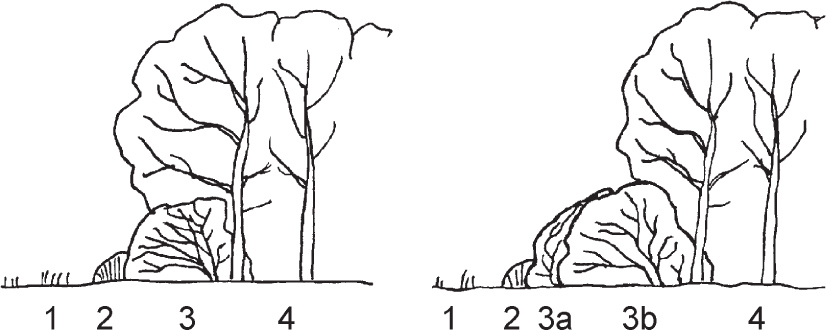

FIG 98. ‘Forest-border ecotone. 1. Open area (fields, pastures, heathland, etc.). 2. Saum of perennial herbs. 3. Shrub Mantel, (a) Vormantel, (b) Hauptmantel. 4. Forest.’ From Wilmanns & Brun-Hool (1982).

WOODS HAVE EDGES, glades and rides, and gaps left by windthrow or the death of old trees, and these places often have distinctive floras. Cultivated fields that are abandoned or grassland that ceases to be grazed is colonised by hawthorn, gorse or other shrubs, and ‘tumbles down to woodland’ within a few decades. Traditionally we divide fields or mark boundaries with hedges, and these again often have rich and varied floras, with much in common with wood margins. Many species (and vegetation types) are characteristic of these edge (or temporary) situations, and rarely or never occur in the extensive plant communities with a degree of permanence – of which you can sample a ‘uniform stand’ with a quadrat and hence are beloved of traditional plant ecologists!

Once you are fairly into them, woods are rather uniform places. The neighbouring patch is similarly shady to the one you are standing in, and it doesn’t much matter whether the leaf-fall, or nutrients leached from the canopy, or the seed rain, comes from this patch or the next. The birds and insects will be almost entirely woodland species, born and bred in the wood. The same, mutatis mutandis, is true of a grassland or heath. None of these things are true at the edge of the wood.

German plant ecologists have two useful concepts for wood margins, a zone of distinctive woody vegetation, which they call the Mantel (jacket, overcoat), and outside that a zone of herbaceous vegetation, the Saum (hem) (Fig. 98). The dominant trees within the wood are mostly pollinated by wind, and generally their seeds do not rely primarily on animals for dispersal – though oak, beech and hazel undoubtedly benefit from the activities of seed hoarders like squirrels and dormice, and yew has bird-dispersed fruits. The trees and shrubs of the Mantel are generally insect-pollinated, and they often produce fruits that are eaten and the seeds dispersed by birds such as thrushes that range widely over the landscape. Typical Mantel shrubs are hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna), blackthorn (Prunus spinosa), dogwood (Cornus sanguinea), wayfaring-tree (Viburnum lantana), buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) and brambles (Rubus fruticosus agg.); many of them are thorny or spiny. The Mantel is most prominent at the edge of woods dominated by light-demanding trees, such as oak or ash. The most shade-tolerant trees (and in general those that cast the deepest shade), like beech or yew, tend to form a Mantel from their own lower branches.

FIG 98. ‘Forest-border ecotone. 1. Open area (fields, pastures, heathland, etc.). 2. Saum of perennial herbs. 3. Shrub Mantel, (a) Vormantel, (b) Hauptmantel. 4. Forest.’ From Wilmanns & Brun-Hool (1982).

The Saum, of herbaceous species, is distinct from both the Mantel and the neighbouring vegetation, which may be farmland, grassland or heath. It benefits from the shelter and influx of nutrient from leaf-fall of the woody vegetation on the one side, and light, pollinators and possibilities of dispersal on the other, and often shows ‘ruderal’ tendencies (Chapter 10). Common ‘wood-margin’ species include red campion (Silene dioica), greater stitchwort (Stellaria holostea), garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata), ground-ivy (Glechoma hederacea), tufted vetch (Vicia cracca), rough chervil (Chaerophyllum temulum), nipplewort (Lapsana communis), germander speedwell (Veronica chamaedrys), agrimony (Agrimonia eupatoria) and many others (Fig. 99). These herbaceous wood-margin and hedgerow communities are placed in the order Glechometalia by phytosociologists on the Continent. In warm dry situations, particularly on chalk and limestone, a different range of species occurs, including some favourite aromatic herbs. Wild marjoram (Origanum vulgare), wild basil (Clinopodium vulgare) and common calamint (Clinopodium ascendens) grow in vegetation of this kind fringing scrub and woodland, and on hedgebanks (order Origanetalia). Wood sage (Teucrium scorodonia) has a rather similar range of habitats, but extends farther north and onto more acid soils.

These two zones may be narrow or broad, compressed within a metre or less, or expanded to many times that.

FIG 99. Typical species of woodland fringes and hedgerows: (a) garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata), also known as jack-by-the-hedge; (b) rough chervil (Chaerophyllum temulum); (c) ground-ivy (Glechoma hederacea); (d) sweet violet (Viola odorata); (e) nipplewort (Lapsana communis); (f) germander speedwell (Veronica chamaedrys).

Gaps in woods come in different sizes and forms. Where a tree has died standing, the crown will probably have thinned gradually, allowing suppressed saplings or seedlings on the floor of the wood to fill the gap almost imperceptibly. If one or a group of trees is windthrown it will almost invariably create a sudden gap, letting light in to the floor of the wood over a significant area. What happens then will depend very much on the trees and other species in the neighbourhood of the gap. Over the first year or two the most immediate change will be increased vigour of the ground vegetation, and several species are often conspicuous in the early stages of colonisation of gaps, however caused. One of these, particularly in woods on acid soils, is foxglove (Digitalis purpurea). Foxglove is biennial, forming a large non-flowering leaf rosette in the first year and producing its spectacular spike of bumblebee-pollinated flowers in the second year. It sets a profusion of tiny seeds. In the lowlands, and on any but the poorest soils, by the second year brambles will be noticeable, and (unless there is significant grazing by deer or other animals) within five years the whole of the floor of the gap will probably be a tangle of their prickly arching stems.

