POP / MASS-CULTURE ART

The rise of popular mass-culture was historically inevitable, as was the advent of an eventual response to it in art. We are still living through the modern technological and democratic epoch that began with the British Industrial Revolution and the American and French Revolutions of the late-eighteenth century. As industrialisation and democratisation have spread, increasing numbers of people have gradually come to share in their benefits: political participation, rewarding labour, heightened individualism, and better housing, health, literacy, and social and physical mobility. Yet at the same time a high price has frequently been paid for these advances: a political manipulation often rooted in profound cynicism and self-interest; vast economic exploitation; globalisation and the diminution of national, regional or local identity; meaningless and unfulfilling labour for large numbers; growing urbanisation; the industrialisation of rural areas, which has grossly impinged upon the natural world; industrial pollution; and the widespread loss of spiritual certainty which has engendered a compensatory explosion of irrationalism, superstition, religious fanaticism and fringe cults, hyper-nationalism, quasi-political romanticism and primitive or industrialised mass-murder, as well as materialism, consumerism, conspicuous consumption and media hero-worship. All of these and manifold other developments have necessarily involved the institutions, industrial processes and artefacts created during this epoch, although not until the emergence of Pop/Mass-Culture Art in the late-1950s did artists focus exclusively upon the cultural tendencies, processes and artefacts of the era.

When Lawrence Alloway wrote of ‘Pop’ in 1958, he belonged to a circle within the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London called the Independent Group. Its members were artists, designers, architects and critics who had come to recognise that by the mid-twentieth century the enormous growth of popular mass-culture and its characteristic forms of communication needed to be addressed – it was not enough snobbishly to consign such matters to the dustbin of lowbrow taste. Naturally, it is only in the modern technological epoch that those wishing to appeal to the growing numbers of consumers of the products of industrialisation have increasingly possessed the large-scale means of doing so. The newspaper printing press, the camera, the radio, celluloid and the film projector, the television set and other mass-communicative technologies right down to those of our own time that make their predecessors look exceedingly primitive (and which supplant their forerunners with increasing rapidity), have each produced fresh types of responses and thus new kinds of visual imagery, all of which obviously constitute highly fertile ground for the artist and designer to explore. Moreover, popular mass-culture possesses energy and potency, and very often its means of transmission such as the cinematic or televisual image, the advertisement, and the poster and magazine illustration, enjoys an immediacy of communication that is not shared by works of greater intellectual complexity: you have to labour a little harder to appreciate, say, the plays of Shakespeare, the symphonies of Beethoven and the canvases of Rembrandt than you do the average Hollywood movie, pop record or billboard poster. So in the 1950s, a decade which saw recovery from war and a growing sense of materialistic well-being in the western world, the Independent Group’s suggestion that artists and designers should draw upon the energy, potency and immediacy of mass-culture proved most timely. Indeed, the very relevance of their notions explains why so many other creative figures further afield soon arrived at exactly the same conclusions independently of the British group and, indeed, even of each other.

Because of this unconnected arrival at the same conclusions, in the main Pop/Mass-Culture Art was never a movement as such, for although in Britain some of the artists who followed its ethos exchanged ideas during the period of its inception, that was not the case in the United States where very few of the participatory artists were ever in close contact with one another. It is therefore perhaps more accurate to describe Pop/Mass-Culture Art as a cultural dynamic rather than a movement. Certainly it was one made ready by historical factors to be born in the late-1950s, although it had been preceded by many forerunners.

Edward Hopper, People in the Sun, 1960. Oil on canvas, 102.6 x 153.4 cm. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

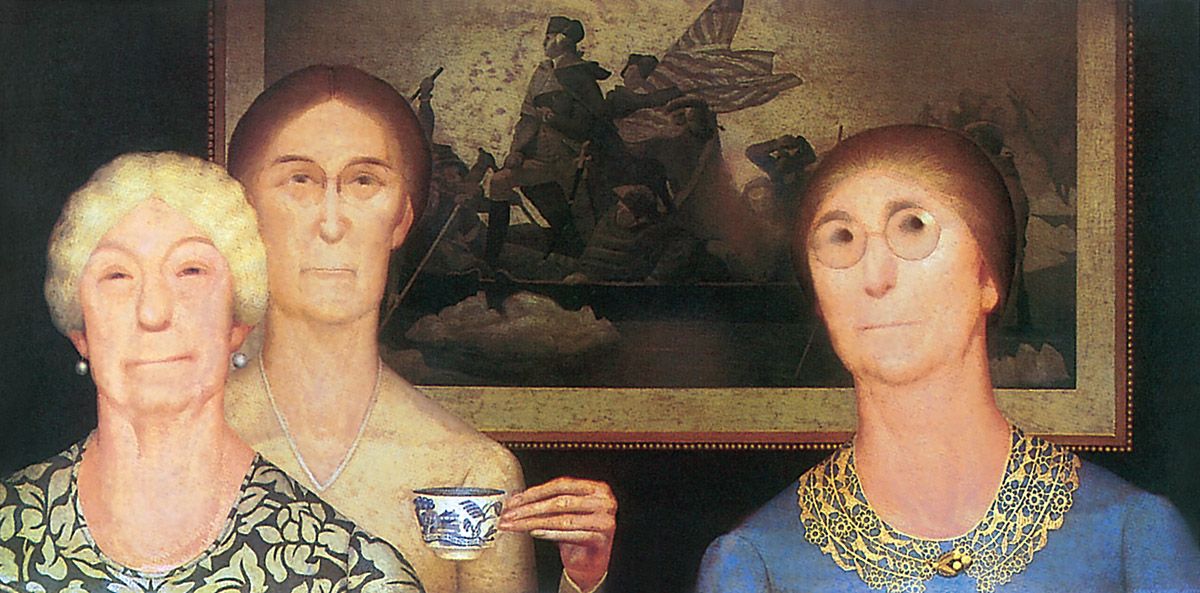

Grant Wood, Daughters of Revolution, 1932. Oil on masonite, 58.8 x 101.6 cm. Cincinnati Art Museum, Cincinnati, Ohio. Art © 2006 Estate of Grant Wood/ Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Forerunners of Pop/Mass-Culture Art

Naturally, large numbers of artists, right up to the mid-twentieth century, had dealt with humanity en masse. Among those who did so most memorably were the eighteenth to nineteenth-century painters Francisco de Goya, J.M.W. Turner and David Wilkie, all three of whom often depicted ordinary people at work and play. The latter two also created consciously ‘low-life’ subjects by representing the common people in their humble dwellings, pubs and at village fairs, thereby revitalising a tradition going back to sixteenth- and seventeenth-century painters such as Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Adrian van Ostade and David Teniers the Younger. Later in the nineteenth century Gustave Courbet, Edouard Manet and Edgar Degas, among others, also looked to the life of common humanity for inspiration, as in the latter artist’s superb study of alienation, In a café of around 1876. This depicts a seemingly hard-hearted man and brutalised woman mentally isolated from one another and spatially separated from us. And Degas was a major influence upon two important painters who addressed popular culture directly: Walter Sickert and Edward Hopper.

Sickert openly followed in the footsteps of Degas the painter of mass-entertainments such as café-concerts and circus life by portraying music-hall scenes and pier-side amusements; later in life he developed scores of canvases from newspaper photos in which he emulated the blurring and graininess of the newsprint almost as much as he represented the images it originally projected. Hopper was inspired by Degas (especially In a Café, which he knew through a 1924 book reproduction) to open up the entire subject of urban loneliness, anomie and alienation, those negative effects of mass-society and mass-culture. Towards the end of his life, in People in the Sun, he even addressed the hedonistic mass sun-worship that has become such a central feature of modern existence.

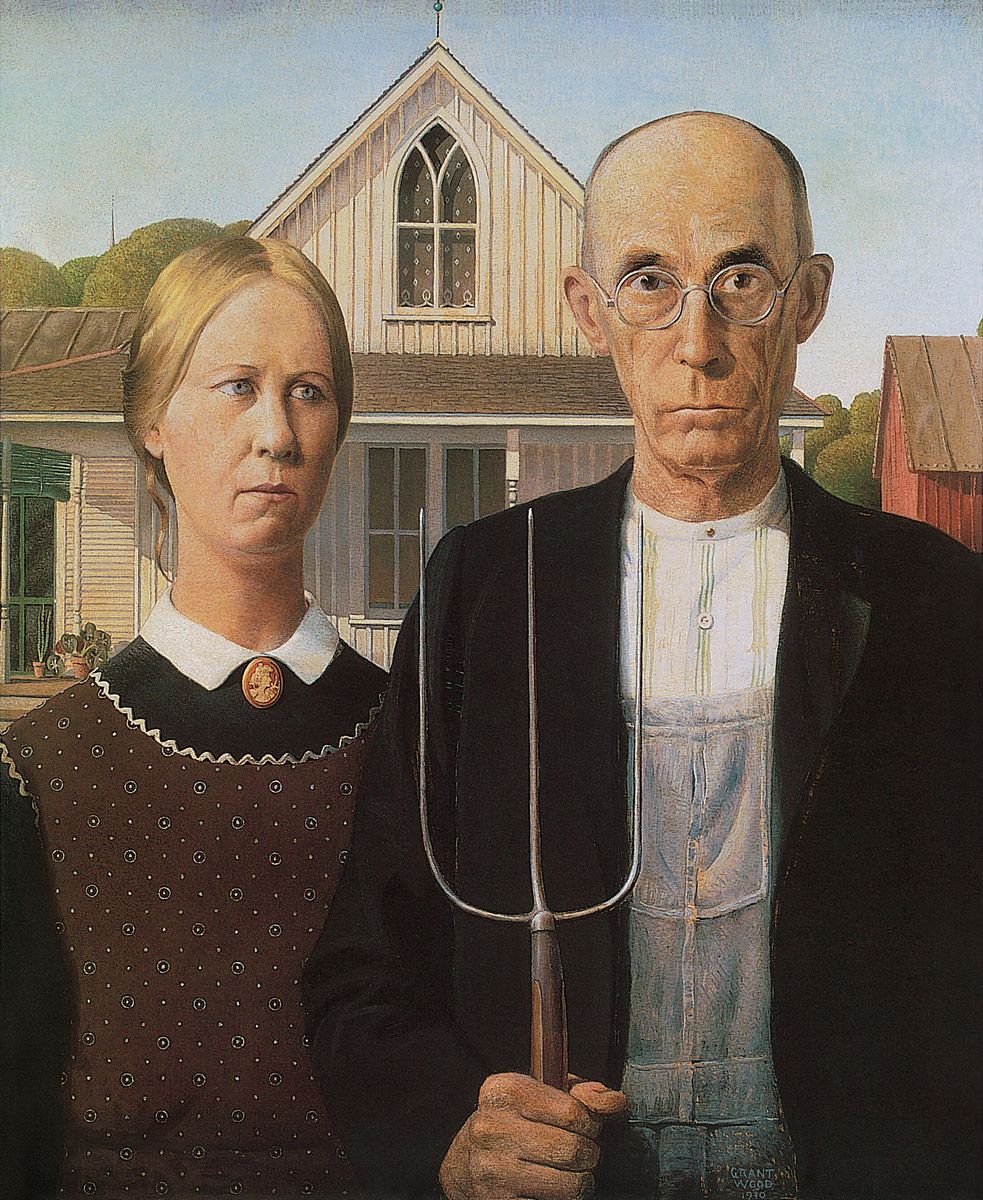

In People in the Sun Hopper’s sunbathers typify a cultural trend. Another artist to create such typifications, but much earlier and with far more satirical bite, was Grant Wood who in 1930 created arguably his most renowned image, American Gothic (see opposite). Here an apparently typical mid-western farmer dressed in denim stands alongside his wife clad in homespun. Behind them is their simple dwelling, with its gothic-inspired arched window. Together they embody the God-fearing, puritanical values of Middle America. Similarly, in 1932 Wood gave us Daughters of Revolution (see above) in which three daunting matrons doubtless belonging to a neo-conservative organisation, the Daughters of the American Revolution, stand before a revered icon of their nationalism, Emanuel Leutze’s 1851 canvas, Washington Crossing the Delaware.

Grant Wood, American Gothic, 1930. Oil on board, 73.6 x 60.5 cm. The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago. American Gothic, 1930 by Grant Wood. All rights reserved by the Estate of Nan Wood Graham/ Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

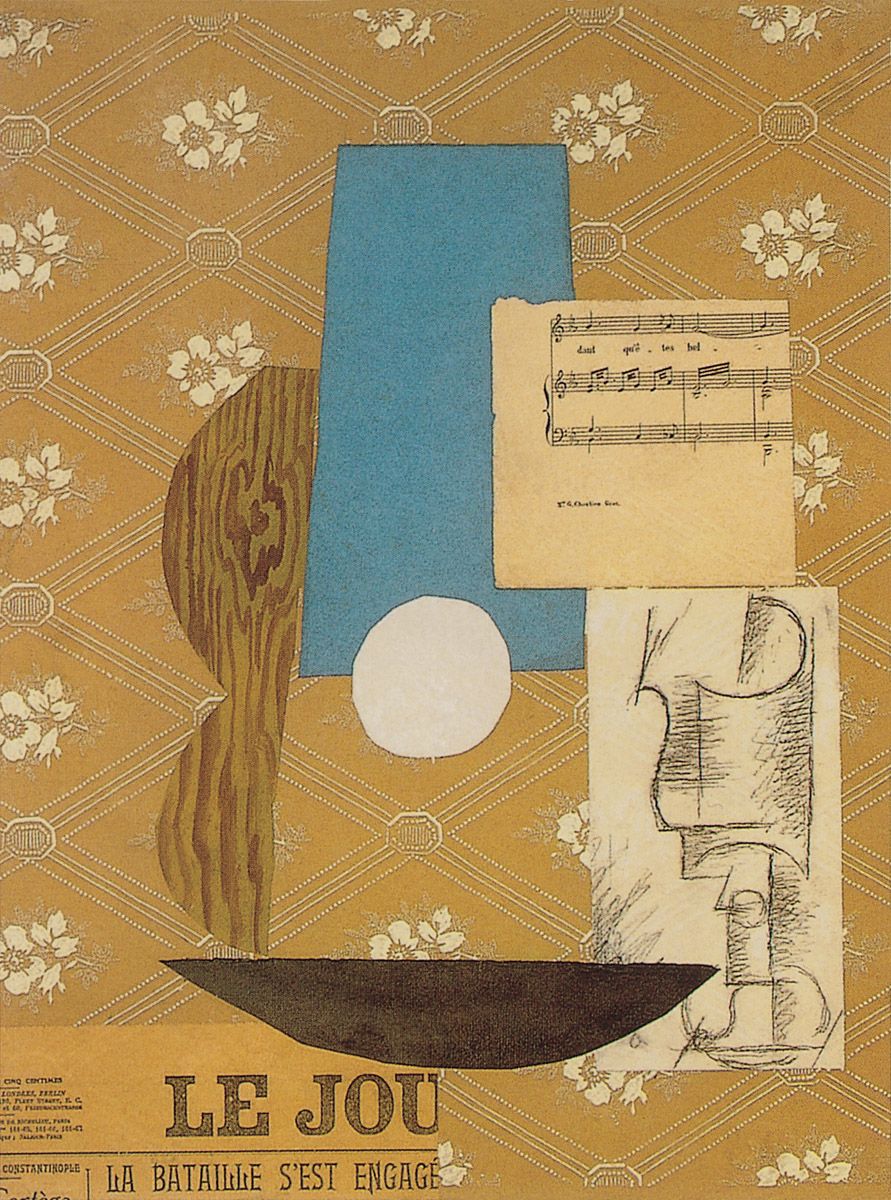

Pablo Picasso, Guitar, sheet-music and glass, 1912. Pasted papers, gouache and charcoal on paper, 48 x 36.5 cm. Marion Koogler McNay Art Institute, San Antonio, Texas.

Like earlier painters of ‘low’ humanity such as Wilkie, Degas and Hopper, Wood represented ordinary life as it is lived, rather than as it is indirectly reflected through the prism of the mass-communications media. Undoubtedly the first artists to treat of the associations of those media and of the popular mass-culture they served were Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso. In 1911 Braque started imitating stencilled lettering in his paintings. This necessarily invokes associations of mass-production, for stencilled lettering is very ‘low culture’ indeed, being primarily found on the sides of packing crates and the like where identifications need to be effected quickly and without any aesthetic refinement whatsoever. By pasting newspapers and the sheet-music of popular songs into his images around 1912-13, Picasso not only virtually invented collage as a new creative vehicle but necessarily opened up the links between art and the mass-communications media.

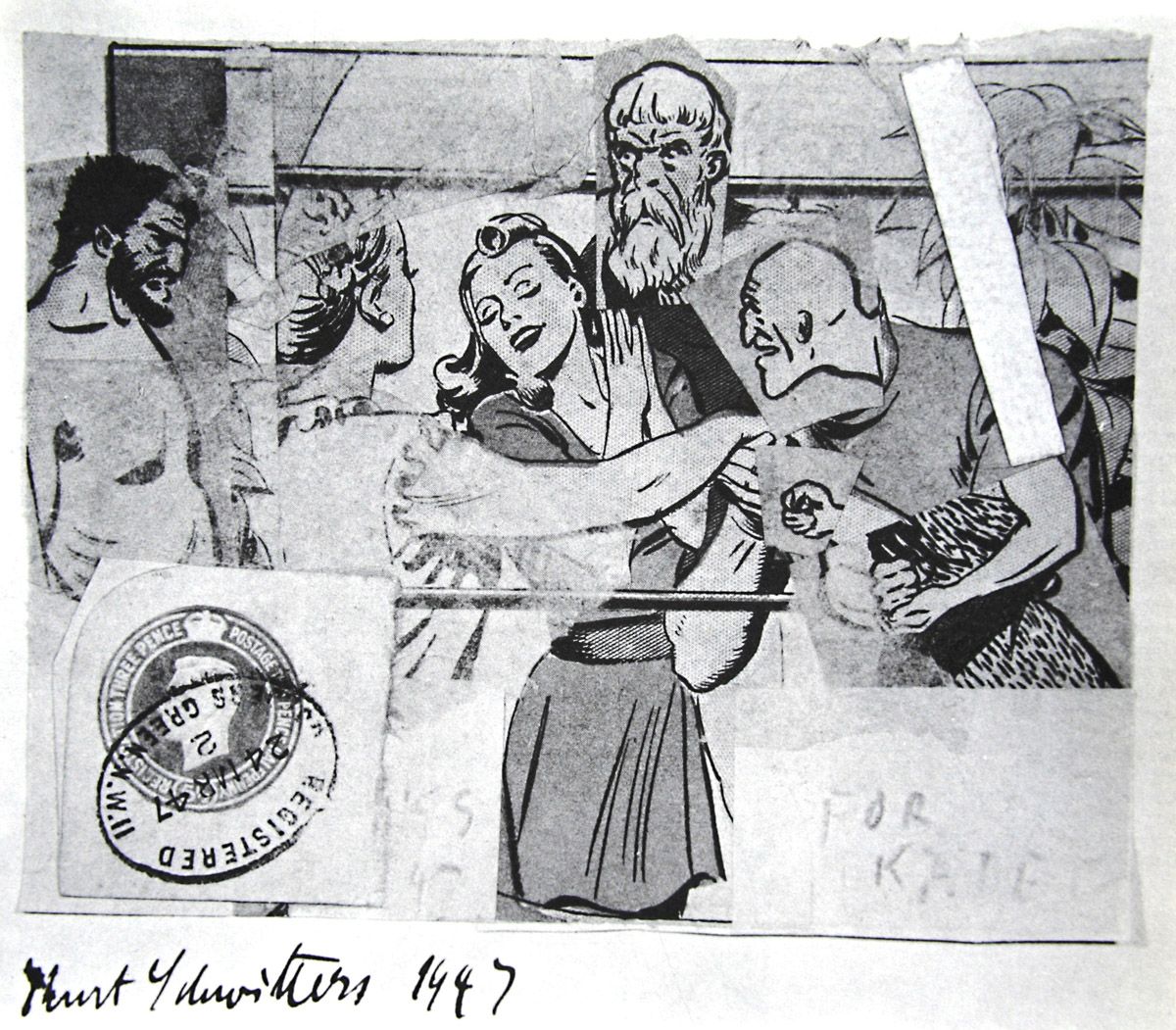

Picasso’s new artistic channel, as illustrated in Guitar, Sheet-music and Glass (see opposite), prompted large numbers of other artists such as Georg Grosz, Raoul Hausmann and Kurt Schwitters to incorporate photographs, scientific diagrams, maps and the like into their images. One or two of these works, such as a Schwitters collage of 1947, would even include comic-strip images. Another German artist, John Heartfield, invented a new art form, the photo-collage, in which much of the material was taken from newspapers. As a result it necessarily included humanity en masse.

