HOW NATURAL ARE OUR WOODS?

WHEN THE ICE RETREATED and the climate warmed, Britain and Ireland became covered with forest, along with the rest of northwest Europe, and we are used to regarding woodland as the natural state of the landscape. But natural woodland – the wildwood – was a very different thing from most of the woods we see around us now, which are at best ‘semi-natural’. The species of which they are made up are mostly native wildwood species, but the structure and detailed composition of the woods have been heavily influenced over the millennia by man. Truly natural woods of long standing are rare in our islands, and mostly in inaccessible places, such as sea-cliffs (Fig. 52), rocky slopes high on our hills, and islands in lakes in western Scotland and Ireland. Natural woods are untidy places compared with most of the woods we are accustomed to!

The earliest Neolithic farmers were interested only in cleared land to grow crops, and they cleared the forest to waste. As more land was cleared and prehistoric society became more sophisticated, Neolithic and Bronze Age people ‘domesticated’ areas of the wildwood, to provide useful products they needed, such as straight hazel rods for making hurdles and wattle-and-daub building, and longer and stouter poles for more substantial structural uses, and an accessible supply of firewood. The wood generally provided both ‘timber’ from the large trees, and ‘wood’ from the coppiced underwood. The underwood was at least as valuable in the traditional economy as the timber, often more so. Farm animals were kept out of woods. Some areas of woodland were used as wood-pasture, and these in general had no underwood. We should remember that the survival of these traditional woods depends on the fact that they were useful to our ancestors – they formed a part of the economic fabric of their societies.

FIG 52. (a) Sessile oak (Quercus petraea) woodland on exposed cliff slopes at the Dizzard, south of Bude on the north coast of Cornwall. (b) Interior of the wood: bracken, brambles and great wood-rush, with primroses and wood anemone in the foreground. April 1981.

TRADITIONAL WOODLAND MANAGEMENT

In traditional woodland, a proportion of trees (from seedlings or saplings on the floor of the wood) were allowed to grow to maturity to provide timber. The desired species (most usually oak) would be chosen, and the trees formed a more or less open canopy. Individual trees would be felled when needed. Because of their wide spacing, the crowns of these trees were wide and richly branched. The main use of timber was for house and farm building and other local needs. (Contrary to popular supposition, shipbuilding was a relatively minor and localised use, and the demand for merchant ships greatly outweighed that for the Navy.) The space between the trees was occupied by underwood.

FIG 53. Spring flowers in a hazel coppice near East Anstey on the Devon–Somerset border, May 1984. Primroses, moschatel (Adoxa moschatellina), lesser celandine (Ranunculus ficaria) and early-purple orchid (Orchis mascula).

The underwood – coppiced hazel, or sometimes ash, wych elm or small-leaved lime – was generally the principal crop of the wood. It was cut to the ground on average every five years, though longer intervals between coppicings were sometimes used to get larger poles. Hazel is the traditional material of hurdles, and the coppice also provided stakes and poles, and firewood. Large quantities of underwood were turned into charcoal for smelting and iron working.

The years immediately following coppicing produced spectacular displays of woodland flowers (Fig. 53), until the coppice shrubs grew up and the canopy closed before the next coppicing. Many coppices are now derelict, and decades have elapsed since they were last cut. The spring woodland flowers are still there, but much sparser.

In parts of the country where there was a thriving leather industry, mainly in the west of Britain, oak bark for tanning was in great demand. This led to large tracts of oakwood (largely sessile oak) being treated as underwood and coppiced at 20–30-year intervals (Figs 54, 55). The bark was stripped for the tanneries, and much of the wood was burnt for charcoal. Coppicing in most of these oakwoods ceased with the Second World War, and this coppice is now derelict. Some has been ‘singled’ (regrowth from the coppice stool reduced to the one best trunk), so converting it to ‘stored coppice’. Nevertheless, many of these woods and the valleys in which they lie are beautiful and species-rich, particularly in bryophytes and lichens (Chapter 7). No doubt any woody species other than oak were weeded out, but some birch and rowan are usually present. If the primary aim was to grow timber, the dominant trees might be managed as high forest, but woods that appear to be this often turn out to be singled coppice.

FIG 54. Sessile oak coppice, Stoke Woods, Exeter, May 1972; patchy field-layer of great wood-rush, with a scatter of the mosses Dicranum majus and Polytrichastrum formosum. The two trunks nearest the camera spring from the same stool, whose outline can be clearly made out. This coppice was singled a few years after the photograph was taken.

FIG 55. Oak coppice woodland (here pedunculate oak) clothing the slopes of the Dart valley upstream of Bench Tor, February 2000. Birch and common gorse on the well-drained heathy ground near the camera, foxy red-hued bracken on deeper soils of the slopes beyond.

In wood-pasture the mature trees are out of reach of grazing, but seedling or sapling trees get eaten, especially those of the more palatable species. If an ongoing crop is wanted from the trees, it can be got by pollarding the trees. The trunk is cut off somewhere between 2 and 4 m from the ground, and shoots from the top of the cut trunk in the same way as from a coppice stool, but out of reach of the livestock. Pollard willows (Fig. 56) used to be a familiar sight on riverbanks in southern England, and old pollard oaks and beeches are a common feature of former wood-pastures and old parkland.

FIG 56. Pollard willows near Oath, West Sedgemoor, Somerset, Sept. 2010. The ‘mop-head’ trees produced a crop of young shoots for basketry and other uses out of reach of grazing cattle.

Particularly from the eighteenth century onwards, landowners created plantations, often but by no means always of exotic trees such as sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus), sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa), Norway spruce (Picea abies) and European larch (Larix decidua). Native Scots pine was widely planted, especially in Scotland. These plantings were sometimes for timber, but often for other purposes. Sweet chestnut might be planted with a view to a crop of chestnuts, or for timber, or for coppicing to produce split-chestnut paling. Sycamore was often planted for shelter, and does surprisingly well even in exposed country up to altitudes of 400 m or more. The eighteenth-century landowners were very conscious of ‘picturesque’ landscape, not only in laying out their own estates, but in planting clumps of trees at focal points in the wider landscape – usually beech in chalk country, and pine in heathland (Chobham Clump near Woking was a much-loved landmark on the Surrey skyline in my childhood).