What about the trees in regeneration gaps? This depends very much on the available seed parents. If there are already tree seedlings or saplings on the floor of the wood, light will stimulate them into rapid growth. Otherwise ash, with its wind-dispersed ‘keys’, is quick to colonise any patch of open ground. Ten years or so after a gap becomes vacant it is common to see it occupied by a dense growth of ash saplings, tallest in the middle of the gap where there is most light. As the ash trees grow, the weaker saplings are suppressed, and the group opens up into a patch of ashwood in which, in due course, more shade-tolerant trees such as oak or beech can become established. On acid soils, the first to colonise the gap will probably be birch or sallow, both with wind-borne seeds, and both relatively light-demanding. Shrubs such as hawthorn are seldom important in the closure of small gaps.

We have already considered the special case where routine cutting of coppice is followed by spectacular displays of the spring woodland flowers – but the coppice-stools are poised to grow up quickly and re-establish woodland conditions. Large gaps left by windthrow or felling of the dominant canopy trees have more opportunity to develop distinctive communities and to show clearly the stages in succession back to closed woodland. Wild strawberries (Fragaria vesca – immensely better flavoured than cultivated varieties!) often become abundant in the early years of a gap opening and, especially if there has been some burning, rosebay willowherb (Chamerion angustifolium) can lay on a display of pink rivalling foxgloveOV27. Deadly nightshade (Atropa belladonna) occupies a similar ecological niche in gaps in beechwoods on the Continent, but it is rarer and more capricious with us.

The word itself is abrupt and abrasive, and the picture it calls up is hardly more inviting. Yet scrub – shrub-dominated vegetation – is varied, dynamic and, taken as a whole, far from dull. Probably the commonest kind of scrub is that which appears in fields or grassland that are no longer grazed or mown, but the nature of the scrub that develops depends on the soil and situation.

Hawthorn and brambles are by far the commonest woody plants invading neglected farmland, and remain virtually constant throughout the development of scrub. Blackthorn and dog-roses (Rosa canina agg.) are also typical early colonists, and where the soil has been disturbed or enriched elder may gain a foothold. In the early stages of succession the bushes form a patchwork with the grassland, but as the leafy canopies of the dominant bushes meet, the grassland species are mostly shaded out. The scrub at this stage can be pretty forbidding. The hawthorn and its spiny and prickly associates form a near-impenetrable thicket. In summer little light penetrates to the largely bare ground. The only other plants that are anything like constantly present are ivy, which, being evergreen, can take advantage of the winter season to maintain at least a thin (and sometimes total) cover over the ground, and a scatter of stinging nettles and cleavers (Galium aparine). Apart from that, and occasional ash and sycamore saplings, this hawthorn–ivy scrubW21 is generally species-poor. There is a long list of grassland, woodland-fringe (Saum) and woodland species that can occur, but seldom in any quantity or with any constancy. There are two exceptions to this generalisation, both on calcareous soils, and probably both related to the proximity of seed parents. Quite often, the species list recalls a sparse skeletal version of the ground flora of a chalk or limestone wood, with patches of dog’s mercury. In freely drained sites where the scrub has colonised open ground on chalk or limestone dog’s mercury and most other woodland species are missing, but false brome (Brachypodium sylvaticum) can be prominent.

As the scrub ages and the canopy of the hawthorn rises and thins, more woodland species can establish, and the scrub becomes in effect a hawthorn wood. But, by this time, some of the ash and sycamore saplings will have grown into substantial trees. From this stage it is only a matter of time (perhaps half a century) before the site becomes a mature ashwood, maybe with an admixture of sycamore, and (if a jay has dropped a few acorns) maybe a young oak or two, but with a field-layer largely derived from woodland-fringe species. In the 1960s, when I first knew Hooken Cliff (Fig. 100) at Branscombe in East Devon there was a patchwork of hawthorn scrub and grassland. My two boys enjoyed the dense scrub, which had small boy-sized tunnels underneath that you could explore, coming up in unexpected places. The patches of grassland have long since gone, and much of the former ‘impenetrable’ scrub has opened up ready to be colonised by seed from the ash trees, which must have established decades before I knew the site. All stages of succession from hawthorn scrub to ashwood can be seen at the Axmouth–Lyme Regis Undercliffs NNR, a few kilometres east along the coast (Fig. 101).

FIG 100. Hooken Cliff, Branscombe, Devon, May 1970. Chalk grassland in foreground, a patchwork of grassland, hawthorn scrub and ash trees in the middle distance.

FIG 101. Old hawthorn–ivy scrub, Axmouth–Lyme Regis Undercliffs NNR, May 1973. This scrub is around 6 m high, and must be many decades old. It contains some well-grown ash trees; the field-layer is principally ivy, but stinking iris (Iris foetidissima) and hart’s-tongue fern (Phyllitis scolopendrium) are also conspicuous.

My generation of Cambridge botany students was taught ‘the five calcicolous shrubs’ by the late Mr Humphrey Gilbert-Carter: dogwood (Cornus sanguinea), wayfaring-tree (Viburnum lantana), wild privet (Ligustrum vulgare), spindle (Euonymus europaeus) and buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica – he would never have allowed us to use English names!). The first three of these (Fig. 102) characterise a distinctive variant of hawthorn–ivy scrub on chalk and limestone in the south and east of England (Fig. 103). Traveller’s-joy or ‘old man’s beard’ (Clematis vitalba, one of our few woody climbers) is often conspicuous scrambling over chalk scrub (Fig. 102d); another common scrambler is black bryony (Tamus communis), particularly noticeable in autumn from its glossy vivid orange-red berries. Brambles and wild roses are prominent in chalk scrub (sweet-briar, Rosa rubiginosa, is often common), and ivy is still dominant in the field-layer. False brome, wild marjoram and wood sage (Teucrium scorodonia) are frequent around the fringes of the scrub.

