https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/19-Urological-infections_LR2.pdf.

https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/19-Urological-infections_LR2.pdf.Urinary tract infection: definitions and epidemiology

Urinary tract infection: microbiology

Lower urinary tract infection: cystitis and investigation of UTI

Urinary tract infection: general treatment guidelines

Recurrent urinary tract infection

Upper urinary tract infection: acute pyelonephritis

Pyonephrosis and perinephric abscess

Prostatitis: classification and pathophysiology

UTI is infection of the bladder (cystitis), kidneys (pyelonephritis), ureter (ureteritis), or urethra (urethritis). There is an associated inflammatory response of the urothelium to bacterial invasion, leading to a constellation of symptoms. Kass originally described significant bacteriuria as ≥105 colony-forming units per mL (CFU/mL) from an MSU specimen;1 however, it is now recognized that lower bacterial counts are still clinically relevant. Recommendations for diagnosing UTI from MSU culture are shown in Table 6.1. Any bacteria in a urine sample taken from a suprapubic bladder aspiration are clinically relevant.

•Bacteriuria: is the presence of bacteria in the urine and may be asymptomatic or symptomatic. Bacteriuria without pyuria may indicate the presence of bacterial colonization of the urine, rather than the presence of active infection.

•Pyuria: is the presence of WBCs in the urine, implying an inflammatory response of the urothelium to bacterial infection, or in the absence of bacteriuria (sterile pyuria), some other pathology such as carcinoma in situ, TB infection, bladder stones, or other inflammatory conditions.

•An uncomplicated UTI: is one occurring in a patient with a structurally and functionally normal urinary tract. The majority of such patients are women who respond quickly to a short course of antibiotics.

•A complicated UTI: is one occurring in the presence of an underlying anatomical or functional abnormality (e.g. incomplete bladder emptying secondary to BOO or DSD in SCI, renal or bladder stones, colovesical fistula, etc.). Other factors suggesting a potential complicated UTI are diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, hospital-acquired infection, indwelling catheter, recent urinary tract intervention, and a failure of response to appropriate treatment. Most UTIs in men are defined as complicated, as they tend to occur in association with a structural or functional abnormality. Complicated UTIs take longer to respond to antibiotic treatment than uncomplicated UTIs, and if there is an untreated underlying abnormality, they will usually recur.

UTIs may be isolated, recurrent, or unresolved.

•Isolated UTI: an interval of at least 6 months between infections.

•Recurrent UTI: >2 infections in 6 months or three within 12 months. Recurrent UTI may be due to re-infection (i.e. infection by different bacteria) or bacterial persistence (infection by the same organism originating from a focus within the urinary tract). Bacterial persistence may be caused by the presence of bacteria within calculi (e.g. struvite stone), within a chronically infected prostate (chronic bacterial prostatitis) or within an obstructed or atrophic infected kidney, or occurs as a result of a bladder fistula (with the bowel or vagina) or a urethral diverticulum.

•Unresolved infection: implies inadequate therapy and is caused by natural or acquired bacterial resistance to treatment, infection by (multiple) different organisms, or rapid re-infection.

Table 6.1 Recommended criteria for diagnosing UTI

| Type of UTI | Urine culture (CFU/mL) |

| Acute uncomplicated UTI/cystitis in women | ≥103 |

| Acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis | ≥104 |

| Complicated UTI | ≥105 in women; ≥104 in men |

| Asymptomatic bacteriuria | ≥105 in two consecutive MSU cultures >24h apart |

| Recurrent UTI | ≥103 |

CFU/mL, colony-forming units per mL; MSU, mid-stream urine.

Adapted from Grabe M, Bartoletti R, Bjerklund-Johansen TE, et al. EAU Guidelines on Urological Infections. European Association of Urology Guidelines 2015 with permission from the European Association of Urology.

The prevalence of UTI increases with age (Table 6.2). Around 50% of women experience one or more episodes in their lifetime. The incidence of UTI in women is around 3% per year, with 15% being recurrent UTI.

Table 6.2 Prevalence of UTI

| Age | Female | Male |

| Infants (<1y) | 1% | 3% |

| School (<15y) | 1–3% | <1% |

| Reproductive | 4% | <1% |

| Elderly | 20 –30% | 10% |

•Low oestrogen states (menopause).

•Institutionalized elderly patients.

•Stone disease (kidney, bladder).

•Genitourinary tract malformation.

•Voiding dysfunction (including obstruction).

•Indwelling catheters. The daily risk of UTI is around 5%. Catheter-associated UTIs (CAUTIs) account for up to 80% of hospital-acquired UTIs.

Reference

1Kass EH (1960). Bacteriuria and pyelonephritis of pregnancy. Arch Intern Med 105:194–8.

Further reading

Grabe M, Bartoletti R, Bjerklund-Johansen TE, et al. (2015). Guidelines on urological infections. European Association of Urology Guidelines 2015. Available from:  https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/19-Urological-infections_LR2.pdf.

https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/19-Urological-infections_LR2.pdf.

Most UTIs are caused by faecal-derived bacteria that are facultative anaerobes (i.e. they can grow under both anaerobic and non-anaerobic conditions) (Table 6.3).

Urinary infection in a subject with a normal functional and anatomical urinary tract. Most UTIs are bacterial in origin. The commonest cause is Escherichia coli, a Gram-negative bacillus, which accounts for 85% of community-acquired and 50% of hospital-acquired infections. Other common causative organisms include Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Proteus mirabilis, and Klebsiella.

Infection in a subject with a functional or anatomical abnormality of the urinary tract, underlying risk factors, or failure to respond to therapy. E. coli is responsible for up to 50% of cases. Other causes include enterococci, staphylococci, Pseudomonas, Proteus, Klebsiella, and other enterobacteria.

The vast majority of UTIs result from infection ascending retrogradely up the urethra. Bacteria, derived from the large bowel, colonize the perineum, vagina, and distal urethra. They ascend along the urethra to the bladder ( risk in ♀ as the urethra is shorter), causing cystitis. From the bladder, they may ascend via the ureters to involve the kidneys (pyelonephritis). Reflux is not necessary for infection to ascend to the kidneys, but it will encourage ascending infection, as will any process that impairs ureteric peristalsis (e.g. ureteric obstruction, Gram-negative organisms and endotoxins, pregnancy). Infection that ascends to involve the kidneys is also more likely where the infecting organism has P pili (filamentous protein appendages, also known as fimbriae, which allow binding of bacteria to the surface of epithelial cells).

risk in ♀ as the urethra is shorter), causing cystitis. From the bladder, they may ascend via the ureters to involve the kidneys (pyelonephritis). Reflux is not necessary for infection to ascend to the kidneys, but it will encourage ascending infection, as will any process that impairs ureteric peristalsis (e.g. ureteric obstruction, Gram-negative organisms and endotoxins, pregnancy). Infection that ascends to involve the kidneys is also more likely where the infecting organism has P pili (filamentous protein appendages, also known as fimbriae, which allow binding of bacteria to the surface of epithelial cells).

•Haematogenous: uncommon, but is seen with Staphylococcus aureus, Candida fungaemia, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (causing TB).

•Infection via lymphatics: seen rarely in inflammatory bowel disease and from retroperitoneal abscess.

Many Gram-negative bacteria have pili (also known as fimbriae) on their cell surface, which aid attachment to urothelial cells of the host. A typical piliated cell may contain 100–400 pili. Pili are 5–10nm in diameter and up to 2µm long. E. coli produces a number of antigenically and functionally different types of pili on the same cell; other strains may produce only a single type, and in some isolates, no pili are seen (such as Dr adhesin associated with UTI in pregnant women and children). Pili are defined functionally by their ability to mediate haemagglutination (clumping of RBCs) of specific types of erythrocytes. Mannose-sensitive (type 1) pili are produced by all strains of E. coli and are associated with cystitis. Certain pathogenic types of E. coli also produce mannose-resistant P pili and are associated with pyelonephritis. S pili are associated with infection of both the bladder and kidneys.