INDICATORS OF ANCIENT WOODLAND AND ECOLOGICAL CONTINUITY

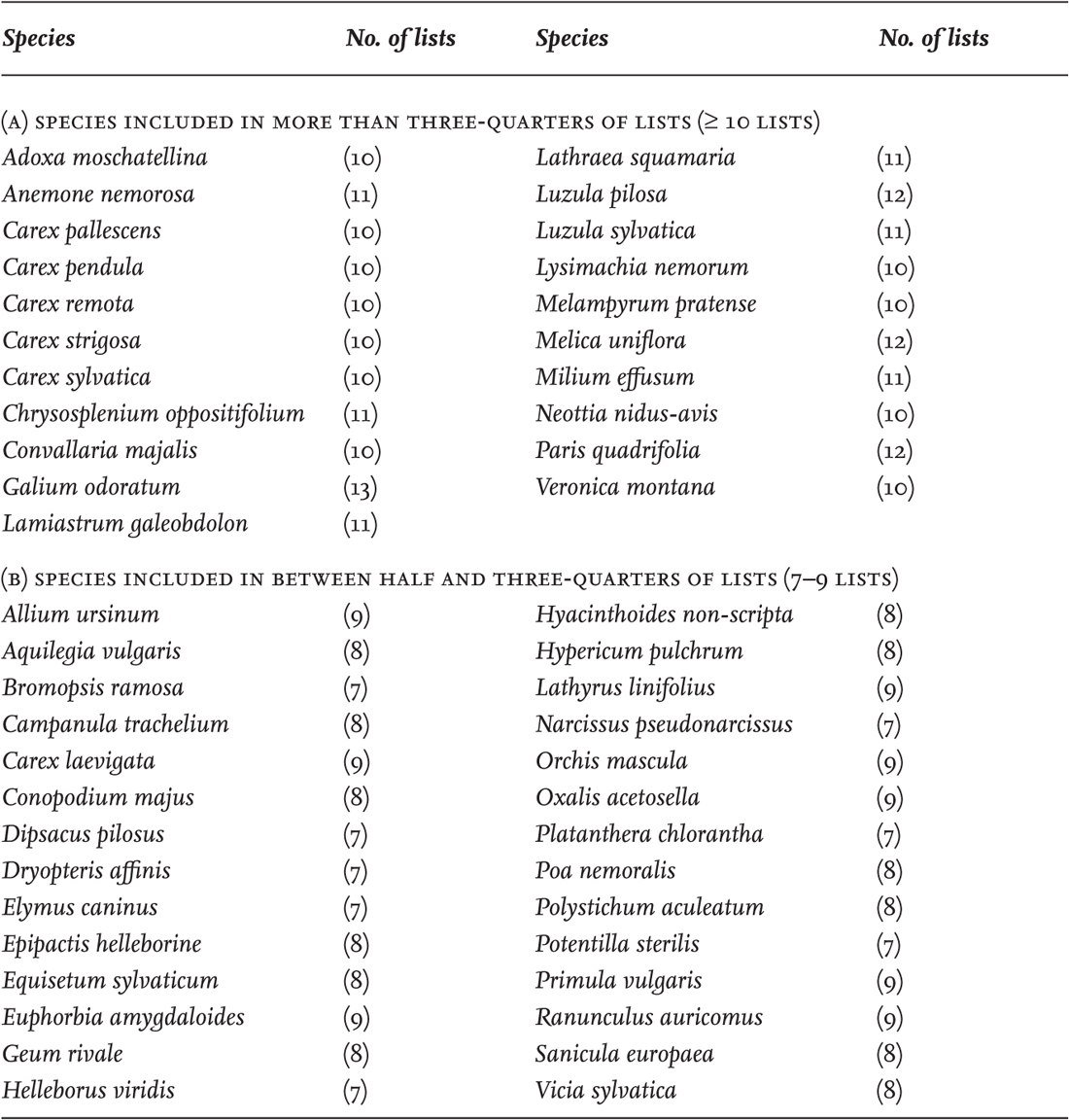

Growing understanding of medieval woodland management, and awareness of the biodiversity of old woodland, has led to an interest in indicator species of ‘ancient woodland’. It became apparent that a great many of our familiar woodland plants have been remarkably slow to colonise any woods planted since 1600. That year is taken as a defining date for ancient woodland, because tree-planting was not yet fashionable and any wood existing at the close of the sixteenth century had almost certainly been woodland for many centuries already. Indicators of ancient woodland vary somewhat from one part of England to another, but Table 4 gives the species regarded as ancient-woodland indicators in more than half of 13 lists collated by Keith Kirby in 2005. Most of these are quite common woodland plants. What is important about the list is that no one species, or no select group of species, is especially diagnostic. It cannot be said that if a particular rare species occurs, that wood is ancient!

TABLE 4. Species listed as indicators of ancient (pre-1600) woodland, in at least half (> 7) of 13 lists from different parts of England, collated by K. J. Kirby. Figures in parentheses give the number of lists in which the species is cited.

Lichenologists realised that certain uncommon lichen species are restricted to big old trees, such as grow in old parkland or wood-pastures. This led the late Dr Francis Rose to devise ‘indices of ecological continuity’, based on select lists of lichens. He envisaged his ‘revised index of ecological continuity’ as a tool for screening ancient parkland and wood-pastures, which could be widely used, and his ‘new index of ecological continuity’ as providing a finer-scale grading of sites, but placing greater demands on the identification skills of the observer (Rose 1976, 1992).