FIG 102. Calcicolous scrub species: (a) dogwood (Cornus sanguinea); (b) wild privet (Ligustrum vulgare); (c) wayfaring-tree (Viburnum lantana); (d) traveller’s-joy (Clematis vitalba).

Sixty years ago it would have been impossible to write about chalk scrub without mentioning rabbits. Rabbit warrens were common on the downs. Disturbance and enrichment of the soil round the warrens provided niches for elder bushes to colonise and, once fairly established, their corky bark made them relatively immune to rabbit attack. Juniper (Juniperus communis) is still quite widespread on the chalk of southern England, but it was formerly much commoner than it is now, probably largely because it needs very short turf or open ground for the seedlings to establish, and young plants are vulnerable to heavy grazing. Sheep and rabbits will eat it, but it is low on their list of preferences. When rabbits were abundant, juniper served as a nurse species for yew and other woodland trees, which were able to establish shielded by its relative unpalatability. Much of the yew wood in Juniper Bottom near Box Hill in Surrey grew up in this way; the dead and dry juniper bushes beneath the yews long kept their characteristic ‘cedar-pencil’ smell. Establishment of hawthorn and the other chalk shrubs required some relaxation of rabbit grazing, but most of them (except juniper) can sow themselves into even quite rank grassland.

FIG 103. Hawthorn colonising chalk grassland, Malacombe Bottom, near Tollard Royal, Dorset, May 1970. Hawthorn just past flowering, whitebeam showing the silvery grey undersides of the newly expanded leaves, ash leaves not yet fully expanded. The ridges in the foreground are terracettes, formed on the slopes by the trampling of grazing livestock.

All habitual makers of sloe gin will surely have their favourite patch of blackthorn scrub! It is not easy to pinpoint habitat differences between scrub dominated by hawthorn and by blackthorn. Hawthorn usually occupies well-drained sites on a wide range of soils from mildly acid to highly calcareous. Blackthorn favours soils that are at least reasonably base-rich and generally rather moist, and it withstands wind-exposure better than hawthorn. Hawthorn (and chalk) scrub is commonly seral – on its way from colonising grassland (or whatever) to becoming woodland. Blackthorn scrub often gives the impression of greater permanence, along wood margins, or on windswept sea-cliffs. Relative stability of habitat may be a factor in the wide distribution of that rather secretive and sedentary butterfly the brown hairstreak, whose larvae feed on blackthorn. Brambles, roses and ivy are less ubiquitous in blackthorn than in hawthorn scrub, but the field-layer frequently includes bracken, red campion, common dog-violet (Viola riviniana), germander speedwell, cleavers and scattered grasses, and sometimes a thin scatter of woodland species such as dog’s mercury, wood-sorrel, herb-robert (Geranium robertianum) and primrose.

Blackthorn scrub on sea-cliffs (Chapter 20) often has a seasoning of species from the neighbouring maritime grasslands, particularly grasses such as cock’s-foot (Dactylis glomerata), red fescue (Festuca rubra) and Yorkshire-fog (Holcus lanatus). On exposed coasts, blackthorn, ivy and bracken can interact in bizarre ways. On Alderney I have seen low blackthorn overtopped by bracken growing up through it to unfurl a leafy canopy tens of centimetres above the branches and leaves of the scrub. On the south coast of Guernsey, the erect flowering phase of ivy can form a significant fraction of the canopy of the wind-pruned blackthorn scrub on the cliffs.

Sir J. E. Smith (1759–1828), founder of the Linnean Society, wrote in Rees’s New Cyclopaedia that ‘Linnaeus was so enchanted with the gorse in full flower on Putney Heath that he flung himself on his knees before it.’ The story may be apocryphal, but I have experienced almost equally emotional reactions from Continental visitors at the mass of golden-yellow on the roadsides between Exeter and the Lizard when gorse is at its peak (Fig. 104). Common gorse has a different ecological niche from our other two species, which are plants of heathlands on poor, acid podzolic soils, and have a shorter flowering season in late summer (Chapter 16); if common gorse occurs on these heaths it is generally a sign of disturbance or local enrichment of the soil. It is a plant of moderately acid brown-earth soils, occasional in acid oakwoods, but probably essentially a wood-margin species.

FIG 104. Common gorse (Ulex europaeus) scrub in full flower in early May, East Budleigh Common, Devon. The lower-growing western gorse (U. gallii), abundant in the rest of the heath, will flower later in the summer.

Common gorse is frequently the dominant of patches of scrub in suitable country, generally in company with a low cover of brambles, with various acid-grassland species, including common bent (Agrostis capillaris), Yorkshire-fog, sweet vernal-grass (Anthoxanthum odoratum), heath bedstraw (Galium saxatile), tormentil (Potentilla erecta), cat’s-ear (Hypochaeris radicata), common dog-violet and sheep’s sorrel (Rumex acetosella); bracken is often present, but seldom dense or particularly well grownW23. Roads or tracks across heaths, or through acid woodland, are often lined with gorse scrub, and the cuttings of new trunk roads in southwest England have provided wide stretches of suitable habitat for it. Gorse scrub is widespread on exposed sea-cliffs, where it is probably a permanent element of the vegetation pattern determined by interaction of topography and wind (Chapter 20).

Brambles often grow as a fringe covering the base of a hedge – a Vormantel in terms of Wilmanns & Brun-Hool’s diagram in Figure 98. The bramble–Yorkshire-fog (Rubus fruticosus–Holcus lanatus) underscrubW24 described in Rodwell (1991a) is in effect a bramble Vormantel plus a Saum typical of a contact with false oat-grass (Arrhenatherum) grasslandW24b and some other communitiesW24a. Obviously, the details of such transitions will vary with what is on either side; this community provides a couple of fairly typical examples from among many possibilities.