Table 6.3 Classification of bacteria and other organisms associated with the urinary tract and UTI

| Cocci | Gram +ve aerobes | Streptococcus | Non-haemolytic: Enterococcus (E. faecalis) α-haemolytic: S. viridans; β-haemolytic Streptococcus |

| Staphylococcus | S. saprophyticus (causes 10% of symptomatic lower UTIs in young, sexually active women)

S. aureus S. epidermidis |

||

| Gram –ve aerobes | Neisseria | N. gonorrhoeae | |

| Bacilli (rods) | Gram +ve aerobes | Corynebacteria | C. urealyticum |

| Acid-fast | Mycobacteria | M. tuberculosis | |

| Gram +ve anaerobes* | Lactobacillus | (i.e. L. crispatis and L. Jensenii are common vaginal commensal organisms)

Clostridium perfringens |

|

| Gram –ve aerobes | Enterobacteriaceae

Non-fermenters |

E. coli, P. mirabilis, Klebsiella spp. | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | |||

| Gram –ve anaerobes* | Bacteroides | Bacteroides fragilis | |

| Other organisms | Chlamydia | C. trachomatis | |

| Mycoplasma | M. hominus | ||

| Ureaplasma | U. urealyticum (causes UTI in patients with indwelling catheters | ||

| Candida | C. albicans | ||

* Anaerobic infections of the bladder and kidney are uncommon—anaerobes are normal commensals of the perineum, vagina, and distal urethra. However, infections of the urinary system that produce pus (e.g. scrotal, prostatic, or perinephric abscesses) can be caused by anaerobic organisms (e.g. Bacteroides spp. such as B. fragilis, Fusobacterium spp., anaerobic cocci, and C. perfringens).

•General: an extracellular capsule reduces immunogenicity and resists phagocytosis (E. coli). M. tuberculosis resists phagocytosis by preventing phagolysosome fusion.

•Toxins: E. coli species have haemolysin activity which has a direct pathogenic effect on host erythrocytes.

•Enzyme production: Proteus species produce ureases which cause the breakdown of urea in urine to ammonia, which then contributes to disease processes (struvite stone formation).

•Enzyme inactivation: S. aureus, N. gonorrhoeae, and enterobacteria can produce β-lactamase which hydrolyses the β-lactam bond within the structure of some antibiotics, so inactivating them. The β-lactam antibiotics are penicillins, cephalosporins, and carbapenems.

•Altered permeability: access of the antibiotic to the bacteria is prevented by alterations in receptor activity or transport mechanisms.

•Alteration of binding site: genetic variations may alter the antibiotic target, leading to drug resistance.

Factors that protect against UTI include the following.

•Commensal flora: protect by competing for nutrients, bacteriocin production, stimulation of the immune system, and altering pH.

•Mechanical integrity of mucous membranes.

•Mucosal secretions: lysozymes split muramic acid links in cell walls of Gram-positive organisms; lactoferrin disrupts the normal metabolism of bacteria.

•Urinary IgA inhibits bacterial adherence.

•Mechanical flushing effect of urine through the urinary tract (i.e. antegrade flow of urine).

•A mucopolysaccharide coating of the bladder (Tamm–Horsfall protein) helps prevent bacterial attachment.

•Bladder surface mucin: glycosaminoglycan (GAG) layer is an anti-adherent factor, preventing bacterial attachment to the mucosa.

•Low urine pH and high osmolarity reduce bacterial growth.

•♀ commensal flora: Lactobacillus acidophilus metabolizes glycogen into lactic acid, causing a drop in pH.

• rates of bladder mucosal cell exfoliation are seen during infection, which accelerates cell removal with adherent bacteria.

rates of bladder mucosal cell exfoliation are seen during infection, which accelerates cell removal with adherent bacteria.

Cystitis is infection and/or inflammation of the bladder.

•Presentation: frequent voiding of small volumes, dysuria, urgency, offensive urine, suprapubic pain, haematuria, fever ± incontinence. Enquire about frequency of infections and triggers, and assess risk factors. It is helpful to obtain a full microbiology history where results are available.

•Examination: check for a palpable bladder and post-void urine residuals. Include a pelvic examination in women to assess for atrophic vaginitis, prolapse, and the presence of a urethral diverticulum.

Leucocyte esterase activity detects the presence of WBCs in the urine. Leucocyte esterase is produced by neutrophils and causes a colour change in a chromogen salt on the dipstick. Not all patients with bacteriuria have significant pyuria (sensitivity of 75–95% for detection of infection, i.e. 5–25% of patients with infection will have a negative leucocyte esterase test, erroneously suggesting that they have no infection).

•False positives (pyuria present, negative dipstick test)—concentrated urine, glycosuria, presence of urobilinogen, consumption of large amounts of ascorbic acid.

•False negatives (pyuria absent, positive dipstick test)—contamination.

Remember, there are many causes for pyuria (and therefore a positive leucocyte esterase test occurring in the absence of bacteria on urine microscopy). This is so-called sterile pyuria, and it occurs with TB infection, renal calculi, bladder calculi, glomerulonephritis, interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome, and carcinoma in situ. Thus, the leucocyte esterase dipstick test may be truly positive in the absence of infection.

Nitrites are not normally found in urine, and their presence suggests the possibility of bacteriuria. Many species of Gram-negative bacteria can convert nitrates to nitrites. These are detected in the urine by a reaction with the reagents on the dipstick which form a red azo dye. The specificity of the nitrite dipstick for detecting bacteriuria is >90% (false-positive nitrite testing can occur with contamination). The sensitivity is 35–85% (i.e. false negatives are common—a negative dipstick in the presence of active infection) and is less accurate in urine containing <105 organisms/mL. Hence, if the nitrite dipstick test is positive, the patient probably has a UTI, but a negative test often occurs in the presence of infection.

Cloudy urine, which is positive for WBCs on dipstick and is nitrite-positive, is very likely to be infected.

Hb has a peroxidase-like activity, causing oxidation of a chromogen indicator on the dipstick, which changes colour when oxidized. False positives are seen with menstrual blood and dehydration.

Urinary pH usually lies between 5.5 and 6.5 (range 4.5–8). A persistent alkaline pH associated with UTI indicates a risk of stones. Urease-producing bacteria (such as p. mirabilis) hydrolyse urea to ammonia and carbon dioxide, leading to the formation of magnesium, calcium, and ammonium phosphate stones (triple phosphate or struvite calculi).

•False negative: low bacterial counts may make it very difficult to identify bacteria, and the specimen of urine may therefore be deemed to be negative for bacteriuria when, in fact, there is active infection.

•False positive: bacteria may be seen in the MSU in the absence of infection. This is most often due to contamination with commensals from the distal urethra and perineum (urine from a woman may contain thousands of lactobacilli and corynebacteria derived from the vagina). These bacteria are readily seen under the microscope, and although they are Gram-positive, they often appear Gram-negative (Gram-variable) if stained.

If the urine specimen contains large numbers of squamous epithelial cells (cells which are derived from the foreskin, vaginal, or distal urethral epithelium), this suggests contamination of the specimen, and the presence of bacteria in this situation may indicate a false-positive result. The finding of pyuria and RBCs suggests the presence of active infection.

If this is a one-off infection in an otherwise healthy individual, no further investigations are required. Investigation for uncomplication recurrent UTI also has a low diagnostic yield in women. However, investigation is required if:

•The patient develops symptoms and signs of upper tract infection (loin pain, malaise, fever)—if clinical suspicion of acute pyelonephritis, pyonephrosis, or perinephric abscess.

•Recurrent UTIs develop (see  pp. 204–207).

pp. 204–207).

•Unusual infecting organism (e.g. Proteus), suggesting the possibility of an infection stone.

•Red flag symptoms—such as bladder pain, storage symptoms, or haematuria persisting after UTI is treated.

These further investigations will include imaging with USS (or CT if suspecting stones) and cystoscopy.

Symptoms of cystitis can also be caused by:

•Pelvic radiotherapy (radiation cystitis—bladder capacity is reduced and multiple areas of mucosal telangiectasia are seen cystoscopically).

•Drug-induced cystitis, e.g. cyclophosphamide, ketamine, intravesical bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) therapy.

•Bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis.

The aim is to eliminate bacterial growth from the urine. Empirical treatment involves the administration of antibiotics according to the clinical presentation and the most likely causative organism before culture sensitivities are available. Microbiology departments produce their own local hospital recommendations, which will be based on local and regional bacterial sensitivities and resistance, and should be followed. Men are often affected by complicated UTI and may require longer treatments, as will patients with uncorrectable structural or functional abnormalities (e.g. indwelling catheters, neuropathic bladders). Once culture results are available, the antibiotic should be changed according to sensitivities. Mild–moderate severity infections can be treated with oral antibiotics, whereas patients who have severe infection and are systemically unwell require hospital admission for IV drugs until improvement is seen (i.e. in temperature and other parameters), after which the patient can be stepped down to oral antibiotics to complete a full course of treatment (1–2 weeks).

If the local resistance pattern is <20%, options for UTI include: fluoroquinolone, aminopenicillin + β-lactamase inhibitor (i.e. co-amoxiclav), cephalosporin (group 3b), and aminoglycoside (i.e. gentamicin).1

See Table 6.4.