Heartfield began to open up this new visual territory using pre-existent material from the early-1920s onwards, and by that time a French-born painter resident in the United States since 1915, Marcel Duchamp, had already created a number of ‘ready-mades’ or sculptures that appropriated industrially mass-produced objects. Whether used alone or in amalgamation with each other, such artefacts not only created new overall forms but simultaneously typified aspects of industrialised society. Perhaps the most notorious of these ‘ready-mades’ was Fountain of 1917, which was simply a ceramic urinal purchased from a hardware store. Duchamp intended to exhibit the work in a vast New York exhibition he had been instrumental in setting up in 1917. A major motivation underlying this show was democratic access (all the thousands of works submitted to it were automatically displayed), and this at a time when democracy was very much in the news because of impending American entry into the First World War. Ultimately Duchamp’s wittily-titled pisspot made a wholly valid point about shared human activity, for all people everywhere have need of urinals from time-to-time. Democracy indeed.

According to Duchamp (or initially at least), a major reason he had chosen to exhibit such an article was to raise it to the status of an art-object by forcing us to recognise the inherent beauty of a mass-produced artefact which normally provokes no aesthetic response whatsoever. This was a doubly clever ploy, for although Fountain was probably destroyed in the early 1920s because Duchamp set no value upon it, the piece certainly got him talked about, an increasingly vital requirement for any artist in the age of mass-communications. (Later, in the 1950s, Duchamp denied he had wanted his objet trouvé to give pleasure to the eye, while simultaneously he created a number of replicas of the artefact to sell to museums clamouring to own such an infamous attack upon art. Like many a creative figure before and since, he therefore had his cake and ate it). Ultimately Duchamp’s Fountain, like his other ‘ready-mades’, completely broke down the distinction between the work of art as crafted object and the work of art as mass-produced artefact. In doing so it necessarily democratised the entire notion of being an artist, for by means of the selfsame process by which a urinal became Fountain – ‘it is a work of art simply because I proclaim it to be such’ – thereafter anyone could become an artist (and quite a few have followed that course ever since). For better or for worse, but mainly for the latter, the democratisation that stands at the very heart of the modern technological, mass-cultural epoch perhaps inevitably began to flood into the field of the visual arts on a massive scale with Duchamp’s ‘ready-mades’, and especially with Fountain.

Apart from any aesthetic thinking, sensory pleasures and moral outrage Duchamp’s object undeniably sparked in 1917 (and still generates by means of its museum replicas), the manner in which it had originally come into being made it automatically act as a signifier of mass-production more generally. Such a process of objects functioning as signifiers would become central to Pop/Mass-Culture Art, as we shall see. But Fountain was not the only precursor in this sphere. From the mid-1910s onwards, and directly as a result of the influence of Picasso’s Cubist explorations, artists often depicted objects taken from mass-culture, not to demonstrate their cleverness in emulating the appearances of things, but instead to draw upon the familiarity of the objects they represented as national or cultural signifiers.

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917. Photograph by Alfred Steiglitz from The Blind Man, May 1917. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg collection.

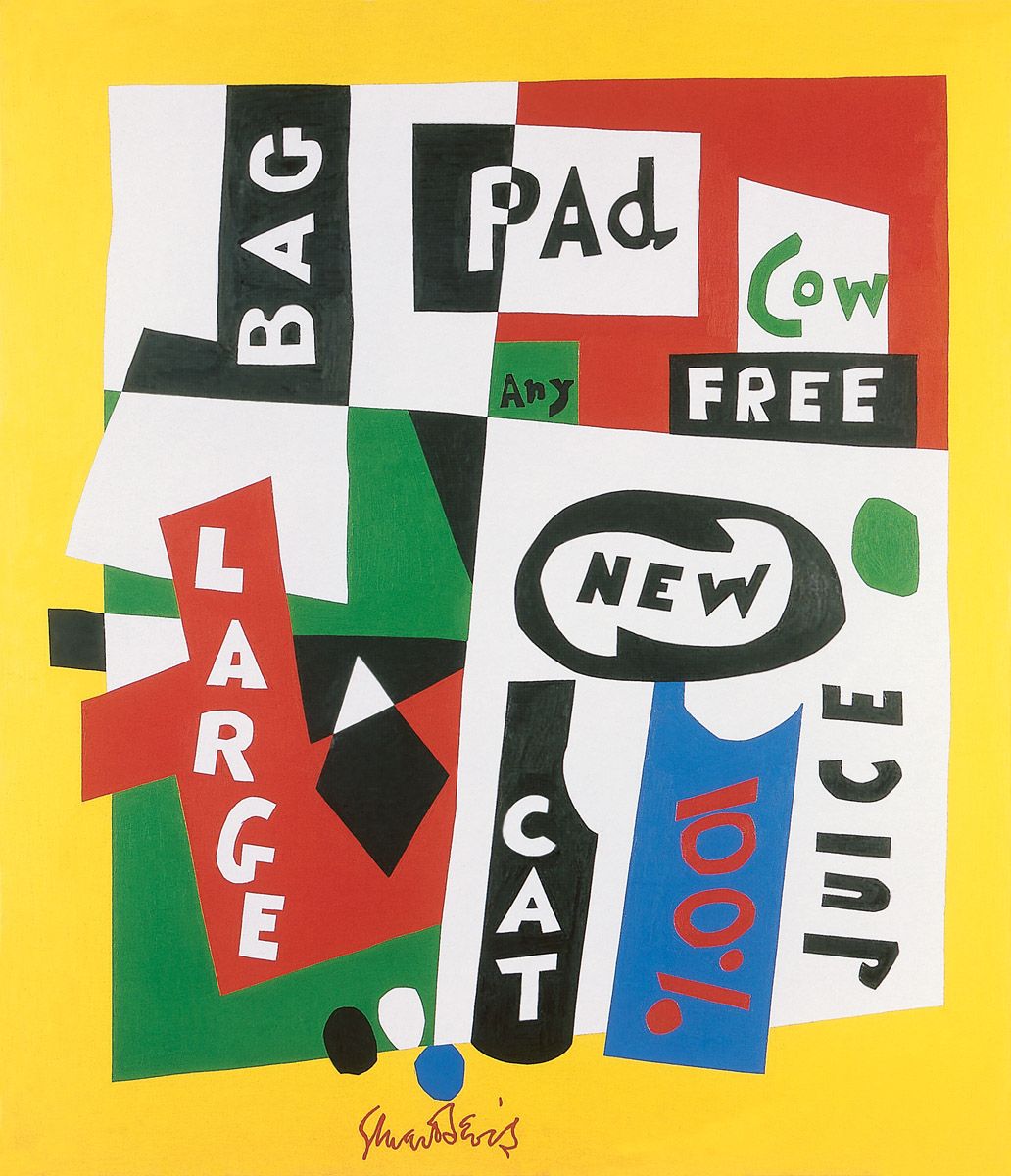

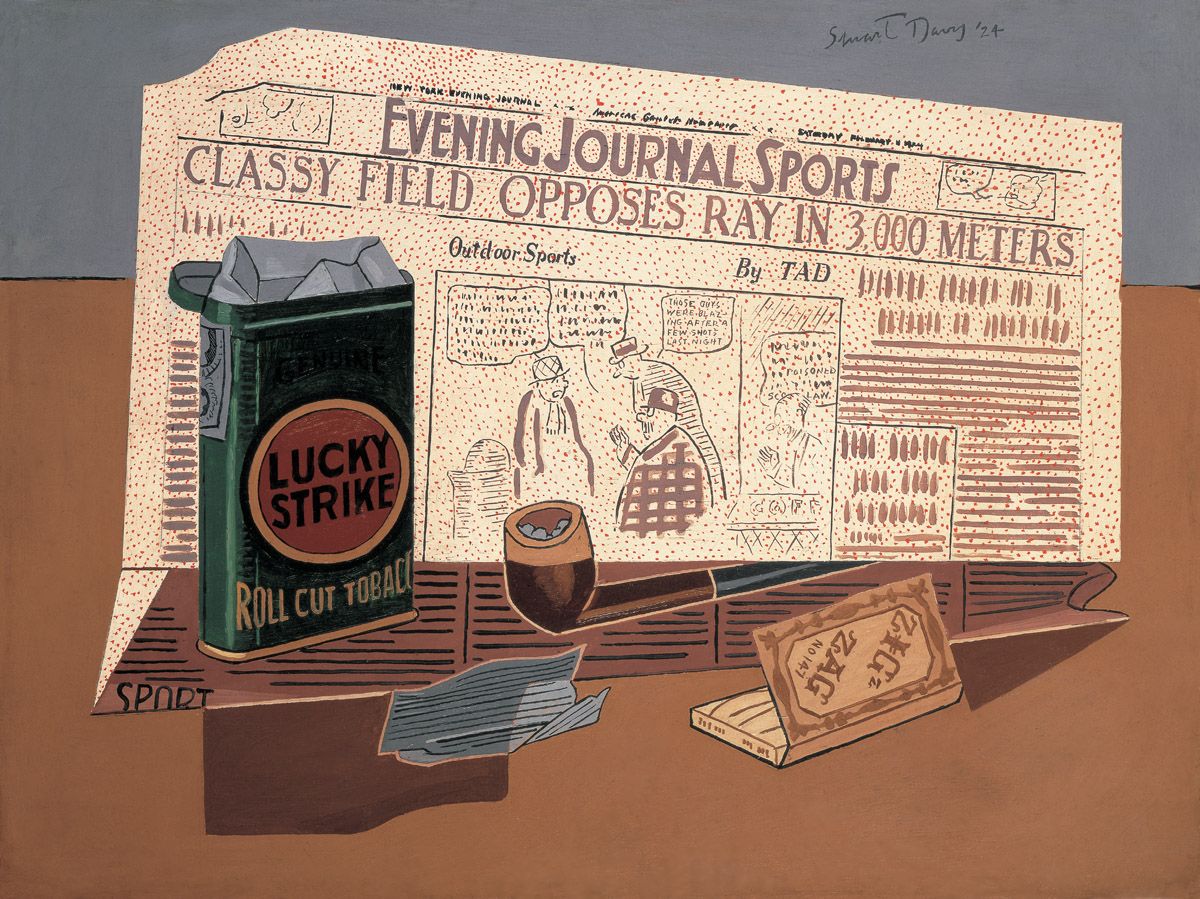

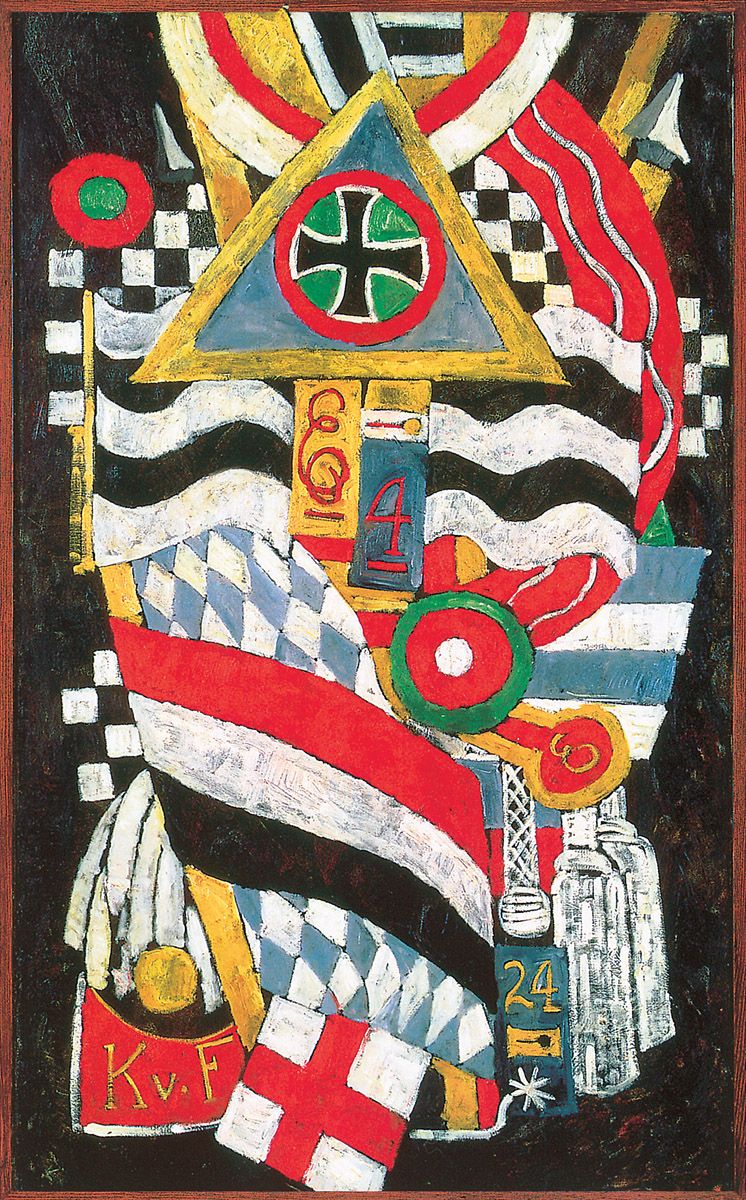

To take national signification first, in 1914-15 (and thus during the First World War) the American painter Marsden Hartley employed flags in several of his canvases, while in oils like his Portrait of a German Officer he did so to denote a military personage, as his title informs us. Cultural signification is especially apparent in early works by the American painter Stuart Davis, who around 1924 created pictures depicting or incorporating Lucky Strike cigarette packs and the Evening Journal sports or the Odol bathroom disinfectant. As with Picasso’s earlier incorporations of cigarette packs and wine-bottle labels, Davis’s imagery hints at a throwaway culture. In the early-1950s the painter would return to mass-communications imagery, fusing abstractive and highly colourful patterning that derived stylistically from late Matisse, with slogans and phrases taken from advertising, supermarket signs and retail exhortations to consume (see opposite). Such images certainly put Davis in the forefront of the growing wave of artists who would prove responsive to mass-culture.

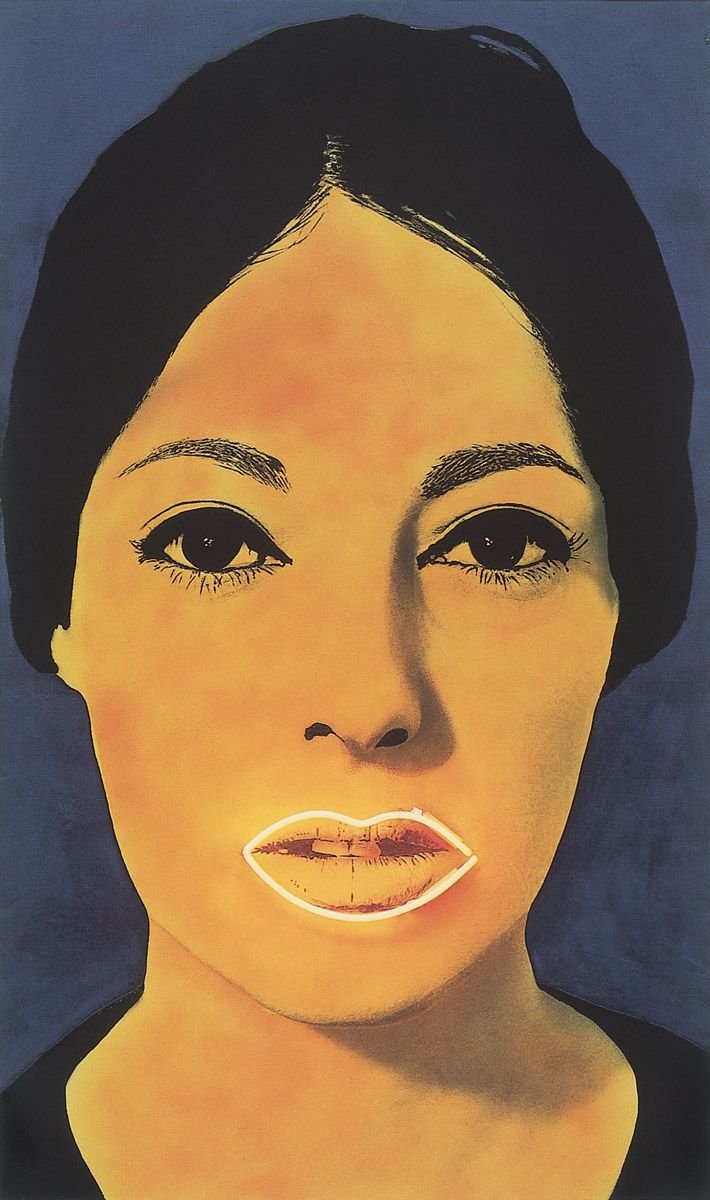

Another painter who had grown increasingly aware of mass-culture was the Surrealist painter, Salvador Dalí. The invasion of France in 1940 had forced him to flee to the United States, and the eight years he lived there affected him deeply, for he was thoroughly exposed to American mass-culture. Not least of all he came into contact with the Hollywood movie industry, designing a film sequence for Alfred Hitchcock and developing a cartoon for Walt Disney (although that short would not be completed and shown until 2003, more than thirteen years after the painter’s death). Dalí especially wanted to create cartoons because he felt they articulated the psychology of the masses. Dalí’s American years undoubtedly made him more populist, more aware of the ability of the media to communicate on a vast scale, and more conscious of the power of money. He returned there most years after 1948, in the mid-1960s not only becoming friendly with Andy Warhol but even undertaking a screen test for him. Slightly later he created a very witty image that stands at the frontier between Surrealism and Pop/Mass-Culture Art. This is a fusion of two faces, one of which had already figured importantly in Warhol’s work, while the other was just about to do so.