Wilmanns & Brun-Hool (1982) described two Vormantel communities from Ireland, a field rose (Rosa arvensis) community in Co. Offaly (which is also in central Europe, and must surely occur elsewhere in Ireland and in Britain), and a wild madder (Rubia peregrina) community from Killarney. Wild madder has its main distribution in the Mediterranean, but its northern limit follows the winter isotherms up the Atlantic coast to Ireland and southwest Britain (Fig. 6), where it is common in calcareous districts scrambling through scrub and hedges.

Bracken finds its optimum with us on well-drained acid soils, and is often a troublesome invader of bent–fescue pastures in the hillsU20. It also dominant on some rather better soils in the lowlands. Here, in a ‘bracken–bramble underscrub’ it is usually accompanied by a thin understorey of brambleW25. On deeper and moister soils it is usually accompanied by bluebells with, for example, creeping soft-grass (Holcus mollis), cock’s-foot, ground-ivy, herb-robert, male-fern (Dryopteris filix-mas), pignut (Conopodium majus), common dog-violet, red campion and occasional patches of stinging nettles and cleavers. This variant sometimes occurs inland, usually in association with woodland, or maybe marking sites of former woodland or wood-pasture, but is common on the sea-cliff-slopes of southwest England and Wales (Fig. 105), and no doubt of Ireland too. It is very striking in spring when the bluebells are in flower but the bracken is not yet unfurled. It has probably become more widespread on the coast of southwest England in the last half-century, with the decline of grazing on coastal cliff-slopes. On drier, thinner and more acid soils the community usually lacks bluebell and many of its accompanying herbs, bramble is often more prominent, wood sage (Teucrium scorodonia) is common, and Yorkshire-fog and foxglove are frequent (Fig. 106).

FIG 105. Bracken–bramble underscrub, bluebell sub-communityW25a. North side of Start Point, Devon, May 1992: bracken just unfurling, bluebells in full flower colouring the whole of the north side of the headland a misty blue.

FIG 106. Bracken–bramble underscrub: wood-sage sub-community, here with an abundance of foxgloves as the bracken is just unfurling. Later in the summer the cliffslopes bear a uniform green covering of bracken. Prawle Point, Devon, May 1992.

A ‘hedge’ means different things to different people, and in different contexts. Medieval farmers knew all about ‘dead hedges’, barriers of stakes interwoven with brushwood and thorns, but these were probably always temporary expedients to meet an immediate need, or while a live hedge grew up – dead hedges were prodigal of labour and materials, whereas live hedges were self-renewing. Hedges in Devon and Cornwall are commonly on banks, sometimes with a facing of stones on the sides, and a Cornish ‘hedge’ is the bank itself regardless of whether anything grows along the top. Much the same is true of many exposed western districts of Britain and Ireland, though the words used to describe it may differ. There are pine hedges on Breckland, and beech hedges on Exmoor. But we are concerned with ordinary live field and roadside hedges here. In the mid twentieth century it was estimated that there were some 750,000 km of hedges in Britain; the total for Ireland would have been perhaps a third of that. Square fields 4 ha in area imply 10 km of hedge per square kilometre. That may be not unrepresentative of traditional farming country (in some areas density is certainly greater), but of course over wide areas of Britain and Ireland hedges are (and have always been) few and far between.

Modern hedges are planted, but there are several other ways in which a hedge can originate. Hedges can be relics of former woodland, left defining the boundary between the cleared fields on either side. Hedges can arise by growth of self-sown tree and shrub seedlings along a fence-line or bank. Planted hedges may use whatever saplings are available locally (in which case they will probably be a mixture of species from the outset), or they may be planted with one or two species, usually in recent times nursery-grown.

Some hedges that we know to be ancient from documentary records are likely to be woodland relics, and so too are some other hedges, judging from the evidence of their constituent trees and other characteristics. Hedges that have arisen as ‘secondary woodland’ along some kind of linear feature (and may be comparably old) are probably the hardest to be certain about. By their nature, their origin is unlikely to have been recorded. The frequency and rapidity with which boundaries become colonised by woody plants in the modern landscape – the Fleam Dyke in Cambridgeshire following myxomatosis, abandoned railway lines, and wire or wooden fences – show that this sort of process could have operated in the past, and should not be discounted lightly. Many hedges were planted from medieval times onwards in districts where open fields never dominated the landscape, and the enclosure of open fields around villages began early.

All planted hedges are not the same. We have to consider the purposes for which the hedge was planted (which will influence the species chosen), and the source of material available for planting. Marking boundaries and providing a barrier against straying of livestock are the two most obvious, but in past centuries people expected much more from their hedges. Hedgerow trees were an important source of timber (a surveyor’s report on a seventeenth-century mid-Devon house I once lived in spoke of ‘hedgerow scantlings’ for many of the smaller timbers), and hazel, ash and elm in hedges were potential livestock feed. During the period of Parliamentary enclosure many kilometres of hedge were needed in a hurry, and hawthorn ‘quicks’ could be mass-produced from seed in nurseries, and could provide a stockproof barrier after a few years’ growth.

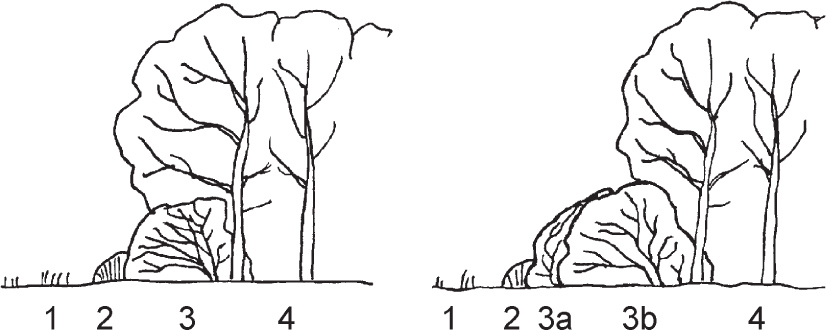

In the 1970s Max Hooper and his colleagues at Monk’s Wood Research Station, Ernest Pollard and Norman Moore, published a relationship between the number of trees and shrubs in a hedge and its age, which has caught popular imagination (Pollard et al. 1974). From a study of 227 hedges in Devon, Lincolnshire, Cambridgeshire, Huntingdonshire and Northamptonshire for which there was documentary evidence of planting date, they proposed the equation A = 110S + 30, where A is the age of the hedge in years, and S is the average number of woody species in a 30-yard (27.4 m) length of hedge (Fig. 107). Taken uncritically (which the original authors specifically warned against), this would mean that the number of woody species in the hedge is roughly equal to its age in centuries, but a glance at the graph shows how misleading this simple assumption can be!