Organisms susceptible to concentrations of an antibiotic in the urine (or serum) after the recommended clinical dosing are termed ‘sensitive’, and those that do not respond are ‘resistant’. Bacterial resistance may be intrinsic via selection of a resistant mutant during initial treatment (e.g. Proteus is intrinsically resistant to nitrofurantoin) or genetically transferred between bacteria by R plasmids. Antibiotic-resistant organisms that cause complicated UTI include Gram-negative bacteria that produce AmpC enzymes or extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) which are often multidrug-resistant, and Gram-positive cocci such as meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), meticillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci (MRCoNS), and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE). To avoid increasing resistance, the emphasis is on antibiotic stewardship—it is not advisable to commence antibiotics without clinical evidence of a UTI (exceptions include asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy), and local microbiology guidelines should be followed.

Table 6.4 General guide to antibiotic treatment of UTI

| Infection | Antibiotic | Duration |

| Acute, uncomplicated cystitis | Nitrofurantoin PO | 5 days |

| Alternatives: | ||

| Trimethoprim* PO | 5 days | |

| Ciprofloxacin PO | 3 days | |

| Cephalosporin PO | 3 days | |

| Acute, mild–moderate uncomplicated pyelonephritis | Fluoroquinolone PO | 7–10 days |

| Alternatives: | ||

| Cephalosporin PO | 10 days | |

| Co-amoxiclav** PO | 14 days | |

| Acute, severe complicated pyelonephritis | Fluoroquinolone | Initial IV antibiotics; after clinical improvement change to PO and complete a 1–2wk course |

| Alternatives: | ||

| Cephalosporin | ||

| Co-amoxiclav | ||

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | ||

| Gentamicin | ||

| Meropenem | ||

PO, oral; IV, intravenous administration.

* If local resistance pattern is known (i.e. E. coli resistance <20%).

** If the uropathogen is known to be susceptible.

These are general recommendations adapted from EAU guidelines to fit with UK antibiotic use. You should be guided by your local microbiology department recommendations. Refer also to the BNF, and check contraindications to antibiotics during pregnancy (see  p. 661). Also note that antibiotics can affect the efficacy of the oral contraceptive pill, so alternative forms of contraception may be required during treatment.

p. 661). Also note that antibiotics can affect the efficacy of the oral contraceptive pill, so alternative forms of contraception may be required during treatment.

Once urine or blood culture results are available, antimicrobial therapy should be adjusted according to bacterial sensitivities. Any reversible or underlying abnormality should be corrected if feasible (i.e. extraction of an infected calculus, removal of catheter, nephrostomy drainage of an infected and obstructed kidney).

Encourage a good fluid intake; ensure adequate bladder emptying; avoid constipation. In women—voiding before and after intercourse; avoid using bubble bath or washing hair in the bath (as this affects the protective commensal organisms—the lactobacilli). Post-menopausal women may benefit from topical oestrogen treatment.

Reference

1Grabe M, Bartoletti R, Bjerklund-Johansen TE, et al. (2015). Guidelines on urological infections. European Association of Urology Guidelines 2015. Available from:  https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/19-Urological-infections_LR2.pdf.

https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/19-Urological-infections_LR2.pdf.

Recurrent UTI (rUTI) is defined as >2 infections in 6 months or three infections within 12 months. It may be due to re-infection (i.e. infection by different bacteria) or bacterial persistence (infection by the same organism originating from a focus within the urinary tract).

This usually occurs after a prolonged interval (months) from the previous infection and is often caused by a different organism than the previous infecting bacterium.

•Women: with re-infection do not usually have an underlying functional or anatomical abnormality. Re-infections are associated with  vaginal mucosal receptivity for uropathogens and ascending colonization from faecal flora. These women cannot be cured of their predisposition to rUTIs, but they can be managed by a variety of techniques (see below). Women who have suffered one UTI have a 20% risk of experiencing another UTI in the next 6 months.

vaginal mucosal receptivity for uropathogens and ascending colonization from faecal flora. These women cannot be cured of their predisposition to rUTIs, but they can be managed by a variety of techniques (see below). Women who have suffered one UTI have a 20% risk of experiencing another UTI in the next 6 months.

•Men: with re-infection may have underlying BOO (i.e. due to BPE or a urethral stricture), which makes them more likely to develop a repeat infection, but between infections, their urine is sterile (i.e. they do not have bacterial persistence between symptomatic UTIs). A flexible cystoscopy, PVR urine volume measurement, USS and, in some cases, urodynamics or urethrography may be helpful in establishing the potential causes.

Both men and women with bacterial persistence usually have an underlying functional or anatomical abnormality, and they can potentially be cured of their rUTIs if this abnormality can be identified and corrected.

Imaging tests, including renal USS, and flexible cystoscopy can be performed to check for potential sources of suspected bacterial persistence (i.e. to confirm this is a ‘simple’ case of re-infection, rather than one of bacterial persistence), but often they are normal.

•Most encourage a good fluid intake, although evidence for this is limited.

•Avoidance of spermicides used with the diaphragm or on condoms. Spermicides containing nonoxynol-9 reduce vaginal colonization with lactobacilli and may enhance E. coli adherence to urothelial cells. Recommend an alternative form of contraception.

•Avoid bubble baths and perfumed soaps on the perineum which can strip away the commensal ‘protective’ organisms (lactobacilli).

•Cranberry tablets or juice: contains proanthocyanidins which inhibit bacterial adherence. Results have been conflicting as to the clinical benefit.

•Oestrogen replacement: a lack of oestrogen in post-menopausal women causes loss of vaginal lactobacilli and  colonization by E. coli. Topical oestrogen replacement can result in recolonization of the vagina with lactobacilli and help eliminate colonization with bacterial uropathogens.

colonization by E. coli. Topical oestrogen replacement can result in recolonization of the vagina with lactobacilli and help eliminate colonization with bacterial uropathogens.

•Alkalinization of the urine: with potassium citrate or sodium bicarbonate can help alleviate the ‘burning’ symptoms of active cystitis.

•Intravaginal lactobacilli: some limited evidence of benefit.

•Vitamin C (ascorbic acid): causes acidification of the urine and a bacteriostatic effect—some limited evidence of benefit.

•D-mannose: in studies, it blocks E. coli adhesion and invasion of urothelial cells; however, clinical evidence is limited as a prophylactic.

•Vaccines (Uro-Vaxom®): daily oral capsule containing 18 strains of E. coli. Not widely available.

•Methenamine hippurate (Hiprex®): a prophylactic with wide-spectrum antimicrobial effects (not used to treat active infections). It is hydrolysed in urine to form formaldehyde, which is bacteriostatic, and so it avoids bacterial resistance. Acidic urine is needed for it to have an antibacterial effect. It creates an acidic environment itself (via hippuric acid), but additional high-dose vitamin C can be given. Not helpful in patients with a neuropathic bladder or urinary tract abnormalities. The ALTAR study (ALternative To prophylactic Antibiotics for the treatment of Recurrent urinary tract infections in women) is an NIHR-HTA study randomizing patients to methenamine vs low-dose antibiotics, to assess the effects on rUTI prevention (results pending). Side effects: rash, pruritus, stomach and bladder irritation. Contraindications: severe renal impairment, liver impairment, gout, severe dehydration, pregnancy. Avoid concomitant use with sulfonamides, alkalizing agents, and acetazolamide.

•Intravesical GAG analogues (sodium hyaluronate, chondroitin sulfate): given as separate treatments or in combination (IAluRil®). Placed in the bladder via an in-and-out catheter for an induction course (once per week for 4–6wk) and then maintenance if beneficial (once per month for 4–6 months). We would tend to use this after other medical and antibiotic prophylaxis has shown only partial benefit or failed.

Oral antimicrobial therapy with full-dose oral tetracyclines, ampicillin, sulfonamides, amoxicillin, and cefalexin causes resistant strains in the faecal flora and subsequent resistant UTIs. However, trimethoprim, nitrofurantoin, and low-dose cefalexin have minimal adverse effects on the faecal and vaginal flora.

•Efficacy of prophylaxis: A Cochrane review reports significant reduction of microbiology rUTI by around 4-fold, and clinical recurrence by 13-fold, with the number needed to treat to prevent one symptomatic rUTI being 1.85.1 Only small doses of antimicrobial agent are required, generally given at bedtime for 6–12 months. Symptomatic re-infection during prophylactic therapy is managed with a full therapeutic dose with the same prophylactic antibiotic or another antibiotic. Prophylaxis can then be restarted. Symptomatic re-infection immediately after cessation of prophylactic therapy is managed by restarting nightly prophylaxis.

•Trimethoprim (100mg daily): the gut is a reservoir for organisms that colonize the peri-urethral area which may cause episodes of acute cystitis in young women. Trimethoprim eradicates Gram-negative aerobic flora from the gut and vaginal fluid (i.e. it eliminates the pathogens from the infective source). Trimethoprim is also concentrated in bactericidal concentrations in the urine following an oral dose. Side effects: GI disturbance, rash, pruritus, depression of haematopoiesis, allergic reactions. Use with caution in renal impairment, as it can increase creatinine by competitively inhibiting tubular secretion.

