cartilage and bone tissue engineering, or tension for tendon tissue engineering. Level, loading profile (e.g., constant or cyclic), duration and frequency of mechanical stimulation are some of the variables that can influence cellular function.

Other Culture Conditions

As some cells respond to other particular biophysical cues, such as an electrical field (cardiac cells) or light intensity (retinal cells), inclusion of these as additional stimuli during the culture have also been studied (Hughes and Maffei, 1966; Radisic et al., 2004). Co-culture of different cell types is sometimes preferential to induce endogenous mutual signaling between the selected cell types, which has been used to facilitate in vitro organogenesis. Transwell culture systems have been used to selectively expose the apical and basal sides of the constructs to different media, desired in certain applications such as epithelial cell culture. Gradients of physical and chemical cues, which are known to influence cell motility, function, and survival, may also be introduced in the culture (Singh et al., 2008a). For instance, concentration gradients of growth factors have been widely applied for guided neurite growth in peripheral nerve regeneration. Moreover, the substrate on which cells are expanded in two dimensions is also important for specific applications. For example, engineering of continuous two-dimensional epithelial cell sheets is desired for corneal epithelial replacements (Hayashi et al., 2010). For this purpose, use of surfaces coated with temperature-responsive thermoreversible polymers (such as poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)) has been applied to engineer organized sheets of epithelial cells (Okano et al., 1995; Yamato et al., 2001) (Chapter I.2.11). The polymer is designed to support cell attachment at 37°C, whereas a reduction in temperature below its lower critical solution temperature swells the polymer, causing the cells to detach while remaining attached to their extracellular matrix and each other (Okano et al., 1995).

Conclusions

Continuous progress is being made towards the long-term goal of engineering human tissues and organs. As highlighted throughout the chapter, many challenges still remain that limit clinical success for several tissues. The integration of advances in biological sciences with modern material science will not only produce designed scaffolds, but will also generate new technologies for regenerative medicine applications.

Bibliography

1. Albrecht DR, Tsang VL, Sah RL, Bhatia SN. Photo- and electropatterning of hydrogel-encapsulated living cell arrays. Lab Chip. 2005;5:111–118.

2. Andriano KP, Tabata Y, Ikada Y, Heller J. In vitro and in vivo comparison of bulk and surface hydrolysis in absorbable polymer scaffolds for tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;48:602–612.

3. Arcaute K, Mann BK, Wicker RB. Stereolithography of three-dimensional bioactive poly(ethylene glycol) constructs with encapsulated cells. Ann Biomed Eng. 2006;34:1429–1441.

4. Babensee JE, Anderson JM, McIntire LV, Mikos AG. Host response to tissue engineered devices. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1998;33:111–139.

5. Babensee JE, McIntire LV, Mikos AG. Growth factor delivery for tissue engineering. Pharm Res. 2000;17:497–504.

6. Bailey MM, Wang L, Bode CJ, Mitchell KE, Detamore MS. A comparison of human umbilical cord matrix stem cells and temporomandibular joint condylar chondrocytes for tissue engineering temporomandibular joint condylar cartilage. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:2003–2010.

7. Bancroft GN, Mikos AG. Bone tissue engineering by cell transplantation. In: Reis RL, Cohn D, eds. Polymer Based Systems on Tissue Engineering, Replacement and Regeneration. Kluwer Academic Publishers 2002:251.

8. Bancroft GN, Sikavitsas VI, van den Dolder J, et al. Fluid flow increases mineralized matrix deposition in 3D perfusion culture of marrow stromal osteoblasts in a dose-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12600–12605.

9. Barby D, Haq Z. Low density porous cross-linked polymeric materials and their preparation. Eur Patent 0,060,138 1982.

10. Baroli B. Hydrogels for tissue engineering and delivery of tissue-inducing substances. J Pharm Sci. 2007;96:2197–2223.

11. Bartels KA, Bovik AC, Crawford RC, Diller KR, Aggarwal SJ. Selective laser sintering for the creation of solid models from 3D microscopic images. Biomed Sci Instrum. 1993;29:243–250.

12. Behravesh E, Mikos AG. Three-dimensional culture of differentiating marrow stromal osteoblasts in biomimetic poly(propylene fumarate-co-ethylene glycol)-based macroporous hydrogels. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;66:698–706.