FIG 107. ‘Hooper’s rule’. Number of woody species plotted against documented age for 227 hedges in the south and east of England (from Pollard et al. 1974).

There can be no doubt that ‘Hooper’s rule’ enshrines a real truth that, other things being equal, old hedges are richer in woody species than young hedges. Hooper and his colleagues envisaged two reasons why this should be. The oldest hedges might be relics of former woodland. Alternatively (or in addition) old hedges might be species-rich because they had had the most time for colonisation. This second suggestion obviously applies to all hedges, regardless of their origin. A third possibility has already been touched on: that hedges may have been planted with a desired mix of species, or that what was planted may have been dictated by the mix of saplings that were to hand, whereas enclosure hedges were usually single-species plantings of hawthorn.

The evidence for some hedges being woodland relics is persuasive. Abundance of trees normally confined to woodland, such as small-leaved lime or wild service-tree, is good evidence of a woodland origin. Hazel, dogwood, spindle and field maple are other indicators. Hedges with several of these trees and shrubs generally have a good number of the herbaceous plants regarded as indicators of ‘ancient woodland’, such as dog’s mercury, primrose, bluebell, wood anemone and yellow archangel (Table 4), but the distribution of some of these seems to have more to do with soil than with the age of the hedge. In the mild southwest a number of woodland species are common in open situations that they would not tolerate farther east. Herbaceous ‘indicators of ancient woodland’ should be used with even more caution than woody species as evidence of the age of hedges – particularly in richly wooded neighbourhoods.

Old hedges can show uncharacteristically low numbers of woody species for several reasons. One is competition, particularly in hedges dominated by suckering elms, which can exclude virtually all other woody plants. Another is that a number of woodland trees and shrubs tend to be gregarious, so that successive 30-yard lengths of hedge are dominated by one or two species, even though the hedge as a whole is quite diverse.

‘Hooper’s rule’ has its place as a useful rule of thumb, provided it is used critically. It will usually differentiate enclosure hedges (1750 onwards), with only one or two woody species, from those of earlier times, even though those oldest hedges amongst themselves often show almost no relation between the number of woody species and the date when they were first recorded.

A line of shrubs is not of itself a stockproof barrier, and hedges were traditionally ‘plashed’ or ‘laid’. In winter, after cutting back and removing dead stems and unwanted growth (and weeding out undesirable species), the main stems (pleachers) were cut roughly three-quarters through, and bent over to overlap their neighbours so that, when growth resumed in spring, they would form a continuous impenetrable wall of vegetation. There were many regional (and probably individual) styles of plashing or laying. In the classic Midlands style, vertical poles of ash or hazel (stabbers) were driven in at intervals of some 70 cm and the pleachers woven between them, and the hedge was finished at the top with a band of pliable hazel stakes woven in and out of the stabbers to keep these and the pleachers in place. In Wales and southwest England, some of the niceties of the Midland style were not observed and hedge-laying was aimed at producing a denser and often wider hedge. In a multi-species hedge there must be an element of catch-as-catch-can about laying hedges, and in a neglected hedge many of the woody stems will have grown too thick for laying. In Devon, it is common to see ash laid horizontally for several metres, often in both directions from the base, creating a living post-and-rail fence, and I have seen the same in Co. Sligo. It is also common to see gaps in hedges patched with whatever stop-gap came to hand, often sheep-netting, or an old bedstead. Hedge-laying championships give a very partial view of what happens in practice in real countryside! Traditional hedgerow management is labour-intensive, and most hedges, particularly along roadsides, are now cut with tractor-mounted flail cutters. The immediate results with a flail cutter are not pretty, but cutting this way is far better than no cutting at all.

Hedges are a maintenance liability, they take up a significant amount of land that could be growing crops, and small fields are awkward and time-wasting for large-scale farm machinery. For these reasons many hedges have been removed, especially from arable country in the south and east of England. Norman Moore and his colleagues (1967) compared sample areas in aerial photographs taken in 1946 and 1962–63, and found losses ranging from 0.12 km per square kilometre in Cornwall to 2.13 km per square kilometre in Huntingdonshire. They saw evidence of destruction of hedges in every one of 23 English counties, in 11 out of 12 Scottish counties and in all of the six Irish counties they passed through in the course of their journeys. The length of hedge on three manors in Huntingdonshire, covering 16 km2, reached a peak of about 122 km in 1850 following enclosure, and was only a little less in 1946. By 1965 it had fallen to 32 km, almost the same as in the early fourteenth century at the height of medieval open-field farming. The process has continued, but in most places the 1950s and 1960s probably saw the greatest losses.

Hedges are complex habitats and, potentially at least, correspondingly rich in species. The hedgerow trees represent a woodland core, most important in the older hedges of ‘ancient countryside’, but often lacking, especially in hedges planted in the last century or two. Typically, most of the woody species of the hedge are thorny shrubs or small trees, which might equally be found along the edge of a wood; these may be fringed by brambles and roses, and other scrambling plants. But a very large component of the hedge flora, including many of the species we think of as most characteristic of hedgerows, is made up of essentially woodland-margin plants – species of neither woodland nor grassland, but more or less tied to the linear habitat where the two meet. At its foot the hedge grades into Arrhenatherum grassland, meadow or pasture, or the ruderal vegetation of arable fields or roadside. The proportions of these components vary enormously from hedge to hedge; some hedges in a district can be very rich in species (especially in ‘ancient countryside’), whilst others are disappointingly poor. Hedges are a conservation resource we do not take seriously enough.