•Nitrofurantoin (50–100mg daily): completely absorbed and/or inactivated in the upper intestinal tract and therefore has no effect on gut flora. It is present for brief periods at high concentrations in the urine and leads to repeated elimination of bacteria from the urine. Nitrofurantoin prophylaxis therefore does not lead to a change in vaginal or introital colonization with enterobacteria. Bacteria colonizing the vagina remain susceptible to nitrofurantoin because of the lack of bacterial resistance in the faecal flora. Side effects: GI upset, chronic pulmonary reactions (pulmonary fibrosis), peripheral neuropathy, allergic reactions, liver impairment. This drug should be used for limited periods only.

•Cefalexin: at 125–250mg nightly is an excellent prophylactic agent because faecal resistance does not develop at this low dosage. Side effects: GI upset, allergic reactions.

•Ciprofloxacin (125mg daily): short courses eradicate enterobacteria from faecal and vaginal flora. The (longer term) use of ciprofloxacin is increasingly discouraged, with some hospitals not allowing its routine use in an attempt to reduce the incidence of symptomatic C. difficile. Side effects: tendon damage (including rupture) which may occur within 48h of starting treatment (rare). The risk of tendon rupture is  by the concomitant use of corticosteroids. Avoid in patients with known tendon disorders.

by the concomitant use of corticosteroids. Avoid in patients with known tendon disorders.

•Fosfomycin: while EAU guidelines recommend this as antibiotic for empirical use, in the UK, it tends to be only available for prescription after microbiology advice and generally reserved for multidrug-resistant UTIs. Treatment dose is a 1g sachet as single dose; prophylaxis is 1g every 10 days PO.

Sexual intercourse has been established as an important risk factor for acute cystitis in women. In addition, women using the diaphragm have a significantly greater risk of UTI than those using other contraceptive methods. Post-coital therapy with antimicrobials, such as nitrofurantoin, cefalexin, or trimethoprim, taken as a single dose (once daily), effectively reduces the incidence of re-infection.

Women keep a home supply of an antibiotic (e.g. trimethoprim, nitrofurantoin, or a fluoroquinolone) and start treatment when they develop symptoms suggestive of a UTI (preferably having first delivered a urine specimen to their GP for culture). They can also be provided with instructions on the use of urine dipsticks to help confirm the diagnosis.

Bacterial persistence usually leads to frequent recurrence of infection (within days or weeks), and the infecting organism is usually the same organism as that causing the previous infection(s). Uropathogenic E. coli have been found to penetrate urothelial cells and form quiescent intracellular bacterial reservoirs, which can act as a nidus for bacterial persistence and UTI recurrence. Often, there is also an underlying functional or anatomical problem, and infection will usually not resolve until this has been corrected. Causes include kidney stones, a chronically infected prostate (chronic bacterial prostatitis), bacteria within an obstructed or atrophic infected kidney, vesicovaginal or colovesical fistula, and bacteria within a urethral diverticulum.

These are directed at identifying the potential causes of bacterial persistence.

•KUB X-ray to detect radio-opaque renal calculi.

•Renal USS to detect hydronephrosis and renal calculi. If hydronephrosis is present, but the ureter is not dilated, consider the possibility of a radio-opaque stone obstructing the PUJ or a PUJO.

•Determination of PVR volume by bladder USS.

•CT where a stone is suspected, but not identified on plain X-ray or USS; CTU to assess for abnormal urinary tract anatomy.

•Flexible cystoscopy to identify possible causes of rUTIs such as bladder stones, an underlying bladder cancer (rare), a urethral or bladder neck stricture, or a fistula.

•Urodynamics—for associated voiding dysfunction.

This depends on the functional or anatomical abnormality that is identified as the cause of the bacterial persistence. If a stone is identified, this should be removed. If there is obstruction (e.g. BOO, PUJO, DSD), this should be corrected.

Reference

1Albert X, Huertas I, Pereiro II, et al. (2004). Antibiotics for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in non-pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD001209.

Definition: pyelonephritis is an inflammation of the kidney and renal pelvis.

Clinical diagnosis is based on the presence of fever, flank pain, bacteriuria, pyuria, usually with an elevated white cell count (WCC). Nausea and vomiting are common. It may affect one or both kidneys. There are usually accompanying symptoms suggestive of a lower UTI (frequency, urgency, suprapubic pain, urethral burning or pain on voiding) responsible for the subsequent ascending infection to the kidney.

•Differential diagnosis: cholecystitis, pancreatitis, diverticulitis, and appendicitis.

•Risk factors: ♀ > ♂, VUR, urinary tract obstruction, calculi, SCI (neuropathic bladder), diabetes mellitus, congenital malformation, pregnancy, indwelling catheters, urinary tract instrumentation.

•Pathogenesis and microbiology: initially, there is patchy infiltration of neutrophils and bacteria in the parenchyma. Later changes include the formation of inflammatory bands, extending from the renal papilla to the cortex, and small cortical abscesses. Eighty per cent of infections are secondary to E. coli (possessing P pili virulence factors). Other infecting organisms: enterococci (E. faecalis), Klebsiella, Proteus, staphylococci, and Pseudomonas. Any process interfering with ureteric peristalsis (i.e. obstruction) may assist in retrograde bacterial ascent from bladder to kidney.

•For those patients who have a fever but are not systemically unwell, outpatient management is reasonable. Culture the urine, and start oral antibiotics according to your local antibiotic policy (which will be based on the likely infecting organisms and their likely antibiotic sensitivity). EAU guidelines1 give several suggestions, with first-line drugs being fluoroquinolones (oral ciprofloxacin 500mg bd for 7–10 days) if E. coli resistance is <10%.

•If the patient is systemically unwell, resuscitate, culture urine and blood, and start IV fluids and IV antibiotics, again selecting the antibiotic according to your local antibiotic policy. The EAU guideline1 first-line option is fluoroquinolones (i.e. IV ciprofloxacin 400mg bd), with alternatives being cephalosporins, co-amoxiclav, gentamicin, piperacillin with tazobactam (Tazocin®), or meropenem.

•Arrange a renal USS to look for obstruction or stones, and CT if required (i.e. if hydronephrosis is identified, CT can be used to look for a ureteric stone, tumour, or clot).

•If the patient does not respond within 3 days to a regimen of appropriate IV antibiotics (confirmed on sensitivities), arrange a contrast CT (± delayed-phase urogram). Failure to respond to treatment suggests possible pyonephrosis (i.e. pus in the kidney), a perinephric abscess, or complicated pyelonephritis. Pyonephrosis should be drained by insertion of a percutaneous nephrostomy tube. A perinephric abscess should have an image-controlled percutaneous drain insertion.

•If the patient responds to IV antibiotics, change to an oral antibiotic of appropriate sensitivity when they become apyrexial (i.e. after control of infection or after elimination of the underlying problem), and continue this for a 1- to 2-wk course in total.

Reference

1Grabe M, Bartoletti R, Bjerklund-Johansen TE, et al. (2015). Guidelines on urological infections. European Association of Urology Guidelines 2015. Available from:  https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/19-Urological-infections_LR2.pdf.

https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/19-Urological-infections_LR2.pdf.

An infected hydronephrosis where pus accumulates within the renal pelvis and calyces. It is associated with damage to the parenchyma, resulting in loss of renal function. The causes are essentially those of hydronephrosis where infection has supervened (e.g. ureteric obstruction by stone, PUJO).

Patients with pyonephrosis are usually very unwell, with a high fever, flank pain, and tenderness.

Stone disease, previous UTI, or surgery.

•USS: shows evidence of obstruction (hydronephrosis) with a dilated collecting system, fluid–debris levels, or air in the collecting system.

•CT: shows hydronephrosis, stranding of perinephric fat, and thickening of the renal pelvis.

IV fluids and IV antibiotics (as for severe pyelonephritis), with urgent percutaneous drainage (nephrostomy) and/or ureteric stent.

Perinephric abscess develops as a consequence of extension of infection outside the parenchyma of the kidney in acute pyelonephritis, from rupture of a cortical abscess, or if obstruction in an infected kidney (i.e. pyonephrosis) is not drained quickly enough. More rarely, it is due to haematogenous spread of infection from a distant site or infection from adjacent organs (i.e. bowel). The abscess develops within Gerota’s fascia.

Diabetes mellitus; immunocompromise; an obstructing ureteric calculus may precipitate the development of a perinephric abscess.

Perinephric abscesses are caused by S. aureus (Gram-positive), E. coli, and Proteus (Gram-negative organisms).