Early Pop/Mass-Culture Art in Britain

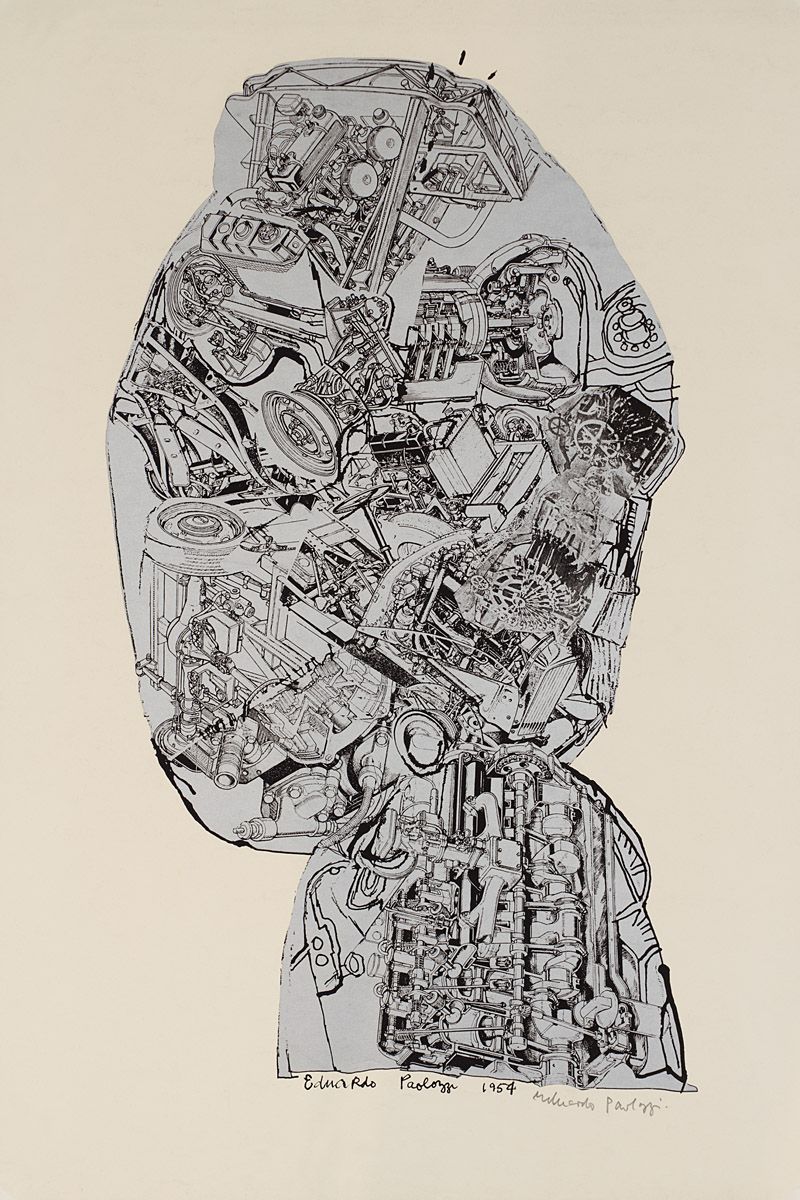

During the late-1940s a further artist deeply influenced by Surrealism strongly anticipated Pop/Mass-Culture Art. This was the British sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi, who would subsequently become a key member of the Independent Group. In 1949 Paolozzi embarked upon a set of highly inventive and witty collages bringing together popular magazine covers, adverts, ‘cheesecake’ photos and the like. Everywhere the banality of the imagery interested him, although in 1971 he was careful to point out that “It’s easier for me to identify with [the tradition of Surrealism] than to allow myself to be described by some term, invented by others, called ‘Pop’, which immediately means that you dive into a barrel of Coca-Cola bottles. What I like to think I’m doing is an extension of radical surrealism.” Surrealism was an exploration of the subconscious and clearly, by the late-1940s that part of Paolozzi’s mind readily absorbed the imagery of popular culture. Subsequently, in the mid-1950s, he would make inventive collages incorporating diagrammatic machine images that would again clearly point to things-to-come.

Paolozzi was not the only artist working in Britain who intuited the future. In 1956 the painter Richard Hamilton created a poster-design collage bearing the ironic title Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?, which brings together many of the images and objects soon to be explored by others. They include household artefacts in abundance, such as a television set supposedly projecting the image of a stereotypically ‘perfect’ face; banal ‘cheesecake’ and ‘beefsteak’ nudes or semi-nudes; a trite Young Romance comic-strip image, apparently enlarged in relationship to its surroundings and framed to hang on the wall; a traditional portrait accompanying it on the wall; a corporate logo adorning a lampshade; and an image of a superstar, in this case Al Jolson seen in the distance. A paddle carried by the Charles Atlas figure bears the word ‘POP’.

Stuart Davis, Premiere, 1957. Oil on canvas, 147 x 127 cm. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, California.

Stuart Davis, Lucky Strike, 1924. Oil on paperboard, 45.7 x 60.9 cm. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

Salvador Dalí, Mao/Marilyn, cover design, December 1971-January 1972 issue of French edition of Vogue magazine, Condé Nast publication, Paris. Photo: Philippe Halsman.

Usefully, in the year after Hamilton created Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? he listed the qualities a new ‘Pop Art’ would need to possess for it to appeal to a mass-audience; it must be:

Popular (designed for a mass audience)

Transient (short-term solution)

Expendable (easily forgotten)

Low cost

Mass produced

Young (aimed at youth)

Witty

Sexy

Gimmicky

Glamorous

Big Business

It might be thought that this constitutes a good, working definition of ‘Pop Art’ but a number of factors demonstrate the need for caution. Firstly, the list was written in a private letter that was not made public until well after the large-scale advent of Pop/Mass-Culture Art, and so it could never act as some kind of manifesto. Secondly, Hamilton was outlining the needs of the mass-audience for so-called ‘Pop Art’ and only therefore implying the needs of its creators, which would not necessarily be the same thing at all. Thirdly, and most importantly, the subject-matter that would be dealt with by artists contributing to the Pop/Mass-Culture Art tradition would quickly range far beyond the parameters Hamilton listed. To take but one example, Andy Warhol would certainly create an art that was popular, mass-produced, aimed at youth, witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous and Big Business, but he would also deal with hero-worship, religious hogwash, the banality inherent to modern materialism, world-weariness, nihilism and death, all matters that certainly did not figure in Hamilton’s shopping list. So does that mean that Warhol should not be linked to Pop/Mass-Culture Art, or does it suggest that Hamilton’s notion of what would constitute ‘Pop Art’ is unnecessarily limiting and inexact? Surely it is the latter. Moreover, much of the art to come would prove to be anything but transient, easily forgotten, cheaply priced or mass-produced.

Marsden Hartley, Portrait of a German Officer, 1914. Oil on canvas, 173.3 x 105 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

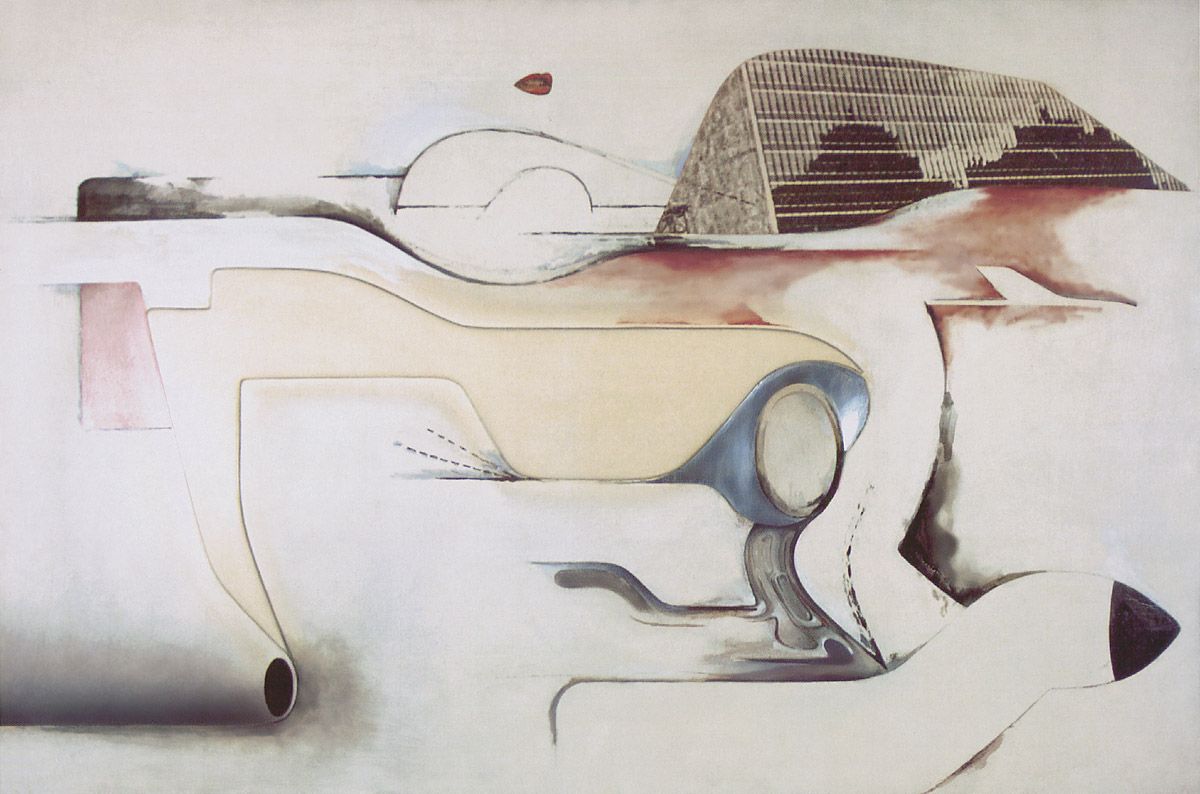

Richard Hamilton, Hers Is a Lush Situation, 1958. Oil, cellulose, metal sheet, collage on panel, 84 x 122 cm. Colin St John Wilson, London.

Hamilton followed up his 1956 collage by producing paintings such as Hommage à Chrysler Corp of 1957, in which he abstracted car body parts; Hers is a Lush Situation of 1958 (see above), in which sections of a 1957 Cadillac are linked to a photo of the glass facade of a building; and $he of 1959-60, in which he brought together areas of a female body, a refrigerator, a toilet seat and a toaster. However, Hamilton would never be a painter interested in churning out long series of works exploring any particular area of mass-culture, and consequently he has never enjoyed the impact of artists such as Lichtenstein and Warhol who would later do so. Instead, he preferred to act more as an aesthetic explorer in the mould of Marcel Duchamp, whom he reveres, and whose damaged Large Glass he replicated in the early 1960s. For this reason the degree to which Hamilton was an aesthetic pioneer is certainly underestimated, especially in America.

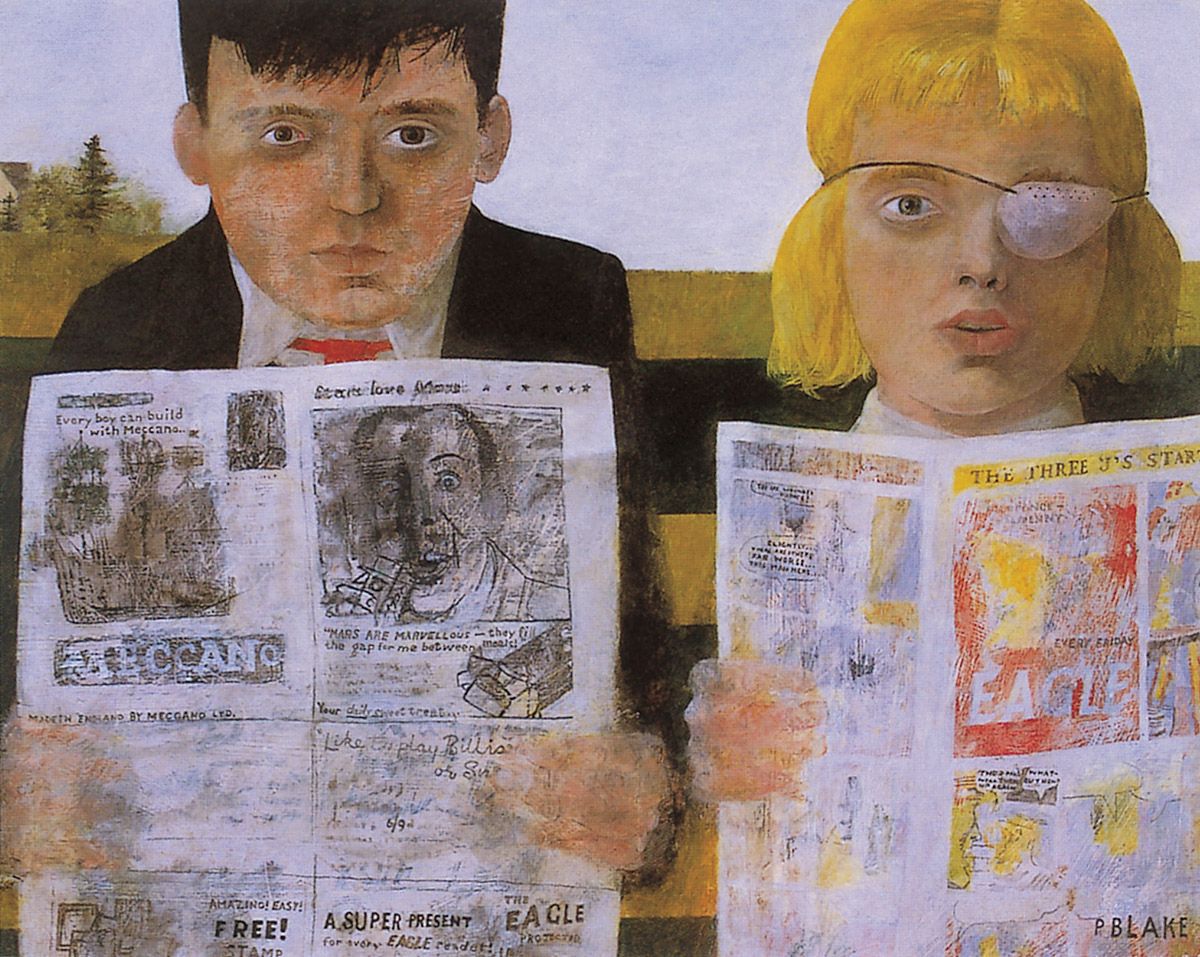

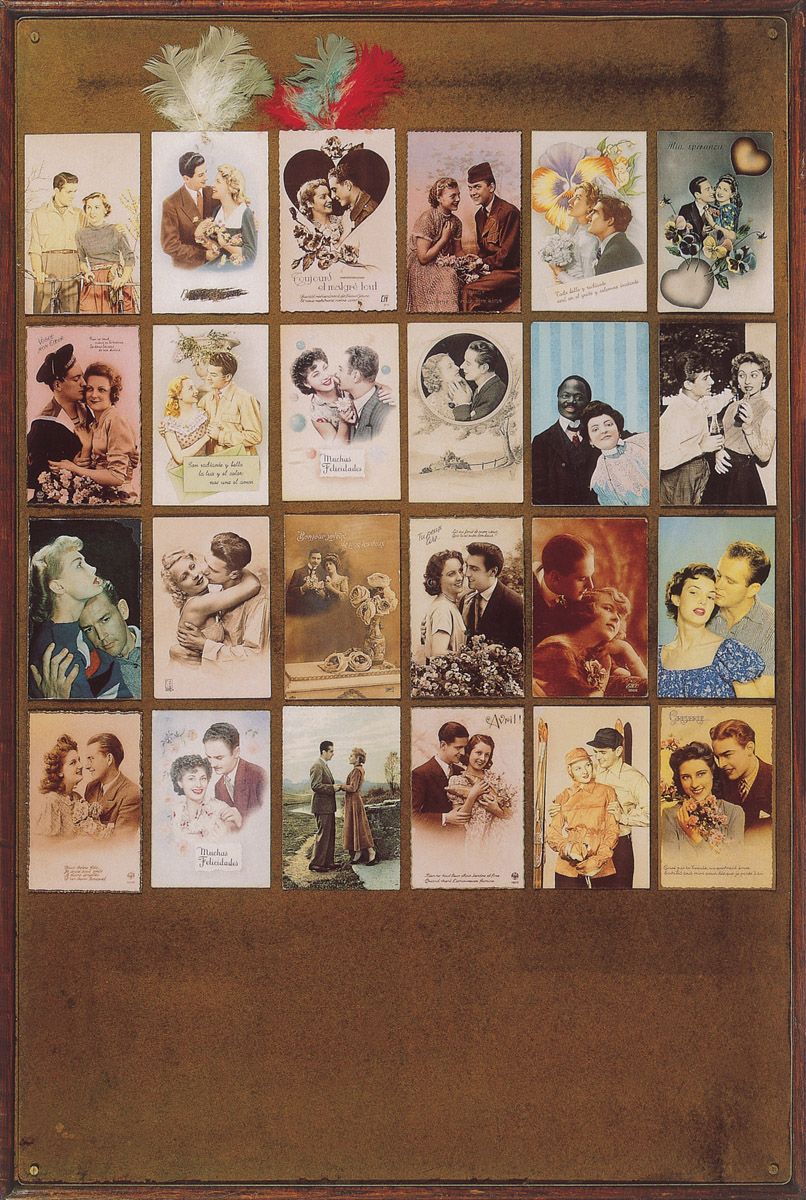

A further British painter was also tapping into the mainstream of popular mass-culture from the mid-1950s onwards, albeit in a highly nostalgic way. This was Peter Blake (Children reading Comics, 1954; Couples, 1959; Got a Girl, 1960-61; Cover for the Beatles’ album, Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, 1967; On the Balcony, 1955-57; Tattooed Lady, 1958; Self-Portrait with Badges, 1961; Love Wall, 1961; The Meeting or Have a Nice Day Mr Hockney, 1981-83). He would later state, “I started to become a pop artist from my interest in English folk art… Especially my interest in the visual art of the fairground, and barge painting too… Now I want to recapture and bring to life again something of this old-time popular art.” Additional stimulus was derived from an early art teacher who had been particularly interested not only in barge painting but also in tattoos, patchwork quilts, and painted and hand-written signs. Usually none of these types of images and patterns had been regarded as art, simply because most such work is naive and untutored (which is, of course, the source of its visual strength and communicative directness). Early in life Blake equally developed an unusually intense interest in collecting postcards, curios, knick-knacks, old tickets, fly posters, metalled advertisements, ‘primitive’ paintings, examples of child art and comic strips, all of which fed into the imagery of his work. The latter attractions are especially clear in Children reading Comics of 1954 (see above). Under such an influence, and armed with an awareness of the works of American painters and illustrators Ben Shahn, Saul Steinberg, Bernard Perlin and Honoré Sharrer (whose pictures he saw in London at a Tate Gallery show held in 1956), Blake also went on to create representations of circus folk, wrestlers and the like. This phase of his output came to a climax with On the Balcony of 1955-7 in which two simulated photos of members of the Royal Family on the balcony of Buckingham Palace are surrounded by five children, other images of people on balconies (including one by Manet), and a mass of small pictures taken from art and life, including the latter as represented by the mass-media Life magazine. By 1959, when Blake created Couples (see opposite), his interest in popular printed ephemera could form the stuff of art, by drawing our attention to cultural ubiquity and the narrow borderline between sentiment and sentimentality.