Indicator species of ‘ancient woodland’ or of ‘ecological continuity’ inevitably suffer from the limitation that they are only applicable in a particular area. Indicators of ancient woodland in the west of Britain and Ireland would be very different from lists appropriate to East Anglia or southeast England, and would have to include a high proportion of bryophytes and lichens.

WOODLAND TREES OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND

The oaks (Quercus spp.)

The two native oaks are the commonest dominant trees of established woodland in Britain, and on acid rocks in Ireland. They cast a moderately deep shade, but are somewhat more light-demanding than beech. The pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) is the dominant tree on the deeper and better brown-earth soils on clays and clay-loams with soil pH from around neutral to mildly acid. It can tolerate some degree of waterlogging, but is at its best on moist but well-drained lowland soils. Sessile oak (Quercus petraea) tends to grow on poorer, more sharply drained and more acid soils, but while this generalisation usually holds true in southeast England, it is fraught with qualifications and exceptions elsewhere. While the oakwoods on the valley sides around Dartmoor (on acid Carboniferous shales and grits) are of sessile oak, with pedunculate oak on the wetter valley floor, woods on steep valley sides on the granite, as well as the three small oakwoods high on the moor, are of pedunculate oak. Oakwoods on hard limestones are commonly of sessile oak, so there are more subtle soil factors than pH differentiating the two species. Both flower at about the time the leaves expand and are wind-pollinated. The crop of acorns is variable from year to year, especially at higher altitudes. The acorns germinate where they fall. Some are collected by jays, which often drop them, so oak seedlings can be found quite far from woods. The normal life span of the oaks (corresponding to our ‘threescore years and ten’) is probably about 300–400 years, but this figure may be even more variable than the human life span. Most of the other dominant trees of European broad-leaved forests probably attain similar ages.

Ash (Fraxinus excelsior)

This is the commonest dominant of chalk and limestone woodland, and probably the commonest woodland dominant in Ireland. It is a quick-growing, light-demanding tree, which casts a relatively light shade. It is notably late to come into leaf in spring, and the dark masses of wind-pollinated flowers appear at about the time the leaf-buds burst, ripening in late summer to bunches of wind-dispersed ‘ash keys’. Ash is a very effective pioneer, and its seedlings can be almost as much nuisance in the garden as those of sycamore, but it is palatable to livestock so needs a degree of respite from grazing to get established. Perhaps surprisingly for a tree that is so often associated with dry chalk and limestone, ash is tolerant of moist soils and is a common ingredient of fen woods. Unless coppiced, it is a rather short-lived tree, rarely lasting more than two centuries.

Wych elm (Ulmus glabra)

This is our native elm, and the only one that is a true woodland tree. It is a bigger tree than ash, and casts a deeper shade. It mainly occurs on base-rich soils, and is often common in woods on limestone, but never more than very locally dominant. It flowers in late winter on the bare twigs, producing the bunches of discoid winged seeds (‘samaras’) in summer. It is eaten avidly by livestock.

Beech (Fagus sylvatica)

Beech is a widespread forest dominant in central Europe, but was a late Post-glacial arrival in Britain, where its natural range is limited to an area from southeast England and the Chilterns to the limestone valleys of southeast Wales. It is widely tolerant of our climate outside those limits, in plantings and beech hedges high on Exmoor and Dartmoor (where it self-sows freely), and north to Aberdeenshire and throughout Ireland. It casts the deepest shade, and is the most shade-tolerant of our common forest trees, and is an uncompromising dominant on soils ranging from the rendzinas of the beech ‘hangers’ on the chalk to the acid brown earths and podzols of the plateau of the Chilterns and the heathlands of the New Forest. Like oak, it flowers as the leaves expand in spring, and the triangular beech nuts are shed in autumn and germinate readily where they drop.

Hornbeam (Carpinus betulus)

Hornbeam was another late arrival in Britain. It is widespread on the Continent, where it is rather southern and does not reach the Atlantic coast, and is a tree of rather base-rich woods, avoiding the most acid soils. As a native with us, it is confined to the southeast, with its headquarters from Kent and East Sussex to Hertfordshire and Essex. Here it grows on somewhat moist silty sands and sandy clays, usually in company with oak, and is nearly always coppiced (Fig. 57). Hornbeam roadside hedges were part of my Middlesex childhood. It belongs to the same family as birch, but the winged fruits are very different. It is often planted, mostly for garden hedging, because it stands clipping well.

FIG 57. Hornbeam coppice, Hog Wood, near Ifold, West Sussex, April 1985.

The limes (Tilia spp.)

The lime we are most used to seeing is the hybrid, Tilia × europaea, which is widely planted in parks and as a roadside tree. We also have both parent species as native woodland trees. Small-leaved lime (T. cordata) is a stately tall tree and was probably a major constituent of the wildwood over much of lowland England. It survives as a (usually) minor ingredient of ancient woodland in localities widely scattered over its former area, sometimes as a canopy tree, but more often as coppice. Unlike most of our other dominant trees, it bears its semi-erect clusters of flowers in summer, and is pollinated by both insects and wind. Large-leaved lime (T. platyphyllos) is much more local, usually in rocky woodland on limestone, as in the Derbyshire dales and the Wye valley; on the chalk it forms a sparse fringe at the base of the escarpment woods of the western South Downs (Abraham & Rose 2000). Apart from its larger leaves, it is easily recognised by its pendulous flower-clusters and fruits. Both limes are long-lived trees (old coppice stools can live for many centuries), and both are palatable to livestock. Small-leaved lime is limited northwards by its need for high-enough summer temperature to ripen viable seed (Pigott & Huntley 1981). In recent summers it has produced abundant seed (and seedlings) in northwest England.

The tree birches (Betula spp.)