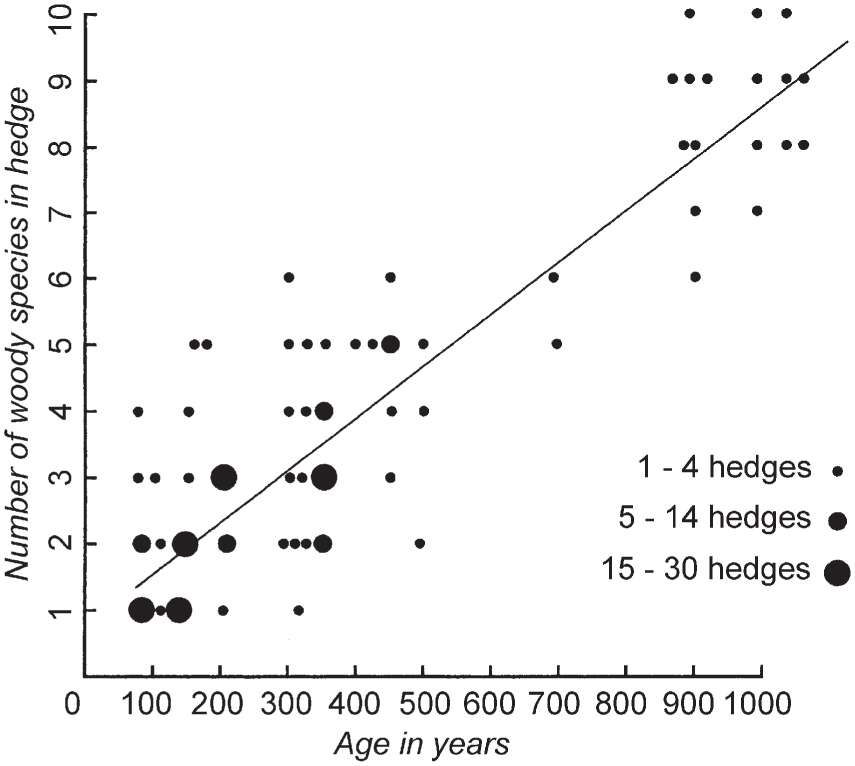

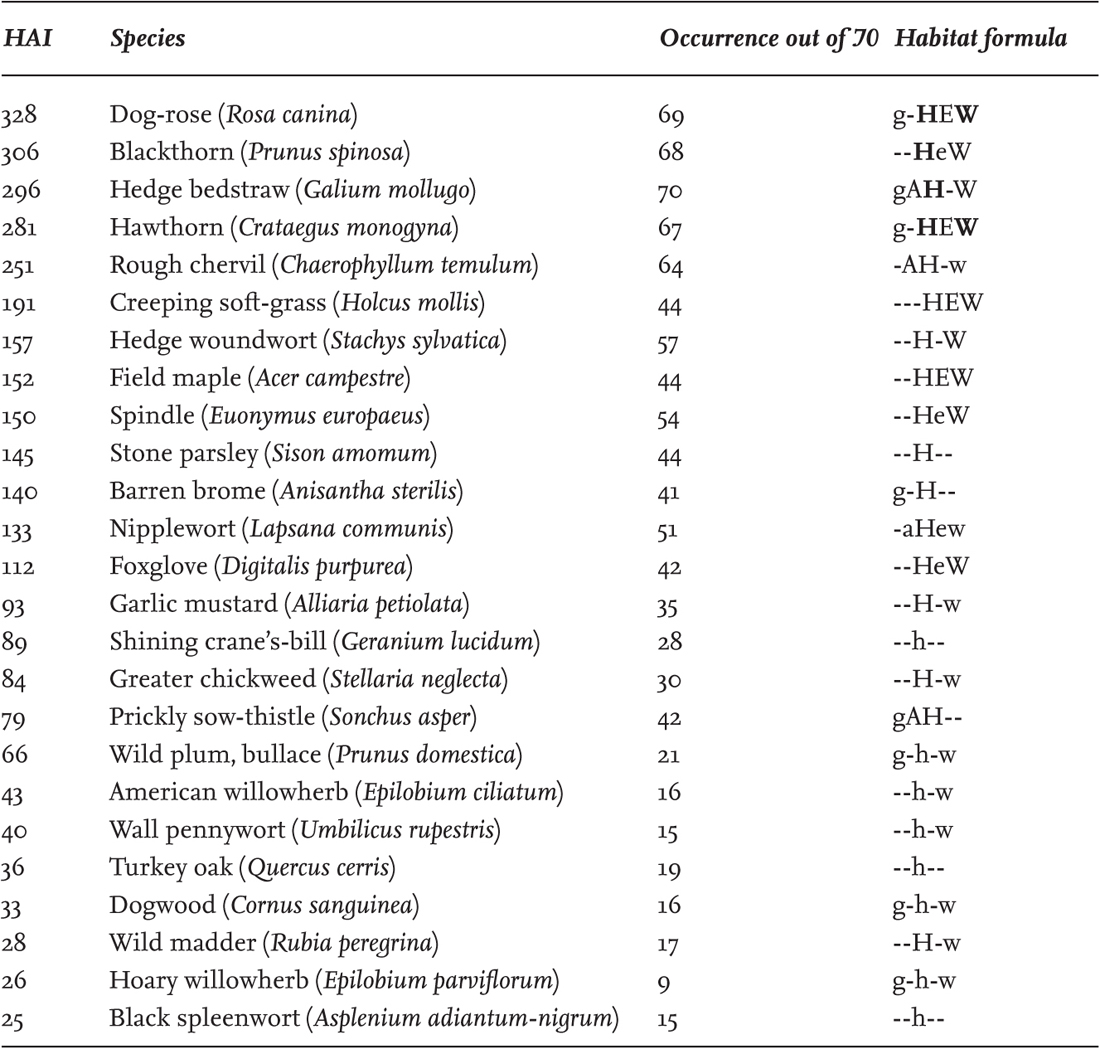

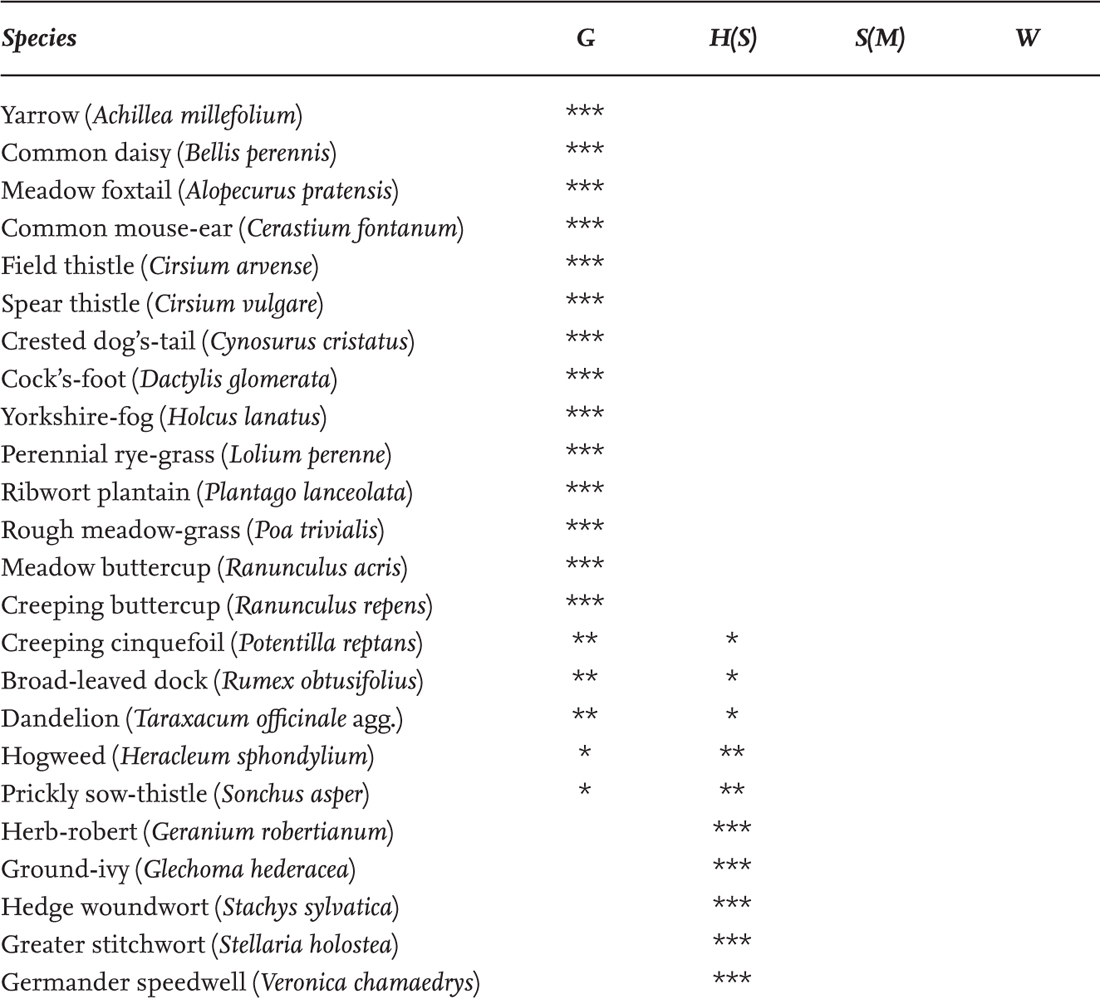

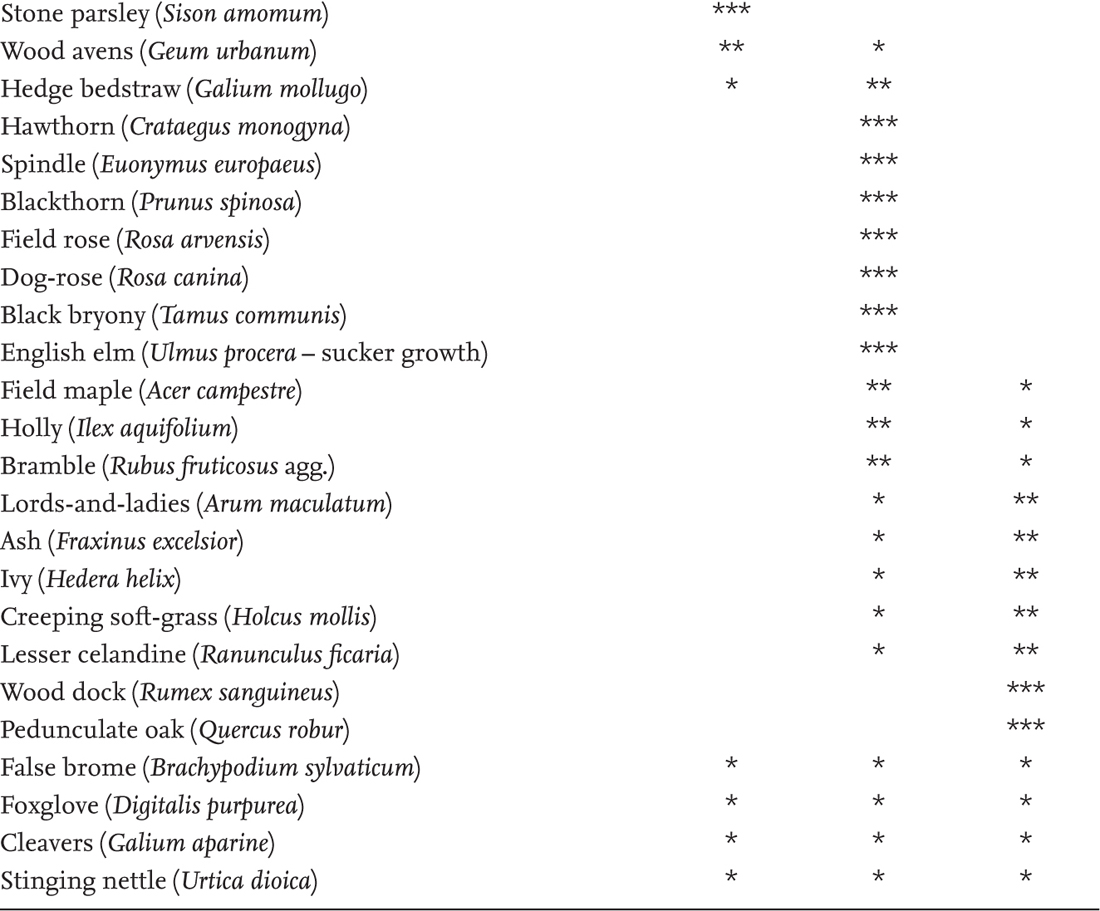

The hedges of Farley Farm near Chudleigh in South Devon may serve as an example (Michelmore & Proctor 1994). Farley is a small farm (28 ha), typical of the area, mostly on the south-facing slopes of a small coombe on Carboniferous shales, about 100 m above sea level. Counts of woody species in 30-yard samples of hedge yielded a mean of 5.9 species (s.d. 1.6) from 81 samples, so from Hooper’s rule the hedges are evidently old, with no significant variation from one part of the farm to another. Of Farley’s 12 fields, 10 were under grass and two were arable at the time the survey was made. For recording, the hedges were divided into segments by intersections and gates, and the two sides of the hedge were recorded separately. This gave 70 stretches of hedge, in which the species were recorded on a subjective scale from 1 (very rare) to 7 (dominant); the product of these two figures gave a ‘hedge abundance index’ (HAI) from 1 to 490 for each species. Table 5 lists the species with the top 25 HAI scores. The lists from the 70 hedge segments were also analysed statistically. They fell into eight main groups, three (A–C) representing the common dry hedgerow flora, including such species as shining crane’s-bill, garlic mustard, rough chervil and nipplewort. Group D was the largest, embracing the most ubiquitous species in all the hedges. The more abundant of these are listed in Table 6, and (tentatively) assigned to zones in the hedge. Group E are less widespread but are another central group, including such characteristic hedgerow plants as agrimony (Agrimonia eupatoria), meadow vetchling (Lathyrus pratensis), honeysuckle (Lonicera periclymenum), wild madder, wood sage and tufted vetch. Group F adds some species that avoid the driest sites, or favour some degree of shade, such as bugle (Ajuga reptans), hazel, bluebell, dog’s