By the late-1950s Paolozzi, Hamilton and Blake were still unknown in the United States, and thus they could not contribute to the rise of Pop/Mass-Culture Art there. So what did propel the emergence of that creative dynamic on the western side of the Atlantic Ocean?

Sir Peter Blake, Children reading Comics, 1954. Oil on hardboard, 36.9 x 47 cm. Tullie House Museum and Art Gallery, Carlisle, Cumbria, UK.

The Rise of Pop/Mass-Culture Art in America

Primarily an important artistic movement contributed towards the advent of Pop/Mass-Culture Art in America, albeit in an entirely antithetical way. This was the prevailing avant-garde tendency of the day, Abstract Expressionism (which was also termed ‘Action Painting’ and ‘New York School painting’). Such a movement had emerged in the mid-1940s and it flourished during the 1950s, in the process shifting the centre of art-world power from Paris to New York. American artists and émigrés to New York, who included Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Hans Hofmann, Adolph Gottlieb, Clyfford Still, Robert Motherwell, Arshile Gorky, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman and Helen Frankenthaler, all forged a completely innovative aesthetic by exploring new expressive, painterly, formal, colouristic and psychological dimensions to painting and drawing. For the most part theirs was an art committed to non-representation, although the imagery and scale of their works often addressed reality metaphorically (as with, say, the paintings of Motherwell dealing obliquely with the Spanish Civil War, and the canvases of Pollock which were openly intended to articulate his responses to the age of the radio, the automobile and the atomic bomb). Several members of the New York School, most notably Pollock, came close to fulfilling an automatism which was implicit in Surrealism but which had not been thoroughly explored by members of that earlier group, while most of the Abstract Expressionists carried through the gestural implications of earlier phases of Expressionism. But what connected all of these painters was a shared determination to create an art that would reach down through the subconscious to touch core values of spirituality, emotion, seriousness, intellectual complexity and authentic experience.

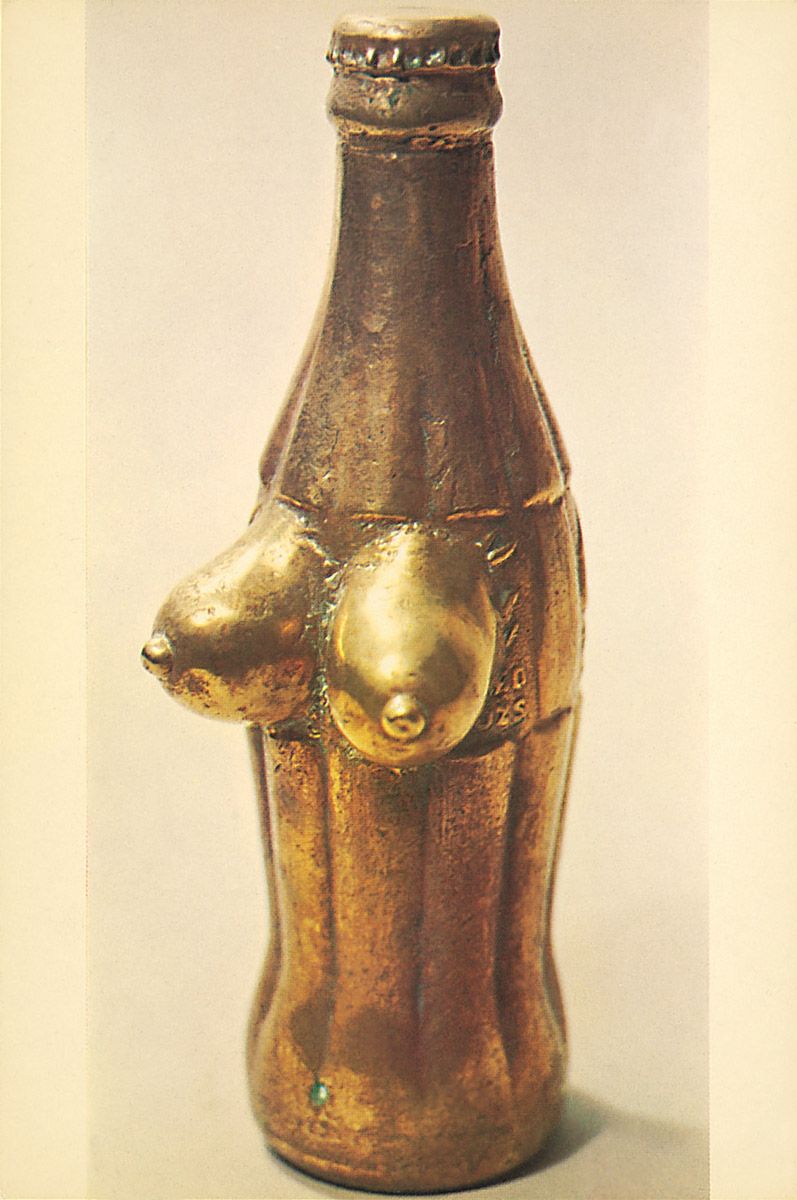

It is perhaps to be expected that such noble aspirations would engender a reaction, and certainly they did so amongst the next generation of artists who felt that the territory explored by the Abstract Expressionists had been thoroughly exhausted, leaving them nowhere to go. Undoubtedly these younger figures were creatively committed, but as they looked at the world of the late-1950s they gradually turned their backs on the goals so prized by their immediate forebears. After all, where were such lofty qualities to be readily found in an increasingly cynical, emotionally fearful, youth-orientated, irreligious and hedonistic society filled with the bogus posturing of advertising men and the materialistic emptiness of mass-consumption? If an artist holds a mirror to society, then surely he or she should be reflecting the emergence of Bill Haley and Elvis Presley around 1955, the advent of Disneyland and McDonalds that selfsame year, the automotive and aeronautical revolutions that really took off in the 1950s, the emergence of a new generation of teenagers around 1960 (the so-called ‘baby-boomers’ sired by military personnel returning from service in World War II some fifteen years earlier), the very moment when television began to outstrip cinema as the principal means of global visual communication, and the sexual revolution that began when the oral contraceptive pill became available in 1960-1. Accordingly, they ditched the values of Abstract Expressionism and instead adopted a ‘cool’ or emotionally distanced response to the world, an orientation towards youth and hedonism, and a witty irreverence about everything ranging from religion to art, if not even a cynicism regarding the world they had inherited. Such an attitude allowed them to comment ironically upon the false promises of admen and the vacuity of mass-consumption, as typified by its fetishes or objects of worship such as the Coca-Cola bottle, the hamburger, the comic-strip, the pop idol and the Hollywood superstar.

The rejection of the values of Abstract Expressionism can already be witnessed prior to the mid-1950s, for example, in Robert Rauschenberg’s total erasure of a drawing by Willem de Kooning in 1953. (This highly symbolic neo-Dadaist or anti-art gesture comprises a virtually blank sheet of paper that now sits in a frame and resides in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Originally, it may have equally demonstrated Rauschenberg’s complete disdain for the financial value invested in such an object but today, of course, it is worth a fortune.) In that same year Rauschenberg also made all-white paintings in which the shadows cast by the spectator generate the only visual dynamic in the works. Such a transfer took to its logical conclusion the notion of Duchamp and others that it is the viewer who completes the communicative circuit of any given work of art, and thereby creates its ultimate significance. This is certainly undeniable, if hardly profound.

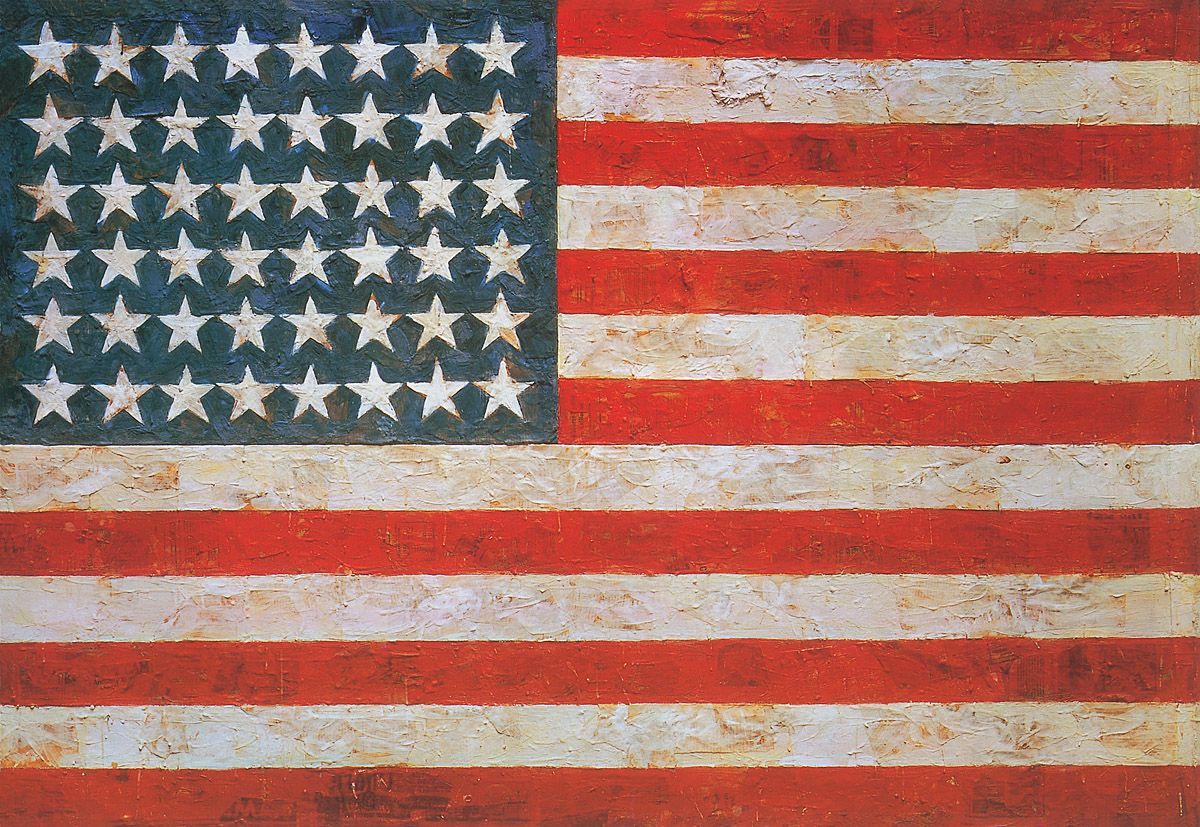

Jasper Johns, Flag, 1955. Oil and collage on canvas, 107 x 153.8 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Art © 2006 Jasper Johns/ Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

No less importantly, in 1953 Larry Rivers broke with Abstract Expressionism by reworking the imagery of a hallowed representation of American history, Emanuel Leutze’s painting of George Washington crossing the Delaware river, which we have already seen indirectly because it appears in the background of Grant Wood’s Daughters of Revolution. Rivers gave the subject the full Abstract Expressionist treatment of heavily gestural brush marks, and by such messy means he attained his stated intention of communicating the true discomfort that George Washington and his fellow-revolutionaries must have felt when making a winter river-crossing, feelings that are not imparted by the absurdly heroic posturing of Leutze’s figures. As well as attacking the orthodoxy of Abstract Expressionism by placing its painterly approach at the service of history painting, Rivers also used the re-working of the Leutze as a means of undermining the values of conservative America, which was then going through a period of extreme Cold War paranoia.

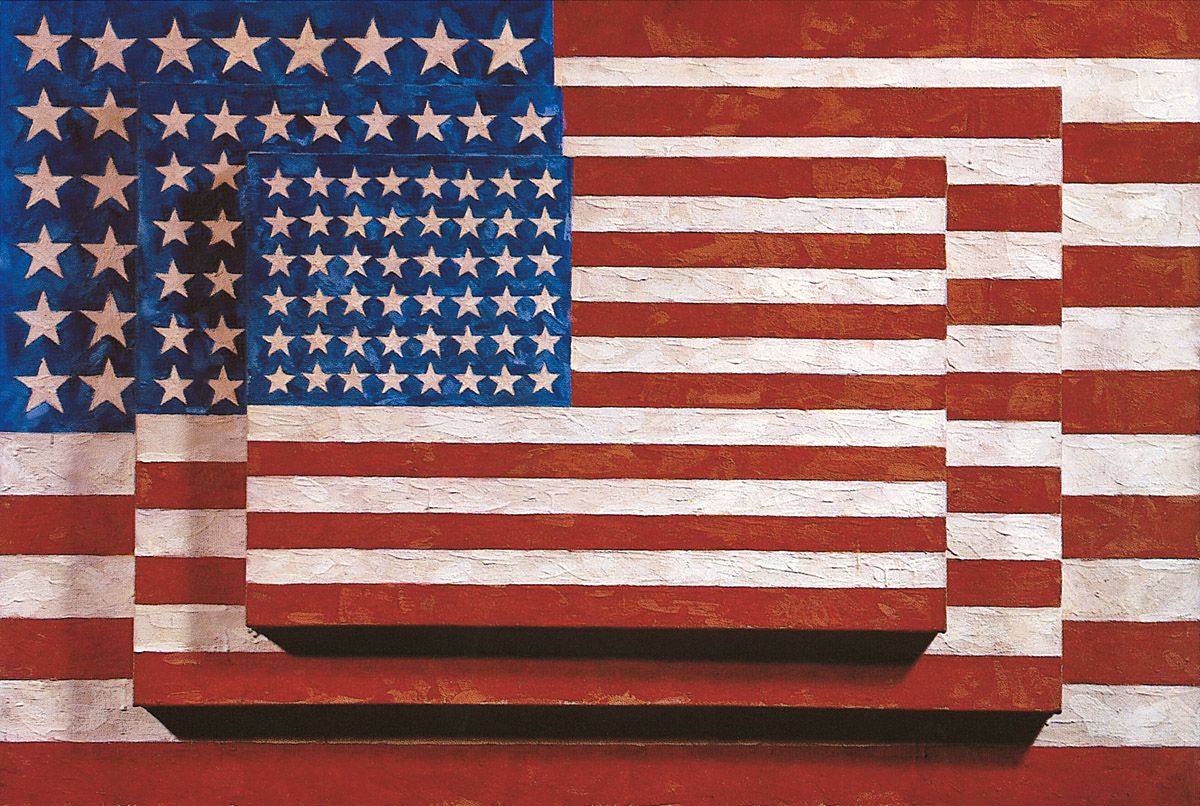

In 1954 a friend and neighbour of Rauschenberg’s in Manhattan, Jasper Johns, created a parallel to the Rivers image, and did so in iconic terms not unlike those of the latter, by beginning a series of paintings and drawings of the American flag (see above). Over the next four or so years he would give this most familiar and integral of all emblems of American culture an apparently gestural painterly treatment similar to that of Abstract Expressionism (although to perceive a subtle contradiction in his technical approach, see the commentary below the reproduction). In the process, he fused imagery that enjoys profound symbolic value with a conscious denotation of the act of painting, just as Rivers had done in 1953. However, the apparent energisation of the surfaces of the paintings and drawings does not break down the flag in any way, as Rivers had done with his representation of George Washington and others. This is because Johns was equally concerned to emphasise the purely formal and colouristic qualities of the symbol. In most of the works he furthered this aim by isolating the banner within the overall design, while in a number of the pictures (such as representations of the flag in white) he also made the emblem hard to see. In other Flag paintings he varied the colours of the sign, thereby subverting our notions of the real. Some of the images (such as the very first of the Flag paintings) are built up over layers of newsprint, and where these levels remain evident they necessarily introduce mass-media associations. As always, Johns emphasised the flatness of the flag by avoiding any notions of spatial recession – constantly it remains a frontal arrangement of shapes on a flat background. The end result of all these factors is to make the flags appear physically disembodied and drained of iconic, nationalistic purpose. Such disassociation would have an enormous impact upon Andy Warhol in particular when he saw the Flags pictures in Johns’s debut solo exhibition held at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York in January 1958, as he would subtly make clear in paintings he would produce in the 1960s.

Just a couple of months after Leo Castelli had exhibited Johns’s Flag paintings early in 1958, the dealer displayed Robert Rauschenberg’s first Combine paintings, so-named because of their amalgamation of flat, painted surfaces with three-dimensional objects. The gesturality of Abstract Expressionist brushwork is still very much in evidence in these works and, indeed, it would never really disappear from Rauschenberg’s output thereafter, being a useful way of both imparting enormous energy to the images and necessarily making analogous points about the dynamism of the contemporary world. Additionally, Rauschenberg occasionally pasted newspaper photographs and comic-strip material into the Combines, thereby creating mass-media associations, while in some of the works he introduced a particular icon of popular culture, the Coke bottle, and did so in rows that ineluctably induce thoughts of both mass-production and mass-consumption. In yet other Combines Rauschenberg incorporated actual Coca-Cola signs, thus touching upon signification directly.