The birches are elegant fast-growing but relatively short-lived trees; a birch a century old is a veteran. They are light-demanding trees, and cast only a light shade. Both our species produce their catkins in spring at about the time the leaves first expand, and are wind-pollinated. The ripe female catkins break up to release the tiny winged seeds, which are spread far and wide by wind, making the birches rapid and efficient colonisers. Our two species are closely related, but the silver birch (B. pendula) favours better drained and more base-rich soils, so it is the predominant species on dry heathland, and on chalk and limestone. Downy birch (B. pubescens) favours damper and more acid soils, so it is the species usually encountered in the damp oceanic west, or on acid peat. In upland areas of Scotland it is represented by ssp. tortuosa, which occurs too in Norway, northern Sweden and Iceland.

Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris)

This is one of the world’s most widely distributed trees, extending from Scotland to Siberia and from Lapland to the mountains of the Mediterranean. With us, Scots pine is now native only in the Scottish Highlands, but early in the Post-glacial it was ubiquitous in Britain and Ireland, and it seems to have hung on locally almost into historical times in some areas of dry limestone (such as the Burren) or heath. On the Continent it is a tree of poor soils and exposed places. In Scotland its headquarters is in the eastern Highlands, especially Deeside and Speyside, where, with its windborne seeds, it vigorously colonises heather moorland unless prevented by burning or heavy grazing. Scots pine has been exploited for timber for centuries in the areas that now have the greatest concentration of pine forest. Pine is widely scattered elsewhere in the Highlands, but seldom in large stands (Chapter 7).

Hazel (Corylus avellana)

We do not usually regard hazel as a ‘tree’ because we most often see it as an understorey shrub, often coppiced. Our species, left to itself, forms a large shrub or untidy small tree up to 5 or 6 m (or more) tall. It is one of our most widely distributed woody plants. It forms a regular part of the understorey of most of our woods, and extends far outside the confines of woods to dominate large areas of scrub (woods in all but name) in coastal districts of western Ireland and western Scotland – as also in western Norway. Hazel was immensely abundant in the pollen rain in the Boreal period some 9000 years ago. Hazel coppices well, perhaps a legacy of an evolutionary history of recovery from browsing. The yellow ‘lamb’s tail’ male catkins are a familiar sight in late winter. The heavy hazel nut is the seed of a plant attuned to the stability of established woodland or scrub (by comparison with light airborne seeds of the pioneer birches and ash), but observation of colonisation of limestone pavement suggests they serve hazel well enough (Chapter 6), no doubt with some help from small mammals.

Alder (Alnus glutinosa)

Alder dominated the pollen record in Britain and Ireland following the ‘Boreal–Atlantic transition’ about 8000 years ago. That was a time when the North Sea basin was filling, and the climate switched from rather continental to much more oceanic, and the indications are that the forests became much wetter. Alder must have dominated large tracts of country around the lakes and bogs whose deposits were sampled by the twentieth-century pollen-analysts. Alder is generally associated with moving water, either where water is upwelling or draining laterally through the soil; a widespread and important habitat is flushes or seepages in woods mainly of other trees (Fig. 86), or on the banks of rivers or streams (Fig. 58b), where it is commonly cut back at intervals to keep the banks clear for fishing and prevent excessive shading. Alders have root-nodules with symbiotic microorganisms that fix atmospheric nitrogen, so they are important in building up the nutrient capital of the wet woods in which they grow. Alder produces its catkins very early in spring, and is wind-pollinated. The ripe female catkins do not disintegrate like those of birch, but their scales gape apart to release the seeds and persist as centimetre-long black ‘cones’ all the following winter.

The sallows and willows (Salix spp.)

The genus Salix includes numerous species, and must be the most diverse in stature in our flora, ranging from tall riverside trees to the tiny arctic-alpine dwarf willow (S. herbacea), hardly a centimetre high. All are woody, and have simple leaves and catkins (male and female on separate plants). The species that concern us here are trees and shrubs of wet places. Colloquially, we generally distinguish ‘willows’, tall mostly riverside trees, with long leaves and catkins, from ‘sallows’ (‘sallies’), large spreading shrubs with ovate leaves and short ‘pussy willow’ catkins, which form patches of scrub on wet ground anywhere. The flowers of willows produce nectar, and the female catkins are pollinated by insects, and by wind. The two common riverside willows, white willow (S. alba, Fig. 58a), with its grey-green foliage and ‘church-tower’ outline contrasting with the deeper-green and more spreading crown of crack-willow (S. fragilis), were probably both introduced in prehistoric times, as was osier (S. viminalis) and almond willow (S. triandra), smaller trees of river- and stream-sides and osier beds – ‘sally gardens’ in Ireland. All four (and many hybrids) were used for basketry, and often coppiced or pollarded to produce a supply of pliable young shoots. There are three common sallows that are natives of long standing. Grey sallow (Salix cinerea) is an exceedingly common shrub of damp or wet soils ranging from calcareous fens to acid peaty gleys. It is more tolerant than alder of stagnant conditions, and its profuse fluffy wind-borne seeds make it a ready pioneer. In some places it covers many hectares of country (as in parts of Cornwall); in others it grows as patches or more isolated groups or individuals where it has happened to find a congenial moist-enough spot. Goat willow (Salix caprea) is less gregarious, and favours better-drained and more calcareous soils. It is a rather regular minor ingredient of woodland on chalk or limestone. In the north of England and Scotland, several other ‘sallows’ occur. Bay willow (S. pentandra) comes farthest south of these; tea-leaved willow (S. phylicifolia) and dark-leaved willow (S. myrsinifolia) are more northern. Finally, a very common and often only waist-high shrub of damp heath and moorland is eared sallow (S. aurita), with roundish grey-green wrinkled leaves and large stipules.