Patients present with fever, unilateral flank tenderness, and ≥5-day history of milder symptoms. Failure of a seemingly straightforward case of acute pyelonephritis to respond to IV antibiotics within a few days also arouses suspicion that there is an accumulation of pus in or around the kidney or an obstruction with infection.

A flank mass with overlying skin erythema and oedema may be observed. Extension of the thigh (stretching the psoas) may trigger pain, and psoas spasm may cause reactive scoliosis.

•FBC: shows raised WCC and C-reactive protein (CRP).

•Blood cultures: are required to identify organisms responsible for the haematogenous spread of infection (i.e. S. aureus).

•USS or CTU: can identify the size, site, and extension of retroperitoneal abscesses and allow radiographically controlled percutaneous drainage.

Commence broad-spectrum IV antibiotics according to local microbiology guidelines (i.e. aminoglycoside and co-amoxiclav) until culture sensitivities are available. Drainage of the collection should be performed, either radiographically or by formal open incision and drainage if the pus collection is large. IV antibiotics should be used initially and followed by oral antimicrobials until clinical review and re-imaging confirm resolution of infection. Nephrectomy may be required for extensive renal involvement or a non-functioning infected kidney.

Maintaining a degree of suspicion in all cases of presumed acute pyelonephritis is the single most important thing in allowing an early diagnosis of complicated renal infection such as a pyonephrosis, perinephric abscess, or emphysematous pyelonephritis (EPN) to be made. If the patient is very unwell, is diabetic, or has a history suggestive of stones, they may have something more than just a simple acute pyelonephritis. Specifically ask about a history of sudden onset of severe flank pain a few days earlier, suggesting the possibility that a stone passed into the ureter, with later infection supervening. Arranging a renal USS in all patients with suspected renal infection will demonstrate the presence of hydronephrosis, pus, or stones, and follow up with CT if concerns (i.e. hydronephrosis).

Clinical indicators suggesting a more complex form of renal infection are length of symptoms prior to treatment and time taken to respond to treatment. Most patients with uncomplicated acute pyelonephritis have been symptomatic for <5 days. Most with, for example, a perinephric abscess have been symptomatic for >5 days prior to hospitalization. Patients with acute pyelonephritis became afebrile within 4–5 days of treatment with an appropriate antibiotic, whereas those with perinephric abscesses remained pyrexial.

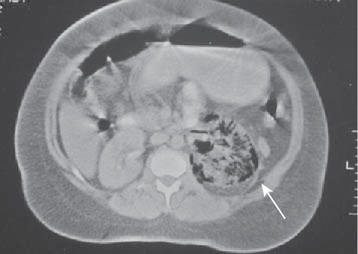

A rare severe form of acute necrotizing pyelonephritis caused by gas-forming organisms. It is characterized by fever and abdominal pain, with radiographic evidence of gas within and around the kidney (on plain radiography or CT) (Fig. 6.1). It usually occurs in diabetics and, in many cases, is precipitated by urinary obstruction by, for example, ureteric stones. High glucose levels associated with poorly controlled diabetes provide an ideal environment for fermentation by enterobacteria, with carbon dioxide being produced during this process. EPN is commonly caused by E. coli, and less frequently by Klebsiella and Proteus.

Severe acute pyelonephritis (high fever and systemic upset) that fails to respond to IV antibiotics within 2–3 days.

KUB X-ray may show a crescent- or kidney-shaped distribution of gas around the kidney. Renal USS often demonstrates strong focal echoes, indicating gas within the kidney. CT can help classify the disease. Type I shows parenchymal destruction, an absence of fluid collection, or streaky gas from the medulla to cortex—this has a poorer prognosis. Type II shows intrarenal gas and renal or perirenal fluid, or collecting system gas—this has a better prognosis.

Patients with EPN are usually very unwell (to the extent that many are not fit enough for emergency nephrectomy), and mortality is high. Resuscitate and transfer to the intensive treatment unit (ITU)/high-dependency unit (HDU). Management is with IV antibiotics, IV fluids, percutaneous drainage, and careful control of diabetes. Where there is no symptomatic improvement, have a low threshold for rescanning (CT) and consider additional percutaneous drainage for ‘pockets’ of infection that have not been adequately drained. In those where sepsis is poorly controlled, emergency nephrectomy may be required.

An uncommon, severe form of chronic renal infection. It usually (although not always) occurs in association with underlying renal (staghorn) calculi and renal obstruction. Three forms exist: focal (XGP in the renal cortex with no pelvic communication), segmental, and diffuse. The chronic granulomatous process results in the destruction of renal tissue, leading to a non-functioning kidney. E. coli and Proteus are common causative organisms. Lipid-laden, ‘foamy’ macrophages become deposited around abscesses within the parenchyma of the kidney. The infection may be confined to the kidney or extend to the perinephric fat. The kidney becomes grossly enlarged and macroscopically contains yellowish nodules (pus) and areas of haemorrhagic necrosis. It can be very difficult to distinguish the radiological findings from a renal cancer on imaging studies such as CT. Indeed, in many cases, the diagnosis is made after nephrectomy for what was presumed to be an RCC.

Flank pain, fever, malaise, haematuria, LUTS, and a tender flank mass. It affects all age groups, ♀ more often than ♂. Associated with diabetes.

Fistula (nephrocutaneous, nephrocolonic), paranephric abscess, psoas abscess.

Blood tests show anaemia and leucocytosis. Bacteria (E. coli, Proteus) may be found on culture of urine. Renal USS shows an enlarged kidney containing echogenic material. CT may identify (obstructing) renal or urinary tract calculi, hydronephrosis, renal cortical thinning, and perinephric fat inflammation. Non-enhancing cavities are seen, containing pus and debris. On radioisotope scanning (DMSA, MAG3 renogram), there may be reduced or no function in the affected kidney.

On presentation, these patients are usually commenced on antibiotics, as the constellation of symptoms and signs suggest infection. If systemically unwell, transfer to ITU/HDU for treatment. When imaging studies are done, such as CT, the appearances usually suggest the possibility of an RCC, and therefore, when signs of infection have resolved, patients commonly have proceeded to nephrectomy. Often, only following pathological examination of the removed kidney will it become apparent that the diagnosis was one of infection (XGP), rather than a tumour.

Fig. 6.1 Enhanced axial CT scan demonstrating emphysematous pyelonephritis affecting the left kidney.

Image kindly provided with permission from Professor S. Reif.

In essence, this describes renal scarring which may or may not be related to previous UTI. It is a radiological, functional, or pathological diagnosis or description.

•Renal scarring due to previous infection.

•Long-term effects of VUR, with or without superimposed infection.

A child with VUR, particularly where there is reflux of infected urine, will develop reflux nephropathy (which, if bilateral, may cause renal impairment or renal failure). If the child’s kidneys are examined radiologically (or pathologically if they are removed by nephrectomy), the radiologist or pathologist will describe the appearances as those of ‘chronic pyelonephritis’.

An adult may also develop radiological and pathological features of chronic pyelonephritis due to the presence of reflux or BOO combined with high bladder pressures, again particularly where the urine is infected. This was a common occurrence in ♂ patients with SCI and DSD before the advent of effective treatments for this condition.

Chronic pyelonephritis is essentially the end-result of long-standing reflux (non-obstructive chronic pyelonephritis) or of obstruction (obstructive chronic pyelonephritis). These processes damage the kidneys, leading to scarring, and the degree of damage and subsequent scarring is more marked if infection has supervened.

Patients may be asymptomatic or present with symptoms secondary to renal failure. Diagnosis is often from incidental findings during general investigation. There is usually no active infection. BP is often raised.

Scars can be ‘seen’ radiologically on a renal USS, renal isotope scan, or CT. The scars are closely related to a deformed renal calyx. Distortion and dilatation of the calyces is due to scarring of the renal pyramids. These scars typically affect the upper and lower poles of the kidneys because these sites are more prone to intrarenal reflux. The cortex and medulla in the region of a scar are thin. The kidney may be so scarred that it becomes small and atrophic.

Aim to investigate and treat any infection, prevent further UTI, and monitor and optimize renal function and BP.

Renal impairment progressing to end-stage renal failure in bilateral cases (usually only if chronic pyelonephritis is associated with an underlying structural or functional urinary tract abnormality).

•Bacteraemia: is the presence of bacteria in the bloodstream.

•Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS): a systemic response to infection (or other clinical insult). SIRS is defined by at least two of the following:

•Fever (>38°C) or hypothermia (<36°C).

•Tachycardia (>90 beats/min in patients not on β-blockers).

•Tachypnoea (respiration >20 breaths/min or PaCO2 <4.3kPa or a requirement for mechanical ventilation).

•WCC >12 000 cells/mm3, <4000 cells/mm3, or >10% immature (band) forms.

•Sepsis: is the diagnosis of infection associated with the systemic manifestations of infection (i.e. SIRS).