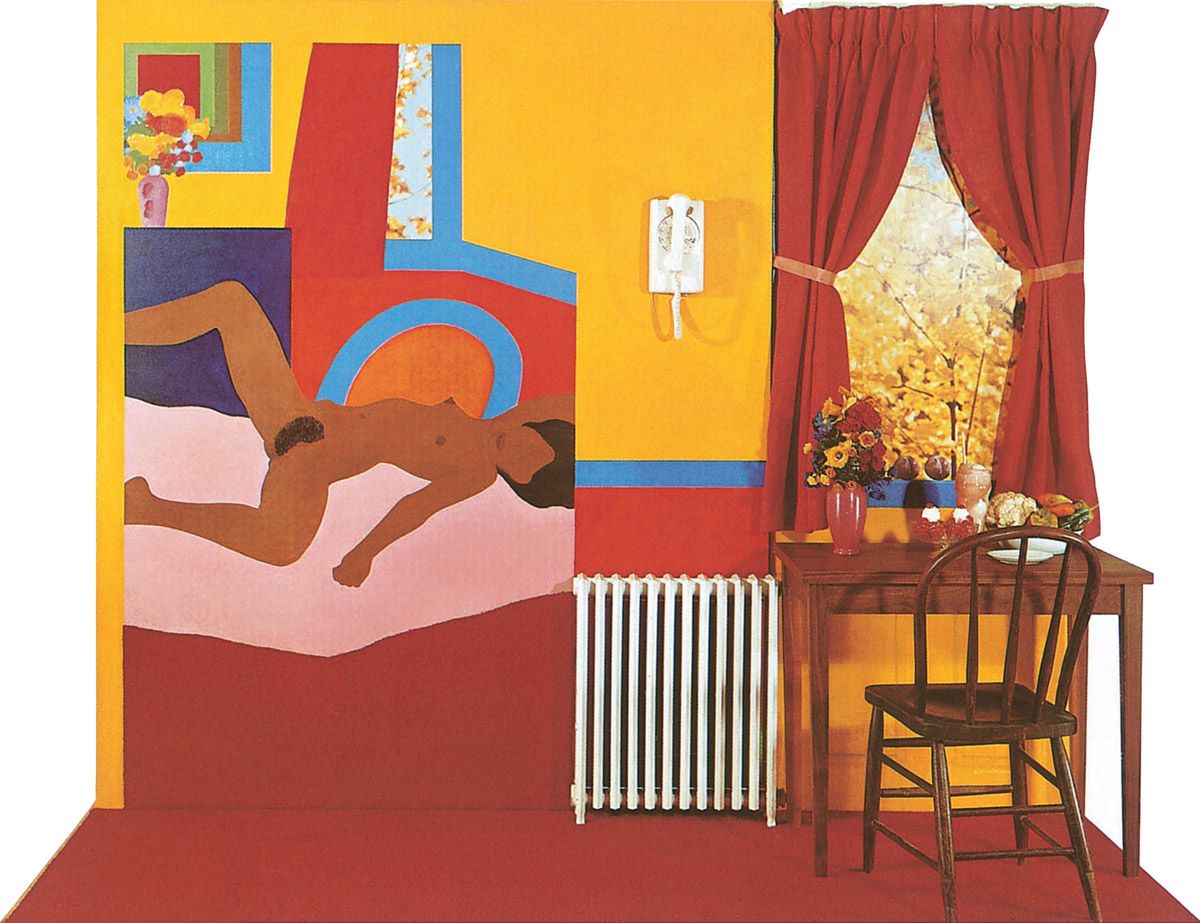

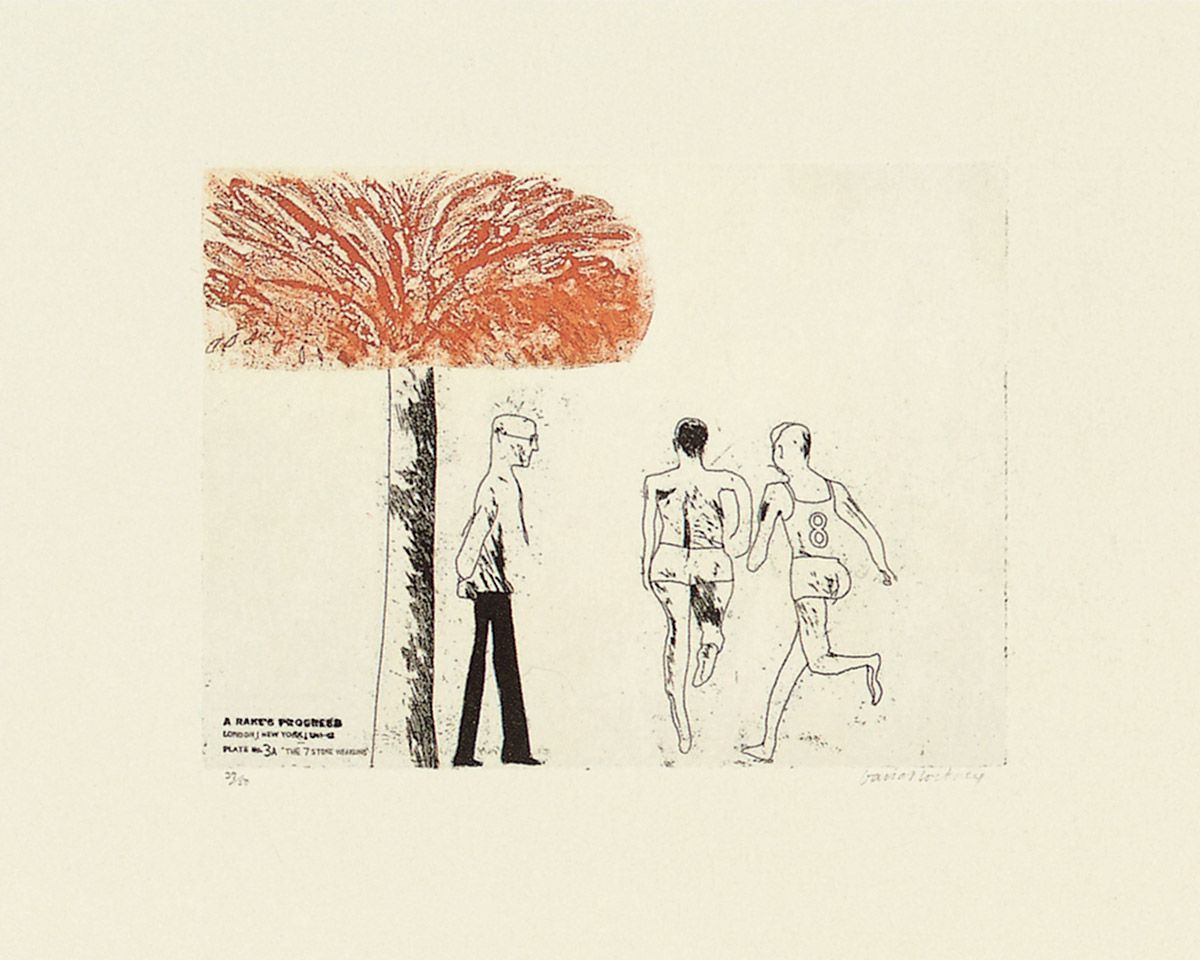

The 1958-61 period also saw the debut exhibitions in New York and Los Angeles of further artists who would soon be prominent in the Pop/Mass-Culture Art dynamic. They included Marisol, Allan D’Arcangelo, Ed Kienholz, Jim Dine, Claes Oldenburg, Richard Smith and Tom Wesselmann, all of whom are discussed below. On the other side of the Atlantic, a number of emergent Pop/Mass-Culture Art painters came together in 1959 as post-graduate students at the Royal College of Art in London. They included David Hockney, Allen Jones and Peter Phillips who each receive further mention in this book.

The Triumph of Pop/Mass-Culture Art

The international emergence of Pop/Mass-Culture Art finally took place in 1961-2. In London the 1961 ‘Young Contemporaries’ exhibition served notice to the world that Hockney, Jones, Phillips, Patrick Caulfield and others were bringing a new ‘Pop’ sensibility into being. The following year saw shows in New York, Los Angeles and London of works by Claes Oldenburg, Jim Dine, James Rosenquist, Roy Lichtenstein, George Segal, Robert Indiana, Peter Blake, Andy Warhol, Tom Wesselmann and Wayne Thiebaud who all made the public more aware of mass-production and/or mass-culture. By the time these exhibitions were mounted, Leo Castelli had been followed by a growing number of dealers, such as Ivan Karp, Richard Bellamy, Sidney Janis, Martha Jackson, Eleanor Ward, Allan Stone and Irving Blum, who proved equally receptive to Pop/Mass-Culture Art. Naturally, they quickly realised the economic potential such work enjoyed, especially to those many collectors, museum directors, members of their boards and ordinary art-lovers who had never engaged with abstract art.

Amid all these debuts a particularly significant show was mounted by Claes Oldenburg outside the normal gallery system. This was the first of his two The Store exhibitions, which took place between December 1961 and January 1962. For this display Oldenburg rented a shop in a depressed, downtown part of Manhattan and filled it with pieces that emulated everyday consumer objects. These he nailed to the walls, hung from the ceilings and arranged on the floors. They all bore price tags and were surrounded by advertising signs that were intended to break down the barriers not only between art and reality but also between the art gallery and the shop, and between the artist and the dealer (for Oldenburg was constantly present to act in that capacity during the show). In September 1962, with his second The Store exhibition, held at the midtown Green Gallery, Oldenburg moved in the direction of greater refinement by making fewer but bigger emulations of consumer objects, such as a larger-than-life hamburger, a gigantic ice cream cone and a huge slice of chocolate cake. Again, and by dint of the physical augmentation of size that was already becoming his stock-in-trade, the objects and comestibles of everyday life were brought out from under the noses of a public that took them for granted and given a new measure of cultural life.

Another important group show opened in New York on the last day of October 1962 and it finally set the seal on the international emergence of Pop/Mass-Culture Art. The ‘New Realists’ exhibition mounted at the Sidney Janis Gallery brought together an international spectrum of artists ranging from the Americans Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, James Rosenquist, Claes Oldenburg, Jim Dine, Robert Indiana, George Segal, Tom Wesselmann and Wayne Thiebaud, to the Europeans Peter Blake, Arman, Peter Phillips, Martial Raysse and Mimmo Rotella, all of whom are discussed below. Confronted with works that included Oldenburg’s assemblage The Stove, which featured a real stove topped by plaster food, Jim Dine canvases that incorporated real objects, a sculptural ensemble of a dinner table by George Segal, a James Rosenquist oil juxtaposing a car grill with a kissing couple and a tangle of spaghetti, an Arman accumulation of swords and rapiers, Roy Lichtenstein’s picture of an exploding MIG fighter, still-lifes of consumer objects and food by Tom Wesselmann and Wayne Thiebaud, and Andy Warhol’s paintings of Campbell’s Soup cans – both singly and in a group of 200 – the New York art world was hit “with the force of an earthquake”, to quote the critic Harold Rosenberg.

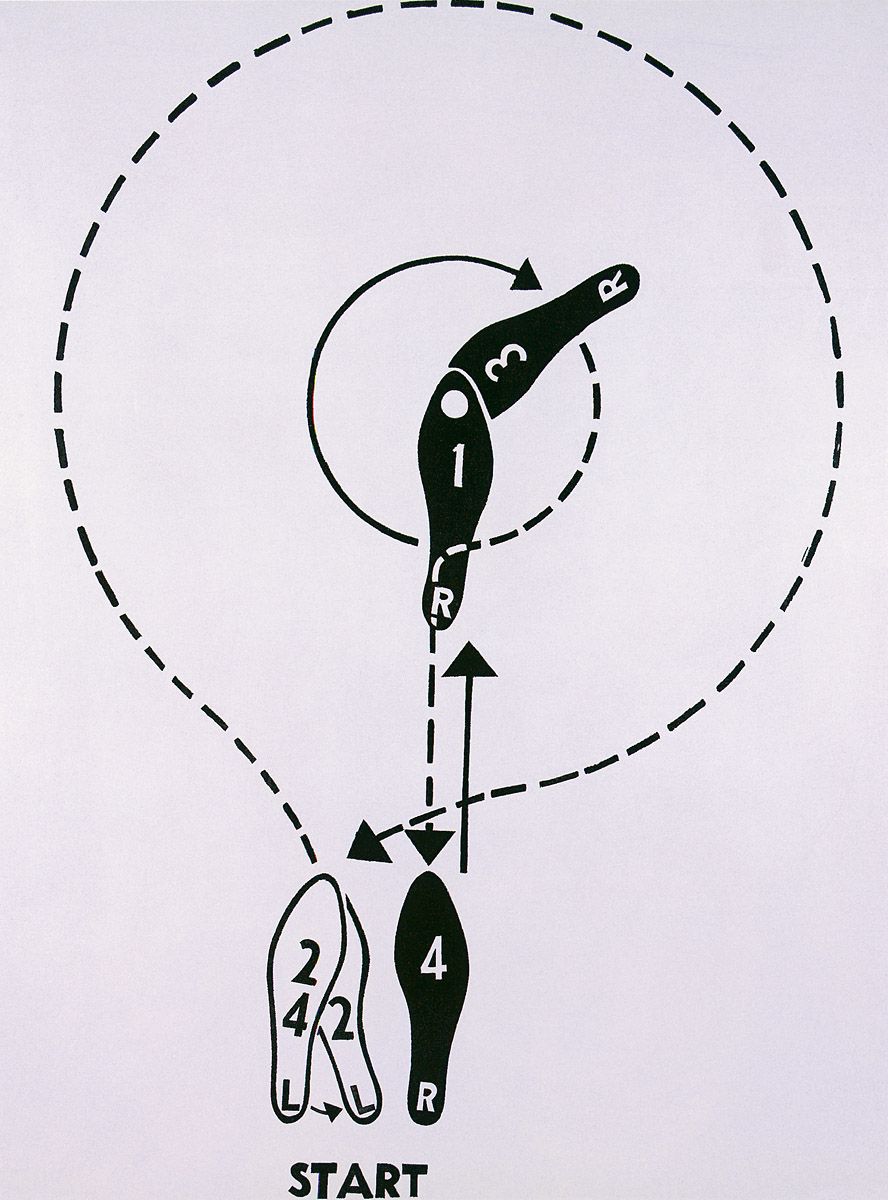

A particularly witty exhibit was one of Warhol’s Dance Diagram pictures (see above). This was displayed under thick glass on the floor, with a label attached inviting members of the public to remove their shoes and follow the dance steps across the painting itself. Not only was such behaviour unusual in the normally hallowed precincts of an art gallery, but the invitation was highly appropriate in a space owned by Sidney Janis, for the dealer was an enthusiastic dancer. With the exception of Willem de Kooning, all the Abstract Expressionists who had shown with Janis until then were so horrified by the dealer’s broadened taste that they fled to other galleries. De Kooning’s open-mindedness was unsurprising, for during the late-1940s he had happily incorporated into some of his paintings newspaper images that had been accidentally transferred there. Moreover, in 1950 he had pasted a woman’s smiling mouth from a Camel cigarette advertisement into a study for one of his Woman series of paintings. But his attitude towards Pop/Mass-Culture Art was singular among his peers, and his openness clearly reflected the fact that he was always ambivalent in his commitment to abstraction anyway.

Andy Warhol, Dance Diagram (Fox Trot), 1962. Synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 182.8 x 137.1 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, Frankfurt am Main.

Some Individual Artists and their Creative Development

From this point onwards the history of Pop/Mass-Culture Art becomes too complex to recount chronologically; throughout the rest of the 1960s and ever since, all of the Pop/Mass-Culture Art painters and sculptors discussed above, as well as others we shall come to, held numerous one-person exhibitions and/or participated in group shows, and a listing of every one of those displays would become very tedious indeed. It will suffice to mention significant events within the larger cultural context of the developing Pop/Mass-Culture Art tradition. Perhaps at this point, therefore, we can usefully switch to discussion of the creative development of a number of the artists who have contributed to the growth of that sensibility.

Jasper Johns

Jasper Johns only dealt with mass-cultural imagery at the outset of his long career, in the years between 1954 and 1963. We have already discussed the Flags paintings which proved seminal to the development of Pop/Mass-Culture Art. By 1958, when that series was coming to an end, Johns also began producing sculptural representations of everyday household objects such as light-bulbs and flashlights. By casting them in bronze, he transformed the cultural status of those commonplace artefacts. In time Claes Oldenburg, Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, Tom Wesselmann and many others would similarly replicate the appearance of the most mundane of consumer items, and raise them to the level of art when doing so. Alternatively, others such as Ed Kienholz, Jeff Koons and Haim Steinbach would simply alter the context within which we view real artefacts, as Duchamp had done, or even combine emulated objects with real objects, as Kienholz would do as well.

In his Targets pictures of the late 1950s, Johns made a subtle statement about his own homosexual orientation and the concealment this forced on him. He achieved this by employing roundels to signify his sense of being a potential target in a homophobic society, while across the tops of the canvases he ranged boxes containing various parts of the human body in order to allude to the compartmentalisation sexual secrecy engendered. A related work, the 1960 Painting with Two Balls, hints more obliquely at the same problems. His Numbers and Alphabets series pictures of the late-1950s and early-1960s incorporate familiar symbols both to act as pegs upon which to hang a highly energetic gestural painting and to make statements about primary elements of communication. In painted bronze sculptures of 1960, such as Two Beer Cans, Johns also made neo-Dadaist points about art, art capitalism and mass-culture. A subsequent group of pictures representing the map of the United States certainly comments upon mass-culture, if only by dint of its stencilled lettering. But in the main, after 1963 Johns began slowly turning away from popular culture and the mass-media, moving instead towards an exploration of abstract forms.

Robert Rauschenberg

Unlike Johns, down the years Robert Rauschenberg has engaged ever more closely with the mass-culture he had first dealt with obliquely in the 1950s. He was always profoundly involved with the supreme art of movement, namely dance, and no less important to him was chance and the accidental, an outlook reinforced by his close friendship with that master of musical radicalism and the aleatory, the composer John Cage. As a measure of Rauschenberg’s belief in chance operating as a guiding light for creativity, he would frequently incorporate into his works objects he had found quite by accident in Manhattan, even on occasion specifically setting out to walk around his city block picking up discarded objects and placing them on his canvases in the very same order he had originally encountered them. Such a process reflects life accurately, for invariably our lives are ruled by chance.