FIG 58. Riverside trees. (a) White willow, Hinton St Mary, Dorset, August 1972. (b) Alders beside the River Otter, Otterton, Devon, March 2011. This early spring photograph shows the characteristic straight main trunk reaching high into the crown

Minor woodland trees

Field maple (Acer campestre) is a defining small tree of lowland calcareous woodland in Britain, almost always present, but never even approaching dominance; it does not reach Ireland as a native tree. Its small lobed leaves colour an attractive yellow in autumn. Wild cherry (Prunus avium) is thinly scattered through lowland oak, ash and beech woods. It is unnoticeable except when it is in flower before the oak canopy is expanded, but the bark with its horizontally elongated lenticels is distinctive. Bird cherry (Prunus padus) with its racemes of white flowers is more confined to base-rich soils and is generally more upland and northern, but it occurs in fen carr in East Anglia. Aspen (Populus tremula) grows in woodland on a wide variety of soils, and up to high altitudes, but it is capricious in its occurrence. The catkins are borne before the leaves expand in spring; pollination is by wind. It readily suckers, so forming patches, and readily colonises bare ground by wind-borne seed. Holly (Ilex aquifolium) is very widespread as a minor shrub-layer component in all kinds of woodland, perhaps most characteristically in beechwoods on acid soils, where holly is often conspicuous in the shrub-layer and may form a subsidiary tree-layer under the beech canopy. It is often prominent in western oakwoods, as it famously is at Killarney, Co. Kerry. It is one of the few species that will grow amongst rhododendron. Holly occasionally forms small ‘woods’ on its own, as in various places in the New Forest. Perhaps surprisingly, young growth of holly is very susceptible to grazing. Strawberry-tree (Arbutus unedo) shares the evergreen habit of holly, but its undoubtedly native occurrence in moist rocky woodland around the lakes at Killarney (with an outlier in Co. Sligo) is far distant from its mainly west-Mediterranean distribution, so it is a rare but special tree with us. Yew (Taxus baccata) is widely but thinly distributed in lowland oak and oak–ash–field-maple woodland, and in beechwoods on acid soils. It is more constant in escarpment beechwoods, where it locally forms an almost continuous shrub-layer beneath the beech. Very locally it dominates woods on its own, notably on the chalk in southeast England, but also on Carboniferous limestone in the Wye valley, at the head of Morecambe Bay and near Killarney (Chapter 6). Rowan (Sorbus aucuparia) is very widely distributed as a minor ingredient in a variety of woods, particularly on acid soils, and in the uplands. It is often associated with sessile oak and downy birch. Well-grown rowans can be found on mountain ledges far outside woods. Its white insect-pollinated flowers appear in early summer and are followed by the bird-dispersed orange-red berries. Whitebeam (S. aria) is confined in Britain to an area from Kent to Dorset, the Wye Valley, the Cotswolds and the Chilterns, and nearly confined to calcareous soils. Like rowan (but unlike the apomictic Sorbus species considered in Chapter 8), it is a sexually reproducing tree, with white insect-pollinated flowers and red berries in late summer. It is occasional in oak–ash–field-maple woodland and beech and yew woodland on chalk and limestone, but probably only where it has been able to colonise open chalk and limestone grassland, or gaps in the wood. Many apparently suitable woods are without it. Wild service-tree (S. torminalis) is our third sexually reproducing member of the genus. It is an inconspicuous tree with brown fruits, probably most noticeable when the leaves fall in autumn, and their orange-yellow colour and characteristic shape stand out against the subdued brown of the oak leaves. It is widely but rather patchily distributed in woods on both calcareous and mildly acid soils.

SOME OTHER TREES IMPORTANT IN THE LANDSCAPE

Elms (Ulmus spp.)

The native wych elm is not our most familiar elm. That distinction must go to the hedgerow elms of the traditional farming landscape. Anyone whose memory extends back to the 1970s will remember the English elms (Ulmus procera) that were so much a feature of the lowland English landscape. The English elm is a magnificent tree, reaching 40 m high with a trunk 2 m in diameter (Fig. 59). It had many virtues as a hedgerow tree, giving shade, shelter, and foliage palatable to stock. Its timber is resistant to rotting when wet, and to crushing, which led to its use for water pipes, pier and wharf timbers, and lock gates. It was too liable to warp and shrink for much use in building. The English elm is female-sterile, but it is easy to propagate from suckers. Genetic analysis (Gil et al. 2004) has shown that probably all ‘English elms’ are part of a single clone, and genetically identical with trees in Spain and Italy, and with the Atinian elm used (pollarded) by the Romans to train vines. The Roman writer Columella records its introduction to Spain. There is no record of its introduction to England, but it is likely that it came with the Romans. When the fields were hedged after the Enclosures in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, English elm was widely planted as the preferred hedgerow tree. In East Anglia, Kent, the east Midlands and in the southwest forms of the small-leaved elm (U. minor) were predominant. All of these trees can propagate by suckering, which is useful for making hedges, and renders them virtually indestructible, and all were probably early introductions.

The elm disease caused by the fungus Ophiostoma ulmi and spread by the elm-bark beetle Scolytus scolytus (Figs 60, 61) has been around for a long time. There were outbreaks at intervals from the early nineteenth century, and there is no reason to suppose they were the first. The causal pathogenic fungus was first isolated in the Netherlands in 1921, hence the name ‘Dutch elm disease’. About the mid 1960s a new virulent form of the disease appeared in both Europe and North America, and it has devastated elms in both areas. The first outbreak in England was at Tewkesbury, Gloucestershire, and by the mid 1980s most of lowland England was affected. English elm proved very susceptible to the disease, and almost 100% of mature trees succumbed. However, the disease did not kill the roots, which continued to send up suckers. After 20 years’ growth the trunks had become large enough to suit the beetles, and the trees were reinfected. Other elms were not as susceptible. The various clones of small-leaved elm (Ulmus minor) showed varying degrees of resistance. The distinctively conical ‘Cornish elm’ (Ulmus minor ssp. angustifolia) proved susceptible when in the minority in English elm country, but largely escaped in Cornwall, where it is still a common feature of the hedgerows. Wych elms, perhaps because of their relative isolation, though susceptible, were only locally infected (Peterken & Mountford 1998).