•Severe sepsis: sepsis associated with organ dysfunction or tissue hypoperfusion (features including lactic acidosis, oliguria, or acute altered mental state).

•Septic shock: severe sepsis with circulatory shock (hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation), and organ dysfunction or hypoperfusion (features include lactic acidosis, oliguria, or acute altered mental state). It is diagnosed after 30mL/kg of isotonic fluid has been given to reverse any hypovolaemia. Hypotension in septic shock is defined as a sustained systolic BP <90mmHg or a drop in systolic pressure of >40mmHg for >1h, when the patient is normovolaemic and other causes have been excluded or treated. Lactate is >4mmol/L. Septic shock results from Gram-positive bacterial toxins or Gram-negative endotoxins which trigger the release of cytokines [tumour necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin (IL)-1], vascular mediators, and platelets, resulting in vasodilatation (manifest as hypotension) and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

•Refractory septic shock: is defined as septic shock lasting >1h which fails to respond to therapy (fluids or pharmacotherapy).

In the hospital setting, common causes are the presence or manipulation of indwelling urinary catheters, urinary tract surgery (particularly endoscopic—TURP, TURBT, ureteroscopy, PCNL), and urinary tract obstruction (particularly that due to stones obstructing the ureter). Sepsis occurs in ~1.5% of men undergoing bladder outlet surgery. Diabetic patients, patients in ITU, and immunocompromised patients (on chemotherapy and steroids) are more prone to urosepsis.

•Causative organisms in urinary sepsis: E. coli, enterococci, staphylococci, Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, and Proteus.

The principles of management include early recognition, resuscitation, localization of the source of sepsis, early and appropriate antibiotic administration, and removal of the primary source of sepsis. From a urological perspective, the clinical scenario might be a post-operative patient who has undergone TURP or surgery for stones. On return to the ward, they become pyrexial, start to shiver and shake, and are tachycardic and tachypnoeic (leading initially to respiratory alkalosis). They may be confused and oliguric. They may initially be peripherally vasodilated (flushed appearance with warm peripheries). Consider the possibility of a non-urological source of sepsis (e.g. pneumonia). If there are no indications of infection elsewhere, assume the urinary tract is the source of sepsis.

Resuscitate and commence goal-directed therapy within the first 1–3h of diagnosis of sepsis:

•Blood culture (prior to antibiotics) and assess for an infective source.

•Bloods: FBC and serial arterial blood gases (ABGs) to check lactate levels.

•Catheterize and monitor urine output hourly.

•IV fluids. Fluid-challenge patients with sepsis-induced tissue hypoperfusion and hypovolaemia (or high lactate ≥4mmol/L) with a minimum of 30mL/kg of isotonic crystalloid.

•Empirical broad-spectrum IV antibiotics

Assess response to resuscitation—monitor clinical and haemodynamic responses, hourly urinary output, repeat lactate levels.

Complete within the first 6h of diagnosis:

•Administer vasopressors for hypotension that does not respond to initial fluid resuscitation (i.e. NA).

•Maintain mean arterial pressure (MAP) ≥65mmHg.

•Aim for urine output ≥0.5mL/kg/h.

•Central venous pressure (CVP) 8–12mmHg.

•Mixed venous oxygen saturation of ≥65%.

•FBC: the WBC is usually elevated. The platelet count may be low—a possible indication of impending DIC.

•Coagulation screen: this is important if surgical or radiological drainage of the source of infection is necessary. In the absence of anticoagulants, a raised international normalized ratio (INR) of >1.5 or activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) of >60s is a sign of organ dysfunction.

•Urea and electrolytes (U&E): as a baseline determination of renal function and CRP which is usually elevated. Serum creatinine >176μmol/L (from a normal baseline) is a sign of organ dysfunction.

•ABGs: to identify hypoxia and the presence of metabolic acidosis. Lactate ≥2mmol/L is a sign of organ dysfunction, and ≥4mmol/L is a sign of shock.

•Urine output monitoring: <0.5mL/kg/h for 2h is a sign of organ dysfunction.

•Urine culture: an immediate Gram stain may aid in deciding which antibiotic to use. Change antibiotics once sensitivities are available.

•Blood cultures: as above, and prior to giving antibiotics.

•Imaging: guided by clinical findings [i.e. chest X-ray (CXR) looking for pneumonia, atelectasis, and effusions; renal USS may identify hydronephrosis or pyonephrosis; CT if suspicious of renal calculi, urinary tract anomalies, or infected pelvic collections, etc.].

If there is septic shock, the patient needs to be transferred to ITU. Inotropic support may be needed with invasive monitoring (central line, arterial line). Steroids may be used as adjunctive therapy in Gram-negative infections if resuscitation has failed to improve the clinical situation. Naloxone may help revert endotoxic shock. Blood glucose is carefully controlled. This should all be done under the supervision of an intensivist.

Treat the underlying cause. Drain any obstruction and remove any foreign body. If there is a stone obstructing the ureter, preferably arrange for nephrostomy tube insertion to relieve the obstruction. If the patient is stable, an alternative is to take the patient to theatre for ureteric stent insertion. Send any urine specimens obtained for microscopy and culture.

This is ‘blind’ use of antibiotics based on an educated guess of the most likely pathogen that has caused the sepsis. Gram-negative aerobic rods are common causes of urosepsis (e.g. E. coli, Klebsiella, Citrobacter, Proteus, and Serratia). Enterococci (Gram-positive aerobic non-haemolytic streptococci) may sometimes cause urosepsis. In urinary tract operations involving the bowel, anaerobic bacteria may be the cause of urosepsis, and in wound infections, staphylococci (e.g. S. aureus and S. epidermidis) are the usual cause.

Refer to your local microbiology guidelines. Options include:1

•Fluoroquinolones (e.g. ciprofloxacin) exhibit good activity against Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas, but less activity against staphylococci and enterococci. GI tract absorption of ciprofloxacin is good, so PO administration is as effective as IV.

•Aminopenicillin with β-lactamase inhibitor (e.g. co-amoxiclav).

•A third-generation cephalosporin (e.g. IV cefotaxime, ceftriaxone). These are active against Gram-negative bacteria but have less activity against staphylococci and Gram-positive bacteria. Ceftazidime also has activity against Pseudomonas.

•Aminoglycoside (e.g. gentamicin) is often used in conjunction with other antibiotics. It has a relatively narrow therapeutic spectrum against Gram-negative organisms. Close monitoring of therapeutic levels and renal function is important. It has good activity against Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas, with poor activity against streptococci and anaerobes, and therefore should ideally be combined with β-lactam antibiotics or ciprofloxacin.

•If no clinical response to these antibiotics, consider a combination of an antipseudomonal acylaminopenicillin and a β-lactamase inhibitor (e.g. piperacillin and tazobactam; trade name Tazocin®). This combination is active against Enterobacteriaceae, enterococci, and Pseudomonas.

•An alternative second-line drugs are carbapenems (e.g. meropenem, imipenem, ertapenem). Broad-spectrum, with good activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including anaerobes. Meropenem and imipenem are also active against Pseudomonas. Can be given in combination with gentamicin.

•(Consider metronidazole if there is a potential anaerobic source of sepsis.)

If there is clinical improvement, parenteral treatment (IV) should continue for 3–5 days after the infection has been controlled (or a complicating factor has been eliminated), followed by a course of oral antibiotics. Make appropriate adjustments when sensitivity results are available from urine cultures (which may take about 48h).

•Mortality rate: with early diagnosis and goal-directed intervention, mortality from sepsis and septic shock is around 20–30%.

Reference

1Grabe M, Bartoletti R, Bjerklund-Johansen TE, et al. (2015). Guidelines on urological infections. European Association of Urology Guidelines 2015. Available from:  https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/19-Urological-infections_LR2.pdf.

https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/19-Urological-infections_LR2.pdf.

Further reading

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. (2013). Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med 41:580–637.

National Clinical Effectiveness Committee (2014). Sepsis management. National Clinical Guideline No. 6. Published Nov 2014. Available from:  http://www.hse.ie/sepsis.

http://www.hse.ie/sepsis.

Necrotizing fasciitis of the external genitalia and perineum, primarily affecting ♂ and causing necrosis and subsequent gangrene of infected tissues. Also known as spontaneous fulminant gangrene of the genitalia. It is a urological emergency.

Culture of infected tissue reveals a combination of aerobic bacteria (E. coli, enterococci, Klebsiella, S. aureus, Streptococcus spp.) and anaerobic organisms which are believed to grow in a synergistic fashion.

•Local trauma to the genitalia and perineum (e.g. zipper injuries to the foreskin, peri-urethral extravasation of urine following traumatic catheterization, or instrumentation of the urethra).