In 1959 Rauschenberg completed his sculpture, Monogram, in which the encirclement of a stuffed angora goat with a car tyre clearly suggests the way nature is increasingly being confined by man. Between the end of the 1950s and 1962 Rauschenberg continued to make complex Combine paintings, linking real objects with forceful paintwork to express the dynamism and changeability of existence in lower Manhattan, where he continued to live. In 1962 Rauschenberg found a technical way of harnessing reality even more directly. In July of that year Andy Warhol’s studio assistant had suggested that if his boss wished to avoid the laboriousness of painting repetitive images, he should use the photo-silkscreen printing technique instead. This process permits the transfer of photographic images onto a screen of sensitised silk stretched on a frame. The fine mesh of the silk allows ink or paint to pass through it onto a canvas or other support only where it is not prevented from doing so by a membrane of resistant gum. Soon after Warhol had taken up photo-silkscreen, Rauschenberg adopted the same process, not to utilise repetitious imagery but because he liked the freedom it allowed.

This technical breakthrough spurred Rauschenberg to an enormous productivity over the following years, during which he created many of his most memorable works. In canvases such as Kite and Estate of 1963, and Retroactive I of 1964, he purposefully used the reality projected by photographs, the dynamics of energy and tension released by emphatic brushwork, and the loose juxtaposition of images to create subtle meanings and embody the perceptual bombardment we all now experience. Such pictures appear increasingly relevant, not least of all because the grainy blurring of their photo-silkscreened areas induce all manner of associations with mass-produced imagery.

Dance is necessarily an exploration of space, and quite clearly Rauschenberg’s involvement with that art-form has generated the freewheeling spatiality apparent throughout his work. Yet this has not only resulted in pictorial enhancement; since the 1980s an involvement with real space has been evident in his work, for the artist has become utterly entranced by the excitement and beauty of the Space Age. The results have been works that have at their heart the technological complexities of rocketry, the implied movement of those giant machines and the human dimensions of space exploration. More recently still he has refined his art even further, moving away from his earlier gestural freedom to a far more controlled picture-making that is somewhat sculptural in form.

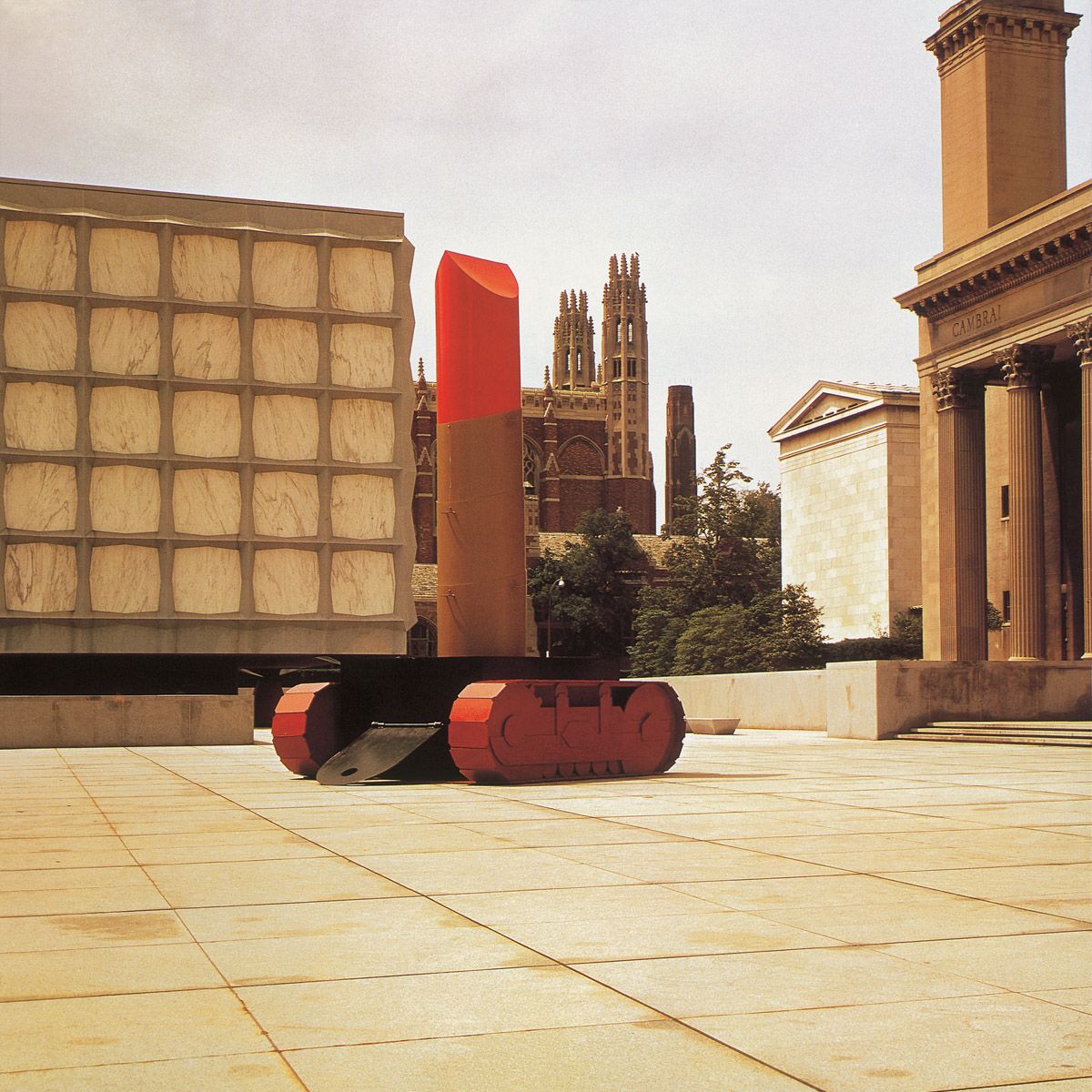

Claes Oldenburg, Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpiller Tracks, 1969-74. Cor-Ten steel, steel, aluminium, cast resin, painted with polyurethane enamel, 7.2 x 7.6 x 3.3 metres. Samuel F.B. Morse College, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

Jasper Johns, Three Flags, 1958. Encaustic on canvas, 76.5 x 116 x 12.7 cm, fiftieth anniversary gift of the Gilman Foundation, Inc., The Lauder Foundation, A. Alfred Taubman, an anonymous donor. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Art © 2006 Jasper Johns/ Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Robert Rauschenberg, Bed, 1955. Combine painting: oil and pencil on pillow, quilt, and sheet on wood supports, 191.1 x 80 x 20.3 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Leo Castelli in honor of Alfred H. Barr, Jr. Art © 2006 Robert Rauschenberg/ Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Claes Oldenburg, Floor Burger, 1962. Canvas filled with foam rubber and cardboard boxes, painted with latex and Liquitex, 132.1 x 213.4 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario, Canada.

Claes Oldenburg

Spatiality has always come naturally to Claes Oldenburg. He first moved towards Pop/Mass-Culture Art after experimenting in the late-1950s with Happenings and other live artistic events that already foreshadowed Performance Art. Usually such staged episodes were anarchic, neo-Dadaist affairs, attacks upon art and its conventions that echoed the uncertainty of the times in which they were created. Oldenburg’s first environmental work, The Street, was created in New York in 1960 and comprised an intentionally ragged, debris-strewn arena whose chaos was intended to parallel the confusion of the city in which it appeared. We have already touched upon Oldenburg’s two versions of The Store dating from 1961-2. As we have seen, with the second of these he discovered an important constituent of his metier, namely the enormous enlargement of everyday objects of mass-consumption whose size we invariably take for granted. Such enhancement not only cuts across normality but equally it comments upon the materialism of an age that assuredly puts a premium upon size and economic growth. (Unfortunately truth is always stranger than fiction; a sculpture of a hamburger more than two metres wide that Oldenburg created in 1962, is now almost in danger of being eclipsed in size by a new generation of real, fast-food chain ‘Monster Thickburgers’ exploding with calories and vast suppurations of fat.)

Oldenburg also found another, related way of interfering with our sense of the real: as well as using hard materials such as plaster and wire to imitate the appearance of fairly soft matter such as bread, meat and ice cream, he reversed the process and turned soft materials into very hard things indeed. A good example is his Soft Toilet of 1966. Down the years Oldenburg has created many other memorable and amusing pieces. One is the mock vehicle bearing a rising and falling lipstick which was destined for the Yale University campus in 1969 but which proved to be a little too challenging for the academic elders; first they had it removed and then they consigned it to a nearby museum. No less witty is the vast clothes-pin Oldenburg created for a public plaza in Philadelphia in 1976. Sadly or otherwise, many of Oldenburg’s projects have never come to fruition, such as his 1966 notion of replacing Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square, London, with an equally high automotive gear stick, which would have proven a most apt symbol for a public space and a country soon to be overrun by cars. No less whimsical was his 1978-81 plan to create a bridge in Rotterdam, Holland, in the form of two huge screws bent to the shapes of arches; only from the 1980s onwards would ‘post-Modernist’ architects take such imaginative conceits seriously. Since 1976, in association with his wife and artistic collaborator, Coosje van Bruggen, Oldenburg has continued to produce large numbers of sculptures that vary the size and density of everyday objects around us. Many of these, such as a 1988 bridge in the form of a spoon and cherry resting on a small island in a pond at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, enjoy a beauty of line and colour that removes them far from the triviality of the everyday consumer objects and foodstuffs that inspired them.

Two of the most inevitably trivial everyday objects within modern mass-culture are the children’s comic and the adolescent romance magazine. Given the nature of modern society it is perhaps sad but inevitable that boys should find intellectual sustenance and imaginative empowerment in sequences of images recounting easily-assimilated tales of cowboys, soldiers, spacemen and the like, while the adjustment from childhood to the initial stages of womanhood readily compels many girls to resort to romanticised visual fiction, feminist protests notwithstanding. From the perspective of adulthood the imagery of the boys’ comic usually seems mock-heroic and banal, while that of the girls’ romance magazine appears hopelessly sentimental, gauche and banal. But comics and romance magazines are enormously popular, and thus industrialised. It was therefore unsurprising that artists would eventually turn their attention to such means of mass-communication.

Roy Lichtenstein

Roy Lichtenstein was certainly not the first of them to do so but he was the first to realise that in order to enhance his statements about the way both comics and teenage romance magazines embody mass-culture, he needed to emulate the very processes by which they are printed. Most especially this concerned the method by which halftones – that is, the intermediate, light-to-dark shades of the various colours used – are arrived at in mass-printing. To such an end Lichtenstein began to emulate the Benday dot, a process of halftone printing first developed in New York in 1875 by the printer Benjamin Day. By the 1960s such a process was already being overtaken by automated photolitho techniques but this didn’t worry Lichtenstein, for his emulation of the method turned his paintings from simply being magnified copies of comic-strip images into comments about the nature of mechanical reproduction.

Like many other artists who contributed towards the Pop/Mass-Culture Art sensibility – Warhol and Hockney also immediately come to mind – Lichtenstein had first worked through Abstract Expressionism in an undistinguished and unsatisfied way. His epiphany occurred in June 1961 when he painted Look Mickey, a picture he developed from a Mickey Mouse cartoon. Not long afterwards he realised the potential for employing the imagery of war comics to comment obliquely upon contemporary political and military developments. This was extremely apposite, for the 1960s saw continuing American involvement in the Cold War and deepening entanglement in Vietnam. In works such as Blam of 1962 and Torpedo…Los! of 1963, Lichtenstein may have developed material that clearly dealt respectively with the Korean War and the Second World War but its relevance to contemporary America was surely obvious to all but the most obtuse.

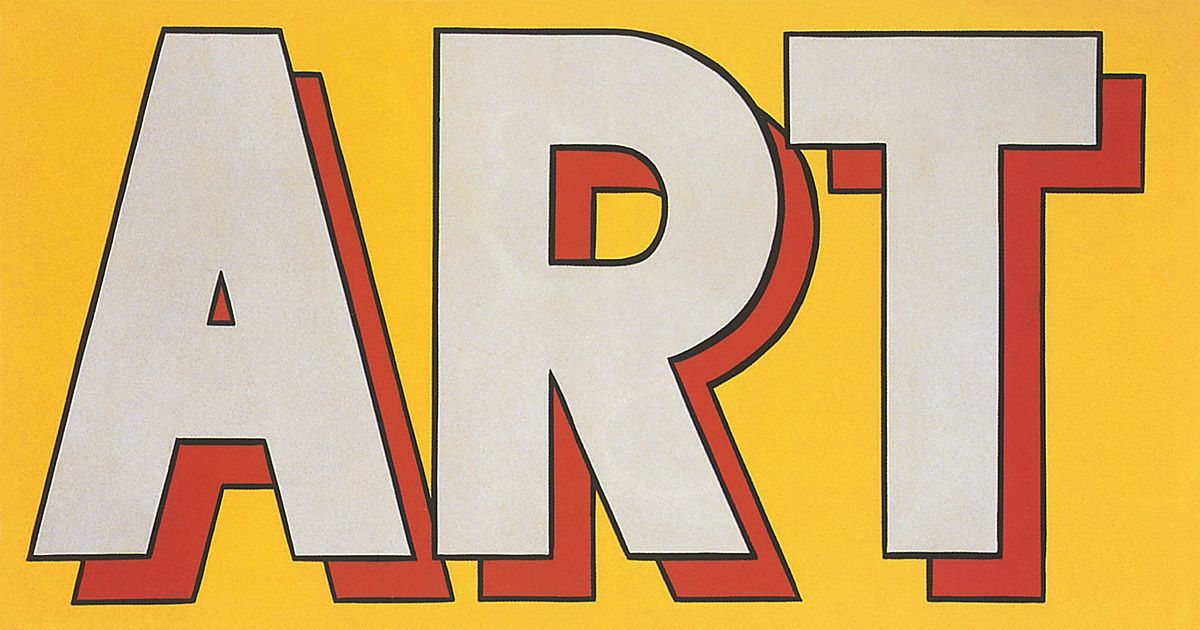

Roy Lichtenstein, ART, 1962. Oil on canvas, 91 x 173 cm. Gordon Locksley and George T. Shea collection, USA.

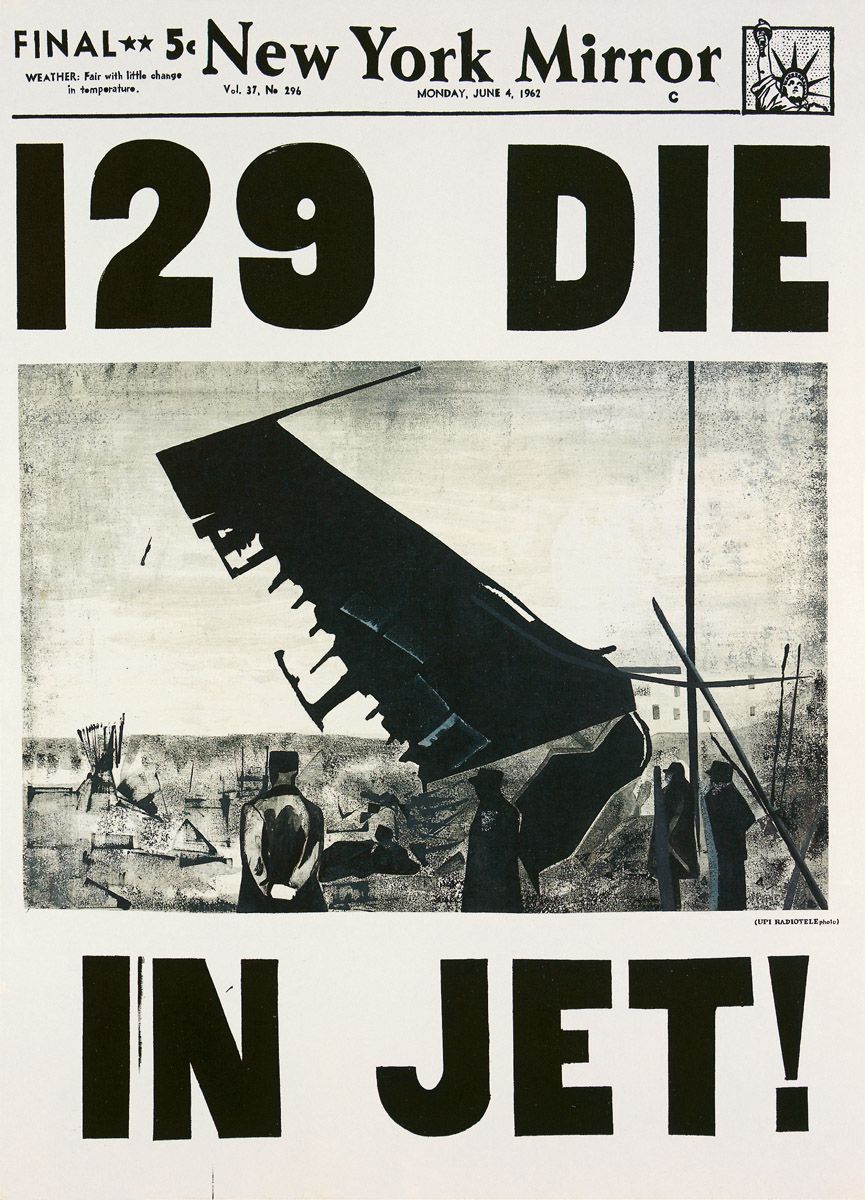

Andy Warhol, 129 Die in Jet (Plane Crash), 1962. Acrylic paint on canvas, 254 x 183 cm. Museum Ludwig, Cologne.

The use of material drawn from teenage romance magazines, in paintings such as Hopeless of 1963 and We Rose Up Slowly of 1964, permitted Lichtenstein to comment sardonically upon immature perspectives regarding human relationships. Naturally, by enlarging the original images greatly, the painter necessarily amplifies the banality of the original material and thereby accentuates something of the falsity – of taste, imagery and even economic value – that lies at the very heart of the increasingly inauthentic global mass-culture that continues to expand and surround us. Moreover, the magnification of kitsch or laughable bad taste serves just as usefully as a distancing process, allowing both artist and viewer to look down upon the original imagery with cultural condescension, as though to say ‘such banality is only for lesser mortals – I’m not taken in by it’. We shall encounter exactly the same distancing process in the work of other Pop/Mass-Culture Art figures, most notably Andy Warhol and Jeff Koons.

From the start Lichtenstein also directed his shafts at ‘Art’. In Mr Bellamy, which he created in his breakthrough year of 1961, he wittily created an art world in-joke, while in the following year, with Masterpiece, he satirised the perpetual New York clamour for the fame that he was certainly seeking for himself. In 1962 too, Lichtenstein made the first of a set of images dealing with the single word ART. By the mid-1960s he began to apply his mechanical reproduction emulation technique to images by Monet, Cézanne, Picasso, Mondrian, Léger and a great many other masters. He did not do much (if anything) for the originals but he certainly made the point that a large amount of art is today disseminated through mechanical reproduction, although this hardly constitutes a profound insight. Yet in one series of works dealing with artistic matters he did crack an excellent visual joke. This was his set of gigantic emulations of what in reality would have been fairly small Abstract Expressionist brushstrokes; the witticism emerges from the disparity of size between what we know of the originals and what the imitations project, as well as the difference between the original, emotionally-charged brushstrokes and Lichtenstein’s utterly unemotional transformation of them.