FIG 59. English elm, showing symptoms of Dutch elm disease, Fiddleford, Dorset, August 1975.

FIG 60. Elm-bark beetle (Scolytus scolytus), Exeter, December 1975. Greatly enlarged; the beetle is about 5 mm long.

FIG 61. Elm-bark beetle. (a) Larval galleries under the bark. The primary burrow made by the beetle in which the eggs are laid is at the top right; the burrows of the individual larvae radiate from it. (b) The fully fed larvae are c. 5 mm long.

Sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus)

Sycamore was introduced into Britain in the sixteenth century. It was first recorded from the wild in 1632, and it was widely planted from the eighteenth century onwards. It is a native of continental Europe, where it occurs almost throughout Germany and is common in limestone woods in the hilly south of the country. It grows well throughout Britain and Ireland, and regenerates from seed (Fig. 62). It is anathema to many conservationists, but it seems to me that it is not as black as it is painted, and it actually does little harm. If it was bent on reducing our islands to a coast-to-coast monoculture of sycamore it would have done so long before now! It finds its optimum with us in base-rich woodland in the hilly west, a distribution recalling the ‘borderland woods’ of Peterken (2008), and much the same niche as in its native home. As an opportunist and coloniser it has a lot in common with ash, but it casts (and will withstand) deeper shade. In general it does not take over established woodland, and it remains surprisingly uncommon in our lowland woods. A lot of conservation effort is wasted on trying to eliminate sycamore, which could be devoted to worthier causes, with more prospect of success.

FIG 62. Sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus) by Great Close Scar, Malham, Yorks., at nearly 400 m altitude. This species is widely planted in the uplands for shade and shelter – here with a ring of dry-stone walling to protect the recently planted tree from grazing sheep.

WOODS AS HABITATS

Woods are sheltered, shady and cool in summer, and even after leaf-fall in autumn the leafless trees do something to temper the winter storms. Woods, in short, have a microclimate that is different from treeless places, and that microclimate varies round the seasons.

The microclimate of woods

Something has already been said about climate and microclimate in Chapter 1. Woods are complicated microclimatically because they are structurally complex, and the crowns of the trees are high above the ground. Microclimate is determined first by radiative exchanges of energy with the wider environment – radiation from the sun and sky during the day, radiation to the sky and other surroundings during the night – and second by convective exchanges of matter and energy with the air. Wind, blowing over vegetation, will probably be cooling it on a sunny day, and warming it on a cold clear night. At the same time it will be removing water vapour from the surface (so speeding evaporation when conditions are suitable) and imposing drag on the stems and leaves as it passes.

In summer the biggest energy exchanges, and most evaporation and drag, take place in the upper layers of the tree canopy. The drag of the tree crowns slows the wind. The leafy canopy absorbs most of the incident radiation; the light intensity reaching the ground may be only 1% of that above the canopy in a shady wood or forest. In a multi-layered wood each successive layer influences the climate of the layer(s) below, so it follows that the ground vegetation experiences a wholly different climate from the canopy, and the shrub-layer experiences a different climate from either. A plant on the ground in a dense wood is deeply shaded, windspeed is very low, therefore humidity is high – and evaporation is low because of the combined effect of high humidity, low windspeed and low net radiation income. Obviously some woods are more shady and sheltered than others.