mercury, primrose and fleabane (Pulicaria dysenterica). Groups G and H are almost all species of moist or shady place, such as wild angelica (Angelica sylvestris), marsh thistle (Cirsium palustre), meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria), greater bird’s-foot trefoil (Lotus pedunculatus), hart’s-tongue fern (Phyllitis scolopendrium), red campion, lady-fern (Athyrium filix-femina) and opposite-leaved golden-saxifrage (Chrysosplenium oppositifolium), concentrated in the damp valley bottom.

TABLE 5. Farley Farm, Devon. The 25 most abundant ‘characteristic hedge species’, defined arbitrarily as ‘those whose total score in all other habitats was not more than double their score in hedges (HAI, see text), and whose hedge habitat score is not exceeded by that in any other single habitat’. This excludes brambles and some woodland plants (notably pedunculate oak). In the habitat-formula column, g = grassland, a = arable, h = hedge, e = edge (of woodland), w = woodland; ‘-’ indicates absence; lowercase, uppercase, and uppercase bold indicate minimal, minor and major presence respectively.

TABLE 6. A different view of the Farley hedges. The species with 50% or more of possible occurrences in the largest species-group (D) to emerge from a multivariate statistical analysis. This group embraces most of the ubiquitous hedgerow species. In this table they have been roughly divided between the main components of the hedgerow: grassland species G (including some ruderals), herbaceous woodland-fringe species H (Saum), woodland-edge shrubs and their associates S (Mantel), species of woodland W.

The main variation at Farley is between the hedges associated with well-drained arable fields up on the spurs, and those associated with permanent pasture in the moist valley. A subsidiary trend can be detected from a more ruderal to a more stable, late-successional flora, but there is clearly a great deal of chance (or unexplained) variation. The variation at Farley is