Because Lichtenstein could not go on churning out comic-strip and reworked-art images forever, he was forced to expand his repertoire of subjects. As a result, he accorded the same Benday dot treatment to landscapes, interiors, architectural details, banal advertising images, household objects and a mass of other artefacts. He also juxtaposed images from a variety of sources, creating montages analogous to Cubist collages. Certainly his paintings and sculptures can look extremely seductive, and assuredly he never ran out of things to say, but eventually his output all became somewhat wearisome, for although the Benday dots assume a life of their own by contributing an abstractive air to the proceedings, they no longer seem pertinent when divorced from their comic-strip surroundings. (Moreover, in an age of electronically-created halftones they became totally irrelevant technologically). Like many creative figures before and since, Lichtenstein eventually ran his art into the quicksand of a particular style, ending up simply as a mannerist.

Andy Warhol

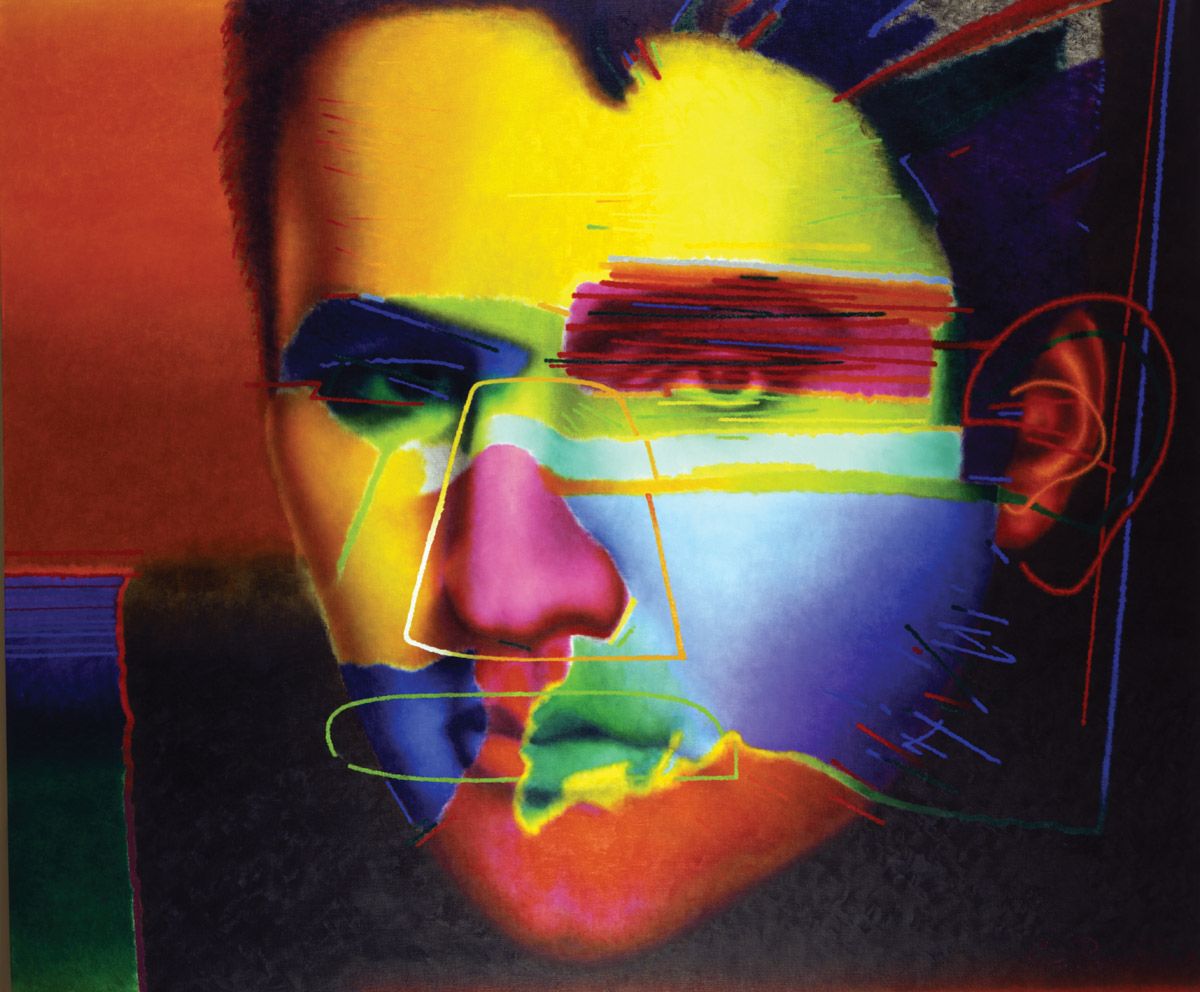

The same charge could justifiably be levelled at a good deal of the later work of Andy Warhol, for although he never restricted himself to a single style, he did eventually go through patches of having nothing to say, and consequently ended up producing wave after wave of images that are all style and no substance. Warhol was a top New York advertising illustrator in the 1950s, grossing hundreds of thousands of dollars annually and winning industry awards for his work. But after seeing the Johns and Rauschenberg shows in 1958 he became desperate to forge a new career for himself as a fine artist. In 1960 he took up painting seriously, understandably toying with Abstract Expressionism but to no avail; by then the style was passé. He also tried neo-Dadaism in the Rauschenberg manner, which got him nowhere fast. Then he painted Coke bottles and similar artefacts drawn from mass-culture but did so in a sloppy expressive manner that didn’t hit the visual spot either. Around the same time he explored comic-strip images, until he found out that Roy Lichtenstein had beaten him to the draw on that one too. So where could he go next, he asked himself with increasing desperation?

The answer came one evening in December 1961. An interior decorator friend claimed to know exactly what he should be painting and demanded fifty dollars for the idea. Warhol quickly paid up and was told he should be painting his two favourite things in the world: money and the canned soup he ate for lunch daily. He loved these suggestions and the very next day was seen in his local supermarket buying all forty varieties of Campbell’s Soup. He immediately set to work, and over the next six months or so produced a group of forty small, laboriously painted oils, each of which inexpressively portrayed a can containing a separate flavour of soup. While slaving over these works he kept his radio, television and record-player simultaneously going at full blast, just to purge his mind of all subjectivity; he wanted to be an automaton, and his paintings to look as utterly impersonal as possible. This was because, with an insight only given to genius, he had recognised three fundamental truths of mass-culture: that we live in a supreme age of impersonally-crafted, mass-produced objects; that those objects are usually only affordable because they are created in enormous quantities; and that repetitiousness and replication – of labour, production and marketing – are what makes and eventually sells them. All of this he wanted to parallel exactly in his art.

The first Campbell’s Soup Cans and Dollar Bills paintings were followed by pictures of teach-yourself-to-dance diagrams, paint-by-numbers images, and serried ranks of Coca-Cola bottles, S & H Green Stamps, airmail stamps and stickers, and ‘Glass – Handle with Care’ labels. Many of these were produced using hand-cut stencils or rubber stamps and woodblocks, devices Warhol had employed as an illustrator. But the gap between hand-made and machine-made images was truly closed in July 1962 when, as we have seen, Warhol’s attention was drawn to the photographic-silkscreen technique as an efficient, non-laborious means of making large numbers of repeated images. Soon these included pictures of baseball, pop music and movie stars, as well as of the Mona Lisa, many of which were represented as repetitiously as possible; this repetitiveness paralleled the way that images of such persona and icons of art are constantly being repeated by the mass-media. By the time he created these images Warhol had also begun to move in a different direction as well, for early that June an art-curator friend had told him to stop affirming life and instead portray the death that pervaded America. As a consequence, Warhol produced a picture of a newspaper front page which bore the headline ‘129 DIE IN JET!’. He followed it with a long sequence of Disaster pictures. Among other sources, these drew upon photos of car crash victims taken from police and newspaper files; an image of the electric chair whose use was a matter of heated debate in New York State at the time; and a photo of a newspaper report of botulism fatalities. He also produced a series of pictures of people committing suicide. In many of the Disaster pictures Warhol coupled each canvas with an identically-sized support painted all over with the same basic colour as its companion (see an example). He claimed to have done so in order to give his purchasers twice as much painting for their money, but that was a diversion; clearly his true intention was to complement each positive image with an utterly negative one. In the context of the tragic events depicted, the blank canvas can only signify the total void created by death.

After 6 August 1962, one of the suicides Warhol portrayed was Marilyn Monroe, who had killed herself the previous day. For her image Warhol arrived at yet another inventive way of dealing with things: he reproduced a photo of the dead star over areas of flat colour that suggest perfect skin, perfect hair, perfect eyeliner, perfect flesh and perfect lip colourings, thereby making Marilyn look as artificial and banal as possible. In one of the Marilyns Warhol even set the film star down on a field of gold, thus reminding us that the lady was at the cutting edge of a vast industrial apparatus for transforming her manifold attractions into gold. Arguably an even more inventive contribution to the Marilyns series is the Marilyn Diptych of 1962 in which Warhol contrasted the actress’s ‘perfect’ and colourful public persona with her messy, disintegrating, uncolourful and gradually fading private self. Any notion that Warhol was never a serious artist is completely confounded by this one picture alone.

Further Disaster images followed, notably race riot pictures and, following John F. Kennedy’s death on 22 November 1963, the ‘Jackie’ series which drew upon newspaper photos taken after the assassination. In 1964 Warhol turned his attention to art capitalism and to sculpture in equal measures. He had carpenters make 400 wooden boxes which he and his assistants then silk-screened so as to replicate the outer cardboard packing cases of Campbell’s Soup cans, Brillo Pads, Del Monte Peach Halves and similar consumer products which might be found in a supermarket stockroom. Subsequently, he exhibited these sculptures, filling the Stable Gallery in New York from floor to ceiling with the objects and thereby making the space look just like such a stockroom. This was his entire point, for commercial art galleries are never much more than that.

Protest and notoriety followed Warhol’s creation of a gigantic mural showing thirteen of the FBI’s Most Wanted Men on the New York State Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair in April 1964; faced with demands for its removal because most of the suspects were Italian-Americans, Warhol simply obliterated the image with aluminium paint, a neo-Dadaist gesture that was surely appreciated by his friends Marcel Duchamp and Robert Rauschenberg, among others. Later that summer Warhol turned away from destruction and criminality by creating flower pictures from photos of real flowers. By giving them exactly the same flat and separated colour treatment he had accorded to Marilyn Monroe, he made the flowers look extremely banal and artificial, thus driving a wedge between nature and art.

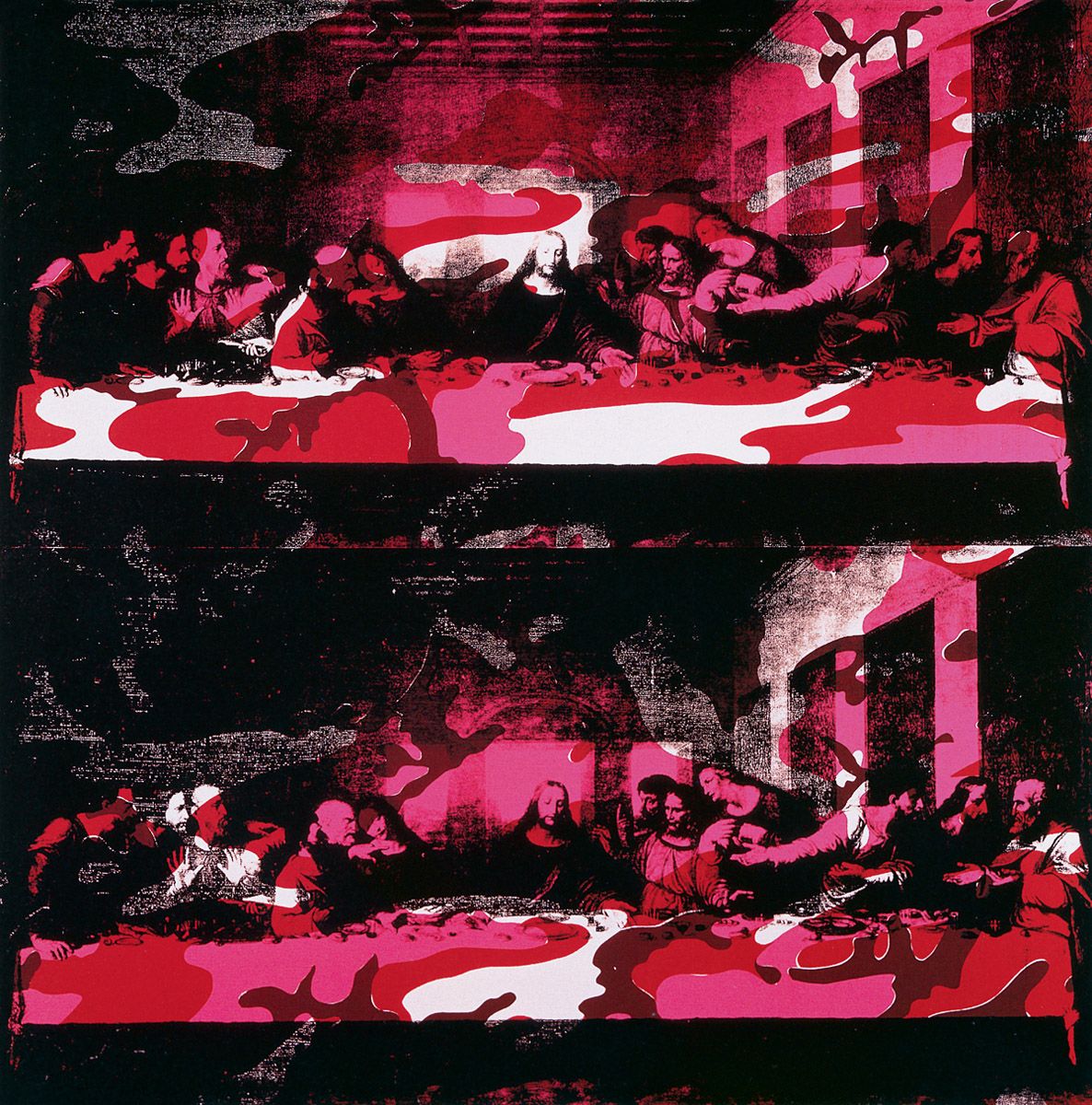

Andy Warhol, The Last Supper, 1986. Synthetic polymer paint and silkscreen, 198.1 x 777.2 cm. The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh.

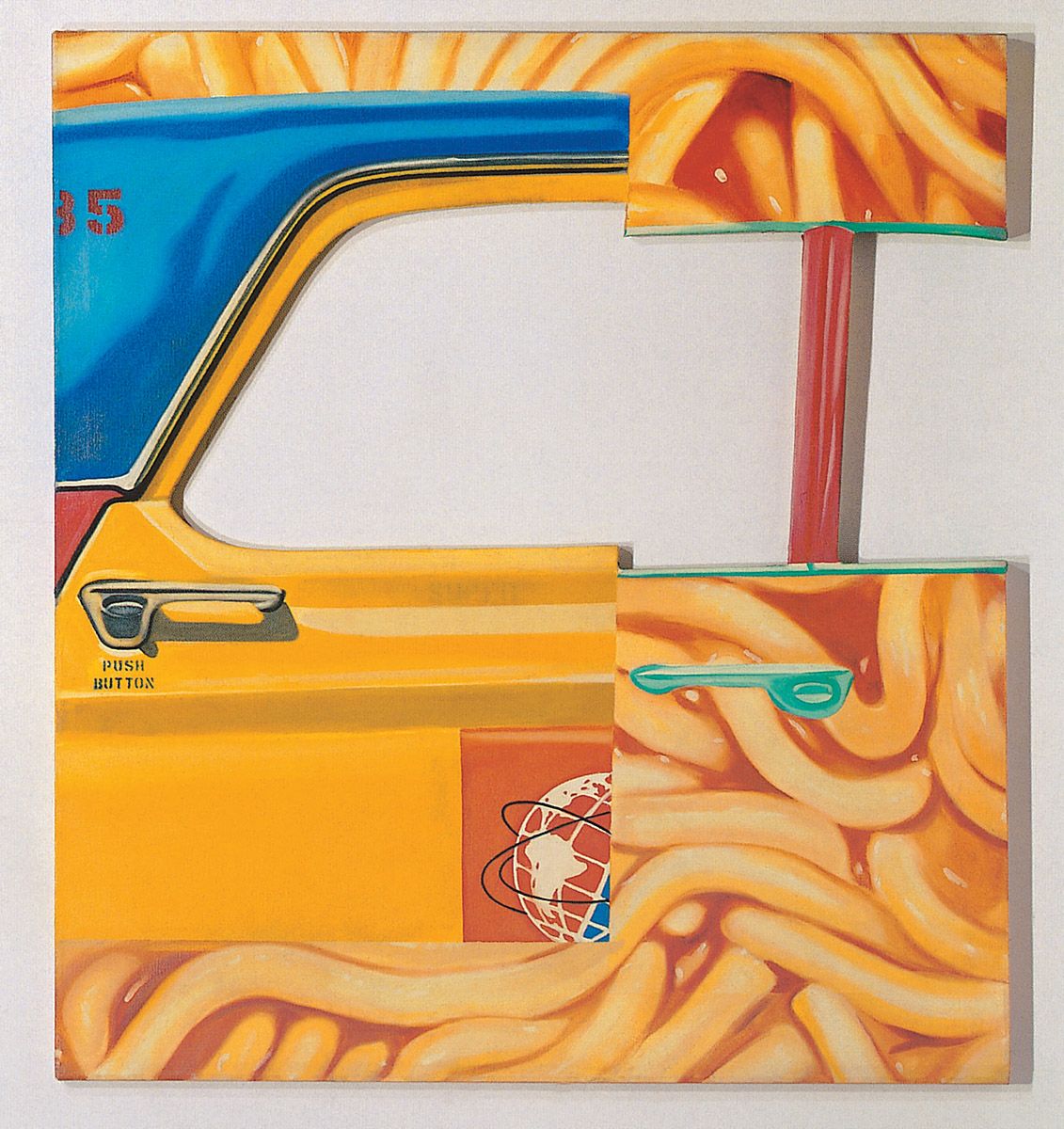

James Rosenquist, The Friction Disappears, 1965. Oil on canvas, 122 x 112 cm. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C., gift of Container Corporation of America. Art © 2006 James Rosenquist/ Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

In April 1966 Warhol brought this burst of painterly creativity to an end with a show of Cow Wallpaper and floating helium balloons. The wallpaper was intended to summarise the pastoral tradition in western art; the balloons were very much part of the ‘Flower Power’ consciousness of the day. By now Warhol was utterly disenchanted with creating pictures and so he turned away from doing so for some time. Instead, he ran the Velvet Underground rock group and made films, none of which relate to the Pop/Mass-Culture Art sensibility. Not until 1971-72 would he return to form in the visual arts by creating 2000 images of the Chinese leader Chairman Mao Zedong, many of them in the form of a wallpaper; this lining would serve as the backdrop to an exhibition Warhol would mount of the Chairman Mao paintings and prints in 1974. The series constitutes a masterly piece of irony, for the communist politician represented everything that capitalistic purchasers of art despised, an antipathy that didn’t prevent them from buying the pictures. Naturally, the Chairman Mao series also made highly relevant points about the worship of politicians and the proliferation of idolising images of them.