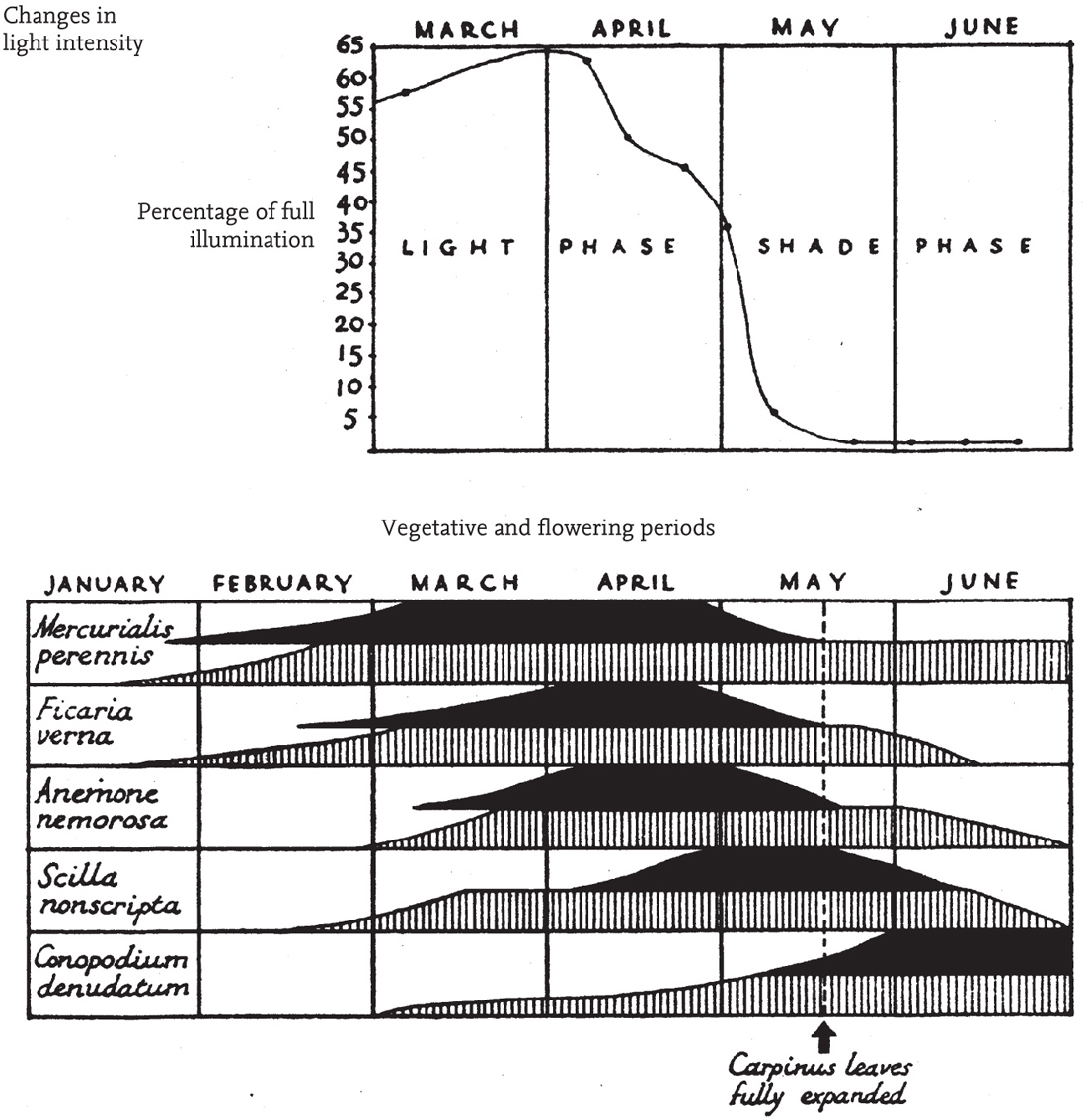

In winter there is no leafy canopy and energy exchanges take place on the branches and trunks of the trees, and on the ground. There will still be a gradient of windspeed from the uppermost twigs to the ground but it will be much less steep. Radiative heat exchange will still be concentrated to some extent in the dense twiggery of the canopy, but it will be much more diffuse, and much more tempered by convective heat exchange with the air than in summer (or in a grassland). Consequently, the twigs will track air temperature closely, and will not face the hazard of frequent ground frosts on clear nights, or benefit from the warming effect of the early spring sunshine. Except when the trunks are wet with rain, evaporation will be largely from the soil and plants on the floor of the wood. Through the depths of winter the radiation income is low even above the canopy. As radiation increases in spring, air temperature begins to rise, and daytime ground temperatures rise faster than the temperature of the air and of the buds of the trees. Radiation income in April matches that in August, but the air is still generally cool. Conditions on the woodland floor are congenial for growth and flowering of the woodland plants. For most of them this is the peak flowering season, for instance of lesser celandine (Ranunculus ficaria), wood anemone (Anemone nemorosa) and bluebell (Hyacinthoides non-scripta, Fig. 63). For many, the vegetative season lasts only a few weeks longer, and the leaves have died down by the end of June. By late April or early May, air temperature is at last high enough for the buds of the trees to burst and the woodland canopy to expand (Fig. 64). In July the wood takes on an entirely different aspect. Foliage of dog’s mercury (Mercurialis perennis) carpets the woodland floor throughout the summer, with ferns, shade-tolerant herbs such as pignut (Conopodium majus), and tall woodland grasses such as hairy brome (Bromopsis ramosa), giant fescue (Festuca gigantea) and wood millet (Milium effusum).

FIG 63. Vegetative and flowering periods of woodland herbs in relation to light under the tree canopy in oak–hornbeam woods in Hertfordshire. From Tansley (1939), based on Salisbury (1916). The leaves of lesser celandine, wood anemone and bluebell die by the end of June, but dog’s mercury and pignut remain green all summer.

FIG 64. Hemispherical (‘fish-eye’) photographs of the canopy of the sessile-oak coppice shown in Fig. 54: (a) early in April, and (b) some weeks later with the leaves expanded. The edge of the picture is the horizon, the middle is directly overhead. The two concentric circles mark 30° and 60° above the horizon. The curved lines from east to west are the tracks of the sun across the sky on the 22nd of each month, and the lines crossing them are the hours of the day from solar noon, when the sun is due south. At the equinoxes in March and September the sun rises due east at 0600 h and sets due west at 1800 h solar time. As in a star map, with north at the top east is on the left. The wood slopes at roughly 20° to the north-northwest, and receives no direct sun from early November to the end of January.

ECOLOGICAL FACTORS IN THE DISTRIBUTION OF WOODLAND

Woods vary from place to place with climate and soil. We might ask two rather different but related questions. Suppose that man had not come on the scene, what would the wildwood cover of our islands look like now? In other words, what is the potential natural vegetation? Or we can look at our present-day woods, and ask how their composition and distribution relate to climate, topography and soil – regardless of the fact that most our woods are far from being ‘natural’.

Potential natural vegetation

We can look for evidence of the potential natural vegetation of Britain and Ireland in the pollen record and the record of plant macrofossils preserved in peat or lake deposits, or we can extrapolate from the distribution and behaviour of individual species and their interactions and the composition of plant communities at the present day. That the uncertainties of inference are substantial goes without saying!

Regional differences in the character of the forest cover over Britain and Ireland can be mapped from the evidence of pollen analysis. This shows that the pre-clearance wildwood can be divided into five broad regions. In most of northern Scotland beyond the Great Glen the pollen indicates dominant birch (with some pine locally), and perhaps an open unwooded fringe in the extreme north and west. The Highlands east of the Great Glen were a region of dominant pine, and there was a long-persistent outlier of pine in the west of Ireland. The Highlands south of Rannoch Moor, the Isle of Mull, and the Scottish lowlands were predominantly oak–hazel territory, as were the Southern Uplands, the Lake District, the Pennines, most of Wales and Devon. In Ireland two blocks of country on acid rocks are similarly oak–hazel country, the mountains of Galway, Mayo and northern Ireland, and the granite, Ordovician and Old Red Sandstone mountains from Wicklow to Cork and Kerry. Over much of Ireland (predominantly on limestone or calcareous boulder-clay) the pollen shows elm and hazel as major trees in the forest, and the same is true of southwest Wales and Cornwall. In England, the Midlands and the south and east form a coherent region dominated by mixed oak forest in which small-leaved lime was abundant and locally dominant. However, we must remember that this was the climatic optimum of the Post-glacial, when temperatures were several degrees warmer than now. Oak, elm, lime and ash grew abundantly together in the mixed oak forest that then covered much of central Europe, but several key trees in that assemblage, including small-leaved lime, have retreated southwards and become more local as the climate has cooled