•Surgical procedures such as circumcision.

•Perianal and perirectal infections.

Fournier’s gangrene is usually related to an initial genitourinary tract infection or skin trauma, or from direct extension from a perirectal focus. Spread of infection is through the local fascia (superficial Dartos and deep Buck’s fascia in the penis, Dartos fascia in the scrotum, Colle’s fascia in the perineal region, and Scarpa’s faof the anterior abdominal wall). Infection produces endotoxins, leading to tissue necrosis that can spread rapidly, and pus produced by anaerobic pathogens (Bacteroides) produces the typical putrid smell.

A previously well patient may become systemically unwell following a seemingly trivial injury to the external genitalia. Early clinical features include localized skin erythema, tenderness and oedema, and sometimes associated LUTS (dysuria, difficulty voiding, urethral discharge). This progresses to fever and sepsis, with cellulitis and palpable crepitus in the affected tissues indicating the presence of subcutaneous gas produced by gas-forming organisms. As the infection advances, blisters (bullae) appear in the skin, and within a matter of hours, areas of necrosis may develop, which spread to involve adjacent tissues (e.g. lower abdominal wall).

The diagnosis is a clinical one and is based on the awareness of the condition and a high index of suspicion. In early stages of disease, abdominal X-ray and scrotal USS or CT may demonstrate the presence of air in tissues. CT can also indicate the extent of disease; however, most surgeons would not delay to image the patient but progress directly to surgical treatment.

•The Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC) score measures different laboratory results (serum CRP, WBC count, Hb, creatinine, sodium, glucose) to give a total score to help stratify patients into risk categories when the initial clinical assessment is equivocal. A LRINEC score of ≥6 should raise the suspicion of necrotizing fasciitis, and a score of ≥8 is strongly predictive; however, this should not be relied on and clinical assessment should take precedence.

•Mortality risk can be assessed by the Fournier’s gangrene severity index (FGSI),1 based on nine clinical parameters: respiratory rate, heart rate, temperature, WBC count, haematocrit, sodium, potassium, creatinine, and sodium bicarbonate levels. Each parameter is valued between 0 and 4, with the higher value given to the greatest deviation from normal. FGSI >9 correlates with  mortality (46–75%);1,2 FGSI <9 has a reported 78–96% chance of survival.1,2

mortality (46–75%);1,2 FGSI <9 has a reported 78–96% chance of survival.1,2

•Resuscitate the patient: obtain IV access, and take bloods [FBC, U&E, liver function tests (LFTs), CRP, clotting, group and save] and blood cultures. Start IV fluids; administer oxygen; check and control blood sugars in diabetics.

•Broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics are given immediately to cover both Gram-positive and Gram-negative aerobes and anaerobes, according to local microbiology guidelines (e.g. combination of co-amoxiclav plus gentamicin plus clindamycin or metronidazole).

•Transfer the patient to theatre as quickly as possible for debridement of necrotic tissue until healthy bleeding tissue margins are found. Extensive areas may have to be removed, but it is unusual for the testes or deeper penile tissues to be involved and these can usually be spared. Send tissue for culture.

•If there is extensive perineal/perianal involvement, faecal diversion with colostomy may be required.

•Wound irrigation with hydrogen peroxide may be used at the end.

•A catheter (urethral or SPC) is inserted to divert urine and allow monitoring of urine output.

•Repeat examination under anaesthetic ± further debridement to remove residual necrotic tissue is required at 24h and then guided by clinical progress.

•Where facilities allow, treatment with hyperbaric oxygen therapy can be beneficial.3

•Treat the underlying comorbidity or cause, i.e. optimize diabetic control.

•Vacuum-assisted closure of wounds can hasten patient recovery.

•Reconstruction can be contemplated when wound healing is complete.

Mortality is in the order of 20–30%. Mortality rates are reported to be higher in patients with a degree of immunocompromise (diabetics, alcohol excess) and those with anorectal or colorectal disease/involvement.

References

1Laor E, Palmer LS, Tolia BM, et al. (1995). Outcome prediction in patients with Fournier’s gangrene. J Urol 154:89.

2Corcoran AT, Smaldone MC, Gibbons EP, et al. (2008). Validation of the Fournier’s gangrene severity index in a large contemporary series. J Urol 180:944–8.

3Pizzorno R, Bonini F, Donelli A, et al. (1997). Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the treatment of Fournier’s gangrene in 100 male patients. J Urol 158:837–40.

Peri-urethral abscess can occur in patients with urethral stricture disease following urethral catheterization and in association with gonococcal urethritis. The bulbar urethra is a commonly affected site in men. These conditions predispose to bacteria (Gram-negative rods, enterococci, anaerobes, Gonococcus) gaining access through Buck’s fascia to the peri-urethral tissues. If not rapidly diagnosed and treated, infection (necrotizing fasciitis) can spread to the perineum, buttocks, and abdominal wall. In immunocompromised patients [i.e. patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection], M. tuberculosis is also a causative organism.

•Tender, inflamed area on the perineum or under the penis.

•Spontaneous discharge of abscess through the urethra (10%).

Extravasation of urine from the abscess cavity may result in cellulitis and a risk of fistula formation.

Emergency treatment is required. The abscess should be incised and drained, an SPC placed to divert the urine away from the urethra, and broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics commenced according to local microbiology guidelines (i.e. IV gentamicin and cephalosporin or co-amoxiclav) until antibiotic sensitivities are known. Any devitalized and necrotic tissue requires immediate surgical debridement.

An inflammatory condition of the epididymis, often also involving the testis (epididymo-orchitis) and usually caused by bacterial infection. It has an acute onset and a clinical course lasting <6wk, presenting with epididymal pain, swelling, and tenderness. It can occur in all age groups and tends to be unilateral.

Infection ascends from the urethra or bladder. In sexually active men aged <35y, the infective organism is commonly N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis, or coliform bacteria (causing urethritis which then ascends to infect the epididymis). In older men and children, the infective organisms are usually common uropathogens (i.e. E. coli). M. tuberculosis (TB) is a rarer cause of epididymitis where the epididymis feels like a ‘beaded’ cord (see  pp. 238–239), and epididymitis and abscess formation can also be encountered after intravesical BCG therapy for bladder cancer.

pp. 238–239), and epididymitis and abscess formation can also be encountered after intravesical BCG therapy for bladder cancer.

A rare, non-infective cause of epididymitis is the antiarrhythmic drug amiodarone, which accumulates in high concentrations within the epididymis, causing inflammation. It can be unilateral or bilateral and resolves on discontinuation of the drug. Some cases of epididymitis in children are also non-infective (idiopathic or as a result of trauma).

Fever; testicular swelling; scrotal pain that may radiate to the groin (spermatic cord) and lower abdomen; erythema of scrotal skin; thickening of the spermatic cord; reactive hydrocele; evidence of an underlying associated infection (urethral discharge, symptoms of urethritis, cystitis, or prostatitis).

•Testicular torsion is the main differential diagnosis. In torsion, pain and swelling are more acute and localized to the testis, whereas epididymitis is mainly preceded by infective symptoms, with pain, tenderness, and swelling tending to be confined to the epididymis.

If any doubt in the diagnosis exists, exploration is the safest option. Colour Doppler USS, which provides a visual image of blood flow, can differentiate between a torsion and epididymitis, but its sensitivity for diagnosing torsion is only 80% (i.e. it ‘misses’ the diagnosis in 20% of cases). Its sensitivity for diagnosing epididymitis is about 70%.

•Torsion of testicular appendage.

•Acute haemorrhage within a testicular tumour.

•FBC, U&E, CRP, and blood cultures (if systemically unwell).

•Urine dipstick ± culture [and nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) of first-void urine if the patient is at risk of STI].

•Urethral swab/culture of any urethral discharge.

Bed rest, analgesia, scrotal elevation, and empirical antibiotics (according to local microbiology guidelines) until culture sensitivities are available.

•For men considered at risk of infection with a sexually transmitted pathogens (C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae), treat with oral doxycycline 100mg bd for 10–14 days plus a single dose of ceftriaxone 500mg intramuscularly (IM).

•For men at risk of C. trachomatis (where gonorrhoea has been excluded), treat with oral doxycycline 100mg bd for 14 days or a fluoroquinolone (i.e. oral ofloxacin 200mg bd) for 14 days.

•Patients should self-refer to genitourinary medicine (GUM) for further input and tracing and treatment of sexual contacts.

•For non-sexually transmitted infection (STI) of the epididymis, and if infection is considered to be due to an enteric organism (including men who have recently undertaken a prostate biopsy or other urinary tract surgery or intervention), give either oral ciprofloxacin 500mg bd for 10 days or ofloxacin 200mg bd for 14 days. An alternative would be co-amoxiclav for 10 days.