In 1972 Warhol began a new career by turning into a society portraitist. This should not entirely surprise us; coming as he did from working-class Pittsburgh, where he had been born on the wrong side of the tracks, he was always in thrall of glitz and glamour, celebrity and the cult of personality. But his new direction didn’t do his art much good, for over the following years he produced vast numbers of commissioned portraits, many of which have an entirely vacuous visual appeal; probe the images and there is absolutely nothing behind them, which is certainly not the case with portraits by, say, Titian, Rembrandt or Degas. But in one way Warhol was again holding up an accurate mirror to society, for in most cases the people he painted were as superficial as their portraits. Once again he effected a complete congruence between subject and object.

More irony followed in 1976, the year in which Warhol made his last film. The Hammer and Sickle images follow in the footsteps of the Chairman Mao paintings and prints by presenting capitalist art buyers with symbols of communist revolution, which is just what they truly abhorred. Yet in a subsequent sequence of works, namely the Skulls series of paintings and prints also dating from 1976, Warhol did again become a serious artist, at least for a while. This is perhaps unsurprising, for in 1968 he had been shot by one of his followers, an attack that undoubtedly brought home to him his own mortality. The Skulls are not great paintings but they do enjoy a certain poetic resonance, and they undeniably add something to the long tradition of momento mori images in western art.

Over the rest of his career until his untimely death in 1987, Warhol’s work was highly variable in quality. He made large numbers of very bland portraits whose generic subjects range from athletes to American Indians. Predictably the gay-orientated Warhol gave us representations of sexual organs. Likenesses of the Queens of England, Denmark, Holland and Swaziland must rate among the blandest royal portraits ever created. Art continued to be a source of subject-matter, as in sequences of works dedicated to exploring imagery by Munch, de Chirico, Leonardo da Vinci and various lesser Renaissance painters. Warhol’s affinity with the anti-art neo-Dadaism of Rauschenberg and Johns in the 1950s resurfaced in 1977 when he created a highly smelly Oxidation series of canvases by getting his pals to urinate on to wet copper paint, thereby causing the chemical reaction of the titles. In a sequence of wholly abstract paintings, the Shadows series exhibited in 1979, Warhol’s lifelong tendency to bring out the purely formal qualities of the images he used came wholly to the fore, although to no artistic effect whatsoever. Between 1979 and 1986 he returned to the subjects of Marilyn Monroe and Campbell’s Soup cans, although now he treated them in the manner of photographic negatives, thereby creating a parallel with the negativity of the world around us. In highly inventive, photo-negative-like portraits of his admirer, the German artist Joseph Beuys (whose work he did not esteem in return), Warhol covered each canvas with diamond dust, thereby making a witty and valid point about art world glitz and glamour. A new set of dollar sign images again allowed him to portray the money he loved so much, while in the opposite vein he transformed yet another arch-enemy of capitalism, Vladimir Ilych Lenin, into a glamorous figure whom he set before the haute-bourgeoisie for their delectation and their money. Perhaps most tellingly Warhol created a series of pictures of handguns in 1981. These are not any old guns, however; they are .22 snub-nosed revolvers, one of the two types of weapon his assailant had carried in 1968.

Just before his death resulting from poor medical attention following a minor operation in 1987, Warhol made a couple of series of religious images. In one he dealt with the repetitiousness of kitsch sculptural reproductions of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, while in the other he transformed a Raphael Madonna and Child into a tawdry advertisement; both series therefore make valid (if rather slight) points about the bogusness, commercialism and cheapening of religious imagery in the modern world. After Warhol’s death it emerged that he had been a dedicated if secretive Roman Catholic, so quite evidently he did hold genuine views about the debasement of religious art in our time. His concealment of that authentic side to himself was entirely in keeping with the way he worked hard to appear mindless and robotic after 1963, for he was anything but brainless and mechanical. That he was aware he masked his true self is proven by another late series of works, his Camouflage Self-Portraits, for camouflage serves no other purpose than to cloak what is real.

Of all the artists who have contributed to the Pop/Mass-Culture Art tradition, it seems valid to claim that Warhol was one of the most thematically varied, visually inventive and humanly insightful, which is why he has been accorded so much space here. In the five or so years between 1962 and 1966, and on occasions thereafter, he created works that still have an enormous amount to say about the modern world. Admittedly he was a largely associative artist, setting off chains of mental links by means of his images, rather than producing images that possess much pictorial resonance (as is the case with, say, those many Old Master painters whose exploration of both the visual and the associative can seem inexhaustible). But if he was a largely associative artist he did possess the rare ability to project huge implications through the mental connections he set in motion (as with the parallels he drew between pictorial repetitiousness and industrial repetitiousness). By such means he threw a great deal of direct or indirect light upon modern nihilism, materialism and conspicuous consumption, world-weariness or anomie, political manipulation, economic exploitation, media hero-worship, and the creation of artificially-induced needs and aspirations. He also carried forward the assaults on art and bourgeois values that the Dadaists had earlier pioneered, so that by manipulating images and the public persona of the artist he was able to throw back in our faces the contradictions and superficialities of contemporary art and culture. Ultimately it is the trenchancy of his cultural critique, as well as the vivacity with which he imbued it, that will surely lend his works their continuing relevance long after the objects he represented have become technologically outmoded, and the famous people he depicted have come to be regarded merely as the faded superstars of a bygone era.

James Rosenquist

If Andy Warhol’s art generates associations, so too does that of James Rosenquist, albeit in a far less explicit and much more visually fractured way. Rosenquist spent about seven years of his early working life as a billboard painter, both in the mid-western United States, from where he hails, and in New York, to which city he moved in 1955. In 1960 he terminated that activity in order to concentrate on his art. He had continued to work in the wholly abstract manner he had been pursuing for about three years, but then he finally brought his imagery into creative focus at the end of 1960.

Like Warhol, Rosenquist had also been enormously impressed by the Jasper Johns show in 1958, as well as by works by the same artist viewed later. What particularly attracted him was the degree of abstractiveness Johns had elicited from images of real things, such as flags and other signs such as numbers and the letters of the alphabet. After tentatively exploring this influence, Rosenquist finally decided, “…to make pictures of fragments, images that would spill off the canvas instead of recede into it… I thought each fragment would be identified at a different rate of speed, and that I would paint them as realistically as possible.” The results were canvases such as President Elect of 1960-61. Here the face of US President John F. Kennedy is juxtaposed with a slice of chocolate cake being pulled apart by some perfectly manicured female hands, alongside the shiny body and wheel of a car. Essentially the work marks a return to Picasso’s assembled Cubist images of exactly half a century earlier, except that instead of pasting down bits of visual flotsam and jetsam on small-to-medium sized pieces of paper or canvas as the great Spanish artist had done, Rosenquist hugely scaled up fragments of imagery taken from magazine photos and the like, painting them impersonally and with enormous verisimilitude. The constituent images are strongly bound to each other with intersecting lines and interpenetrating masses, and they help construct an overall meaning, relating the President to the society he governed by means of some of its artefacts and glossy images.

Rosenquist went on mining this pictorial vein thereafter. As he commented, “I’m interested in contemporary vision – the flicker of chrome, reflections, rapid associations, quick flashes of light. Bing – bang! I don’t do anecdotes. I accumulate experiences.” Thus Painting for the American Negro of 1962-3 uses all kinds of images taken from the mass-media to project generalised points about ethnicity, sexuality and consumerism. Again an allusive overall meaning emerges from the constituent images, although the lack of any direct relationship between the people and objects represented says much about the fracturing of communication, identity and self-confidence that was very much the lot of American blacks when the picture was painted.

The use of visual connection and fragmentation can equally be encountered in what is arguably Rosenquist’s masterpiece, the gigantic F-111 of 1965. Totalling more than 26 metres in length and running around four walls, the composition is underpinned by the shape of what was then the very latest American fighter-bomber, the F-111 of the title. In overall terms the work makes a running statement about the visual overload of the contemporary world, its rampant, glossy materialism and, not least of all, its militarism (for when the picture was painted, things were really hotting up in Vietnam). The work also incorporates a number of inventive visual metaphors, as will be seen in the commentary on the colour plate below.

The same sense of scale, an even more sophisticated sense of abstractive form and some wonderful colours are all present in Rosenquist’s next major work, his Horse Blinders of 1968-9 (1, 2, 3, 4) which is largely about the way we perceive things. Although Rosenquist’s art went into decline following a horrendous road crash in 1971, it slowly regained in strength. This is made abundantly clear by superb paintings such as Star Thief of 1980, which acts as a metaphor for the earth in space; and by 4 New Clear Women of 1983, which addresses the fragmentation of women in modern society. If nothing else Rosenquist has developed the power to create beauty out of all the disparate visual phenomena that surround us, and to do so with the most impressive dash. It is a rare achievement.

Jim Dine, Car Crash, 1959-1960. Oil and mixed media on burlap, 152.4 x 162.6 cm. Private collection.

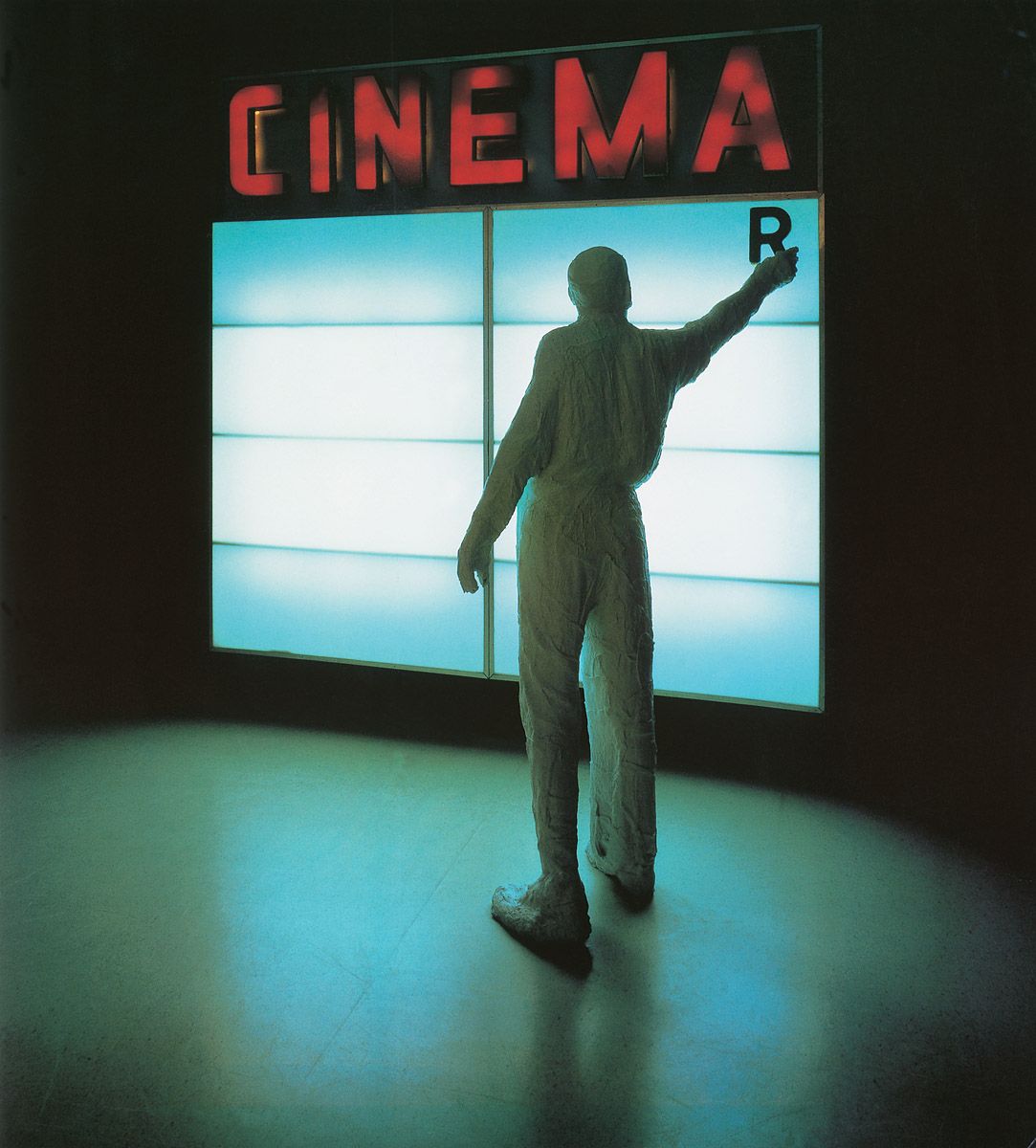

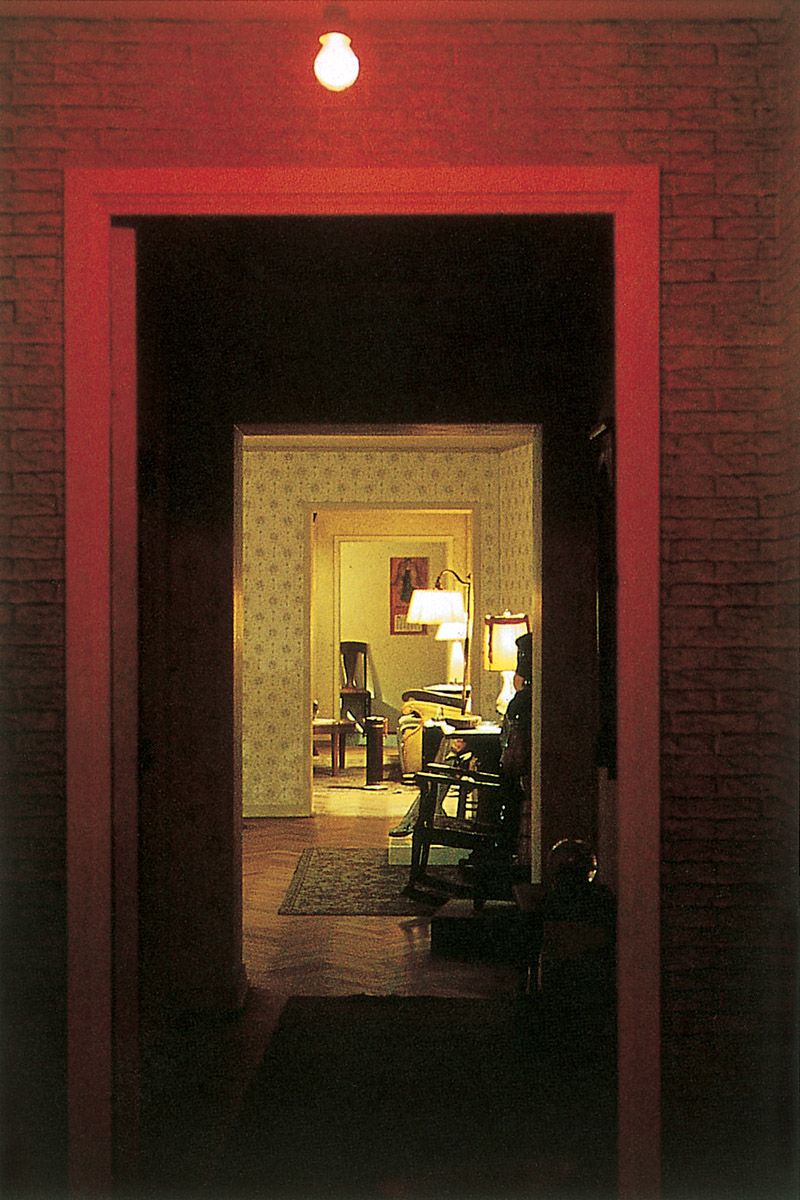

George Segal, Cinema, 1963. Plaster, metal, plexiglass and fluorescent light. 299.7 x 243.3 x 99 cm. Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, gift of Seymour H. Knox, 1964. Art © 2006 The George and Helen Segal Foundation/ Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Ed Kienholz, Roxy’s, 1961-1962 (detail). Paint and resin on mannequin parts, furniture, lamps, bric-a-brac, boar skull, papier maché jack-o-lantern, jukebox, string puppets, garbage can, potato sack, sewing machine stand, treadmill, towel, paintings, live goldfish in bowel, disinfectant, perfume, clothing, rugs, wood, wainscoting and wallpaper, variable dimensions. Reinhard Onnasch collection.

Jim Dine

Jim Dine has always been termed a ‘Pop’ artist simply because he became prominent around 1960 and participated in the 1962 ‘New Realists’ exhibition, in which he displayed a ceramic wash-basin attached to a canvas, a panel of bathroom fixtures, a painting with a lawnmower attached, and a canvas supporting five feet of coloured hand tools. Yet Dine very speedily disassociated himself from ‘Pop Art’, and he was quite right to do so, for rather than address any aspects of popular mass-culture, he merely made use of many of its familiar objects to express aspects of his inner life. As time has gone on that self-exploratory trend has continued, with his recent output bearing no links to mass-culture whatsoever.

George Segal

An artist whose output has continued to enjoy such a connection, however, is George Segal. He began his career as a painter who occasionally tried his hand at sculpture, but the turning point in his development was reached in 1961 when a technical breakthrough enabled him to achieve a very direct degree of sculptural realism. On the back of this he went on to fashion an art dealing with the anonymity of modern life, the complex and often inexpressible relations between men and women, the disconnection of the individual from the crowd, our links with the media and technology, and much else besides (Cinema, 1963; The Dry-Cleaning Store, 1964; The Diner, 1965; The Subway, 1968). We are on familiar American territory here, of course, for anonymity, insularity, loneliness and alienation are the characteristic themes of Edward Hopper’s work, and Segal has not only admitted his artistic indebtedness to that painter but done so in a way that reveals as much about himself as it does his creative forebear:

…for [Hopper] to use the real stuff of the world and somehow – not suddenly but painstakingly, painfully, slowly – figure out how to stack the elements into a heap that began talking very tellingly of his own deepest feelings, he had to make some kind of marriage between what he could see outside with his eyes, touch with his hands, and the feelings that were going on inside. Now, I think that’s as simply as I can say what I think art is about.