But, as ever, ‘the devil is in the detail’, and these five broad regions conceal a great deal of local variation in detail with topography and soil. John Cross (2006) has published a detailed potential natural vegetation map for Ireland. It agrees broadly with the pre-clearance regions defined by pollen analysis, but takes account of the (at least largely natural) expansion of ombrogenous bogs since that time, and envisages more oak–hazel forest on acid rocks in both the north and the south of Ireland. All such maps invite questions (which is what they should do!). Was there indeed a zone of birch forest on the higher parts of the Wicklow Mountains and McGillycuddy’s Reeks? As far as I know, no-one has so far attempted a similar exercise for the whole of Britain. It would be interesting to do so, but not an enterprise to be undertaken lightly. And should naturalised introductions like sycamore, rhododendron and (in Ireland) beech be included in our assessment of ‘potential natural vegetation’?

The distribution of woodland types at the present day

We are on much surer ground here, but immediately come up against the problem that, although the extremes may be very different, they intergrade, and it is extraordinarily difficult to draw clear boundaries between woodland ‘types’. Our woods form a continuum (like colour), but as with colour, we need to define some reference points if we are to talk intelligibly about them. Continental ecologists have the same difficulty in drawing clear boundaries (Wilmanns 1978).

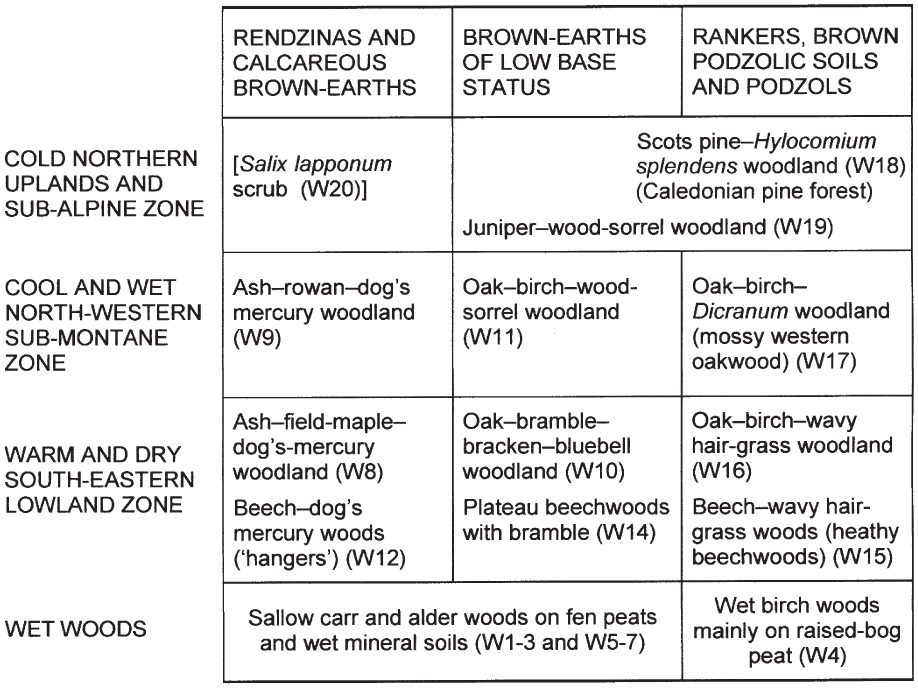

Woods vary with soil type, and there is also climatic variation with altitude and latitude and with degree of oceanicity or continentality, and there are distinctive woods on permanently wet soils. The next two chapters broadly follow the scheme adopted by John Rodwell (1991a) in British Plant Communities (Fig. 65). Soils fall into three major categories. The leached, acid soils (podzols and rankers) developed over old hard rocks or decalcified sands and gravels, are poor in nutrients and have a low pH (usually < 4.5), and a layer of acid humus accumulates on the surface. Brown-earth soils vary from mildly acid to around neutral (pH 4.5–6.5), organic matter is broken down at the surface and the humus incorporated into the soil by earthworms, and essential plant nutrients are usually in adequate supply; these are optimal soils for tree growth. The more calcareous brown earths intergrade with the rendzina soils over chalk and limestone, which vary from around neutral to weakly alkaline (pH often 6.5–7.5); calcium is abundant and the soils are usually reasonably nutrient-rich, but calcifuge species experience phosphate and trace-element deficiencies on these soils. The altitudinal-geographical divisions of the first column of Figure 65 are not hard-and-fast; they have very fuzzy boundaries. Thus woods of quite upland nature can occur at relatively low altitudes in southern England on poor acid soils, and favourable sites in the north and west can feel surprisingly southern in character. Juniper–wood-sorrel scrub grows at a wide range of altitudes from the Burren and the Dales of the north of England to the treeline in the Cairngorms. Some woodland types are in effect defined by the native range of individual tree species, Scots pine and beech are obvious examples. Field maple is a defining species of lowland ashwood in England and Wales, but hardly reaches Scotland and is absent from Ireland.

FIG 65. Habitat relationships of the major types of British woodlands, based on Rodwell (1991a), with the NVC code-numbers used there. The Irish ash–hazel limestone woodland (Corylo-Fraxinetum) shares some of the character of the British northern and southern ash woods (W8 and W9) and the Irish mossy oakwoods (Blechno-Quercetum) are equivalent to the western oak–birch woods in Britain (W17). Equivalent wet woods probably occur in both islands, but need further study.