paralleled elsewhere in Devon, and many mid-Devon lanes are lined by hedges dominated by blackthorn, hawthorn and hazel, and bright in spring with red campion, bluebells, greater stitchwort and germander speedwell (Fig. 108). Hedges on wetter and poorer soils often contain an abundance of sallow, rare at Farley. On the Devonian limestone around Torbay or on chalky soils in east Devon different species again are prominent – dog’s mercury, yellow archangel and ramsons (Allium ursinum) amongst others. And hedges in other parts of the country pose their own questions.

Declan Doogue and Daniel Kelly (2006) analysed the woody species in hedge samples widely spread over eastern Ireland (Table 7). They found a primary gradient from base-rich soils, supporting hedges rich in spindle, hazel, wild privet and guelder-rose, to acid soils, with rowan, gorse and downy birch. There was a clear secondary dry–wet gradient, with sycamore, wych elm, ash, elder and honeysuckle at the dry end, contrasting with alder, sallows, buckthorn and birch, which favoured wetter habitats. They found roadside hedges to be richer in woody species than hedges dividing fields (average 7.43 as against 6.47 species per 30 m sample); the difference is statistically significant, but not dramatic. The answer to the question posed in the authors’ title is clear: the assemblages of woody species in the hedges of eastern Ireland are mainly the products of environment – but with detectable historical influences.

TABLE 7. Eastern Irish hedges. Frequency of trees, shrubs and woody climbers in hedgerows across Leinster from 90 aggregate sites (10 pooled samples per 10 km grid square) and from 865 individual 30 m hedge samples. Species in less than 10% of the aggregate sites omitted. From Doogue & Kelly (2006).

FIG 108. (a) Roadside near Morchard Bishop, Devon, May 2000; hedge of hazel, oak, ash, blackthorn etc. (b) Detail of hedge bank; red campion, creeping buttercup, greater stitchwort and germander speedwell in flower.