13. Behravesh E, Jo S, Zygourakis K, Mikos AG. Synthesis of in situ cross-linkable macroporous biodegradable poly(propylene fumarate-co-ethylene glycol) hydrogels. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3:374–381.

14. Benoit DS, Schwartz MP, Durney AR, Anseth KS. Small functional groups for controlled differentiation of hydrogel-encapsulated human mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Mater. 2008;7:816–823.

15. Blum JS, Barry MA, Mikos AG. Bone regeneration through transplantation of genetically modified cells. Clin Plast Surg. 2003;30:611–620.

16. Boland T, Mironov V, Gutowska A, Roth EA, Markwald RR. Cell and organ printing 2: Fusion of cell aggregates in three-dimensional gels. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2003;272:497–502.

17. Boland ED, Coleman BD, Barnes CP, Simpson DG, Wnek GE, Bowlin GL. Electrospinning polydioxanone for biomedical applications. Acta Biomater. 2005;1:115–123.

18. Boland T, Xu T, Damon B, Cui X. Application of inkjet printing to tissue engineering. Biotechnol J. 2006;1:910–917.

19. Borden M, Attawia M, Khan Y, El-Amin SF, Laurencin CT. Tissue-engineered bone formation in vivo using a novel sintered polymeric microsphere matrix. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:1200–1208.

20. Brown JL, Nair LS, Laurencin CT. Solvent/non-solvent sintering: A novel route to create porous microsphere scaffolds for tissue regeneration. J Biomed Mater Res Part B Appl Biomater. 2008a;86B:396–406.

21. Brown MA, Iyer RK, Radisic M. Pulsatile perfusion bioreactor for cardiac tissue engineering. Biotechnol Prog. 2008b;24:907–920.

22. Bruin P, Smedinga J, Pennings A, Jonkman M. Biodegradable lysine diisocyanate-based poly (glycolide-co-epsilon-caprolactone)-urethane network in artificial skin. Biomaterials. 1990;11:291–295.

23. Bryant SJ, Cuy JL, Hauch KD, Ratner BD. Photo-patterning of porous hydrogels for tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2007;28:2978–2986.

24. Busby W, Cameron NR, Jahoda CA. Emulsion-derived foams (PolyHIPEs) containing poly(epsilon-caprolactone) as matrixes for tissue engineering. Biomacromolecules. 2001;2:154–164.

25. Busby W, Cameron NR, Jahoda CAB. Tissue engineering matrixes by emulsion templating. Polym Int. 2002;51:871–881.

26. Cameron NR. High internal phase emulsion templating as a route to well-defined porous structures. Polymer. 2005;46:1439–1449.

27. Cao T, Ho KH, Teoh SH. Scaffold design and in vitro study of osteochondral coculture in a three-dimensional porous polycaprolactone scaffold fabricated by fused deposition modeling. Tissue Eng. 2003;9(Suppl 1):S103–112.

28. Chen G, Tanaka J, Tateishi T. Osteochondral tissue engineering using a PLGA–collagen hybrid mesh. Mater Sci Eng C Biomim Mater Sens Syst. 2006;26:124–129.

29. Chen VJ, Ma PX. Nano-fibrous poly (L-lactic acid) scaffolds with interconnected spherical macropores. Biomaterials. 2004;25:2065–2073.

30. Cheng H, Jiang W, Phillips FM, et al. Osteogenic activity of the fourteen types of human bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:1544–1552.

31. Christenson EM, Soofi W, Holm JL, Cameron NR, Mikos AG. Biodegradable fumarate-based polyHIPEs as tissue engineering scaffolds. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8:3806–3814.

32. Cima LG, Vacanti JP, Vacanti C, Ingber D, Mooney D, Langer R. Tissue engineering by cell transplantation using degradable polymer substrates. J Biomech Eng. 1991;113:143–151.

33. Cohen DL, Malone E, Lipson H, Bonassar LJ. Direct freeform fabrication of seeded hydrogels in arbitrary geometries. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1325–1335.

34. Cook AD, Hrkach JS, Gao NN, et al. Characterization and development of RGD-peptide-modified poly(lactic acid-co-lysine) as an interactive, resorbable biomaterial. J Biomed Mater Res. 1997;35:513–523.