•When the patient is systemically unwell, admit for resuscitation and broad-spectrum IV antibiotics such as gentamicin in combination with a cephalosporin or ciprofloxacin. When the patient becomes apyrexial, change to an oral antibiotic, guided by culture sensitivities, to complete a 14-day course. Any underlying cause of infection should be identified and treated (e.g. BOO) to prevent further episodes.

These include abscess formation (requiring incision and drainage), infarction of the testis, chronic pain and infection, and infertility.

Diagnosed in patients with long-term pain in the epididymis. It can result from recurrent episodes of acute epididymitis. Clinically, the epididymis is thickened and may be tender. Treatment is with the appropriate antibiotics (guided by cultures) and analgesia. Epididymectomy is reserved for severe refractory cases.

Orchitis is inflammation of the testis, although it often occurs with epididymitis (epididymo-orchitis) in bacterial infections. Causes also include the mumps virus, M. tuberculosis, syphilis, and autoimmune processes (granulomatous orchitis). The testis is swollen and tense, with oedema of connective tissues and inflammatory cell infiltration. Treat the underlying cause.

Mumps orchitis occurs in 30% of infected post-pubertal ♂. It manifests 3–4 days after the onset of parotitis and can result in tubular atrophy. Ten to thirty per cent of cases are bilateral and are associated with testicular atrophy and infertility.

Further reading

British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (2010). 2010 United Kingdom national guideline for the management of epididymo-orchitis. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. Available from:  https://www.bashhguidelines.org/media/1062/3546.pdf.

https://www.bashhguidelines.org/media/1062/3546.pdf.

Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). 2015 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines: epididymitis. Available from:  https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/epididymitis.htm.

https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/epididymitis.htm.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2017). Scrotal swellings. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Available from:  https://cks.nice.org.uk/scrotal-swellings.

https://cks.nice.org.uk/scrotal-swellings.

Prostatitis is infection and/or inflammation of the prostate, which is described as acute or chronic, and bacterial or abacterial. The classification system1 is from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), part of the National Institute of Health (NIH) in the United States. Chronic abacterial prostatitis is further divided into inflammatory and non-inflammatory types, guided by the results of segmented urine cultures.

I Acute bacterial prostatitis.

II Chronic bacterial prostatitis.

III Chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS): chronic abacterial prostatitis.

IIIA Inflammatory CPPS: WBC in expressed prostatic secretions (EPS), post-prostatic massage urine (VB3), or semen.

IIIB Non-inflammatory CPPS: no WBC in EPS, VB3, or semen.

IV Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis (histological prostatitis).

* Adapted from Nickel JC, Nyberg LM, Hennenfent M, for the International Prostatitis Collaborative Network. Research guidelines for chronic prostatitis: consensus report from the first National Institutes of Health International Prostatitis Collaborative Network. Urology 1999; 54: 229–233 with permission from Elsevier.

Technique described by Meares and Stamey (1968) to help classify the type of prostatitis. It localizes bacteria to a specific part of the urinary tract by sampling different parts of the urinary stream with prostatic massage which produces expressed prostatic secretions (EPS). Where cultures are negative,  numbers of leucocytes per HPF (>10) on microscopy favour a diagnosis of inflammatory CPPS.

numbers of leucocytes per HPF (>10) on microscopy favour a diagnosis of inflammatory CPPS.

Thirty minutes before the test, the patient should drink 400mL of fluid. Retract the foreskin, and cleanse the glans before specimen collection.

•VB1: first 10–15mL of urine voided. Positive culture indicates urethritis (or prostatitis).

•VB2: MSU collection of 10–15mL (the patient is asked to void 100–200mL in total). Positive culture indicates cystitis.

•EPS: the prostate is massaged, while holding a sterile container below the glans to catch secretions. Positive culture indicates prostatitis.

•VB3: first 10–15mL of urine voided following prostatic massage. Positive culture indicates prostatitis.

Prostatitis is estimated to affect 50% of men at some point in their lives. The overall prevalence is reported at 5–14%. Age groups at  risk are 20–50y and >70y.

risk are 20–50y and >70y.

The commonest infective pathogens are Gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae (E. coli in 80% of cases, Klebsiella, Proteus, Pseudomonas). Both type 1 and P pili are important bacterial virulence factors that facilitate infection. Five to ten per cent of infections are caused by Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus and S. saprophyticus, E. faecalis). Acute bacterial prostatitis is often secondary to infected urine refluxing into prostatic ducts that drain into the posterior urethra. The resulting oedema and inflammation may then obstruct the prostatic ducts, trapping uropathogens and causing progression to chronic bacterial prostatitis in ~5%.

Also referred to as chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) or prostate pain syndrome. The underlying aetiology is not fully understood but is likely to be multifactorial. The Multidisciplinary Approach to Pelvic Pain (MAPP) research project has been set up to evaluate the importance and impact of various ‘clinical phenotypes’ for this type of prostatitis. Essentially, patients may have a predominance of certain symptoms or conditions that feature in their disease, suggestive of the main underlying aetiology (i.e. neurological, endocrine, immunological, infectious, neuromuscular, and psychosocial components). The MAPP study aims to identify potential biomarkers relating to these ‘clinical phenotypes’, which will ultimately help with the diagnosis and direct patient-specific management.

Reference

1Krieger JN, Nyberg LJ, Nickel JC (1999). NIH consensus definition and classification of prostatitis. JAMA 282:236–7.

Acute infection of the prostate associated with lower UTI and generalized sepsis. The underlying focus or cause of the initial infection should be identified and also treated (i.e. BOO, urethral stricture, voiding dysfunction, urinary tract stones).

Factors that predispose to genitourinary tract, and then prostatic, colonization with bacteria are:

•Indwelling urethral catheters.

•Intraprostatic ductal reflux.

•Acute onset of fevers, chills, nausea, and vomiting.

•Pain: perineal/prostatic, suprapubic, penile, groin, external genitalia.

•Urinary symptoms: ‘irritative’—frequency, urgency, dysuria; ‘obstructive’—hesitancy, strangury, intermittent stream, urinary retention.

•Signs of systemic toxicity: fever, tachycardia, hypotension.

•Suprapubic tenderness and a palpable bladder if urinary retention.

•DRE: prostate is usually swollen and tender (but may also be normal).

•Serum blood tests: FBC, U&E, CRP.

•Urinalysis, urine culture ± cytology.

•Blood cultures if high pyrexia/systemically unwell.

•Urethral swabs (if indicated to exclude STI).

Further investigation is guided by individual patient presentation and clinical suspicion. Although segmented urine cultures are recommended in some guidelines, prostatic massage should be avoided in the acute, painful phase of prostatitis.

•Antibiotics: refer to local microbiology guidelines. If the patient is systemically well, use an oral fluoroquinolone (i.e. ciprofloxacin 500mg bd) for 10 days. For a patient who is systemically unwell, IV antibiotic options include broad-spectrum penicillin, third-generation cephalosporin or fluoroquinolone, combined with an aminoglycoside (gentamicin) for initial treatment. When infection parameters normalize, IV antibiotics can change to oral therapy, which is continued for a total of 2–4wk.

•Treat urinary retention: urethral, suprapubic, or in-and-out catheter.

Failure to respond to treatment (i.e. persistent symptoms and fever while on appropriate antibiotic therapy) suggests the development of a prostatic abscess. The majority are due to E. coli infection. Risk factors include diabetes mellitus, immunocompromise, renal failure, transurethral instrumentation, and urethral catheterization. Rectal examination demonstrates a tender, boggy-feeling prostate or an area of fluctuance. A transrectal USS or CT scan (if the former proves too painful) are the best way of diagnosing a prostatic abscess. Transurethral resection or deroofing of the abscess is the optimal treatment. Alternatively, percutaneous drainage may be attempted.

•Defined as bacterial prostatitis where symptoms persist for ≥3 months.

•Caused by recurrent infection. Chronic episodes of pain, voiding dysfunction, and ejaculatory problems may be a feature.

Enquire about factors that may be contributing to infection: urinary symptoms, history of renal tract stones, and symptoms suggesting a colovesical fistula in at-risk patients (pneumaturia, history of diverticular disease, pelvic surgery, or radiotherapy). DRE may reveal a tender, enlarged, and boggy prostate.

•Urinalysis, urine culture ± cytology.

•Segmented urine cultures (see  p. 226).

p. 226).

•Urethral swabs (to exclude STI).

•Flow rate and PVR urine measurement.

•Individualized further investigation as indicated (e.g. renal tract imaging to identify stones).

•Prescribe an initial 2- to 4-wk course of antibiotics (fluoroquinolone or trimethoprim)* and then reassess. If initial cultures are positive or the patient has reported positive effects from the treatment, antibiotics can be continued for a total course of 4–6wk.